HARRIET MENA HILL

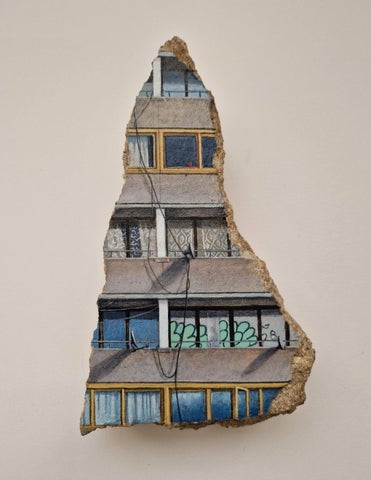

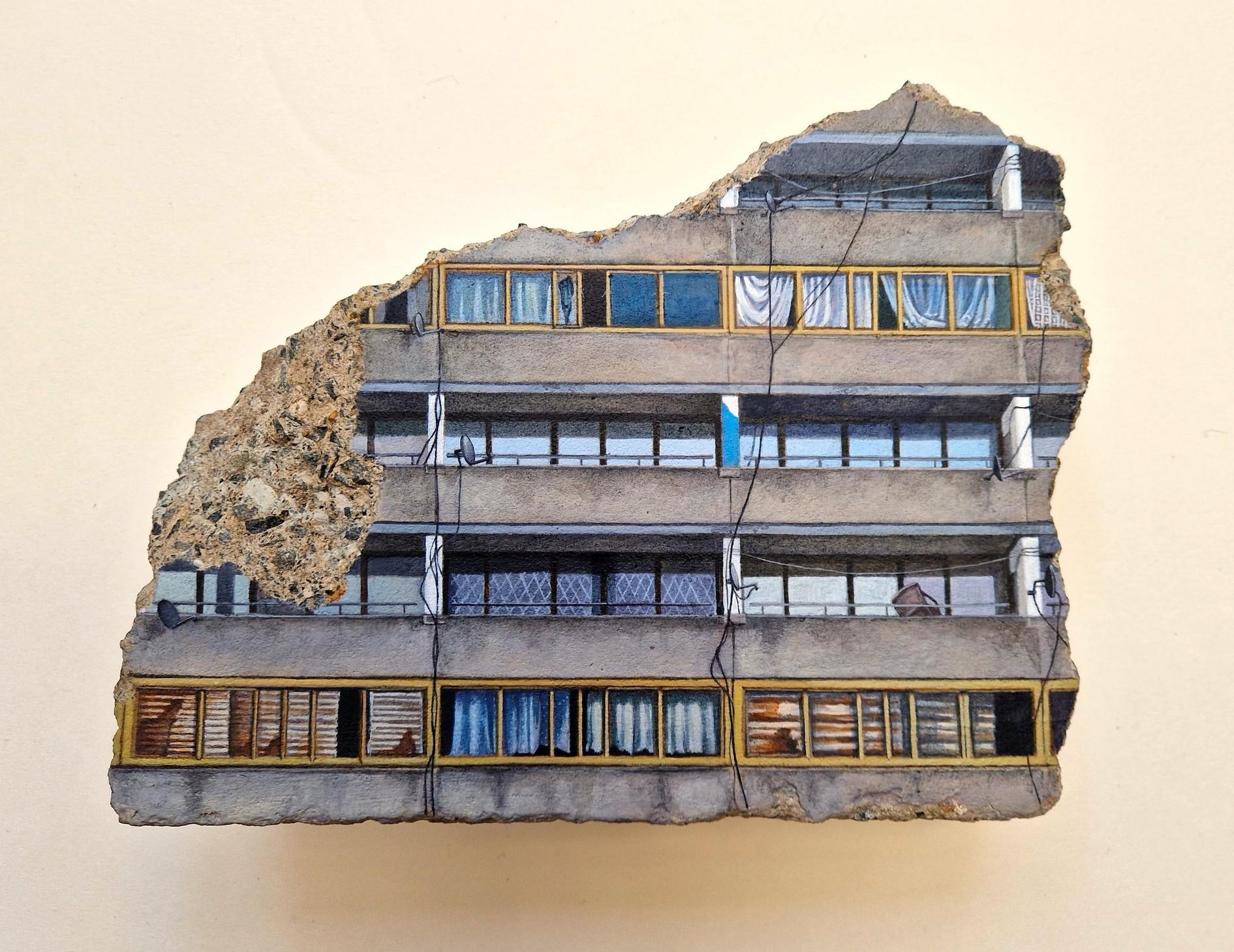

Torn Out (2023)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 23 x 14 x 6 cm

Dust in the air suspended Marks the place where a story ended

- From Little Gidding (1942) by TS Eliot

Built between 1963 and 1977, the 2700 dwellings of the Aylesbury Estate were initially regarded as flagship example of post-war clearance and modernist urban planning. The idyll did not last long and now a major –and inevitably contentious - regeneration programme is well under way, involving demolition on a vast scale.

Harriet Mena Hill started working on the estate running art projects with residents in 2018; as demolition progressed, she started collecting concrete debris from the sites recycling it as a series of “portraits” of the disappearing estate. These “fragments” have been shown in a number of prestigious exhibitions and entered collections including the Museum of London, as Harriet has, along with many others, attempted to shine a light on the social costs involved in such upheaval and GBS Fine Art is proud to have been working with her on the project for a number of years now.

The summer of 2024 sees an installation of 14 fragments - a sort of secular stations of the cross, raising awareness of the prevailing housing crisis - in the Gothic of splendour Wells Cathedral. We hope that it gives you pause for thought and that it could entice you to visit both the Cathedral and the gallery directly opposite.

Tracey Grace & Giles Baker-Smith GBS Fine Art

The Aylesbury Estate

The Aylesbury Estate, situated just south of Elephant and Castle in the London Borough of Southwark, was home to 7,500 people. Built between 1963 and 1977, it was one of the largest housing estates in Europe. It contained 2,704 dwellings, spread over a number of different blocks and buildings. It’s construction was part of an effort to rehouse some of London’s poorest families following the clearing of slum housing across this part of south London.

The estate was designed by architect Hans Peter “Felix” Trenton, son of a gifted artist, who brought his father’s interest in light and colour to the project. As a Borough Architect of Southwark he was very involved in developing post-war social housing with the Aylesbury Estate the most ambitious. His aim was to create “walkways in the sky” which would allow residents to make their way around the estate without touching the ground. Unfortunately, this along with the poor construction and under-investment in maintenance by the borough led to the estate being considered one of the most notorious estates in Britain. In 1997 Tony Blair made his “forgotten people” speech here – his first speech as prime minister.

Despite the £56M of funding received from Blair’s Labour government, the Aylesbury Estate continued to fall into disrepair and sustained high levels of crime and anti-social behaviour. From 2001 the council struggled with how to pay for the refurbishment of the estate and ultimately made the decision to demolish and redevelop the site. Demolition and redevelopment is being done in stages and is ongoing.

‘Behind the statistics lie households where three generations have never had a job. There are estates where the biggest employer is the drugs industry, where all that is left of the high hopes of the post-war planners is derelict concrete. Behind the statistics are people who have lost hope, trapped in fatalism.’

Tony Blair, 2 June 1997

Harriet Mena Hill

Harriet Mena Hill trained at the Camberwell School of Arts. She is known for her imagined architectural and geometric landscapes and her work is held in the Government Art Collection and St John’s College, Oxford.

Harriet’s home and studio are located close to the Aylesbury Estate and in 2018 she started working on the estate running art workshops for young people.

At the beginning of the Covid-19 lockdowns, when everything else had stopped, the demolition of the Aylesbury Estate was still active. Cycling through the estate as she did almost daily, Harriet picked up a piece of concrete from the demolition and was inspired to use it as a canvas to record both the architecture and the life that it once supported.

Since 2020, Harriet has created approximately one hundred works in this series.

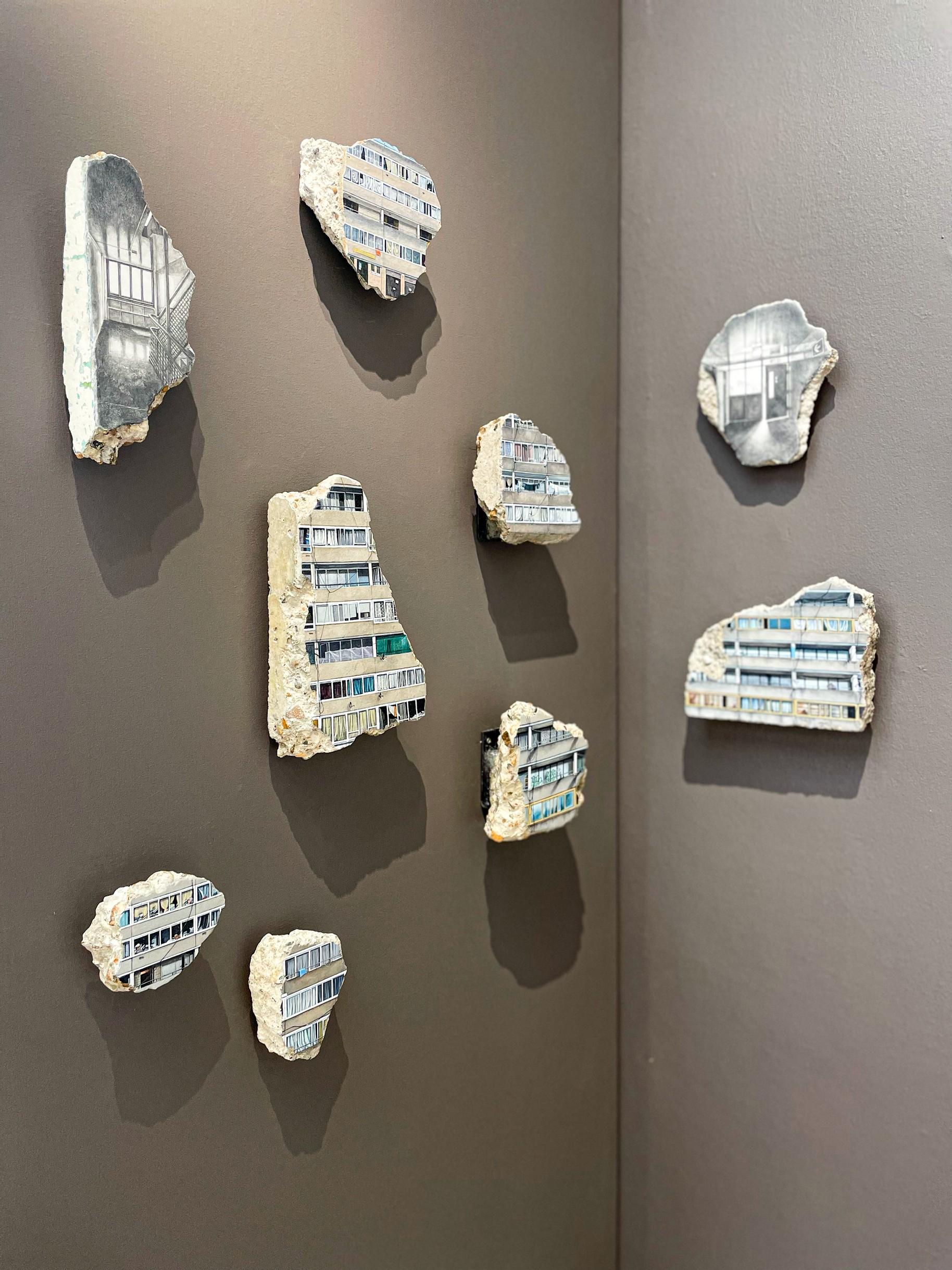

Installation of works from the Aylesbury Fragments series at the British Art Fair, September 2023

Red Doors II (2023), Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 23 x 21 x 10 cm

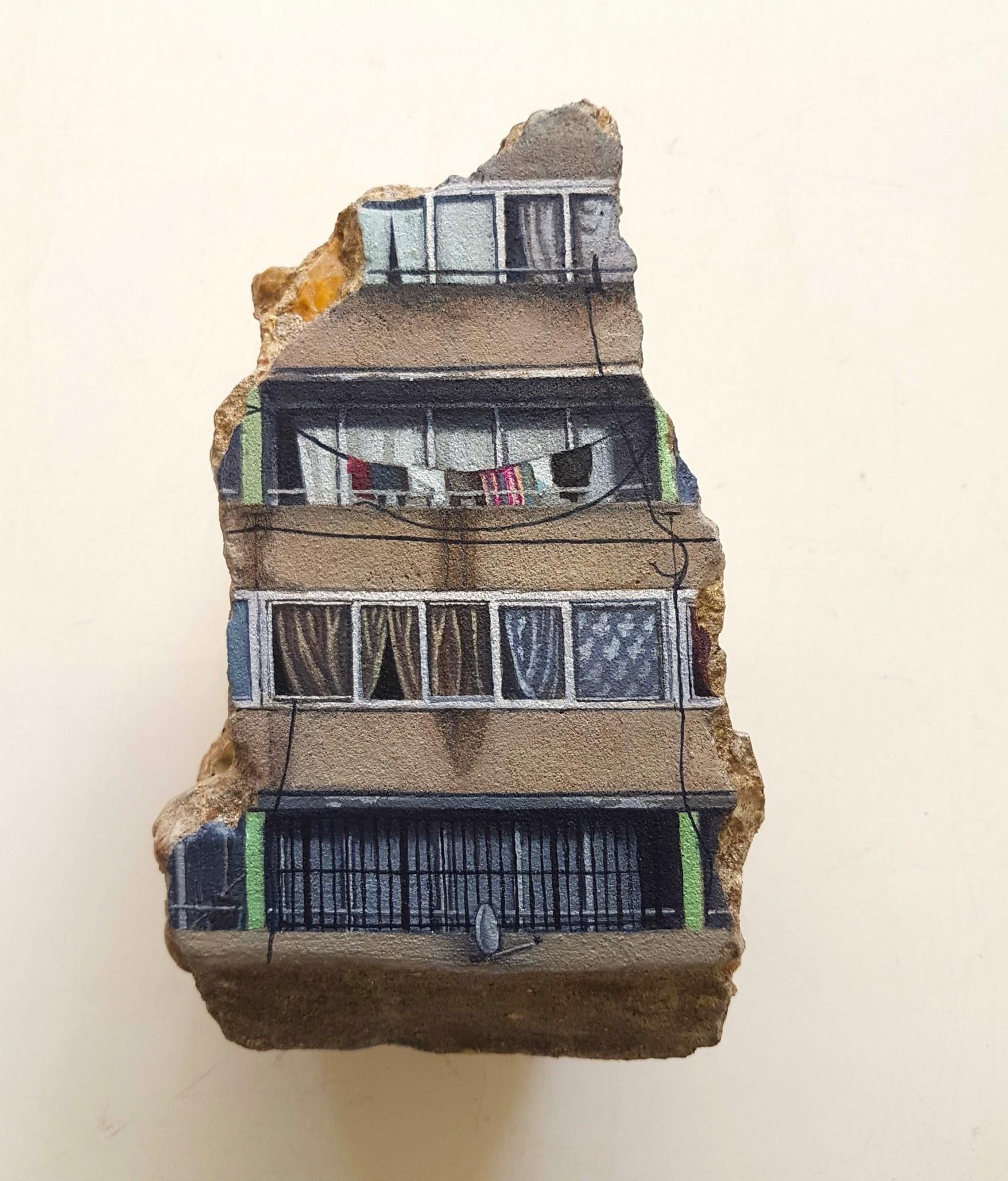

The Aylesbury Fragments

Painting can make the unseen visible. Since 2018 I have been working on the Aylesbury Estate in south east London, researching the connection of memory and place with residents, as they await the demolition of their homes. The paintings form an ongoing series The Aylesbury Fragments and have been created in an attempt to articulate this transition from being to unbeing, as described to me by residents coming to terms with the imminent destruction of their community on the site occupied by the estate for 52 years. The entrances and thresholds in the paintings are invitations to enter these liminal spaces.

The paintings repurpose salvaged concrete from the demolished housing blocks to form a fragmented visual record of the original buildings. They describe a formal beauty in the rigid geometric lines of the brutalist buildings. The structures are softened by human presence - a line of washing, some new graffiti, and trace the effects of time and the elements on the fabric of the buildings - the ingress of water cutting urban streams through concrete, the blooms of bright rust flowers.

The object becomes the subject, the tangible remnants becoming the substrate, prompting connections to the intangible past. The physicality of the substrate keeps the subject actively present as the illusory surface develops, an accumulation of memories fixed in particles of pigment fused to the pitted concrete surface.

These paintings are a testament to the resilience of a community living through extraordinary circumstances. They evidence a landscape and environment that did exist and that mattered.

--

Harriet Mena Hill, 2024

Blue towel 2 (2022)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 14 x 11 x 5 cm

A common misconception is that the word Brutalism derives from the word brutal: in reality it probably came from the French expression ‘béton brut’: French for ‘raw concrete’ and coined by the architect Le Corbusier during the construction of Unité d’Habitation in 1952.

Historic England, A Brief Introduction to Brutalism

The course of water and time (2023)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 17.5 x 11.5 x 7 cm

Blue pillar on Wendover (2023)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 21 x 27 x 5 cm

Elergy: The Aylesbury Fragments (2022)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 19.5 x 14 x 13 cm

Water out of sunlight (2022)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 30 x 19 x 8 cm

Where Thomas Aquinas supposed beauty to be quod visum placet (that which seen, pleases), image may be defined as quod visum perturbat -- that which seen, affects the emotions, a situation which could subsume the pleasure caused by beauty, but is not normally taken to do so, for the New Brutalists’ interests in image are commonly regarded, by many of themselves as well as their critis, as being antiart, or at any rate anti-beauty in the classical aesthetic sense of the word. But what is equally as important as the specific kind of response, is the nature of its cause. What pleased St. Thomas was an abstract quality, beauty – what moves a New Brutalist is the thing itself, in its totality, and with all its overtones of human association.

…Nevertheless this concept of Image is common to all aspects of The New Brutalism in England, but the manner in which it works out in architectural practice has some surprising twists to it. Basically, it requires that the building should be an immediately apprehensible visual entity; and that the form grasped by the eye should be confirmed by experience of the building in use. Further, that this form should be entirely proper to the functions and materials of the building, in their entirety. Such a relationship between structure, function and form is the basic commonplace of all good building of course, the demand that this form should be apprehensible and memorable is the apical uncommonplace which makes good building into great architecture.

From Reyner Banham’s essay on The New Brutalism, first published December 1955

Where will we meet when this is gone? (2022)

Drawing on salvaged concrete; 22 x 21 x 4 cm

“The estate was like a shiny new penny. It was lovely. It was really lovely. It’s hard for me to paint a picture for you but it was a beautiful place to live … The community side of it, you know? I mean you knew all the neighbours … You know you would never have got that sort of community in a row of houses as you did with the landings …”

Michael Romyn, London’s Aylesbury Estate: An Oral History of the Concrete Jungle (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020)

Cool boxes (2023)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 10 x 13 x 6 cm

Roland Way (2021)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 16.5 x 18.5 x 5 cm

Green grafitti (2023)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 18 x 18 x 10 cm

Boilerhouse portal 2021

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 28 x 12 x 13 cm

Open Window (2024)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 16 x 16 x 5 cm

Water out of sunlight 2022

Drawing on salvaged concrete; 20 x 11 x 6 cm

Nightlight - after the rain 2022

Acrylic on salvaged concrete; 17 x 12.5 x 5.5 cm

Studio installation of works from the Aylesbury Fragments series

View available works from this series HERE. Or on Artsy.