Dwayne Wilcox - Oglala Lakota - Blue Bull 1st Place Mixed Media Fine Arts 2-D

Dwayne Wilcox - Oglala Lakota - Blue Bull 1st Place Mixed Media Fine Arts 2-D

Dwayne Wilcox - Oglala Lakota - Blue Bull 1st Place Mixed Media Fine Arts 2-D

Dwayne Wilcox - Oglala Lakota - Blue Bull 1st Place Mixed Media Fine Arts 2-D

to the 59th Annual Heard Museum

Guild Indian Fair & Market. This highly anticipated event is a time to celebrate art, diverse cultures, and community as we bring together more than 600 American Indian, Canadian First Nations, and Alaska Native artists, plus more than 10,000 visitors along with our museum staff and hundreds of volunteers. This art-focused weekend will engage our senses, stimulate our curiosity, warm our hearts, and fill us with awe and joy. We are so delighted to have you share the magic with us!

Each year the Heard Museum campus transforms into a sea of tents filled with artists representing many tribal affiliations, cultural traditions, and artistic visions. Our artists labor throughout the year to bring their best works to our fair, and we hope you will take advantage of the opportunity to talk with them about their media, styles, techniques, and creative explorations. There is so much to see and learn. We hope you will spend the full weekend with us and that you will share your experiences with others.

Thank you so much for joining us at this amazing event. We are grateful for your support and hope you will return often to the Heard Museum.

Best,

DAVID M. ROCHE , Heard Museum Director & CEO MARY ENDORF, Heard Museum Guild PresidentSHELLEY

MOWRY, Fair ChairSPECIAL THANKS TO ALL OF OUR 2017 FAIR SPONSORS

CIRCLES OF GIVING VIP TENT SPONSOR

APS (Arizona Public Service Company)

BEST OF SHOW PATRON SPONSOR

Native American Art Magazine

Kristine and Leland W. Peterson and Joy R. and Howard R. Berlin

MEDIA SPONSOR

First American Art Magazine

CORPORATE SPONSOR

Canyon Records

BEST OF SHOW AWARD SPONSOR

Arizona Lottery

ANDY EISENBERG AWARD FOR CONTEMPORARY JEWELRY

Leslie M. Beebe and Bruce Nussbaum

CONRAD HOUSE CUTTING EDGE AWARD

Eric Tack in memory of Paul E. & A. Caroline Tack

BEST OF CLASSIFICATION SPONSORS

Anonymous

Heard Museum Gift Shops

Heard Museum Guild

Dr. Mari Koerner and Frank Koerner

G. M. and Barbara Korn

PRO EM Party and Event Rentals

Scottsdale Native American Galleries (King Galleries, Territorial Indian Arts & Antiques, John C. Hill Antique Indian Art, Cowboy Legacy Gallery, and Expressions Galleries)

Waddell Trading Company

1ST PLACE SPONSORS

Delores Bachman

Neil S. Berman

Cerele Bolon

Mary and Mark Bonsall

W. David Connell

Dee Dowers

Faust Gallery

Jeanie M. Harlan

Georgia Heller and Denis Duran

Dr. Donald and Judith Miles

Susan and James Navran

Valerie and Paul Piazza

Betty Van Denburgh

2ND PLACE SPONSORS

Carol Cohen

Janet and Jim Darrington

Shirley and George Karas

Colleen and John Lomax Jr.

Saralou and Carl G. Merrell

Norma and Burt Miller

Kenneth Noone

Betty Van Denburgh

Claire and Myron Warshaw

Anonymous

Neil S. Berman

Katherine Blackstock

William (Dan) Broome

Roberta Buchanan

IlgaAnn Bunjer

Norine and Robert Heinrich

Patricia and Larry Kilburn

Dr. Edward and Phyllis Manning

Jan and Mike McAdams

Catherine Meschter and Jane Sidney Oliver

David Newark

Anonymous

Kay and Louis Benedict

Judy and John O. Carpenter

Ellen Cromer

Judith Dobbs

Barbara Filosi

Cozette Matthews

Jean and Wayne Meier

Gloria Murison

Ellen and Rex Nelsen

Barbara and William Sparman

Judy Wallace

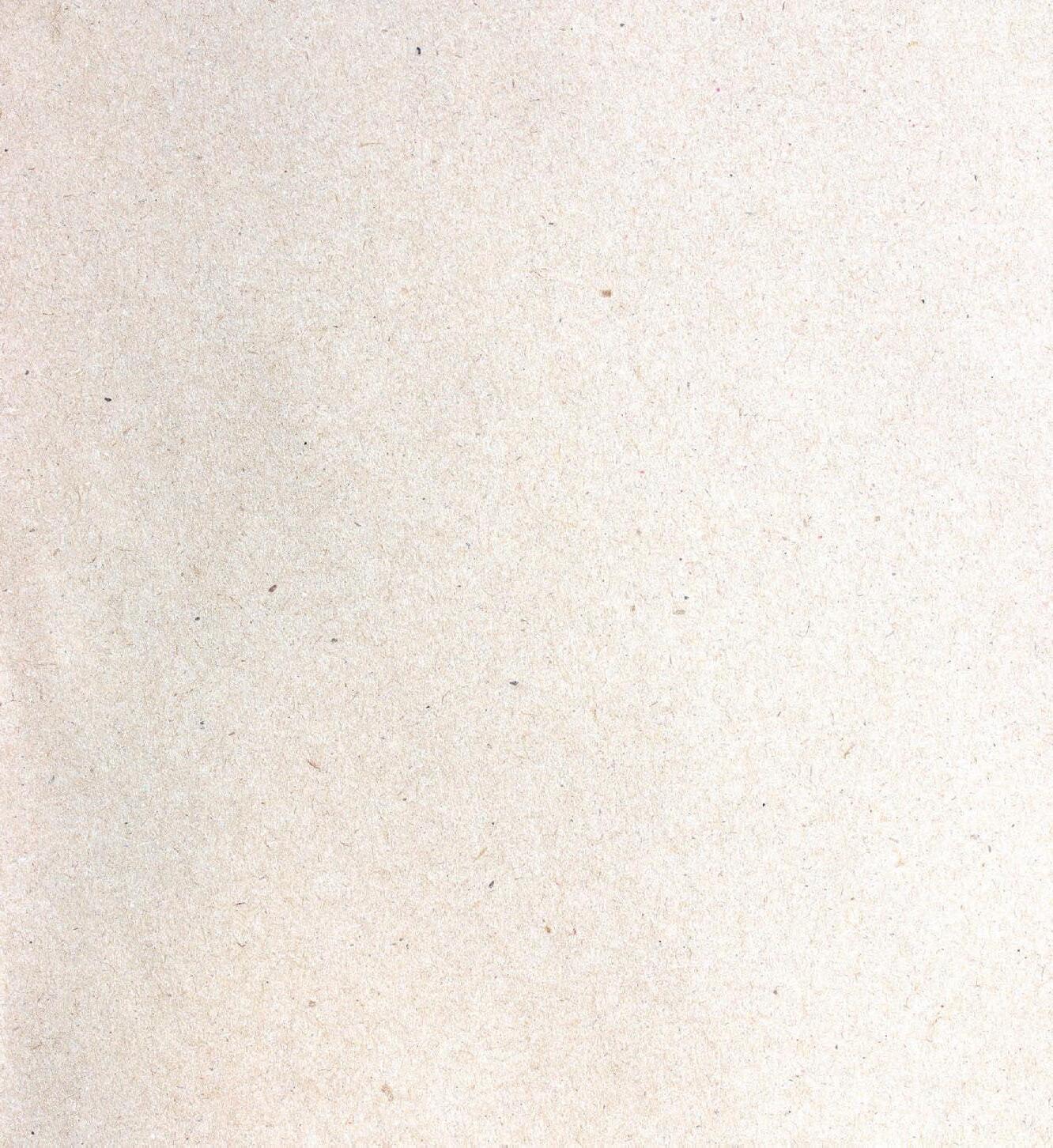

COVER

Unknown Navajo Artist, Serape, ca. 1860–1870, handspun wool, raveled bayeta, 63 2/5 × 50 2/5 in., Fred Harvey Fine Arts Collection at the Heard Museum, 207BL, underwritten by Jean and James Meenaghan.

59TH ANNUAL HEARD MUSEUM GUILD INDIAN FAIR & MARKET OFFICIAL GUIDE

Published by First American Art Magazine, LLC, in partnership with the Heard Museum

Publishing Editor: America Meredith (Cherokee Nation)

Copy Editor: Rosa Cays (Chicana)

Proofreaders: Ronda Rawlins, Staci Golar

Layout and design: America Meredith, Neebinnaukzhik Southall (Rama Chippewa)

Advertising Representatives: Barbara Harjo (Cherokee descent), Pauline Prater (Cherokee Nation)

© 2017 All rights reserved.

First American Art Magazine 133 24th Avenue NW #126 Norman, OK 73069 events@FirstAmericanArtMagazine.com www.FirstAmericanArtMagazine.com

20 ATHABASCAN GATHERING

The Heard Fair brings together Athabascan artists from Alaska, Canada, and the Southwest

By Martina Dawley, PhD (Hualapai-Navajo)

By Martina Dawley, PhD (Hualapai-Navajo)

26 KENNETH JOHNSON

Southeastern Virtuoso

Muscogee-Seminole jeweler makes dazzling designs that stand the test of time

By Staci Golar (Welsh-Cornish-American)

30 BREAKING NEW GROUND

Kathleen Wall’s Artistic Explorations

Jemez ceramic artist explores cultural issues by branching into video, painting, and installation

By America Meredith (Cherokee Nation)

34 KEEPING THE PROMISE

Master Diné Weaver Roy Kady & His Apprentice Program

A new generation of Diné artists are reinvigorating herding and weaving culture

By Cathy Short(Citizen

Potawatomi)DEPARTMENTS

1 0 Fair Highlights

11 Silent Auction + Raffle + Artist Demonstrations

12 Performance Schedule

14 2016 Best of Show Winners

16 2017 Juried Competition Judges

18 Fair Services

19 Map of the Heard Museum Campus & Fair

38 Heard Museum Shop + Books & More

DATES AND HOURS: Saturday, March 4, 9:30 am to 5:00 pm (Early-bird admissions for museum members Saturday only, 8:30 am). Sunday, March 5, 9:30 am to 4:00 pm.

All events take place at the HEARD MUSEUM , 2301 N. Central Avenue, Phoenix, and will be held rain or shine.

BEST OF SHOW RECEPTION: Friday, March 3, 5:30 pm to 8:00 pm at the Heard Museum. $75 for Heard Museum members; $100 for non-members. Reservations required. For tickets, visit heard.org/fair or call (602) 251-0209 ext. 2276. Tickets include a showing of this year’s award winners from the juried art competition, a stunning fashion show, light-fare food stations, no-host bar, opportunities to meet the artists, and a chance to view and bid on artist-donated works and more at our silent auction.

• 600+ juried Native artists, including youth, working in pottery, jewelry, wearable fashions, home furnishings, weaving, painting, carving, diverse arts, basketry, & more

• Artist demonstrations

• Cultural performances: Relax on the lawn and enjoy the jazz rhythms of the R. Carlos Nakai Quartet as well as Native dancers, singers, and more

• Canyon Records recording artists performing on the Courtyard Stage

• Storytelling and crafts for children

• Book signings

• Admission to Heard Museum exhibits, including the new Grand Gallery, included with your fair ticket (an $18 value)

• Specially designed fair merchandise commemorating this year’s event

• Silent auction open for viewing and bidding during Best of Show reception Friday night and all day Saturday

• Raffle tickets on sale throughout the weekend offering chances to win artist-donated works

• A broad menu of food choices, from simple snacks and refreshing beverages to casual lunch options

• Free parking at lots close to the museum campus

• Easy access to light rail across from the museum’s main entrance

Our silent auction will use mobile bidding technology for the first time this year, making participating easier and more accessible than ever before. Bid on auction items with the convenience of your mobile phone from anywhere, at any time! Registration for this event is as easy as sending a text message. You won’t want to miss the opportunity to win outstanding artworks donated by our fair artists and other fabulous prizes.

Register, bid, and preview auction items by visiting HEARDMKT2017.AUCTION-BID.ORG

The auction opens online on February 17 and continues until the close of bidding Saturday, March 4, at 9:00 p.m. Fair visitors can view the auction items in the south pre-function area of Steele Auditorium during the Best of Show event on Friday, March 3, and during regular fair hours on Saturday, March 4. Winners will be notified by text message at the close of the auction on Saturday night and will be given free admission to the fair on Sunday, March 5, to pick up their auction items. Shipping of purchased items may be arranged at an additional cost.

Raffle tickets will be on sale throughout the fair weekend. Please consider purchasing raffle tickets sold by our fair volunteers at locations throughout the Heard Museum campus. Raffle drawings will be held several times during the weekend. You do not need to be present to win one of the outstanding artworks created and donated by participating fair artists.

Buy more tickets to increase your chances of winning!

• $2 – 1 TICKET

• $10 – 6 TICKETS

• $30 – 20 TICKETS

We thank our Heard Fair artists and other community supporters for their generous donations to both the silent auction and raffle. All proceeds from the silent auction and raffle go to support the mission and programs of the Heard Museum, including support for the Indian Fair & Market.

Watch the masters at work creating new pieces! You’ll have the opportunity to see the creative magic unfold in the artist demonstration area (Area K, adjacent to the Steele Auditorium), throughout the weekend:

• RON CARLOS (Piipaash), pottery

• ARIC CHOPITO (Zuni), weavings and personal attire

• ERNEST HONANIE (Hopi), carvings

• PETER RAY JAMES (Navajo), diverse art

• ROY KADY (Navajo), weavings

• MARLOWE KATONEY (Navajo), weavings

• ROYCE MANUEL (Salt River Pima-Maricopa), diverse art

• JILLI OYENQUE (Ohkay Owingeh), baskets

• YOLANDA HART STEVENS (Piipaash-Quechan), diverse art

• NORBERT PESHLAKAI (Navajo), jewelry

• MELANIE SAINZ (Ho-Chunk Nation), beadwork

• CHARLENE SANCHEZ REANO (San Felipe), jewelry

• LOA RYAN and TERESA RYAN (both Tsimshian), baskets

• KEVIN SEKAKUKU (Hopi), carvings

• SARAH SOCKBESON (Penobscot), baskets

• TOHONO O’ODHAM COMMUNITY ACTION (TOCA), baskets and diverse art

• LOUIS VALENZUELA (Yoeme), diverse art

• TODD WESTIKA (Zuni), sculpture

• ROSIE YELLOWHAIR (Navajo), sand painting.

Master of Ceremonies: DENNIS BOWEN SR. (Seneca)

Sound Engineer: WILLIAM EATON of Wisdom Tree Music

Northern Drum: THUNDER SPRINGS led by Lamon Barehand (Hopi-Pima)

Arena Director: ERIC MANUELITO (Diné)

11:00 a.m. OPENING CEREMONY

The First Nations Warriors Veterans’ Group, led by Mike Smith (Diné) will present the colors. Jay Begaye (Diné) will sing the Native American Flag Song. Jaclyn Roessel (Diné), Heard Museum Director of Education and Public Programs, will provide a blessing for the event. Fair Chair Shelley Mowry and Heard Museum Director and CEO David Roche share welcoming remarks.

12:00 p.m. DINEH TAH’ NAVAJO DANCERS

This troupe from Albuquerque shares dances and songs to educate the public about Navajo culture.

1:00 p.m. R. CARLOS NAKAI QUARTET

Led by Nakai, a Navajo-Ute flute player, the quartet features Amo Chip, Mary Redhouse (Navajo), and Will Clipman.

2:00 p.m. G ertieNtheT.O.BOYZ

This all-Tohono O’odham band, led by Gertie Lopez, plays waila—chicken scratch—a fast-paced blend of Indigenous and norteño musical styles.

3:00 p.m. MOONTEE SINQUAH

Champion hoop dancer and leader of the First Nations Intertribal Singers and Dancers brings blues and rock influences to intertribal drumming.

11:00 a.m. DINEH TAH’ NAVAJO DANCERS

12:00 p.m. R. CARLOS NAKAI QUARTET

1:00 p.m. G ertieNtheT.O.BOYZ

2:00 p.m. MOONTEE SINQUAH

3:00 p.m. TBD

3:50 p.m. CLOSING CEREMONY

TONY DUNCAN

(Apache-Arikara-Hidatsa)

This champion hoop dancer is also a premier Native American flute player. Join Tony in his Flute Circle on the museum grounds throughout the day.

VIOLET DUNCAN (Plains Cree-Taíno)

The former Miss Indian World shares storytelling and crafts for children. Storytelling times are every hour on the hour, 10:00 a.m. through 2:00 p.m., in the lobby of the Steele Auditorium.

SATURDAY & SUNDAY

11:30 a.m. TONY DUNCAN (Apache-Arikara-Hidatsa) and DARRIN YAZZIE (Diné)

Melodic and subtle, this duo features Native American flute and acoustic guitar.

12:00 p.m. CLARK TENAKHONGVA (Hopi)

An acclaimed katsina carver from Third Mesa, Tenakhongva sings and drums time-honored Hopi songs and his own original compositions.

12:30 p.m. AARON WHITE (Navajo-Ute)

Known for his acoustic guitar playing, GRAMMY-nominated White also plays keyboard, Native American flute, and percussion.

1:00 p.m. ROMAN ORONA (ChiricahuaLipan Apache-Taos-Isleta-Yaqui)

Orona infuses Apache roots music with meditative, house, and hip-hop influences.

1:30 p.m. JAY BEGAYE & SONS (Diné)

Begaye mixes Diné singing with Northern style powwow drumming. His sons are rising stars in hoop dancing.

2:00 p.m. JONAH LITTLESUNDAY (Diné)

Littlesunday strives to bring Native American flute to a wider audience.

2:30 p.m. KENNETH COZAD (Kiowa)

Coming from a prominent musical family, Cozad brings Southern style singing and drumming to the Heard Fair.

‹ BEST OF SHOW & BEST OF POTTERY: Jody Naranjo (Santa Clara Pueblo) and Glendora Fragua (Walatowa [Jemez] Pueblo), Pueblo Luck, 2016, ceramic pot.

BEST OF BASKETS: Sarah Sockbeson (Penobscot), Giant Brown and Black Vase, 2016, brown ash, sweetgrass, deer antler.

BEST OF DIVERSE ART

FORMS: Kenneth Williams

Jr. (Northern ArapahoSeneca), Orlando Dugi (Navajo), and Benjamin Harjo Jr. (Absentee

Shawnee-Seminole), She Holds the Stars, 2016, handpainted, hand-beaded silk dress with beaded handbag featuring Swarovski crystals and Italian red coral. Collection of the Heard Museum, gift of William and Ellen Taubman.

BEST OF JEWELRY & LAPIDARY: Ernest Benally (Navajo), Squash Blossom Necklace, 2016, silver, turquoise, coral.

BEST OF PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS, GRAPHICS, PHOTOGRAPHY: Marla Allison (Laguna Pueblo), Labor of Love, 2016, acrylic on canvas.

JANIS LYON. Longtime collector of Native American jewelry, pottery, and artifacts, along with her husband, Dennis Lyon.

NORMAN L. SANDFIELD. Internationally known collector and antiques dealer based in Chicago, Illinois. He co-curated two Heard Museum exhibits and coauthored the accompanying catalogues.

KENNETH WILLIAMS JR. (NORTHERN ARAPAHOSENECA). Beadwork artist and manager of the Case Trading Post at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe. He won the 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market Best of Show award and Best of Classification in 2016 for his contribution to a collaborative work.

JILL GILLER. Gallery owner, Native American Collections, Denver, Colorado. She frequently judges American Indian art markets.

GARTH JOHNSON. Curator of Ceramics at the Arizona State University (ASU) Art Museum and ASU Art Museum

Ceramics Research Center, Tempe, Arizona. He is also an artist, writer, and educator. Johnson currently serves on the board of the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts (NCECA).

DWIGHT P. LANMON. Has published several books on Pueblo pottery, including The Pottery of Zuni Pueblo and The Pottery of Acoma Pueblo. Lanmon was CEO and director of the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library in Wilmington, Delaware, and the director and a curator of European glass at the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York.

KATHLEEN ASH-MILBY (NAVAJO). Associate curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) George Gustav Heye Center, New York. She co-curated the exhibition Kay WalkingStick: An American Artist that traveled to the Heard Museum in 2016. She has written numerous publications.

GILBERT VICARIO. Chief curator, Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona. He has curated several exhibits, including Made in Mexico and Field, Road, Cloud: Art and Africa.

STEVEN J. YAZZIE (NAVAJO-LAGUNA).

Interdisciplinary artist. His work has been in numerous regional, national, and international exhibitions, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; NMAI George Gustav Heye Center, New York, as well as the Heard Museum.

JOHN BLESSINGTON. Katsina figure collector and member of the Heard Museum Council and Heard Museum Guild.

DOUG HYDE (NEZ PERCE-ASSINIBOINECHIPPEWA). An award-winning sculptor of national and international acclaim. Phoenix Home & Garden named him “Master of the Southwest,” and he is a fellow of the National Sculpture Society. His bronze, Tribute to Code Talkers, is a Phoenix landmark. The Heard Museum has several of his works, including Intertribal Greeting.

SUSAN H. TOTTY. Owner, Blue Sage Gallery, Cave Creek, Arizona, and author of The Dedicated Collectors: The David and Barbara Wilshin Collection

JED FOUTZ. Owner, Shiprock Santa Fe Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico. He is a fifth-generation trader who grew up on the Navajo Reservation and has a deep interest in Native American art, especially textiles.

BILL HOWARD. Longtime collector and scholar of Native American textiles. Howard is a member of the Heard Museum Council.

CAROL ANN MACKAY. Collector and Heard Museum life trustee. She is a noted scholar of Navajo textiles, and the Heard Museum has featured her significant collection in two exhibitions.

CHRISTINA E. BURKE. Curator of Native and Non-Western Art, Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma. She has contributed to several traveling exhibitions and the award-winning, online exhibition, Lakota Winter Counts. She has also served on the board of Native American Art Studies Association (NAASA).

JOHN P. LUKAVIC, PHD. Associate curator of Native Arts, Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado. He curated Super Indian: Fritz Scholder, 1967–1980 and co-edited the exhibition catalogue. He wrote his doctoral dissertation on Southern Cheyenne moccasin makers.

GAYLORD TORRENCE. Senior curator of American Indian Art, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. He wrote The American Indian Parfleche: A Tradition of Abstract Painting and curated The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, which opened in Paris, France, and traveled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

NANCY J. BLOMBERG. Chief curator and curator of Native Arts, Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado. Blomberg has organized dozens of exhibitions and has overseen a complete renovation of the American Indian galleries at the Denver Art Museum. She has published extensively, including her major publication, Navajo Textiles: The William Randolph Hearst Collection.

JERRY COWDREY. Longtime collector of American Indian art. Cowdrey is a docent at the Tucson Museum of Art, Tucson, Arizona; the Desert Caballeros Western Museum, Wickenburg, Arizona; and the Heard Museum.

LARRY DALRYMPLE. Collector of Indian baskets for more than two decades. An educational consultant, Dalrymple has authored two books, Indian Basketmakers of California and the Great Basin and Indian Basketmakers of the Southwest: The Living Art and Fine Tradition.

JESSICA R. METCALFE, PHD (TURTLE MOUNTAIN CHIPPEWA). Owner of the Beyond Buckskin Boutique, Belcourt, North Dakota. Metcalfe hosts the website Beyond Buckskin, which focuses on all topics related to Native American fashion.

DENNITA SEWELL. Curator of Fashion Design, Phoenix Art Museum. She also served as the collections manager at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute in New York City. She is in the process of developing a new fashion degree program for ASU School of Art, Tempe, Arizona.

KAREN KRAMER. Curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. Kramer has helped produce ten major exhibitions on Native American art and culture. She recently curated Native Fashion Now and Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art.

MARK BAHTI. Gallery owner, Bahti Indian Arts, Tucson, Arizona, and Santa Fe, New Mexico. He has written numerous books about American Indian art and jewelry. He serves on the board of the Tucson Indian Center, the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) Foundation, the Amerind Foundation, and Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA).

WARREN MONTOYA (SANTA ANA-SANTA CLARA PUEBLOS). Artist and owner of Rezonate Art, as well as executive director of Rezilience Indigenous Arts Experience. He is a painter, illustrator, photographer, graphic artist, and fashion designer, based in Bernalillo, New Mexico.

ELLEN TAUBMAN. Curator, Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation, a three-part exhibition series featuring the cutting edge in contemporary Native American and Inuit art. She is currently organizing an exhibit called Redefine, scheduled for spring 2019 at the Heard Museum. She previously served as the vice president at Sotheby’s in charge of American Indian, Inuit, and Oceanic art.

Please refer to the map for specific locations.

Volunteers are stationed at designated ASK ME booths throughout the campus to help you locate artists’ booths, find restrooms, preview the cultural performance schedule, and provide directions and answer general questions.

Money machines are located throughout the campus as well as in the museum bookstore. Credit cards are widely accepted by fair artists and in the museum, including the gift shop, café, and bookstore, and at the fair merchandise booth, food court, and admissions.

A wide variety of food options are available throughout the museum grounds. The museum café has a special Heard Fair weekend menu, and reservations are accepted. For a more casual, quick meal, take advantage of the barbecue menu featuring burgers, hot dogs, and more with tented seating available in the Food Pavilion. Or choose a light lunch or snack from the museum café grab ’n’ go. Frybread is a popular option with several booths selling this beloved treat. For a quick pick-me-up snack, grab a gelato or a bag of kettle corn. Beverage stations located throughout the campus will be selling bottled water as well as soft drinks.

Specially designed fair merchandise is available for purchase at the merchandise booth located in the courtyard close to the Amphitheater Stage. Don’t miss the opportunity to take home commemorative T-shirts, posters, and tote bags.

A professionally staffed first aid station is located near the fair entrance at Encanto Boulevard and Central Avenue, on the north side of the museum grounds between the D and E booths.

A UPS packing and shipping booth is conveniently located close to the Central Avenue fair entrance, making it easy to send gifts to friends and family and to ship your purchases home.

Separated by thousands of miles, Northern and Southern Athabascan peoples can still understand some of each other’s languages. The Heard Fair is a place where they come together to rekindle ancient connections.

BY MARTINA DAWLEY, PhD (HUALAPAI-NAVAJO)AGO, the Southern Athabascan peoples split off from their Northern Athabascan kinfolk in Western Canada and the interior of Alaska and migrated south. Some settled in along the West Coast, but the majority moved further south and inland to become the Navajo and Apache peoples of the Southwest and Southern Plains.

Set near Navajo and Western Apache lands on O’odham land, far from Alaska and First Nations lands, the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market has become something of an Athabascan reunion, a place to celebrate their shared stories.

These stories, also known as the oral tradition, are the cultural values and histories that complement the written word. They are passed on to maintain and preserve their people’s histories, beliefs, and technological ingenuities. For many artists, oral tradition plays a significant role in cultural preservation. The stories inspire their art.

Indigenous artists worldwide are revered for their craftsmanship, creativity, and culture. From long lineages, they have taken it upon themselves to share their people’s histories and knowledge through art. These Athabascan artists are perfect examples of cultural stewards.

The name Athabascan |ath-a-bas-can| comes from the Cree word Aðapaskāw, pronounced \ahdhapask-a-w\. It describes the shallow end of a lake “where there are plants distributed in a net-like pattern” or “grass here and there,” and has since become the name of a large lake at the border of Saskatchewan and Alberta in Canada, Lake Athabasca. The linguist Edward Sapir first identified the Athabascan language family, which includes Indigenous languages spoken in Alaska, Canada, and the mainland United States’ Northwest and Southwest regions. For many Indigenous communities, the spoken word is a strong identity qualifier; therefore the Northern Athabascans acknowledge their relationship to the Navajo and Apache through language. More than 40 languages fall within the Athabascan language family, with Navajo being the most widely spoken.

Keep in mind that the Indigenous groups did not always refer to themselves as Athabascan; instead they had their own names that usually translated to “the People” in their languages. This holds true for the names Apache, Ingalik, and Navajo, who refer to themselves as Inde, Deg

Hit’an, and Diné, respectively—all translated to mean “person, People from here, and/or the People.” The Kaska Dena refer to themselves as the Dena or Dene, meaning “the People.”

Artists Glenda McKay, Ingalik Athabascan from Alaska; Sho Sho Esquiro, Kaska Dena-Cree from Canada; Lindsey Shakespeare, Mescalero Apache from New Mexico; and Penny Singer, Navajo from New Mexico and Arizona, share stories of ceremony, family, loss, matriarchs, and survival.

BORN IN ANCHORAGE, Glenda is Deg Hit’an or Ingalik Athabascan. Ingalik is a Yup’ik term that generally refers to “any other Indian.” She is an award-winning beadwork artist and doll maker. She shares her people’s culture and history through her dolls and says, “All the dolls have a story as [to] why they were made. Either they are made [because] of someone I met through life that’s touched my heart or stories that were told to me from my culture.

“I try to use all the Indigenous materials of Alaska just like they used hundreds of years ago,” Glenda says. “I even have my own ivory needles.1 If I had to put down in writing what every doll meant, it would be a full book of my history.”

Growing up, Glenda heard stories about the Russian hostilities in her region. “The Russians hit the coastal areas. The Athabascans gathered in Denali and made weapons for two or three years, and they had what they call the War of Kenai,” which was between the Russians and Native Alaskans in 1797. Glenda continues, “The Athabascans attacked the Russians and ran them out of Alaska, and that is when they didn’t want anything to do with us. They called us headhunters, which we are not.

“My grandma thought that the Russians would come back and invade us, even though it had been a long time,” the artist continues. “We learned how to snare animals, small squirrels and rabbits and such, and how to skin and brain tan.” Her grandmother taught her “all the medicinal plants, what we could eat, and what we couldn’t eat. [She] just wanted to make sure we could survive.”

McKay is proud of her grandmother’s endurance and strength on the famous Iditarod trails. Iditarod \hidedhod\ is a Deg Hit’an and Doogh Qinag word meaning “distant” or “distant place.” “Grandma did the original Iditarod long before” it became a competitive dog sledding race, says Glenda, because she delivered “medicine and everything else by dog team. She’d run medicine and supplies up and down the rivers in the summer on rafts and dog team in the winter.”

BORN AND RAISED IN THE YUKON, CANADA, Sho Sho Esquiro is Kaska Dena and Cree. She is a fashion designer who began sewing at a young age and puts her cultural attributes into each piece. “When I was a kid, there was snow for eight months out of the year,” says Esquiro, “so I learned how to sew from my mom and my aunties as a young child. We never had … TV or anything like that.” Instead, her artist mother encouraged Sho Sho to create and placed a strong emphasis on meticulous work. “It is very important to sew quality things, such as moccasins or hats or gloves. When you sew something for somebody, and outside it is 30 to 40 degrees

below and they are out on their Ski-Doo, they could lose a finger if you haven’t sewn something with care and quality.”

Sho Sho was adopted as Tlingit in her youth and learned many of their customs, but felt the need to return to her father’s people. “It wasn’t until I was probably in my late teens that I became curious about my blood dad’s family, my tribe, so I went back there,” she explains.

“If you were to Google Kaska Dena art or Kaska Dena clothing, you’d probably find my stuff come up and my uncle’s, too. There are not a whole lot of things that I can reference,” Sho Sho says. “It’s left me, as an artist, an open area to be experimental. There are not a lot of people that can tell me, ‘That’s not how we did it’ or ‘that’s not Kaska.’ The reality is I’m a Kaska woman making things in survival of Kaska art.

“I want to honor the ancestors, because there are certain things we believe; like you don’t sew angry or you will put that into your sewing.” She’s aware of her responsibilities to her community. “I feel that anything I do is our legacy that I am leaving.”

Sho Sho says, “Native fashion has been around forever,” and her idea of cultural preservation is expressed through her ancestor’s sewing. “There is a beautiful Dena dress in the Alberta Museum that is more than a hundred years old, and it’s just exquisite! So, it’s just crazy when people tell me what I am doing is innovative. I’m just doing what my people have been doing for thousands of years. I’m just privileged to have other materials available.”

THIS MESCALERO APACHE ARTIST draws inspiration from her culture’s origin stories for the dolls she creates, especially the Mescalero Gaa’he or Crown Dancers. As a woman, Lindsey was initially told that she could not replicate the Gaa’he dancers in any form because it is an all-male society. She respectfully agreed, but through her family and a head caretaker of one of the six Crown Dance groups, she was granted permission to create her dolls. She tells the Mescalero Gaa’he origin story:

Mescalero [Apache Crown Dancers] hardly ever go to schools or museums to show, because they only come out during the nighttime. In Three Rivers, there was a cave. There was a blind man and a crippled man. They [were] placed in that cave because, once again, that whole tribe was on the move running away from the enemies. They

“I WANT TO HONOR THE ANCESTORS, BECAUSE THERE ARE CERTAIN THINGS WE BELIEVE; LIKE YOU DON’T SEW ANGRY OR YOU WILL PUT THAT INTO YOUR SEWING.” —SHO SHO ESQUIROSho Sho Esquiro (Kaska Dena-Cree), Silk Dress, 2013. Model: Pernella Alexis Portillo. Make-up: Elizabeth McLeod. Hair: Amber Rosé. Photo: Anthony Thosh Collins (Akimel O’odham-OsageSeneca-Cayuga).

were in there; all of a sudden they heard these noises, these chants, the songs. And for four nights the crown dancers came out, blessed them, sang to them, and they got healed, cured. So that guy got to walk again. That guy got to see again. And they caught up to the rest of their [community] members, and they were wearing all these fine, buckskin clothes, outfits, and had the finest bows and arrows, and they said this is what the [Gaa’he] wore, this is what they sounded like, this is what they carried, so that is how the origin story of the Crown Dancers came to be. So it is somewhere in Three Rivers [mountain] side.

NAVAJO FASHION DESIGNER AND PHOTOGRAPHER

Penny Singer did not grow up on the reservation; instead her family moved every four years since her father served in the air force. She did, however, recognize that home was with her grandmother, her family’s matriarch, who lived in the Navajo Nation. A cultural trait of Athabascan peoples is having matriarchal societies.

“I’m pretty much an urban Native,” Penny volunteers. During her father’s temporary assignment, the family would move to the reservation in Teec Nos Pos, Arizona, and live with Penny’s grandmother for a few months at a time. “Then he would transfer for four years to an air force base, so we would settle for four years, then go back home on the reservation.” Her parents didn’t speak Navajo to her as a young child, so she is not fluent. “Being young it

was hard. I spoke English and on the reservation all the kids talked Navajo.” The family moved to Japan at one point. “My childhood was not your average Sesame Street toddler years.”

The transition from city to reservation was abrupt, “because back then there was no water, no electricity. It was living on the rez: we had to do everything by hand. I’m grateful that they did that,” Penny says, because she now knows how to live without running water or electricity.

SO, what will these four Athabascan women bring to this year’s Heard Fair?

Glenda McKay says, “I will be bringing a new doll named Athabascan Fiddler. After Russian contact, we loved the music and we made our own fiddles and went from village to village and played.” She studied the playing posture of her friend, a prominent violinist, and studied his Stradivarius for her

fiddle. “The doll has a sealskin tuxedo, modeled after Everett Zlatoff-Mirsky.

“I used polar bear hair for the string on the bow; the bow is made of walrus ivory with whale baleen inlays,” Glenda explains. The miniature violin’s tuning pegs actually turn. “They were so tiny to carve out of baleen, I probably carved about 24 of them just to have four finished pegs. It took me about a year to make the piece.”

Sho Sho Esquiro’s collection will honor her grandmother, Grace McCallum, who, the designer says, “was the most significant person in my life as far as fashion. She was so fashionable.” Her grandmother suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, so Sho Sho helped cared for her for the final nine years of her life.

“Her favorite thing to do in the world was to shop, so we would go to secondhand stores,” recalls Sho Sho. “One time we went into a fabric store and found raw silk. She loved it! She wanted me to have so many meters of it, and we ordered it. I just kept it and never used it. So, that fabric was the basis and inspiration for this whole collection,” which began last year with her award-winning Heard entry (see page 17). “It has lynx paws at the top of the shoulder and it has that fabric in it. On the back, beaded in 24-karat gold, is my language that says, ‘Remembering and honoring our mothers and grandmothers.’ It was the first piece that defined the whole collection for me.”

The last year has been challenging, and Sho Sho admits, “for this collection, I don’t know where I’d be if I didn’t sew my emotions away. It’s just a reflection of my grandma, and I know if she was here, she would love it.”

Lindsey Shakespeare is considering incorporating photography into her work. Last summer she was asked to create dolls to be used for trophies, which she plans to build upon. “I was asked to make them for second place, [but] they saw what they came out to be, and they were promoted to firstplace trophies.” Each of the trophy dolls “comes with a crown dancer. You can always tell the first crown

AtaumbiMetals.com

Heard Museum Guild Fair & Market March 4 & 5, 2017

Booth K-04

dancer because of the pollen bag. The young maiden and the medicine people would bless the crown dancers before they would go out and dance. There is a total of four crown dancers and then two clowns.” Six dolls became trophies, but Lindsey’s bringing the seventh doll to the Heard Fair. “Number eight is still in the works.”

“I plan on bringing a Navajo collection,” announces Penny Singer. “I’ve been working on a new design—a very simple design that people can distinguish me as the Navajo woman. I am planning on bringing jackets, maybe some skirts, and blouses. I might do some research and try and make a piece to tell a story about the Athabascan, to the Apache, to the Navajo. I have ideas.” She continues, “The Heard Museum was where I first debuted my jackets. I am thinking of collaborating with a good friend of mine, John Whiterock from Tonalea, Arizona. I was going to have him create some clay buttons with Navajo designs on it.”

THE KINSHIP felt by Athabascan-speaking peoples lives on today. As Penny says, “I believe we are all one, no matter the science and everything. I could just see the resemblance in the way we think of Mother Nature. We are close to the earth, and we are just very humble people.” ?

Kenneth Johnson’s jewelry coming straight out of a newly opened treasure chest. Whether made from gold, silver, platinum, palladium, or repurposed coins, inlaid with rubies, diamonds, or other fine gemstones, it’s intricate, sophisticated, and stunning. His important gorgets and statement bracelets have graced the likes of Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Sandra Day O’Connor, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, chiefs of Oklahoma tribes, actors such as Jennifer Tilly, and even baronesses and kings of other countries.

Johnson (Muscogee-Seminole) has been a professional artist for almost 28 years, but didn’t always know he would follow this career path. After spending his childhood in Oklahoma (Tahlequah, Tulsa, Wyandotte, Norman, and Oklahoma City), he thought he would be an engineer, so he eventually transferred to the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque to pursue this field.

It was in New Mexico that his trajectory changed permanently. He met Choctaw silversmith Johnson Bobb and, after a few months of studying with him, left the engineering track to pursue jewelry and metalsmithing. Johnson also took as many classes as possible to learn about

the technical side of jewelry making. He dove in to diamond setting, platinum casting, engraving, inlay, and more, eager to make his designs come to fruition.

Johnson’s designs and overall aesthetic have remained recognizable and distinct, even as they’ve evolved. While Johnson never became the mechanical engineer he thought he might be at one point in his life, the precision and craftsmanship

associated with engineering are ever present in his work. Surfaces are almost always stamped and/ or engraved and overflowing with designs. “I tend to fill up negative space. I have to resist filling every space with detail,” he says with a smile. “I like the use of materials with patterns. I look at every piece as a canvas to fill.”

The finished work is precise and elegant. Sometimes it’s completed with

the help of high-tech CAD/CAM technology. Johnson is quick to point out that using computer-aided drafting came with an eight-year learning curve, meaning computer technology doesn’t automatically make the work easier. Rather, it’s just another tool for the virtual jeweler’s bench. “I am fortunate to now be able to pair CAD design with hand techniques. I understand what I’m making on the screen because I understand how to make it by hand. It’s complementary.”

Adept at balancing the tension between the old and new, he is well known for using Mississippian-era Mound Builder designs in his pieces (named for the Native American cultures that built colossal earthworks or mounds between 800 and 1400 CE that span from present-day Oklahoma

to the Atlantic Coast). But this wasn’t always the case. As one would expect, the work has morphed and matured as Johnson has come into his own as an artist, exploring subject matter and absorbing ideas that aren’t always taught

a classroom setting.

“I had a desire to build upon Southeastern designs, but I had to learn within the context of the Southwest. I had to develop the characters of my own ‘Southeastern alphabet,’ which includes the iconography of the old Mississippian pottery and shell designs,” Johnson notes. One

will see spiders, woodpeckers, turtles, and more in his work, drafted in much the same style as the Southeastern art of the past. Johnson’s work, in large part, has been influenced by a Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA) fellowship that allowed him to travel to the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and later a residency award at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian George Gustav Heye Center in New York City. These experiences gave Johnson the chance to carefully study the ancient Mississippian cultural

artifacts and art that inspire him, providing depth and context—and lack of context—to his understanding of the work.

“The fellowship and residency granted access to collections and gave me more time to be up close with things,” Johnson says. “When I studied the work of the ancients, there was such attention to detail. I could tell if someone was right handed or left handed, who used broader strokes, who liked finer details. I could follow an artist through their lifetime of work, and I enjoyed that. In contrast,

I was deeply affected during this museum journey, seeing warehouses of ‘us’—rows and rows and rows of our things. It was disheartening to see that we, our ancestors, had been dug up and stored and collected. But, what I brought from that was we are still here creating, speaking through our art now.”

Constantly trying new things, honoring the “living arts” as he says, Johnson has been a regular collaborator, student, and explorer during his career. He made the RAIN jewelry line for Cochiti Pueblo artist Virgil Ortiz in 2012. Two years later, he was one of several Native American artists selected to create immersive, edgy content for the New Mexico Arts Experimental Dome Project. Last fall he completed a class on repoussé with a master silversmith from Bulgaria and is already turning out beautifully chased pieces with Mound Builder designs that seem created specifically for this technique. He and Hopi jeweler Emmett Navakuku will reveal a repoussé embellished piece at the 2017 Heard Fair—an art market Johnson’s enjoyed participating in for almost 22 years, missing it only once or twice.

When he isn’t learning new techniques or making new work, Johnson gives back to his communities. He has taught jewelry at workshops for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Council House, judged art competitions for markets such as the Red Earth Festival, served on SWAIA’s board of directors, and more. Most recently he joined poet Joy Harjo (MuscogeeCherokee) and textile and basket artist Sandy Fife Wilson (Muscogee Creek) and founded the Mvskoke Arts Association, Inc., a nonprofit organization based in Oklahoma that exists to curate important art and promote Muscogee Creek and Seminole arts and culture on the local, regional, national, and international level.

While the organization is still in its infancy, it has already developed a young Native women’s writers program and the Dugout Canoe

Project. Because of the canoe project, Johnson can now add canoe paddle carver to his résumé. He helped create the Genesis paddle, which sold at the NAYA Family Center Auction and Gala in Portland, Oregon, for $3,000 in 2016. While it may seem unusual that a Santa Fe-based, MuscogeeSeminole artist carved a canoe paddle out of a tree from Alabama, it actually makes perfect sense.

Coming from the same tree that the Muscogee Nation created their first canoe with since being displaced more than 180 years ago, the five-footlong paddle was initially cut out by Muscogee Creek canoe carver John Brown, who sent it to Johnson to design. Johnson then engraved it with Muscogee cultural imagery. A fuco (pronounced “foo-joe,” Muscogee for duck) adorns the piece, representing the paddle’s ability to glide through the water, while pink mussel shell and copper inlay create subtle accents. Johnson and Brown donated the piece as an act of reciprocity after several Northwest tribes extended

an invitation to pull with their canoe family during the 2016 Canoe Journey in the Pacific Northwest. In February 2017, Johnson and the Mvskoke Arts Association plan to travel in the opposite direction to collaborate with Seminole artists in Florida and carve canoes from cypress trees. While Johnson’s career achievements and experiences continue to grow, past highlights include a one-man exhibit at the Creek Council House Museum in 2007 and being chosen for the Museum of Arts and Design’s Changing Hands: Art Without Reservations 2 exhibit in 2006. Johnson also received the “Most Creative Use of Stampwork” jewelry award at the 2005 Santa Fe Indian Market and the 2003 Grand Award at the Red Earth

Festival. In 2001, he was Tulsa Indian Art Festival’s featured artist. Even after all of these accolades and awards, Johnson says the best thing about being a jeweler is the connection that it brings. He looks thoughtful when he says, “The work I do makes people happy. It elicits a positive response. I get to commemorate and be associated with positive events.” And just like the skilled, ancient artists who have inspired him, Johnson will surely be remembered for his own masterpieces for years to come. ? KENNETHJOHNSON.COM

“WHEN I STUDIED THE WORK OF THE ANCIENTS I COULD TELL IF SOMEONE WAS RIGHT HANDED OR LEFT HANDED, WHO USED BROADER STROKES, WHO LIKED FINER DETAILS.”Gorget, 2014, pearls, silver coins from 1954, collection of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

ATHLEEN WALL’S CERAMIC AND BRONZE SCULPTURES have garnered her a loyal following, as has her warm, outgoing personality. She has met with immense success in the Native art market circuit. For instance, she recently won Best of Show at the last Eiteljorg Indian Market and Festival. But there is so much more to her artistic practice than can fit into a ten-by-ten-foot booth.

“Many people” in her pueblo, Wall says “know how to make pots, but not everyone loves it” or has the passion for wholeheartedly pursuing ceramics. Her mother, Fannie Loretto (Jemez), gave her some basic lessons, but mainly she learned through observation. She still digs and prepares her own clay and earth pigments, demonstrating how significant materials and processes are in Native art.

“The materials I use in the body of work are extremely important to me. I have been working in traditional clay from my reservation for the past 24 years,” Wall says. “I dig my clay in a clay pit that was shown to me as a young girl by my mother. I also dig volcanic ash in the same spot that I have been collecting ash my entire career.” She’s proud to continue the sustainable artistic processes that her mother, grandmother, and

great-grandmother performed while she developes her own conceptual and aesthetic visions.

When she wanted to branch out and have a solo exhibit, Wall organized and underwrote it herself. She approached the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center about hosting Celebrating Native Legacies: Works in Clay by Kathleen Wall, which showed in 2009 and 2010. The premise of the show was to explore the tribal cultures of Wall’s family and friends.

“When I say family, I’m not just talking about my children and husband,” she says. “I have a very large extended family that spreads out to more than eight different Pueblo tribes, five different tribes across the United States, and other nationalities, and with this diverse crowd come many different cultures and traditions that I find intriguing.”

The artist lives in and is enrolled at Jemez Pueblo, but her heritage and those of her three children are much more complex. Her father, the lawyer, judge, and professor Stephen Wall is Seneca and White Earth Ojibwe. Her husband Michael Chinana is Jemez and Cherokee Nation (from the Wildcat family), as are the couple’s children. Wall created more than a hundred artworks exploring these cultures and made the leap from potter to multimedia installation artist. She made figurative sculptures but also ceramic versions of black ash bark baskets and stickball sticks—pushing the medium in counterintuitive directions a la Jeff Koons (a major distinction being that she both conceptualizes and builds the work).

Wall incorporated video and sound into her pieces: a Pueblo adobe building containing video of her relatives in discussion or a hogan with a video of Navajo weaver Pearl Sunrise. She often collaborates with Laguna-Zuni videographer Dale Waseta and traveled to Gila River and recorded an Akimel O’odham troupe dancing. Interviewing tribal members has become integral to Wall’s process.

While the Albuquerque Journal named Celebrating Native Legacies as one of the top five exhibits in Albuquerque in 2009, museum curators were not as quick to take notice. Undaunted, Wall forged her own path. She wanted to add painting to her installations, so she enrolled at the Institute of American Indian Arts

(IAIA), where she had earlier earned her two-year associate’s degree in fine arts but now wanted to complete her bachelor’s degree.

Wall’s first attempt at painting was Core Values, a mural with three ceramic figures, a Pueblo grandfather and his two urban grandchildren, examining and discussing the work. The mural, now in the collection of the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, depicts “100 years of Pueblo policy and how it affected Pueblo people,” as well as yearly events—cleaning irrigation ditches, planting, collecting pollen, harvesting, dances—the cycle of seasons that underpin Jemez cosmology. The grandfather explains to his grandchildren the core Pueblo values: “Love, language, culture, and service, and those give us strength in our every day,” as Wall says.

While at IAIA, Wall developed her first series of installations combining the two-dimensional realm of painting with the three-dimensional ceramic sculpture, Harvesting Tradition. The series explores Indigenous food sovereignty, a subject close to Wall’s heart as a mother concerned about the health of her family. Idea for the series developed over years.

“When imagery or ideas came to mind relating to Harvesting Tradition, I put it in a mental notebook inside my head,” Wall says. She not only celebrates Indigenous food crops, such as saguaro cacti, maize, and wild onions, but also Native hunting practices. One installation, Rabbit Hunter, features a Pueblo man hunting desert cottontails with a throwing stick.

Even though she paints with premade acrylics, Wall adds sand, clay, and powdered mica to alter their texture and finish. She finds painting challenging but keeps pushing herself with large scale, representational landscapes.

To bring this series to the public Wall curated another major solo exhibit, this time at the now-defunct Pablita Velarde Museum of Indian Women in the Arts in Santa Fe in 2014. She gathered a team of friends to install and promote the show, leaving no detail overlooked for Kathleen Wall: Harvesting

A major break for Wall happened last year with the award of a prestigious Eric and Barbara Dobkin Native Artist Fellowship for Women at the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe. SAR provided housing, large enough for Wall, Michael, and their children for three months; studio space; and access to SAR’s extensive collections for research. The fellowship also provided

networking opportunities, with other researchers and artists, scholars, and collectors—so the experience was a mix of frenetic studio work and meeting like-minded scholars, collectors, and art professionals.

At SAR, Wall launched Place, a series of figurative sculptures and landscape paintings about a heretofore-unexplored topic: how Indian names anchor an individual to a specific landmark. Her maternal grandfather inspired this series. His Indian name references a sacred site that is now part of a ranch to which Jemez people no longer have free access. Wall was finally able to identity the mountainous area for which her grandfather was named. She sculpted her grandfather in clay—including his sunglasses (he was blind toward the end of his life)—and painted the mountains on a canvas behind him but also in his clothing, which created a Rene Magritte-esque optical illusion. This play between two and three dimensions united the pieces and visually emphasizes the relationship Native people have to their homelands or other significant, sacred sites.

The very notion of being Indigenous comes from one’s relationship to the land. Merriam-Webster defines it as “produced, growing, living, or occurring naturally in a particular region or environment.”

“I want to explain to outsiders and different people how important place is to Indigenous people,” says Wall. “They don’t understand the connection that a lot of Native people have to land—to an actual place. We don’t have to make a monument on something. We don’t have to make a sculpture on something for it to have significant importance. It just is.”

When SWAIA presented Native artists with the opportunity to show larger works at their Indian Market: Edge exhibit, Wall seized it. Since then, she has been eager to find more venues that will allow her to show her developing series.

“I think almost all booth-art artists have something more in them, but it’s a matter of the opportunity given. We just don’t get the space. We don’t get the opportunity,” says Wall. So, she continues to find her own spaces and create her own opportunities.

“I haven’t fulfilled everything I need to do,” Wall continues. “I want to study other people’s ideas of place and where they connect. It’d be ideal

to go global and work with Indigenous people who are having issues with the land that they live on—either fighting for it or just trying to protect it—and exploring those connections.”

Thoughtfully, she says, “I enjoy making things bigger than me.” ?

America Meredith (Cherokee Nation) is the publishing editor of First American Art Magazine and an independent curator, and printmaker living in Norman, Oklahoma.

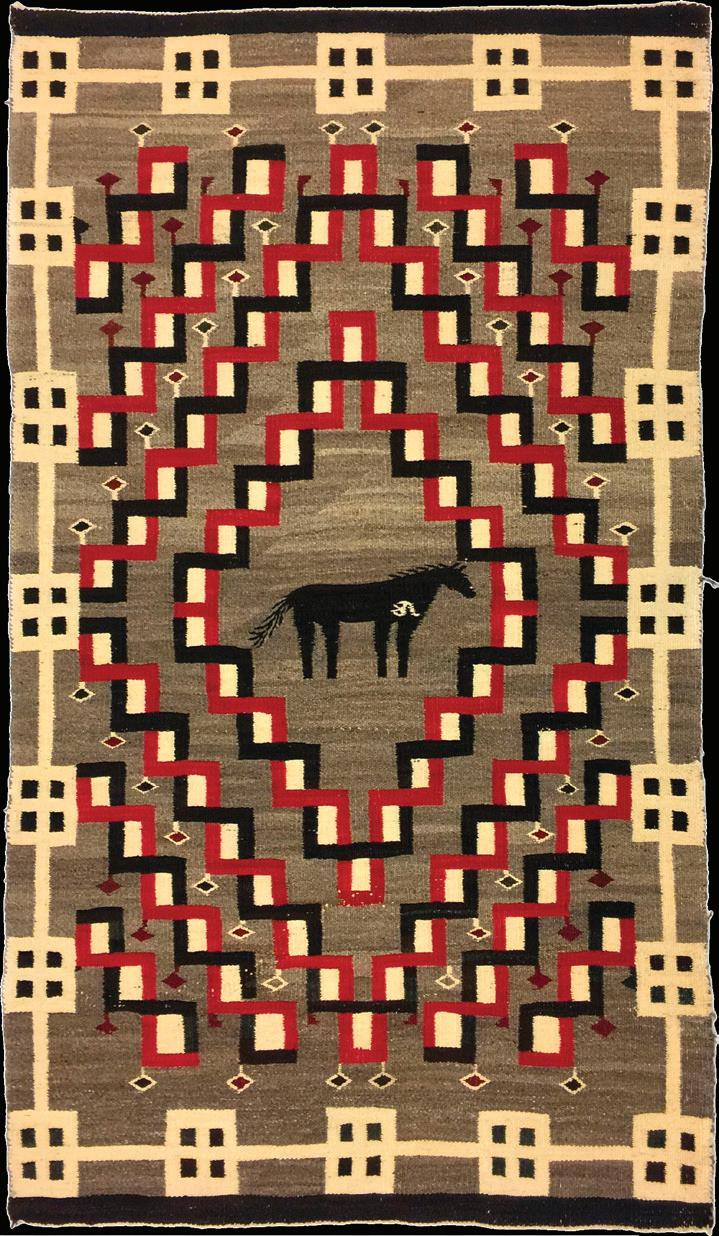

OY KADY is internationally recognized as a Diné master weaver, fiber artist, cultural leader, and mentor. Spend even a little time talking to Kady, and you quickly come to realize how much his apprentice program means to him and how much pride he takes in the young Navajo fiber artists he works with. The cornerstone of his program, which mentors up to six apprentices at a time, is the intergenerational sharing of culture through stories and songs, involvement in the shepherd’s way of life, and learning old and new fiber techniques. There is no time constraint for the apprentices in the program; it is only important that their individual goals are met.

When you turn off US 160 in Teec Nos Pos, Arizona, to visit Kady where he lives on the eastern slope of the Chuska Mountains, you pass the remains of a stone structure that was his childhood home. He plans to rebuild the old homestead into a learning center where weaving and other Diné life way skills can be taught to a new generation. Gentle and soft-spoken, Kady mixes thoughtfulness with a positive sense of humor that keeps his listener captivated in conversation. Kady is tied to his cultural lifestyle on the reservation, but he can also amaze with his travel experiences to South America, Italy, and other countries where he acts as a cultural

ambassador by sharing his knowledge of sheep and weaving. Traces of what he learns during his travels show up in his work. Every one of Kady’s weavings contains a story significant to his life.

His mother, Mary K. Clah, raised the family as a single parent. Kady and his sisters grew up learning how to do every kind of chore to help out, both inside and outside the house. By the age of nine, Kady wove items that could be used at home or sold to help out with family finances. He watched his grandfather weave horse tack and his grandmother weave utilitarian bags and rag rugs from scraps of old, discarded Pendleton blankets. The memory of those rag rugs, sold to tourists at Mesa Verde, later became an inspiration to Kady to go beyond the familiar, trading post-influenced, regional designs and develop his own unique weaving style. He also finds inspiration in his surrounding landscape and the stories and experiences he remembers from his childhood.

Almost 30 years ago, Kady returned home to Teec Nos Pos to help his aging mother with her herd of Navajo-Churro sheep. These sheep came to have a deep meaning for Kady, who knew that the breed formed the basis of the Diné’s pastoral lifestyle and weaving for hundreds of years. The breed serves as an important connection to culture through weaving, songs, prayers, and ceremonies. The Navajo-Churro sheep have always been valued in part because of the many natural variations in the color of their wool—black, grey, brown, white, and even apricot—used in weaving designs. Two separate efforts by the federal government nearly wiped them out, first during the Long Walk in the 1860s and again in the 1930s during a livestock reduction program. Only about 430 NavajoChurro sheep survived on the Navajo reservation by the 1970s.

Commercial yarns and wool from other breeds of sheep used in their absence proved less suited to methods of hand processing and

weaving, and the close connection with the sheep lifeway was mostly lost. In 1977, Dr. Lyle McNeal of Utah State University and his wife, Nancy, founded the Navajo Sheep Project to bring back the nearly extinct breed. Since then, Navajo-Churro sheep have been successfully reintroduced into Navajo communities.

WITH HIS MOTHER’S HELP, Kady learned to raise Navajo-Churro sheep and hand-process their wool into the yarn he came to prize for his own weaving and felting. This experience made him realize he could support himself as a fiber artist. Kady first taught himself each of the regional designs from pictures in a book. These weavings were gifted to his kinfolk and friends. Kady then combined the different regional styles in a single sampler, his first titled weaving—with an important difference. One of the birds has flown from the Tree of Life in the weaving, and is perched on a Two Grey Hills terrace. To Kady’s surprise, The Bird That Got Away won a second place ribbon at a competitive show. That was when Kady began to

see his loom as a canvas and started a career based on weaving in his own creative way. Today, Kady is one of many Diné weavers who push the limits, using old and time-consuming techniques such as hand-processing their wool to create weavings in new styles. He considers this move as a natural part of the ongoing evolution of Diné weaving.

Other types of fibers, including alpaca, llama, silk, cotton, hemp, and metallic, have joined NavajoChurro wool in Kady’s weavings as accents that add texture. Most of his weavings are now custom orders and museum exhibition pieces, although occasionally he has a finished weaving not spoken for at an Indian market. A recent weaving incorporates different species of hummingbirds that Kady encountered during his travels in South America. A customer in Germany consigned the artwork so she could always see the exotic birds on her wall.

Kady explains that both Diné men and women have historically been weavers, even though popular perception is that women primarily weave. The Diné creation story tells that Spider Man set up the first loom,

taught Spider Woman how to weave, and instructed her to teach the community how to weave. The lyrics of some weaving songs explain how to differentiate blanket designs between men and women weavers, with female rain and more subtle designs woven by women and bolder designs, such as lightning and thunder, incorporated by male weavers, according to Kady. Elders often talk about how their husbands, uncles, and brothers were all weavers and how weaving has been a communal responsibility.

Weaving is not the only important aspect of Kady’s life. He has been president of the Teec Nos Pos Chapter, taught Diné cultural classes at local schools, worked with at-risk youth, and taught weaving classes at various colleges and universities. Kady continues to work with tribal elders to learn and share oral history and songs. He is also a member of the Táá Dibéi, the Navajo-Churro Heritage Lamb Presidium. The Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity helped form the presidium in 2006 to promote the market for Navajo-Churro lamb. In all he does, Kady emphasizes self-sufficiency and care of the environment.

KADY IS PASSIONATE ABOUT WEAVING. He believes that passing on his gift of knowledge is important in keeping weaving alive and carrying it forward into the life of the next generation of young Navajos. It also keeps faith with the promise he made his mother before she died to pass on the Diné lifeways she and his other relatives and community members had taught him.

Kady’s goal for his first group of apprentices was to help them understand that weaving is still alive and

relevant to their lives. It quickly became clear that the apprentices would not only learn from Kady and from each other but would also share new knowledge with Kady. One of his key goals for the program was recently realized when some of his apprentices decided to weave a blanket using older customary techniques and elements to represent and safeguard a fellow apprentice who was having a ceremony performed for him. Weaving for a particular individual and occasion represents an important Diné practice distinct from weavings made for sale at art markets.

Kady’s apprentices are a common sight at events on and off the reservation. Their energy and hard work help highlight the longstanding cultural connection between the Diné people and the Navajo-Churro sheep. At the annual Sheep is Life Celebration on the Diné College campus in Tsaile, Arizona, apprentices participate in workshops and demonstrations on wool carding, spinning, dyeing, weaving, and felting. Kady is a former director of Diné be ´iiná, Inc. (DBI), a major sponsor of the celebration and force in the reestablishment of the Navajo-Churro breed. Throughout the Navajo Nation, apprentices participate in wool-processing workshops and in spin-off events, informal meetings for community members to share their knowledge. Kady has taken his apprentices to visit museum collections in Arizona and New Mexico, where they study work by earlier Diné weavers. Apprentices also help Kady herd his sheep 22 miles up a mountainside to their summer pasture and back.

Proving the success of Kady’s program, his first apprentices are now accomplished artists themselves. As established weavers, they have a duty to share their knowledge and inspiration with others, as well as consult with Kady. These talented young men are now working with their families and communities to identify projects they can help with and individuals they can teach. Three members of his first group of apprentices, Eliseo Curley, Kevin Aspaas, and Zephren Anderson, assisted Kady with the Heard Museum Prepare for the Fair series leading up to the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market, where they demonstrated their weaving skills.

Spend some time visiting with Kady and these apprentices while you are at the fair and you will see firsthand that weaving is not a lost art. Weaving continues to be passed down from one generation to the next through efforts like Kady’s apprentice program.

ELISEO CURLEY first learned to weave when he was just five or six years old. For much of his childhood, he stayed with his grandmother in Red Valley, Arizona, and helped tend her herd of goats. He assisted with shearing, carding, and spinning their wool. When his mother took a weaving class at Diné College, Curley tagged along and watched the action. He soon wove his first piece in a striped pattern. Curley stopped weaving when he attended middle and high school, but after graduation he picked it up again. Starting

with sash belts, Curley soon moved on to weaving horse cinches, felting, dyeing, and creating other fiber arts. He is especially interested in re-envisioning Diné attire. A Diné warrior’s hat is typically made from animal hides stitched together, but Curley constructed one from felted wool. His goal is to build on the past while creating the next wave of fiber art.

Kevin Aspaas learned to weave sash belts from his mother. When he was very young, she wove them to supplement the family’s income. Aspaas remembers his mother warping her loom, taking the children to school, spending her day weaving, picking the children back up, making their dinner, and putting them to bed, only to return to her loom to weave long into the night. On weekends, the family traveled around to sell the sash belts his mother wove during the week. All the weavers Aspaas knew as a youth were women, so he was shy about letting the rest of his family know he wove, until later his uncle informed him that men in his family also wove. At age 10, Aspaas put weaving aside for school and sports, and did not pick it up again until he was a freshman in college, when he took his looms back out and worked from memory. After meeting Kady, Aspaas became serious about weaving and is especially interested in historical clothing of the Diné.

Aspaas is now passing his knowledge on to his six-year-old nephew, who has already learned how to warp his own loom. The idea of being a mentor to his nephew has special meaning for Aspaas; he likes the idea of having more men weaving in his family since his sisters are not interested in learning the art. Weaving has inspired Aspaas to become more deeply involved in Navajo culture and ceremonies. He has learned the weaving songs and how to determine which stories and designs are appropriate to incorporate into his weavings.

Zephren Anderson researches and recreates Diné weaving techniques and styles that predate the Long Walk. An expert tailor as well as weaver, Anderson constructs older styles of Navajo clothing by weaving his own fabrics and is often seen wearing his creations. The apprentice program helps him to reconnect to his historical roots through the language, history, food and land that is contained in Indigenous traditional knowledge These experiences have filled in blanks in stories Anderson heard from his grandparents. The apprentices’ knowledge demonstrates the true diversity of Diné culture. Anderson’s involvement in Kady’s apprentice program taught him much more than he could ever learn from books. He hopes other young Diné will take advantage of Kady’s program.

KADY ENCOURAGES ART FAIR VISITORS to ask the weavers they meet about their work rather than just try to categorize weavings into established, regional styles. Kady believes it is important that viewers recognize the stories embedded in his weavings. As Diné textile arts continue to evolve, more weavers like Kady are emphasizing their own creativity and developing more experimental designs.

Exhibiting in art markets provides emerging artists opportunities to learn and teach others. While they may seem young, these weavers have much to share. Intergenerational exchanges of ideas and techniques are how Diné weaving evolved, in part, and how Kady sees it continuing and growing in the future.

You can follow the journey of Roy Kady’s apprentices on their Facebook page, Diné Master Youth Fiber Artists Mentors, @dineyouthfiber. Zephren Anderson’s re-creation of old styles of Navajo clothing can be seen in his Digital Divide Outfitters album on his Facebook page, @zefrenm. ?

THE HEARD MUSEUM SHOP offers an unparalleled selection of American Indian artwork and will be open during the Heard Fair. On Friday night March 3, and during the day on Saturday, March 4, and Sunday, March 5, artists and dealers will be present to sell artwork and to answer your questions. For times and dates, please inquire at the shop or visit our website at HEARD.ORG/FAIR

• TERRY D eWALD, owner of Terry DeWald American Indian Art, dealer and scholar of antique Native baskets, Tucson, Arizona

• BETSY TURNER , owner of Long Ago and Far Away Gallery, Inuit art scholar, Manchester Center, Vermont

• RAY TRACEY (Navajo), jeweler and silversmith

• JENNIFER CURTIS (Navajo), jeweler and silversmith

• RAY SKEETS (Navajo), leatherwork artist

• MIKE BIRD-ROMERO (Ohkay Owingeh-Taos), jeweler

• CRAIG GEORGE (Navajo), painter

• TONY JOJOLA (Isleta Pueblo), glass artist

• ROSEMARY LONEWOLF (Santa Clara Tewa), potter

• IRA LUJAN (Taos), glass artist

SATURDAY, MARCH 4

10:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

• DOUG HOCKING , Massacre at Point of Rocks

• JACQUELINE SOULE , Arizona, Nevada, & New Mexico Month-by-Month Gardening

• JAN TAYLOR (illustrator), Wild Wisdom: Animal Stories of the Southwest

• MARK BAHTI , Spirit in the Stone: A Handbook of Southwest Indian Animal Carvings and Beliefs

12:00 p.m.–2:00 p.m.

• SCOTT THYBONY, The Disappearances: A Story of Exploration, Murder, and Mystery in the American West

• DIANA PARDUE and KATHLEEN HOWARD, Over the Edge: Fred Harvey at the Grand Canyon and in the Great Southwest

• ROGER NAYLOR , Boots and Burgers: An Arizona Handbook for Hungry Hikers

• DOUG HOCKING , Mystery of Chaco Canyon: A Novel of the American Civil War

2:00 p.m.–4:00 p.m.

• BILLE HOUGART, Native American and Southwestern Silver Hallmarks

• DOUG HOCKING , The Wildest West: An Anthology of Stories about the Southwest in the 1850s & ’60s

• JANET E. TAYLOR , Savvy Southwest Cooking

• CHARLINE PROFIRI , Guess Who’s in the Desert

10:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

• GREGORY M cNAMEE , The Ancient Southwest: A Guide to Archaeological Sites

• DOUG HOCKING , see Saturday’s listings

12:00 p.m.–2:00 p.m.

• JIM TURNER , The Mighty Colorado River: From the Glaciers to the Gulf

• JAN TAYLOR (illustrator), Wild Wisdom: Animal Stories of the Southwest

• JEAN EKMAN ADAMS, Clarence Goes Out West & Meets a Purple Horse

AN EVENT OF THIS MAGNITUDE takes thousands of hours of planning and immense talent and dedication. We are grateful to all the Heard Museum Guild committee chairs and volunteers who so generously make this labor of love a success every year.

2017 INDIAN FAIR & MARKET

I NDIAN FAIR & MARKET CHAIR: Shelley Mowry

ADMISSIONS: Barbara Sparman

ARTIST EXHIBITORS: Lynn Endorf

ARTIST HOSPITALITY: Chuck and Dottie Starnes

BEST OF SHOW (BOS) FASHION SHOW: Sue Snyder, Sara Leiberman, and Mary Ann Fast

BOS LOGISTICS: David Mowry

BOS RECEPTION: Shelley Mowry, Brandon Rogeness, and Julie Sullivan

BOS SECURITY: Sandie Straub

BOOTH RELIEF: Kathie Serrapede

CULTURAL PERFORMANCES: Diane Leonte and Sheila Mehlem

DEMONSTRATORS: Carol Gunn

FOOD AND BEVERAGE: Dave Newark

INFORMATION: Connie Thornton

JURIED COMPETITION: Pat Kilburn and Mary Ann Fast

MARKETING: Susan Kolman and Caesar Chaves

MERCHANDISE: Joel Muzzy and Theresa and John Nesbitt

MONITORS: Sandy Nielsen

NONPROFITS: Carol Gunn

OPERATIONS CENTER: Rod Passmore

PIKI BREAD: Ellen Nelsen

PRE-FAIR TICKETING: Deborah Benoit

PREPARE FOR THE FAIR LECTURE SERIES: Anita Hicks and Sara Lieberman

RAFFLE: Fran Dickman and Louise Wakem

SIGNAGE: Don Montrey

SILENT AUCTION: Susan Kolman

SPONSORS AND AWARDS: IlgaAnn Bunjer

STAGING: Joel Muzzy

VOLUNTEER PLACEMENT: Richard Borgmann

THE BRAINCHILD of Heard Museum founder Maie Bartlett Heard, the Heard Museum Guild, then known as the Heard Museum Auxiliary, began in 1956 as a group of volunteers dedicated to supporting the mission and programs of the museum. The Heard Museum Indian Fair & Market has been a labor of love for the guild since its inception 61 years ago and continues to flourish under the creative inspiration, managerial skills,

thoughtful leadership, and hard work of multitudes of volunteers.

In addition to the Heard Fair, volunteers actively engage in all aspects of museum life. This dynamic and talented group leads gallery tours, promotes sales in the Heard Museum Shop and at Books & More, greets and assists museum visitors, conducts research in our library, designs educational programs, and plans and implements special events and projects, such as the annual American

Officers

PRESIDENT: Mary Endorf

PRESIDENT-ELECT: Sue Snyder

SECRETARY: Mary Ann Fast

TREASURER: Mary Bonsall

PAST PRESIDENT: Susan Kolman

PARLIAMENTARIAN: Delores Bachman

COMMUNICATIONS CHAIR: Diane Leonte

GUILD TECHNOLOGY: Dave Newark

INDIAN FAIR & MARKET CHAIR: Shelley Mowry STUDENT ART COORDINATOR: Reta Severtson

Indian Student Art Show & Sale and note card sales program.

The guild also recruits museum interns through its partnership with Arizona State University’s American Indian Student Support Services. Volunteer roles and schedules are flexible to meet the demands of everyone’s busy lives.

For more information and to join the Heard Museum Guild, visit HEARDGUILD.ORG.

GUILD PROGRAMS COORDINATOR: Kathie Serrapede

MEMBERSHIP SERVICES

COORDINATOR: Judy Pykare

MUSEUM EDUCATION

COORDINATOR: Sheila Mehlem

MUSEUM SERVICES

COORDINATOR: Dee Dowers

NOMINATING CHAIR: Stu Passon

Kristine and Leland W. Peterson, The Rob and Melani Walton Foundation, Inc., and Wells Fargo

MASTERWORK PATRONS:

Dino and Elizabeth Murfee DeConcini, Alice J. Dickey, Kathleen and John Graham, Dr. Marigold Linton and Dr. Robert Barnhill, Jean A. and James J. Meenaghan, Susan and James Navran, Christy Vezolles and Gilbert Waldman, Beauty Beholders, Sue and Judson Ball, Jeanie Harlan, and Merle and Steve Rosskam

CONSERVATION SPONSORS:

Frances and Mark Paper in honor of Carol Ann Mackay

PROGRAMMING AND EDUCATION SPONSORS:

Frances and Mark Paper in honor of Carol Ann Mackay

February 2, 2017–September 12, 2017

Black White Blue Yellow is an immersive, four-channel video and sound installation by artist Steven J. Yazzie (NavajoLaguna-French-Welsh-Hungarian) exploring four sacred mountains that border the Diné (Navajo) people:

• BLACK (North): Dib’e Nitsaa, Hesperus Mountain

February 11, 2017–April 2, 2017

The Heard Museum’s new Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust Grand Gallery opens to the public on Saturday, February 11, 2017.

The inaugural exhibition Beauty Speaks for Us presents more than 200 rarely seen masterworks selected from private Phoenix collections and the Heard’s own collection of more than 40,000 works of art. This will be a true celebration of our community and a turning point for the museum, as it will usher in a new era of excellence. Visitors will see timeless works of art that span generations and cultures in a wide variety of media: pottery, textiles, jewelry, beadwork, functional art, paintings, basketry, and carvings.

The Heard Museum thanks the following sponsors for their generous support.

PRESENTING SPONSOR:

The Kemper and Ethel Marley Foundation

MASTERWORK SIGNATURE SPONSORS:

Carol Ann and Harvey Mackay, Jill and Wick Pilcher, and Anonymous

MASTERWORK BENEFACTORS:

Joy and Howard Berlin, Lisa and Gregory Boyce

Carmen and Michael Duffek, Janis and Dennis H. Lyon, Mary Ellen and Robert McKee, Janet and John Melamed,

• WHITE (East): Sisnaajini, Blanca Peak

• BLUE (South): Tsoodzil, Mount Taylor

• YELLOW (West): Dook’o’oosłíí, San Francisco Peaks

BWBY is a journey and departure to sacred land and space, the source of cultural continuities: Indigenous knowledge, mystery, discovery, fear, connection, and exploitation by contemporary societies. BWBY is a culmination of video and sound documentation that will bring the viewer into the complexities of these geographies in a temporal, conceptual experience designed to touch on the mountain’s symbolic nature residing deep within our human memory.

April 10–August 20, 2017

This exhibit offers a rare opportunity to see firsthand masterpieces by two of the most important and recognizable artists of the 20th century. Bank of America is the Presenting Sponsor for Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, making Phoenix its only North American stop on a world tour.

Thirty-three works by the famed Mexican artists from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection will be exhibited in the newly opened Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust Grand Gallery through August 20, 2017. The Gelmans were Mexican-based European émigrés who befriended the artists. On view will be Self Portrait with Monkeys and Diego on My Mind by Frida Kahlo (Purépecha descent, 1907–1954), and Calla Lily Vendor and Sunflowers by Diego Rivera (Mestizo, 1886-1957).

The exhibit includes more than 50 photographs taken by Edward Weston, Lola Álvarez Bravo, and Frida Kahlo’s father, Guillermo Kahlo, among others. The exhibit also will feature vintage clothing and jewelry from the Kahlo period.

PRESENTING SPONSOR: Bank of America

April 8, 2017–July 9, 2017

Jacobson and Freeman Galleries. This major retrospective of the work of contemporary Oregon artist Rick Bartow (Wiyot-Yurok, 1946–2016) features 115 drawings, paintings, mixed-media works, and sculptures. It spans several decades of the artist’s career, from the 1970s until just before his death in April 2016. Jill Hartz and Danielle Knapp, both of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA) at University of Oregon curated this traveling exhibit. Patron Support is provided by Howard Mekemson. Support for the exhibit is provided by the Ford Family Foundation of the Oregon Community Foundation, Arlene Schnitzer, the Coeta and Donald Barker Changing Exhibitions Endowment, the Harold and Arlene Schnitzer CARE Foundation, a grant from the Oregon Arts Commission, and the National Endowment for the Arts (a federal agency), the Ballinger Endowment, Philip and Sandra Piele, and JSMA members.

Open now–March 19, 2017

Sandra Day O’Connor Gallery. Once visitors explore and learn about the Native people in the Southwest in the HOME exhibit, they can expand on their learning with several fun, hands-on activities based on diverse tribal cultures and designed to help deepen understanding of what was seen in HOME. Visitors are encouraged to return to the HOME exhibit after completing their activities in It’s Your Turn, so they can see which parts of the exhibit inspired their creativity.

April 9, 2017–August 20, 2017