INFUSION

Volume 18

Infusion

Volume 18

Infusion aims to capture the diversity of the Fulbright Korea experience by publishing work from Fulbright Korea Senior Scholars, Junior Researchers, English Teaching Assistants and program alumni. We support artists in the creation of work which honestly engages with their grant year and their craft. The Fulbright Program aims to increase mutual understanding between the people of the United States and other countries through cultural and educational exchanges.

Cover Photo: Cherry Blossom Season, Chris Jang, Naju, Jeollanam-do

Artwork: Grace Turley and Francesca Duong

Table of Contents

Magazine Staff

Letter from the Director

Letter from the Embassy

Letter from the Editor

Celebrating 75 Years of Fulbright Korea

When Silence Speaks, Kavya Kumaran

Dandelion, Henley Verhagen

Glimpses of Summer, Laura Evans

Introducing, Changwon, Marissa Harrold

The Forgetting, Rose Nelson

Oranges/Snow, Solveig Asplund

From Seoul to Jeju: Meals Worthy of a Journey, Michelle Wei

Sammy Seung-Min Lee: “Fulbright Wasn’t Just a Chapter — it Was a Hinge,” Eden Perez Bonilla

In Korea, I Try Talking to My Ancestors; I Only Hear Physics, Gabriella Son

Continuum, Jena Mehl

Student Competition

Magazine Staff

Kate Refolo

Francesca Duong

Heidi Little

Pearl Cook

Maddie Stokes

Dereka Thomas

Daniel Salgado-Alvarez

Lili Chey-Warren

Declan Mazur

Pey Straubel

Laura Evans

Eden Perez Bonilla

Grace Turley

Colleen Rhein

Editor-in-Chief:

Literary Managing Editor:

Lifestyle Managing Editor:

Design Editor:

Literary Staff Editors:

Lifestyle Staff Editors:

Monitors:

Web Editor:

Social Media Coordinator:

Publication Coordinator:

Francesca Duong (3rd Year ETA), Seoul, Seoul

Declan Mazur (2nd Year ETA), Busan, Busan

Grace Turley (3rd Year ETA), Naju, Jeollanam-do

Kate Refolo (3rd Year ETA), Seoul, Seoul

Maddie Stokes (1st Year ETA), Cheongju, Chungcheongbuk-do

Dereka Thomas (1st Year ETA), Cheongju, Chungcheongbuk-do

Pearl Cook (1st Year ETA), Cheongju, Chungcheongbuk-do

Daniel Salgado-Alvarez (1st Year ETA), Pohang, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Eden Perez Bonilla (2nd Year ETA), Jeongeup, Jeollabuk-do

Colleen Rhein (2nd Year ETA), Mokpo, Jeollanam-do

Pey Straubel (1st Year ETA), Jinju, Gyeongsangnam-do

Laura Evans (2nd Year ETA), Geoje, Gyeongsangnam-do

Lili Chey-Warren (1st Year ETA), Gyeongsan, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Heidi Little (Fulbright Program Staff ), Seoul, Seoul

Letter from the Director

It is my pleasure and privilege to congratulate this year’s Infusion team on the publication of a wonderful collection of works highlighting the diverse experiences that uniquely shape the lives of Fulbright participants in Korea. The featured essays, poems, photos and artwork represent the full spectrum of the Fulbright experience, from the exhilaration of discovering new cultures to the fear of stepping outside our own comfort zones. Through it all, we are enriched with a deeper understanding of the bigger, broader world.

Each morning as I enter the Fulbright offices, I walk by a bronze bust of Senator J. William Fulbright that was generously commissioned by the Korea Fulbright Alumni Association. On the base of the bust are etched the following words from Senator Fulbright, “It is possible… that people can find in themselves, through intercultural education, the ways and means of living together in peace ”. In these turbulent and uncertain times, when interactions with each other are often shaped by seemingly irreconcilable differences, these prescient words serve as a reminder that mutual understanding built through shared experiences can transform differences from points of conflict to points of curiosity and exploration.

The need to move away from conflict and toward curiosity has been particularly true for Korea as, just two months after the governments of the United States and Korea signed an agreement to support educational exchange in April 1950, laying the foundation for Fulbright Korea, the Korean War broke out. This year, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of this landmark agreement, and as I contemplate the past 75 years of our existence, it is evident that Fulbright

Korea has contributed greatly to the friendly understanding shared between the United States and Korea. The rich tapestry of friendship between our two countries is comprised of thousands of individual threads of connection made by Fulbright participants who have crossed the ocean to deepen their understanding and broaden their worldview. I am confident that the efforts of this year’s Fulbright participants, and Infusion contributors, will continue to advance these connections.

I sincerely thank the contributors, the publication team, and the entire Fulbright community who have added their voices not only to this edition, but to Fulbright Korea. I hope you enjoy reading the 18th Volume of Infusion as much as I did.

Kind Regards, Bret Kim Executive Director Korean-American Educational Commission

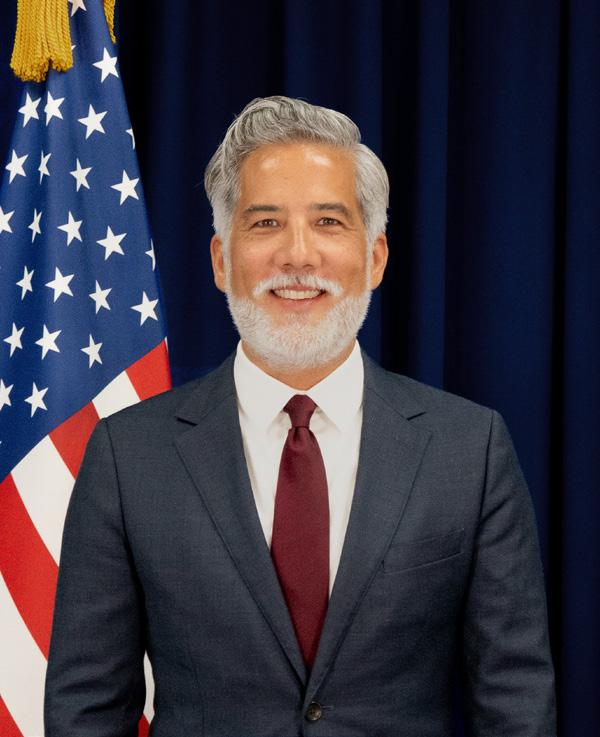

Letter from the Embassy

As we mark the 75th anniversary of the Fulbright Commission in Korea, we celebrate one of the most enduring and impactful pillars of the U.S.–Republic of Korea partnership. For three-quarters of a century, Fulbright exchanges have connected generations of scholars, artists, scientists, and leaders who have strengthened the ties between our two nations through mutual understanding and shared purpose. The Commission’s work, and the achievements of its alumni, continue to enrich both societies and exemplify the power of education and exchange to advance peace and prosperity.

My own journey is a testament to the transformative power of exchange. As a participant in student exchange programs early in my life, I witnessed firsthand how cultural and academic engagement build empathy, curiosity, and a sense of shared responsibility. Those experiences inspired my career in diplomacy, where I have seen time and again how people-to-people connections lay the foundation for strong alliances and resilient democracies.

This anniversary comes at a moment of exceptional significance for Korea on the global stage. Over the past year, our two presidents have met twice, reaffirming the depth of the U.S.–ROK alliance and our shared commitment to freedom and prosperity. Korea’s successful hosting of the APEC Summit further underscored its role as a global leader in technology, trade, and innovation. These milestones remind us that Fulbright’s mission to promote mutual understanding through knowledge and dialogue has never been more relevant.

As we look ahead to the celebration of the United States’ 250th anniversary, I know the Fulbright community in Korea stands ready

to contribute to our shared vision for the next chapter of trans-Pacific partnership. My vision for Fulbright Korea is to deepen alignment with our common values, especially freedom of speech and open inquiry, while supporting the priorities that define our collective future: expanding economic prosperity through the Korea Strategic Trade and Investment Partnership and advancing national security interests in critical industries such as semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, minerals, and artificial intelligence and quantum computing. For seventy-five years, Fulbright has proven that when we invest in people and ideas, we invest in peace. I look forward to working with the Fulbright community to ensure the next seventy-five years carry forward that proud legacy — linking knowledge with purpose and partnership with progress.

Nicholas Namba Minister- Counselor for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs

Embassy of the United States of America Chair, Korean-American Educational Commission

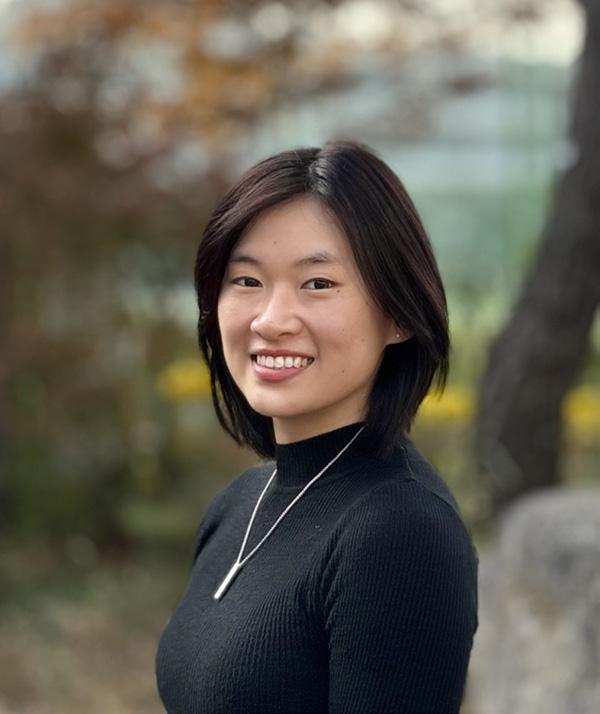

Letter from the Editor

Welcome to the 18th volume of Infusion , the Fulbright Korea literary magazine. Each year, Infusion seeks to continue the conversation of cross - cultural understanding through the artistic and literary expressions of the Fulbright Korea community. Through our publication, we aspire to share the voices of current and former grantees to give a first-hand look at what it truly means to be a Fulbrighter.

With this release, we also celebrate the 75th anniversary of Fulbright Korea. Through its multitude of supported programs, Fulbright Korea has provided opportunities for thousands to participate in new experiences, expand their knowledge and make meaningful connections. Each participant brings new perspectives that bridge trust and understanding between South Korea and the United States.

It is important to recognize the strong memories and bonds that are forged through these programs. Whether through shared laughter over meals, the quiet rhythm of a morning commute or the challenge of communicating across languages, each grantee has their own set of stories to tell that continue to shape their identity and understanding of the world. It is through these experiences that we can further explore cross-cultural communication and forge mutual understanding.

This year, the theme of connection shines brightly throughout our contributors’ works: connection to others, to language, to place and to the ever- changing selves we become. This volume aims to remind us that connection is rarely simple or static. Instead, connection stretches, transforms and deepens with each experience, leaving traces that endure long after

the moment has passed. Connection is what keeps us grounded and moving forward.

This volume is filled with emotionally charged pieces that explore what it means to connect, disconnect and reconnect across borders and moments in time. Starting with Kavya Kumaran’s “When Silence Speaks,” readers come face-to-face with the struggles of communicating with a language barrier. Kumaran depicts the beauty and challenges of intimacy and understanding through language. Furthering the conversation, Henley Verhagen discovers beauty and resolve through their language learning journey in “Dandelion.”

Other pieces find connection in unexpected places. Laura Evans’s “Glimpses of Summer” reflects on how even the heat of a Korean summer can draw people closer together, while Marissa Harrold’s “Introducing, Changwon” provides recommendations in a city that became her second home. The conversation shifts as Rose Nelson turns our attention to a connection that is lost in “The Forgetting,” highlighting the complex emotions that tie one to their placement. Solveig Asplund’s “Oranges/Snow” balances change with acceptance, showing how old connections evolve as new ones form.

Our attention is then shifted to look at Korea through a new lens. Michelle Wei’s “From Seoul to Jeju: Meals Worthy of the Journey” celebrates how food bridges distance and love, and Eden Perez Bonilla’s interview with fellow Fulbright artist Sammy Seung-min Lee reflects on identity, displacement and the search for belonging.

Gabriella Son’s “In Korea, I Try Talking to My Ancestors; I Only Hear Physics” transports the reader to the past. With stylistic inspiration

from E.E. Cummings and Jennifer S. Cheng, she paints a vivid picture of the roles our ancestors play. The author pays homage to the Korean language through the omission of footnote translations and using Hangeul to visually represent the shape of one's mouth speaking.

Finally, Jena Mehl’s “Continuum” closes the magazine by reminding us that even as life moves forward and our ties with the past change, new connections continue to be formed and grow with us.

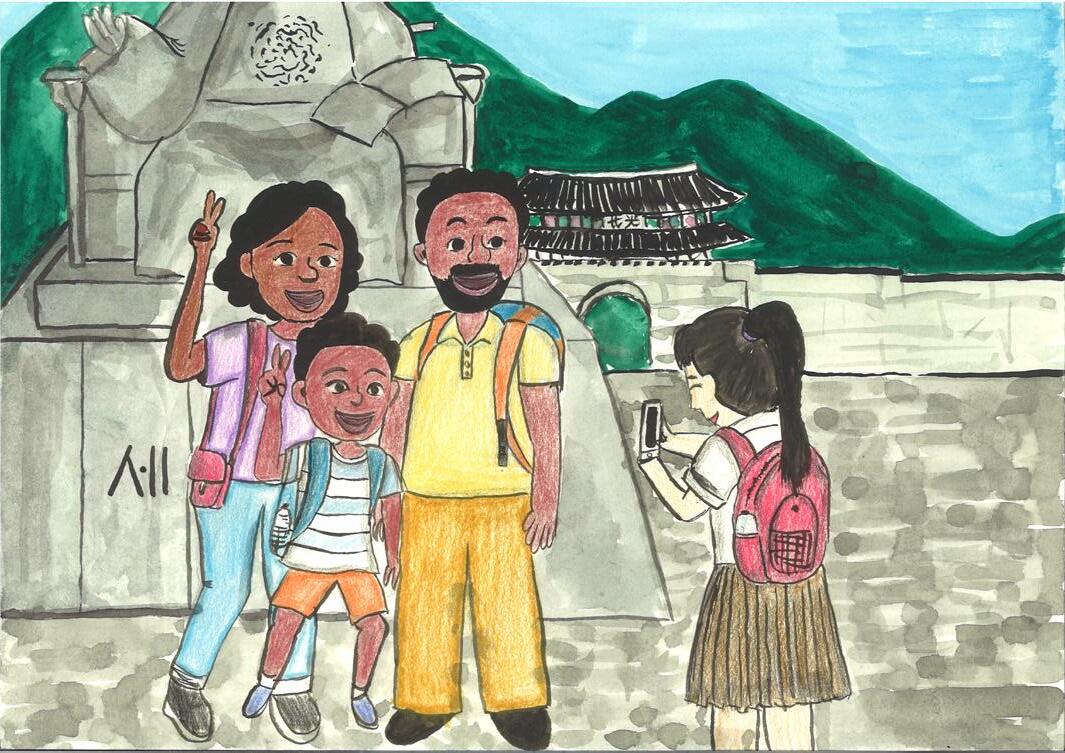

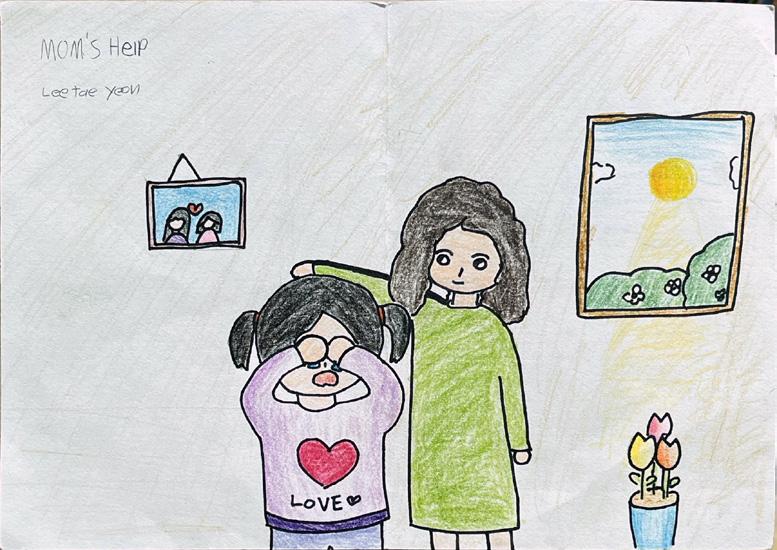

Closing out this volume are the winners of this year’s student competition. These talented young contributors centered their work around the theme of “memories of kindness.” Through poetry and artwork, the students discuss the kindness found in small gestures, words or moments when someone opened their heart and showed that they cared. The students remind us that kindness breeds strong, lasting connections that extend past barriers.

There are no words to express how incredibly grateful I am to have served as Editor-in- Chief not only for this volume but the past two volumes of Infusion as well. The numerous writers, photographers and staff members over these three years have made a lasting impact continuing the open discussion of cross-cultural understanding. I would also like to extend special thanks to Kate Refolo, our design editor of three years; Grace Turley, who has served in various staff positions for three years; and Heidi Little, our publishing coordinator who provided endless support. We are also forever grateful to the U.S. Embassy and the Korean-American Educational Commission for their continued support of our magazine.

I would also like to note that special to this edition, the pages are decorated with drawings designed by our management team to recreate the feeling of reading through someone’s personal journal. We hope that as you turn these pages, you are transported to not only Korea, but also to your own recorded moments of connection and reflection. Whether those moments arise from a time abroad or from your personal journey thus far, they remind us that while each Fulbright experience is unique, the emotions that define them are universal.

In a world that moves quickly, there is meaning in pausing to remember the ties that bind us — to people, to places and to the parts of ourselves we carry forward. Thank you for joining us on this journey. Through these pages, may you rediscover connection in all its forms.

Francesca Duong Editor-in- Chief

3rd Year ETA , Seoul, Seoul

Celebrating 75 Years of Fulbright Korea

A bustle of preparation hung over the lawn as event organizers, waiters and caterers hurried to and fro under the white-awned tents wrapped with colorful strings of Korean and American flags. April showers had come a few days prior, threatening to leave the lawn damp and muddy. Fortunately, that few days gap and warm spring wind, had been enough to dry out the ground, leaving the grass fresh and soft under foot. It was perfect for the reception guests who would soon arrive to stand chatting with drinks in hand.

Around 200 guests were expected to celebrate the 75th anniversary of Fulbright Korea, and as they began to trickle in for the evening’s festivities, the bustle on the lawn grew louder and more genial. Current Fulbright participants greeted each other, comparing notes on experiences from recent months of new life in a new country. Past participants reveled in finding old friends, some perhaps seen recently, others not for years. Everywhere was the warmth of connection as members of one community, the Fulbright community, gathered in appreciation of common experiences and values, expressed through unique lives.

As guests turned their attention to the terrace of the Habib House overlooking the lawn, a member of the Eighth U.S. Army Band began to sing the U.S. and Korean national anthems. His voice, rising from beneath low wooden eaves, served as an introduction. One by one, representatives from the two countries spoke about what Fulbright meant to them: relationships formed, opportunities created, challenges overcome and the world and the lives of those impacted made better.

It is very difficult to summarize the impact of 75 years in a single speech, so while each spoke eloquently, much remained unsaid. How do you capture the daily lives and stories of thousands of individuals over decades? How do you preserve words, images and memories for another cohort, another generation to appreciate and build upon? How do you ensure that relationships carefully made are not lost due to time and distance?

After the speeches were over, as everyone continued their conversations, a series of photos of Fulbright participants and events played in the background: the creation of the Fulbright Korea Commission, early cohorts of Korean and American grantees in suits and dresses getting ready to board their transpacific flights, Senator Fulbright and his wife Harriet Mayor Fulbright receiving a hahm1 from Fulbright Korea in celebration of their marriage. More pictures flashed of Fulbrighters sharing meals, visiting cultural sites, participating in Taekwondo, singing, making Kimchi, graduating, teaching and presenting. Time and space ticked by with images of the 40th, 50th and 60th Fulbright anniversary celebrations.

When it was confirmed that Fulbright Korea would be celebrating its 75th anniversary (its 70th anniversary was during the 2020 pandemic), it commissioned two items: an update to its history book, first published for its 60th anniversary, and the creation of commemorative art to be used

1 함, a box of gifts which a groom’s family traditionally presents to a bride before marriage.

throughout 20252 . Both creative works were to reflect not only Fulbright Korea’s past, but its present and future.

The artwork does this through removing barriers between time and space, symbolically showing how Fulbright Korea continuously brings people and nations closer together. It depicts Fulbright Korea’s constancy of purpose in fostering educational and cultural exchange through the presence of a seonbi 3 carrying a copy of The Great Gatsby along a street in Brooklyn, New York. Simultaneously, it depicts the development of cultural appreciation and integration through the blending of traditional and modernized hanbok worn by both the seonbi and the Americans standing to his left.

Fulbrighters can likely relate to this artwork on a personal level as their own perceptions of time and space morph. They calculate across time zones with ease in their efforts to stay engaged with friends and family halfway around the world. KakaoTalk and WhatsApp find a home on their phones as messages (and stickers) flow across borders long after other contact information has been lost. For some, the 12 -to -14 -hour flight across the Pacific becomes an annual commute accompanied by luggage stuffed with Trader Joe snacks, K-beauty products and gifts for loved ones.

It is in these “new normal” activities that Fulbright’s strength truly lies. While the 75th

2 To read more about Fulbright Korea’s history, visit www.fulbright.or.kr.

3 선비, a Korean scholar from the Joseon Dynasty.

anniversary presented an opportunity for the Fulbright community to pause and reflect on its accomplishments, its values and its mission, Fulbright at its core is about inviting as many people as possible into greater connection with themselves and the world around them. And that is how peace is built as the neighbors we are to love as ourselves are no longer simply across the street, across the state or across the country; they are across the world.

Looking ahead to the next 75 years, may we continue to enjoy the power of connection, one person, one family, one community at a time.

Heidi Little Infusion Publication Coordinator Assistant Program Manager Korean-American Educational Commission

향해 , Toward a Dream, Bo Kyung Ham

Naju

Echoes of Childhood, Shastia Azulay, Naju, Jeollanam-do

When Silence Speaks

By Kavya Kumaran

I’m still haunted by the ending scene in Han Kang’s "Greek Lessons."

In the final moments of the novel, the two main characters — a male professor of Ancient Greek slowly going blind, and a female former teacher who has gone inexplicably mute — find a way to communicate. Lying next to each other in the dark of the professor’s bedroom, they converse back and forth in Hangul on each others' palms.

I often feel like the mute woman from the novel.

Despite no physical disability, my attempts to speak Korean suddenly find unborn words caught in my throat, my tongue leaden with silence. Like her, my silence is a womb that gives birth to simultaneous isolation and comfort. Until I came to Korea, I never understood so viscerally what a language barrier meant.

"Greek Lessons" explores language as both a bridge and a barrier. At the end of the novel, the characters remain in silence yet transcend the language barrier — a moment of triumphant but bittersweet joy. It is made all the more melancholy when juxtaposed with the professor’s first love: a deaf woman earlier in the novel. Their star-crossed love ultimately ends because he fears that his progressing blindness and her deafness will leave them with no way to communicate. He suggests that his first love start speaking aloud to accommodate his condition. In a rage, she ends their relationship.

The implicit message is this: if he loved her enough, he would find a way to communicate without asking her to learn his language. If he loved her enough, language would not be a barrier. If he loved her enough, even silence would be

sufficient. The result of him overcoming the language barrier with the mute former teacher at the end becomes a testimony to finding emotional intimacy beyond the limits of speech.

Which raises the question: does intimacy actually require language?

As a beginner in Korean whose listening comprehension far outpaces my speaking, I often feel like the mute woman in the story: an observer privy to the world around me, unable to fully participate. And yet, a sort of platonic love, connection and intimacy have found their way to me.

The people who feature most heavily in my days here in Korea are Farrah, the native Chinese teacher; Sun-Hee 쌤1, the math teacher; and Eun- Ok 쌤, the Korean literature teacher. While Farrah is an advanced English speaker, neither Sun-Hee 쌤 nor Eun- Ok 쌤 are proficient English speakers. And yet, I am filled with ease and comfort in their presence.

Our lunch conversations are a mix of my broken Korean, Papago and ChatGPT translations. We might comment on the weather, compliment each other’s outfits or ask what we think of the school lunch (often punctuated by "진짜 맛있어요!”2 on my end) on the walk back to the teachers’ room. Sometimes, these lighter topics are replaced by more personal questions about family or relationships.

In a world that rewards instantaneous information exchange, the willingness to wait for the delay it takes me to type my detailed

1 Ssaem , a familiar form for “Teacher.”

2 Jinjja masisseoyo, “Very delicious.”

thoughts into a translator app invokes deep gratitude. To be inconvenient and still be chosen is an unmatched delight — one I can’t help but relish. Sometimes I wonder how they fill in the parts of me that my silence does not allow access to, the blurry outlines of my personality painted with colors of their own choosing.

It is the little things that touch me most: the way Eun- Ok 쌤 calls the waiter over for a second bowl of soybean paste soup at a 회식3 because she noticed how much I loved the first bowl, her bright smile whenever I say “안녕하세요”4 to her in the morning, the way Sun-Hee 쌤 brings us hard-boiled eggs for breakfast once a month or the way she squeezed my arm at the Hampyeong Butterfly Festival she took me to on our day off. Touch-starved after months away from my family, the warmth of her hand through my flannel gave me a moment of familial comfort. And finally, the way she offered, without question, to drive me to the hospital when I was incredibly sick. Without words, they consistently answer the question that has haunted me all my life: do I matter?

I can’t help but laugh at the strangeness of so keenly feeling their “yes” to my question, especially in light of a recent fizzled-out romantic connection I had with a highly accomplished and intellectual English speaker. We had been set up by mutual connections in a long distance format and would spend hours chatting over video calls. But the inevitable inconvenience of me, time zones away, was eventually a deal breaker. While I understood the logic of his decision, at least enough to depersonalize it, the severance left me feeling discarded.

It made me realize how special it is to choose to develop intimacy with someone who is an “inconvenient” option. It also made me question if fluency had, in fact, impeded the development of intimacy between us in some way. With more words to hide behind, did we get further from saying what we actually meant? Was fluency truly the begrudging bedmate of intimacy, or was it a tease, obfuscating the truth of the matter?

Obviously, fluency has its place. Alone in my apartment, I find myself thinking about the bilingual fights with my parents growing up. They spoke in Tamil and I in English, each of us wielding our language of choice with perfect incisiveness, various meanings lost in translation. I understand my parents better now. What an exhausting endeavor to create a life in a second language — one in which everything you say is like off-white: a shade close to what you mean, but never exact.

3 Hoesik, a Korean work dinner or happy hour.

4 Annyeonghaseyo, “Hello.”

Bridge, Samantha Fabian, Paju, Gyeonggi-do

Yet I found myself in English-language practice with a student one day when she confessed in unvarnished English, “Teacher, all the beautiful girls have boyfriends.” To which I replied, “You’re beautiful.” She said, “No, I’m not.”

The yearning, unsoftened by pretense, evoked a swell of empathy within me. Freed from the expanse of fluency, the constraints of the language barrier wrought a sort of raw, rare and precious honesty.

Like the mute woman, I find intimacy within the silence, connection outside the bounds of language. Instead of tracing Hangul on the palm of a professor, I leave coffee on their desks after lunch, bring gifts from my summer travels and share a fresh cluster of purple grapes that I buy just for us. Without words, I say: “I care about you, too. Thank you for seeing me. Thank you for caring.”

Yudalsan Sunset, Rachel Hudson, Mokpo, Jeollanam-do

“

Dandelion

By Henley Verhagen

민들레.”1 My co-teacher tells me the Korean word for dandelion and asks for its name in English. He points. It’s growing through a crack in the pavement.

Every time I learn a new Korean word, I am transported to a particular vocabulary cram session during orientation. My roommate, head on the floor and feet on the wall, said, “I feel confused, like I can’t remember the person I was in America.” Everything outside our window was dark. Some people coming back from 노래방 2 told us it was snowing, but I wouldn’t know. I had been studying since dinner.

I asked, “Do you think that’s a bad thing?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “I really don’t know.”

In the 20th century, linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf hypothesized that the grammatical structure of our native language influences the way we think. If true, this would mean that thought is based on language and not the other way around. I had a college professor who explained that this theory could extend to second-language acquisition: even if you reach near fluency in a second language, your understanding of that language will always be affected by your native tongue or tongues. This sounded like a challenge. Though I knew true fluency would be impossible, I wanted to push myself as far as I could go. I wondered what linguistic immersion would do to my brain, what cracks would form in my understanding

1 Mindeulle, dandelion.

2 Noraebang, lit. “singing room,” a place to sing along to music with friends.

of the world and what new growth I would find within them.

When I arrived at my placement, I was immediately choked by spring. We have spring in my American hometown, too, but spring in Korea is heavy. It makes my throat itch. It feels like a season of grief. It passes like a soccer ball through the feet of boys who run so fast they don’t realize they’ll live in pictures for the rest of their lives. I think it’s the flowers. We didn’t have this many back home; besides cherry blossoms and dandelions, most are unrecognizable. I hear the birds in the morning and they don’t make me sad, because they don’t sound like home. The flowers don’t look like home either, but they do. They do make me sad. Each homeroom class rushes to take photos beneath the cherry blossoms before they fall. There was only one cherry blossom tree in my American neighborhood. The flowers I remember vividly from home are actually dandelions. The fields were covered in them, the sidewalks were covered in them. They were ugly and stubborn. They would grow anywhere.

민들레 is just one of thousands of words I didn’t know that I didn’t know. The conversation with my roommate happened over my shoulder, with a page of Korean vocabulary splayed in front of me. I was struggling to absorb everything I didn’t recognize from the next textbook chapter. During our first meeting, our Korean Language instructor told us that Americans frequently start their sentences with 솔직히3 and 사실은, 4 but

3 Soljikhi, honestly.

4 Sasil-eun , actually.

native speakers don’t often use these phrases. I vowed to stop using both, just to see if I could.

My roommate’s feet were still on the wall. “I guess I just feel confused. You know?”

“Honestly, I feel,” I responded. The words on the page blurred as I realized there wouldn’t be enough time to memorize them all. “Honestly, I …” I would have to go to class with a vocabulary full of holes.

By the end of five weeks, I discovered far more holes than I had mended. I would have stayed in our frigid classroom forever if I could. During Korean Language graduation, I cried until I couldn’t breathe, and then I cried more. They gave us umbrellas instead of flowers. As I waved goodbye to our teacher, I tried to tell her “I’ll miss you” in Korean. It was a simpler sentence than any on our final exam, but I choked. My throat opened up and the words fell sideways. I felt like I hadn’t spoken a language until that moment. I had said words, but I’d never spoken a language.

Before I could catch my breath, two months had passed. The snow melted and cherry blossoms bloomed and fell faster than spring itself. In our empty classroom, my co -teacher mentioned that I use 솔직히 and 사실은 a lot. I put my head on my arms and laughed. Sapir and Whorf were right. Language is a part of me. It’s inside me. It lies behind my eyes and just beyond the tip of my tongue.

It rained on the way home from school, with a wind that tore my umbrella inside out and

rendered it useless. I couldn’t stop laughing. There are as many empty classrooms as there are students in the world, and I felt thankful to have found mine. The next day, the rain would bring more flowers coated in pollen so heavy it would make me feel sick.

“Dandelion?” my co -teacher asks, once I tell him. “Do you know why you call it that?”

“Why?” is his favorite question when it comes to English, just as it’s become mine in Korean. I love the way it takes a native language in each hand and pulls until there’s no words between them. I feel like my roommate, upside down, as I think back to a time when a dandelion was just a dandelion, and I blindly called them weeds.

“사실은 저도 잘 모르겠어요 ,” I say. “Actually, I really don’t know.”

Pansori and Slow Walking Island, Rachel Hudson, Wando, Jeollanam-do

Suwon

Geoje Island

Gochang

Field Trip, Eden Perez Bonilla, Gochang, Jeollabuk-do

Turquoise Undulations, Laura Evans, Geoje, Gyeongsangnam-do

Paving Stones, Rose Nelson, Suwon, Gyeonggi-do

Busan

Rainbow Connection, Laura Evans, Busan, Busan

Yonggungsa Temple, Rose Nelson, Busan, Busan

Gwangalli Beach, Eden Perez Bonilla, Busan, Busan

Glimpses of Summer

By Laura Evans

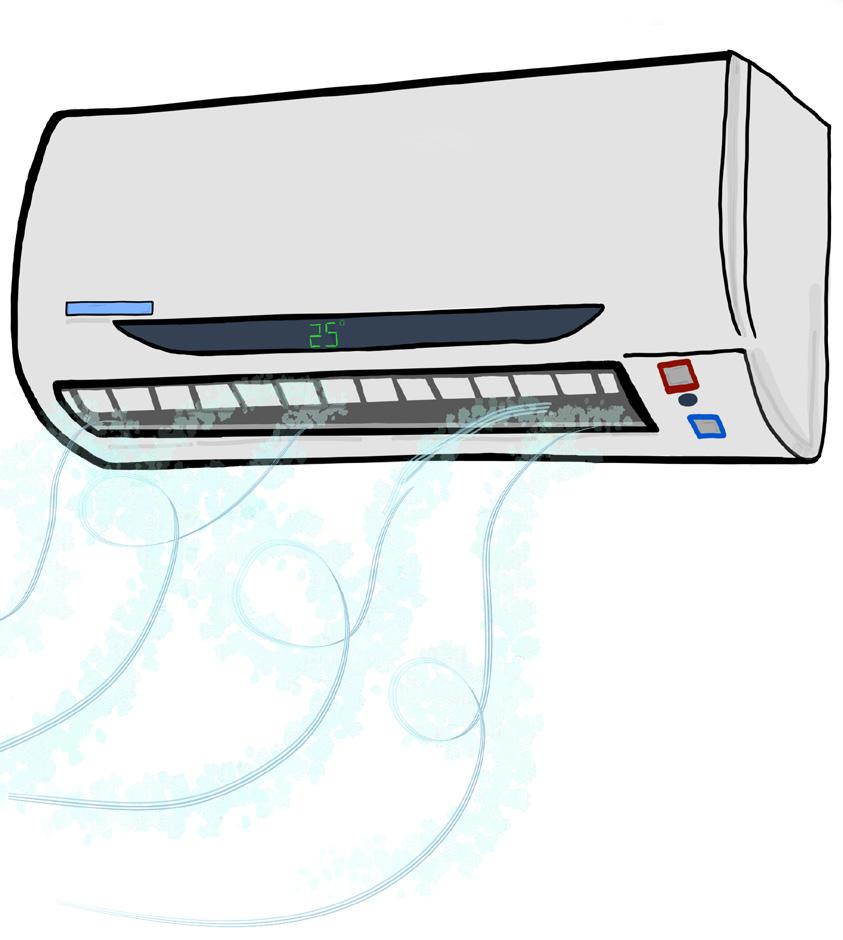

In the sweltering heat I text my friends, “I need a T-shirt that says, ‘I survived Korean summer.’” Though, to everyone here in South Korea, this is simply summer. There is nothing special about this heat. I nod in agreement with the teachers’ typical morning small talk, “It’s so hot today!” or “The humidity is really bad.” It is neither hotter nor more humid than the day before. In the same way, when I lived in Minnesota, people would typically comment, “Sure is cold out there!” and “It wouldn’t be so bad if it wasn’t for the wind.” In the winter, we always had to wipe water off the windowsills that formed because of the temperature contrast between the cozy indoors and the frigid outdoors. In Korea it is the opposite: in summer, the classrooms become aquariums as cold drops drip down the windows. The school hallways are open air, so the windows on the hallway side fog up too, completing the underwater illusion.

Every day after lunch, an administrative worker cracks a window in the main teacher’s office. One day, she announces cheerily, “Refreshing time!” implying she means to ventilate the indoors with “fresh” outdoor air: 35 degrees Celsius and 85% humidity. I protest, “Refreshing time? It doesn’t feel very refreshing out there!” She counters with a reassuring, “Well, it’s good for your health.”

On my commute home, there are two bus stops that drop me roughly equidistant from my apartment. Some days I stay on the bus until the second stop just to add another minute under the cooling air vents. Either way, I must then embrace the inescapable 10 -minute walk that will get me home. I brighten in the moments of instant relief, when I catch a pocket of cooled air leaking out from a business front as I pass by. Whether I spend two minutes or 10 minutes walking outside, by the time I climb the three flights of stairs to my apartment door, I am covered in sweat.

At home, a standing AC unit awaits me in the living room along with my host brother. It’s baseball season, and my host brother practices swinging his bat indoors. I’m shocked my host parents allow this, but, after all, it is too hot to go outside. After dinner, he begs his mom to turn on the TV since his favorite team, the Lotte Giants, is playing. He shouts an invitation to me while his eyes remain glued to the TV. Though not a huge fan myself, I plop down on the floor in front of the fan and watch while I cool down. The living room AC unit makes it the coolest spot in the house, so the family often gathers in the area reading books, folding laundry or playing board games before bedtime. I’m also lured out of my room by the prospect of a cooler environment.

Watching my host brother hoot, “그렇지!”1 at the top of his lungs — jumping on the couch with his arms overhead in celebration — is an added bonus of hanging out in the common space. He comes over to tell me about the points and the innings. I don’t understand everything, but I enjoy being included.

Though I’m a chronic night owl and a bit of an insomniac, the family’s earlier bedtime encourages me toward better nighttime habits. I turn out the lights, but my eyes remain open in the sticky darkness. I think of how humans survived in all climates for thousands of years prior to the invention of indoor temperature control. A comforting thought.

Since I can’t sleep, I decide to catch up on messages from the day. KakaoTalk (Korea’s primary messaging platform) has special GIF stickers you can send. Usually they are exaggerated cute characters conveying the highs and lows of human emotions. Similarly, they can be used to reflect the highs and lows of summer heat. My friend sends me a GIF sticker of a character tossing and turning on a pillow as the pillowcase rapidly soaks through with sweat. Nasty mental image. Really cute sticker, though. Perfect for June, July, August, or even September! I can’t wait for the crispness of autumn’s edge in the air, but the only crispness available at present is my sunburnt skin. Although my ever-oscillating fan works hard to save me from melting into my bedsheets, I crave the tucked-in feeling of my fluffy blanket against the chill of winter. Some nights, I embrace the heat. It’s easier to do this after I’ve gone to my workout class. Once I establish a baseline layer of sweat, I don’t seem

1 Geureochi, “Let’s go!”

to mind it anymore. The cover of nightfall helps staying outside become bearable. On my walk home, I take a detour and climb to the roof of a nine-story apartment to dance between the stars and the city lights. My ligaments feel softened to a near-liquid state — a gift of limberness on account of the heat, as if my body reaches a boiling point and is free to be released from solid form. In winter, I would be weighed down by a thick coat and stiff joints. I feel so light in this state. Wind stirs against the sweat clinging to my arms, cooling me and clearing my head. As I leave the rooftop, I remember the other day when I looked out the window on my bus ride home, and in the blur passing by I saw a couple slow dancing in the park despite the blistering temperature outside. A man in a suit. A woman in a dress. They were slightly stooped with age. One hand on her lower back, the other hand intertwined with hers. One. Two. Three heartbeats and the bus turned a corner. Was I the sole witness to that moment of sweetness?

Place, Henley Verhagen, Pohang, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Even the afternoon sun couldn’t keep this couple from their date in the park.

Sometimes the heat allows us to engage with each other in new ways. For example, finding camaraderie in fighting to keep the classrooms below 30 degrees Celsius, or an opportunity to ask questions deeper than, “What’s ‘humidity’ in Korean?” Heat can give us a time to learn more about what co-workers plan to do during the upcoming summer vacation.

Other times, like the couple in the park, we persist in our same patterns despite the heat. I still drink hot coffee in the morning. The administrator still cracks a window after lunch. I still take my commute on the bus, go to the gym after dinner and dance. Even as I’m drained by the heat, there is so much aliveness in it.

Despite its brutality, the summer heat serves to connect us in a way no other season offers. As I sit on the living room floor in front of the fan with the people I love, an unbelievable appreciation swells in my chest.

I am grateful for the heat.

Sunset to Remember, Karen Garcia, Jocheon, Jeju-do

Jeju Island

Healing, Henley Verhagen, Seogwipo, Jeju-do

Introducing, Changwon

By Marissa Harrold

On the evening of the Fulbright placement ceremony, I wasn’t at all familiar with the city of Changwon. One of my study-abroad friends had repeatedly told me that Changwon was her hometown, yet by the time the placement ceremony arrived 18 months later, Changwon was brand new to me. Immediately upon returning from the ceremony, I stayed up late searching Google, Naver and YouTube (both in English and my fractured Korean), devouring any tidbit of information I could find about my next home. For two weeks, Google Maps’ street view was my best friend. I watched random walkthrough videos, read the city government’s website and scrolled through Reddit for hours. However, I never felt like it was enough. I needed to know more about Changwon.

This is what inspired me to write about Changwon, after prompting from my friends. I want this piece to be what I wish I had when I was searching for anything I could find about the city. And yet, no amount of research could have prepared me for the reality of moving here. In Changwon, I’ve developed relationships with people who will be a part of my life long after my time here ends. My host family, fellow Changwon Fulbrighters, co -teachers and students are truly who have made this place so special to me.

Weekly meetups with nearby Fulbrighters and spontaneously running into students in the street make every day in Changwon brighter. I’ve come to love exploring the city both alone and with company. The city has a heart and soul that is often unknown to others living in Korea. So full of things to explore, what makes Changwon, the capital city of Gyeongsangnam-do province, so special?

Distance Mokpo, Samantha Fabian, Mokpo, Jeollanam-do

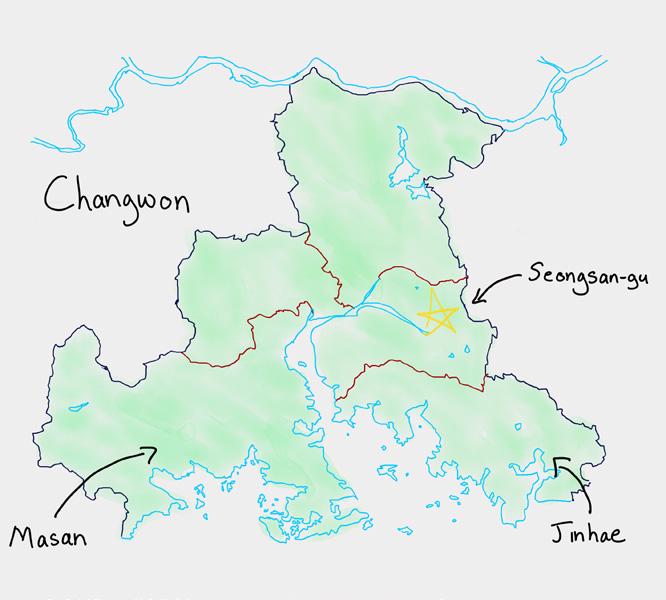

In 2010, the three neighboring cities of Changwon, Jinhae and Masan merged to form the major city that is today known as “Changwon.” It’s worth noting that locals still refer to Masan and Jinhae by their individual names despite now having merged with Greater Changwon. The entire city is made up of five "gu," or districts. I live and spend most of my time in central Seongsan-gu. If you’ve ever had a conversation with me, you’ve likely heard me refer to it as “Changwon proper.”

The city’s downtown revolves around a huge rotary. This is where you can find various shopping malls, outlets and supermarkets. A short walk north of the rotary is Yongji Lake Park, where families take their afternoon strolls and young couples lie in the grass picnicking or reading. This man-made reservoir has served as the perfect place for several friend meetups, especially after grabbing a drink at one of the cafes that overlook the park. The park is also within walking distance of Changwon’s Garosu-gil, or cafe street, which is another favorite among my local friends and out- of-town visitors. The street lined with fairy lights is home to delicious bakeries and restaurants of different cuisines, where you can find anything from pasta and Mexican food to Dubai-style chocolate croissants.

On the south side of the rotary, in the bustling Sangnam commercial neighborhood, you’ll find a completely different vibe. The streets are crawling with students during the day; come night, the crowd becomes more mature. Numerous streets are crowded with restaurants, cafes, arcades, pochas1 and bars, photo booths and more. Needless to say, this is where nightlife thrives in Changwon. My personal haunt is the two -story Artbox that occasionally has Sonny Angels in stock and never disappoints with its sticker supply. I’ll never forget the time that I randomly bumped into my host brother at an Olive Young in the neighborhood, proving the youthful Sangnam is not a safe place for teachers on their days off.

1 포차, A Korean-style street stall typically serving affordable food and drinks.

Swan Lake, Shastia Azulay, Japan

Although I admittedly haven’t spent much time in Jinhae (which comprises the southeastern-most part of the city), the district is undoubtedly most famous for its annual Cherry Blossom Festival in the spring. The week-long festival welcomes thousands of visitors from all over the world. The Yeojwacheon Stream and Gyeonghwa Station are famous photo spots. Here, tourists can wait in line while enjoying street food from countless vendors. Though I missed peak bloom this year, I look back on the festival fondly, as it was a formative bonding moment with some of my now-closest friends.

Changwon is also a great place for sports fanatics, evidenced by me and my friends becoming frequenters of live sporting events. Changwon has two major league teams, basketball and baseball, and is the home of the K League 2 Gyeongnam FC soccer team. I’ve become a major fan of the LG Sakers, as our basketball team won the 2025 KBL Championship. If you’re a baseball fan like I am, it’s worth venturing out to Masan to watch the NC Dinos play at the Changwon NC Park. Just be prepared to cheer for the whole game.

Even if you’re not a sports fan, Changwon has lots to offer. I get my nature fix by wandering around my nearby Rose Park or along the streams common in Changwon neighborhoods, admiring the silhouettes of the surrounding mountains. If you want to escape the residential areas, there are numerous hiking trails. Pallyongsan in Masan has impressive stone towers, and the Jeongbyeongsan path is near Changwon National University. Additionally, deep in the south of Masan is Gwangam Beach. Despite being the only swimming beach in Changwon, it offers a relaxing contrast to the city’s industrial backdrop.

For those drawn to culture, Changwon has more understated offerings compared to the neighboring cities of Jinju and Gimhae. Notably, Changwon-ui Jib, or Changwon’s House, is a historic tourist attraction. The head of the Sunhueng An Clan resided in the house over 200 years ago. There are also the Gyeongnam Art Museum, displaying local art from around the province, and the Moonshin Art Museum, which showcases the work of the late artist Moon Shin. Also in Masan is the Changdon Art Village, a vibrant art district that my host Korean Democracy: A Fight for the Future, Alyssa Taylor, Gwangju, Jeollanam-do

Forever Kia Tigers, Alyssa Taylor, Gwangju, Jeollanam-do

brother said used to be an old village. The colorful murals that line streets and new-age sculpture arches that loom over walkways were created to revitalize downtown Masan, the local heart of art and culture in the 1960s and ‘70s.

My fellow fans of K-culture will be excited for the Changwon K-pop World Festival in the fall. This event gathers K-pop coverists from around the globe to compete on the main stage. K-drama viewers will likely enjoy visiting the Maritime Filming Location, which serves as a backdrop for historical dramas such as “The Rebel” and “Kim Su-ro.” Visitors can walk through the set and see what life might have looked like during the Three Kingdoms period.

Traveling to these different bucket-list items may seem intimidating, and that’s understandable. Changwon is huge. Luckily, the urban setting provides accessible and consistent city bus routes. Inter-city travel is also quite easy with Changwon as your home base, having several bus terminals and three KTX train stations. However, when booking tickets out of a Masan bus terminal, pay extra attention to which one you leave from — a lesson I learned the hard way.

For those looking to explore lesser-visited cities in Korea, may this inspire you to consider a trip to the one-and- only capital of Gyeongsangnam-do: Changwon! To anyone who visits in the future, I am jealous of you — I hope you love this city as much as I do.

Summer Views, Karen Garcia, Malaysia 25

Monet's Lotus, Shastia Azulay, Naju, Jeollanam-do

The Forgetting

By Rose Nelson

The hardest part is the forgetting. We carry the burden of our memories, the tears we spilled toiling away for a year, and the love that took root like a weed.

Watching others fill the shoes that we broke in, breaks me. They don’t know how many laps we had to run before the soles softened, and that pinch in the toes became bearable. They slip them on, pulling the laces tight, wiggling around inside this hand-me-down pair.

I fear they won’t come to know it like us — The grooves worn down by our feet, our tracks Our mark left on this ground, our home. But, perhaps, maybe I’m afraid they will know it like us.

They’ll walk the same path we did, see the security guard at the bus stop and he’ll shout hello, exclaim that they look a little different, something’s changed — their hair or their height or they got a little tan — After all, he can’t see that well across the road — And he’ll imagine that he’s been friendly with them for years.

At school, no one will mention their predecessors — yes, that’s the word they use for us — they like to keep things professional — And they can imagine that they’re just as new to these people as this place is to them, as it once was to us.

We will watch from afar as they lay down roots earnestly and shore up the walls of what used to be our city, And we will watch in the end when they too are plucked out and our reapers look at the earth and say — “What good fertilizer! Let’s plant the next ones here, too.”

The hardest part is the forgetting.

Trip to Japan

Train to Kyoto, Rose Nelson, Japan

Safety Checks, Shastia Azulay, Japan

Nightlife, Shastia Azulay, Japan

Oranges/Snow

By Solveig Asplund

I.

At the beginning of my first semester of college, I was recommended a song by Lake Street Dive called “How Good It Feels.” I had seen my friend sing their songs during her a capella performances and found myself humming them regularly.

When the song begins, the singer wants to tell us how good it feels to be alone. She relishes the fact that there’s finally no one who mandates conversation or takes up her time. She doesn’t have anyone — and she doesn’t need them either. The song arrived at a time when I was deeply devoted to independence, and I often wanted to do things by myself, perhaps to prove that I could. As spring’s flowers began to bloom, I liked meandering through campus with my headphones on.

What makes this song so magical comes in the second half, when the singer turns on herself. She changes her mind:

"How good it feels to have nobody / To keep up relations with" turns into

"How good it feels to have somebody / To keep up relations with"

This is one of my favorite lyrical patterns: over the course of just three minutes, we see someone grow. By the time the song reaches its peak, the singer is now asking us to consider the joys of spending time with someone. Something has happened behind the lyrics, though we don’t know what — all we know is that she’s become happily intertwined with other people. The background vocals fill in, and the song ends simply:

"How good it feels to have a friend, be together again / How good it feels"

II.

Almost all of my students are curious about “the American,” so they pay attention even when they don’t seem to understand what I’m saying. They’re largely well behaved and sweet, and are at the funny age where some have started to grow up and some haven’t, so when they line up their profiles, they look like an uneven city skyline. The boys wear sweat sets and avoid sitting next to the girls at all costs. I was explaining to my friend how 75% of the class wear the same circular, thin -rimmed glasses. “Right,” we realized, laughing over the phone, “they don’t know how to put in contacts yet.”

I was calling this friend to catch up, but also because being in Korea has made me think about the relationships I form outside of my expected orbit. I found myself trying to explain how I feel about teaching. I began with a story.

In my first year of college, a girl told me that she admired the longevity of my relationships. She had only recently met me, but it was something she observed from the way I talked about my family and friends. It was one of those compliments that someone wouldn’t recognize in themself, like having kind eyes. Yet when she pointed it out to me, it suddenly became a point of pride. I thought about how, when I know someone, I like to imagine I’ll know them forever.

“Anyways, my point being: teaching is odd, because it’s these short relationships,” I said. “But they still feel really important, if that makes sense.” I paused before continuing. “The weirdest part, I think, is that I won’t know these kids in ten years. Maybe even in two.”

“Right, you’ll be like some dream they had. Like, 'Remember when we had that American teacher? What was her name?'”

“Exactly! But they’ll still be important to me in some way, you know? Like, 'the first kids I ever taught,' even if I don’t remember their names.” I thought about it some more. “And maybe, by then they’ll be 22 and they’ll realize I had no clue what I was doing… and I’ll be 32 and thinking the same thing,” I laughed. “What a totally weird dream it’ll be.”

Manse!, Colleen Rhein, Mokpo, Jeollanam-do

III.

My office is on the fifth floor and I share the space with three other women: my co-teacher, the substitute teacher, and the science teacher. I’m not sure how to describe our dynamic. We get to school by 8:40 a.m. and leave together promptly at 4:40 p.m. We’re partially friends, partially co -workers, partially “cultural ambassadors” of our two countries. They explain to me the world I’ve been transported into; whereas, I struggle to teach the small difference between “of course” and “you’re welcome.”

Sometimes we work in silence, though laughter is a common sound in the office. This is in part because I’m often clueless, and in part because we’re all just prone to laughter. When something is especially funny, and we’re all laughing those big silent laughs, one of the women in the office will take a gulp of air, sigh, and declare, “Now, we will live so long.” Laughter is good for your health, apparently.

At school, it’s not uncommon for me to get asked if I’m tired or sick. It makes me wonder about the bags under my eyes, or the pallor of my skin. Is it sallow? Yet as a friend from childhood pointed out to me on a call the other day, “Isn’t it nice that your co -workers care about how you’re doing?” It is.

[An example] When I was stressed a few days ago but not expecting anyone to notice, my co-teacher did. She left her work and drank green mandarin tea with me. My other officemate gave me an egg, and I cracked it on my desk to eat. We all spun lazily on our rolling chairs and talked about Korean actors we thought were handsome.

[Or another] Yesterday, I mentioned to another co-teacher that my throat hurt slightly from the bad air quality. When I returned to my desk after lunch, a small bag of cough drops was waiting on my keyboard. A present of lemon and honey, unexpected. I messaged her a thank you, which didn’t seem like quite enough.

[One more] A few hours later, as I was walking out of the office, a teacher hurried to shove three ripe oranges into my bag before I left. I ate two of them that night, and woke up the next day to the smell of citrus still lingering in the air.

Cherry Blossoms, Samantha Fabian, Mokpo, Jeollanam-do

IV.

Last Tuesday, it snowed. This snow was a special occasion not only because it’s March, or because snow is rare in Masan, but because it was snow. Snow is always special, I think. My co -teacher who was clicking through the slides saw the snow first. After the initial announcement, the students quickly ran up to the windows. They opened them and crammed shoulder to shoulder, jostling for the best spaces and exclaiming over and over again, “눈! 눈이 와요! 눈이 와요!”1

They stretched their hands out through the safety bars like crazed fans at a concert barrier hoping to be touched, if only momentarily, by their idols. Some tried to eat it, but the second they brought their hands inside, the snow melted on their fingertips. Still, they tried again. I watched the snow, too, but mainly I watched them.

Within a few minutes, the snow disappeared as quickly as it came. The sun shone onto the wet street outside. Class resumed. I could tell everyone’s mind was somewhere else — mine included. So I talked instead about a snow day I’d had in middle school, when I’d gone over to a friend’s house and we’d put on an armor of their parents’ coats, gone outside and flung ourselves into piles of snow on the New York City streets. There were three of us: one of whom I’ve lost touch with since, my best friend and me. I recalled looking down a short flight of stairs and realizing that, thanks to the snow, I could jump down it without being hurt. Miming the actions for my students, I jumped and held my arm up to signal how high the snow had felt to me at the time. The students laughed. Maybe at the impossible height of the storm I talked about, or maybe, I think, at the admission that I was once their age, too.

When the bell rang, I stood by the whiteboard and watched the students hurry to leave. Some of them stopped to briefly bow or to say a loud “Goodbye, teacher!”, but most of them ran straight past me, pulling their jackets on as they flew by. I watched them flood into the hallway, meeting their friends on the go and streaming towards the stairwell in laughing flocks. I smiled in the doorway. I wondered where they were headed, and if they knew either.

1 Nun! Nun-i wayo! Nun-i wayo!, “Snow! Snow is coming! Snow is coming!”

Last Azaleas of the Season, Karen Garcia, Hallasan, Jeju-do

V.

At the beginning of each new phase, I keep mistakenly thinking my social life is somehow set. This thought has never depressed me, but still, I’m continuously disproven. I wonder when I’ll learn to expect friends, or when it’ll sink in that each year, spring follows winter.

I thought about this to some degree when I left high school and when I finished studying abroad with new friends. When I graduated college, it was nearly all I could think about. I talked about this question too with the friends I made in Goesan back in January this year. And it arose again, in some small, quiet way this morning, as I stood in the fluorescent light of the convenience store on my corner and decided to buy my co -teacher a chocolate milk. She doesn’t drink coffee.

Sometimes I have dinner with my co-teacher and her husband. Both of them are elementary school teachers and grew up in this area. A week ago, they brought me to a restaurant I’d been scared to try alone. As I cleaned my hands, I told them I was born in 2002, and they looked at each other with shock. She laughed, and leaned over as if to tell me a secret: “The first students we taught — they were born in 2002.” I asked if they kept in touch with these elementary kids who were now my age. “Not really,” she said, unbothered. “But one student sent me a bell from Chicago a few years ago, because he knew I collected them.” She added, “He’s in the army now.”

When the food arrived, they told me which sauce to dip in and which sauce to eat with what food. The conversation shifted. I smiled at each new bite of “낙지”1 — delicious — and they smiled at my smile. We became like those boxes of mirrors you stand inside where, when you move, you see that movement echo on forever.

The next day on my walk to school, I saw that the cherry blossoms were beginning to bloom.

2 Nakji, squid.

Old Spring Parade, Rachel Hudson, Mokpo, Jeollanam-do

Jeonju

Duck, Eden Perez Bonilla, Jeonju, Jeollabuk-do

Purple, Eden Perez Bonilla, Jeonju, Jeollabuk-do

From Seoul to Jeju: Meals Worthy of a Journey

By Michelle Wei

Like the many gourmets before me, I live to eat. I do not eat to live. For me, happiness means seeking out new experiences, wandering across borders, engaging with loved ones and having the freedom to inhale, devour and savor good food. Food is a basic human need for survival, but good food provides an additional virtue of bringing true, spiritual happiness. A life devoid of good food is not a life worth living. When I arrived in South Korea, I was determined to find restaurants that spark joy. Having grown up with access to diverse cuisines and being fortunate enough to have tried foods around the world while traveling, I’d claim my palate is refined enough to give Anton Ego a run for his money. My hunger dictates my budget, leading me to visit everything from mom- and-pop shops and street food stalls to fine dining establishments throughout the country. Mukbangs, food-related broadcasting programs, and social media pages highlight local specialties and deem which restaurants are a “must-go;” this has led me to test these restaurants for myself and decide if these places actually deserve the accolades posted online. After going through my personal list of top restaurants I’d visit again and again, I’ve chosen these places not for their uniqueness as menu items, but for their unforgettable flavor, quality and overall ability to surprise and delight.

Waiting, Henley Verhagen, Tongyeong, Gyeongsangnam-do

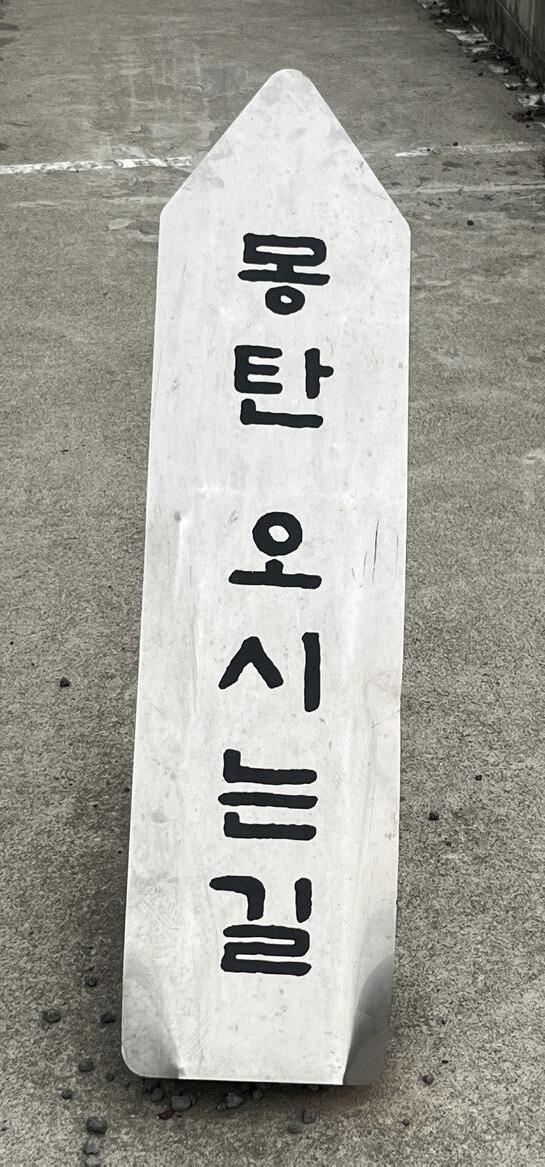

The Best Korean BBQ in Korea: Mongtan (Jeju)

Most people go to Jeju for seafood. After eating at this restaurant, you’ll be joining the ranks of those who go to Jeju for barbeque. Mongtan’s Jeju location serves, simply put, the best barbeque I’ve ever eaten. Ever. Stepping into the dark, dimly-lit restaurant, you’re greeted by the sight of three stone faces. As you take in the scene, the crackling sounds of the fire and the nutty aroma of the roasting straw immediately hit your remaining senses in full force.

There are exactly two things you need to order: Jeju black five-layered pork and the straw-grilled beef short ribs. I’ve never been impressed by Jeju black pork. It’s always been too chewy, and the flavor tastes exactly the same as normal pork belly for double the price. However, I have reason to believe Mongtan procures its pork from a farm that feeds its pigs liquid gold. As soon as you take one bite, the umami-rich juices come rushing out, filling your mouth with a sweet and savory warmness that feels like a warm furnace in the wintertime. Each piece is cut to be the perfect bite size and it only takes three chews before you’re internally crying for another piece.

Now, the straw-grilled beef short ribs may be one of life’s few miracles. The beef is grilled on straw beforehand, which gives it a light, clean smoked flavor that compliments the sweetness of the caramelized flavor. Like cotton candy, the beef immediately melts in your mouth and suddenly, you are standing at the top of a vast wheat field, a warm autumn breeze caressing your skin. While beef is usually more expensive at Korean restaurants, the minute we took one bite, our whole table was in sync and ready to order another round of the short ribs. Truly, heaven is just a bite away.

꿀팁1: It’s reservation only, so be sure to snatch a table via the Catchtable app. If you can, visit on a weekday.

1 Kkul tip, Honey tip, a useful piece of advice.

The Most Comforting for the Homesick: Hersband (Namhae)

I have a love-hate relationship with the pizza in this country. I refuse to acknowledge sweet potatoes and honey as legitimate pizza toppings, but I will scarf down a bulgogi pizza like it’s my last day on earth. I know, I know — this detour to pizza seems odd. "South Korea is home to an abundance of traditional dishes that are just as flavorful and compelling and should be shared with the world!" I agree, but spare me a second because this review is specifically for my fellow international residents, homesick travelers and people who want to be transported to another country for an hour.

Hersband, a little pizza and coffee joint located off the west coast of Namhae Island, is a must-hit spot when you visit the area. As you drive up to the restaurant, you’ll notice the forest path opening up to the ocean, children running around and people chatting on the terrace sharing a pie. The windows are all open, allowing the scent of pizza and roasted coffee to wash over you just as the waves splash over the rocks a few feet away.

After a short wait, one pizza glistening with oil and a slightly charred crust arrived in front of me. When you pick up a slice, the cheese fights to stay on, blessing you with the sight of a beautiful cheese pull. The pepperoni gives the pizza a slight kick, with the taste of paprika peeping through the cheese. The pizza in Korea tends to be on the bready side with a thick crust. This place rolls out their dough so the center will be in perfect ratio to the topping and the crust slightly poofs up like a fluffy pillow. It’s not often I will eat one whole pizza by myself in one sitting, crust included. However, I inhaled my slice, proceeded to devour the remaining seven and put myself into a food coma. One pizza, a cold beer and a view of the ocean leaves nothing to be desired.

꿀팁: The restaurant is small, so try to go during off-peak hours if you want to sit at the counter with the ocean view.

The Best Homemade Food on a Budget: Kitchen Bomnal (Seoul)

Tucked into a corner in Sinchon towards the main gate of Yonsei University is Kitchen Bomnal, a cozy little shop that exclusively sells kimbap. You will see students, office workers and delivery drivers constantly coming and going, their arms full of boxes. This takeaway- only shop is known for its cheap prices and kimbap rolls bursting with flavor.

After a long day, sometimes a simple and cheap home-cooked meal is all you crave. Kitchen Bomnal is where you can feel like going to “eat out,” enjoy a real meal and find a small happiness through each bite. As you stuff a piece into your mouth, you finally understand the Korean concept of jeong 2 . The warmth and love of the owner exudes through the piece; it’s so big you’re almost unable to fit it all into one bite. Bursting with tuna, egg or crab, every bite is reminiscent of the stained glass windows of the Sagrada Família.

Now, you may argue that any place can make good kimbap. It is pretty hard to mess up kimbap; after all, it’s only rice, seaweed and whatever filling you want. However, the filling is where most places fall short. So many places make a super dry kimbap, skimp out on the filling or mostly give you rice. However, Kitchen Bomnal’s kimbap is so delightfully moist and incredibly full of filling. The ratio of rice-to-filling is closer to 1-to-99. I sometimes wonder if the owner is operating at a loss given the quality for the price. Eating here, I am caught in the realization that no matter how fancy the restaurant or expensive the ingredient, ultimately, we yearn for the homemade food of our childhoods. It is such a simple dish, and yet, this kimbap will induce a smile, if not tears, and undoubtedly a flood of emotions.

꿀팁: On the weekends, the store closes early! Also, they take orders online via Naver, so you can order ahead and pick it up. Otherwise, you’ll find yourself waiting at least 30 minutes.

2 정, a warm affection, rapport, or attachment connecting people.

Hwasun

Sunrise Quiet, Kavya Kumaran, Hwasun, Jeollanam-do

Morning Runs in the Rain, Kavya Kumaran, Hwasun, Jeollanam-do

Gangneung

With Loved Ones, Eden Perez Bonilla, Gangneung, Gangwon-do

Hot Summer Sunset, Rachel Hudson, Uido, Jeollanam-do

Sammy Seung-Min Lee:

“Fulbright Wasn’t Just a Chapter — it Was a

Hinge”

By Eden Perez Bonilla

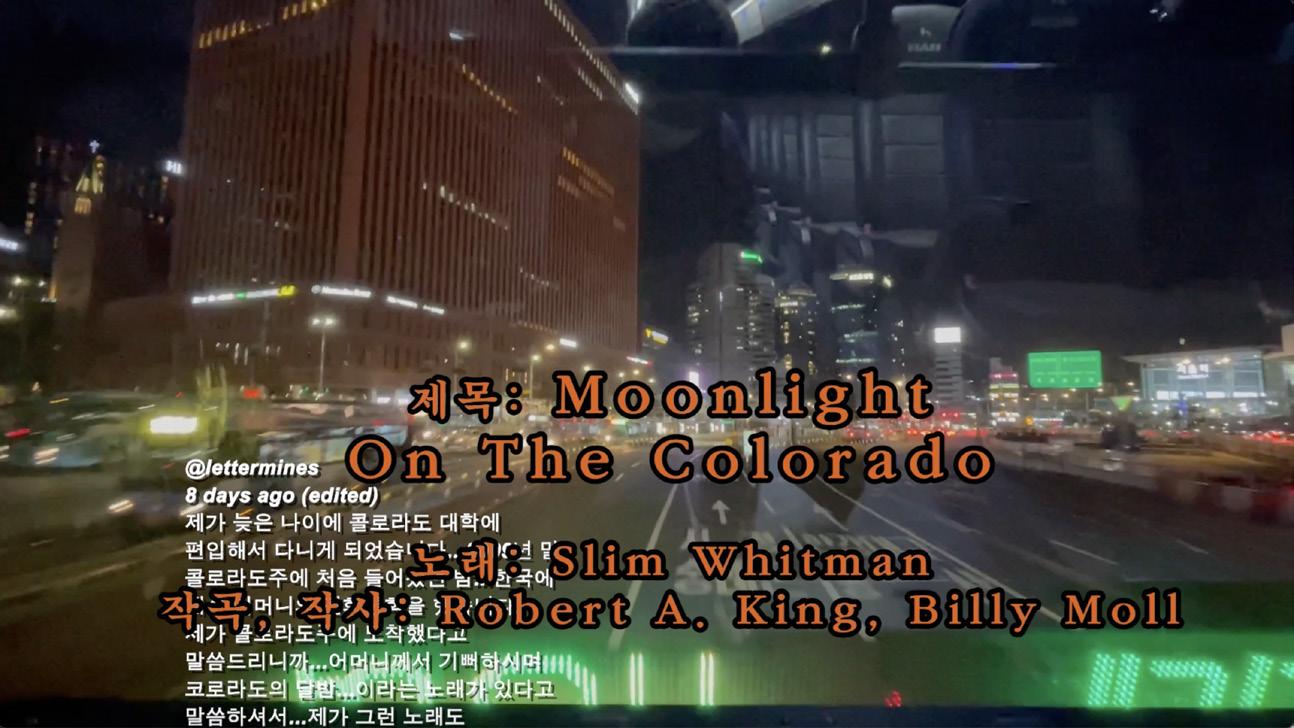

I myself love art. I have made it casually my whole life and became curious to learn what a Fulbright grant year would look like for a practicing and established artist. I came to learn that Sammy Seung-Min Lee was in South Korea for a year from 2023 to 2024. In her own words, her art “moves between paper, installation, and video — threading together themes of identity, displacement and belonging.” She is well recognized, and any summation of her accolades will not do justice to the breadth and scope of her work. Her work ranges from an exhibition at a local farmers’ market to a collaboration with Yo-Yo Ma and a fellowship with Ewha Womans University. I reached out through email to ask more about her work in Korea during Fulbright and the following are her responses regarding an exhibition she worked on based off a song with the same name, "Moonlight in Colorado." I also asked about her thoughts and outlook post Fulbright, a time which marked her first return to Seoul since having left as a high schooler.

How did "Moonlight in Colorado -Karaoke" come to be, both conceptually and physically?

It began with a song — an old American folk tune, "Moonlight on the Colorado" — translated into Korean and adored by my mother’s generation after the Korean War. For them, it conjured a romanticized image of a faraway America, especially Colorado, which most had never seen.

I was fascinated by the irony: my mother’s nostalgic fantasy of Colorado eventually became my very real home. The karaoke video grew out of that irony. I filmed drive-through footage in both Seoul and Colorado and paired it with mismatched subtitles — sometimes misaligned, sometimes intentionally mistranslated, even censored. Conceptually, it mirrors my own condition: you think you know the lyrics, but you’re always a little out of sync. I imagine many immigrants would relate. And of course, karaoke isn’t fun in solitude — it’s about singing through the misalignment together.

Karaoke, photo provided by the artist

You mentioned in a previous Fulbrighter interview that you initially intended to research “traditional Korean art materials — especially hanji paper and its varnishes,” which was in line with your previous work. Why the switch to digital media?

It wasn’t a switch so much as an expansion. I went to Korea intending to deepen my relationship with traditional materials, and I did. But living in Seoul again stirred questions that couldn’t be answered solely through paper and glue. Digital media — karaoke, video, mistranslation — gave me a sense of playfulness. I wanted to wrestle with heavy ideas about history and identity, but with humor. Karaoke became a vehicle for that absurdity of diaspora, inviting audiences to join in. And yes — I came home with plenty of research on hanji, but I’m grateful Fulbright supported pivots when new directions were called.

"Moonlight in Colorado -Karaoke" shows footage of Seoul and Colorado landscapes, in a sense focusing visually on physicality despite the digital media. Your previous work has used impressions and replicas as well, not to mention your work that discusses housing. Did your grant year influence your relationship with physical space and the role it plays in your artwork at all?

Absolutely. Fulbright made me acutely aware of physical space as a container of memory. Walking through Seoul past my old school

and the park where I played reminded me that streets themselves are memory archives. That realization seeped into the karaoke piece: Seoul and Colorado became visual foils, landscapes of longing and belonging. My housing-related works have always dealt with home or shelter as metaphor; Fulbright pushed me further, to consider where we walk, where we live. These aren’t neutral backdrops, they’re stage sets for identity.

Artist's Books, 2021

"Artist’s Books" in display from "Remind Me Tomorrow," solo exhibition in 2021, Emmanuel Art Gallery, Denver, CO

In your Fulbrighter interview you also mentioned taking your eight- year- old son with you on the grant. Your work has previously touched on motherhood and family more explicitly through pieces like "Changing Station" and "Very Proper Table Setting." Did your grant year develop or change your views of family and immigration, and if so how?

Yes. Taking my son meant that immigration wasn’t just something I reflected on — it became something we experienced together, in reverse. He wasn’t returning to a “lost home”; he was discovering one for the first time.

Seeing Korea through his eyes reminded me that immigration is not a single act of leaving or arriving: it’s generational, unfolding differently for each of us. My earlier works approached motherhood through daily rituals within domestic space. Fulbright stretched that view: how family itself becomes the vessel that carries migration forward — sometimes awkwardly, sometimes beautifully.

Very Proper Table Settings, 2017-2023 (ongoing)

Photos from "Taking Root," solo exhibition, Kemper Gallery, Denver Botanic Garden, Denver, CO

Hanji (Korean mulberry paper) and acrylic varnish 29 x 93.5 x 35 inches

At various venues, I invite strangers to create imaginary meals for loved ones using Korean dinnerware, inspired by my own search for the perfect bowl as a new immigrant. Participants often struggle to convey their customs within dominant cultures, and this process fosters curiosity, empathy and appreciation for cultural differences.

Community seems to be very important to you, as evidenced from previous artwork and even exhibiting art at a farmer’s market. How did you find community during your grant year?

Community came in layers. I had a handful of childhood friends in Seoul. I met teachers and parents through my son’s school. I taught through my host institution, meeting students and professors. I got to know neighborhood vendors, pharmacists and had other encounters by living there. But I craved an art studio, and until I landed an artist residency in Euljiro, I felt unmoored. That residency rooted me. Artists there shared resources and opportunities generously; friendships grew that continue despite the 6,000 miles between us. And the Fulbrighters — our mix of disciplines created perspectives that fed directly into my work.

How would you compare your artistic process prior, during and post Fulbright?

Before Fulbright, my process was solitary, studio - bound, squeezed between school drop - offs and pick-ups. During Fulbright, it became porous: collaborative, improvisational, responsive to place. Now, I carry both modes. I’m still unpacking layers from my Fulbright year, actively creating works from it. I’m more open to unpredictability, detours and dialogue because I’ve seen that’s where the most exciting work often emerges.

Euljiro, photo provided by the artist

Euljiro, photo provided by the artist

Would you say you’re still drawing inspiration from your time with Fulbright? How so?

Yes, constantly. Fulbright gave me a vocabulary I didn’t know I needed, and I’m still speaking it. "Moonlight in Colorado" continues to anchor my work. My upcoming Museum of Contemporary Art Denver exhibition expands directly from what began in Korea. Fulbright wasn’t just a chapter — it was a hinge. My practice keeps swinging back to it.

Where may readers find your work?

My work can be found at www.studiosmlk.com. I’ll have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver in 2026, anchored by "Moonlight in Colorado." I also share updates on Instagram @sammy_seungmin_lee.

If there is anything else you would like to share please do so.

Only this: Fulbright wasn’t just a grant, it was a gift of time. Time to walk old streets, time to question memory, time to build something new from fragments. And in that sense, it wasn’t only my story — it was my son’s, my collaborators’, my community’s. That’s the beauty of it: you leave with more voices than your own.

Sheltered, Arrived, series, 2016 (ongoing)

Photo from "Breakthroughs: RedLine at 15," Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver, CO

80 suitcases, mulberry papers, acrylic varnish, reflective chrome vinyl marking 150 sq ft, a space defined as an “adequate shelter” per Colorado law.

"Arrived, series" explores the experience of migration through an assemblage of broken suitcases wrapped in a leathery paper-skin substrate. I draw from my own memories of immigration from South Korea to the United States, as well as the shared experience of diaspora. "Arrived" reflects on the symbolism of the suitcase, as a marker and remembrance of the journey from one’s home to a new place, often filled with the most essential and precious remnants of the life one is leaving behind.

In this iteration of the ongoing series, I added a vinyl flooring element beneath the suitcases cut 150 sq. ft. This dimension mirrors the minimum dwelling size for an “adequate shelter” as stated by Colorado law. The creative process resembles my experience of (un)conforming to a new homeland; it calls for certain self-renewal while summoning and translating the past. As a first-generation immigrant who spent much of her youth in a nomadic state, I use found objects and memories as material to investigate a sense of home.

Gyeongju

The Sun Sets on Anapji, Rose Nelson, Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Sangsan Koi, Rose Nelson, Jeonju, Jeollabuk-do

Jeonju

Pohang

Pleading with the Storm, Laura Evans, Pohang, Gyeongsangbuk-do

Mokpo

Made It, Samantha Fabian, Mokpo, Jeollanam-do

In Korea, I Try Talking to My Ancestors; I Only Hear Physics

By Gabriella Son

Newton once theorized that opposite reactions cannot be un equal.

Three centuries later colonized time and space: humanities teacher instructs Korean not

Reaction: my great-great- grandfather executed my great-great- grandmother executed: his wife

Military police no decency to hang them right-sideup homeland last glimpses: overturned defeated. That man so patriotic: refuses losing to any force gravity even tries convincing village still alive in circles teetering pacing around stoic oak devising next hangul rebellion mouth sags in ㅗ: Protest.

Wife peers through quivering branches: ㅏ ㅑ head bowed to husband tied up so high

Great-grandmother sister try gymnastics bring parents back to earth: one-handed handstands aerial cartwheels throw each other in air: rocket missiles

Work like mechanics under starless sky.

One sister unknots straw shackles.

One sister catches bodies in rice sack: free- falling apples I am alive because two young girls defied laws of physics: plowed parents home inside black box force transcending accelerated mass I am alive because two small girls outran speed rising sun. Overnight backyard became graveyard continued lives in motion

In Korea grandmother tries to pass story to me but still learning physics how to stop velocity how displacement changes over time

Dawn Hike, Chris Jang, Gongju, Chungcheongnam-do

Sky at Dawn, Chris Jang, Gongju, Chungcheongnam-do

Continuum

By Jena Mehl

You learn quickly, living abroad, that your home doesn’t wait for you.

At first, it’s easy to pretend otherwise. You imagine your absence as a clean break, a gentle lifting away from the lives you once orbited and that once orbited you in return. It feels, briefly, like you’ve stepped outside of time. Like you’ve pressed pause on the rest of the world while you live in a new country, discover cute Instagrammable cafes and travel everywhere KTX can take you.

But time doesn’t work that way. Distance doesn’t freeze anything, as much as you might wish for it. Life continues, just without you there to witness it. One of your brothers is still a senior in high school. You imagine your friends still sipping chili pepper mochas in that old house-turned- cafe just off campus, where you studied together weekday mornings.

You miss graduations. Your best friend graduates from university. You watch the livestream. The Wi-Fi cuts out as her name is called. When the video feed returns, she’s already holding her diploma. You rewind and watch her walk a minute too late.

One brother graduates from university. There’s no livestream for you to tune into. A different little brother graduates from high school. Another turns 16 and starts driving. Someone messages you a video of the annual family vacation. You’re not there for it.

You’re not there for any of it. Nothing waits for you.

You can’t text a friend at 2 a.m. and ask if they want to get ice cream and watch a movie — they don’t sell pints of Reese’s in the convenience stores here. You can’t meet up for dinner and complain about the exam coming up in your least favorite class. You can’t bring your brother

out as a reward after he gets a good grade on his AP English test.

Your friends begin to drift from the city you all once claimed as your own. The football stadium still glows purple over the river each night, bright above a team that never really wins. The skyline belongs to fewer and fewer of you.

One by one, they find new skylines to call home.