1

Paying tribute to a pioneering designer

100 Years

2

Ditzel 100 years

Good taste?

Lecture by Nanna Ditzel

Ideas become objects

A conversation with Nanna Ditzel

Ditzel was the queen of design in her time

A conversation with Thomas Graversen

Trinidad Chair

A poetic design pushing the limits

A family home full of design and experimentation

A conversation with Dennie Ditzel

Chaconia Chair

Questioning the norm of furniture

Taking design to new heights

Exhibition text by Sara Staunsager

A global citizen with impact and relevance

A conversation with Anders Byriel

Design should raise questions and stimulate curiosity

A conversation with Maria Bruun

A designer breaking the rules

Nanna Ditzel 100 years CONTENTS 02–03 Previous page Nanna Ditzel in her studio in Klareboderne, Copenhagen 04–13 14–15 18–29 30–35 36–53 54–61 62–65 66–69 70–73 74–79

02

A designer breaking the rules

Fondly known as the “grande dame of Danish Design”, Nanna Ditzel (1923–2005) is considered one of the most influential Danish designers of the 20th century, whose style never stopped evolving throughout her more than 60-year career.

Celebrating the 100th anniversary of Ditzel’s birth, Fredericia pays tribute to this pioneering woman and our former main designer, honouring her collected oeuvre and showing a remarkable world citizen.

A woman who challenged the comme il faut of design and succeeded in leaving an enduring dash of poetic lightness and artistic innovation in the Danish design tradition.

03

Left

Nanna Ditzel

Ditzel

100 years

Nanna Ditzel in Trinidad Chair

Nanna Ditzel in Trinidad Chair

06

Nanna Ditzel has deservedly positioned herself in the history of design due to her many striking and innovative designs across centuries and disciplines. Being a generation after legendary architects and designers like Børge Mogensen and Hans J. Wegner, Ditzel also studied under the master architect and designer Kaare Klint at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts after graduating as a cabinetmaker and while studying as a furniture architect at the School of Arts and Craft. Even though schooled by Klint and his modern functionalism, Ditzel quickly broke out of the strict and formal design rules going for poetic and sculptural shapes rejecting the “masculine” ideals in favour of softness and rounded shapes. Experimenting with intense colours, new materials and the norms of space and design, she was challenging traditional thinking with her prolific output throughout decades. Leaving a clear mark on both private homes and public spaces and making her a distinctive voice and one of the most accomplished Danish designers spanning over 60 years as a designer from furniture and jewellery to silverware, glass and textiles being the first woman to design for Fredericia, Kvadrat and Georg Jensen.

In a strongly male-dominated furniture industry, Ditzel claimed her place. Together with her fellow student and later husband, Jørgen Ditzel, she already participated in the Carpenters Guild’s annual exhibitions during her studies as a furniture architect at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. After graduating in 1946, they establish their own design studio. Ditzel challenged the design orthodoxy and became a leading figure in the renewal of Danish design and the functionalist design traditions in the

1960s. As part of the new generation, including her husband and Verner Panton, they all distanced themselves from the general perception of good taste in Danish design, creating avant-garde furniture as space-forming architectural elements. Demanding imagination and vision, Ditzel’s designs were sculptural, experimental, and organic, with nature being a continuous source of inspiration. When Nanna’s long-time husband and design partner, Jørgen Ditzel, passed away, she reinvented herself as a solo designer exploring new materials and designs. In 1968 Ditzel diversified again when she moved to London. While running her design studio, she also ran the acclaimed Hampstead store Interspace gallery with her second husband, furniture dealer Kurt Heide, owner of the eponymous design shop Oscar Woollens on Finchley Road. Being a first mover importing international design, Interspace was a gathering place for global design names.

After almost 20 years of living in London, Ditzel moved back to Copenhagen in 1987 after the death of her second husband. In 1989 Ditzel began working with Fredericia entering a new chapter of her career with technically sophisticated furniture. Her openness to experimentation and uncompromising design led to various innovative pieces as designer at Fredericia. Several pieces, such as the Bench for Two, Butterfly Chair and the Trinidad Chair, quickly received global recognition due to their visually unconventional look, poetic sense and highly technical solutions, opening new shapes in wood and plywood, leading her to become a massive inspiration for the new generation of Danish

07

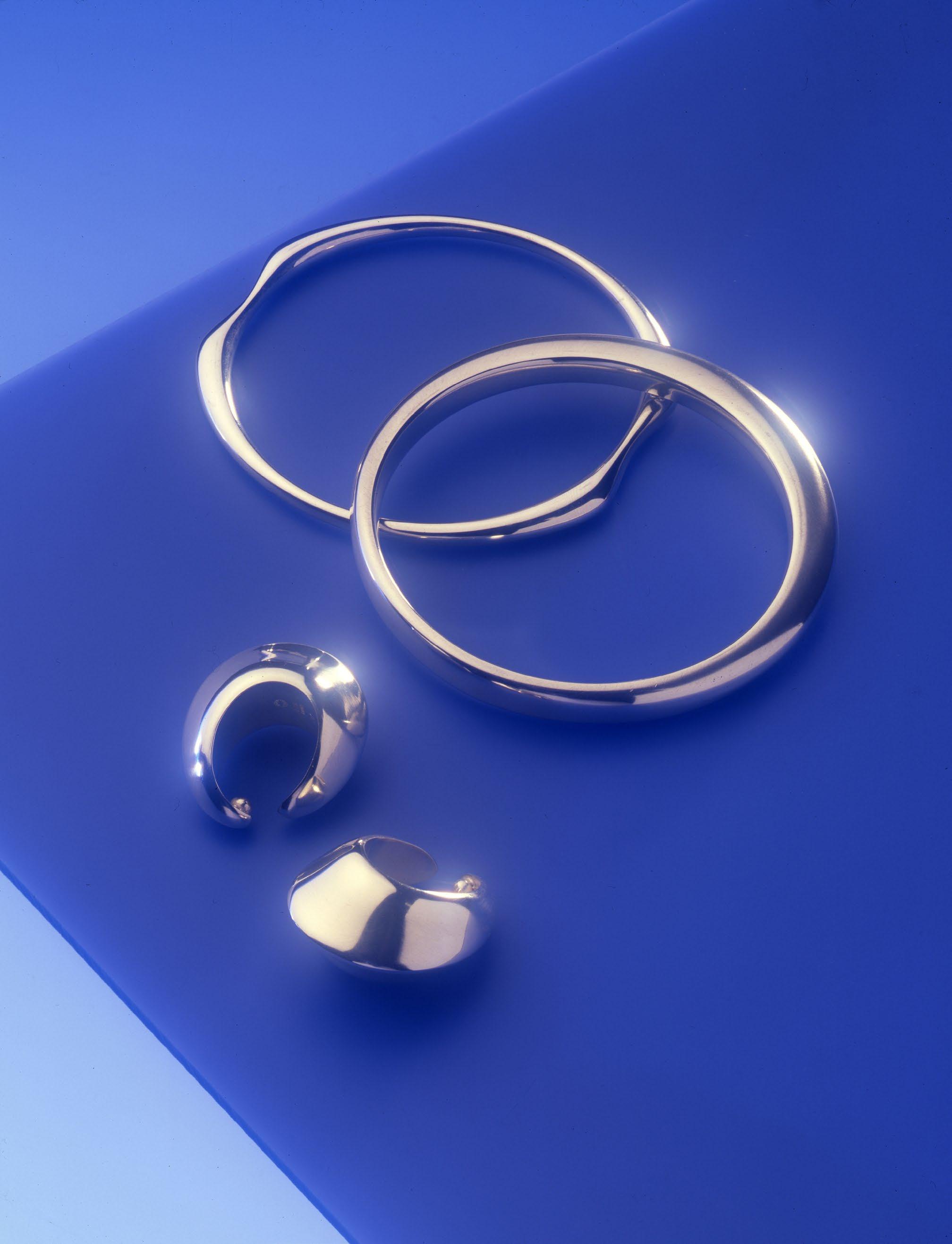

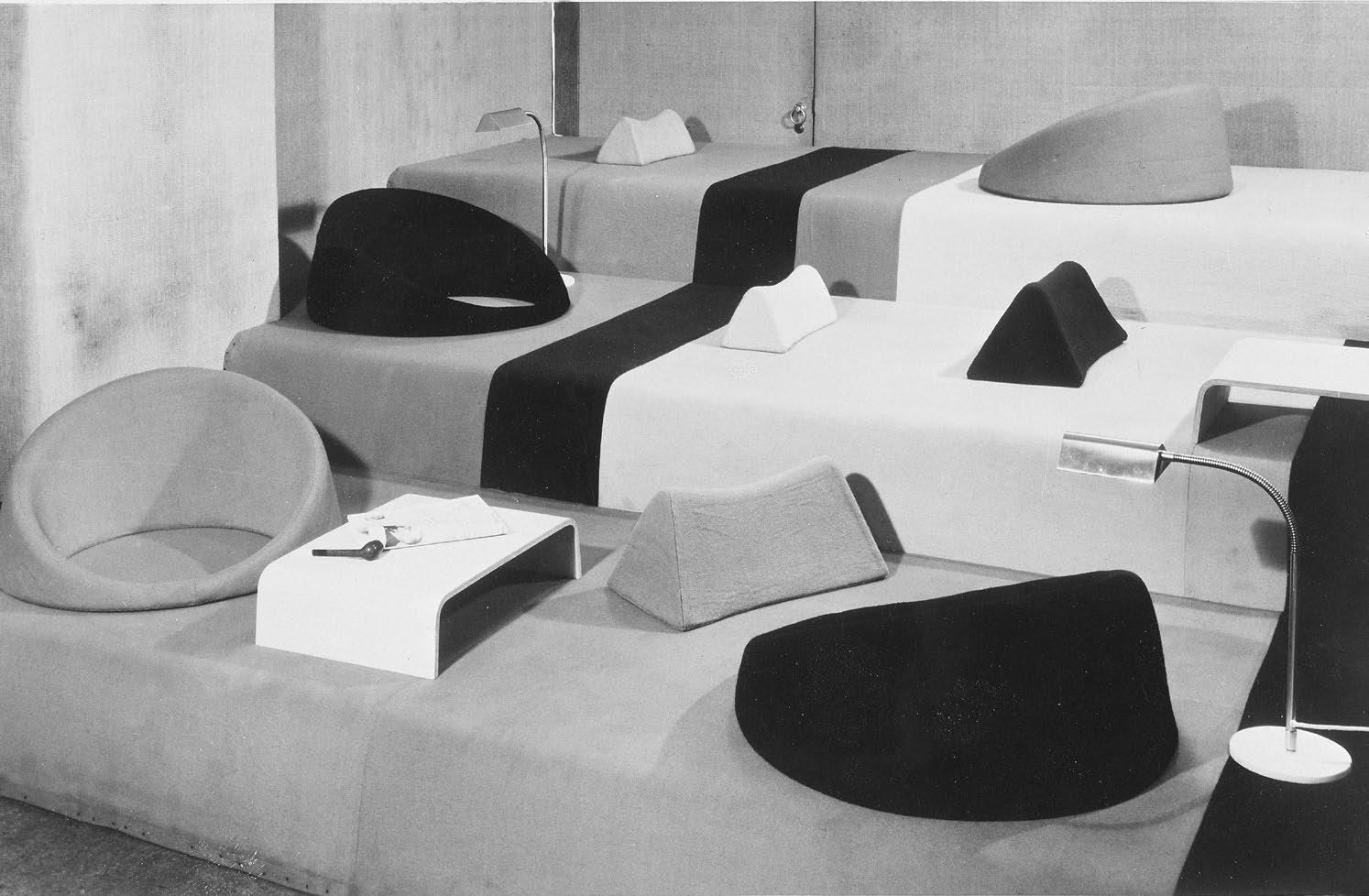

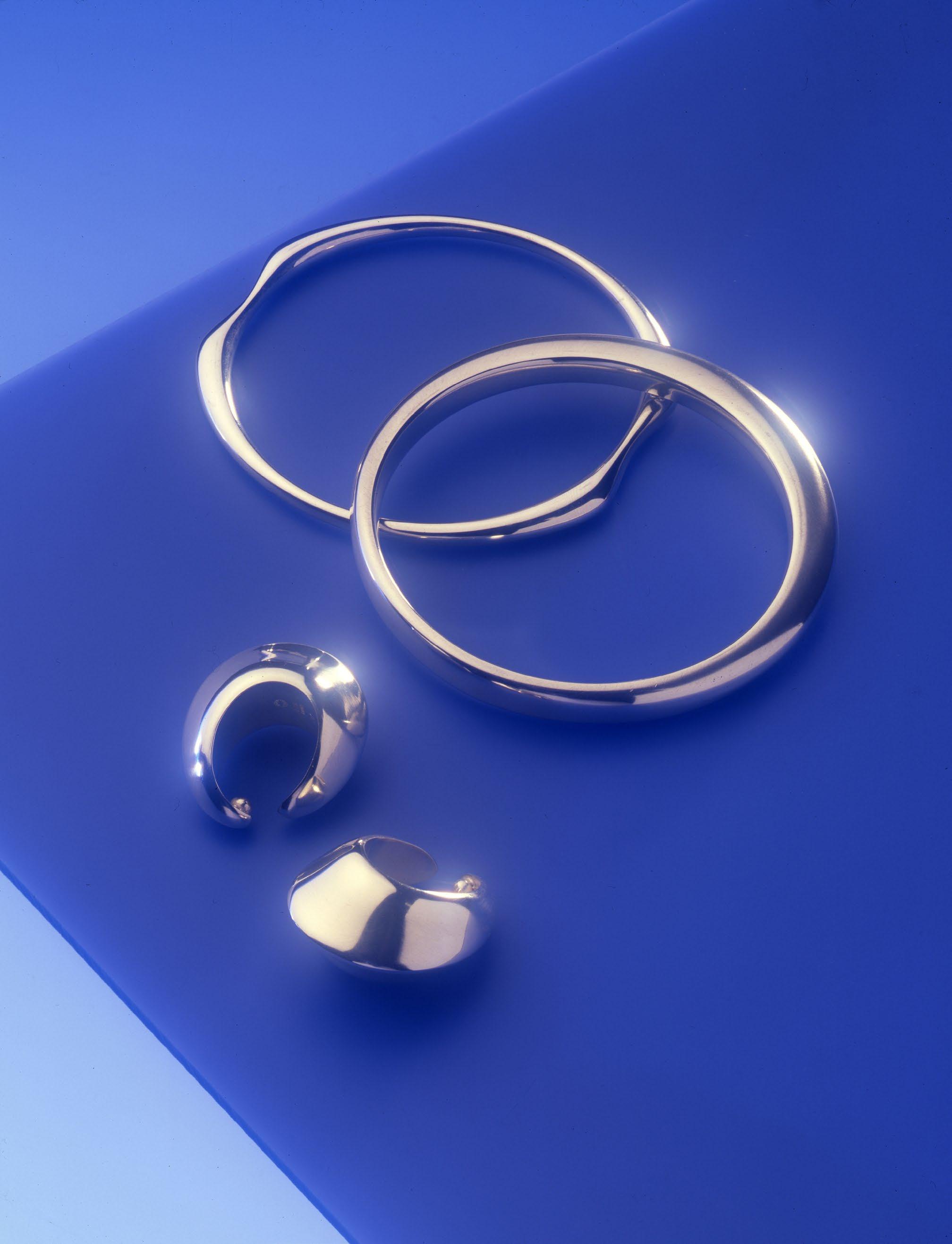

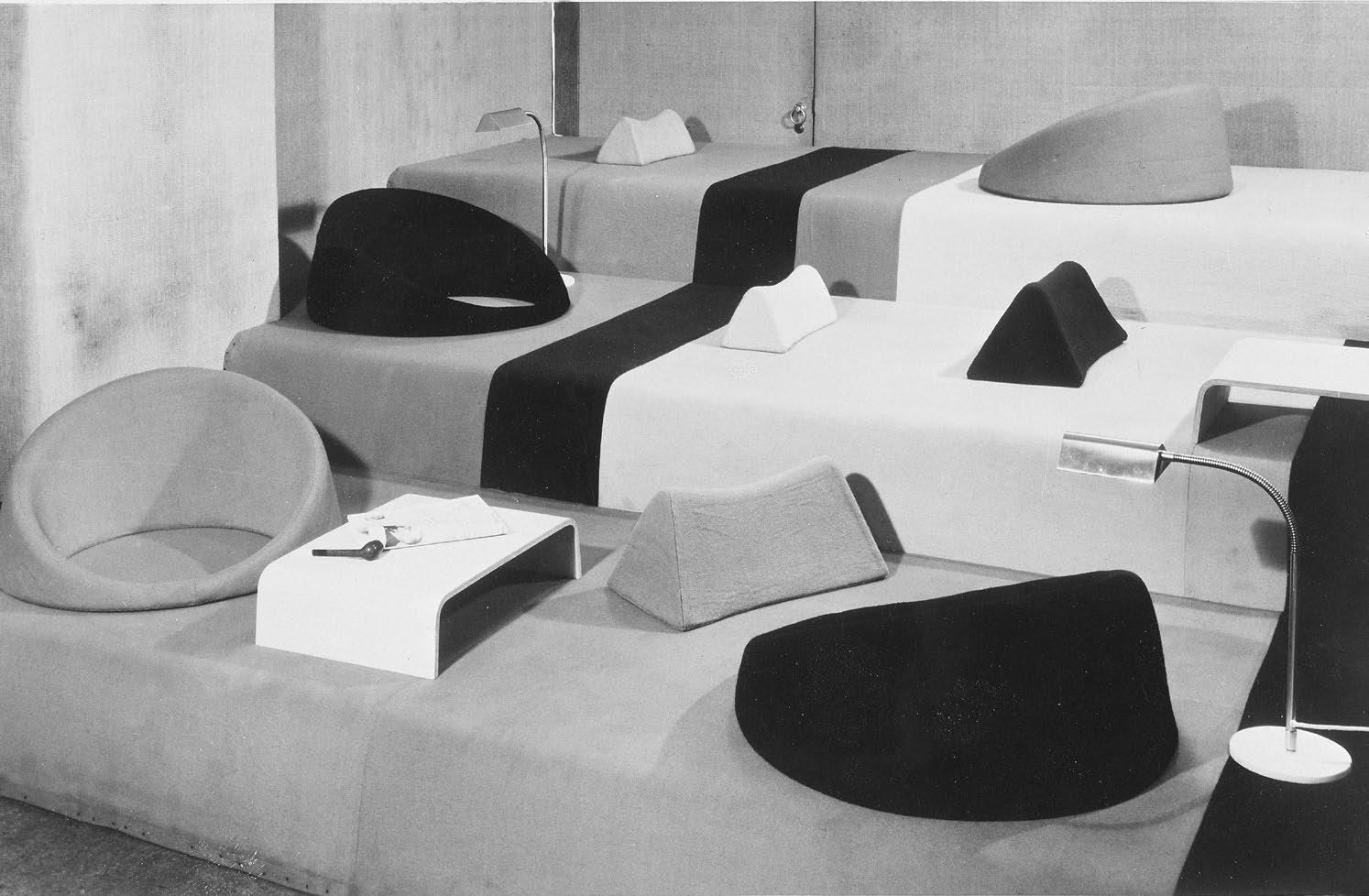

Left Jewellery designed for Georg Jensen Above Moulded foam and rubber elements designed by Nanna and Jørgen Ditzel for Knud Willadsen, 1952

designers. Especially the Trinidad Chair has become a modern classic and, being an immidiate commercial success, it is now one of the bestselling Danish chairs ever.

Thomas Graversen, the owner of Fredericia, close collaborator and friend of Ditzel, explains: “Sometimes, she took things further than you thought you could do technically. She was taught as a cabinet maker but was truly an industrial designer, and she kept pushing until she got what she had envisioned,” he adds. “If you study her back catalogue, she has designed almost everything we use daily, being one of the most versatile talents

of her day. Nanna was the queen of design in her time, which is highly unusual.”

Ditzel’s many distinctive designs have been exhibited throughout Paris, Madrid, Rome, Milan, Washington, D.C., and London, and she has won almost every accolade achievable from gold and silver at the Milan Triennale, Lunningprisen, the Thorvald Bindesbøll Medal, the Japanese International Furniture Design Fair (IFDA), while being appointed to Honorary Designer by the Royal Society of Art in London as Hans J. Wegner and Børge Mogensen.

08

Above Nanna Ditzel’s home and design studio in London Right Bench for Two by Nanna Ditzel, 1989

10

Trinidad chairs at Nanna Ditzel’s home in Klareboderne, Copenhagen

11

Nanna Ditzel’s home in Klareboderne, Copenhagen

12

Nanna Ditzel’s home in Klareboderne, Copenhagen

13

Children’s room in Nanna Ditzel’s home in Klareboderne, Copenhagen

“There is certainly no need to work in the service of current good taste; it is big, broad and doing just fine. On the contrary, we must use our imagination, creativity and our visions of the society to create the things and the environment we believe in.“

14

Nanna Ditzel, 1965

Good taste?

We have learned from Poul Henningsen and other wise men that good taste is one of the worst things you can have, so I’m curious to see if anyone has anything good to say about the phenomenon.

Good taste can take on many different forms depending on the time and place, but fundamentally it is the accepted norms for a particular environment at a particular time and the better you follow and express these norms, the better your taste. This applies not only to clothing, homes and food but also to behaviour and the literature and art you choose. Of course, it is nice to have such norms; they make life easy and safe and give you a sense of belonging. It is a safety net, a learned pattern to use in place of independent judgement. In fact, being told you have good taste can be a dubious compliment because it means you make some pretty predictable choices.

Good taste, as different as it may be in different environments, is as risk-free as a uniform. You take on an identity that is not of your own making.

Nowadays, being a trendsetter is a profession, in other words, predicting how taste will evolve. There is a good chance of guessing correctly by analysing what has happened recently, but fortunately, this is not what determines evolution.

Despite the enormous political and commercial forces of the world, it is astonishing how much influence and impact that individuals or small groups of people can have on global development; for example, the incalculable impact of a philosopher like Karl Marx or, in our own profession, a small group of artists and thinkers who formed Bauhaus 60-70 years ago. All these thoughts and ideas are processed in society and form our pattern.

When the Danish Design School convenes a discussion on taste, I assume it is to find out how to relate to the concept. What can it be used for? Is it a guideline, is it a goal? Of course, you need to be well informed and know what the world looks like at the moment and preferably, why. I visit

museums and exhibitions and subscribe to many publications, but it is not to find out what to do next but rather what not to do.

The prevailing taste has much in common with styles and fashion: They are introduced as and emerge from strong and groundbreaking work, often in reaction to the status quo. After a while, the shock effect wears off, the new is adopted and popularised, finding a generally acceptable expression. And so it continues, whether we like it or not.

So, what we can ascertain as designers is that there is certainly no need to work in the service of current good taste; it is big, broad and doing just fine. On the contrary, we must use our imagination, creativity and our visions of the society to create the things and the environment we believe in. You can do it based on your personal temperament. Some will choose strict and ascetic, but I do not mind if it is fun and festive, and I’m not opposed to pomp and circumstance.

We also have this amazing possibility of picking up paper and pencil or whatever tool we choose to plan and invent things that do not already exist in this diverse world.

15

Lecture by Nanna Ditzel DKDS, Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Design 12th of March, 1997

16

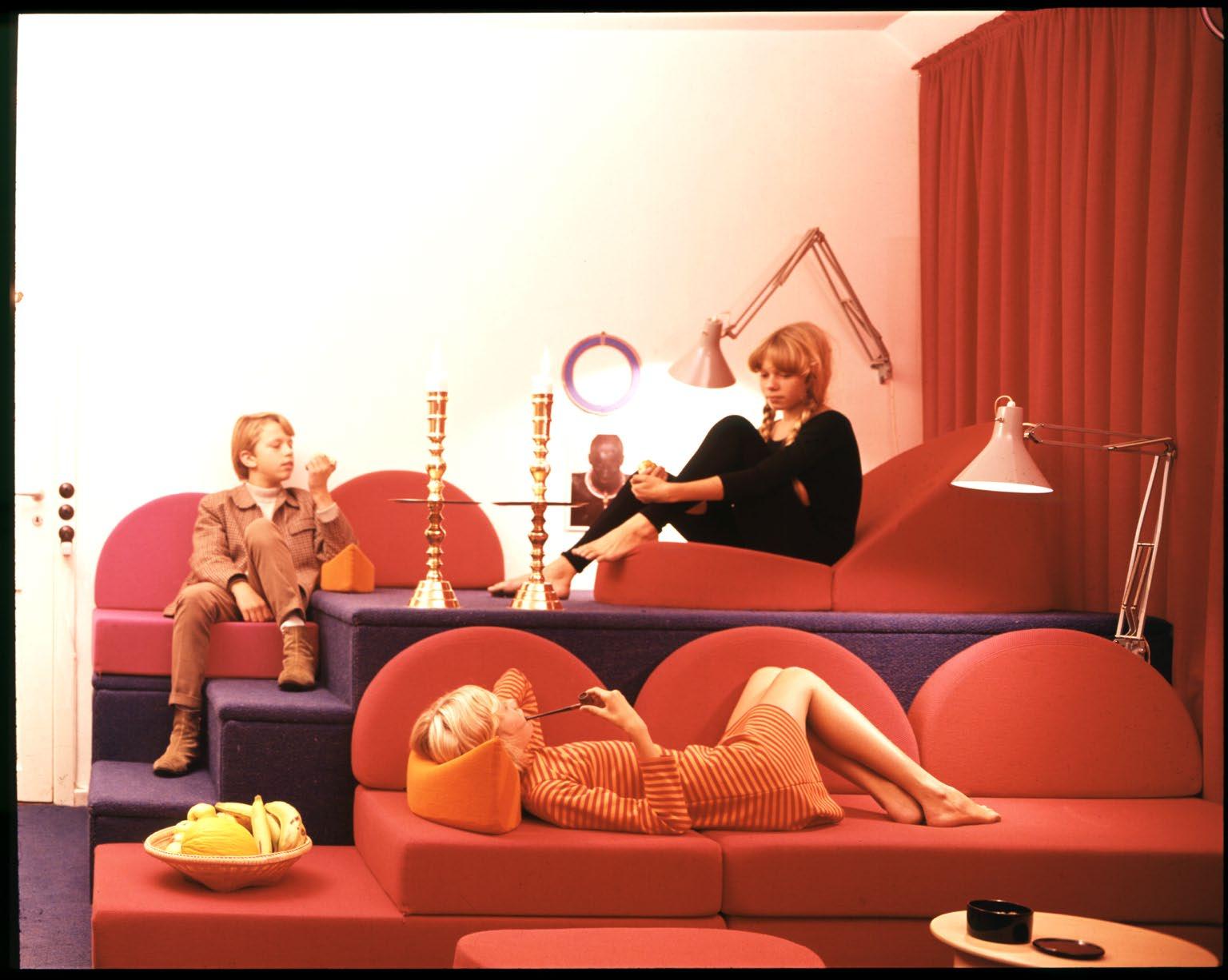

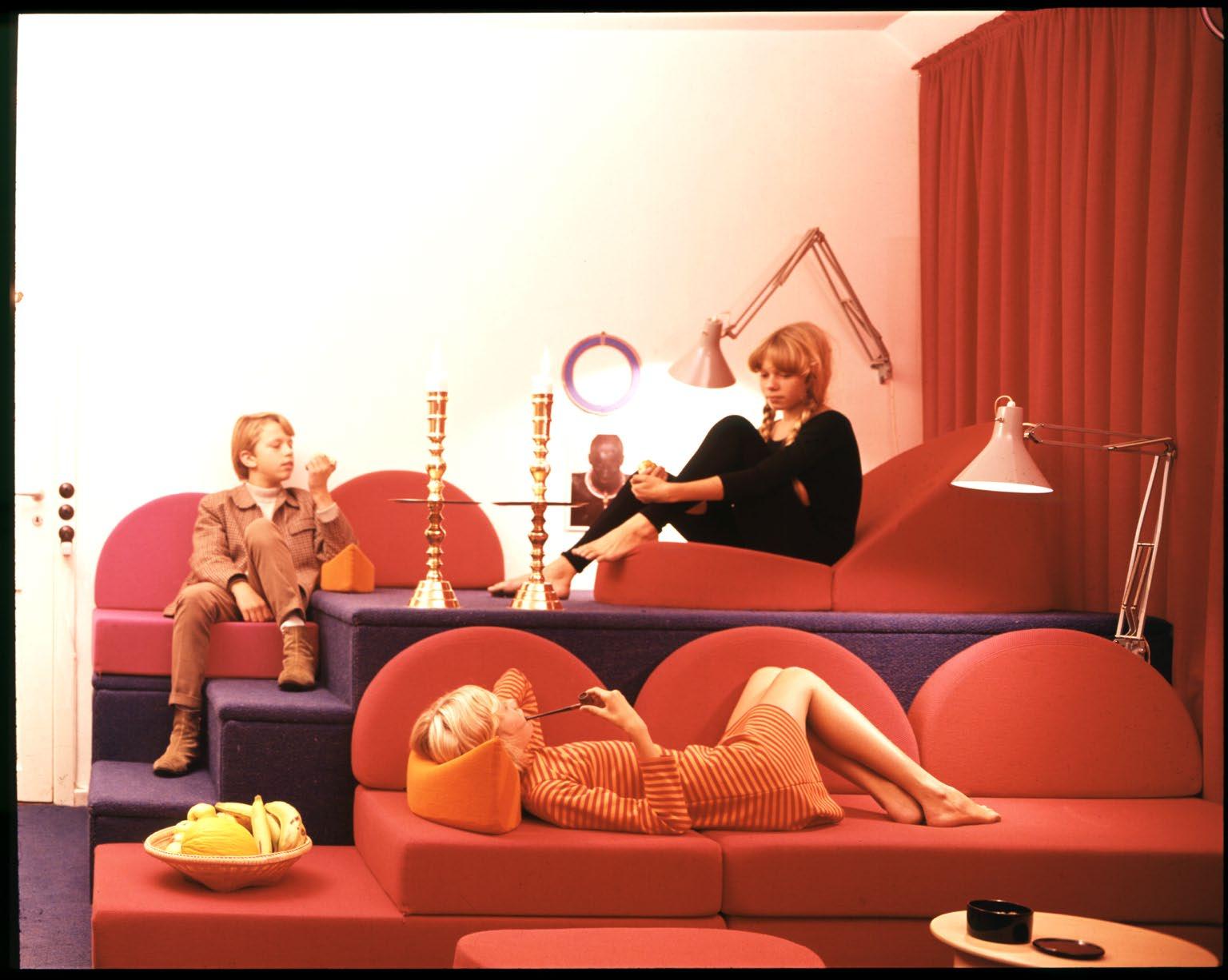

Interior designed by Nanna Ditzel for an exhibition on Danish furniture created by Mobilia in Malines, Belgium, 1965-1966

17

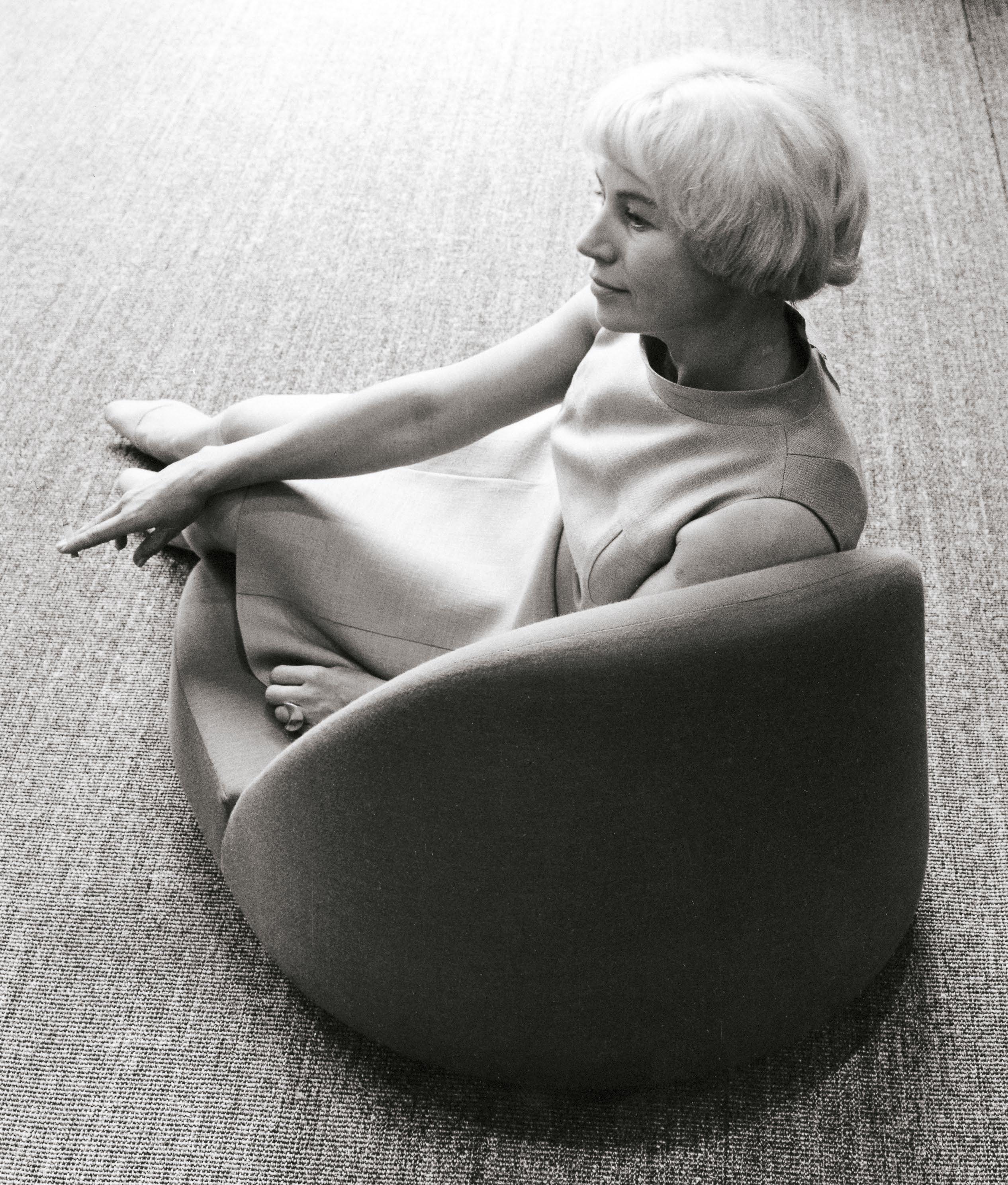

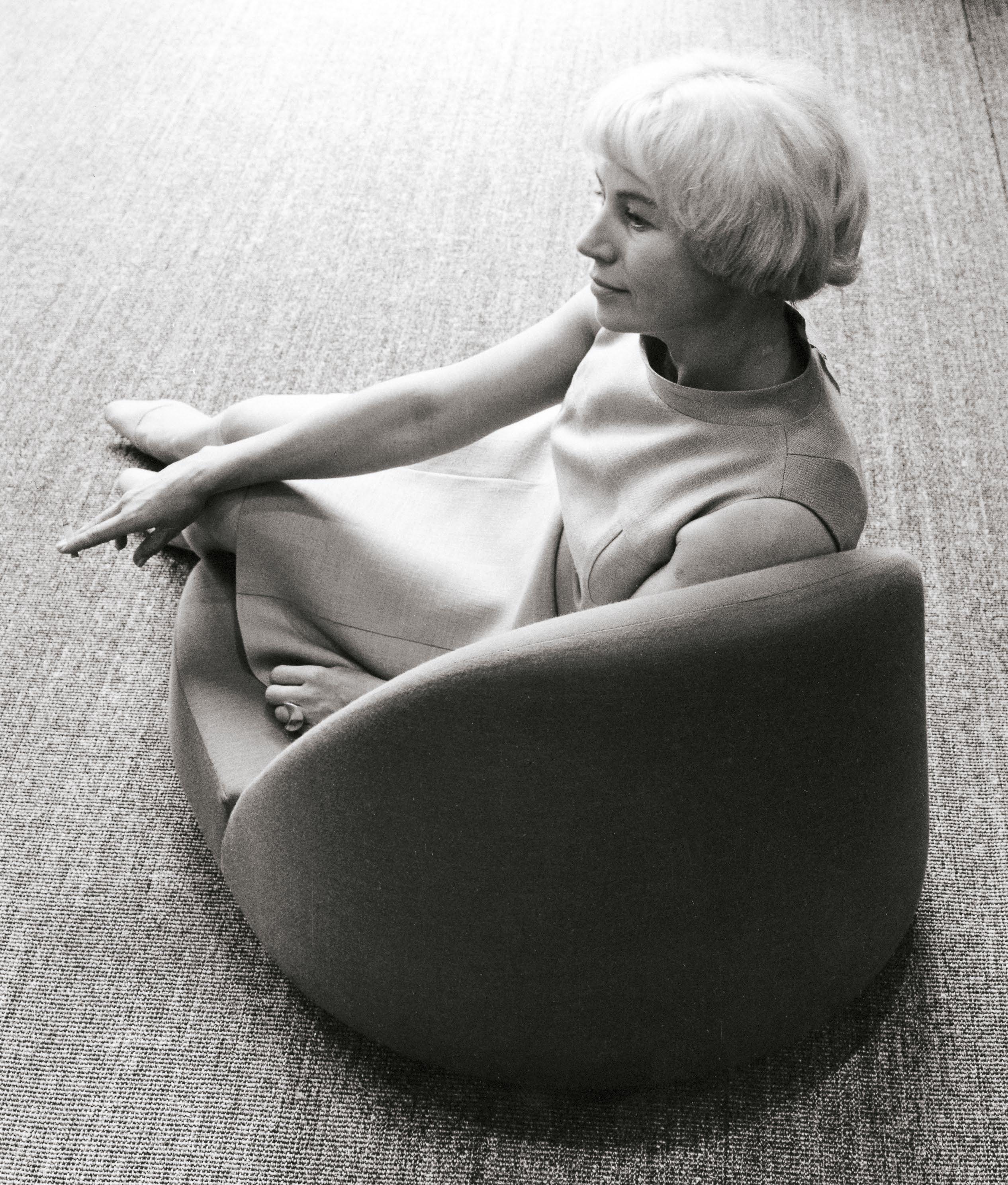

Nanna in Polyether Chair, 1965

Ideas become

18

A conversation with Nanna Ditzel

By Henrik Sten Møller, printed in 1994, Designmuseum Danmark

19 objects

HENRIK How do you work?

NANNA I spend a lot of time looking at the world around me. I observe things that I accidentally come across, but I also make a point of looking at places and buildings. One of my continuous concerns is to find connections. Although my time is now mostly spent designing furniture, I also design all sorts of other things. I have never been able to understand how people can simply devote themselves to a single field – furniture, for example – and overlook all the other things that surround us.

H What is your direct inspiration?

N I can give you an example. During a visit to Tuscany, I saw the wonderful pillars in Siena and the memory of them stayed with me – their shape, the play of light on them, their texture, the ambience, and the material. The result was the new Kvadrat textiles.

H But I suppose it is not just a matter of having a good idea?

N No, but that is the starting point. Then I prepare what I call a concept. I think about the idea, and I write something down. And while my thoughts begin to take shape on the way to becoming tangible objects, I concentrate on two elements in the process, the intention and analysis. I explore all the possibilities: technical aspects, material, shape, function and – something which is very important to me – the human content. After all, the products of my work are going to be used by people.

H What is the first, purely practical step?

N That is to synthesise the analysis. When I have that synthesis, my sole objective is to challenge its validity. To try to reach even further. That is my dream. That is the point at which I set pencil to paper. I spend many days drawing and making notes. I date my drawings, and when everything looks as though it is coming together, I start making models.

H The motivation is inside you?

N Not always. The task is either commissioned, or I decide to undertake it on my own initiative. Both ways work well. The task could, for example, be a new textile design. If so, I am prepared for it. My senses and curiosity are activated. I explore surfaces and material effects, light and shade. And in this way, the Siena pillars become new textiles. It is not simply a copying process. The theme has a content which I admire – and wish to develop further. It has meaning for me because I have seen something in it. Something I can use.

H You have been fascinated by butterflies for many years…

N I have studied them – observed their grace and lightness, their colours and structure, their wonderful floating shapes. They have qualities that I wish to reflect on my furniture. The lightness, the feeling of floating.

H When I first saw your light, floating chairs – the shells – which grace the space occupied like butterflies on a beautiful summer day, I im-

mediately thought of Liselund, the mansion on the island of Møn, where there is floating furniture which blends effortlessly with the marvellous wall decorations, giving the rooms poetry all their own. Was Liselund your inspiration?

N It is a very inspirational place, but I haven’t thought about it in connection with my work in designing furniture. I guess my present designs are an expression of my need to change course. As you may remember, I received my education and grew up in a period in which the only standard applied was function. If the functional requirement was satisfied, everything was fine. Of course, the design must function well, but over the years, I have developed a strong feeling that there is more to every object. To be sure, a chair is for sitting in, but it also expresses age, eroticism, essence, human feelings, and dreams. While functionality must naturally be preserved, for me, chairs have increasingly become attempts to meet the challenge thrown down by all these other elements.

H And is your dream to give furniture this floating quality?

N One day, my grandson told me, “You always buy toys that can fly.” And he was right. I love everything that flies – gliders, kites, butterflies, birds. They express freedom. I cultivate the floating shape in the hope of achieving the effect that I want. But that is precisely what I cannot achieve because of gravity. And the world would probably be a remarkably disordered place if things did not fall back to it as they should! When I was young and newly married, I thought a lot about the need to keep things clean and tidy. One day, I went for a walk in the woods and saw the leaves falling from the trees. A little later, they had disappeared – an ideal arrangement.

H Much of your work not only encapsulates lightness – it has volume too…

N Things have to say what they are. They can certainly provoke surprise, but they must be trustworthy as well. That is an important element in the selection process. The purpose of a chair, after all, is to be sat in. In your criticism, you often have accused us of devoting too much time to designing chairs. But the chair is the most exciting item of furniture. We use cupboards to maintain order. We put things in them. They look after the things we need. But chairs look after people, and that is a quite different purpose. So, it is very important to take into account the way a chair’s appearance combines with the person who sits in it. Some chairs look like crutches. And I don’t like them at all.

H Do chairs inspire you?

N No. Established designs are not transformed into new furniture in my studio because they are already firmly linked to a particular structural concept and specific elements. When I begin work on a new chair, everything is possible; everything is allowed. It’s a challenge. Being tied to a concept which has already been partly developed is not so exciting. There is a poetic strength which means

20

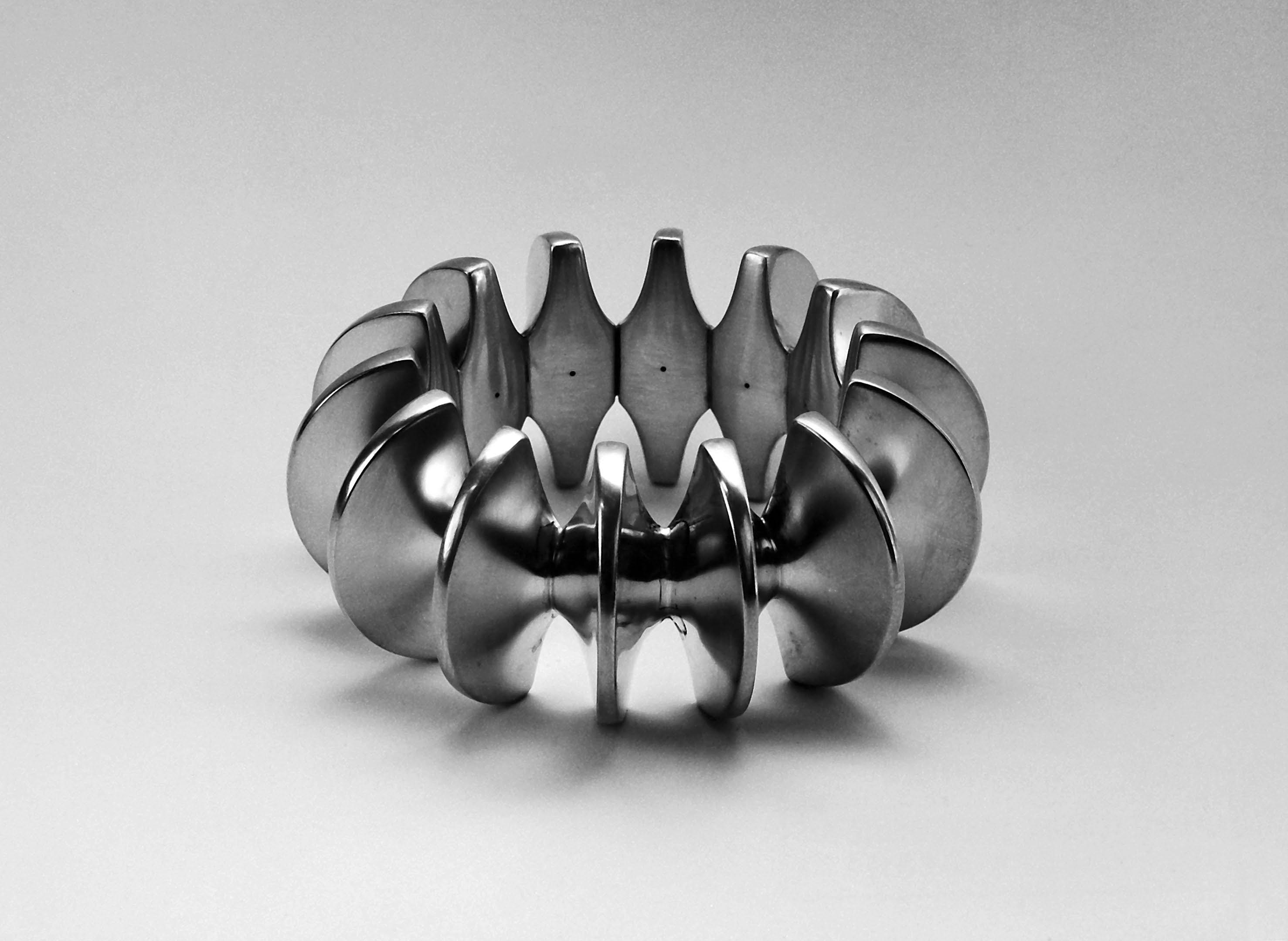

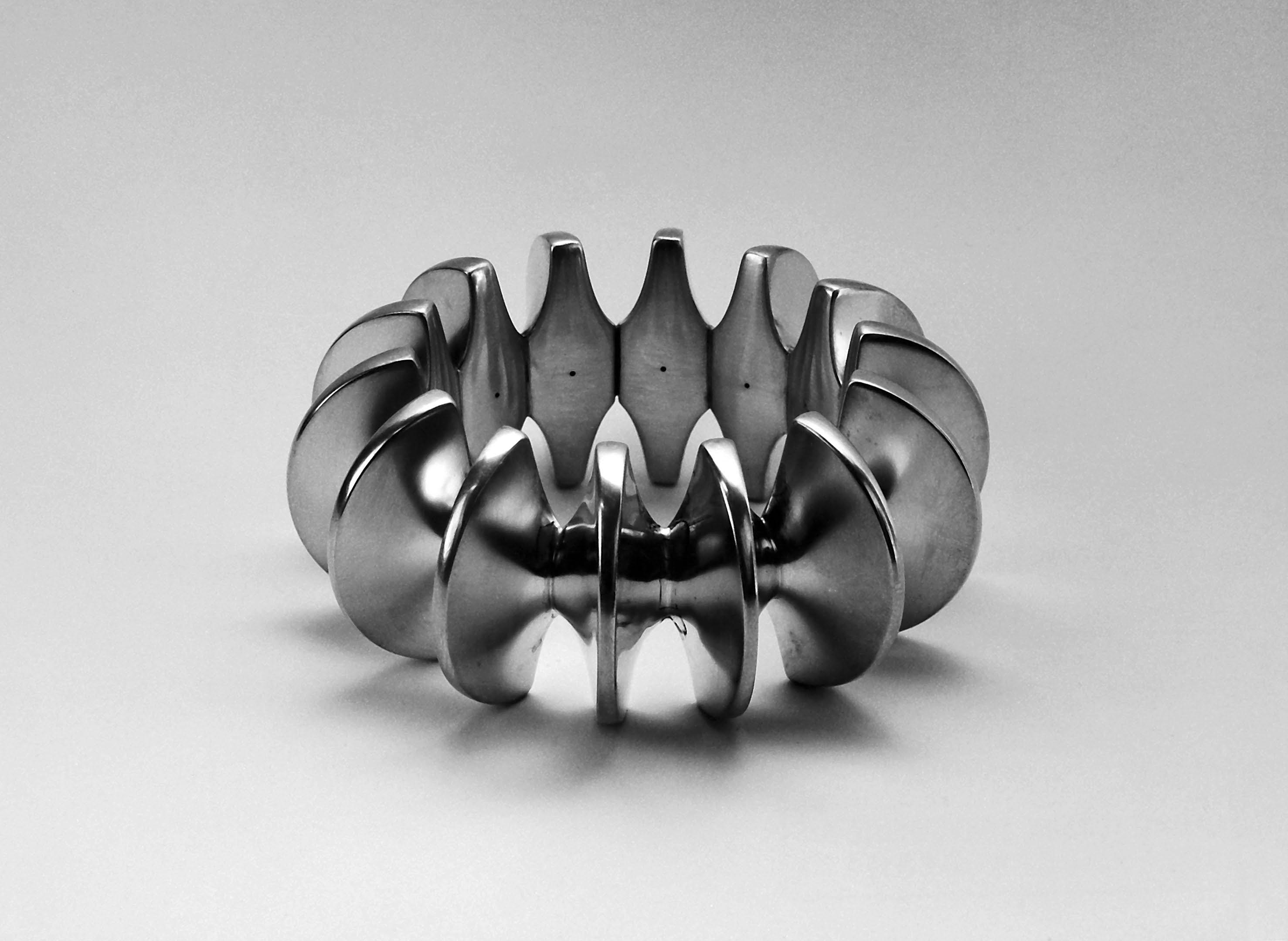

Previous left Silver bracelet by Nanna Ditzel for Georg Jensen, 1960

Previous right Wicker furniture by Nanna Ditzel

a lot to me. Just imagine – you can sit down with paper and pencil and create something that has never been seen before. The same holds true for writing. But we didn’t learn about poetry as a student with Kaare Klint.

H While we were all gripped by the exciting action in Charles Dickens’s novels, Christian Elling described how Nicholas Nickleby, David Copperfield, Oliver Twist and all the rest lived – in their physical surroundings. He was able to work it all out from the text. Have you found direct inspiration in literature?

N No. I am very much a visual observer. I experience shapes and colours directly. I find it more challenging to use the things I read. But it’s strange that you mention Dickens because he has inspired me. As a child, I went to the theatre and saw “Oliver Twist”. With its unknown thieves’ loft, they lived in a space with many different levels. It was the first fantastic room I saw in my life, and I became obsessed with the idea of creating a space

in which people could sit on many different levels. It was an idea I developed further as an adult designer – first with a stepped room in 1952. But, as a girl, I also saw Hans Christian Andersen’s story “The Tinder Box”, with its treasure chest full of jewels. I went home and made jewels of every material I could get my hands on – and I have been designing jewellery ever since.

H What is it that keeps you working?

N The same things prompted me to start in the first place. Curiosity. The opportunity to put something together in new ways. The wish to see what will happen. An appetite for change.

21

Above Nanna Ditzel during production of Polyether Chair, 1965

“When I begin work on a new chair, everything is possible; everything is allowed. It’s a challenge.”

22

Nanna Ditzel’s studio in Klareboderne, Copenhagen

23

Nanna Ditzel in her studio in Klareboderne, Copenhagen

24

Interior of the DSB IC3 Train upholstered with Hallingdal textile designed by Nanna Ditzel, 1987

25

Dining chair presented at the Cabinetmaker’s Guild exhibition in Copenhagen, 1962

26

Butterfly chairs, 1990

27

Nanna Ditzel was fascinated with butterflies and wanted to reflect their lightness and feeling of floating in her furniture

28 Candlestick designed by Nanna Ditzel, 1981

29

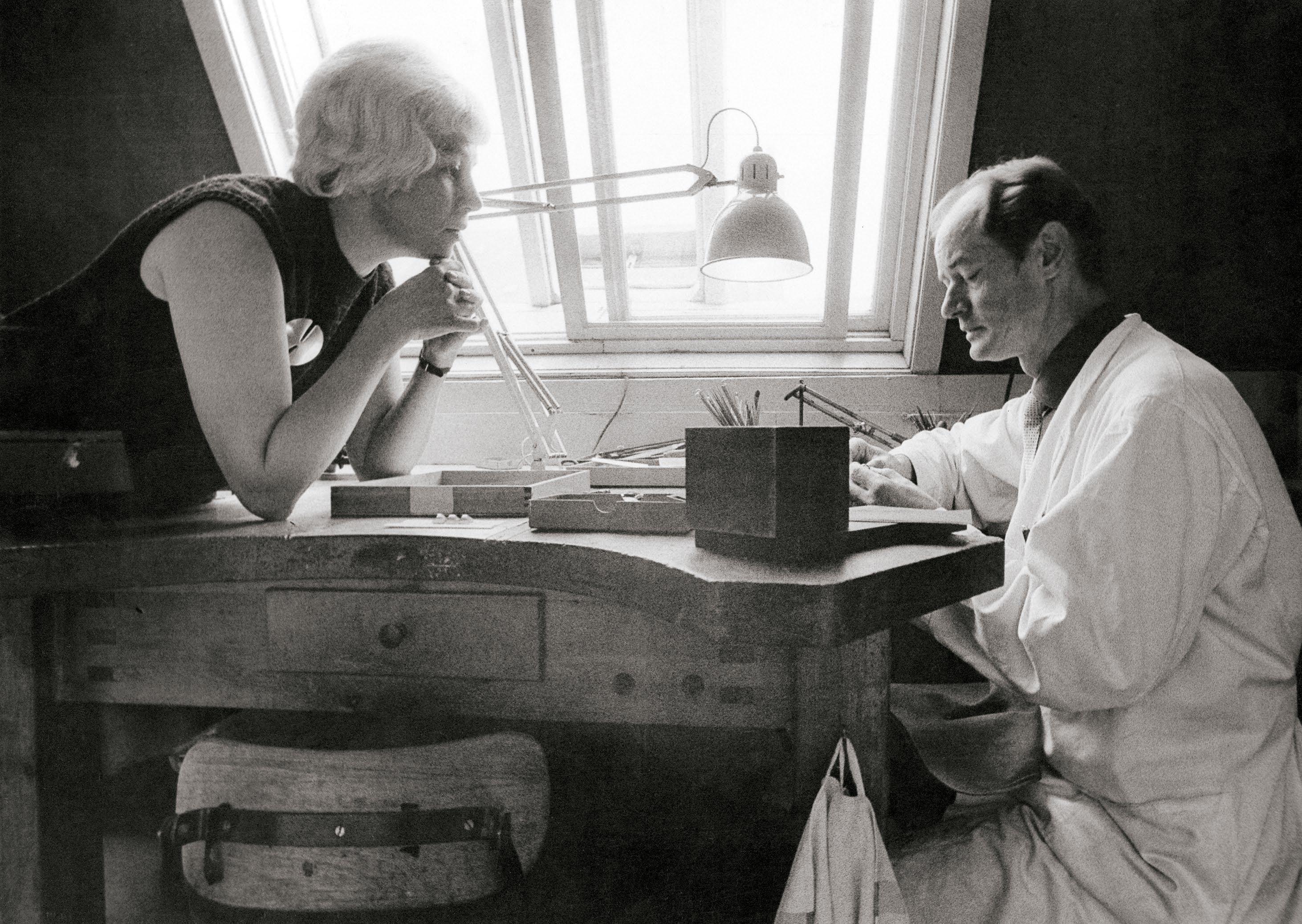

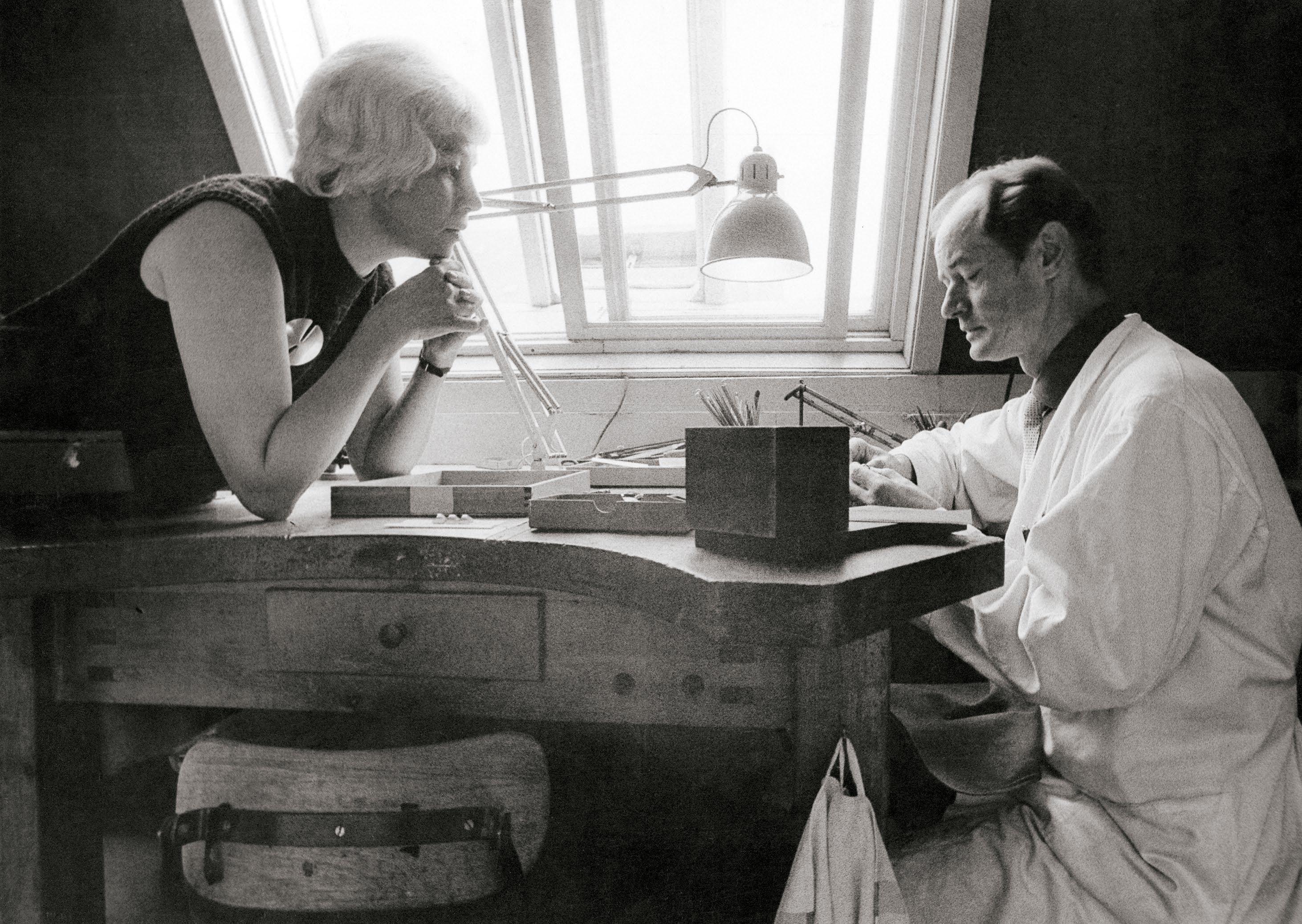

Nanna Ditzel together with jeweller Aksel Jensen in the workshop of Georg Jensen

Ditzel was the queen of design in her time

In 1955, Andreas Graversen merged Børge Mogensen’s modern ideals with his own solid experience to create a close and absolutely essential collaboration for Fredericia. The next generation of the family business reflects this fruitful partnership, as son Thomas Graversen and Nanna Ditzel’s pioneering furniture designs bridge the gap between the historical design heritage and the new contemporary culture.

30

A conversation with Thomas Graversen, Owner of Fredericia

FREDERICIA In 1989, Nanna Ditzel became Fredericia’s main designer after Børge Mogensen. How did this take place?

THOMAS My father, Andreas Graversen, had been searching for a new associate designer for several years. He knew that Nanna had returned to Denmark after almost 20 years in London and they met to discuss the possibility of putting Nanna’s designs into production. We began by launching the Ring Chair at the imm Cologne furniture trade show in 1989.

At that time, I was sales manager for Fredericia and therefore naturally involved in the dialogue with Nanna, and when I became chairman of The Cabinetmakers’ Autumn Exhibition in 1990, where Nanna was also on the board, we really became good friends. The year before, at the same exhibition, she had shown ‘Bench for Two’ and we talked about why it had not been put into production, because she was absolutely delighted with it. So we decided to introduce it the following year at the 1990 Cologne trade show and people flocked to our stand to see this striking and sculptural piece of furniture. And so Nanna and I decided to form a partnership.

The following year we launched the Butterfly Chair, which completely stood out from the rest, and once again Nanna attracted all the acclaim, and so it continued. Having Nanna as our main designer was a paradigm shift for Fredericia, where, in addition to producing furniture classics, we had also begun daring to take wild chances on unprecedented furniture designs.

F What made Ditzel a good designer?

T It was the multidisciplinary approach she had to design. She took all the different design competences and drew on them constantly. Art, nature, colours, textiles and textures. I don’t think a traditional furniture designer would have thought like that, and I don’t think a traditional furniture designer would have dared to make as ornamented a chair as Trinidad at that time.

In addition, Nanna was skilled at challenging the design process. She questioned everything and didn’t take no for an answer. She argued her case and I had full confidence in her eye and sense of form. Her saying “three steps forward and two steps back still means I have taken a step forward in the right direction” was very much a reflection of her practice. Nanna was the queen of design in her time, which is highly unusual.

32

Bench for Two by Nanna Ditzel, 1989

33 Left

for Two at

Right

Bench

Danmarks Nationalbank

Drawing of the Butterfly Chair construction, 1990

F What made Ditzel and Fredericia a good match?

T We were fond of each other, Nanna and I. Coming under her wing and learning from her outlook on life was life-changing for me. She had tried so many things and had an amazing enthusiasm for life. She was a true citizen of the world. We had a deep respect for each other and our professions despite the big age difference; I was in my 30s and she was in her 70s but she was a really good friend and there was so much we wanted to create together. She taught me to dare to trust the process, even if it might look impossible. This has also had an impact on the design collaborations I’ve had since then, whether it was Vico Magistretti or Jasper Morrison, there was a confidence and courage in the process.

F The Trinidad Chair became Ditzel’s biggest commercial success. What’s the story behind it?

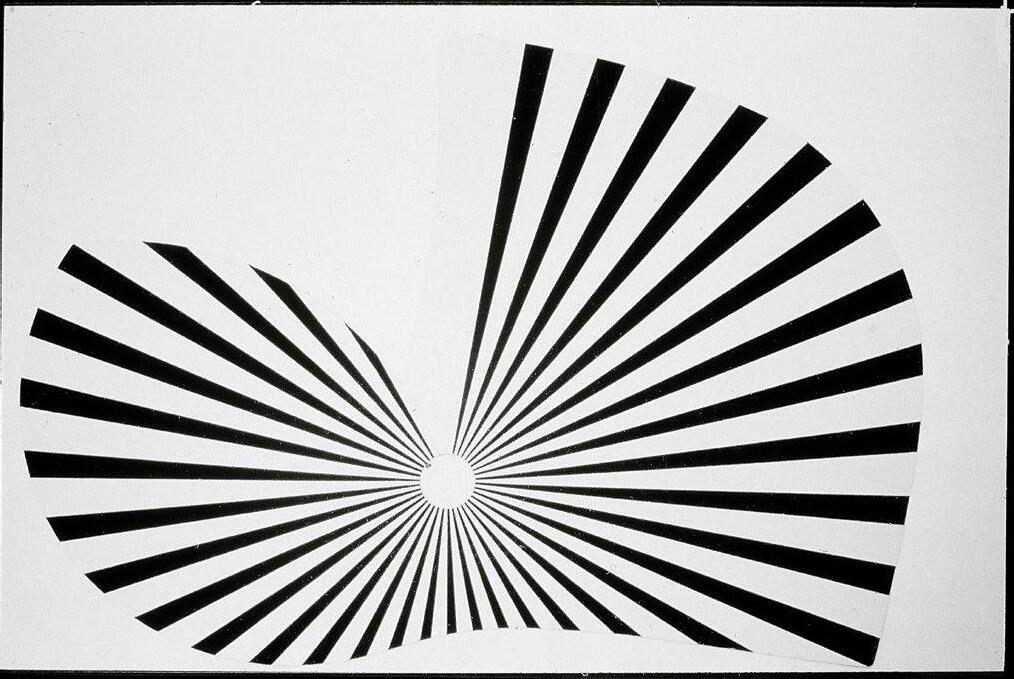

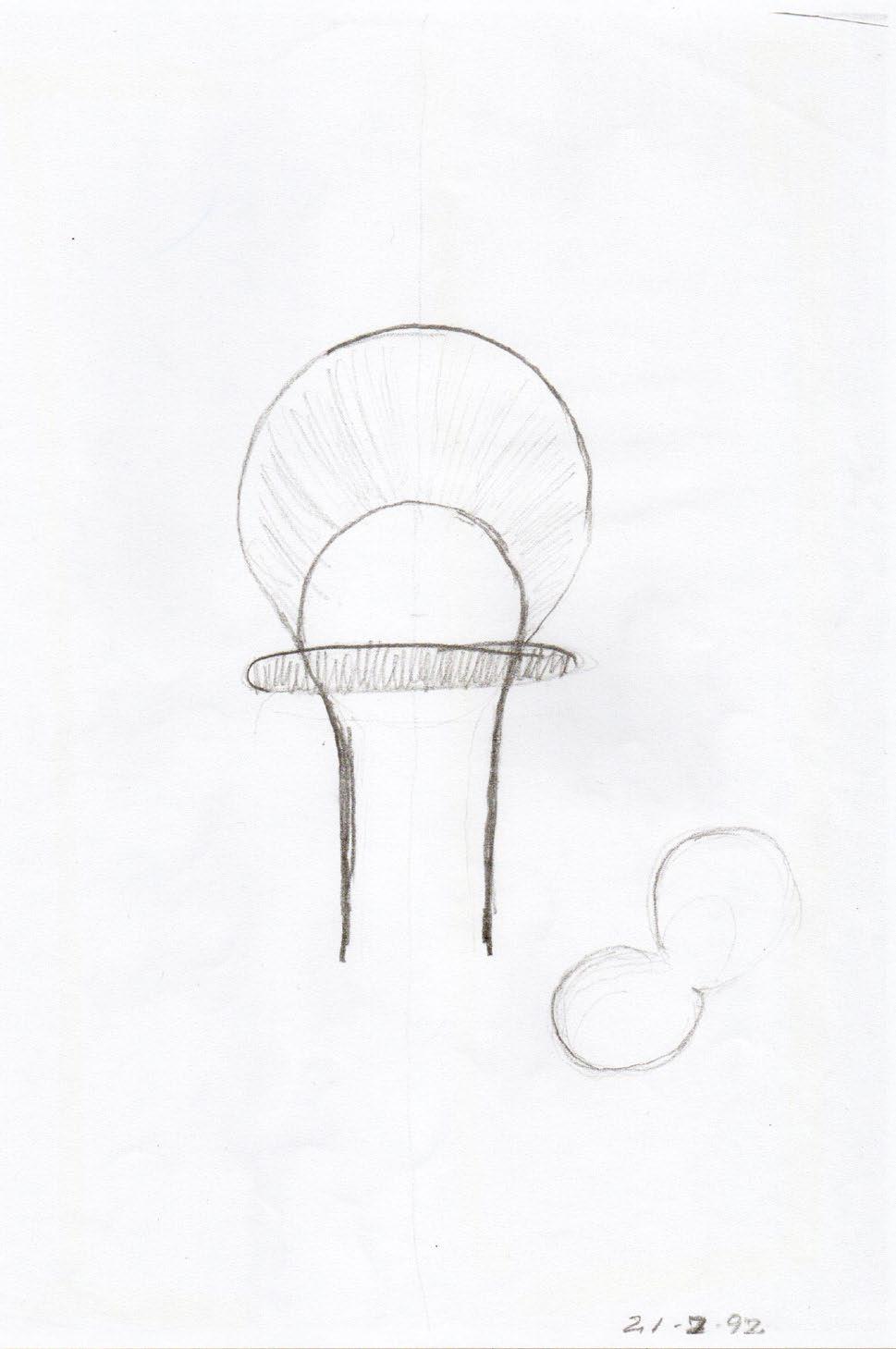

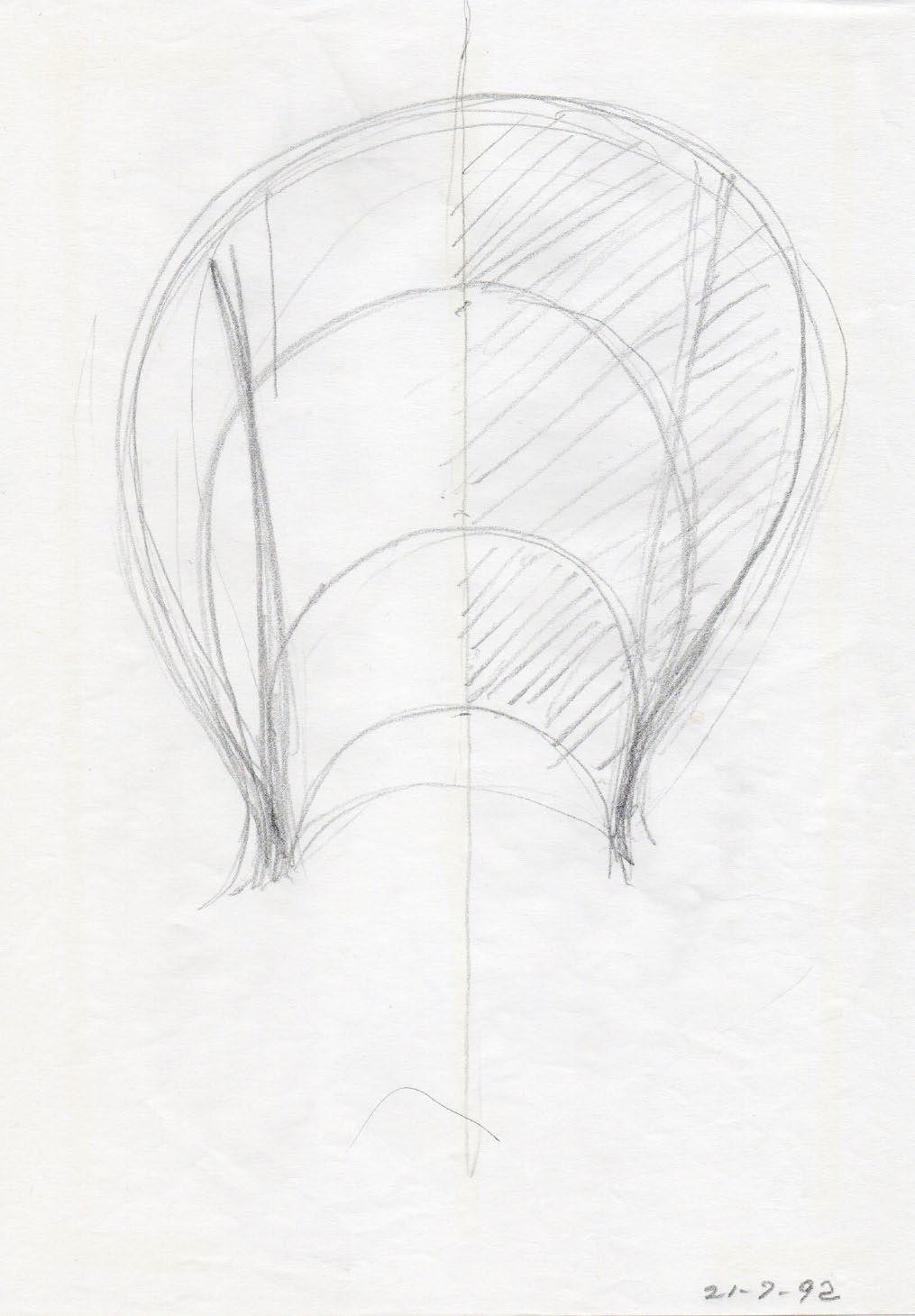

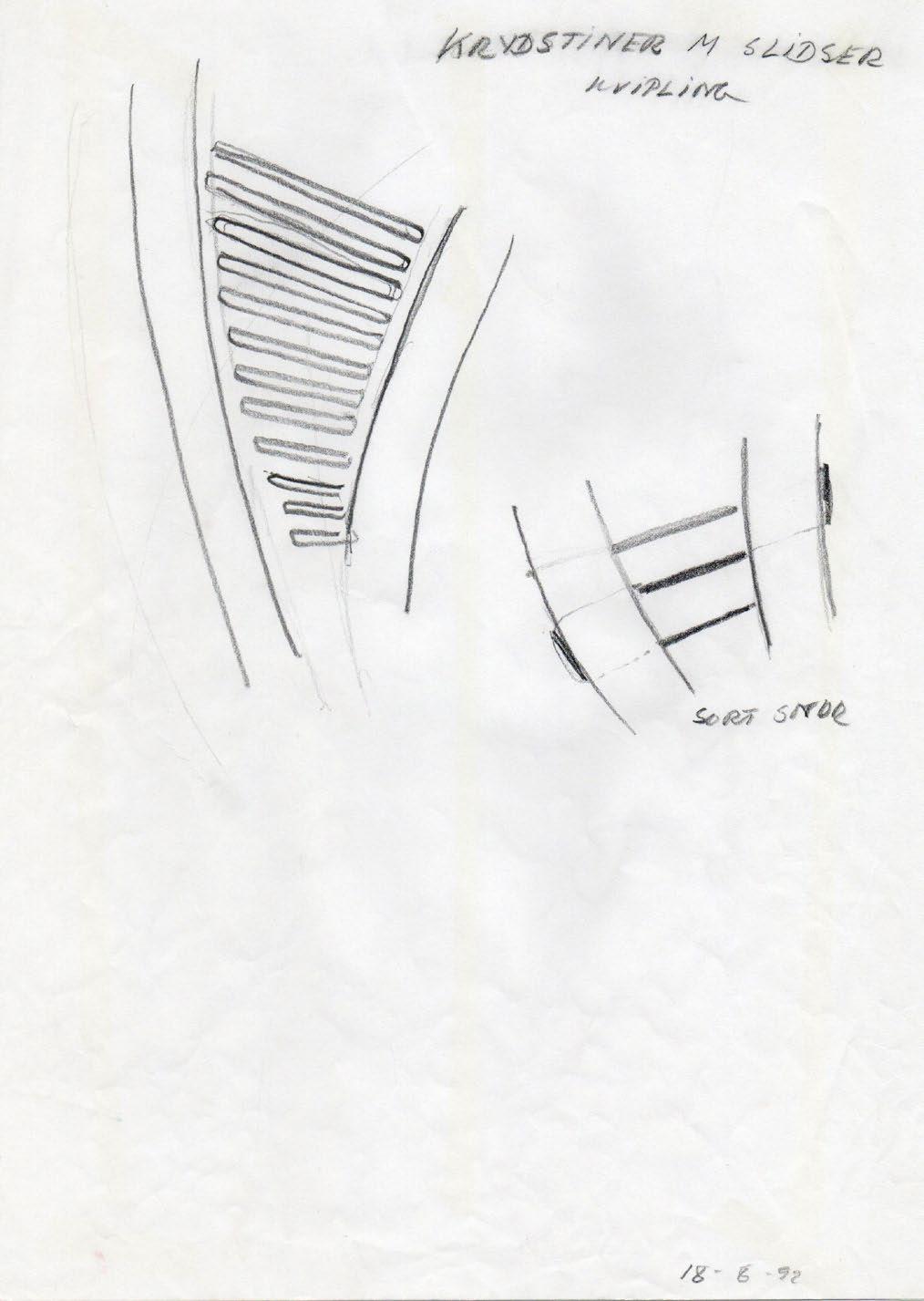

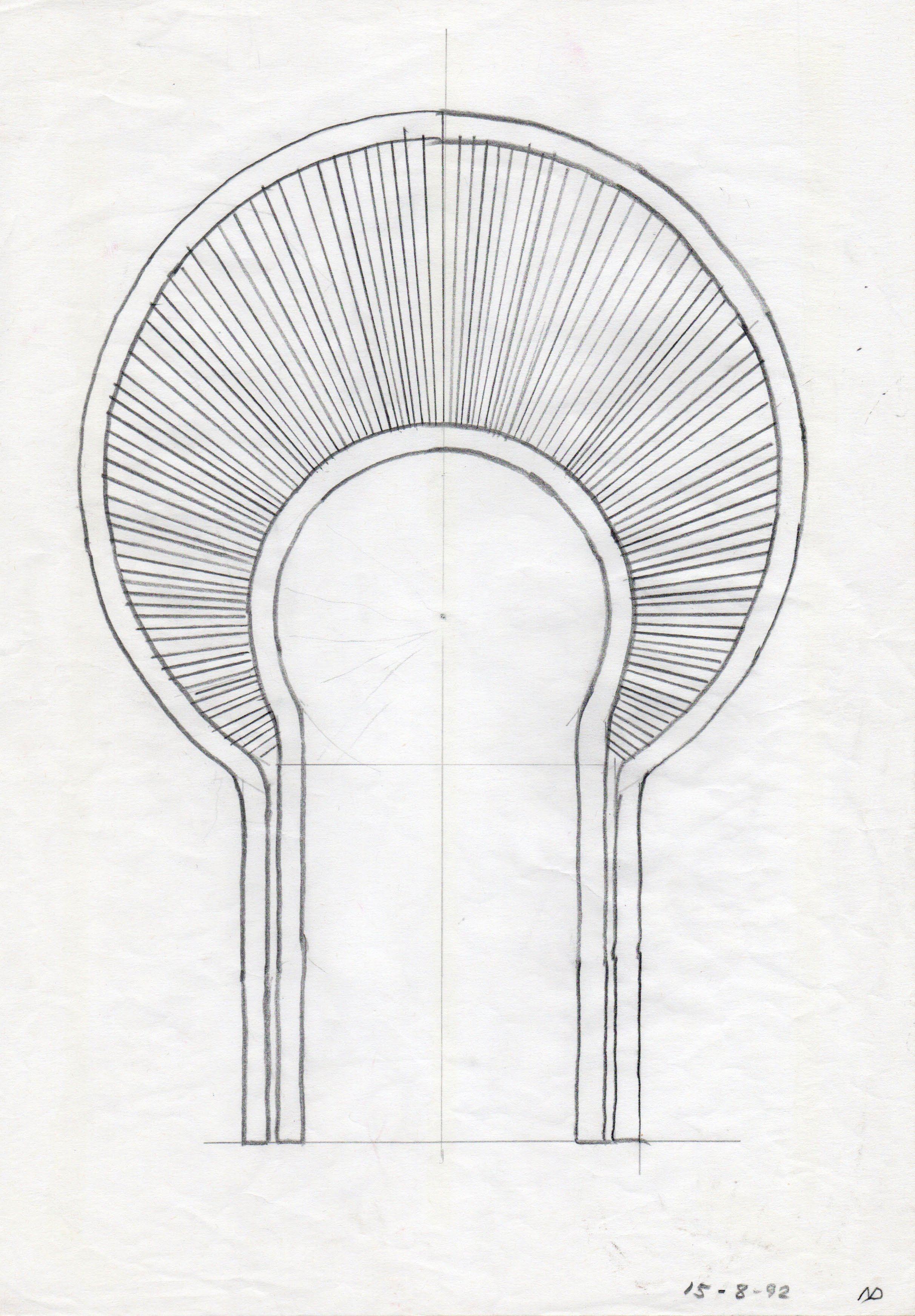

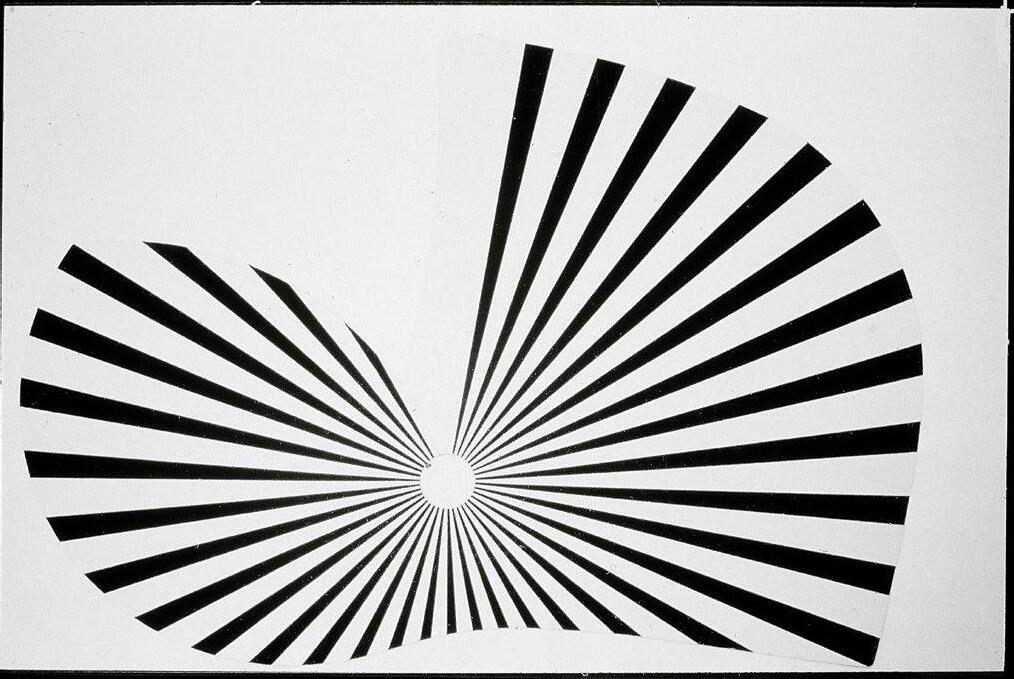

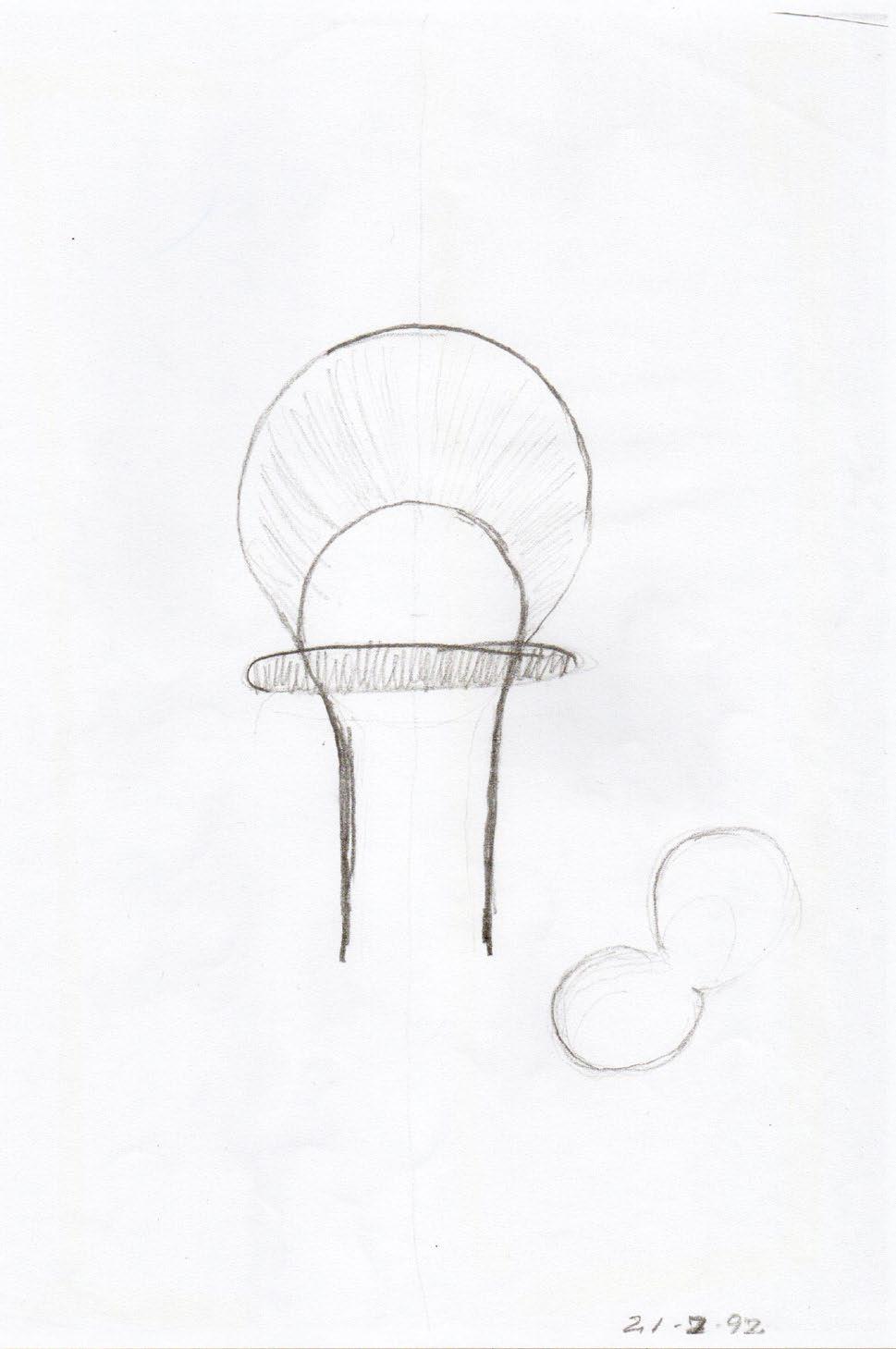

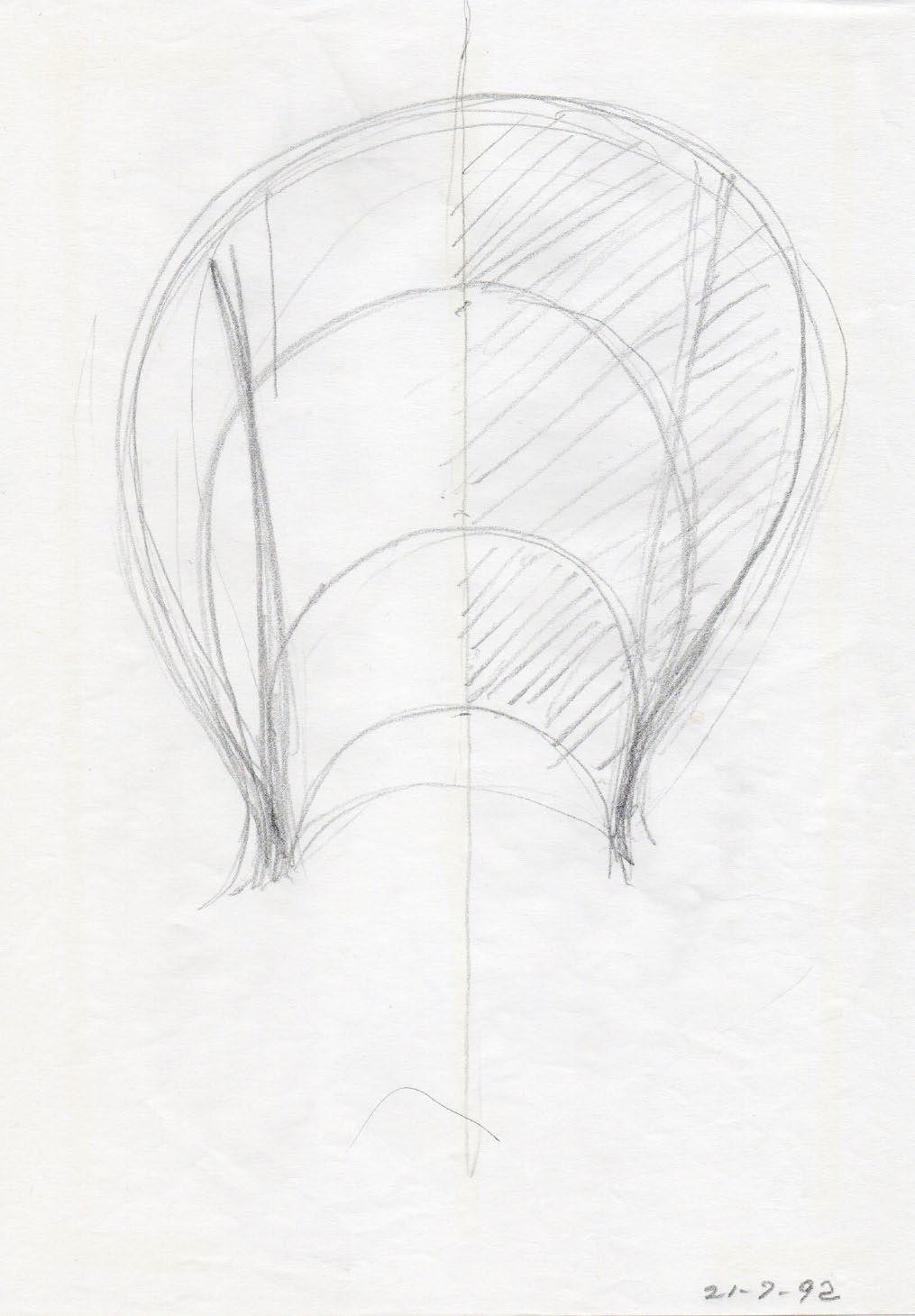

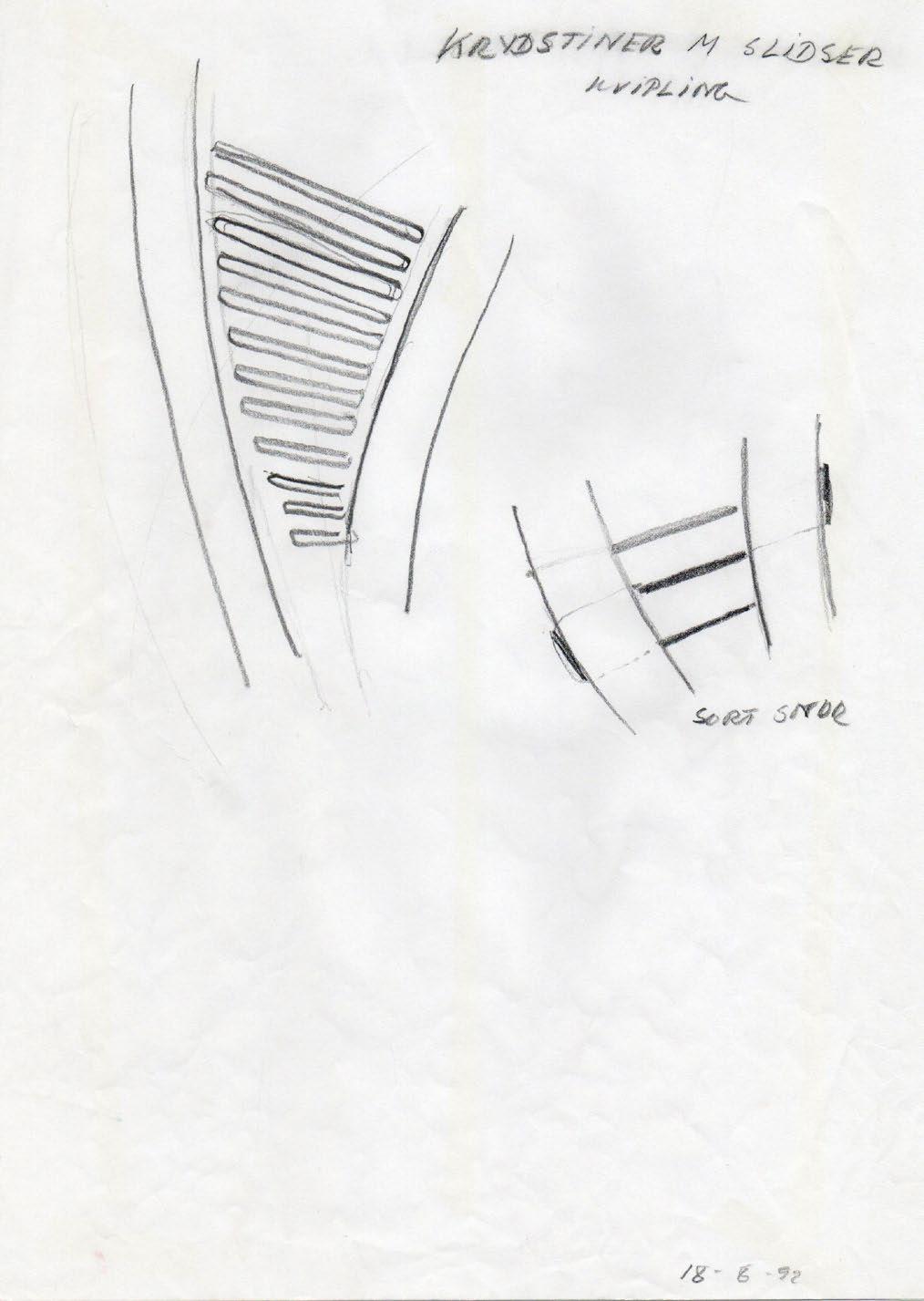

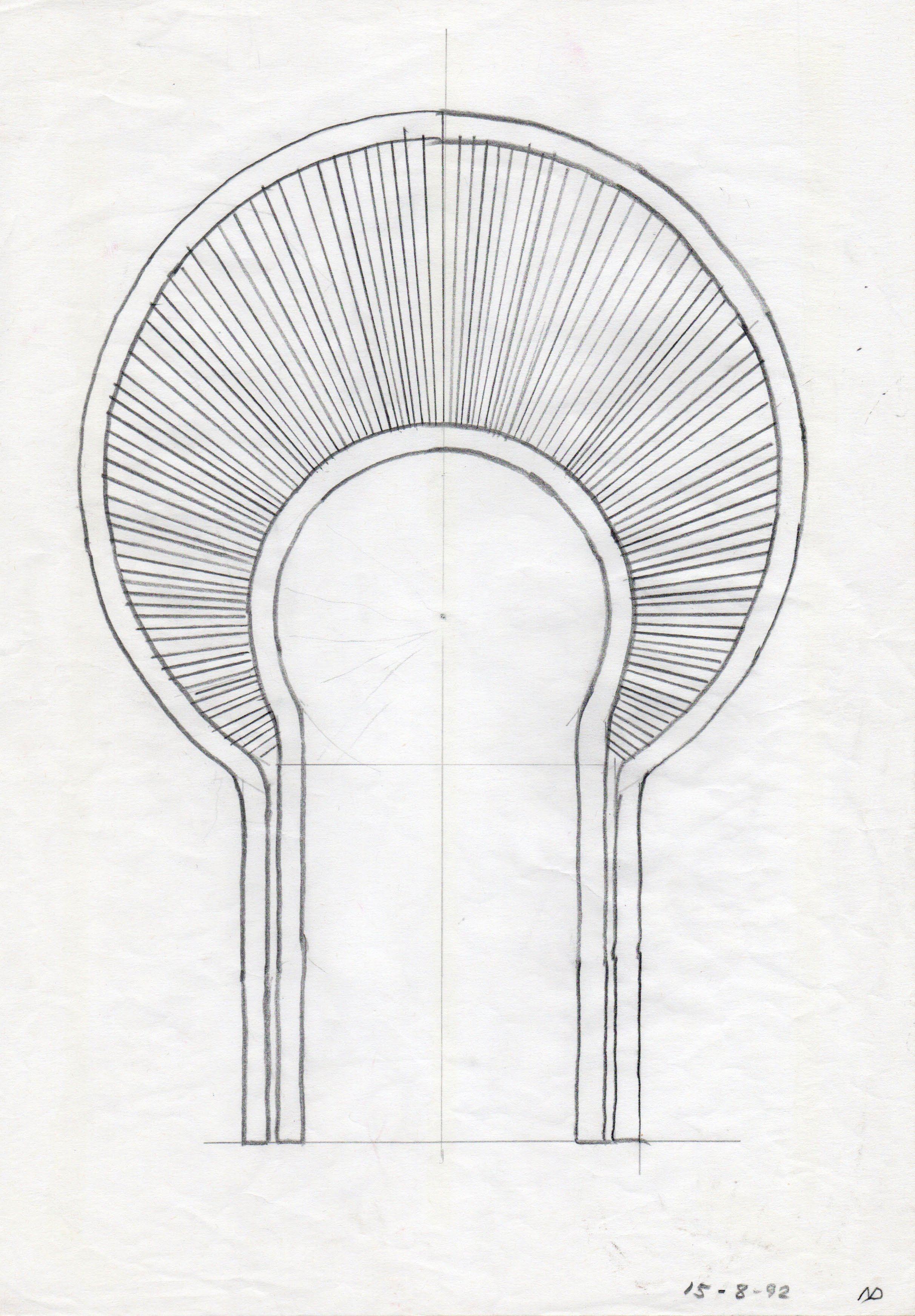

T Throughout Nanna’s process of experimenting with lines in the late 1980s and early 1990s, she recalled her travels to Trinidad and the local Gingerbread architecture, whose carved woodwork played with light and shadow. A shadow play that she wanted to transfer to furniture in a Nordic context. Nanna translated all these impressions into the Trinidad Chair. Nanna had read that Denmark’s first 4-axis CNC milling machine had been installed at a company in West Jutland and, with the new robotic technology, she could achieve the complicated milling work with the many slots in the seat and back in an efficient and commercially viable way. She was insanely geeky and interested in technology and had the courage to use technology positively in her designs.

That’s why the Trinidad Chair was already a modern industrially produced commercial chair at the time of its launch, and just two years later it received Denmark’s most prestigious design award, the ID Prize, as the first chair ever to do so. The reasoning was that the chair was an unprecedentedly elegant combination of fine organic shapes, amazing seating comfort and a thoroughly

functional chair that was at the same time purely industrial. The chair was an immediate commercial success with both private consumers worldwide, but also in the professional contract market. Even in 2023, the chair is still very much in a class by itself and is recognisable to generations of users.

F What is your own favourite object created by Nanna Ditzel?

T That would be the Trinidad chair, which is a hugely successful chair. It is technical and industrial but comfortable, poetic and well thought out. In my collaboration with Nanna and in my furniture career in general, Trinidad was clearly her and my favourite piece. It was fairly quickly deemed a classic, not in an elitist way, and it was embraced by the Danes in particular, which I am still delighted about. I also love Nanna’s many jewellery designs, which are unique in their organic design aesthetic.

34 Left Vintage Trinidad Chair

“She took all the different design competences and drew on them constantly. Art, nature, colours, textiles and textures. I don’t think a traditional furniture designer would have thought like that, and I don’t think a traditional furniture designer would have dared to make as ornamented a chair as Trinidad at that time.“

A poetic design pushing the limits

dad

Chair

“A chair is for sitting in, but it also expresses age, eroticism, essence, human feelings, and dreams. While functionality must naturally be preserved, for me, chairs have increasingly become attempts to meet the challenge thrown down by all these other elements.“

37

Left Trinidad Chair in Oregon pine

Nanna Ditzel, 1994.

Friendly, comfortable, and pushing the limits within production. Ditzel got inspired for the Trinidad Chair from her trips to the Caribbean Islands with its vivid folk culture, stunning nature and unique architecture with its ornamented gingerbread style and brightly painted fretwork. With parallels from Ditzel’s jewellery design, she adds expressive ornamentations to her chair design while including human curves, making it all about the impression of the person in the chair. It is essential to exude dignity and be gracefully positioned as if sitting in a beautiful flower, creating a poetic frame around the seated person.

Like iconic moulded plywood chairs from the 1950s, Ditzel seeks refined plywood forms on slender frames. While experimenting with materials and the

capability of wood, she pushes the limits of what is possible. With the help of Denmark’s first 4-axis CNC milling machine, her vision is made possible for the industrial production of the Trinidad Chair. Inspired by the Caribbean winds and the sunrays playing with the fretwork and the shadows cast by trees on the gingerbread houses, this plywood chair is recognisable yet totally its own.

Trinidad comes in various woods and finishes. To commemorate what would have been Ditzel’s 100th anniversary and the 30th anniversary of the Trinidad Chair itself, it is being launched in the new colours Khaki, Nordic blue and a delicate Oak oil version, all with brushed stainless steel legs.

38

Above An example of the architecture that inspired Nanna Ditzel on her trips to the Caribbean Islands Right Trinidad Chair

40

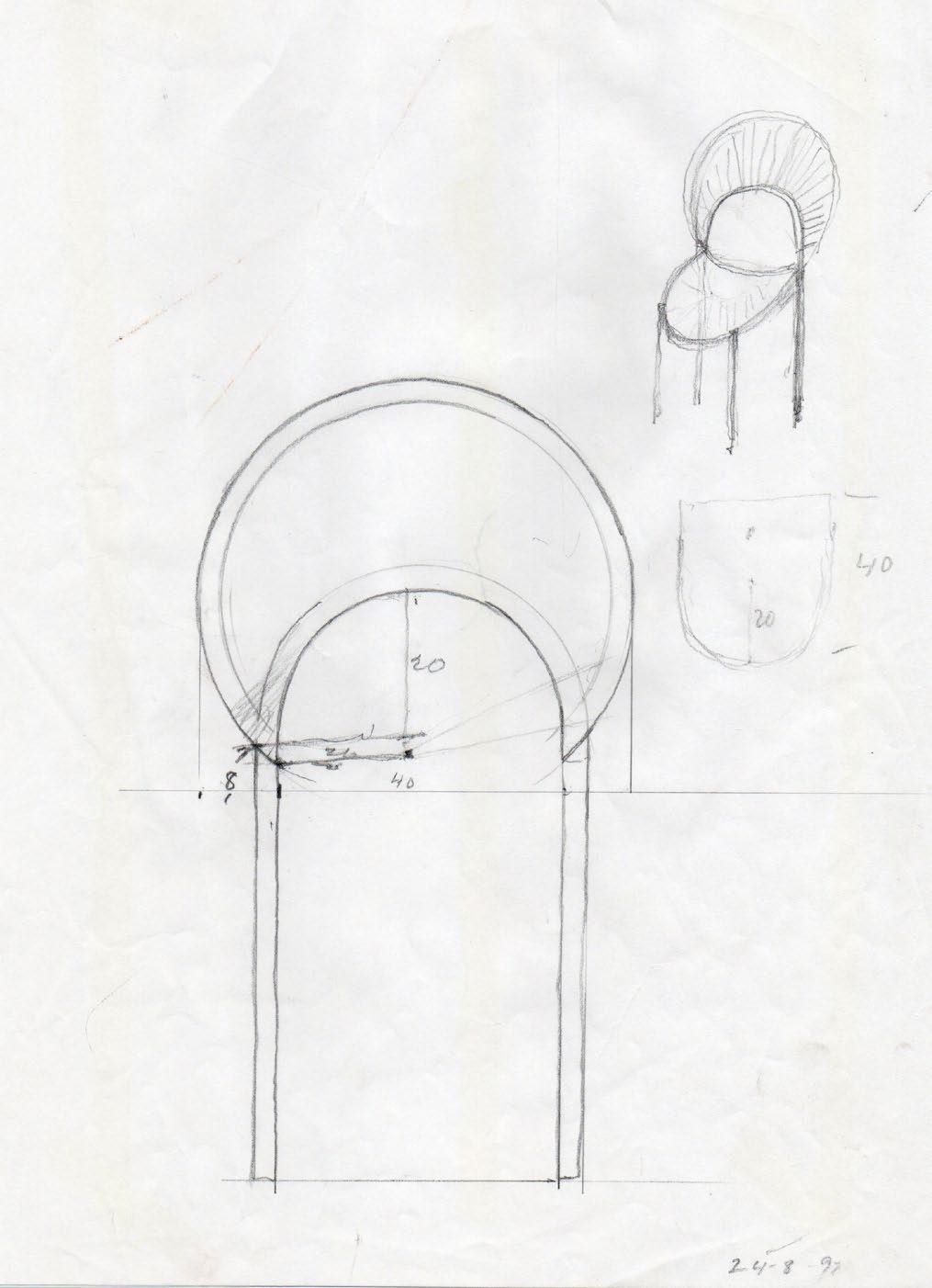

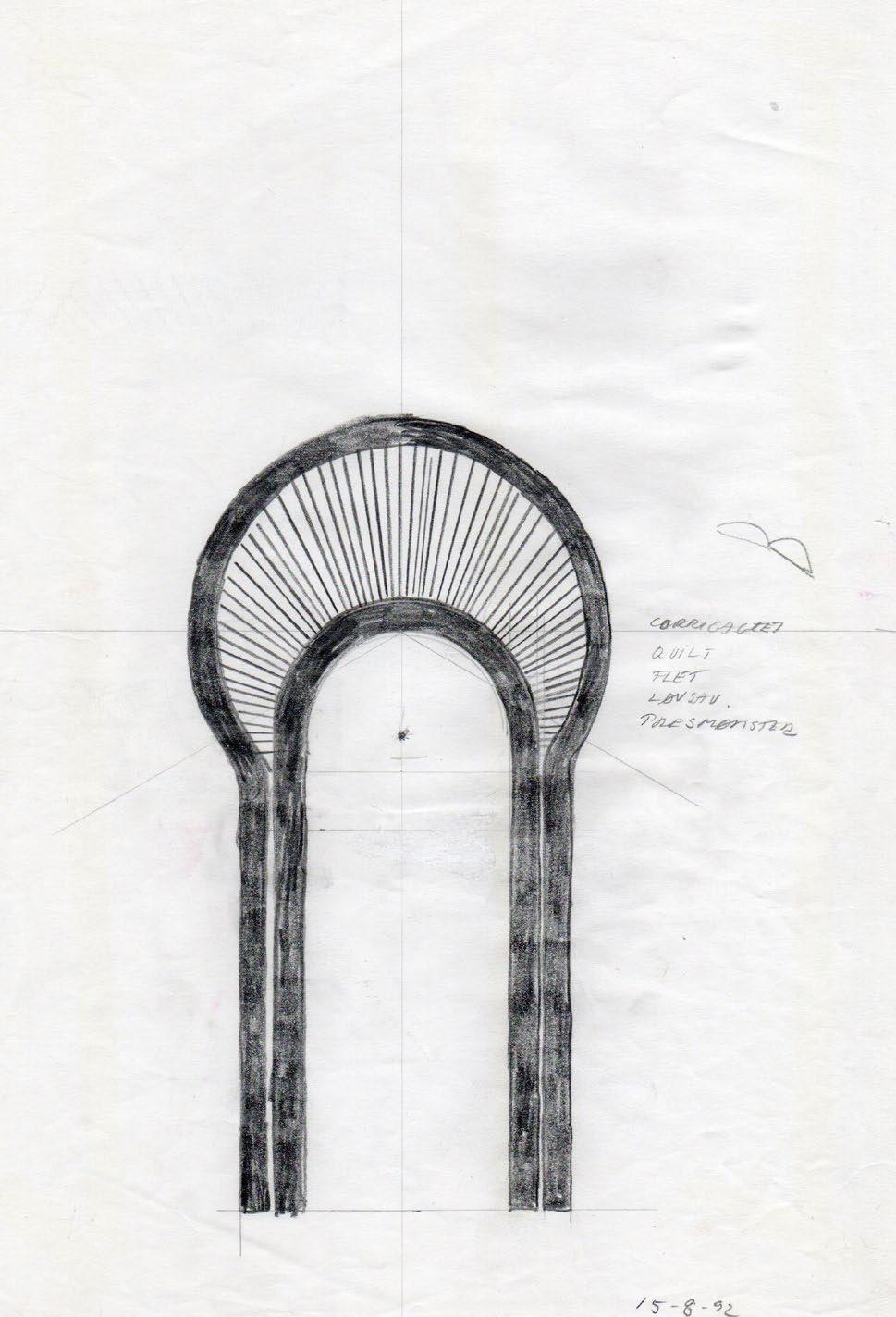

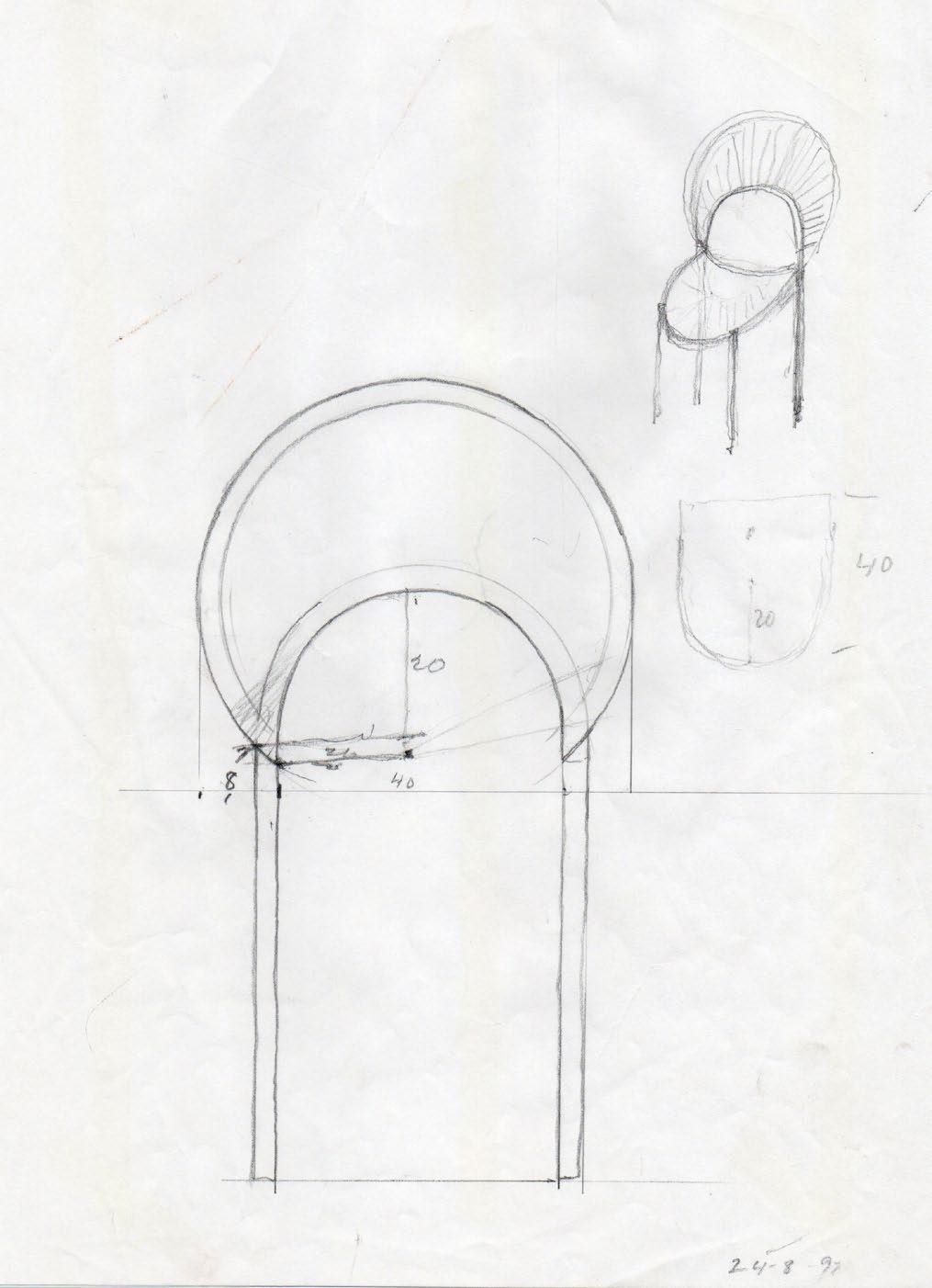

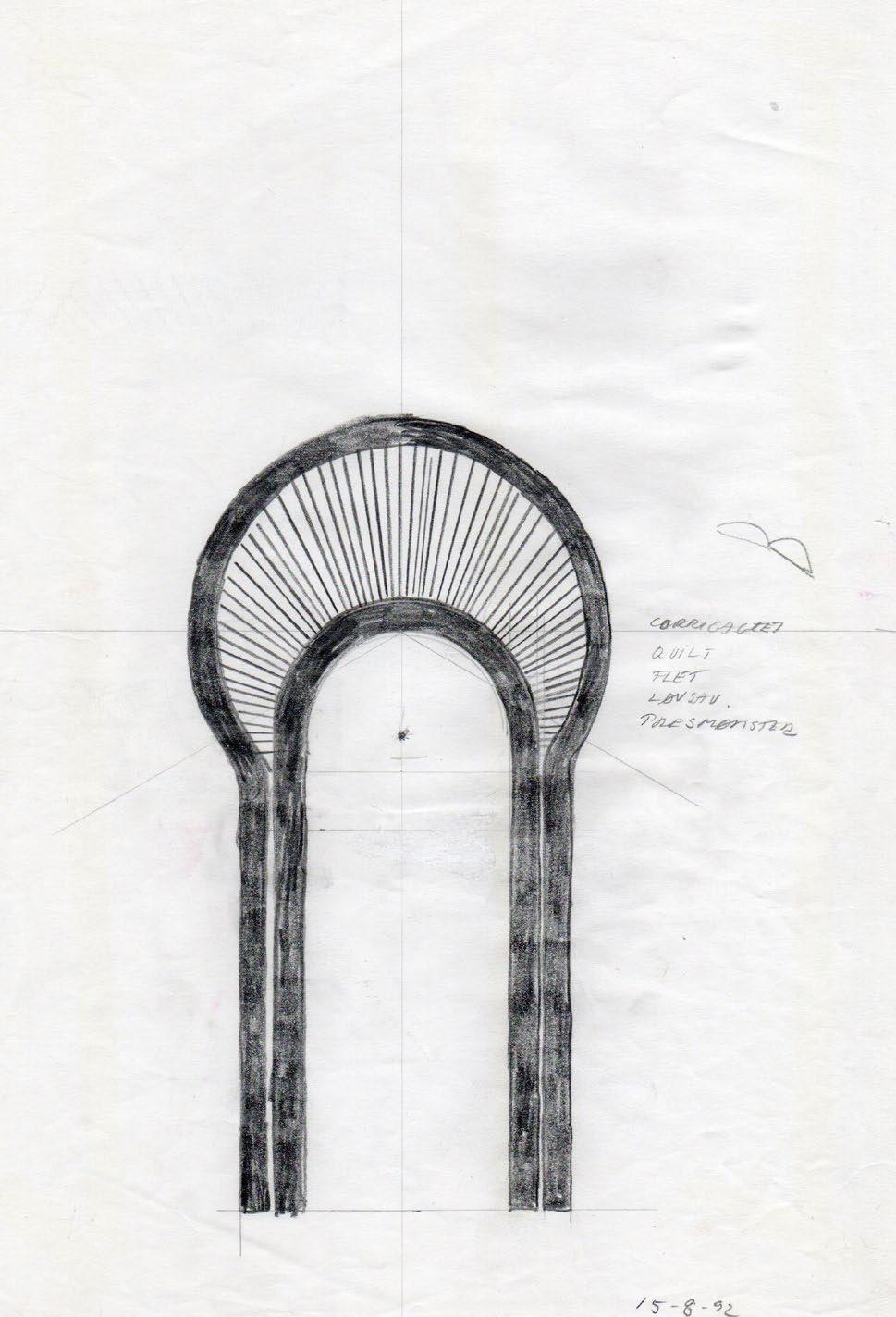

Nanna Ditzel’s sketches of the Trinidad Chair, 1992

41

42

Nanna Ditzel’s sketches of the Trinidad Chair, 1992

43

44

Trinidad chairs in Vilhelm Lauritzen’s Radio House which now houses The Royal Danish Academy of Music

45

Trinidad Chair in Oak oil in The Radio House, Copenhagen, 2023

46

Trinidad chairs in The Radio House, Copenhagen, 2023

47 The Radio House, Copenhagen, 2023

48

Twisted stacking of the Trinidad Chair on transport trolley

49 Vintage Trinidad chairs

51

Left Trinidad Chair in Khaki green, J39 Mogensen Chair by Børge Mogensen

Above Trinidad Chair in Oregon pine, Islets Dining Table by Maria Bruun Below Trinidad Chair in Nordic blue, Post Table by Cecilie Manz and Delphi Elements by Hannes Wettstein

52 Vintage Trinidad Chair

of design A family home full and

experimentation

54

A conversation with Dennie Ditzel, daughter of Nanna Ditzel and CEO of Nanna Ditzel Design Studio

As the firstborn of Nanna Ditzel’s three daughters, Dennie grew up in a creative home where both her mother and father let inspiration flow and experimentation prevail. A home with big ideas and a new way of looking at life. From 1995–2005, Nanna and Dennie worked closely together at the studio, where Dennie is still responsible for carrying on the design legacy.

57

Left Dennie Ditzel in her studio with archive photographs of Ditzel Lounge

FREDERICIA What was unique about Nanna Ditzel?

DENNIE Nanna was incredibly multi-faceted; her strength was that she did not allow herself to be limited. She was highly experimental with furniture, textiles, jewellery and crafts, using new materials and new approaches to developing things. My mother was good at reading up on things and dedicating her time to improving her skills. When she became interested in textiles as a young furniture designer, she borrowed books from the library to learn about colour theory and weaving techniques, and frequently visited weaving mills. Around the same time, she became interested in designing jewellery, so she immersed herself in that and spent many hours in goldsmiths’ workshops. She took an interest in everything – even what was not necessarily comme il faut to work with, such as jewellery, which – at a time when functionalism was in vogue – was considered unnecessary decoration without a function, which perhaps also piqued her interest – the somewhat forbidden can be a source of fascination.

Nanna was around when there weren’t many women in the field. Some may have graduated but chose to look after children and leave pursuing a career to their husbands. Fortunately, Nanna had very modern parents who allowed her to pursue her dream of becoming a furniture designer. My parents, who met while studying at the School of Arts and Crafts, quickly found a personal and professional community. Soon after graduating, they married and set up their own design studio. Being a couple with a common interest and a common goal was undoubtedly significant to Nanna as a woman in a world where a women’s place was still somewhat considered to be in the home.

F Where did the inspiration come from?

D My mother and I had many conversations about inspiration and where it came from; these conversations started when I was young, and I just started to question why her pieces looked the way they did. I realised that they didn’t look like Poul Kjærholm’s angular furniture and others that were typical of the time. Nanna’s pieces were so incredibly recognisable. She was particularly inspired by nature and architecture. The animals at the zoo. The conch shells

and other sea shells on the beach. She kind of absorbed it all and compressed it, and used what she thought was beautiful. An aesthetic analysis. She told me she would probably have become a sculptor if she hadn’t become a furniture architec and designer.

F Ditzel was known for experimenting and challenging conventions. Was this something you experienced at home?

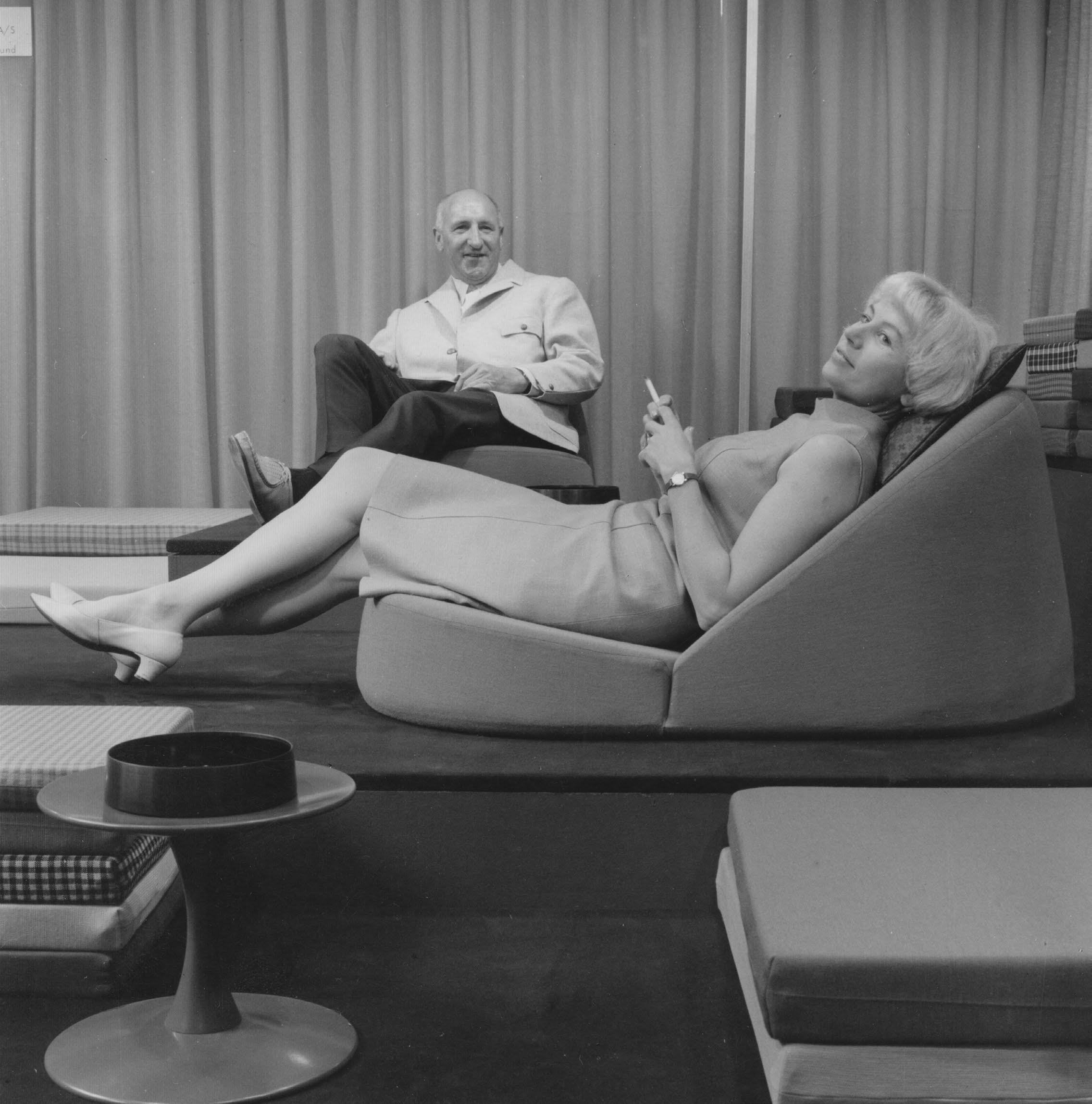

D Yes, we were subject to that. In 1966, my mother converted our living room into a stepped arrangement where you were literally forced to lie down instead of sitting up. One of my sisters loved the different style, while I questioned why it should stand out from the other homes I knew. I was probably a little boring – ‘bourgeois’ – my mother said. For me, both home and mother should look like everyone else’s, whereas my sisters thought it was cool to have a mother who was always very smartly dressed, and they liked to see their home portrayed in magazines and weeklies. That may be a bit oversimplified, but yes, we lived with the experimentation and the challenges.

F What helped secure Ditzel’s position in Danish design?

D I think it was very much the drive that Nanna had; she made things happen and was able to push them over the edge. She dared to do what she wanted to do and what she devised. She wanted to eliminate formality and dared to challenge convention.

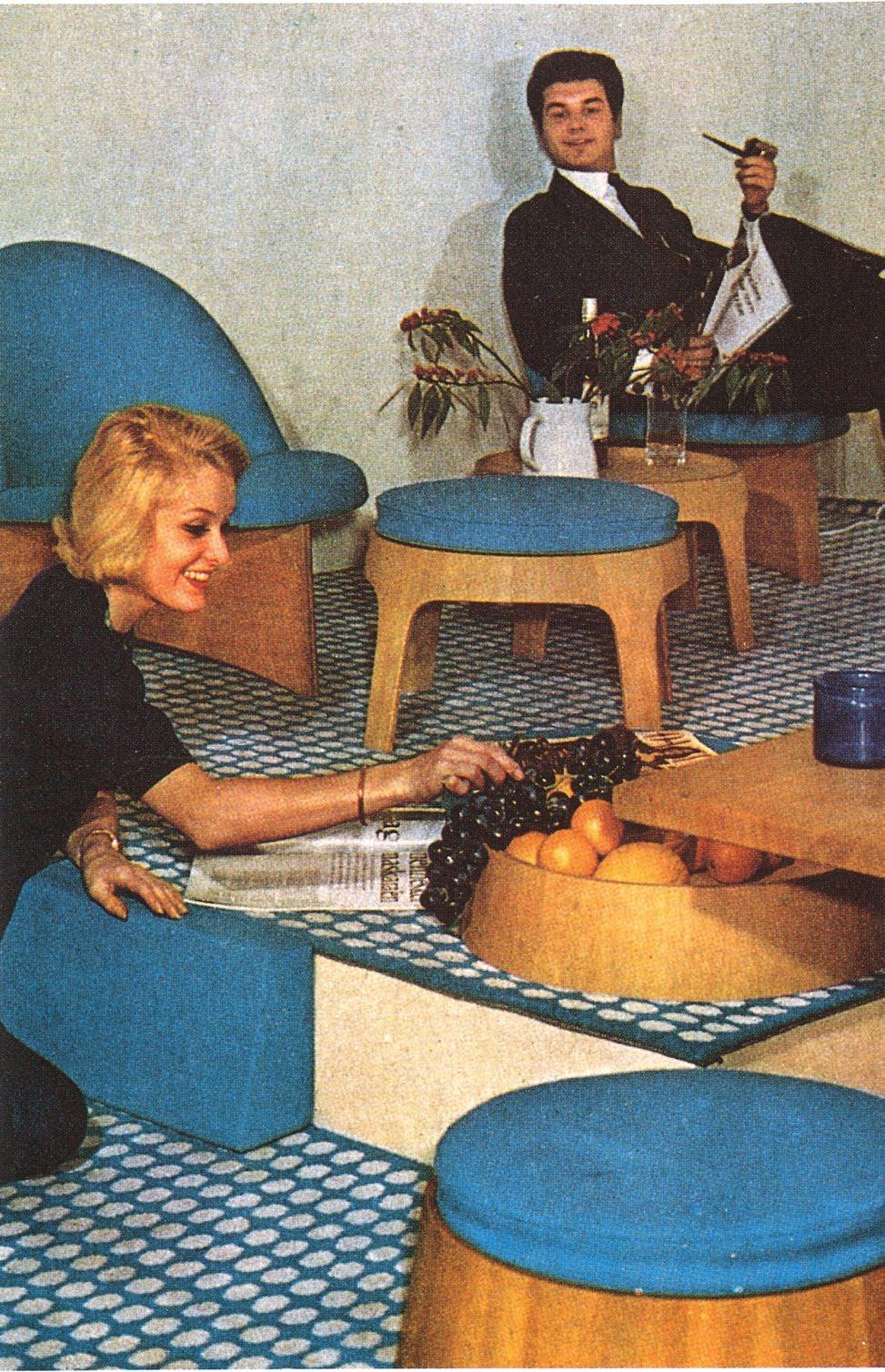

F What is your favourite object created by Nanna Ditzel?

D That would be the Trisse table. It is both incredibly versatile and recognisable, and unique. It was initially designed as children’s furniture in 1962 when Nanna was asked to design some furniture for a kindergarten. Over the years, Nanna always had them in countless variations in her home, just as I have them in my home today. Besides the Trisse table, I like the Trinidad Chair immensely, with its slotted back and constantly varying patterns. It’s a signature piece in the room and very comfortable to sit on.

58

“In 1966, my mother converted our living room into a stepped arrangement where you were literally forced to lie down instead of sitting up. One of my sisters loved the different style, while I questioned why it should stand out from the other homes I knew. I was probably a little boring – ‘bourgeois’ – my mother said.”

59 Above Nanna and Dennie Ditzel, November 1951 Below Nanna Ditzel’s living room, Bagsværd, 1967. From left to right: Esben Thyrring, Vita Ditzel, and Lulu Ditzel (reclining)

60

Jørgen and Nanna Ditzel

61 Ditzel Lounge in

694, 674,

Hallingdal

200 and in Sheepskin

Chaconia Chair

Questioning the norm of furniture

63

Left Limited edition Chaconia

in

Chair

Hallingdal 200 by Nanna Ditzel

The Chaconia Chair was designed by Nanna Ditzel in 1962 and presented at the Cabinetmaker’s Guild exhibition in Copenhagen the same year but was never put into production.

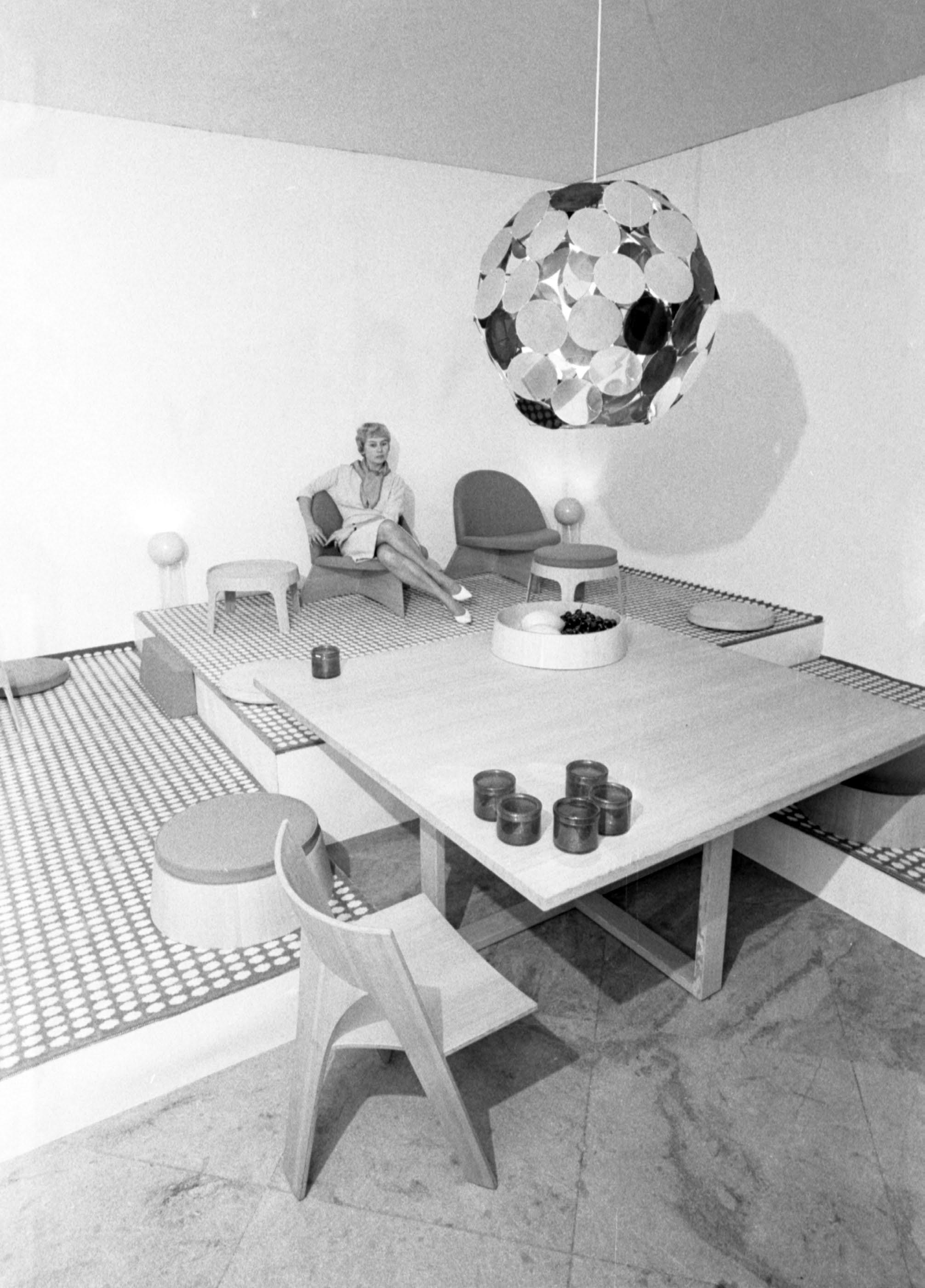

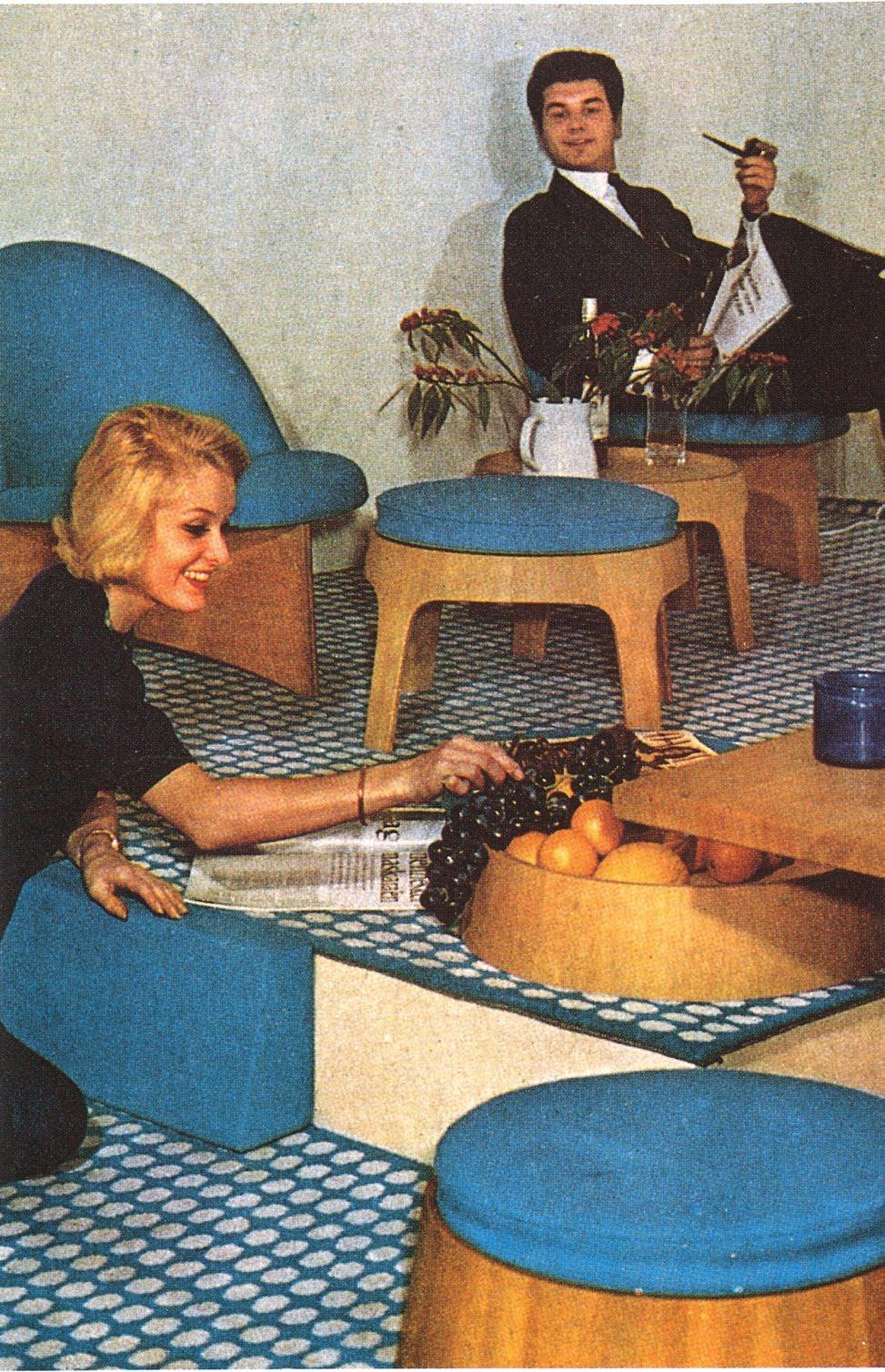

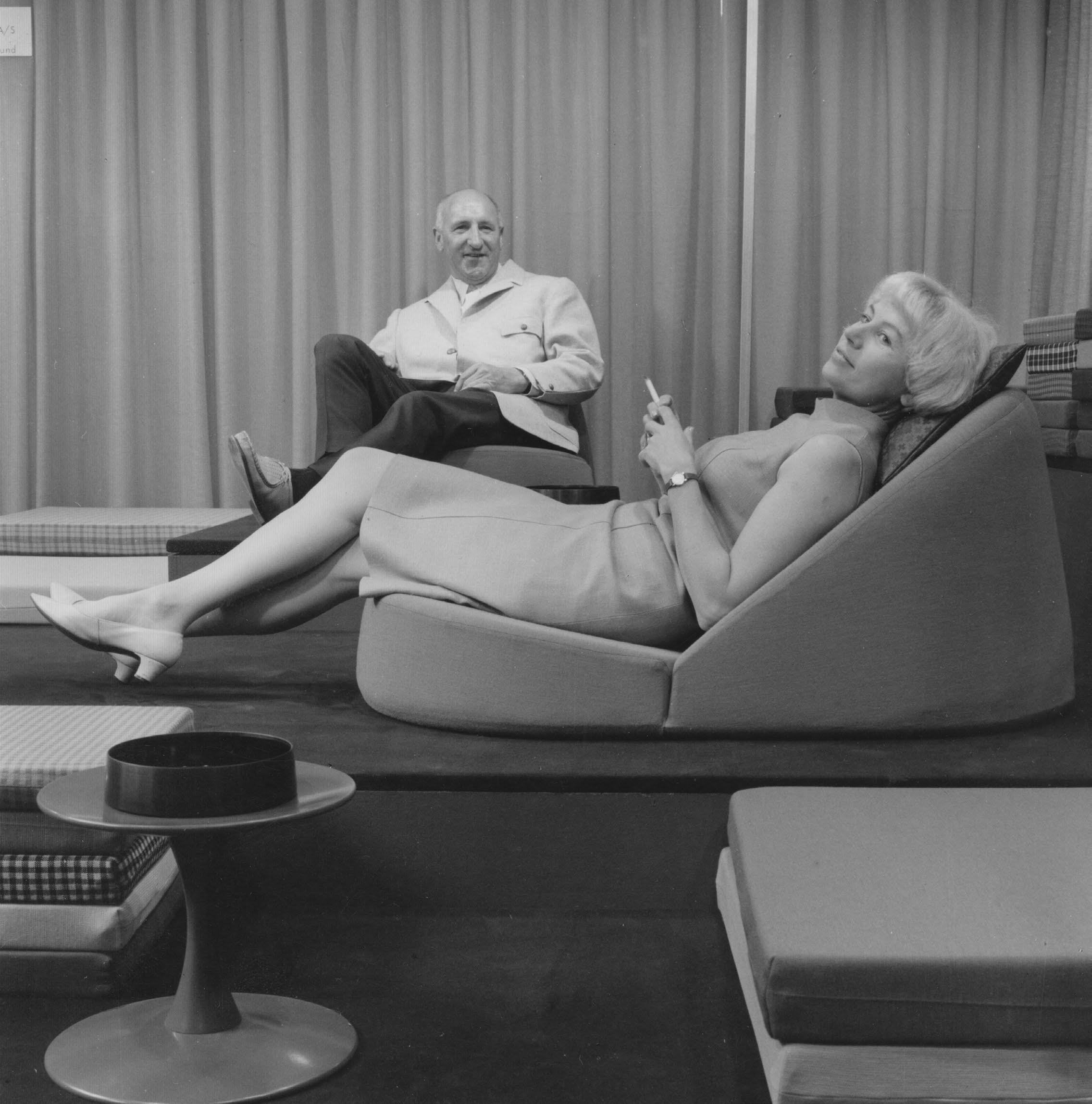

Presenting her visionary take on a casual modern living room with thoroughly composed geometrical terraced landscape in turquoise, white and warm Oregon pine. Ditzel was about questioning the norms with variable sitting heights and freeing the body and movement by making the entire room available for relaxed sitting and lounging, fusioning furniture and space.

The setting received high praise, described as bold, forward-looking and ultra-modern, including the distinct lounge chair being perceived more as a sculptural object than a conventional chair.

To commemorate Ditzel, Fredericia is producing the chair for the first time in a curated variant limited to 100 pieces. Originally named nothing more than “Lounge Chair”, Fredericia has named it Chaconia following the story of Trinidad Chair. Chaconia is Trinidad’s national flower, paying tribute to the island state where Ditzel received so much inspiration.

The Oregon pine has been finished with a lacquer specially developed to resemble Ditzel’s original works from 1962 and produced with Hallingdal in colour 200, a light mélange colour, arraying an elegant golden look. The limited edition has a brass plate engraved with the production number and Nanna Ditzel’s signature.

64 Right and above Limited edition

in

200

Chaconia Chair

Hallingdal

by Nanna Ditzel

Taking design to new heights

In September 2023, Trapholt – Museum of Modern Art and Design will open the most extensive exhibition on Nanna Ditzel ever staged. This spring, a sneak peek of the exhibition is showcased at Fredericia’s Copenhagen Showroom.

66

Introducing the Nanna Ditzel exhibition at Trapholt

67 Nanna

Ditzel at the Cabinetmakers’ Guild Exhibition in Copenhagen, 1962

68 A vintage version of the Lounge Chair from 1962

Nanna Ditzel (1923-2005) is the greatest female Danish designer of the twentieth century. For the first time ever, her world of inspirations and ideas will be fully unfolded when, in September 2023, Trapholt presents Ditzel’s complete oeuvre in a densely sensuous context of furniture design, textiles, jewellery and immersive installations. Celebrating the 100th anniversary of Nanna Ditzel’s birth, it will be the most comprehensive exhibition of her work to date. It tells the story of how you can evolve and realise your potential if you are in touch with the inspiration offered by art, culture, nature and everyday life. Nanna Ditzel combined an insistence on solid craftsmanship with artistic and cultural inspiration, and in doing so, she created unique and universal design icons. When we experience Ditzel’s design and sense the connection between craftsmanship and inspiration, we understand that the genuinely new does not arise when mindlessly repeating the known, but when you let yourself be fuelled by curiosity and inspiration, drawing on a range of diverse and surprising sources to challenge the status quo.

Nanna Ditzel works with and around the entire body – she bejewels it, covers it with textiles and showcases it in her furniture designs. In particular, she taps into our contemporary world with competencies that point to 21st Century Skills. With

creativity, interdisciplinary collaboration, reflection and media awareness, her work can exemplify and personify society’s future learning and construction. For Nanna Ditzel, inspiration is decisive in how it unfolds due to a multitude of thoughts and experiences among people or alone in nature. She observes life, people, shapes, colours, weather, and everything around her. She works neither with routine nor something that has been done, said, or occurred. And from these efforts, analyses and thoughts, something surprising and unexpected often emerges. Critical thinking ensures new, sustainable ideas to create a picture of life. A life rich in content and experiences, an innovative life.

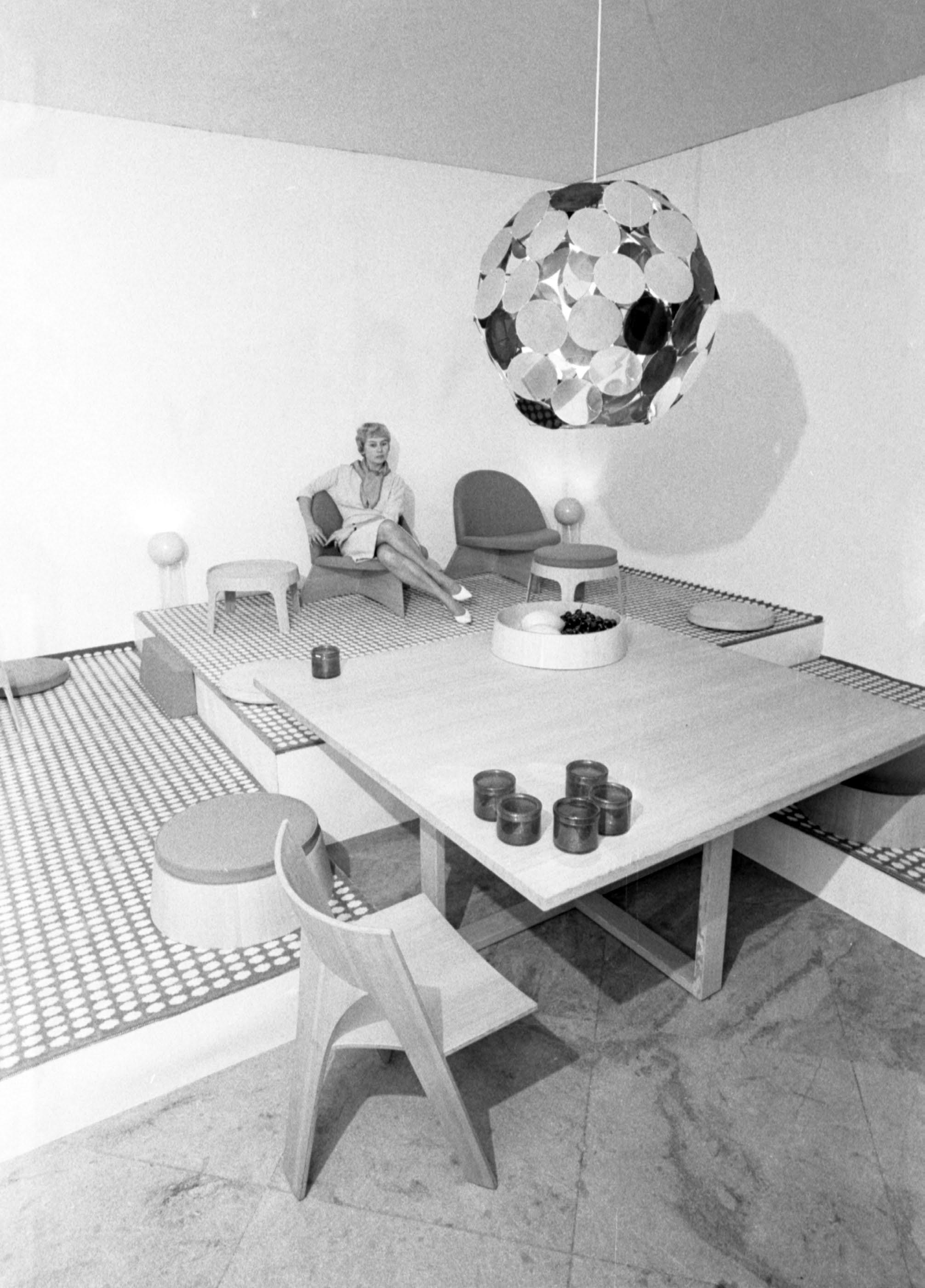

In collaboration with Fredericia, Trapholt presents a compelling sensuous staircase environment from 1962 created by Nanna Ditzel for the Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild Exhibition. The exhibition has been hailed as the best in many years, demonstrating innovation and creativity. Nanna Ditzel presented a square living room in staggered planes with carpeted flooring as a partial sitting and lounging area with a square table in the centre, cushions on the floor, new sculptural stools and chairs in moulded wood, and fellow designer Verner Panton’s spherical Topan lighting.

69

Exhibition text by Sara Staunsager, Curator of the Nanna Ditzel exhibition at Trapholt

Left The Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild, September 1962 Right The original Lounge Chair, 1962

Experience Nanna Ditzel’s staircase environments at Trapholt from 28/09/23 –11/08/24

“I’m surprised that Nanna hasn’t become more widely known globally, and I wonder if it’s because she was a woman. Nanna significantly challenged the design scene; she was not afraid of free form and had her own unique vision.”

70

A global citizen with impact and relevance

With Kvadrat, the Byriel and Rasmussen families created a global textile company with deep roots in the Scandinavian design tradition and a link to international creative talent. Nanna Ditzel was Kvadrat’s very first designer, and her colourful and distinctive textile Hallingdal brought instant success. The popular upholstery fabric has sold over 6 million metres over the years and achieved iconic status thanks to its durability and lasting relevance.

FREDERICIA In 1965, Ditzel designed Kvadrat’s very first upholstery fabric, Hallingdal, still one of Kvadrat’s best sellers. How did it come about?

ANDERS In 1965, Nanna developed several textiles with the legendary businessman Percy von Halling-Koch, whom my father Poul Erik Byriel and Erling Rasmussen, the two founders of Kvadrat, had worked for at Unika Væv. In 1968, when Kvadrat was founded, Hallingdal became first textile and product ever. In this way, Nanna and Hallingdal are closely linked to the birth of Kvadrat and who we are as a company. My father also grew up in the furniture industry in the 1950s and 60s. Like Nanna, he found the industry and its approach very formal, very cautious and very controlled. In this sense, there was a rebellion to set things free through a radical way of looking at colour, which was an immediate success. We come out of 1968 and out of Nanna’s colour vision. Kvadrat is linked to pop art and what came after Danish modernism.

F What impact has Ditzel had on Kvadrat?

A Nanna had a significant impact on Kvadrat, our identity and our core idea. Ditzel, along with the artist, architect and designer Gunnar Aagaard Andersen, were the biggest influences on my father, who was the creative director of Kvadrat from its founding in 1968 until 2000. Nanna influenced how my father saw the world and colours. Hallingdal introduced bright, vibrant colours with an edge. This was challenging in its time and made Kvadrat known. The success was followed by numerous textile designs from Nanna’s hand over the years.

Nanna was a big personality and a good support in charting a clear course in the company. She was a true citizen of the world, interested in what was happening out there and part of the global design community. As a designer, she can be seen as the link between the mid-century and contemporary design scenes.

F Why is Ditzel still relevant today?

A Because Nanna’s values and thoughts on durability are eternal, Nanna created products with the intention of making them last a lifetime or as long as possible. We have experienced this with Hallingdal when we see products that come up at vintage auctions; the foam may have collapsed, and the furniture itself is worn, but the fabric still holds up 30-40 years later. You don’t see that, in the same way today in terms of quality.

In 2021, we relaunched Nanna’s textile, Sisu, which was found in our archives by Danish-Vietnamese artist Danh Vo, who is very interested in the question “where are the women in Danish design?”. Keen to adjust history, he searched for the female weavers. One of his findings was the Sisu textile from Ditzel’s studio, which he then used in his solo exhibition ‘Take My Breath Away’ at the National Gallery of Denmark in 2018. After this, based on Nanna’s colour scales, we interpreted and further developed Sisu with Vo, bringing the material back to life.

In 2012, we also relaunched Hallingdal in 58 colours, including 22 new shades in Nanna’s original swatches. We celebrated the relaunch with the ‘Hallingdal 65’ exhibition in Milan during Salone

71

A conversation with Anders Byriel, owner and CEO, Kvadrat

del Mobile, with 32 creative talents from around the world creating new designs in the iconic textile. The relaunches of both Sisu and Hallingdal emphasise that Nanna’s textile design and colour choices hold up and continue to be interesting.

You have wondered why Ditzel is not more widely recognised as one of Denmark’s key designers. I personally think Nanna is up there with the design masters, The Big Five. It is not only Børge Mogensen, Hans J. Wegner, Arne Jacobsen, Finn Juhl and Poul Kjærholm who should be honoured. I’m surprised that Nanna hasn’t become more widely known globally, and I wonder if it’s because she was a woman. Nanna significantly challenged the design scene; she was not afraid of free form

and had her own unique vision. She makes me think of a designer like Charlotte Perriand, one of the most influential furniture designers of the early modern movement.

F What is your favourite object created by Nanna Ditzel?

A It’s the Butterfly Chair and everything that it represents. The best design is a design with an edge. It becomes sublime when it has that artistic element; this chair is a great example. We have a lot of Nanna’s furniture in our headquarters in Ebeltoft and have an actual Nanna Ditzel room where we have our art library.

72

in the

Poul Byriel and Erling Rasmussen with a client

Kvadrat Showroom, Ebeltoft, 1970

73 Kvadrat’s first showroom

designed by Nanna Ditzel, Ebeltoft, 1970

Design should raise questions and stimulate curiosity

Already recognised, Maria Bruun joins a long-standing Danish design tradition. With sincere respect for classic Danish furniture design, she builds on this foundation with an innovative approach and with an elegant design idiom resulting in works that straddle the line between artistic forms and functional designs, such as the Islets table collection for Fredericia, which reflects her sculptural minimalism. Bruun has been awarded Denmark’s prestigious Finn Juhl Prize and the Wegner Prize for her approach to design.

75

A conversation with Maria Bruun, Furniture designer

What do you find unique about Ditzel’s design?

MARIA Nanna was unafraid of ornamentation, whether it was the design idiom itself, perforations or colour composition, which I find very interesting. Her inspiration from nature was very much evident in these ornamented touches, and at a time when many others were paring back, she was not shy about adding to her designs, almost as if she couldn’t “help herself”.

F How does Ditzel’s work inspire you as a furniture designer?

M Her approach to the design process inspires me more than her actual products. For Nanna, everything was in her wheelhouse and a moldable artistic task, whether furniture, indoor spaces, textiles, everyday objects or jewellery. And her uncompromising approach to the subjective and the creative in her way of thinking is something I admire and take with me in my work.

For me, creating is a very intuitive and subjective process. Most often, I design outside the brief for this very reason. There are no restrictions or constraints; the ideas, form and materials can flow freely and transform with the project as an iterative process, where each step informs the next. For example, when I’ve collaborated with Thomas and Rasmus Graversen, I often design outside the brief and in this way, a bold product is created – a concentrate – that is me. It is brave of the manufacturer – and not very typical of our times – to listen to the designer to such an extent. It does not solely consider the existing portfolio, the behaviour of competitors in the market or high volume. Instead, it focuses on the meaningful design that embodies the designer’s vision as translated into a commercial framework. We like to think that if good design matters to us, it also matters to consumers.

F You are described, much like Ditzel, as a designer who is not held back by dos and don’ts. Can you elaborate on that?

M My creative process is intuitive, but that’s not to say that I work entirely freely because once the uncompromising artistic idea has unfolded, the ambition is often to transform the artistic thought into a functional and usable piece of furniture; this is where the work begins with the machines and skilled craftspeople to optimise and explore.

One of the best steps in the process is here, where I need to listen to the skilled and experienced craftspeople, but also sometimes push back on techniques and notions like “this is how it’s done” or “we’ve always done it this way”. This is not an end in itself, but sometimes it may be necessary to push the conventional forms and production methods – to make some mistakes – to discover new techniques or potential, thus pushing back on what’s traditional.

F Ditzel rebelled against previous ways of looking at the design, and you yourself describe a shift in Danish design right now?

M Young designers today can relate to Nanna’s approach to the process and way of creating. There is a generation now for whom there is no right or

wrong way to design. Designers are far more autonomous, and so are consumers, who recognise that design can be many things; it can be art, it can be architecture, it can be beautiful, and it can be ugly. There are many forms of expression today, and young designers are more concerned about whether it is meaningful and can elicit a response. There is much more of a tendency to stop during the process and say, “I’m done; I insist that my design makes sense to my surroundings”, whereas, in Nanna’s time, there was a more linear process when it came to what was “real design”. Today, the way we consume design is far more experimental, creating some exciting products and shifting the conventional wisdom of what design is.

F For Ditzel, it was necessary to move forward and question things constantly. What is important to you when designing?

M For me, it is essential to emphasise that good design matters and contributes more than purely functional use. Design is a profession that creates value and meaning for those who use it. I like to add something to my designs that raise a question or where those who use it might have their curiosity piqued or feel a minor irritation or annoyance. That’s where I feel I enter into a dialogue with the end user.

F What is your favourite object created by Nanna Ditzel?

M Her jewellery is gorgeous, and her Hallingdal textile has proven its worth over the years. In addition, the colour composition and her collaboration with DSB and the IC3 trains was a fantastic design accomplishment. But my favourite is the Trisse table from 1962. It is playful and sculptural with a simple design. Your hand can grip the pedestal and lift the table. It’s perfectly proportioned for the hand’s grip. It is a stackable “building block” with a completely undefinable spatial potential that can be scaled up or down. It can be one object but also 100 objects in a spatial sculpture, forming an entirely different use. For me, it is scaleless while staying incredibly one-to-one with the body, and that’s an exciting twist.

77 FREDERICIA

Ditzel Lounge with Islets Coffee Table by

Maria Bruun

78

Nanna Ditzel and Percy von Halling-Koch in setting with the Trisse as side table

79

Chaconia Chair in Hallingdal 200, Trinidad Chair in Oak lacquered with Islets Dining Table and Dependables Boxes by Maria Bruun and Hydro Vase by Sofie Østerby

80

PICTURE CREDITS

Every reasonable attemp has been made to identify owners of copyright. This has not been possible in all cases. We apologise for any omissions.

Unless otherwise indicated, all work are by Nanna Ditzel and are from the archives of Nanna Ditzel Design.

Nanna Ditzel Design

P. Front page, 04, 06, 07, 08, 14, 16, 17, 19, 27, 29, 33, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 59, 69.

Arne Magnussen

P. 02.

Schnakenburg & Brahl Fotografi

P. 09, 32.

Nathalie Krag

P. 10, 11, 12, 13.

Georg Jensen

P. 18.

Schnakenburg

P. 21, 22, 23, 25, 28, 69, 78.

Jens Frederiksen

P. 24.

Brahl Fotografi

P. 22, 23, 26.

Peter William Vinther

P. 31, 35, 39, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 53, 61, 62, 64, 65, 68, 74, 79.

Mads Flummer

P. 36.

POK Reklamefoto

P. 48.

Joachim Wichmann

P. 50, 51, 76.

Nana Hagel

P. 55, 56.

Lennart Edling

P. 60.

Jan Dahlander/Bilder i Syd

P. 67.

Jan Søndergaard

P. 70.

Commercial Photo – International Reklamefotografi

P. 72, 73.

Halling-Koch Design Center

P. 82.

TEXT

Fredericia / Theresa Bødkergaard

Henrik Sten Møller

Nanna Ditzel

GRAPHIC DESIGN

Fredericia / Amalie Hasgard

PRINT RUN 2000

Printed in Denmark 2023

CONTACT

Headquarter

Fredericia Furniture A/S

Treldevej 183 7000 Fredericia

Denmark +45 7592 3344

info@fredericia.com

@fredericiafurniture

fredericia.com

SHOWROOMS

Copenhagen

Løvstræde 1, 4th & 5th floor 1152 Copenhagen

London 1 Dufferin Street London EC1Y 8NA

Oslo

Drammensveien 120 N-0277 Oslo

81

Nanna Ditzel 100 years

“I never look back – only forward” Nanna Ditzel, 1923–2005

82

83

84

Nanna Ditzel in Trinidad Chair

Nanna Ditzel in Trinidad Chair