Gadfly

Letter from the Editors

Beyond Geschichte and Itihāsa: Theorizing History from the Margins in Colonial India

Mrinalini Sisodia Wadhwa

Buccolia

Ashley Blanche Waller

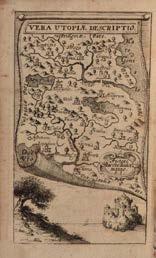

Concrete Horizons: Against Utopian Myopia with Bernard Harcourt

Oscar Luckett, ed. William Freedman

Writing for One: Reframing the Author-Reader

Editors-in-Chief

Chase Alexander Bush-McLaughlin & Aiden Frederick Sagerman

Chief Managing & Design Editor

Skylar Wu

Chief Article Editor

Joanne Park

Chief Interview Editor

Soham Mehta

Chief Column Editors

Jalsa Drinkard & Milène Klein

Discussion & Events Coordinator

Bellajeet Sahota

Social Media Manager

Ashley Blanche Waller

Copy Editors

Maya Platek, Danielle Zheng

Design Editor

Axel Icazbalceta

Article Editors

Rose Clubok, Nora Estrada, Jeongin Kim, Amelia Landis, Ashling Lee, Sanaaya Rao, Kyle Y. Rodstein

Interview Editors

Chimelu Ani, Henry Astor, Wynona Barua, Gabriella “Elle”

Calabia, Haniya Cheema, Qingyuan Deng, William Freedman, Wenni Iben, Lily Kwak, Oscar Luckett, Kylie Morrison, Manavi Sinha

Column Editors

Lucia Yinuo Cao, Hermella Mesfin

Getachew, Eden Milligan, Xavier Styles, Judy Tao

Columnists

Aharon Dardik, Axel Icazbalceta, Ashley Blanche Waller

Editors Emeritus

Cecilia Bell, Emilie Biggs, Alice McCrum, Saikeerthi Rachavelpula, Jonathan Tanaka

Relationship

Jonas Rosenthal

Thoughts on Latin American Thinking

Susana Crane Ruge

Art for Corpses, Art for the People: Interview with SLUTO

Wenni Iben, ed. Soham Mehta

The Panacea of Pan-Africanism: Discussing Decolonization with Lwazi Lushaba and Ziyana

Lategan

Chimelu Ani, ed. Oscar Luckett

Gadfly is, in the grand scheme of things, a marginal publication. We are a student magazine, and many of our writers have never seen their work in print before. Nothing we produce is widely sold—we don’t sell anything at all. And we publish writing on subjects and themes that are, while in our view contemporary, hardly trendy. Philosophy is not widely read outside of colleges and universities. Neither are philosophy magazines.

“There is too much to read,” notes Jonas Rosenthal in his article “Writing For One: Reframing the AuthorReader Relationship.” Well said. With all-time greats, classics, bestsellers and notables “of the year” peering down at you from on high, why read anything written on a marginal subject, by a marginal author, published by a marginal magazine? Writing in the face of the question of our own marginality—or lack thereof, given the nature of the platform we write from and the university which supports it—and many other (thankfully less maudlin) questions, we have decided to dedicate this issue of Gadfly to margins. The result has been an issue which, though profoundly and delightfully marginal in its tenor, brings together a number of uncommonly defiant, stirring and sometimes radical efforts to do justice to the scope of the margins, from the merely peripheral to the

systematically excluded.

Issues of disciplinary, material and historical

Issue 09. Mrinalini Sisodia Wadhwa begins the issue with an examination of how Indian anticolonial thinkers such as B.R. Ambedkar and Mahadevi Varma engaged with the philosophy of history to achieve emancipation from both colonial and religious oppression. In the middle of the issue, we find Susana Crane Ruge’s “Thoughts on Latin American Thinking,” which questions the xenophobia and elitism endemic to philosophy as it is done today by drawing from several rarely-treated contemporary Latin American thinkers. Finally, Chimelu Ani’s interview with Lwazi Lushaba and Ziyana

Lategan, “The Panacea of Pan-Africanism,” closes the issue with a meditation on decolonization which challenges modernity and the marginalization of what Lushaba terms “African modes of cognizing.” In arranging the issue as such, we hope to highlight the multiplicity of inquiries— from regions as distant as India, Latin America, and

South Africa, and in modes as disparate as academic argumentation, exposition, and conversation—which can arise to combat colonial mechanisms of intellectual, political, and economic marginalization, and the multiplicity of solutions which arise from these inquiries.

This is not to say, of course, that our exploration of margins is limited to the colonial construction of knowledge. Ashley Blanche Waller’s chilling story “Buccolia” brings to life— and puts to sleep—our obsession with the fat at the margins of our faces. In “Art for Corpses, Art for the People,” Wenni Iben speaks to graffiti artist SLUTO about his new book, “shitty” and political art, and art at the margins of society and urban space. Jonas Rosenthal’s aforementioned inquiry into the reading of marginal texts offers a radical alternative to the readerly paralysis that leaves so few books read, even as more and more books are available to read than ever before. And Oscar Luckett’s interview with

Bernard Harcourt asks us to enter the realm of utopian thought, housed as it is at the margins of academic philosophy, constantly resisting the boundaries of possibility and imagination. This issue’s contributors explore margins as physical objects and spaces, as social realities, and as purely intellectual constructs. We only regret the absence of any real, visible, drawn marginalia in its pages— the sort you might see in a disintegrating medieval bestiary, of a rabbit with a sword or a twenty-legged spider. We suppose that’s what the reader is for.

The publication of this issue marks our—that is to say, Chase and Aiden’s—last act as editors-in-chief of Gadfly. We started at this magazine in 2020, when our meetings were held on Zoom, and our copies of the singular annual print issue were delivered to our 25-person board by mail. The two of us first met as a writer-editor pair in a backyard in San Francisco, where Aiden resisted nearly all of Chase’s edits. Of

course, we now work in perfect harmony.

Gadfly, too, has come a long way since 2020. We have expanded to include a columns division, now publish a print issue every semester, and hold our weekly discussions in person in Philosophy 716. On top of our usual fare of essays and interviews with philosophers, we have now published short stories, poems, visual art, and musical compositions— alongside theological tracts, interviews with scientists, and works of historical inquiry. Most importantly, Gadfly now feels like a real community where members grow to care about one another in the process of editing, writing, discussing, and doing philosophy. The

two of us are immensely proud of the role we’ve played in the growth of this magazine, and especially of Issue 09. But we’re ready to retire our fly-wings, so to speak, and excited to see what the next board has in store.

We thank Columbia University’s Department of Philosophy and the Arts Initiative for the opportunity to continue to meet and produce two issues of Gadfly each year. We thank Gadfly’s growing community for breathing life, humor and sometimes baked goods into our studies. Finally, we thank our perennially wonderful contributors and board, without which Gadfly would be, not marginal, but impossible.

“Is there any historical evidence [for] what you have called soul-force or truthforce?” asks the Reader in the Indian anticolonialist M.K. Gandhi’s 1909 Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Gandhi originally wrote the text while en route from London to South Africa in his native Gujarati, framed as a series of dialogues between a Reader (representing the perspective of extremists in the Indian freedom struggle who advocated for violent resistance to colonial rule) and an Editor (representing Gandhi’s perspective). The text was soon translated into English and French— banned in 1910 by colonial authorities for sedition—and offers an early articulation of Gandhian political theory, arguing for satyāgraha [soul force] as the means to secure Indian freedom from British rule.

In this context, the Reader’s search for “historic

precedent” reveals Gandhi’s underlying historiographical critique. In shifting the domain of India’s freedom struggle from the material to the spiritual, rejecting both moderate nationalists who sought to “petition” for autonomy within the British Empire and extremists advocating for direct violence, Gandhi seeks to engender a paradigm shift.1 To do so, he must turn to the past as an arbiter of the viability of his “soul force,” and must thereby grapple with the manner in which India had been marginalized by Western disciplinary history.

Nineteenth-century Western intellectuals had written India out of modern history, casting Indians as “backward” on a chronology of stadial progress and thereby justifying colonization. For Gandhi to argue for the viability of satyāgraha, he must counter this philosophy of history with a different means of

relating to the past that can grant the colonized subject agency. “It is necessary to know what history means,” replies his Editor, positing as an alternative the concept of itihāsa. This philosophy, drawn from the Sanskrit intellectual tradition, denies the importance of human subjectivity and material “progress”—contra Western history-writing—turning to the past as a continuous entity with no definite beginning or end that offers glimpses of spiritual Truth.

Two questions emerge from this encounter between stadial progress and itihāsa, which frame my attempt to map theories of history from the margins of colonial India. Firstly, we might ask why Gandhi’s invocation of itihāsa authorizes his project of pursuing swarāj [selfrule] through “soul force.” How does itihāsa counter the prevailing stadial view of history—whereby humanity progresses through

material conflict towards a single goal, realized in the European nationstate—that marginalized Indians and upheld colonization? Secondly, we might grapple with the implications of using itihāsa to embrace India’s purported ‘changelessness’ for societal groups, such as Dalits and women, who were marginalized by orthodox Hinduism and thus faced the double-bind of colonial and religious oppression. How did these groups engage with these two philosophies of history to posit visions of social reform?2

In what follows, I first discuss the prevailing stadial philosophy of history, famously captured by G.W.F. Hegel’s notion of Geschichte in Introduction to the Philosophy of History and deployed in service of liberal imperialism in works such as John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. It is in this form that Gandhi’s class of

2 I use the term Dalit in this paper, but want to acknowledge the longer, contested “politics of naming” during and before the early twentieth century. This community was referred to as acuta [not touched; Untouchable] in nineteenth-century sources, with series of attempts at re-naming during the twentieth-century: Gandhi, using harijan [child of God], Ambedkar later coining the term Dalit, but frequently reverting to terminology such as “depressed classes” or “scheduled castes,” the language used in the Indian Constitution. For further discussion, see Gopal Guru’s 1998 “The Politics of Naming.”

nationalists encountered Western disciplinary history and became highly critical of its role in denying Indian sovereignty; thus, I subsequently turn to Gandhi’s invocation of itihāsa in Hind Swaraj. Having established these two philosophies of history— Geschichte and itihāsa—I take up the work of Dalit scholar B.R. Ambedkar and feminist writer Mahadevi Varma,two of Gandhi’s contemporaries, to map how these philosophies could be recast by reformers at the margins of colonial Indian society.3 Through this analysis, I argue that the dissonances between

these two philosophies pave the way for an important philosophical project: a search for emancipatory potential in India’s relationship with its past, which took on crucial political dimensions in the final decades of colonial rule.

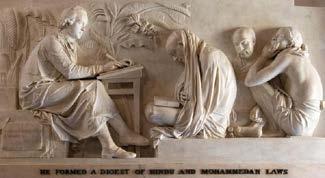

II. “India has no history”: Geschichte and India’s Marginalization from the Historical Canon

Of India, Hegel famously wrote in 1840 that it is “striking that this land… has no history.” This statement would have profound implications for colonial historiography:

India was “spiritual,” literary, fantastical, even, but was also eternally unchanging, and was thus relegated to the margins of disciplinary history. In this section, in an effort to contextualize the subjectposition of intellectuals such as Gandhi, I want to sketch how this marginalization took place: the intellectualhistorical contexts for Hegel’s claims, and the manner in which they were deployed in service of liberal imperialism.

We can situate Hegel’s

treatment of India in two nineteenth-century intellectual-historical contexts. The first context is the Orientalist construction of India as a fantastical, mythological, “spiritual” land, creating binaries between rational, selfpossessing European subjects and their effeminate, irrational, dispossessed Indian Other. This was profoundly shaped by European philologers’ “discovery” of the ancient Indian language of Sanskrit in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and circulation of a range of Sanskrit literary and theological texts in translation.4 The second context is the intellectual legacy of the mainstream Enlightenment and French Revolution of 1789, reshaping Western Europe’s engagement with its past.

Enlightenment universalism inspired efforts to draw all

4 Let me add a small caveat: while Orientalist views on India were be fairly entrenched by the time Hegel wrote in the mid-nineteenth century, I do not mean to imply here that Orientalist binaries were the only outcome of Europeans’ encounter with India (or with Sanskrit specifically) in the late eighteenth-century. While figures such as William Jones, colonial jurist and Orientalist philologer, might seem to offer a more clear-cut case, the writings of other European Sanskritists—such as Jesuit missionaries in early modern South Asia—do not lend themselves as quickly to an Orientalist paradigm. Further discussion of this casts beyond the scope of this paper (but is indeed the subject of my not-yet-written history thesis).

of humanity onto a single chronology and compare the relative “progress” of different cultures and religions. Moreover, in light of 1789, revolution came to be seen as an act undertaken by human subjects seeking to break from their past rather than a cyclical process that happens to humanity. In turn, Hegel’s notion of history is at once universal in its aspirations and highly exclusive in what it considers to be the object of historical study. There is a sharp distinction between the past as unconscious passage of time—sans human subjectivity and agency—and self-conscious, subjective human accounts of temporality that can only emerge after the formation of civil society and the nation-state. Only the latter is “history,” the former being relegated to the domain of “nature.” India is the example par excellence of “a people [who] may have lived a long life without having arrived at their destination by becoming a state,” that is, a people with a long past but no history. Hegel cites “the great discovery of

Sanskrit, with its connection to European languages,” pioneered by European philologers such as William Jones, Max Müller, and Monier Monier-Williams.

As Thomas Trautmann discusses in Aryans and British India, these scholars saw Sanskrit as the key to finding the original language of humanity, lost since the fall of Babel, and thereby aligning Biblical, Koranic, Greco-Roman, and Puranic [Hindu] time on a single chronology.

Hegel does not dispute these Orientalists’ contention that India has a long past worthy of study, one that might even extend to the far recesses of Biblical time. Yet for him it cannot be the subject of historical study. These “millennia… elapsed… before the writing of history,” for Indians “produced no subjective historical narratives,” their sources lacking the intentionality and directionality—the “clarity of consciousness” moving towards a particular material goal—for history to be realized. In turn, it is telling

that when Hegel does praise the study of the “Orient,” it is when such research is funded by European nation-states and pursued by European scholars, never Indians themselves, and is cast as a study of “literature” or “religion,” never history. We return to perhaps the most powerful statement Hegel makes on India: “everyone who begins to become acquainted with the treasures of Indian literature finds it striking that this land—so rich in the most profound spirituality—has no history.”5

Hegel proceeds to draw India into a liberal philosophy of history, whereby humanity moves in stages towards a single goal: the simultaneous actualization of Geist [Spirit] at individual and collective levels. Here, Enlightenment

universalism and the postrevolutionary view of history as linear rather than cyclical converge, drawing India, China, Greece, Rome, and Western Europe into a single chronology presented through the biological metaphor of maturation. Like the sun, “world history goes from East to West: as Asia is the beginning of world history, so Europe is simply its end.” The “East” is “Asia,” the “Oriental World,” a place with spirituality but no rationality or subjectivity, harkening to Hegel’s view of India having a spiritual past but no “history.” “This is the childhood stage of history,” the earliest point of the chronology. Hegel then moves to Ancient Greece, Rome, and finally, Western Europe, history’s “adolescence,” “manhood,” and “old age,” respectively.

5 It is worth highlighting Hegel’s sources on Indian “literature” and “spirituality,” emerging from his encounter with translations of Sanskrit texts such as Śakuntalā or the Bhagavad Gītā, circulated by European philologers using “native” interlocutors. His interest was shared by his German contemporaries, such as the Romantic poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who published an epigram on Śakuntalā in 1792, and philosopher Alexander von Humboldt, who delivered a series of lectures on the Gītā in 1827. Hegel went on to publish a review of Humboldt’s lectures that extended to a critique of Indian peoples, discussed by Simona Sawhney in The Modernity of Sanskrit (2009). Bernard Cohn’s Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (1996) discusses the unequal relationship between European philologers and their “native” interlocutors—i.e. Hindu brahmins and Muslim maulvis— to translate these theological, political, and literary texts from Sanskrit and Persian into European languages.

Each shift occurs through dialectic—the unity of opposites through sublation—involving immense material and intellectual conflict, hence Hegel’s reference to history as humanity’s “slaughter-bench.” Yet such conflict is essential to move from the “faith, trust, and obedience” of the Orient, to the emergence of “individualities” in Greece, to the “abstract universality” of Rome, to the sublation of the Christian religion to arrive at Spirit, “a higher form of rational thought,” in Western Europe. Two points bear consideration here. Firstly,

Hegel reiterates his naturehistory distinction and maps this onto a matter-idea distinction: Western Europe is the subject of history because of its “maturity,” for while “in nature, old age is weakness,” “the old age of the Spirit is its complex ripeness.” Secondly, of all the preceding stages of Hegel’s chronology—the Orient, Ancient Greece, and Ancient Rome—only the Orient remains, a relic in the modern world. The question becomes, then, how Western Europe is to interact with Oriental peoples, who are behind them in this chronology of progress.

This is brutally resolved by the logic of liberal imperialism, articulated by works such as Mill’s On Liberty. After stating his philosophical project of defending self-cultivation from the “tyranny” of society, Mill adds an important qualification:

This doctrine is meant to apply only to human beings in the maturity of their faculties. We are not speaking of children… For this same reason, we may leave out… those backward states of society in which the race itself may be considered in its nonage. Despotism is a legitimate mode of government in

dealing with barbarians… Liberty… has no application to any state of things anterior to the time when mankind have become capable of being improved by free and equal discussion. Until then, there is nothing for them but implicit obedience to an Akbar or a Charlemagne.

[emphasis added]

Note the parallels between Mill’s claim—which moves seamlessly from eighthcentury French monarch Charlemagne to sixteenthcentury Mughal Emperor Akbar—and Hegel’s chronology. India is as Europe was. It is at once the cradle of civilization

and the site of the colonial civilizing mission because it “has no history,” because it has not changed, stagnating under “Oriental despotism.” Thus, as Hegel described the Orient as the “childhood stage of history,” Mill likens the condition of barbarians to that of children, denying them liberty both in writing, through this treatise, and in practice, through his role in the British East India Company.6

It is through this cruel irony—an acclaimed Western theorist of liberty endorsing the despotism of colonial rule—that Gandhi’s class of nationalists came to develop a deep skepticism of Geschichte. Their access to Hegel and his German philosophical tradition was often mediated by English

and French sources, which were, in turn, mediated by the experience of colonization. As Gandhi highlights in Hind Swaraj, the idea that emulating Europe’s trajectory would allow Indians to progress enough to enjoy liberty had become suspect. “Progress” eluded Indians by design. Conceding that Indians were capable of progress would deny Britain its justification for colonial rule to the detriment of its material prospects— given the profits secured via “drain of wealth”— and its sense of national pride, defined against the backwards colonized subject. 7 As Macaulay’s famous 1835 Minute argued, even the most Westernized Indian, “English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect,” would remain “Indian in blood and color,” relegated to a position of hierarchical inferiority.

Thus, casting beyond nineteenth-century “moderate” Indian nationalists, Gandhi rejects the notion that proximity to Western-ness through an English education will secure Indian freedom. He then indicts the very nature of Western civilization and historical knowledge itself, finding it to be defective at its essence. “[The English] have the habit of writing history; they pretend to study the manners and customs of all people,” he writes early in Hind Swaraj, and “we in our ignorance then fall at their feet.” This charge is levied against intellectuals such as James Mill, father of John Stuart Mill and author of the 1818

History of India which had a central role in advancing the theory of inborn HinduMuslin enmity that Gandhi critiques in this section of Hind Swaraj. Yet when we return to the question Gandhi’s Reader poses later in the text—“is there any historical evidence [for] what you have called soulforce?”—it morphs into a sweeping historiographical critique:

You ask for historical evidence. It is, therefore, necessary to know what history means. The Gujarati equivalent means: “It so happened.” If that is the meaning of history, it is possible to get copious evidence. But, if it means the doings of kings and emperors, there can be no

evidence of soul-force or passive resistance in such history. You cannot expect a silver ore in a tin mine.

Gandhi’s “Gujarati equivalent” is itihāsa, a term derived directly from Sanskrit. Before turning to itihāsa‘s philosophical content, it is worth considering the term’s linguistic features—in contradistinction to Geschichte [history, story], which Hegel traces to its roots to demonstrate how it “combines… objective and… subjective”—if only because of Gandhi’s own attentiveness to the linguistic chasm between Indic and English terms. Itihāsa is formed through the joining of three words: iti [thus], ha [indeed], āsa [it was/existed]: “so (indeed) it happened.” It is linked to satyāgraha, the term Gandhi coined in Hind Swaraj to describe

what has been translated as “soul force” or “passive resistance,” arising from the joining of satya [Truth] and āgraha [grasping on to].8 Satya derives from sat [that which exists], formed of the same verbal root, as [to be/exist], used to obtain āsa. Both terms thus have ontological significance, identifying what exist(ed), Truth, as their object. Far from being speculative or counterfactual, “soul-force” is intimately linked to the past, to the past as itihāsa.

Gandhi makes it clear what itihāsa is not: a record of “the wars of the world,” the material conflict Hegel argued was necessary for dialectical progress.9 Works of itihāsa, including the Mahābhārata and Ramāyaṇa—the very epics Hegel saw as literary, not historical—acquired theological significance

8 While Gandhi used these terms interchangeably in Hind Swaraj, drawing on Western influences such as Thoreau’s writings and the American and British suffragette movements to conceptualize “passive resistance,” he would later distinguish between his satyāgraha as “soul-force” and Western “passive resistance”: the latter “does not necessarily involve complete adherence to truth under every circumstance.” See Gandhi’s “Letter to Someone in Madanpalli” (c. 1919).

9 While Gandhi does not cite Hegel explicitly, one is reminded of the fateful lines of the Philosophy of History—“India has no history” and history as the “slaughter- bench” of humanity—as Gandhi proceeds to cite a “saying among Englishmen that a nation which has no history, that is, no wars, is a happy nation.”

by denying their authors’ temporal contexts. In a process that Sheldon Pollock describes as “Vedicization,” authors erased traces of their subjectivity so that their texts might resemble the authorless Vedas, capturing Truth, universal, eternal, transcendent through the ages, to aid the individual soul on its journey to mokśa [liberation].10

There is no value ascribed to material conflict in an ontological framework that views materiality as māya [delusion] impeding the soul’s liberation via dissolution into God, Truth, that which exists—a belief underlying Gandhi’s rejection of all machinery, even his “body,” to “seek the absolute liberation of the soul.” As philosophies of history, both Geschichte and itihāsa trace progress, but they rely on different understandings of the site

of progress. Hegel draws on the post-revolutionary view of history as a linear path towards progress realized in the material world; Gandhi draws on Hindu beliefs that the soul progresses spiritually towards mokśa while the material world moves cyclically through yugas, four million year cycles, for eternity.11 Geschichte thus records material conflict to mark humanity’s stadial progress, precisely what itihāsa transcends to guide the soul’s spiritual progress.

Introducing itihāsa thus allows Gandhi to recast Hegel’s belief in India’s changelessness as an indication not of “backwardness” but of “strength.” Europe “learn[s]… from… Greece or Rome, which no longer exist in their former glory,” while “India remains immovable,” declares Gandhi. He has

10 See Pollock’s discussion of the “denial” of history (in the Western disciplinary sense) in his “Mīmāṃsā and the Problem of History in Traditional India” (1989).

11 Perhaps this might be closer to the premodern European view of history as cyclical. Gandhi makes allusions to the yugas—over four million year long cycles, during which the world ascends and then descends through the same four stages, in Hindu theology—at a few points of Hind Swaraj, including his reference to British colonialism as India’s “Black Age” [kalyuga, the lowest point in the cycle], to satyāgraha as drawing from a “higher” stage, for which “India is not [yet] ready.”

seized upon precisely the anomy we identified earlier: of all the preceding stages of Hegel’s chronology, only the so-called Orient still exists. “It is a charge abasing India that her people are so uncivilized, ignorant, and stolid that it is not possible to induce them to adopt any changes,” a view we might trace to imperialists such as James Mill. This is a misreading of India’s ‘changelessness,’ a “charge… against our merit.” “What we have tested and found true on the anvil of experience, we dare not change,” Gandhi writes, invoking itihāsa‘s emphasis on preserving Truth in a continuous line joining past and present, with no definite beginning or end, rather than on documenting the temporal ruptures and shifts.

What emerges is an antimaterial view of history and civilization, where the site of violent conflict—and of progress—shifts from the material world to the individual soul. By the end of Hind Swaraj, Gandhi’s

satyāgrahi12 is urged to relinquish attachment not only to Western “railways,” “lawyers,” and “doctors,” but also to their own body. Gandhi advances this radical argument by drawing on the antimaterialism of the Mahābhārata, a seminal work of itihāsa. Satyāgraha “is a method of securing rights by personal suffering,” requiring the “courage” to “approach a cannon and be blown to pieces” and “kee[p] death as a bosom-friend.”

This language evokes the Bhagavad Gītā [Song of God], a portion of the Mahābhārata in which God, through the deity Krishna, persuades

12 Practitioner of satyāgraha.

the archer Arjuna to return to battle after he retreats in fear of slaying his relatives on the opposing side of a great war. Krishna reminds Arjuna of the cyclical nature of material existence—

“jātasya hi dhruvo mṛityur dhruvaṁ janma mṛitasya ca” [for one who is born, death is certain, and for the dead, (re)birth is certain]—urging him to sacrifice attachments, perform his duty at battle, and liberate his soul.13

It is striking that Gandhi

invokes the Mahābhārata, an account of cosmic war, in a work that argues against the very anticolonial “extremists” who cited this text to justify violence against the British.14 As Simona Sawhney argues, Gandhi’s reading of the Gītā reveals how itihāsa can strip conflict of its material quality, recasting it as an internal battle overcome by self-sacrifice. Hence, Gandhi analogizes Arjuna’s struggle to the satyāgrahi’s, claiming the “true Kurukśetra [the battlefield on which Mahabhārata‘s war was fought] is our body.”

In turn, Gandhi does not see a lack of material conflict as a sign of stagnation. Periods of “nature” carrying on sans “interruption” are moments of spiritual progress when soul-force prevails in individuals. This inverts Hegel’s naturehistory distinction to associate the former, not the latter, with the realization

13 The mention of “birth” for the dead references reincarnation. As Simona Sawhney observes in The Modernity of Sanskrit, in the Gītā and subsequently in Hind Swaraj, “to be selfless is perhaps to be concerned solely about the transcendent and otherworldly self,” existing independent of the physical body and the material world.

14 Cf. “extremist” Hindu nationalists such as Sri Aurobindo and Bal Gangadhar Tilak.

of higher consciousness. The Indian villages Hegel and Marx identified with stagnation under “Oriental despotism”—unable to progress dialectically until British rule engendered material change—Gandhi views as remnants of a higher age, ancestors “satisfied with small villages” for they saw “happiness [as] a mental condition.”15 His ideal of swarāj is neither Hegel’s nation-state nor primitivism. Rather, it centers on individual “self-rule,” realized by and within the self, not through the state law-making or revolutionary violence—both of which, to him, remain bound up in materiality.

We are thus left with two philosophies of history, Geschichte and itihāsa, which

seem to be negatives of one another, in a dialectic of material and spiritual, temporal and eternal.16 While Hegel maintains an idealist stance—which later thinkers such as Marx would invert—his Geist [spirit] must be realized in the material world, and thus, functions differently from the notion of spirit realized by transcending materiality in Gandhi’s framing. The question remains, if we might extend this dialectical analogy one step further, whether or not there is any sublation.

Some reckoning of these two philosophies of history seems urgently necessary. We saw Mill deploy stadial progress to marginalize Indians’ liberty, revealing the dark side of Geschichte, and Gandhi subsequently use itihāsa to recast these derisive perceptions of India, reconceptualizing swarāj in

novel and radical terms.17 Yet itihāsa raises other concerns. On his part, Gandhi condemned child-marriage, bans on widow remarriage, and the ill-treatment of Dalits as social “defects” that must be eradicated: to him, these had no place in India’s “ancient civilization,” so they can have no place in twentieth-century India. Yet the problem remains that the supposed changelessness of Indian society and sacrality of its Sanskrit canon was deployed by a conservative Hindu orthodoxy, in complicity with colonial authorities, to entrench these practices at the expense of women, Dalits, and other marginalized Indians. In other words, as Pollock argues, conservative power could use itihāsa to “naturalize” existing “asymmetrical relations of power,” claiming these

have existed since time immemorial.

Where does this leave Indians who were socially marginalized by orthodox Hinduism—specifically Dalits and women? Their case is especially fraught when we consider how their marginalization was invoked by proponents of the Western-European ‘progress’ narrative. Hegel, conceding that a Hindu legal code exists, finds that “social differentiation was immediately ossified into caste distinctions” in India, preventing the coalescence of civil society and the nation-state. Mill and other liberal imperialists argued that gender relations were a measure of civilizational progress, seizing upon satī, 18 child marriage, and other orthodox Hindu practices to argue for India’s inability

17 At the time of Gandhi’s writing this text, nationalists’ political demand for swarāj was at best dominion status within the British Empire, which would have preserved Britain’s political structures; it was only in 1930 that the Indian National Congress began to seek pūrṇa swarāj [complete self-rule], i.e. full political autonomy from the British, a position that likely still does not go as far in disavowing the structure of the European nation-state as Hind Swaraj does in 1909.

18 Lit.: “she who exists,” an idiomatic reference to a “good woman” or “good wife”; this term would be used by the orthodoxy to describe widows who died by self-immolation in their husbands’ funeral pyres, and subsequently by the British to describe this act of widow self-immolation for the purpose of outlawing it in 1829. See Lata Mani’s Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India (1998).

to enter into “modern civilization” on its own. If any resolution is to be found between Geschichte and itihāsa, it can perhaps only be found in the figure of the socially-marginalized Indian subject, denied direct recourse to both philosophies in their original forms to escape being subjugated as Indians on the one hand, and as Dalits or women on the other. We finally turn to the approaches of two such authors, Ambedkar and Mahadevi.

Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste

Ambedkar, a Dalit scholaractivist who studied at the London School of Economics and Columbia University

before returning to India in the 1920s, launches a searing critique of Hindu theology in his Annihilation of Caste that resists any glorification of Indian ‘changelessness.’ He takes issue with nationalists’ argument that Hinduism is redeemed by the fact that “Hindus have survived.” To Ambedkar, eternal existence is no source of pride. “It seems… that the question is not whether a community lives or dies,” but “on what plane does it live,” he writes, concluding that “a Hindu’s life has been a life of continuing defeat.”

He thus rejects not only Gandhi’s praise of India’s changelessness in the tradition of itihāsa, but also the European Orientalist construction, reflected somewhat in Hegel, of an Indian ‘Golden Age’ that produced a venerable Sanskrit canon. To Ambedkar, there is no glorious past from which India fell into decline and stagnation (per the Orientalists) or which present-day Indians can revive (per the nationalists). He instead sees “a life which

is perishing everlastingly,” a canon of Sanskrit works mired in the material reality of an oppressive caste “system” that had no place for Dalits or, as he later alludes to, for women.19 The only recourse is a break from the past, specifically the religious past, so that it can no longer authorize castebased power relations.

We see Ambedkar move to recast stadial progress to advance a compelling argument that “social reform” to abolish caste must take precedence over any “political” or “economic” agenda. As he notes, this puts him at odds with both committed nationalists, who primarily sought political independence, and Socialists, who primarily sought economic restructuring. Turning to nationalists’ views first, Ambedkar claims “political revolutions have always been preceded by social and religious revolutions,” citing the

Protestant Reformation as a “precursor of the political emancipation of the European people,” Muhammad’s intervention as a religious revolution paving the way for “Muslim Empire,” and “the religious and social revolution of Buddha” preceding the “political revolution led by Chandragupta.” Per Ambedkar, political change cannot be realized without social reform, which in India must take the form of the abolition of caste within Hinduism. Note Ambedkar’s historical references—spanning Western Europe and Central and South Asia—which break from Hegel’s Geschichte in acknowledging the prospect of revolution in the supposedly stagnating ‘Orient.’

Ambedkar proceeds to extend this argument against socialists, asserting historical difference to once again reformulate the philosophy

19 It remains unclear as to what gender relations will become in the aftermath of abolishing caste—Ambedkar divides “social reform” into two categories, “reform of the Hindu family” (child-marriage, satī, widow remarriage) and “restructuring of society” (the abolition of caste) early in the work to argue for reformers’ neglect of the latter. His later invocation of women might indicate that he views these two reform struggles as intertwined; see ibid at 219, 270.

of stadial progress. “The fallacy of the socialists lies in supposing that because in the present stage of European society property as a source of power is predominant, the same is true of India, or the same was true of Europe in the past,” he argues. While Ambedkar compares Europe and India, his invocation of historical difference breaks from Hegel’s Eurocentric chronology that placed India at “childhood” and Europe at “old-age.” Nor does Ambedkar suggest India blindly imitate Europe to realize freedom—indeed, quite the contrary. “If the source of power and dominion is, at any given

time or in any given society, social and religious, then social and religious reform must be accepted as the necessary source of reform,” he concludes, a resounding statement of his argument regarding the social reform agenda that must be adopted in British India. Certainly this is closer to Geschichte than to itihāsa, for it heeds the temporal context of a particular society; however, here stadial progress does not inevitably culminate in Europe and leave India in stasis.

We might situate Ambedkar’s intervention in a longer tradition of recasting Hegelian dialectical progress: spanning Marx, who argued the nationstate must be sublated to arrive at Communism, and Nietzsche, whose dialectic, far more violent than Hegel’s “slaughterbench,” resists the inclination to ascribe meaning to violence and suggests that we might never arrive at a final sublation. Where Ambedkar breaks from these nineteenth-century European philosophers is in his

commitment to nonviolence, including his use of the language of reform rather than violent revolution, which is closely tied to his refusal to entirely relinquish religion.20 He seeks to desacralize the Āryan past that had been glorified by Orientalists and conservative nationalists alike in ‘Hindu law’ texts such as the Manusmṛti, declaring the “remedy is to destroy the belief in the sanctity” of this canon. Yet he leaves openended the result of this stadial reform—he cannot determine what religious doctrine will take the place of existing Hinduism. To his Hindu audience, he declares,

You must give a new doctrinal basis to your religion—a basis that will be in consonance with liberty, equality and fraternity; in short, with democracy. I am no authority on the subject. But I am told that… it may not be necessary for you to borrow from foreign sources, and that you could draw for such principles on

the Upanishads. Whether you could do so without a complete remoulding, a considerable scraping and chipping off from the ore they contain, is more than I can say.

Months before Ambedkar died in 1956, he converted to Buddhism, disheartened by the Hindu and Muslim religious orthodoxy’s refusal to pass a Uniform Civil Code that would have regulated social reform across all religious communities in independent India. Yet in the above lines, we see a younger Ambedkar positing stadial progress whose culmination, unlike in Hegel’s Introduction to the Philosophy of History, remains indeterminate. He suggests there might be emancipatory potential in certain Sanskrit texts, but they must be reread critically, with recognition of historical difference—without blind veneration afforded to colonial and brahmanical constructions of India’s

20 Ambedkar’s defense of religion in the form of Buddhism defies the rejection of religion in both Marx, as the earliest form of man’s “self-alienation,” and in Nietzsche, as a manifestation of the “ascetic principle.” He also dismissed Communism on the grounds that he agreed with Socialism’s ‘ends’ but not the ‘means’ of violence; see Gail Omvedt, Dalits and the Democratic Revolution: Dr. Ambedkar and the Dalit Movement in Colonial India (1994).

religious past.

VI. A Feminist Recasting of Itihāsa: Mahadevi’s Chānd Editorials

Here, on the subject of conversion, we might turn to Mahadevi’s intervention as an alternative approach to reckoning with stadial progress and itihāsa. As a young woman, Mahadevi had considered converting to Buddhism and becoming a bhikkhuni [Buddhist nun] to escape her Hindu child marriage. However, she eventually rejected

the view that conversion would be emancipatory. Troubled by patriarchal structures she encountered in Buddhist monasteries, she grew acutely aware of the dominion religious orthodoxy claimed over Indian women, extending even beyond the Hindu context. Unlike Gandhi and Ambedkar, Mahadevi was not sent abroad to study—women, even from higher-class families, rarely were—and received her B.A. and M.A. in Sanskrit in Allahabad. There, after encountering Gandhi’s

Hind Swaraj in the 1920s, she became committed to satyāgraha, vowing to communicate exclusively in Hindi for the remainder of her life. Mahadevi thus is left with a more limited exposure to Western reference points such as Hegel, Mill, or Marx, but contributed significantly to Indian anticolonial and reformist circles through her Hindi essays and poetry. Her linguistic background, moreover, renders her well-situated to re-read India’s scriptural past—as Ambedkar briefly alludes to at the end of Annihilation of Caste—to seek liberation for

Indian women.

Thus, as we have seen Ambedkar recast stadial progress to find emancipatory potential for Indian Dalits, we see Mahadevi recast itihāsa to find emancipatory potential for Indian women. In a series of 1930s editorials she published for the women’s journal Chāṅd, Mahadevi moves seamlessly between her present and an indeterminate past, reflecting the atemporality of the itihāsa tradition, while introducing a critical awareness of the material subjugation of

women that accompanied their attempts at spiritual “progress.” “Objects that are more beautiful or delicate than ordinary, earthly objects are… either elevated to the rank of the celestial” or “become the objects of neglect and disdain,” she writes, and “the irony of fate has made Indian woman experience both these states fully.” She offers no temporal reference points, which seems more reminiscent of Gandhi’s treatment of the past than Ambedkar’s. Where Mahadevi casts beyond itihāsa is in arguing for a duality of material and spiritual conceptions of the past, rather than denying the former entirely. The Indian woman was at once “goddess in the sacred temple” and “prisoner in… her home,” her spiritual advancement imperiled by the threat of material subjugation. The spiritual cannot be considered without reference to the material.

This approach generates

a powerful re-reading of India’s past, wherein Mahadevi finds a lineage of female resistance that extends from the female characters in works of itihāsa to present-day women anticolonialists, poets, and saints. Taking the character of Sītā in the Ramāyaṇa, invoked by Hindu nationalists to construct tropes of female selfsacrifice, Mahadevi instead finds a woman whose “life embodies courage,” following her path of duty despite being unjustly banished by her husband. Juxtaposing Sītā’s material deprivation with her mental fortitude, Mahadevi identifies “courage” where her orthodox contemporaries had valorized female “meekness.” Such was the legacy of “so many women,” from Mughal-era female saints such as Meera and warriors such as Padmini, to British-era revolutionary women such as Rani Lakshmibai, and women writers whose literary works have “given voice to… the

Indian woman.”21 Mahadevi turns to the past and finds a tradition of female resistance that transcends temporality, emerging from women’s striving for spiritual progress amidst material subjugation. The corollary to this argument is that women and other marginalized Indians have been lied to about their past: they have been told that their subjugation is the result of eternal religious law, when in fact it emerged from contingent material conditions. “Under the pretext of preserving an artificial past,” writes Mahadevi, “the devis [goddesses, women] have tolerated numerous injustices, not because they do not have the power to resist, but because they thought they would be deviating from their duty if they questioned the rightfulness of acts of men’s society that were supposedly based on law.” Here we encounter the nuance of Mahadevi’s use of itihāsa,

her refusal to “blindly” romanticize ancient India.

Female self-sacrifice, lauded by nationalists such as Gandhi as a model for the satyāgrahi, is “worthless, like the submission of helpless… animal,” if the woman has not “investigat[ed] the rightfulness of [the] principle” on which they are based—that is, if they are forced by her material subjugation, denying her spiritual selfhood and interiority.

Thus, like Ambedkar, Mahadevi also repudiates ancient codes of law such as the Manusmṛti that enshrined the inferior status of women and Dalits. Yet while Ambedkar invokes the language of stadial progress to break from India’s spiritual past, Mahadevi argues against these law codes by historicizing them: she ties them to materiality and thereby devalues them within the ontological framework of itihāsa. The laws that “contracted all

21 Meera was a sixteenth-century Hindu saint whose devotional Bhakti poetry was an early inspiration for Mahadevi; Padmini, a thirteenth-century Indian queen; Lakshmibai, a nineteenth-century Indian queen who played a central role in leading the Revolt of 1857 (which Mahadevi here refers to as India’s “first war of independence,” and colonial histories dismissively refer to as a “sepoy mutiny”).

of women’s rights” and “erect[ed] walls of caste” were the result of material “warfare,” she argues, which “affected the position of woman in society to such an extent that [she] began to be thought of as man’s individual property.” For evidence, she does not turn to the historical archive— as Ambedkar does in his references to religious reform movements—but instead returns to the treatment of women in works of itihāsa. “The society of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana,” enmeshed

in warfare, “is a blazing testament to this fact,” its ill-treatment of female characters manifest in “the fire ordeal, or the exile of a virtuous wife, or the staking of a wife in the game of dice like any other item of wealth.”22 Breaking with Gandhi’s antimaterialist readings of these epics, Mahadevi makes explicit the material reality of war and its implications for the legal subjugation of women, even while she lauds the spiritual resistance of female characters such as Sītā. Re-casting the itihāsa

framework, she thus argues that “it is now necessary to change the various ancient legal provisions that affect women negatively” to secure conditions that will allow women’s spiritual progress towards eternal Truth.

Thus, the language of “progress” and “reform” takes on a new cast in Mahadevi’s editorials wherein its realization is no longer predicated on a full disavowal of the past. As she would describe in a later essay,

Since this stream of progress is restricted from one side by time and place and from the other by eternal life values, it creates a union of the old and the new in each age. We understand our culture’s original source and aim by looking at our own times in the same way that we apprehend a river’s unseen

origin and final destination from a limited perspective from the shore.

Her naturalistic metaphor— reminiscent of Gandhi’s association of “nature” with “soul-force” in Hind Swaraj—maps a terrain of the past which has no definite beginning or end, no clear sense of temporality, and is certainly closer to itihāsa than Geschichte. Simultaneously, its insistence on “progress” resists the orthodoxy’s attempts to fix the figure of the Indian woman in the “past,” suggesting that itihāsa‘s emphasis on the spiritual over the material might be redeployed to imagine a liberating future for the most sociallymarginalized elements of Hindu society.

This investigation has sought to trace the critical project taken on by three Indian authors, Gandhi, Ambedkar, and Mahadevi, to define a new mode of relating to the past: a philosophy of history that would emancipate their

communities. Their task is all the more critical because the dominant philosophy of history in their times— Geschichte, as articulated by Hegel and deployed by Mill—constructed a version of India’s past that actively justified its colonization. Published at the turn of the century, Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj, introducing the philosophy of itihāsa and rejecting the material for the spiritual, offered a means of redeeming the “changelessness” that Hegel, Mill, and other Europeans levied as a charge against Indian peoples.

In the aftermath of Gandhi’s text, the subsequent interventions of Ambedkar and Mahadevi in the 1930s reveal divergent possibilities for how this negation of

Geschichte with itihāsa might be ‘sublated’ by looking to the margins of colonial society. Ambedkar cites historical difference to re-cast stadial progress; Mahadevi undertakes a possibly redemptive re-reading of India’s theological past. While these arguments might not converge upon a singular philosophy of history, they reveal the significance of critically examining the past for individuals actively involved in re-formulating the contours of their present. Before Gandhi could argue for Indian independence, and before Ambedkar and Mahadevi could argue for the simultaneous pursuit of “social reform,” they had to make freedom imaginable. To this end, they had to search for emancipatory potential at the very limits of history.23

23 Author’s Note: This is a revised version of a paper I wrote in April 2022 for my Contemporary Civilizations course. It was shaped by an unlikely confluence of experiences and mentors during my first two years at Columbia that I remain profoundly grateful for: Professor Sudipta Kaviraj’s Spring 2021 Gandhi and His Interlocutors lecture and continued guidance in office hours in Spring 2022; summer research on Mahadevi Varma’s feminist essays; Professor Manan Ahmed’s Spring 2022 South Asia: Historiography in Question seminar; Professor Shiv Subramaniam’s 2021-22 Elementary Sanskrit office hours (which frequently shifted from Sanskrit grammar questions to discussing German idealism); and Professor Charly Coleman’s Fall 2021 Enlightenment seminar and 2021-22 Contemporary Civilizations section.

Content warning: Some body horror

Iam never at peace. My unfinished tasks, unanswered emails, unfulfilled plans poke into my ribs like the underwire of a bra, an anxiety everpresent beneath my blouse. I could knit a blanket out of my loose ends.

Lately I feel gravity more intensely; if I walk past a patch of grass on the way home from work, one especially lush or especially vast, I fight the urge to lay down. Sometimes I lose, and end up staring at a network of leaves and branches, cells and capillaries, sinewy veins between leafy flesh, channels of light flowing through. I play at cloud shapes to distract myself, name them after anything corporeal. A cumulonimbus clown. A cirrus dove. A lock of stratus hair. Still these things come from flesh. It is not hair, I tell myself. It is a river, a streak of paint, an exhalation of smoke. I lie very still on the cold dirt and close my eyes and pretend I am a corpse. It’s the closest I get to peace.

So none of it is my fault, really. No matter what I did, I couldn’t sleep. It started with shorter periods. One all nighter was enough to drain me out, until it wasn’t. Then I went 36 hours without sleeping, and eventually two days. Then I stopped keeping track. My body forgot what it was supposed to be doing. I no longer felt like a human, so I don’t understand why anybody would be expecting me to act like one.

I go out on a Wednesday— it’s the first time I leave my house in days—and the first time I see friends (who think I am just busy with work) in weeks. I meet a Ukrainian lesbian on the back patio of a bar. She has tattoos and a bad haircut. She tells me how her friends at home have been captured and electrocuted by Putin’s forces. I tell her I am sorry about that. I offer her a drag of a cigarette, a limp-wristed apology. She declines. She doesn’t smoke. I learned a few lines of dialogue ago that she doesn’t drink, either. I have only ever been

electrocuted by mistakenly sticking my finger in a socket, so I can afford to waste youth on things like cigarettes and alcohol and all-nighters and going out on a Wednesday. I entertain myself with the thought that she does coke, molly, and ketamine exclusively, swears off gluten and dairy, and only sleeps in two to four hour increments, some commandment of the European techno-house lifestyle. But she is still here instead of Berghain. I am sobering up by the time our conversation trails off, but her face is still a black spot in my memory.

I find that in my new, sleepless lifestyle, I can’t recognize faces like I used to. I pass anyone in the street and see a face from my childhood, or someone I’m sure I know but can’t place, or someone stares at me or smiles and waves like we know each other, but they’re a collection of eyes and ears and skin that I’ve never seen before in my life. I know even now, looking at this woman’s face so intently, that I will forget it

immediately.

On Thursday, I miss work and all of the phone calls that follow my unexplained absence. If they can never contact me to reprimand or fire me, then I can never really be fired. That is the logic of someone whose brain is stuffed with cotton.

In between bouts of lying awake with my eyes closed, I spend the day scrolling through Instagram. In all these hours, I pull what is likely miles of content through my screen with my thumb. All of these glossy, symmetrical faces with their

medical-grade proportions. Pillow lips. Soft eyebrows you could knit a blanket with. Ski-slope noses and gentle hollows where their necks meet their collarbones, hard and soft at the same time, a perfect juxtaposition of chiseled jaw and slanted cheeks. The eyes of an innocent baby deer who somehow also wants to get fucked. She is androgynous but also distinctly feminine. She has the skin and the corrupting gaze of someone underage, but the elegance and assets of someone much older. I don’t know if I can never tell these women apart because I can’t tell anyone apart anymore, or because they really all just look the same.

I realize I can’t describe their cheeks as “supple,” though, not like I used to. There is something missing under the bones, as if years of posing with that flesh sucked in actually shot it down their esophagus until they burned it up in their stomach acid and shat it out of their pristine waxed-or-bleached assholes.

I eventually see a post about the trend of surgical buccal fat removal. So that’s where it’s all gone. I had always loved their cheeks. That soft, tender flesh, made for pinches from grandmas or kisses from lovers or as a reference point for the natural waning of age, sliced off and tossed into a metal bin and disposed of as biohazardous waste. I understand why they did it, even if I don’t agree with it. Their faces look more chiseled, and any threat of a faint pad of fat under their chins is gone. While still laying in bed, I push up on the underside of my own chin, prodding at the excess flesh I had never seemed to notice before. I stick my fingernail into the side of my face, right next to my ear, drag it into my cheekbone. I imagine all the flesh being stripped off. I already feel lonelier without these extra cushions, these margins of my face. I guess when you’re a centerfold, you don’t need them. If they don’t want this fat, I think, then I will take it.

They say New York is the city that never sleeps, but

whoever they are is a liar. The restaurants close and the people on the streets thin out, and even the pigeons go curl up somewhere in a tree for hours. I have this on good authority because I, unlike New York, really do never sleep, so I get to watch it doze off and wake up again. If that sounds romantic or poetic or beautiful, it’s not. It’s just lonely.

I have a shopping list, but it’s past 8 now and the hardware store is closed, so I have to wait to complete it. I toss and turn throughout the night. Sometimes I’m so sleep-deprived I get delirious and can’t even tell if I’m asleep or awake anymore. My thoughts get so vivid I think my subconscious may just have taken over. Most people experience sleep like stepping off a cliff into the water below, but my cliff has been so eroded by the blue-light of screens and medication interactions and my body’s inability to recognize the intended function of my bed, that for me it is more like a wading in. I had only met the Ukrainian lesbian a day and

a half ago, but it feels like a different season. I wonder if she knows how to swim past wading. I can’t remember if Ukraine is landlocked.

I think time must pass differently in the poorly-lit pit of my bedroom in this apartment. I only leave to pee or sometimes eat, and I only do it when I know my roommates won’t be around, scuttling from the fridge to the toilet (but never the shower).

It’s February, so the sun rises around seven. It’s Friday, so the store opens at eight. I alternate between sudoku and Tetris and 2048 on my phone until 7:55, when the sky through my window is the color of raw chicken breast. I grab my coat and hurry out of the apartment before either of my roommates wake up. The streets are blanched with sun and salt, and the cold air is probably supposed to feel good on my face, but it feels like I’m being cryofrozen into a grimace. I pass by the other early-morning risers, and wonder if they think I’m like them. If I tried, I could

go to work at nine. But not now, not today, because I have a mission.

It begins with entering the hardware store as soon as it opens, after loitering outside for about thirty seconds before they flip the sign. As such a punctual first customer, I am rewarded with the privilege of wandering through the tall, narrow aisles undisturbed. In the suburbs, aisles are wide and of reasonable height, but everything in New York is squished together and stretched upwards, and for a second the thought makes me so claustrophobic I want

to throw up. I wonder if I lived in a place with aisles wide enough for two people to pass by without brushing each other that I would be able to sleep. Inhaling so fewer chemicals and carcinogens, and turning off that constant background track of horns and sirens and screeching brakes and stray shrieks. Even if I tried to leave the city, though, I can’t see past the tall buildings or through the longer avenues, so I don’t think I’d actually be able to find my way out.

I finish my trip with proof of each item I’d written in my notes app:

• two coolers, red with white lids and black wheels

• a funnel, plastic with little risen ticks on the side to indicate volume

• two knives, one long and serrated for bread, the other small and sleek for fruit

• a 24-pack of Poland Springs bottled water

• a pool float, green and slightly translucent with smelly plastic, which a gruff man in a stained

t-shirt had to retrieve from the basement for me, because again, it’s February • and finally, a fairly nice blender, which I can afford because when you never leave the house, you actually find yourself spending a lot less money. I stuff all the things in either of the coolers and wheel them home fairly easily, and make it back to my room without a roommate sighting—or I guess without them having a me-sighting, because I am certainly the rarer breed. I can pretend I live alone in this state, or

maybe just with ghosts that share my bathroom and my electricity bill. If anyone is the ghost though, It’s probably me.

I wait until nightfall, scrolling on my phone, watching all the backstage stories of Fashion Week, catching glimpses of shadows on the sides of the models’ faces. A couple hours past sunset I put on black slacks and a white button up, the first time I’ve changed in days. I tie my hair back into a neat bun. I almost feel like a person.

I’ll spare you the boring details, because it’s not that fun to explain. I never actually expected it to work, you know, so if anything it’s sort of their fault for not having better security. You can find the show schedules online if you just click the right links. When I got there I just slipped in with some of the catering staff, and tried to convince myself I was really supposed to be there, so that it might reflect in my expression. The coolers made it more believable, actually.

The main room backstage had black floors and aisles of lit mirrors, framed by thick floor-to-ceiling curtains. I follow the caterers to a small room off of a less glamorous cinder block hallway, where they assemble white folding tables with trays of meat, cheese, fruit, and pastries. I read online that models are not allowed to eat or drink water for something like a whole day before, to dry and thin them out like strips of beef jerky. This, then, is their reward for walking a few hundred feet without passing out. I open the correct cooler, thankfully, and off in the corner on another table I neatly line up the bottles of water.

“I didn’t know we were bringing water,” one of the actual caterers said. Her face is familiar and foreign at the same time, like we have briefly locked eyes in line for a club bathroom once, but neither of us can remember.

“Oh yeah,” I reply. “I just work for the studios. They told me to put these waters in here before the show’s done.”

“Probably smart,” she says, and goes back to rolling up strips of Prosciutto into neat tubes. That was the most anyone would question me the whole time, and it was also the most I had said to anyone in two days. I was surprised my voice still worked.

I finish setting up the waters, trying to placate my shaky hands. I’m betting on the fact that the girls will be too delirious with hunger and thirst to notice that the bottles’ seals are broken.

When my task is done, I find the closest bathroom and sit in the wheelchair stall with my feet perched on the lid and play sudoku for 45 minutes. Then I return to the room. It’s a scene I couldn’t have imagined better myself. A group of them are collapsed on couches against the walls, splayed atop layers of clothes and coats. The wonderful and artfully presented product of both hunting and gathering on the tables was merely picked at. Too bad I have no time and even less of an appetite.

I find where I’d shoved the other cooler under the table, and retrieve both the long knife and shorter one, just in case, because I don’t know which one will work better. I roll the now empty cooler across the floor, and it makes a bit of a rattling sound, but none of the girls even flinch. I hope none of them are dead. The pills had never worked for me, so I thought if they were going to work for these women, who were probably hopped up on diet pills and stimulants, that I’d better be giving them a healthy dose. As one last measure, I shut the door and switch the lock into place.

Before, I spared you the boring details, so now I will spare you the gory ones.

I walked back down the long cinderblock hallway and out the side door without looking back. Upon completing my duty I wiped off any concerning substances from the outside of the cooler with some of the dresses on the couch. Tulle and nylon netting aren’t very absorbent, but it worked fine enough. When I

finally emerged onto the cold street, cobblestone and lined with sleek black cars, I could even see lights glittering on the Hudson in the distance. I think to myself that it’s funny the studios are in the Meatpacking district, ironic maybe. I take a deep breath, smelling the air. Now it really did feel refreshing. I was home free, and felt my heart beating, like a real human. It was adrenaline, a rush, anxiety—arguably one of the most mortal emotions.

Another reason I could never leave New York is that people don’t look twice when you are towing two giant coolers down the street or on the subway. Some guy even helped me carry them down the steps into the station. I had latched them securely, thankfully, so neither opened. Even if they spilled, the subway has seen weirder sights, and even weirder bodily substances. Much like the hardware store man had not asked about my needs for a pool float in February, this man did not inquire about the contents of my coolers. And they say New Yorkers are rude. Like I

said, they are a liar.

I check my roommates’ locations in the intermittent service I get on the ride home. They are both at different downtown bars, and will be out for at least the next hour. I get home without a hitch, though I am now sweating from all of the dragging. I did not think of how heavy the coolers would be, or at least how atrophied my muscles have become.

In my room I peel off my clothes and put on a fresh combination of t-shirt and sweatpants, in dark colors, to be safe. I plug in the blender, which I have already unpackaged. I unroll the float. And since there is nothing else to do, I immediately begin grabbing gobs of flesh from the coolers, placing them in the blenders, putting it on the “liquify” setting, and then dumping the blender’s contents into the float via the funnel. I do this about twenty times, my fingers

sore and my forearms burning, when I realize I am actually beginning to

feel tired. I think I may have found exactly what I needed to shake up my circadian rhythm. This little excursion has been good for me.

Once both coolers have been scraped clean, the float is a bit squishier than I’d like, but certainly full. I rip off my sheets and comforter, and take the clean, fresh pair from the bottom drawer of my dresser. The float fits quite well on my twin bed, if not a bit too narrow. I ease over the fitted sheet, then spread the loose one on top of it, creasing the corners in the manner of a video I saw online. The ritual is soothing,

and I think I can even feel a yawn swelling in the base of my throat. I add the comforter, plain and white like my walls, and finally a singular pillow at the head.

I slip in, careful not to disturb all of my expert folding and smoothing and tucking. I lay my head on my pillow and put my hands at my sides over the comforter. I close my eyes. I feel my body sink into the ocean of fat beneath me, then into the mattress, through the floors below and the dank warmth of the basement, into the soil with the pipes and worms and chemical runoff, until I am falling into nothingness. I

pretend I am like the models: paralyzed and hollow, cheekless. I did them a favor; I removed it for free. Giving me a new mattress topper is really the least they could do.

The matter I sink into is human. It’s flesh, it’s body, just like me, just like what’s inside me, my face, my thighs, my lower stomach, purely human, untouched by scalpels or the blessed curse of otherworldly beauty. My humanity is still in my face. It cannot be taken from me by days of living as a corpse, but I can choose to cut it out.

The skin of my back and my mattress topper are fused together somehow, through

the lifeless fabric of cotton sheets or a polyester-blend t-shirt. I am human.

I don’t need to look at clouds to visualize the body. I don’t try to fight it, either. I etch cheekbones into the backs of my eyelids, sovereign and stolid as the frame of the face, gaunt and glorious. Cliffs you could fall off into seas of discarded tissue, 115-degree angles gifted by God and perfected by me.

I tumble back into the flesh and the bone and the fat and the blood, it all looks the same when you get beneath the faces, you know, and now all of the faces look the same too. I am no longer wading, I am falling, floating, I can feel myself suspended in the liquid, a corpse adrift. Until there is really nothing—if I am not dead, then at the very least I am asleep.

Bernard Harcourt is the Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, and is the director of the Initiative for a Just Society at the Columbia Center for Contemporary Critical Thought. In addition, Professor Harcourt is a prominent author on modern critical theory and political theory. His recent writing has focused on mobilizing praxis in the modern world, looking to collectivist movements to motivate action. Professor Harcourt also facilitates the 13/13 Seminars, an annual set of talks focusing on an issue in contemporary critical theory. This year’s talks are centered around utopianism, attempting to carve out utopian visions in response to modern crises.

Gadfly: The philosophical work that you, as well as the panelists of the 13/13 series, engage in to formulate new conceptions of utopia is one in which the status quo is in constant contention. I was hoping we could begin by defining your concept of the radical theory of illusions and how it can help us towards that end.

Bernard Harcourt: Before delving into the concept of illusions, I think it’s important to understand that it needs to be framed within the context of both

values and of action. It is a foundational piece of a critical theory of action, because it unveils ways of understanding the world. I tend to think that we are able to place ourselves in a different position in relation to the world and to our own actions. So in a way the theory of illusions is a condition of possibility, even of action. And your question is interesting because, in part, you’re raising the problem of how a positive vision of a concrete utopia can escape the problem of illusions. In other words, if one has a radical theory of

illusions, wouldn’t it apply as well to utopic visions? And I think it does. In the sense that part of the theory of illusions is a recognition that we always need to engage in a critique that is likely to undermine our own reconstructed visions of the future. And so, I have no doubt that the kind of concrete utopias that we might be coming up with today should be subjected to critique and that in some distant future, should we be fortunate enough for them to be realized, we will need to overcome them as well. This is where the theory of illusions intersects with the theory of action: it should not be limiting or discouraging, but rather should encourage ongoing critique and action, with the knowledge that there will need to be more action in the future and more critique, critique of illusions of the illusions that are in those very utopian visions that we’ll need to get beyond in the future. But that’s where action, or praxis, is so important to the theory of illusions. You can’t stop with the critique of illusions.

That seems to connect to Susan Sontag’s 1979 Rolling Stone interview where she says: “In more grandiose moments, I think of myself as being involved in this task of lopping off heads, as Hercules did with the Hydra, knowing perfectly well, of course, that this same kind of false consciousness and demagogic thinking will turn up somewhere else, the task of a writer is to be in an aggressive and adversarial relationship to falsehoods of all kinds. The issue is that the only criticism of society I see comes from the state itself.” It seems that Sontag engages in a similar sort of unmasking work that you point to in the radical theory of illusions, but puts the onus of action on the individual.

What I find so inspiring about the Susan Sontag quote is the idea of trying to engage in social transformation, understanding that it will be a constant struggle and that there will never be a finished product, but that

there will be other hydras to cut off that will arise again. And I find that particularly inspiring because it’s a consciousness of the immensity of the struggle without giving up on the struggle. And it’s also a view of history that doesn’t have a conception of the end of history, which I think is particularly anathema to a radical theory of illusions.

As in the famous Walter Benjamin line: “History has no telos.”

Right. And I suspect that on both sides of the political spectrum, that notion of telos or that notion of an end of history is one of the most dangerous ideas. Whether it’s coming from a Fukuyama kind of liberalism as the end of history, or whether it’s coming from a Marxist withering of the state as an end of history. The idea that the state would be the only target is problematic to me. In terms of the ways in which we critique illusions, we have to be open to and willing to critique collectives as well as individual efforts, which can sometimes go off

track. So I think that it would be equally problematic to focus only on the state. Now, of course, in all of this, the state plays an enormous role. And there’s a lot of controversy over the relationship to the state in the context of utopian thinking. There have been anarchist utopian traditions, there have been socialist utopian traditions that have, of course, a completely different relationship to the state and overall, my position here is that static institutional structures are inevitable but that the question of the state can’t be thought of just from the perspective of either getting rid of the state or having a strong state, that’s too simplistic.

The key question with regard to the state is whether the impetus and the imagination and the Praxis is coming from the bottom in the sense of coming from individuals and collectivities in their own capacity, or whether it’s being controlled from the top. So that, to me, is the greatest axis along which we need to be thinking. And along that line, I tend to think that both neoliberal, extractive, capitalist regimes today, as well as singleparty, communist regimes, are top-down structures of a very similar ilk: both being a form of top down, what I would call dirigisme, versus

a utopian ideal of bottom up cooperative organizing. And that’s something I try to spell out in a forthcoming book called Cooperation: a Political, Economic and Social Theory, which will be coming out in April. But the idea is that a distilled form of cooperation, what I call “Co-operism,” represents a different framework, a different regime, political, economic, and social, to both extractive capitalism and communism. The main difference being its relationship to the state, which was where this conversation started, insofar as it’s not state driven, but rather driven by people in

collectivities, trying to work together in cooperative forms of social and economic organizing.

The 13/13 Seminars this year all center on this idea of a concrete utopia. Could you explain that specific conception of utopianism and why you see it as politically valuable?

I think it’s important to understand that today, critical theory takes a negative attitude toward the concept of Utopia. So you’re familiar with the fact that Marx and Engels, and many of their followers, criticize the utopian socialists and other utopian thinkers and had an understandable critique of the classic notion of Utopia as being something that instead of energizing praxis, demobilizes it. It was a critique that Marx originally leveled at religious thought—notions of the hereafter. And the same kind of critique was leveled against utopian thinkers on the grounds that imagining some future Utopia can be demobilizing in one’s relationship to the present.

And I think overall that particular critique of Utopia prevailed as a historical matter. I would say that history has negatively colored the way in which we think about conceptions of Utopia today. So, the dominant way in which we think about utopia is the critique of utopianism, and even outside of the critical theory context, a more basic critique of idealism or futurism. So part of the project of concrete utopias that has been going on for the latter part of the 20th century, with work by thinkers like Erik Olen Wright and others has been to reformulate a conception of utopia that can be more mobilizing, rather than demobilizing.