The

Article by Richard H. Baker

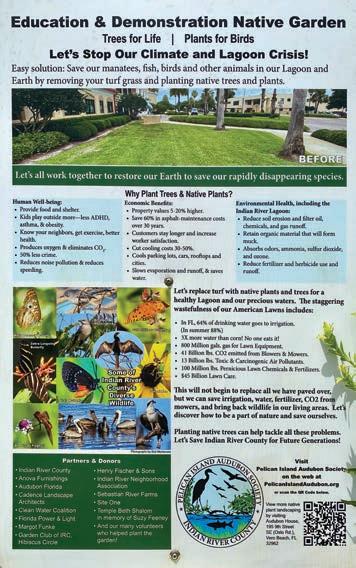

As part of the Pelican Island Audubon Society (PIAS) Trees for Life/Plants for Birds project, volunteers recently planted two new Education and Demonstration Native Gardens in Vero Beach. Located at the Indian River County administration and United Against Poverty buildings, these gardens bring native plants to places people routinely visit.

The PIAS Trees for Life project is an ongoing effort to plant 100,000 native trees and plants in Indian River County over the next decade. Twentytwo organizations have joined this community partnership, whose goal is to restore native tree cover and convert local landscapes from turfgrass lawns to native vegetation. Since trees absorb carbon dioxide, produce oxygen, cool the air, and along with native plants help clean surface waters, the program improves the environment for everyone.

The first native garden was planted in March 2022 at Indian River County Administration Building A. Many people come to the county complex to attend

meetings, pay taxes, or visit the health department and extension offices, so the location provides a perfect opportunity for visitors to learn how they can help solve the crises facing Florida’s climate and waterways. They discover that in addition to being beautiful, native plants are beneficial – they provide food for birds and wildlife and help maintain clean water for fish and manatees in the nearby Indian River Lagoon.

The impetus for installing the native garden came from County Commissioner Laura Moss, who became interested in native plants after attending Pelican Island Audubon Society’s annual event titled Transforming Landscapes for a Sustainable Future. Moss had previously led an effort to reduce turfgrass and maintenance costs at Vero Beach City Hall, and she says, “Good government sets an example. I understand the

https://instagram.com/floridanativeplantsociety/ https://linkedin.com/company/8016136

https://twitter.com/fl_native_plant

Article by Richard H. Baker

Article by Lydia Cuni, Sabine Wintergerst, Samantha Walsdorf, and Jennifer Possley

Article by Leslie Nixon

Article by Lydia Cuni, Sabine Wintergerst, Samantha Walsdorf, and Jennifer Possley

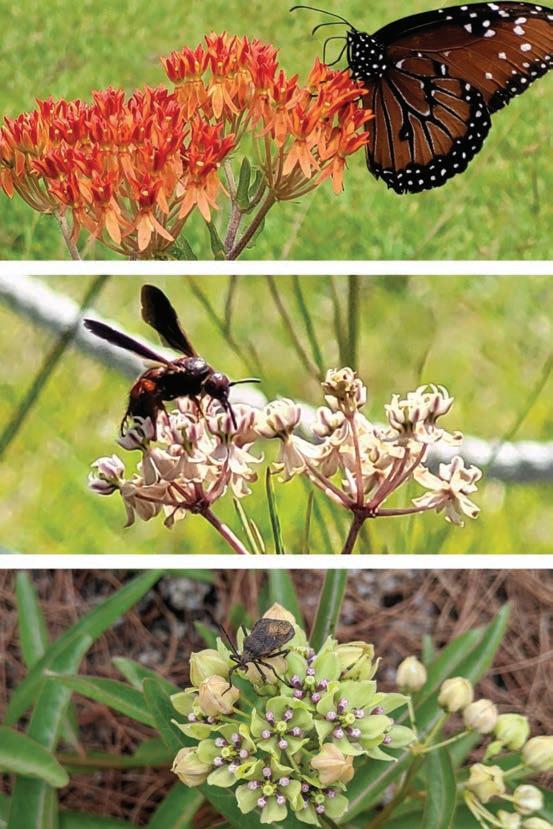

Milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) are well known for their role as larval host plants for the monarch butterfly. They can also be an abundant floral nectar source for bees and other butterfly species. For these reasons they are highly desired by gardeners and restoration practitioners, yet native South Florida milkweed ecotypes are rarely found in local nurseries while the non-native, invasive tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) is widely available and easy to cultivate. Native milkweed species are generally widespread throughout the Southeastern United States and although nearly two dozen Asclepias species can be found in Florida (Atlas of Florida Plants, 2023), eight species are considered locally rare in South Florida and Miami-Dade County (Gann et al., 2023).

At least one species, largeflower milkweed Asclepias connivens is presumed extirpated from Miami-Dade County, while another two have not been reported in some decades: swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and savannah milkweed (Asclepias pedicellata) (Atlas of Florida Plants, Gann et al., 2023). Native milkweed species in the Miami area are found in pine rockland, marl prairie, and ecotonal habitats centered around the Miami Limestone Rock Ridge. Rapid development of the area which began in the late 1800s resulted in a significant decrease in the amount of natural habitat in Miami. Today there is less than 2% left of the former ~180,000-acre extent of pine rockland, and remaining areas are heavily fragmented and fire-suppressed. The pine rockland habitat is recognized as globally critically imperiled, ranked G1/S1 by the Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI), and many of the endemic plant and animal species are equally imperiled. Most of the pine rockland left in Miami is owned and managed by the County’s Environmentally Endangered Lands program.

The popularity of native milkweeds combined with their low availability inspired Fairchild’s Conservation Team to work towards increasing the availability of four rare South Florida native Asclepias species: 1. few-flowered milkweed (Asclepias lanceolata), 2. butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa), 3. whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata), and 4. green antelopehorn (Asclepias viridis). With the overall goals of preserving these

locally rare South Florida milkweed ecotypes and making them available to butterfly gardening enthusiasts and habitat restoration projects, our objectives were to: 1. conservatively collect seeds from local populations of the four species, 2. study the long-term cold storage capability of their seeds, 3. establish ex-situ living collections for seed bulking, and 4. optimize germination and horticultural protocols. In early 2020 at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, with the local Dade Chapter’s approval of our proposal, the Florida Native Plant Society’s Conservation Committee agreed to fund our work with these four species.

Undeterred by the global pandemic lockdown, we quickly began determining where these four Asclepias species could be found locally by data mining our own records and visiting the Fairchild herbarium to identify historical location data. From June 2020 to January 2023, we visited eight Miami-Dade County Environmentally Endangered Lands preserves. Over multiple visits we surveyed for the four species, mapped new plant occurrences, and collected no more than 10% of the population’s seed output per Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) guidelines. Seeds were usually collected using a drawstring organza bag to cover a ripening pod (technically termed a “follicle”), but on some occasions we came upon a burst pod and set about collecting airborne seeds! The milkweed species

in our project are not state or federally listed; therefore, we just needed permission from the landowner, Miami-Dade County, to collect seeds. Fairchild’s Conservation Team has had a strong working relationship for over 20 years with the county. Seed collecting sites included Nixon Smiley Pineland Preserve, Larry and Penny Thompson Memorial Park, Pine Shore Pineland Preserve, Trinity Pineland, A.D. Doug Barnes Park, and The Deering Estate.

It is worth noting that fires (prescribed or otherwise) occurred at multiple preserves during the beginning stages of this project and produced positive results for all of the Asclepias species. At multiple sites there were many Asclepias that were resprouting and flowering, post-fire. We also rediscovered some populations that had not been seen in decades, like Asclepias viridis at Trinity Pineland Preserve. This all resulted in a more accurate population count for the Asclepias species. To date we have collected just over 1,300 seeds from three species (Table 1). Unfortunately, we were not able to locate or secure seeds of Asclepias lanceolata.

Once the seeds were collected, we were able focus on optimizing the seed germination rates of these plants. We tested the effects of two pre-treatment methods: desiccation and soaking seeds in smoke solution, since we have observed that seeds of many pine rockland species germinate well after experiencing the effects of fire. Our smoke solution was produced by burning pine straw in a bee smoker and guiding the smoke through water, trapping the water-soluble chemicals of smoke (Coons et al. 2014). Smoke solutions are an easy and effective way of simulating the effect of fire in a controlled environment. For all our germination tests, it should be noted that the number of seeds used was small, since seed availability was low at the beginning of this project.

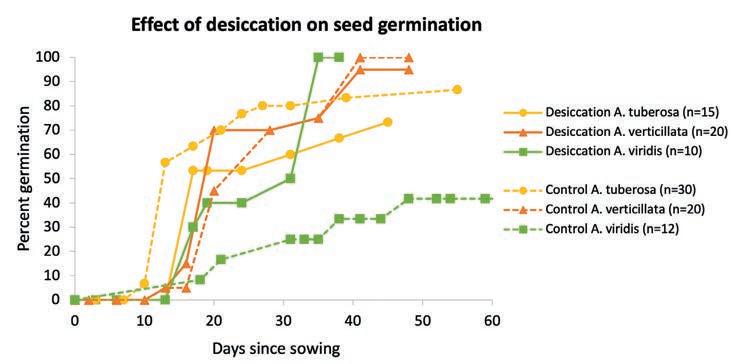

Desiccation of seeds to 11% relative humidity using the desiccation salt lithium chloride strongly affected germination in one species, increasing the germination of Asclepias viridis seeds from 42% to

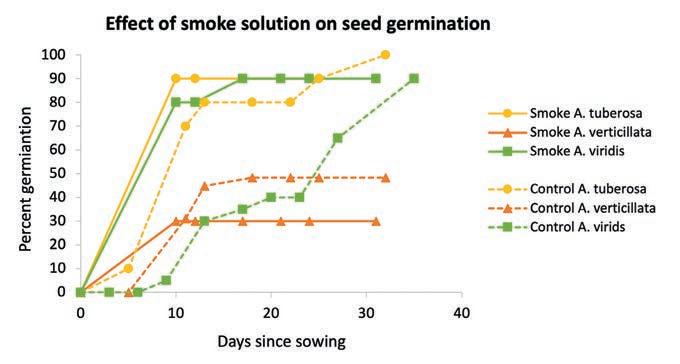

82% (Figure 2). The germination rates of the other two species were not as strongly influenced by desiccation and were above 70% without this pre-treatment. However, soaking seeds in a smoke solution for 24 hours had an effect on the germination rate of two species, A. viridis and A. tuberosa, with the time to reach 80%

germination in A. viridis smoke-treated seeds being markedly shorter (10 days vs. 30 days, Figure 3). We observed that germination rates varied between seed batches depending on the quality of seeds, collection location, and date.

An additional objective of this study was to test the long-term cold storage

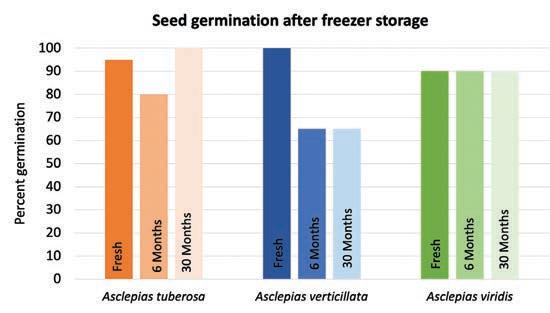

viability of the Asclepias seeds. Since these species are all locally rare, it is important to know whether their seeds can be frozen and stored in seed banks as a backup for wild populations and for future propagation. We knew that at least Asclepias tuberosa and Asclepias verticillata seeds can survive being frozen for short periods of time (SER, INSR, RBGK, Seed Information Database (SID), 2023), however we did not know how long they could remain viable in a freezer. We desiccated seeds from all three milkweed species to 33% relative humidity at room temperature, sealed them in mylar bags and froze them at -18°C. We then periodically tested the viability of a subset of 20 frozen seeds (Figure 4). We found that A. tuberosa and A. viridis remained viable, with a high germination percentage, for at least 30 months in freezer storage. Although most of the A. verticillata seeds remained viable for at least 30 months, their germination rate decreased from 100% to 65% after 6 months in the freezer. We plan to retest seeds from all three species every 1-2 years to assess how long the seeds can remain viable in the freezer seed bank.

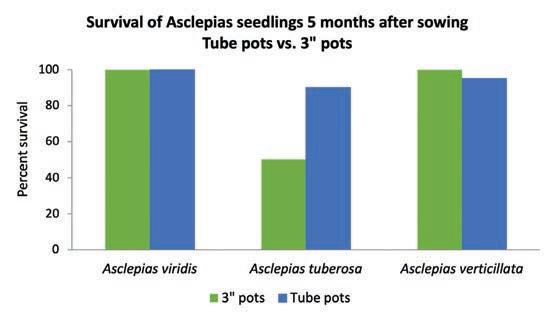

Once we successfully germinated seeds, we began sowing more seeds to work on optimizing horticulture protocols. To test and improve propagation success, we experimented with different pot sizes and growing media. We planted Asclepias in both 3-inch standard square pots and 2x7-inch tube pots (Figure 5). We were curious to see if the milkweeds would grow better in tube pots, considering that at least one of the species (A. tuberosa) has a long tap root that most likely prefers more room to grow downwards. However, we also tried the 3-inch pots since our end goal with these plants is distribution and 3-inch pots are easier to distribute than the longer tube pots (because the tube pots do not stand on their own).

After 5 months, the survival rate of Asclepias viridis was found to be the same for both the 3-inch pots and the tube pots (Figure 6). Asclepias verticillata also had a high survival percentage in both types of pots. In contrast, Asclepias tuberosa had only a 50% survival rate in the 3-inch pots

and a ~90% survival rate in the tube pots; we can assume that this tap-rooted species grows more comfortably in the tube pots. We also tried growing the milkweed species in different growing media to see if that affected survival. We tried both a “rocky mix” and a “sandy mix.” The rocky mix, which allowed quick drainage, was comprised of one third standard potting soil, one third crushed limestone, and one third Turface (a chipped clay product). The sandy mix, which was more moisture-retentive, was made using one third standard potting soil, one third crushed limestone, and one third silica sand. After four months of growth in both mixes, we found that the survival of Asclepias seedlings did not differ very much, but Asclepias viridis and Asclepias tuberosa grew about 20% better in the rocky mix than the sandy mix. Thus, we now only grow milkweeds in the rocky mix.

After optimizing horticulture protocols, we generated a living ex-situ collection of all three milkweed species and ended up with nearly 200 Asclepias plants from 18 different maternal lines: 83 A. tuberosa, 43 A. verticillata, and 74 A. viridis. After one year, many of the plants in the collection had established themselves and were flowering steadily in their pots. We also made a point to examine their root growth (Figure 7). When we cultivated plants at Fairchild’s nursery, we observed that all three species periodically became dormant with no above ground vegetation and then resprouted from their extensive tap root. This is an important thing to note for these species. If homeowners would like to plant native milkweeds in their gardens, then they must realize that because of the plant’s biology, they will not always be vegetative above ground.

Cultivated A. verticillata plants readily produced seed pods at the Fairchild nursery and to date, we have collected 4,013 seeds from this species (Figure 8). Although the other two species flowered abundantly, they rarely formed any pods. We hypothesized that the pollinator of these species is not abundant at Fairchild’s nursery, which is located 2.5 miles from the nearest pine rockland preserve. Through the course of the project, three A. tuberosa plants eventually produced one seed pod each and we harvested 138 seeds. Unfortunately, A. viridis plants have not produced any seed pods to date and our attempts at hand pollination were not successful. All 4,013 Asclepias verticillata seeds and 107 of the total 138 Asclepias tuberosa seeds have been frozen in Fairchild’s seed bank. Additionally, we observed a diversity of insects visiting all three species (Figure 9) and we note that monarch caterpillars seemed to prefer A. viridis over the other two species.

Article by Leslie Nixon

Photos by Laura Langlois-Zurro

In the current age of the Anthropocene, in which humans dominate the planet Earth, many species of plants and animals are struggling for survival. For the vast majority of these species, a single person can have little direct effect on their success. However, there is one group of animals that individuals can help conserve – native bees (Krueger, 2022). Bees are easy to support because they are so small. They require many fewer resources than, say, a Florida panther, so homeowners can make provisions for them in their own yards.

To be clear, we are talking about Florida’s native bees, not honey bees, which were originally imported from England in the 17 th century and are now managed as an agricultural commodity. There are more than 4,000 native bee species in the United States, and over 300 species are native to Florida, including 29 species that are endemic to the state (Krueger, 2022). Florida’s native bees are diverse and come in a variety of sizes, shapes and colors – some even look more like wasps than bees.

Native bees such as bumble bees, mason bees, and sweat bees do not live in permanent hives and do not sting unless provoked. They are a vital part of Florida’s ecosystems, but their numbers are dropping at an alarming rate. Recent research has shown that more than 50% of North America’s native bee species are declining (Kopec & Burd, 2017). The reasons for this decline are many and include loss of habitat, overuse of pesticides, invasive species, climate change, and competition with honey bees (Kopec & Burd, 2017; Xerces

Society, 2023b). Losing more native bees could be disastrous for our ecology because native bees are responsible for pollinating 75% of native plants (United States Geological Survey). How can we preserve, conserve, and restore the flora of Florida without native bees?

Fortunately, it is easy for home gardeners to support native bees by planting bee-sustaining Florida native plants. Florida’s bees coevolved with native plants over millions of years to form symbiotic relationships in which the bees and the plants depend on each other for reproduction. Adult bees feed on pollen and nectar from flowering plants, while plants enlist bees to spread their pollen from flower to flower. While male bees only drink nectar, female bees also feed on pollen at some stages of their life cycles,

and pollen is the main source of protein for nourishing bee larva. Of course, there are many types of animals that pollinate plants, but bees are not your average pollinator; they are in fact super pollinators. Bees actively collect pollen during foraging whereas other pollinators only accidentally transfer it while focusing on nectar. In addition, bees tend to visit only one species of flower on each foraging trip (Xerces Society, 2023b). This phenomenon, called flower constancy, improves the efficiency of bee pollination which naturally benefits both bees and plants.

While most native bees are generalists and collect pollen and nectar from a variety of flowering plants, 28% of Florida’s bees are specialists who require the pollen of particular native plants to survive (Fowler & Droege, 2020). Specialist bees might depend on the pollen of one certain plant species or they could be a bit less choosy and forage on a particular genus or family of plants. These specialist bees evolved in strict ecological relationships with their host plants and are in danger of extinction if their hosts disappear. One example of this relationship is the blue calamintha bee (Osmia calamintha) and the threatened plant Ashe’s calamint (Calamintha ashei), both residents of Florida’s Lake Wales Ridge.

Therein lies the problem with non-native plants. Generalist bees may visit and pollinate non-native plants, but specialist bees can’t survive on foreign pollen (Fowler & Droege, 2020, Tallamy, 2019). Thus, non-native plants can lead to a loss of bee species and bee diversity. The increase in planting of non-native plants has been implicated in the decline of insects in general (Tallamy et al., 2020).

The good news is that there are many Florida native plants available for use in the home landscape that feed both generalist and specialist bees. Figure 1 is a diagram of a sample bee garden. Table 2 lists common, easy-to-grow Florida native plants that befriend bees. The list is not exhaustive, but it includes native plants with abundant pollen and nectar favored by native bees. Use these two tools to build better bee habitat in your yard.

In choosing and planting food sources for bees, there are three guiding principles:

l Serve up a continuous, year-long buffet of flowers. Different bee species are active at different times throughout the year. Providing flowers year-round accommodates all types of bees. Even in north Florida there are bees foraging in winter (Langlois-Zurro, 2022). To make sure as many bees as possible have food available, entomologists recommend having at least three plant species blooming at any given time (Mallinger et al., 2019). This diversity not only feeds more kinds of bees, it also improves the ecological function and resilience of your garden.

l Choose flowers with the color and shape that attract bees. Bees prefer white, yellow, and blue-purple flowers. Since they can’t see the color red (Shipman, 2011), that intense color has little appeal for them – so balance the bright red flowers that attract hummingbirds to your garden with more subtle colors attractive to bees. Native bees also have preferences for

flower shape and size. Larger species, such as bumble bees can access flowers with long tubes like coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens). But smaller species with short tongues cannot access pollen or nectar deep down in long tubular flowers (Mallinger et al., 2019). For them, plant easy-access flowers with flat faces such as asters, and those with shorter, more open tubes, like manyflower beardtongue (Penstemon multiflorus) or largeflower false rosemary (Conradina grandiflora). Even flower size can make a difference. Tiny bees have smaller ranges and often visit small flowers such as frogfruit (Phyla nodiflora). Bees are busy enough as it is, what with mating, building nests, and feeding their young; make it easy for them to step up to the buffet.

l Plant flowers in groups. A mass of flowers acts as a flashing neon sign to entice hungry bees to stop on in. Rather than scattering flowers around your landscape, arrange at least three of the same species together to lure bees and to simplify their foraging efforts. Flying relentlessly from flower to flower takes a lot of energy; planting flowers in groups helps bees be more efficient in their quest for food. Grouping flowers also helps the plants increase their pollination rate which improves plant reproduction (yielding more plants for you).

Here are more ideas to optimize your landscape for native bees.

l Flowers for bees bloom best in sites with full sun. Six or more hours of sun per day is ideal, but a partly sunny location (4-6 hours of sun per day) will provide adequate energy for flowering. There won’t be as many blooms in a less sunny location, but bees will still benefit from your floral banquet.

l Include host plants for specialist bees. If you only plant flowers for generalist bees, you will get only generalists. If you grow host plants for specialist bees you may attract both specialist and generalist bees, so plant for the specialists and the generalists will come (Fowler & Droege, 2020, Tallamy, 2019). To find out more about specialist bee species and the plants they visit, see Pollen Specialist Bees of the Eastern United States, online at: https://jarrodfowler.com/specialist_bees.html.

l Add a small tree or a few shrubs to your wildflowers. Most people think of wildflowers when planting for bees, but

woody plants are also bee-worthy as they reliably produce abundant arrays of flowers every year. Some of these sturdy perennials tend to bloom in late winter, thereby feeding early season bees. You can create sufficient habitat for bees with wildflowers alone, but including a variety of plant forms adds an extra ecological dimension to your landscape.

l Avoid insecticides. Most insecticides are non-selective, meaning they kill any insect that comes in contact with them, including bees. Instead of using pesticides, which also kill insect predators that keep pests under control, try alternative methods

like hand removal or trimming back affected areas. Native plants are used to being browsed by insects; it is a natural and (usually) non-fatal process for them, so try letting the bugs be.

l Purchase plants from a reputable native nursery. These nurseries are knowledgeable and enthusiastic about natives. Their plants should be free of pesticides. To be sure to get plants appropriate for your site, shop local, within 50 miles of your home. Locate a native nursery near you at PlantRealFlorida.org.

l Support the complete life cycle of native bees. Like any animal, bees need more than just food to survive: they need a place to rest and raise their young. Native bees don’t live in permanent hives. Seventy percent of them live in the ground while the other 30% are cavity-nesters, making homes in dead wood (Xerces, 2023a). Invite the ground-nesters to move in by maintaining patches of bare soil in your garden – sandy, sunny areas are preferred by most ground-nesting bees. Avoid using heavy mulch or materials like weed cloth. Instead, a light covering of fallen leaves or pine straw will allow bees to readily enter the soil. Cavity-nesting bees build their homes in stumps, logs, or stems. For them, maintain a brush pile or retain a log from a hurricane-downed tree. Stem-nesting bees create nurseries in old flower stalks, so to encourage their next generation, leave stems and flower heads intact until early

spring. This also provides roosting areas for male bees, who do not return to the nest once they have emerged.

l It’s OK to start small. Don’t get overwhelmed by thinking you need to create a large bee garden in one season. Start with a group of shrubs, a small tree, and a few wildflower species planted around it. You can also begin by simply adding bee-beckoning plants to your existing beds. Then enlarge your bee garden as space and time permit. Soon you will want to add a bench where you can sit and enjoy the seasonal flowers and the bustling activity of the bees (as well as their less-productive pollinating coworkers).

Bees might be tiny, but their impact is huge and it’s hard to imagine life without them. As companions to bees for millions of years, Florida native plants are the natural way to support endangered native bees. With Florida natives you can welcome both beauty and the bees to your garden.

Florida Native Plant Society (2022). Native plants for your area. https://www.fnps.org/plants

Fowler, J. (2020). Host plants for pollen specialist bees of the eastern United States. https://jarrodfowler.com/host_plants.html Fowler, J. & Droege, S. (2020). Pollen specialist bees of the eastern United States. https://jarrodfowler.com/specialist_bees.html

Kopec, K. & Burd L.A. (2017, February). Pollinators in peril. Center for Biological Diversity.https://www.biologicaldiversity. org/campaigns/native_pollinators/pdfs/Pollinators_in_Peril.pdf

Krueger, R. (2022, August 5). Five facts: bees in Florida. Florida Museum. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/ five-facts-bees-in-florida/

Langlois-Zurro, L. (2022, Dec.). Florida’s native bees in winter. Florida Wildflower Foundation. https://www.flawildflowers. org/221214-webinar-floridas-native-bees-in-winter/ Langlois-Zurro, L. (2021, April). Welcome Florida’s Native Bees Into Your Yard. Bay Soundings. https://baysoundings.com/ welcome-floridas-native-bees-into-your-yard/

Mallinger, R. E., Hobbs, W., Yasalonis, A., & Knox, G. (2019, October). Attracting native bees to your Florida landscape. UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida. https://edis.ifas.ufl. edu/publication/IN1255

National Wildlife Federation. Keystone native plants, eastern temperate forests - ecoregion 8. https://www.nwf.org/-/media/ Documents/PDFs/Garden-for-Wildlife/Keystone-Plants/NWFGFW-keystone-plant-list-ecoregion-8-easterntemperate-forests

Pascarella, J.B. & Hall, H.G. (N.D.) The Bees of Florida. https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/HallG/Melitto/Intro.htm (Dianthidium) https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/hallg/melitto/floridabees/dianthidium.htm

Shipman, Matt (2011, July 27). What do bees see? And how do we know? https://news.ncsu.edu/2011/07/wmswhat-bees-see/

Tallamy, D. W. (2019). Nature’s Best Hope. Timber Press. Portland, Oregon

Tallamy, D. W., Narango, D. L., & Mitchell, A. B. (2020). Do non-native plants contribute to insect declines?

Ecological Entomology. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12973 United States Geological Survey. What is the role of native bees in the United States? https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/whatrole-native-bees-united-states

Xerces Society. Nesting resources. (2023a). https://xerces. org/pollinator-conservation/nesting-resources

Xerces Society. Wild bee conservation. (2023b). https://xerces. org/endangered-species/wild-bees

Florida Native Bees (Facebook group)

How to save flower stems for bees: https://cpb-us-w2. wpmucdn.com/u.osu.edu/dist/1/117433/files/2022/10/ heather-holm-StemNestingBees-copy.pdf

Identifying native bee species: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN1285

Nesting sites for bees: https://xerces.org/blog/5-ways-toincrease-nesting-habitat-for-bees

Specialist bees: https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/ science/floridas-rare-blue-calamintha-bee-rediscovered/ and https://jarrodfowler.com/specialist_bees.html

(CONTINUED FROM PAGE 7)

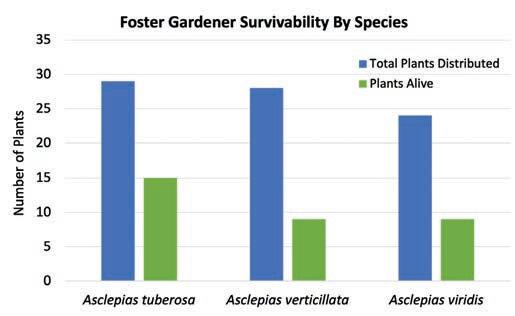

To work towards our project goal, we distributed seed-grown plants from our ex-situ population to thirteen foster gardeners in September of 2021. Each foster gardener received two plants of each species; we distributed 81 plants in total (Zoo Miami’s butterfly bunker received 3 extra plants for 9 plants in total). We waited until March of 2023 and then surveyed the foster gardeners on the health of their Asclepias plants. We found that Asclepias tuberosa had the highest survival rate of the three species in the foster gardens. Out of the 29 plants distributed, 15 A. tuberosa are still alive (52%). The next highest survival was the A. viridis with 37.5% survival. Lastly, A. verticillata had 32% survival (Figure 10).

to expand our living collection and ex-situ seed production for all three Asclepias species. Our ultimate goal with this project was to make this plant available to local butterfly gardeners and restoration projects. Albeit still on a limited basis, we have met and plan to continue meeting this goal by growing and distributing more milkweed plants to both local homeowners and organizations for use in native plant gardening and restoration projects throughout Miami-Dade County.

Atlas of Florida Plants. 2023. http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu

Coons, J., Coutant, N., Lawrence, B., Finn, D., & Finn, S. 2014. An effective system to produce smoke solutions from dried plant tissue for seed germination studies. Applications in Plant Sciences, 2(3), 1300097.

Leslie Nixon is a semi-retired feline veterinarian. She spends her free time volunteering with the FNPS Pawpaw Chapter and cultivating Florida native plants in her yard. Naturally, her favorite part of growing natives is observing all the animals they attract.

Laura Langlois-Zurro is the founder of the Florida Native Bees Facebook group. She documents native bee behavior and inspires appreciation of native bees through her videos, photographs, and observations. Follow her on Instagram – @EcoGeekMama.

Through this project, so much was learned that can be applied to our Asclepias species’ seed and horticulture protocols at Miami’s Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. We identified some of the various quirks these species have when seed-grown in cultivation in our South Florida climate, and we discovered which Asclepias species did best in the care of our foster gardeners. Most importantly, we are better able to navigate and troubleshoot Asclepias cultivation after this project. We are taking the knowledge learned during this phase of the project and moving forward with a more precise protocol, not only for ourselves, but also for the members of Fairchild’s Connect to Protect Network, a group of native plant gardeners who grow pine rockland plants in their yards.

The work is far from over. We are continuing

Gann G. D., Trotta L.B., and Collaborators. 2001-2023. Floristic Inventory of South Florida Database Online. The Institute for Regional Conservation. Delray Beach, Florida. Society for Ecological Restoration, International Network for Seed Based Restoration and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. 2023. Seed Information Database (SID). Available from: https://ser-sid.org

Lydia, Sabine, Samantha, and Jennifer are part of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden’s plant conservation program where they work to reduce the extinction risk of locally rare and endangered plants in Florida and the Caribbean.

We would like to thank FNPS and its conservation committee, the Dade Chapter board, Miami-Dade County Environmentally Endangered Lands Program, Fairchild Conservation Horticulturist Brian Harding, and the CTPN Foster Gardeners that made this project possible.

(CONTINUED FROM PAGE 2)

even more information on how to choose native plants for home landscapes.

Ongoing garden maintenance is now being done by volunteers but it will eventually be taken over by the county. PIAS plans to host educational field trips to the garden to help people learn how they can design their own gardens, how to identify native plants, and to encourage them to

reluctance people have to changing their turf lawns, which they are used to, but native plants are beautiful for economic as well as ecological reasons.”

Stephanie Dunn of Cadence Landscape Architects designed the administration building native garden, planted many of the plants, directed volunteers, assisted with the installation of the path, and continues to provide advice on the project as it matures. Dunn says the plant species were chosen not only for their ecological benefits, but also to provide an example of readily available and easy to grow native plants that would inspire visitors to plant native at home.

Creating the garden was a group effort with many volunteers and donors participating. Before planting, the ex isting turfgrass in the 1,125 square foot garden was killed by covering it with recycled cardboard and a layer of pine straw, a method known as sheet mulching. Next, 32 volunteers spent seven hours installing the native plants, digging through the sheet mulched surface.

After the completion of the county administration building garden, Matt Tanner, Executive Director of the nonprofit United Against Poverty Indian River County (UP) requested that a similar Education and Demonstration Native Plant Garden be created at their location. UP helps families to succeed by becoming economically self-sufficient through various enrichment services. Its mission is to provide crisis care, case management, transformative education, mentorship and resume building, food and household subsidies, employment training and referrals to other collaborative social-service providers. UP also provides counseling and veterans assistance, and they run a large grocery with community-donated items for those below the Federal poverty line. The UP center has hundreds of daily visitors, with more than 10,000 visitors annually.

A walking path covered with wood chip mulch was created, and plant identification signs with QR codes were installed to make it easy for visitors to learn more about the plant species they encounter. A sign post was placed along the path that contains brochures visitors can take home. These recommend native plant species for birds, butterflies, and bees, and also contain links to the Florida Native Plant Society and National Audubon Society websites to provide

PIAS was awarded an FPL/Audubon Florida Plants for Birds grant to help fund the UP garden, which was designed by Stephanie Dunn and installed in January, 2023. The goals of the UP garden are to demonstrate the benefits of native plants and to beautify the community.

Turfgrass was removed from three separate areas, and 23 volunteers planted 223 native plants of 27 species. Shortly after planting, a carelessly discarded cigarette landed on pine straw mulch in front of the UP mural, burning ten square feet of the garden and destroying plants and irrigation hoses. UP staff put out the fire, and later installed a sign warning visitors to dispose of cigarette butts

properly. The damaged plants, hoses and pine straw were replaced and now frogfruit and many other plants have expanded to cover the pine straw. After completing the UP garden, PIAS gave away 416 native trees and plants to UP visitors to take home and grow in their own yards, along with instructions on planting.

PIAS continues to move forward with the Trees for Life/Plants for Birds project. In addition to planting the demonstration gardens, volunteers

installed native plants at five elementary and high schools in Indian River County, and the Society hosts free native tree giveaways and classes that teach people how to plant their new trees. PIAS also maintains a plant nursery at its location in Vero Beach where visitors can select free trees and purchase native plants at low cost. As of July, PIAS had distributed 18,828 native plants, including 8,206 trees. Many of the live oak and mahogany trees were grown from acorns and seeds by volunteers, while others were generously donated by Sebastian River Farms and Cherry Lake Nursery.