This plan was developed for the City of Iqaluit by a consulting team led by George Harris, Senior Landscape Architect/ Partner, George Harris Collaborative Inc.

The team was guided by the City of Iqaluit Project Manager, Matthias Pizzera, Director of Recreation, with input from the City of Iqaluit Recreation Committee.

The Iqaluit Trails Master Plan is a comprehensive strategy designed to enhance the connectivity, cultural heritage, and well-being of the Iqalummiut community through the development of a diverse and sustainable multi-use trail network. The plan acknowledges the historical and cultural significance of trails in the Arctic, serving as essential pathways for survival, social interaction, and the transmission of traditional knowledge.

Iqaluit, a city with deep-rooted Inuit heritage, is marked by its unique geographical, political, and social context. The city's Arctic climate, natural beauty, and diverse population contribute to its distinct character. Trails play a crucial role in connecting people to each other, the land, and cultural traditions, promoting both physical and mental well-being.

The Trails Master Plan addresses several challenges faced by Iqaluit including harsh temperatures, wind corridors, limited formal trails, social isolation, and inadequate trail maintenance. The plan envisions Iqaluit as a city with an expansive and inclusive network of trails, serving as a primary community asset. It aims to revive cultural heritage, foster ecological stewardship, promote well-being, and establish a cohesive, accessible transportation network. Guiding principles include environmental stewardship, cultural heritage preservation, recreation promotion, and futureoriented planning.

The Trails Master Plan sets forth several key goals:

• Establish a community vision for the trail network

• Improve connectivity between amenities and neighborhoods

• Support Inuit recreational interests and cultural practices

• Enhance all-season trail use and active transportation

• Develop culturally inclusive wayfinding and amenities

• Foster intergenerational knowledge sharing and community involvement

The Trails Master Plan outlines strategies for implementing its vision and goals. It proposes collaboration between community members, private landowners, governmental organizations, and Indigenous associations. The plan aims to create a network of trails that accommodates various uses, preserves cultural heritage, and adapts to changing conditions.

The Iqaluit Trails Master Plan seeks to strengthen the social fabric, cultural ties, and overall wellbeing of the Iqalummiut community. By fostering a sense of connection to the land, promoting outdoor activities, and creating safe and inclusive pathways, the plan will contribute to the unique character and identity of Iqaluit for generations to come.

Iqaluit, a city with a thousand years of history, boasts a vibrant past and a distinctive cultural heritage. From the early days of Dorset and Thule Inuit cultures, people have traversed the Arctic region in pursuit of opportunities to establish connections and sustain their lives through close ties to the land. Today, over half of the city’s population is Inuit and the remaining population represents a diverse fusion of cultures and nationalities. Iqaluit blends aspects of Euro-Canadian urbanism with a strong commitment to living in harmony with the seasons, land and sea. Human connectivity remains

In the ever-changing seasons, the climate-adapted houses and businesses of Iqaluit bring colour, vitality, and artistic expression all year long. Iqalummiut stay connected to neighbours, friends, and family by traversing the city and the surrounding landscape by foot, car, boat, bicycle, skis, or dogsled. People cherish this community connection, and the Iqalummiut hold a deep desire to pass down knowledge to younger generations regarding the importance of sustaining their way of life through outdoor and traditional activities, such as hunting, harvesting, fishing, camping, boating, hiking, cycling, kayaking, skidooing, skiing, dog sledding and sliding. All of which underscore the importance of their close relationship with the land.

Rising temperatures and unpredictable weather patterns have introduced unprecedented challenges in venturing outdoors. Changes in ice conditions, precipitation, and drainage patterns have amplified the hazards associated with land and sea travel. As a result, accessing traditional knowledge and wisdom from elders has become considerably challenging, leading to a sense of disconnection and isolation from their community. Invaluable, traditional resources, untapped.

In 2023, the City of Iqaluit hired George Harris Collaborative, Inc. to develop a Trails Master Plan that supported the community’s current needs in providing a safe passage between neighbourhoods, parks, schools, commercial areas, and open spaces, as well as to the land.

• Low Temperatures and Wind Corridors minimize time spent outdoors, Reducing Human Interactions

• Limited Formal Trails

• Lack of Maintenance of Trails, Trailheads, and Spontaneous Camp Sites Leading to Deterioration of Tundra

• Declining Rates of Trail Use among Youth and Inuit Population

• Limited Outdoor Facilities

• Limited Inuit Cultural Programs and Activities

• Limited Access to Equipment and products related to recreation

• Insufficient Activities for Elders in Winter

• Social Isolation

• Canadians feel happier, healthier and more productive when they are connected to nature. As a result, there is a growing interest in activities that connect children and families to nature programs. Nature Conservancy of Canada reports 9 out of 10 Canadians want to improve their relationship with nature. Trail walking is the first step.

• Recognizing trails and multi-use paths as recreation facilities that need to be planned and maintained.

• Creating trail systems that can be used year round. By all ages and abilities.

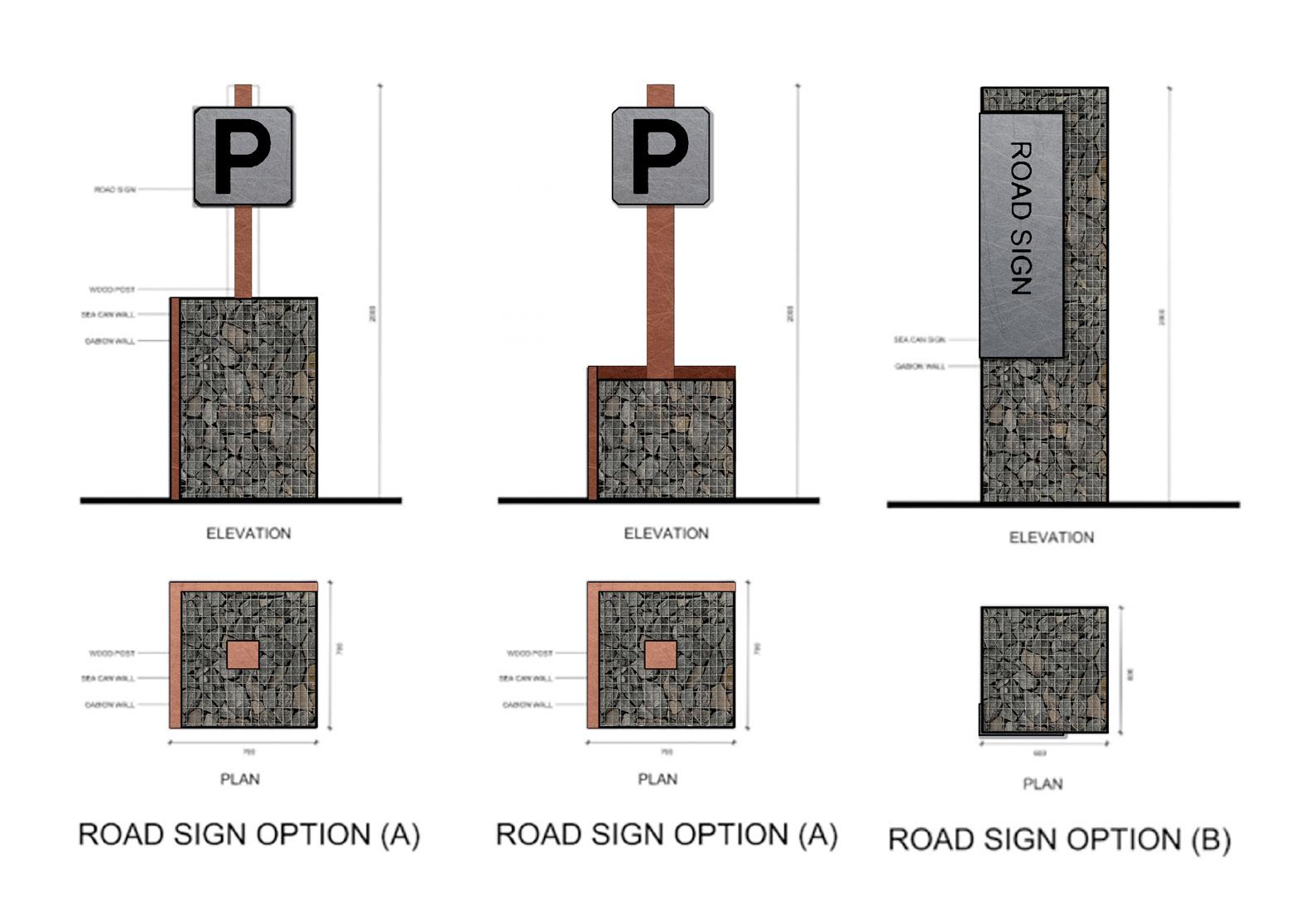

• Adding warming huts, sanitary facilities and signage/furniture to trail systems.

• Municipalities are designing spaces to be inclusive by incorporating mobile technologies, resting spaces, and child-friendly spaces.

Iqaluit is distinctive from a Canadian perspective, as half of the city’s population is Inuit. As an Artic community, Iqaluit is unique because so many of its residents come from other cultures and countries. The city’s unique character and identity are profoundly influenced by its geographical, political, and social context.

Iqaluit, found within the Canadian Shield, occupies a landscape of gently rolling hills, characterized by rocky formations and valleys covered in tundra vegetation. Positioned alongside the hills of Frobisher Bay, Iqaluit's geological composition mainly consists of igneous and metamorphic bedrock. The city is situated on Baffin Island in the Qikiqtaaluk region of Nunavut, encompassed by hills near the Sylvia Grinnell River, and offers a view across the bay towards the mountains of the Meta Incognita Peninsula.

The city experiences a typical Arctic climate, where people enjoy nearly 24 hours of sunshine in late June and early July, while the shortest days of December offer only four hours of daylight with the sun appearing low on the southern horizon. Iqalummiut participate in a variety of different activities in both summer and winter. During winter (approximately 9 months of the year), indoor facilities see the heaviest use. In warmer months, however, Iqalummiut prefer to stay outdoors and go out on the land or on the water for recreation.

Nunavut, meaning "our land" in Inuktut, encompasses a total of 26 communities within its territory. In the mid20th century, the Inuit community grew dissatisfied with the prevailing social issues, including alcoholism, substance abuse, unemployment, and crime, prevalent in their regions. Consequently, they exerted pressure on the federal and territorial government to grant them greater control over the administration and management of their own affairs. Throughout the 1980s, negotiations between the Inuit and Canada ensued, culminating in the Inuit voting in favour of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act in 1992. The Parliament of Canada voted in favour of the Agreement and enshrined it into law in 1993.

The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act led to the division of the Northwest Territories, with the lands to the west of the treeline remaining part of the Northwest Territories, while the lands to the east of the treeline became Nunavut. Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, is situated in the Qikiqtaaluk region, also known as the Baffin region.

The Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) serves as the Regional Inuit Association for the Qikiqtani Region of Nunavut, representing 51 percent of the Inuit population residing in Nunavut. Designated as an Inuit Organization under the Nunavut Agreement, QIA manages all Inuit-owned lands in the Baffin region.

QIA's establishment aims to safeguard, promote, and advance the rights and benefits of Qikiqtani Inuit. As a designated Inuit Organization under the Nunavut Agreement, QIA collaborates closely with partners such as Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and the Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada, as well as various levels of government, to advocate for Inuit within the Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit Homeland. There are 944 parcels of Inuit Owned Land, where the mineral rights are retained by the Crown. While 144 parcels of Inuit Owned Land possess surface and mineral rights, which covers approximately 38,000 square kilometers. Locating Trails on this land may be possible after negotiations with the QIA.

In the Arctic, the profound link between society and the natural environment, is unlike any other region in Canada. The Inuit people have not only survived but flourished in this demanding Arctic setting for thousands of years, owing to their exceptional ingenuity and environmentally mindful subsistence system rooted in their deep connection to the land. Within Iqaluit, the Inuit community constitutes 59% of the population and preserves elements of their traditional way of life, including the gathering of fish, wildlife, and berries, which hold significant importance in their daily routines. The remaining population, comprising individuals with diverse backgrounds such as Newfoundland, Francophone, Filipino, and South Asian heritages, takes pride in their cultural identities.

As the city of Iqaluit undergoes rapid growth in population and development, it faces the stark contrast between short, warm summers and long, cold winters. In this unique and challenging environment where social interaction is crucial for survival and urban structures are scarce in a growing city, trails play a vital role in connecting people to both social and natural infrastructures in the extreme Arctic climate. The Trails Master Plan presents a comprehensive strategy for establishing a community-wide network of trails that caters to mobility needs through sustainable design. It takes into account the specific challenges posed by the local geology, terrain, and climate to create trail and pathway infrastructure that meets the needs of the community, while safeguarding ecological resources.

Nunavut is home to numerous and vast trail systems. They are enjoyed by many, from newcomers looking to explore the beautiful Arctic landscape, to seasoned hunters and their families travelling who rely on the trails to get to and from the land. Many of the trails across Nunavut are of cultural significance, with some areas associated with legends that have been passed down through generations.

Trails have always played an important role in the lives of the Inuit, serving as an essential part of survival in the Arctic. Through careful observation of natural landmarks and formations in the land, Inuit were able to guide their way from one place to the next with ease. With years of consistent use, trails were formed, providing reliable routes to areas with fresh water, plentiful game, and other resources. Trails also served important social and cultural functions as they connected different communities and families which allowed for the flow and exchange of knowledge and resources.

Since Inuit were moved into permanent settlements trails have taken on a new significance, maintaining the vital connection between Inuit and the land. Inuit continue to maintain and protect trails, acknowledging their role in connecting past and present generations. and preserving traditional knowledge and practices. In hamlets and towns across Nunavut, trails continue to serve as links to areas of significance, as well as important points of connection between remote Nunavut communities, which are otherwise only accessible through air travel.

With communities in Nunavut changing due to growing populations and the effects of climate change, it is important to ensure that these vital connections to the land are preserved and adapted for future generations to enjoy.

Augatnaaq Eccles

The purpose of this project is to develop a collective vision for the City of Iqaluit and to present a Trails Master Plan that will enhance the connectivity between critical facilities, community destinations and residential neighbourhoods in Iqaluit. The plan will provide strategic recommendations related to the ongoing development of the communitywide trail network system.

Despite social and political changes, the Iqalummiut continue to cherish their deep-rooted connection to the Arctic environment, which surrounds them in its breathtaking beauty. Upholding and strengthening this bond with the land will play a vital role in safeguarding and enriching Iqaluit's distinct character.

The significance of trails to the community is acknowledged by the City of Iqaluit. As mentioned by the Sustainable Community Plan and Transportation Master Plan, the community is in critical need of active transportation facilities that provide safe passage for commuters and recreational users between neighbourhoods, parks, schools, commercial areas, and open spaces, as well as adjacent communities.

The adoption of the Trails Master Plan and the commitment to its implementation and refinement provides an opportunity to:

• Plan and build necessary trails from the ground up

• Enhance connectivity of the physical, political and social aspects of Iqualuit

• Beautification of community

• Promote tourism and civic pride

Iqaluit will have a comprehensive network of sustainable multi-use trails that will be valued as one of Iqaluit’s primary assets. This newly established network will serve to revive cultural heritage that has been eroded over time and address the increasing feelings of isolation and detachment from the land. Accessible local trails will connect the downtown area, neighbourhoods, recreational facilities, shops, waterfront, parks and open spaces, creating an inclusive and safe transportation network throughout the city. The breathtaking natural environment of Iqaluit's recreational trails will promote the well-being of the community and contribute to an exceptional quality of life. Trail development will be a collaborative process of partnerships and agreements between the community, private landowners, the Province, Qikiqtani Inuit Association and the City of Iqaluit.

I. Truth & Reconciliation: The awareness and need for integrating the work of truth, justice, and reconciliation into everyday lives is critical to developing a symbiotic relationship with our fellow Indigenous communities and our land. The Trails Master Plan recognizes the value in providing opportunities for Canadians to develop and grow from understanding diverse stories that exemplify the impacts of our colonial past.

II. Environmental Stewardship: We must look to ecological systems to provide guidance in maintaining and developing trail networks in the city. The Trails Master Plan will enhance the ecological value through sustainable trail planning and management, while minimizing the impact on Iqaluit’s ecosystem and advancing the city’s commitment to tackle climate change.

III. Cultural Heritage: The plan seeks to protect and celebrate the traditional practices and routes that have been passed down by elders, countering the sense of isolation and disconnection experienced by the community. Promoting the land as a cherished natural asset will enhance the city's bond with nature while also educating the public about Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, and cultural practices.

IV. Recreation Destination: As a recreation destination, trails are a vital component in engaging people with the unique natural landscape of the Arctic. Providing safe and inclusive access to key locations, such as Geraldine Lake, enables people to build connections, find inspiration and nurture communal life. In this newly integrated recreation destination, residents and tourists can all take part in the inclusive growth of Iqaluit.

V. Plan For the Future: The Trails Master Plan will identify the strengths, constraints, and opportunities for design improvements through innovative strategies in trail planning and management to ensure we meet the needs of the city of Iqaluit. The Master Plan must possess the ability to adapt to the evolving demands of the expanding local community as well as forthcoming generations.

• Establish a community vision for the Iqaluit Trails Master Plan that reflects the diverse Iqalummiut community

• Identify key issues and opportunities for the existing trail network

• Improve connectivity between neighbourhoods and community amenities

• Support the development of Inuit recreational interests, such as shifting seasonal activities and subsistence skills

• Support programming activities that develop Inuit traditions, such as land navigation, plant identification and wilderness survival

• Improve all-season use of trails

• Explore opportunities to increase active transportation

• Improve wayfinding and communications that are culturally inclusive

• Identify opportunities for nodes/amenities

• Mitigate impacts on environmentally sensitive areas

• Identify opportunities for new trail development and growth

• Formalize trail use regulations, trail type classifications, and designated uses

• Provide a trails cost matrix strategy

• Provide a long-term plan that creates opportunity for local community involvement in maintenance and expansion, especially youth

• Provide opportunities to share and experience traditional knowledge and activities

The Trails Master Plan was developed in the context of existing plans and policies. The following documents played a role in developing the content of the plan:

• Iqaluit Recreation Master Plan

• Iqaluit Sustainable Community Plan

• Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action

The Iqaluit Recreation Master Plan guides the city's Recreation Department for the next ten years. The plan reflects the unique challenges and opportunities presented by the Arctic environment, including its remote location, challenging climate, and diverse demographics. Grounded in a ‘Locals Know’ approach the plan addresses the needs of Iqalummiut, honouring the deep-rooted connection between the natural environment and the ability to participate in human recreation and culturally significant activities. In an environment where social connection is critical for survival and urban structures scarce, recreation facilities take on the role of social infrastructure, acting as not only physical but also spiritual places that serve purposes of healing, socialization, free play, and alleviating loneliness. The Trails Master Plan is a key piece in realizing these goals. A well-defined network of trails with options to accommodate different uses facilities not only physical accessibility but the transfer and sharing of knowledge as the community can more easily come together.

The Recreation Master Plan divides the recreation system into three primary recreation platforms: municipal, third-party, and spontaneous, encompassing not only indoor facilities but permanent and seasonal outdoor sites. In the summer these include kids biking trails, healing and contemplative places such as Apex Hills, and Socializing Viewpoints. In the winter, snowmobile trails, hiking and walking trails, sled dog trails, and XC trails. The plan emphasizes the importance of land-based activities that facilitate Inuit traditions and cultural exchange, shifting with the seasons.

The Recreation Master Plan prioritized community engagement as a strategy in identifying the diverse priorities of the community. There were many key findings speaking to the desire for further development of the trail system, including:

• The community aspires to participate in more outdoor activities including cross country skiing, hiking and kayaking

• Harvesting activities, such as hunting, fishing, and berry picking, are enjoyed for subsistence, spiritual, social and recreational purposes

• More conventional winter and summer activities enjoyed in the south, such as cross-country skiing, bouldering, and hiking, are being adapted to Arctic conditions and practiced by many Iqalummiut of all backgrounds.

• Elders identified winter conditions and transportation as barriers to recreation, and a desire for intergenerational activities.

The plan includes 5 key strategies that direct the City of Iqaluit to augment and adjust current programs and facilities towards opportunities that not only reflect Inuit cultural traditions and recreational activities, but also celebrate and incorporate the uniqueness of the Arctic landscape and the diversity of Iqalummiut. These strategies include: improved communication, identification of priority customers, delivery of programs collaboratively, delivery of facilities collaboratively, and re-organization of the business unit. Each key strategy is broken down into implementation steps with specific actions and prioritized on a timeline. The Facility Specification Tool can be used to assess the implementation of trails.

The Recreation Master Plan identifies determinants of success including:

• Social, Community, and Cultural determinants. Emphasizing facilities and programming that addresses diverse needs. Specific opportunities include: Developing programming around Inuit cultural activities, increasing open play and unstructured programming for all ages, use of Inuktitut.

• Physical, Spatial, and Contextual Determinants. Specific opportunities include: developing more outdoor facilities to support seasonal interests, identify and support established spontaneous activities by providing basic amenities such as benches, waste receptacles and signage at unorganized sites, create city-wide movement corridors, such as a pedestrian trail networks with supporting shelters (wind breakers, warming huts) to link facilities to all neighbourhoods, encouraging use of locally sourced materials

• Business, administrative, and organizational determinants. Specific opportunities include: developing a granting and rewards program to support volunteering, utilize local expertise or transient workforce, and develop systems and information that supports a business case for recreation in Iqaluit based on the evaluation criteria

The Sustainable Community Plan, 2017, is grounded in the spirit of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, which signifies the commitment made by the City of Iqaluit to incorporate Inuit knowledge and practices into planning decisions. According to Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, relationships hold significant importance as they form a fundamental aspect of life and are the very essence of community:

• Relationship to the environment

• Relationship to social and family wellbeing

• Relationship of the individual to his or her own inner spirit, for a productive society

The plan recognizes the deterioration of traditional trails and infrastructure shortfalls, resulting in a growing sense of disconnection within the community. The importance of being able to engage in various land and sea activities, including hunting, gathering, fishing, camping, boating, hiking, cycling, kayaking, snowmobiling, skiing, dog sledding, and sliding, is critical to the community’s survival and are cherished by all residents.

“We have winter and summer routes that connect us to our surroundings, as well as to the adjacent communities of Kimmirut and Pangnirtung. In the winter, local skidoo trails are used by hunters and recreationalists. These skidoo trails are often used by more than just snow machines– they are also used as groomed trails for walking, skiing and dog sledding. In the summer, we have ATV trails that run along the Sylvia Grinnell River, and branch off the Road to Nowhere” (PG. 9)

The plan presents a series of challenges that focus on the impact of continuing growth and urbanization of the city, including:

• The misuse of ATVs/Skidoos/4x4 vehicles that deteriorate the quality of the tundra in parks and green spaces

• Snowmobile trails need to be better managed at road crossings

• Changes in ice conditions, precipitation, and drainage patterns have amplified the hazards of hunting and recreation on land and sea

By acknowledging and embracing the TRC's Calls to Action, we commit ourselves to contributing to reconciliation, justice, and equality. Together, we can ensure that Indigenous voices are heard and respected in the decision-making processes. We strive to build a better and more harmonious society for present and future generations, one that respects and honours the rights, cultures, and aspirations of Indigenous peoples

20. In order to address the jurisdictional disputes concerning Aboriginal people who do not reside on reserves, we call upon the federal government to recognize, respect, and address the distinct health needs of the Métis, Inuit, and off-reserve Aboriginal peoples.

45. We call upon the Government of Canada, on behalf of all Canadians, to jointly develop with Aboriginal peoples a Royal Proclamation of Reconciliation to be issued by the Crown. The proclamation would build on the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Treaty of Niagara of 1764, and reaffirm the nation-to-nation relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Crown. The proclamation would include, but not be limited to, the following commitments:

i. Repudiate concepts used to justify European sovereignty over Indigenous lands and peoples such as the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius.

ii. Adopt and implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as the framework for reconciliation.

iii. Renew or establish Treaty relationships based on principles of mutual recognition, mutual respect, and shared responsibility for maintaining those relationships into the future.

iv. Reconcile Aboriginal and Crown constitutional and legal orders to ensure that Aboriginal peoples are full partners in Confederation, including the recognition and integration of Indigenous laws and legal traditions in negotiation and implementation processes involving Treaties, land claims, and other constructive agreements.

88. We call upon all levels of government to take action to ensure long-term Aboriginal athlete development and growth, and continued support for the North American Indigenous Games, including funding to host the games and for provincial and territorial team preparation and travel

89. We call upon the federal government to amend the Physical Activity and Sport Act to support reconciliation by ensuring that policies to promote physical activity as a fundamental element of health and well-being, reduce barriers to sports participation, increase the pursuit of excellence in sport, and build capacity in the Canadian sport system, are inclusive of Aboriginal peoples.

Municipalities consider physical infrastructure assets such as roads, bridges, public buildings, parks, water supply systems, sewage systems, public transportation systems, and other public facilities that support the community's needs. The City does not treat the current trail and pathway network in the city as an asset, as it has evolved over time and has not required financial investment and minimal maintenance. What are identified in the City’s current GIS data set are the routes used by pedestrians and snow mobiles in the City, not physical infrastructure.

As Iqaluit experiences both community and capital city growth, with a population increase of over 15% since 2011, its residents are confronted with the challenge of deteriorating and insufficient infrastructure. The trail system is also confronted with the challenge of being insufficient for the demand and deteriorating from overuse.

The improper use of motorized vehicles and the presence of informal trails have led to the degradation of the fragile tundra landscape. Essential elements such as trail heads, markers, directional and distance indicators, clear sightlines, separation of different modes of transportation, and direct connections between important destinations are conspicuously absent.

Trails and pathways should be a valuable community asset that plays a vital role in the lives of Iqaluit's residents. Consistently trails and pathways are identified as being one of the most valuable assets for citizens. Historically in Iqaluit, these pathways served as essential links, connecting communities - by boats, by walking, and by sleds - enabling people to access necessary resources for survival. The future vision for Iqaluit is to establish a strengthened network of trails and pathways that will not only revive cultural heritage but also enhance connectivity to the City's distinct natural and built environment.

Through a spectrum of studies including background review, examination of current conditions of trails, trends, and best management practices, a set of key issues and opportunities emerged. These are listed below:

ISSUES

• Clear distinguishable sidewalks are limited, pose a health and safety risk

• Limited accessible routes and wayfinding throughout the city

• Existing conflicts between users and various modes of transportation

• Unsafe roadway crossing conditions for snowmobilers

• Lack of informational and educational signage

• Lack of wayfinding signs

• The degradation of tundra in parks and green spaces due to misuse of misuse of ATVs/ Skidoos/4x4 vehicles and pedestrian traffic

• Climate change is impacting seasonal trail use and trail maintenance

• Growing sense of disconnection and isolation from the loss of traditional ways of knowing

OPPORTUNITIES

• Improve connectivity between downtown core, recreational facilities, adjacent communities, parks, and open spaces

• Formalize trail routes to provide added safety and protection by clearly defining trails for different modes of transportation

• Propose loop circulation routes that connect critical points of interest

• Optimize public safety by reducing conflicts between snowmobiles, ATVs, pedestrians and cyclists

• Establish a hierarchy of trails and pathways that meet the criteria for accessible routes

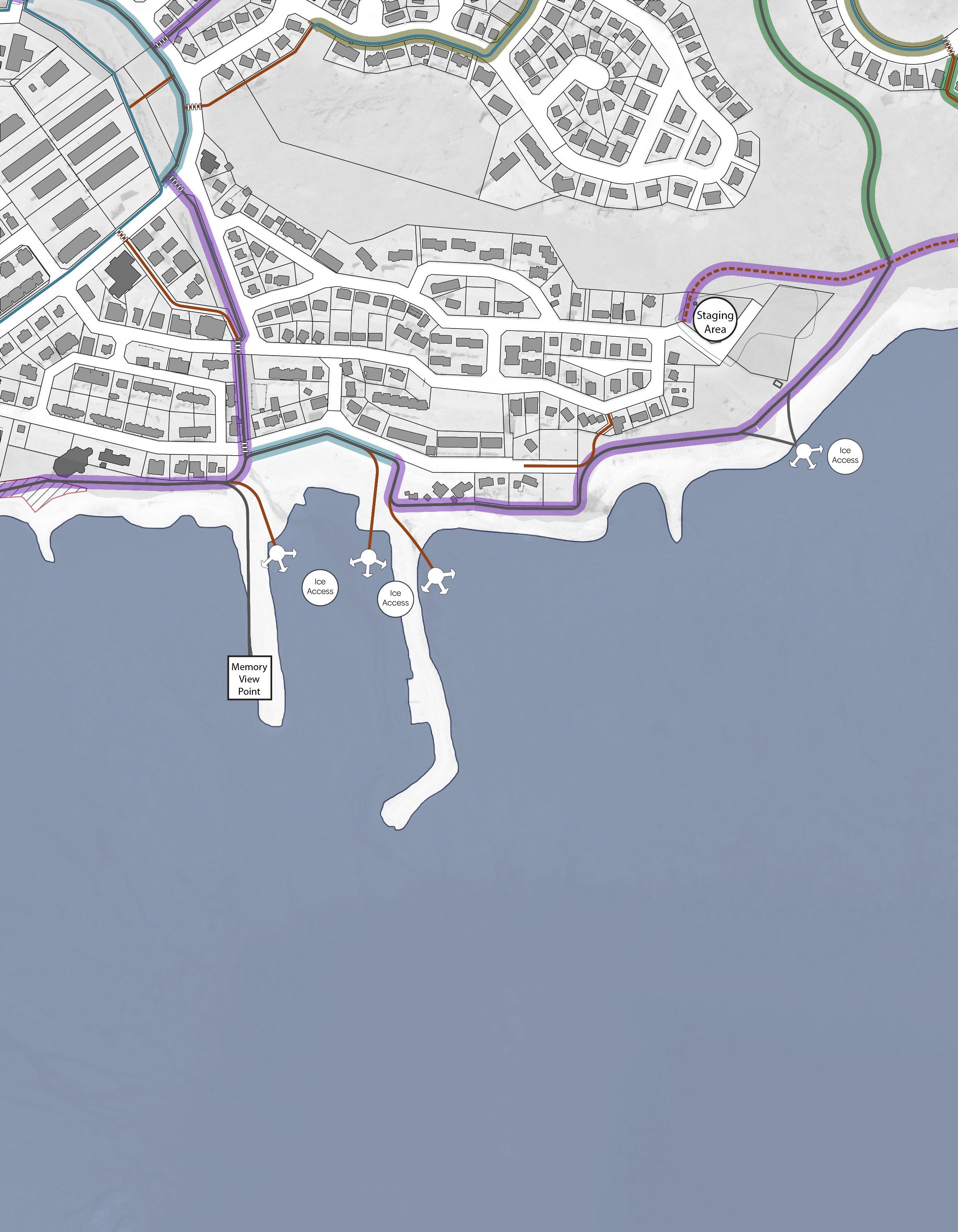

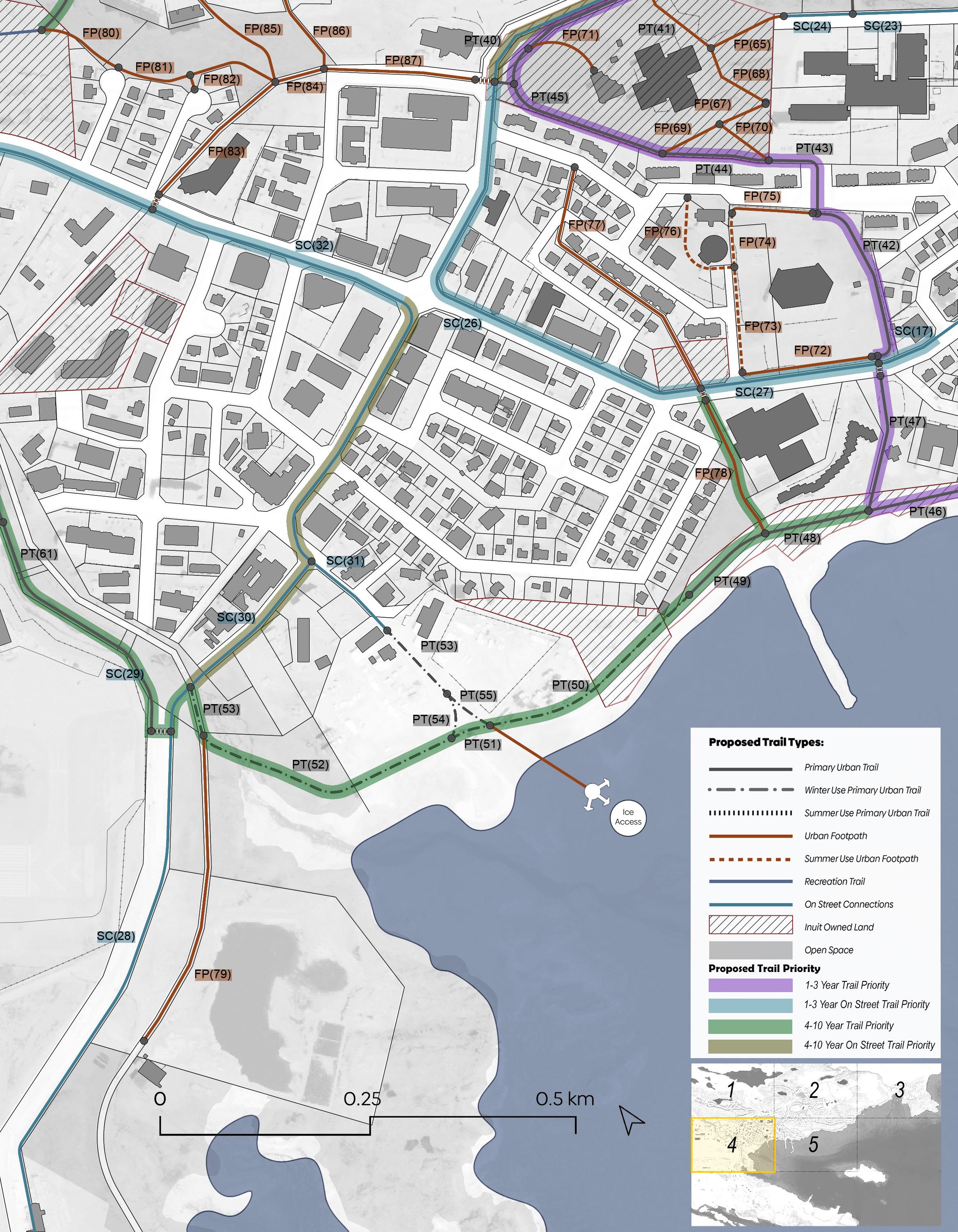

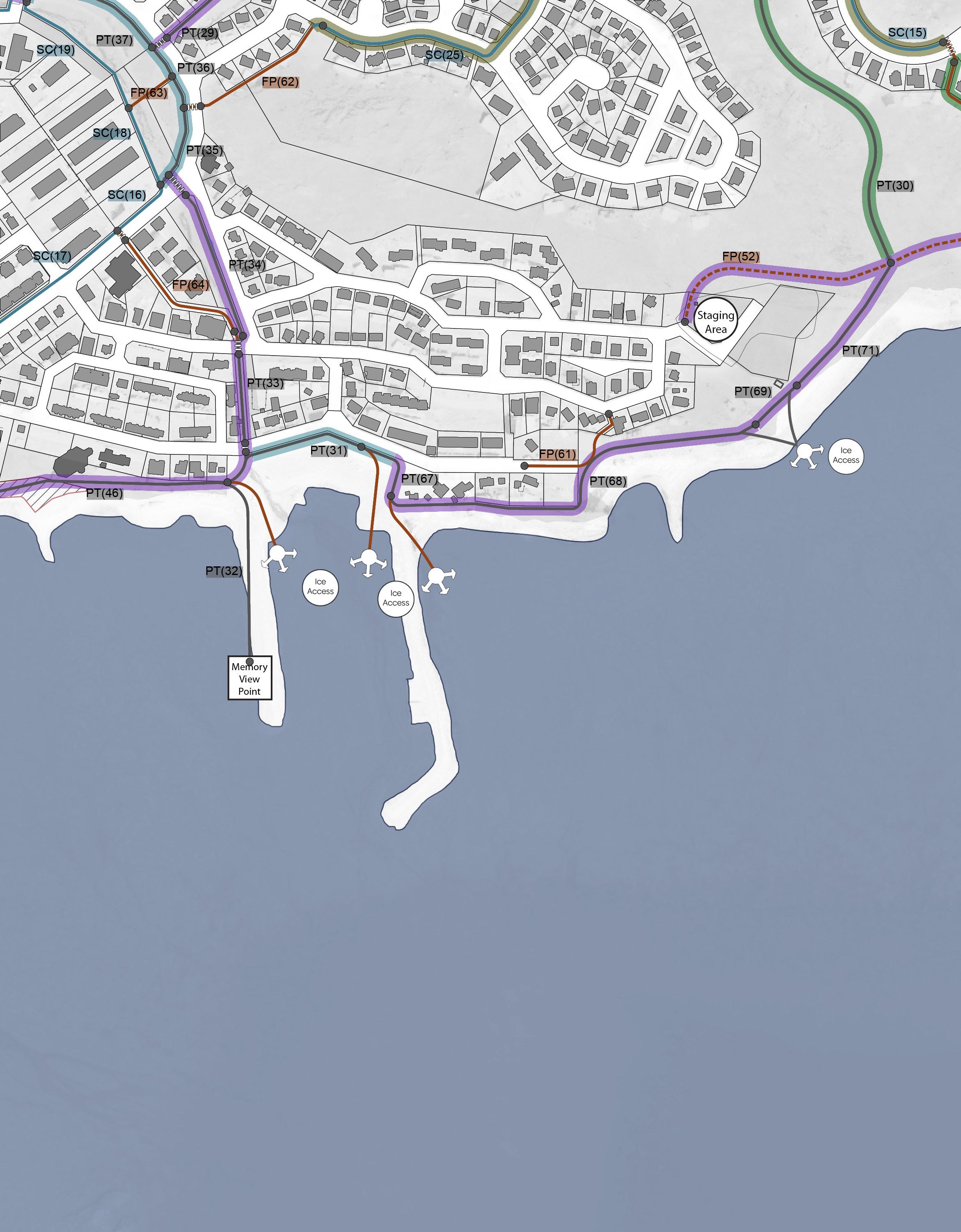

• Establish a linear pathway along the waterfront, building on the relationship with the land, sea and ice

• Enhance and protect the linkage to Apex trail to celebrate the city of Iqaluit's natural environment as a tourist destination

• Improve connection to public parks, such as Geraldine Creek, providing access to public recreation spots and beautiful spaces to gather

• Improve signage and wayfinding to promote traditional values and activities

• Recognize and celebrate Indigenous traditional trail names and heritage routes

• Propose innovative ways to protect the natural environment through sustainable trail design strategies

E-bikes have had a significant impact on trail planning and management in recent years. Here are some ways in which e-bikes have influenced trail planning:

1. Access and Designation: The growing popularity of e-bikes has prompted many trail managers and land agencies to reevaluate their policies and designations for different types of trails. They are considering whether e-bikes should be allowed on specific trails, including paved pathways, shared-use paths, multiuse trails, or single-track mountain bike trails. Some jurisdictions have created new designations, such as "Class 1" or "Class 1-3" trails, to accommodate different types of e-bikes.

2. Trail Classification: E-bikes have led to discussions about the classification and differentiation of trails based on the speed and power capabilities of e-bikes. Trail managers are considering factors such as trail difficulty, erosion control, user safety, and user experience when classifying trails for e-bike use.

3. User Conflict and Safety: E-bikes can travel at higher speeds than traditional bicycles, which can potentially lead to user conflicts and safety concerns on narrow or crowded trails. Trail planners are addressing these concerns by implementing measures such as speed limits, signage, and trail widening to enhance safety for all users.

4. Infrastructure and Maintenance: E-bikes, especially those designed for off-road or mountain biking, can put additional strain on trail infrastructure and require more maintenance. The increased weight and torque of e-bikes can accelerate trail erosion and wear. Trail managers may need to assess and adjust their maintenance practices to ensure trails can handle the demands of e-bikes.

5. Trail Advocacy and Engagement: E-bike riders, along with traditional cyclists and hikers, have become active advocates in trail planning and management discussions. E-bike user groups and organizations are working to ensure fair access to trails while also promoting responsible riding practices and environmental stewardship.

It's worth noting that the impact of e-bikes on trail planning can vary depending on local regulations, trail systems, and the preferences of different user groups. As e-bike technology continues to evolve and gain popularity, ongoing discussions and adaptations in trail planning will likely take place to address the unique needs and challenges associated with e-bike use

When it comes to restricting e-bikes from urban trails, several arguments are often put forward. It's important to note that these arguments may vary depending on local perspectives, regulations, and the specific characteristics of the trail system. Here are some common arguments made for restricting e-bikes from urban trails:

1. Safety Concerns: One of the primary arguments is related to safety. Some argue that e-bikes, with their higher speeds and potentially greater mass, can pose a safety risk to pedestrians, especially in crowded urban environments. Concerns may arise due to the potential for accidents, collisions, or conflicts between e-bike riders and pedestrians, particularly on narrower or heavily trafficked trails.

2. User Conflict: Restricting e-bikes from urban trails may be seen as a way to mitigate user conflicts. Pedestrians, joggers, and slower cyclists may feel uncomfortable or threatened by the presence of e-bikes due to the speed differential or the perception of less control. Restricting e-bikes from certain trails can help maintain a peaceful and harmonious environment for other trail users.

3. Trail Degradation: Critics argue that allowing e-bikes on urban trails can lead to increased wear and tear on the trail surfaces. E-bikes, with their potentially heavier weight and increased speeds, may cause greater impact on trails, accelerating erosion and requiring more frequent maintenance and repairs.

4. Trail Capacity and Congestion: Urban trails, particularly those in densely populated areas, may already face issues of overcrowding and limited capacity. Some argue that allowing e-bikes could exacerbate these issues by introducing more users and potentially fastermoving traffic. Concerns may be raised regarding trail congestion and reduced enjoyment for all users.

5. Conservation and Environmental Impact: Urban trails often traverse natural areas or parks with sensitive ecosystems. Opponents of e-bike access may argue that the presence of motorized vehicles, even electric ones, can disturb wildlife, damage habitats, or disrupt the tranquility of these natural spaces.

6. Traditional Trail Use and Character: Some argue that urban trails have historically been designated and designed for nonmotorized activities such as walking, jogging, or cycling. Restricting e-bikes may be seen as a way to preserve the intended character and experience of these trails.

CLASS 1: E-bikes are pedal-assist models with motors that work only while the rider is pedaling. They have a top speed of 20 mph, at which point the motor automatically disengages. While riders can go faster, any speeds above 20 mph are courtesy solely of the rider’s muscle power.

CLASS 2: E-bikes have a throttle, allowing the motor to power the bike even without the rider pedaling. The motor stops providing assistance at speeds in excess of 20 mph.

CLASS 3: E-bikes are the most powerful; again pedal-assisted, these bikes can reach 28 mph before the motor stops providing power.

Typically, when e-bikes are allowed on multiuse trails, they have been Class 1 and 2, and subject to the same rules and regulations that govern other cyclists.

The current number of constructed trails in the City of Iqaluit is very limited. A few hundred meters of trail has been built or is under construction around Imiqtarviminiq Lake (formerly Dead Dog Lake). There is also a short section built along the creek between Nipisa St. and Sinaa. Recently the City has begun to maintain a trail within the Geraldine Creek corridor from the Frob Bridge to Queen Elizabet Dr. This trail is having a significant impact on the natural landscape and the aesthetic appeal of the creek. Too few complete, easily maintained trails are proving to be problematic.

The existing trails have been constructed by stripping away organic material and laying geotextile material with approximately 100mm of crushed gravel over it. The trails are approximately 2.0m wide.

Trails provide numerous benefits to the community, both in terms of recreation and transportation. Here are some reasons why trails and pathways are valued assets:

• Trails provide Recreation and improve Quality of Life: Trails and pathways offer opportunities for outdoor recreation, such as walking, jogging, and cycling. They provide a safe and accessible space for residents to engage in physical activity, promoting health and well-being. These recreational amenities contribute to the overall quality of life within a community.

• Connectivity and Mobility: Trails and pathways can connect different neighborhoods, parks, schools, and other important community destinations. They provide alternative modes of transportation for pedestrians and cyclists, reducing dependency on motor vehicles and promoting active transportation. Well-connected trail networks improve mobility, accessibility, and promote a sense of community.

• Tourism and Economic Development: Trails and pathways often attract visitors and tourists who are interested in outdoor activities and exploring natural or cultural attractions. This can boost local tourism and contribute to the local economy through visitor spending on accommodations, dining, and retail. Additionally, trails can enhance property values in nearby areas, attracting businesses and residential development.

• Environmental Benefits: Trails and pathways can be designed to preserve and showcase natural landscapes, green spaces, and biodiversity. They can serve as corridors for wildlife and contribute to the conservation of ecosystems. By providing opportunities for people to connect with nature, trails and pathways promote environmental stewardship and foster a sense of appreciation for the natural environment.

• Community Engagement and Social Cohesion: Trails and pathways act as gathering spaces and promote social interactions among community members. They provide opportunities for people to meet, exercise together, and engage in group activities. These shared spaces foster a sense of belonging, social cohesion, and community pride.

• Health and Active Living Initiatives: Municipalities recognize the importance of promoting active living and combating sedentary lifestyles. Trails and pathways align with health and wellness initiatives by encouraging physical activity and making it easier for residents to incorporate exercise into their daily routines.

For all the right reasons, The City of Iqaluit would be wise to invest in the planning, development, and maintenance of trails and pathways as part of the overall infrastructure and community development strategy.

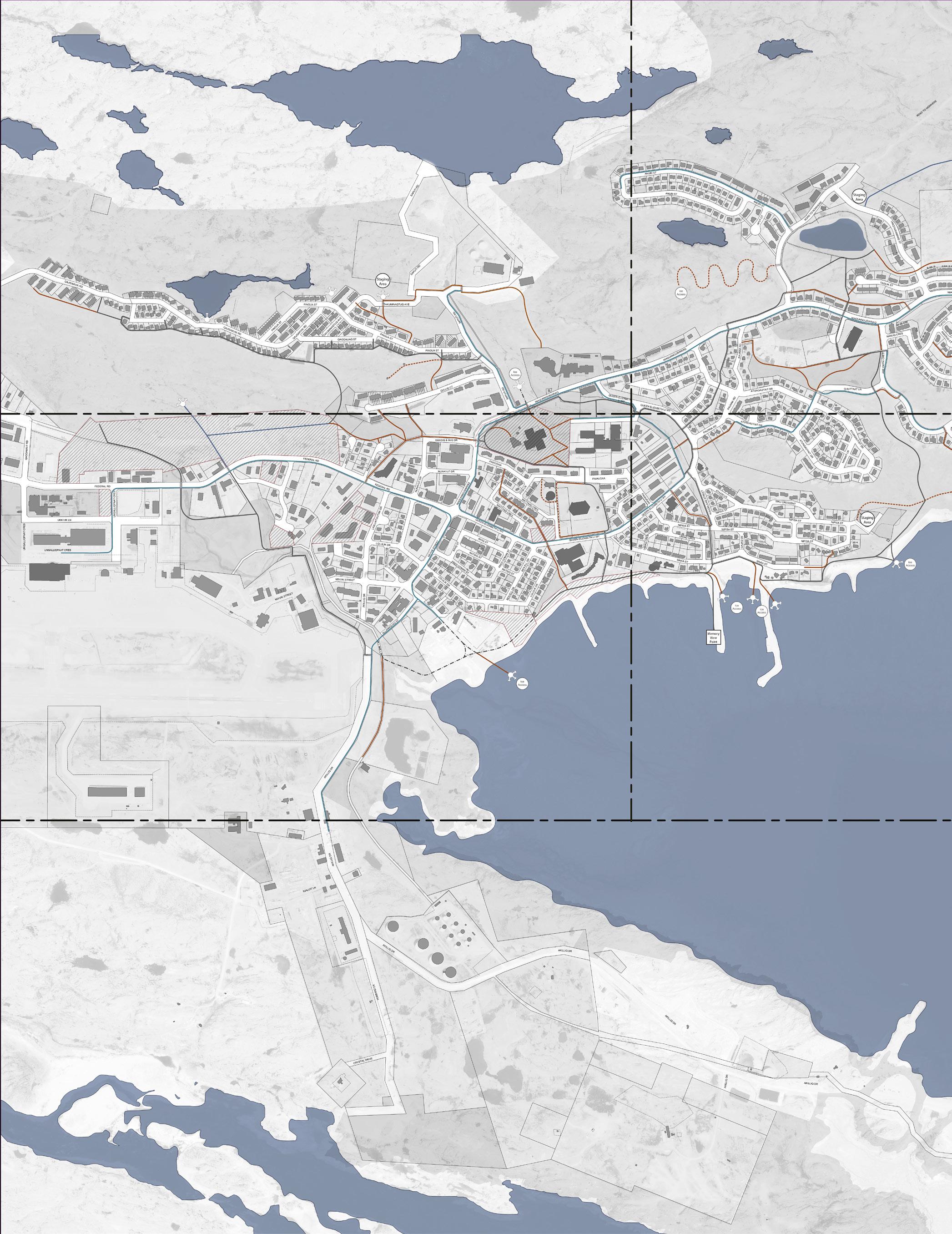

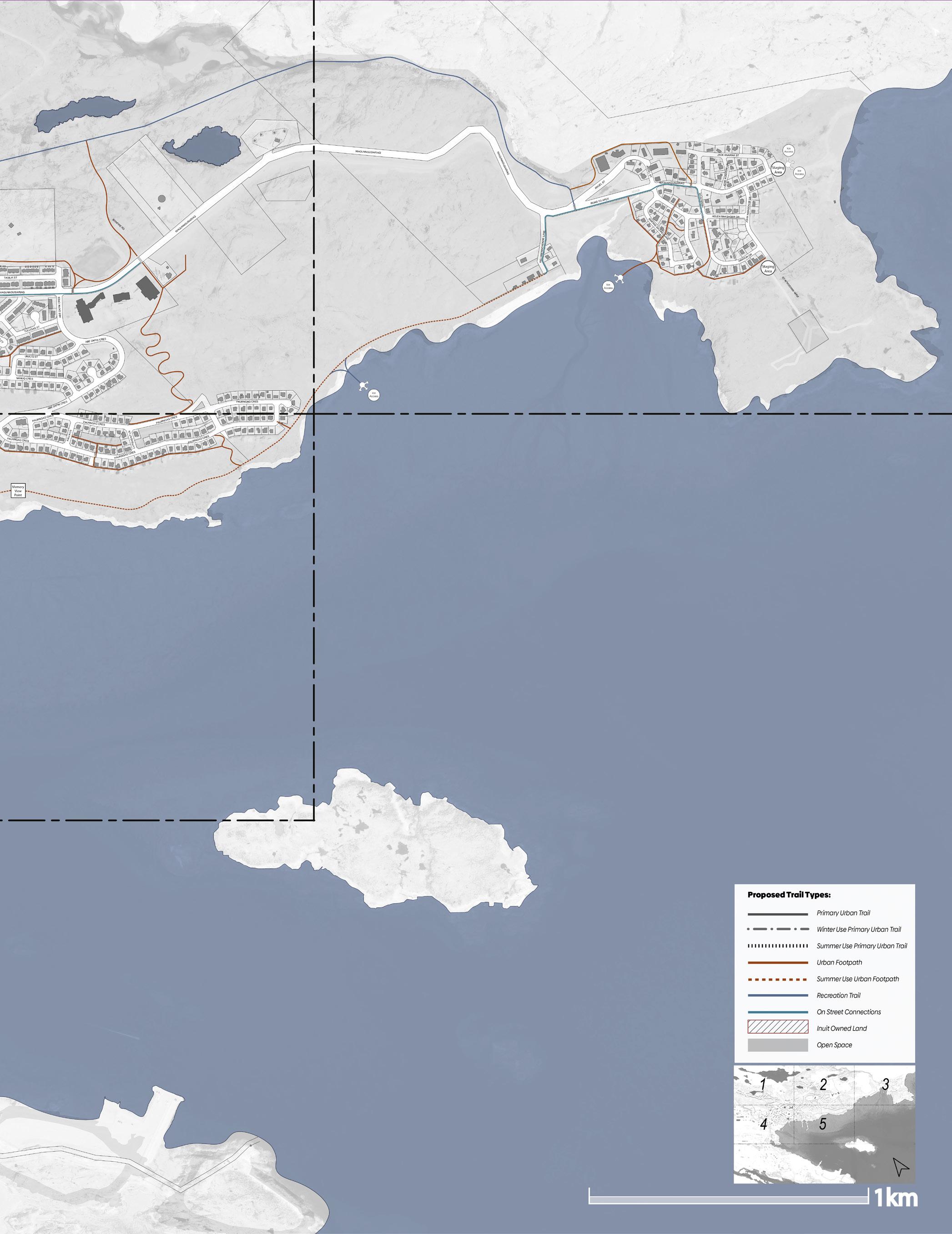

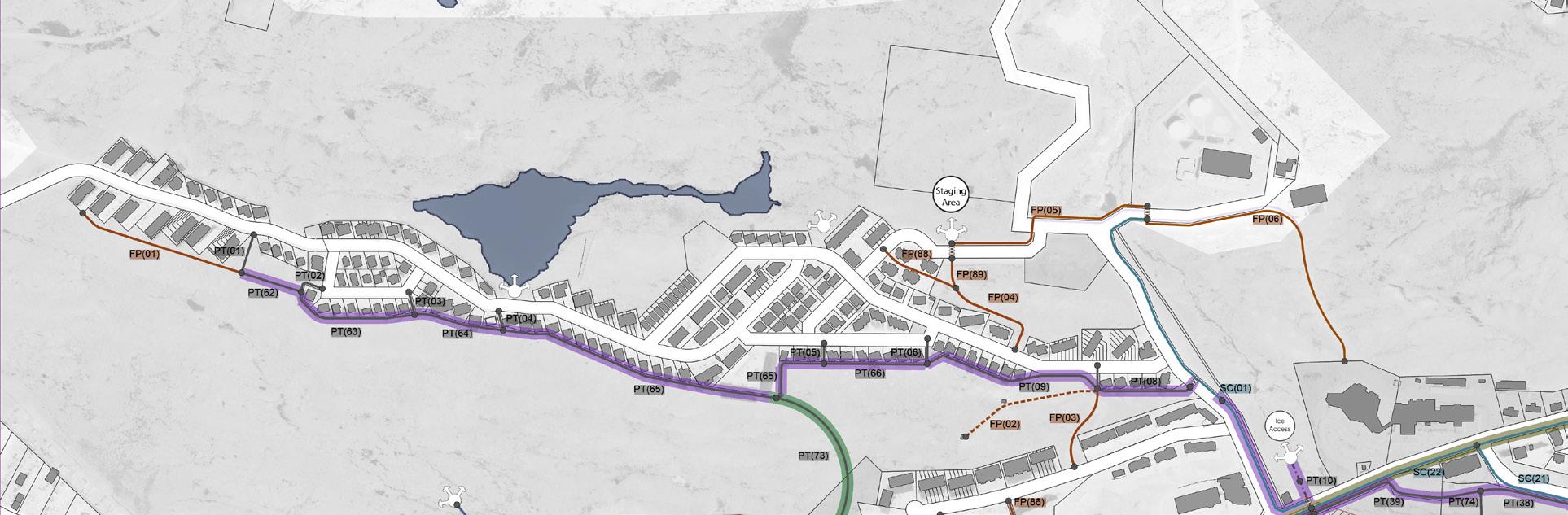

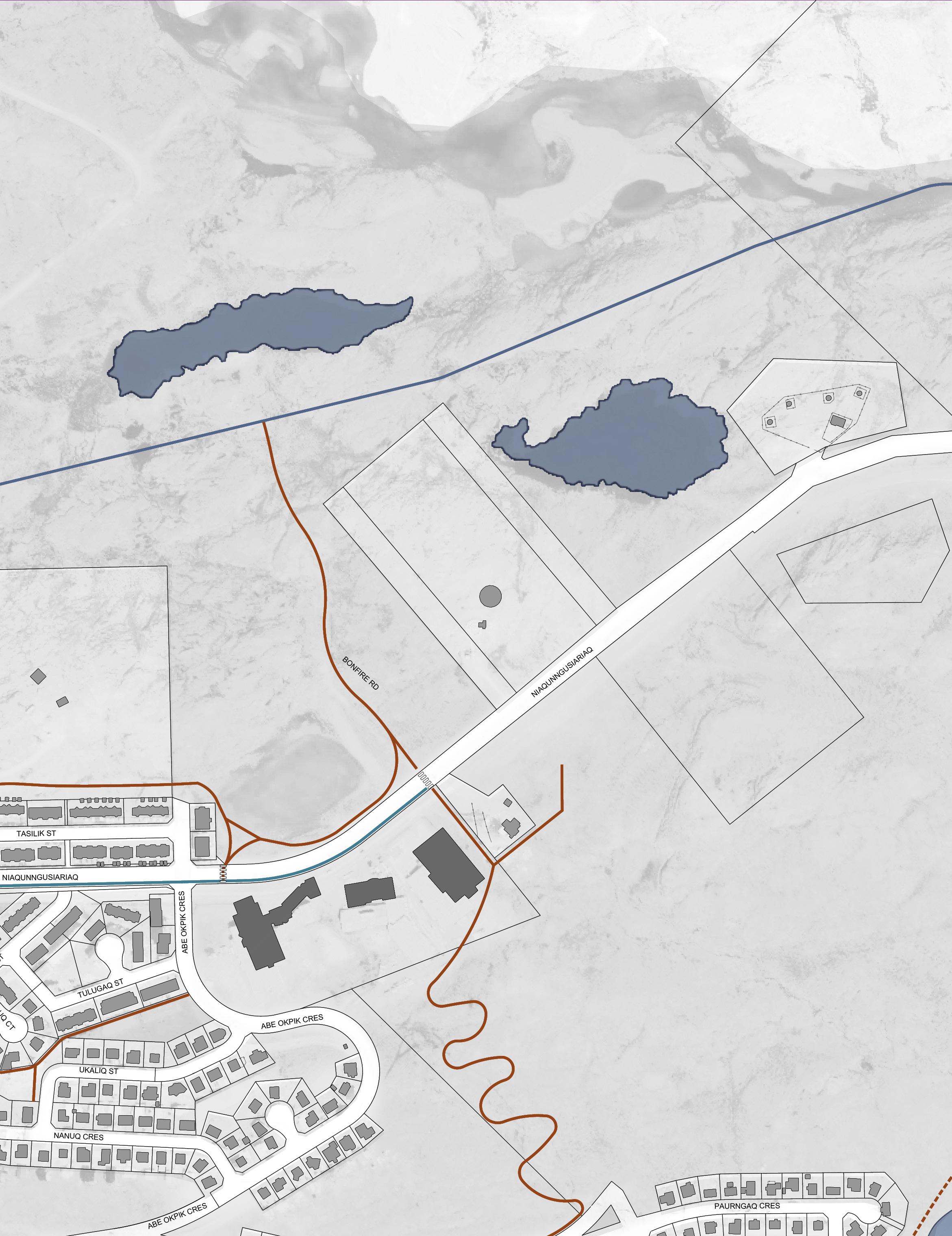

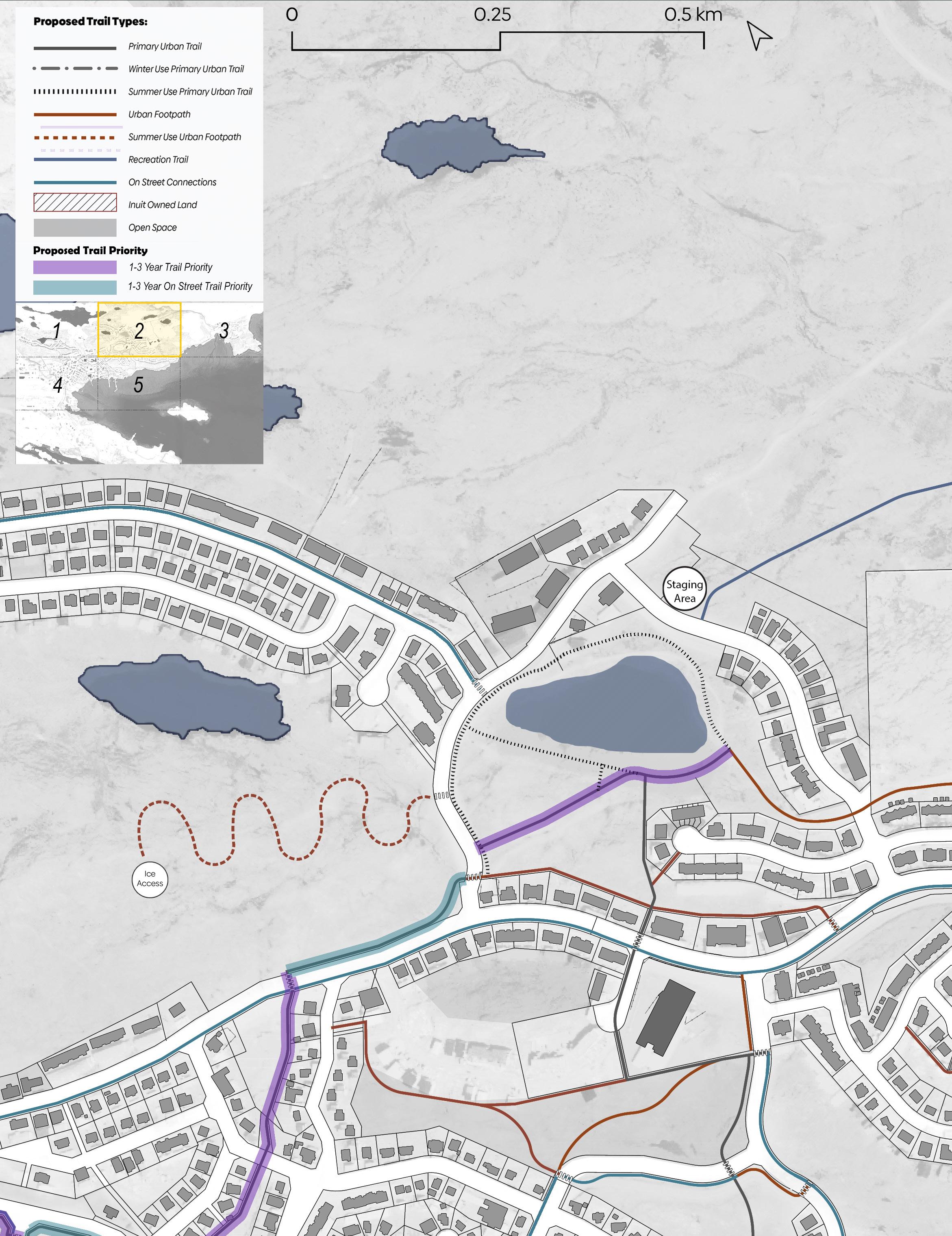

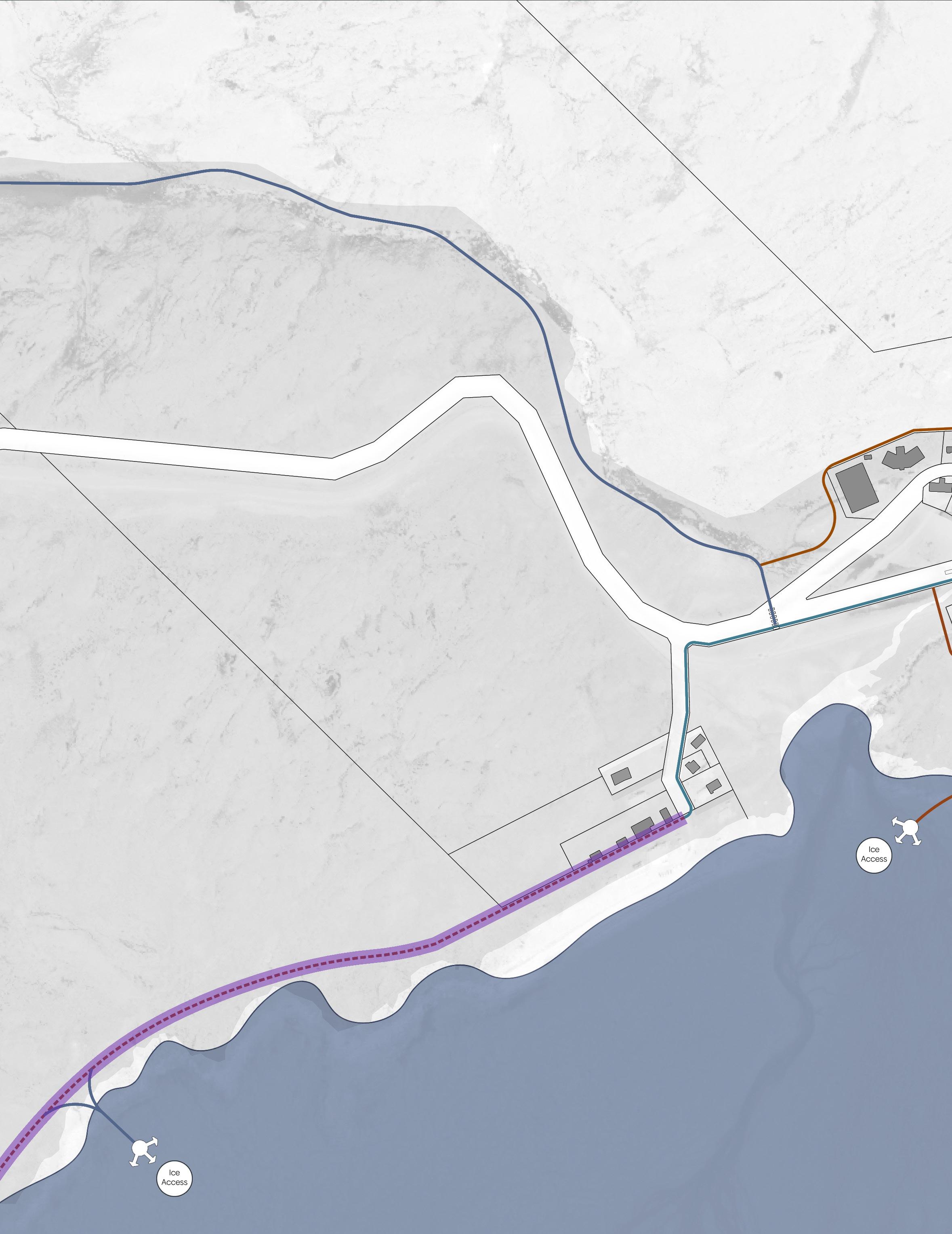

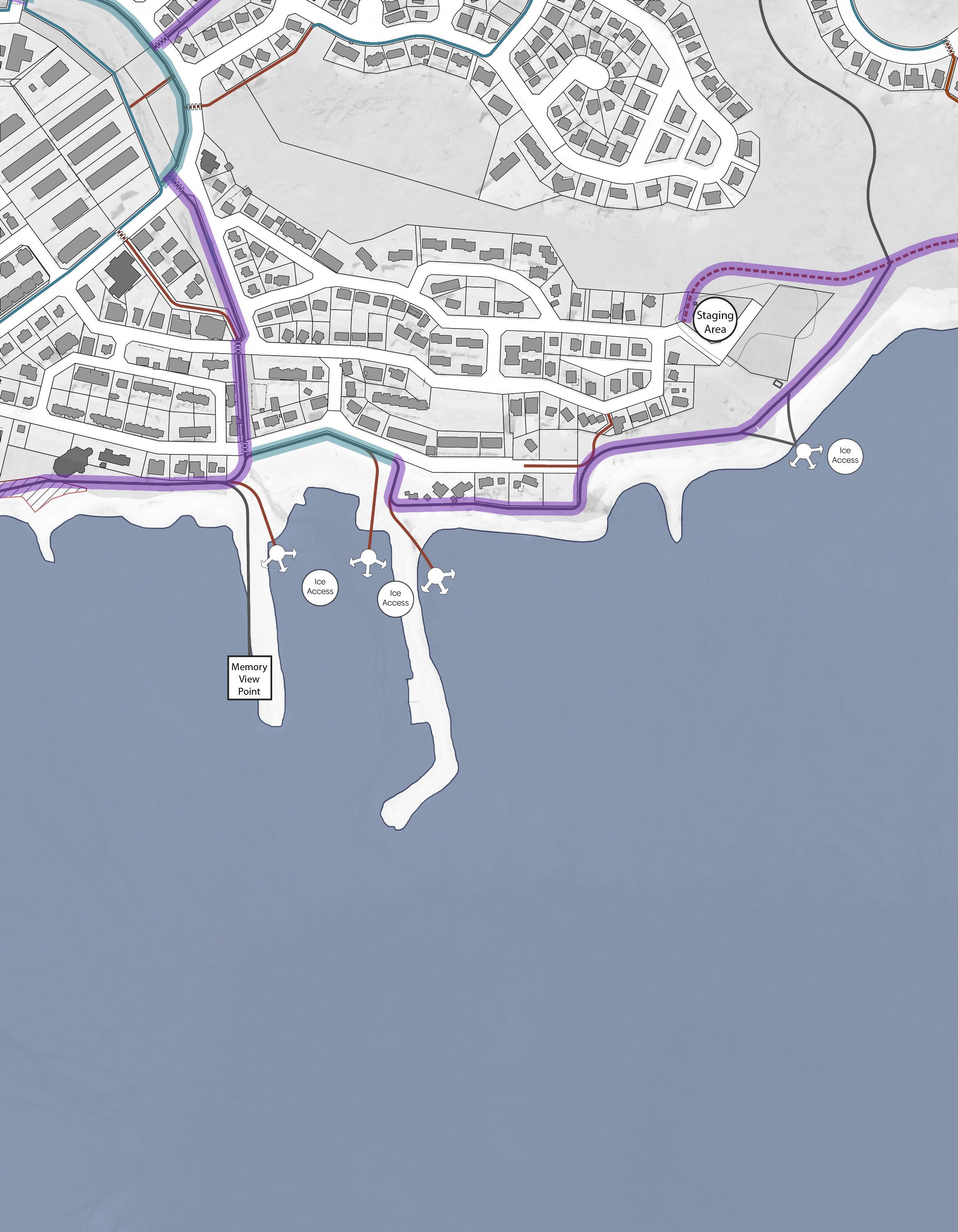

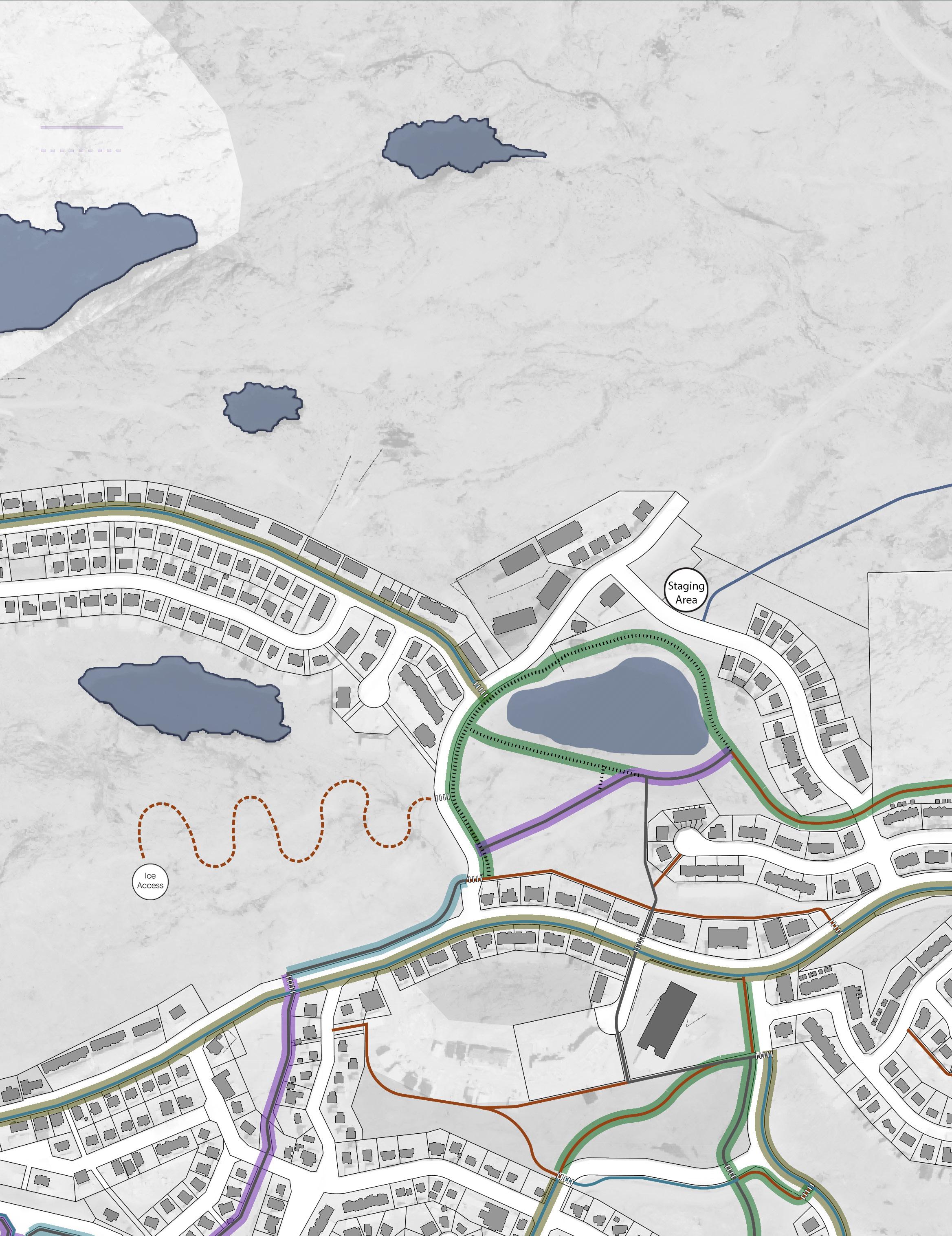

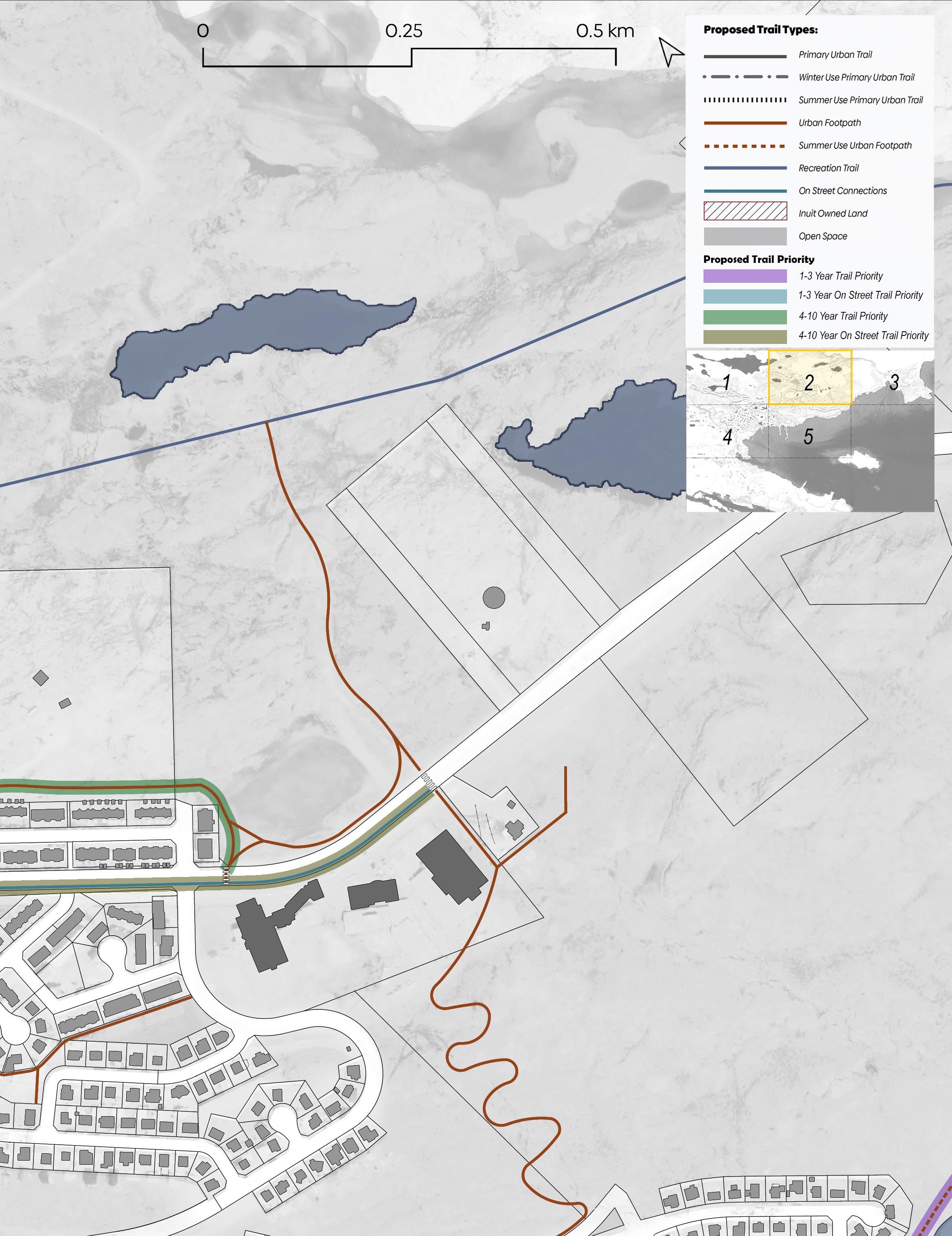

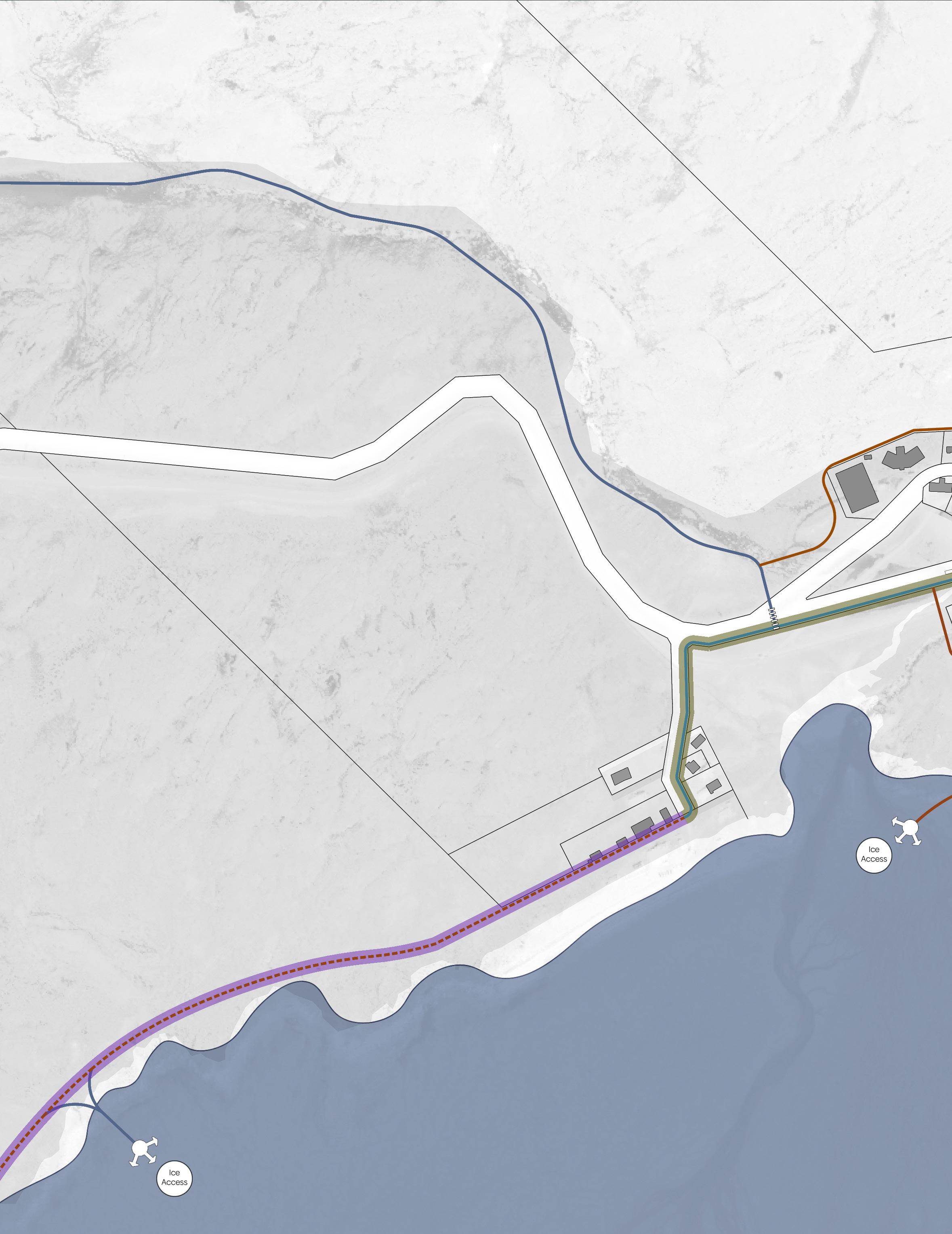

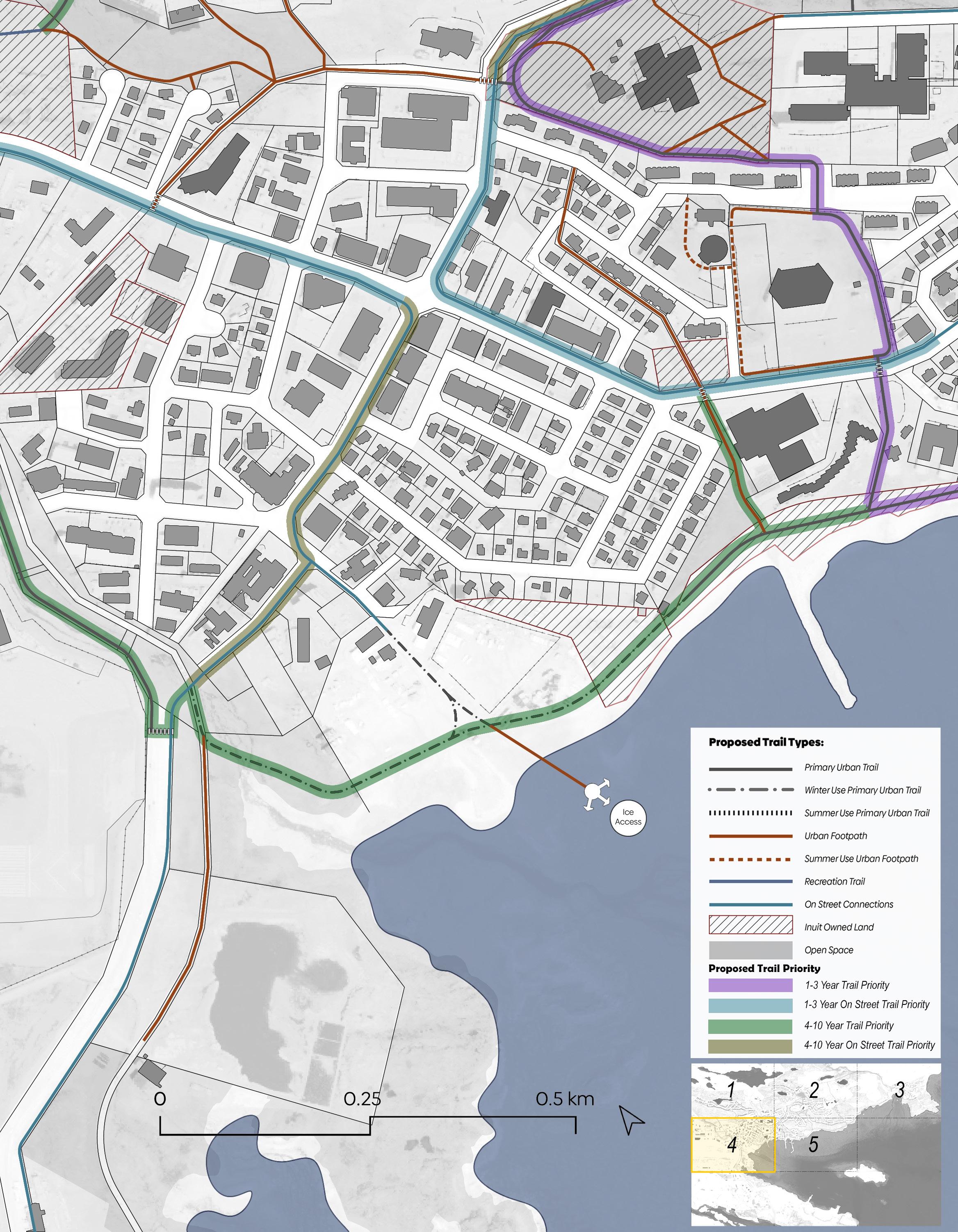

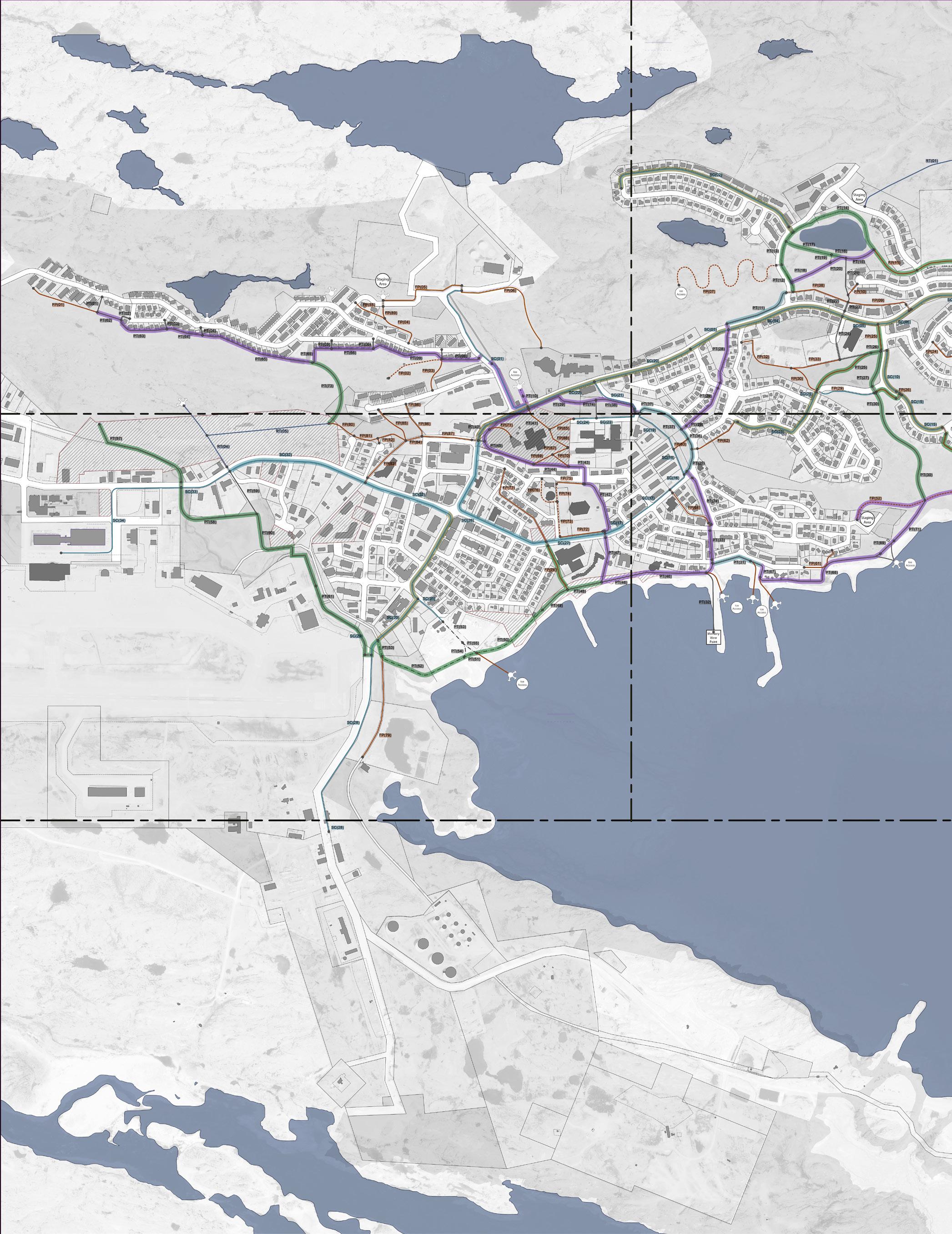

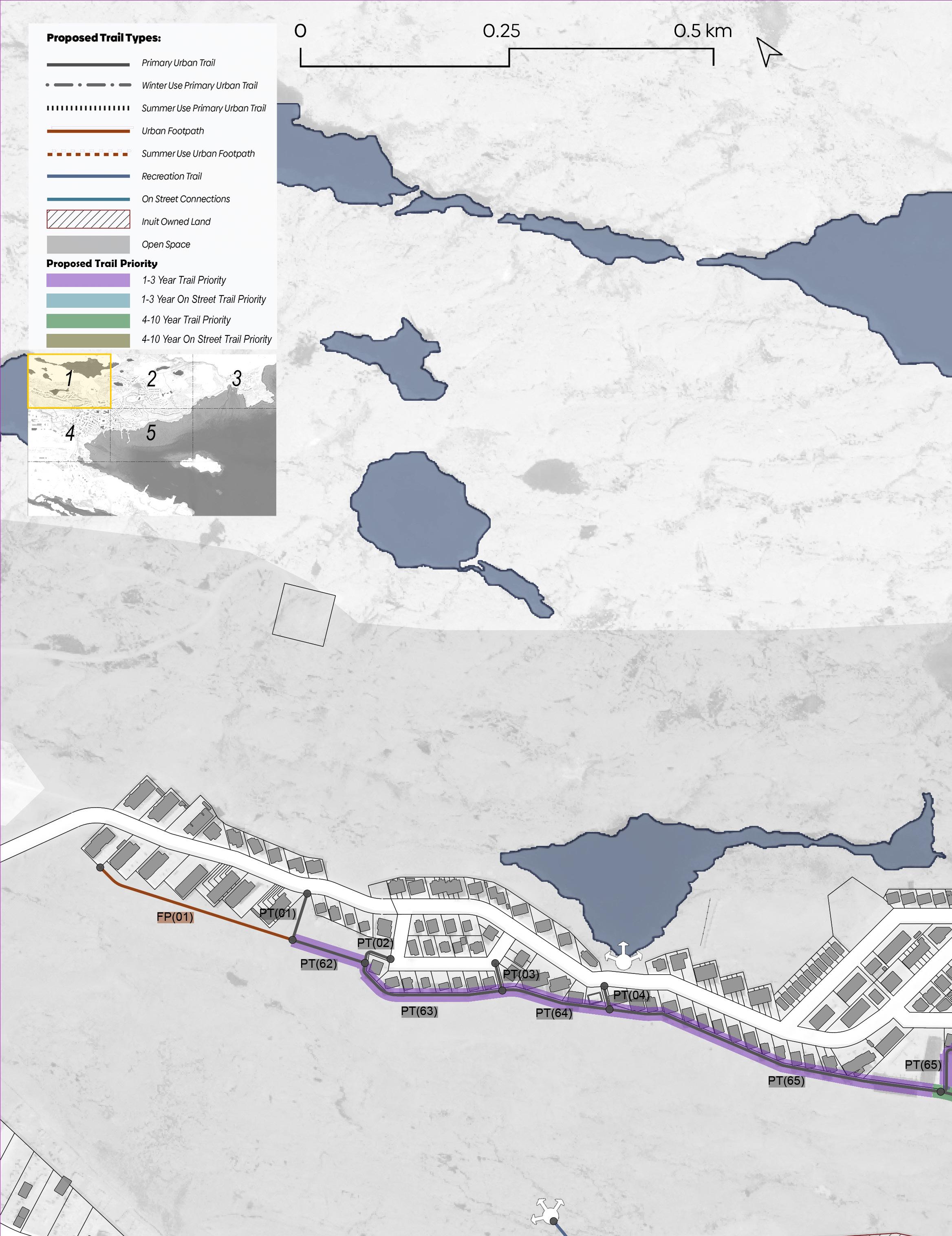

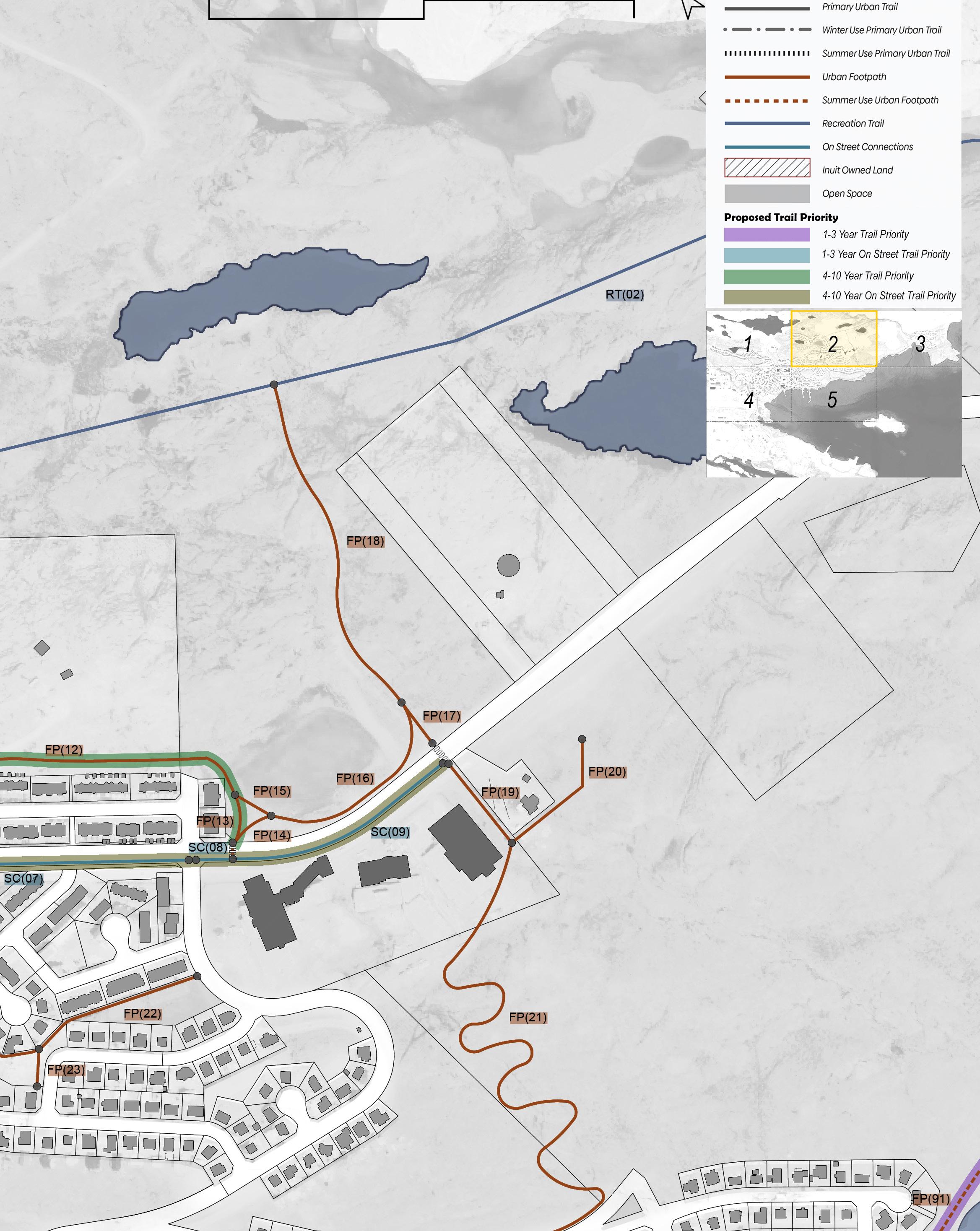

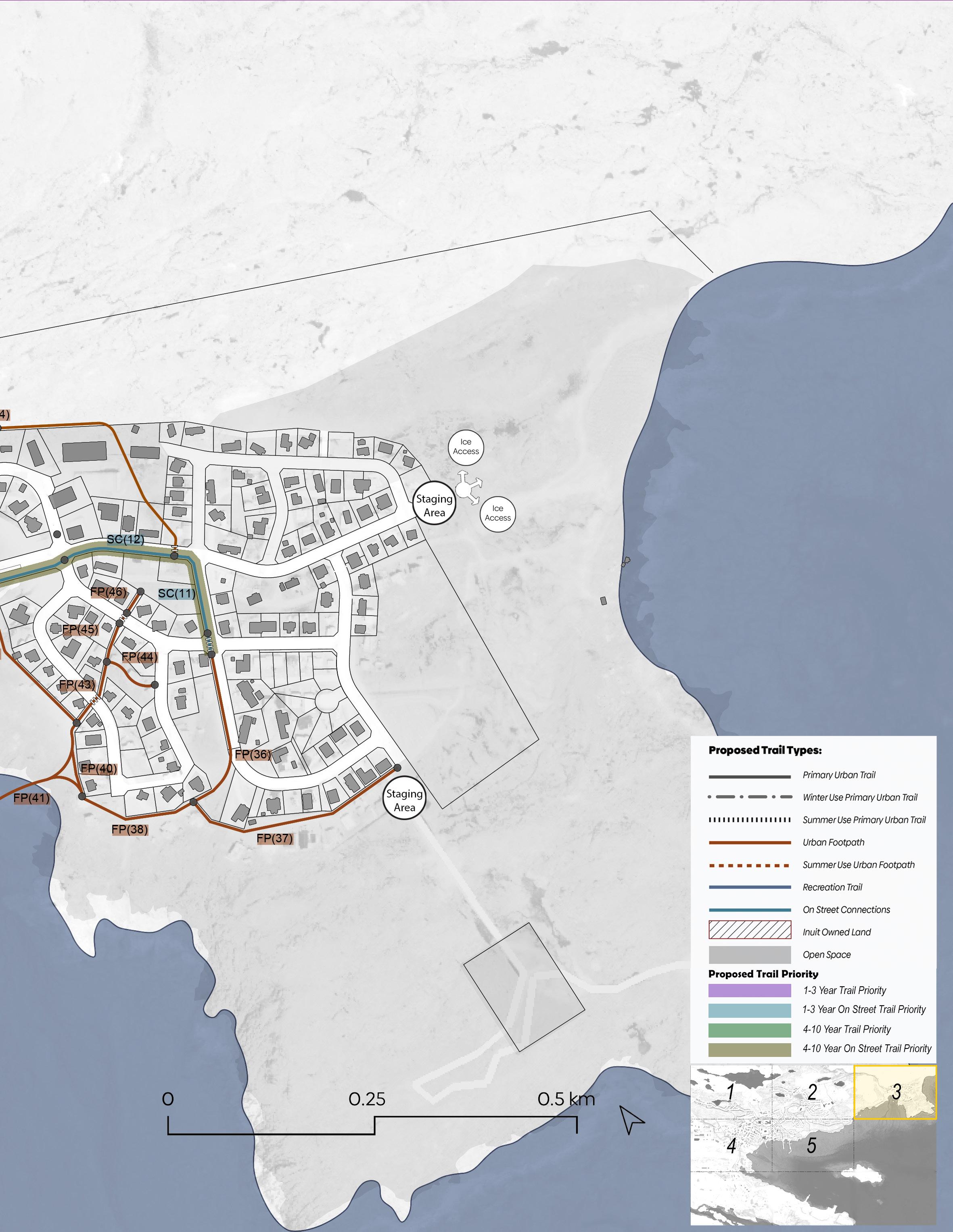

The proposed Trail System is intentionally built upon a hierarchy of trails and transportation corridors that primarily makes use of current Open Space in the City. The Plan does not direct, but only suggests, where multimodal facilities should be developed within the Road Right of Ways to ensure connectivity does occur. In this way, the primary work of the Plan stays within the jurisdiction of Parks and facilitates safe transportation practices. The plan also identifies the location of formal road crossings for snowmobile traffic, and the proposed location of staging areas.

The key principles of the Trails Plan are:

1. To develop trails only in public open space and parks.

2. To create trail routes for summer and winter use, (unless otherwise indicated.)

3. To create trails that are multi-modal, (unless otherwise indicated).

4. To regulate Snowmobile speed limits and other restrictions, within City Open Spaces.

5. To designate winter road crossings for snowmobiles.

6. To limit ATVs to roads, and not on trails.

Today, snowmobiles have become a primary means of traversing the land to access hunting grounds, travel between camps, and visit neighbouring communities. Snowmobile travel is predominantly undertaken during the winter months, spanning from October to July, and is contingent upon factors such as snow presence, depth, and quality. While local snowmobile trails serve both hunters and recreationalists, they frequently pass through private property. Recognizing the necessity for improved trail management, the city has emphasized the importance of effectively regulating these informal trails, particularly at road crossings, to prevent conflicts between various types of motorists.

The widespread availability of personal snowmobiles during the 1960s brought significant changes to the lives of Iqalummiuts, altering traditional hunting, herding, and trapping practices among the Inuit. The dominance of snowmobiles over dog sleds stemmed from governmental policies and settlement conditions that made it difficult or impossible for individuals to maintain dog ownership within communities. The shift towards snowmobiles enabled hunters to traverse the landscape at a faster rate, replacing stealth-based hunting techniques. The use of snowmobiles also required traveling with a partner for safety reasons in the event of mechanical failures. This differed from the traditional practice where Inuit hunters had the freedom to travel independently.

In a trails master plan, there are several destinations that are typically considered critical to ensure connectivity, accessibility, and the overall functionality of the trail network. These destinations can vary depending on the specific community and its needs. Here are some common examples:

1. Parks and Natural Areas: Including local, regional, and national parks, as well as natural areas, preserves, and green spaces. These destinations provide opportunities for recreation, leisure, and access to natural environments.

2. Schools and Educational Institutions: Trails connecting schools, colleges, and universities are important for promoting active transportation among students and staff. They enhance safety and provide convenient routes for walking or cycling to educational facilities.

3. Residential Areas: Trails that pass through or connect residential neighborhoods are critical for promoting active transportation, providing residents with convenient and safe access to community amenities, such as parks, schools, shopping areas, and public transportation hubs.

4. Commercial and Business Districts: Connecting trails to commercial and business areas encourages walking or cycling as an alternative mode of transportation for shopping, dining, and accessing services. This can help reduce traffic congestion and promote local economic development.

5. Transit Stations: Integrating trails with transit stations, such as bus stops, train stations, or subway stations, provides seamless multi-modal transportation options. It enables commuters to easily switch between walking, cycling, and public transportation, enhancing overall accessibility and connectivity.

6. Community Facilities: Trails that lead to community centers, libraries, health centers, senior centers, and other public facilities enhance accessibility to essential services and promote community engagement.

7. Tourist and Cultural Attractions: Trails connecting tourist destinations, historical sites, cultural landmarks, museums, art galleries, and other points of interest encourage visitors to explore the area on foot or by bicycle. These destinations contribute to tourism and can stimulate economic activity.

8. Employment Centers: Connecting trails to major employment centers, industrial areas, and business parks facilitates active commuting options and reduces reliance on private vehicles. It promotes a healthier and more sustainable transportation approach.

9. Waterfronts and Scenic Areas: Trails along rivers, lakes, coastlines, and other scenic areas provide opportunities for scenic walks, cycling, and recreational activities. They offer beautiful views and access to water-based activities.

10. Interconnected Trail Systems: Establishing connections between different trail systems within and beyond the municipality's boundaries is crucial for regional connectivity. These connections can facilitate long-distance hiking or cycling routes and contribute to regional tourism.

The destinations identified along with other considerations such as current businesses were considered during the planning process. The destinations were categorized according to the following on the map.

Groceries/Shopping Schools

Community Centres

Sports Facilities Cemetery Hospital Museum Police Station Post Office Church Gas Station Public Service/Government Building Airport

According to the City of Iqaluit General Plan, the definition of open space is defined as follows:

“The Open Space designation is intended to restrict most types of development and link open spaces to form access corridors to the land and sea. Open Space areas include the shoreline, beach areas, large parks, and those portions of the Walking Trail system not located in the road right of way. Most of the land within the Open Space designation is Commissioner’s Land.” (PG. 45)

“Uses permitted in the Open Space designation will be primarily recreational facilities with no associated buildings, such as playgrounds, parks, playing fields, walking trails, natural areas, camping and tenting areas.” (PG. 46)

“Parks will be permitted within all land use designations except those used for or adjacent to solid waste management and/or sewage treatment facilities.” (PG. 48)

“New residential development areas will have a minimum of 100 square metres of “tot lots” and active play parks for every 30 households."

The space will be configured and located so that (PG 48):

A. All residences in the development area are within 300m of a “tot lot” (play area and structures targeted for children 5 years and under). The walk to the “tot lot” will not involve crossing an Arterial Road and will avoid, wherever possible, the crossing of a Collector Road

B. All residences in the development area are within 750m of a neighbourhood park for older children and youth, which will include a formal playing-field, rink or court, and may include a play structure. Consideration should be given to summer uses (such as basketball) and winter construction of an ice rink.

C. The size and location of “tot lots” and neighbourhood parks will ensure that adjacent residences are not disturbed.

D. New park spaces can be integrated with school sites or located on lots with other community or institutional uses.

The International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) is a Canadian non-profit organization that advocates for resilient and inclusive trails across Canada. The IMBA places emphasis on the significance of proper trail construction and provides the following set of guidelines:

1. The Half Rule: A trail’s grade shouldn’t exceed half the grade of the side slope.

2. The 10-Percent Average Guideline: Average grade should stay under 10 percent (with grade reversals).

3. Maximum Sustainable Grade: Maximum grade should be 15 percent (except for natural or built rock structures).

4. Grade Reversals: Build on the contour and use frequent grade reversals – surf the hillside.

5. Outslope: sloping the trail surface away from the center, typically towards the outer edge of the trail.

• Develop multiple primary loop trails of varying distances that connect and celebrate critical destinations around the city.

• Provide different access opportunities within the loop network to help reduce conflicts, increase capacity, and assist new visitors with making proper decisions.

• Use bench-cut construction, which involves removing soil and rock from the hillside, creating a level or gently sloping trail surface.

• For reroutes, reclaim old trail thoroughly – the visual corridor as well as the trail tread.

• In the case of highly technical trails with occasional steep grades surpassing 15 percent, it is recommended to incorporate natural rock elements, rock armoring, or other rock features.

• Propose regrouping points throughout the trail as an effective strategy to discourage users from deviating from designated areas and potentially causing damage to sensitive sites or plant life.

• Minimize fragmentation’s impact by locating the densest sections of trail near developed areas or trailheads.

IMBA, the International Mountain Bicycling Association, provides guidance and recommendations on trail design standards through its Trail Solutions program. IMBA is a leading organization focused on promoting sustainable mountain biking and trail development. While IMBA's specific guidelines may evolve over time, the organization emphasizes the following principles in trail design:

Sustainability: IMBA encourages the creation of sustainable trails that minimize erosion, protect natural resources, and require less long-term maintenance. Designing trails that work with the natural topography and properly managing water drainage are essential considerations.

1. User Experience: IMBA emphasizes the importance of providing an enjoyable and engaging experience for all trail users. This includes incorporating features like berms, rollers, and jumps for mountain biking trails, while ensuring proper signage, wayfinding, and clear sightlines to enhance safety and navigation.

2. Accessibility and Inclusivity: IMBA promotes designing trails to be inclusive and accessible for users of diverse abilities, including individuals with disabilities. This involves considering trail grades, widths, and surfaces that accommodate a wide range of users, including those using adaptive equipment.

3. Natural Resource Protection: IMBA emphasizes the need to protect and preserve the natural environment and ecosystem surrounding trails. Designing trails to avoid sensitive areas, minimizing tree removal, and rehabilitating disturbed areas are key aspects of their recommendations.

4. Multi-Use Considerations: IMBA recognizes the importance of multi-use trails that accommodate a variety of users, including hikers, runners, equestrians, and mountain bikers. Designing trails with appropriate widths, signage, and features that minimize conflicts and promote courteous trail sharing is a central focus.

5. Collaboration and Partnerships: IMBA emphasizes the importance of collaboration with land managers, landowners, local communities, and user groups when planning and designing trails. Engaging stakeholders early in the process helps ensure that trails meet the needs of all users and align with broader land management goals.

It's worth noting that IMBA's specific trail design guidelines and recommendations may be subject to updates and modifications. For the most current and detailed information on IMBA's trail design standards, it's recommended to visit their official website or consult their publications, such as the "Trail Solutions: IMBA's Guide to Building Sweet Singletrack" book.

The plan proposes 3 main trail types. The trails are classified based on their significance in terms of potential connectivity, potential usage and the type of use. The following are the trail types.

These priority trails connect neighbourhoods and the City Core to significant destinations. They are the highest priority trails for development. Unless indicated these trails are all season use. On these types of trails snowmobile crossings of roadways are formalized. Subclassification of these trails include Winter-use Primary Urban Trail and Summer-use Primary Urban Trail. The Winter-use Primary Urban Trail is intended only for winter use , and does not include adding gravel during construction. The Summer-use Primary Urban Trail does not permit snowmobiles.

These trails connect destinations with where people live, work and play. They are of lower priority than Primary Urban trails, have less traffic, and are often the result of desire lines historically created in the City. They are smaller in scale and are all season multimodal use. Road crossing may or may not be identified. Subclassification of these trails include the Summer-use Urban Footpath which does not permit snowmobiles.

This trail type is used primarily for recreation purposes. This could include all types of use. Because they are located in more open landscapes the speed of travel may be higher and therefore the width needs to increase. Because they are longer and more remote, additional facilities along the trail are required, such as seating, interpretive information, and shelters. Sub classification of these trails include the Summer-use Recreation Trail.

Significant on street (within Road Right of Way) connectors are indicated on the map for communication and long-term planning within other Departments of the City. These facilities fall outside the jurisdiction of Parks. The On Street connectors are critical to creating an interconnected trail network in the City.

When preparing trail design standards, several factors are typically considered to ensure the safe, functional, and enjoyable use of the trails. These factors may vary depending on the type of trail (e.g., pedestrian, cycling, multi-use), the intended use, and the specific location. Here are some common considerations when developing trail design standards:

1. Trail Purpose and Intended Use: The purpose of the trail and the intended user groups play a crucial role in determining design standards. Factors such as whether the trail is for pedestrians, cyclists, or both, and the expected level of use (e.g., recreational, commuting) influence design decisions.

2. Trail Alignment and Layout: The alignment and layout of the trail are important considerations. Factors such as topography, natural features, existing infrastructure, and desired connections to key destinations help determine the optimal trail alignment and layout. Consideration is given to minimizing environmental impact, maximizing safety, and creating an engaging and scenic experience.

3. Trail Width: The appropriate width of the trail is determined based on the anticipated user volume, user types (e.g., pedestrians, cyclists, equestrians), and any required separation between different user groups. Design standards may specify minimum and recommended trail widths to accommodate different modes of travel and ensure safe passing and overtaking opportunities.

4. Trail Surface: The trail surface material is selected based on factors such as expected use, durability, sustainability, maintenance requirements, and environmental considerations. Common trail surface materials include asphalt, concrete, crushed stone, gravel, or natural surfaces, depending on the desired trail experience and the trail's location and purpose.

5. Grade and Slope: The grade and slope of the trail impact its accessibility, user comfort, and safety. Design standards often specify maximum and minimum allowable grades to accommodate users of varying abilities, including individuals with disabilities. Attention is given to ensuring manageable slopes, avoiding excessively steep sections, and incorporating switchbacks or other techniques to manage elevation changes.

6. Trail Crossings and Intersections: Design standards address how the trail interacts with roadways, driveways, other trails, and pedestrian or cycling infrastructure. Consideration is given to safe crossing points, signage, visibility, and appropriate markings to ensure user safety and minimize conflicts.

7. Accessibility: Incorporating accessibility features to ensure trails are usable by individuals with disabilities is an important consideration. Design standards often include guidelines on accessible trail design, including provisions for accessible parking, rest areas, signage, and trail surfaces that meet accessibility requirements.

8. Safety Features: Trail design standards may outline the inclusion of safety features such as barriers, guardrails, warning signs, lighting, and visibility enhancements to promote user safety and minimize potential hazards.

9. Environmental and Ecological Considerations: Trail design standards may include provisions to minimize impacts on the surrounding environment, including natural habitats, water bodies, and sensitive ecosystems. This may involve techniques such as erosion control measures, wildlife crossings, and preserving or restoring vegetation along the trail corridor.

10. Maintenance and Long-Term Sustainability: Design standards consider long-term maintenance needs, including access for maintenance vehicles, drainage features, erosion control measures, and other considerations to ensure the sustainability and longevity of the trail.

These considerations are not exhaustive and may vary based on regional guidelines, local regulations, and specific project requirements. Engaging stakeholders, considering user input, and conducting site assessments are vital steps in developing trail design standards that address the unique needs and characteristics of each trail project.

Trail standards refer to guidelines and criteria used to establish consistent design, construction, and maintenance practices for various types of trails. These standards help ensure that trails are safe, sustainable, and accessible for users. Trail standards can vary depending on the trail type, location, intended use, and governing authority.

Note: Strip Organic Layer to ± 100mm

Note: Strip Organic Layer to ± 100mm

Save organic material

Save organic material

100mm crushed gravel or dirt to fill void

100mm crushed gravel or dirt to fill void

Save organic material

Existing

Trail Purpose and Intended Use:

• Neighbourhood connector.

• Walking, hiking, cycling, snowmobile, x-country skiing (informal).

• Winter-use Primary Urban Trail – Are trails only used in the winter months when there is snow cover.

Trail Alignment and Layout:

• Located in Open Space

• Offset trail a minimum of 3.0m from private property.

• Avoid steep and dangerous terrain.

• Locate trails on previously disturbed areas if possible.

Trail Width:

• 2.0m Width Summer/4.0m Winter

Trail Surface:

• Summer- compacted gravel between small riprap.

• Winter- compacted/groomed natural snow cover.

Grade and Slope:

• Maximum grade 15% (15-20% over short distances).

• 10-Percent Average for segments of the trail.

• Half the grade of the side slope.

Trail Crossings and Intersections:

• Stop and information signs on the trail for all road crossings where trail meets or crosses a road.

• Formalized snowmobile crossing for all trails that cut across roads. Road operations special consideration for snow removal required.

Accessibility:

• Trail material to be less than 15mm.

• Seating at regular intervals.

• Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines recommends a minimum clear width of 36 inches (91 cm) for most trails, with a maximum cross slope of 2%.

• Gravel trails should be designed and maintained to meet these width and slope requirements, allowing individuals using mobility devices to navigate comfortably.

• Gravel should be firmly compacted to provide a stable surface that minimizes unevenness and trip hazards.

• Select gravel size and composition carefully to ensure it remains compacted and does not shift excessively.

• Periodically regrade or replenish gravel as needed to maintain a stable and accessible trail surface.

• Provide accessible resting areas or seating options at regular intervals along the trail, as mentioned in the previous responses.

• Install signage that provides clear directions and information about accessible routes, points of interest, and any potential accessibility barriers along the trail.

• Use universal symbols and easy-to-read text to aid individuals with visual impairments.

Safety Features:

• Install signage that provides clear directions and information about routes, points of interest, and any potential barriers along the trail.

• Provide safety barrier adjacent to slopes greater than 30% or where hazards exist if the user falls from trail.

• Stop and information signs on trail for all road crossings where trail meets or crosses a road.

Environmental and Ecological Considerations:

• Provide signage along trails encouraging users to stay on the trail.

• Provide deterrence of snow mobiles accessing water bodies.

Maintenance and Long-Term Sustainability:

• Regularly maintain the gravel surface to prevent erosion, washouts, or excessive loose gravel accumulation.

• Design standards consider long-term maintenance needs, including access for maintenance vehicles, drainage features, erosion control measures, and other considerations to ensure the sustainability and longevity of the trail.

Trail Purpose and Intended Use:

• Tie-in trails.

• Walking, hiking, cycling, snowmobile.

• Summer-use Urban Footpath.

Trail Alignment and Layout:

• Located in Open Space

• Offset trail a minimum of 3.0m from private property.

• Avoid steep and dangerous terrain.

• Locate trails on previously disturbed areas if possible.

Trail Width:

• 0.9m Width Summer/2.5m Winter

Trail Surface:

• Summer- compacted gravel or dirt.

• Winter- Compacted natural snow cover.

Grade and Slope:

• Maximum grade 15% (15-20% over short distances).

• 10-Percent Average for segments of the trail.

• Half the grade of the side slope.

Trail Crossings and Intersections:

• Stop and information signs on trail for all road crossings where trail meets or crosses a road.

• No formalized snowmobile crossings.

Accessibility:

• Trail material to be less than 15mm.

• Seating at regular intervals.

• Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines recommends a minimum clear width of 36 inches (91 cm) for most trails, with a maximum cross slope of 2%.

• Gravel trails should be designed and maintained to meet these width and slope requirements, allowing individuals using mobility devices to navigate comfortably.

• Gravel should be firmly compacted to provide a stable surface that minimizes unevenness and trip hazards.

• Select gravel size and composition carefully to ensure it remains compacted and does not shift excessively.

• Periodically regrade or replenish gravel as needed to maintain a stable and accessible trail surface.

• Provide accessible resting areas or seating options at regular intervals along the trail, as mentioned in the previous responses.

• Install signage that provides clear directions and information about accessible routes, points of interest, and any potential accessibility barriers along the trail.

• Use universal symbols and easy-to-read text to aid individuals with visual impairments.

Safety Features:

• Install signage that provides clear directions and information about routes, points of interest, and any potential barriers along the trail.

• Provide safety barrier adjacent to slopes greater than 30% or where hazards exist if the user falls from trail.

• Stop and information signs on trail for all road crossings where trail meets or crosses a road.

Environmental and Ecological Considerations:

• Provide signage along trails encouraging users to stay on the trail.

• Provide deterrence of snow mobiles accessing water bodies.

Maintenance and Long-Term Sustainability:

• Regularly maintain the gravel surface to prevent erosion, washouts, or excessive loose gravel accumulation.

• Design standards consider long-term maintenance needs, including access for maintenance vehicles, drainage features, erosion control measures, and other considerations to ensure the sustainability and longevity of the trail.

Trail Purpose and Intended Use:

• Trail for recreation, fitness and sport.

• Walking, hiking, cycling, snowmobile, x-country skiing (informal), snowmobiles

Trail Alignment and Layout:

• Located in Open Space

• Offset trail a minimum of 3.0m from private property.

• Avoid steep and dangerous terrain.

• Locate trails on previously disturbed areas if possible.

Trail Width:

• 1.5 – 2.5m Width Summer/4.0m Winter

Trail Surface:

• Compacted gravel between small riprap.

• Winter- Compacted natural snow cover.

Grade and Slope:

• Maximum grade 15% (15-20% over short distances).

• 10-Percent Average for segments of the trail.

• Half the grade of the side slope.

Trail Crossings and Intersections:

• Stop and information signs on trail for all road crossings where trail meets or crosses a road.

• Formalized snowmobile crossing for all trails that cross roads. Road operations special consideration for snow removal required.

Accessibility:

• Trail material to be less than 15mm.

• Seating at regular intervals.

• Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines recommends a minimum clear width of 36 inches (91 cm) for most trails, with a maximum cross slope of 2%.

• Gravel trails should be designed and maintained to meet these width and slope requirements, allowing individuals using mobility devices to navigate comfortably.

• Gravel should be firmly compacted to provide a stable surface that minimizes unevenness and trip hazards.

• Select gravel size and composition carefully to ensure it remains compacted and does not shift excessively.

• Periodically regrade or replenish gravel as needed to maintain a stable and accessible trail surface.

• Provide accessible resting areas or seating options at regular intervals along the trail, as mentioned in the previous responses.

• Install signage that provides clear directions and information about accessible routes, points of interest, and any potential accessibility barriers along the trail.

• Use universal symbols and easy-to-read text to aid individuals with visual impairments.

Safety Features:

• Install signage that provides clear directions and information about routes, points of interest, and any potential barriers along the trail.

• Provide safety barrier adjacent to slopes greater than 30% or where hazards exist if the user falls from trail.

• Stop and information signs on trail for all road crossings where trail meets or crosses a road.

Environmental and Ecological Considerations:

• Provide signage along trails encouraging users to stay on the trail.

• Provide deterrence of snow mobiles accessing water bodies.

Maintenance and Long-Term Sustainability:

• Regularly maintain the gravel surface to prevent erosion, washouts, or excessive loose gravel accumulation.

• Design standards consider long-term maintenance needs, including access for maintenance vehicles, drainage features, erosion control measures, and other considerations to ensure the sustainability and longevity of the trail.

When a trail is shared between snowmobiles and pedestrians, it is important to consider the safety and accessibility of both user groups. Here are some factors that need to be considered:

1. Trail Design and Separation:

• Create separate designated lanes or sections for pedestrians and snowmobiles, whenever possible, to ensure the safety and comfort of both user groups.

• Physical barriers such as fencing, bollards, or natural buffers can be used to clearly separate the two modes of travel.

• If separate lanes are not feasible, consider establishing designated time slots or specific days when snowmobiles are not allowed to ensure pedestrian safety.

2. Trail Width and Passing Areas:

• Design the trail width to accommodate both pedestrians and snowmobiles safely.

• Ensure there is sufficient width for snowmobiles to pass pedestrians with ample clearance.

• Incorporate wider passing areas or designated pull-off spots where snowmobiles can safely overtake pedestrians.

3. Signage and Communication:

• Install clear signage along the trail indicating the shared use and any specific rules or regulations that apply.

• Use standardized symbols and text to indicate the presence of snowmobiles and to provide instructions for pedestrians and snowmobile operators.

• Provide educational materials and information to promote mutual understanding and respect between the two user groups.

4. Trail Maintenance and Surface Conditions:

• Regularly maintain the trail surface to ensure it is safe and accessible for both snowmobiles and pedestrians.

• Clear snow, ice, fallen branches, or any other obstructions promptly to prevent hazards for all users.

• Monitor and repair any surface irregularities that may pose a risk to both snowmobiles and pedestrians.

5. Speed and Behavior:

• Encourage responsible behavior from both snowmobile operators and pedestrians.

• Clearly communicate speed limits and any specific rules related to trail use.

• Promote awareness of trail etiquette, including yielding and passing protocols, to ensure safety and harmony between the two user groups.

6. Consider Local Regulations:

• Consult with local authorities, trail management organizations, or snowmobile clubs to understand any specific regulations or guidelines for shared use trails in your area.

• Compliance with local regulations is essential to ensure the safety and legality of trail use.

By considering these factors and promoting cooperation and respect between snowmobile operators and pedestrians, you can help create a shared-use trail that provides a safe and enjoyable experience for all users.

Design standards for snowmobile trails can vary based on location, terrain, and local regulations. However, here are some typical considerations and design standards for snowmobile trails:

1. Trail Width:

• Snowmobile trails typically have a minimum width of 2.4 to 3m to accommodate the width of snowmobiles and allow for safe passing.

• 3.7 to 4.9m wider sections or passing lanes should be incorporated where appropriate.

2. Trail Clearances:

• Maintain adequate vertical and horizontal clearances to ensure safety and prevent collisions with overhanging branches, utility lines, or other obstructions.

• Adequate clearance height should be provided to accommodate snowmobiles of varying sizes.

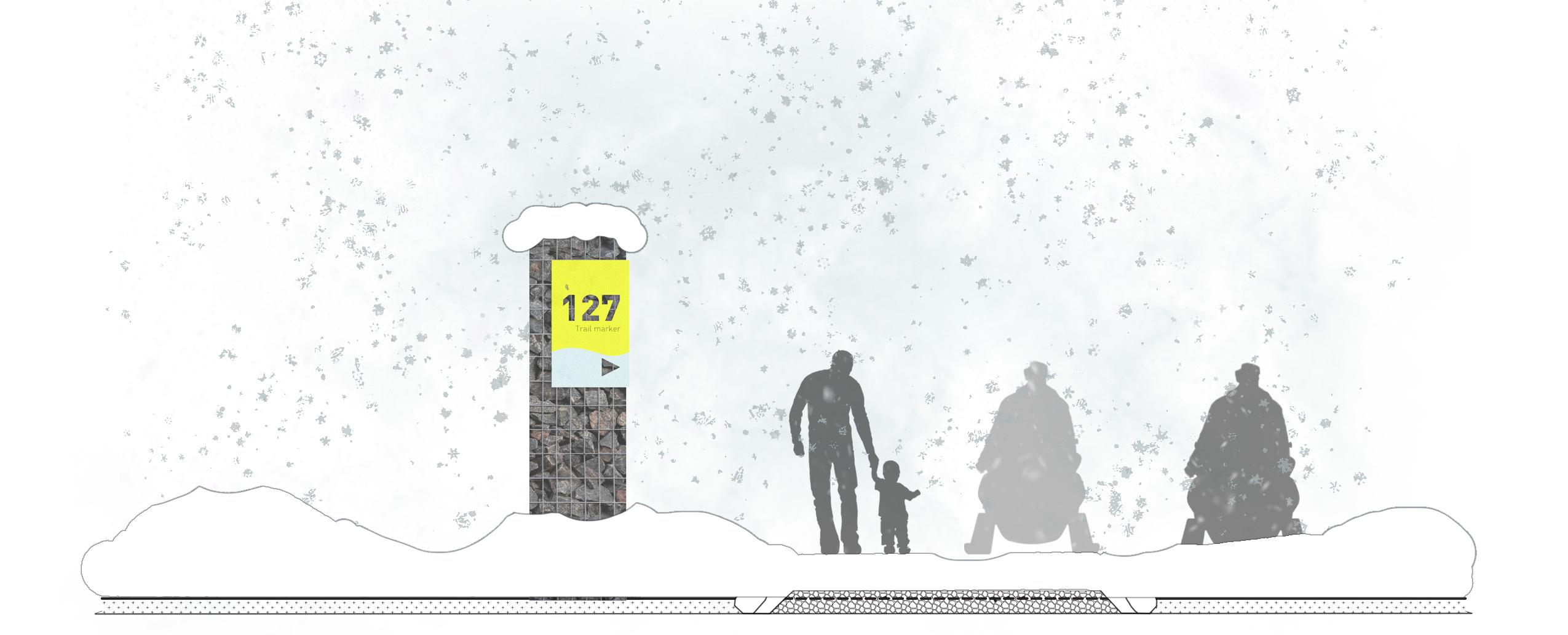

3. Trail Marking:

• Clear and consistent trail markers should be placed along the trail to guide snowmobile operators and minimize the risk of getting lost.

• Use standardized trail markers and signage that are visible in winter conditions, such as reflective markers or brightly colored signs.

4. Trail Signage:

• Install signage at trailheads, intersections, and critical points along the trail to provide directions, warnings, and important information for snowmobile operators.

• Signs should be clear, durable, and visible in snowy conditions.

• Include safety reminders, speed limits, and any specific regulations or guidelines.

5. Trail Surface:

• The trail surface should be well-compacted and groomed regularly to provide a smooth riding experience.

• Snowmobile trails may require regular maintenance, including grading, snow packing, and removing hazards such as wind blown debris.

6. Safety Considerations:

• Identify and address potential safety hazards along the trail, such as steep slopes, water crossings, or areas prone to drifting snow.

• Install appropriate safety measures, such as guardrails, signs, or barriers, to mitigate risks.

7. Trail Connections:

• Ensure proper connectivity between snowmobile trails, including intersections with other trail systems or access points to amenities, fuel stations, or parking areas.

• Clearly mark trail connections and provide signage to guide snowmobile operators.

8. Environmental Considerations:

• Minimize environmental impact by designing trails to avoid sensitive areas such as frozen water bodies, wetlands or wildlife habitats.

• Implement erosion control measures and consider the use of designated bridges or boardwalks for crossing sensitive areas.

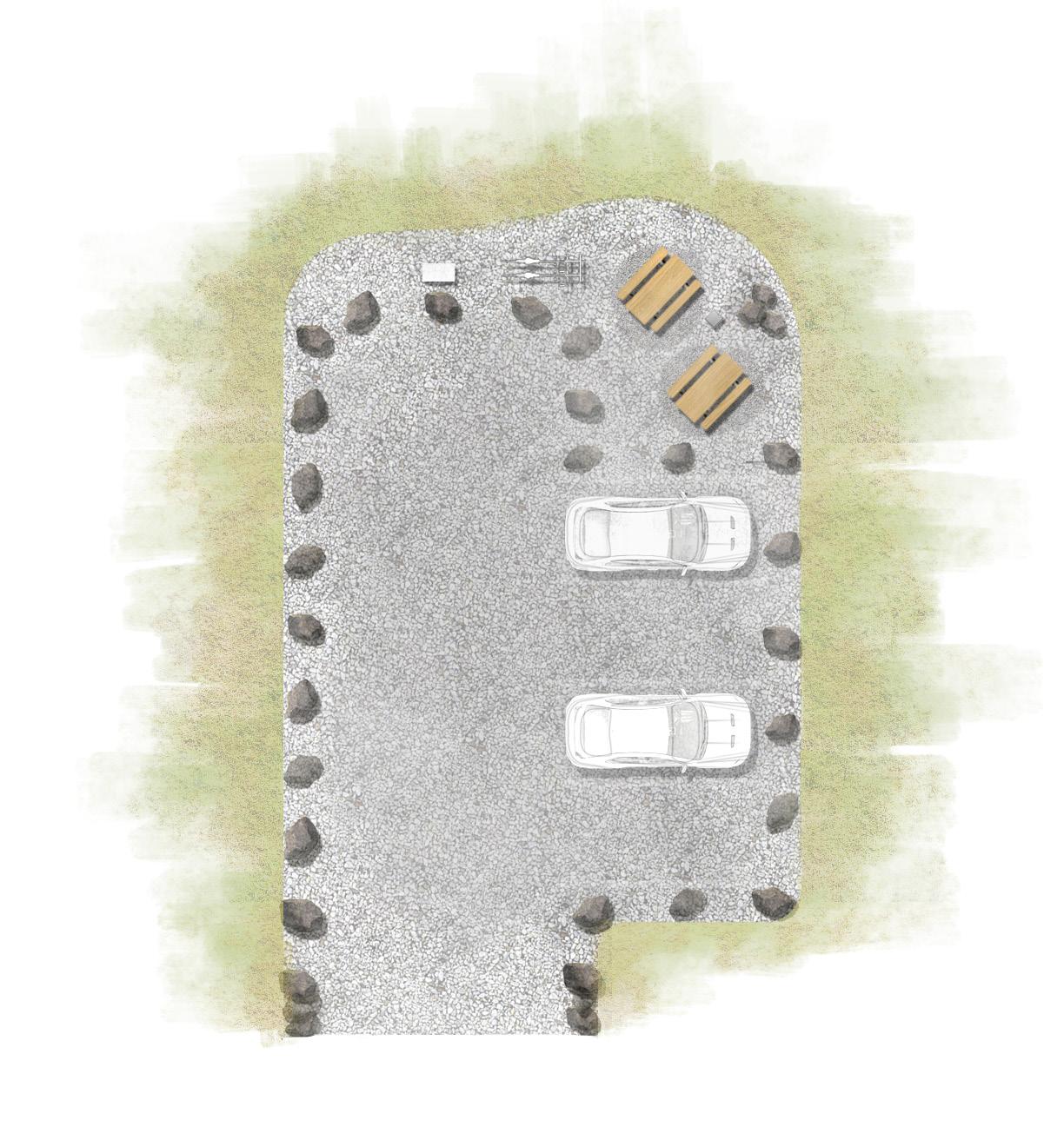

Staging areas, also known as trailheads or trailhead facilities, play a crucial role in the overall functionality and enjoyment of trail systems. These areas serve as the entry points or starting points for outdoor recreational trails, whether for hiking, biking, snowmobiling, or other activities. The value of having staging areas in trail systems includes:

1. Access and Convenience: Staging areas provide a convenient and easily accessible starting point for trail users. They often include parking areas, restrooms, information kiosks, and other amenities, making it easier for people to access and enjoy the trails.

2. Orientation and Information: Trailheads typically feature trail maps, signage, and information boards that help users understand the trail system, its routes, and any relevant regulations or safety information. This enhances the user experience and safety.

3. Safety: Staging areas can serve as critical points for safety and emergency services. They offer a central location where emergency personnel can respond quickly in case of accidents or medical issues on the trail.

4. Organization: Having designated staging areas helps organize trail use and prevents random parking along roadsides or in environmentally sensitive areas, reducing the potential for habitat disruption and conflicts with other land uses.

5. Trail Maintenance and Management: Staging areas are often hubs for trail maintenance activities. Maintenance crews can store equipment, coordinate efforts, and launch work from these central locations. This helps keep the trails in good condition and ensures they are safe for users.

6. Environmental Protection: By concentrating user activity and parking in designated staging areas, the impact on the surrounding environment is minimized. This approach can help protect sensitive ecosystems, reduce soil erosion, and prevent damage to natural resources.

7. Community and Economic Benefits: Staging areas can provide economic benefits to nearby communities by attracting visitors and outdoor enthusiasts. Local businesses, such as restaurants, shops, and lodging, may benefit from increased traffic.

8. Community Gathering Spaces: In addition to their practical functions, staging areas can serve as gathering places for the local community. They may host events, educational programs, and community activities related to outdoor recreation.

9. Preservation of Cultural and Historical Sites: Some staging areas are located near cultural or historical sites, providing opportunities for interpretation, education, and preservation of cultural heritage. These areas can serve as gateways to culturally significant trail systems.

10. Trail System Connectivity: Staging areas can be strategically located to connect multiple trails, allowing trail users to access diverse trail experiences from a single point. This promotes exploration and engagement with a broader range of landscapes and ecosystems.

Overall, staging areas are fundamental components of trail systems, contributing to the accessibility, safety, organization, and enjoyment of outdoor recreational activities. They serve as gateways to natural landscapes and play a critical role in the responsible and sustainable management of trails and their surrounding environments.

Development standards for trailheads can vary significantly based on factors such as the specific location, type of trail, the managing agency, and the intended user experience. However, there are some common development standards and features that are typically considered when planning and designing trailheads. These standards are intended to ensure safety, accessibility, and a positive user experience. Here are some typical development standards for trailheads:

1. Parking Facilities: Adequate parking areas are essential to accommodate trail users. The number of parking spaces should be based on the expected trail usage. Spaces should be well-marked and designed to minimize environmental impact. Minimum parking allocation is 6 vehicles.