CRAFTSMANSHIP

What is Craftsmanship in the Age of Mass Production in Singapore 2025 Edition

Author: Faith Yeo Xin Yi Veronica [A0225095Y]

AR5806 Architectural Design Report AY2025/2026

Thesis Advisor: Prof. Christoffel Jacobus Meyer

Second Reader : Prof. Cheah Kok Ming

Acknowledgements

To all my Family that has been my strongest supporter throughout my academic Journey.

Professors and Advisors that helped to mature my design thinking throughout my 4 years in NUS Architecture.

Pan Yi Chen, Huay Wen Jun, Lee Tat Haur, Jacqueline Yeo, Thomas Kong, Christo Meyer and Cheah Kok Ming

To my Studiomates and close compadres that has been essential in my journey from Nanyang Polytechnic to NUS DOA,

Beverly, Dominic, Alison, Michelle, Lydia, and Geralyn Thesis Supervisor

RESEARCH ABSTRACT

Craftsmanship has long been associated with the production of intricate, traditional artefacts. However, as articulated in Richard Sennett’s seminal text The Craftsman, it is best understood as “the desire to do a job well for its own sake.” This ethos aligns closely with the vocation of the architect—whose responsibility extends beyond functional adequacy to the pursuit of delight, precision, and value for those who inhabit or experience the built environment. Historically and etymologically, this relationship is inscribed in the origins of the word “architect”: arkhi (chief) and tekton (craftsman).

Yet this intimate bond between design and making has become increasingly obscured in contemporary practice. As architectural projects grow in scale and complexity, and as mechanisation advances, the architect’s direct engagement with construction and material processes continues to diminish. Within Singapore’s context—where the reliance on mechanised production and a shrinking skilled workforce has redefined the building industry—this separation between the arkhi and the tekton raises pressing questions about the future of craftsmanship in architecture.

This thesis critically re-examines the meaning and significance of architectural craftsmanship in Singapore’s highly industrialised construction landscape, where mass production and automation increasingly determine the form and quality of the built environment. By tracing the evolution of the architect’s role—from master builder to coordinator within distributed networks of expertise—the study foregrounds the persistent tension between theory and practice in both architectural pedagogy and professional work. Drawing from theorists such as Richard Sennett and Jeremy Till, craftsmanship is reframed not as a nostalgic remnant of manual tradition, but as an intellectual and social practice fundamental to architectural agency and innovation.

Through qualitative analysis of local construction practices, interviews with fabricators, and documentation of manufacturing workflows, the research investigates the hybridised coexistence of manual skill and machinic precision within Singapore’s construction ecosystem. The case study of Jean Prouvé’s Maison Tropicale exemplifies how the architect-craftsman can reconcile industrial production with material expressiveness through modular systems that remain adaptable and contextually responsive. These insights inform an experimental evaluative framework for architectural craftsmanship that extends beyond existing regulatory definitions of workmanship to encompass ethical, expressive, and contextual dimensions. The thesis culminates in the Rumah Singapura series—a conceptual prototype that translates the nation’s hybridised craftsmanship culture into a universal kit-of-parts model, proposing a locally grounded vision for craftsmanship in the age of mechanisation.

Word Count : 380

ACT 1

Modern Age of Craftsmanship

The Architect and The Craftsman

What constitutes architectural craftsmanship in an era dominated by mass production, especially within Singapore’s unique building industry? This research begins by asking how craftsmanship functions within architecture as a discipline. Contemporary architectural education often prioritises theoretical frameworks, aesthetic philosophies, and regulatory compliance over the act of building itself. Students are taught design principles aligned with the heritage of celebrated past and modern architectural movements, alongside societal expectations for comfort and regulatory approval. While these are important components of architectural education, this emphasis frequently sidelines a fundamental skill: understanding how buildings are constructed before conceiving them in design terms.

Historically, the role of the architect was inseparable from that of the master builder (from arkhi-, chief, and tekton, maker).—the chief carpenter or mason who took charge of both design and construction details throughout the building process1. In this tradition, the first architects were foremost skilled craftsmen, intimately engaged with the materials and methods of construction. Today, however, architectural pedagogy often reverses this process, placing less emphasis on materiality, assembly, and construction techniques. This troubling shift raises questions about the architect’s capacity to communicate precise construction instructions, assess workmanship quality on site, and lead the building team effectively. Without a deep knowledge of the craft, the role of the architect risks diminution within the very process of creation.

This reversal in the priorities and evolution of the role of the architect is in response to broader socio-economic and political forces—many of which lie beyond the architect’s direct control. This transformation saw the architect’s responsibilities move from those of a hands-on maker to solely those of a chief designer and contract administrator. Architecture education further reinforced this shift, as curricula increasingly prioritised theoretical and scholarly knowledge over direct construction experience. Simultaneously, advancements in building technology and rising expectations for construction quality contributed to a clearer division between the architect as a “scholarly chief” and the builder as a “practised maker.” This division marks a significant departure from the original etymological and historical conception of the architect as a master-builder, highlighting the ongoing tension between theory

and practice within the discipline.

This tension is further highlighted by Kenneth Frampton’s “Rappel à l’ordre” (1990), which emphasises modern architecture’s detachment from the act of making in the age of industrial standardisation, and admonishes the erosion of the expression of tectonics and the articulation of construction as a result.2

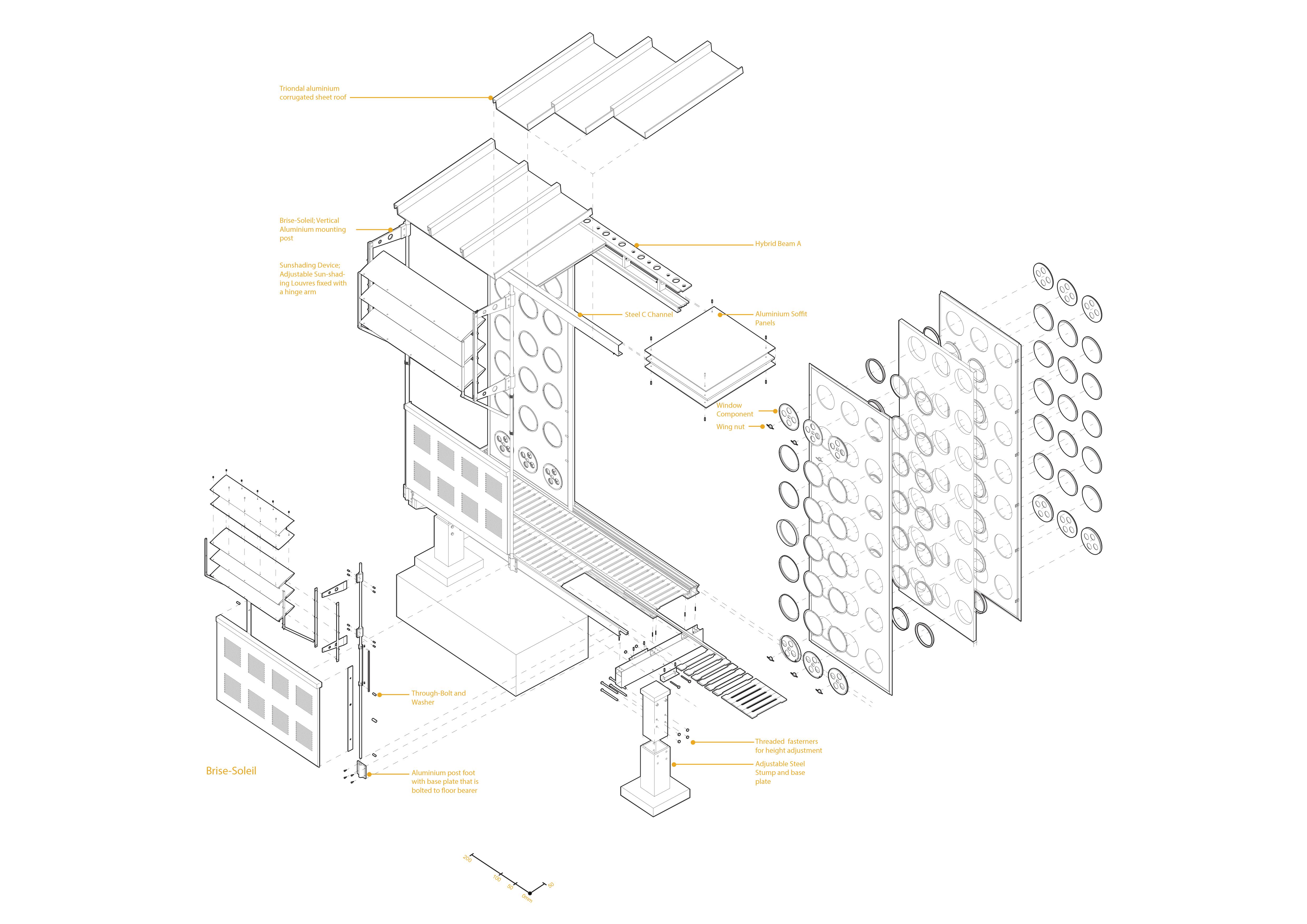

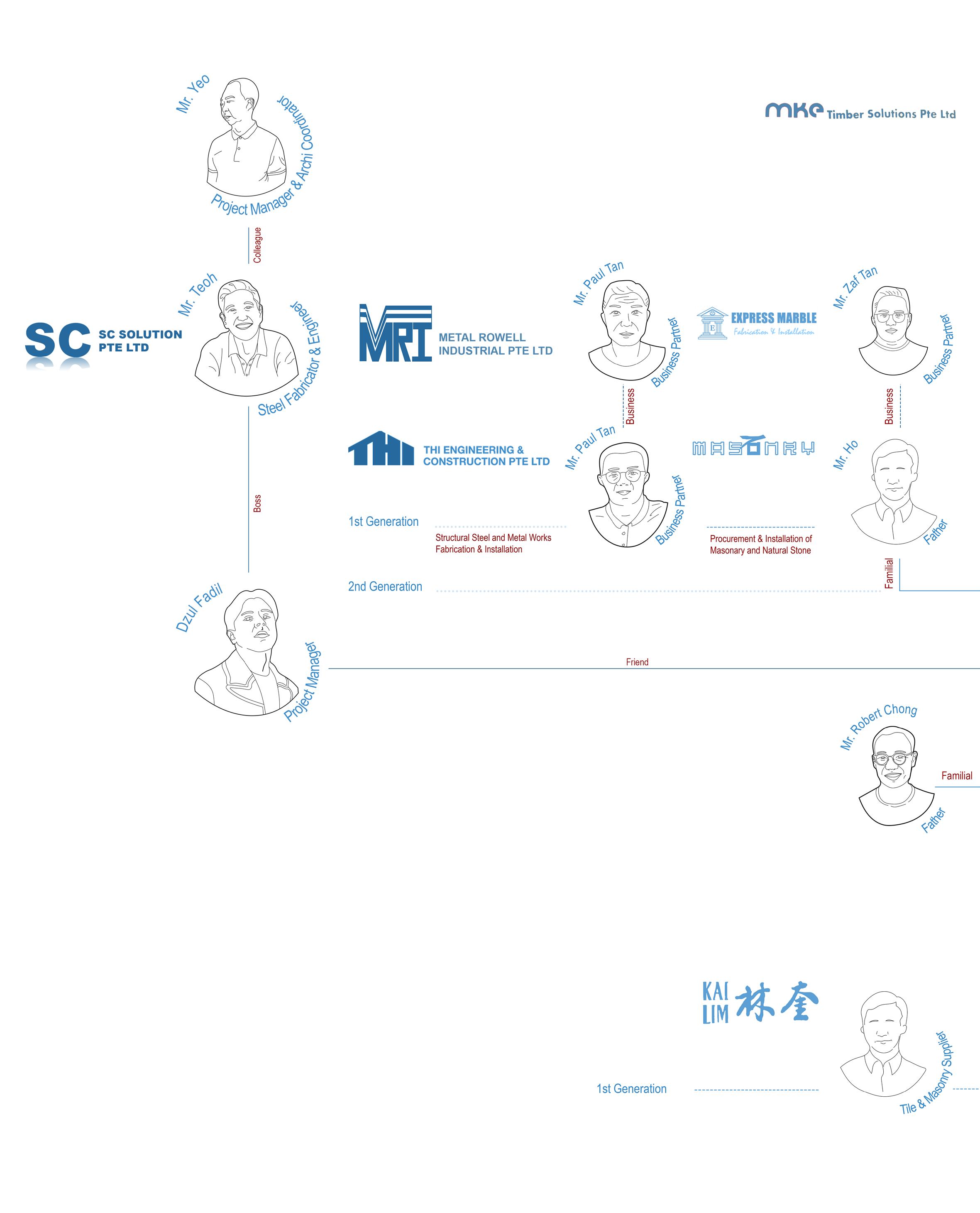

Social Nexus of Craft Knowledge

In the contemporary context, the tekton in arkhi-tekton is now represented by a range of other consultants, engineers, builders, contractors, manufacturers, suppliers, and construction workers who collectively constitute the architecture ecosystem. It is common practice for architectural firms to assemble their own teams of consultants before submitting a project tender, reflecting the collaborative and distributed nature of contemporary practice. This shift aligns with Jeremy Till’s concept of architectural agency, which asserts that the creation of architecture is dependent on the architect’s engagement with broader social systems, positioning the architect as a facilitator for the flow of construction expertise rather than as a solitary creator.3 In this social capacity, the architect is called to dismantle the professional power that separates the arkhi from the tekton, and

instead become the nexus where diverse forms of knowledge coalesce and are translated into specifications, technical detailing, and drawings— tools that communicate the purpose and intent of the design as the outcome of social engagement within the architectural ecosystem.

By extension, the specifications, technical drawings, and models used to facilitate social engagement become the artefacts of collaboration. Till’s notion of “social scale” further suggests a direct correlation between the scale of a project and the scale of its representation from the builders involved to the inhabitants that is to later stay in the project. The plan drawing addresses the needs of the inhabitants, and dictates how they interact with on another in a series of adjacent rooms, while the detail drawing that guides the individual

assembling the joint between a curtain wall and an adjacent structure. The presence of the people involved in the drawings adds an additional layer of empathy and invites a degree of consciousness to the people involved in the process of producing and constructing the building which might otherwise be forgotten typically when just drawing buildings on its own. 4

The process of ensuring that the craft of architectural design preserves its original form becomes increasingly challenging, as the design must survive multiple iterations and negotiations among the architect, client, the broader architectural ecosystem, and regulatory authorities. Even after significant effort to preserve design intent, the final execution may depend on whether the workman possesses the experience or motivation of a

craftsman to execute the job well for its own sake. Thus, if the modern architect can bridge the gap between arkhi and tekton—socially and technically— by developing tectonic strategies that are both expressive and communicable, the architect-craftsman can achieve exemplary craftsmanship and realise architecture of the highest order.

Workmanship in Craftsmanship

The ‘craftsman’ in singapore, often times is the migrant workers who were taught basic training in their home countries prior to coming to Singapore for work.5 Though the introduction of migrant workers into the construction industry was meant to be a temporary fix to a labor shortage in the 1960s, it is evident even now that this migrant workforce is still the backbone of our construction industry as Singapore is still heavily reliant on our migrant workforce due to the prejudice against blue collar vocational work in Singapore, leaving the construction industry running on a majority migrant workforce, especially as manufacturing workmen or construction workers. 6

To keep public housing affordable and accessible by matching supply to consistently high demand, Singapore’s population growth and a fundamentally small land area create continuous pressure on housing. This push toward cost-efficient and fast mass production, building technology like Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA), and Prefabricated Prefinished Volumetric Construction (PPVC) with the use of pre-fabrication and precasting, is evident in the BCA Buildability Series : Singapore industry standard for structural specifications, where talks of these technologies were present as early as back in 2001. The intent for the implementation of The Buildability legislation in 2001 was to raise productivity, reduce construction time, ensure consistently high quality housing units which offer a variety of finishes, that is quick to install on site and reduce the need

for Skilled Laborers.7 In addition, the implementation of the Dependency Ratio Ceiling that caps the number of foreign labor that can be hired to a fix ratio to the singapore hires - which due to the decreasing number of the young singaporeans joining the built environment industry for jobs that are less laborious, it is guaranteed that the number of construction workers that is hired and brought to singapore will slowly but surely dwindle.8

Singapore is placing more and more focus on new building technologies in commercial, industrial, and public institutional projects in addition to residential ones. The Buildability Score system requires all designs to receive at least a B–, which has been gradually raised over time to encourage automation and uniformity in the building sector.

7 However, there are serious concerns about the

future of Singapore’s architectural craftsmanship raised by this policy direction. The need for skilled artisans declines as the industry moves towards automation and mass production, which causes the artisanal workforce to shrink and, according to supply and demand, raises the price of handcrafted goods. Will craftsmanship become a luxury that only the wealthy9 can afford in such a setting? On the other hand, might developments in automated manufacturing provide a way to democratise craftsmanship, making it possible for more people to possess the meticulousness, attention to detail, and material awareness that are typically associated with a craftsman’s hand?

The concept of craftsmanship is widely invoked across a range of disciplines, commonly indicating skill, care, and mastery in practice, yet its meaning flexes according to context. As Richard Sennett argues, a craftsman is anyone “who does a job well for its own sake,” extending the scope of craftsmanship to include not only manual or material outputs, but also intangible achievements such as composing music or performing dance—what unites them is not the medium, but an intrinsic devotion to quality.10 This defines craftsmanship first through an ethos: a commitment to excellence for its own sake.

Tim Ingold develops this further, positing craftsmanship as a “process of correspondence”— making that is both intentional and skilled, proceeding through recursive dialogue with materials, collaborators, and circumstances.11 This resonates strongly with architectural practice, where learning unfolds through apprenticeship, and the architect’s responsibility extends from initial concept to deep collaborative engagement with consultants, builders, and authorities. The architect’s role, in this sense, extends beyond design to orchestrating communication and translation of intent, ensuring the finished work achieves the aspired quality and character.

Craftsmanship is also fundamentally an embodied practice. Ingold describes this as “knowing from the inside”—the craftsman merges explicit technical knowledge with tacit experiential insight, becoming attuned to the material’s capacities and limits through repeated engagement11. In architecture, this synthesis of explicit (drawings, codes, specifications) and tacit (sequencing, construction intuition) knowledge becomes legible in buildings that express thoughtful integration of intent, material, and construction expertise, ultimately producing environments that are functional, enduring, and meaningful. Across theories and disciplines, three recurring elements distinguish craftsmanship: emphasis on process and engagement with material; integration of technical ability with care, judgment, and learning; and a central focus on the maker’s relationship to their work—wherein quality itself is relational and anchored in intention.10,11

By this definition, the craftsman is not limited to the traditional craftsmakers we typically would associate with the use of timber and metal in the past when we were limited by our tools and technology, but the term craftsmen can also apply to the machine operators and material manufacturers that operate the tools of our time to produce components for the mass-produced homes that house the majority of our nation. For it takes considerable skill, experience in the process, continuous engagement with the material and constant improvements made to the quality of the work done. This is especially true for trades which are newer and require more experimentation to ensure consistency in the quality of output.

Hence, this thesis proposes that technology is not the terminus of craftsmanship but its extension, representing a new phase in the evolution of architectural making. Through this lens, craftsmanship is not limited to the traditional, ornamental or artistic but adapts rather than disappears amidst mass production.

Machine Craftsmanship

Frampton condemns that industrialised mass production has alienated architecture from the act of making as the ontological dissonance means of production conceals the origins of the materials process and the labor behind, hence “buildings become assemblages of systems and products, not expressions of constructive logic or human skill”. 12 Hence, calling for the reassertion of the expressive and ethical dimension of construction through expressing tectonics. This concern of mass production erasing the identity of the ecosystem of craftsman in the final mass product have long dated back to the time of Le Corbusier that describes this new age of housing the House-Machine, and that his vision was the adoption of the tools of our time can address the social needs of the people while also remain both functional and beautiful in the proportions, unity and function of the designs.13 Despite both renown Architects on the surface seem to directly contradict one another on the matter of perspective on mass-produced homes, they both raise concerns on the housing crisis of the modern world and how we should approach the technologies employed for mass production to ensure craftsmanship is still present in the mass produced homes.

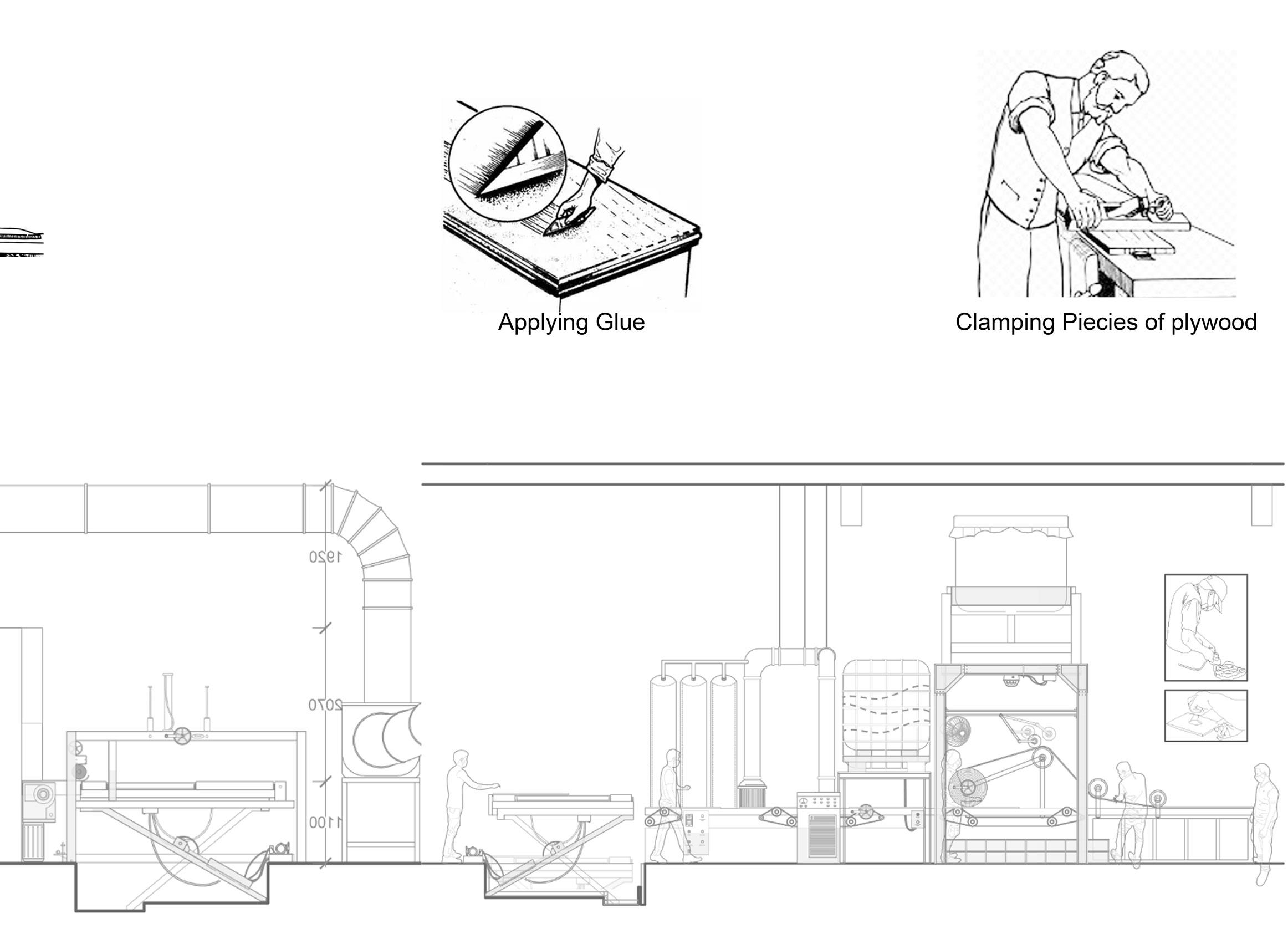

I would be remiss not to elaborate that the process of designing a building involves multiple expertise and revisions from the schematic, tender stages and detail design stages that requires the involvement of consultants like Engineers, manufacturers and material suppliers, along with the contractors who execute in the construction stage. For this portion of the report and in pursuit of gaining a better understanding of machine craftsmanship, I will document the process of the manufacturer, which involves the training of workers, producing materials, supply chain, tolerance and design considerations :

Tapping onto my existing connections, I had reached out to these craftsmen of our time and through a series of interviews and I had gained a deeper understanding of the supply chains that fuel these industries, along with the considerations taken into producing these mass produced components used in our built environment. Reflecting the role of a modern-day architects as a social conduit to understand the craftsmanship behind mass-production.

See the Appendix for the list of manufacturers/suppliers and interviews:

Sen Wan Timber

THI Engineering and Construction

Metal Rowell Industrial

Express Marble and Granite

CE Precast

*This is not an exhaustive list and will be expanded upon in the second semester.

As a case study that is to assist in further sections, I will go into depth of my interviews at THI Engineering and Construction and Metal Rowell Industrial, which was conducted graciously by Mr Paul Tan and Mr Alan Tan respectively.

*Reference A01-002 and A01-003 for the full scope of the interview

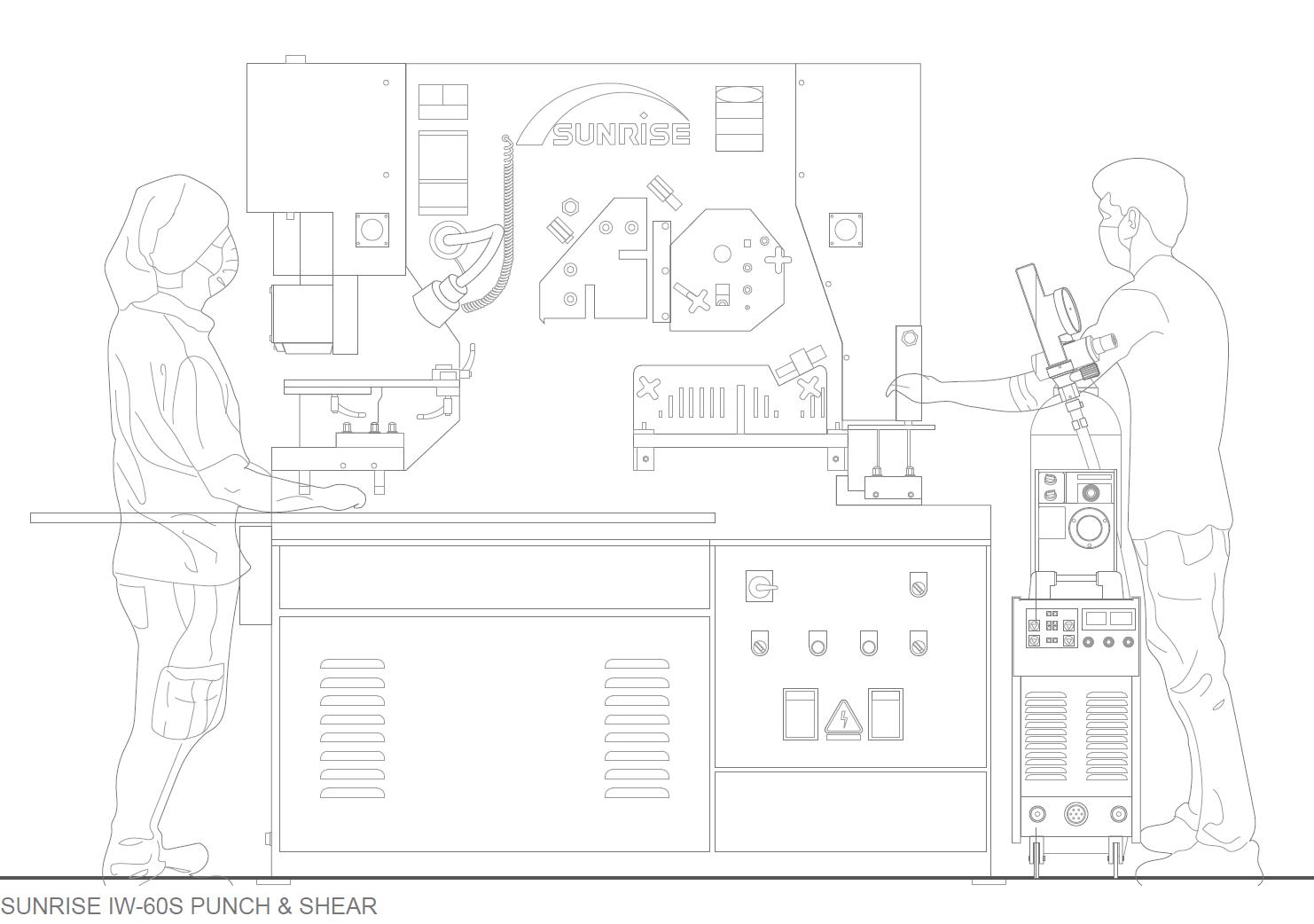

THI Engineering and Construction - Architectural Steel Prefabrication, and the secondary workhead is Structural Steel Prefabrication

Metal Rowell Industrial - This Company’s principal activity is general contractors (building construction including major upgrading works) with the manufacture of metal doors, window and door frames, grilles and gratings as the secondary activity.

Both Paul and Alan are first-generation owners of their respective companies, and were the first vocational workers in the earlier years of starting their companies. As each of their companies developed in later years and expanded to meet the demands of the industry, both have taken administrative/consultant positions as local and foreign labor was hired for hands-on work that directly connected to the manufacturing.

The services offered by both of these companies are tied closely together in partnership. This is a common practice in Singapore, as rental costs are high and hence firms will tend to collaborate and share resources to maximise the services offered while keeping operation costs low. These services include mass-production and fabrication of components as well as customisable components.

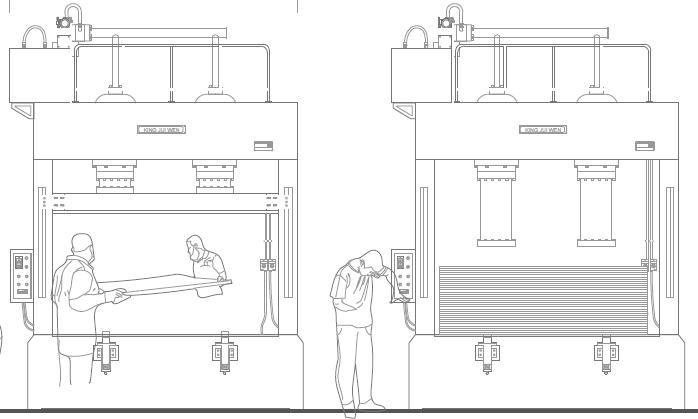

At this stage in time, both factory workflows are hybridised where most of the fabrication of components will require the use of the heavy machines, but afterwhich depending on the degree of customisation as required by the client, the craftsmans would be required to bend, weld or buff the material manually which requires the trained eye and hand to produce.

Process:

Consultant-Craftsmen : Consultation > Ideate fabrication > Cadding

Mechanical-Craftsman : Uploading CAD information to machines > Procuring Materials > Coordinating streamlined machine workflow (with or without additional hands-on manoeuvring)* > Executing

Metal Work-Craftsmen : Assembly of Components > Adding Finishes

Circling back to the previously established key principles of craftsmanship –

1. design by making, an emphasis on process and engagement with material;

2. integration of technical ability with care, judgment, and learning;

3. and a central focus on the maker’s relationship to their work—wherein quality itself is relational and anchored in intention.

**This process is iterative, and may require repeated alterations depending on the complexity of the component

It was clear that for the consultant-craftsmen, mechanical-craftsmen, and metalwork-craftsmen, there was a clear understanding of and engagement with the materials used. The development of the idea required familiarity with the material in order to reverse-engineer the fabrication process and transcribe the information into CAD files to be uploaded onto the machine. This was accompanied by the integration of technical ability in both the consultation process and the mechanical fabrication process,

where the executer must possess the understanding and skilled eye to ensure the products reflect the CAD data, as well as the mechanical knowledge necessary to operate the machines in the factory to produce the intended outcome. Lastly, it is evident in the work of the metalworker-craftsman that, during final assembly, finishing, and inspection, the human hand and eye remain vividly involved to ensure the final product achieves its intended outcome. 14

This development from idea to conception, and the handover that takes place among all craftsmen in the process, also supports the idea that collaboration is essential to the practice of craft. This is the minimum level of skill required merely to produce mass-produced components; there is a deep level of consideration and precision involved in creating an element that will consistently function as intended within the larger house-machine. 15 In order to advance craftsmanship, we must consider that the primary aim of mass production is to make the process of constructing a building more efficient and

streamlined, reduce costs, and ensure quality control and sustainability. However, as warned by Frampton and Le Corbusier, there must still be delight present in the material and spatial composition of architecture, which must not be lost to mindless fabrication. Hence, the quality markers of craftsmanship within mass production will similarly follow these key points. These criteria of good craftsmanship will be elaborated in the next chapter.

ACT 2

Craftsmanship Design Requirements

The demand for Good Craftsmanship

Singapore’s association with mass production is most visibly manifested in its public housing landscape. To meet housing demands and maintain affordability, the Building and Construction Authority (BCA) has long integrated modern construction technologies such as Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA) and Prefabricated Prefinished Volumetric Construction (PPVC) into the delivery of Built-To-Order (BTO) flats. These industrialised systems have enabled unprecedented efficiency, yet they also raise questions about uniformity and the loss of individuality within the domestic sphere.

This growing appreciation for craft within industrialised housing also underscores a broader demand for recognising craftsmanship within mainstream construction policy. Architectural craftsmanship is,

13 : Singapore Largest integrated construction and Prefabrication

What is Good Craftsmanship

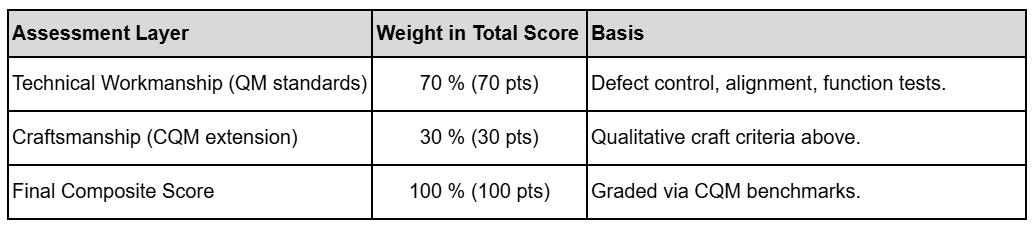

by necessity, entangled with construction practices— yet it mirrors the core tenets recognised by theorists of craft across disciplines. This brings us to the distinction between craftsmanship and workmanship, terms often conflated in both professional and regulatory discourse. As David Pye observes, “no one can definitively say where workmanship ends and craftsmanship begins” (1995, p. 20). In Singapore, however, this distinction is effectively institutionalised. BCA initiatives such as the Quality Mark for Good Workmanship and the Construction Quality Assessment System (CONQUAS) evaluate contractors and builders according to visible performance indicators—precision, conformance to standards, and freedom from defects. These frameworks ensure consistency and reliability, yet they privilege measurable outcomes over interpretive or qualitative dimensions of making.

While workmanship, as defined under CONQUAS, can be readily graded through visual inspection, craftsmanship exceeds such quantification. It encompasses the designer’s intent, material sensitivity, ethical judgment, and the purposeful integration of assembly and meaning. In this sense, the craftsman contributes not merely compliant work but an added layer of cultural and material intelligence that current rubrics fail to capture. If Singapore’s housing culture is increasingly seeking delight and individuality within industrial systems, then its evaluative structures should evolve correspondingly—to acknowledge the nuance, creativity, and care that constitute true craftsmanship within the built environment.

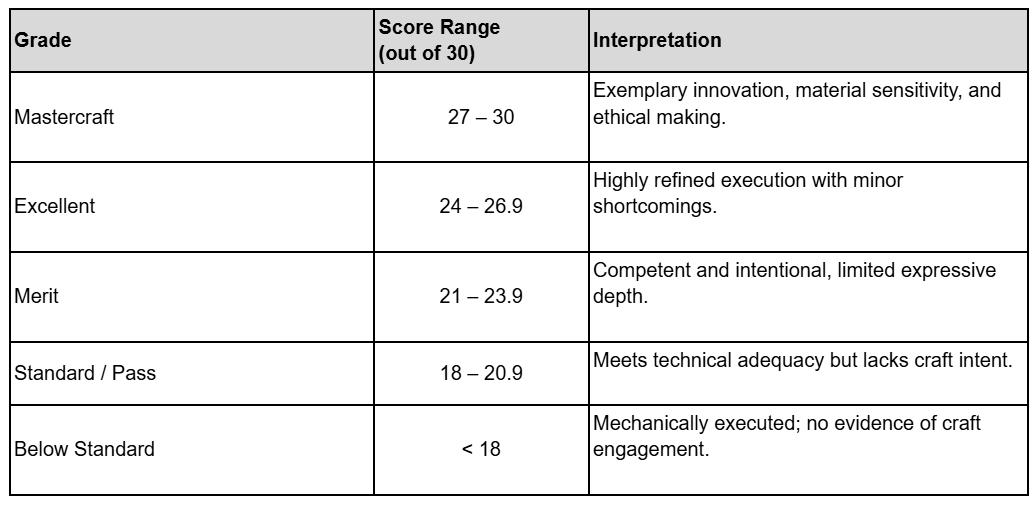

Fig. 16 : Table of Architectural Craftmanship Grading

Precedent Study on Jean Prouve

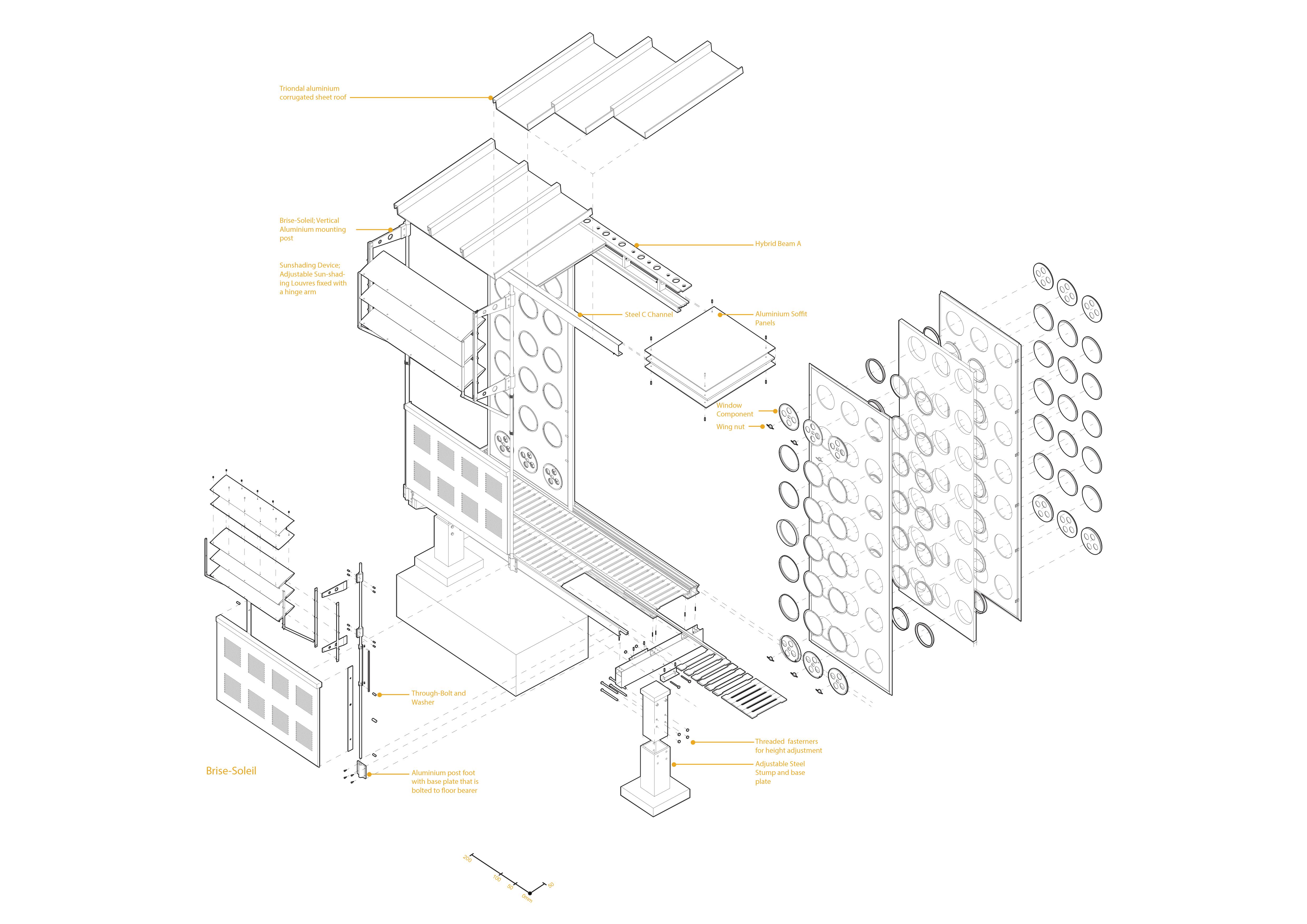

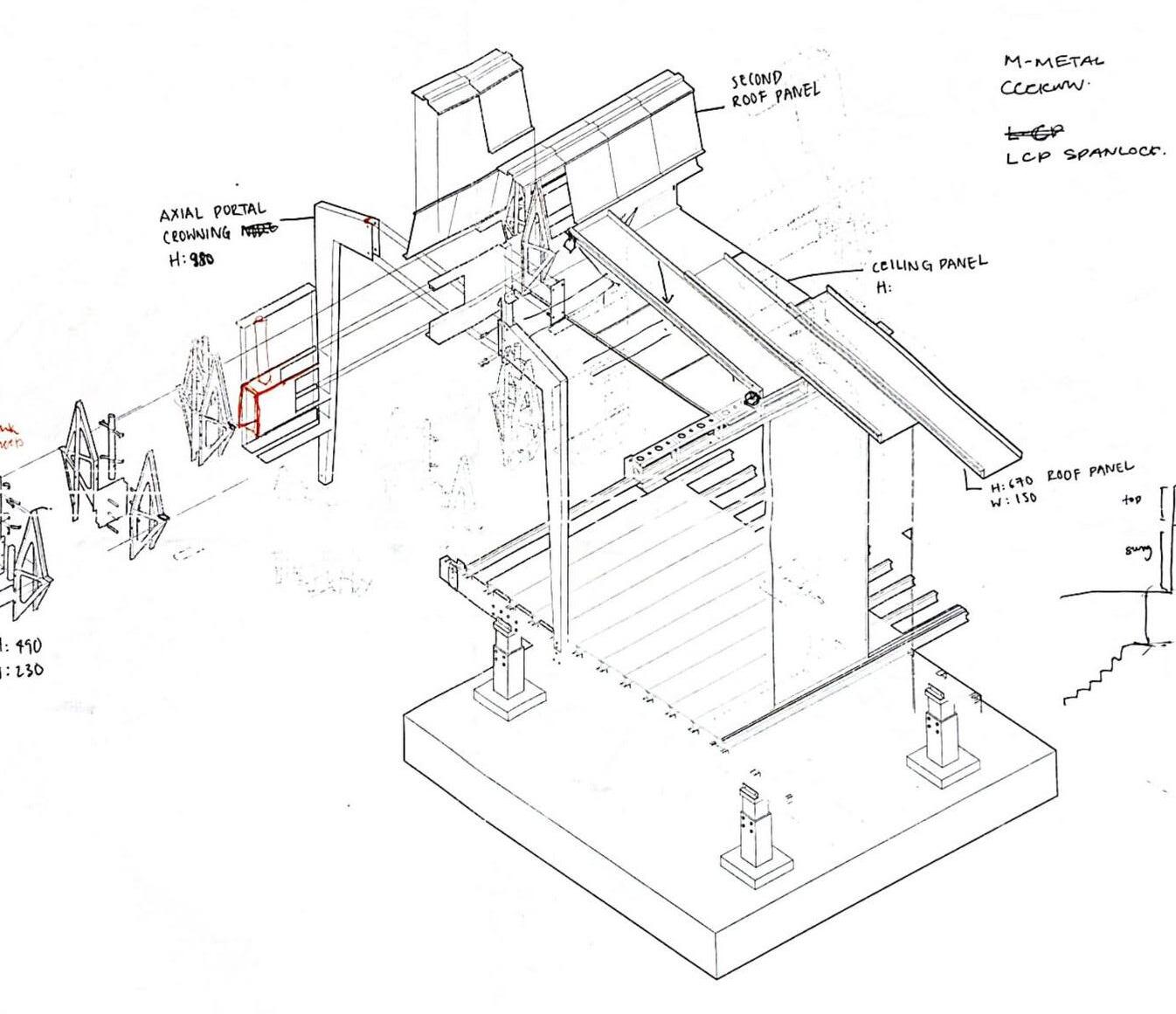

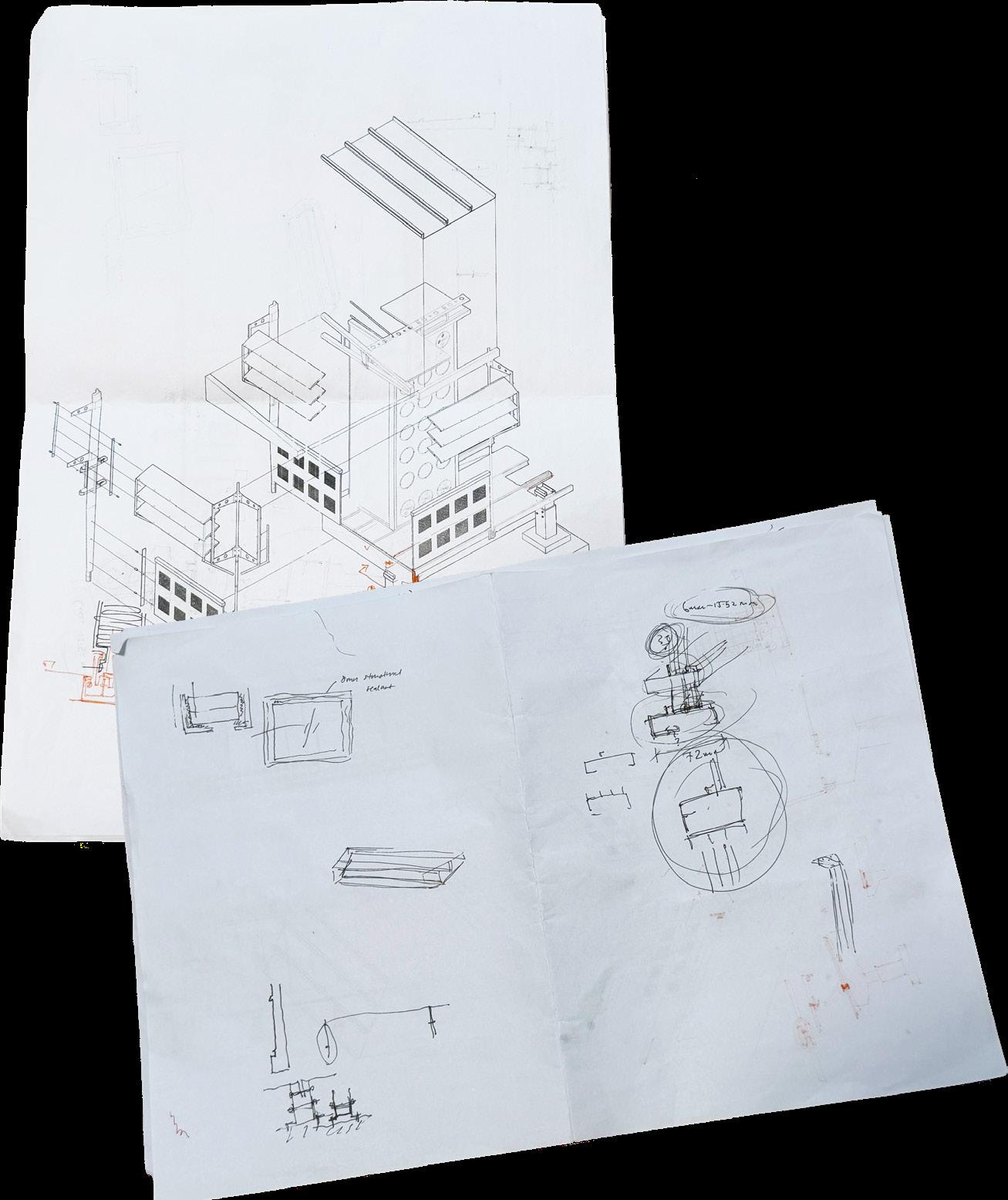

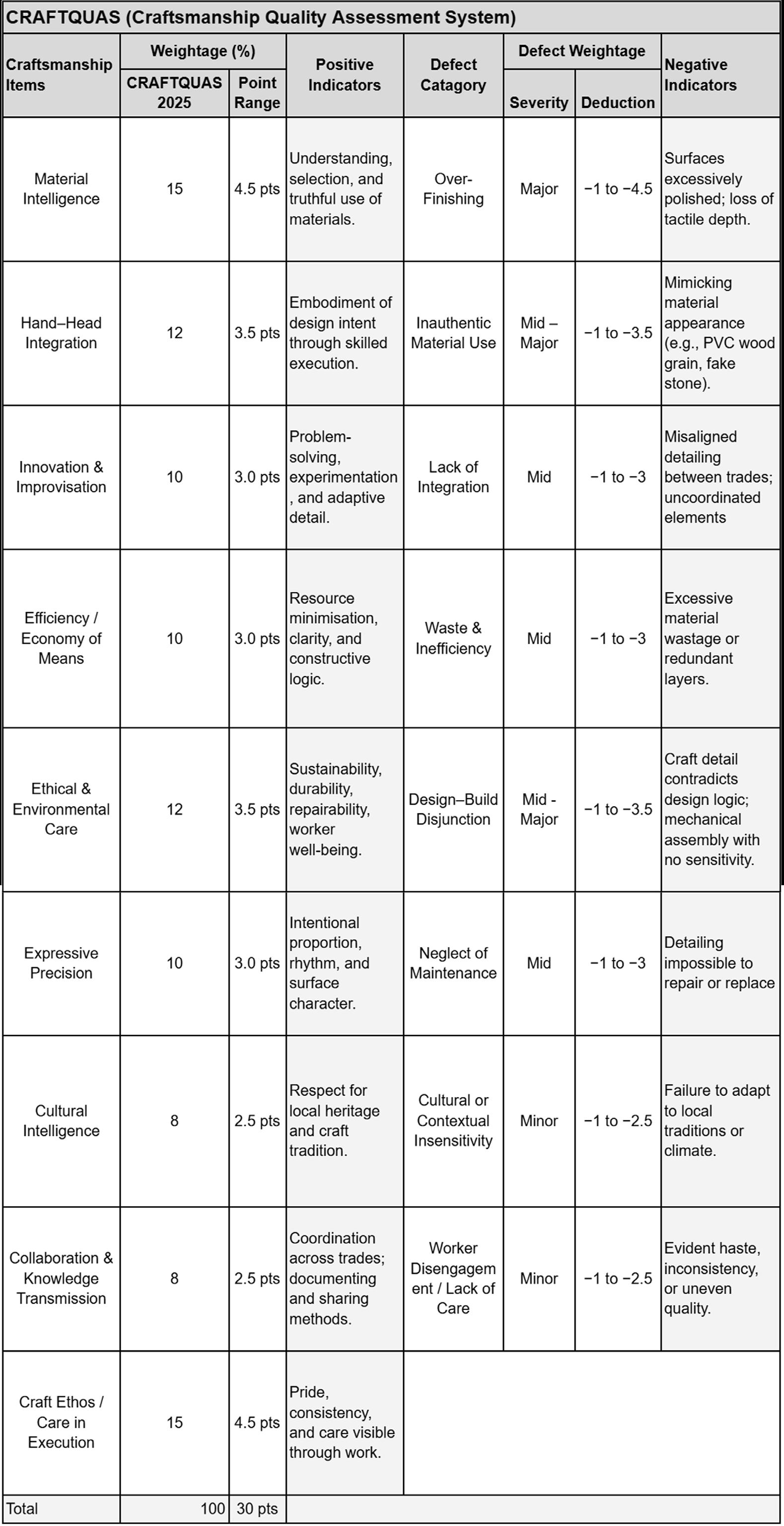

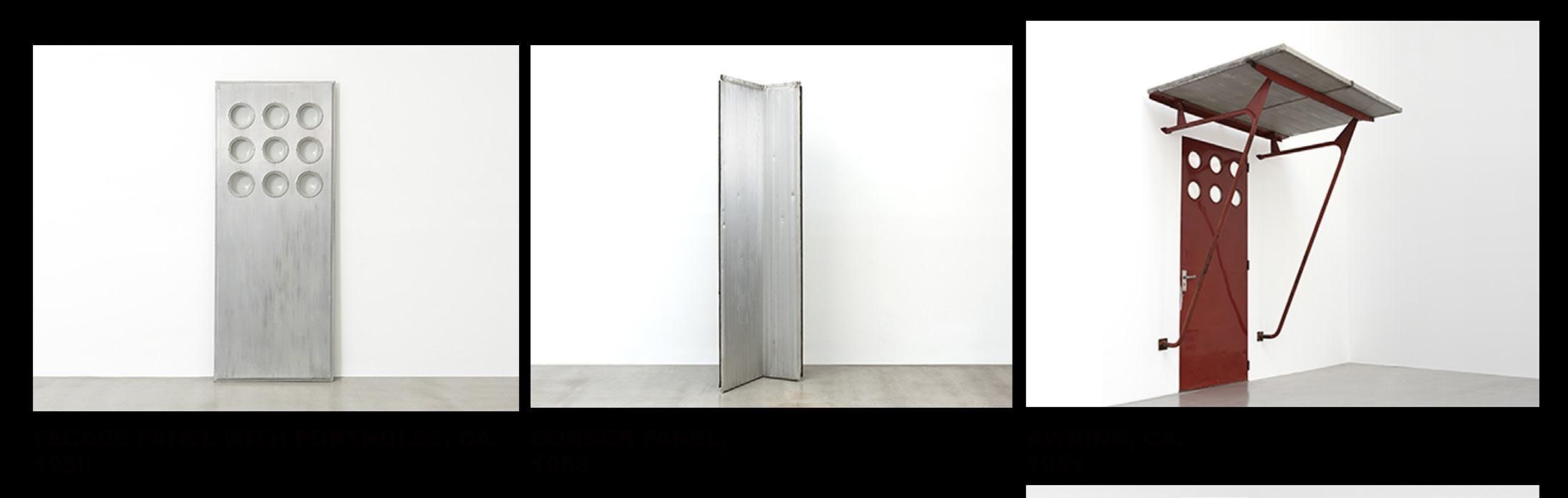

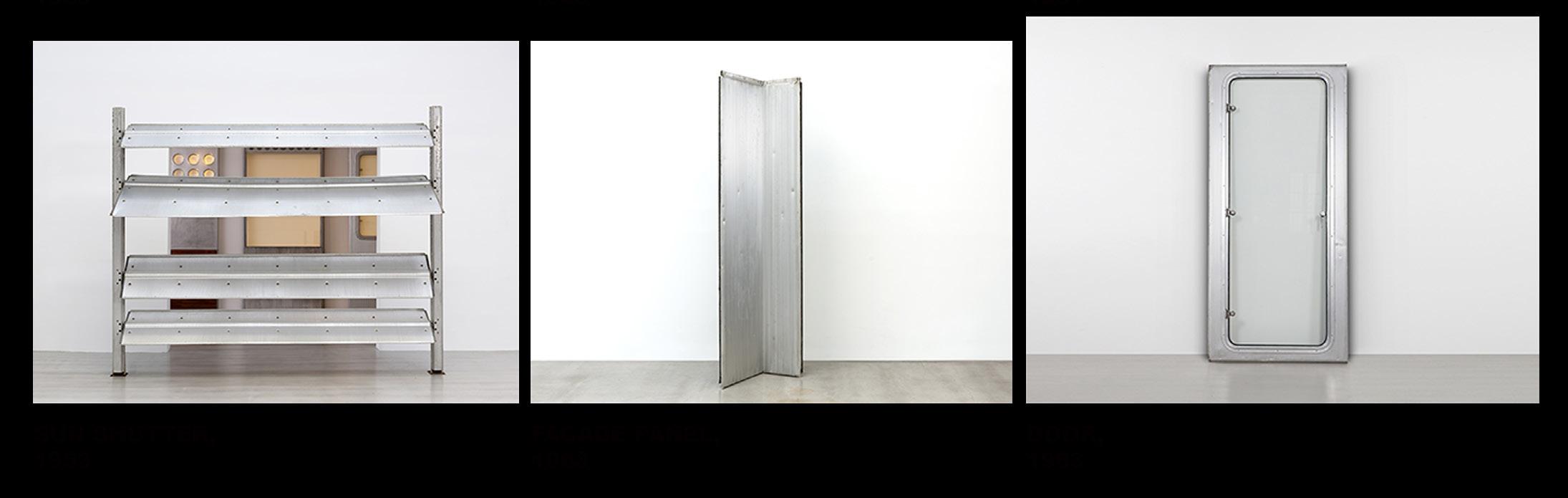

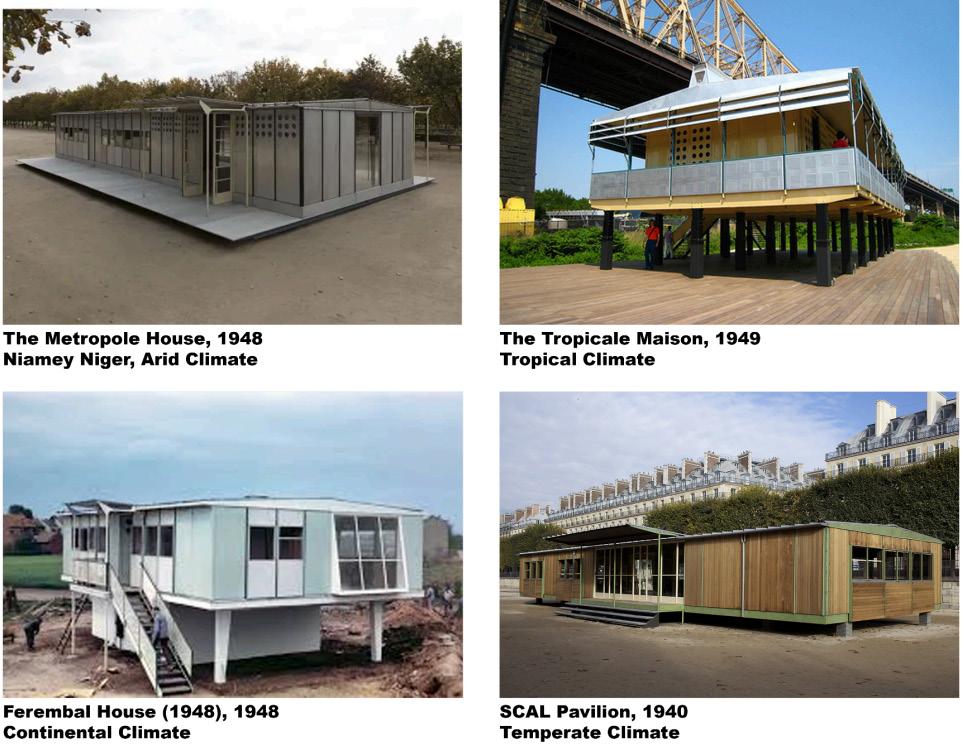

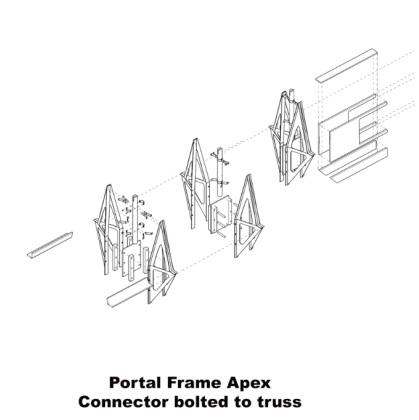

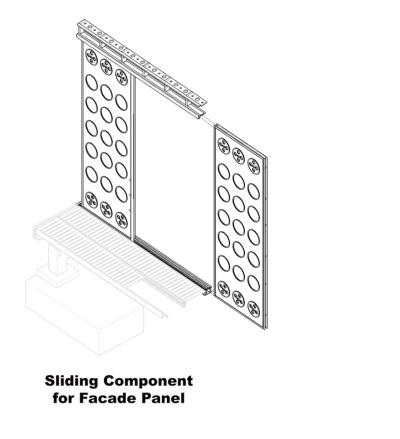

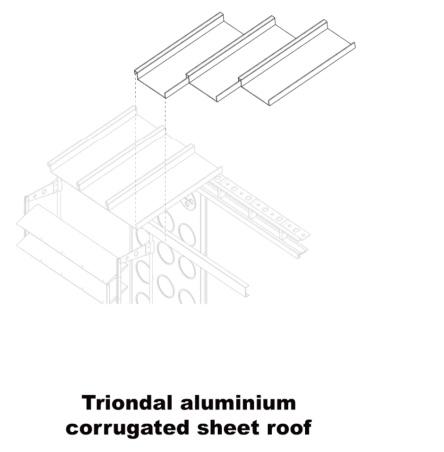

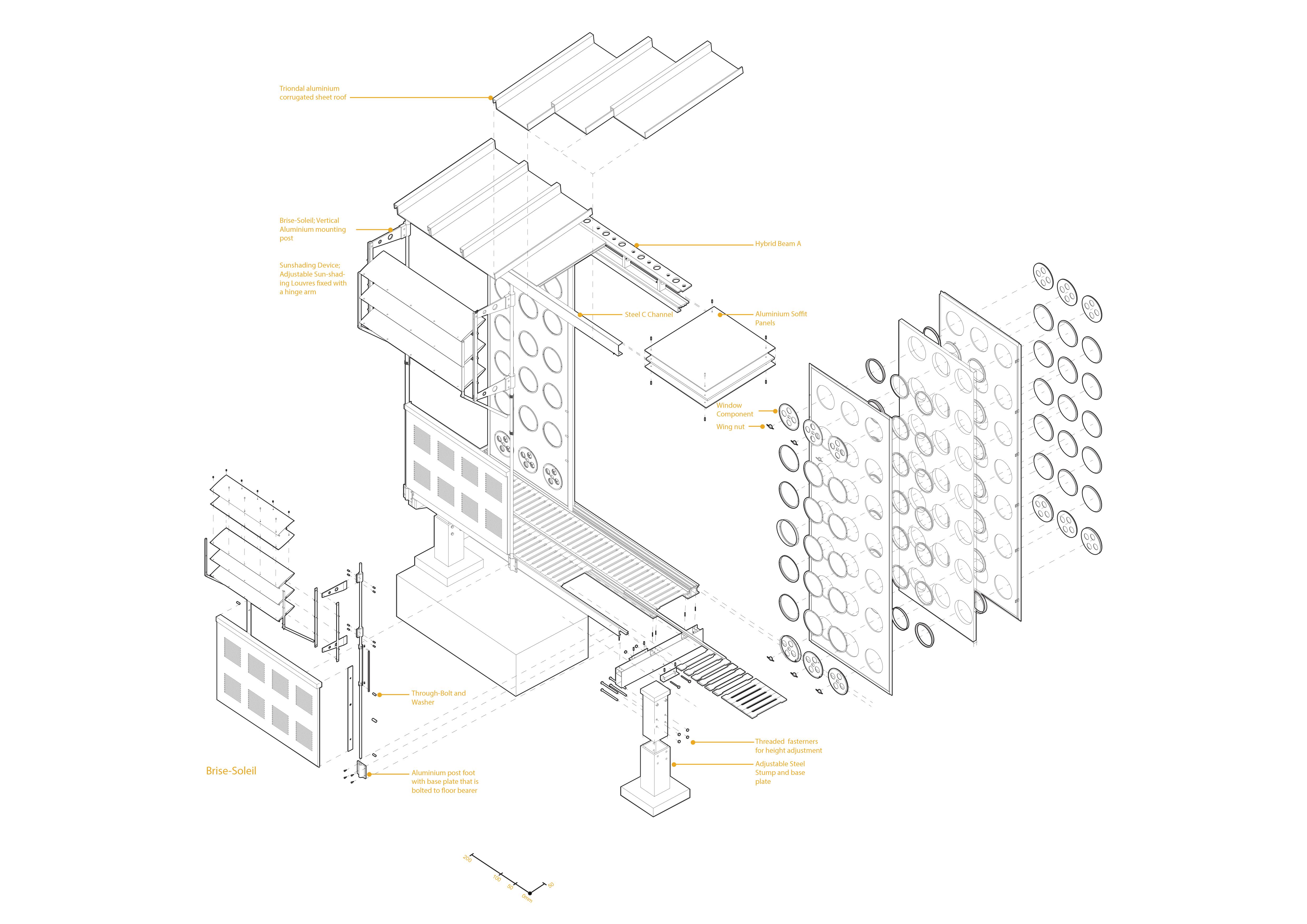

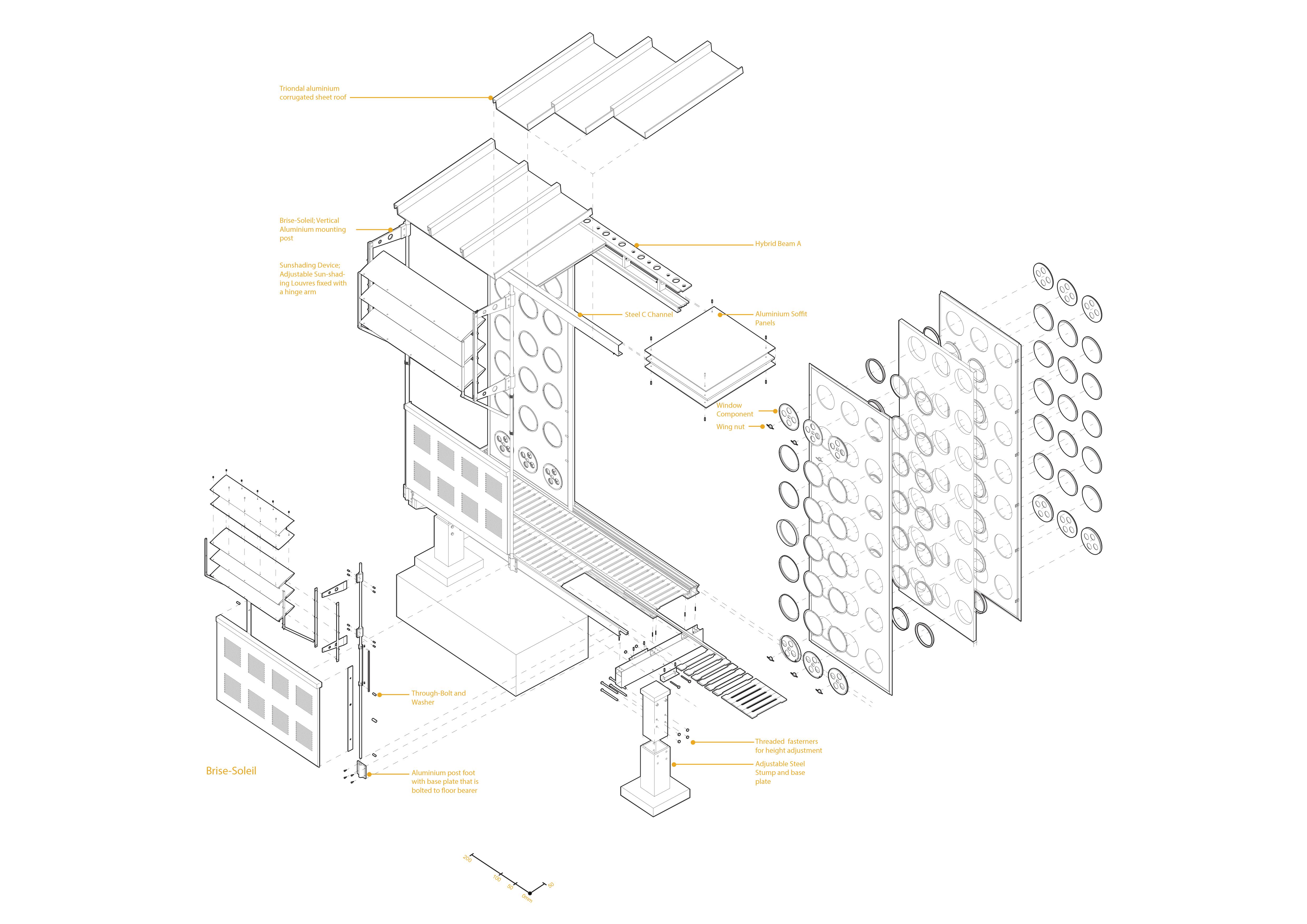

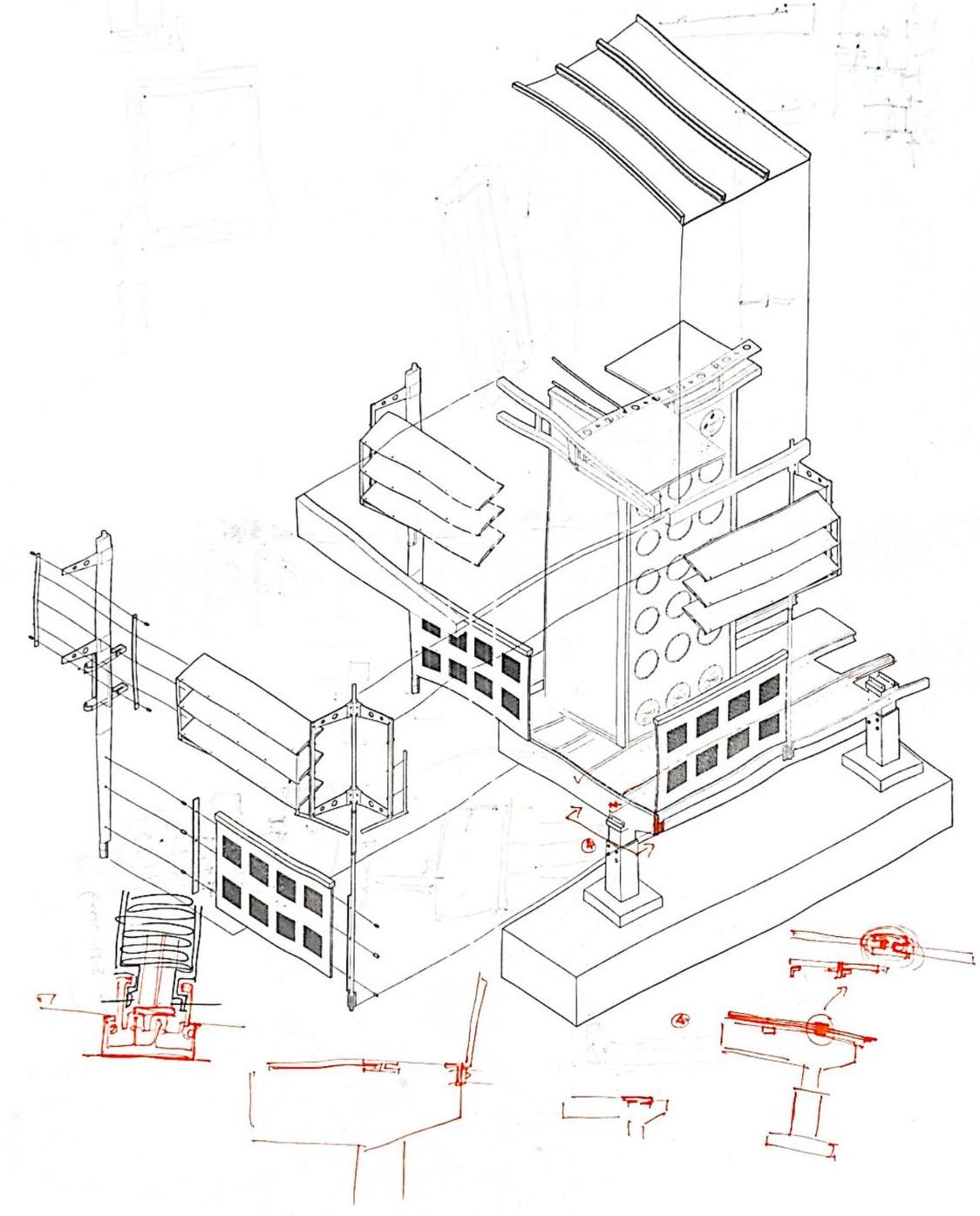

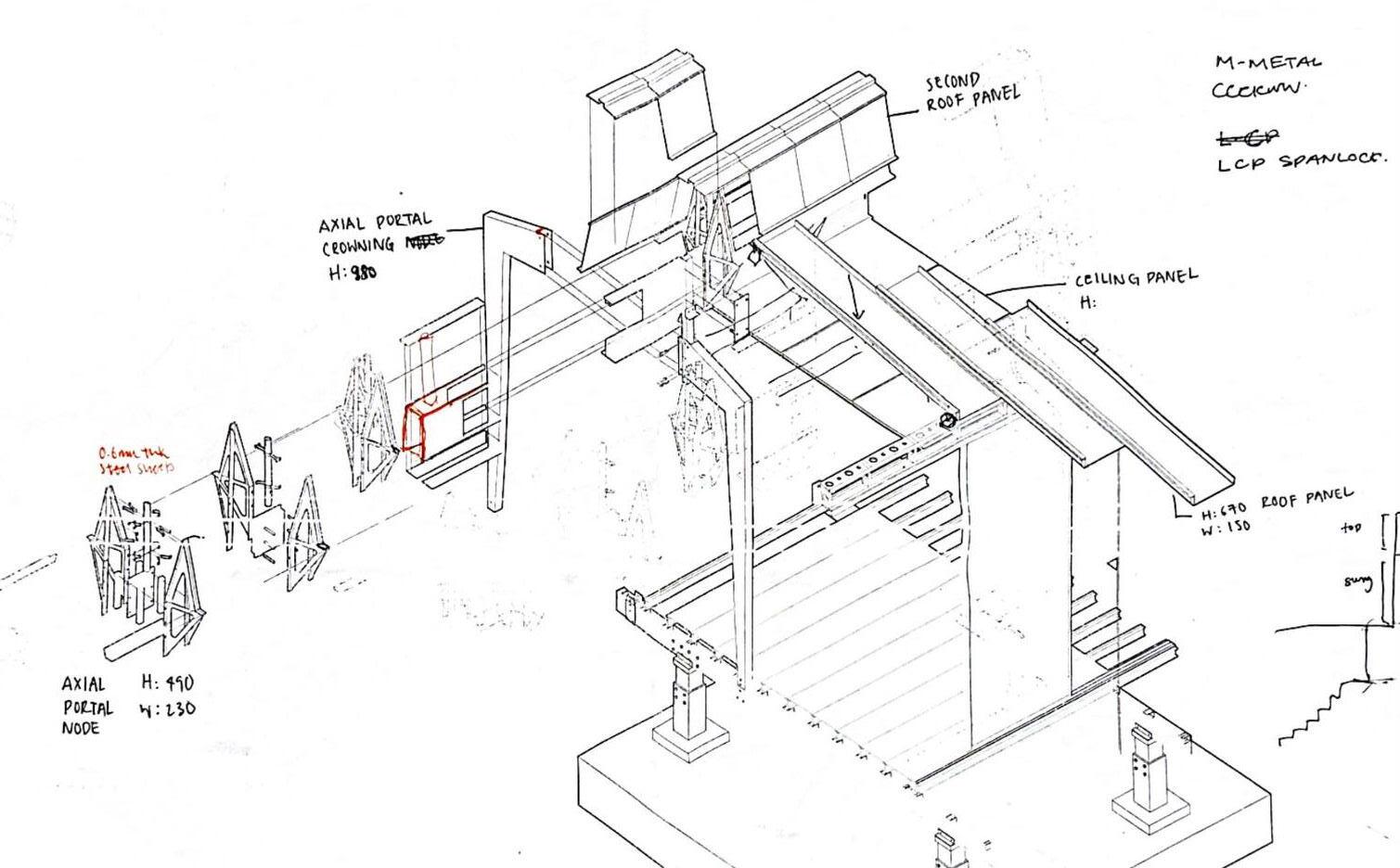

A key precedent examined in this thesis is Jean Prouvé, a metalworker and self-taught architect whose work redefined craftsmanship within the industrial age. His practice embodied an elegant synthesis between the artisanal and the mechanised, expressed through the precision of his metal joineries and the clarity of his tectonic logic. Prouvé’s patented 8×8 demountable axial portal frame system (1939) exemplified this synthesis—a kit-of-parts approach that balanced aesthetic refinement with industrial efficiency. Drawing from his early apprenticeship as a metalworker, Prouvé translated handcraft skill into machinic production, developing a universal system of connections applicable across his diverse series of demountable houses and pavilions. Each iteration, though distinct in form and scale, shared a consistent assembly logic that allowed for rapid on-site construction or disassembly, often within a day, enabling the structures to be flat-packed for transport and re-erection elsewhere.

Designed amid the exigencies of World War II, Prouvé’s prefabricated houses responded to the urgent need for efficient, replicable, and high-quality housing for displaced civilians and returning soldiers. Although the Tropicale Maison was never realised in France’s African colonies—largely due to cost and the incompatibility of its modernist aesthetic with local conditions—it remains an important expression of technical and conceptual innovation. The design’s craftsmanship is most apparent in its precise, adaptable joints, whose integrity has allowed surviving structures to remain operable decades later, repurposed as exhibition pavilions such as at Design Shanghai (2015). This enduring functionality underscores the durability and foresight of Prouvé’s construction logic.

18 : Demountable Houses Components | Source:

Across subsequent iterations, Prouvé refined his kitof-parts to accommodate different climatic and contextual conditions, expanding his material palette from steel and timber to composite panels, aluminium, and fibreglass. The universality of his jointing system—combined with its capacity for climatic adaptation—positions his work as an early exemplar of context-responsive prefabrication.

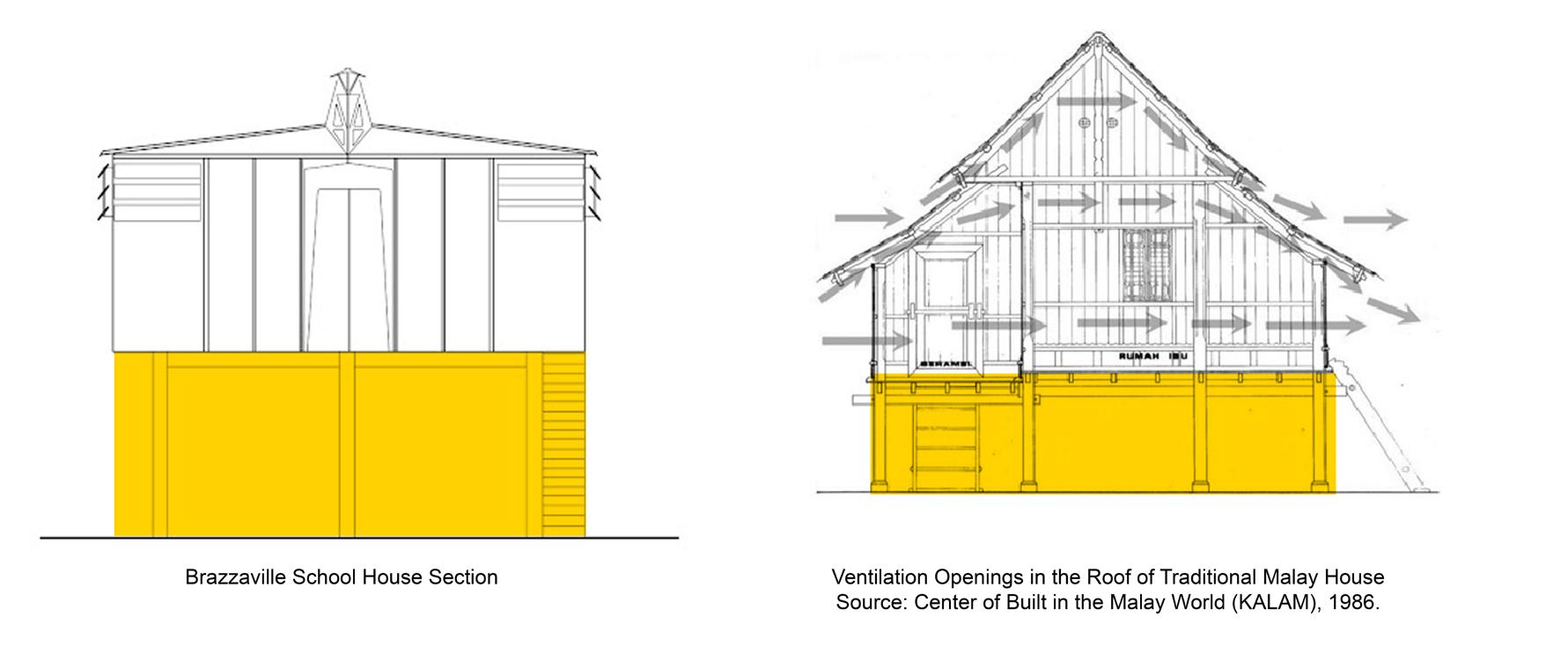

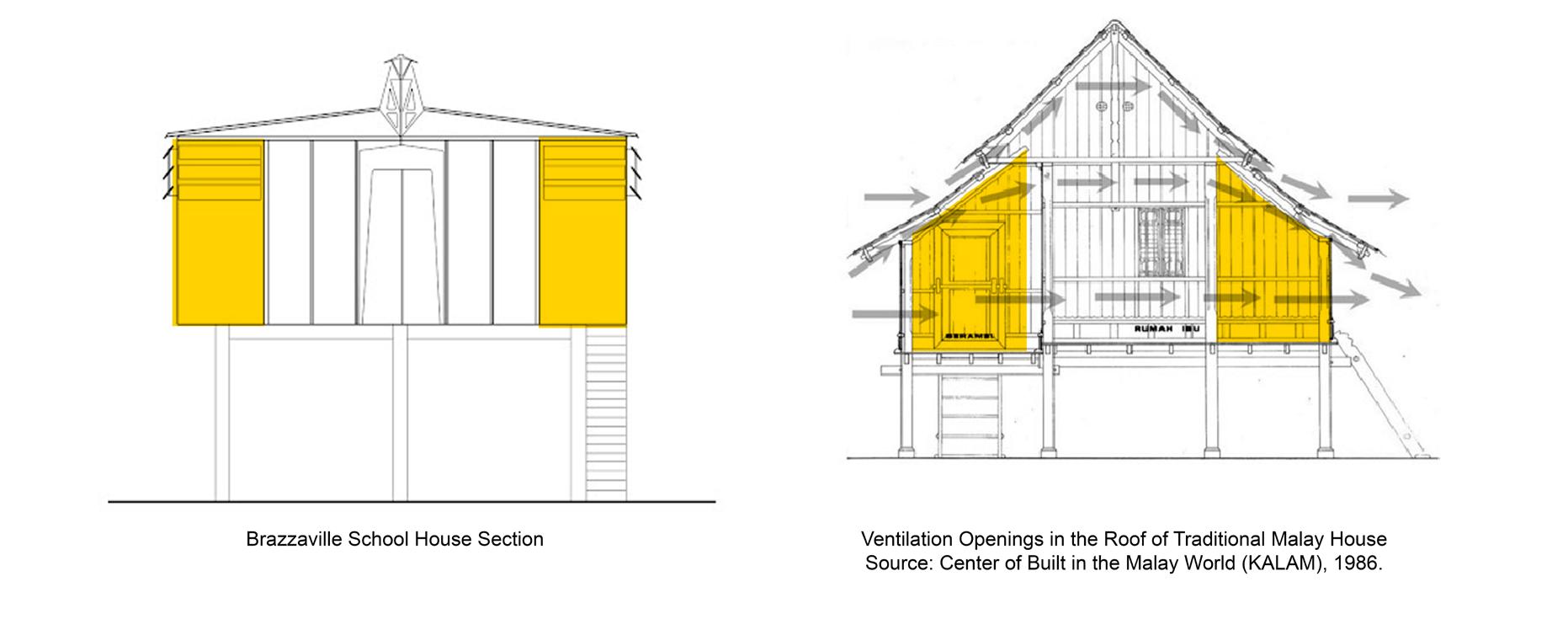

This thesis situates the Tropicale Maison Brazzaville in comparative dialogue with the Rumah Panggung, a vernacular raised timber house found across Southeast Asia, to examine how Prouvé’s modernist modularity may have drawn conceptual inspiration from indigenous principles of elevation, ventilation, and joinery, while simultaneously asserting his own kit-of-parts logic that foregrounds the visibility of construction, material honesty, and climatic responsiveness—qualities central to the criteria of architectural craftsmanship established in this study.

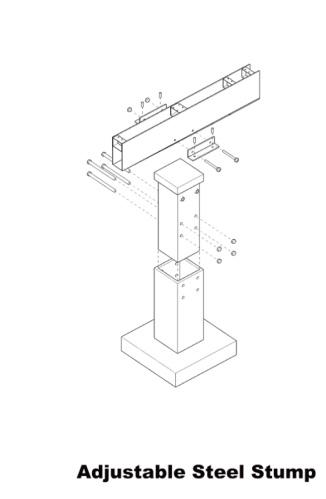

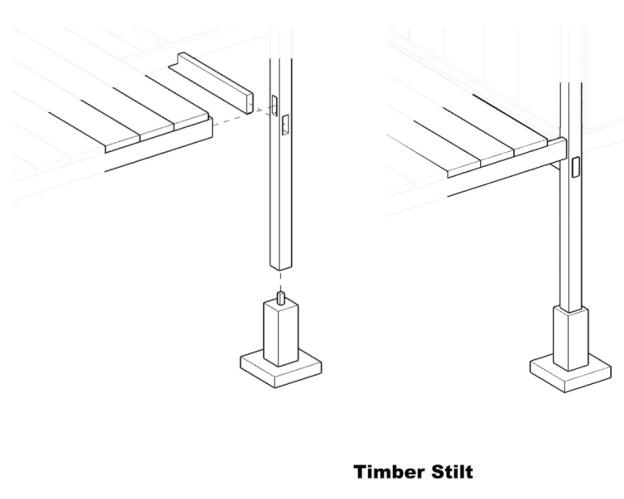

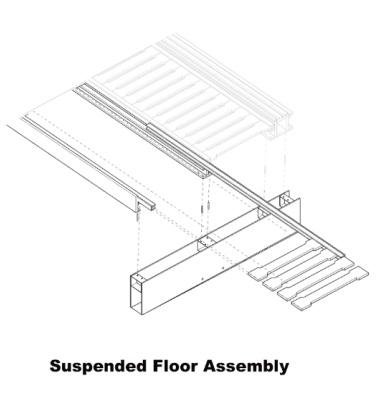

Elevated Structure

Elevating the home above ground level helps with ventilation under the floor, protects against flooding, and allows the house to be sited on sloped or uneven terrain, especially in tropical humid terrains.

Double Roof Structure:

The double roof and high roof height in both designs allows for stack effect to occur, where the hot air that rises can escape through the top of the ventilation.

Concrete stilts or adjustable steel columns

Timber stilts used to elevate the house ventilation, flood protection, and pest control.

At the axia portal crowning joint—where the roof ridge meets the primary structural portal frame—details were engineered to leave functional air gaps in the second roof that enhance this stack ventilation effect

The steeply pitched or layered roof allows hot air to rise and escape, reducing heat transfer to the living spaces below.

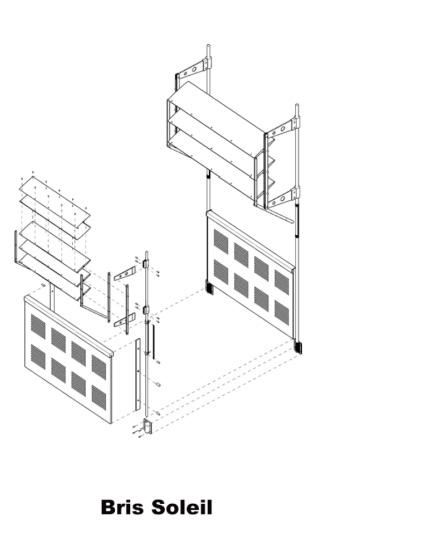

Sun-Shading Device and Veranda

Sunshading devices and verandas aid to mitigate heat gain from tropical sunlight, hence improving indoor comfort and reducing reliance on mechanical cooling.

The veranda is surrounded by adjustable aluminum sun-screens (brise-soleil), which reflect sunlight and create a shaded buffer zone around the house, reducing solar heat gain and glare.

Use wide eaves, verandas, and openable windows or louvres to maximise shade and airflow.

Through these instances, it is evident that Jean Prouvé understood the principles underlying the construction methods employed by local communities living in tropical climates. Consequently, he formalised these principles into the built form of the Maison Tropicale, ensuring its climatic responsiveness. There is a clear intention to replicate the same system and assembly knowledge across all his dismountable home series, with the portal frame apex joint component being the only unique addition in the Maisons Tropicales series to maintain occupant comfort.

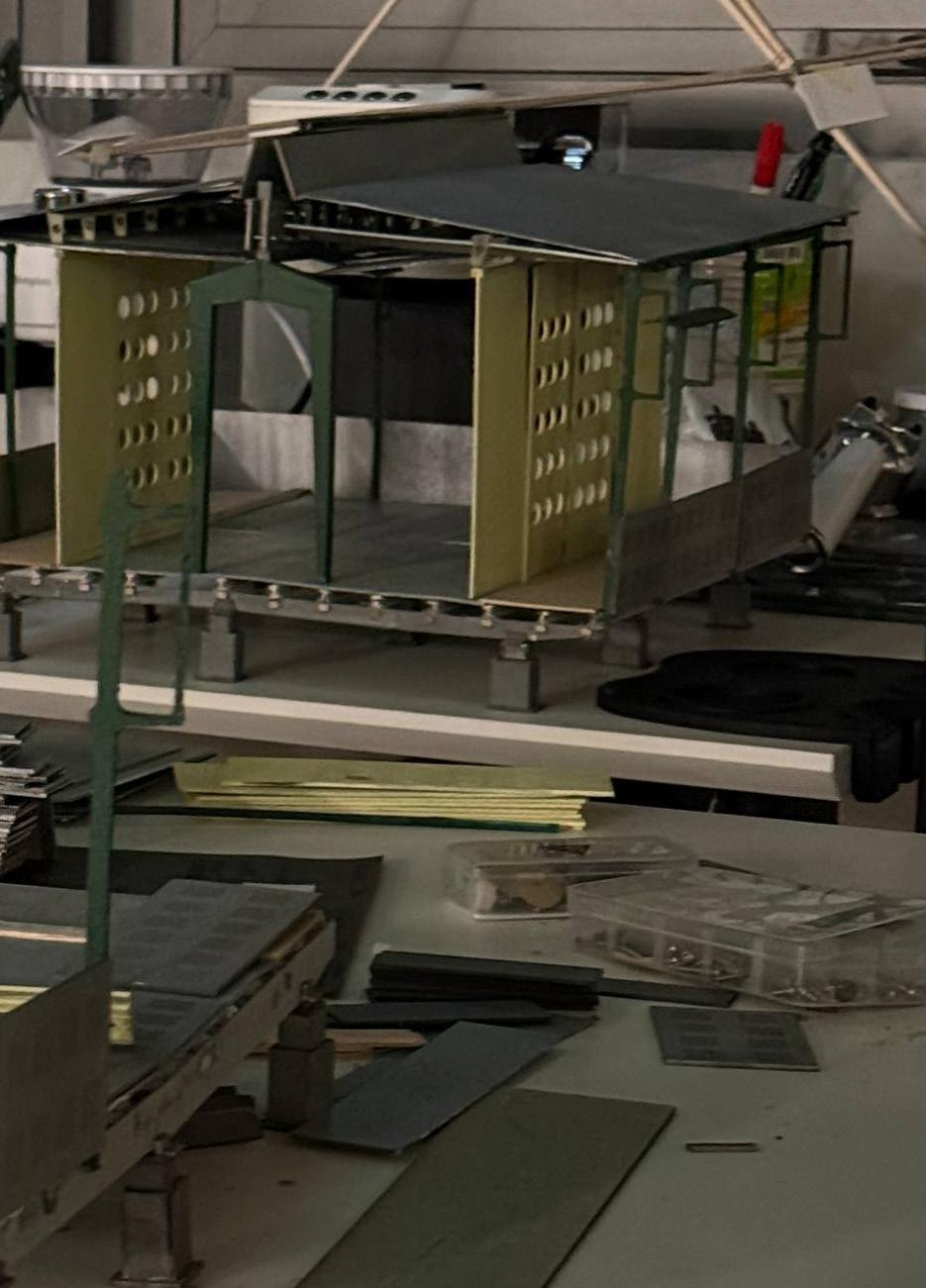

Rumah Singapura Series

Steel and Alumnium

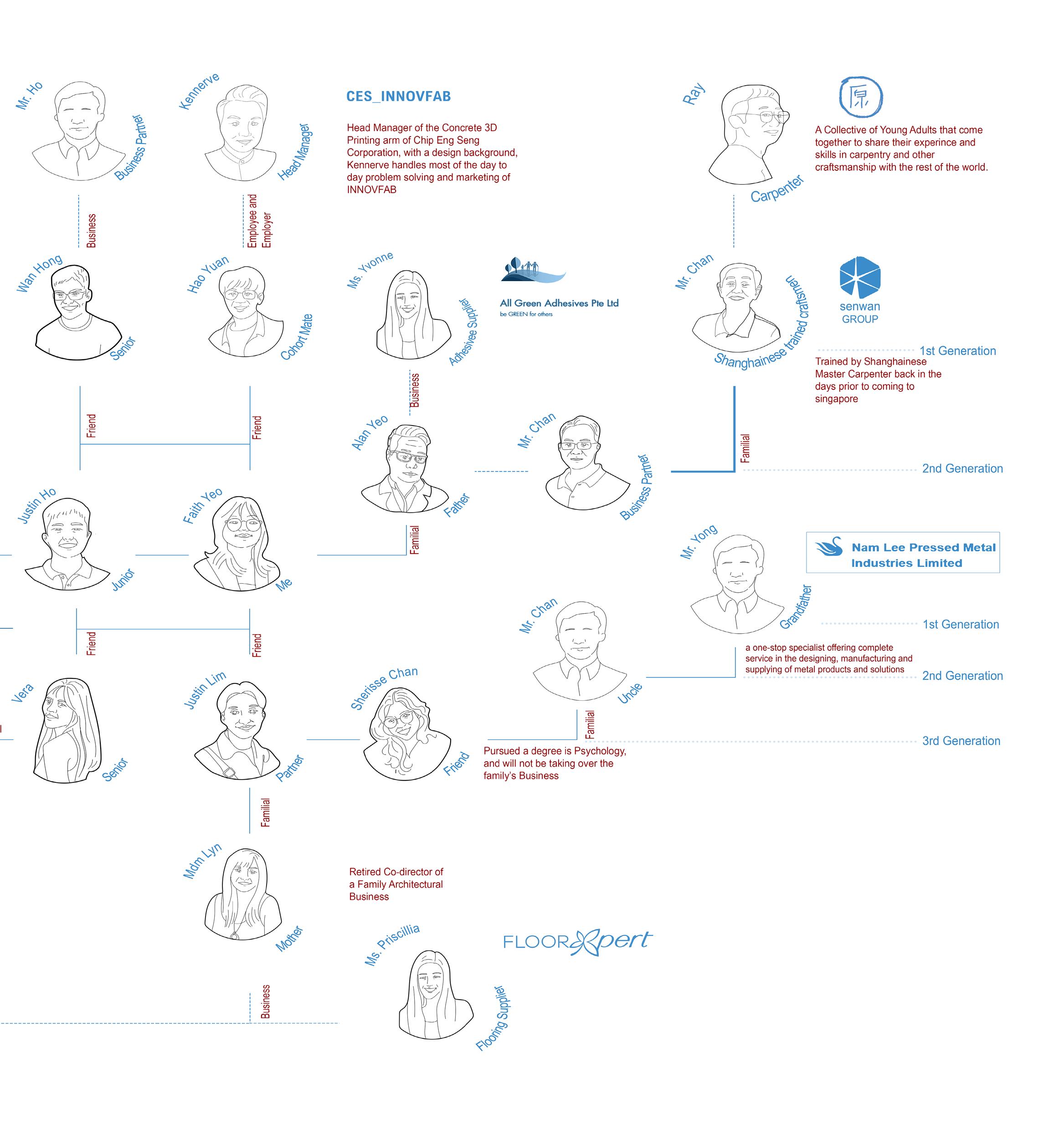

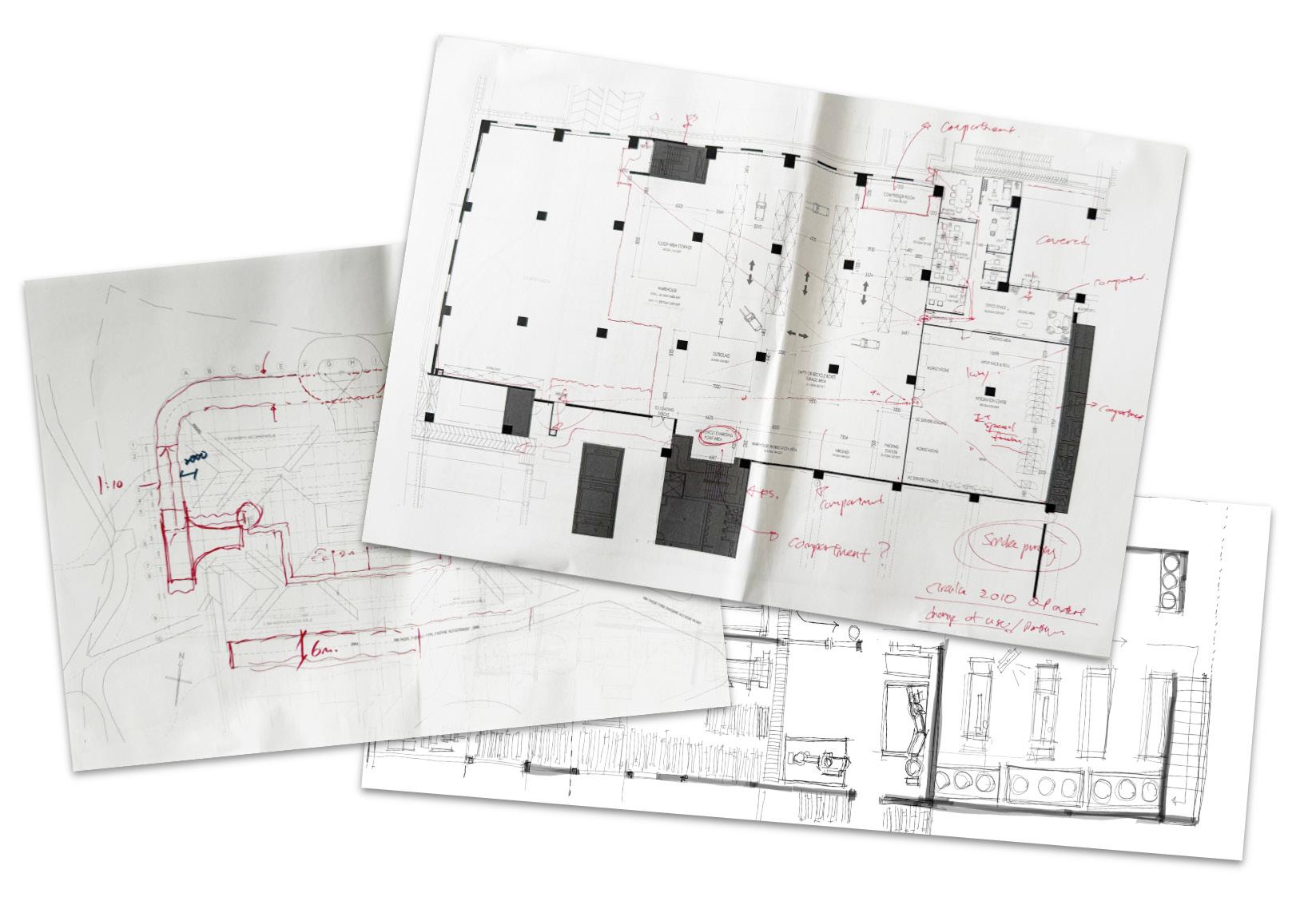

To supplement our interview findings on steel and aluminium sourcing and fabrication with manufacturers THI and Rowell Metals, it is evident that Singapore possesses the industrial capacity to mass-produce existing components or customise new ones. However, feasibility depends heavily on project scale, budget, and timeline.

This was further clarified in consultations with SC Solutions, a smaller firm specialising in engineering, architectural coordination, and steel/aluminium fabrication. Discussions with Mr. Teo and Mr. Yeo confirmed that replicating every component of the Tropicale Maison Brazzaville is entirely possible, albeit with adjustments to joineries aimed at simplifying assembly and reducing labor intensity. Notably, Prouvé’s unique modular joinery system—integral to the demountable home’s assembly—is not customary in Singapore’s manufacturing sector. Consequently, producing these specialized components would require sufficient demand or volume to justify fabrication.

Therefore, to explore how craftsmanship can evolve and retain relevance within Singapore’s typical constraints of cost, time, and project scale, the study proposes to recreate a local adaptation of the Tropical Maison Brazzaville—termed Rumah Singapura—using standard, readily available components. This approach aims to balance craftsmanship with practical production realities in the local context.

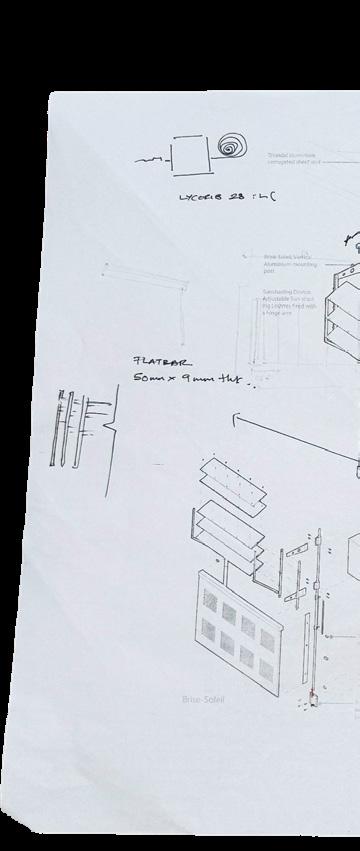

Fig. 22 : Drawings used in Consultations with

The investigation into machine craftsmanship within Singapore’s construction industry reveals complexities that challenge both the education and ethical responsibilities of architects. This process highlights the evolving transmission of craftsmanship—from traditional local communities, through foreign labor, and now increasingly to mechanised processes. The realities of the contemporary industry and global market often stand in stark contrast to the architect’s aspiration for unique, bespoke design; instead, mass production is prioritised to make construction more affordable and efficient for consumers. Consequently, this paradigm tends to restrict true craftsmanship to those who can afford specialised skilled labor, thereby monopolizing opportunities for meaningful design authorship.

Jean Prouvé’s dismountable house series offers a pertinent case study, demonstrating that mass-produced homes can be adapted to express individual identity and respond to climatic needs. These dwellings utilize a replicable kit-of-parts for construction and modularity, facilitating ease of expansion and enabling affordable, efficient mass production. By proposing a universal joinery manual and adaptable kit-of-parts that leverages readily sourced materials in Singapore and supports customisation, this thesis aims to challenge the existing bottleneck in craftsmanship. Such an approach advocates for a future where robust craftsmanship practices not only persist but flourish amid increasing mechanisation and standardisation in the built environment.

24 : Byproduct of the Consultations

25 : Byproduct

1 Mary N. Woods, From Craft to Profession: The Practice of Architecture in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999). p.25.

2 Kenneth Frampton, “Rappel à l’ordre: The Case for the Tectonic,” in Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965–1995, ed. Kate Nesbitt (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), p.516–528.

3 Jeremy Till, Architecture Depends (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), p. 156

4 Jeremy Till, Architecture Depends (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), p. 178-179.

5 Business Times, “Singapore’s migrant labour dilemma deepens as costs rise,” October 3, 2025.

6 Straits Times, “S’pore population now at 6.11 million, with 1.2% rise due to more construction workers and maids,” September 29, 2025.

7 Building and Construction Authority (BCA), “Building Control (Buildability and Productivity) Regulations.” Last modified August 2, 2024. https://www1.bca.gov.sg/buildsg/productivity/buildability-buildable-design-and-constructability/building-control-regulations.

8 Population in Brief 2025, National Population and Talent Division (NPTD), Singapore, September 29, 2025

9 Building and Construction Authority (BCA). “Cities of Tomorrow R&D Programme – 1st Grant Call.” Singapore: Building and Construction Authority, 2018. https://www1.bca.gov.sg/docs/default-source/docs-corp-buildsg/buildsg-transformation-fund/grant_call_1.pdf.

10 Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 9, 51.

11 Tim Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture (London: Routledge, 2013), p.5–6, 21–23.

12 Kenneth Frampton, “Rappel à l’ordre: The Case for the Tectonic,” in Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965– 1995, ed. Kate Nesbitt (Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 516–528.

13 Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture, trans. Frederick Etchells (New York: Dover Publications, 1986); see also “A House Is a Machine for Living In,” OpenLearn - The Open University, last modified November 25, 2001, https://www. open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/heritage/le-corbusier.

14 Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).

15 Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture, trans. Frederick Etchells (New York: Dover Publications, 1986); Kenneth Frampton, “Rappel à l’ordre: The Case for the Tectonic,” in Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965–1995, ed. Kate Nesbitt (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 516–528.

Building and Construction Authority (BCA). Cities of Tomorrow R&D Programme – 1st Grant Call. Singapore: Building and Construction Authority, 2018. https://www1. bca.gov.sg/docs/default-source/docs-corp-buildsg/buildsg-transformation-fund/ grant_call_1.pdf.

Building and Construction Authority (BCA). CONQUAS®: The BCA Construction Quality Assessment System. Last revised April 30, 2020. Singapore: Building and Construction Authority, 2017.

Building and Construction Authority (BCA). CONQUAS®: The BCA Construction Quality Assessment System. Last revised April 30, 2020. Singapore: Building and Construction Authority, 2017.

Building and Construction Authority (BCA). “Building Control (Buildability and Productivity) Regulations.” Last modified August 2, 2024. https://www1.bca.gov. sg/buildsg/productivity/buildability-buildable-design-and-constructability/ building-control-regulations.

Corbusier, Le. Towards a New Architecture. Translated by Frederick Etchells. New York: Dover Publications, 1986.

Frampton, Kenneth. “Rappel à l’ordre: The Case for the Tectonic.” In Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965–1995, edited by Kate Nesbitt, 516–528. Princeton Architectural Press, 1996.

Herres, Ulrich M. “Craftsmanship in Architecture.” Revista Lusófona de Arquitectura e Educação (2014).

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Rout ledge, 2013.

Pye, David. The Nature and Art of Workmanship. London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1968.

Sennett, Richard. The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Till, Jeremy. Architecture Depends. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

Vitruvius Pollio. Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Morris H. Morgan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914.

Woods, Mary N. From Craft to Profession: The Practice of Architecture in NineteenthCentury America. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999.

“Everything You Need to Know About the New HDB BTO White Flats.” HomeTrust SG. Accessed November 7, 2025. https://www.hometrust.sg/articles/all-you-needto-know-about-the-new-hdb-bto-white-flats/.

“‘White Flats’: The New HDB Housing Type That’s Redefining Resale and Interior Design.” Channel NewsAsia. Accessed November 7, 2025. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/hdb-white-flats-resale-interi or-designers-4368151.

Image Credits

Cover Page : Yeo, Faith

Fig. 01 : Meinhard von Gerkan. Photograph. ©floornature.com. Accessed November 7, 2025.

Fig. 02 : Yeo, Faith, Photography of the Visual Communications between my Internship Supervisor and I, 2024

Fig. 03 : Yeo , Faith, Diagram of History of Vocational Work in Singapore, 2025.

The Straits Times. “3D-printed features to debut in Tengah, Bidadari estates.” Photo by Alphonsus Chern. September 16, 2019.

Ministry of Education, Singapore. Applied Study in Polytechnics and ITE Review (ASPIRE) Report. August 2014.

Institute of Technical Education Singapore. “Reliving ITE’s Transformation.” 2012.

National Archives of Singapore. “Students at ITE Vocational Institute workshop.” Photograph, 1986.

Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA). “Singapore Vocational Institute (Workshop Block), Balestier Road.” Photograph, 1965.

Fig. 04 : Yeo, Faith, Photography of Marble and Granite Express Factory. 2025

Fig. 05 : Yeo, Faith, Photography of Printing of Prefabrication Bathroom Unit (PBU), 2025

Fig 06 : Yeo, Faith, Photography of Sen Wan Timber CNC Machine, 2025

Fig. 07 : Yeo, Faith, Diagram of Tracking Traces of Craftsmanship Expertise, 2025.

Fig. 08 : Yeo, Faith, Diagram of Sen Wan Timber Factory Workflow, 2025.

Fig. 09 : Yeo, Faith, Photography of Craftsmen at THI Pte Ltd, 2025.

Fig. 10 : Yeo, Faith, Photography of Craftsmen at Sen Wan Timber Pte Ltd, 2025

Fig 11 : HL-Sunway JV. HL-Sunway Prefab Hub, Singapore. Photograph. In TradeLink Media. Accessed November 7, 2025.

Fig 12 : Yeo, Faith, Speculative Table of Architectural Assessment Criteria, 2025

Fig 13 : Yeo, Faith, Speculative Table of Architectural Craftmanship Grading, 2025.

Fig 14 : Yeo, Faith, Speculative Table of Architectural Craftmanship Grading, 2025.

Fig 15 : Galerie Patrick Seguin. “Jean Prouvé: Demountable House Installation at Gagosian, Le Bourget.” YouTube video, 1:49. June 10, 2013.

Fig 16 : Galerie Patrick Seguin. “Jean Prouvé: Facade Panels, Sun Shutters, Doors, and Awnings.” Accessed November 7, 2025.

Fig 17 : Galerie Patrick Seguin. “Jean Prouvé: Series of Demountable Houses.” Accessed November 7, 2025.

Fig 18 : Yeo, Faith, Diagram of Architectural Comparisons Tropical Maison and Rumah Panggung, 2025

Fig 19 : Yeo, Faith, Diagram of Architectural Comparisons Tropical Maison and Rumah Panggung, 2025

Fig 20 : Yeo, Faith, Drawings used in Consultations with SC Solutions, 2025.

Fig 21 : Yeo, Faith, Drawings by product of Consultations with SC Solutions, 2025.

Fig 22 : Yeo, Faith, Drawings by product of Consultations with SC Solutions, 2025.

Fig 23 : Yeo, Faith, Drawings by product of Consultations with SC Solutions, 2025.

Self-Disclosure of Research

I certify that except where due acknowledgement has been made, the work is that of the author alone; the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; the content of the project is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program, any editorial work, paid or unpaid carried out by a third party is acknowledged, ethics procedures and guidelines have been followed.

Intellectual Property Rights are retained by Faith Yeo Xin Yi Veronica,who asserts moral rights and all other rights to be identified as the author of this work. I have acknowledged all copyright holders on the images and other references used.

Self-disclosure on Usage of Ai-Assisted Tools

During the preperation of thiis work, I have used Ai-assisted Tools for the sole purpose of paraphrasing and English enhancement only. After using the tool/service, I reviews and editted the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.