About Film Club 3000

Letter From the Editor

Kemari Bryant

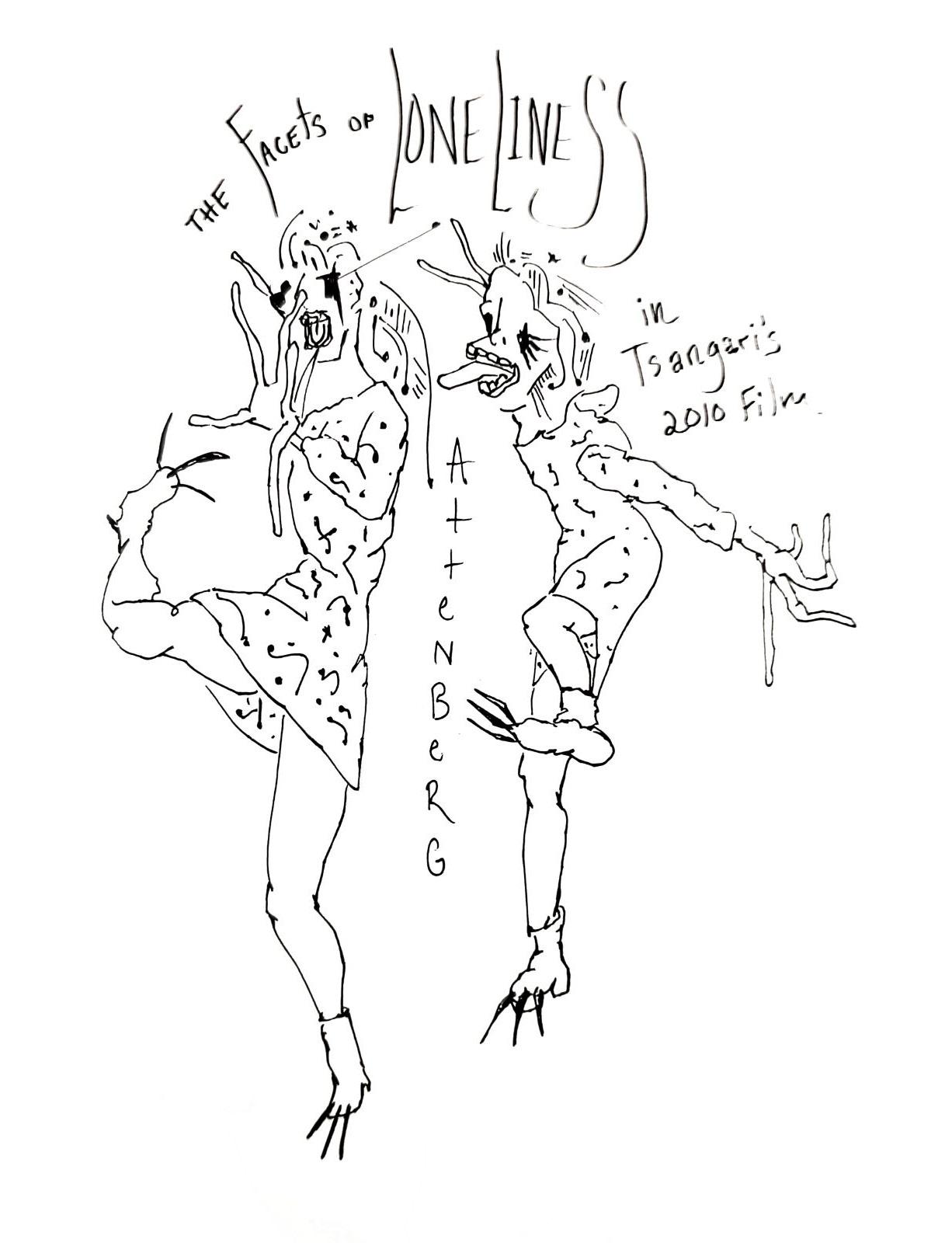

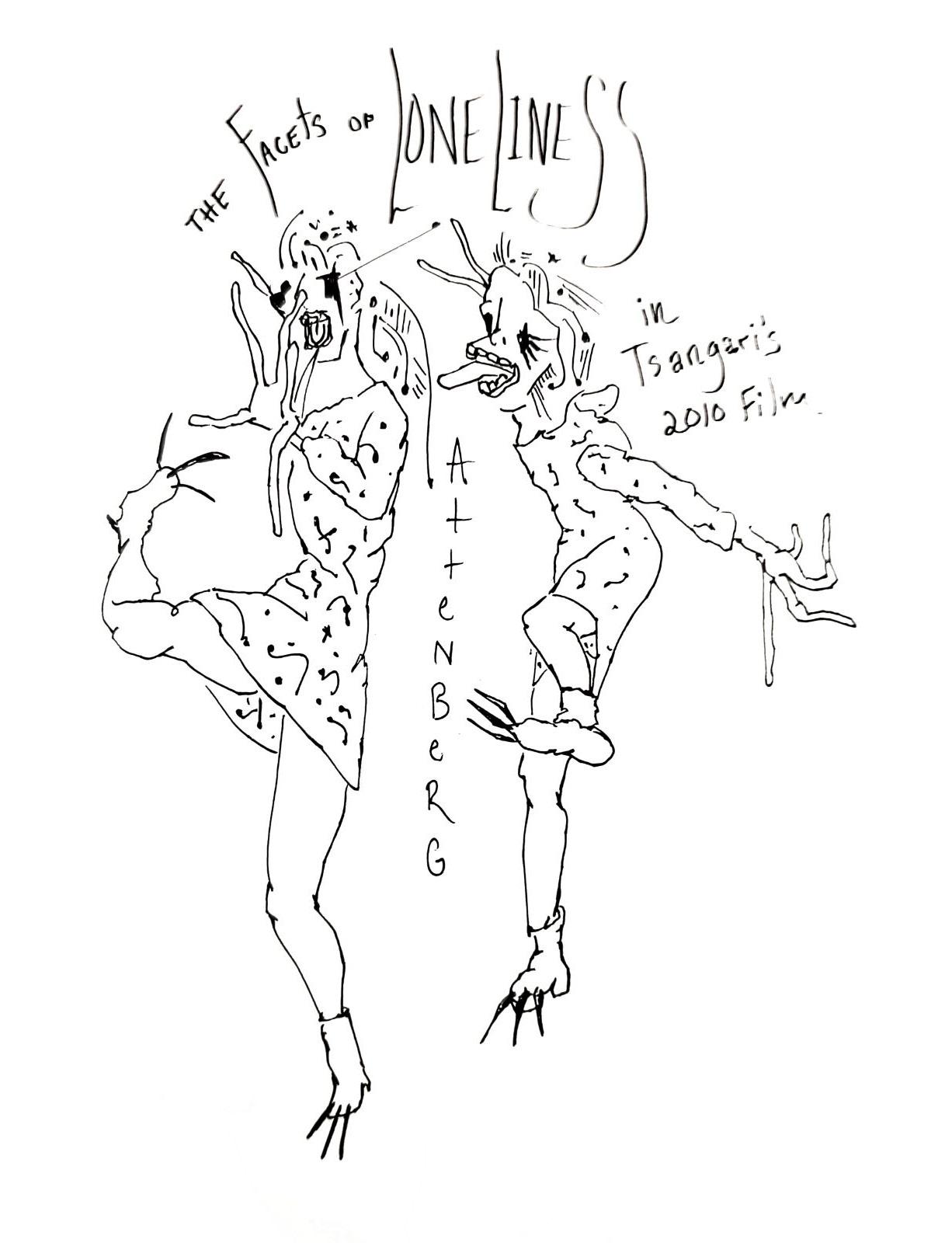

The Facets of Loneliness in Tsangari’s 2010 Film Attenberg

Jude Michalik

The Greek Queer Wave: On Strella & The Weird Wave as a Queer Movement

Robert Karmi

Unpeeling Apples: How Frail Our Souls Can Be

Garrett Bradshaw

Context-Dependent Love: Love in the Films of Yorgos Lanthimos

William Reynolds

Chevalier

Sisyphus Plays Trivial Pursuit

Tanner Benson

History Repeats

An Examination of the Greek Realist film

The Ogre of Athens

Robert Karmi

The Emergence of the Greek Weird Wave Within the Film Festival Circuit

Theodoti Sivridi

UPS

Interrogating Biopolitical Realism: An Interview with Author Dimitris Papanikolaou Kemari Bryant

A Conversation with Argyris Papadimitropoulos: A Leading Voice in Greek Cinema Kemari Bryant

A Close-Up on Yorgos Sakarellos

Harissa Bakllava

Mixology by Cameron Cameron Linly Robinson

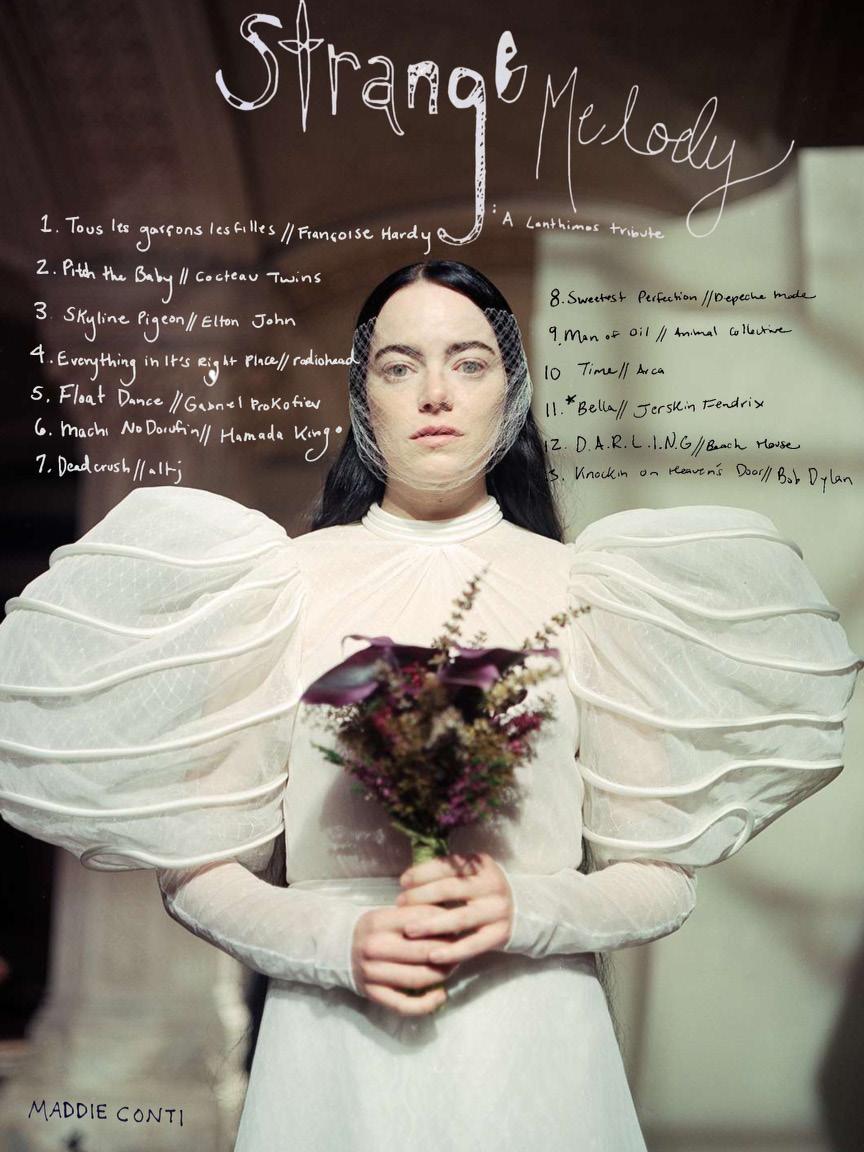

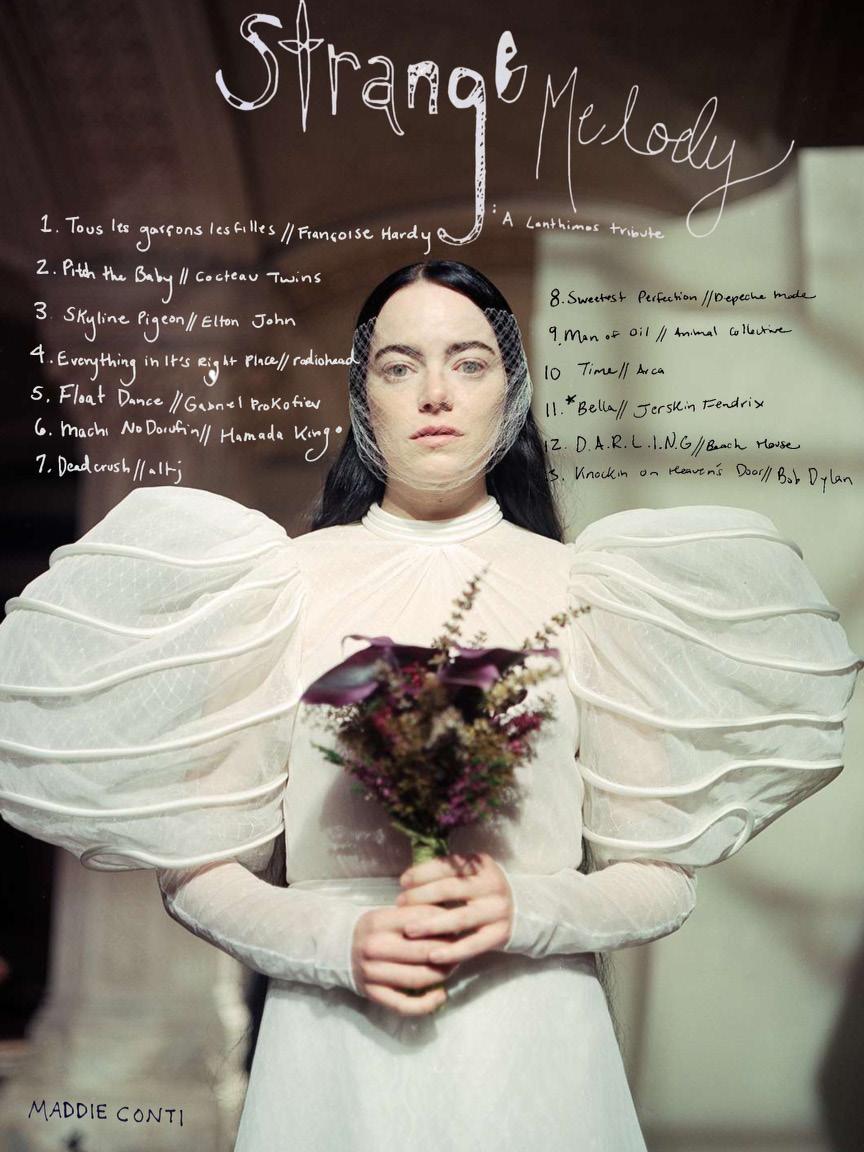

Strange Melody: A Lanthimos Tribute

Maddie Conti

Watchlist 3000

Issue 003 | Jan/Feb 2024

CONTENTS

ESSAYS ESSAYS

08 38

20

CLOSE

3000

ii. iii. OVERVIEW ANGELIKI PAPOULIA IN DOGTOOTH 12 16 26 34 42 01 31 48 54 55

ABOUT FILM CLUB 3000

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

KEMARI BRYANT

MANAGING EDITOR

CAMERON LINLY ROBINSON

CONTRIBUTORS

JUDE MICHALIK

ROBERT KARMI

GARRETT BRADSHAW

WILLIAM REYNOLDS

HARISSA BAKLLAVA

TANNER BENSON

THEODOTI SIVRIDI

MADDIE CONTI

COVER ART

WILLIAM HARVEY

ILLUSTRATORS

HARRIS SINGER

ALL VIEWS AND OPINIONS ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHORS AND DO NOT NECCESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS HELD BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF.

WEBSITE

FILMCLUB3000.COM

INSTAGRAM

@FILMCLUB3000

CONTACT

FILMCLUB3000@GMAIL.COM

EVANGELIA RANDOU AND ARIANE LABED IN ATTENBERG. COURTESY OF MUBI.

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Dear Readers,

It is my great joy that we are finally able to bring you issue 003 of Film Club 3000. This has been a very difficult one to bring together, but has driven home my belief in why we do what we do.

It is impossible to have a true love for film without also recognizing and respecting the essentialness of world cinema, and I am so lucky that we are able to fully delve into the glory of Greek cinema in this issue. I was introduced to Greek cinema through the great director Yorgos Lanthimos, along with a majority of America filmgoers I can only assume. Lanthimos’ films led me to the Greek Weird Wave whose title did the job and left me endlessly interested in how I could find out more about these “werid” films. I curiously discovered that these films are so much more than “weird”, as critics decided to title them, they are bold expressions from ingenious filmmakers who had something to say during rather tumultuous times.

The work on this issue has really led me to think about accesibility. There are so many Greek films that are impossible to find, or take a good amount of work to unearth from the bowels of the internet. One of the most underappreciated aspects of filmmaking is that of the audience... and I don’t just mean when the film is released, but what about 10 or 15 years later? The audience is what keeps a films legacy alive. My one wish is that you read this issue and find one or two new Greek films that you will go and watch. Tell your friend to watch it, and maybe they’ll tell their friend, and so on. We must demand these stories so they stay, and so that more will come.

And there are so many stories.

Enjoy, to 3000 and beyond,

Kemari Bryant | Editor-in-Chief

FROM DOGTOOTH. COURTESY OF SHOTDECK. iii | FC3K

THE COVER OF “GREEK WEIRD WAVE: A CINEMA OF BIOPOLITICS” WRITTEN BY DIMITRIS PAPANIKOLAOU

Interrogating Biopolitical Realism:

An Interview with Author Dimitris Papanikolaou

BY KEMARI BRYANT

What is biopolitical realism? It is a term created by author Dimitris Papanikolaou to describe the wave of Greek cinema released in the late aughts, perhaps a more thought through term than the “Greek Weird Wave” which was quickly coined by nonGreek journalists and stuck as the official name to describe this influential movement in world cinema. Steve Rose of London’s The Guardian can be recognized as popularizing the phrase, and The New York Times’ John Anderson went further with pushing it forward as the term-to-goby in his 2013 article highlighting Greek cinema. However, it could be argued that out of all, Dimtris Papanikolaou would know best. Papanikolaou’s book “Greek Weird Wave: A Cinema of Biopolitics’’ is one of only two books available on this period of Greek film, and his decision to look at cinema from a biopolitical perspective allows access to a whole new world of understanding these films.

I sat down with Papanikolaou on a video call, where he talked with me from Paris about this term, “I jumped on a chance to encounter this obnoxious term ‘weird wave’.” He noted how colonial the very idea of the term was – Greek filmmakers attempting to share their art, to allow others a look at their realities and they were met with having their work called weird. Papanikolaou didn’t find that this was such a huge problem, though. “I thought, okay we’ll play with that. I’ve wanted a term to showcase what I believe was a biopolitical reality, and the very strange biopolitical realism that all of these films were managing.”

CLOSE-UP 01 | FC3K

A CINEMA OF BIOPOLITICS

Everything started with a book on the Greek family.

Papanikolaou had decided to venture out and create a book based around the representation of the Greek family in cinema. During his research he realized that the more recent films were not about the supportive network of kinship that is normally perceived to be the Greek family, but explored families that were violent, abusive, and oppressive to the point of explosion. Slowly all of the content that surrounded him – smaller films, theatre, performance art – they all returned to this idea of an explosive Greek family. Then the Crisis hit.

“My generation lived through what was called the Greek Crisis. Around 2008-2009 it seemed that everything in Greece broke loose. First with social strife: in 2008, following the killing of teenager Grigoropoulos by a policeman, you had huge mass demonstrations all over the country. They seemed to be about a malfunctioning society, and not only about police brutality. And then, very shortly [as a result of the global financial crisis] you have every single side of the economy falling apart. So, very early on, we were aware that something huge was happening, something historical was happening in our country.” The Greek Crisis, referred to henceforth as simply the Crisis, began to bring international attention to the country, but not necessarily positive attention. However, at the same time, Greek’s cinema also began to be noticed. “It was at that time that some films with families in tatters started becoming more and more acknowledged both nationally and internationally. It’s the Dogtooth moment.”

The Dogtooth moment Dogtooth, directed by Yorgos Lanthimos, is the brutal display of a husband and wife couple who keep their children ignorant to the world outside of their home even as adults. “I remember seeing it in the Winter of 2009 and I remember thinking this is a very awkward film. And then it grew on us that it was something more than that.” It grew indeed, going on to win the Prix Un Certain Regard at Cannes Film Festival in 2009, an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, and love from critics interna-

tionally. Did it take a financial crisis to turn international audiences toward the cinema of Greece? Still, at the core of it all was family. “So the family started it all, and suddenly the films came. It was as if I had made the frame in my mind and every single film I was watching was actually adding to it.”

Papanikolaou had been thinking about these sub-themes in Greek cinema: violence, intergenerational gaps, family (as) archive, (queer) kinship, oppression. Just as he was forming thoughts on these themes it was as if the Greek Weird Wave was being formed in real time. The book is a product of long gestation of many years of work, including his own work as a social activist – in particular, queer activism. As he was putting together the book and crystalizing his ideas around biopolitics, in September 2018, a trans-queer activist and acquaintance, Zak Kostopoulos/ Zackie Oh, was killed in broad daylight in Athens – an act of everyday violence and of police brutality captured on camera by passersby. Papanikolaou found himself mobilized, along with many other Greek citizens, to underline the deeper social issues that once again this brutal killing was foregrounding. Indeed, the last chapter of “A Cinema of Biopolitics”, is dedicated to the killing of Zak Kostopoulos.

The 2011 film Wasted Youth (directed by Argyris Papadimitropoulos and Jan Vogel) mirrors the real life murder of 15-year old Greek student Alexander Grigoropoulos, an event that spurred another moment of social unrest in the form of riots that took place for a month, and were described in the newspaper “Kathimerini” as “the worst Greek has seen since the restoration of democracy in 1974.” So Greece was in the midst of terrible financial straits and crippling social conflict, but the films that began to gain traction were in the end the ones that took a more allegorical integration of political issues.

Papanikolaou describes a fission in Greek film: there were the films that were in direct response to specific events or the general social issues like Wasted Youth, or The Boy Eating the Bird’s Food, which follows a young man who is struggling and must steal bird food to survive,

or even Yorgos Zois’ Casus Belli, which also explores food insecurity in Greece. “The films that became much more successful abroad, [however], were films that were working at a much more allegorical level.” These were the films of Lanthimos, like Dogtooth and Alps, or Athina Rachel Tsangari, who directed Attenberg. Papanikolaou wanted to discover how he could push these more allegorical films to see how they also related to reality.

There was a challenge in putting together such different films as the extreme violence in Alexandros Avranas’ Miss Violence, the allegorical films of Lanthimos, films that fell in the middle from Syllas Tzoumerkas, the eloquent film study of Tsangari, and the social realism of Papadimitropoulos – a much more diverse collection of films than the simple phrase “weird” could seemingly contain. “Lets play with the term weird, and start foregrounding its obvious limitations — [because, you see], you want “The Top 20 Greek Weird Wave films” to be available on [an international] platform, in order to be able to [persuade producers to fund] your next film about a racist killing in Central Athens.”

This is where the term “biopolitical realism” comes from. “I wanted to create [a term] that would at the same time include the allegorical films of Lanthimos and of his close colleague Tsangari, and, say, the queer films of Panos H. Koutras, who works with issues of queer identity, migration, citizenship and racism, and I wanted to bring them together.” In the midst of all of this uncertainty and conflict, the cinema of Greece somehow managed to craft a cultural exploration larger than it all. Inside of all of its multiplicity there was a core similarity – not “weirdness”, which today seems like a gross oversimplification, but a biopolitical reality and the efforts to make a noise within it. Biopolitical realism as the link between all these films gives autonomy to these filmmakers as artists who were allowed to create art within their situation, but not be defined by it.

A CINEMA OF DISLOCATION

While the beginning of the Weird Wave can often be attributed to both Tsangari and Lanthimos’ international success, Papanikolaou posits that the Weird Wave had been bubbling up in the background for years. “This is a generation that, before the Crisis, was working on a number of projects — including the 2004 Olympics — as well as other very commercial projects. Lanthimos was doing advertising and comedies. At the same time a larger group of people had started preparing what you saw as the Weird Wave, preparing the moment of explosion.” Angeliki Papoulia is an actress and longtime collaborator of Lanthimos, playing Older Daughter in his film Dogtooth. “[Papoulia] has become the darling of European cinema at the moment. There are film festivals in Europe that do a Papoulia special,” Papanikolaou told me. “Before that, though, she was in a the-

TOP: MARY TSONI AND ANGELIKI PAPOULIA IN DOGTOOTH. COURTESY OF SHOTDECK.

03 | FC3K

BOTTOM: WASTED YOUTH STARRING HARIS MARKOU. COURTESY OF MUBI.

atre group with [her co-protagonist in Dogtooth] Christos Passalis called blitz, a theatre group that actually specialized in talking about identity, dislocation, the feeling of not belonging, of being marginalized, on various levels including gender and national identity, the fear of fascism rising, the fear of the fortress Europe.”

The blitz theatre group was founded in 2004, and Papoulia acted, co-directed, and co-wrote all of the group’s performances in Greece and across Europe. The group’s website states “...everything is under doubt, there is nothing to be taken for granted, neither in theatre nor in life.”

Ariane Labed, the star of Attenberg and who would later marry Lanthimos, is another good example. She was born to French parents and came to Greece at a young age. In college she met Greek director Argyro Chioti and, in 2005, together they co-founded the theatre group VASISTAS – a physical theatre all about dislocation. A big part of Labed’s work around dislocation was her heavy-accented Greek. Fast forward to 2010’s Attenberg, with Labed at its center and in a film, arguably, completely being about dislocation and one’s inability to connect with others. Then there is Michelle Valley, the Mother in Dogtooth. “ [Valley] is a Swiss actress who came to Greece in the 80s and started playing in Greek art cinema without knowing the language.” He goes on to explain that she always had this dislocation, and in, say, films like Morning Patrol (1987) and Singapore Sling (1990), a deadpan delivery that may remind one of what actors later do in many a Lanthimos film.

I decided to bring up a recurring theme that I often found in Greek Weird Wave films: loneliness. He was quick to challenge this, “I think the dominant theme is dislocation rather than loneliness”. Dislocation, a term I had never really thought about but that made so much sense when looking back at this collection of films. He would go on to explain, “In South Europe, we realize more and more how much a part of the Global South we are. South Europe has a longstanding reason why we feel dislocated. In Greece you’re supposed to be thinking of yourself as European, but you’re not enough. You’re in the East, but are supposed to be thinking of yourself as belonging to the West. You’re supposed to be working with new Neo-liberal models of production and social control, but then again you don’t have the economy for that.

We tend to be highly educated because we have free education, but then again we’re being told not to believe in that education because it’s not as good as it is elsewhere. “

Dislocation rather than loneliness, it made so much sense. Such a thin line between the two words but a world of meaning that exists between them both. Dislocation speaks to more of a disturbance or a change, and is, even if ever so slightly, different than what loneliness is. He went on to joke, “I wouldn’t say that I see more lonely people in Greece than elsewhere. In a Greek restaurant everyone talks to you — they will not let you be alone. That’s perhaps the most unrealistic thing you see in recent Greek films: that you see people eating alone.” This idea of dislocation is something you can see very clearly in Attenberg, in Papadimitropoulos’ Suntan, and in Lanthimos’ Alps, among many other Greek films historically.

“Loneliness is just the tip of the iceberg”, he says. It is just the tip, indeed, but he doesn’t completely downplay Greek cinema’s connection to the feeling. “Rather than loneliness, I would say that what characterizes recent Greek cinema is emptiness. Greek cinema is a cinema of empty spaces – to extreme degrees.” Suntan begins with a Doctor arriving on the Greek island of Antiparos in its off season, certainly lonely but more attention is drawn to his being thrown into a new and empty place – a summer-paradise island during a time when no one occupies it. “It’s not about them being lonely, it’s about the street being empty.” He goes on to bring up The Truman Show, the 1998 film about a young man who has to live in a TV studio 24/7, thinking that this is the only possible world. “Was [this film] about loneliness or dislocation? That kind of constructed emptiness – fullness and emptiness.”

A CINEMA OF HISTORY

In 2021, in the midst of the pandemic and lockdowns, Greece celebrated its 200th year of independence. Suddenly, there was an international move to examine the country’s political and social history. Along with this, came the need to review Greek cinematic history; Papanikolaou became part of a team that curated a special festival, and published a book, “Motherland, I See You: The Twentieth Century of Greek Cinema”. It was an effort to showcase the fact that Greek filmmakers had been making a point to look back at Greek film history for quite a while. While the Weird Wave was finding its footing, the Greek film industry was simultaneously being shaped by a film movement called FOG – a double entendre meaning Filmmakers of Greece and also representative of the filmmakers themselves trying to find their way through their current fog. FOG would

put together screenings and after-screening parties inspired by films that had been forgotten to time, an effort to actively reshape their own understanding of their national cinema. Suddenly, a cinema tradition that had been forgotten was being revitalized.

“Film canons are the international canons. It’s difficult to have a national canon thriving and if there exists one, it is often a popular cinema tradition [...] Avant-garde film, arthouse film does not a very strong national canon make.” He points out some filmmakers that had been successfully added to the international canon, like Theo Angelopoulos whose film Eternity and a Day won the Palme D’or at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival, or classic realist films like Nikos Koundouros’ The Ogre of Athens. What began to emerge around 2010 however, was an interest in curating Greek film history as a contemporary platform of inspiration and expression. Often many actors known for starring in Weird Wave films would be presenting films from the past. Papanikolaou recalls a time where Angeliki Pa-

A STILL FROM ETERNITY AND A DAY, 1998 PALME D’OR WINNER, DIRECTED BY THEO ANGELOPOLOUS 05 | FC3K

poulia spoke beautifully at a screening of the 1956 film A Girl in Black, by another realist Michael Cacoyannis. In this moment of historical film appreciation the other shoe dropped when filmmakers began to realize that they couldn’t find some of these films. Some went from door to door, actively searching for historic Greek films that had been lost or damaged. He describes the work they were doing as a sort of “genealogical exercise”.

Papanikolaou explains that during this period a filmmaker, Niko Papatakis, began to be re-discovered. “He did a film just before the great dictatorship of ‘67 called Shepherds of Disorder, which I remember watching for the first time again in the 10s in a screening. I remember thinking, ‘Lanthimos is there already [in 67]’.” He goes on to describe Papatakis’ film, how it includes characters speaking in stilted or monotone dialogue, how violence is a leading factor, and how it pushes against the Greek family. “It shows that the Greek family is a center of exploitation or abuse within the system.”

This line of thought led into our next point of conversation: accessibility, especially as it pertains internationally. “Accessibility is the issue,” he declares. So many great films that are impossible to access outside of Greece, or that are similarly lost to international audiences. He goes on, “We subtitle Greek films, we digitize Greek films all the time even to send as screeners to festivals, and then we forget about this and there’s no way to watch.” There is initial access but oftentimes, as time goes on, films become only accessible to those rare film viewers who are willing to go out and search endlessly for them. This is where the importance in archiving world cinema comes in. “We forget [how difficult it is] to find our own cinema traditions, and it has to be curating. It has to be getting together with people. It has to be fighting. It has to be creating interesting communities.” All types of communities – communities of watching, communities of cin-archiving, communities who demand their audiovisual history and are ready to fight for it, as Papanikolaou puts it.

“Sometimes in film studies we forget that history, writing, film criticism, film viewing, and film archiving are all [existing] together.”

“We forget [how difficult it is] to find our own cinema traditions, and it has to be curating. It has to be getting together with people. It has to be fighting. It has to be creating interesting communities.”

A STILL FROM THE SHEPHERDS OF DISORDER (1967) DIRECTED BY NIKO PAPATAKIS. FILM AT LINCOLN CENTER, 2018.

A STILL FROM THE SHEPHERDS OF DISORDER (1967) DIRECTED BY NIKO PAPATAKIS. FILM AT LINCOLN CENTER, 2018.

A CINEMA OF THE FUTURE

What happens in the wake of a monumental national film movement in a small country like Greece? Of course more films were created. Yorgos Lanthimos is now Greece’s most known filmmaker, an internationally received auteur who weaves through different genres and continuously pushes his skill as a filmmaker. Athina Rachel Tsangari continues to work internationally as a director and producer, in both film and television, and even produced Richard Linklater’s 2013 film Before Sunrise which shot in Greece. She has a new film that will be released in 2024. Christos Nikou, who Papanikolaou describes as a “disciple to Lanthimos”, has gained international attention as a director of Apple TV+’s Fingernails Inside, another 2023 film starring Willem Dafoe, is directed by Vasilis Katsoupis, a filmmaker who he points out is from the same generation that the Weird Wave stemmed from.

For better or worse, international attention has been captured due to the title “Greek Weird Wave”. However, Papanikolaou looks towards the future.

He says he notices a new development in cinema coming from Greek filmmakers, films that build upon the practice of “weird” but tackle social issues that are realistic in a very classic way. These films all attack specific issues to do with work, education, exploitation, racism, and gender violence in ways that do not let the form become documentary. “In order to do biopolitical realism, as Truman in The Truman Show knew very well, you have to be both documentarist and awkward. To somehow dislocate that camera that follows you around in the film, that biopolitical ordering that has you,” he explains. The aspects that make these latter films feel like a documentary are there co-existing with the weird. “I see all sorts of interesting things happening there about the body, about showing Neo-liberal politics. But at the same time, with all the formalist

background that they have with the weird wave, getting the viewer in to feel pain. To feel dislocation. In a couple of recent Greek films I was even surprised to see the extent to which they even employed a certain type of magical realism — without losing their documentality.”

He references a Greek-American, Araceli Lemos’ film Holy Emy (2021), which blends mysticism with the very raw reality that exploited migrants have to face in Greece. Something similar is what Evangelia Kranioti does in her medium-length Obscuro Barroco (2018). In fact, every filmmaker Papanikolaou poses as being at the forefront of this new look into Greek filmmaking is a woman, which is of note as Tsangari is really one of the very few leading female figures in the Greek Weird Wave. He highlights Konstantina Kotzamani, who directs a 2019 film Electric Swan, and a film by Sofia Exarchou in 2023, Animal – which he describes as a feminist answer to Suntan. Exarchou has roots in the Weird Wave, having served as 1st AD on Wasted Youth and Koutras’ Strella: A Woman’s Way. “[These directors] have a tendency to do more and more social realism with the weird [in a way that] actually takes my vote.”

Perhaps we are moving into a new era of Greek cinema, only time will tell. What is clear, more than anything, is that this movement in cinema is one that will remain firmly stamped in the annals of film history. Dimitris Papanikolaou’s book exists forever as a great record, and his knowledge is treasured as a historian and expert on Greek cinema. As we neared the end of our time he left me with something, as earnest as possible, that encapsulates the Weird Wave and mirrors my hopes for the future of the Greek film industry, “It’s very nice that Lanthimos has happened, that he exists. He is just the tip of an iceberg, though.” Papanikolaou hopes that people will keep taking a dive. •

07 | FC3K

STILLS FROM ANIMAL DIRECTED BY SOFIA EXARCHOU, HOLY EMY DIRECTED BY ARACELI LEMOS, AND ELECTRIC SWAN DIRECTED BY KONSTANTINA KOTZAMANI.

ESSAY ART BY HARRIS SINGER

BY JUDE MICHALIK

In the land of industrial landscapes layered atop almost mythically imposing nature, a web of peculiar relationships entangles the protagonist of Athina Rachel Tsangari’s Attenberg. Marina (Ariane Labed) embodies a spine-reaching feeling of inadequacy, possible only through the fever dream absurd of her demeanour. Love, intimacy, and friendship all taste of the unshakeable feeling of alienation explored throughout the film, enveloped by language and tapping into the uncomplex ways of animals.

The first image welcoming our eyes is a prolonged shot of a deteriorating white wall. The viewer’s sight is left to wander, free to notice various cracks revealing slightly off-white cement, a gentle reminder of the passage of time. Through this raw nakedness of exposed flaws, even though inanimate and cold, the wall begins to resemble something intimate.

In such a way, the themes of Attenberg begin to blossom, soon to reveal a rich range of reflections upon the wrestling of alienation with attempts at intimacy, the desire to return to primal ways of being, and the heartbreaking conclusion that we can no longer do so.

The core thread of the story, and perhaps its most interesting component, is a child-like friendship between Marina and Bella (Evangelia Randou), two women in their twenties.

An uncannily girlish lesson on kissing marks our introduction to these two; with determined faces the women clash their mouths awkwardly together, moving in a way stripped of any

semblance of intimacy or eroticism. As their tongues wrestle in the air, we begin squirming in our seats with the discomfort of witnessing an erotic gesture deconstructed, performed as if Bella had read about it on paper the way thirteen year old girls do. Cold absurdity quickly washes over the scene, as the ritualistic fight of dry tongues transforms into a fight between cats: Marina and Bella get down to the ground and hiss at each other.

We watch, fascinated, as the women go from a deconstructed imitation of an intimate gesture, devoid of any feelings it usually signifies, to the raw physicality of expression the animal existence offers. These tides of interactions, scaffoldings of societal rituals evolving into freeing, boundaryless celebrations of the primal, are present throughout the entire film; often the two friends will completely shatter the course of a conversation, not even slightly altering its tone - as an example serves one conversation in a diner:

“How’s Spyros?”

“You mean Mister Spyros. It annoys me when you become so familiar.” Pause. “Bella, you little slut.”

“Do you want more bread?”

The discussion around societal norms and propriety of relations is abruptly followed by the simplest question of all, “Do you want more bread?”

We begin to notice that Marina and Bella behave the way children do, half-entangled in societal constructs, and half-wild, unadapted,

THE OPENING SHOT OF ATTENBERG: A DETERIORATING WHITE WALL. 09 | FC3K

uninitiated. They play the guitar to each other and spit out of windows, embodying half-remembered friendships of our past.

In this peculiar space of being they’re tied to each other, quietly acknowledging their own isolation, holding hands and looking at others with curious disregard. They inhabit frames swallowed by empty spaces and cold colour palettes, or stand visually separated from crowds. A scene highlighting this state of being beautifully is an evening tennis match between Marina and Bella. They play, enlightened by the tennis court, while in the foreground, in the shadows, sit grouped people their age. “Tous les garçons et les filles” softly envelopes our ears, reflecting in French on the melancholy sadness of being excluded from love. The foreignness of French in the Greek setting adds to the feeling of inadequacy, as if putting focus on the alienating nature of language. The way Marina and Bella speak is not insignificant either, throughout their conversations words are experimented with and stretched, repeated and swallowed.

The graceful title Attenberg is itself a mispronunciation of the foreign to the characters surname Attenborough. Misplaced in Bella’s mouth, the word becomes something in-between, in between Greek and English. Sir David Attenborough’s documentaries seem a passion of Marina’s, she watches as Attenborough gazes into the eyes of gorillas, transfixed by their quiet understanding. Something poetic lurks in this fascination with animals, a primal longing for a different existence, perhaps, more communal, more seamlessly carnal. In a beautiful scene, Marina and her father, Spyros, sit on bed and play what seems to be a word game. Rhyming words spill out of their mouths with no regard for the meaning, making us detached from the language itself and focused on the connection shared in the idle moment. Soon their words, spat out chaotically and hastily, transform into sounds of animals, and we watch on as Marina and Spyros begin a wild dance of various species, jumping and hurling around the bed giving into the most primal of movements. The hypnotic dance seems to express more than their words ever could, rejecting the stifling constructs passed onto them by language, giving them a chance to dream about a simpler life for a blissful moment. Loneli-

...throughout their conversations words are experimented with and stretched, repeated and swallowed.

ness seems to awaken deep-rooted longings in Marina and those she interacts with, and while their animalistic antics seem absurd to the viewer at first, in the universe of these characters they serve a deep purpose - they constitute a radical response to the overpowering ambience of heart rate monitors, empty streets, and modern ruins.

Animals and words can be found linked together in her affair with an out-of-town engineer played by Yorgos Lanthimos, a prominent Greek director. Their intimate encounters are led by Marina’s misled expectations as to what constitutes sex. Early on in the film we learn of her repulsion towards it, as opposed to Bella she doesn’t seek it out, even though she does display a certain curiosity towards sexuality. Repulsion towards sex in this context seems particularly significant if we consider the erotic one of the most primal impulses in man – the purely instinctive dance of flesh fueled by the heat of the moment, where the intellectual doesn’t dare to interfere.

When something sparks between Marina and the engineer she drives around town for work, we see her curiosity spike. Their first kiss naturally carries traces of Bella’s teachings on making out, which the engineer gently corrects. Their interactions seem to lead to something sincere, perhaps something that will break Marina out of her inadequate and lost state. However, their sex doesn’t come easily. Her body awkwardly confronted with the idea of spontaneous physicality seems to stagger. She’s struggling to cease talking, leaving no space for the heat of what’s indescribable and rendering their sex the exact opposite of

animalistic. Instead of bodies linked by the heat of an ancient calling, Marina and the engineer lay motionless, entangled in language. In a way, their time together echoes a scene taking place in a swimming pool’s changing room – Marina, sitting on a bench surrounded by a sea of women, seems curiously disconnected from the surrounding her physicality. Even though her body is the same as theirs, she doesn’t seem to be able to live through it the same way. However, with time their encounters take on a different shape, and, as viewers, we see Marina evolve (or, equivalently, grow up.)

The echoes of alienated girlhood and a quietly inadequate life can be heard in the aesthetic of the film as well. The lives of the characters unwrap amidst sharp lights of hospital waiting rooms, changing rooms, parking lots, diners, and LED-lit bedrooms, paired with the sea, and the hauntingly peaceful belts of mountains tingling the sky. We follow Marina in cars and on scooters, travelling along unfinished roads and white buildings.

The landscape exudes a quiet melancholy, and the architecture of this town finds its voice through Marina’s father. Spyros, close to death, and eventually gone, seems to possess the deepest understanding of the landscape of loneliness. A retired architect and widower here and there provides us with monologues about modern Greek society, and we’re never entirely sure whether his daughter understands them the same way.

“We built an industrial colony on top of sheep pens, and thought we were making a revolution” he says, gazing towards the tangle of buildings, ruins, scaffoldings and trees.

His voice is tinted by resignation with a cheerful note, and though he can’t accept the modern fate of Greece, he can’t go back to the raw force of nature, either: in one of their final conversations, he confesses to Marina that his wish to be cremated after death stems from the fear of being devoured by worms – the ultimate return to Earth he seems unable to embark on. Separated from his culture, heartbroken, and without connections to people his age, (he tells his daughter, “Sometimes I forget you’re not my buddy” in his endearingly sarcastic-yet-truthful way) he “denounces the

20th century.”

In the darkness of the hospital room Marina shares her final goodbye dance to Spyros’s favourite song “Be Bop Kid,” another foreign song delightfully detached from their life, almost as if from another planet.

“Are you ready to be an astronaut?” Asks Spyros,

“Yes.” Answers Marina.

The planet of grief, known to all animals. Spyros urges his daughter to cremate him and scatter his ashes around the sea, a way for him to return to nature on his own terms.

The sincerely heartbreaking scene of Marina scattering her father’s ashes into the sea ties the film’s ponderings tightly. With Bella by her side, she bravely sails to fulfil her father’s last wish. However bizarre and isolated their relationship is, at the end of the day they find support in each other. Every tennis game needs two players, after all. Marina holds out the urn, and the deep blue hue of the water swallows her father’s remains.

Funerals are a ritual unabandoned by highly developed societies. Something we have in common with wild animals, one of the souvenirs of ancient times we will carry around for eternity. Everyone knows death - the ultimate loneliness.

The women are wearing yellow rain jackets, standing out from the cool tones of the sky merging with the sea. The cold wind messes with their hair, and there’s something transcendental about this view. A daughter’s parting with her father, a friend by her side, the forces of nature shaking their boat and making the scene feel particularly physical. The finality of death strikes us unexpectedly, it ties knots in our stomachs.

Back on land, they walk through heaps of clay and trucks, their yellow jackets standing out from the red just as they did against the blue – their place is not in nature, nor in the industrial society. We’re left wondering; has the journey of grief and erotic explorations helped Marina develop a better understanding of herself? Can she build intimacy according to her own needs, in this unravelling new century? The two friends leave our sight, and the only answers we can get from the last moments are trucks driving around the construction site.

•

11 | FC3K

The Greek Queer Wave:

On Strella & The Weird Wave as a Queer Movement

BY ROBERT KARMI

Greek Weird Wave as a loosely connected movement remains defined in part by the sensibilities of Yorgos Lanthimos and his most frequent collaborators, as evidenced by the flag ship titles of the movement are Dogtooth (2009) and Attenberg (Athina Rachel Tsangari, 2010). However, scholars including Dimitris Papanikolaou argue the movement is far less cohesive in terms of formal style than what is commonly believed. Considering how often formalist analysis of cinema, especially marginalized cinema, abstains from generalized statements to avoid oversimplifying these films or, worse still, stereotyping them via a haphazardly loose connection. They argue the commonalities most prevalent in a connected cinema are more often thematic and ideological content rather than formalism. As such, one element which has consistently been noted about Greek Weird Wave is its classification as a “queer” movement, both classically and contemporarily.

As argued by Marios Psaras, the Greek Weird Wave frequently deconstructs, or “queers,” representations of narrative elements within Greek life and beyond, playing them up in such a way one could consider as something like dry camp.

Consider how often the movement demonstrates an interest in deconstructing familial relations through the lens of authoritarianism and surrealism, arguably the motifs which best exemplified initial interest in the movement. Further, there is also queerness in the subject matter, with non-heterosexual identities manifesting throughout these films, which further others them from similar international cinematic movements.

From these contexts, and the extended history of the movement wherein many pioneering figures of the movement started as early as in the nineties, we must consider the work of Panos H. Koutras. With his 1999 debut, The Attack of the Giant Moussaka, Koutras displayed a post-modernism in his work which would make him a central figure within the Greek Weird Wave. A gay director who would also double as an activist, Koutras is likewise described as a Greek Pedro Almodóvar, a campy cineaste with a deeply self-reflexive voice. His film made a decade later, playing in theaters at the same time as Lanthimos’ Dogtooth, Strella, further cements his legacy as one of Greek cinema’s prominent queer satirists.

Strella is a dense film to engage with, espe-

ESSAY

MINA ORFANOU IN STRELLA

cially its myriad narrative and themes. The film is partly a social-realist drama about a man, Yorgos (Yannis Kokiasmenos), fresh out of prison from a multi-decade stay and looking for his son in post-economic collapse Greece. He stays in a hotel where he meets the titular Strella (Mina Orfanu), a trans sex worker with a budding sexual and romantic relationship occurring between the two as he searches for his son, even returning to his old village in search of closure and answers. It is also an empathetic portrayal of queer Greek life which has created a community and found family amongst themselves. Most notoriously, Strella is primarily seen as work wherein Yorgos discovers Strella is his missing child and the ramifications therein. Said twist reshapes the film radically, further investigating the patriarch as the central figure in Greek society, as well as overtly drawing comparisons to national mythology.

As an aesthetic object, the film utilizes handheld camera 16 mm cinematography reminiscent of cinema verité instead of the deliberately composed and uncanny cinematography which Lanthimos and his collaborators are most famous for. Whereas those works intend their worlds to feel alien and unfamiliar, Strella provides a grounded world based on the material reality of Greece, then further constructs a microcosmos to explore, namely the queer scene in Athens. To said end, there is an

Strella provides a grounded world based on the material reality of Greece, then further constructs a microcosmos to explore, namely the queer scene in Athens.

interesting color contrast between Athens and the village where Yorgos and Strella spent their past lives, the village is detailed in naturalistic cool whereas Athens is brightly warm, even occasionally technicolor in certain segments. Of note is the diegetic use of rainbow lanterns Yorgos and Strella fix together in an incredibly tender and romantic moment, their naked bodies embracing as the colors transform their space into something otherworldly. Further, a grounded aesthetic helps make the melodrama seem more convincing than it otherwise might be.

The central performances from Kokiasmenos and Orfanou are incredible in a film filled with strong performances, bringing well-observed pathos and humanity to their performances they are asked to go to some intense places, especially as their dynamic continually shifts throughout the film. Both are phenomenal, but Orfanou is spellbinding as the titular character, carrying herself the best she can with her various traumas and desire for love with dignity and grace. She, and presumably many other performers of the movie, are trans performers playing trans characters, which adds an important layer of self-representation to the film, especially since Koutras, further solidifies his reputation as a Greek Almodóvar, frequently depicts transness in his work.

Strella, and the near totality of Koutras’ work, exists within the larger context of queerness in Greek cinema, frequently in an oppositional capacity. Before the emergence of contemporary queer Greek cinema, there was a period of intense cinematic homophobia wherein queer characters were largely demonized and made to suffer to legitimize a heteronormative status quo. Even progressive directors fell into the trap of representing their queer subjects as inhuman. That was the norm for a while until the breakout film incepting the contemporary queer Greek cinema Angelos (George Katakouzinos, 1982) was released.

Angelos displayed queer individuals as human beings like any other, yet also treated the central character’s crossdressing body at times like an object, both of desire and repulsion. The film is attempting to be sympathetic, yet because it exists within a paradoxical state of humanization and fetishizition, it cannot help but reinforce homophobic attitudes towards

13 | FC3K

the larger culture. The film continues to have a contentious legacy, with some wanting to praise it as a progressive object and counter-narrative for its era, others more concerned with how it reinforces those same attitudes it attempts to deconstruct. A similar discourse befell Strella, thus ensuring the more things change the more they stay the same.

Strella likewise depicts the life of a trans sex worker, from an empathic and humanistic place, frequently emphasizing their humanity and subjectivity as much as possible. It is, like other Greek Weird Wave films, a confrontation with the patriarch as an allegory for national identity and body politic, here represented by Yorgos, a man who was so absent a father Strella doesn’t consider their carnal relations incest (they also make the argument they have changed so much incrementally, Ship of Theseus style, furthering their point). The film challenges patriarchy further by creating trans matriarchs for Strella to seek guidance from, disrupting and challenging national values even more.

However, Strella likewise seeks out fatherly men as lovers due to her attraction to the patriarchal archetype, which further puts her in the line of fire with her father. The reunification of them in the film’s conclusion, in part a found family of other queer/ formerly incarcerated civilians, has been read as a return of the patriarch as a leader figure, thus reaffirming their importance and reaffirming national identity. However, as a story loosely adapting Sophocles’ “Oedipus Rex”, the film reaffirms its deconstructionist, anti-authoritarian identity. There is a moment in the film wherein one of Strella’s trans grand matriarchs mentions Sophocles’ name as one of the elder sisters who described the taboo of incest. Said moment of self-reflexivity acts as not only a lamp shading of the story being told but also explicitly makes us question how the film inverts and deconstructs the Oedipal myth.

Instead of a story of nobility, it is about the impoverished preyed upon by the wealthy. Instead of a man searching for a king’s killer, it is a man searching for his son. Instead of incest happening without either party knowing by accident, the incest is deliberate, and one party knows who the other is. The ending fails to conclude in tragedy with one dead and the

other divinely punished, but happy, reconciled, and allegedly together again. Here, Koutras creates a distinctly queer story, challenging our perceptions of familial bonds to their breaking point, ending on a note of human connection and forgiveness/reconciliation over tragedy, making for a thoroughly weird interpretation of a classic Greek play.

There is a utopian quality to the ending, wherein the harshness of the homo/transphobic world outside is kept at bay as a found family creates their own happiness. Here we see the final deconstruction play out, as Koutras makes a frequently harsh film end on such a tender note, wherein the cast has survived scathed but alive, transformed by the ordeal for the better. Too often stories about marginalization and queerness end in tragedy, with phobic violence winning out in the end, of life senselessly lost, and queer people made to feel expendable and destined for destruction. Here though, despite occasional emotional violence, we see a vision wherein the status quo challenged and changed for the better, where reconciliation and forgiveness are possible, and a created family emerges to represent a microcosm of a healthier, more inclusive society moving forward. It feels appropriate to point out Poor Things, Lanthimos’ latest English language work, concludes with a similar insight.

Strella is a singular work, strange even in the context of a national cinematic movement defined by peculiarity. It is a pivotal work in terms of representation of queerness and queering familiar spaces and ideologies and remains an incredibly progressive work fifteen years later. Further, it offers a vision of a world in which forgiveness and redemption are possible, wherein unconventional familial structures can emerge and thrive, and human connection is the great equalizer and radicalizer. Perhaps most importantly, it offers a much-needed other perspective in which to view contemporary Greek cinema. •

15 | FC3K

BY

ESSAY ART

HARRIS SINGER

BY GARRETT BRADSHAW

One of my favorite scenes in Apples is our nameless protagonist struggling to open a door. This is a film that wastes no time, using quick establishing shots and cuts, short sentences of dialogue, and the like to masterful effect. And yet, this difficulty with the door lasts just over one minute, which, compared to the sparsity of time afforded to everything else, seems like an eternity. Nevertheless, I was transfixed, watching intently as he awkwardly tried again and again to fit his arm through the bars on the small window fixed into the door. He takes his arm out, adjusts his sleeve, goes back in. He changes position, the handheld camera following his expressionless, yet determined face. Finally, the bolt clicks open and he walks in, closing the door to his old apartment behind him. Now, I can guess what you’re thinking: why? Why in a movie that has such understated, yet very real beauty and ache, is an unsteady, even uncomfortable, minute of a man trying to break into his own apartment among the highlights? It’s what’s behind this door. It’s what the movie has been getting at for the entire runtime. Namely, our human urge to stray away from facing our past, highlighting the fragility of our souls and the lengths we go to protect them. And, then, what happens when that resolve is broken, how we can heal by letting ourselves feel everything. How is this culmination found in just opening a door? Well, let’s peel back Christos Nikou’s Apples, shall we?

If you’ve never seen it, I’ll bring you up to speed: We open in Athens, where a strange pandemic has caused the unfortunate people who contract it to lose their memory, from what they were just doing, down to their name and personalities. We are told in the opening lines that there is a new program for those who have been afflicted and not recovered by their families (either they have none or they, too, have forgotten) to start a new life called New Identity. They are given assignments everyday that are designed to help bring some memories back or, at the very least, help create a base for the new self that the patients are forming. The patients are required to record these using

Polaroid cameras and create a scrapbook to show evidence that they are doing the work. These tasks range from riding a bike (try doing a wheelie) to having a one night stand at a bar to crashing a car into a tree. Seems… strange, right? But we are lured in by this comforting weirdness, this quiet, awkward, protagonist (who we’ll call Aris from here on out, after the actor who portrays him), and, while our guard is down, Nikou slips past our defenses and cuts us deeply. His tools to do so are seemingly minimalist and non-threatening. His lighting and colors are gray, a little foggy, until they’re not. Aris is going through motions, trudging through the oddity of the tasks he’s given, until, all of a sudden, he isn’t. The cinematography is utilitarian, right up to the point where it surprises you. These are akin to those moments of bliss that we have when we finally remember that word on the tip of our tongue, or the name of that guy you definitely remember meeting at that party a few weeks back.

Seemingly, the most surface level of these tools the film uses are the purposely subdued camerawork, lighting, and script. The camera is often handheld, a commonly used trick to get an audience more in touch with the human elements of films, rather than a perfectly mounted, unobtrusive camera. Certainly the most arresting aspect of the camera is the aspect ratio: 4:3 portrait is used to conjure a resemblance to Polaroid cameras, which evokes nostalgia and callbacks to the less advanced technology of the Athens that Apples takes place in (the instructions for the New Identity program are given on cassette tapes that are dropped off at the patient’s apartment, all the cars are older models, that sort of thing). Additionally, Nikou believes “it’s perfect if you want to capture tender emotions and move the audience. It gave us the chance to concentrate more on human beings than on the environment.” In opposition to the warmth and focus that the aspect provides are the cuts. As mentioned, this is not a film to waste your time. It usually lingers for exactly the amount of time it deems absolutely necessary and then it cuts away, moving on to the next shot or scene. The script pairs with

17 | FC3K

this clipping pace, not languishing on any intricate, lengthy monologues or even the characters voicing their frustrations, doubts, fears, or anything of the sort about the, frankly, harrowing situation in which they find themselves. All of it feels so sparse, especially when painted with the muted color palette that Nikou uses. Here we sit, in this gray, unsentimental world. And then, Aris is being driven in the rain, listening to music and the focus blurs until the traffic lights blend into this kaleidoscope of color and holds there longer than we’ve ever been allowed. Or he stops on the street to watch a display of black and white TVs, obscured by a fence, of two lovers enjoying an afternoon together. The pastels of the television sets standing starkly in defiance of the colorless displays. Or the entirety of “The Twist” plays as we watch Aris dance, unburdened from embarrassment, as the soft lights glow and reflect off of the dancers, haloing them as they move. Or (this is the last one I’ll mention, I promise) we watch Aris sit down to a meal for himself at a bar, the windows framing him in a transfixing tableau. Reds flank him, accompanied with orange glows of lights bouncing off of the wooden walls. A chandelier sits in frame above him, bathing the sleek bar top. He sees a couple begin to dance in the restaurant and the camera focuses on him, it dolly zooms in (what appears to be the only camera movement in the entire film), and holds and holds as he looks on. He stares as he did with the TVs. Something is there… Something just out of reach. Smash cut to feverish stirring in a rusty pot, the thought shattering to pieces around us as the spoon scrapes the pot. Nearly all of these fleeting

moments of beauty are abruptly cut from, like fingers being snapped in front of our face after letting our mind wander. And then we’re back into the mundanity that Apples employs. These static shots, this lighting, these dull colors are no accident. These plain, simple obfuscations to these memories trying to make themselves known create a numbness in us as an audience, just as they do Aris. While breathtaking, these moments of dazzling lights or bittersweet joy are too bright. They make our hearts race. To Aris, they are unsafe. The cold embrace of forgetfulness is a balm against those memories which a part of him is glad he no longer has.

Before the first lines about the New Identity program, heard over a radio, we are greeted with a rhythmic drum thudding over the opening credits. Well, at least it sounds like a drum. Throughout the beat, we see a house in disrepair. Trash litters the floor and counters. The entire place is a mess, except for the bed. It is perfectly, neatly made. As we cut to our first shot of Aris, it’s revealed that the noise we’ve been hearing is him, hitting his head against a column in his home repeatedly. Then, we cut abruptly (these have yet to become commonplace, so this first one is jarring) to a shot of him gazing at the bed. Not wistfully, not longingly. Not… anything. He simply stares at it. When he hears the news over the radio from his makeshift bed on the couch, he gets up and leaves his apartment, greeting his neighbor and his dog. He stops to buy flowers and then, after falling asleep on the bus, he forgets where he was going, who he was, and what he was doing. He is checked into the hospital, the latest victim of the amnesia pandemic. Among his hospital cafeteria dinner is an apple, which he enjoys as he speaks to another patient. Aris asks if the man isn’t going to eat his apple, to which the man responds “I don’t remember if I like them.” A bowl on Aris’s table in his new apartment always has apples in it after he moves in. Little quirks like these, his love of apples (and no other fruit), his tidiness, his penchant for cooking, are fragments of things he remembers about himself.

As he goes through the mundanity of creating his new life and completing his photography assignments, I sometimes forgot about that opening, but would occasionally think back and say to myself, “I wonder what that was about.” I honestly wasn’t sure what this movie

ARIS SERVETALIS IN APPLES

“The memory of happiness is perhaps also happiness.”

was doing until the treatment began to work. As Aris is walking through a park, his old neighbor’s dog comes up to him and Aris calls it by name. He remembered the dog’s name. Realizing this, he quickly leaves before the dog’s owner can see him. Before this, he is shopping for apples and the store owner asks where he lives. Aris tells the clerk his old address, pauses, and corrects himself. Little moments of remembrance are sprinkled through the film, but they don’t make Aris feel better… They didn’t make me feel better either, and when he goes again to buy a bagful of apples and the clerk remarks that they are “good for memory,” Aris looks sullen, takes a moment to think, and then removes each and every apple from his bag. He only eats oranges from then on. I ask myself about the opening again, but I phrase it differently. “What is he glad that he forgot?”

It all comes unraveled when he gets what is to be his final assignment: to find a person who is dying in the hospital and spend a few days taking care of them and, when they die, stay with their family. We are treated to a scene where Aris assists in feeding an old man soup, engaging in probably his longest conversation in the film. The old man is craving something sweet, more specifically the fresh baked pastries that his wife used to make. Aris asks if she is alive, and the old man tells him that she is, but she’s forgotten. Aris remarks, “Maybe it’s better this way. It will be easier for her. She will not have to forget about you.” The man nods and asks Aris if he is married. A pause. Aris answers with, “I was. She passed away.” No more running. Aris confides in this dying man what he has been trying not to remember. Whether he remembers it only just then or denying it for some time, it is finally out. The reason for the thud, thud, thud at the beginning.

After Aris makes a homemade pastry for the man, he returns to his room to find that he has died in the night. We see the funeral, Aris standing far from the crowd, crying. At home, he listens to his newest assignment but it’s of no use anymore. Either he decides that he

is finally cured or that the jig is up and he can no longer convince himself that he hasn’t been remembering for some time now. He throws away the photo album he has been so diligent in filling out with his completed assignments. He visits his wife’s grave and replaces the dead chrysanthemums, his goal at the start of the film. We linger on him gazing at the headstone for a long time. The abrupt, sharp cuts are no longer needed: we don’t need to run anymore. We remember now.

And so, we return to one of my favorite scenes. We return to that door. Before he can get in, Aris sits in wait outside for a neighbor to come out of the lobby. We sit with him, his anxiety is palpable. Aris dreads what’s behind these barriers, these hurdles. But he can’t run anymore. He remembers now.

The struggle with his apartment door is logical in the movie sense: he doesn’t have keys to the building or to his own home anymore. We could just skip to him getting into his apartment though, like a lesser movie might have done. But no, we are forced to watch this awkward, gangly effort as Aris wrestles to open a door he’s been running away from for a long time now. Finally, through his will power, he is granted access and we follow him. Shots linger on his late wife’s accessories - her sunglasses, hair clips, her pocketbook and watch. Aris sits, absorbing it all. Remembering. Finally, he gets up and tidies the apartment, but not before changing into his old shirt and opening the blinds in his living room. He lets the light back in.

Agnes Varde said “the memory of happiness is perhaps also happiness.” As he finishes cleaning, he notices the fruit bowl. The fruit has mostly gone bad, on account of the length of time he’s been away, but he finds a mostly unblemished apple near the bottom. He sits and cuts away the rot, taking care to pay attention to the hurt, but not indulge in it as he did before. He eats the apple, no longer afraid to remember, relishing in the happiness of his memories of his wife. •

19 | FC3K

In all of my research around the Greek Weird Wave one name kept popping up over and over again: Argyris Papadimitropoulos. Papadimitropoulos’ contributions to Greek cinema run deep. His film Wasted Youth fictionalizes a dark side of Greece’s history, a harrowing and real reimaging of the real life murder of teenager Alexandros Grigoropolous at the hands of police officers in Central Athens. This film was made at the very beginnings of the Weird Wave and served as a way for international audiences to understand the political turmoil the country was going through. Years later he made an equally harrowing slow burn character study, Suntan. This film expertly dives into the inner machinations of a man turning mad, surrounded by the most beautiful surroundings on an idyllic Greek island during tourist season. His most recent film is one called Monday, his first foray into English-language filmmaking and one where he is able to explore sex, romance, and the inevitability of the end to a party.

Papadimitropoulos joined me for a call from Athens where, from the beginning, he brought an unmatched energy and level of interest that I was so grateful for. Following is a series of questions I was able to ask him about his roots, his work, and his future.

ARGYRIS PAPADIMITROPOULOS VIA ARGYRIS.FILM

A Conversation with Argyris Papadimitropoulos: A Leading Voice in Greek Cinema

BY KEMARI BRYANT

ON HIS BEGINNINGS

Papadimitropoulos, like many Greek filmmakers, got his start in commercials. “Many of us from this generation cut our teeth doing all kinds of commercials. In a country where filmmaking doesn’t give you the means to survive, you do commercials which is also a good school. Because you’re telling tiny different stories [where you get to] play with your instruments.” He explains that a creative boom actually preceded the Crisis, which may not be widely believed. There was a door opening for imaginative filmmaking pre-Crisis, right there in the early aughts. “I want to say after Matchbox by [Yannis Economides] we were like ‘this guy did this tiny film’, which is amazing and super inspiring, with a tiny budget and a bunch of friends. So we started forming small groups. This is how Wasted Youth was made, this was how Kinetta by Yorgos Lanthimos was made, this is how Boy Eating the Bird’s Food was made, which I produced and [Ektoras Lygizos] beautifully directed. So many tiny budget films. There was something happening.”

Filmmakers taking power into their own hands and creating against all odds – there was definitely something happening, and it was something big. These films were making strides internationally even before critics put a name to the movement – Kinetta played in The Forum at Berlin International Film Festival – but titling this group of films may have certainly kicked the door open. Wasted Youth went on to open Rotterdam Film Festival and played Toronto International Film Festival in 2011, Boy Eating the Bird’s Food played Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in the Czech Republic in 2012. Before Wasted Youth Papadimitropoulos made a more commercial film, what he describes as a commission job –Bang Bang, a heist comedy. This was his first

film, one that brought him much commercial success and, perhaps, an open door to making more films. “When I was out in the market looking for this tiny little money for Wasted Youth, that cost $150,000, it was easy for me to find because I had a track record of a successful film before. That helped a lot.”

ON SUNTAN

One feature that stands out in each of Papadimitropoulos’ films is his reverence for his country. The cinematography of his films highlight the beauty of Greece – whether the grounded realism of the streets of Athens, or the illustrious island paradise of Suntan and Monday. The two latter films were shot on the island of Antiparos – an island he holds very near to his heart. “It’s where I got married, it’s where I party every year, it’s where my daughter loves to be every summer – it’s like my happy place, it’s the only way to describe it.” Suntan follows a middle-aged general practitioner (Makis Papadimitriou) who becomes obsessed with a young female patient. He describes how visits to the island sparked the idea for Suntan – he was thirty-eight at the time and he noticed that the holiday season, a time when the island was at its busiest due to out of town tourists, could be so frustrating for some people. “What if this guy, this one lonely doctor that we have on this island for all these crazy partygoers [...] what if this guy loses his shit because of all this.” He came up with the character of Kostis, a man who has missed out on a lot of life and who wants to “jump on the train while it’s far away from the station.”

He found Papadimitriou, who was known in Greece as a mostly comic actor, but jumped at the challenge of more dramatic material. Next he found Elli Tringou, who was at the time in her first year of acting school. Papadimitropoulos describes this discovery as “the greatest risk I’ve ever taken. I’m not happier for any-

CLOSE-UP 21 | FC3K

thing else in my career.” Suntan is in many ways a “devolution of man” story, but it is also a story about loneliness. The beginning portrays the island of Antiparos in its off-season, and shows how crippling and isolating that time is for our protagonist. His actions only serve as self-protection from an inevitable loneliness – once he gets a taste of community, he refuses to let it go. I inquired with Papadimitropoulos about this theme of loneliness that comes popping up in so many Greek films, “People in Greece are mainly extroverts. It’s a country where social skills really count.” Within this social system, it is especially easy to feel lonely, he explains. “Film can be [therapeutic], not only for the actors but also for the director [...] dealing with demons, dealing with anxiety. Loneliness was a bigger fear than death for me. I can safely say that.” While in Northern countries loneliness can be considered a bit more of the norm, in Greece being lonely can make you an outcast.

ON FILMING PARTY SCENES

If you watch a Papadimitropoulos film you’re going to see a party scene – it’s his trademark.

“I love shooting parties and I love throwing parties. Every summer I throw a party and it’s a party everyone is waiting for the whole year. Although I’m growing older it doesn’t stop being something that I love doing.” From Wasted Youth to Suntan to Monday, Papadimitropoulos gets into the heart of a party and attacks the audience with multicolored lights, blaring music (usually an on point needledrop), and the emotional potential that a party can bring – the beginnings and endings of things, the emotional freedom, the jealousy, and so much more.

His annual party is oftentime the inspiration for his scripts, a prime example being Monday. In the film Mickey (Sebastian Stan) and Chloe (Denise Gough) meet at a party in Athens. The next morning they wake up on a beach after having sex, completely naked surrounded by families –and police, who promptly arrest them. This was based off of a story he heard that came out of his party. “I love the party itself, but I also love the following days where I’m calling my friends and everyone has a different crazy story to tell.” These crazy stories might even end up in a movie.

What I found even more interesting was the way in which Papadimitropoulos went about shooting these party scenes. As a partier himself,

he always goes for reality. “I’m trying to keep the parties in my film really authentic. What we’re doing is we’re throwing a party and we’re filming it.” Simple, right? He explains that he wants to capture the “planned but not planned”, inviting a bunch of friends and actually throwing a party complete with lights and music. He connects to a microphone and tells the crowd things to do as they party, and sets up two to three cameras to cover everything. After he gets all of the party shots he recreates moments of the parties with a smaller group of extras and no music to capture intimate moments and the actors’ dialogue. “The general idea is that we’re keeping the parties real.” When it comes to parties, it seems that on a Papadimitropoulos set there is a thin line between fiction and reality – on Monday they filmed a block party that had over 1200 dancing on a blocked off street. “It was almost impossible to stop this party.”

ON VISUAL STORYTELLING

One of Papadimitropoulos’ strengths lie in his visual storytelling – early scenes in Suntan portray Kostis alone during off-season on Antiparos: the island is dark and rainy, locals fill the bars, and Kostis is always isolated in the frame. However, when the tourist season comes Kostis’ world is filled with light – along with a group of tourists who he befriends. This trust in visual storytelling as opposed to endless dialogue is a recurring part of Papadimitropoulos’ filmography, and speaks to a trust between himself and long term filmmaking partner and DP, Christos Karamanis. “Christos is like a brother to me. We have amazing visual communication.” Christos is quiet, Argyris is loud. Argyris loves city life and partying, Christos loves nature and bike rides – but they complete each other. They’ve developed an almost telepathic communication – he gives the example that if the camera team asks what lens they want, they can simply shoot each other a smile and know what the other is thinking. A distinct visual style is a defining factor of Papadimitropoulos’ films – oftentimes using natural light and shooting the beauty of Greece with such care and clear appreciation, with an added freedom to switch visual style with each project. In Suntan a scene where

Kostis and Anna run off to a small beach to have sex is shot with the manipulation of natural light, the beauty of the landscape juxtaposed to the beauty of their bodies –which is also in harsh contrast with the reality of the situation. Then there is Wasted Youth, which oftentimes feels shot like a documentary. Beauty hides within reality, and a shot like three teen boys riding together on a motorbike can hold a world of emotion in its simplicity.

ON POLITICAL FILMMAKING

Wasted Youth is Papadimitropoulos’s example of filmmaking used as a political device. “Making films, even placing the camera, is a political action because it shows where you stand, which point you look at things from. Making films in a country where making films is not that easy is also a political action.” With the creation of Wasted Youth he didn’t want to overanalyze, he wanted to show a “quick reflection on a huge social change that was happening. It all started with the murder of an innocent boy in cold blood by a cop – the mark of a different time for Greece. It was the beginning of the economic crisis, and the end of a time of prosperity that had come before.”

“Although I didn’t know [what was] really happening and where this was going to take us I wanted to document, somehow, this era. Because I was feeling that something was about to change. I’m not a documentarian, I’m a fictional filmmaker, so getting inspired from this tragic event I tried to make a portrait of a city being boiling hot, being boiling hot because all these crazy things are happening at the same time.”

A city being boiling hot on the brink of an explosion – I made a comparison to Do The Right Thing, which he agreed with, “What can go wrong on this beautiful day? Fuck.” He also drew a comparison to Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, a fictional retelling of a school shooting loosely based around the 1999 Columbine high school massacre. “You get inspired by an event but you’re not recreating the event itself. Let’s see a version of what happened there but a totally fictional one. It’s not the story of Alexandros [the teen who was murdered], it’s the story of Haris.”

Haris, as played by Haris Markou, the

protagonist of this important film who was just a teen skateboarding in the street before Papadimitropoulos and his team spotted him. They approached him about being in the film and his questions were simple: does it involve skateboarding? Is it easy? Do I get paid? He was in. Papadimitropoulos began following Haris and his friends to see how they lived their daily life, and asked them to begin improvising. The narrative arrived by having his “eyes and ears totally open”. They only knew the ending of the film, which was a mirror of the true tragic story, and they had 20 scheduled days and seven crew members to find the story that came before it.

He believes that the story is still fresh, but it served its purpose. His curiosity lies in seeing how the film lands in twenty or thirty years, with an audience who wasn’t born looking back at a film from a completely different time. I commended the film’s importance in film history, a snapshot of time rife with change – completely informative to an American audience attempting to learn more about this period in Greek history. “For me it was an experiment. I got a bunch of friends and seven pages of a script. I mean, we didn’t have a script, we had some notes.”

ON WHAT’S COMING NEXT

Papadimitropoulos remained tight-lipped, but he did give a preview of what is to come: it’s going to be English language and it’s going to be a comedy. “I really need to make a comedy.” he drove the point home, a project that would be his first tapping into this genre since his debut Bang Bang – though his love for comedy certainly shines through in his other projects. He misses doing projects where people laugh when he says cut.

ON WHAT HAS INSPIRED HIM RECENTLY

Finally, I asked Papadimitropoulos if he had watched anything recently that inspired him. He had watched Poor Things the day before.

“I [knew] Yorgos before he started even making films, and I know how talented he is, but this time I was like ‘what the fuck?’ – and it was so funny, too.”

23 | FC3K

THE LOBSTER POSTER DESIGN BY VASILIS MARMATAKIS, 2015.

25 | FC3K

Context-Dependent Love:

Love in the Films of Yorgos Lanthimos

BY WILLIAM REYNOLDS

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. But is it really? Our unwavering belief that love is pure, able to thrive no matter the circumstances and conquer all obstacles is a heartwarming sentiment. However the focus on the supposed innate beauty of love has enshrouded it as a mythical untouched emotion. Contrary to this thought love is far more grounded than we believe and, impacted by the conventions of the world we live in. As an auteur willing to delve into our societal conventions, Lanthimos’ films captivate audiences. Conventions which we subconsciously know exist but don’t dare to prod and poke in the fear we will uncover some heinous truth, that will shatter the delicately constructed illusions we sell ourselves. We repeat to ourselves that there are things that exist outside the vacuum of the capitalist machine, emotions that pierce the societal veil. However, Lanthimos holds the mirror up directly to us and not only invites us to reflect upon these conventions but guides us through his hyper-real and uncanny worlds in order to critically deconstruct concepts we accept as unadulterated truths.

Cinema has always been in dialogue, either explicitly or implicitly, with the world we live in. Lanthimos epitomises this philosophy with what appears to be fantastical films but are actually rich in current subtext. He is always reflecting and splicing open our own world by isolating and picking apart aspects of the status quo. Lanthimos is no stranger to crises. Greece was one of the countries that felt the worst effects of the worldwide economic recession in 2009. The country was plunged into historical levels of debt which was evidenced by historically high levels of unemployment, inequality and homelessness. One mechanism the government utilised in order to ameliorate the debt problem was increasing taxes. However, in a country where people were poorly supported by

a lack of welfare infrastructure this only resulted in antagonism. This hostile atmosphere between government and people, alongside the poor quality of life resulted in societal issues from increases in tax evasion to fraud to hate crimes against refugees. Lanthimos was a firsthand witness to this collapse in social conventions which no doubt informs his filmmaking process and his uncanny ability to deftly weave and dismantle preconceived notions we have. Ultimately, it is when our environment is in flux that the illusions and societal rules we create begin to crack and reveal themselves. The interactions between different principles laid bare. Lanthimos challenges a variety of societal conventions but it is particularly when he dares to confront our most accepted truths that he brings into question our lived realities. His desire to disassemble the complexities of love is fascinating; it forces us to question the ubiquitous notion of its being pure. This has in turn produced some of his best and most beloved work.

All of Lanthimos’ films play with the idea of love but there’s none more synonymous with the idea of love being twisted and bent into an unrecognisable shape than The Favourite (2018). The Favourite is a sumptuous tale of the struggle for power between three women, Queen Anne (Olivia Coleman), Abigail (Emma Stone) and Sarah Churchill (Rachel Weisz). Abigail, Sarah’s impoverished cousin, arrives at the beginning of the story and begins to rival Sarah for the affections of the Queen. The Queen who is largely disinterested in the political affairs she must contend with is inclined to just follow the guidance of her lover Sarah. It’s a constant question whether the Queen and Sarah are in love or whether their romance is a symptom of Sarah manipulating the Queen for power. Whilst the latter appears to be the initial reading of their romance it becomes more and more apparent that the Queen is aware of

ESSAY