5 minute read

BREAKING NEW GROUND KATHLEEN WALL’S ARTISTIC EXPLORATIONS

BY AMERICA MEREDITH (CHEROKEE NATION)

ATHLEEN WALL’S CERAMIC AND BRONZE SCULPTURES have garnered her a loyal following, as has her warm, outgoing personality. She has met with immense success in the Native art market circuit. For instance, she recently won Best of Show at the last Eiteljorg Indian Market and Festival. But there is so much more to her artistic practice than can fit into a ten-by-ten-foot booth.

“Many people” in her pueblo, Wall says “know how to make pots, but not everyone loves it” or has the passion for wholeheartedly pursuing ceramics. Her mother, Fannie Loretto (Jemez), gave her some basic lessons, but mainly she learned through observation. She still digs and prepares her own clay and earth pigments, demonstrating how significant materials and processes are in Native art.

“The materials I use in the body of work are extremely important to me. I have been working in traditional clay from my reservation for the past 24 years,” Wall says. “I dig my clay in a clay pit that was shown to me as a young girl by my mother. I also dig volcanic ash in the same spot that I have been collecting ash my entire career.” She’s proud to continue the sustainable artistic processes that her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother performed while she developes her own conceptual and aesthetic visions.

When she wanted to branch out and have a solo exhibit, Wall organized and underwrote it herself. She approached the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center about hosting Celebrating Native Legacies: Works in Clay by Kathleen Wall, which showed in 2009 and 2010. The premise of the show was to explore the tribal cultures of Wall’s family and friends.

“When I say family, I’m not just talking about my children and husband,” she says. “I have a very large extended family that spreads out to more than eight different Pueblo tribes, five different tribes across the United States, and other nationalities, and with this diverse crowd come many different cultures and traditions that I find intriguing.”

The artist lives in and is enrolled at Jemez Pueblo, but her heritage and those of her three children are much more complex. Her father, the lawyer, judge, and professor Stephen Wall is Seneca and White Earth Ojibwe. Her husband Michael Chinana is Jemez and Cherokee Nation (from the Wildcat family), as are the couple’s children. Wall created more than a hundred artworks exploring these cultures and made the leap from potter to multimedia installation artist. She made figurative sculptures but also ceramic versions of black ash bark baskets and stickball sticks—pushing the medium in counterintuitive directions a la Jeff Koons (a major distinction being that she both conceptualizes and builds the work).

Wall incorporated video and sound into her pieces: a Pueblo adobe building containing video of her relatives in discussion or a hogan with a video of Navajo weaver Pearl Sunrise. She often collaborates with Laguna-Zuni videographer Dale Waseta and traveled to Gila River and recorded an Akimel O’odham troupe dancing. Interviewing tribal members has become integral to Wall’s process.

While the Albuquerque Journal named Celebrating Native Legacies as one of the top five exhibits in Albuquerque in 2009, museum curators were not as quick to take notice. Undaunted, Wall forged her own path. She wanted to add painting to her installations, so she enrolled at the Institute of American Indian Arts

(IAIA), where she had earlier earned her two-year associate’s degree in fine arts but now wanted to complete her bachelor’s degree.

Wall’s first attempt at painting was Core Values, a mural with three ceramic figures, a Pueblo grandfather and his two urban grandchildren, examining and discussing the work. The mural, now in the collection of the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, depicts “100 years of Pueblo policy and how it affected Pueblo people,” as well as yearly events—cleaning irrigation ditches, planting, collecting pollen, harvesting, dances—the cycle of seasons that underpin Jemez cosmology. The grandfather explains to his grandchildren the core Pueblo values: “Love, language, culture, and service, and those give us strength in our every day,” as Wall says.

While at IAIA, Wall developed her first series of installations combining the two-dimensional realm of painting with the three-dimensional ceramic sculpture, Harvesting Tradition. The series explores Indigenous food sovereignty, a subject close to Wall’s heart as a mother concerned about the health of her family. Idea for the series developed over years.

“When imagery or ideas came to mind relating to Harvesting Tradition, I put it in a mental notebook inside my head,” Wall says. She not only celebrates Indigenous food crops, such as saguaro cacti, maize, and wild onions, but also Native hunting practices. One installation, Rabbit Hunter, features a Pueblo man hunting desert cottontails with a throwing stick.

Even though she paints with premade acrylics, Wall adds sand, clay, and powdered mica to alter their texture and finish. She finds painting challenging but keeps pushing herself with large scale, representational landscapes.

To bring this series to the public Wall curated another major solo exhibit, this time at the now-defunct Pablita Velarde Museum of Indian Women in the Arts in Santa Fe in 2014. She gathered a team of friends to install and promote the show, leaving no detail overlooked for Kathleen Wall: Harvesting

Tradition

A major break for Wall happened last year with the award of a prestigious Eric and Barbara Dobkin Native Artist Fellowship for Women at the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe. SAR provided housing, large enough for Wall, Michael, and their children for three months; studio space; and access to SAR’s extensive collections for research. The fellowship also provided networking opportunities, with other researchers and artists, scholars, and collectors—so the experience was a mix of frenetic studio work and meeting like-minded scholars, collectors, and art professionals.

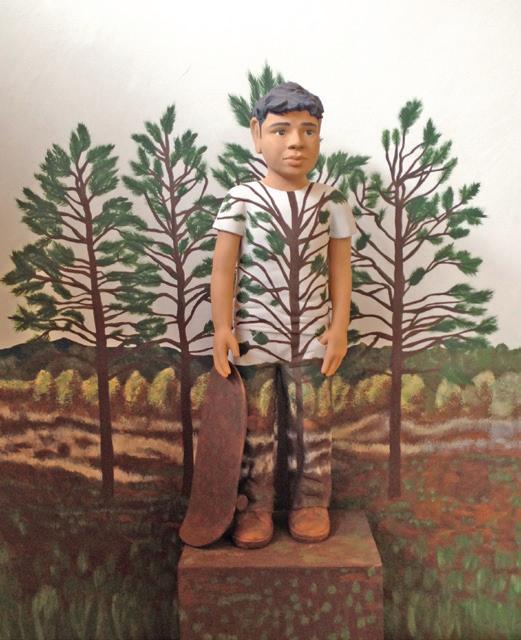

At SAR, Wall launched Place, a series of figurative sculptures and landscape paintings about a heretofore-unexplored topic: how Indian names anchor an individual to a specific landmark. Her maternal grandfather inspired this series. His Indian name references a sacred site that is now part of a ranch to which Jemez people no longer have free access. Wall was finally able to identity the mountainous area for which her grandfather was named. She sculpted her grandfather in clay—including his sunglasses (he was blind toward the end of his life)—and painted the mountains on a canvas behind him but also in his clothing, which created a Rene Magritte-esque optical illusion. This play between two and three dimensions united the pieces and visually emphasizes the relationship Native people have to their homelands or other significant, sacred sites.

The very notion of being Indigenous comes from one’s relationship to the land. Merriam-Webster defines it as “produced, growing, living, or occurring naturally in a particular region or environment.”

“I want to explain to outsiders and different people how important place is to Indigenous people,” says Wall. “They don’t understand the connection that a lot of Native people have to land—to an actual place. We don’t have to make a monument on something. We don’t have to make a sculpture on something for it to have significant importance. It just is.”

When SWAIA presented Native artists with the opportunity to show larger works at their Indian Market: Edge exhibit, Wall seized it. Since then, she has been eager to find more venues that will allow her to show her developing series.

“I think almost all booth-art artists have something more in them, but it’s a matter of the opportunity given. We just don’t get the space. We don’t get the opportunity,” says Wall. So, she continues to find her own spaces and create her own opportunities.

“I haven’t fulfilled everything I need to do,” Wall continues. “I want to study other people’s ideas of place and where they connect. It’d be ideal to go global and work with Indigenous people who are having issues with the land that they live on—either fighting for it or just trying to protect it—and exploring those connections.”

Thoughtfully, she says, “I enjoy making things bigger than me.” ?

KATHLEEN-WALL.COM

America Meredith (Cherokee Nation) is the publishing editor of First American Art Magazine and an independent curator, and printmaker living in Norman, Oklahoma.