LIFE BELOW WATER

FROM THE DEPTHS TO THE COASTLINES: FIU IS PROVIDING THE SCIENCE TO ENSURE OCEANS REMAIN HEALTHY

Oceans not only cover more than 70 percent of the Earth’s surface, they sustain us. Home to a vast array of life, oceans produce a significant portion of Earth’s oxygen, buffer our climate and contain a wealth of natural resources that people rely on in so many ways. They are a source of inspiration and beauty. But oceans — and the species in them — are at risk. At Florida International University, we work tirelessly in our backyard and around the world — in the field, lab and communities — to help protect and restore species and ecosystems while we ensure resilient communities. In recognition of these efforts, FIU has ranked No. 3 in the world for positive impact on Life Below Water, recognizing all of our work on behalf of oceans, marine life and the systems they support. This 2024 ranking, by Times Higher Education, is based on a series of criteria set forth in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Across all 17 SDGs, FIU ranked among the best in the world (13th) for overall impact, which includes working to improve Life on Land, Sustainable Cities and Communities, Clean Water and Sanitation and more — but those are topics for another magazine.

Our consistent top-tier ranking isn’t just a number — it’s a recognition of the unwavering commitment of our faculty, students, staff and collaborators. It is a testament to what we do with what we learn. Researchers in our Institute of Environment are helping restore ecosystems, combatting illegal wildlife trafficking and successfully supporting international protections for sharks and rays. They are identifying solutions for sustainable fishing and working collaboratively to improve water quality for nature and people. They are engaged in exciting exploration from the deepest depths of our oceans to the mangroves and seagrasses that line our coastlines. And they are inspiring people around the world, including through our underwater habitat at the Medina Aquarius Program. You will learn about this work and more in this issue of Life Below Water at FIU.

As we share these inspiring stories, I want to assure you that sustainability remains at the forefront of our efforts, including the production of this publication. The magazine is printed with all sustainably sourced materials and produced using energy-efficient equipment. If you would like to share our stories with others, you can find our digital issue with the QR code on this page.

Looking ahead, we are energized and inspired by what’s to come. Our researchers are establishing a nursery for endangered corals, expanding our cutting-edge robotics and autonomous vessels program, working to facilitate the development of large marine-protected areas (helping the world hit its goal of protecting 30 percent of oceans by 2030), and embarking on an ambitious mission to build Aquarius II, a new generation of underwater habitat that will push the boundaries of marine research. I hope to explore these exciting new endeavors with you soon as we continue to do work that makes a difference. Thank you for your continued support as we strive to create an inspiring and more sustainable future for all.

Sincerely,

Mike Heithaus

FIU Vice Provost of Environmental Resilience and Biscayne Bay Campus

Executive Dean of the College of Arts, Sciences & Education

Professor of Biological Sciences

FIU LIFE BELOW WATER MAGAZINE

FIU RANKS NO. 3 IN THE WORLD FOR IMPACT ON LIFE BELOW WATER

By Ayleen Barbel Fattal

FIU IS RANKED NO. 13 IN THE WORLD ACROSS ALL AREAS FOR OVERALL IMPACT, ACCORDING TO THE TIMES HIGHER EDUCATION IMPACT RANKINGS 2024.

FIU has been ranked the No. 3 university in the world for having a positive impact on Life Below Water by The Times Higher Education 2024 Impact Rankings.

Faculty, students and staff work across disciplines on ocean-related research, education and conservation throughout the world. The Institute of Environment is leading projects that support and safeguard the survival of key ecosystems and species in both freshwater and saltwater environments. Researchers are addressing sea level rise, management strategies for sustainable fisheries, and providing the science to ensure marine animals, aquatic plants, coral reefs, and their ecosystems remain healthy.

“Our globally recognized research programs develop realistic and scalable solutions to the environmental challenges we face today and are the scientific foundation for preventing future ones,” said Mike Heithaus, executive dean of the College of Arts, Sciences & Education and FIU vice provost of Environmental Resilience.

FIU is Florida’s University of Distinction in Environmental Resilience and prioritizes a healthy, sustainable planet through scientific investigations that support Life Below Water. With a ridge-toreef approach, FIU conducts research on every continent and in every ocean, collaborating with partners locally and internationally. Efforts have led to significant policy changes to enhance conservation, expand protections for endangered species, improve sanitation and access to clean water in developing nations, and improve protections for natural resources.

In the field, scientists are studying animal behavior, overfishing, habitat protection, ocean acidification, pollution and ways to protect seagrasses, one of the world’s greatest assets for storing carbon. To do their work, research teams develop and deploy

cutting-edge technologies including animalborne cameras, baited remote underwater video, satellite tags, biosensors, customized sonar and autonomous vessels.

FIU marine scientists collaborate on some of the most ambitious multi-institution research initiatives in the world including the Northwest Passage Project, exploration of the ocean’s twilight zone, and investigations into the scattering layers that account for the largest animal migration on the planet. They contribute to the National Science Foundation’s Assembling the Tree of Life project, using genetics to uncover the evolutionary history of crabs, shrimps and lobsters. And they are using science to disrupt illegal wildlife trafficking.

FIU is the main research partner for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and a research partner with Rookery Bay Research Reserve. FIU is also home to the Medina Aquarius Program featuring FIU Aquarius, the world’s only underwater research laboratory.

The Times Higher Education Impact Rankings assess universities against the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals across the areas of research, outreach and stewardship. n

FIU LIFE BELOW WATER

FIU TEAMS UP WITH WORLD-RENOWNED MARINE CONSERVATIONIST TO SPOTLIGHT SOUTH FLORIDA’S COASTAL ECOSYSTEMS

The coastal area around South Florida that stretches from Biscayne Bay through the Florida Keys and Florida Bay to the Ten Thousand Islands has been designated a Hope Spot by Mission Blue, an organization founded by world-renowned marine conservationist Sylvia Earle.

Hope Spots are special places identified as critical to the health of oceans. The new South Florida Hope Spot was championed by: Mireya Mayor, executive director of strategic projects; Mike Heithaus, marine ecologist, executive dean of the FIU College of Arts, Sciences & Education and vice provost of environmental resilience; and Heather Bracken-Grissom, marine scientist and assistant director of the Coastlines and Oceans Division in FIU’s Institute of Environment.

The new Hope Spot bridges the previously designated Hope Spots of Florida Gulf Coast and Coastal Southeast Florida, highlighting hundreds of miles of coastline between Martin County on the east and Apalachicola Bay on Florida’s west coast.

WATCH: HOPE SPOT

Scientists hope stress can lead to RESILIENT CORALS

By Angela Nicoletti

Serena Hackerott is giving coral researchers a much-needed beacon of hope for the future of coral restoration and conservation.

Hackerott, who conducted the research as a Ph.D. candidate in Professor Jose EirinLopez’s Environmental Epigenetics Lab, has created a comprehensive collection of all the research to date on environmental memory and stress hardening in corals. The effort is designed to inform future work that could lead to successful coral restoration.

Coral stress memory is a relatively new, but very promising finding. It suggests corals can remember environmental changes — like

marine heatwaves that cause coral bleaching — and that memory can build their resilience and help prepare them for similar events in the future.

However, there’s one problem — exactly how this phenomenon works in corals is still unknown. As Hackerott points out, it’s something scientists need to know before they try to implement stress hardening techniques on coral.

Coral stress hardening was introduced a few years ago as a possible strategy to save corals. It involves pre-exposing corals to stress, like higher temperatures, in a lab

before returning them to the ocean. The concept is similar to the way stress hardening is used to make seeds hardier in agriculture.

Hackerott, who graduated in 2024, and Eirin-Lopez wanted to figure out how to make this work for corals. The first step was gathering and reviewing as many studies on environmental memory and stress hardening that they could.

In some cases, corals survive a heatwave and retain knowledge of the stress for a few years, and it helps them better resist the next heatwave. Then, there are examples where a heatwave is too much to handle,

and instead of strengthening the coral, the stress becomes detrimental. The difference could be a matter of degrees. It’s a delicate balance. Scientists need to do more studies to find the sweet spot.

The good news is technology could provide a closer look at what’s happening to corals at the molecular level. Environmental epigenetics, for example — which is

the focus of Eirin-Lopez’s research — is a promising starting point. Epigenetic modifications are often involved in regulating stress memory within other organisms, like plants, and the Eirin-Lopez lab has been pioneering epigenetic research in corals.

The work was funded by an NSF grant and published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution. n

CORAL STRESS RESEARCH RECEIVES SUPPORT FROM FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

Researchers from FIU and the University of British Columbia have received a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration grant to advance their research into coral resilience.

Serene Hackerott, who earned her Ph.D. at FIU in 2024, and FIU Professor Jose Eiring-Lopez’s Environmental Epigenetics Lab, leads part of the project at Carysfort Reef in the Florida Keys. The project is part of her research to test how stress hardening might enhance stress tolerance for corals. The $273,491 grant is funded through NOAA’s Ruth Gates Coral Restoration Innovation Grant.

The Coral Restoration Foundation has provided support through the donation of 900 fragments of coral from Tavernier Nursery for lab and field work, as well as six days of boat trips to harvest, outplant and monitor the coral fragments.

“OUR HYPOTHESIS IS THAT HARDENED CORALS WILL BE BETTER AT SURVIVING IN CURRENT AND FUTURE CLIMATE CONDITIONS.”

— JOSE EIRIN-LOPEZ, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES PROFESSOR

Photo courtesy of Serena Hackerott

Photo courtesy of Richard M Howard

Plant-eaters pose threat in ecosystem balance GNAW MORE SEAGRASS?

By JoAnn C. Adkins

Photo by Shane Gross

There’s a hidden threat looming among subtropical seagrass meadows — turtles in search of milder temperatures.

Herbivores that feed on a steady diet of seagrass need lots of it to survive. These herbivores like to reside in warm climates. As ocean waters warm, many are expanding their ranges and heading poleward, occupying waters that were previously too cold. This is bad news for

subtropical regions, where seagrasses are less resilient and herbivores are scarce.

The findings reveal a troubling trend: Because subtropical seagrass meadows receive less sunlight relative to their tropical counterparts, they do not grow back as quickly when they are grazed upon. If tropical herbivores move into subtropical waters, overgrazing could become a serious threat.

Overgrazing is not yet a widespread occurrence across the Western Atlantic, but FIU marine biologist Justin Campbell said it’s already happening in subtropical to temperate waters surrounding Australia and in the Mediterranean. The findings represent the profound impacts warming waters can have to throw underwater ecosystems completely off balance. Funding for the study was provided by the National Science Foundation. n

AGGRESSIVE SEAGRASS SPECIES DISCOVERED IN BISCAYNE

BAY

An invasive species of seagrass has been on a steady march, taking over ecosystems beyond the Red Sea, Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. Scientists have long wondered when it would reach the waters off the coast of Florida. FIU Institute of Environment scientists say that day has arrived.

Justin Campbell has identified Halophila stipulacea growing in Biscayne Bay. It is the first time this non-native species has been found in waters along the continental United States.

Healthy seagrass meadows are vital for healthy oceans. They are nursery habitats for important fish and marine invertebrates. Seagrasses are a primary food source for sea turtles, manatees and other marine herbivores. And for the health of the planet, seagrasses suck carbon emissions out of the air and store that carbon long-term. While scientists are still working to understand possible impacts from the invasive species entering waters around the U.S., early research suggests some fish species may avoid the shorter seagrass when scouting nursery locations. Also, local sea turtles in the Caribbean have avoided eating the invasive seagrass, preferring native species.

WHILE SUBTROPICAL SEAGRASSES ARE LESS RESILIENT THAN THEIR TROPICAL COUNTERPARTS, FIU SCIENTISTS HAVE DISCOVERED AN INTERESTING INDICATOR OF RESILIENCE – CARBS! JUST LIKE PEOPLE, SEAGRASSES THAT ARE PACKING IN CARBOHYDRATES GROW AND THRIVE EVEN AS THEY ARE DEVOURED BY HERBIVORES. MAYBE CARBS AREN’T SO BAD AFTER ALL.

WHERE’S THE SEAGRASS? MANATEES RESORT TO EATING MORE ALGAE

By Christine Fernandez

Manatees resorted to eating staggering amounts of algae after seagrasses died off in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, according to the latest research.

FIU Institute of Environment Ph.D. candidate Aarin-Conrad Allen and a team of researchers including FIU Associate Professor Jeremy Kiszka have found the first evidence that Florida manatees went from primarily eating seagrasses to primarily eating algae after a 2011 harmful algal bloom decimated local seagrasses. Researchers made the discovery by comparing stomach contents of manatees living in the Indian River Lagoon during the late 1970s and 1980s to manatees living there between 2013 and 2015.

The Indian River Lagoon is a critically important habitat for manatees. Once abundant with seagrass, there are ever-increasing and more common algal blooms. In 2011, massive amounts of seagrass died, causing cascading effects. Many manatees starved. Some died. In 2021, Florida lost a record 1,100 manatees and more have perished since.

Allen examined 103 stomach samples collected by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation from manatees that had

died for unknown reasons between 2013 and 2015. Their diet contained almost 50 percent algae and 34 percent seagrass. He compared this to archival samples from 1977 – 1989, when the lagoon was healthier. The manatees’ diets were only 28 percent algae and as much as 62 percent seagrass. The manatees’ remaining diets were made up of other aquatic plants, invertebrates and other food sources.

This research presents more questions that need to be answered. Allen is investigating how much seagrass is left in the Indian River Lagoon. He is also measuring and comparing the nutritional value of algae versus seagrass, particularly to understand if algae is synonymous with “junk food” for these large herbivores.

With algal blooms becoming more prevalent, one thing is clear — manatees will have to respond somehow, by either leaving the Indian River Lagoon to find food elsewhere or perhaps stay and continue to feed on algae even if it doesn’t meet their nutritional needs.

The findings also have implications for other similar ecosystems like Miami’s Biscayne Bay where Kiszka is studying manatees and dolphins. n

The world’s most endangered whale is a picky eater. Their meal of choice is an abundant little schooling fish, and scientists say, though common, this fish must be considered as part of conservation strategies for the critically endangered whale.

Found exclusively in the Gulf of Mexico, Rice’s whales are a newly discovered species once believed to be a subspecies of the more geographically diverse Bryde’s whale. It was not long ago when scientists announced, after examining genetic and anatomical evidence, that the Gulf whales are actually their own distinct species. It is believed only 50 Rice’s whales remain and they primarily dine on Ariomma bondi, more commonly called silver-rag driftfish, according to new research led by FIU. Identifying their primary prey is an important first step in accelerating conservation for this newly identified species, according to FIU marine scientist Jeremy Kiszka, lead author of the research. He says even though their primary prey is abundant today, that could easily change in a region so heavily impacted by people and industrial activity.

NEWLY IDENTIFIED WHALE’S FAVORED PREY IS NOT ENDANGERED ,

BUT THE WHALE IS

By JoAnn C. Adkins

“Rice’s whales need high-quality food, which might make them more vulnerable to environmental changes and fisheries impacts,” Kiszka said. “Being specialized makes you more vulnerable, particularly if your preferred prey experiences decline.”

Rice’s whales engage in deep dives to forage for food, an effort that requires a lot of energy. While silver-rag driftfish were not the only fish found in the Rice’s whales’ diet, they were the primary prey. The small fish have a high caloric content, which can give the whales more energy. They also swim in large schools, making them an easier target. Either of these factors, or perhaps both, make them an ideal meal for the whales.

Published in Scientific Reports, the research began in 2017, which means the team was

unaware of the species distinction that was revealed in 2021. Finding out the whales in the Gulf were actually a new species to science only served to intensify Kiszka’s interests in the large marine mammal.

He plans to continue to research the Rice’s whales and help improve scientific knowledge of the species in an effort to save the species from extinction.

In addition to Kiszka, the research team also included Mike Heithaus from FIU; Michelle Caputo from Rhodes University in South Africa; Johanna Vollenweider from Auke Bay Laboratories in Alaska; Laura Aichinger Dias from NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the University of Miami; and Lance Garrison from NMFS. n

Silver-rag driftfish

Photo courtesy of NOAA

SETTING

NETS BELOW THE SURFACE SIGNIFICANTLY REDUCES UNINTENDED BYCATCH OF DOLPHINS, WHALES

By Chrystian Tejedor

Lowering gillnets into the water — instead of using them on the surface — can lower the chances of tuna fishermen accidentally hauling in dolphins and whales, according to research led by FIU and World Wildlife Fund in Pakistan.

Bycatch, the incidental capture of a nontargeted species, is the deadliest threat facing dolphins and whales.

Roughly 300,000 whales and dolphins are accidentally caught annually in global fisheries. Today, bycatch is the leading cause for the decline of 11 of 13 critically endangered species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List.

In a study of the fishing methods used by semi-industrial tuna gillnet fisheries

in Pakistan, an international team led by FIU Institute of Environment researcher Jeremy Kiszka determined lowering gillnets by 6 feet below the surface reduced dolphin bycatch by 78.5 percent while not significantly impacting tuna catch. Given the estimated 100,000 whales and dolphins accidentally caught each year in gillnets in the Indian Ocean, the life-saving potential is monumental.

Further research is needed to understand the underlying reasons for this effectiveness and to assess its impact on other marine species.

The study was published in the journal Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. n

Photo courtesy of WWF-Pakistan

Photo courtesy of NOAA/SEFSC, MMPA No. 21938

The oceans might have more to talk about than an entire season of the Real Housewives of … well … any city. Recent FIU research shows dolphin communities are buzzing with social intrigue, while another study indicates white sharks may not be as solitary as long-believed. What is behind these social interactions? How often do they hang out? Are some individuals more popular than others? FIU scientists are unraveling the secret social lives of sharks and dolphins because inquiring minds want to know!

NEW DISCOVERY MEANS DOLPHINS FORM LARGEST SOCIAL NETWORK OUTSIDE OF HUMANS CHECK OUT THE LATEST OCEAN GOSSIP!

By JoAnn C. Adkins

Acquaintances, friends and best friends. These multiple levels of relationships were once thought unique to people. But recent FIU research shows dolphins can also form multiple levels of alliances. People establish relationships at different social levels for a variety of reasons including social advantage, business opportunities and military operations. For male bottlenose dolphins living in Shark Bay, Australia, the motivation is a little less complex — the ladies. These dolphins actually form at least three different levels of cooperative relationships between groups to increase male access to females, according to the study led by Richard Connor, a Florida International University biologist and Stephanie King, an associate professor from the University of Bristol.

The male dolphins in Shark Bay form first-order alliances of two or three males to cooperatively pursue consortships with individual females. Their second-order alliances can include as few as four and as many as 14 unrelated males to compete with other alliances over access to females. Their third-order alliances occur between cooperating second-order alliances. The research team analyzed association and consortship data to model the structure of alliances among 121 adult male Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins, demonstrating the dolphins have the largest known alliance network outside of humans.

A key finding of the study is the importance of intergroup cooperation for male success. Intergroup cooperation in humans was thought to be unique and dependent upon two other features that distinguish humans from chimpanzees — the evolution of pair bonds and parental care by males. However, Connor said the research shows intergroup alliances can actually emerge without these features. This means cooperation among groups is more important than overall alliance size to increase access to females. Long story short, collaborative dolphins have greater reproductive success. n

GREAT WHITE SHARKS MAY BE SOCIAL AFTER ALL

By Angela Nicoletti

Great white sharks around Mexico’s Guadalupe Island sometimes hang out with each other — and while it’s not a popularity contest, some might just be a little more social than others.

FIU marine scientist Yannis Papastamatiou, Ph.D. candidate Sarah Luongo and a collaborative team of researchers used a combination of tracking tools around Guadalupe Island and found sharks tend to stick together when checking out local seal colonies and other patrolling. Associations tended to be short, but some sharks stick together for an hour or more at a time.

“Seventy minutes is a long time to be swimming around with another white shark,” Papastamatiou said.

Guadalupe Island is a hotspot for white sharks. The waters are very blue and very clear, making traditional ambushing tactics difficult for sharks. Prey here are easily seen, but that means the predator is equally visible so the research team wanted to see if the sharks were doing something different. They combined different commercially available technology into a “super social tag” that collects data for up to five days before popping off the shark’s dorsal fin and floating to the surface. It was equipped with a video camera and an array of sensors tracking acceleration, depth and direction. To see if they were buddying up, each tag included a sensor that could detect other tagged sharks nearby.

Data shows for the most part, sharks prefer to be in groups with members from their same sex. One shark, in a matter of a day-and-a-half, associated with 12 other sharks. Another had the tag on for five days and only spent time with two other sharks.

Some of the sharks were active in shallow waters, while others deeper in the depths. Some were more active during the day, others at night. The challenge of the hunt was reflected in the video footage analyzed by undergraduate Seiko Hosoki. A great white followed a turtle, but it got away. Another followed a sealion. It got away. These moments might indicate why forming social associations could be so important — they might be taking advantage of another’s hunting success.

Fun fact! White sharks might not be the only social sharks in the oceans. Papastamatiou and other FIU researchers are investigating the social activities of bull sharks, grey reefs and others. n

Some sharks could trade loner lifestyle for hunting advantage.

PARTNERSHIP DELIVERS RESEARCH EXPERIENCE TO SCHOOL STUDENTS

By Angela Nicoletti

EXPLORE ANGARI’S RESEARCH EXPEDITIONS

From aboard ANGARI — a 65-foot yacht converted into a research vessel — a group of Roosevelt Middle School students from West Palm Beach watched as a triangular shape sliced through the water, circling a sun-faded buoy. As the vessel closed in, the students started to realize it was exactly what they were looking for. “Shark!”

It would be the first encounter of the day, which included two hammerheads, two lemon sharks and one grumpy-looking goliath grouper. The middle schoolers and science teacher Eusebius Williams were on a unique fieldtrip hosted by FIU’s College of Arts, Sciences & Education and the ANGARI Foundation, as part of Coastal Ocean Explorers. The partnership offers realworld experience in marine science research.

Many of the students had never stepped foot on a boat before.

“I never worked with real scientists before. I think the best part of the trip was tagging the hammerhead shark,” said Roosevelt Middle School student Takikia Pierce.

The students observed, learned and worked side-by-side with the FIU team. Williams, who teaches 7th and 8th grade advanced science, says one of his primary goals is to connect classroom lessons to the world outside the classroom. He knows that when material doesn’t seem relevant to students, they lose interest.

Laura García Barcia helped bring the partnership to fruition while working on her Ph.D. in marine science at FIU. She graduated in 2023. For more than a year, she worked with FIU Assistant Director of Outreach Education Nick Ogle along with ANGARI President Angela Rosenberg and Amanda Waite, director of Science Education & Advancement.

“I knew that even if I was going to do it for a short time, as long as we could guarantee it was going to happen in the long term, it was worth it to go a little crazy for a few semesters,” García Barcia said.

The keystone of the partnership is a paid research assistantship for an FIU graduate student — a role responsible for overseeing and managing the Coastal Ocean Explorers: Sharks program, as well as assisting with other community outreach opportunities. Other FIU graduate and undergraduate students make up the crew of scientists on the expeditions.

The ANGARI Foundation was created in 2016 by Angela Rosenberg and her sister, Kari, to bridge the gap between science, research, education and the public. The ANGARI vessel — named by combining parts of their first names — was originally the Cassandra Jade, a yacht designed for leisure. They spent months converting the living room into a lab and creating indoor and outdoor workspaces. New state-of-the-art technology and equipment was installed.

“We’re excited to be working with FIU faculty and grad students who share the same mission and values of ANGARI Foundation — to demonstrate the importance of our oceans and share marine science research through hands-on experiences and education,” Angela Rosenberg said. n

SHARKS

CAN FIU SCIENCE TURN THE TIDE?

More than 500 feet below the ocean, a lone oceanic whitetip shark made a sudden move — quickly swimming straight for the surface. Busting through the waves, it breached with little warning. The unexpected move was a dramatic ascent considering most whitetips typically originate breaches more slowly and from more shallow depths.

Yannis Papastamatiou saw it all — the sudden shift in movement down below; the rapid rise to the top; the shark breaking through into daylight only to rapidly return to the waves. He didn’t watch in person. He didn’t see it on video. He witnessed the peculiar behavior in data. It was all there in a sea of numbers and charts that are helping him unravel the mysterious lives of these hard-to-study apex predators.

One of the world’s leading shark behavioral ecologists, Papastamatiou’s use of new tag technologies has advanced the field of predator ecology and contributed to Marine Protected Areas and wildlife migration corridors. Beyond the lab, Papastamatiou explores habitats most explorers never see including deep mesophotic reefs. His work focuses on a variety of ecosystems, from the coastal U.S. to the remote waters of French Polynesia. Having tagged more than 1,000 sharks in his career, he and his collaborators are providing critical information about sharks.

43% OF SHARK SPECIES ARE THREATENED WITH EXTINCTION

Papastamatiou joined Mike Heithaus at FIU in 2016, who at the time was the university’s lone shark researcher. Heithaus is one of the world’s leading experts on marine ecology, focusing on the ecological role of sharks on ocean health. Today, they are joined by a diverse team of scientists making up one of the largest shark research teams in the world. This includes forensic DNA expert Diego Cardeñosa, conservation biologist Mark Bond, acoustics specialist Kevin Boswell and quantitative fisheries biologist Yuying Zhang along with scientists studying shark prey including Richard Connor, Jeremy Kiszka, Alastair Harborne, Jennifer Rehage and Elizabeth Whitman They, along with students and researchers in their labs, are transforming the world’s knowledge about sharks and helping to secure a sustainable future for some of the most feared yet most imperiled animals in the ocean.

LOCAL & NATIONAL

REEFS SURVEYED ACROSS 58 COUNTRIES BY FIU AND COLLABORATORS LOOKING FOR HEALTHY SHARK POPULATIONS

When Cindy Gonzalez began working on her Ph.D. at FIU, she had already helped identify a new species of bonnethead shark off the coast of Panama. Once thought to be one abundant species, Gonzalez was part of a team that realized through DNA testing that multiple, similar-looking species of these small hammerheads exist in the region. The realization left conservationists with a myriad of questions. So when FIU scientists made a similar discovery among a bonnethead population off the coast of Belize, Gonzalez formally identified the newly realized species. She named it Sphyrna alleni after late Microsoft co-founder Paul G. Allen, a wildlife conservation advocate and supporter of FIU research. The discovery of a previously unknown species hiding in plain sight serves as a reminder of just how much science still has to discover in the world’s oceans. With each new understanding comes a greater realization that sharks are in trouble and much work remains.

ANSWERS GIVE RISE TO IMPACT

A decade ago, FIU led a global initiative and embarked on the world’s largest-ever survey of reef sharks and rays known as Global FinPrint and supported by the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. Early findings were shared with communities all across the world. While the data is still being researched, some nations have already taken action. When no sharks were detected off the coast of the Dominican Republic, FIU scientists shared this harsh reality with local officials. The country’s Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources issued a ban on fishing and trading of all sharks and rays in its jurisdictional waters. Since then, country officials continue to work with Global FinPrint scientists to monitor shark and ray activity with the goal of incorporating scientific data in all future management decisions.

In nearby Belize, more than 20 species of rays are known to populate local waters. These close relatives of sharks are at even greater risk of extinction than sharks, yet few sanctuaries include protections for rays. Data from Global FinPrint is helping to change that. FIU scientists found thriving populations of rays in the waters along Belize and upon sharing the data with local officials, the Belize Fisheries Department established the world’s first ray sanctuary to help protect local populations including the critically endangered smalltooth sawfish and endangered Ticon cownose. Since then, Belize officials have established a shark-fishing ban in the waters surrounding three atolls after additional FIU research documented a 10-year population decline.

NO-TAKE ZONE?

Recent FIU research has shown critically endangered scalloped bonnethead sharks do not often travel outside of their immediate surroundings, which has led the scientists to call for a “no-take zone” off the coast of Colombia. They want to prohibit the capture or removal of these small hammerheads. Working with local stakeholders, the scientists have provided strategies to protect the imperiled species while also safeguarding the needs of the community.

INVESTIGATING ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGES

Though the waters off the coast of the Bahamas provide legal protections for sharks, other challenges exist that could put healthy shark populations at risk. In Bimini, scientists from FIU professor Jose Eirin-Lopez’s Environmental Epigenetics Lab discovered changes in DNA patterns for juvenile lemon sharks exposed to metals from dredging for a commercial marina. One of the metals found, manganese, can cause neurological effects resembling Parkinson’s disease in humans. Similar effects have been found in mammals, and even fish. The team’s investigative techniques, while identifying a potential environmental problem for the Bahamas, offer a unique approach to identifying changes to an environment and potential threats to wildlife populations.

ECOLOGICAL ROLE OF SHARKS

For more than 30 years, Mike Heithaus has amassed a portfolio of work that has changed the world’s understanding of sharks and their roles in keeping oceans healthy. This includes 20+ years working in Shark Bay, Australia, producing the most detailed study on the ecological role of sharks in the world, and Global FinPrint, an ambitious worldwide collaboration to survey the world’s shark and ray populations. Now, Heithaus, Yannis Papastamatiou, Simon Dedman and Jerry Moxley, along with scientists from around the world, have published a review of the ecological importance of sharks in Science. Their work reveals sharks can be supreme architects of ocean health — from top-down and bottom-up. The takeaway is simple:

“If people want healthy oceans, we need healthy shark populations in many of our marine ecosystems,” Heithaus said.

According to the research, this means shark conservation must go beyond simply protecting shark populations — it must prioritize protecting the ecological roles of sharks.

The largest sharks of many of the biggest species, such as tiger sharks and great whites, play an oversized role in healthy oceans, but they are often the most affected by fishing. The big sharks help maintain balance by what they eat and who they scare. Sometimes their sheer size is enough to scare away prey, discouraging them from over-consuming seagrass and other plant life needed for healthy oceans. There are many other roles, including major things like moving nutrients around to more smaller roles like serving as scratching posts for smaller fish.

“This study verifies what we’ve long suspected — sharks are critical to ocean health,” said Lee Crockett, executive director of the Shark Conservation Fund, which funded the study. “This landmark study serves as confirmation that marine conservationists, philanthropists, policymakers, and the public alike need to recognize that sharks are keystone species that have a now-proven significant effect on marine environments.”

OF REEFS NO LONGER HAVE VIABLE SHARK POPULATIONS ACCORDING TO FIU RESEARCH

20% 100 MILLION

SHARKS ARE TAKEN FROM THE OCEANS EVERY YEAR ACCORDING TO FIU RESEARCH

SCIENCE OF ADVOCACY

A lack of public awareness can often be one of the biggest challenges facing conservation. For more than a decade, FIU scientists have worked in the world’s largest shark sanctuary, which is located in French Polynesia. These waters are an important economic engine for the local communities. The scientists recently evaluated local knowledge about sharks and the nearby shark sanctuary. What they found is designated protected areas are only effective if local stakeholders are aware of the rules and of the actual value of the sharks themselves. In the case of French Polynesia, only a quarter of those interviewed were aware of the rules of the sanctuary and fewer had any meaningful knowledge of the ecologic, economic and cultural value of sharks. It’s a major deficit in the plight to protect these important species. That’s why public outreach and engagement is a core function of FIU’s Shark Team, dividing their time among the field, the lab, the classroom and a variety of engagement opportunities.

PIVOTAL VICTORY

Data from Global FinPrint and other FIU studies contributed to a recent groundbreaking decision by world governments to award increased protections to 54 species of sharks during the Conference of the Parties of the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

“This decision is the most significant step toward improving global shark management that countries have taken,” said FIU conservation biologist Mark Bond, who helped lead international support for the successful proposal. “It will ensure international shark trade is regulated and traceable.”

The research was also used to update the status of four species to more threatened categories on the International Union for the Conservation of Natures (IUCN) Red List. Researchers from multiple FIU Marine Science labs also supported listings passed by CITES in 2016.

The work by FIU’s Shark Team has helped guide policy and serve as the underpinning for management decisions all across the world.

AT RISK OF EXTINCTION

Of all the challenges sharks face, overfishing may be the greatest threat. This is especially true for those that live around coral reefs. Recent FIU research indicates the problem is far worse than anyone realized. The five main shark species that live on coral reefs — grey reef, blacktip reef, whitetip reef, nurse and Caribbean reef sharks — have declined globally by an average of 63 percent. The data was collected as part of Global FinPrint, a five-year international study supported by the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation and co-led by researchers at FIU.

Examining more than 22,000 hours of video footage from baited remote underwater video stations across 391 reefs in 67 nations and territories, the scientists observed the staggering absence of meaningful shark populations in different parts of the world. Overfishing is likely the primary culprit driving reef sharks toward extinction and changing how reefs function.

TURNING THE TIDE

Off the coast of Colombia, forensic science and wildlife conservation are converging to disrupt hard-to-detect illegal wildlife trafficking. Diego Cardeñosa, an FIU biologist specializing in wildlife forensic DNA, is working with local port officials to detect poaching and illegal trade of wildlife and wildlife parts. His revolutionary work began with the hopes of ending wide-scale corruption in the shark fin trade, after proving the majority of the shark fins sold in markets come from threatened and endangered species. Today, his species detection methods have extended beyond sharks, identifying shipments of other protected animals and helped countries prosecute smugglers.

Cardeñosa works closely with government officials in regions where illegal trafficking is more common. Public engagement is a common thread throughout FIU research. Biologist Mark Bond has spent much of his career educating others on the plight of sharks — from young schoolchildren in South Florida and the Caribbean to environment ministry officials in other parts of the world. He is engaged in a grassroots initiative, traveling to rural villages and speaking with local fishing communities about the importance of protecting young oceanic whitetips within the Windward Passage between Haiti and Cuba. The goal is to make the fishermen a key part of saving the sharks. Many had seen or caught young whitetips. Few had ever saved one. Today, releasing whitetips that are inadvertently caught in fishing operations has become a standard practice in Haiti.

Knowing where sharks are and which species are present in a region is critical to protecting shark populations and supporting economies reliant on commercial fishing and healthy oceans. Through international collaborations, FIU researchers are filling in data gaps and providing new understanding — transforming how the world views sharks. Yet, many questions remain. When FIU scientists discovered the new species of bonnethead they would eventually name after Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist Paul G. Allen, it created a whole new set of issues for conservationists. How big is its population? Is its food source plentiful? Is it endangered? Questions like these remain for countless other species, both those known to science and those yet to be discovered.

FIU’S SHARK TEAM CONTINUES TO SEARCH FOR ANSWERS. THEY CONTINUE TO ADVOCATE ON BEHALF OF THESE ECOLOGICALLY AND ECONOMICALLY IMPORTANT ANIMALS, HOPING SCIENCE WILL TURN THE TIDE FOR SHARKS FIGHTING FOR SURVIVAL.

By JoAnn C. Adkins

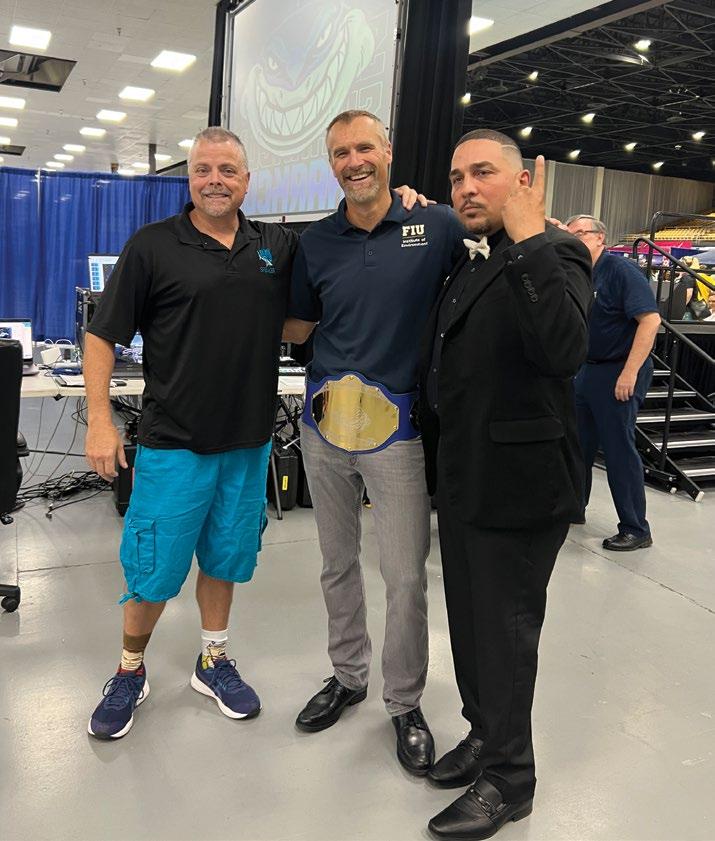

Mike Heithaus was named Shark Champion during the ninth annual SharkCon.

SharkCon celebrates shark lore and shark science while raising awareness about shark and ocean conservation. The past two events have featured FIU scientists, including Heithaus and Yannis Papastamatiou, along with alumnae Erin Spencer and Frances Farabaugh and students Candace Fields, Sara Casareto and Davon Strickland. Fans of National Geographic’s SharkFest, as well as school teachers, shark advocates and FIU alumni, stopped by the FIU exhibit to meet with the scientists who have appeared in recent shows.

Heithaus is a marine ecologist specializing in the ecological importance of sharks as well as the executive dean of the College of Arts, Sciences & Education and FIU vice provost of Environmental Resilience. The Shark Champion award is given annually to someone who has contributed to the wellbeing and long-term sustainability of sharks in the world’s oceans, according to SharkCon creator Spencer Steward. SharkCon is hosted every July in Tampa, Fla.

ON NAT GEO’S

FIU scientists have become a television mainstay on National Geographic’s SharkFest, going in search of the world’s largest hammerhead, finding answers to why sharks live among volcanoes and more.

In the past three years, FIU scientists, led by Yannis Papastamatiou and Mike Heithaus, have appeared in nine original shows and four multi-episode series as part of National Geographic’s annual event. Most recently, Papastamatiou and a team from his research lab explored human-shark encounters with Marvel’s newest Captain America, Anthony Mackie. The show, which headlined the 2024 season, investigated how environmental factors could be influencing shark behavior off the coast of Mackie’s native Louisiana.

Also in 2024, Heithaus paired up with ultra marathon sea swimmer Ross Edgley as the British athlete took on four of the ocean’s most formidable sharks in speed, strength, endurance and digestive challenges. SharkFest is a four-week summer event. All of the recent shows are currently streaming on Disney+ and Hulu.

FIU FEATURED

PRESCRIPTION DRUGS DISCOVERED IN FLORIDA FISH

By JoAnn C. Adkins

Pharmaceutical contaminants have been found in the blood and other tissues of fish in Florida waters during multi-year studies by FIU’s Institute of Environment and Bonefish & Tarpon Trust.

Medications found include opioids, antibiotics, blood pressure medications, antidepressants, prostate treatment medications, heart medications and others. Among 93 bonefish sampled in the Florida Keys, the scientists found an average of seven pharmaceuticals per bonefish, and a whopping 17 pharmaceuticals in a single fish. Researchers also found pharmaceuticals in bonefish prey — crabs,

shrimp and fish — suggesting that many of Florida’s valuable fisheries are exposed. The scientists next sampled 113 redfish in nine Florida estuaries. Pharmaceuticals were detected in all nine. Only seven of the fish sampled had no drugs in their system. The remaining averaged positive tests for two pharmaceuticals with some fish testing positive for as many as five different drugs. More than 25 percent of the fish exceeded levels of pharmaceuticals considered safe, which equates to one-third of the therapeutic levels in humans. The antipsychotic medication flupentixol was detected above safe levels in one of every five of the redfish sampled.

“These studies of bonefish and redfish are the first to document the concerning presence of pharmaceuticals in species that are important to Florida’s recreational fisheries,” said Jennifer Rehage, FIU professor and the study’s lead researcher. “Given the impacts of many of these pharmaceuticals on other fish species and the types of pharmaceuticals found, we are concerned about the role pharmaceuticals play in the health of our fisheries. We will continue this work to get more answers to these concerning questions.”

Approximately 5 billion prescriptions are filled each year in the U.S., yet there are no

environmental regulations for the production or disposal of pharmaceuticals worldwide. Pharmaceutical contaminants originate most often from human wastewater and are not sufficiently removed by conventional water treatment. They remain active at low doses and can be released constantly. Exposure can affect all aspects of fish behavior, with negative consequences for their reproduction and survival. Pharmaceutical contaminants have been shown to affect all aspects of the life of fish, including their feeding, activity, sociability and migratory behavior.

“The results underscore the urgent need to modernize Florida’s wastewater treatment systems,” said BTT President and CEO Jim McDuffie. “Human-based contaminants like these pose a significant threat to Florida’s recreational fishery, which has an annual economic impact of $13.9 billion and directly supports more than 120,000 jobs.” n

THE RESEARCH HAS MADE INTERNATIONAL HEADLINES INCLUDING FEATURES ON CNN, IN THE GUARDIAN AND EVEN THE DAILY SHOW.

FLORIDA KEYS CITY TO REPLACE SEWAGE WELLS FOLLOWING FIU RESEARCH FINDINGS

The Marathon City Council says it will end the use of shallow sewage wells, a move that could drastically reduce the pervasive pharmaceutical contamination in local fish uncovered by FIU scientists.

The announcement was made following a settlement with the citizen-based group Friends of the Lower Keys, which filed a lawsuit against the city for alleged violations of the federal Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act. The city council agreed to a plan to resolve the wastewater issues. Multiple research studies, including those by FIU, conclude the existing shallow wells are releasing nutrients and other contaminants to surface water in the Florida Keys.

Among the findings, FIU Professor Jennifer Rehage identified pharmaceutical contaminants in local fish that included blood pressure medications, antidepressants, antibiotics and pain relievers. Researchers also found pharmaceuticals in fish prey — crabs, shrimp and other fish — suggesting Florida’s valuable fisheries are exposed to these contaminants.

Photo courtesy of Ian Wilson

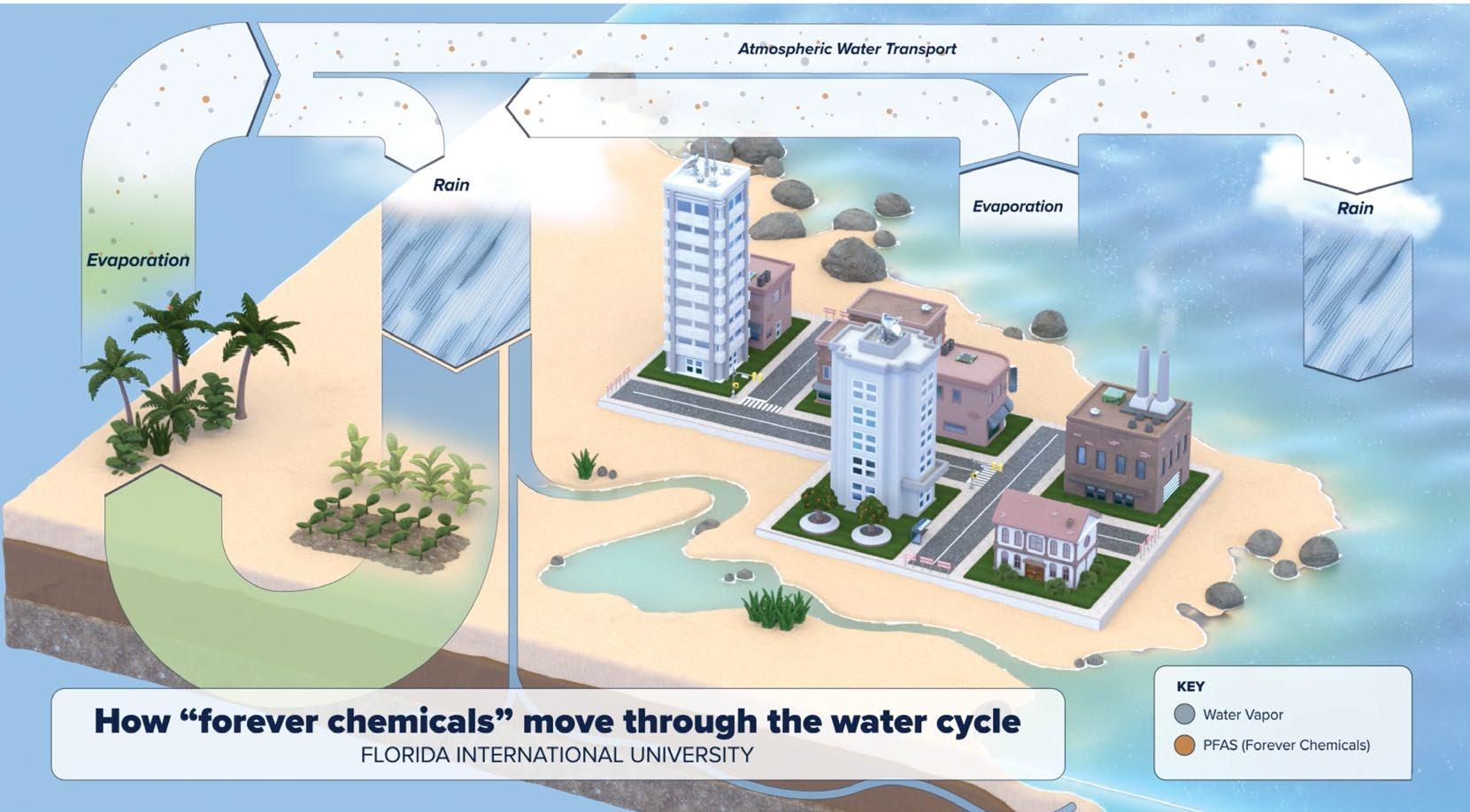

FLORIDA OYSTERS FOUND TO HAVE TOXIC “FOREVER CHEMICALS”

FIU Institute of Environment scientists detected contaminants in oysters from Biscayne Bay, Marco Island and Tampa Bay. All 156 samples contained perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl (PFAS) and phthalate esters (PAEs). These contaminants pose serious health risks to people and wildlife, and the oysters prove they are in the water and have crept into the food chain. The findings were published in Science of the Total Environment and will help inform possible solutions and new regulations to start to remove them from the environment.

IT’S LITERALLY RAINING IN MIAMI

By Angela Nicoletti

PFAS are in Miami’s rainwater. It is the latest evidence the synthetic “forever chemicals” hitch a ride on the water cycle, using the complex system to circulate over greater distances.

FIU researchers collected and analyzed 42 rainwater samples across three different sites in Miami-Dade County. A total of 21 perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, were detected.

While profiles of several PFAS matched back to local sources, others did not. According to the study, published in Atmospheric Pollution Research, this suggests Earth’s atmosphere acts as a pathway to transport these chemicals.

PFAS were created to be almost indestructible. Once in the environment, they accumulate over time. People can ingest or inhale them, and exposure has been linked to kidney damage, fertility issues, cancer and other diseases. The EPA has set strict near-zero limits for some PFAS in drinking water.

FIU Assistant Professor of Chemistry Natalia Soares Quinete leads the Emerging Contaminants of Concern lab in FIU’s Institute of Environment. Her research group is among the first to extensively track the prevalence of the persistent pollutants across

South Florida. They have detected PFAS in drinking water and surface water. And, subsequently, found PFAS in animals that live in those areas. Rain was the next place for them to look.

Between October 2021 and November 2022, the most frequently detected and abundant PFAS in Miami’s rainwater were PFCAs — commonly used in non-stick and stain-resistant products, food packaging and firefighting foams. The researchers previously detected high levels of these compounds in nearby surface waters, a sign they were coming from local sources.

PFAS concentrations suddenly skyrocketed during the dry season, coinciding with Northeastern air masses moving into Miami. More emerging PFAS were detected, including those typically found in North Carolina and other states where facilities produce goods made with these chemicals.

The researchers believe drier air in northern currents is creating perfect conditions for more PFAS-laden particles to spread around. Rain “washing out” those pollutants from the air could account for higher contaminant concentrations. The team hopes the data can help guide future solutions and regulations for controlling and reducing PFAS. n

Illustration by David Roberts

TECH TRACKS HEALTH OF BISCAYNE BAY

From an expanded corps of monitoring buoys to autonomous vessels, FIU researchers are deploying advanced technologies to protect the health of Miami’s Biscayne Bay.

Piero Gardinali, assistant director of the Institute of Environment, recently deployed a submersible profiling system that examines sediments in the water. For years, local officials believed a drop in oxygen was leading to high-profile fish kills in the bay, but Gardinali says the problem may be a little more complicated. He found that the presence of land-based runoff in the water combined with the low oxygen levels can actually produce hydrogen sulfide, a silent but deadly toxic gas.

Institute of Environment researchers are deploying buoys and other vessels equipped with special sensors that measure temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll, and more throughout the region. Two of the latest deployments include one off the International Center for Tropical Botany at the Kampong and another in the Biscayne Bay Canal, made possible by longtime FIU supporter Elliot Stone, founder of Royal Castle Builders. The buoys collect, analyze and transmit real-time data on water conditions to FIU as part of the university’s efforts to address and redress environmental contaminants.

SCAN TO WATCH

Brad Schonhoff, program manager for the Institute of Environment, deploys a monitoring buoy in a canal that feeds into Biscayne Bay.

MONSTERS OF THE DEEP REVEALED FOR WHAT THEY ARE

Grotesque little creatures with armorlike horns, misshapen torsos and some with spikes protruding from their sides are lurking in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. They appear in an array of oranges and blues, though several are see-through. Some appear part alien and part Hunchback of Notre Dame. They are the visions of which nightmares are made. But to marine scientist Heather BrackenGrissom, they are mostly shrimp. Some are lobsters. She says they’re all larvae.

There have been some observations of these bizarre, miniature-sized monsters in the past few centuries, but no one knew what they actually were. Ph.D. candidate Carlos Varela and BrackenGrissom have now identified 14 species of these larvae, using deep sea forensics to match the unknown larvae to their known adult counterparts.

The research team sent large nets down to deep waters in the gulf to retrieve the specimens. Back in the lab, they conducted genetic tests to connect the dots in an evolutionary family tree. Shrimp are known to go through multiple larval stages, and Bracken-Grissom said some of the species they identified experience many different larval stages throughout their life cycles. Some of the species they collected have only been seen in their larval forms by scientists a handful of times, some never at all.

“I like that we’re getting to reveal this mysterious and bizarre world that we don’t typically get to see,” Bracken-Grissom said.

This is not the first time Bracken-Grissom has given an identity to the monsters of the deep. Among the specimens collected in this latest research endeavor was an intact larva she has only seen once before — it’s a species she identified in 2012. Originally known as Cerataspis monstrosa, BrackenGrissom used the same genetic methods then to reveal this tiny monster is actually a young form of a shrimp known to scientists as Plesiopenaeus armatus

While Varela and Bracken-Grissom have provided insight into these 14 creatures, there are countless others in a variety of life cycle stages that scientists still don’t know who the mommies and daddies are. Solving these mysteries in the name of biodiversity is largely what drives Bracken-Grissom to keep searching. The team collected the latest larval specimens as part of the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative. n

IDENTIFY AN UNKNOWN SPECIES OF “MONSTER” LARVA, PART OF AN INTERNATIONAL TEAM THAT CAPTURED THE FIRST-EVER VIDEO OF GIANT SQUID IN U.S. WATER AND HAS BOTH A SPECIES OF CRAB AND SHRIMP NAMED AFTER HER.

SHRIMP GET A GLOW-UP

New study finds bioluminescence more common than previously thought

Apparently, the ability to glow doesn’t make you special — if you’re a shrimp in the deep sea, anyway.

Scientists have discovered bioluminescence is actually pretty common among deep-sea shrimp, with a new study identifying 157 species that are believed to possess the ability to emit light. Some do it by vomiting luminous secretions and others through specialized light organs in their bodies. Some even do both. The reasons why they do it are just as diverse as how they do it, according to study authors Stormie Collins, a Ph.D. student at FIU, and Associate Professor Heather BrackenGrissom. They say some shrimp may use bioluminescence for camouflage, others for defense and others to communicate with fellow shrimp.

“We are learning that bioluminescence is much more common than previously thought, not only within shrimps, but across all deep-sea animals,” Collins said. “We hope this study can advance the field of sensory biology and foster an appreciation for the intricate beauty of deep-sea shrimp beyond just a snack during happy hour.”

This latest study increases the total number of suspected glowers by 65 percent, with a previous review only identifying 55 species of bioluminescent shrimp.

NSF FUNDS RESEARCH TO UNCOVER SECRETS OF SHRIMP LIVING AMONG DEEP OCEAN’S UNDERWATER

VOLCANOES

Some deep-sea shrimp, believed to be blind, travel great distances to reach their home — a boiling hot abyss at the bottom of the ocean with zero sunlight that’s toxic to most other life.

Now, FIU marine scientist Heather Bracken-Grissom — along with Tamara Frank, professor at Nova Southeastern University, Sönke Johnsen, full professor at Duke University and Jon Cohen, associate professor at the University of Delaware — hopes to uncover the secrets of these strange shrimp.

With a $1.35 million National Science Foundation (NSF) grant, the team is using cutting-edge technology, capable of descending to the crushing pressure of the sea floor where the shrimp live, to investigate them and their environment. Vent shrimp, as they are commonly called, swarm to the ocean’s hydrothermal vents. Discovered in 1977 and sparsely scattered across mid-ocean ridges, the vents resemble tall chimney-like structures that spew clouds of toxic chemicals reaching upward of 700 degrees. Some species of vent shrimp crowd together in the thousands on the sides of these vents, forming patches of ghostly white. It’s the equivalent of living on the side of a volcano, though they are not born here. As larvae, they typically reside hundreds or even thousands of feet away.

“There’s a lot of mysteries surrounding these shrimps, like how do they even find the vents,” Bracken-Grissom said. “Is vision involved in the detection over short distances, and once there, how are they so successful? We’ll hopefully be able to answer some of these questions.”

WHEN THEY NEED A POWER NAP, SHARKS GO SURFING

By Angela Nicoletti

Gray reef sharks can’t hang ten, but they’re still pretty rad surfers.

They surf to conserve energy, according to new research led by FIU marine scientist Yannis Papastamatiou along with an international team of researchers. They found hundreds of gray reef sharks in the southern channel of Fakarava Atoll in French Polynesia are surfing the slope by floating on the updrafts from currents.

During a diving trip, Papastamatiou observed sharks swimming against the current but barely moving their tails.

The sharks had developed a conveyer-beltlike system. When one shark reached the end of the line, it allowed the current to carry it back to the beginning point. The next shark in line did the same. And then the next.

The team used acoustic tracking tags, animal-borne cameras and their underwater observations to monitor the behavior. They calculated energy usage of those that stayed

in the channel surfing and those that left the channel. By hanging out and surfing the slope, the researchers say the sharks cut their energy by at least 15 percent. For an animal that can never stop swimming, the surfing action gives them much-needed rest.

Fakarava is a famous dive site and home to 500 gray reef sharks. Papastamatiou joined marine biologist Laurent Ballesta and others on a trip to film the French research documentary 700 Requins Dans La Nuit, which National Geographic later aired as the shortened version 700 Sharks. They were there to document the sharks’ afterdark behavior when the channel becomes a hunting ground. But it was during the daytime dives when Papastamatiou realized many of the sharks remained in the channel even though they weren’t actively hunting.

He worked with Gil Iosilevskii from the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology to use a detailed map constructed from the multibeam sonar system to predict and model where possible

updrafts might appear, depending on the direction of the tides. The team put tracking receivers along the channel to capture the sharks’ location. More than 40 gray reefs also had special tags to gather data on their activity and swimming depth.

Data confirmed the sharks stayed in the channel during the day and selected updraft areas. To save maximum energy, the sharks also changed how deep they go to surf the slope. During incoming tides with strong updrafts, they went deeper where the current was weaker. During outgoing tides, when there’s more turbulence, they moved closer to the surface for a smoother ride.

These findings could apply to other coastal areas and possibly explain why there may be larger numbers of sharks in certain places. It could even help predict why sharks may prefer one area over another.

The findings were published in Journal of Animal Ecology. n

Photo courtesy of Laurent Ballesta

CATCH OF THE DAY: MELLOW, THE FIU-TAGGED TIGER SHARK

Mellow was in the deep waters off the coast of Belize when he spotted a champagne snapper.

Unfortunately for that snapper, it was on the other end of Tim Banman’s fishing line. Mellow went in for the steal and got himself hooked. It’s a situation the nearly 10-foot-long tiger shark had found himself in four months before.

That’s when Mellow was reeled in by then-Ph.D. candidate Devanshi Kasan and Demian Chapman – Kasan’s Ph.D. advisor and Manager of Sharks & Rays Conservation Research at Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium. They tagged him as part of their long-term project monitoring shark and ray populations in Belize.

They named him Mellow because of his chill, unbothered temperament. That name corresponds with a number on the bright green tag they affixed to his lower dorsal fin just before releasing him.

The tag is a form of shark identification. The hope is if someone finds a shark with one of these tags, they contact the researcher to share where and when the encounter happened.

Banman tracked down the FIU researchers who tagged the shark –and that update about Mellow contributes to the data the researchers have compiled about how tiger sharks use habitats in Belize. n

MYSTERIOUS ARCTIC SHARK SPOTTED IN THE CARIBBEAN THOUSANDS OF MILES FROM HOME

A half-blind shark thought to live in freezing Arctic waters, scavenge on polar bear carcasses and survive for hundreds of years, turned up in an unexpected place — a coral reef off Belize. This marks the first time a shark of its kind has been found in western Caribbean waters.

Devanshi Kasana, then-Ph.D. candidate in the FIU Predator Ecology and Conservation lab, was working with local Belizean fishermen to tag tiger sharks when they found an old looking sluggish creature with a blunt snout and small pale bluish colored eyes on the end of their line. These clues led scientists to think it was a member of the sleeper shark family.

Kasana texted her Ph.D. advisor Demian Chapman to share the news and sent a photo of the shark. Chapman said it wasn’t a six gill. It looked a lot like a Greenland shark. After conferring with several experts, the surprising visitor was confirmed to be a Greenland shark.

MAKING WAVES

VOMITING SHRIMP NAMED IN HONOR OF BRACKEN-GRISSOM

Scientists who discovered a new species of shrimp have named it in honor of Heather Bracken-Grissom, FIU professor and assistant director of the Institute of Environment’s Coastlines and Oceans Division. The naming honors Bracken-Grissom’s long-time dedication and contributions to the study of decapod evolutionary history. The newly discovered species, Acanthephyra heatheri, was identified by scientists at the Shirshov Institute of Oceanology. The deep-sea shrimp, which lives in some of the darkest parts of the ocean, can emit bioluminescent vomit. This is the second species named in honor of Bracken-Grissom. Previously, a species of hermit crab found in the Gulf of Mexico was named to honor her contributions.

SHARK DNA DETECTIVE NAMED TO EXPLORERS CLUB 50

Diego Cardeñosa has embarked on a career to disrupt the illegal shark fin trade, efforts that earned him a spot in the Explorer’s Club 2023 EC50. This annual award recognizes 50 people changing the world including scientists, educators and conservationists. Cardeñosa was recognized for his extensive and groundbreaking shark DNA research and his dedication to marine conservation. Using molecular and forensic science, Cardeñosa is fighting the illegal trade of endangered sharks with custom DNA toolkits that can provide fast, on-site results for questionable shipments at ports of entry. Working with law enforcement in South America and across the world in Hong Kong, he has deployed these toolkits to track, detect and, in some cases, stop illegal wild trafficking of products from endangered sharks. His toolkits have also helped stop illegal shipments of other animals including European eels and South America’s bizarre matamata turtles

In 2022, Cardeñosa was awarded the Directorate of Criminal Investigation and Interpol medal from the global agency. The award came days after another achievement: the publication of a study led by Cardeñosa that used DNA detective work to uncover that two-thirds of species in the global shark fin trade are threatened with extinction.

FOURQUREAN INDUCTED IN FLORIDA ACADEMY

James W. Fourqurean — Distinguished University Professor and director of FIU’s Institute of Environment’s Coastlines and Oceans Division — has been inducted in the Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine of Florida, recognizing his decades of work protecting Florida’s coastlines. Fourqurean is a foremost expert on seagrass ecosystems and blue carbon, which describes carbon captured by the world’s oceans and coastal ecosystems. He’s also one of the lead scientists in the International Blue Carbon Working Group, as well as scientific representative to the International Blue Carbon Policy Working Group. These teams set out to have seagrasses recognized as a valuable resource, critical to helping slow the rise of C02 in the atmosphere. They’ve helped to include these coastal ecosystems in national greenhouse gas inventories.

HEITHAUS NAMED SHARK CHAMPION

Mike Heithaus was named Shark Champion of the year during the ninth annual SharkCon. Heithaus is a marine ecologist specializing in the ecological importance of sharks as well as the executive dean of the College of Arts, Sciences & Education and vice provost of environmental resilience and the Biscayne Bay campus. The award is given annually to someone who has contributed to the well-being and long-term sustainability of sharks in the world’s oceans, according to SharkCon creator Spencer Steward. Heithaus has dedicated his career to unraveling the mysterious lives of sharks and other large marine creatures. His work in Shark Bay, Australia is the most detailed study of the ecological role of sharks in the world. Working with several prominent non-governmental organizations, it has been used as the underpinning for affecting positive policy changes.

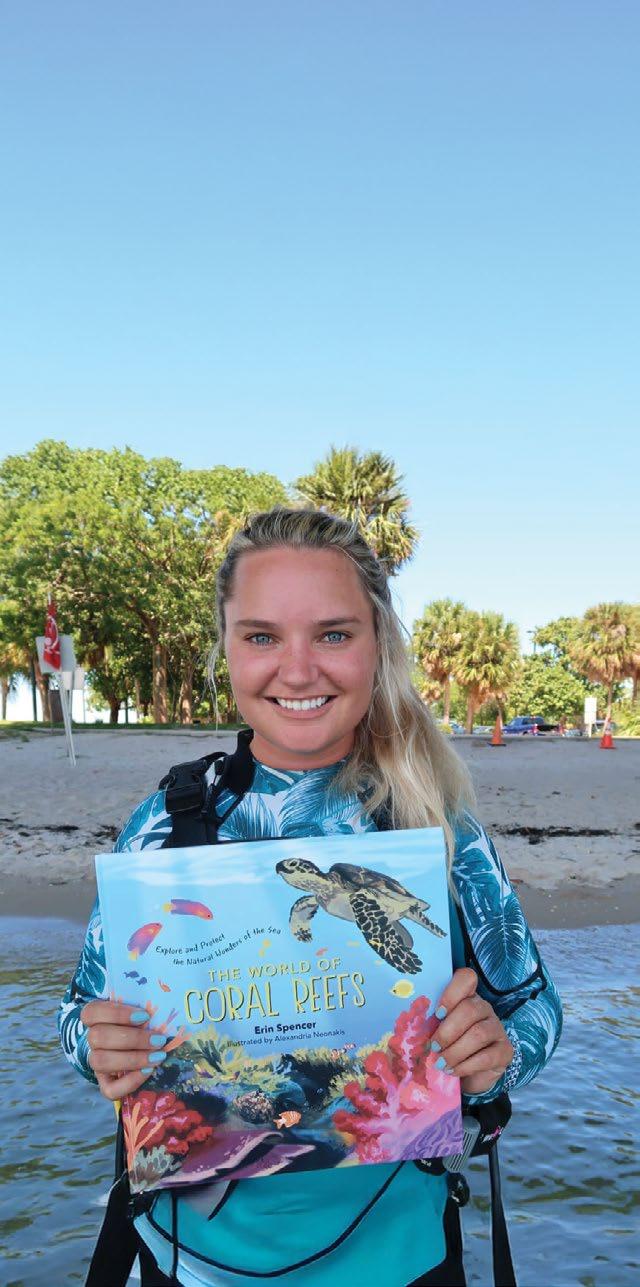

PH.D. STUDENT AUTHORS TWO CHILDREN’S BOOKS

While a Ph.D. student, Erin Spencer authored her first science-focused children’s book, The World of Coral Reefs: Explore and Protect the Natural Wonders of the Sea, in 2022. Spencer, who graduated in 2024, wrote a second book, The Incredible Octopus as she was preparing for graduation. While at FIU, Spencer conducted research under the direction of Professor Yannis Papastamatiou and FIU’s Predator Ecology and Conservation lab. Today, Spencer is the communications manager for restoration at the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. Both books are published by Storey and available on Amazon as well as other retailers.

STUDENT NAMED DAVIDSON FELLOW

FIU Ph.D. student Sara Casareto has been named a Davidson Fellow for her research on multispecies shark nurseries. The Davidson Fellowship program offers students the opportunity to conduct research within a National Estuarine Research Reserve. Each two-year project employs the tenets of collaborative research, including engaging end-users, incorporating multidisciplinary perspectives, and ensuring outcomes that are applicable to local coastal resource management needs and decision-making.

STUDENTS NAMED GUY HARVEY FELLOWS

Two FIU students — biology Ph.D. candidate Morgan Jarrett and biology Ph.D. student Rainer Moy-Huwyler — have been named 2025 Guy Harvey and Florida Sea Grant Fellows. The fellows program promotes the work of graduate students in the marine conservation field. Each fellow receives a combined $5,000 award from the Guy Harvey Foundation and the Florida Sea Grant to support their research and academic work. Jarrett studies the Caribbean spiny lobster and Caribbean king crab and the effects of environmental stressors such as high temperature and reduced oxygen availability. Moy-Huwyler’s research focuses on analyzing the metabolic processes of predatory fish in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. By understanding how these species utilize energy, his work supports efforts to conserve marine ecosystems and enhance the management of protected habitats. Jarrett and Moy-Huwyler join previous Guy Harvey and Florida Sea Grant awardee William Sample, an FIU Ph.D. candidate who received the fellowship in 2024.

FIU LAUNCHES GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE TOURISM DEGREE

FIU’s Chaplin School of Hospitality & Tourism Management and the College of Arts, Sciences & Education have launched an online bachelor’s degree focused on the global tourism industry and its relationship to the environment.

Global tourism’s impact on the health of the planet and the environment’s effects on the prosperity of the tourism industry – the world’s second largest industry – have propelled the creation of a fully online Bachelor of Arts degree in Global Sustainable Tourism. Faculty in the Chaplin School and the Department of Earth and Environment have designed the program to give students the knowledge to lead the hospitality and tourism business sectors on sustainable practices, resiliency and advocacy in this emerging field.

A blend of new and existing courses offer students an educational pathway toward rewarding careers in sustainability and job positions that did not exist just a decade ago. According to Visit Florida, visitors spend over $100 billion a year in Florida, supporting more than a million jobs. About 10 percent of the state’s total Gross Domestic Product comes from tourism. The program focuses on protecting natural resources, which in turn would protect tourism dollars.

More than 100 researchers from FIU have authored articles for The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization. This platform enables scholars, researchers, and doctoral students to share their expertise and research findings with broad audiences. FIU researchers have covered a wide range of topics through their contributions including many focused on Life Below Water. These articles have attracted more than 5 million views and have been republished by national and international outlets including CNN, PBS, Scientific American, The Washington Post and others.

WHY DID THE MEGALODON DISAPPEAR?

Megalodons were some of the most powerful predators to ever roam the oceans. With jaws that could span 10 feet and a bite force of 40,000 pounds per square inch, they hunted massive prey, including whales, seals, and even other sharks. These apex predators ruled the seas for millions of years, growing up to 60 feet in length and weighing more than 50 tons. Mike Heithaus highlights how the megalodon’s dominance in the ocean was eventually challenged by environmental issues, loss of prey, and competition from other predators like the great white shark.

OCEANS WITHOUT SHARKS?

Read the full article

Read the full article

Mike Heithaus and a team of researchers reviewed decades of research on sharks’ ecological roles. They found that because sharks play such a diverse and important role in maintaining healthy oceans, their current decline is an urgent problem. Heithaus emphasizes the need for nations to rethink where and how to conserve sharks for healthy oceans.

WHAT DOES AN OCTOPUS EAT? WITH A BRAIN IN EACH ARM, WHATEVER’S WITHIN REACH

Octopuses use a variety of clever strategies to capture prey, including venom and powerful beaks. Found in all oceans, from tropical reefs to the deepest parts of the sea, octopuses change color and texture to blend into their environment. Their remarkable intelligence, including solving puzzles and escaping enclosures, makes them stand out among invertebrates. However, octopuses face serious threats. Researchers highlight the need for people to take action, including reducing plastic use and cutting carbon emissions, to protect these fascinating creatures.

Read the full article

BLUE WHALES RETURN TO EASTERN AFRICA

The return of blue whales in eastern Africa following intense whaling offers hope. Jeremy Kiszka discusses his research on blue whales in the Seychelles. The research, which includes acoustic monitoring and vessel surveys, is crucial for understanding the whales’ behavior, migration patterns, and conservation needs, particularly in the Indian Ocean. The findings also highlight the importance of local collaboration in protecting these rare animals.

TRACING ORIGINS OF FOREVER CHEMICALS

FIU researchers Natalia Soares Quinete and Olutobi Daniel Ogunbiyi uncover how “forever chemicals” impact Biscayne Bay’s delicate marine ecosystem, tracing PFAS from septic systems and landfills to streams that ultimately flow into ocean ecosystems where fish, dolphins, manatees, sharks, and other marine species live.

MANATEES AT RISK OF MALNUTRITION

Aarin-Conrad Allen highlights the threats facing the Florida manatee, including boat strikes, harmful algal blooms, cold-stress syndrome, and entanglement in marine debris. A recent shift in manatee diet, from seagrass to more algae, has been observed following significant seagrass loss in the Indian River Lagoon, largely due to nutrient pollution. This dietary change poses a risk to their health, as algae lacks the nutrients found in seagrass. Restoration efforts to improve water quality are underway, but addressing pollution from septic systems and strategies for warming waters are essential for the long-term survival of manatees.

BIOLUMINESCENCE AND WHAT WE DON’T KNOW

FIU’s Danielle DeLeo and Andrea Quattrini of the Smithsonian Institution explore the phenomenon of bioluminescence in deep-sea organisms, particularly a diverse group of softbodied corals. Bioluminescence is found in at least 94 living species, including fireflies and deep-sea fish. Their research suggests bioluminescence likely evolved over 540 million years ago during the Cambrian Explosion and may have initially helped organisms reduce harmful free radicals before evolving as a communication tool.

rd

POSITIVE IMPACT ON LIFE BELOW WATER

Times Higher Education Impact Rankings 2024

COLLEGE OF ARTS, SCIENCES & EDUCATION in the world