EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

ClaireTiunn,PO‘24

CarolinaGutiérrez-Tunstad,SC‘24

ASSISTANT EDITOR

AlexandraRunnels,PO‘25

ART EDITOR

VictoriaBrooks,PO‘24

RUSSIAN DEPARTMENT FACULTY

LarissaRudova

KonstantineKlioutchkine

LianaBattsaligova

LANGUAGE RESIDENT

XeniyaAmelina

EVENTS ORGANIZER

MiriamAkhmetshin,SC‘26

ClaireTiunn(Chang),PO‘24

CarolinaGutiérrez-Tunstad,SC‘24

VictoriaBrooks,PO‘24

R.M.Corbin,CGU‘24

AlexandraRunnels,PO‘25

MadelineDornfeld,CMC‘25

BiancaMcNeely,PO‘25

Elizaveta(Lisa)Gorelik,CMC‘25

AnaCwietniewicz,PO‘25

NatalieOwen,SC‘25

MiriamAkhmetshin,SC‘26

ColinElias,PO‘26

DearstudentsandfacultyoftheRussianprogram,

Bythetimethisissueisinyourhands,itwouldhavebeen623dayssincethelaunchoftheRussianinvasion ofUkraine.Foraslongasourcommunitycontinuestobeimpactedbythebrutal,ongoingwar,wewill continuetoholdspaceinourheartsandmindsforthoseinClaremontwhoareimpacted.Weare continuouslystrivingtomaketheRussianProgramawelcomingplaceforall,andaplaceforfurthering interculturalunderstanding,cooperation,andfriendship.Ithasbeenheartwarmingtowitnessthe communitybuiltthroughtheRussianPrograminthelastseveralyears;Russianteatrivia,culturaltripsto concertsofEasternEuropeanartists,andouraward-winninglanguagetablejustprovetheblossoming communitythatwillcontinuetobestrong.

We,theVestnikteam,continuetopublishthismagazineinordertofurtherbothpersonalandacademic interestsinRussiaandEasternEuropethataresharedintheRussianProgramcommunityandbeyond.The regionisofimmenseculturalandpoliticalimportancetoday.Thissemester,ourcontributorshaveoutdone themselves,coveringabroadrangeoftopics:Tolstoy(R.M.),LevYashin(Elizaveta),theNagorno-Karabakh conflict,Serbianbasketball(Bianca),Kosovo(Ana),areviewofZvizdan(Natalie),BrightonBeach(Colin),a summerspentinSt.Petersburg,the dombra(Alexandra),andQazaqcandies(Carolina).Wealsohavean interviewwithFrenchprofessorZvezdanaOstojic(Claire),aswellassomefuncrosswords(Natalieand Victoria)!

VestnikwouldnotbepossiblewithoutthehelpandsupportofthefacultyoftheRussiandepartment: ProfessorLarissaRudova,ourfearlessleader&сказкиaficionado;ДядяКостя,oursourceforallthings regardingRussianpopculture;andProfessorLianaBattsaligova,residentRussianavant-gardeexpert Youall loomlargeinourheartsandourminds Thankyouforallyoudoforus Wealsowouldliketothankand congratulateournewLanguageResident,Xeniya,onherfirstsemester!Yourenthusiasmandjoyhave broughtsomuchtothedepartment.Thissemester’sVestnikwouldalsonotbepossiblewithoutthehelpof ourassistanteditor,AlexandraRunnels,andourdesigneditor,VictoriaBrooks.Wealsosendabigthankyou toMiriamAkhmetshin,oureventsorganizerthissemester:youknowhowtomakeapartyhappen,andwe loveyouforit.

WehopethisissueofVestniksparksconversationandthoughtwithinourClaremontcommunity.Wehope thatVestnikandtheRussianprogramcontinuetobeawelcoming,resilientcommunity,andwesenda heartythankyoutoallofourcontributorsfortheirtimeandeffort.Withoutfurtherado,pleaseenjoythis semester’sVestnik!

Fromyoureditors-in-chief, ClaireTiunn(Chang),Pomona‘24,&CarolinaGutiérrez-Tunstad,Scripps‘24

“The example of a syllogism he had studied– Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal– had seemed to him all his life to be correct only in relation to Caius, but by no means to himself… Was it Caius who had kissed his mother’s hand like that, and was it for Caius that the silk folds of his mother’s dress had rustled like that?... Was it Caius who had been in love like that?”

Writers are often identified by the places to where they take us: either away from home or deeper into ourselves. Lev Tolstoy managed to do both.

In describing Tolstoy, the Russian literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky coined the term “ostranenie” (“estrangement”) to describe the way in which Tolstoy’s writings remind us of our lives and our world by making those things that we take for granted– a walk in the woods, the taste of tea, the staccato drumroll of a firing line–appear to us as if for the very first time For Shklovsky, Tolstoy’s estrangement reawakens us to life itself and thus reminds us of its meaning It’s a peculiar and difficult magic There are moments at which it is overtly clear, particularly in the subjectivity of animals, like the evergiving horse in Kholstomer or the sudden dive into the mind of Laska, a hunting dog, in Anna Karenina

I won’t, here and now, attempt to deconstruct or explain the manner by which Tolstoy estranges our world and thus enriches it. Thousands of pages have been and will continue to be written in such pursuit. The fact of the matter is that clinical or theoretical deconstruction of Tolstoy’s methods would entirely deflate the experience of his literature.

Works like War and Peace and The Death of Ivan Ilyich, for all their high-flying contemplation, are matters of the heart: souls writ small. One can only apprehend their interior life through a suspension of assumption and intellect. Was it intellect that drove Vasili Andreyevich to shield his servant from the cold in Master and Man? Was it intellect that Anna Karenina experienced as those welcoming candles rose up behind her eyes?

It is precisely such a suspension of certainty and intellection- a willingness to proceed with pure childlike experience rather than any presumption of knowledge–which positions Tolstoy as imminently important here and now in 2023 Given our place in this present world of information and partisan conviction, a great many of us can benefit from being reminded of what this life really is: a realm through which our souls dance, hand-in-hand, on the delicate pads of our words

Which means that something else is true: anyone can read Tolstoy. Do not let the eight-pound tomes on your shelf scare you. You’re already equipped with everything you need to “get” Tolstoy: you are here in this life: a soul atwirl. Ты полюбишь; ты поймешь.

“Вот революция

Here’s a revolution in soccer: the goalkeeper exits the goal and in this new strange role walks like an attacker.”

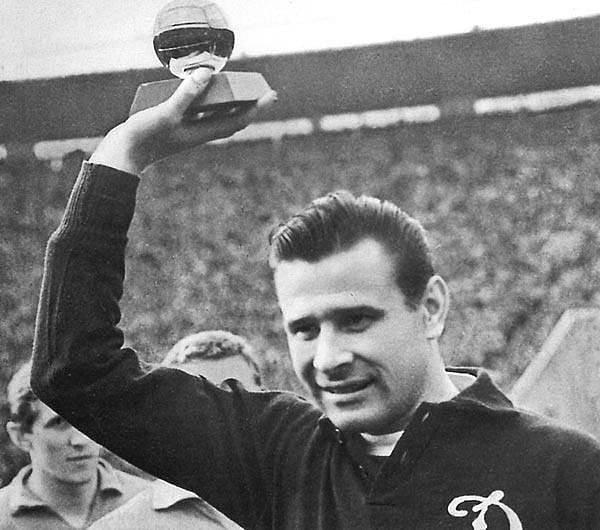

-Evgeney YevtushenkoSix foot two, a flat cap, head to toe in black, with a Dynamo Moscow pin - Lev Yashin, also known as “The Black Spider.” Born in Moscow in 1929, Lev Yashin is still widely recognised as the best goalkeeper in the history of soccer. Not only because he forever changed the course of the game, specifically the goalkeeper position, but also because of his impeccable sportsmanship, unfaltering bravery and incredible life story

When World War Two began in the Soviet Union, Yashin was only 12 years old, and he was sent to work in an arms factory to aid the war effort In his early career, Yashin not only played football, but he was also an accomplished goalkeeper in hockey, helping the Dynamo team win the Soviet cup in 1953 After the war ended, Yashin suffered from a nervous breakdown and nearly quit all sports Yet he continued his soccer career with Dynamo up until 1970

Before Yashin, the goalkeeper remained in the goal for the whole game, and the position was often overlooked. He was the first ever goalkeeper to walk out of the penalty area and defend the goal, as well as shouting orders at his teammates, a soccer tactic that we now take for granted. Back then, his teammates and coaches thought that Yashin’s play was uncanny, and encouraged him to stop trying to deviate from how the game was meant to be played But thanks to Yashin, we now have the riveting game of soccer that we all know and love today

Over his 20 year career, Yashin saved 151 penalties, a record that is still yet to be broken, and kept over 270 clean sheets. He also remains the only goalkeeper to ever receive the prestigious Ballon d’Or award for player of the year in 1963. To score a goal past Yashin was a victory in and of itself, and he received praise and acknowledgement as the best goalkeeper to ever set foot on the field from the likes of the Brazilian soccer legend Pelé Although multiple clubs from the West attempted to poach Yashin, offering him million dollar deals, his loyalties lay with Dynamo Moscow, the only club that he ever played for Yashin passed away at the age of 60 in 1990 due to stomach cancer However, years before his death, both of his legs were amputated due to thrombophlebitis that he contracted because of his smoking habit While the West had already developed titanium prosthetics, Yashin was given prosthetics made out of wood, since the USSR did not have access to this newer type of prosthetic In his final year of life, Yashin was awarded the “Hero of Labour” award, which Gorbachev himself was meant to present to him at his Moscow apartment which he did not step foot out of in his last years. However, Gorbachev never came to Yashin’s home, and instead sent a deputy to present the award to him. Yashin’s first and only wife, Valentina, lived in that same apartment until her death in 2022

Today, Dynamo’s VTB arena which hosted the 2018 world cup is named the “Lev Yashin Stadium,” and Yashin

remains both a sports and cultural legend around the world Songs, such as Vladimir Vysotsky’s “Вратарь” (“Goalkeeper”) have been dedicated to Yashin, as well as a recent movie based on his life, entitled The Goalie of My Dreams He has also been included in FIFA’s Ultimate Team, and the FIFA Lev Yashin award for the best goalkeeper was established in his honor posthumously.

Lev Yashin was never just a sportsman: he has, and always will be, an image of revolution and resistance, of courtesy and pride, and of perseverance even in the face of doubt and judgment. Thank you, Mr. Yashin, for giving us this game of soccer - you are the goalie of my dreams!

And balls can have tears, roses bloom on goal posts only for a goalkeeper like this!”

This September, in an amazingly quick battle, Azerbaijan seized control of Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian enclave housed within Azerbaijan’s recognized borders, ending a decades long conflict The offensive came days after an agreement to reopen the Lachin Corridor, a small strip of land that serves as a transit route connecting Armenia to NagornoKarabakh. The Azerbaijanis had closed off the corridor last December under the claim that Armenia was using the route to smuggle weapons, a move which effectively blocked food, medical supplies, and other essential items from reaching the inhabitants of the enclave Bread was limited to one loaf per family per day, fuel shortages halted public transport, drinking water went untreated, and the region ran out of critical medical supplies

Critics have used the terms “ethnic cleansing” and “genocide” to describe the use of starvation tactics, combined with military intimidation that has resulted in a mass exodus of ethnic Armenians

September 19th and the disarmament of Armenian separatists has sent more than 100,000 ethnic Armenians across the border to the Republic of Armenia, the UN is reporting. It is safe to say, a humanitarian crisis is underway in the region.

The roots of this ethnic conflict date back hundreds of years. According to the Armenians, who look to ancient texts by Strabo and Plinius the Second, the area has been Armenian since ancient times

The Azeris point to the city of Shusha in the Karabakh khanate, a large political center founded by Panah Ali Khan in the 1750s

In the Soviet Era, shortly after the formation of the USSR, the Bolshevik Caucasus Bureau voted to integrate the Nagorno-Karabakh area into Armenia This decision was promptly overturned by Stalin, who the next day elected to keep Karabakh as a part of Azerbaijan. In 1923, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) was officially created within the borders of Azerbaijan under special status and a high degree of self-rule. At the time, the region was 95% ethnically Armenian.

The situation escalated in 1988, following Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, when the regional legislature passed a resolution declaring its intention to join the Republic of Armenia This act sparked the First Nagorno-Karabakh war with skirmishes breaking out in the mountainous region separating the enclave from Azerbaijan in February Ethnic violence on both sides escalated with Azeris being expelled from Karabakh, and pogroms being held on Armenians living in Baku and Sumgait

Around 30,000 people were killed during the six year war. The war officially ended in May of 1994 with a Russian-brokered ceasefire known as the Bishkek Protocol, which left Nagorno-Karabakh de facto independent, but reliant on close strategic ties with Armenia.

War broke out once again in September 2020 when Azerbaijan launched a massive offensive lasting 44 days. This time they were supplied with Turkish attack drones and weaponry, a strategic advantage which allowed them to recapture much of the territory Historically, Azerbaijan was backed by Turkey,

while Armenia traditionally looked to Russia for protection and support – particularly since the 1915 Armenian Genocide by the Ottoman Empire Russian peacekeepers have had a significant presence in the region since the conclusion of the second war in 2020, and since last month, the future of the Russian peacekeeping mission has been brought into question. Russia’s war in Ukraine has preoccupied much of Moscow’s attention, a fact made obvious by Russia's noticeable lack of involvement in this round of fighting

While this most recent development seems to end a drawn out, frozen conflict, the region is still unstable, and Turkey’s growing influence in the Caucuses is something to pay attention to The hundreds of thousands of now-displaced Armenians is also of concern, with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees launching an urgent appeal for international support just days ago It is still unclear what the fate will be for the Armenians who remained

I’m finally going to answer the question that has been on everyone ’ s minds: why is arguably one of the best players in the NBA from Serbia? The recent domination of the two-time NBA MVP and NBA Champion Nikola Jokić may seem a little random, but his success is from a long line of Balkan players in the NBA that started in the late 80s/early 90s, with the arrival of Croats Toni Kukoč and Dražen Petrović to the Bulls and Nets respectively, and Serbian Vlade Divas to the Lakers. Even so, the Balkans are not the only countries in Europe with tall people, so why aren’t there as many players from the Netherlands or Scandinavia in the NBA? Or from wherever else in Europe where the average height is 5 '11? Ultimately, the state emphasis on sports in communist Yugoslavia led to the region’s success in basketball and other sports, even after the end of the Cold War and breakup of Yugoslavia

Sports and physical education were a priority of the Yugoslavian government after World War II and directly embedded in children’s education The newly established Physical Culture Committee of Yugoslavia saw promoting physical fitness as a way to unify the nation at home and show off to the rest of the world how amazing Yugoslavia and its people were. Later, in 1948, the Basketball Federation of Yugoslavia was founded to govern all levels of basketball. The federation created the highest tier of professional basketball, the First Federal Basketball League, with eight clubs, one for each republic, one for Vojvodina (an autonomous province), and of course one for the army. These clubs flourished, dominating the European Basketball Championships and producing the national players that would win the FIBA Basketball World Cup in 1970, 1978, and 1990 Basketball talent also developed locally with hundreds of basketball clubs being founded during the communist era, and the government

building dozens of basketball arenas across the republics to support the sport In addition to the system supporting basketball development in the Balkans, some coaches and players from the Balkans have also argued that what makes players from the region so good is the untraditional coaching practices The training in the Balkans is more egalitarian with coaches emphasizing drilling the same skills into all players, no matter their player build, and forcing them to become versatile. As a result of this style of play, “ you have guys like Jokic 7-foot-1 doing what they do, because they were all brought up to play the game not by position, but [by] the key fundamentals,” ESPN commentator Fran Fraschilla explained to sports website The Ringer. Ultimately, the combination of the system to develop young talent in the Balkans and unique training philosophy has led to 14 of 450 players being from the Balkans last season A remarkable feat in comparison to other countries and regions that produce fewer NBA players relative to their populations

“The first step to achieving transitional justice is restoring the dignity of the victims” This opening remark set the tone for the 2023 Kosovo International Summer Academy (KSA), a ten-day conference on peacebuilding and diplomacy that I attended this August The programming aimed to introduce participants to the complex situation in Kosovo, a partially-recognized country still grappling with its identity after the war against Serbia in 1999-2000. Throughout the conference, I had the opportunity to visit cultural sites and engage with a variety of speakers, ranging from diplomats to academics, and even two former presidents of Kosovo, to better understand how the country has begun to reconcile with its past and pursue transitional justice.

The week began with a visit to the Humanitarian Law Center in Pristina, home to an exhibit entitled Once Upon a Time Never Again Immediately after entering the exhibit, I encountered a wall of 1,133 names spanning from the floor to the ceiling Each name belonged to a child killed or reported missing during the war against Serbia I then entered a room with a collection of seemingly random objects toys, schoolbooks, clothes, and even a small bike I was drawn immediately to a child-sized set of wool pants with a matching pink hat These clothes belonged to an eight-year-old girl who was killed in her home during the war I soon learned that the girl’s surviving family had donated her clothes, as they were the only belongings of hers that remained Like many of the objects in the room, the surviving family donated these personal belongings to bring awareness to the human cost of the conflict. In sharing their stories with the world, parents and family members can honor the lives of their children, thus pursuing their own form of justice.

Another highlight of the conference was a conversation with Atifete Jahjaga, a woman who made history as the youngest and first female president of Kosovo She shared her experiences with us, including her determined efforts to address the needs of the estimated 20,000 survivors of wartime sexual violence in Kosovo Despite significant resistance from her male-dominated cabinet, President Jahjaga established a National Council for survivors of sexual violence to aid with their rehabilitation and reintegration into society. Her unwavering commitment to restoring the dignity of survivors serves as a concrete example of transitional justice in action.

Throughout the conference, I came to understand that pursuing justice in Kosovo is an ongoing process. Though the country is continually confronted with issues of ethnic tensions, national sovereignty, corruption, and political and economic stability, significant progress has been made since the war ended over two decades ago In participating in the KSA this summer, I’ve developed a deeper understanding of peacebuilding and human rights restoration in post-conflict areas As a young country still grappling with questions of identity and reconciling with the past, Kosovo is an excellent place to study the implementation and effects of transitional justice I strongly encourage those interested in issues of human rights and international diplomacy to consider applying for the 2024 edition of the KSA.

I sat down with Professor Zvezdana Ostojic, a new addition to the Pomona College community A visiting assistant professor in the Romance Languages and Literatures Department specializing in French, Professor Ostojic grew up in Serbia

Claire: Tell me a little about your background and how you got to Pomona College

Zvezdana Ostojic: I first came to the United States in 2016 for my PhD in French at Johns Hopkins University During the pandemic, I moved to Florida and Oklahoma and graduated from my program this February. Now, I am a visiting assistant professor at Pomona College. This is my first time in California and it is definitely a different environment from Serbia.

C: So, what was it like growing up in Serbia?

ZO: It was interesting. I grew up during the 1990s Civil War in Yugoslavia and the 1999 bombings of Serbia In 1999 my mother knew we had to leave so we were living in Bosnia and Herzegovina I vividly recall how bad inflation was in Serbia My parents would receive 5 million dinari from work and we would go to the grocery store to buy just two things that was how bad inflation was

C: What are some of your favorite parts of Serbian culture, and Serbia in general?

ZO: I miss the nightlife in Serbia. You simply cannot beat it! The food is also amazing, such as ćevapi (grilled minced meat) and pljeskavica (ground beef or pork patty). I tried making it a few times but I could not get the taste right. I also miss how walkable Belgrade is. I could go out of my house just to get groceries, meet with my friends, and peruse the farmer’s market Serbia also had a more laid back mentality Serbians chill in coffee shops, smoke cigarettes, and drink $2 Turkish coffees I miss that

C: What do you like about Pomona College?

ZO: I honestly love everything. Students are so motivated, smart, and enthusiastic. Students come to office hours and go the extra mile. I also like the small, close community we have

C: What are your thoughts about the intersection between the Russian Program and the Balkans?

ZO: The Balkans should definitely be considered in the Russian Program I consider Serbia to be heavily influenced by Russian culture Serbian and Russian are Slavic languages, Russian writers are widely read and loved in Serbia, and many of us grew up listening to Russian composers We also have similar socialist and brutalist architecture. I would encourage students of the Russian Program to study Balkans history and culture!

Brighton Beach Sheepshead Bay Manhattan Beach If you live in New York City, these places are synonymous with “the Russians,” at least, they were in my circles Most New Yorkers use a sweeping generalization when referring to former Soviet people - despite the large number of other nationalities that may call Southeast Brooklyn home. The truth is, as incredibly diverse as New York is, it is largely a segregated city - partly due to redlining and exclusionary planning, but partly due to self-selection. In the case of Brighton Beach, former Soviets congregated there, finding a safe haven among people with a similar background First came the Odessan Jews, escaping persecution in the Soviet Union to find safety in an already majority Jewish immigrant neighborhood Then came the higher-class Russians, more educated and more likely to call Manhattan Beach their home And finally the most recent influx of Central Asian and Caucasian immigrants, adding a new culture, but attracted to familiarity of the culture as a whole But the story of Brighton Beach includes much more than the “Little Odessa” title it holds today - as with the story of many neighborhoods in NYC, it is a story of the opposing forces of inclusion and exclusion, and the weird and

wonderful places created as a result of such conflict I attended middle school in the adjacent neighborhood of Coney Island, which, due to its proximity to Brighton Beach, also has a large Soviet influence Every morning, on my walk to school, I would pass a billboard of Yuriy Prakhin, the local personal injury attorney, with “Мы

говорим по-русский” plastered above his name. Under Mr. Prakhin was the “Russian bread store,” New York Bread Inc., selling freshly-baked bread and emitting a much welcomed odor among the multitude of auto body shops and construction that occurred on Neptune Avenue. Even before attending a high school that required three years of Russian language, I was living a unique experience for most Americans I made friends with Russians, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Georgians and Ukranians - going to school next to Brighton Beach, it was impossible not to I distinctly remember going with my Tajik friend to Tashkent Supermarket, an expansive buffet of Soviet delicacies This story itself shows the interesting nature of this neighborhood - establishing diversity with Islamic centers, synagogues and orthodox churches; lagman, khachapuri and blini; whilst still joined together through the Russian language and a shared remembrance of Soviet life.

This summer, I returned to Brighton Beach with Miriam Akhmetshin (SC ‘26). I had met her several hours earlier in my home borough of Staten Island, and we had gone through the day speaking almost entirely in Russian. I hoped this would help me to order our eventual meal at Euroasia Cafe, but in this small, cramped Uzbek restaurant, where we sat at a table with another family, I was feeling the pressure. I think I got off the words я буду before Miriam took over and ordered a delicious meal of манты, плов, шашлык и компот I was grateful to have finally returned to Brighton Beach after a year at Pomona College, and feel I gained a greater appreciation, coming back with more knowledge of the Russian language under my belt

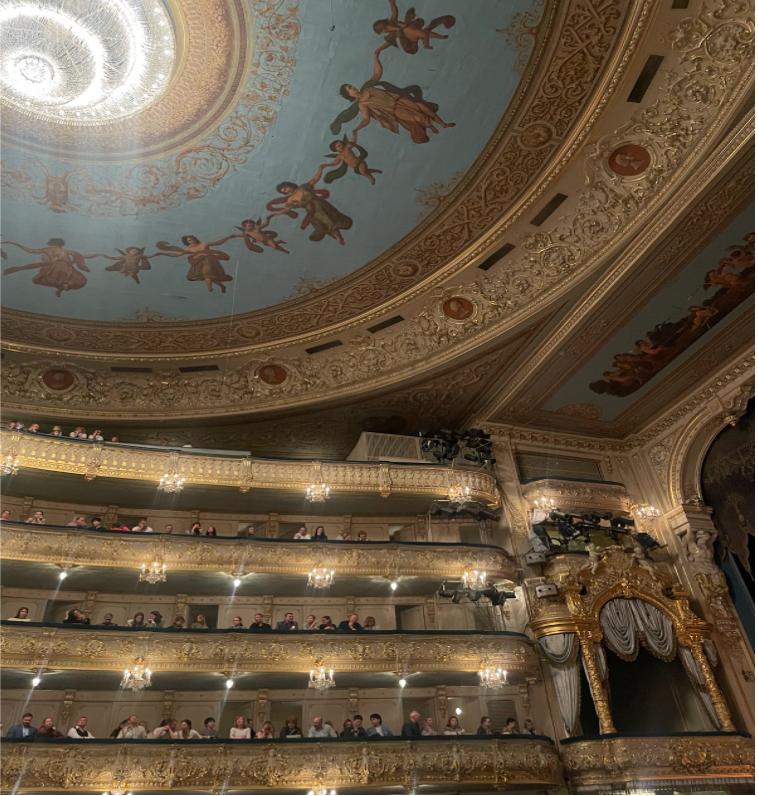

This past summer, I spent three weeks in the northwestern Russian city of Saint Petersburg. I arrived in early June when the “White Nights” were in full swing Due to St Petersburg’s proximity to the Arctic Circle, the sun never fully sets in the summer: thus earning this time period the moniker of White Nights This is perhaps the best time to visit the city as the city has fully defrosted after their long, cold winters One of the biggest celebrations during this time period is Алые паруса It is a celebration of the graduating class attended by tens of thousands of people Алые паруса happens in a few major cities, but St Petersburg has the largest celebration Additionally, St Petersburg is a city of rivers and canals, and they become a big part of the summer nightlife as well. People gather to see the opening of the bridges on the Neva River around 1 am. As the Neva River flows into the Gulf of Finland and the Baltic Sea, many cargo ships rely on the route during the summer, when the river isn’t frozen. The bridges stay open until around 5 am with a 20 minute period around 3 am when they briefly close to let traffic cross to the other side Thus, residents of Petrogradsky Island and Vasilyevsky Island (including our very own Sasha Bystrova) must time their commute in order to not get stuck on the other side of the city

During my time, I explored all of the cultural activities the city has to offer This summer, I went to Swan Lake at the famous Mariinsky theater In past years, I have also enjoyed seeing operas and orchestra performances at the theater. In addition, the city is famous for its world-class museums, including the Hermitage and the Russian Museum.

I explored both of those collections in addition to smaller contemporary museums. Former Russian Language Resident Sasha Bystrova and I enjoyed a visit to the ROSPHOTO Museum as she prepared to leave to study photography in Germany I also attended the 1703 Art Fair, where I was able to see works from numerous galleries While in St Petersburg, I interned at an art auction house I wrote artist biographies for up-andcoming contemporary artists and assisted the director in choosing works for the auction Thus, I was lucky enough to interact with many people active in the art world and discuss current trends

Of course, this wouldn’t be a discussion about culture without mentioning the delicious food I ate. The city has many incredible chefs serving up Russian cuisine with a modern twist. One stand out restaurant is Harvest, on Petrogradsky Island. Half of its menu is vegetarian, with dishes including fennel crudo, broccoli pate, and cauliflower pie with morel mushrooms. I firmly believe that St Petersburg has the best Italian cuisine outside of Italy, so I cannot begin to count how many bowls of homemade pasta I ate during my trip Finally, no trip to Russia is complete without eating copious amounts of Georgian and Uzbek food I had the most wonderful time, and I am excited to visit again this winter!

The Mariinsky Theater

Feeding the city’s many stray cats

The Mariinsky Theater

Feeding the city’s many stray cats

10pm in St. Petersburg

Me and my best friend, Karl Marx, outside of Harvest Restaurant

Me and my best friend, Karl Marx, outside of Harvest Restaurant

Devastating, quieting, and beautiful, Zvizdan, or The High Sun, is a 2015 film by Croatian director Dalibor Matanić. Starring Tihana Lazović and Goran Marković, and taking place over the course of three decades, Matanić unfurls three distinct yet related stories – one in 1991, the second in 2001, and the third in 2011 Despite not receiving a nomination, the film was selected as the Croatian entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 88th Academy Awards

In 1991, Lazović plays Jelena, a lively young woman in love with Ivan (Marković), a good-natured musician Jelena is Serbian, while Ivan is Croatian; given that the year is 1991, the secrecy of their love is necessitated by growing animosity between their two villages, and as prewar inter-ethnic tensions grow, it becomes more and more dangerous for the two of them to be seen together. Nature, in particular a freshwater lake between the villages, unifies them: through swimming in the lake, the two are able to escape briefly to another world, where military trucks and gunmen at checkpoints are out of sight There is an innocence and hope to their love –tensions haven’t broken yet, and their hearts are full of each other By the end of this first story, tensions have spilled over, and things are forever changed

Come 2001, Lazović plays Nataša, a Serbian woman of similar age to Jelena but of no relation, except that she has experienced war in a different phase She and her mother, played by Nives Ivanković, return to their village together to re-inhabit their home, which had been in enemy territory but is now safe

The war has ended, but grief and resentment haunt both mother and daughter, as well as Ante (Marković), the Croatian man they hire to repair their damaged home. Lingering bitterness and the recent pains of war tinge every interaction between Nataša and Ante, and strain the

relationship between Nataša and her mother. Love is complicated by trauma, and the players in this vignette struggle to reconcile their relationships to each other with the traumas of the decade of war they have been through Again, the freshwater lake and natural landscape are important to the relationship between Nataša and Ante, but given the scars of war, their swim is not innocent nor does it provide them much escape from the bruises of war Rather, it is haunted by the death of Nataša’s brother (by Croatians) and Ante’s father (by Serbians) Despite some small peace from the lake, hostility and anguish color them both and cause darkness between the two

Now, the year is 2011, and Luka (Marković) grudgingly returns home with his friend to party. He drags his feet because in the Serbian village neighboring his Croatian town lives Marija (Lazović), a woman he wronged. The air is thick between them, and although a decade has passed and regional wounds are healing, things between Luka and Marija are cold. Luka attends the music festival he has come home for and finds himself in the freshwater lake; he sinks to the bottom, and sees a vision of Marija’s serious gaze There is stillness and remembrance in the water, and in contrast with the pounding warmth of the rave, it sobers Luka As Luka makes and acts on a decision in relation to Marija, Matanić seems to be urging his audience to think about the patience involved both in love and in healing

Ultimately, Matanić’s message is one of hope and selfless love, which can be extrapolated from the two lovers and their relationships during different cycles of suffering and healing to apply to people anywhere healing from pain and conflict I strongly recommend watching Zvizdan whenever you have two hours, a comfortable spot to sit, and a thick pile of tissues.

This summer, I participated in the American Councils Russian Language and Area Studies Program (RLASP) in Almaty, Qazaqstan For seven weeks, I attended classes Monday-Friday, and excursions on the weekends We received intensive instruction in grammar, writing, speaking, vocabulary, pronunciation, and listening, and we also had the opportunity to learn about Qazaq culture and Central Asian politics In our final week, we traveled as a group together to Turkestan and Shymkent We were encouraged to engage with the culture outside of class in our own ways, so I decided to learn the dombra

The dombra is a Qazaq folk instrument and the national instrument of Qazaqstan. It has two strings (traditionally made of sinew, but in modern times, nylon) tuned to G4 and D4. The neck of the instrument has more than 20 frets, giving it a range of about two octaves. Unlike the guitar, dombra players use all five fingers of the left hand (including the thumb) to fret. The instrument is strummed with the thumb and index finger of the right hand making a pinching gesture. Both strings are strummed at once, often with one drone (a repeated, harmonizing note) and one melodic line Between individual instruments, the sound hole (or holes) vary in shape, size, and placement

The dombra can be played on its own, or accompanied by voice In Qazaq, unaccompanied songs are called “ ” (кюй in Russian, or kui in English) Depending on the region, kui may have a specific structure or form One of the most famous composers of kui is Qurmangazy Sagyrbaiuly (in Qazaq, ) During my lessons, I got the opportunity to learn a couple of his kuis, most notably Балбырауын! Hearing this kui as it’s supposed to be played is very impressive, as it includes multiple 16th note runs and incredibly fast strumming, with a tempo of around 160 BPM. I can play this song at closer to half speed!

Having never played a string instrument before, I found that left hand placement was the thing I struggled with the most. It was considered bad technique to have unnatural angles in the fingers and wrists, so I had to keep my wrist straight and my finger joints at 90º angles Additionally, finger placement was difficult, because it greatly affected the quality of sound that came out of the instrument The very tips of the fingertips produced the best sound, and they needed to be placed close to the fret to eliminate buzz

Overall, I had an incredible time learning the dombra, and I felt lucky to be able to immerse myself in the culture of my host country in a unique way!

Hello hello hello, candy enthusiasts of the Russian program I’m back Did you miss me?

After a semester woefully devoid of REES-inspired candy of any kind (there are only so many trips to SuperKing I can stomach), Alex Runnels (PO ‘25) has supplied me with some Qazaq candy for me to try God bless their soul, truly Per usual, I come bearing my standard list of disclaimers: these reviews are purely based on my opinion, which, as always, matters very little. My reviews of the candies can be influenced by a variety of external factors, including (but not limited to): my mood, the weather, my unrefined American palate, my horoscope, whether I remembered to take my meds that day, etc

Мармелад (оранжевый) (Marmelade- orange colored): This candy is a conundrum It is a honeyed fruit flavor? But WHICH fruit? Couldn’t tell you The candy is a sort of pinkishorange, which led me to believe grapefruit or orange? But it’s definitely not? A conundrum I have consulted the ancient texts (also known as the manufacturer’s website) and found the cryptic phrase: со

(fruit and berry flavored) Which fruits and berries those are is left entirely up to the imagination Whoever can definitively tell me which fruit this candy tastes like deserves a Nobel Prize, and, like, $20 At least 3/10

Мармелад (белый) (Marmelade- white): Well at least this one has a definite flavor: pineapple. But like, bad pineapple. My dentist uses piña colada-flavored numbing gel for your gums before injections, and this tasted precisely like it. So not only was it kind of gross, I began having flashbacks to having a giant needle shoved in my mouth. This candy is not for the faint of heart (or at least not for those who also go to my dentist). 2/10.

(Berry brittle in chocolate): ok so it’s a nut brittle in chocolate, but instead of caramel holding the nuts together, it was berry jam? Jelly? Sticky stuff? Either way, YUMMY Throughout my journey in various Slavic candies, I have tasted many a brittle Perhaps too many But this is a previously unseen innovation in the genre. 9/10.

(Apricot brittle in chocolate): Ok, it’s functionally the same as the berry flavored brittle, but this is the first candy I’ve ever had that is apricot flavored. The Qazaqs are making innovations and inroads into new candy flavors for my unrefined American palate. I could eat like 20 of these. 9.7/10.

Со вкусом барбариса (Barberry-flavored): No. Just… no. Apparently barberries, like blackcurrant, are another fruit that is common in Europe and Central Asia but almost nonexistent in America, and I can see why They taste like the cherry flavoring they put in liquid antibiotics, and eating this candy made me clutch my American passport, gaze fondly at my Fahrenheit thermostat, and cry red-white-andblue tears of joy that barberry isn’t a flavor commonly put in American candies. I am now doubling down on my refusal to learn the metric system. 0/10.

Достык (per google translate Friendship): y ’all I’m calling it here This is THE BEST REES CANDY Three semesters of reviews, and I’ve found it Everybody else go home Yummy chocolate around even yummier caramel? No notes 10/10

Маска (Mask): it is chocolate. Inside more chocolate. Good but boring. Would not eat another. 5/10.

Абрикос (Apricot): a hard candy shell with a yummy apricot jelly filling. Closely resembles the Russian “Сибирская ягода, ” which I LOVE Points off for literally the most uncreative naming choice I’ve ever come across 89/10

Лимон (Lemon): same type of candy as Абрикос, but lemon! Yummy. Truly the platonic ideal of a lemon candy. A solid 9/10.

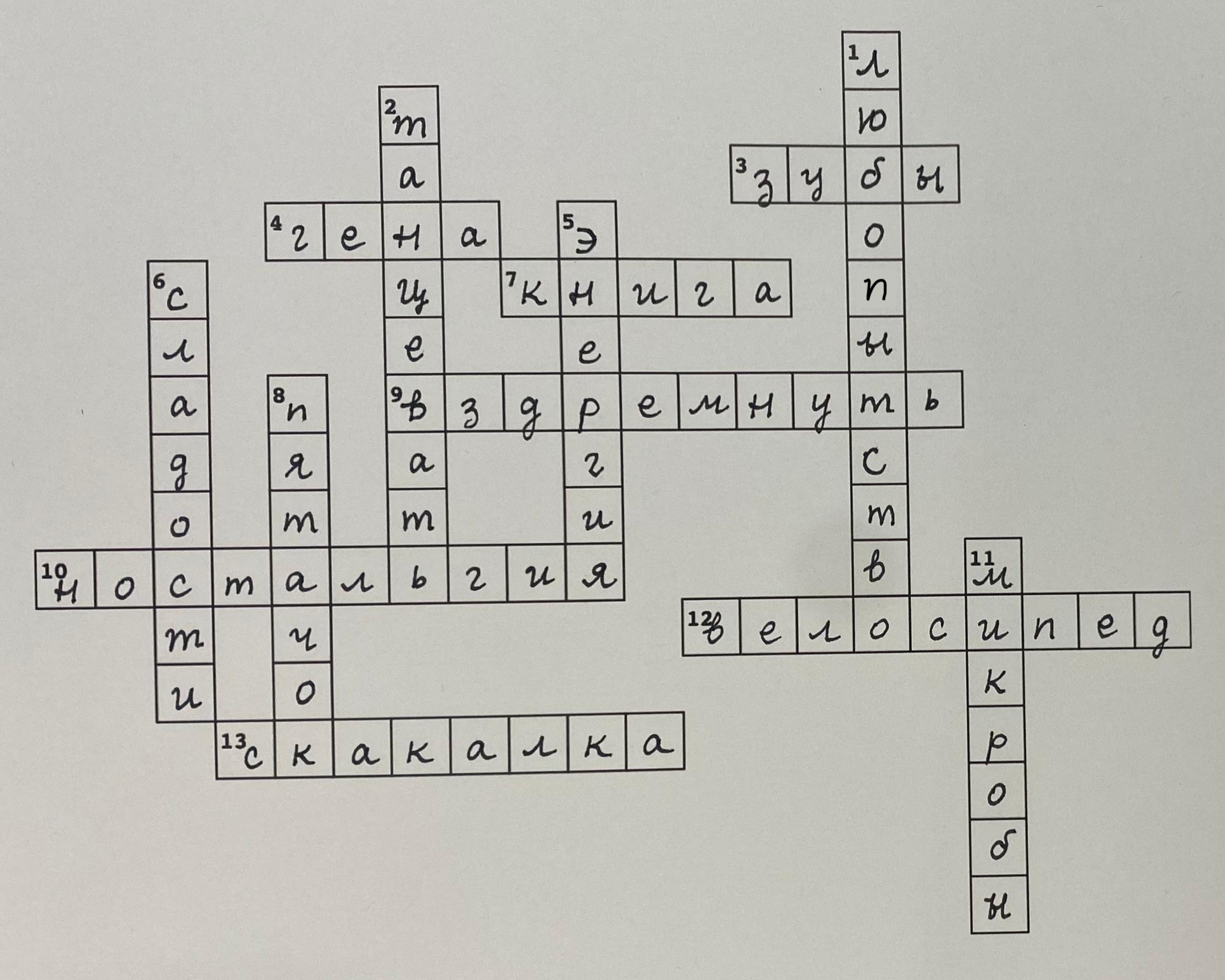

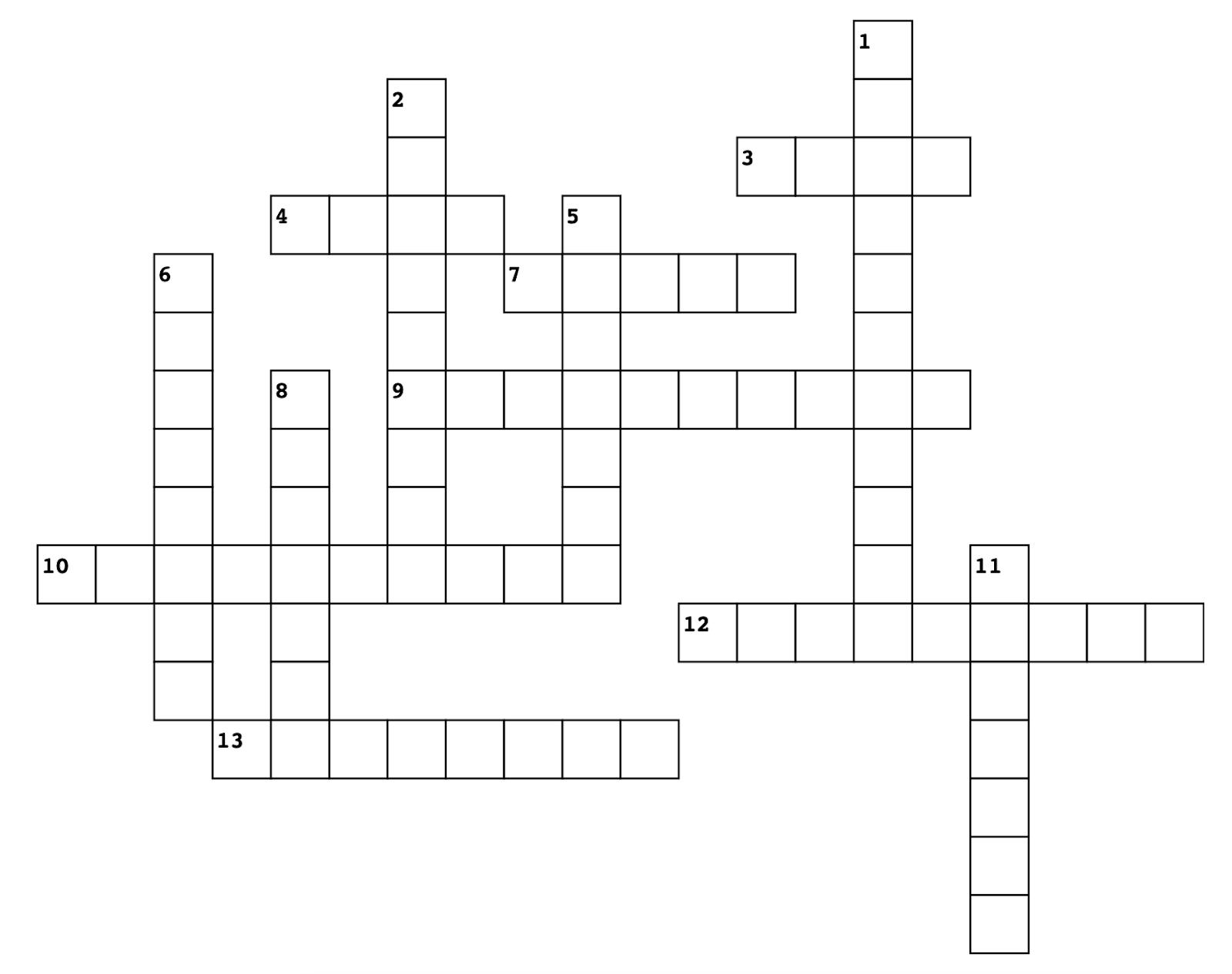

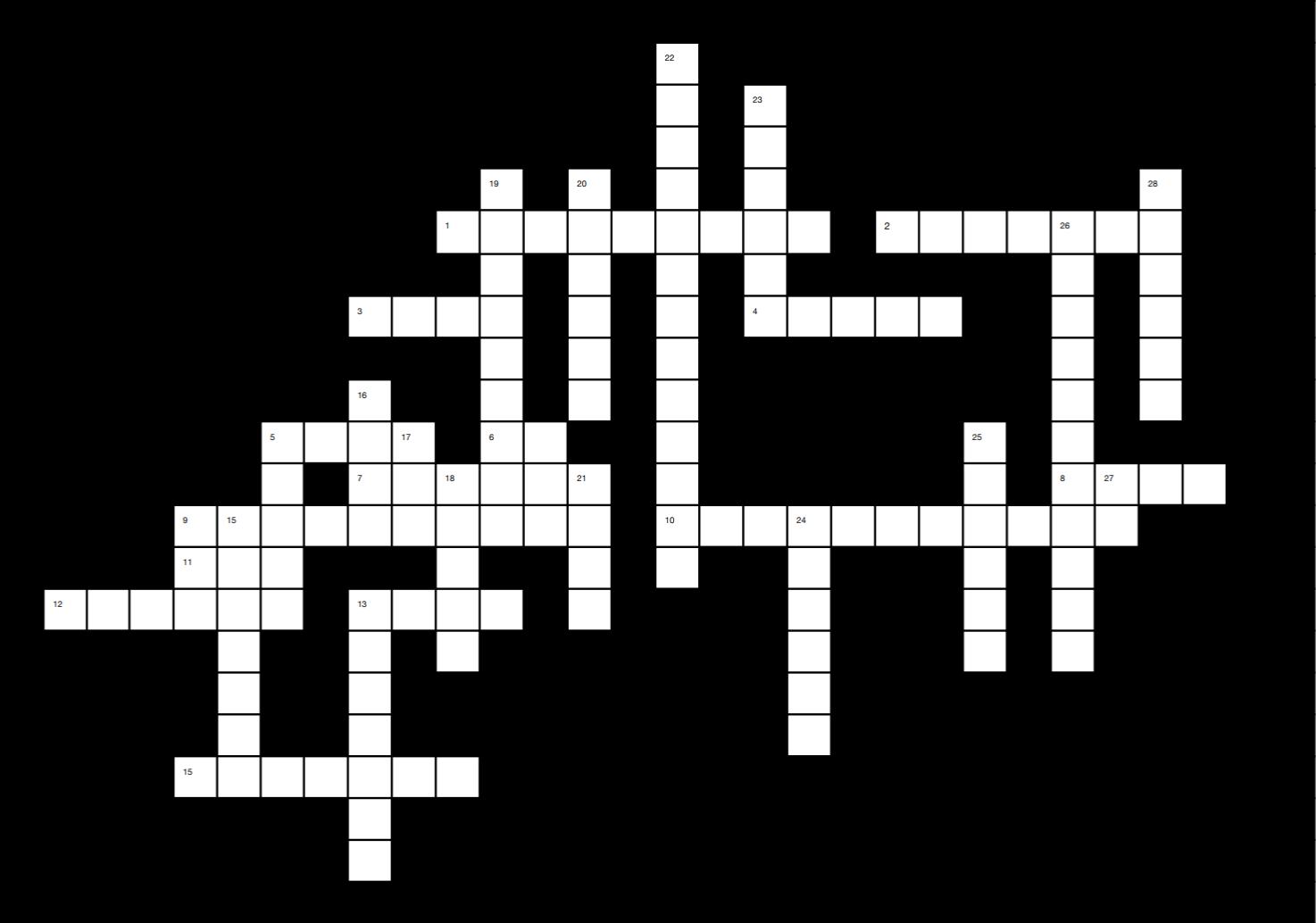

hints are in English;

3. these might hurt if you eat too many сладости

4 a kind cartoon crocodile who is friends with

7. something filled with stories to read

9. something you might do after playing

10. an emotion you feel when thinking about the past

12. you might ride this to school

13 a thick string used for jumping Down

1. the desire to learn or know things

2. a rhythmic activity to do with friends

5. as a child you are filled with this 6 sweet treats

8. small cartoon pig who is close friends with Винни-Пух

11 you learn to wash your hands to not get sick from these

Victoria (Вика) Brooks, Pomona ‘ 24

Russian & Rees Spring 2024 Courses

RUSS2:ElementaryRussian2|MW10:00-11:50am;TTh9:3510:50am|Battsaligova

RUSS44:AdvancedRussian|MW11:00-11:50am;TTh9:35-10:50am |Klioutchkine

RUSS181:ReadingsinModernRussianLiterature|W7:00-9:30 pm|Rudova

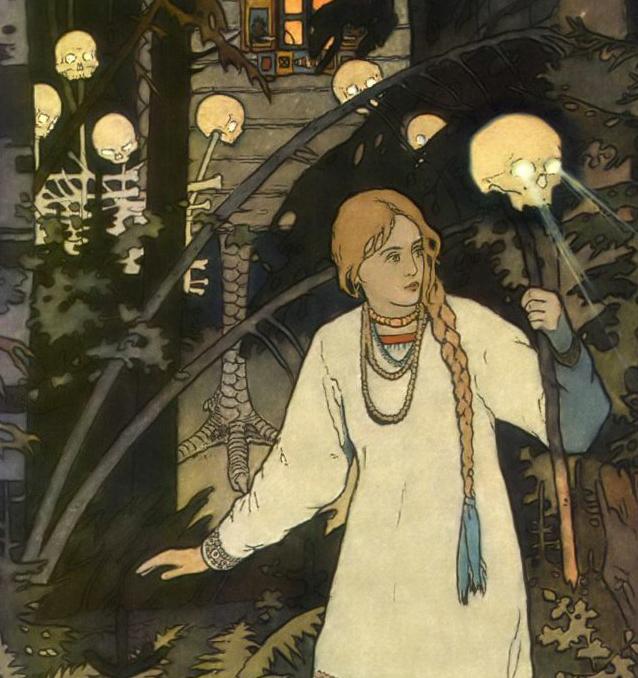

RUST112:PoliticizingMagic:Classic,Russian,andSovietFairy Tales|TTh2:45-4:00pm|Rudova

RUST185:TheNovelsofVladimirNabokov|TTh1:15-2:30pm| Battsaligova

RUSS191:SeniorThesisinRussian/REES Rees-affiliated courses

HIST71PO:ModernEuropesince1789|MW11:00am-12:15pm|Chu

HIST101DPO:ResearchingtheColdWar|TTh1:15-2:30pm| Chu

HIST133CMC:Dostoevsky’sRussia|TTh2:45-4:00pm|Hamburg

SOC095PZ:ContemporaryCentralAsia|W2:45-5:30pm|Junisbai

HIST197CMC:HistoryofUkraine|W2:45-5:30pm|Lauer

This course introduces students to the evolution of Russian literature from the turn of the twentieth century until the present. We will read and analyze works of poetry and short fiction, paying attention to the texts’ cultural and historical context. The values, passions, beliefs, dreams, and fantasies expressed in the texts will help us understand the peculiarity of the Russian national character. We will analyze the narrative strategies and literary techniques that underlie the stylistic originality of such great authors as Chekhov, Bulgakov, Kharms, Mandelstam, Tokareva, Petrushevskaya, Pelevin, Tolstaya, and others.

This course advances reading, writing, and speaking skills in Russian. Assignments will include mini-presentations, short essays, and occasional translations. Emphasis on vocabulary development, stylistics, and oral and written expression in Russian. No final exam.

Prerequisite: Russ 44 or permission of the instructor.

Instructor:L.Rudova SPRING2024 7:00-9:30pm W

This course investigates how fairy tales help us understand the formation of gender and social identities in Western Europe and Russia since prehistoric times to modernity. We will look at the position of women in society and gender hierarchy through folklore. Do fairy tales perpetuate gender stereotypes? Or are they subversive in gender representation? How does modern popular culture reinterpret and recontextualize fairy tales? Why do men in Russian folklore need women to succeed? What role does the myth of divine maternity play in the history of Russian culture? What is the masculine response to this myth in Russia? How do the feminine and the masculine clash with each other and why has the feminine myth endured up to the present? How do Soviet writers rewrite the gender dynamic in new Soviet fairytales? These and other questions directly related to WS will be regularly discussed in Politicizing Magic. Besides folklore and literary tales, we will read critical works by a number of scholars in the field of gender studies, including Angela Carter, Maria Tatar, Karen E. Row, Jack Zipes, Johanna Hubbs, Marina Warner and others. This course is taught in English.

DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN AND RUSSIAN