BUILDING UNITY

As 2025 comes to a close, we want to take a moment to celebrate what we have accomplished together and share our excitement for the year ahead This year was filled with growth for FMHCA We brought members together at seven networking events across Florida, each one creating opportunities to connect, collaborate, and strengthen our professional community.

Looking toward 2026, we are pleased to announce a new membership structure that will go into effect on January 1, 2026. These updates were designed with you in mind, adding new perks and benefits that will make membership more valuable than ever Current members who renew before December 31, 2025, will be grandfathered into the 2025 membership rate, so we encourage you to take advantage of this opportunity

We are also excited to share that our GRC Fund Run (or Walk!) begins now through the end of the month. This event is a great

way to get moving while supporting FMHCA’s Government Relations Committee Every shirt purchased and every registration directly supports our advocacy efforts, so we encourage you to join in, bring colleagues along, and proudly wear your race shirt knowing that all proceeds go toward advancing the counseling profession in Florida.

Of course, one of the highlights on the horizon is the 2026 Annual FMHCA Conference This event is always a cornerstone of our work together, offering days of education, connection, and inspiration for counselors across the state We look forward to welcoming you there as we continue to advance our profession and strengthen our community

On behalf of the FMHCA Office, thank you for your dedication and engagement throughout 2025 We are grateful for each of you and excited to see what we can accomplish together in 2026

43

46 FMHCA Committee Updates

Page 52

the Expert

InSession Magazine is created and published quarterly by The Florida Mental Health Counselors Association (FMHCA)

FMHCA is a 501(c)(3) non for profit organization and chapter of the American Mental Health Counselors Association.

FMHCA is the only organization in the state of Florida that works exclusively towards meeting the needs of Licensed Mental Health Counselors in each season of their profession through intentional and strengthbased advocacy, networking, accessible professional development, and legislative efforts

Let your voice be heard by becoming a FMHCA Member today!

Click here to view FMHCA's current Bylaws

CONTRIBUTE:

If you would like to write for InSession magazine or purchase Ad space in the next publication, please email: Naomi Rodriguez at naomi@flmhca.org

THE INSESSION TEAM:

Naomi Rodriguez- Editor

Victoria Siegel, LMHC- Expert Advisor

There shall be no discrimination against any individual on the basis of ethic group, race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, age, or disability

Information in InSession Magazine does not represent an official FMHCA policy or position and the acceptance of advertising does not constitute endorsement or approval by FMHCA of any advertised service or product. InSession is crafted based on article submissions received. Articles are categorized between Professional Experience Articles & Professional Resource Articles.

Professional Experience Articles are writer's firstperson pieces about a topic related to their experience as a mental health professional, or an opinion about a trend in the mental health counseling field

Professional Resource Articles are in-depth pieces intended to provide insight for the author's clinical colleagues on how to be more effective with a particular type of client or a client with a particular disorder, or tips for running their practice more efficiently

The Florida Mental Health Counselors Association (FMHCA) is the State Chapter of the American Mental Health Counselors Association (AMHCA) FMHCA is the only organization dedicated exclusively to meeting the professional needs of Florida’s Licensed Mental Health Counselors

The mission of the FMHCA is to advance the profession of clinical mental health counseling through intentional and strengthbased advocacy, networking, professional development, legislative efforts, public education, and the promotion of positive mental health for our communities

Its sole purpose is to promote the profession of mental health counseling and the needs of our members as well as:

Provide a system for the exchange of professional information among mental health counselors through newsletters, journals or other scientific, educational and/or professional materials

Provide professional development programs for mental health counselors to update and enhance clinical competencies

Promote legislation that recognizes and advances the profession of mental health counseling

Provide a public forum for mental health counselors to advocate for the social and emotional welfare of clients

Promote positive relations with mental health counselors and other mental health practitioners in all work settings to enhance the profession of mental health counseling

Contribute to the establishment and maintenance of minimum training standards for mental health counselors

Promote scientific research and inquiry into mental health concerns

Provide liaison on the state level with other professional organizations to promote the advancement of the mental health profession

Provide the public with information concerning the competencies and professional services of mental health counselors

Promote equitable licensure standards for mental health counselors through the state legislature

Professional Experience Article

In the ever-shifting terrain of modern life, our clients are not only navigating internal challenges but also external environments that shape their sense of identity, safety, and connection. For LGBTQIA2S+ clients in particular, therapeutic support must move beyond the “what’s wrong” model and into a broader recognition of “where are you?” and “what’s shaping your current experience?”

One powerful way to meet this need is to attune ourselves and our clients to the concept of third spaces.

Traditionally, “third spaces” are locations outside of home (first space) and work (second space) where individuals can find belonging, expression, and social identity. These include coffee shops, bookstores, community centers, hobby groups, and more recently, online communities. For LGBTQIA2S+ individuals especially those who may have experienced marginalization in their first and second spaces third spaces have often provided the critical context where their authentic self can safely emerge.

Historically, gay bars, activist collectives, and queer bookstores served as these vital third spaces. Over time, the landscape has evolved. Today, many queer individuals find community through tabletop gaming groups, fandom conventions, Twitch streams, queer Dungeons & Dragons campaigns, and other niche digital ecosystems that function as chosen family and

identity-affirming sanctuaries.

As therapists, understanding and exploring these third spaces can be transformative in helping our clients anchor themselves through periods of stress, disconnection, or transition.

Third spaces offer something incredibly therapeutic: the chance to be known in a lowstakes, non-performative way Clients often report feeling safer in these environments than in their workplaces or even in family settings. These spaces support core psychological needs such as:

Belonging: The feeling of being accepted without condition.

Agency: The freedom to explore and express identity on one ' s own terms.

Community Regulation: A soft accountability from peers who model resilience, creativity, and mutual care.

For LGBTQIA2S+ individuals, who often grow up having to “scan and adapt” for safety in heteronormative environments, these third spaces allow them to exhale That exhale can be the difference between surviving and thriving.

In clinical work, we can help our clients locate, nurture, and engage with third spaces through questions like:

“Where do you feel most like yourself?”

“Is there a group or environment real or virtual where you feel seen or understood?”

“How do you show up differently there compared to work or home?”

By incorporating these conversations, we also model that emotional regulation and healing are not just internal processes but contextually bound. A queer client who feels numb or anxious at home may come alive in a cosplay group or while streaming with affirming friends

That shift is not avoidance it’s adaptation.

Written By: Dr. Josh Littleton, LMHC, CST, NCC

Dr. Josh is a licensed psychotherapist and clinical sexologist specializing in relational wellness, LGBTQIA2S+ affirming care, and trauma-informed therapy. With over a decade of experience, he blends evidence-based practices with creativity and compassion. Dr. Josh is passionate about helping clients reclaim their voice, deepen connection, and navigate life’s transitions with authenticity, resilience, and joy.

Creative Arts Therapy as Applied to Active Imagination, an Analytical Psychology Technique

03 October 2025 | 2:00 PM-4:00 PM

Presented by: Teda Kokoneshi, LMHC Register Now

Helping Clients Heal from Narcissistic Abuse (Domestic Violence)

10 October 2025 | 2:00 PM-4:00 PM

Presented by: Stephanie Sarkis, PhD, NCC, LMHC Register Now

Leadership and Advocacy within Counselor Education: Testifying for Clients

17 October 2025 | 2:00 PM-4:00 PM

Presented by: Kendria Brown, LMHC Register Now

Sexuality and Addiction

31 October 2025 | 2:00 PM-4:00 PM

Presented by: Carol Clark, Ph.D., LMHC, CAP, CST Register Now

Which is Best? Parent Coordination, Co-Parent Therapy, Reunification Process, or Family Therapy

07 November 2025 | 2:00 PM-4:00 PM

Presented by: Christine Hammond, LMHC, NCC Register Now

Navigating Ancient Traditions: Working with Clients Within Their Meaning-Making Systems

14 November 2025 | 2:00 PM-4:00 PM

Presented by: Colette McLeod, LMHC, CCM Register Now

Join in on one of our upcoming webinars! & More!

P.S. We are seeking presenters for our 2026 Webinar Series until Nov. 1st! Learn more HERE

Professional Resource Article

The landscape of psychotherapy has undergone a significant transformation, with the most profound change occurring post pandemic, creating a rapid shift to teletherapy. This evolution has underscored the critical importance of understanding how to build and maintain robust therapeutic relationships and a strong therapeutic alliance in both traditional face-to-face and emerging online environments.

Decades of psychotherapy research consistently demonstrate that the therapeutic relationship and alliance are the most reliable predictors of therapeutic change. While these relational factors are critical, the concept of therapeutic presence has proven to be a foundational element, essentially serving as a precondition for effective therapeutic relationships and a strong therapeutic alliance. This article delves into the definition and comprehensive understanding of therapeutic presence, explores factors that can impede it, and discusses the unique challenges it faces in online therapy.

What illustrates Therapeutic Presence?

Therapeutic presence is defined as a way of being with a client

that optimizes both the "doing" and "technique" of therapy It involves therapists bringing their whole selves to the therapeutic encounter, being fully present on a multitude of levels: physically, emotionally, cognitively, relationally, and spiritually. This deep engagement enables therapists to attune to their own moment-to-moment experiences as well as those of their clients.

At its core, therapeutic presence involves:

Being grounded and in contact with one's integrated and healthy self. This provides a steady base for the therapist amidst challenging emotions

Being open and receptive to what is poignant in the moment, and being immersed in it This involves receptively taking in the client's verbal and nonverbal experience and being responsive in the moment.

A sense of spaciousness and an expanded awareness and perception. This allows for a broad, non-judgmental awareness.

Operating with intention, to be with and for the client, in service of their healing process. The singular purpose is the client's healing, transcending any self-centered goals or desire for a particular outcome.

By noting these elements, therapists can begin to conceptualize therapeutic presence and its importance in the therapeutic process.

The concept of therapeutic presence is trans-theoretical, meaning it is recognized as valuable and applicable across various psychotherapeutic approaches, making it a " common factor" in effective therapy. Historically, psychoanalysts such as Sigmund Freud and Theodore Reik spoke of "evenly suspended attention" and "listening with a 'third ear ' , " reflecting an open, spacious, and attentive state. Carl Rogers, a pioneer of clientcentered therapy, viewed presence as an underlying condition for empathy, unconditional regard, and congruence. In his later reflections, Rogers even suggested that his initial emphasis on the three basic conditions, congruence, unconditional positive regard, and empathic understanding, might have been an "overemphasis," with the "obvious and clear presence of the therapist as the most significant element of therapy" Modern psychodynamic, Existential, Gestalt, Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT), Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy (AEDP), and even Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) approaches now highlight the importance of presence Research shows that clients who rated their therapist as present were more likely to rate the therapeutic alliance and session outcome positively across different therapy types.

From a neurophysiological perspective, specifically through the lens of Porges' Polyvagal Theory, therapeutic presence plays a crucial role in creating a sense of safety Our nervous systems are in constant bidirectional communication. When therapists are fully present and attuned, their receptive and safe presence sends a neurophysiological message to clients that they are being heard, met, felt, and understood. This process fosters a reciprocal experience of safety for both the therapist and the client, thereby strengthening the therapeutic alliance. This is mediated by what's known as neuroception an automatic and often unconscious evaluation of risk in the environment. When features of safety are detected, defensive mechanisms are down- regulated, promoting social engagement behaviors. For clients, especially those with trauma histories, this safe therapeutic environment facilitates the development of new neural pathways, helping to repair attachment injuries and fostering neural growth Therapists' presence also serves as a co-regulator for clients' emotions, with attuned limbic resonance and right-brain to right-brain communication (nonverbal cues, such as body posture, vocal expressions, and facial expressions) facilitating regulation. This "neuroception of safety" allows clients to enter their "window of tolerance," enabling them to engage in the necessary therapeutic work and express vulnerabilities.

The Therapeutic Presence Inventory (TPI), developed by Geller and colleagues, includes both a therapist (TPI-T) and client (TPI-C) version, with research suggesting that the client's perception of the therapist's presence (TPI-C) is a stronger predictor ofpositive therapeutic alliance and session outcome than the therapist's self-reported presence. This underscores that presence only impacts clients if they perceive the therapist as present with them. Therapeutic presence evolves into a relational experience, where the mutual presence of therapist and client fosters both "relational depth" and healing.

Reality tells us that therapeutic presence can be challenging to sustain, given that therapists, being human, also face their own internal and external barriers. Recognizing these potential blocks is essential for maintaining an attuned and effective therapeutic relationship:

Hyper-intellectualization: A therapist's tendency to overanalyze or focus too heavily on theoretical frameworks and analytical processing can hinder experiential processing and shift them out of present-moment contact with the client. This can lead to missing subtle client signals or failing to respond appropriately.

Fear/Anxiety/Self-doubt: Therapists may experience their own anxiety, fear, grief, or trauma around what's going on in the world, often echoing what our clients bring into session. This can be triggered by clients' distress, leading to self-doubt (e.g., "impostor syndrome") and hindering their ability to be fully present and responsive.

Fatigue: Sitting in a chair for hours on end and being on a computer for extended periods These are common in both in-person and teletherapy, and can lead to disconnection and exhaustion if not balanced with other activities and breaks General stress, social isolation, and lack of outdoor time can amplify therapist fatigue This exhaustion can make it challenging to maintain one ' s presence and even lead to burnout.

Reactivity (Countertransference): Therapists' own unresolved issues can be activated by clients' shared distress, leading to countertransference responses. This internal reactivity can interfere with the therapist's ability to stay grounded, attuned, and truly present.

Distractibility: Clients may be in their home environments with distractions, but therapists can also be distracted by internal thoughts (e.g., self-doubt, planning the subsequent intervention) or external factors (e.g., technological glitches, background noises in their own space). These distractions pull the therapist out of the moment with the client

Lack of Self-Care: Sustaining presence demands significant personal resources and active engagement from the therapist Without intentional self-care practices, there is an increased risk of burnout, which compromises the therapist's ability to maintain presence in sessions.

The sudden and widespread adoption of teletherapy in early 2020 presented unique challenges for cultivating therapeutic presence and strengthening therapeutic relationships online. Therapists, many of whom had minimal prior experience in teletherapy, had to adapt their practices quickly.

Some key challenges include:

Limited Non-Verbal Communication: Teletherapy creates physical distance between the therapist and client, significantly limiting the ability to perceive and express non-verbal cues. A core aspect of therapeutic presence involves using body-to-body non-verbal cues (e.g., prosodic vocal tone, leaning forward, gesturing, open body posture, soft facial features, mutual eye gaze, mirroring movements) to communicate presence and safety. When online,

therapists have reduced access to clients' physical cues (gestures, posture, full-body non-verbal expressions) and a reduced ability to express their own presence with their whole body, limiting the capacity to attune and convey safety and trust.

Technological Challenges and Training Gaps: Technical glitches, delays, or freezes in technology can impact therapeutic presence and the therapeutic alliance. There is legitimate concern that clients may attribute these technical issues to the therapist's skills or lack of presence rather than the technology itself. Many therapists may still benefit from training in navigating virtual platforms or conducting therapy online, as well as ways to avoid or respond to clients who face technology-related challenges

Client Environment and Safety: Clients may be in their home environments, potentially with family members or others with whom they have emotional challenges, making it difficult to feel safe or private enough to express complex emotions and vulnerabilities Emphasizing to clients the importance of having private spaces within their homes is crucial.

Increased Therapist Fatigue and Countertransference:

As noted earlier, prolonged online presence can lead to disconnection and exhaustion. Therapists' fatigue may be exacerbated by their own stress related to social isolation and a lack of balance between outdoor time and other commitments.

Therapist Bias: Some therapists historically held negative views towards telehealth, potentially impacting their approach to online therapy and inhibiting the development of a positive therapeutic alliance Shifting this bias is imperative, as online treatment has remained a mode of service delivery

Despite these challenges, research suggests that teletherapy is effective for various disorders and can foster a positive working alliance. Nursing literature and some psychotherapy studies even indicate that presence can be felt and generated online, with concepts like " co-presence " (the illusion of sharing the same distant space) highlighting the potential for therapists' minds and bodies to transcend time and space, creating a feeling of being together

To effectively embody and practice therapeutic presence with clients, therapists are advised to create a comprehensive approach that integrates self-preparation (i.e., grounding before sessions), in-session techniques (i.e., process experiential interventions), and strategies for managing challenges both in the office and online. Therapeutic presence, defined as bringing one ' s whole self to the encounter

physically, emotionally, cognitively, relationally, and spiritually is considered a precondition for effective therapeutic relationships and a positive therapeutic alliance

Recommendations for Counselors Cultivating Therapeutic Presence:

Prioritize Self-Care and Preparation: Therapists should engage in personal practices, such as mindfulness and selfcompassion, to strengthen qualities like attention, awareness, warmth, and sensitivity Before sessions, it is beneficial to take 5-10 minutes to center oneself through mindful breaths or grounding exercises to activate embodied presence Intentional self-care, including physical activity and non-screen time, is crucial for preventing burnout and sustaining presence, particularly during online work.

Optimize the Therapeutic Environment: When working online, therapists should create a consistent and predictable environment that mirrors their in- person therapy room as much as possible. This includes ensuring HIPAA/PHIPA compliance for security and confidentiality. Attention should be paid to optimal lighting that allows clear visibility of facial expressions, and therapists should position their camera and notes at eye level to maintain direct eye contact. Clients should also be encouraged to ensure their privacy and minimize distractions in their own environment

Communicate Presence During Sessions: Therapists must actively convey their presence, empathy, and resonance This involves making facial expressions visible, using a prosodic (rhythmic, warm, varied) vocal tone, and displaying open body posture and gestures. Maintaining mutual eye gaze and mirroring clients'expressions, vocal tone, and breathing rhythm can foster a sense of safety and connection. Being open and receptive to the client's moment-to-moment experience without distraction or fixation is also key. Therapists should also stay attuned to their own internal experience, recognizing emotional resonance or countertransference, and track clients' microexpressions and nonverbal cues to adjust their presence and empathy as needed.

Manage Challenges and Ruptures: Therapeutic presence can be challenging to sustain due to factors such as hyperintellectualization, fear, fatigue, reactivity, and distractibility When personal anxieties or technological glitches arise, therapists are encouraged to practice selfcompassion, acknowledge the issue, and use grounding practices like a " pause, notice, return" (PNR) technique to re-center. Authenticity in acknowledging humanness

during challenging moments can also be beneficial for both therapist and client

Integrate Training: Understanding how presence evokes psychological and emotional safety (interoception), often without conscious awareness (neuroception), is vital. Therefore, training in cultivating therapeutic presence, including its neurophysiological underpinnings and practical exercises to enhance the social engagement system, should be an essential component of psychotherapy education across all modalities.

Clinical Consultation and Supervision: Clinical consultation and supervision play a vital role in helping therapists cultivate therapeutic presence by supporting the inner work of "how to be" with clients The relationship between therapist and supervisor also works in a "parallel process, " modeling the same presence that is expected in therapy sessions Supervisors guide therapists in preparing for sessions and managing blocks and barriers, such as fear, fatigue, or distractibility Supervision fosters dual awareness attunement to both client and self and teaches therapists to convey presence through tone, posture, and expression. It also provides space to address alliance ruptures and integrate the mechanisms that enhance client safety and healing.

By embracing these recommendations, therapists can strengthen therapeutic relationships, foster a sense of emotional safety, and optimize the effectiveness of their work, whether in-person or online

Therapeutic presence is not merely a desirable quality, but a fundamental, trans-theoretical phenomenon essential for effective psychotherapy, regardless of the treatment modality It serves as a necessary precondition for cultivating psychological and emotional safety, strengthening the therapeutic relationship, and fostering the therapeutic alliance, all of which are paramount for client healing and growth. The ability of therapists to be fully present – grounded, open, spacious, and intentionally "with and for" the client – allows clients to feel truly "met" and understood, thereby downregulating their defenses and enabling deeper therapeutic work. While the core principles of therapeutic presence remain consistent, its cultivation and expression face unique challenges in the online environment, such as limitations in non- verbal communication, technological hurdles, and increased therapist fatigue and countertransference. However, intentional strategies discussed can bridge the physical distance, allowing therapists to communicate their presence effectively. The shift

towards teletherapy has highlighted an immediate and ongoing need for therapists to understand and cultivate presence in this modality

Counselor training programs are increasingly recognizing the need to integrate foundational instruction in therapeutic presence, encompassing not only the logistical and technological aspects of teletherapy but also the "inner work" of the therapist to remain grounded and attuned By doing so, mental health professionals can continue to offer profound healing experiences, ensuring clients feel emotionally and psychologically safe, even if separated by a computer screen The ongoing learning from navigating these challenges will ultimately enhance therapists' skills in developing presence and strengthening the therapeutic relationship.

References:

Feuerman, M L (2018) Therapeutic presence in Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy Journal of Experiential Psychotherapy, 21(3), 22–30.

Geller, S. (2020). Cultivating online therapeutic presence: Strengthening therapeutic relationships in teletherapy sessions. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1787348

Geller, S. M. (2013). Therapeutic presence as a foundation for relational depth. In R. Knox, D. Murphy, S. Wiggins, & M. Cooper (Eds.), Relational depth: New perspectives and developments (pp. 175–184). Palgrave.

Geller, S. M., & Porges, S. W. (2014). Therapeutic Presence: Neurophysiological Mechanisms Mediating Feeling Safe in Therapeutic Relationships Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 24(3), 178–192 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0037511

Written By: Marni Feuerman, MSW, PsyD, LCSW, LMFT

Dr. Feuerman is a licensed clinical social worker and marriage and family therapist in private practice in South Florida. She specializes in couples therapy and relationship problems and provides clinical supervision and consultation As an ICEEFT Certified Emotionally Focused Therapist and Supervisor, she uses a processexperiential approach centered on therapeutic presence Dr Feuerman is also a nationally recognized relationship expert, media contributor, accomplished author and freelance writer. Connect with her at www.DrMarniOnline.com.

Mental health and wellness have certainly become more widely accepted terms over the last few years. With the expanding acceptance that mental health is a necessary focus in our lives has come an increased need for care and care professionals. We’ve seen a dramatic increase in telehealth practices, residential facilities, individual private practices etc. But then that begs the question: Which level of care is right for our clients? Which avenue would best suit them? It seems to be a prerequisite for work in the mental health field that a provider has a strong desire to help others (and rightfully so) We all want to help our clients; but what if the level of care we offer isn’t the one with the most potential for improvement

I’ve been working in a hospital setting over the last three years in intensive outpatient programs (both PHP and IOP). We are often required to describe what Partial Hospitalization Program(s) and Intensive Outpatient Program(s) entail and what this level of care can address. If you aren’t familiar with these terms, which I wasn’t until I began work in this level of care, I can provide a brief description here Each individual program my vary slightly, but will follow the same general guidelines

Partial Hospitalization Programs are either a step down from inpatient mental health treatment/psychiatric hospitalization,

a step up from intensive outpatient level of care or a step up from standard outpatient level of care Although the term ‘hospitalization’ is in there and can cause some confusion, this is a voluntary outpatient level of care Clients come and go from their homes each day (unless your program offers PHP/IOP housing) and they are not forced to stay or engage Don’t worry, I can help describe those levels mentioned as step downs or step ups, too.

For our program, PHP is a five-day per week program that is group-focused and consists of five fifty-minute groups per day. Group modality is meant to help clients find empathy and relate to others, reintegrate healthy structure into their lives and to gain information about healthy coping strategies While group modality is amazing and I’ve studied the intricacies of how short and long-term groups can work throughout my professional career, I’d be doing everyone a disservice if I didn’t mention some of the limitations Mixed-gender groups for mixed mental health concerns (like depression, anxiety and psychotic symptoms which are more common than one might think!) should not be recommended for complex, specialized concerns. Specialized concerns like those related to trauma should be addressed through either individual care from a specialized professional or through a specialized group format.

Although PHP/IOP may seem long from the outside (we estimate about 3-4 weeks of PHP and 3-4 weeks of IOP for each client), it’s not long enough to open, organize, and resolve complex issues that may involve slight regressions or disruptive episodes before progression. Additionally, while the combination of groups, medication management and individual check ins can work wonders, it is not by any means a magic quick fix. Expectations should be set for clients and family members that, while we hope for the quickest turnaround possible, we can’t guarantee significant progress in any particular set amount of time. Mental health treatment is individualized and client progress/responsiveness may vary.

Through PHP, clients also receive medication management consultations frequently (we offer weekly) and are assigned to an individual program therapist for check-ins. This is a huge perk, as standard outpatient medication management typically occurs once per month or every other month. Weekly visits allows for close monitoring of medication efficacy and potential side-effects. Psychiatric medication management is offered from professionals who specialize in just that; psychiatric medication. Many clients, family-members or professionals may misconstrue the offer of medication management for overall physical health monitoring. This is not the case. While psychiatric medical professionals have knowledge in other health areas that allow them to make educated choices when prescribing medication, like if someone has a heart condition and a specific medication has a potential side effect related to heart-rate for example, all professionals are required to operate only within their scope of practice Psychiatric medical professions do not prescribe medication outside of psychiatric needs or side-effects from current psychiatric medication(s); just like therapists not prescribing medication or a podiatrist not assessing chest x-rays. While psychiatric medical professionals may request bloodwork, checks or scans to ensure safety in taking psychiatric medication, clients need to have primary health physicians or specialized doctors to provide care outside of psychiatry-specific concerns when involved in PHP/IOP.

For many of our clients at the PHP level of care, functioning has been impaired in the major areas used for diagnosis of a mental health disorder (work, school, relationships, self-care) and suicidal ideation may be present. In this case, safety plans should be in place and there should not be any genuine intent present in clients to act on suicidal ideation. We see clients in the PHP level of care who need help stabilizing their symptoms (anxiety, depression, panic, psychosis and substance abuse).

Intensive Outpatient level of care (IOP) is the lesser intense of

the two programs (I know the names try to fool you) This is also a voluntary outpatient level of care Intensive outpatient is a three-day per week program that is group-focused Number of groups per day may be dictated by insurance but generally three groups per day. Clients requiring this level of care need help with stabilization that hasn’t been addressed in standard outpatient level of care, or who are slowly weaning themselves off the level of support they received in PHP. Clients are assigned to an individual program therapist and medication management provider for less frequent check-ins than in PHP. Safety and overall functioning concerns are not as intense as PHP level of care would warrant, and medication changes are not being made as frequently (which may require increased supervision offered at higher levels of care)

Okay. So now we’ve gone over PHP/IOP levels of care…but these lay sandwiched between other options. It’s important we understand those other options because, even though we may wish we could help everyone, we want to make decisions for clients that are ethical and appropriate. As my boss likes to question, “if not us then who”? If we’re not it, what direction would yield highest therapeutic benefit?

We’ll start at the bottom, as I like to think about levels of care on a spectrum Standard outpatient level of care is what most people might think of when the term ‘therapy’ is used. Sessions are typically weekly or even bi-weekly and are intended to help the client(s) work through emotional struggles or history that bothers them past the point of working through it on their own, but not to the point where safety or functioning is a concern. Standard outpatient can be individual, family, couples, etc. Standard outpatient level of care is maintained as the client works through a particular issue(s) and should be terminated once the stated issue(s) have been resolved. Clients may utilize standard outpatient medication management providers (such as psychiatrists or psychiatric nurse practitioners) to receive prescription for medication that they can take on their own; following instructions for their regimen appropriately If functioning or ability to care for oneself becomes a concern, consider referring this client to a higher level of care That’s where intensive outpatient or partial hospitalization come in

Moving up the spectrum from PHP/IOP we find ourselves at residential treatment. Residential treatment, as the name states, provides housing and mental health treatment for their clients. This often includes a combination of group, individual and medication consult. You will find that residential treatment suits clients who struggle with independence or autonomy This may present itself as medication non-compliance or confusion, nonadherence to program rules/structure at the PHP/IOP level

of care or disruptive behavior that interrupts the success of others in group(s), etc Keep in mind this is not often a permanent option, as many residential treatment facilities offer time-limited support at this level before a client should attempt stepping down to a level of care that will help them transition back into a more autonomous life.

At the top of the spectrum is psychiatric hospitalization or inpatient level of care This isn’t as scary as old movies may depict Many modern inpatient facilities attempt to promote a therapeutic atmosphere The goal here is stabilization so that a client is more capable of engaging in lower levels of care on the spectrum Inpatient assessment will gauge whether the client is a danger to themselves or others, whether they have the current capacity to care for themselves and/or whether their symptoms are causing significant distress and disruption in their lives. To achieve stabilization, psychiatric medications are provided or adjusted to yield better results. Clients are removed from outside stressors and monitored consistently to ensure safety and progress. Inpatient level of care may be voluntary or involuntary depending on the client’s ability to recognize their deficits at the time. In Florida, our procedures outline that if a client engages in voluntary admission, they may state to their care team when they feel ready for discharge and their progress will be reviewed for final decision. If a client is admitted to inpatient involuntarily (a baker act here in Florida) it is completely up to the care team (ultimately the psychiatrist) to determine readiness for discharge A detailed discharge plan should be in place to ensure client success and follow-up

If your client isn’t benefitting from their current level of care, take the time to consider if a different level of care may suit them better. This consideration may happen during initial assessment, or after attempt to engage in treatment. Continuous assessment and case review is best practice to ensure we aren’t continuing to attempt a level of care that the client isn’t suited for at this time Think about working from the outside ends of the level-of-care spectrum inward; in other words if you start at standard outpatient level of care, try working up until you find the right fit If you’re starting at the top with inpatient level of care, work downward to slowly reintegrate important balance into your life

While most of this article has consisted of information to be considered from the professional’s standpoint, it would leave a big gap in our practice not to discuss client input. At the PHP/IOP level of care particularly, I’ve been met with the challenge of explaining the rationale for why a specific level of care is being recommended Clients may come in for assessment with an expectation or understanding of one level of care vs

another Resistance to interrupting certain aspects of their lives can feel scary, as well as being faced with revealing their struggles to family members or employment personnel to clear schedules and allow for three or five day per week treatment is a big ask. Remember, it is your job and responsibility as a mental health professional to steer your client in the direction of the best fit. It’s tempting to accept client pleas to engage in a lower level of care than is recommended; and in some cases something really is better than nothing. Just because a program is voluntary, doesn’t mean a client can engage as they please in whichever level of care they are willing.

I try to explain it to clients like this when I encounter resistance: Let’s say you’re experiencing pain in your arm after a fall You go to the doctor and they perform an x-ray revealing a broken bone. The doctor will recommend the appropriate level of care with the goal to mend the bone; likely a cast. You don’t want a cast, as it will get in the way of your work and you don’t want to have to explain it to peers so you tell the doctor that you’d rather just go with a bandaid. The doctor may refuse to move forward with that plan of care with the knowledge that it’s not safe and won’t mend the bone properly. It’s the same for mental health. It’s not wrong, it’s not illegal, it’s most ethical to refuse a level of care that is inappropriate for your client’s symptoms and may pose a safety risk.

It's a lot to take in. It’s a lot to consider. It’s continued process of learning and understanding as we work with clients and come to understand appropriate recommendations. Ultimately, we want our clients to live the happies, most independent lives they can. We want to help and, even when it feels counterintuitive, turning away a client for a more appropriate level of care can be the best way to offer help.

Written By: Jocelyn Patterson

Jocelyn currently works within intensive outpatient mental health programs in a hospital setting, offers individual telehealth sessions currently through Betterhelp, and has experience within forensic settings. Jocelyn has been working to offer continuing education courses online (keep an eye out for Paint Your Progress courses in the near future!) More of Jocelyn’s featured content and perspectives on professional development within the counseling field can be found on LinkedIn and/or professional social media accounts @paintyourprogress. Jocelyn has been working to promote art therapy and to introduce clients to communication using an alternative language of visuals

Food insecurity remains a troubling reality for many individuals, with an annual estimate of more than 47.4 million Americans, including 9 million children, according to the Food Research Action Center. (1) Food insecurity is a social determinant and is a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) distinctly categorizes food insecurity as:

Low food security: “Reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.”

Very low food security: “Reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” (2)

A Feeding America survey showed that 90% of responding food banks reported seeing either an increase or steady demand for food assistance in one month, August 2024, compared to July 2024 ( 3) There’s also an increase in food insecurity according to a USDA data report indicating 13.5% of households were experiencing it in 2023, up from 12.8% in 2022. This amounts to roughly 47 million people, including 14 million children.(4) SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, applications

are expected to increase due to recently proposed Federal legislative budget cuts to the Program. These proposed cuts include reductions in benefit levels and stricter work requirements, potentially impacting millions of people, likely widening food insecurity and financial hardship among lowincome individuals who rely on SNAP. (5) A household’s condition of being food insecure may be long term or temporary, is influenced by several factors. There does exist a correlation between food insecurity increasing when money to buy food is limited or unavailable. Food insecurity does not necessarily cause hunger, but hunger is a probable outcome of food insecurity (6 ) These findings lay the foundation of this article, to assist colleagues with recognizing childhood disordered eating correlates with exposure to traumatic life events, (7) presented as Food Maintenance Syndrome

A 2006 publication, by Tarren-Sweeney and Hazell investigated aberrant eating patterns in pre-adolescent children in foster care and kinship placements. The term Food Maintenance Syndrome was indicated as a specific “pattern of excessive eating, food acquisition, and hoarding without concurrent obesity”. ( 8 ) For this demographic, Food Maintenance

Syndrome seems to be a relatively recent area of specific focus to understand the broader problematic childhood eating behaviors, with its prevalence connecting to reports of abuse or neglect. However, this condition is considered atypical in children who are not in the foster care system, but its symptoms are being discussed among clinicians regarding children, absent of placement in the child welfare system, requiring behavioral health treatment for other primary conditions. These discoveries afford therapists insight to a child’s survivalist response to the absence of food.

The survivalist response creates an anxious attachment to food and an emotional preoccupation with food. The brain is set in survival mode, triggered by the fear that food may not be available in the future Research suggests that individuals with Food Maintenance Syndrome may have experienced years of food deprived cycles Therefore, early identification and intervention is needed to recognize disordered eating patterns Common signs of Food Maintenance Syndrome include, but may not be limited to:

Overeating to the point of feeling uncomfortably full and nauseous

Apparent lack of satiety (feeling satisfied)

Eating quickly

Becoming upset if someone eats from their plate

Stuffing food in the mouth

Hoarding and hiding food to eat later

Stealing food from stores or homes they visit

Refusal to throw away any leftover food

Only eating a specific amount of food

Purposely not eating enough ( 9)

Food Maintenance Syndrome is not currently recognized as a mental health disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5). However, children presenting with Food Maintenance Syndrome often have co-occurring disorders, because of abuse and trauma, such as:

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Anxiety disorder

Depression

Rumination disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder

If the trauma-driven onset of the eating behavior isn’t identified, Food Maintenance Syndrome can sometimes be misdiagnosed as an Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder (OSFED) or as obsessive-compulsive disorder. (10) Generally, disordered eating versus being diagnosed with a more severe eating disorder will focus on the duration of

symptoms, their frequency and severity of the disordered behaviors, and the effects on their physical health, including weight

Trauma is defined as “Any disturbing experience that results in significant fear, helplessness, dissociation, confusion, or other disruptive feelings intense enough to have a long-lasting negative effect on a person’s attitudes, behavior, and other aspects of functioning Traumatic events include those caused by human behavior (e g , rape, war, industrial accidents) as well as by nature (e g , earthquakes) and often challenge an individual’s view of the world as a just, safe, and predictable place any serious physical injury, such as a widespread burn or a blow to the head ”(11)

Each traumatic event, requires defining, according to findings in Epidemiology of Traumatic Experiences in Childhood. Estimates suggest that 46% of youth aged seventeen and under report experiencing at least one trauma including:

8-12% - sexual assault

9-19% - physical abuse by a caregiver or physical assault

9% - internet-assisted victimization

20-25% - a natural or man-made disaster

20%-48% - multiple types of victimization to multiple types of traumas

38-70% - witnessed serious community violence

Also, within this population, 1 in 10 have witnessed serious violence between caregivers and 1 in 5 has lost a family member or friend to homicide (12)

Children in foster care experience Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD, at a significantly higher rate than children not in foster care. Approximately, 15% of youth in foster care have PTSD, roughly twice the rate of 7% found in the general population. Some research suggests that up to 30% of children in foster care may meet the criteria for PTSD, while estimates between 6% and 15% of all children and adolescents exposed to trauma may develop PTSD PTSD presents with a higher prevalence in youth in foster care with a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD The Centers for Disease Control, CDC, reports an estimated 55% of children enter foster care for neglect, but they experience greater mental health diagnoses, such as AttentionDeficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) with rates ranging from 10% to 21%. ADHD prevalence rates is estimated at 3.4% for children in the general population. (13) Comparatively, PTSD is specifically linked to experiencing a traumatic event and involves symptoms like re-experiencing the trauma, avoidance, negative alterations in mood and cognition, and hyperarousal, while ADHD is characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity not necessarily related to trauma. (14) For example, a child with PTSD may appear inattentive due to being

preoccupied with intrusive memories and avoidance, while a child with ADHD may struggle to follow instructions due to distractibility

For those of us living along coastal communities the life-long, annual preparatory rituals for hurricane season, June 1 to November 30 , and its post-recovery, may provoke an awareness of how Food Maintenance Syndrome behavioral patterns develop over time Natural disasters can significantly contribute to trauma and anxiety, often leading to food insecurity, in altered communities The experience of a disaster can disrupt access to food, causing both immediate and longterm food insecurity Food Maintenance Syndrome assimilates both PTSD and ADHD and can present with overlapping symptoms like inattention, impulsivity, and difficulty regulating emotions, making differential diagnosis and treatment difficult. The symptomatology of comorbid diagnoses may be compounded, for all children, when they are exposed to environmental traumatic events. st th

Has a routine of anticipatory, “storm-watching”, hurricane preparation, exacerbated anxiety or stress, causing the mental re-visiting of previous hurricanes, and any of its associated negative aspects, such as food availability? Can the existing link between natural disasters and trauma manifest into Food Maintenance Syndrome, with each successive event, and subjection to food unavailability or rationing? Has repeated food insecurity and trauma exposure created a cycle of unsupported and/or untreated mental health issues? For intervention success, possessing an understanding of the etiology of the trauma-derived, Food Maintenance Syndrome, in an atypical population, is critical. In children six years and older, PTSD diagnostic criteria align with adults, requiring exposure to a traumatic event and experiencing specific symptoms, which must begin after the traumatic event, though they can emerge immediately or be delayed by up to six months. There are four categorized symptom clusters: intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and hyperarousal The DSM-5 has separate criteria, for children under six, with modifications addressing developmental differences (15) Traumatic experiences can leave historical reminders, persisting for years, setting in motion unexpected changes. For children not in foster care, identifying and assessing the anxiety responses to cumulative trauma: multiple traumatic experiences over time, or complex trauma: exposure to prolonged and repeated traumatic events, creates a more intricate clinical picture.

Being cognizant of how a child’s “normal” developmental stages are overwhelmed when impacted by community-wide

disruptions, such as accompanying caregivers in “hot meal” lines or receiving food in alternative settings, such as food banks, can be positive or negative behavioral reinforcers

Children progress with reactions to traumatic events slightly different for children of different ages. They may regress after a disaster, losing skills they previously acquired or return to behaviors they had outgrown. Physiological, emotional, and behavioral reactions in response to their environment and caregiver may change. Research consistently shows children experience severe reactions to stress following a natural disaster. Food and environmental attachment are intertwined across developmental stages to form secure and healthy social relationships. Positive experiences contribute to a child's sense of security and attachment Food insecurity and traumatic experiences can negatively impact a child's attachment and overall well-being ( 16)

Clinical Director, Dr. Shantrell Charles, noted her findings yield to the interrelatedness of trauma within specific aspects of a “child’s response to external stimuli and that stimuli will likely condition that child’s learned responses.” These conditioned responses can become hard-wired in the child’s brain and function automatically. After all, “the thought of not having access to a basic physiological need, food, would likely cause anyone to feel threatened, especially, if food vulnerability has been a regular occurrence ” Reprogramming the child’s emotional response about food access is essential Dr Charles emphasizes that the goal of foster care is temporary Children are to be reunified with their families, whenever possible Understanding family dynamics surrounding food security is a valuable tool when entering culturally sensitive discussions. A comprehensive interdisciplinary case plan is recommended as a goal prior to reunification, if food insecurity was factored in the child’s removal and if Food Maintenance Syndrome characteristics were observed, while in care, individually or in combination with other diagnoses. Finally, youth formerly in foster care will reintegrate into their communities, requiring the same level of support, or more, as non-foster care placed youth.

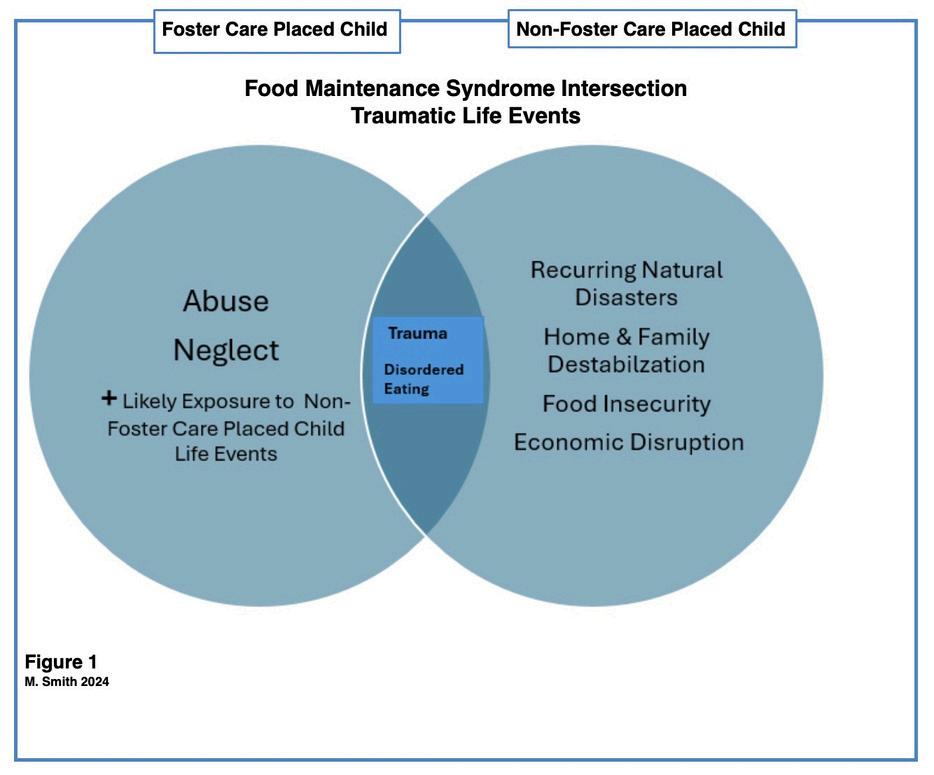

Figure 1 - Intersects possible environmental traumatic events between foster care placed children and children not in care, both having the clinical presentation of Food Maintenance Syndrome. Enhanced screening, early intervention, and targeted support services specifically designed to address the unique needs of children and adolescents appropriate to the child’s developmental stage are needed. (17) Awareness of the relationship between adverse childhood events and their correlation to trauma, benefits clinicians’ insight relative possible root causes of disordered eating.

Trauma-driven Food Maintenance Syndrome sets a child’s brain in survival mode. The clinical observation of children eating excessively, sometimes to the point of being painfully full, and hoarding food, as if their access to food will be unpredictable, can manifest physically and behaviorally, not only in care settings, but in school, impacting academic performance.

School administrator, Toshei Woods, recognized incidents surrounding ongoing student cafeteria behaviors, such as food stashing, reducing food intake, and/or asking peers for food. A voluntary, visually and emotionally-comforting “snack exchange”, non-discard, judgment-free, area for unopened food items was established. The one-to-one ratio, give-one and take one, exchange for non-preferred food items, minimized

reported behaviors of peers feeling “bullied” into giving away their food, reduced the daily banter with cafeteria staff, expressing what they “didn’t like” or “want” on their tray, and gave access to extra food during scheduled breaktimes By using data informed decision-making to further stabilize the emotional and physical feelings of student satiety, throughout the day, broader support strategies were implemented, including the following instructional enhancements:

The school enrolled in the weekend Feeding America Backpack Program (18) and incorporated items from the snack exchange.

Modifications were made to student questionnaires to identify traumatic experiences and symptomology (19) Home room meetings included reading of the daily lunch menu

A food-embracing cultural shift was cultivated centering

around students’ needs Other embedded shifts were in horticulture and cooking classes, using student-created menus and health education about farm-to-table food resources Art classes included more food/still-life images with daily journal reflection. Overall, strategies prevented disruptive, escalating, unwelcome behaviors promoting healing and a positive school environment.

Childhood trauma encompasses a range of adverse experiences, including natural disasters which can have a profound and lasting effect restructuring life-long behaviors and create disordered thinking and eating patterns Pinpointing signs and effects of trauma such as behavioral changes, nervous system dysregulation, and difficulty trusting others, is essential in providing therapeutic techniques such as Cognitive Behavior Therapies: Exposure and Response Prevention, Narrative Exposure, in mitigating the impact of trauma and promote recovery. Applying Measurement-Informed Care (20) to transdiagnostic functionality across cognitive, affective, and interpersonal mechanisms connects trauma exposure to specific disordered eating symptoms to structure prevention techniques. In many communities, reliable access to adequate, nutritious food, leaning into food insecurity requires fortifying protective factors. Even in homes where adequate food is available, the fear of future deprivation remains, proportional or exceeding, in disaster-exposed children, forever shaping their psychology about food Food Maintenance Syndrome isn’t just a condition of disordered eating or hunger, it’s a multifaceted issue with far-reaching consequences for social determinants of health

General Considerations:

Challenge the origin of and resolve one’s own personal beliefs about food

Be receptive to professional guidance once disordered eating is identified

Refrain from dismissing disordered eating cues

Seek to dispel negative, judgmental conversations about food, i.e., the amount to eat, cleaning the plate, using food

as punishment, or other food bargaining acts

Intervene early in settings where the behavior occurs and identify professionals to cross train with care givers/providers

Make food available at regular intervals

Observe and record patterns of food related behaviors, such as time of day and across settings

Utilize brief diverse trauma screeners, at specific intervals When visiting alternative food sources, at any time, openly communicate about the reason(s)

Consider further research on Food Maintenance Syndrome to build additional qualifiable and quantifiable interventions advancing Measurement-informed Care practices

Written By: Marie Smith, Ph.D., NCC, LPC-S, LMHC, CFMHE; Shantrell Charles, DSW, LMSW and Toshei Woods, M.Ed.

Dr Marie Smith has administrative and supervisory experience in clinical, detention: juvenile and adult, K-12 and higher education settings. Her work encompasses advocacy and effective mental health treatment through research and practice.

Dr Shantrell Charles supervises, as the Principal Clinical Director, the administration of a state-wide foster care program. She has extensive practitioner, clinical and administrative/ supervisory experience across child welfare programs and policy development in state government and in the private sector.

Toshei Woods is a social sciences educational administrator and licensed nutritionist. Her work integrates community education with health condition management through whole food choices and life-style behavioral changes.

Through FMHCA’s Local Chapters A CONVERSATION WITH GRACE CANTOR

FMHCA’s mission is clear: to get closer to members’ hometowns through local chapters, creating meaningful connections that strengthen the counseling profession at every level At the heart of this effort is Grace Cantor, FMHCA’s Northeast Regional Director and Co-Chair of the Chapter Relations Committee.

Grace is a licensed mental health counselor in Florida and Washington, a licensed professional counselor in Oregon, and a qualified supervisor in Florida She is a Certified EMDR therapist and an EMDRIA-approved Consultant-in-Training with over 15 years of experience in the mental health field Grace specializes in trauma therapy, anxiety-related disorders, and couples counseling, and has maintained a private practice for the past decade She has also worked in community mental health, inpatient psychiatric care, and provided international supervision to counselors and trainees in Egypt and Ukraine. Currently a third-year doctoral student in the Counselor Education and Supervision PhD program at Regent University, Grace brings both clinical depth and leadership experience to her work with FMHCA, where she advocates for counselors and fosters professional community across the state.

From Regional Director to Chapter Relations Chair

For Grace, stepping into the role of Chapter Relations Committee Chair feels like a natural extension of her service as Northeast Regional Director. “Serving in that position, collaboration was always my goal,” she shares. “There is so much knowledge and wisdom in our chapters, and I want to use that to support new chapters or help smaller ones grow.”

Her experience has also highlighted the importance of teamwork. “Recruiting is essential, no one can do this alone,” she says. “And building relationships is just as important. Our profession can be isolating, and chapters give us a way to connect meaningfully with one another.”

Grace knows firsthand the value of local support. After moving from Portland, Oregon, to Jacksonville, Florida, she struggled to find her footing professionally. “The chapter in Jacksonville had dissolved around COVID, and that was hard. But now there is momentum to re-establish it, and I want to make sure counselors have the support they need to do this heavy work.”

Local chapters, she explains, bring connection to life “It is about facetime, being able to see each other regularly at CEs or networking events That builds relationships, referral networks, and support systems. It also makes it easier to step into statelevel involvement. When you already know someone locally, it is less intimidating to get involved.”

She recalls a recent event in Jacksonville that reenergized the

local counseling community “We had interns seeking licensure who did not even know about FMHCA After one networking event, they felt excited to have support, and that energy helped drive momentum to reform the chapter. But events like that do not happen alone. It took our staff, generous sponsorship from Sophros, and a lot of collaboration. The gratitude we received showed just how much people needed it.”

Grace emphasizes that engagement at the local, state, and national levels is what truly builds a united profession. “At the local level, we can better understand community needs,” she explains “The more connected we are locally, the more momentum we have at the state level And at the state level, FMHCA has a stronger voice for advocacy ”

That local-to-state alignment strengthens FMHCA’s statewide goals. “There is strength in numbers. The stronger our chapters are, the stronger our footprint is at the state level.”

On the national scale, membership with AMHCA creates an even broader impact “FMHCA does amazing work at the state level Honestly, I have lived in other states where there was not anything like it By being strong here, we can serve as a role model for others, while also contributing to the national effort. It extends our reach and ensures our profession has a united front.”

She sees the relationship between these three levels as reciprocal. “The more connected I am locally, the more motivated others are to engage at higher levels And in turn, what we learn nationally and statewide helps us better serve locally It is a cycle of growth and support ”

FMHCA’s current theme of unity resonates deeply with Grace “Burnout is common in our profession, and community is a protective factor If you are interested, there is a place for you There are so many spaces to get involved, and the more connected you are, the more supported you will feel ”

Looking ahead, she sees the Chapter Relations Committee as a hub for collaboration. “There is incredible passion and wisdom in our chapters. By sharing resources and structures, we can help establish new chapters and strengthen existing ones. The generosity of our chapters is what will make this work possible.” What excites her most is the momentum. “There is such a need for counselors in our communities, and our members are passionate about serving By working together, we can build resilience and a robust support system that serves counselors, chapters, and the communities we dedicate ourselves to ”

Professional Experience Article

Social exclusion is a normative yet painful developmental experience that arises as children navigate shifting peer groups, academic transitions, and differing levels of maturity. Events such as birthdays, holidays, athletic competitions, or school performances and achievements, often highlight exclusion most acutely. For many children, these moments activate feelings of rejection and diminished self-worth, placing parents in the position of primary support providers outside the clinical setting.

Parental responses that emphasize validation, containment, and perspective-taking are most effective in mitigating distress and fostering resilience. Within my practice, Social Sense Palm Beach, parents appreciated having these tools outlined for reference when challenging social scenarios arise for their children.

Six core strategies are outlined:

Validation of Affect: Acknowledge the child’s emotional experience directly (e g , “I can see this feels disappointing”) Normalizing distress fosters affect regulation and actively prevents internalization of shame

Reflective Listening: Allow space for narrative processing before offering solutions. Reflective statements provide containment and respect the child’s developmental need for agency. Premature problem-solving can undermine selfefficacy.

Cognitive Reframing: Reframe exclusion as situational rather than identity-defining. Clarifying that social events are often constrained by size, circumstance, or shifting dynamics helps reduce globalized negative self-appraisals. Coping and Confidence Building: Encourage adaptive

self-talk, participation in meaningful activities, and engagement with affirming peers Such strategies broaden social identity and build resilience.

Modeling Adaptive Responses: Age-appropriate disclosure by parents of their own experiences with exclusion communicates universality and demonstrates coping pathways. Modeling enhances observational learning and reduces isolation

Perspective Maintenance: Differentiate between situational exclusion (e g , small gatherings, family-only events) and recurrent patterns warranting further assessment. Persistent exclusion may indicate broader social skill challenges or systemic peer dynamics requiring school collaboration.

Elementary School (6–10 years): Characterized by concrete, dichotomous thinking Exclusion may be perceived as global rejection (“I have no friends”). Supportive reassurance and redirection to prosocial outlets are indicated

Middle School (11–13 years): Heightened self-consciousness and peer orientation amplify the impact of exclusion. Open dialogue and collaborative coping strategies help mitigate internalized rejection.

High School (14–18 years): Exclusion is often equated with diminished worth Joint problem-solving, reframing, and encouragement to broaden social networks are protective. Social exclusion is an expected developmental challenge but can be buffered by parental strategies that prioritize validation, reflection, and resilience-building. When exclusion becomes patterned or pervasive, collaboration with educators or mental health professionals may be warranted

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and socialpsychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–722.

Masten, A. S., & Coatsworth, J. D. (1998). The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. American Psychologist, 53(2), 205–220. Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Written

By: Hayley Schapiro, LCSW

Hayley has over a decade of experience in nonprofits, hospitals, & schools, specializing in CBT. She founded the South Florida Mental Health Network to expand access & connect clients with trusted professionals She also consults with schools on student mental health, crisis response, parent education, & policy

Professional Experience Article

It starts before I even get into the car. My mind runs through possibilities. What if a tire blows out? What if the engine fails in the middle of an intersection? What if my brakes go out? What if someone swerves into my lane, and I can’t get out of the way? These aren’t just anxious thoughts They’re parts of me They show up with urgency and intensity because they believe they’re keeping me alive and safe.

IFS (Internal Family Systems) taught me to recognize that we all have many parts inside us, like a little inner family. Let me tell you, my “inner driving crew” has some strong personalities There’s the hypervigilant part, constantly scanning for danger, gripping the wheel like it’s holding me to Earth. There’s the control freak part, unwilling to let someone else drive, because that feels like asking for an accident to happen. There’s the inner critic who is telling me to pull myself together and stop worrying so much. Underneath all my protective parts, there’s a softer, quieter part, an exiled young girl, curled in on herself. She feels there’s too much happening at once, too many chances for everything to fall apart in a split second. She feels so helpless and so small she could disappear between the cracks in the seat.

She doesn’t trust the other drivers on the road, but she also doesn’t trust me. The little girl holds on to every memory in which no one came, no one comforted her. In her world, help never arrives, and when she needs someone the most, she was and will be alone.

And here’s the thing: these parts of mine don’t just bring thoughts, they also bring physical sensations. When my protective parts take over, I feel it in my body: the sweaty palms, the racing heart, the tight jaw, the jittery legs. That’s not just anxiety; it’s all my parts reacting to danger to keep the vulnerable little girl alive and alert. They remember every moment of danger, real or perceived. They remember the shaking, the bracing, the frozen moments of “what if?” from the past. Therefore, when something feels remotely similar, they send the same signals. They don’t believe they are overreacting, and they are desperately trying to protect me with the only tools they’ve ever known

Before I understood IFS, I used to fight these parts. I’d get annoyed at myself: “Why are you being so dramatic?” “Just drive. Nothing’s going to happen.” But it never worked. It only

made the fear louder because these parts weren’t being heard They were being pushed aside like screaming toddlers ignored in the backseat

Now, when those fears come up, I do something different. I pause. I breathe. I check in. I might say (silently, but sincerely): “Hey, I know you’re scared. You’ve seen some things. You’ve been through a lot. You’re doing your best to protect me. I’ve got us now ”

That moment of kindness, of not shaming or rushing, changes everything. When I stop trying to shut them up and start trying to understand them, my parts soften. They don’t vanish, but they settle. They stop screaming and start listening. Just like real kids, they calm down when they know they’re safe and someone is paying attention and tending to them.

I’m a therapist, but I’m also a person with fears, trauma, and protective parts that can go into overdrive I know what it’s like to feel that surge when the world suddenly seems uncertain or unsafe.

That’s why I love IFS. It doesn’t pathologize our fear. It doesn’t rush us to “get over it.” It invites us to get curious, to relate instead of resist. It reminds us that healing doesn’t come from

silencing our parts but from welcoming them from within

We all have fears, maybe not about driving, but about love, parenting, success, failure, or simply being seen. IFS gives us a gentle roadmap to explore those fears, not by fighting them, but by understanding why they’re there in the first place.

You don’t have to kick your fear out of the car You just don’t have to let it drive

Written By: Jessica Sahoury, LMFTA

Jessica Sahoury is a Marriage and Family Therapist Associate licensed in Indiana and a registered MFT Intern in Florida. She provides clinical services to couples, adolescents, and individuals, with a focus on relatio health and emotional well-being. Her therapeutic approach is integrative, drawing from Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT), Internal Family Systems (IFS), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and attachment theory to facilitate insight, strengthen relationships, and promote lasting change. She currently works at Mosaic Counseling Services.

Instructions:

1 Tbsp. neutral oil

1 medium yellow onion, chopped

1 jalapeño, seeded, finely chopped

2 cloves garlic, finely chopped

1 tsp. dried oregano

1 tsp. ground cumin

3 boneless, skinless chicken breasts, cut into thirds

5 cups low-sodium chicken broth

2 (4 5-oz ) cans green chiles

Kosher salt

Freshly ground black pepper

2 (15-oz.) cans white beans, drained, rinsed

1 1/2 cups frozen corn

1/2 cup sour cream

1 avocado, thinly sliced, for serving 1/4 cup chopped fresh cilantro, for serving 1/4 cup crushed tortilla chips, for serving 1/4 cup shredded Monterey Jack, for serving

Step 1: In a large pot over medium heat, heat oil Add onion and jalapeño and cook, stirring, until softened, about 8 minutes Add garlic, oregano, and cumin and cook, stirring, until fragrant, about 1 minute. Add chicken, broth, and chiles; season with salt and pepper. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer, uncovered, until chicken is cooked through, 10 to 12 minutes. Transfer chicken to a plate and shred with 2 forks.

Step 2: Add beans to pot and bring to a simmer Cook, smashing about one-quarter of beans with a wooden spoon, until slightly thickened, about 10 minutes Add corn and shredded chicken and cook, stirring, until heated through, about 1 minute more. Remove from heat and stir in sour cream.

Step 3: Ladle chili into bowls. Top with avocado, cilantro, chips, and cheese.

This holiday season, discover flavors of the world like never before through candy! As you count down to Christmas, savor 4 sweet treats from a different country each day (totaling nearly 100 snacks talk about a gift that keeps on giving). Each calendar also includes an informational booklet about the goodies and a sheet to rank your favorites as you eat your way across the globe.

Golden light filters through your window, a mug of something pumpkin-spicy sits within arm’s reach, and the air smells just a little like woodsmoke. It’s the kind of afternoon that calls for quiet creativity like the kind you'll find with this all-in-one watercolor set. It brings the comforting charm of autumn straight to your table, with everything you need to unwind and paint the season in your own colors, whether you're a practiced painter or just looking for a cozy moment of calm. Perfect for all ages and skill levels no prior drawing or watercolor experience needed.

Some nights call for just one more chapter This bibliophile’s sidekick is ready to keep the story going with glowing eyes that illuminate your page Best of all, it marks your spot when you're ready to call it quits or when you fall asleep midsentence. We’ve been there too.

What's even better than a supersoft, oversized hoodie? One that has a slumber-friendly eye mask built right into it. This clever pullover lets you go from airport hustle to in-flight nap with total ease, while enjoying a relaxed fit and cozy cotton blend It's just the thing for savvy travelers, weekend wanderers, and anyone who likes their comfort carry-on ready

What's even better than a supersoft, oversized hoodie? One that has a slumber-friendly eye mask built right into it. This clever pullover lets you go from airport hustle to in-flight nap with total ease, while enjoying a relaxed fit and cozy cotton blend. It's just the thing for savvy travelers, weekend wanderers, and anyone who likes their comfort carry-on ready.

Sure, it's colorful enough to catch the eye, but it's absolutely captivating once you get it in your hands Experience tactile fidgeting delight with this mesmerizing ellipsoid, crafted for quiet, engaging play. Its dynamic ability to stretch, collapse, and flex offers an immersive sensory experience that won't disrupt your surroundings. Whether you need a break from stress or a focus-enhancing fidget, this compact marvel promises endless fascination.

Posting your latest group selfie is great for likes, but nothing beats physical photos for hanging and decorating. This pocket-sized, inkless printer connects to your smartphone via Bluetooth®, then shoots out IRL pics to share.