About Film Club 3000

Letter From the Editor

Kemari Bryant

Sci-Fi Sippers Cameron Linly Robinson

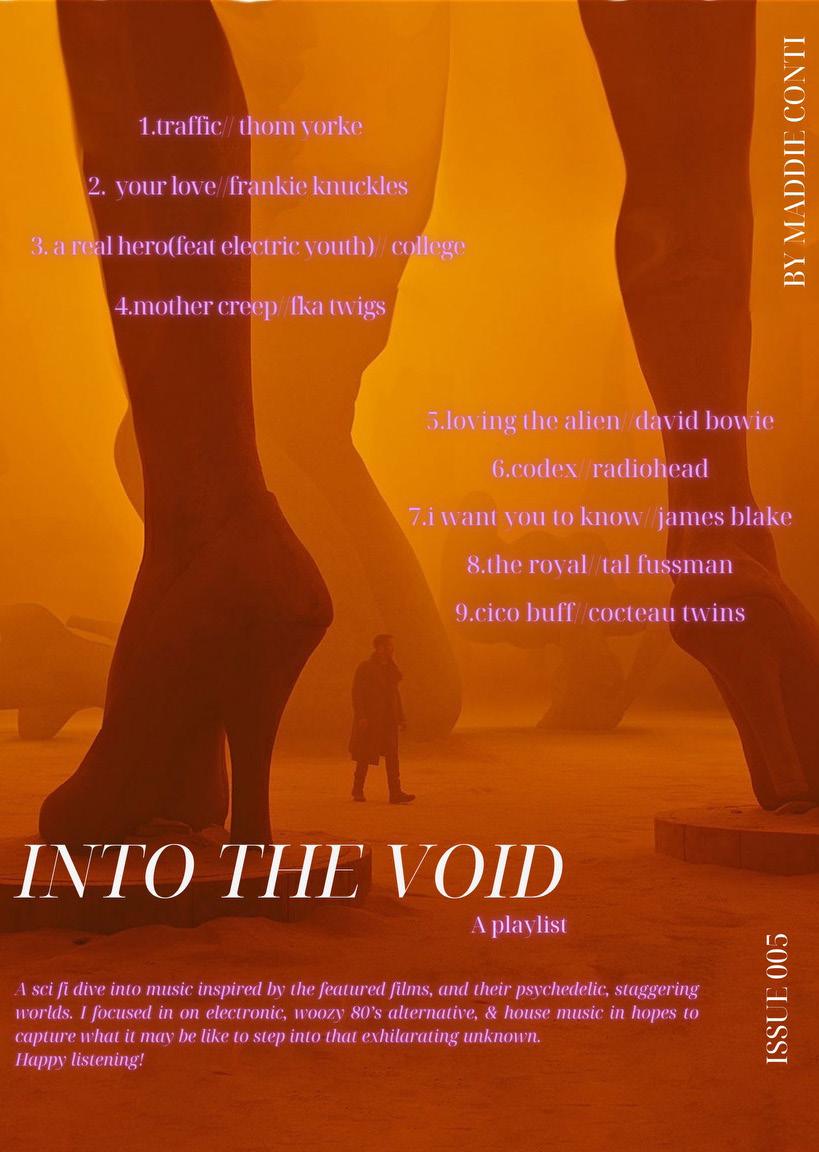

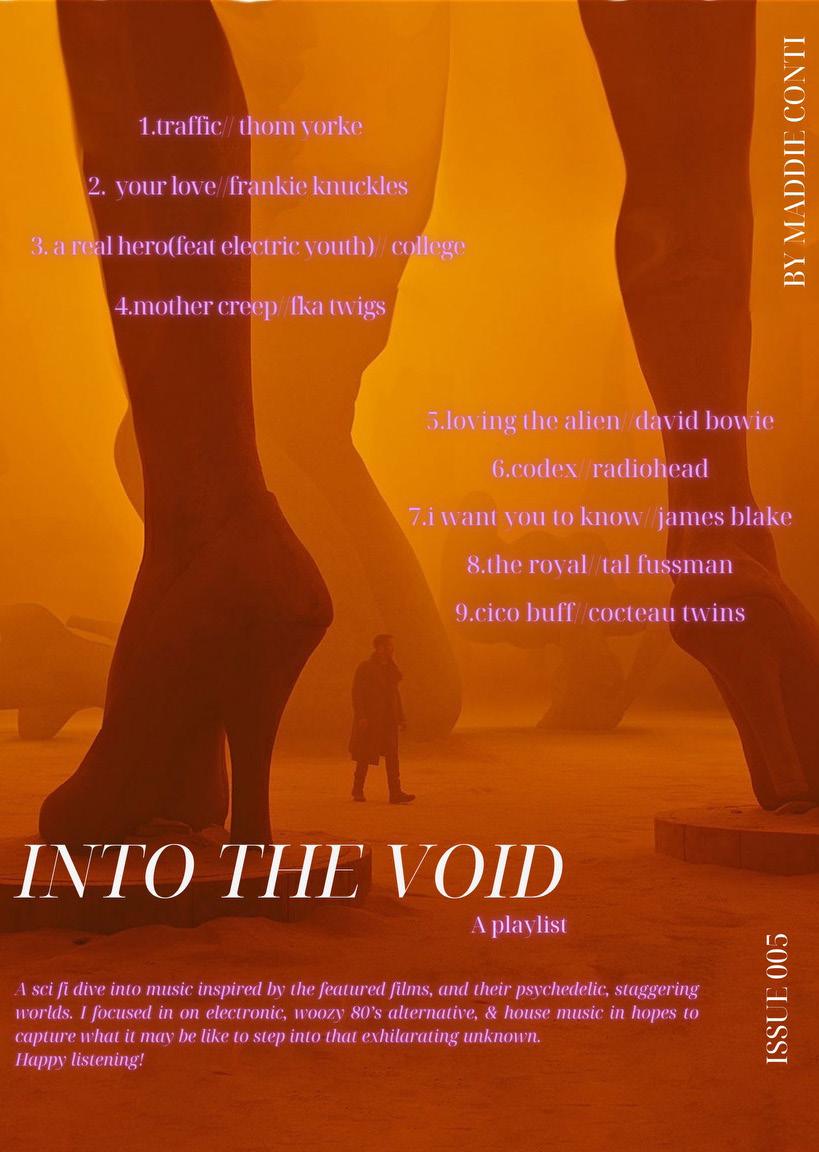

Into the Void A Playlist Maddie Conti

ESSAYS

Looking forward to reflect: Tarkovsky’s interpretation of Solaris Jude Michalik

Civil War, ‘What If?’, and Warning C.C. Lilford

Do Soldiers Cry Over Mechanical Bodies: Antiwar Ethos and Robotic Allegory in The Creator Robert Karmi

Denis Villeneuve: A New Sun Garrett Bradshaw

Post-Nuclear Ecologies and Zoologies: Them and Gojira as Eco-Horror Reactions to the Bomb Robert Karmi

CONTENTS

Issue 005 | May/June 2024

01

3000

ii. iii. OVERVIEW A STILL FROM ANDREI TARKOVSKY’S STALKER (1979)

20 22

04 07 10

16

ABOUT FILM CLUB 3000

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF KEMARI BRYANT

MANAGING EDITOR

CAMERON LINLY ROBINSON

CONTRIBUTORS

ROBERT KARMI

C.C. LILFORD

JUDE MICHALIK

GARRETT BRADSHAW

COVER ART

VICO SANTOS

ALL VIEWS AND OPINIONS ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHORS AND DO NOT NECCESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS HELD BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF.

WEBSITE FILMCLUB3000.COM

INSTAGRAM @FILMCLUB3000

CONTACT FILMCLUB3000@GMAIL.COM

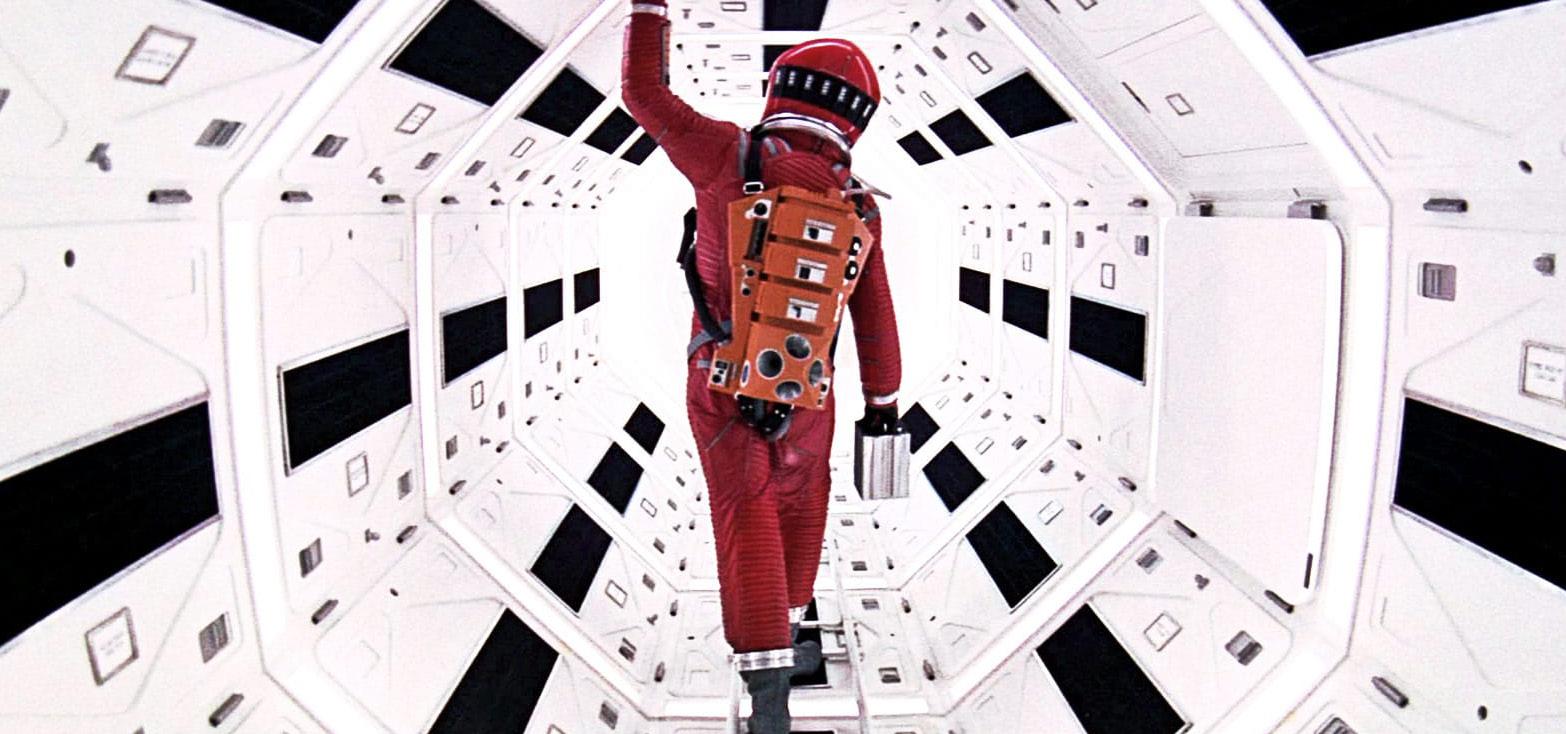

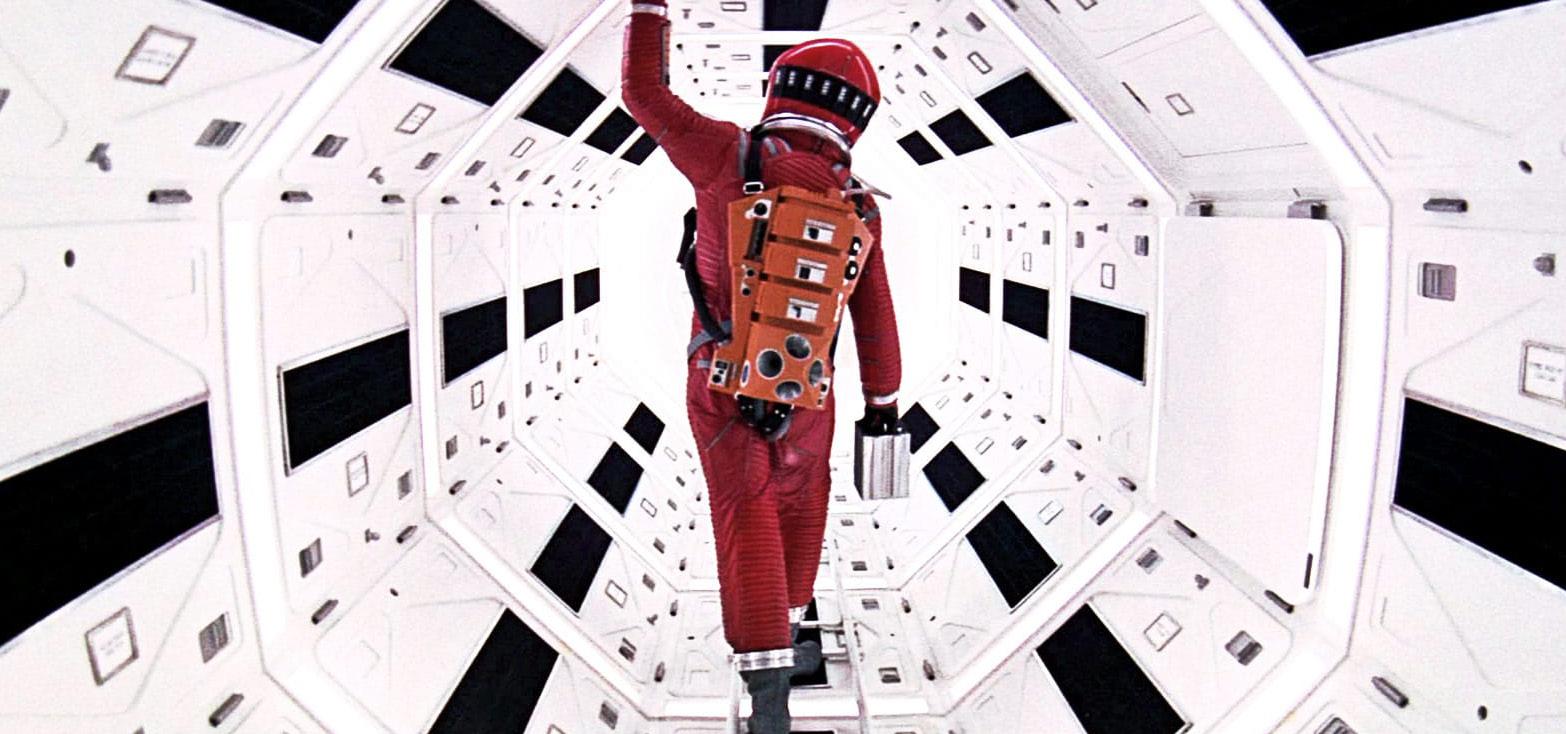

A STILL FROM 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968)

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Readers,

2024 is the future.

At least in the minds of auteurs from several decades ago. In Katsuhiro Otomo’s seminal anime film Akira we are dropped in the middle of Neo-Yokio in 2019, a cyberpunk wonderland full of motorcycle battles and government-controlled mutants. In The Matrix, times have been so hard that the assumed year in the real world is 2199. In 2006’s A Scanner Darkly, the opening leaves us with the information that the film is set “seven years from now”— allowing the audience’s imagination to run wild with the possibility that such techonological development could be just around the corner at any given time.

That’s what I find so fascinating about science-fiction film —this obsession with the possibilities of the future. In going back in time to watch these films we are able to see each possibility that a filmmaker posits: the hopes, the fears, the dangers. Through the most fantastical settings, characters, and situations we are able to break into the core of humanity and ask the essential questions.

As we forge our way into the future maybe we can allow ourselves to dream beyond the dire realities we live in, and these movies can perhaps aid those dreams.

Enjoy, to 3000 and beyond,

Kemari Bryant | Editor-in-Chief

iii | FC3K

THE “AKIRA SLIDE” FROM AKIRA (1988)

Looking Forward to Reflect: Tarkovsky’s interpretation of Solaris

BY JUDE MICHALIK

ESSAY

ANDREI TARKOVSKY’S SOLARIS (1972)

ALTERNATE POSTER FOR SOLARIS (1972) 01 | FC3K

Earthly sway of lake-side meadows lulls our gaze, marking the introduction to Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film adaptation of “Solaris,” a celebrated science fiction novel by the Polish author Stanisław Lem.

The alluring whisper of green and blue hues, bending to the flow of water and gentle breeze, envelops the protagonist – Kris (Donatas Banionis). His figure stands swallowed by the grassy landscape bearing delicate mist, his jacket blends into the colours, itself being a vibrant tone of blue. Our eyes are left to linger, pondering the scenery as Kris makes his way through the field, heavy-footed. Tall, ancient trees hover over him walking, and the gravitas of all this imposing nature stirs something at once familiar and disquieting in our minds.

This entirely rural atmosphere foreshadows the film’s melancholy; through the lens of distant future as well as a distant planet, we look at a man devoured by his earthly past. The muddy roots keep crawling to his neck, and glancing forward he catches a reflection of all that’s behind him in a cruel game of mirrors.

Solaris, the film, stands as unconventional in its genre. No attention is given to the meticulously crafted by Lem technology, nor the science of the planet, and this choice on Tarkovsky’s part forever soured the relations between him and the Polish writer. Thanks to the unfaithful in spirit adaptation, however, we can experience the tidal forces of memory and conscience brought forth through the fog of distant times.

“We don’t know what to do with other worlds, we don’t want other worlds. Only a mirror,” says one of the astronauts orbiting the planet Solaris, dr. Snaut (played by Jüri Järvet). The unfortunate men stranded orbiting Solaris arguably experienced both; while soaring other-worldly in their hollow spaceship, the mysterious ocean soaked their dreams with shards of glass –shining reflections, tearing through the membranes of their memory.

Estrangement, uncanny laughter, and swift shadow figures dashing through the corridors haunt Kris’s first steps into the chambers of the station. We are soon made to understand the guilt and melancholy permeating the walls of his new home; gone are the sun-soaked rooms of grounded familiarity. Instead, the grey, metallic corridors are filled by a swirl of ocean-in-

duced reminiscence leaking from dreams onto Kris’s pillow.

Stranded far from family on his secluded mission, not only do the superficial surfaces glare at Kris with his own reflection, forcing him to confront what he thought left behind –his deceased wife, Hari (Natalia Bondarchuk) is brought back to life, embodying this need for resolution.

We cannot leave unnoticed how strong the Earth’s grasp is on the protagonist, ironically when he is the furthest away from his home planet. He will always be forced to face the reaching hands of weeds, lakes, youth’s love, or loss, for he carries these sentiments within himself, and when one stands confronted by a mirror, one’s only confrontation is with what the self contains, muddled by intertwining recollections and dreams. Such a state of flooding selves seems perfectly encapsulated by Tarkovsky’s use of colour, certainly possible to interpret in various ways. Through the darkblue sequences one can understand the land of Kris’s dreams or memories, most possibly both. As he passes more time on the station the colours begin to seep into his conscious states in an ambiguous manner, further tying him to the past and to the unresolved threads of his life.

The film might take on, in such a way, the same role for the viewer as the Solaris ocean does for Kris and the rest of the crew. Having thrust ourselves into the world of distant-future fiction, we watch as a man tries to cast away a ghost of his own thoughts, slowly growing attached to the illusory comfort of wallowing in recollections. We might uncomfortably shift in our seats, feeling the parallels crawl up our backs.

In Solaris, man thinks he will lead a conversation with progress and discovery, instead finding himself in conversation with himself, losing. Hari’s duplicate rekindles Kris’s feelings, though one must ask: what comfort does a man seek, burning anew a fire that has long been dead, stirring the ashes not seeking resolution, but denial? I argue they could never be out of love, Kris’s attempts at stopping the new Hari from obliterating herself. The resolution, just like the sunlight seeping in through the windows of his spaceship, seems poisonous to the viewer. Unlike the raw power of nature hovering over the characters at the beginning of the

film, the ocean’s illusions, through their indulgent manner, seem to shelter something sinister.

Following Kris back home, the freezing landscape accompanies our breath, half-way in our lungs, frozen in time just as the lake. The silver-laced trees look paling like the protagonist’s greying hair, a gentle reminder of the passage of time and memories buried in the crevices of his life on Earth. The lonely house stands out as the only object in a warm palette, even though dim, and seemingly covered by frost.

Kris looks in through the window, noticing his father, lost in thought. Before we realise that something is terribly wrong, we sense it. Domesticity seems to be within reach, and yet, within the sheltering walls of home a stream of pouring rain cascades onto Kris’s father’s clothes. Seeing the calm figure of the father go around unaffected by the rain, while his shirt is getting soaked and the music assaults our senses, is ridden with a sense of the uncanny. It is then that an attentive viewer might recollect a similar scene at the beginning of the film:

While still at home with his family, Kris is showered generously by a wave of pouring rain. He sits down as the raging water fills up tea cups and bowls set out on the balcony, calm, perhaps enjoying his last rainy day on Earth. His father hides in the solid house, in which, Kris knows, he can always turn to for shelter against the violence of water.

When put together in such a way, the scenes carry a deep symmetry. We watch, as the domestic shelter promising solace births rain. Mirrors tend to reflect a truth only slightly twisted, yet significantly enough to hear Kris’s heart shatter quietly as he watches the imperfect copy of his father shower in the artificial rain of the ocean. In spite of this, Tarkovsky’s Kris chooses to drop to his knees and embrace this father nonetheless, leaving the audience pondering the ultimate meaning of his gesture.

What was Kris seeking, choosing to give in to the ocean’s fumes?

Through the journey of confronting his worst memories and heaviest guilt, perhaps he chose to seek peace with the only version of his father he could reach. To seek forgiveness is often a selfish act, meant only to quiet the wolves of our own conscience. For Kris, the separation with his father and the suicide of his wife, Hari, meant howling for as long as he’s still alive. Perhaps in seeking

We should not plunge through the mirror towards a past less welcoming than our future!

out a symbol to express his feelings towards his father, Kris finally found peace within himself, and in such a way, defeated the treacherous traps of drowning in his mirrored past for eternity, providing us with a bitter-sweet ending.

To look away from the ocean’s mirror-like surface one must either plunge into it, or look above the horizon, hoping to escape the constant glare of the past, lurking from above our shoulders. Perhaps one of the take-aways from this masterpiece of a film could be: we should not plunge through the mirror towards a past less welcoming than our future!

in absolute terms, instead submerging in the ambiguity it asks of us as viewers, and it is the better film for doing so. •

03 | FC3K

DONATAS BANIONIS IN SOLARIS

Civil War, ‘What If?’, and Warning

BY C.C. LILFORD

To describe Alex Garland’s directorial swan song as ‘divisive’ would be an understatement. Weeks before Civil War even had advanced screenings, editorials and think pieces about the ethics and merits of the film’s existence were flooding in from every self respecting entertainment outlet, to say nothing of the hot take fervor that concurrently gripped social media. Curiously, lost in the arms race of opinions is any sort of discussion of Civil War as a work of science fiction. This is a necessary context which helps to better understand what Garland is doing with the film.

It might seem odd at first to classify Civil War as a science fiction film. After all, it is noticeably lacking in robots, spaceships, aliens, parallel universes, time travel, ray guns, or any of the usual paraphernalia we associate with the genre. But these aspects are merely paraphernalia for the genre rather than essential elements and there are two specific traditions of science fiction to which Civil War belongs, science fiction as explorations of ‘what if?’ scenarios and science fiction as warnings for the future.

Ever since Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1818 science fiction has been founded on and driven by the question of ‘what if?’. As Ursula K. Le Guin rather succinctly said:

“The science fiction writer is supposed to take a trend or phenomenon of the hereand-now, purify and intensify it for dramatic effect, and extend it into the future.”

Going back to Frankenstein for example, the novel is based around the question of ‘what if man could create life?’. The exploration of this idea and all of the ways the resulting scenario would play out are what the entire novel is built out from. This is not to say that all science fiction is grounded in ‘what if?’ scenarios (it would be hard to pinpoint the ‘what if?’ in Star Wars or Flash Gordon for example) but it’s a significant driving ethos of the genre nonetheless. It’s easier to recog-

nize science fiction as such when the ‘what if?’ is a question like ‘what if we invented machines that could think?’ or ‘what if the ancient pagan gods were really aliens?’ but it becomes trickier when the question is seemingly less fantastic. Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men is recognized as science fiction even though there is nothing overtly other-worldly about the premise. Like Frankenstein, it starts with a ‘what if?’ (in this case, ‘what if mankind was affected by a pandemic of infertility?’) and builds out the world, themes, and narratives from there as it explores that central question. Even more nebulous is Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion, a film that examines the hypothetical outbreak of a deadly virus (a film that consequently became incredibly popular on streaming during the Covid-19 pandemic) or Deep Impact which looks at the hypothetical response to an asteroid discovered bearing down on the earth. Civil War is preoccupied with one deceptively simple ‘what if?’, ‘what if the United States faced a second civil war?’. To answer this question Garland builds out from it, pulling from historical examples of other fractured nations (the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the Sudanese civil war, the Partition of India, the current crisis in Somalia) and transplanting the dynamics and imagery of those conflicts into a setting that is recognizably American but in a not-too-distant future. Thus Garland builds out the original ‘what if?’ into a possible scenario for the future.

Or rather, a warning of the future. The ‘science fiction as warning of the future’ is another tradition that goes back to the genre’s inception. In an interview with Joe Higgs, Alan Moore points out that this goes back to H.G. Welles and even Jules Verne. Welles was more explicit, a great deal of his novels deal with some fu-

ESSAY

turistic technology (invisibility, time travel) and the often terrifying implications of that technology on the human race. Verne (often considered a more pulpy adventure science fiction writer) often wrote about fabulous technology falling into the hands of eccentric men or tyrants who used it for their own ends or agendas. Into the 20th century this grim tradition led to science fiction splitting off the dystopian sub-genre. A genre that, before it was overrun with teenage heroes, was defined by books like 1984, or Brave New World that created dark portraits of possible futures for nations, the earth, or the human race. These portraits were crafted deliberately without hope, or without a hero who bravely saves the day at the end because the goal of these works was not to leave the reader with hope, the goal was to show a vision of the future that the reader would want to avoid. Dystopian fiction is a call to action, a vision of the future told with an understanding that if we collectively reach a world that looks like this it is already too late, and we have to avoid this future.

It is into this tradition, of science fiction as a warning of a possible grim future, that Civil War neatly slots into.

The prospect of a splintered union is one that continuously lurks beneath the collective American psyche but it came up for air around February of 2023. At that time congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Green tweeted that it was time for America to have a national divorce between the red and blue states and the dissolution of the federal government. In the fallout from this (and with the concurrent rise of different separatist movements like ‘TEXIT’) there was a wave of think pieces and editorials discussing a national divorce and whether or not it would lead to a civil war. The issue being that in the event of a ‘national divorce’ there is no scenario where it wouldn’t lead to a second American civil war. Brynn Tannehill, writing for The New Republic, explained that if certain states wanted to leave the union there were, based on historical precedent, two scenarios: one where the union let them go and one where the union fought back. In the first scenario, the rebelling state would be allowed to leave but this would have a

cascade effect causing other states to leave the union, breaking America into several smaller nations which would find themselves in competition for resources thus leading to border disputes and conflicts. In the second scenario the events of the first civil war would play out again, the rebelling states would try to leave, the government would try and stop them, war would break out. In short, if the union is compromised there is no scenario where war on some scale does not result. It is therefore impossible to toy with the idea of a division of the union without additionally toying with the idea of a contemporary American civil war.

This is where Alex Garland and Civil War re-enter the discussion. Garland is one of the few people looking on at all of this discussion who truly seems to understand that a second American civil war would be apocalyptic. More Americans died in the American Civil War than in both World Wars put together and that was with 19th century weapons technology. Garland assumes that the only reason Americans would flippantly discuss the dissolution of the union would be that the average American has become disconnected from the true implications of a war on American soil. It has been well over a hundred years since a war was fought on American soil, with the American Civil War ending in 1865 and the Battle of Wounded Knee taking place in 1890. With Civil War

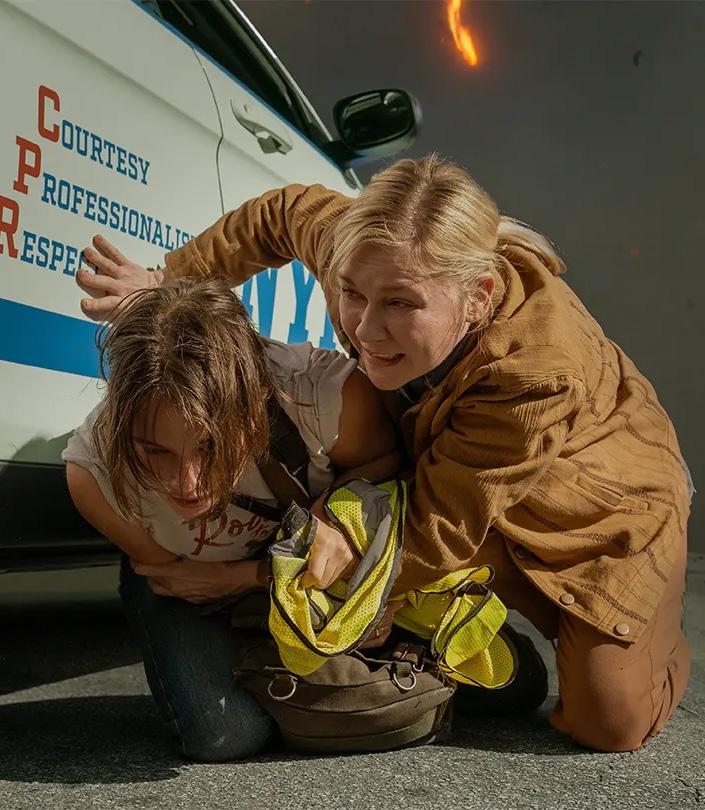

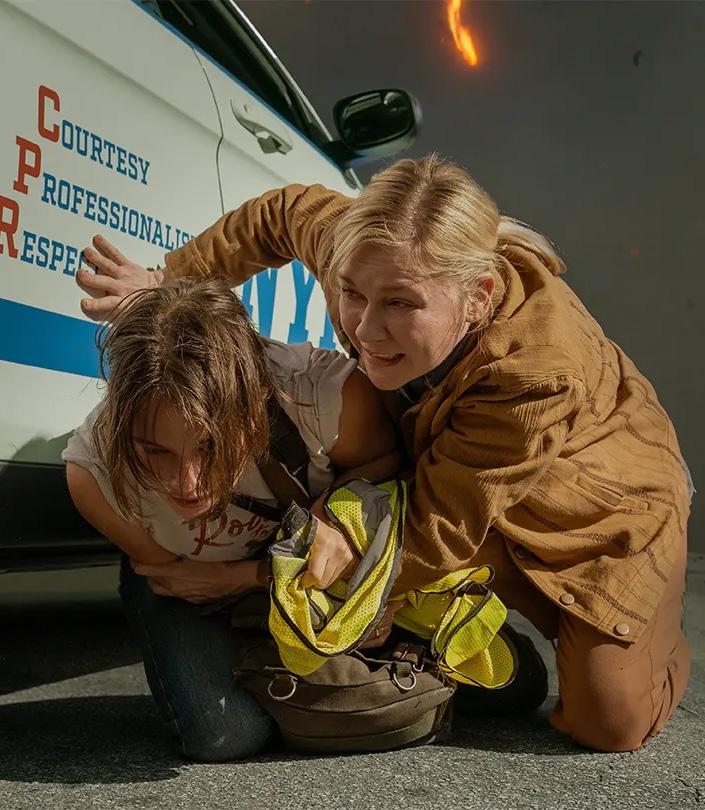

STILL FROM CIVIL WAR (2024) 05 | FC3K

then Garland sets out to reacquaint viewers with what it would look like, taking all of the violence that Americans are used to exporting, all the imagery of American war that Americans are used to seeing play out in foreign countries and bringing it back to America. Soldiers in the streets of Washington DC or New York rather than Kabul or Baghdad. Garland understands that America is one of the most formidable militaries on the planet and turning all that violence inward would wreak devastation on an unimaginable scale. Furthermore, Garland strategically withholds certain pieces of information about the war so as not to make the factions and the motivations apparent to the viewer. If the viewer knew what the sides were fighting for they would be tempted to pick a side, denied this information a viewer has no choice but to watch the horror unfold without having anyone they can root for. This is further emphasized by Garland having the film’s principal characters not be soldiers or civilians but war journalists, who’s job is to watch and document the horror while keeping their own beliefs at a distance.

The film’s finale, in which the western coalition forces push into Washington D.C. to storm the white house and kill the president, fully brings the horror of the situation to bear. We are forced to watch an American army roll into America’s own capital, we see landmarks in flames, war planes and helicopters flying overhead, gunmen fighting street to street, the rattling of gunfire, and through all this we aren’t allowed to know who to root for. We are denied having a group to ideologically agree with and so we have to take the carnage at face value. Garland doesn’t care about sides, what he wants us to take away from this is that a second American civil war is not something to be treated flippantly. He posits the question ‘what if America did have a second civil war?’ and the answer he comes to is a bleak vision of what a second American Civil War would look like and why it must be avoided. •

taking all of the violence that Americans are used to exporting... and bringing it back to America

Do Soldiers Cry Over Mechanical Bodies: Antiwar Ethos and Robotic Allegory

in The Creator

WBY ROBERT KARMI

ithin sci-fi cinema, depictions of sympathetic robots remain a relatively recent phenomenon. Such a pivot from robots being cannon fodder by mad scientists felt inevitable, as our understanding of the consequences of creating new intelligence wore heavy upon us. There have been several attempts to create diverse ways in which the metaphor can work, most notably with robots seen as a proletariat-like underclass struggling to perform forced labor (appropriate considering the Czech origins of the word robot). Perhaps the most well-realized variation of that theme remains Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, which remains a high-water mark for cyberpunk science fiction. From there we can trace a direct line to later work, from Mahiro Maeda’s The Second Renaissance duology in The Animatrix, Alex Proyas’ adaptation of I, Robot, and Alex Garland’s psycho-erotic cyberpunk thriller Ex Machina.

Ex Machina is of special note here, as it helps bring in another facet of systematic oppression to the central metaphor of robots as an oppressed underclass, namely, gendered oppression. It complicates the metaphor by

adding other intersecting identities onto the foundational identity of the working class two robots, which in and of itself feels like a necessary step into the next phase of the evolution of that metaphor. Yet, one must also make it careful, as failing to fully understand the nuances of said allegory may come across as further othering the marginalized groups that the filmmakers seek to represent empathetically. It is along these lines that Gareth Edwards’s most recent movie, The Creator, becomes a novel film in the discourse, not only explicitly wanting to tether racial identity to the robots, but also placing a sympathetic robot story within the context of a war film.

In an alternative timeline, robots relocate to Southeast Asia after a nuclear disaster to avoid ostracization, which results in a war between the USA and Asia. Specifically, the film follows an ex-special forces agent (John David Washington), traumatized from his last undercover mission, recruited to seek out the titular Creator of robots and their weapons. Apathetic beyond finding the woman he loved during his prior mission

ESSAY

07 | FC3K

(Gemma Chan), he helps American forces search for a super weapon that could end the war in Asia’s favor. What he discovers in a lab raid is a small robotic child (Madeleine Yuna Voyles) whom he hopes can help him find his old love, and as the narrative progresses becomes increasingly apparent as the most sophisticated robot to date. What follows is a journey across Asia that lays forth a series of orientalist-flavored cyberpunk vignettes further exploring the themes of neo-colonialism, transhumanism, and most importantly, robots as autonomous, sentient beings.

When stripped of its more fantastical narrative elements as the film progresses, The Creator can be best described as a war film with a cyberpunk/ techno-orientalist aesthetic. While in line with how advanced technological aesthetics are frequently constructed atop other genres to create sci-fi, very rarely is that foundational genre the war film. Generally, sci-fi war films exist within escapist fiction rather than in more speculative ones, wherein the point of the film is less about exploring the ramifications of the technologies and intergalactic fauna or flora upon humanity, but as vehicles for more traditional, adventurous stories newly contextualized with advanced technologies and otherworldly lifeforms. Such a trend reminds one of Arthur C. Clarke’s attitudes, paraphrased, that such fantastical technology becomes so advanced that it becomes imperceptible from magic to its characters and audience, and thus not sci-fi.

That trend arguably finds its origins within the release of George Lucas’ Star Wars, itself more a fantasy film fused with a golden age WWII film than straight sci-fi. It found remarkable success in that combination, thanks in part to the undeniably artful way its effects and craft helped convey those narrative elements, but also as an alternative to what else was going on in American cinema. Concurrent with the release of Star Wars was an ongoing movement where antiwar films that questioned the ethics and attitudes of warfare became more mainstream. These antiwar films, largely centered on the Vietnam War, confronted audiences with difficult questions about the efficacy of war, the righteousness of war-making, and if it were at all justified, attitudes never entertained within the contemporary war cinema of WWII. By returning to the comforting nostalgia of that era, Lucas’s Star Wars made the war film fun again, with no ambiguity between hero and villain or right and wrong.

As it remains one of the most influential films within the blockbuster sphere, many subsequent films take that same ideological cue from it, wherein they are more interested in reappraising classic stories within sci-fi contexts than in challenging contemporary attitudes and presumptions. Yet by necessity, the genre must evolve to remain novel and engaging. Even the post-prequel, post-Lucas Star Wars films have attempted to find ways to investigate such attitudes within their framework, even if fleetingly. Here is where Gareth Edwards first appears with his immediate predecessor to The Creator, Rogue One, the most overt example of the described phenomenon at that point. That film is much more interested in the minutia and mechanics of which warfare and terrorism than in the broader mythology of the franchise. It goes as far as to suggest that there is ambiguity at work within individual combatants and that morality is relative, which might as well be antithetical to the series.

That ideological line of thinking continues within The Creator which makes it much more explicitly about Vietnam, going as far as to have the robotic combatants staged in East Asia, both in villages and in cityscapes meant to evoke the collective iconography of both the war and cyberpunk. Through that, Edwards is doing something more daring than even Rogue One, which remains tethered to the more conventional sense of pleasure that follows the post prequel sensibilities of the franchise. The Creator on the other hand does its best to try and remove enjoyment from the specific set pieces to reemphasize the antiwar sentiment at the base of the project. One of the ways that is apparent is the way that shots linger on the bodies of the mechanical combatants as they are torn apart by gunfire, the light slowly or suddenly fading out as they lose their lives, reinforcing the tragedy of their loss.

When contrasted with the American military presence in the film that treats the deaths as nothing, the loss of enemy combatants the entire point, and one officer (Allison Janney) even going on a racist tirade explaining she kills robots as revenge for her fallen son, the point becomes clear. It makes the loss of enemy life sympathetic and tragic; it portrays the American forces as petty and jingoistic, willing to take civilian life incidentally alongside military

forces, and establishes throughout the runtime that the war could end if the American side simply stopped. As the narrative progresses, we see the main character, in part due to the exposure to the culture of his enemy combatants and his budding relationship with his young charge, begin to reconsider and abandon his previously conceived patriotism in favor of a more empathetic allyship with the marginalized. In effect, the film is a portrait of a soldier priorly considering themselves apathetic to the plight of the perceived other becoming radicalized and forsaking the imperial core for the resistance.

The film is not entirely successful and can easily be read more critically, however. The aforementioned empathy created for the robotic characters through the lingering portrait of their bodies becomes problematic when considering the racial allegory, especially when it is further honed in on via the way the film depicts human bodies; throughout the film, we see much more graphic depictions of violence against bodies of people of color than we do of white bodies. Such readings are in part by design, since the enemy combatants are exclusively East-Asian beyond the robots whereas the American forces are almost unilaterally white, which again reinforces the Vietnam allegory. However, that element does lamentably reinforce the idea that the bodies of people of color, here most represented by robotic bodies, are recipients of greater violence than white bodies which is further made into a spectacle. The intended reading might become lost, from such portraits of violence going from upsetting and repulsive to attractive and engaging.

Such a worrisome trend persists within contemporary genre fiction, however well-intentioned, that sets itself up for discourse about how certain bodies are more readily made the sights of spectacular violence than others. Alex Garland’s most recent film, Civil War, likewise deliberate in its utilization of that sentiment, also falls into the same problem, especially when you consider not only what kind of violence comes upon these bodies, but in what ways. To be fair, both works are about confronting on some level white supremacist attitudes within American culture, so it makes sense that both would emphasize the racial violence that would befall those who encounter them. Yet that implies these projects from the offset are presuming a white gaze upon themselves, wherein the perspectives that they adhere to are for the intent

of converting white audiences to their cause. Those aspirations are fine enough ambitions to have, yet also cannot help but alienate audiences of color or those who need far less convincing of the horrors they are witnessing.

Beyond the conventions of these genres lies an even greater failing of the work, and one that cannot help but be emblematic of war films made within imperial cores. The term “shooting and crying,” initially coined specifically in studies of Israeli war narratives, creates experiences in which soldiers portray themselves as remorseful for their prior actions and seek to articulate that sorrow through art articulating their wartime experiences, often to the detriment of the perspectives of those they were fighting against. Such examples of these stories usually depict soldiers as merely following orders and often are less engaged with the culture of the enemy as much as using their bodies as extensions of their military service. Considering how frequently those sites of interest are usually Palestinian bodies, it is easy to graph ethnic and racial things into the genre. As such it is easy to draw a parallel between these Israeli works and American narratives about Vietnam. Since The Creator is a sci-fi reappropriation of those narratives, it carries that similar problematic subtext.

And yet The Creator does not fall neatly within that categorization either, as ultimately its perspective character does challenge the authority of his commanding officers and his nation and leaves his station to help his prior targets. It is a film that is unilaterally attempting to display, through genre fiction, a means by which we can investigate and challenge our perceptions of conflict and warfare with greater empathy towards the perceived other. Peculiarly, The Creator most feels like it continues the spirit of George Lucas’ original Star Wars much more than even Edward’s own Star Wars film, and as much as that it takes disparate ideas of genre fiction and war cinema past and synthesizes them to create a distinct idiosyncratic experience through spectacular sci-fi imagery and set pieces. Even if it is not entirely successful as a cohesive project, it is laudable for its incredible ambition and worthwhile sentiment of anti-imperialism and anti-militarism, especially in times when unjust wars and genocides rage on in our contemporary world. •

09 | FC3K

DENIS VILLENEUVE BY JACK DAVISON

DENIS VILLENEUVE BY JACK DAVISON

Denis Villeneuve: A New Sun

BY GARRETT BRADSHAW

BEGINNINGS ARE SUCH DELICATE TIMES

Mid-1980s. A young boy sits in his kitchen, eating cereal. He gazes out the window at the nuclear power plant on the horizon. These menacing smokestacks stir in him a deep well of imagination of the future, aided by his father’s technology and science magazines and classic films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Blade Runner.

Decades later, this young boy would be responsible for names like Quizat Haderach and Lisan-al Giab being firmly in the public consciousness, which is a feat in and of itself. Not to mention the legendary run of films he’s directed, finally culminating in his opus: Dune Part 1 and 2. It was a long and often difficult road to get here, in the wake of the Sci-Fi film that will likely define the decade, the same as his lofty influences. But each step was taken carefully as he ascended into the ranks of All Time Greats.

This man is, of course, Denis Villeneuve. Five years ago, no one was talking about him, perhaps in part because his name is quite difficult to pronounce (de-knee vil-nuhv, by the way) but mainly because he had spent the first few decades of his film career carefully honing his skills, adding tools to his belt, sharpening them at every opportunity he got. That patience has more than paid off.

He tapped into that reservoir of imagination and talent with each film he directed, taking notes from each as he strove toward his goal of adapting Frank Herbert’s masterpiece, one that he’s held close to his heart for decades. Specifically, his gift of adapting fiction to screen in Arrival and his dedication and deference to source material not affecting his vision with Blade Runner 2049, all culminating in his masterful execution of his childhood dream: Dune.

THE FAMILIAR WAS FAR AWAY

In a stroke of fate, Villeneuve’s first film August 32nd on Earth released the same year as a collection of short stories by author Ted Chiang titled “Stories of Your

Life.” In this book, the titular story dealt with what might happen if Earth was suddenly, and without explanation, visited by an alien race dubbed the Heptapods and how a young linguist goes about translating their language to decipher what their purpose was, discovering her own along the way. Once his film Sicaro had wrapped, Villeneuve was seduced by the screenplay adapted from Chiang’s work, eventually renamed “Arrival” due to the changes made therein. Just before the release, Villeneuve sat with Variety for an interview, in which he was asked about the stark contrast between this upcoming film and the ones preceding, like Prisoners, Enemy, and Polytechnique (all of them fantastic). He mentioned that no script had really grabbed him until “Story of Your Life” came around and, when asked why he was suddenly trying his hand at the harder and more expensive world of Sci-Fi instead of the more grounded dramas, he paused and thought for a moment. He finally responded: “I didn’t turn to science fiction. I went away from it.”

In his first foray into the world of adaptation, specifically that of Sci-Fi, Villeneuve had to carefully walk the tightrope of honoring the source material, but adapting it to the screen with use of film language. He does this in a few ways, most strikingly in his use of scale. For example, in the novella Chiang places the Heptapods in orbit around Earth, with the aliens sending down “looking glasses” to initiate communication. One of the shifts that Villeneuve and screenwriter Eric Heisserer first pitched was bringing the aliens to our front door and one of the choices that made this so successful was the grand scale in which their ships are represented and shot. The audience gets the sense of the impossible size of the vessels and, with the added sleek, stone-like design, an idea of who these otherworldly creatures are and what they will invoke: this unique and haunting beauty that causes a tightness in your chest that never quite leaves until they do.

Another departure from the page is the written language of the Heptapods. In Chi-

ESSAY 11 | FC3K

ang’s book, it’s described as “vaguely cursive,” symbols running together in a constant stream, written using a device in which a Heptapod inserts their tentacle. In the film, Villeneuve decides on a design that, according to the screenplay, “is poetry in motion. A dance of ink.” It also reminds one of an ouroboros, the snake eating its own tail, written in a substance directly from the alien’s themselves. This change seems almost inconsequential, but making the language, and by extension their concept of time due to how they write, a fundamental part of the Heptapods further demonstrates the overall importance of language in the film that the book uses actual words and Louise’s thoughts for.

A final benefit the book utilizes with written word is how it reveals its twist. With tricksy verb tenses, something as simple as a conjunction catches the reader’s eye and raises an eyebrow. The first of these goes like this: “I remember the scenario of your origin you’ll suggest when you’re twelve… That will be in the house on Belmont Street. I’ll live to see strangers occupy both houses: the one you’re conceived in and the one you grow up in.” (Chiang, Ted. “Story of Your Life.” Stories of Your Life and Others.) If read carefully, Louise is describing memories that have yet to happen. “I remember the scenario you will suggest,” grow not grew up in. Later on, a section begins “I remember one day during the summer when you’re sixteen.” Are, not were. It’s infectiously subtle and drove me to pick apart every bit of syntax each time one of these “memories”

came around. Chiang’s showing of his cards doesn’t stop there. Just a few short pages in, Louise’s daughter Hannah’s fate is revealed: killed in a mountain climbing accident.

Villeneuve and Heisserer take the opposite approach. While Chiang shows us the box art of the puzzle we’re building, he only shakes out a few pieces at a time. The director and screenwriter give us every single piece, but we have no idea what this thing is supposed to look like. The film begins with Louise remembering her future with Hannah, showing flashes of her as an infant, scenes from her childhood, and her demise, which the film changes to an rare illness (we’ll get back to that soon), but when it cuts to Louise in the present day, with a much more muted color palette, the audience likely assumes that this has already happened to the Louise that takes center stage in the core narrative. Additionally, when flashes to these moments with her daughter continue and increase as she becomes more integrated with the Heptapod’s “seeing all time as one” thought process, we fit the pieces together that the event of the alien’s visit is causing some traumatic flashbacks rather than showing her what’s to come. Finally, during the film’s climax, it’s revealed that Louise doesn’t know who this child is - that the look she wears when one of these flashes comes about is not pain but bewilderment. We are finally shown the picture on the box and, when we look down at this puzzle, we realize that we’ve put it together complete-

A STILL FROM ARRIVAL (2016)

ly wrong.

Now, I’m not here to tell you which is better. I enjoyed experiencing both tremendously, even knowing the reveal going into the novella. But it’s important to distinguish that these differences are necessary for their respective mediums. One reveal only works with words on a page and the other, done so in the most visually stark scene in the film, needs to happen that way. Another seemingly inconsequential change of Hannah dying from a climbing accident to an incurable disease is one that solidifies Louise’s choice to experience the joy of having her at all, despite the known inevitability of the tragic loss. The novella deals with the concept of knowing the future and resigning not to change it, which is painted as a fairly scientific choice, but film Louise’s decision is purely one of emotion: she knows her daughter will die, that she will be utterly powerless to stop it. She knows her husband, Ian, will leave her because he cannot face the suffering and especially the idea of knowing Hannah will die, but Louise does it anyway. Because she understands that any time she may have with Hannah is worth every moment of grief that may come.

QUEENSBORO

Pretty immediately after Arrival finished production, Villeneuve was approached by Alcon Entertainment, who had produced Prisoners, and asked him to meet in a secluded cafe in New Mexico. Appropriately spycraft in nature, the representative he was meeting slid an envelope across the table. In it, a single piece of paper with one word: “Queensboro.”

This producer, Andrew Kosove, told Villeneuve “Queensboro doesn’t exist. That’s the new Blade Runner project.”

The pressure and excitement must have been equally intense. Here was the opportunity to craft a sequel to one of the fathers of Sci-Fi as we know it and one of huge importance to Villeneuve himself. Interestingly enough, a “failure” at the box office has cast Blade Runner: 2049 into obscurity among modern audiences, similar to that of its predecessor, which eventually found its way to cult status after various re-releases and enough years behind it to bloom into being

recognized as the masterpiece it’s often heralded as. Despite a regret that seemingly haunts him, Villeneuve learned crucial lessons and took care to note anything that might be helpful in realizing his dream of Arrakis.

An immediate juxtaposition between Arrival and Blade Runner: 2049 is the budget and how it’s utilized. Partnering with cinematographer Roger Deakins, Villeneuve was able to build upon some of the most iconic designs and improve upon them to flesh out this dystopian future California, from the Sea Wall to an irradiated Las Vegas. Not to mention the city of LA, neon soaked and dilapidated, every frame is a work of art from the opening eye to the final shot of Deckard with his long lost daughter (whose eye the film opens on, wow I love this movie). I genuinely believe this movie would still be as affecting with just the visuals alone, but the slow burn and affecting screenplay that accompanies it certainly has its own merits, yet another tool honed on Villeneuve’s path to Dune. Another important lesson gained from working on Blade Runner was how reverence and deference are not at all the same, and may even be enemies of one another. It would be dangerously easy, for instance, to just make Blade Runner again, treading the same ground and falling into the trap of legacy sequels with nothing new or interesting to say. Instead, this film focuses on new characters and fleshing out the concepts of humanity that the original was praised for by those of us who love it, Villeneuve included. Yet again, we see him

13 | FC3K

paying ardent respect for the origins of his directorial work without fear of insulting those who made them. Reverent enough but singular in his own vision, Villeneuve is determined on showing the audience what he wants to show, not what they want to see.

One more muscle he develops and flexes during this process is his growing interest in color and, more importantly, contrasting them so greatly. This is not to say his works prior to 2015 were at all unimpressive to look at, but we can see an evolution of his color palette as he strays away from grounded, tense dramas and the suffocating colors used within them to futures so beyond our imagination and horrors that are paired with equally intense uses of light, color, and shadow. I can just Google “Blade Runner: 2049” and be stunned by the stills, from the aforementioned polluted orange of Vegas to the neon purple of the Joi hologram to the sickening yellows of the cultivated divinity in Niander Wallace.

It’s such overwhelming beauty that aides in keeping us enraptured as we creep toward the realization that K is no one special, a reveal that employs the opposite approach of Arrival: we are shown the picture of the puzzle and expect to know this narrative of the Chosen One come to save his kind, only to be gut punched as our dreams of K (or Joe, as he adopts) turn to dust in our hands. We look down to see we’ve put the jigsaw together all wrong, led astray by our understanding of how Sci-Fi stories usually work. Dissatisfied in this truth, Joe becomes the lynchpin in his own story, rejecting his programming of hunting rogue replicants and sacrificing himself to get Deckard to his daughter, as “dying for the right cause is the most human thing (he) can do.”

NOTHING NEW UNDER THE SUN

In the same interview with Variety just before Arrival hit theaters, Villeneuve mentions that “it’s been a longstanding dream of mine to adapt ‘Dune,’ but it’s a long process to get the rights, and I don’t think I will succeed.” Never have I been more happy that someone I admire was so wrong.

I’m a more recent “Dune” convert. Actually, it was the announcement that Villeneuve was writing and directing a film adaptation that finally pushed me to pick up the book. It took me… a while to finish it. Many book fans, myself included, will warn against the impregnable first one hundred or so pages, filled with words that made

the eventual inclusion of an honest to God glossary for these terms in later publications a necessity (not to mention multiple indexes). As I trudged through the desert with Paul and Jessica on that first read, I admit I experienced some doubt in Villeneuve. I wasn’t sure even my favorite director and an absolutely star studded cast could pull it off, falling victim to the long-standing belief that Frank Herbert’s novel was simply unadaptable. Never have I been more happy that I was wrong.

After finishing “Dune” for the first time, I immediately and hungrily devoured the next few books in the series, my head dizzied with excitement as to just what Villeneuve would do. I thought back to the works of his that I had consumed with the same fervor as “Dune” and its sequels, starting to put the pieces of this puzzle together bit by bit, obsessing over the box art all the while. Even with all of the elements in front of me, I was still uniquely and unequivocally floored by Dune: Part 1 and, despite my expectations being in the stratosphere, doubly so for Dune: Part 2. In this nearly six-hour combined runtime, Villeneuve establishes himself as the director that has slowly, but confidently guided us to this green paradise of modern Sci-Fi that he himself helped curate. Every bit of craft and skill he picked up from his impeccable career is on display here - from his gifts of adapting hefty and deified source material, to his more recent command of visual grandeur with color and scale. He even dared to change crucial elements of the original story, specifically the ending and the entire character of Chani, to more fully realize Herbert’s original vision for Paul as a prophet of his own making, rather than a false one. A dangerous, but charismatic leader the likes of which Frank Herbert tried to warn us about all the way back in 1965. Not a single step was wasted by Villeneuve as he dreamed of the culmination of his childhood storyboard of “Dune.”

This is a photo mosaic puzzle people have known and loved for decades, one combining millions of smaller images to inexplicably come together and create a larger one. Fans, new and old, have labored over the gargantuan jigsaw with seemingly innumerable pieces, protective of their own ideas and interpretations. Villeneuve understands this and has such a precise and unique vision for what his “Dune” looks

like, how he sees the characters and interprets the plot, that they can be enjoyed as two separate entities, a true adaptation. There is no perfect adaptation of “Dune.” Villeneuve understands this too and takes care not to promise you the “Dune” you have in your head, but to show you the one in his. Additionally, for those unfamiliar with “Dune,” he doesn’t throw every single one of the 10,000 piece puzzle at you and expect you to build it yourself. He walks the impossibly thin tightrope of honoring the source material and explaining it, of showing us what’s been in his mind for the decades since he first storyboarded “Dune” as a child and realizing it with such grandiose spectacle and granular detail, a living, breathing ecosystem that only passion and dedication of the highest order could have seen the fruition.

Octavia Bulter, a science-fiction powerhouse, stated “there is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” I came across this quote when reading an album review and the author, New Music, described it like this: “The aphorism could apply to any art form where the basic contours are fixed, but the appetite for innovation remains infinite.” Sci-fi, in one form or another, has existed since Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein. So, to say the form is well and truly fixed would be an understatement. How fitting is it, then, that Denis Villeneuve has sewn together parts of his experiences as a filmmaker to put his dream together, to harness the electricity of his passion and create his masterpiece? How thrilling it is to bear

witness to a once in a generation event like the culmination of Denis Villeneuve’s career and equally exciting to know that he’s not done yet. A new sun that is unparalleled in its brightness and designed to last and inspire; one capable of unrivaled potential in the years to come. •

15 | FC3K

A STILL FROM DUNE: PART TWO (2024)

Post-Nuclear Ecologies and Zoologies:

Them and Gojira as Eco-Horror Reactions to the Bomb

BY ROBERT KARMI

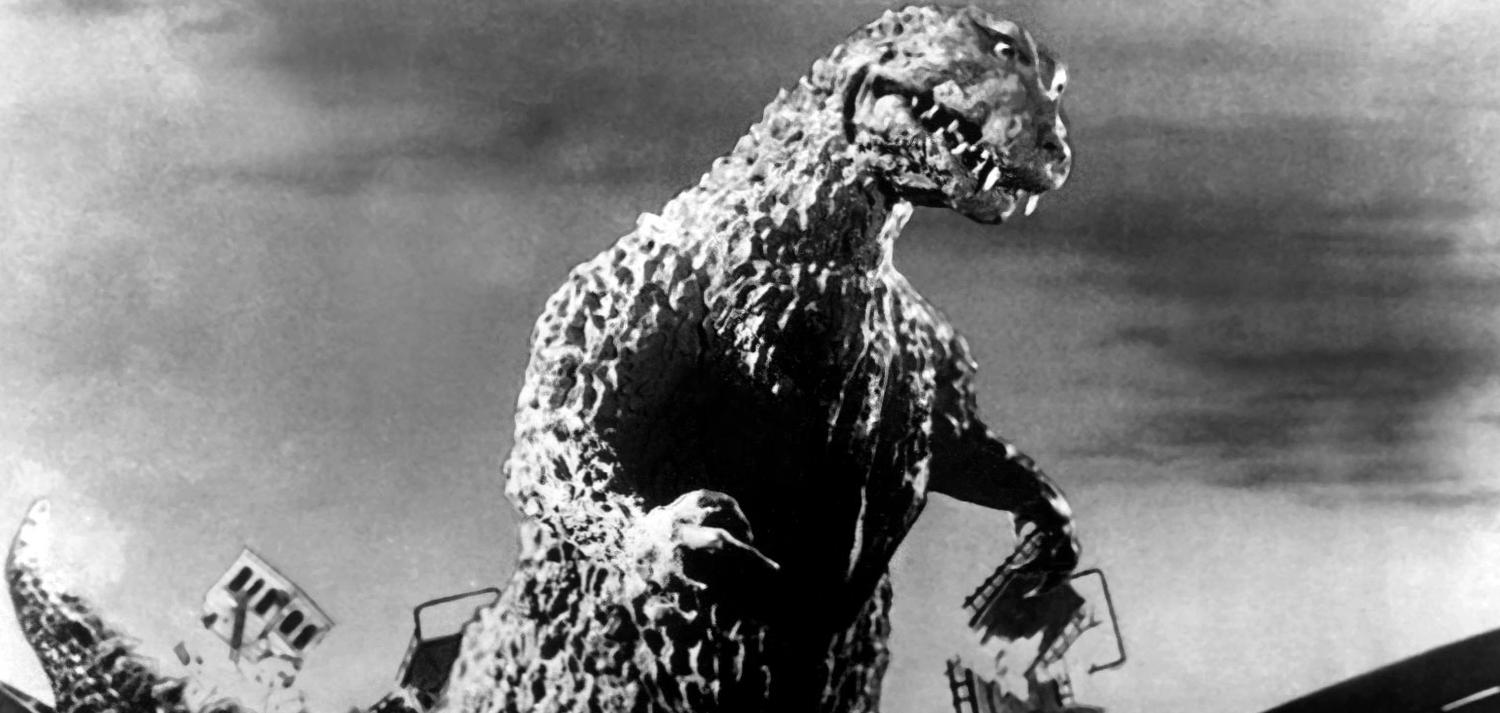

The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, released in 1953 and directed by frequent Jean Renoir production designer Eugène Lourié, is frequently remembered for its significance to two different Rays. The first, Harryhausen, whose effects work on the film hopes to solidify his reputation as one of the all-time great effects wizards in Hollywood cinema. The second, Bradbury, with it being (however loosely) the first major adaptation of his work. The film best resembles in places the Superman short film The Arctic Giant, wherein a long frozen prehistoric reptile awakens and goes on a rampage within civilization, with only one segment of the film being an adaptation of Bradbury’s short story “The Fog Horn,” when it attacks the lighthouse. However, much more than any of those elements, the film’s legacy remains as debatably the first monster movie to embrace the nuclear age, laying down the groundwork for dozens of likewise structured and themed films to follow.

While the film is not explicitly about nuclear power specifically as an instigator of horror, atomic energy plays a substantive role in the work’s beginning and ending. The film’s inciting incident is nuclear testing in the frozen north which reawakens the titular beast frozen in the ice, the nuclear heat having melted the ice and resuscitated it. When the creature arrives in New York City, it proceeds to wreak devastation upon buildings and vehicles. It is eventually wounded by the military and its blood, filled with ancient bacteria, begins to make those who encounter it ill, which acts as a subtextual parallel to nuclear exposure symptoms. The film’s climax reaffirms the atomic age setting via a nuclear isotope-laden warhead which permanently ends the creature’s life. The films inspired by Lourié’s work would further elaborate on these narrative beats, and themes, and add their own to create a tapestry of nuclear monster movies. Yet, none rose quite as high

or as impactfully as its most direct successors, the dueling American and Japanese 1954 productions of Gojira and Them.

These films represent the true birth of the cinematic nuclear age, each articulating ingrown societal anxieties extrapolating upon the knowledge that we have created technology that can permanently alter our world. Both are works that externalize these fears within a corruption of the ecological world through its non-mammalian inhabitants, who in turn become metaphors for larger geopolitical conflicts happening concurrently and subsequently. They are also distinctly creations from separate and idiosyncratic cultures and viewpoints that foundationally shaped how each film operates and what it conveys. Suppose one is to understand the national mindset at the dawn of the nuclear age of these nations via the contrast between these nations. In that case, these films offer a rare opportunity to explicitly deconstruct their relation to each other, thanks in part to overlapping narrative elements that make each similar enough wherein some differences reveal their true identities, most notably of a nation that fears its own powers, and one that has the lived memory of those abused powers.

Both films follow procedural genre conventions, where varying governmental bodies investigate mysterious happenings and initially rural areas of their respective countries, each one highlighting in some part the distinct cultures that have emerged from these particular geographic locations. Each film treats the build-up to the reveal of their respective creatures with great solemnity, understanding that the stakes are dire even when these stories are initially on a small scale. Both films utilize high-contrast black-and-white photography to help further establish a sense of dread throughout, with intense shadows and low lighting that evoke a similar aesthetic to film noir. Both films see these initial local events steadily become increasingly na-

ESSAY

tional, escalating to the point of martial law and the state entering a disaster preparedness. Both films end in a victory over these corrupted entities of nature, punctuated with a looming fear of the future, understanding that the continued use of nuclear power will only exacerbate the aforementioned problem represented by the titular monsters, adding a note of caution to the revelries of victory.

With such overlapping narrative beats, one might begin to suspect that both films convey the same core ethos, yet they cannot in part because of the nuances of how they contrast, not just geographically but politically. While both take the viewpoint of a democratic process, and both ultimately highlight greater conservative trends, the specific locations and policies of the works contrast and reveal their true identities. Them is initially set in the southwestern desert and eventually finds itself in the metropolitan location of New York and remains firmly landlocked in its setting. Whereas Gojira first begins to take place on a rural island community off Okinawa before escalating its tensions towards Tokyo while maintaining a thorough connection to the oceanic origins of its titular creature, the climax even taking place underwater in the ocean. Such regional specificities not only compliments each megafauna that the narratives center on, but also communicates the varying ecosystems that exist within each country. The natural world comes to operate in interesting subtexts in both works as they relate to the ecology of the countries and the animals that exist within them. The desert and metropolitan locales of Them reinforce the idea of a vast nation, with long stretches of land with sporadic and densely populated cities within them. By being so based in terrain environments, the work centers itself on two of America’s most readily identifiable biomes, the frontier, and the city. The vast, empty plans of the desert give way to subterranean tunnels, developed by the enlarged ants that make up the central antagonists of the work. By the time they move to New York, they only need to accumulate their environment sparingly, humanity having already terraformed the region for its own sake. As such, we can see the ants as analogous to ourselves, a war-faring, imperialistic species that transforms the environment around itself to suit its needs. Were it not for the exoskeleton or the extra four legs, we might see them as more parallel to us. Contrast that with Gojira, where the titular

creature is nautical, preferring the depths of the ocean and attacking water adjacent locations than going further inland. The first individuals to encounter him are seafaring folk, fishermen, and island natives who maintain their own culture separate from the mainland of the island nation. Unlike the anthropoids in Them, the creature Gojira’s destruction is more elemental at first, occurring during oceanic storms, with similar devastation and events analogous to a typhoon. Gojira becomes more connected to environmental disasters rather than the seemingly more human-like existential threats posed by the ants. Then, much like the insects, it becomes increasingly evident it has been corrupted by nuclear power, as it makes landfall and destroys Tokyo via its immense shape and fiery breath. That fire, weaponized by the creature Gojira and utilized against the ants, becomes as sure a sign of the inferno created by nuclear power as any in either film.

The greatest difference between the two films is in part the role that the bomb plays in the origins of the narrative, i.e., how their experiences with nuclear energy shape its placement within the narrative. Them, the American production, creates a scenario in which the ants become irradiated and mutated via the initial series of nuclear tests in New Mexico, thus making the insects a byproduct of American nuclear might. Gojira, the Japanese production, creates a scenario in which its titular monster is directly caused by similar nuclear testing by American forces in the Kojin Sea, and when it begins to attack Japan, it evokes and recreates similar destruction, and vistas the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The American production makes its creatures a byproduct of the ensuing atomic age, a tragic mishap wherein the fallout affects us too. The Japanese production transformed the fallout of the bomb used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a direct consequence of American nuclear power and as a manifestation of the continuing trauma of the event.

Despite these ecological themes, these films are most readily interpreted through geopolitical lenses, as both also represent early iterations of Cold War cinema. Them has been read in part as an anti-communist metaphor, with the ants acting as a uniform, collectivist unit working for the greater service of the colony against the individualistic American forces. The allegorical

17 | FC3K

reading certainly tracks, especially when you consider that likewise the film acknowledges the tensions also built by the Cold War, but it is hard to graft a strictly communist read onto an insectoid species that is frequently described in terms of feudalism. Yet the metaphor persists, especially as anxieties of a homegrown Red takeover abounded in the imaginations of American civilians, exacerbated in part by the Soviet’s own growing nuclear capabilities. For an American audience, the long-standing subtextual fear that someone would do to them what they have done to others would remain true within the atomic age.

Gojira exists within the context of not just the initial stages of the “atomic backlash” films as Dave Kehr might call such works (a term he used to describe Them), but also Hibakusha cinema, or survivor’s cinema. These films, made by the Japanese towards the end of the American occupation of the country, existed as a means to express cinematic catharsis in the face of the nuclear warfare that they had experienced. The earliest iterations of the movement include Kaneto Shindō’s Children of Hiroshima and Hideo Sekigawa’s Hiroshima, released in ’52 and ’53, respectively. While both are incredible works of cinema unto themselves, they cannot help but fall into obscurity via the ubiquity of Gojira, which through the lens of sci-fi horror creates a more palatable and subtract means of confronting the underlying horror of American occupation and investment in Japan after the bombings. As the series would continue,

becoming increasingly kitschy over the decades, that lingering subtextual tension would remain steadfast, the creature Gojira as a manifestation of American will over Japan, sometimes antagonistic and other times platonic, but always self-interested.

Them communicates the anxieties that Americans will one day either face another nuclear power or that they will suffer the consequences of their own nuclear capabilities, whereas Gojira displays the lingering scars of the bomb’s usage on their citizenry as a concrete reality. One work seeks to express unrealized phobias, whereas the other exists as a manifestation of the living memory of rapture. Each end in apocalyptic violence committed against these specters of an incumbent atomic catastrophe, each worrying about how such radiation and human callousness may further damage the world. While their respective offspring would become increasingly kitschy and harder to engage with strictly in terms of social messaging, these two films laid the groundwork for the horrors of the atomic age to express themselves cinematically. Them and Gojira, each one a singular and distinct reaction to the bomb, are nevertheless forever entwined by the larger relations of their nations. •

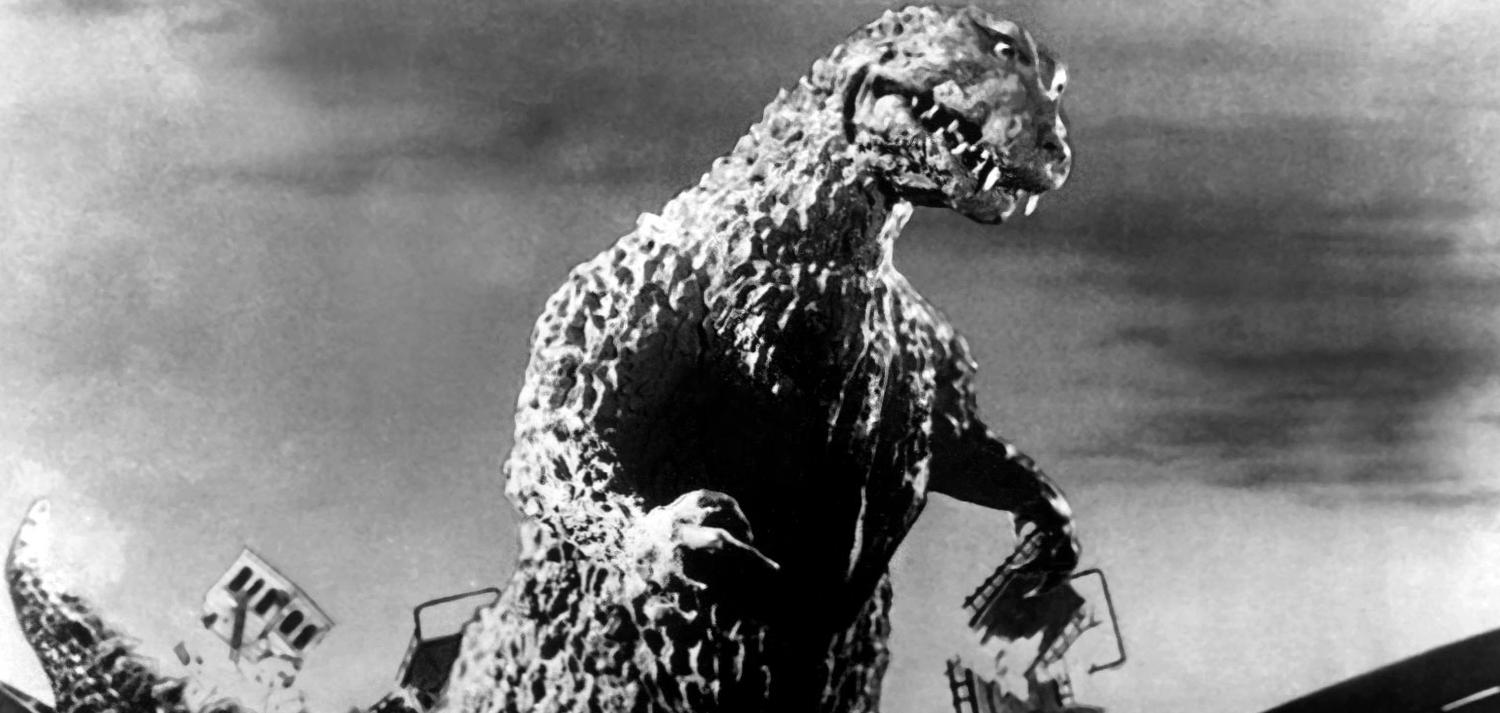

STILL FROM GODZILLA (1954)

ORIGINAL POSTER FOR THEM! (1954) 19 | FC3K

21 | FC3K

23 | FC3K

ARTISTS

VICO SANTOS @THEVICOSANTOS

CONTRIBUTORS

GARRETT BRADSHAW is a graduate of UNC Greensboro with a BFA in Theater. His love for storytelling spans books, games, plays, television, and movies, all of which he loves writing about. He is a current resident of Atlanta, GA.

ROBERT KARMI graduated from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington’s film program with bachelor’s and master’s degrees emphasizing critical studies. One professor opined Karmi was omnivorous in his study of cinema, leading to the title of his review blog Omnivorous Cinephilia. When not working on entering a doctorate program, Karmi writes about whatever film subject interests him through multidisciplinary theoretical lenses. He is also on Letterboxd.

C.C. LILFORD is a happily married writer, critic, arts journalist, and amateur art historian. They love all of the arts (don’t get them started on opera or Prince’s discography) and try not to pick favorites, but their masters degree is in film studies. When not writing C.C. can be found adding to or maintaining any one of their extensive libraries.

JUDE MICHALIK is an aspiring filmmaker ever hungry for poetry in all forms. Living in between Milan and Paris, she’s looking to birth beautiful things, foster genuine connections, and contribute as much as she can to the world of art. If one would like to reach out, she can be found at @judesdelusions on Instagram.

25 | FC3K

“MY PURPOSE IS TO MAKE FILMS THAT WILL HELP PEOPLE TO LIVE, EVEN IF THEY SOMETIMES CAUSE UNHAPPINESS..”

– ANDREI TARKOVSKY

27 | FC3K

DENIS VILLENEUVE BY JACK DAVISON

DENIS VILLENEUVE BY JACK DAVISON