Team 5 Meeting place: Rebeca Esnaola 6 To lift the gaze: Manuel Asín 8 Image: Misha Bies Golas 10 Official Selection 13 Retrospectives 35 Other Times Are Coming | Es nahen andere Zeiten The films of Peter Nestler 36 Punto de Vista Collection. Se acercan otros tiempos. El cine de Peter Nestler 54 Far from the trees 56 Focus 71 Three adventures by Pascale Bodet 72 Freedom, is it possible? The films of Ana Poliak 76 Tales from the land. A Grasscutter’s Tale, a film by Fukuda Katsuhiko (1985) 84 Lan 93 Paisaia 94 Termitas 96 Professional activities 99 Echoes and Ecologies. A poetic and political approach to the Guillermo Zúñiga archive 100 Súper 8 contra el grano 102 Contactos 105 Kosmogonía. Film performance para un planetario 106 Object Lessons: Rossellini, Godard-Miéville. Godard’s Sensitive Thought. Talk by Paulino Viota 108 Altzuza. Performance by IbonRG in Museo Oteiza 110 Closing session 112 X Films 115 Festival Mediation Program 123 What do pictures sound like? 124 Creatures of nature: plants, humans and other animals 126 Cinema on the move. The currency of the Lumière brothers 130 Jóvenes Programadores. Moving Cinema X Punto de Vista 132 Acknowledgements and index 140

Punto de Vista - International Documentary Film Festival of Navarra is promoted by Department of Culture and Sport, Government of Navarra, and organized by NICDO S.L. Plaza de la Constitución, s/n. 31002 Pamplona (Navarra)

Tel. 948 06 60 66

info@puntodevistafestival.com www.puntodevistafestival.com

Catalogue for the International Documentary Film Festival of Navarra, No 17

Published by NICDO S.L.

Printed by Imprenta Zubillaga

ISSN - 2171/2166 Addendum 17

Legal deposit

NA 266-2010

Promoted by

Organized by

With the aid of

With the support of

Member of Contributors

4

Management Committee

Ignacio Apezteguia Morentin, Lorenzo García Echegoyen, Ana Herrera Isasi (Department of Culture, Government of Navarra), Paula Noya (NICDO), Pablo Berástegui and Itziar García

Team

Artistic Director

Manuel Asín

Executive Director

Teresa Morales de Álava

Programming Committee

Manuel Asín

Pablo García Canga

Lur Olaizola

Lucía Salas

Miguel Zozaya

Production Coordinator

María Rodríguez Abad

Production Department

Garazi Erburu Irigoyen

Mikel González Parra

Programming Coordinator

Cristian Ruiz Carrera

Communication Coordinator

Pablo Sotés Mariñelarena

Communication Department

Andrés Bueno Chocarro

Acknowledgements

Editorial Coordinator

Esther Aizpuru

Guest and Accreditations Coordinator

Sara Larripa Acedo

Guest and Accreditations Department

Josefina Maggiotto Iribarne

Vanessa Chacín

Technical Manager

Iker Espúñez

Technical Department

Pablo Cayuelo

Catalina Altuna

Film Department - NICDO Silvia García Domínguez

Image, photography

Rodrigo Pérez Rodríguez - Txisti

Recording, editing video

Miguel Eraso

Image of Punto de Vista 2023

Misha Bies Golas

Design, catalogue and other materials

Franziska

Translation

Hitzurun

Text translation

Kosuke Nakamori (Japanese)

Mattea Cussel (English)

Technical projection services

Técnica Cinematográfica Loza Subtitula’m

Movilcine S.L

Sound

Telesonic S.L.

Film subtitles

Subtitula’m

Interpreters

STI World S.L.

NICDO Team, Adrián García Prado, Alfonso Crespo, Antonio Trullén, Arrate Velasco, Asier Armental, Carlos Muguiro, Cecilia Barrionuevo, Cyril Neyrat, David Arratibel, Efrén Cuevas, Elisa Celda, Fabienne Aguado, Fabienne Moris, Fran Gayo, Frank Beauvais, Garbiñe Ortega, Hama Haruka, Hatano Yukie, Isabella Lenzi, Jaime Pena, Javier Rebollo, Jean-Pierre Rehm, Josetxo Cerdán, Juan Pablo Huércanos, Juan Zapater, Juliette Achard, Madoka Kubota, Manuel Peláez, Mariano Mayer, Marina Vinyes, Matthieu Grimault, Mikel Artxanko, Óscar Fernández Orengo, Óscar Gascón, Óscar Vincentelli, Oskar Alegria, Pablo La Parra, Pablo Useros, Rafael Llano, Sergio Oksman, Tsveta Dobreva, Vanesa Fernández Guerra, Vanesa García Cazorla and Víctor Iriarte

5

Meeting place

Our community is kicking off a new edition of Punto de Vista, the International Documentary Film Festival of Navarra. A meeting place because it is intended to be a place for different people to come together with the aim of excelling and innovating. And a chance for the public to come along and discover audiovisual experiences to enrich us, off the traditional screening circuits. A landmark at international level, a place for documentary film from all over the world to come together.

This time, one of the central programmes will be the retrospective Other Times Are Coming. Es nahen andere Zeiten, the first national event of its kind on the work of German film-maker Peter Nestler, complemented with films made by his wife, Zsóka. This is one of the most important bodies of documentary work in contemporary Europe, though it is still little known in Spain, for which reason this innovative series will be visiting Barcelona, Madrid, Coruña and Valencia.

Nestler’s work has been widely shown internationally, so Punto de Vista is offering a new, significant selection of his film work, based on archive finds and restorations in recent years, as well as on some recent productions.

The festival considers it necessary to pay homage to the career of an essential director who remains active despite his age, filming and taking part in public events. We are privileged to be able to bring the work of a major figure on the European documentary film scene to Navarra, where his presence will also allow his experience to be passed on to younger generations.

The Official Selection, Focus, Lan and X Films will be other areas for audiences and film-makers to come together in the field of documentaries and non-fiction in general. Spaces for dialogue between past and future, where the most diverse traditions can come together with the boldest, most innovative offerings; spaces for excellence. Punto de Vista sets out to be a festival that fosters knowledge of reality and independent expression, stimulating an approach to films as an independent, socially necessary means of expression.

The festival also works actively to foster critical audiences, aware of audiovisual languages and of the diverse realities around the world. The Mediation Program is a commitment to younger people, introducing them to the world of documentary through attractive activities that speak their own language, in a relaxed, friendly way. With workshops and screenings, the second edition of Jóvenes Programadores Moving Cinema x Punto de Vista and the Youth Jury represents a clear commitment to make documentary film accessible, for it to be enjoyed by the whole of Navarrese society.

6

In presenting this year’s edition, we need to thank the many people and bodies linked to the festival year after year. First of all, the team and especially Manuel Asín, as artistic director for the second year, for making his mark on a proven, experienced Punto de Vista. To the companies and institutions who work with us, because they provide the support we need to put on a great festival with a wide impact. And of course, the audience: our most loyal audience, those attracted to come to this wonderful event for the first time and those who have yet to come. Enjoy it!

Bermejo

7

Rebeca Esnaola

Minister of Culture and Sport in the Government of Navarra

To lift the gaze

The day-to-day activity of the Festival allows us to enter into contact with what is being produced in the feverish field of what we still call “documentary filmmaking”. We have discussed a large number of films over several months and ended up choosing a few that invariably resonate with the other series and activities in the programme. We opened up the angle as much as possible to then cut back -always extendable, always improvableof what we on the programming committee consider urgent and necessary. This cutting back means —above all— a celebration of the complex integration that some films manage to achieve. A commitment to reality, understood from as wide-ranging a perspective as possible, and also to the art that makes up the films.

There is no contradiction between both forms of commitment. Nevertheless, misunderstandings may arise if we underestimate the integrated nature of both dimensions. Filmmaking has its own dynamics, which never stop being firmly interconnected with those of the world. The ways in which filmmaking transforms reality, and is configured by it at the same time, do not need to seem different to us if we are able to see them from the right perspective, from the way in which the sociability of a group of foxes, a dialogue or a human conflict, the voice of an old dike sluice, a meteor shower or a lava flow are configured by reality and can transform it.

In 1923, Jean Epstein filmed some of these lava streams in a serious but amazed way during one of the last eruptions of Mount Etna. That film, La Montagne infidèle —lost until a copy was recently found in Filmoteca de Catalunya— will be screened in the Closing Ceremony of the Festival. Following his experience under the volcano, Epstein carried out some soul-searching that will hopefully have an effect on those who attend all the sessions we are proposing this year. “The cinema brings all the kingdoms of Nature into one, the one with the greatest amount of life [...]. Before me, a movie theatre with three hundred people groaned in unison when seeing a grain of wheat sprouting on the screen. [...] To grow and unite, stones have pleasant and ordinary gestures, like rediscovering cherished memories [...]. There is no still life on screen”.

The two retrospectives this year also respond to this desire for integration. The first wide-ranging series of the films of Peter Nestler in Spain aspires to be a tribute to the work of one of the filmmakers we admire the most. A work produced with humbleness and perseverance over six decades, ever more respected for the coherence with which it defends the memory, transformation and preservation of what should be remembered, transformed and preserved. Programmed by Ricardo Matos Cabo —responsible for previous international presentations of the work of the filmmaker—, together with our colleague Lucía Salas, the retrospective is complemented by a publication that wants to be an introduction and a celebration of the constant features of Nestler’s filmmaking: the camera and the microphone as tools to open up to the world with honesty and justice; a conception of cinematographic work that transcends the traps of individualism; the continued exercise of what Bertolt Brecht called “the art of the realists”, that is, “unearthing the truth under the rubble of evidence, visibly linking the singular to the general, fixing the particular in the great process”.

8

The second retrospective this year, once again brilliantly programmed by Miriam Martín, looks into some of the natural process of which we are part (the stubbornly harmful part, we should add). In the last edition, human action on rivers inspired an extraordinary small history of the documentary in Miriam, and now it is a case of making us see the painful drift of the human race that has become a producer as well as a consumer, and the way in which acquiring essential goods is creating a threat to all living species, ours included. It is about starting from some of these products, with their human names —“fish”, “bread”, “meat”— in order to go back upstream in the construction and destruction that leads to them, through a journey back to the seed. Miriam’s dazzling texts speak of centripetal and centrifugal forces that mould the world and films. Indeed, each piece in her programmes —and the interplay among them— are put together with great care so that we can see and reflect on processes that we should urgently stop considering as closed. They are impregnated with change and can, in turn, be changed.

Let us return to Etna. In the summers of 1986 and 1988, more than sixty years after the shooting of Epstein’s film, Danièle Huillet and the recently deceased Jean-Marie Straub —dear colleagues and friends of Peter Nestler— climbed the slopes of the volcano again to shoot scenes of Der Tod des Empedokles, the tragedy that Friedrich Hölderlin had set in that same location in 1779, i.e. on the eve of a revolution that would later be called ‘industrial’. Hölderlin, who incarnated a different kind of utopia better than anyone for Straub, in which “the greenness of the earth will once again shine for you”, would surely have been moved to see his work staged in the open air, next to the volcano. On the edge of the real crater Danièle and Jean-Marie, Hölderlin, Ana Useros and Miriam Martín —in the translation below— make Empedocles utter words that are the best preface to the six days of screenings and dialogues that we are about to share:

You have thirsted after the unusual for a long time, and, like a sick body, the spirit of Agrigento desires to leave the old furrow. So, take a chance! What you have inherited, what you have acquired, what your parents’ mouths have told and taught you. laws and customs, names of ancient gods, boldly forget them and lift, like new-born babies, your eyes to divine Nature.

Manuel Asín Artistic Director, Punto de Vista

9

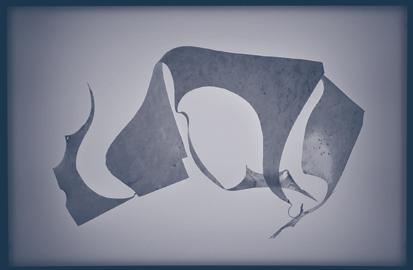

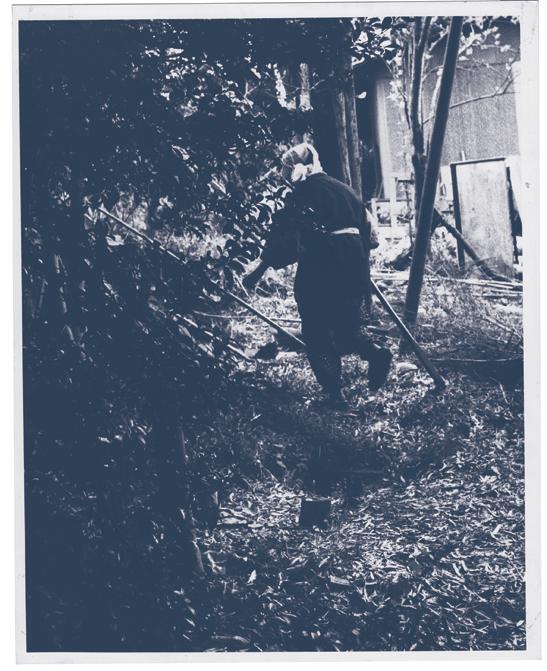

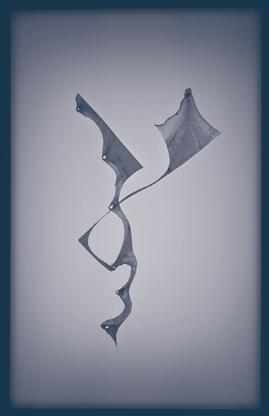

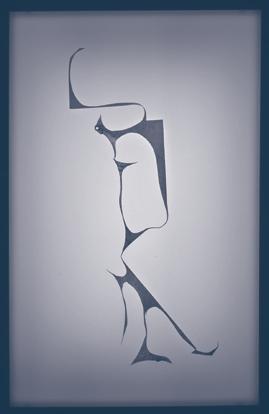

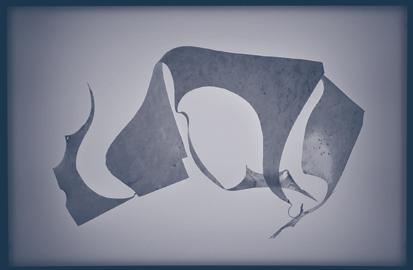

The photographs that make up the image of this, the seventeenth edition of Punto de Vista, are part of a set of around a hundred shots taken, like a catalogue, of offcuts collected among the waste from a leather goods workshop.

Using the parchments left over from making the menus for a traditional Castilian tavern, apart from the straight lines cut by the leather worker, the artist also makes more sinuous, curved cuts, to which he also adds a series of stress points using the holes already made by the tanners when stretching the hides in their workshop.

Viewed one by one over a light box, these fragments were photographed with the aim of emulating the mechanics of some types of shadow theatre from south-east Asia and Turkey. The tonal variations in them are the result of free interpretation by the camera of the movements of the fluorescent lights.

Nor is it naive —perhaps in the way it treats its materials, in its shapes, atmospheres and the decision to capture them in photographs— it is a nod to certain authors like Julio González, Ángel Ferrant, Eugenio Granell or the artists of the Vallecas school.

Consequently, many of the shapes resulting from this multi-person process were used to create a series of movable sculptures and installations whose aim is to generate different ways of playing with space by projecting their shadows.

Based upon several experimental works completed in his studio and at Monasterio de la Inmaculada Concepción de Loeches, the artist Misha Bies Golas has designed a work specifically for one of the spaces at the Museo Oteiza. An exhibit in which parchments combine with light, sound and other construction materials to form a dialogue between the architecture and the the permanent elements of the space within the home studio of Oteiza.

The Punto de Vista 2023 image designed by Misha Bies Golas can be appreciated throughout the entire catalogue.

Misha Bies Golas is a visual artist trained in the fields of photography and graphic design. His work cuts across different disciplines, his most recent pieces concentrating on the accumulations of scrap materials, books and objects of different kinds. He currently forms part of the NEG (Nova Escultura Galega) group, together with Alejandra Pombo Su, Diego Vites and Jorge Varela. He has had solo exhibitions in Galicia (Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea, Fundación Luis Seoane), Madrid (SALÓN, Nadie Nunca Nada No), Palma de Mallorca (Louis 21), Valencia (Luis Adelantado), Lisbon (Appleton Square) and São Paulo (Ateliê Fidalga), as well as featuring in many collective exhibitions.

10

Image

Official Selection

This year’s Official Selection includes seven short films and eleven international feature films competing for the festival’s five awards: the Punto de Vista Grand Prize for Best Film, the Jean Vigo Award for Best Director, the Best Short Film Award, the Audience Special Award and the Youth Award. Six world premieres, two international premieres, one European premiere and eight Spanish premieres.

Official Selection 14

Official Selection Jury

Ángel Santos Touza. Galician film-maker who has been working since 2002. He holds a degree in the History of Art and a diploma in Film Direction from the Centre d’Estudis Cinematogràfics de Catalunya. He has written about film (Miradas de Cine, Blogs & Docs, Shangri-la) and co-founded Novos Cinemas, Pontevedra International Film Festival, of which he was artistic director for the first five years (2015-2019). As a teacher he has been involved in the classroom education scheme Cinema en Curs. He has given seminars for universities, arts centres and festivals; he has been a consultant in project development forums (Malaga festival, MECAS in Las Palmas and FIDBA in Buenos Aires), and has been a jury member at international festivals including FICX in Gijón, Spain, and FICUNAM in Mexico.

Hama Haruka. She has worked for the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival (YIDFF) since 2001, and has been director of its Tokyo office since 2015. She coordinated Nexus of Borders: Ryukyu Reflections (YIDFF 2003), Vista de Cuba (YIDFF 2011) and the Latinoamérica programmes (YIDFF 2015). She also works for Cinematrix, a Tokyo-based film distributor, which made Takamine Go’s feature-length film Hengyoro (Queer Fish Lane), produced by Hama. She is involved in coordinating national and international screenings, including curating the film programme at the 2016 Aichi Trienniale.

Marcos Uzal. Since 2020 he has edited the French magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Before this he had sat on the editorial committees of Trafic and Vertigo magazines, and written as a critic for the newspaper Libération. He has also programmed film screenings at the Musée d’Orsay, and lectured at numerous film institutions. He has also edited the Côtés films collection, published by Yellow Now. He has written several books for the same publisher: Vaudou de Jacques Tourneur (2006), Guy Gilles. Un cinéaste au fil de temps (2014) and Jerzy Skolimowski. Signes particuliers (2013). He is the author of the short films Le Taxidermiste (1993), La Ville des chiens (1994) and Ici-Bas (1998). Since 2010 he has sat on the jury for the Prix Jean Vigo, and since 2022 for the Prix André Bazin.

15

Al borde del agua

Maria Elorza & Iñigo Salaberria

Spain, 2023, 20 min, super-8 to DCP, colour, Spanish World Premiere

Selected filmography

Maria Elorza: A los libros y a las mujeres canto (2022), Quebrantos (2020, with Koldo Almandoz), Ancora lucciole (2018), Gure hormek (2016, with Las chicas de Pasaik) Iñigo Salaberria: Lo ibiltariak (2017), Luz a la deriva (2015), Disdirak (1992), Birta Mirkur (1987)

Al borde del agua [Beside the Water] is the work of two people: Iñigo Salaberria and Maria Elorza. A film-maker born in 1988 in Donostia-San Sebastián, she was a member of Las chicas de Pasaik, and in 2022 presented her first feature: A los libros y a las mujeres canto. He, born in Rentería in 1962 and recently deceased, was a key figure in the Arteleku centre and one of the most important video artists of the 80s and 90s. The film begins with a phrase: “Between 1984 and 1988, Iñigo Salaberria filmed several locations with a small Super 8 camera. It was test material. The reels were never edited and remained in the shadows for thirty-three years”. After this, the images filmed by Salaberria appear. Reflections in the water that turn figures into shapes, colours and textures; whaling ships; a lake where smoke and steam mix; buildings that turn into vertical lines; more reflections in water, accompanied by the sound of the water itself, and sometimes by classical music. Above all they are drafts for Salaberria’s pieces Quai de Javel (1984) and Birta Myrkur (1987). Attractive images framed in such a way as to turn them almost into paintings, that bring us closer to the video artist’s view. To what his relationship with reality through the camera was actually like. We can also hear his voice, which in several conversations with Elorza tells us more about his reflection on what is involved in filming images: “Wandering, walking, looking. Unhurriedly, with time. Walking, looking, wasting time. I’ve never filmed in a hurry. That slowness, I don’t know why, appealed to me. Well, I do know why. Because what I wanted to document is what’s inside”.

Lur Olaizola

Official Selection 16

APOCALIPSIS 20 21 22

Julius Richard

Spain, 2022, 65 min, miniDV to DCP, colour, silent

World Premiere

Script and editing

Julius Richard

Tamayo / Selected filmography ABCLSD (2020), Trabajo y amor. Diarios I-XII (20202008), Aluzinaciones (2018-2013), Me gusta bailar pero no en el aire (2016-2009), colectivo el hijo (2016-2011), Tríptico (o Pentáptico) del Amor Supremo (2013-2012)

This film is a year of life and lasts just over an hour. The film-maker, by creating layers of images and layers of sound, condenses time and experience. He makes a film that is like his own tattooed body: superimposed texts and images, past decisions that remain indelible on the present, changing body. We could say the director, in filming and editing, crystallises a year. Or perhaps creates an alter out of what is filmed. On this altar there are candles and a thousand other flames: the sun, the lava of a volcano, a crematorium, bonfires and more. Moreover, it is all seen as if, in some way, it were fire: moving, changing, hypnotic, born out of what it consumes. The film-maker creates an altar and on it intones a prayer or an incantation for the family, for loved ones. Yes, perhaps it’s this, an incantation to escape from a terrible year, from an ongoing apocalypse. Or perhaps not. It’s difficult, and probably unnecessary, to fit a film that escapes and reinvents itself as it goes along into a box or a feeling. A film that in reality is made to be seen but also to be listened to an, even more, to be seen while listening to the music, for the image to be sound and the sound image, and so that in the end both sound and image become touch.

Pablo García Canga

Pablo García Canga

17

Bide bazterrean hi eta ni kantari

Peru Galbete

Spain, 2023, 9 min, HD-VHSsuper-8 to DCP, colour, Basque World Premiere

Script and editing

Peru Galbete / Selected filmography

Ura sartu zen barrura (2019), Josuneren bidaia (2015)

This is a film in which we hear and read poems by Joxean Artze. This film is also a poem itself. A short poem made up of poems, of sounds, of images of the past and images of the present. A poem made from the magic of film called editing, that makes it possible to put together things that in reality can’t go together. A film that puts together, in a flash, two times on the same terrace, a film that superimposes the sound of the sea and the image of a metro tunnel. A film that puts together two birds that have lived far apart for decades, two birds that are unique but at the same time are the same bird. Perhaps this is the magic of editing: the magic of “at the same time”. As in dreams, there where time and space become confused. This film could be a dream dreamed by those children we see in pictures sleeping and suddenly become adults but still sleeping. One of those dreams that on waking you don’t know whether you really remember it or whether you’re reinventing it when you try to explain it. One of those dreams that are totally meaningful but at the same time slippery. Once of those dreams whose memory you want to cling to even though that memory is uncertain and changing, because you know it’s telling you something, something important.

Pablo

García Canga

Official Selection 18

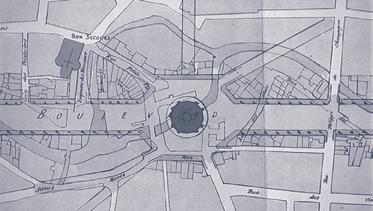

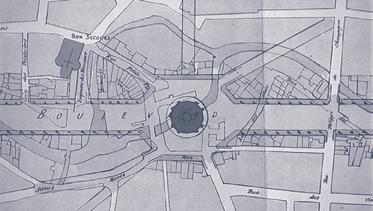

Boulevards de la Senne

Juliette Achard & Ian Menoyot

Belgium, 2023, 11 min, DV PAL to DCP, colour, French World Premiere

Cinematography Ryszard Karcz / Production Juliette Achard and Ian Menoyot / Selected filmography Remparts (2023), Karl Marx à Bruxelles (2022), Le souci de nous (2022), Main pour main (2019), Autant en emporte ly vens (2018), Aux envolés (2017), Saule Marceau (Juliette Achard, 2017)

Boulevards de la Senne starts by naming in writing the elements that make up the film. In white letters on a black background: “The voices of Saidou Ly, Joan-Noël Boissé, Juliette Achard, Ian Menoyot and Ryszard Karcz. Also, a poem by Saidou Ly that is part of Des intégrations, the book La Senne by Gustave Abeels (1983), the book La Belgique by Camille Lemonnier (1888), photographs from the Brussels Archive (1860-1866) and a song: Trois Chant Sacrés pour soprano et trio à cordes (1951)”. By combining all these things, the film-makers create an essay film that talks about Brussels and the development work that made a permanent mark on the city’s experience: covering over the river Senne in the mid-19th century. The film-makers use different devices to bring the Senne back, in a way, to flow through the Belgian capital once more. The film begins with a map, that gives way to images shot in the streets today. Views of different places, the past of which is explained by different voiceovers that recount the history of the place: the pollution of the river, the dirty water, the work to cover it over and the compulsory purchases involved in this. In the final part of the film, the past moves from the voiceover to the pictures: various archive photographs show us what Brussels was like before the Senne was covered over. A city where the streets were flooded with water. Lur Olaizola

19

Cette maison

Miryam Charles

Canada, 2022, 75 min, 16 mm to DCP, colour, French-English

Cinematography

Isabelle Stachtchenko and Miryam Charles / Sound Gordon Neil Allen and Olivier Calvert / Editing Xi Feng / Music

Romain Camiolo / Production Embuscade

Films-Félix DufourLaperrière / Selected filmography

Chanson pour le nouveau monde (2021), Deuxième génération (2019), Une forteresse (2018), Trois Atlas (2018), Vers les colonies (2016), Vole, vole tristesse (2015) / Berlinale Forum, IndieLisboa, Hot Docs

In 2008 Tessa, aged 14, was found hanged in her bedroom. The autopsy showed that the girl had been raped and murdered before being hanged. Ten years later, her cousin Miryam Charles made Cette maison [This House], her first feature. The film begins with a clear proposition: the actress Schelby Jean-Baptiste, playing Tessa, invites us on a journey through time to three places: Haiti, the United States and Canada. Facing the camera, the actress explains that the film is about her, Tessa in an adult body that never existed, and her mother. Once the invitation is clear, the journey begins. It starts with Tessa and her mother looking at a picture in which we see a view of Haiti, their country of origin. It is a highly theatrical staging, explicitly constructing the setting. Surrounded by darkness, the two actresses are sitting on a rug looking at the pretty landscape in the picture. The image is completed by the sound of the sea, which is very much present. The theatricality of the scene and the clear presence of the different elements of which it is made up show the construction of the fiction. As if the director wanted to make the fabrication of the film visible. And not only that, but Charles, in a beautiful 16 mm, managed to make film shine with all its power as she sets out to “write a story, another story. An impossible story”. Because film can do just this, tell impossible stories. Film makes it possible for Tessa herself to tell us her own story, her own birth and her own death.

Lur Olaizola

Lur Olaizola

Canadian International Documentary Festival, Olhar de Cinema (Curitiba IFF), Trinidad + Tobago Film Festival, Montréal Festival du Nouveau Cinéma, Viennale, Novos Cinema Film Festival

Official Selection 20

Chaylla Clara Teper & Paul Pirritano

France, 2022, 72 min, DCP, colour, French Spanish Premiere

Cinematography Paul Pirritano / Sound Clara Teper / Editing Pascale

Hannoyer and Manuel Vidal / Script Clara Teper, Paul Pirritano / Production Marc Fayer (Novanima Productions) / Selected filmography Demain l’usine (Clara Teper, 2016) / Visions du réel, États généraux du film documentaire de Lussas, Rencontres Internationales du Documentaire de Montréal, Traces de Vie

Chaylla smokes before going into a centre for prevention of domestic violence. This is to be followed by many other cigarettes: at her front door, on her way out of the doctor’s, outside a party. Cigarettes that punctuate the film like introspective parentheses, moments to stop and think and rethink what has already happened, what continues to happen, the next legal step to take. Pauses in which to gather the strength to carry on fighting to get out of a violent, abusive conjugal relationship that she has tried fruitlessly to save too many times. She is not alone: apart from the crucial relationship with her lawyer, Chaylla has the unconditional support of two invaluable allies, her best friend and her own mother in law, with whom she shares smiles, tears and songs.

The camera follows this young 23 year-old mother form northern France very closely, sometimes almost touching her face, allowing us to see much more than what the words say, and it does so for a considerable length of time (which we often notice first from the changes in her hair). We accompany Chaylla on a long path, a process of internal reconstruction and external recognition that, apart from the distinctive traits of each woman, each private relationship or each legal system, is shown to be largely universal.

Miguel Zozaya

21

De songes au songe d’un autre miroir

Yunyi Zhu

France, 2022, 16 min, DCP, colour, French Spanish Premiere

Cinematography

Raphaël Rueb and Yunyi Zhu / Sound

Raphaël Zucconi

and Déborah Drelon / Editing Yuyan Wang / Selected filmography

Tout ce qui était proche

s’éloigne (2021) / Berlinale Generation

How does one imagine without images? What are the dreams of people who cannot see like? How can they dream geometry or colours? How can they conceive in their mind of a concept like our reflection in a mirror, so abstract, so cold, so slippery?

“My hands are my mirror; it’s my fingers that give me my reflection”, says a little girl. Lewis Carroll’s Alice wondered, “And what is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?”. What must it be like to read that in Braille? We don’t know, because we can’t cross to the other side of the mirror. We can’t imagine her Wonderland without pictures, because we have a different concept of “wonders”: “My Wonderland is full of soft textures and there are lots of nice sounds, like the birds I can hear singing, and even the texture of cool grass beneath my head. This is my Wonderland; it’s not much, but it’s all I need”.

At a sensory education centre in Lille, northern France, artist Yunyi Zhu takes his camera to some blind girls to try to understand, through the art of images, what a world without images is like, Precisely because it’s an impotent tool, film might be the ideal tool to introduce is to an imperceptible perception, unreachable for those of us who can see, because it places us at a disadvantage, in the place of otherness: as one of the girls says, her story goes beyond our narrative.

Miguel Zozaya

Official Selection 22

Éclaireuses

Lydie Wisshaupt-Claudel

Belgium, 2022, 90 min, DCP, colour, French Spanish Premiere

Cinematography Colin Lévêque / Sound

Thomas GrimmLandsberg and Lucas Lebart / Editing Méline Van Aelbrouck / Production Les Productions du Verger / Selected filmography

Killing Time - Entre deux fronts (2015), Sideroads (2012), Il y a encore de la lumière (2006) / Visions du Réel, Festival Jean Rouch, Millenium, Etats-Généraux du Film Documentaire de Lussas, Filmer le travail

In Brussels, in the window of what looks like a shop, coloured letters say: La petite école (The Little School). There two women, Marie and Juliette, have set up a small school that takes children, whose parents are often exiles or refugees, who have never been to school and gives them a time to adapt to such an essentially strange place: a school. In this new in-between place they have invented and constantly need to reinvent, Marie and Juliette work with the children, and they also think, talk, confront other settings, both academic and institutional. This is a film that attentively observes a place, two women and some children. It’s a film about intelligence, about a constant to and fro between practice and theory: we think because we do, we do because we think. Words become actions, action generates new words. It’s exciting to see this: in a small place in the city two people are working on reality, and in doing so, as they make a reality they think about it and question it. Gradually they come to question the very place they come from, the place through which we all pass, school. Without realising, we have our certainties stripped away and at the same time we are shown that there, where the certainties come to an end, something can be done, something happens.

Pablo García Canga

23

El polvo ya no nubla nuestros ojos

Colectivo Silencio

Say of us [...] that we live in a country where the fires drew on the night-time cliffs the red shining of sickles and hammers.

Montserrat Álvarez

Peru, 2022, 25 min, super-8 to DCP, colour, SpanishQuechuaAshaninka

Spanish Premiere

Cinematography Luis Enrique Tirado / Sound Christian Ñeco / Music Iván Santa

María / Production Bergman was right

Films and Cineclub de Lambayeque / Festival de Lima-Filmocorto, Festival Internacional de Mar del Plata, Festival de Cine de Trujillo, Corriente Encuentro Latinoamericano de Cine de No Ficción, Transcinema Festival de Cine, Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival

2021 was the bicentenary year of Peru as a nation, though these last few years have not been its only ones. They have been full of fires. The first film by Colectivo Silencio marks this anniversary with a national memory that does not belong to the official celebrations, a memory of resistance that is no longer just a memory because today there are trenches in its streets. The film falls back on another history that belongs to it, not on the fiction that is a country, but on the history of film, of a political/poetic film that accompanies, that has accompanied on the screen voices, bodies, history lessons and a land that refuses to be just landscape. In different shots documents are read aloud, making them indelible, proof of past and future struggles: indigenous and peasant, rural and urban workers, women and dissidences. Each of them shines with a light of its own, and a beauty that springs from the wish to put a lasting memory back on record, to take victims mourned only by those closest to them and make them live on in memory. Everything has a time to be looked at and admired, everything that has been taken away and, by being filmed, is returned to them: the sky, the pasture, the cement, the street lights, the outside walls of a burnt-down building, the graves of the dead. Injustices that the date shows are old are strung together, as if those white national struggles —the wars of independence— had left a land free from slaveries. As if they hadn’t carried on.

Lucía Salas

Official Selection 24

Eventide Sharon Lockhart

USA, 2022, 35 min, DCP, colour, silent Spanish Premiere

Cinematography Simon Gulergun / Sound Tom Ozanich / Editing May Rigler / Production

Lockhart Studio / Selected filmography

Rudzienko (2016), Pine Flat (2005), Double Tide (2009), Podwórka (2009), Lunch Break (2008), Teatro Amazonas (1999) / Toronto International Film Festival, Viennale

Night falls on a rocky beach. The evening is almost over, but the last part passes slowly. Almost so slowly that it’s hard to know whether it will ever get dark, or even whether it was daytime before. This is immersion, this is its effect: the body itself disappears, leaving only eyes and ears. While the sky creates the suspense of its own opacity and blue takes over, a light appears among the rocks. Is it the reflection of something or is there someone there? In a game of darknesses, in Eventide it’s hard to tell whether people imitate the sky or it’s the sky that wants to be a person. There’s a competition between sky and earth, each with its own possibilities. Is it magic? No, they’re the Perseids, seen from Gotland in Sweden. A miracle that’s a little natural, and also a little the result of the dark room, of the passing of time and of sitting —as we aren’t often— with our eyes accustomed to seeing black on black. The most recent film by Sharon Lockhart, made with a small bunch of friends and their hands (with their mobiles) shining, explores the strangeness of a moment when the eyes aren’t the object able to capture the most light and shade. Farewell —perhaps— to purely human perception.

Lucía Salas

Lucía Salas

25

Maayo Wonaa Keerol

Alassane Diago

SenegalGermany-France, 2022, 105 min, DCP, colour, French-WolofPeul-Arabic Spanish

Premiere

Cinematography

Michel K. Zongo / Sound Michel Tzagli and Philippe Grivel / Editing Catherine

Gouze and Alassane

Diago / Production

Michel Klein (Les Films

Hatari), Katy Lena

Ndiaye (IndigoMood Films), Raphael

Pillosio (L’atelier documentaire)

and Heino Deckert (Ma.ja.de.

Filmproduktions) / Selected filmography

Rencontrer mon père (2018), Tribunal du fleuve (2017), La vie n’est pas immobile (2012), Tristesse dans un bar et Dégoût à l’épicerie (2012), Les larmes de l’émigration (2010) / Semaine de la Critique de Locarno, IDFA, Göteborg Film Festival, Black Movie Festival International de Films Indépendants

In Africa, since colonisation there have been frontiers running for hundreds of kilometres in straight lines across the desert. Others take a geographical feature as their pretext, for example the course of a river. When a frontier is invented, groups of people are divided. This is what happened to the inhabitants of Mauritania and Senegal from 1960 onwards. That river frontier, as well as being arbitrary, was superimposed on deeper divisions. Arab and Berber herdsmen had been fighting since ancient times with black farmers on the river banks. In April 1988, the flocks of some Mauritanian herdsmen went to graze for the millionth time on the land of Senegalese farmers. Three years of war followed, on both sides of the border. Tens of thousands of people were brutally killed. Thousands more were expelled and never returned. Alassane Diago, who was three years old when the war began, talks to Abdoulaye Diop, who has not returned to Mauritania since then. This is the prologue to this film, which also aims to serve as a provisional act of reconciliation. Alassane brings together witnesses and survivors on the Senegalese side of the river, wrapped in the most beautiful fabrics you have ever seen, in the shade of the ginkgo trees, under a small fabric canopy. If words can be as eloquent as gestures in this place, it’s because they’re surrounded by an attentive silence. Outside, life shines beside the water, chores, animals, children.

Manuel Asín

Official Selection 26

Miyama, Kyoto Prefecture

Rainer Komers

Japan-Germany, 2022, 97 min, DCP, colour, GermanJapanese International Premiere

Cinematography

Rainer Komers / Sound Michel Klöfkorn, Oscar Stiebitz and Jonathan Schorr / Editing and co-author

Gregor Bartsch / Production Rainer Komers / Selected filmography Barstow, California (2018), Kursmeldungen (2017), 25572 Büttel (2012), Milltown, Montana (2009), Kobe (2006), Lettischer Sommer (1992), Zigeuner in Duisburg (1980) / DOK Leipzig, Duisburger Filmwoche, Blicke-Filmfestival des Ruhrgebiets

The small town of Miyama, fifty kilometres from Kyoto, is visited by flocks of tourists attracted by its traditional houses. But however special it may be as a town, its inhabitants’ work must go on. The rice fields need preparing and sowing, the animals need feeding and slaughtering, people have to go hunting and fishing, clearing and fencing the fields, to cut trees down in the forest. Under the overcast sky, everything is verdant and fertile, but it takes work. Is this life all work? There is also time to learn to play traditional instruments, to eat and drink with others after practising. This is how it’s been for generations. Work and leisure are repeated as life follows its course. “As I’m Japanese”, says one of the residents, “When I die I expect to disappear”, as she recalls the annual cycle of the cherry blossom. So we accompany the inhabitants of Miyama in this series of almost folkloric scenes that illustrate the daily cycles, until we realise that, at some unknown point in the film, in some cut between sequences, we’ve started to subtly realise that its charm lies in the cyclical rather than the dramatic. We see the process of things without wanting to know where they are heading; a new disposition towards the film grows up in us.

There is also a westerner living in Miyama, Uwe, a German who has been in Japan for thirty years. The first sign we see of his enthusiasm for the country is that he is a capable player of the shakuhachi, the Japanese traditional flute. The way he throws himself into everything he does has a curious effect: at once integrated and foreign in this small place, Uwe appears to be the bearer of the awareness that’s needed for everything to carry on flowing without interruption. And yet, a fundamental, universal rule says that the only thing that is forever is change. This comes along as gently as the passing of the days. It’s through Uwe that we learn once again that change is the flip side of constancy, that insisting on the same has new consequences of its own and where there is no variation there is paralysis. A whole series of mysteries that we must explore in the same spirit. Bárbara Mingo Costales. Bárbara Mingo Costales

27

Nagyapám kertje

Varga Gábor

Hungry, 2021, 24 min, DCP, colour, Hungarian Spanish Premiere

Cinematography Varga Gábor / Editing Csenge

Hegedüs / Selected filmography Csendes

környék - A quiet neighborhood (2020) / Odense Film Festival, Budapest International Documentary Festival

Varga Gábor’s grandfather is a man who, as a child, ate cherries down to the stone, and made his living dancing on ladders (as he demonstrates for us by walking over a stepladder like a crane fly). He seems to have spent his whole life working, doing things constantly, because he likes it. He digs the ground, repairs a bicycle bell to make a child happy, perches up on the roof to mend it, and looks after his animals and his garden devotedly. He radiates affection as he sings to his rabbits, picks apart a corn cob for his pigeons, strokes the new-born chicks and roasts pork over the fire with his grandson. He says that he does what he does today thinking of future generations. What will become of this little world when he’s not there?

It might seem that Nagyapám Kertje is something that has been done many times, that we have seen many times: a film by a young film student about their grandfather. Nor does it adopt an unprecedented or experimental approach; in fact, he goes about it with total simplicity. However, despite the humility of this début film, it manages to harness the film-maker’s ability to show us in a few minutes something as vast as the passing of life, something as delicate as the process of growing old, of changing from a strong, tirelessly hard-working person to a fragile one. As fragile as the little world in his garden.

Miguel Zozaya

Official Selection 28

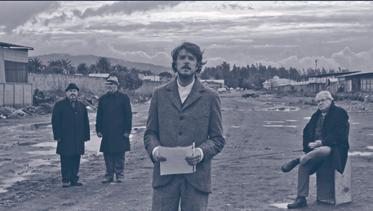

Notas para una película Ignacio Agüero

Chile-France, 2022, 105 min, DCP, B&W, French-SpanishMapudungun (mapuche) Spanish Premiere

Cinematography David Bravo / Sound Carlo Sanchez and Andrès Polonsky / Editing Ignacio Agüero, Claudio Aguilar and Jacques Comets / Production Agüero y Asociado Ltda / Selected filmography

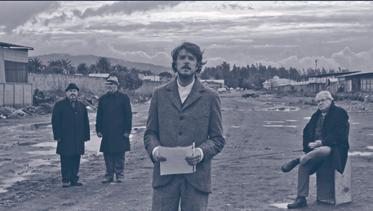

Gustave Verniory wrote Diez años en Araucanía. 1889-1899 about a decade he spent in Chile beginning when he was just under twenty-three and an engineer there to develop a railway network. He found himself in a country he thought was exotic, and soon learned was more than just the backdrop for his adventures. Notas para una película [Notes for a Film] is one of those films that takes a “What if...?” that comes true. What would happen if we could make two times -past and present- coexist, if we could tell those in the past what they did not know or not hear then. What would happen if author and character, one from the 19th century and the other in the 21st, could take the train of history, the one that’s never supposed to come along twice. Agüero and Verniory travel Araucania recreating memories and seeking out others that weren’t there before. They roam about in search of the film (unless the film finds them first), travelling through space but also time. they go to a Mapuche lof to visit those who were displaced then, to talk to a place where memory is oral, where the record of a genocide travels in the form of family and community memories. A film made of books, places and other films, objects that could have witnessed that was and is done in the name of progress. A far-off past that is tied in a flash to the most recent past.

Lucía Salas

Nunca subí el Provincia (2019), Como me da la gana II (2016), El otro día (2012), Aquí se construye (o Ya no existe el lugar donde nací) (2000), Cien niños esperando un tren (1988), Como me da la gana (1985) / IDFA, Festival Internacional de Cine de Mar de Plata, Festival Internacional de Cine de Valdivia, Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine de La Habana

29

Notre village Comes Chahbazian

Belgium, 2022, 67 min, DCP, colour, Armenian European Premiere

Cinematography

Comes Chahbazian / Sound Jaouen Le Fur and Pauline PirisNury / Editing Pauline

Piris-Nury / Production

Matière Première / Selected filmography

Ici-Bas (2010), Untitled (2002), Y.U.L. (2002), À Suivre (2001)

The houses here are made of grey stone. That’s the way it is, as they say, and if they don’t go with the green of the surrounding woods it’s their problem. We make life with whatever we have to hand. The places we live in impose themselves in some ways. Some of these are violent. Like for example being in between two communities with a long-standing conflict that flares up again and again. Then men are sent to war, teenagers die at the front and women become everybody’s widows and mothers.

The disintegration of the Soviet Uni9on destroys the lives of the inhabitants of Artsaj, between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Old grudges about frontiers and property flare up once more. Since the late 1980s they have been forced to live not exactly among ruins, but in a state of alert where everything is provisional. Upon visiting “our village”, we can see how life goes on despite everything, how children play with whatever they find, the bee keeper starts making honey again, the nurse fills the syringes, the fisherman pulls up a net full of fish, the butcher slaughters the pig, and also how the non-human world gets on with its own life: the spider weaves its web, the cat licks up the pig’s blood. All these goings-on seem to be imbued with a hidden meaning. What vestiges are we looking for among these pictures?

So let’s allow the neighbours to tell us what happened. Through their words we might be able to better understand their grief. Under a lighting that creates a theatrical air, each one, rather than explaining, lists the events that have made up their history. The memory of the fateful day when everything went wrong inevitably becomes a ballad that takes up the subterranean currents of all the feelings and preserves them. Like this they take on a new power, almost like omens. This stylisation of the production, alternating with sequences of a naturalist nature, illustrate the biblical adage that one who sows the wind reaps the whirlwind. That words are a symbol but they manifest themselves in the flesh is something that in “our village” we learn with blood.

Bárbara Mingo Costales

Official Selection 30

Teléfono, Navidad

Malena Zambrani

Argentina, 2022, 14 min, DCP, colour, Spanish World

Sound Santiago Haddad / Editing

Malena Zambrani

Sound Santiago Haddad / Editing

Malena Zambrani

Now that ones and zeros, yeses and nos have for many become the most valuable fuel, Malena Zambrani shows us the sources of what we pompously call “information”. What is her starting point? A situation that might sound like a joke: the compulsive congratulatory calls of a mother and her son, addicted to the telephone, on what might be the peak of their addiction: Christmas Eve. Festive symbolism triumphs, with everything it mobilises in terms of sentiments. There’s a climate that the film successfully captures, in a tone of laughter but not mocking, rather a kind of joy and joviality (a rare, difficult register to achieve). The topic of the film, recreational telephoning, so to speak, may seem capricious as much as subversive, as the film succeeds in showing, without any solemnity and without saying it as such, how far in recent decades the privatisation of the telephone has become the core of our domination and servitude. This can be seen off-centre, or even better in the mirror. The film wittily, subtly focuses on what to others might seem imperceptible or trivial. The thing about mirrors is that they invert what doesn’t seem to be inverted: the telephone Baby and Julio abuse so much is no longer today’s telephone; its antiquated uses might seem even more immoderate than our own (they call more people, further away, and nobody ever manages to talk to them -they’re always “engaged”). Calls for them always go in a centrifugal spiral, from their house to the world. Seeing this in the mirror makes us stop and think. The narrow space in the hall with the little table for the telephone is for Malena nothing less than what the South Seas or the pole were for Flaherty or Murnau. Manuel

Asín

31

Premiere

Tembiapo pyharegua (Trabajo nocturno)

Christian Bagnat & Elvira Sánchez Poxon

Spain, 2022, 120 min, DVCPAL to DCP, colour, GuaraniSpanish

World Premiere

Sound Organic Audio Studio / Editing Elvira Sánchez Poxon and Christian Bagnat / Selected filmography Los Ángeles (2011), Los empleados de Kaufmann (2008-2009)

It seems that dreaming is the real night work, and night is the time that gives form to this mass made of present, past, future and everything that’s invented. The work the mind does when we aren’t watching. It’s everything that isn’t —really— work, but free time, truly free and filled with curiosity. Tembiapo pyharegua follows the nights (which are sometimes days, moments of spiritual night) of a migrant community in Cuenca, people from Paraguay who speak Guaraní, among themselves and with the film. It follows them in different ways, as in episodes. There are stories about birds captured by kings, coming-out dances, first love, sections in which the story of migration merges into the landscape, the desire to return to a place of their own..., as if the film wanted to think of an infinite number of forms for a flat plane to take, because there are an infinite number of ways of being far from home. The thing about migration is that it happens all the time, in a story with no end because life splits up and is repeated: life there, where one sometimes is like a ghost; life here, where one lives somewhat absently, running the risk of becoming invisible. There is a shared dream, but one with infinite variations: going back. And then? A dream that might be anxious nightmares. This dream is the film, which is a bright, artificial, democratic night. Lucía Salas

Official Selection 32

Tótem Unidad de Montaje Dialéctico

México-Chile, 2022, 65 min, digital to DCP, colour, Spanish European Premiere

Cinematography and editing Unidad de Montaje Dialéctico / Sound and music

Sinewavelover / Production Unidad de Montaje Dialéctico & Pequén Producciones / Selected filmography Bodegón 1 (2022), Meteor (2022), Theses on Cavern Cinema (2021), Cabo Tuna or the Management of the Sky (2021) / Muestra Internacional Documental de Bogotá

“In nature we never experience anything in isolation, but everything is connected to something else in front of it, beside it, under or over it”. Goethe said this, and was quoted by Eisenstein. Tótem, the work of a collective named Unidad de Montaje Dialéctico, is made of connections. Between vision and sound, between past, present and future, between essay and narrative. Tótem is a film made twice: one voice that recites an essay about forced disappearances in Mexico (their history, their forms and their causes), and another voice that explains the finding of an Olmec head lost in the bottom of a river. But Tótem is not just made up of words, it is also made up of images. Images that do not match what the words are saying, yet gradually start to match, distant and close at the same time; in the remains of a small boat our mind starts to see an Olmec head, in a flock of birds we see the multiplication of criminal organisations. All the time we are seeing and hearing more than what we really see and hear, because in the meeting between image and sound something else emerges, a meaning and a form. But also, the film does not limit itself to describing the past and the present. In describing the present of those struggling to find their lost ones, it proposes a new possible reality. By recounting the past, by describing the present, it proposes a future.

Pablo García Canga

33

Retrospectives

Other Times Are Coming | Es nahen andere Zeiten

The films of Peter Nestler

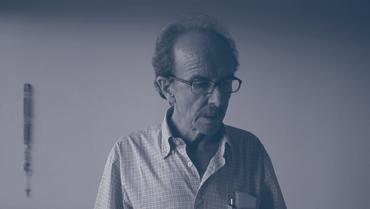

This programme is an introduction to the work of filmmaker Peter Nestler. Its title is borrowed from a poem by the Communist German poet Johannes R. Becher, written in exile in 1941-1944, and quoted by Nestler in a text about the responsibility of the filmmaker and the political crisis in Chile in the 1970s. The call to resistance, hope and change has been a constant in Nestler’s work since he began making films in the early 1960s. As Nestler wrote, the greatest responsibility of the filmmaker should be “to acknowledge, to recognise and to say with others: this must be changed, or that must be preserved, or not overlooked”. From his early portraits of rural and industrial communities in Germany and England fallen by the wayside of the ‘economic miracle’, to his ‘biographies of objects’ documenting the lives of materials and their production processes, to his numerous investigations into the histories of persecution, oppression and resistance, of fascism and its frightful continuation, the films of Peter Nestler have never stopped digging and unveiling what is commonly overlooked or wilfully suppressed, in defiance of historical amnesia and political inertia.

Retrospectives 36

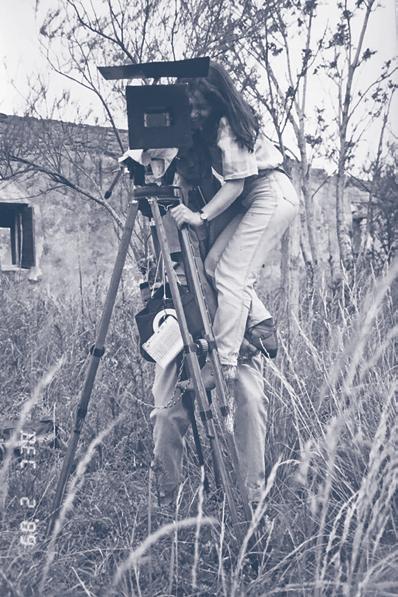

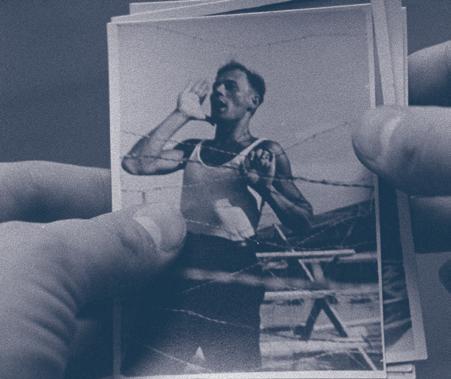

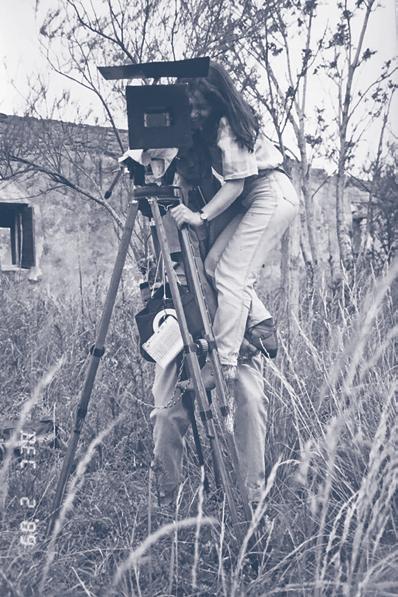

From the 1960s until today, Nestler has directed over sixty films, many of them in collaboration with his wife Zsóka Nestler, as well as with other filmmakers and artists. Nestler studied painting and printing, worked as a merchant sailor and a forester and was an actor in feature films. His first film, Am Siel, from 1962, was the first of a series of works about the transformations of the rural world in Germany. The films from the 1960s show how the lives of the working class were affected by the changes brought about by economic and industrial policies in West Germany. They deal with the violent legacies of Nazi Germany, their continuation and consequences in the postwar social-democratic Germany, as well as with the histories of political resistance and labour movements.

Formally, his filmmaking practice went against the principles of direct cinema which defined much of the documentary filmmaking of his time, also in Germany -the films take a step back to research, dig deep and analyse each situation for what it entails. In 1965-1966, together with Reinald Schnell, Nestler made a film in Greece, Von Griechenland, presaging the emergence of the military dictatorship only two years before it was established. The clearly expressed political positions in his films went against the political consensus and anti-communist sentiment prevalent at the time, which made it difficult for Nestler to continue working in Germany. In 1968 he relocated to Sweden, his mother’s birthplace, where he continued to create most of his work the following decades. He worked for public television, producing, buying and dubbing programmes for children and young adults, and also working on his personal projects in collaboration with Zsóka Nestler.

37

Many of these films were concerned with the criminal legacies of Nazi Germany (and European collaboration), its past and how they persist in the present. The films reveal narratives of violence, injustice and resistance. Works such as Zigeuner sein (1970), about the persecutions and injustices committed by the Nazis against the Roma and Sinti communities and their resistance are among the most important works made by Peter and Zsóka Nestler. An anti-fascist, anti-war, ecological, internationalist, and humanist stance runs through all the films.

This period also saw Nestler making films focused on international politics and struggles, against the war in Vietnam or on the situation in Chile (often working with the Chilean community in exile in Sweden). Peter and Zsóka Nestler have worked on several films about the working conditions of migrants, political exiles and ethnic minorities (in Sweden and elsewhere). Always working for television, they made a series of documentary essays about the way objects and materials are produced, the histories of capital, manufacturing and industry. These works show the filmmakers’ interest in traditional crafts and in the lives of artists who express their politics through their work. As he said in an interview, “visual art and sculpture was for both me and Zsóka a way to understand the world, to live consciously, to enjoy beauty but also to see -to dare seeing- the abysm of human existence”.

Retrospectives 38

Working for young audiences allowed them to develop a didactical, formally clear, informative and engaging film process. The films never cease to explore the complex relations between sound and image through the use of narration, testimonies and music, brought into a dialectical relationship with materials collected from a diverse range of sources (photos, texts, prints, music, extracts from other films). The distinct use of voiceover in Nestler’s films rejects the conventions of neutral television documentary narration, offering instead an active involvement with the subjects.

From the end of the 1980s onwards, Peter Nestler again made films in Germany, working for the first time in feature documentaries. These included films about traditional crafts and the history of the people who make them (Zeit, 1992), the centuries-long history and persecution of Jews in Frankfurt (Die Judengasse, 1988) and the histories of resistance against national socialism (Die Verwandlung des guten Nachbarn, 2002). He has also produced a series of finely crafted travelogues, inspired by his strong commitment to the preservation of nature and of local and indigenous cultures (Die Nordkalotte, 1991, Pachamama-nuestra tierra, 1995). The last years mark a continuity in his work, with remarkable films, for example on the work that Pablo Picasso did during his stay in Vallauris (Picasso in Vallauris, 2021) and even more recently a diptych that takes up the theme of injustice committed against the Roma and Sinti people and their resistance (Unrecht und Widerstand, 2022 and Der offene Blick, 2022).

39

Opening session of the festival

Die Donau rauf

Peter Nestler and Zsóka Nestler

Sweden, 1969, 28 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, colour, German

Zeit

Peter Nestler and Zsóka Nestler

Germany, 1992, 43 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, colour, German

Retrospectives 40

Die Donau rauf (1969), made in collaboration with Zsóka Nestler, is a slow-moving journey up the Danube revealing many-layered narratives unearthed from the ancient and recent past blending with the slow progression of the riverboat, the landscape and images of people at work. The film addresses the cultural, social and political history of the river by bringing together scattered histories, from remains found on the riverbanks to the history of shipbuilding and commerce between the two world wars, from the peasants’ revolt in the 17th century to the horror of the Holocaust (through a poem by Miklós Radnóti read by Zsóka Nestler). Zeit is a film that is at the heart of Peter and Zsóka’s practice and their interest in traditional art forms and the people who make them. In the film six painters and artists from Hungarian villages talk about their lives and display their works for the camera. The film conveys the generosity shared in this exchange between the artists and the filmmakers, who make a unique portrait about the craft behind these works, the freedom of those who make them and the way they represent a personal and collective history.

41

Session 1

Chilefilm

Peter Nestler and Zsóka Nestler

Sweden, 1974, 23 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, B&W, German

Mi país

Peter Nestler

Sweden, 1981, 7 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, colour, silent

Pachamama-nuestra tierra

Peter Nestler

Germany, 1995, 90 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, colour, Spanish

Retrospectives 42

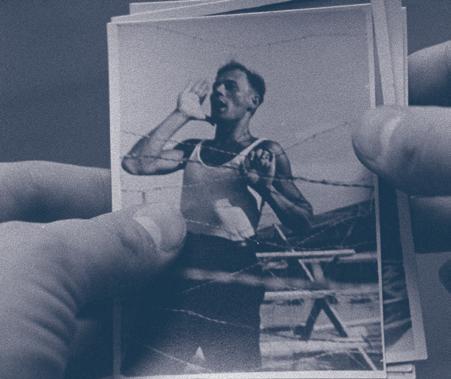

Chilefilm is an introduction to the background of the military coup in Chile using historical documents, drawings and music. The film is a plea for the cause of the Unidad Popular: “There is a connection between the terrible poverty of the many and the enormous wealth of a few”. The film was produced for young audiences for Swedish Public Television and it was never broadcast. Mi país is a short visual essay on the history of Chile made up of popular works by young exiled Chileans in Sweden with paintings by Nicolas de la Cruz and Jorge Kuhn, engravings by Rolando Pérez, music for the Indian harp by Adrián Miranda. Pachamama-nuestra tierra is a travelogue filmed in Ecuador. Peter Nestler wrote about it: “The film is about the indigenous cultures of Ecuador, of what is past and what is preserved, of destruction and resistance, of persisting in new ways, of music in the villages high up in the Andes, of music in the cities and in a tropical climate among descendants of African slaves. The film is about Earth, about working with Earth, sacred to the indigenous people. An account of beauty that silences, of friendliness, also grief”.

43

Session 2

Spanien!

Peter Nestler, Zsóka Nestler and Taisto Jalamo

Federal Republic of Germany, 1973, 43 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, B&W, German

Von Griechenland

Peter Nestler in collaboration with Reinald Schnell

Federal Republic of Germany, 1965, 28 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, B&W, German

Zigeuner sein

Peter Nestler and Zsóka Nestler

Sweden, 1970, 47 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, B&W, German

Retrospectives 44

Shot in Spain, Finland, Sweden, and West Germany, Spanien! is a film about internationalism and solidarity, using personal testimonies from former members of the International Brigades who joined the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War and from members of the Comisiones Obreras. Von Griechenland describes the political situation in Greece in 1964-1965, two years before the coup d’etat which led to the military dictatorship. Peter Nestler said about the film: “It was a tense period when we got there. I filmed the demonstrations and at the same time we were looking for the traces -the historical traces- of the times of the German occupation and the resistance movements against the Germans”. One of Peter and Zsóka Nestler’s most important works, Zigeuner sein confronts the persecution of the Roma and Sinti peoples in Germany under Nazism and its persistence after the war: “In the sixties I learned of this constant injustice, was made aware of it, especially by the works of the painter Otto Pankok, whom I met in 1965, and by the social work of Birgitta Wolf, by the writings of Hermann Langbein, who was one of the main witnesses in the Auschwitz trial. I learned about the uninterrupted discrimination against the minority in Germany and Austria, where everything revolved around reconstruction, about economic advancement. The war crimes were put to rest, and the many perpetrators, former SS members and criminal police officers, as well as the ‘racial hygiene researchers’, returned to their offices and positions, continuing to discriminate and exclude the Sinti and Roma for decades”. Peter and Zsóka Nestler consciously used the derogatory term ‘zigeuner’ (Gypsies) in the title in 1970 to expose the violence that it entails. Their film begins with the words: “Those whom we call ‘gypsies’ call themselves ‘Roma,’ which means ‘people’. Many of them feel afraid when they hear the word ‘gypsy’. They fear it could all happen again”.

45

Session 3

Fos-sur-Mer

Peter Nestler and Zsóka Nestler

Sweden, 1972, 24 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, B&W, German

Das Warten

Peter Nestler

Sweden, 1985, 6 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, colour, German

Die Nordkalotte

Peter Nestler

Germany, 1991, 90 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, colour, German

Retrospectives 46

Fos-sur-Mer is set against the backdrop of the industrialisation of the commercial port of Fos-sur-Mer, northwest of Marseille. He gives a damning account of the port’s development into an industrial park since the late 1960s and the destruction the area has suffered. It highlights the poor working conditions of some 7,000 migrant workers who work and live on this industrial site, many of them from the Maghreb. A plea against the destruction of the photo archives of Swedish national television, Das Warten tells the story of a tragic mining accident that occurred in Northern Silesia in the 1930s, in which dozens of miners lost their lives. The film saves from oblivion one of the “many disasters in these years of rationalisation” and highlights the violence caused by extractivism and the exploitation of natural resources. Die Nordkalotte is one of Nestler’s most remarkable films. It was shot between Sweden, Finland, Norway and the USSR and documents the devastating impact of industrialization on the landscape and lives and culture of the region’s indigenous peoples. It is a tribute to the Sami people and their resistance, who in their own words talk about the destruction of their livelihood, of nature and the importance of preserving their customs and language. Nestler dedicated this film to his friends, the filmmakers Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet.

47

Sessions 4 & 5 Unrecht und Widerstand

Peter Nestler

Germany-Austria, 2022, 113 min, HD, colour, German

Der offene Blick

Peter Nestler

Germany-Austria, 2022, 101 min, HD, colour, German

This diptych deals with various forms of resistance of the German and Austrian Sinti and Roma throughout the last eighty years. It is about rebellion against injustice and their insistence on dignity and fairness. Unrecht und Widerstand tells the story of Romani Rose, his family and his fellow fighters, their work for justice, and their enduring resistance and perseverance. It is the painful story of a minority between trauma and self-assertion, which suffered violence and official harassment throughout the post-war period up to the present day and was only recognized thanks to the civil rights movement. For Roma and Sinti who survived the genocide, exclusion, poverty and official harassment were part of everyday life. The Porajmos, the genocide of the minority, was not officially recognized until 1982. In this film

Peter Nestler describes the long way out of lawlessness and discrimination into the civil rights movement. Their tireless commitment testifies to civil courage and a sense of citizenship, to their resolute commitment to the coexistence of different cultures and to a forward-looking understanding of democracy. The film works with archive material and commentaries and is framed by a conversation with Romani Rose about his family history and his experiences as a civil rights activist.

Retrospectives 48

Der Offene Blick details the methods of resistance of the Roma and Sint. The second film of the diptych features a number of artists who throughout history have expressed their personal experiences in rich and open ways through writing, painting, film and music, using their work as a form of cultural celebration and remembrance but also of revolt. Rosa Gitta Martl and her daughter Nicole Sevid read short texts in memory of the people who died in the Upper Austrian “Gypsy camp” of Weyer. Apart from a series of 32 colour slides photographed in 1941, there are no other remembrances of these people. The film highlights the work of artists from the past and the present. It commemorates the work of Ceija Stojka (1933-2013), an Austrian writer, painter, singer, activist and survivor of the Nazi concentration camps Auschwitz, Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen, whose work expresses revolt and resistance. Film-maker friend Karin Berger recalls her work, which had a great influence on other Roma and Sinti. Spanish-born painter Lita Cabellut works across media, using painting, video and dance to address social issues such as discrimination. The strength of her work is expressed in the film. She talks about her work as an art director for a film about Carmen Chaplin, about the presumably Roma background of her world-famous grandfather. Film scholar Radmila Mladenova discusses the relationship between cinema and photography and the portrayal of racist stereotypes, for example in an early film by D. W. Griffith or László Moholy-Nagy, and offers an alternative perspective seen, for example, in photographs that show other ways of portraying the Sinti and Roma in a more just and egalitarian way. The film is accompanied by the music of the orchestra Roma und Sinti Philharmoniquer, which brings together musicians from all over Europe to talk about their experiences with music. In recent years, things have changed for the better for the artists. For example, the Kai Dikhas Gallery and Foundation, under the direction of Moritz Pankok, offers artists a continuous forum to develop and exhibit their work.

49

Session 6 Am Siel

Peter Nestler in collaboration with Kurt Ulrich

Federal Republic of Germany, 1962, 13 min, 35 mm transfer DCP, B&W, German

Ödenwaldstetten

Peter Nestler in collaboration with Kurt Ulrich

Federal Republic of Germany, 1964, 36 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, B&W, German

Die Judengasse

Peter Nestler

Federal Republic of Germany, 1988, 44 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, colour, German

Peter Nestler’s first film, made in collaboration with Kurt Ulrich, is a portrait of a small and quiet village in East Frisia in Germany, seen from the perspective of an old dike sluice. The text, written and narrated by poet and artist Robert Wolfgang Schnell, speaks about the history and life of the village and the toil of the fishermen. The film “mirrors Germany in a village”, as Nestler says, evoking the war and the change caused by the disappearance of traditional livelihoods. Ödenwaldstetten is also a portrait of change, a film Nestler shot as a freelance assignment in the Swabian village of Ödenwaldstetten. It shows the life and work of the villagers and how much the process of industrialisation affected life in this agricultural community. We witness how handicraft and traditional agricultural tools are discarded and replaced by high-tech equipment and assembly line production. The film is also about the history of Germany and its relentless economic path after the war. The discovery of remains of the Jewish alley in Frankfurt motivated Nestler to reconstruct the centuries-long history of the Jews in the city in Die Judengasse. Despite the murderous period of German fascism, anti-Semitism and the Holocaust, an astonishing amount of historical evidence about Frankfurt’s Jews has survived. Nestler’s film traces this history from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Retrospectives 50

Foco Punto de Vista

April 2023 in Filmoteca de Navarra

Stoff (1)

Peter Nestler and Zsóka Nestler

Sweden, 1974, 30 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, B&W, German

Die Römerstraße im Aostatal

Peter Nestler

Germany, 1999, 89 min, 16 mm transfer DCP, colour, German

Retrospectives 52

Stoff (1) is part of a series of films made for television and aimed at young audiences. The series was dedicated to the history and techniques behind the production of objects, materials (paper, letterpress, fabrics, etc.), highlighting the differences between artisanal and industrial production and the labour and economic relations involved in each of these methods of making things. Die Römerstraße im Aostatal, which was unavailable in its complete version for many years and is presented here in a newly restored version, is a film documenting the area of the Italian Aosta Valley through its political, economic and cultural history. It is another remarkable work in which Nestler travels along the Roman road, a central artery used as a trade route for millennia, unearthing its history to better shed light on its present, looking at various aspects such as the traditions of craftsmanship and agriculture or the impact of industrial closures. The film makes a masterful use of sound, with the local dialect and traditional music playing an important role.

53

PUNTO DE VISTA COLLECTION Se acercan otros tiempos

El cine de Peter Nestler

Vol. 1

Peter y Zsóka Nestler

Textos, imágenes, conversaciones

Vol. 2

Reinald Schnell y Peter Nestler

Campesinos que pintan cuadros

This year’s publication accompanies the retrospective “Other Times are Coming | Es nahen andere Zeiten. The Films of Peter Nestler”. Published in two volumes, the first is a miscellany of documents about both Peter and Zsóka Nestler and some of their closest collaborators, who insist on the collective approach that their work has always followed: texts and interviews by and with Zsóka Nestler, Rainer Komers, Reinald and Robert W. Schnell, and Peter himself, several of his scripts and the filming diary of one of Peter’s most recent films, Picasso in Vallauris (2021), written and illustrated by Bassem Pablo, together with plentiful graphic material and an annotated filmography stretching over six decades of work.

The second volume is a reproduction of Bauern malen Bilder [Peasants Paint Pictures], a book with photographs and texts by Peter Nestler and Reinald Schnell published in 1974 in Germany. In 1964, on the way to Greece, they heard about a village in Yugoslavia, Kovacica, “the village of the peasant painters”. There, just as night was falling, they asked a man where they could stay. They ended up in a guest house with straw mattresses, and there they discovered that this small locality had seventeen working painters. They visited the village several times, getting to know the artists and their families and observing their work and their techniques. Nestler took photographs, Schnell took notes and from conversations between food, drink and paintings a book emerged, a book that is now being published for the first time in a language other than German, also fulfilling its authors’ initial plan: for the paintings to be reproduced in colour, as in the original edition they could only be printed in black and white for financial reasons.

The retrospective and the publication are the work of Portuguese programmer Ricardo Matos Cabo, responsible among other things for the Peter Nestler retrospective held in London in 2012-2013, and Argentinian programmer, critic and film-maker Lucía Salas, a member of the festival programming committee. They were also supported by the Goethe-Institut Madrid.

Retrospectives 54

Far from the trees

Once upon a time there was a holm oak as grand as a forest; next to it, the other trees seemed like grass. They had decorated it with ribbons and wreaths, and the nymphs often danced around it, hand-in-hand. The king of that country ordered that it be chopped down for he wanted the timber to build a palace. No one obeyed him, so he took the axe himself and the holm oak howled from the blow of the iron. Everyone was astonished; a servant who tried to stop him was decapitated by the king. From the tree, grown pale, blood flowed. It finally fell. Then Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, the “bearer of the seasons”, commanded Hunger to nestle itself in the guts of the king. Hunger obeyed and the king sent for that which is bred in the sea, on the land and in the air, he demanded food from food. Supplies that would have fed entire towns and cities were not enough for him, and the more he guzzled, the hungrier he was. He ate his fortune. He ate his father’s fortune. He sold his daughter. Nothing sated him, nothing, and “he started to bite off his own extremities, feeding his body, the poor fool, by tearing it to pieces”. The poor fool could have been called Capitalism.

Retrospectives 56

This film program stares into the abyss that now separates us from the trees. It considers the production of essential goods over the length (and width) of time and, consequently, pays tribute to original unproductivity, non-industrial modes of production, subsistence economies, and animals. It pays tribute to some humans too, all artists of their trade. Why? For love of our world, in defence of our world, to stoke the desire (or imagination) needed to defend it, so that the Samoan islands or the Orinoco delta do not vanish beneath the waters, so that Sicily or the Traslasierra valley do not vanish beneath the flames. Even though they will vanish. And because, as a poster found on the lower riverbank of the Ebro at the beginning of the seventies proclaimed: “They call development a miracle, but the work of a miracle is distribution”.

Curated and notes by Miriam Martín

57