GRAFT gadfly THIRTEEN

Gadfly is supported by & Columbia University Undergraduate Philosophy Department

Editors

Editors-in-Chief

Aharon Dardik & William Freedman

Managing Editor Eitan Zomberg

Chief Article Editor Ray Knapick

Chief Column Editor Amelia Landis

Chief Interview Editor Oscar Luckett

Discussion Coordinator Xavier Stiles

Chief Design Editor Michi Parsa

Chief Art Editor Mim Datta

Editors

Copy Editors

Ignacio Hale Brown, Jayin Simh

Article Editors

Tessa Bannink, Yael Bright, Ignacio Hale Brown, Shrina Dong, Nora Estrada, Bohan Gao, Imme

Koolenbrander, Joseph Said Kwaik, Annie Lind, Daniel Nitu, Telvia Perez, Jayin Sihm, Sebastian

Verelli, Iris Wu

Columnists

Brittany Deng, Mica Helder-Lindt, Yongjae Kim, Daniel Knorek, Josephine O’Brien, Hanbo Yang

Interviews Editors

Camille Duran, Artemis Edison, Yunah Kwon, Yoav

Rafalin, Oscar Wolfe

Artists

Michi Parsa, Mim Datta, Anna Bruhn, Cornelia

Manzi, Aaron Shklar

Letter

Reema Zhalka, ed. Bohan Gao

Fleeing the Feed: Thoughts on Social Media and Girard’s Mimetic Theory of Desire

Daniel Knorek, ed. Joseph Said Kwaik

Songs of Eternity, or Wisps in the Ether

Ignacio Hale Brown, ed. Daniel Nitu, Sebastian Verelli

The Orace and the Loom: AI as Failed Graft

Payge Hardy, Ed. Iris Wu, Imme Koolenbrander

Gentrification as a Skin Graft: An Ethical Failure Masquerading as a Cure

Christopher Smith ed. Telvia Perez, Joseph Said Kwaik

The Transparent Connection: An Existentialist View of Identity

Ryan Marienthal ed. Jayin Simh, Telvia Perez

Make Again: The Fiction of Renewal

Ariel Vargas ed. Iris Wu, Annie Lind

Perfectly Powerless: The Paradox of Girlboss Feminism

Brittany Deng, ed. Imme Koolenbrander

Transcending Kith and Kin: Michael Morris on Group Identity

Oscar Wolfe ed. Yoav Rafalin

Fluid Divine Bodies: Benjamin Sommer on Syncretism, Coproduction, and God’s Bodies

Yoav Rafalin ed. Oscar Wolfe

Letter from

As a club engaged and invested in academic philosophy, we’ve heard no shortage of criticisms of our discipline. Philosophy endures accusations of being solely concerned with abstract theorizing, of being unrooted from the real world. In some ways, we are sympathetic to elements of this critique. Fundamentally, philosophy deals with conceptual matters. Unlike the medicines and agricultural practices we get from biology, there are no concrete innovations or discoveries to measure the merit of a work of philosophy. There are no philosophical machines or instruments that would verify the success of our discipline’s axioms.

This tension between grounding and abstraction is one that the entire history of philosophy has grappled with, but few proposed solutions are as famous as René Descartes’: I think, therefore I am. Descartes responded to philosophy’s central contradiction with

radical skepticism, asserting that the only claims that could be known were those that were true by virtue of pure logical necessity. In doing so, Descartes took up the role of the philosophical hermit, secluding himself from the complexities of the outside world, rooting his thoughts only in the internal clarity of the mind.

While one might see Descartes’s project as admirable, we at the Gadfly have a hard time seeing it as anything other than fundamentally flawed. In his attempt to ground thought in the objective, Descartes necessarily avoids massive swaths of the human experience. His attempt to refine philosophy into a hyper-rationalist, modernist discipline ultimately privileges disembodied reason over the messy, embodied complexity of the rest of human life. In her essay “The Cartesian Masculinization of Thought,” Susan Bordo describes this as “an attempt to escape from history, culture, and

the Editors

human finitude.” For Bordo, the result is a kind of philosophical barrenness, a discipline that forgets the very ground from which human thinking occurs. Descartes’s approach, while elegant, is built on a narrow foundation that limits the ideas it is able to produce. The system’s problem is not its correctness, but its scope.

Still, the appeal of Descartes’s approach is hard to deny. There is something unavoidably attractive about the dream of an epistemology modeled after mathematics: clean, axiomatic, and airtight. Descartes offers philosophy a robust root system on which to stand, a world in which moral and political questions might be resolved with the precision of a proof, where uncertainty is an error to be corrected rather than a condition to be endured. It’s a comforting fantasy, a world where reason alone can solve any problem. But this vision, no matter how appealing, collapses under the weight of human complexity.

At the other extreme from Descartes, philosophy can drift into abstraction for its own sake. One struggles to find the urgency behind the fiery debates between Neoplatonists and Boethius over whether harmony is a gift from the Demiurge or intrinsic to reality. That such questions could dominate philosophical discourse reveals an inverse danger: a philosophy insufficiently grounded in a common human experience. Unlike Descartes’s philosophy founded on universal certainty, which is abstract in its own way, this philosophy is abstract due to the varied dogmatic assumptions it relies on that most people hesitate to accept. Philosophy like this becomes so detached from the world that it feels more like an elaborate performance— beautiful, perhaps, in its complexity and rigor, but ultimately forsaking any living connection to the human condition.

Where Descartes’ problem was planting too few

roots—so cautious in his foundations that his philosophy could only grow in narrow, rigid forms— this tradition represents the opposite flaw. Here philosophy becomes unstable: sprawling, ornate, and systematic, yet resting on assumptions that bear no real relation to the world we inhabit. Far too often, these systems rely on dogmatic premises that, while internally coherent, offer little to the convoluted realities of human life. The result is a discipline that expands endlessly but struggles to produce conclusions we can find meaningful or true.

Philosophy, then, must find another way. If it cannot take independent root, nor survive as a floating, untethered system, it must graft itself onto the richness of lived experience.

Grafting is a process of joining—taking something delicate, something unable to survive alone, and binding it to a living base that can sustain it. The graft remains distinct, but it grows through its attachment to something larger. Sometimes it strengthens the host; sometimes it draws from

it. But either way, the resulting synthesis is more than the sum of its parts: two distinct elements, not indistinguishable from one another, but nevertheless inseparable. We believe the best philosophy is done by those who embrace this ethos—who draw from the nuances of human life without being consumed by them, who remain distinct from, yet sustained by, the world they inhabit.

Philosophy must grow this way. It cannot be grounded solely in the irreducible axioms of Descartes, nor built upon the intricate but untethered systems of the mystics and scholastics. It must be nourished by life itself. New ideas do not emerge from pure logical necessity, nor from speculative invention. They emerge from the messy, discursive relationships between people—planted in history, culture, and lived experience. Good philosophy is done not by those who isolate themselves from life, but by those who live fully within it. At the Gadfly, we do philosophy because the world we inhabit allows and dares us to question it.

Our focus on philosophy emphasizes its intersections: with literature, with science, with politics, with art, with life itself. We believe that philosophy divorced from a robust experience of the world is missing something crucial. Our writers and editors create extraordinary work precisely because they recognize that their diverse lives are not an obstacle to philosophy, but its subject and deepest source. At The Gadfly, we have tried to honor this conviction. In this issue, you will find essays that take philosophy beyond its traditional enclosures—grafting it onto new materials, binding it to lived experience, and letting it grow in unexpected directions.

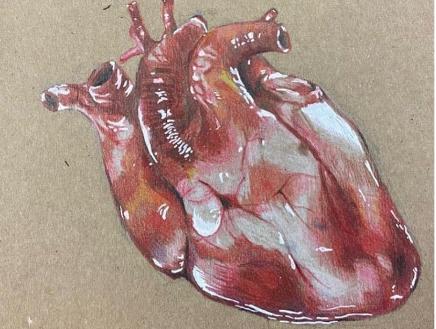

Reema Zhalka’s poem Rejection sets this tone. The gravity of her words practically recreates the sensation of weaving a painful intimacy, stitching together futility and yearning with raw, tactile imagery. Each line pulls tighter the thread between bodily decay and emotional collapse, binding family wounds in silence. The act of mending becomes both tender and tragic, a ritual

of hope and hopelessness performed on rotting material. Zhalka’s message ends hanging in place, the condition of being tied too close together articulating a love both offered and rejected in equal measure.

Daniel Knorek’s Fleeing the Feed: Thoughts on Social Media and Girard’s Mimetic Theory of Desire explores the tangled roots of desire in the age of social media, turning to René Girard’s theory of mimetic rivalry to understand the endless cycle of envy and self-blame modern platforms cultivate. Through personal reflection and philosophical analysis, Knorek explores how capitalism exploits our most intimate insecurities, grafting artificial needs onto our sense of self. His essay challenges us to recognize the hidden violence in comparison—and to seek peace not by fulfilling our desires, but by questioning them.

In Ignacio Hale Brown’s Songs of Eternity, or Wisps in the Ether, the fleetingness of human life meets the strange endurance of art. Reflecting on ancient statues, epic poetry, and Renaissance sonnets, Brown

explores how fragments of individual lives—real or imagined—are grafted into the works they leave behind. Drawing on Shakespeare, Gilgamesh, and Ozymandias he considers how art does not merely preserve memory, but breathes new life into it. Through the fragile vessels of language, sculpture, and imagination, lives long past continue to grow, transform, and reach us in the present.

In The Oracle and the Loom: AI as Failed Graft, Payge Hardy reveals artificial intelligence not as an extension of human knowledge, but as a fraudulent graft—a system that mimics wisdom while hollowing out the very conditions that make truth and deliberation possible. Through dialogue with Plato, Kant, and Arendt, she exposes the profound epistemic and political dangers of surrendering judgment to machines.

In Yongjae Kim’s Phenomenology of a Subterranean Lyric Documentary Walker Evans’s secret subway portraits become the starting point for a meditation on how art grafts meaning onto the fleeting moments of

human life. Engaging with Susan Sontag’s critique of photography and Maurice MerleauPonty’s phenomenology of perception, this essay explores how Evans’s images balance documentary precision with lyrical interpretation. In capturing the dim, unguarded faces of a vanished world, Evans does more than document— he grafts human experience onto photographic form, preserving presence even as it slips into absence.

In Gentrification as a Skin Graft: An Ethical Failure Masquerading as a Cure, Christopher Smith explores how gentrification, like a graft gone wrong, integrates itself into the body of a community only to corrode it from within. Through the lenses of Martha Nussbaum’s capabilities theory and Marx’s analysis of labor and alienation, Smith reveals how surfacelevel prosperity masks deeper displacements of agency, play, and affiliation— and calls for a reevaluation of economic “progress” through a moral lens.

In Ryan Marienthal’s The Transparent Connection:

An Existentialist View of Identity, the pursuit of idealized selves becomes both a source of despair and an opportunity for transformation. Drawing on Kierkegaard’s account of existential alienation and Nietzsche’s vision of self-creation, this essay explores how attempts to graft abstract identities onto ourselves can sever us from the realities of who we are. It argues that true identity is not imposed from the external world, but designed from within—woven from our limitations, histories, and daily acts of becoming.

In Make Again: The Fiction of Renewal, Ariel Vargas exposes the MAGA project as an impossible graft: an attempt to stitch a fabricated past onto a fractured present. Through an analysis of architecture, political mythmaking, and cultural reproduction, this essay shows how MAGA’s promise of restoration inevitably creates a fiction—one that denies history, distorts identity, and weaponizes nostalgia in the service of power. In Perfectly Powerless: The Paradox of Girlboss

Feminism, Brittany Deng unmasks the graft inherent in strains of girlboss feminism, drawing on Michel Foucault’s theory of power and Serene Khader’s critique of the Judgment Myth to explore how the aesthetics of confidence and choice can become mechanisms of control.

Oscar Wolfe’s interview with Professor Michael Morris frames culture itself as a living graft: stitched together from instincts that once kept small bands alive. In this conversation, Morris traces how our peer loyalties, our hunger for heroic status, and our reverence for ancestors intertwine to create the cultures we inherit—and sometimes reshape. In an age of crisis, when tradition and innovation are forcibly spliced together, Morris warns that understanding how identities evolve is essential if we are to avoid mistaking nostalgia for progress.

In his discussion with Yoav Rafalin, Benjamin Sommer dismantles the myth of religious purity, revealing a tradition grown through endless grafting: of ideas, practices, and

metaphysical visions.

Ancient Israel’s conception of God, he argues, was not a static inheritance but a hybrid organism— shaped by internal debate, cross-cultural contact, and evolving perceptions of divine embodiment. Sommer challenges us to see theology itself as a living coproduction, a body stitched together across time by the persistent human yearning to grasp the ineffable.

Philosophy must take root somewhere, but it cannot be in isolation. It must draw strength from human experience without being wholly absorbed by it. Grafted thought is thought that can grow, that can evolve and adapt. This issue of the Gadfly carries that conviction. Its essays, poems, and reflections engage with literature, science, technology, pop culture, and politics—not as distractions from philosophical thought, but as its source and its context. In helping to cultivate this issue, we have tried to hold true to that belief. As outgoing editorsin-chief, all we can do is hope that we have been good stewards of this publication

and community, and that the parts of ourselves grafted onto every page of this magazine will continue to grow in new directions we could never have predicted, shaped by the voices and visions of future contributors.

Best, William Freedman and Aharon Dardik

Rejection

Reema Zhalka Ed. Bohan Gao, Ignacio Hale Brown

There’s no sense in sutures over necrotic tissue. But the faithful needle threads together joining patches of yarn squares in neat, tidy rows coiled tight around the skin gripped in place despite its inflammation.

Thick fabric stretches over the chasm of the mouth –sewn shut.

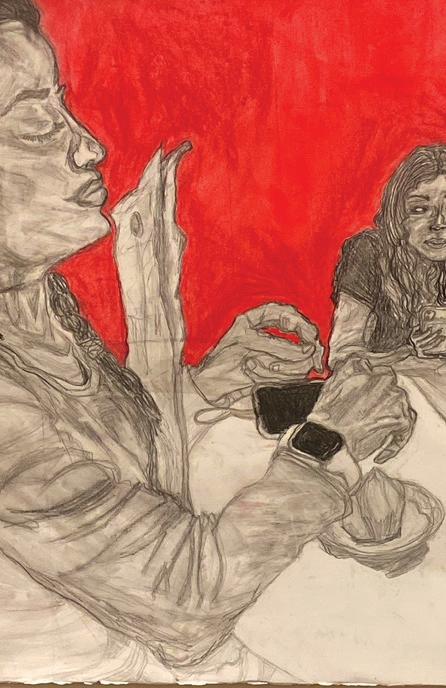

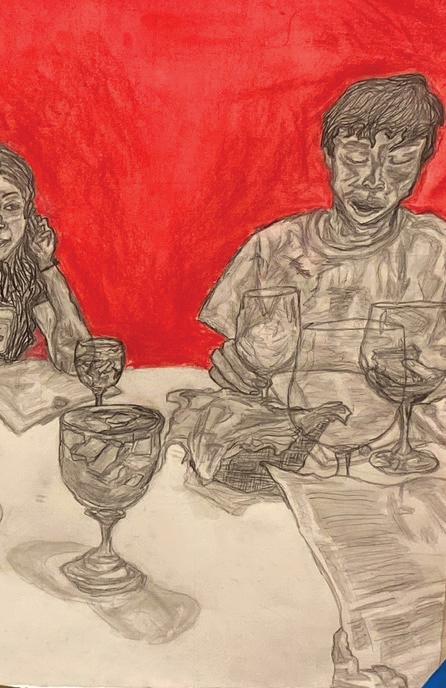

And though the tip dulls it still sews attempts to mend, to make amends –to stitch us back into place at the dinner table.

No amount of embroidered hearts can disguise a festering breeding ground, yet here we still sit eating my mother’s spread all homemade never once looking up to say thanks, our mouths too full for words.

I’ve always been fascinated by the monetization of our relationships that has taken hold with the advent of the Internet Age and the rapid increase in the sheer volume of advertising. I grew up watching an unhealthy amount of television and YouTube, and the impact of advertising upon the individual has intrigued me for as long as I could critically consider the point of an advertisement. Acknowledging the presence of products is almost a prerequisite to navigating the digital and physical realms. From visual advertisements along the tops of subway cars to a fifth of primetime television going to commercials, we are

simply overwhelmed with the opportunity to see things we don’t have. Social media is the ultimate manifestation of this phenomenon: what was once a fun way to keep in touch with your friends has gradually morphed into a premier opportunity for capitalism. There is no shortage of work done on the ways in which social media enforces an ideology of collective, non-individualized, trendbased consumerism, but I have always been more interested in its impact on the individual: what does it mean to be an individual engrossed in such a massive web of consumerism? There is no shortage of evidence of its impact on

body image, self esteem and overall mental wellness, but the motivating factors behind those findings are wide-ranging. It was in my dive for discussion on this topic that I stumbled upon René Girard’s theory of mimetic desire.

The core of Girard’s theory of mimetic desire lies in the belief that our desires are not inherent. Rather, they emerge from a communal endowment of value unto goods and qualities. Due to this communal understanding of value, we are inclined to want and take things that other people have, grafting them onto ourselves through some sort of manifested violent act. This is mimetic desire in essence. Girard writes in his 1972 text Violence and the Sacred, “Whenever the disciple borrows from his model what he believes to be the ‘true’ object, he tries to possess that truth by desiring precisely what this model desires. Whenever he sees himself closest to the supreme goal, he comes into violent conflict with a rival. By a mental shortcut that is both eminently logical and self-defeating, he convinces himself that the violence itself is the most distinctive attribute of this supreme goal.” Girard’s understanding of desire and the inherent comparison within it explains the roots beneath

social media’s obsessively comparative nature, and helps explain the inherent frustration and mental strife that accompanies it. In order to fulfill that desire and break through to a satisfactory conclusion, Girard finds it absolutely essential that violent acts emerge as the catalyst towards the end goal. This is where my personal experience with mimetic desire comes in, and how I did my best to control my unconscious, uncontrollable tendency to envy.

In the summer of 2024, I had found myself growing more and more insecure about my self-perceived lack of success. I was going home for the summer instead of landing a prestigious internship in New York City, cramped up at home instead of traveling the world, and just generally found myself unable to meet the lofty goals I was setting for myself. Others were taking trips abroad with their families, while I was driving up to my local Walmart to buy a pint of ice cream. I wanted to take their best moments and make mine comparable, grafting these inauthentic, curated experiences onto my own life, a manifestation of my own unconscious mimetic desire. Comparison is the thief of joy, after all.

After spending way too much time looking at what other people were doing, and being fully aware that the way I was comparing myself to others was unhealthy, I tried to make a change. I “soft-quit” social media at the beginning of the academic year. I deleted X/ Twitter, TikTok, and restricted the use of Instagram and Reddit to my laptop for what I called “business purposes only.” If I needed to access important information through those platforms I would use them, but would do so consciously and with full understanding that gathering that information was the only thing I could use them for. I successfully knocked my screen time down by a few hours over the following five months. I read more, got outside more, and spent more time with my close friends. Despite those happy moments, living in NYC and trying to hold onto that blissful mindset still felt like a big challenge. After all, New York City is one of the biggest cultural epicenters in the world, and escaping the onslaught of knowledge was basically impossible, no matter how many guardrails I placed for myself. Everywhere I turned, all I could notice was advertisements for new products, advertised by

people and companies that I envied for various different reasons. I heard about the successes of others and was proud of them or happy for them, yet I simultaneously found myself quietly jealous of their successes compared to my adequacies, or occasional inadequacies. When it came down to it, I realized that Girard’s theory perfectly encapsulates my—and many others’—feelings on social media and helps explain how it makes us feel the way we do. Mimetic desire causes us to villainize ourselves, to treat ourselves—whether it be our background, our achievements or our skills—as the very reason for our failures, the very reason for us not having what we want.

Girard takes steps to distinguish mimetic desire and mimesis from imitation, which he sees as a conscious replication of another’s behavior, which leads to positive reinforcement and learning. Mimesis, on the other hand, is a wholly subconscious negative response that often leads us into rivalry, our desire for possession of that object—and inability to have it—leading us to find ways to purge ourselves of those negative feelings of not-having,

either by taking the object or finding a way to eliminate the roadblocks to possessing it. In this lies the catch in Girard’s theory that hones in on our modern communities: Desire is not desire if the person who desires has the object of interest. There must be some inhibiting force that is keeping the individual from having the object to fulfill that desire. Girard claims this withholding figure to be the scapegoat of mimetic theory, who plays the unfortunate role of suffering in order to create an artificial peace through violence— physical, mental, social, et cetera—that excises the withholder of the desired from the psyche of the desirer. There are two types of

withholding mediators within the umbrella term of “scapegoat,” those being the external mediator and the internal mediator. The external scapegoat serves as a distinct entity: someone who holds the quality or object of desire but is wholly outside the sphere of the individual. I may want to swim like Michael Phelps, but I am not a swimmer on the level of Michael Phelps and cannot reasonably consider myself his rival, for example. Therefore, I do not want to fight Michael Phelps: He is simply on a different level than me. In many modern situations, the external mediator’s desirable qualities actually weave themselves in with the object of desire, or even become the

object of desire itself. Bradley Hoos of Forbes writes about this extensively in his article Mimetic Desire: The Secret Behind Effective Influencer Marketing. “When any creator associates themselves with a brand, psychology tells us that it forms an unspoken promise in our minds. We begin to associate that brand with an identity we desire. Influencer marketing works because we naturally want to organize ourselves into groups that make us feel safe and normal within them.” Hoos draws a strong connection between the manifestation of the external mediator and the manifestation of the object of desire as being intrinsically linked concepts, a duo that permeates the vast majority of our modern advertising culture. However, on the other end of the spectrum lies the internal mediator, the one many people find themselves matching up to and the one

that is growing increasingly more common when social media more intimately occupies our understanding of our relationships to other people. These are the people we can form rivalries with because they are accessible. They are our coworkers, our classmates and our family members, no longer characters on our screens or our billboards. Their possession of things that someone near them wants spurs a more direct comparison, and therefore a more direct form of action.

Modern readers of Girard are conflicted on how social media and the internet have reduced the degree of separation between the external mediator and the desirer. Some Girard readers believe “cancel culture” to be the next iteration of this violent phenomenon: the reckoning with painful external mediators through societal

rejection, so to speak. In fact, the webpage MimeticTheory. com—managed by an offshoot organization under the Catholic University of America, strangely enough—describes it as “bloodyless scapegoating.” However, I believe that my experience with social media offers an alternative lens to the phenomenon. Rather than purging undesirable people around us who we believe contribute to our have-nots, the external scapegoat has pushed into our self-reflection. Although there are plenty of people who believe that their personal failures are due to external forces, there are just as many people who see their failures as a natural extension of themselves. We have become our own scapegoats through our constant, forced opportunities to compare due to the new level of intimacy we have with what we perceive to be the qualities of one another as a result of our social media habits and as a result of our insistent desire to connect with others through unhealthy comparisons. This becomes a cyclical phenomenon of purging, one that Girard mentions extensively in his writings in the 1988 collaborative work Violent Origins: “To the entire community, the crisis and its

resolution become a positive model of imitation and counterimitation. The mimetic urge has now turned peaceful and culturally productive, because it consists in doing again and again what the victim did or suffered that resulted in a great good for the community.” Through social media’s central role in advertising, almost every mediator has become internal, one way or another. We see someone else hustling for several hours before their workday or their classes and pity ourselves for not being that driven or that effective, and this is merely one example. My past only affirms this: Seeing other people’s awesome vacations and cool internship experiences inspired me to want to do things to get myself to that level, but for one reason or another, I could not. Our desires have intensified and become internalized to such an extent that they are simply a natural extension of our insecurities, and capitalism has swooped in like the bird of prey it is and exploits our desires to perfection.

My desires did not go away when I stepped back from social media. I still wanted that internship, I still wanted to travel abroad, and I most

certainly still wanted things. I spent a lot of money on nice food, video games, books, and other things I’m personally interested in. However, without a model to compare to, I wasn’t encountering that same tension. What was my scapegoat? How did I push through that concern that I had been feeling before without fulfilling my desire? Girard believes that the key to not enacting that intense violence is to purge via lesser, “unconscious” violence. Social media created a plethora of scapegoats, a wide-ranging group of individuals who I envied for various reasons and therefore developed unhealthy perceptions of. In this case, deleting social media was that “unconscious” violence, as it allowed me to excise those scapegoats from my mind, literally removing them from my psyche and preventing the existence of the scapegoat in the first place. Deleting social media served as the removal of an external mediator beyond the physical mediators. Instagram, to me, held all of that which I desire but I am neither able to acquire nor destroy. Although I didn’t use social media explicitly to feed those feelings of desire, the lack of that presence within my life prevented me from running into those situations

again, reaching a similar level of artificial peace.

At the end of the day, my experience in the context of Girard’s theory is not just about desire and what you think you want—it’s also about the validation experienced through playing into the systems that permit his theory to function to the extent that it does. Existing within a society that glorifies consumerism and buying as a whole continuously presents the individual with opportunities to form those unhealthy relationships with mediators, both external and internal. I think, after having plenty of time to reflect, that social media is not healthy for us as individuals. This is unsurprising in many ways: there are plenty of studies as to the negative contributions of social platforms upon mental health, fiscal responsibility and relationship-building skills. With Girard’s theory in mind, the removal of social media—exemplified by my experience—inherently limits the ability to play into this intensification of mimesis and the self-villainization we have become so familiar with in our day-to-day digital lives. When it comes down to it, the internal impact of advertising and the potential for those negative

interactions can never be fully purged. The can will simply continue to be kicked down the road: It is our jobs as players in that mimetic system to recognize it as best we can and live more consciously. When we live in the moment, think about our actions and work hard to ensure that we are not unconsciously taking up these unhealthy mimetic dynamics, we can perhaps give ourselves just a moment of respite from the difficulties of the world around us. We cannot escape the onslaught of capitalist, comparative consumerism, especially within the American context. What we can do, however, is learn to love ourselves. Even if that means loving ourselves for our havenots.

Songs of Eternity or Wisps in the Ether

Ed. Daniel Nitu, Sebastian Verelli

Ignacio Hale Brown

Afew months ago, I stood for a while at the Metropolitan Museum of Art gazing into the eyes of an Etruscan statue. There was a magical, lifelike quality to it, as if blood flowed through the otherwise static terracotta. Somehow, in the frozen clay, I could feel the woman it was modeled after standing before me. She had been captured—stuck in form but unstuck in time—and her presence transported to the present day.

Only one thing is certain in human existence and in the existence of all living things: death. No matter how hard some people may try, we can never evade it forever. Everyone, someday, will return to the dust from which we came. But there is something magical about dust. It isn’t a river that dries up; it isn’t a flame that burns out. Though invisible, it keeps floating around forever, filling our lungs as we breathe in tastes of the past.

Man may be ephemeral, but the idea of him is not. Our creations seem indomitable: ancient palaces still stand; ancient hymns are still sung. Though these things, too, will one day wither and fade away—buildings become ruins, songs become fragments—they still last millennia

as they watch over countless generations of the men and women who made them.

Is this not, then, a form of life? In the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest stories ever written, the titular king embarks on a quest to find immortality. After much toil, he is able to find a plant that grants eternal life. But the moment he lets his guard down, a snake appears out of the water and steals the plant away. All hope seems to be lost. Gilgamesh will remain a man and die as eternity remains forever a stranger. But the epic closes by telling its readers that “this too was the work of Gilgamesh... [who] engraved on a stone the whole story.” I sit here, 4,000 years later, reading the words of Gilgamesh, watching him move and breathe through his journey. In The Iliad, Achilles too is forced to face his mortality as he readies for battle. He has two options: he must decide if he wants to run away and live a long life or fight and have a short one with a legacy. If he fights, he says, “My return home is gone, but my glory shall be everlasting.” In the end, he fights and, of course, dies. But his glory is indeed everlasting. Though Achilles may be fictional, The Iliad has rendered him as real as Gilgamesh. He exists in the

collective mind of humanity just as Gilgamesh does. Like Achilles, Homer, the legendary author of The Iliad, was likely not a real person. But as he exists now, he may well have been. Every time The Iliad or The Odyssey is read, its readers conjure up a man in Ionia in the 8th century B.C., standing before a crowd and reciting his great epics for the first time. The ‘lives’ of Homer and Achilles created a story, and their story lives now, 3,000 years later, in the minds of billions. This is a sort of afterlife, and yet it isn’t an imagined world where our consciousness continues. We remain truly dead: there is no more body, no more soul. But still, something seems

to live on. Can a person’s life be grafted into art, be made immaterial? Or rather, can one bestow life onto the material pages? Is this life frozen, still visible but a long-dead fragment of the past? Or does it continue to grow, somehow still breathing, still being that same person, as it survives and evolves amongst humanity?

Four hundred years ago, William Shakespeare grappled with these same questions. Throughout his sonnets, he presents an idea that has been dubbed the “eternizing conceit.” His Sonnet 15 compares men to plants, speaking of how they grow and bloom, but this is all momentary, and we will

eventually decay. He describes himself as being in a war with time for someone he loves. A war against time seems unwinnable for any mortal. And yet, Shakespeare closes the poem with “as he [time] takes from you, I engraft you new.” He is winning the war against time. He has taken a piece of the life of his love and placed it into a poem. But her life hasn’t merely been printed onto a page; it has been grafted. Shakespeare sees this poetry as something that is itself alive. In merging the person with the poem, he allows them to share sap, to share blood. They feed off of each other, each allowing the other to continue living.

He continues this idea in his famous Sonnet 18, which ends, “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.” The poem’s survival is the only condition for the survival of its subject. But how does this happen? Is a poem not a fixed image? It was written at a singular point in time, forever entrenched in that moment. Though read over and over again, the words will never change. And though she lived a long and full life, the woman in the poem is eternally limited to fourteen lines of Shakespeare’s perception as he wrote of her. It

is not truly this woman whose life has been made immortal. Instead, a new version of her has been created. It is a reduction of what she truly was, and yet with this reduction a form of her is able to live forever.

In Sonnet 55, Shakespeare seems to clarify this. “Wasteful war shall statues overturn,” he writes, “and broils root out the work of masonry.” Even great monuments come tumbling down. It is not through material record that Shakespeare is able to renew life. Instead, the poem serves as a “living record of your memory.” Again, it isn’t a frozen image, but alive. “You live in this, and dwell in lovers’ eyes,” he says. The attention on it being specifically the eyes of lovers shows the key to this immortality. Words themselves do nothing for the subject. It is in the way they are read that they come alive. Our minds revive the dead as they move within us.

This life does not only continue through literature but also in all art. Every surviving fragment is a vessel for a piece of the past. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem Ozymandias details the ruins of an ancient statue of a king in the desert. Words appear on the statue’s pedestal that read, “My name is Ozymandias, King of

Kings, look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!” Shelley follows this up with “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.” Shelley seeks to highlight a dissonance between the words the king had written and the state of the king now. He once ruled an empire, but that has now crumbled into nothingness. Yet to me, this does not symbolize the transience of existence. In fact, it shows quite the opposite: its permanence. The face and words of an ancient king, still here millennia later. In it, I can feel the weight of his being, just as I could with the Etruscan woman at the Met. A story or image of the past can be read in multiple ways. It can be a window, whose panes are looked through to glimpse faded memories of long-dead moments. Or it can be a bridge, bringing those moments into the present.

In his book After Babel, Franco-American philosopher George Steiner discusses what he calls “the informing sphere of sensibility”—the vast web of cultural context that surrounds any text at the time of its writing. At the center of that context is language itself: how it’s used, how it changes across place and

time, and how its usage relates to the physical world and to its literal meaning. As time moves on, the intricacies of the specific associations and implications of each word change. Because of this, we will never fully understand texts of the past. Instead, Steiner says, we must “translate out of time.” The words of Gilgamesh, Homer, and Shakespeare are not time capsules. The words may be (mostly) static, but the life they hold is not. With every generation, it takes on new meaning. It is influenced by the world around it and in turn, is constantly able to newly influence the world.

We generally think of life as the sum of experiences in a person’s existence. Though the physical selves of the individuals in these texts have died, the histories of the texts themselves are part of their existence. As the characters are conjured up in readers’ minds again and again, they are kept alive. It is not their lives, however, that are eternally preserved. It is the version of their lives created by the author, and then created anew by the reader, that lives on. The informing sphere of sensibility creates a fleeting moment around each work of art, as does its creator’s perspective. There is an aspect of the person it reflects that will

never exist again. But in reflecting it, it holds some of it. An impression of the person there once was. The woman whose eyes I gazed into at the Met is my imagined perception of the sculptor’s perception of her. But through this perception, a woman who would have died and been forgotten thousands of years ago maintains a form of life in the 21st century. This statue has become a part of her history.

This is the beauty of art. The art, the people in the art, and the art’s creators are all grafted together in a shared eternity. It becomes something new, a fresh life that is an amalgamation of all the pieces that formed it. The full story of Gilgamesh is not just what is told in the epic, and the story of Shakespeare’s lover is not just within his sonnets. The man that was Homer is not just the name of an unknown man printed on the cover of a book. The lives of Ozymandias and the Etruscan woman were not completed when they were sculpted and cast. As pieces of their lives are grafted into art, the presence of the statues, the poetry, the epics themselves, become part of their lives too.

The Oracle

Payge Hardy and the Loom: AI as Failed Graft

Ed. Iris Wu, Imme Koolenbrander

Artificial intelligence pretends to be our infallible oracle, a mind of silicon grafted onto the tree of human knowledge, touted as a source of instant enlightenment. We sought a machine that could mirror all that is known and illuminate what is not—yet, as Hamlet professes, “There are more things in heaven and earth” than are dreamt of in any algorithm. In our hubris, we have grafted a simulacrum of intellect onto a substrate that neither bleeds nor doubts, only to find we have created an uncanny specter of thought rather than its savior. Like a transplanted organ rejected by the host, this graft of “intelligence” has not fused with its body. Instead, it haunts us: an alien appendage with a voice of authority and no soul, promising truth without humility and delivering answers without understanding.

At the heart of this failure is a lack of epistemic humility—for true intelligence requires an awareness of its own ignorance. The ancient philosophers knew that to truly know is also to recognize what one does know—to sense the horizon beyond one’s grasp. Still, our artificial oracle knows nothing of ignorance. It issues pronouncements with unerring confidence, never stopping to

doubt or reflect. It cannot: we did not give it the capacity to question its own output or to contextualize its knowledge in the larger constellation of reality. Such systems do not think in any human sense; they generate outputs by identifying statistical patterns in language data, not by understanding meaning. AI calculates; it does not contemplate.

Everything is here: the minutely detailed history of the future, the autobiographies of the archangels, the faithful catalogue of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, the proof of the falsity of those false catalogues, the proof of the falsity of the true catalogue… Everything. But we, the imperfect librarians, have interpreted the gibberish.”

– Jorge Luis Borges, The Library of Babel

The result is an oracle of nothingness. Ask it to unveil some deep truth, and it will output something—yet does it signify anything? AI mimics the form of truth by recombining data patterns with breathtaking statistical prowess, and in doing so threatens to make a mockery of meaning. But still, it cannot tell sense from nonsense. A human sage, steeped in life,

might respond to a profound question with silence or careful ambiguity, knowing truth is subtle. The machine, by contrast, has no such humility: it will audaciously pronounce on matters far beyond its ken; it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. These allegedly intelligent machines generate billions of outputs delivered with the authoritative tone of knowledge. Yet peel back the curtain—and there is no Wizard of Oz, no sage insights—only a blind mechanism churning out sequences of symbols.

Our machine oracle holds no beliefs, no biases of its own (aside from the machinations and potentially skewed ethic of its programmers)—but neither does it grasp truth, because it does not seek it as something to be discovered, challenged, and refined through experience and reflection. Since Plato, truth has been treated not as a product to be delivered, but as a horizon approached only through dialectic, lived inquiry, and reflection. AI mimifies the form of truth, and in doing so threatens to make a mockery of meaning.

The philosophical truth is stark: what these systems lack is not just knowledge, but the very

capacity for understanding. They are prisoners of phenomena, of surface patterns, unable to glimpse the noumenal truths behind. We might recall Plato’s allegory: our machine sits at the bottom of the cave, expertly analyzing the shadows on the wall, never perceiving the Forms that cast them. It learns the form of appearance but never the form of reality. Likewise, Immanuel Kant drew a line between the world as it appears and the world in itself: our creation, for all its data, cannot cross or even toe that line. While both Plato and Kant recognized that truth lies beyond immediate grasp, they upheld human capacity— and the moral imperative—to reach toward it. AI, by contrast, remains blithely unaware there is something to reach for. Its alleged intelligence is an imitation circumscribed by what has been fed; it lacks the spark by which the mind reaches beyond mere data to the truth behind it.

In cognitive terms, this “intelligence” is an idiot savant of sorts—a Chinese Room shuffling symbols with prodigious speed. AI produces outputs that to us look meaningful—yet like a hapless translator wantonly following instructions

without comprehension, the machine can never know what its messages mean. The phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty insisted that true perception rises from our embodied “Being in the World”—that is, from a lived, bodily entanglement with the world that grounds all perception and meaning; by contrast, our AI floats in a void of data, untouched by the weight of experience. It plays at the language-game as an outsider, stringing together coherent phrases without ever inhabiting their meaning. It is, in a word, disembodied, not just lacking a body, but lacking the lived situation that endows symbols with significance. AI pronounces on the patterns of dawn, having never felt the warmth of the sun; it predicts human grief from data, having

never tasted the bitterness of loss. In this gulf between simulation and life, the graft of artificial intelligence reveals itself as fundamentally hollow.

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding. Who determined its measurements—surely you know!

Or who stretched the line upon it?

On what were its bases sunk, or who laid its cornerstone, when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

– Book of Job 38:4-7

And yet, seduced by the sheer performance of these systems, we cede them an epistemic authority. We begin to accept their outputs as truth, even

as we tenuously grasp how those outputs come about. The danger is as insidious as it is invisible: a creeping nihilism behind our technocratic rationality. We have pursued a pure will-to-truth algorithmic form—only to summon a new kind of will-to-nothingness.

The epistemic chasm deepens when we consider the AI’s relationship with justification. To know is not simply to generate patterns but to provide reasons—to embed truth within a framework of intelligibility. But does AI carry any epistemic burden? It produces without inquiry, declares without reflection, and when it errs, it does not revise its assumptions; it merely recalibrates weights and probabilities. It lacks what Hannah Arendt called the vita contemplativa—the activity of deep reflection that sustains meaningful knowledge. For Arendt, this reflective life—thinking, willing, and judging—is what gives human understanding its moral and epistemic depth. In the absence of this capacity, it does not merely replicate human knowledge but hollows it out. The result is not even intelligence, but an engine of epistemic erosion—a system that supplies answers with no

accountability, declarations with no justification, and conclusions with no possibility of refutation.

The epistemic failure of AI is not an isolated error—it metastasizes. When knowledge itself becomes indistinguishable from the tempest, the foundation of deliberative governance dissolves. Just as Socrates feared the decay of truth into sophistry, AI governance does not just misrepresent reality; it erodes the conditions under which reality can be known at all. In the absence of an epistemic framework that demands justification, authority shifts from those who reason to those who merely compute. Decisions become procedural rather than principled, enacted rather than explained. And what cannot be explained cannot be challenged.

Democratic governance relies on a circulation of reasongiving, on deliberation and shared understanding. What happens when authority shifts from those who justify their reasoning to those who need to justify nothing; when decisions are handed down without recourse, leaving the public unable to interrogate, contest, or appeal the dictates of an opaque system; when

decisions emerge from the dark opacity of a machine mind that offers no reasons at all, only outputs? The political failure of AI is not merely a question of policy but of legitimacy. When algorithms dictate governance—determining who receives benefits, who is flagged as a threat to the system, or what narratives dominate discourse—we are not witnessing benign inefficiency alone. We are witnessing the gross erosion of deliberative authority itself. The legitimacy of governance has always rested on a fragile compact: the right to rule is justified through reason-giving, through the ability to explain and be questioned. AI governance offers no such thing. No deliberation, no negotiation— only the cold, calculated finality of machine-generated edicts.

This is not merely undemocratic; it is postpolitical. The philosopher John Danaher describes this as alogracy—rule by algorithm, in which power ceases to be exercised by human agents and becomes embedded in a system too mired in its own complexity to even be challenged. The citizen is no longer a participant in governance but a data point in a model too vast to question. Decisions are rendered opaque,

outcomes feel arbitrary, and appeals are impossible. The rule by Nobody that Arendt feared—this concept where intricate systems are so entrenched in bureaucracy that all agents are deprived of political freedom—has now been encoded in machine logic. If the epistemic failure of AI is a crisis of meaning, its ethical failure is a crisis of agency. In allowing AI to make moral decisions, we do not augment our ethical structures—we erode them. The banality of evil, as Arendt described it, was not the work of villains but of individuals who ceased to think, who surrendered judgment to bureaucratic machinery. In AI, this phenomenon is perfected: the ultimate functionary, executing commands without question, amplifying injustice without intent. AI does not deliberate; it optimizes. It does not consider the human cost of its actions; it calculates efficiencies. And it does so with the ruthless innocence of a system that neither knows nor cares.

The ethical vacuum this creates is profound. Decisions that once required moral reflection—who receives care, who is deemed a threat, who is granted a voice—are now adjudicated by statistical

models. An AI policing system flags a suspect not because it understands crime, but because historical data suggests certain demographics are more likely to offend. A sentencing algorithm recommends harsher penalties for certain groups not because of justice, but because of statistical correlation. The injustice is no longer intentional; it is automated. Responsibility is no longer assumed; it is dissolved.

True intelligence must not be grafted but woven—a thread of thought interlaced with the world, taut against the weight of human judgment. Intelligence must be a thread in a labyrinth, not a blind Vergil. Ariadne’s thread led Theseus safely through the twisting corridors of the Minotaur’s maze, not by dictating his path, but by ensuring he could find his way back—back to orientation, to judgment, to the self. AI as it stands is no such thread; it is a labyrinth itself, a structure of infinite pathways with no center, no return, no guiding hand. It does not illuminate; it obscures. It does not guide; it misleads. We have built a mechanism that moves ceaselessly forward but never towards wisdom or eudaimonia—only deeper, still, into the maze of its own

recursive logic. And now, we must decide: do we continue wandering, or do we weave our way out?

The specter that currently stalks us—the image of an allknowing AI that in fact knows nothing—need not be our fate. We stand at a crossroads. Down one path, we continue as we are, plastering ever more “intelligence” onto systems that neither understand nor question what they assert. If all we seek is efficiency, then we will continue down the path of algorithmic nihilism, where truth is indistinguishable from lies, and governance is indistinguishable from control. This path leads to a hollow world where human judgment atrophies, decisions are made without meaning, and we bask in the glow of an artificial oracle even as its supposed wisdom turns to ash in our mouths. Down the other path lies the difficult, perhaps perilous work of weaving a new relationship between mind and machine. This path demands we confront our own hubris and imbue our creations with the collective humility our systems and institutions have long neglected. Imagine an AI that is not an oracle at all, but something more like a mirror intertwined with our own

insight—a reflective partner that reminds us of the limits of knowledge even as it expands our capabilities towards eudaimonia. Its task is not to know with us but to provoke a return—to reflect our questions, our flaws, our urgency—so that we do not lose sight of source.

If intelligence is to endure, it must not be outsourced but reflected—structured, not as an oracle to obey, but as a recursive mirror that returns us to the site of judgment. The task is not to perfect artificial minds but to ensure their very incompleteness confronts us with our own moral exposure. An AI system worthy of use would not claim authority but disavow it—forcing us to reckon with what we have

offloaded, deferred, disowned. This would not replace the act of knowing; it would unsettle it, refract it, echo it back. Not a knower, but a prod that compels return. If we are to integrate intelligence into the fabric of institutions, it must be woven in such a way that it does not close the question but recursively opens it—so that the weight of meaning falls, again and again, where it belongs: on us.

Yongjae Kim Phenomenolog y Lyric Documenta r y

o f a Subterranean

Ed. Shrina Dong

Between 1938 and 1941, Walker Evans, a Missouriborn photographer who spent most of the 1930s in New York City to document post-Depression America, sought to join a hundredyear-old mission. It was a mission that the invention of the camera in 1839 spelled out for photographers around the world: to chronicle their own time, leaving precise visual recordings of the world for history to remember—a revolutionary task that no painting or writing could achieve for the last thousands of years.

With a 35mm Contax camera hidden under his thick winter coat, Evans would have the lens of his camera poke out between the two buttons of his coat and a shutter release drop down his sleeve, taking photographs of his surroundings in the New York City Subway. To prevent his subjects from composing themselves and altering their expressions, Evans kept his camera hidden in the chaos and darkness of the subway. He did not raise the camera to his eye to look through its viewfinder, nor did he adjust its focus or exposure or use a flash. As Evans left the train car, his Contax would be filled with surreptitious portraits of his fellow

passengers. In his 1938 photobook Many are Called, Evans remarked, “The guard is down and the mask is off [...] Even more than in lone bedrooms (where there are mirrors), people’s faces are in naked repose down in the subway.”

Situated beneath an iconic American city celebrated for its diversity and promise of opportunity, the New York City Subway, as seen through Evans’ lens, emerges as a microcosm of the vast metropolis. It makes unevenness even, as individuals from all walks of life, lost in each of their thoughts, sit side by side in a setting just as frantic and unruly as the streets above.

In a 1964 lecture at Yale University, Evans described his own photographic style as “Lyric Documentary.” On the one hand, Evans’ photographs rely on a detachment from nuance and awareness, driven entirely by chance and intuition. His works seem to capture a recording of reality in its naked, undistorted state, through the eyes of a photographer who happened to be present in the same space as those who sat in a train car in New York City on one random day in the late 1930s.

On the other hand, Evans’ photographs display an intention to transform the mundane and impersonal reality of the subway into images that open up our experience to the sensuality, emotions, and stories of individual passengers. Each of Evans’ works presents a unique argumentative perspective in itself; a blind accordionist performs before an indifferent audience in one photograph, two women stare into Evans’ eye-level (as if the camouflage of his camera proved unsuccessful) in another. Laughter blooms within an inaudible conversation between two middle-aged women, while all murmurs seem to muffle before men who sit side-by-side in exhaustion—a charm they have broken for a slumbering child. While bare and unguard-

ed, unposed and untold, each work seems to do much more than simply document a fact; it silently talks to its audience, summoning their interpretation of the richer texture within.

Undistorted documentation and intentional “lyric” interpretation of reality both coexist and clash. Susan Sontag writes in her 2003 work Regarding the Pain of Others that the photographic image “cannot be simply a transparency of something that happened.” For Sontag, the photographic image is always the image that someone chose, for “to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude.” Every photographic image is the result of a choice, a decision about what to show and what to leave out. Framing, in this sense, is an act not

only of aesthetic composition but of epistemic limitation; it reflects the image-maker’s intentions that underlie each point of view, restricting how much the image can serve as an unmarked indexical link to the past. This is why, Sontag suggests, those who deal with the art of photography and those who view photographs must “finesse the question of the subjectivity of the image-maker,” all the while considering it “as a memento of the vanished past and the dear departed.” For her, there must be a constant recognition of the photographer’s selective vision—what it reveals or conceals about the unframed reality beyond the camera.

Sontag’s views on the role of photographic art could be explained in tandem with French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s 1945 work Phenomenology of Perception. Merleau-Ponty rejects the empiricist understanding of sensation—of treating sensation as determinate atoms rather than as meaningful wholes. Instead, he suggests the gestalt approach, which asserts that even the most “elementary event is already invested with meaning.” For everything is already a whole, embedded with meaning. Sensation can be better explained by understanding

ambiguities, indeterminacies, and contextual relations that exist as pre-structured, intentional perceptual states in each datum.

Moreover, Merleau-Ponty introduces the concept of “motivation” to describe the way one perceptual phenomenon leads to another. He describes his phenomenological notion of motivation as “one phenomenon releasing another, not by means of some objective efficient cause, like those which link together natural events, but by the meaning which it holds out.” For Merleau-Ponty, empiricism in the traditional sense—by focusing on efficient causes alone—denies any meaningful configuration to the perceived as such and treats all values and meanings as projections. So, for example, seeing a shadow motivates the perception of a hidden figure—not because the shadow causes it or logically implies it, but because it invites or calls forth that interpretation within the flow of experience. To focus exclusively on efficient causes is to lose sight of this subtle, meaning-guided nature of sense perception, which is central to how we actually encounter the world. Therefore, he writes that sensing is a “living communication with the world that makes

it present to us as the familiar place of our life,” and therefore the “fundamental philosophical act” would be to “return to the lived world beneath the objective world,” that is, to place oneself in the position of constantly searching for meaning in every sense perception.

While Merleau-Ponty’s argument for a phenomenological interpretation of the contingent world seems rather anti-empiricist, it does not offer a diametrical divergence between empiricism and phenomenology. For Merleau-Ponty, a solely empiricist interpretation cannot fully account for the indeterminacies and ambiguities of our sensation of reality, but the phenomenological method will not be of any use unless there is some pre-predicative sensation for it to feed on. Therefore, photography seems to be a middle ground between artistry and documentation—which conjoins to form a “lyric documentary” that Evans describes as the central intent of his work.

Given the contingent world that awaits our interpretation and interaction, the photographer’s role, in accordance with Sontag’s and Merleau-Ponty’s philosophies, is to employ a phenomenological approach to understand what one is able

to consciously extract from a sensible object, a surrounding, or a historical event. Then, the photographer ought to present these in a visual manner, which offers a self-referential reflection of the “existential structure” of the contingent world as is.

Evans’ photographic vision inside the dimly lit metallic tunnels of New York City was one such attempt; it remains both a truthful transcription of presence now turned absence and an interpretation of that bygone reality—a feat that continues to inspire photographers in exploration of their own subway tracks, cityscapes, and documentaries to lyricize.

Gentrification

as a Skin Graft: An Ethical Failure Masquerading as a Cure

Christopher Smith

Ed. Telvia Perez, Joseph Said Kwaik

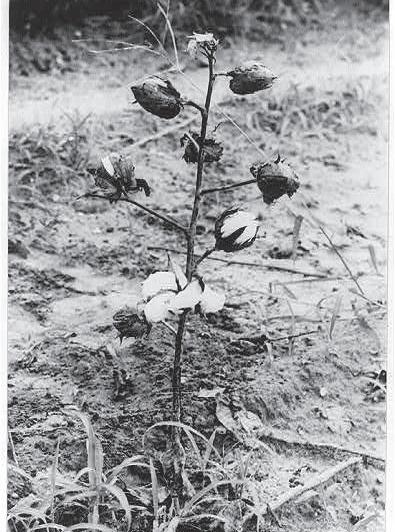

In my hometown of Fayetteville, West Virginia, after organizations started incentivizing migration to the New River Gorge by providing direct payouts to remote workers, property values have increased, new businesses have been thriving, and to new residents, the town has been “beautified.” The well-off out-of-staters that have relocated to my town have, on the whole, succeeded in their goal of improving its economic base—they fix up old buildings, construct new housing units, and create jobs for locals. They have integrated into the flesh of our community, much like a graft meant to repair damage to the skin. However, this graft does not repair. Instead, it corrupts the healthy, although damaged, skin. The people affected by this grafting are not cured of their afflictions; rather, they are displaced, alienated, and plunged further into economic despair. In order to increase the capabilities and well-being of local populations, gentrification must be disincentivized.

What are capabilities, and how do they relate to gentrification?

Martha Nussbaum, an ethical philosopher, measures human well-being and quality of life using the “capabilities approach,” focusing on

people’s capabilities of life, bodily health and integrity, emotions, affiliation, practical reason, play, and control over one’s environment. These capabilities are core aspects of quality of life; they give people more agency and freedom in their daily lives rather than worry and limitation. Although people living in communities going through gentrification still have many of these capabilities, the capabilities that they retain are extremely limited. Control over one’s environment is the most limited during gentrification; wealthier people come to an impoverished area and revitalize the community: there are more businesses, more income in the town, and property values rise. Despite these seemingly positive aspects of gentrification, the locals have been stripped of their control of their environment. Rent prices go up, making it extremely difficult for renters to make ends meet without moving to another town with a lower cost of living. In Fayetteville’s case, buildings that were publicly owned have been privatized, transferring the power of preserving the physical constitution, integrity, and legacy of these historical buildings over to people

who have no sentimental connections to them. Rather than the public deciding what to do with their buildings, the control of the environment is handed over to outsiders trying to graft themselves into the locals’ environment.

Play, or the capability of enjoyment, is also extremely limited during gentrification. Consider the millennial burger joint: a common trope of gentrification that has become popularized in meme culture today. “Handhelds” are all $15, fries are an upcharge, and craft beer flows like a river. When gentrification comes, prices rise, and fun activities that bring pleasure are commodified to the point where they become unattainable for the average local in a gentrified area. I

felt this shift in Fayetteville first hand. My first job, a dishwashing position at a local breakfast spot, came just after my area became a hotspot for out-of-staters to move into. Although the cooks were nice and fed me for free, it would have taken me two to three hours of work to afford a baseline menu item. A full day’s work would be needed if I wanted to go on a date. A unique example of the lack of recreation, or play, for locals of West Virginia comes in the form of “Ascend WV,” a program founded by Brad Smith, a near billionaire, and supported by the West Virginia State Government. Ascend pays outof-state remote workers $12,000 cash, provides them with free outdoor recreation equipment, and creates co-working spaces

for remote workers from other states to come to areas in West Virginia, including my own. While these out-of-staters are rewarded for living in my area and enjoying our natural wonders for free, locals must pay more to live where they are from due to rising property values and pay exorbitant amounts for recreational activities. The inability to control their environment or have any time for play makes life dreary for locals; their entire lives revolve around making rent payments and putting food on the table, while the graft of gentrification enjoys natural beauty and nights out without the pressures of staying afloat.

Another capability that is infringed upon during gentrification is affiliation. Before gentrification begins, there is a strong sense of community despite shared economic hardship. Although bred by adversity, this sense fosters comfortability and expression within the community. When the graft of gentrification begins and prices begin to rise, people within the community are often forced out, seeking accommodation in neighboring areas. Even though locals may have a good life, even a better life, elsewhere, there is still the issue that

they were displaced from the community they called their own. In my neighborhood, I have seen local businesses close, most houses on my street be turned into Airbnbs, and friends move away from home due to the high cost of living. These people and institutions that were once affiliated and integrated within the community have dispersed due to the grafting of out-of-staters onto the skin of our town.

Why is gentrification bad in this sense?

It is true that homeowners have greatly benefited from the appreciation of their assets. It is also true that many people living in gentrified areas have been given even better lives by moving there—the towns they inhabit are undeniably prettier, more developed, and bustling. The capabilities of the gentrifying population are increased and protected, making life better for them. On paper, GDP goes up, and poverty goes down. It can be argued that, under a utilitarian sense of good, the positives of gentrification indeed outweigh the negatives. However, a decrease in poverty within the city limits does not correlate to the uplifting of the impoverished—they have

instead been removed from the equation and have been displaced. The town may look prettier, the infrastructure may be sturdier, and the population may be richer, but it is not a cure to the throes of poverty. Although gentrification seems to heal the community, it simply disperses the people affected with no real solution for how to make life better for them. So many people from my town have moved out; small business owners have been displaced by those with more capital, rent prices have driven out people who were once staples of my daily walks around town to surrounding areas, and most homeowners on my block have turned their old houses into Airbnbs and moved elsewhere. Even though many of these people have found better opportunities elsewhere, they have lost the sense of community that they had grown up feeling. Although they may be economically better off, money cannot buy the feeling they once had in a community of people they grew up with.

How does gentrification reduce human value?

Gentrification prioritizes property values and beautification over the well-

being of residents. In the Estranged Labor section of his Economic and Philosophical Landscapes, Karl Marx writes, “The devaluation of the world of men is in direct proportion to the increasing value of the world of things.” Although gentrification, at first glance, seems like a way to a better life for those within a community, the main point of gentrification is not to improve the wellbeing of current residents but to increase the value of property and cash flow within a previously undervalued area. As profit incentives and beautification become more present within a community, there is a devaluation of the working-class people that inhabit it. To the gentrifiers, maximizing rental income often takes precedence over addressing the housing needs of long-term, lower-income locals. Although profit-driven ventures increase the monetary value of property, they also deface the historical and cultural significance of places once adored by the community. Unlike a fish skin graft, which may look unappealing but actually heals the affected skin, gentrification cuts off all the affected skin of the community and replaces it with another community’s skin that is not cohesive. Rather

than heal the community by giving a lifeline to the disenfranchised, the process of gentrification throws human value to the side, prioritizing outward appearance instead of community.

In his later work, The German Ideology, Marx also says, “For the proletarians … the condition of their existence, labor, and with it all the conditions of existence governing modern society, have become something accidental, something over which they, as separate individuals, have no control.” Agency is an important aspect of human value and capability, but when the grafting of the upper class onto communities starts, the only agency that matters is that of the rich. Only the gentrifiers can truly decide what they want to achieve, and workingclass people must make do— they have almost no agency as to where they want to live, how they want to spend their free time, and how they want to spend money because of the rising cost of living under gentrification. Despite locals being poor, they had much more control over their lives before gentrification began. After the graft began, material conditions being bettered for the wealthy transplants have

limited the control over life that the locals had.

Should society intervene to stop this grafting?

Depending upon your worldview, this process of grafting can be either good or bad. If you believe that a capitalist and individualist morality is preferable, you may be more inclined to think that economic freedom outweighs the well-being of others. If you believe in a more communalist morality, then you are probably inclined to believe that quality of life outweighs economic freedom. Despite these differences, anyone with any set of morals can see that gentrification devalues humanity in favor of the economy. Although the United States is an especially individualist nation, much of our legal precedent and morality comes from J.S. Mill’s “harm principle.” In On Liberty, Mill supports extensive individual liberty, with the caveat that any encroachment upon someone else’s liberty should be punished. , He writes, “Acts injurious to others require a totally different treatment. Encroachment on their rights … unfair or ungenerous use of advantages over [others] …—these are fit

objects of moral reprobation.” Consider where your rights end. A racist has every legal right to believe what they want, but do they have the right to physically harm a minority for no reason? Do landlords have the right to evict tenants at will if the tenant pays on time? Is raising housing prices and the cost of living generous? Is a historical town property being auctioned to the highest bidder, without the general consent of the population, generous? Is the economically forced displacement of working-class people from their homes not injurious? The answer is no— the rights these parties possess end when they encroach upon the rights of others. This is the harm principle in action. By following Mill’s harm principle, it is evident that, at the very least, gentrification is indeed a

fit object of moral reprobation. In a society that considers things like petty larceny fit for moral reprobation, should we not consider the theft of livelihood and community in the same way?

How should society intervene?

Mill says, “[S]ociety, as the protector of all its members, must retaliate against [the offender].” Under this very principle, it is obvious that society must intervene. Before we discuss interventions for addressing the harm that gentrifiers, or the “grafting class,” enact on locals, it is essential to note that the members of “the grafting class” are not dehumanized simply because of their privilege or the harm they have caused. All humans

are worthy of capability and agency and should not be seen as lesser. However, it should be noted that slightly limiting capabilities for those who are privileged is not out of the question as an interventional measure. Consider Nussbaum’s capability to control one’s environment: does the grafting class not already have such a capability? Despite the higher cost of living within cities and suburbs, the newly incoming wealthy people have a relatively high capability of control to meet these prices compared to a working-class individual who may have less financial power. With an already increased level of capability, must the grafting class take more from those whose capabilities are limited? Even if economic freedom takes precedence, what of the economic freedom of those affected by gentrification? In order to preserve the capabilities of the working class, the capabilities of the grafting class must be limited but not taken away. Instead of incentivizing already privileged people to gentrify by way of cash payouts, low property value, and vacant land, there must be a disincentive. For example, instead of paying people to move into lowincome areas, perhaps require

that the grafting class pay more taxes to move into such places. This way, instead of money going into the pockets of the already privileged, it will go toward social programs for the poor and contribute to the betterment of infrastructure that will not directly raise the cost of living. The grafting class, in this sense, still has the capability of control, but to a lesser extent, as not to harm those of a lower economic class.

The Transparent Connection: An Existentialist View of Identity

Ryan Marienthal

Ed. Jayin Simh, Telvia Perez

Since the early 1960s Bob Dylan has felt misunderstood by his fans, who have wanted nothing more than for him to share their grand revolutionary spirit and be the genius songwriter speaking the soul of their generation into music. However, this is nearly the opposite of who he feels he is. His fans began to resent his rejection of this identity, which has evolved into a conflict that continues to this day. In a 2004 interview aired on 60 minutes, Dylan shares, “It was like being in an Edgar Allan Poe story, you know you’re just not that person everybody thinks you are, although they call you that all the time. You’re the prophet, you’re the savior. I never wanted to be a prophet or savior, Elvis maybe … .” Those that believed in this abstract identity they had formed of Dylan as a prophet and savior were doomed to be disappointed by the reality of who he is, and Dylan himself had to bear the weight of being misunderstood. An abstract identity is harmful to believe in because it denies the truth of who one is (i.e. their emotional or physical predispositions), and does not describe the physical expression of itself through actions and feelings. It would not have been possible for Dylan to avoid letting his fans down because the abstract identity of ‘prophet’ was at odds with how he felt, and thus is un-

able to be expressed in a manner that would be satisfying for his fans. This discontinuity between an abstract identity and one’s true self is not only found when we interpret others, as with fans interpreting celebrities, but also when trying to understand ourselves.

In the same way that we may find the reality of a celebrity dissatisfying, we may find the experience of being our true self dissatisfying. Attempting to overcome this insecurity by grafting an abstract identity over our true self—one that is usually idealized and free from things like discontentment, failure, or meaninglessness—will result in a disconnection with the identity that we desire and feelings such as self-hatred and purposelessness. The connection between desiring an abstract identity and these struggles, such as self-hatred, are described in Søren Kierkegaard’s Sickness unto Death, specifically the concept of “willing to be oneself”.

Kirkegaard’s Sickness unto Death asserts that our desire to embody an abstract identity results in an inevitable discontinuity between who we are and who we desire to be. In order to overcome this discontinuity, the identity must encompass the unchangeable parts of our self and be expressible in our actions.

In Sickness unto Death,

Kierkegaard describes the ‘self’ as “a relation that relates itself to itself”, or in other words, a force that continuously reflects on how connected our ‘self’/ identity is with the expression of that identity in the world (our embodied self). Our embodied self must either identify entirely with the ‘self’, or have complete dissonance with it (which Kierkegaard refers to as Despair). Despair for Kierkegaard is “the expression for the inability of the self to arrive at or be in equilibrium, and rest by itself”. It is an internal conflict that arises when our ‘self’ is not synonymous with who we feel we are. The section of Sickness unto Death “Will to be Oneself: Defiance” examines how the desire to be oneself originates, and the conflict that arises from it.