Welcome to the unit ‘Design a Nutrition Plan for an Individual’. This unit is intended to provide nutrition coaches with the skills and knowledge needed to analyse a client’s nutritional aims and goals. The focus of this unit is understanding how to develop safe, functional, effective and customised nutritional plans that will allow clients to achieve their individual nutrition goals. Once the nutrition coach has completed the previous unit of ‘Apply the fundamentals of nutrition to meet a client’s needs’ and identified the needs and goals of the client, this unit then continues to the next steps in developing appropriate nutritional support programs for those goals and needs.

Firstly, nutrition coaches are reminded of their scope of practice and which client’s physical conditions they can and cannot support. Important concepts, such as basic anatomy and nutritional principles, are quickly reviewed to refresh the knowledge of nutrition coaches on the essential aspects of these concepts.

This unit then provides a detailed step-by-step process on how a nutrition coach can develop a customised nutritional plan for their client. This unit ensures the nutrition coach is aware of what goes into the process of developing a nutritional plan before diving deeper into the finer details, step by step. Nutrition coaches will develop the skills to perform the initial consultation and gather client information before learning to analyse the client’s nutritional intake, which includes everything from macro- and micronutrient intake to their discretionary food intake. This unit then provides practical guidelines for determining the client’s recommended nutritional requirements, using normal ranges and standards, and then comparing them to their current intake. Once the nutrition coach has obtained all of this information, they can either prepare a custom nutritional plan or provide general advice and guidelines, depending on what they think is more appropriate for that particular client.

This unit also extensively covers many other aspects that should be considered when a nutrition coach is designing a nutritional plan for their client and identifying particular areas that require monitoring. The nutrition coach will also be informed of the various non-diet factors that come into play when designing a nutritional plan and the importance of goal setting to successfully monitor and record the client’s progress.

One of the most beneficial aspects of this unit is the multiple meal plan examples provided at the end of the unit, which cover both male and female examples and their varying potential goals. Nutrition coaches will be able to see the end product they are working towards, allowing clarity in the process.

This unit will allow a nutrition coach to:

• Interpret a client’s pre-screen information to identify their nutritional aims and goals

• Analyse a client’s current dietary and lifestyle habits and patterns to establish factors that will prevent or influence the achievement of nutritional goals

• Develop a nutrition/meal plan based on solid nutritional fundamentals

• Support a client in implementing and monitoring the nutrition plan.

It is essential to understand that this unit will not provide the ability to develop nutrition/meal plans for:

• Individuals suffering from chronic health conditions or diseases

• People with medical conditions requiring specialised dietary advice

• Frail elderly people who are at risk of malnutrition

• Infants and toddlers

• Pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Individuals who present with a chronic health concern or appear to have symptoms indicative of a chronic health concern should be immediately referred to a medical professional or an Accredited Practising Dietitian (APD).

Like any professional field where advice is provided to a client about health and wellbeing, legal and ethical implications need to be considered. Incorrect nutritional advice provided to a client can have direct and serious implications for their physical and mental health. Accordingly, it is of utmost importance to understand the role and scope of practice as a nutrition coach.

Consequences for a client when practising outside the scope may include, but are not limited to:

• Negative impact on pre-existing health conditions

• Sub-optimal or dangerous nutrient imbalances, interactions, toxicities and deficiencies

• Negative interactions between nutrients and drugs.

As a result of this, the nutrition coach is at risk of:

• Potential legal proceedings for causing harm to a client, could incur considerable financial costs and lost time

• The potential loss of professional reputation.

A nutrition coach needs to have a sound understanding of the duty of care and responsible practice requirements inherent as a health practitioner. In Australia, the provision of health and fitness information is not governed under a single legislation, act or code but may instead be governed under codes of conduct for membership groups, peak bodies or industry authorities. However, any individual providing professional advice to clients about health and wellbeing will hold a duty of care which can be defined as “the legal obligation of professionals to safeguard others from harm while they are in their care, using their services, or exposed to their activities”.(1)

Under this concept, a nutrition coach who has provided incorrect nutritional advice, supplied or recommended products that harm a client’s health, or indirectly contributed to a client’s injury or illness through incorrect, outdated or inappropriate nutritional support services, may be in breach of their duty of care.

Health professionals are bound by additional state and federal legislation and acts relating to both health and safety, and privacy and confidentiality. There is a responsibility for health professionals to ensure that a safe, hazard-free environment is provided to clients when conducting their practical pre-screen and mentoring activities. This means that the work environment should be reviewed to identify, remove or control hazards and practical activities involving clients, should be evaluated for the risk of causing harm.

Safe Work Australia leads the development of national policy to improve work health and safety, and workers’ compensation arrangements across Australia. However, it does not regulate or enforce Workplace Health and Safety (WHS) legislation. Business owners, instead, must meet the WHS requirements set out in the acts and regulations in their state or territory.

CLICK HERE to understand more about the benefits to business owners as well as the rights and obligations as a small business owner.

Across the range of support provided to clients, nutrition coaches will also be provided with personal and confidential information such as contact information, lifestyle patterns and habits, family histories and detailed medical information. In Australia, professionals are bound by the Privacy Act 1988, which regulates the handling of personal information. The Act is underpinned by thirteen Australian Privacy Principles (APP), which govern the collection, processing, storage, protection and dissemination of personal information relating to individuals.(2)

As a result, all information is considered confidential and is not to be discussed with anyone, with the possible exception of other health professionals who are currently treating or are being referred to treat the client and with the client’s consent obtained. When discussing the general nature of the consultation and seeking advice from other health professionals, care must be taken that the client’s contact details, such as their name, address and phone number, are not disclosed.

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) is an Australian Government statutory agency. It is responsible for privacy and information policies, freedom of information and provides information and advice to individuals, businesses and agencies.

CLICK HERE to view the Australian Privacy Principles (APP), which outline the obligations nutrition coaches hold in relation to client information.

Nutrition coaches are reminded to refer back to their scope of practice (SoP) (Nutrition Council Australia, 2018) for important information and requirements regarding duty of care, workplace health and safety, and client confidentiality.

Client support must be approached with a sound understanding of the nutrition coach’s scope of practice. Which means understanding what advice a nutrition coach is qualified to provide and to which clients, and in what circumstances they should make a referral to a medical or allied health professional (AHP). These parameters are developed and articulated within national guidelines in many medical fields provided by industry associations or similar organisations.

So, what is within the scope of knowledge and experience of a nutritional advisornutrition coach, having completed the 11046NAT - Certificate IV in Nutrition? This qualification provides a strong knowledge base in nutrition and the application of nutritional guidance to individuals with no underlying health conditions.

Based on the content of this course, the following is within a nutritional advisornutrition coach’s scope of practice:(3)

Provision of nutritional information and guidance to otherwise healthy individuals based on nutritional scientific evidence.

Provision of nationally endorsed public health information that will educate and support positive client health outcomes.

Engaging with other Health Professionals and utilising best practice referral/feedback processes to optimise client health outcomes.

Use of evidence-based protocols to enhance client exercise adherence through goal setting, motivation, guidance, social support, relapse prevention and feedback.

For athletes who do not have, or are not suspected to have, any underlying chronic health conditions, nutrition coaches can:

• Develop personalised meal plans

• Provide specific nutritional information and development of tailored nutritional plans

• Provide recommendations on non-prescription supplements and dietary products with supporting nutritional advice.

In addition to the above, a nutrition coach has the skills and ability to:

• Interpret a client’s pre-screen information to identify their nutritional aims and goals

• Analyse a client’s current dietary and lifestyle habits and patterns to establish factors that will prevent or influence the achievement of nutritional goals

• Develop a nutrition/meal plan based on solid nutritional fundamentals

• Support a client in implementing and monitoring the nutrition plan

The scope of practice places significant responsibility on nutrition coaches to conduct a detailed screening process to ensure that the client falls within their scope of practice.

It is essential to understand that this unit will not provide nutrition coaches with the ability to develop nutrition/meal plans for certain population groups.

The following fall outside of the nutrition coach’s scope of practice:

• Individuals suffering from chronic health conditions or diseases

• People with medical conditions requiring specialised dietary advice

• Frail elderly people who are at risk of malnutrition

• Infants and toddlers

• Pregnant or breastfeeding women

Any indication of a chronic health condition or the above-mentioned population group should automatically result in the nutrition coach referring the client to a suitably qualified AHP such as a General Practitioner (GP) or an Accredited Practising Dietitian (APD) for review and qualified assessment.

It is important to remember that the reference to chronic health conditions refers to an illness persisting for an extended period of time or constantly recurring.

Examples of chronic health conditions that impact nutrition may include, but are not limited to:

• Diabetes mellitus (type 1, type 2, gestational diabetes)

• Coeliac disease

• Renal disease

• Cancer

• Eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder)

• Bariatric surgery (including gastric sleeve, gastric bypass, lap band)

• Thyroid disease (hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism)

• Cardiovascular diseases requiring medication, including ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, warfarin and statins

• Mental health conditions requiring medications

• Gastrointestinal disorders, such as diverticulitis, bowel obstructions, bowel resections, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease).

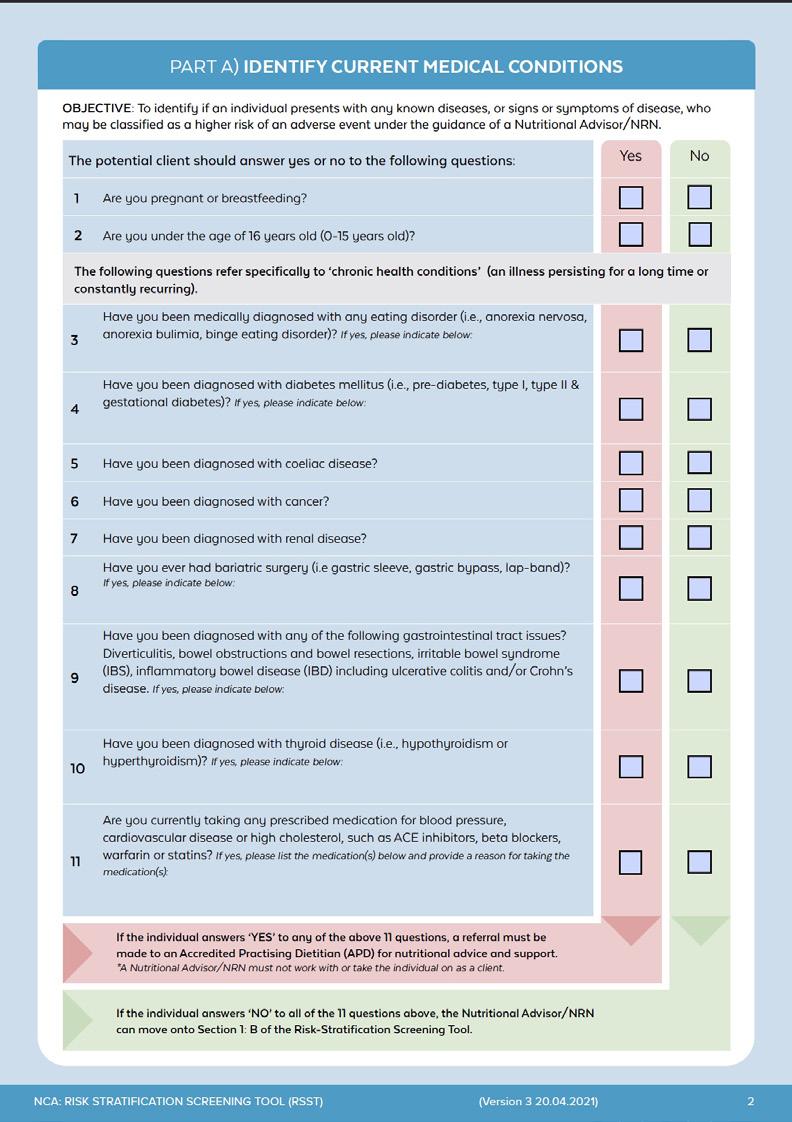

As discussed in the ‘Confirm Physical Health’ unit within the 111046NAT - Certificate IV in Nutrition, screening for ‘at risk’ clients using a Risk Stratification Screening Tool (RSST) identifies which clients are within or outside a nutrition coach’s scope of practice. The screening tool identifies several different areas in the client’s current and genetic health, which may exclude them from being able to consult with a nutrition coach until medically cleared by a GP.

The screening tool is vital as it benefits the nutrition coach and ensures the appropriate care is provided to the client, subsequently allowing for better health and wellbeing.

The RSST will work through the following steps to ensure nutrition coaches practice within their scope of practice.

SECTION 1: IDENTIFY THE CLIENT’S CURRENT HEALTH STATUS

PART A) Identify current medical conditions

PART B) Identify ‘at risk’ factors.

SECTION 2: IDENTIFY POSSIBLE FOOD INTOLERANCES AND/OR ALLERGIES

SECTION 3: IDENTIFY FAMILY HEALTH HISTORY

RISK-STRATIFICATION SCREENING TOOL

To view the Risk-Stratification Screening Tool (RSST) CLICK HERE.

Due to the increased risk and challenges that medical conditions can have on client care, it is critical to identify clients outside the scope of practice of a nutrition coach. Section 1 of the industry-endorsed RSST focuses on identifying the client’s current health status and the need for referral.

There are two components within Section 1 of the RSST that collect vital information about the client; this includes:

PART A) Identify current medical conditions.

PART B) Identify ‘at risk’ factors.

Medical conditions refer to any condition the client has that could impact the support a nutrition coach can offer through the prescription of individualised nutritional plans. Nutrition coaches need to analyse the situation and the client’s information to make a decision based on their scope of practice and any contraindication that may be identified. This decision will also then dictate whether or not the client needs to be referred to a more suitable medical or allied health professional.

Nutrition coaches must be aware of common conditions, health factors and chronic diseases that warrant a referral to an appropriate health professional. Nutrition coaches should always refer to their scope of practice when in doubt of a client’s eligibility.

Any client presenting with the following conditions/contraindications are required to be directly referred to an Accredited Practising Dietitian (APD) for nutritional advice and support:

• Pregnant or breastfeeding

• Individuals under the age of 16 years old (0-15 years)

• Individuals with medical conditions including but not limited to:

• Eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder)

• Diabetes mellitus (pre-diabetes, type 1, type 2 and gestational diabetes)

• Coeliac disease

• Cancer – current diagnosis and/or receiving cancer treatment

• Renal disease

• Bariatric surgery (including gastric sleeve, gastric bypass, lap band)

• Chronic gastrointestinal tract issues, such as diverticulitis, bowel obstructions, bowel resections, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

• Thyroid disease (hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism)

• Prescribed medications for blood pressure, cardiovascular disease and high cholesterol, such as ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, warfarin or statins.

If the client answers ‘yes’ to any of the questions in Section 1: B, this indicates potential risk factors. A referral must be made to a GP for a more detailed assessment, and a medical clearance must be attained. A nutrition coach can work with the client only after a clearance has been granted by the GP.

1. Is your BMI under 18.5 (<18.5)kg/m2 or over 40kg/m2 (>40)?

A BMI below 18.5kg/m2 is classed as underweight, whereas a BMI over 40 is classed as ‘Level 3 Obesity’ (very severe). Underweight and obese clients are often at risk of malnutrition and deranged pathologies such as high/ low blood sugar levels, cholesterol and blood pressure.

It is important to note that BMI is a calculation based on total body weight and total body height. BMI does not take the type of weight (muscle or fat) into consideration and, therefore, may place a client with a high muscle mass level into the obese category. Therefore, the nutrition coach must consider the distribution of total body weight and not draw conclusions based only on weight.

2. Have you been diagnosed with any conditions impacting fertility? For example, polycystic ovarian syndrome and endometriosis.

Fertility conditions can cause changes in hormones, weight and glucose regulation, which can affect a client’s macronutrient and micronutrient requirements.

3. Have you been formally diagnosed with any food allergies and/or intolerances?

Food allergies are an immune-mediated response, and food intolerances are a sensitivity to certain foods that can impact a client’s nutritional intake. Diagnosing allergies and intolerances requires specialised intervention by a GP. Care must be taken to ensure that the offending food is not included in the client’s diet to avoid adverse symptoms such as pain, gastrointestinal upset and difficulties breathing.

4. Have you been formally diagnosed with a mental health condition in which you are required to take medication?

There are many mental health conditions (including depression, ADD/ADHD, anxiety, bipolar and schizophrenia) that require medication as part of their treatment and management. Many of these medications can affect metabolism, weight and nutritional needs, which will affect the effectiveness of a nutritional plan.

The objective of Section 2 is to identify possible food intolerance or allergies that a client may have. This is a key factor in the screening process as this may require a more detailed level of assessment by a qualified Accredited Practising Dietitian (APD).

IF THE CLIENT ANSWERS YES TO TWO OR MORE OF THE FOLLOWING, A REFERRAL TO AN APD IS RECOMMENDED:

1) Do you experience bloating regularly?

2)

3)

4)

5)

Do you believe you suffer from excessive flatulence? (Note: There is no normal amount, but just asking if a client experiences more flatulence than what they consider normal and if the smell is “offensive” provides an initial indication of concern).

Do you experience irregular bowel motions (e.g. diarrhoea, constipation, difficult to pass, abnormal colours, faecal urgency)?

If yes, please provide detail on the number of eliminations per day, stool colour, stool abnormalities and stool formation where possible.

Do you believe you suffer from low energy levels? (Discuss with the client the reason for low energy levels. Unexplained low energy levels may indicate poor nutritional absorption).

Do you suspect you may have any food allergies and/or intolerances?

If yes, please identify why you think you may have an allergy/intolerance and to what specific food.

If the client answers ‘yes’ to two or more of the above questions, it is ‘recommended’, however not mandatory that a referral be made to a general practitioner (GP) for a more detailed assessment and a medical clearance.

*It is at the discretion of both the individual and the nutrition coach as to whether or not nutritional support and guidance will continue under the supervision of the nutrition coach or if the client will be referred to a GP. If the client is happy to continue with nutritional support under the guidance of the nutrition coach, then the nutrition coach can continue to work with the client.

A food allergy is an immediate immune system reaction that affects the body and may potentially be severe or even life-threatening. Allergies are the body’s immune system overreacting to allergens (such as proteins) in foods where they are treated as toxic. Food allergies affect approximately 5% of children and 2% of adults.(4)

The nine most common food allergies are:(5)

1. Eggs

2. Peanuts

3. Soy

4. Milk

5. Wheat

6. Fish

7. Shellfish

8. Tree nut

9. Sesame

Individuals who suffer from food allergies may struggle with any number of the following symptoms: (6)

• Itching, burning, and swelling around the mouth

• Swelling of face or eyes

• Runny nose

• Skin rash (eczema)

• Hives (urticaria - skin becomes red and raised)

• Diarrhoea

• Abdominal cramps/pains

• Breathing difficulties, including wheezing and asthma

• Vomiting

• Nausea.

A food intolerance, on the other hand, is a chemical reaction to a food or drink rather than an immune response.(7) An individual can experience symptoms a few minutes to a few days following ingestion of the offensive food. Typically, consuming small amounts of the food may not trigger an effect in some individuals; however, others may need to avoid the offending food altogether.

Food intolerances may stem from one of several factors, such as:

• The absence of an enzyme required to fully digest a type of food (i.e. lactose intolerance)

• A sensitivity to a type of food or a food additive (gluten intolerance), or

• An existing non-IgE (non-immunoglobulin E) mediated condition such as Coeliac disease.(7)

Individuals who suffer from food intolerances may experience any of the following symptoms:(8)

• Headaches/migraines

• Diarrhoea

• Nervousness

• Tremor

• Sweating

• Palpitations

• Rapid breathing

• Burning sensations on the skin

• Tightness across the face and chest

• Breathing problems (asthma-like symptoms)

• Allergy-like reactions.

If a client identifies as having a food allergy or intolerance, you must obtain a medical clearance from a GP before proceeding with the client.

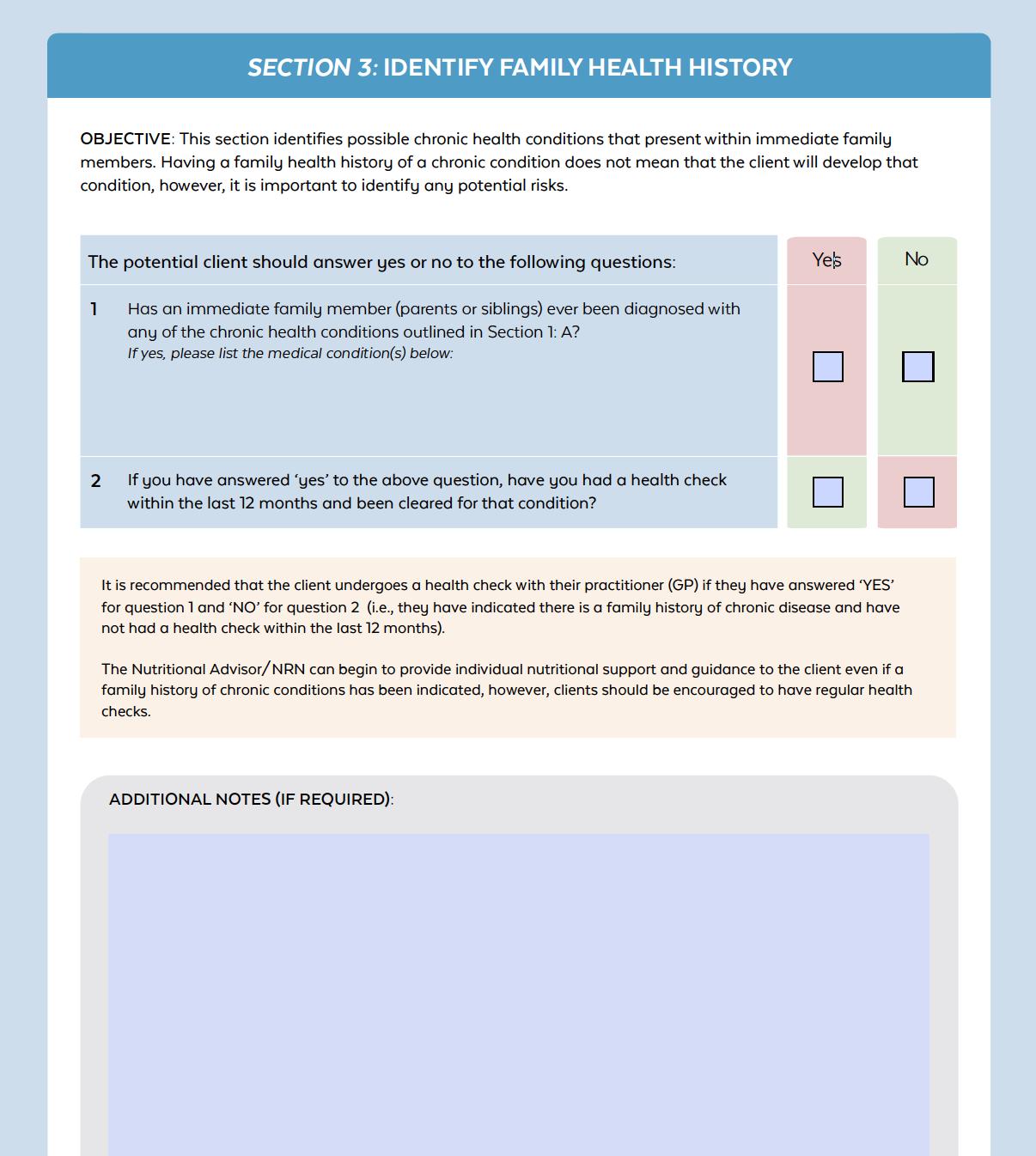

This section identifies chronic health conditions that may present among immediate family members. It enables the nutrition coach to give support and guidance around managing chronic disease risk. The nutrition coach can also use this section to emphasise the importance of regular health checks with a general practitioner (GP).

Has an immediate family member (parents or siblings) ever been diagnosed with any of the chronic health conditions outlined in Section 1: A?

1)

2)

The purpose of question one is to identify any family medical conditions. If the client ticks ‘yes’ to this question, the nutrition coach can take a record of the client’s family medical history. This health information is about a client’s immediate family members, parents and siblings. For example, their mother may have heart disease, or their sister may have gestational diabetes.

It is important to record this information because the client may be at a higher risk of developing chronic disease. For example, a client with a family history of heart disease is more likely to develop that condition compared to a client with no family history of heart disease.

If you have answered ‘yes’ to the above question, have you had a health check within the last 12 months and been cleared for the condition?

The purpose of question two is to find out if the client has had any recent health checks. Generally, it is recommended that any client undergoes a regular health check with a GP. This is particularly important because the client has indicated a family history of chronic disease, and they have not had a health check within the last 12 months.

The nutrition coach can begin to provide individual nutritional support and guidance to the client even if a family history of chronic conditions has been indicated. However, clients should be encouraged to have regular health checks, and nutrition coaches should also monitor for signs of disease.

The depth of knowledge and training/education required to effectively and safely support the previously mentioned out of scope clientele is not sufficiently covered in the training and education of the 11046NAT - Certificate IV in Nutrition. A referral to an appropriate medical or allied health professional (AHP) is required for clinical nutrition-related advice or for any clientele who falls outside of the scope of practice (who are deemed ‘at risk’) for a nutrition coach.

The appropriate health professionals to refer to are as follows:

• Accredited Practising Dietitian (APD)

• Accredited Sports Dietitian

• General practitioner (GP).

Collaborative practice with the appropriate health professional/s is an imperative approach to protect out of scope clientele from unsuitable or potentially detrimental nutritional advice. In turn, this can also prevent the possibility of legal liability linked with providing nutritional advice to such clients. Furthermore, this collaborative approach can improve the industry by growing networks for client referrals and increasing expert credibility and integrity within the health and fitness industry.

More Information can be found using the following links:

Accredited Practising Dietitian: CLICK HERE to view the link.

Accredited Sports Dietition: CLICK HERE to view the link.

It is important to remember that a nutrition coach focuses on providing advice to healthy clients. As discussed in the RSST, there are instances where a nutrition coach is required to take action if a client is at risk of falling outside of the scope of practice of a nutrition coach. Generally, there are two different requirements for a nutrition coach, which are identified in the table below:

REQUIREMENT 1

REFER DIRECTLY TO A MEDICAL OR ALLIED HEALTH PROFESSIONAL

REQUIREMENT 2

If any client is identified in Section 1: Part A of the RSST as ‘high risk’, then a nutrition coach must refer directly to a relevant medical or allied health professional, as they fall out of a nutrition coach’s scope of practice

*This would mean that the nutrition coach cannot work with the client and must refer on.

If any client is identified in Section 1: Part B of the RSST as ‘at risk’, then a nutrition coach must refer the client to a GP for a more detailed assessment and written medical clearance.

SEEK MEDICAL CLEARANCE FROM A GP

If any client is identified as answering ‘yes’ to two or more questions in Section 2 or 3, it is recommended that the nutrition coach refers the client to a GP for a more detailed assessment and medical clearance.

*It is only after a clearance has been made by the GP that a nutrition coach can continue to work with a client.

The table below outlines the roles of necessary health professionals that are relevant in the referral process for nutrition coaches:

Accredited Practising Dietitians (APDs) are university-qualified professionals that undertake ongoing training and education programs to ensure that they are the most up-to-date and credible source of nutrition information. They translate scientific health and nutrition research into practical advice and practice in line with Dietitians Australia’s (DA) Professional Standards.

An Accredited Sports Dietitian is an APD that has undergone further education and training in sports nutrition practice.

A General Practitioner (GP) is a doctor who is also qualified in general medical practice. GPs are often the first point of contact for clients of any age who feel sick or have a health concern. They treat a wide array of medical conditions and health issues.

A GP may also undergo further education in specific areas such as women’s or men’s health, sports medicine or paediatrics.

Refer the client to a GP if they have not had their cholesterol, blood glucose or blood pressure checked in the past 3-6 months.(12) The GP will write a pathology script to check blood glucose and cholesterol levels and check blood pressure in the clinic. If all results are within range, the client can return to the nutrition coach and continue under their care.

Refer the client to an APD if they have any of the listed health conditions in Section 1 or any potential diagnosed food intolerances and/or allergies identified in Section 3 of the Risk Stratification Pre-Screening Tool. The correct dietary support is detrimental in their health outcome.

The role of a psychologist is to assess, diagnose, and treat the psychological problems and the behavioural inhibitions resulting from or related to physical and mental health.(13) A nutrition coach would refer the client to a psychologist when the client is outside their scope of practice and the issues are related to mental health.

Examples of when a nutrition coach would refer a client to a psychologist include:

• Depression

• Anxiety

• Eating disorders (e.g. anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder)

• Negative self-talk

• Indication of self-harm

• Insomnia or severe fatigue

• Very low self-esteem

• Bipolar disorder

• Substance abuse

• Indications of verbal, physical or sexual abuse

• Addictions

• Post-traumatic stress disorder

• Strained relationships.

Refer the client to a personal trainer if they want exercise recommendations in combination with nutritional advice. Personal trainers are equipped to provide exercise recommendations to assist clients with weight loss, body composition and muscle building.

While nutrition coaches can encourage clients to exercise, it is outside their scope of practice to provide individualised exercise recommendations beyond the Australian Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines (unless suitably qualified to do so).

For more information on these guidelines CLICK HERE.

There are several elements that should be documented through the client support process. Initial client records, screening surveys and documents, such as assessment results, should be retained within the client’s record. These records come together to form a ‘client profile’.

Nutrition coaches are advised to collect all relevant information and documents from their clients as this serves two primary purposes:

1. The information collected forms a record for tracking the client’s progress against their nutritional goals

2. The documents and information form a legal record of advice provided.

Whether electronic or hard copy, it is important that each client has an individual record consisting of the following documents, at a minimum:

• The client’s completed Risk Stratification Screening Tool (RSST)

• Pre-screening questionnaires and any assessment results

• Initial consultation notes

• The client’s nutrition plan and/or nutritional recommendations

• Progress records (i.e. monitoring assessment records, follow-up consultation records).

In addition to the above, nutrition coaches may also gain feedback from their clients using feedback forms, surveys or additional documentation. It is also a good idea to collect and store this information for future reference.

When considering how these documents are retained, it is important to remember the requirements of the Australian Privacy Act (1988) governing the retention and management of documentation. The information provided by the client, and that which was gathered during the support process, remains confidential. This means reasonable measures must be taken to secure the information and ensure it is not accessible by others.

Before going into detail on how to develop a nutritional plan, a nutrition coach must understand the body’s primary systems and their functions. Although this has been covered in previous units (such as the unit ‘Confirm Physical Health Status’), revisiting and understanding these systems allows for an appreciation of how nutrients are utilised and processed within the body, identifying where clients may require some modification to their diet and any potential health issues.

As a quick review of previous units within this course, the information below provides a brief summary of each of the body’s main systems:

• Digestive system

• Integumentary system

• Respiratory system

• Circulatory system

• Skeletal system

• Muscular system

• Endocrine system

• Urinary system

• Reproductive system.

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

Breaks down food into components (such as vitamins, minerals and other nutrients) that the body can use for:

• Energy production

• Repair of tissues

• Growth

• Immune function.

• Protects the body from loss of water and abrasions from the outside.

• Movement of air and carbon dioxide through the body

• Gas exchange between air and circulating blood

• Producing sounds heard in communication

• Maintaining respiratory health.

CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

• Carries nutrients, oxygen, carbon dioxide, hormones, antibodies and blood cells to all parts of the body

• Maintains homeostasis and immunity

It can help improve the function and health of a client’s digestive system.

It can help promote healthy hair, skin and nails and efficient wound healing.

It can help maintain energy production, fat burning and help keep the respiratory system functioning correctly by supporting immune health.

It can help maintain healthy blood lipid (cholesterol) levels and blood glucose levels and reduce the likelihood of free radical damage or inflammation to blood vessels and joints.

SKELETAL SYSTEM

MUSCULAR SYSTEM

ENDOCRINE SYSTEM

NERVOUS SYSTEM

URINARY SYSTEM

• Provides support, locomotion, and protection for the body.

• Also produces red blood cells and stores important minerals for the body.

• Production of skeletal movement

• Maintenance of posture and body position

• Support and safeguard exit and entry points of the body

• Support soft tissue

• Store nutrient reserves

• Maintain body temperature, heat, and homeostasis.

• Produces hormones that regulate metabolism, growth and development, reproduction, mood, sleep and sexual function.

• How the body moves communication throughout the body

Plays a crucial role in maintaining the strength and health of the bones.

REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

• Responsible for the removal of waste products from the human body

It can help muscle maintenance, growth and energy for daily work and exercise.

• A system of sex organs which work together for the purpose of reproduction.

It can help support the functioning of the endocrine system by reducing stress on the body, by eliminating undesirable food choices and promoting foods that assist in immune health.

It can help provide sufficient healthy fats for brain health and all the nutrients required for nerve signallings such as sodium and potassium.

Water is an essential component of this system to aid in the excretion of waste products. A well-designed nutrition plan will account for an individual’s fluid requirements to support urinary health by preventing dehydration.

Although it is outside a nutrition coach’s scope of practice to work with pregnant or breastfeeding women, they can still encourage their clients to follow a healthy, well-formulated nutrition plan before conception. A well-designed nutrition plan that promotes appropriate nutritional intake, including adequate amounts of nutrients such as dietary fat, protein, folate, selenium, zinc and vitamin C, supports the formation of healthy sperm andthe development of eggs.

All human body functions require energy, from breathing and the heart beating to exercising and laughing. Everything the body does can only be done through using energy.

Calories and kilojoules (kJ) are both measurement for energy obtained from food, where 1 calorie equals 4.184 kilojoules. (15)

1 calorie = 1 kilocalorie

1 calorie = 4.184 kilojoules (kJ)

1 megajoule (mJ) = 1,000kJ.(15)

The energy required in the body is obtained through food, more specifically, from macronutrients. When broken down during digestion, each macronutrient produces a specific amount of energy per gram. Some macronutrients are more energy-dense than others.

The table below shows how much energy, in the form of kilojoules and calories, is found in each macronutrient and alcohol per gram.

NOTE: FOR SIMPLICITY, KILOJOULES HAVE BEEN ROUNDED TO THE CLOSEST WHOLE NUMBER)(15)

Kilojoules is the standard unit of measurement amongst health professionals and is more well-known in Australia. In Australia, kilojoule’s are commonly used on nutrition labels because it is a metric unit and therefore easier and more accurate to calculate with, given the Australian use of the metric system.(16)

The body requires a certain amount of energy each day to function optimally. It is referred to as energy intake - the daily amount of energy consumed through the diet. Simultaneously, the body uses energy for all physiological functions and all physical activity.

In healthy individuals, if their energy intake is higher than the amount of energy they expend, they will gain weight. Conversely, if a healthy individual’s energy intake is less than the amount they expend, they will lose weight. Energy balance or maintenance, therefore, occurs when an individual’s intake is equivalent to their energy expenditure.

The amount of energy required by each client depends on many factors, including height, age, weight, gender, physical activity levels and metabolic demands. Those factors will be used to calculate and develop clients’ nutritional recommendations or meal plans. Energy requirements are further discussed in the following pages.

When developing a client’s nutritional plan, it is important that the nutrition coach has a sound understanding of the key nutrients contained within foods. Understanding the nutritional value of food allows a nutrition coach to comprehend the basic requirements of each nutrient, which then forms the basis for calculating and creating a nutritional plan.

As this information has been previously covered in an earlier unit for this course, a brief summary of each major nutrient group and its relevance is provided in the section below.

Protein is needed by the body not only for muscle recovery, repair and synthesis but for the structure, function and regulation of the body’s cells and tissues.(17)

Protein is found in both animal and plant-based sources, including:

• Meat (such as chicken, beef, pork, and lamb)

• Fish

• Eggs

• Pulses (such as beans, peas and legumes)

• Nuts and seeds

• Dairy products (such as milk, yoghurt and cheese).

Proteins are made up of chains of smaller chemicals called amino acids. There are approximately 20 different amino acids that are found in food. Amino acids can be classified as those which the body can make (non-essential) and those which the body cannot make and therefore need to be obtained through the diet (essential). Different foods contain different amounts and types of amino acids.(17)

As a nutrition coach, it is important to be aware of the role of protein and further educate clients on how protein is essential for human health and wellbeing.

Humans require protein in regular, moderate quantities to ensure correct bodily function and overall health. A diet lacking in a range of proteins can lead to poor health outcomes, including weakness, fatigue, slowed recovery from exercise and muscle wastage.

Protein is not only an energy-yielding macronutrient, containing 17kJ per gram, but it also has several other significant roles in the human body.(15)

The primary role of protein relates to the structure, function and regulation of the body’s cells and tissues; this includes:

• Tissue repair and production (protein synthesis)

• Hormone production

• Enzyme production

• Immune function

• Energy production.

Protein is found in both animal and plant-based food sources, including meat, fish, eggs, pulses, nuts, seeds and dairy products.

It is important to remember that 100g of food (e.g. 100g of chicken) does not equate to 100g of protein. For example, there is 30g of protein found in approximately 150g red meat, 100g white meat, 150g fish, 5 large eggs or 1L of milk.(17)

Some foods are understandably higher in protein and more bioavailable. Below is a table of common protein foods and the amount of protein found in a 100g serve. It is imperative to note that a food’s protein content is only a portion of the total serve size, not the entire weight of the food. For example, 100g of baked snapper has 26g of protein; therefore, only 26% of the serve is protein.

BIOAVAILABILITY

‘Bioavailability’ refers to the degree to which a substance can be absorbed and utilised by the body.(18) Protein bioavailability is therefore a measure of how well protein is absorbed and utilised in the body. There is an array of factors which will affect a protein’s bioavailability, such as the type and amount of amino acids that are present in the food, the chemical structure of the protein consumed, the amount and effectiveness of an individual’s protein-digesting enzymes and the type of dietary protein sources consumed.

POULTRY

100g chicken breast (skin off/grilled) 31

100g chicken thigh (skin off/grilled)

100g lean sirloin steak (grilled)

100g lean beef mince (raw)

100g lean tenderloin steak (raw)

100g lean tenderloin steak (raw)

100g bacon (middle rasher, lean, fried)

100g lamb leg (boneless, roasted)

100g tuna (in oil, drained)

100g snapper (baked)

100g salmon (grilled)

EGGS

1 egg (whole, large, hard-boiled)

1 egg (white only, large, poached)

100g regular cheddar cheese

100g cottage cheese (low-fat)

100g plain Greek yoghurt (low-fat)

250ml milk (low-fat)

250ml milk (full cream)

NUTS AND SEEDS

100g peanuts (dry roasted, no salt)

100g almonds

100g sunflower seeds (dry roasted, no salt)

100g pumpkin seeds (pepitas, dried)

100g cashews (dry roasted, no salt)

100g walnuts (raw)

100g macadamias (raw)

LEGUMES AND GRAINS

100g kidney beans (raw)

100g chickpeas (raw)

100g soybeans (dry roasted)

100g lentils (boiled)

100g canned baked beans in tomato sauce

100g brown rice (boiled)

100g white rice (boiled)

SUPPLEMENTS

30g scoop whey protein isolate (WPI)

30g whey protein concentrate (WPC)

30g soy protein

100g tofu (firm, hard)

coconut milk

100g coconut yoghurt

Complete proteins are sources of protein that contain all nine essential amino acids, whereas incomplete proteins refer to proteins that do not contain all nine essential amino acids.

The nine essential amino acids that make up a complete protein include:(20)

1. Histidine

2. Lysine

3. Threonine

4. Isoleucine

5. Leucine

6. Methionine

7. Phenylalanine

8. Tryptophan

9. Valine.

The table below discusses the difference between complete and incomplete proteins in more detail:

Proteins that encompass all of the nine essential amino acids are thought of as complete proteins.

Complete proteins are important because they provide the full range of essential amino acids which cannot be produced in the body. Without a regular supply of these amino acids, muscle tissue will be broken down to supply them, which is not ideal for long-term health.

These complete proteins mostly come from animal sources, such as:

• Eggs

• Chicken

• Beef

• Lamb

• Pork.

And some plant sources, such as:

• Quinoa

• Buckwheat

• Soy

• Quorn (a meat substitute made from a fungus).

Proteins that do not contain all nine essential amino acids are considered incomplete proteins.

Plant foods are predominantly incomplete protein sources; however, this does not mean that they are a lowquality protein.

Examples of incomplete proteins include:

• Grains such as rice, pasta and bread (lack/low in threonine, leucine, lysine and histidine)

• Legumes such as beans, peas and lentils (low in methionine)

• Starchy vegetables such as potato, pumpkin and sweet potato (low in lysine)

• Nuts such as walnuts, macadamia and almonds (low in threonine).

Simply because a type of protein is incomplete does not make it inferior. Incomplete proteins can be combined to form the full range of essential amino acids to create a complete protein. Someone following a vegetarian or vegan diet should consider doing this to ensure they are consuming all of the essential amino acids in their diet, especially if they are exercising regularly.

A further benefit of combining plant-based foods in the diet (to achieve a complete range of essential amino acids) is the other nutrients accompanying them, including fibre, vitamins and minerals (which will be covered later in this resource).

To do this, two plant foods with varying amino acid profiles must be combined, for instance, grains with vegetables. Proteins combined to make a complete amino acid profile (containing all the nine essential amino acids) are known as complementary proteins, after which they can then be classified as a complete protein.(21)

Examples of complementary proteins include (but are not limited to):

• Spinach salad with almonds

• Hummus and whole-grain pita bread

• Navy beans (baked beans) on wholemeal toast

• Natural peanut butter wholemeal sandwich

• Black beans with rice (white or brown)

• Tofu with rice (white or brown)

• Macaroni and cheese.

Complementary proteins do not necessarily need to be eaten together; however, since the body has limited capacity for storing amino acids, they should be eaten throughout the day.(21)

Many myths about protein circulate in the community, especially in health and fitness. Below are some evidence-based facts to disprove common myths:

The body can only absorb and use 25g of protein in one meal.

Excess protein will turn to fat if not used by the body.

The body will absorb all protein from a meal, but how much protein it uses is demand-driven; for instance, a bodybuilder will likely require and use more protein than a sedentary, untrained office worker because the body of the former has a higher requirement for muscle repair and growth.

The human body cannot store excess protein or amino acids. Unneeded amino acids get broken down by the liver and removed by the kidneys. In saying that, if a client is exceeding their EER, excess energy from any macronutrient source (including protein) will be stored as fat.(21)

Consuming a high protein diet can cause kidney damage.

It is best to consume protein within 30 minutes of finishing a resistance workout

Consumption of excess protein will result in muscle gain even if a client does not participate in any physical activity.

Protein is only needed for those who exercise regularly or want to put on muscle mass.

Protein shakes (i.e. whey protein) are the only source of protein that should be consumed after a workout

Recent scientific reviews of protein dosing and health have confirmed the safety of high protein diets in adults with healthy kidneys and no history of kidney disease.(21) However, there has been very little proven benefit in increasing protein intake above the EPR.(21) Protein needs will vary depending on activity level, gender and age. As such, it is important to remain within the recommended EPR ranges for each individual to meet their goals and avoid compromising intake of other important nutrients.

Consuming protein is recommended within 2 hours of resistance training to promote immediate muscle recovery, but protein demand can be elevated for up to 24-48 hours. So regular dosing of protein every 3-4 hours is recommended.(21)

Without sufficient physical stimulus (e.g. resistance training), the excess protein will be excreted from the body, and muscles will not grow. Amino acids help repair muscle tissue after exercise, increasing muscle growth.(21)

Adequate protein is essential for growth, repair, hormone and enzyme production, and overall health throughout the lifespan, regardless of lifestyle; it is needed for all biological processes daily and is essential for optimal health, even in individuals who do not exercise.

Protein shakes and other protein supplements are convenient and can be quickly absorbed after a workout. However, it is best to prioritise wholefood protein sources over supplements to meet the body’s protein needs, as they include various other beneficial nutrients like fibre, vitamins and minerals.

• Proteins are commonly referred to as the ‘building blocks of life’, signifying their importance in the human body.

• Proteins are nitrogen-containing substances that are digested/broken down into amino acids.

• Proteins are utilised to produce new tissues for growth and repair and to regulate and maintain body functions; they also aid in producing essential hormones and are fundamental for the digestive system and immunity enzymes.

• There are 500 known amino acids, 20 of which humans need. Of these 20, there are nine essential amino acids.

• Most health organisations recommend a protein RDI of 0.8-1.0g per kg of body weight per day; however, this recommendation can increase depending on physical activity levels, disease states, trauma and stress levels.

• Protein can be found in various foods, including animal and plant sources. The quality and bioavailability of the protein change from food to food, generally with animal-based protein containing more complete and bioavailable protein than plant-based proteins.

• A complete protein refers to a source of protein that contains all nine of the essential amino acids.

Carbohydrates (also known as saccharides or ‘carbs’) are organic compounds made up of sugars or starches. The body utilises this macronutrient as an immediate source of energy. Carbohydrates are a major food source and a key form of energy for most organisms. One gram of carbohydrate provides approximately 17kJ of energy.(15)

Regardless of origin, all carbohydrates are broken down in the body into a simple sugar, depending on their source and structure. These are most commonly glucose (honey), fructose (from fruit) and galactose (from dairy).(22)(23)

Certain parts of the carbohydrate (such as starch and fibre) slow the release of sugar into the bloodstream, resulting in increased satiety, improved gut flora (by acting as a prebiotic) and regulated bowel motions. While the body breaks down starch into simple sugars, fibre passes through relatively undigested. The fact that fibre is not broken down does not void its importance in the human diet as it dramatically benefits bowel motions, gut flora and satiety.

The Australian Government recommends carbohydrate intake to be approximately 45-65% of the diet, with the focus primarily on low GI carbs. It is important to keep in mind the type of client you’re working with, what their goals are, and their need for carbohydrates when determining where in this range they will sit.(22)(15)

As a nutrition coach, it is important to understand the role carbohydrates play in the human body to assist with individualised macronutrient recommendations.

Carbohydrates have three fundamental roles in the human body, including(24)(25)(23):

• Provide the body with an immediate fuel supply

• Provide the body with stored energy

• Assist with digestive health and disease prevention.

Carbohydrates, regardless of their origin, are broken down into their most simple form and utilised as energy for the body. Carbohydrates can be utilised as an immediate source of energy. As soon as sugar enters the bloodstream, it can be used by cells around the body that require energy to carry out any number of tasks.

Carbohydrates are especially beneficial as an immediate fuel supply for athletes completing longer distance or higher intensity events, such as marathon running or competitive rowing.

When more carbohydrates are consumed than burned, excess carbohydrates are converted to fatty acids and stored as fat. When fat is required for energy, fat is converted back to glucose through a process known as gluconeogenesis, and that glucose is then used for energy. This type of energy can be used at a later stage when there is no immediate supply of blood glucose.

The fibrous component of carbohydrates (discussed later in resource) has several important roles. These roles include:

• Feeding gut bacteria

• Regulating bowel motions

• Optimising cholesterol levels

• Regulating sugar levels

• Decreasing risk of bowel disease.

Carbohydrates can be divided into two main categories:

1. Simple carbohydrates

2. Complex carbohydrates.

MONOSACCHARIDES (one sugar molecule)

DISACCHARIDES (two sugar molecule)

OLIGOSACCHARIDES (three to nine sugar molecule)

POLYSACCHARIDES (ten or more sugar molecules) GLUCOSE SUCROSE RAFFINOSE STARCH FRUCTOSE LACTOSE STACHYOSE GYCOGEN

GALACTOSE MALTOSE CELLULOSE

The terms simple and complex refer to the complexity and length of the carbohydrate in question. Generally, the more complex a carbohydrate is, the greater the amount of fibre the food source contains.

Fibre is a dietary material resistant to the action of digestive enzymes(23). This means that the body does not break down fibre, and it passes through the gastrointestinal tract relatively intact. As mentioned above, fibre helps regulate bowel motions, slow the breakdown of carbohydrates and increase satiety(23). Examples of fibre in dietary sources include the husk of nuts and seeds and the skin on fruit and vegetables. Dietary fibre will be discussed in greater detail later in this unit.

Simple carbohydrates refer to carbohydrate-rich foods which are less complex, have minimal/less dietary fibre, and are therefore more rapidly broken down within the body. This results in a quicker release of sugar in the bloodstream and a faster supply of immediate energy. Examples of simple carbohydrates are foods that have been processed or refined, such as fruit juice, lollies and sugary cereals.

Simple carbohydrates are quicker to break down in the body than complex carbohydrates because they are shorter in length.

Simple carbohydrates include:(23)

• Monosaccharides (one sugar molecule in length)

• Disaccharides (two monosaccharides joined together).

Complex carbohydrates refer to sugar molecules that are strung together in long, complex chains. Due to the length of the chain and the fibrous and starchy components of the carbohydrate, complex carbohydrates take longer for the body to break down. As a result, complex carbohydrates have a slower release of glucose into the bloodstream. This is beneficial in assisting with satiety, cravings and energy levels.

Examples of complex carbohydrates are carbohydrate-rich foods in their most natural form, such as:(23)

• Sweet potatoes

• Quinoa

• Couscous

• 100% whole wheat pasta

• Peas

• Beans (e.g. kidney beans, cannellini beans, butter beans)

• Lentils

• Pumpkin.

These foods are a source of carbohydrates, however still contain their natural dietary fibres (such as the skin, seeds and husk) and starches.

There are a number of dietary myths encompassing carbohydrates which can confuse the general public. Below are some evidence-based facts to disprove common myths:

It is fine for clients to consume as much carbohydrate as they please, provided it comes from an unprocessed food item.

Table sugar alternatives are healthier for the human body and can therefore be consumed without limit.

Only bread and pasta contain carbohydrates.

Carbohydrates make you gain weight.

Carbohydrates are not needed in the diet, as the body creates its own glucose.

While an unprocessed carbohydrate, such as an apple, is more beneficial to human health than a processed carbohydrate, such as apple juice, the intake of excess (natural) sugar can still adversely affect health, increasing the risk of:(22)

• High blood pressure

• Type 2 diabetes

• Heart disease

While alternatives to table sugar, such as dried fruit or natural honey, are healthier due to their increased nutrient profiles (fibre, vitamins, minerals, antibacterial properties), their consumption should still be limited. While they may not spike blood glucose levels compared to refined sugars they are still high in kilojoules and sugar, which can be detrimental to health.

Carbohydrates are found in several other different dietary sources, such as:

• Fruit

• Vegetables

• Dairy products

• Oats

• Beans

Excess energy intake from any energy-yielding macronutrient (including protein and fat) will cause weight gain – not specifically carbohydrates. If consuming carbohydrates as part of a well-balanced diet that meets energy needs, weight gain will not occur. Where possible, preference should be given for more complex, lower GI and higher fibre sources of carbohydrates, such as wholegrains, legumes and starchy vegetables.(26)

These sources have an improved effect on satiety, bowel function and gut health.(26) Excess sugar or highly refined carbohydrates, such as soft drinks, white breads, lollies, chocolate should be limited, to optimise health outcomes.

In times of starvation, the body can produce its own glucose through a process known as gluconeogenesis. However, this can negatively impact on the body’s protein and fat stores. Carbohydrates are essential for a healthy functioning body and should be included in the diet on a daily basis. Little research supports the use of low carbohydrate diets in the long term, as any weight loss is often regained, any improvement in blood lipids and glucose levels are not maintained and highly energy-dense fatty foods, particularly those high in saturated fats, can cause dysbiosis in the gut and low-grade chronic inflammation.(27)

As with any macronutrient, quality and quantity can impact on their usefulness in the body. Preference should be towards high fibre, low GI carbohydrates with small amounts of added sugars.

• Carbohydrates (also known as saccharides or ‘carbs’) are organic compounds made up of sugars and utilised by the body as an instant energy source.

• One gram of carbohydrate provides approximately 17kJ of energy.

• Carbohydrates have three fundamental roles in the human body, including providing the body with an immediate fuel supply, storing energy, and assisting with digestive health.

• All carbohydrates are made of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen with the general formula of CH2O.

• Carbohydrates consist of two main types - complex carbohydrates and simple carbohydrates. Simple carbohydrates include monosaccharides and disaccharides, and complex carbohydrates include oligosaccharides and polysaccharides.

• Carbohydrates come in many forms, predominantly in fruits, vegetables and grain-based products. It can also be sourced from dairy products and foods that have been formulated with added sugar.

• Natural sugars, also known as natural carbohydrates, are sugars that are found in unprocessed foods, such as fruit, vegetables, dairy and grains.

• Refined sugars, also known as processed sugars, processed carbohydrates or refined carbohydrates, are forms of sugars that have been altered or processed in some way and are no longer in their natural state.

• Excess sugar intake can be detrimental to an individual’s health, increasing their risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Dietary fat, although once portrayed in a negative light, is an essential part of the human diet. Fat not only provides an energy source for the body but also plays an important role in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, production of hormones, improving satiety and improving cognitive function.(23)

Dietary fats are a class of macronutrients essential in the human diet. All living tissues contain some form of fat (or lipids as they are scientifically called).

The main types of dietary fats are:(23)

• Saturated fats

• Unsaturated fats (monounsaturated and polyunsaturated)

• Trans fats.

Dietary fats should not be confused with body fat and the fats used in the body. Once dietary fat is digested, it is broken down into fatty acids and then repackaged into other useful types of fat, such as:(23)

• Phospholipids (used for cell walls)

• Cholesterol (used for cell walls, hormone production and fat-soluble vitamin production)

• Free fatty acids (used to build other fats)

• Triglycerides (used to store fat in adipose tissue).

As a nutrition coach, it is important to be aware of the role of fatty acids and educate clients on how dietary fat is essential for human health and wellbeing. Humans require dietary fats in regular, moderate quantities to ensure correct bodily function and overall health.

Dietary fat is not only an energy-yielding macronutrient, containing 38kJ (15)per gram, but it also plays several other very important roles in the human body.

The primary role of fat relates to the structure of all cells, as well as:(28)

• Helps with the regulation of hunger

• Provides the body with energy and stored energy

• Is critical for normal nerve function

• Stores some vitamins

• Maintains healthy cholesterol levels

• Forms the outer structure of all cells

• Contributes to healthy glowing hair, healthy skin and strong nails

• Improves brain function and brain development

• Improves efficiency and effectiveness of blood clotting when/if required

• Assists in reducing inflammation and increasing immunity

• Reduces cardiovascular disease risk

• Improves blood vessel elasticity

• Production and regulation of some hormones

• Decreases the risk of depression and anxiety.

In extreme cases, vitamin deficiencies caused by a significant lack of dietary fats can lead to weak and brittle bones (vitamin D deficiency), night blindness (vitamin A deficiency) and the inability of blood to clot effectively (vitamin K deficiency).(29)

The factors in the previous list are discussed in more detail in the following table.

The mechanism by which dietary fat helps to regulate hunger is still not completely understood. Many hormones in the body regulate hunger and fullness (satiety). Research has shown that dietary fat, and the composition of a meal, are important factors in achieving satisfaction and fullness after a meal.(23)

Dietary fat is used for instant energy production as well as being stored for use later in adipose (fat) cells.

Depending on energy balance (the amount of energy available in the body) and the demands of oxygen, the body’s cells determine whether energy production will come from fat or glycogen (stored glucose). For example, because energy production from fat requires oxygen, burning fat for energy only occurs in the aerobic system. This means that fat burning mainly occurs at rest and at low to moderate levels of exertion.(23)

Energy production from glycogen (glucose) does not require oxygen and can therefore occur in the anaerobic system during intense exercise (sprinting or strength training).

Nerve cells in the brain are coated with a special coating called a ‘myelin sheath’, which allows signals to pass through them very quickly. The myelin sheath (shown in the image below) is made from phospholipids, cholesterol (types of lipid), and proteins, which protect the nerve from damage and help increase the conduction speed of signals within the brain to the extremities.(30)

If nerve cells become damaged or are not repaired properly, over time, this can lead to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Multiple Sclerosis is a disease of the myelin sheath that can cause blurred vision, difficulty walking, muscle weakness and tremors (uncontrolled shaking).(30)

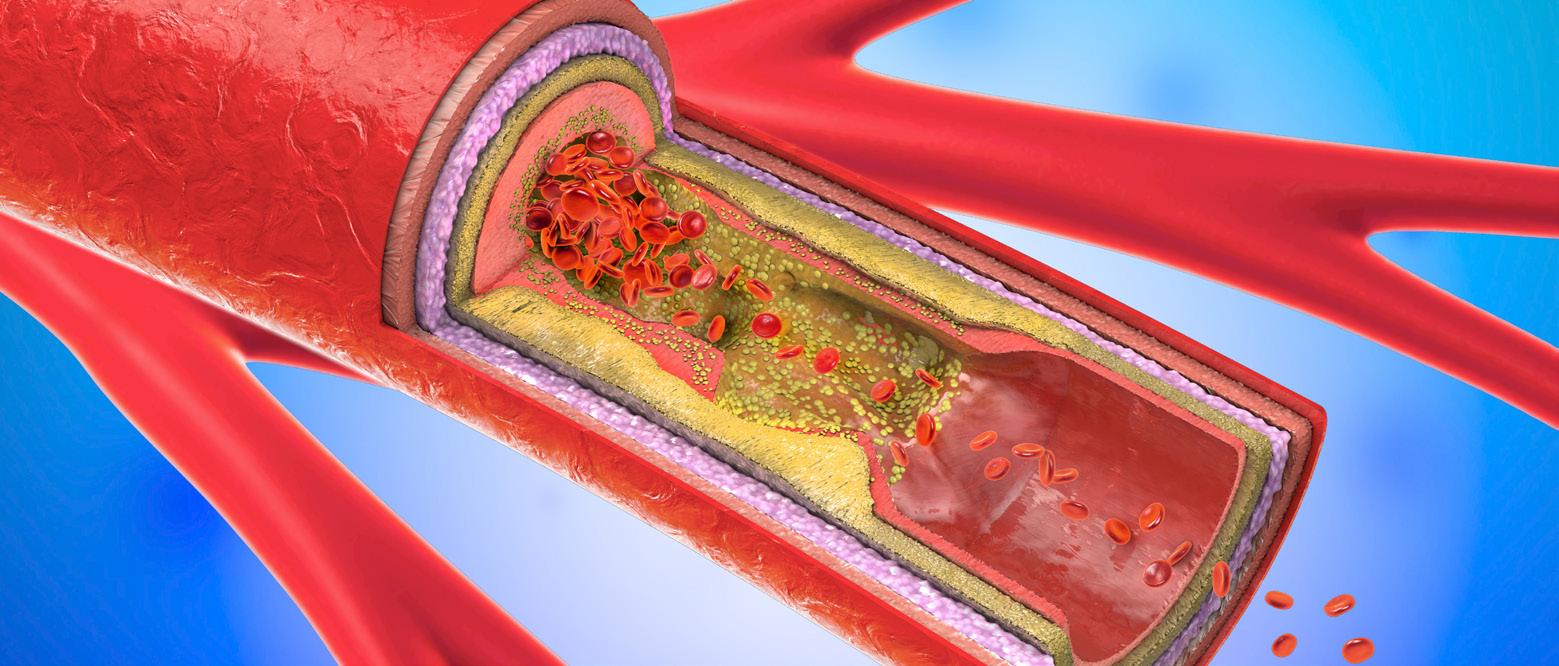

Cholesterol is a form of fat produced by the liver and eaten in the diet which is used for three main roles in the body:(23)

• Aids in the production of sex hormones

• Used for the production of human tissues such as cell membranes

• Used for bile production in the liver.

Cholesterol is transported in the body by lipoproteins. Lipoproteins are transport molecules that pick up, transport and drop off cholesterol wherever it is needed. Maintaining a healthy ratio of cholesterol is important in reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

There are many types of lipoprotein; however, the most important ones are:

• Low-density lipoproteins (LDL)

• High-density lipoproteins (HDL).

Lipoproteins transport many molecules and nutrients around the body, including:

• Cholesterol

• Fat-soluble vitamins (Vitamin A, D, E and K)

• Triglycerides.

This is an important role because without HDL transport, triglycerides can build up in the bloodstream, increasing the risk of atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). Without LDL transport, cholesterol would not get transported to tissues that need it.(31)

Lipoproteins are transport molecules made of protein and fat which carry fats (such as triglycerides) to and from the liver.(31)

The human body is composed of cells; each type of cell has an explicit structure and function and contains all the machinery needed to help the body function properly.

Cells have walls, called a ‘lipid bilayer’, which means that it has two (bi) rows (layer) of fats arranged so that they can keep certain molecules outside or inside the cell (see imagebelow).(32)

The bilayer is composed of a type of lipid called ’phospholipids’ made from saturated and unsaturated fats taken from the diet. The phospholipids are arranged into the cell membrane and form a ‘hydrophobic’ layer, meaning that the outer layer repels water.(32)

CELL STRUCTURE

This is important because it prevents unwanted molecules from penetrating the cell, giving the cell ‘selective permeability’ (control over what can enter).(31)

One type of dietary fat, called omega-3 polyunsaturated fat, is known to help with skin and hair growth. Eating too little may impact the body’s ability to produce healthy skin and hair. Especially as a deficiency in vitamin A, which relies on fat for absorption, can result in skin complaints.

Omega-3 fatty acids are also known to assist with the production of healthy nails by reducing inflammation in the nail bed, which promotes stronger nails.

While all dietary fats are encouraged as part of a varied and healthy diet, some fats are essential because the body cannot create them. These fats are identified as Essential Fatty Acids (EFAs), and will be explored in more detail further in this resource.

Dietary fat is extremely important for the development and healthy function of the brain.

Studies have shown that polyunsaturated fats help with the development of infants’ brains during pregnancy and can help improve:

• Intelligence

• Communication and social skills

• Reduce behavioural problems

• Reduce the risk of developmental delays

BRAIN FUNCTION AND BRAIN DEVELOPMENT

ASSIST IN PREVENTING BLOOD CLOTS

• Reduce the risk of autism and cerebral palsy.(31)

Dietary fats also help reduce ageing-related mental decline and Alzheimer’s disease in older adults, thanks to the anti-inflammatory properties of omega-3 fatty acids.(31)

The brain is composed of almost 60% fat and is the ‘fattiest’ organ in the body!(33) This is why nutrition coaches need to encourage clients to eat a diet that provides adequate sources of good fats and not strictly to limit them.

The polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids can help prevent unwanted blood clotting by preventing platelets (small particles of blood that form clots) from clumping together.(23)

Omega-6 fatty acids are known to promote blood clotting, so a nutrition coach needs to understand the best ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids required in the diet to promote healthy blood clotting.(23)

REDUCE CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE RISK

Some fats are known to be -healthy, meaning they can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease (such as heart attacks, stroke and high blood pressure), when included as part of a healthy diet.

These fats are called polyunsaturated fats which include the omega-3 fat linolenic acid and the omega-6 fat linoleic acid.(23)

INFLAMMATION AND IMMUNE FUNCTION

Inflammation is considered to be a normal immune system response to something that might be harmful to the body, such as itchy and red skin because of a bee sting.

When the body detects something potentially harmful in the body, special white blood cells called ‘leukocytes’ rush to the location and attempt to neutralise the threat.(33)

The main immune responses are:(34)

• Heat

• Pain

• Redness

• Swelling

• Loss of function.

Low-level, ongoing inflammation has been proposed to be the cause of many diseases such as:(33)

• Diabetes

• Obesity

• Cardiovascular disease

• Arthritis

• Allergies (asthma, dust allergies).

Some fats, like mono and polyunsaturated fats, help produce prostaglandins (hormone-like substances) which help reduce inflammation. Conversely, some fats like omega6 fatty acids can increase inflammation when consumed in large quantities in the diet. It is important to learn about these fats, where they come from and the best ratio to consume them to prevent or reduce inflammation and promote a healthy body for clients.(33)

As explained above, inflammation is an immune response to a potential threat. In the case of an allergy, it is an overreaction by the immune system. In the case of arthritis, it is possible that a high intake of omega-6 fats may be the cause(33). By analysing a client’s dietary intake, it may be possible to identify the cause of ongoing inflammation and make recommendations to help reduce it.

Some hormones, called steroid hormones, are made from fats in the form of cholesterol.

Dietary fats are essential for the production of these hormones, and examples include:(23)

• Testosterone

THE PRODUCTION AND REGULATION OF SOME HORMONES

• Progesterone

• Cortisol

• Aldosterone

• Vitamin D.

‘Steroid hormones’ refer to sex hormones including testosterone and progesterone and corticosteroids (which work in the brain) including cortisol (stress hormone) and aldosterone (which regulates water balance).(23)

IMPROVES BLOOD VESSEL ELASTICITY

As individuals age, their blood vessels become stiffened, known as hardening of the arteries.

Long-term supplementation with polyunsaturated fats, like fish oil, has been shown to reduce the hardening of the arteries by reducing inflammation, blood clotting and blood vessel constriction (tightening).(23)

Intake of polyunsaturated fats has been linked with improvements in mental health in scientific studies. A dietary pattern like the Mediterranean Diet may help reduce unwanted symptoms of depression and anxiety.(35)

Researchers have proposed that people with depression may not have enough of the omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA (these are explained below). In some studies, it was shown that supplementation with omega-3 reduced depression symptoms in some participants.(35)

DECREASES THE RISK OF DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY

The mechanism by which omega-3 helps reduce depression is not currently understood. It could be due to anti-inflammatory effect in the brain or the effect Omega-3 has on serotonin (sometimes called the ‘happy chemical’) or the serotonin receptors in the brain.

It is important for nutrition coaches to remember that clients with depression and anxiety should be encouraged to speak to their GP for assessment and appropriate care.

A diet lacking a range of dietary fats can lead to poor health outcomes, including:(23)

• Vitamin deficiency

• Hormone imbalances

• Increased hunger

• Skin problems.

The classification of fat will depend on the structure of its chemical makeup. The nutrition coach needs to be able to identify fats, and their effects in the body and on overall health.

There are two ways in which fats can be classified:

1. By their degree of ‘saturation’: Saturated, Unsaturated, Trans fats.

2. By their ‘length’: Short Chain Triglycerides, Medium Chain Triglycerides, Long Chain Triglycerides.

FATTY ACIDS

Saturated fats from healthy sources, such as eggs, dairy and some meats, are natural fats and are encouraged to be consumed as part of a healthy diet. However, saturated fats from processed foods, such as pies and some meats, are not as healthy and should be limited in the diet.

Saturated fats are typically found in animal products, as well as some plant-based foods, such as:

• Animal fats (lard, tallow, ghee)

• Full cream dairy products (cream, yoghurt, cheese)

• Coconut products (coconut oil, coconut milk and cream).

Some examples of the less healthy, highly processed sources of saturated fats include:

• Processed foods (biscuits, cakes, pastries, pies, chips)

• Processed meats (sausages, salami)

• Fast food (hot dogs, burgers, pizza, fried food).

As a nutrition coach, it is important to promote healthy options for saturated fats because of the effect that they can have on cardiovascular health. Saturated fats, like those found in full cream dairy products (milk, cream, yoghurt), are composed of mainly short-chain fatty acids and appear to have a beneficial effect on gut health by feeding the gut bacteria.

Other saturated fats appear to promote HDL cholesterol which are known to be cardio (heart) protective in the correct ratio (to LDL cholesterol). However, the source of saturated fats is important; processed foods, fatty meats and fast food should be limited within the diet as they can promote an unhealthy ratio of HDL to LDL cholesterol. This is especially important because combining these saturated fats with refined and processed carbohydrates can negatively affect cholesterol levels.(31)

Saturated fat used to be classed as a ‘bad’ fat following the research findings from Dr Ancel Keys from his Seven Countries Study, released in the 1950s, which suggested that saturated fat intake increased the risk of heart disease.

Since this time, however, it has been found that this particular research had data from 22 countries (as opposed to the initially identified seven countries) and when all 22 countries are considered, it is very difficult to find an association between saturated fat intake and heart disease. There is strong evidence to support the claim that saturated fat, while not cardio (heart) protective, is not harmful to human health at intakes around 10% of total daily energy intake.(36)

Unsaturated fats are comprised of one or more double bonds in their biochemical structure and are liquid at room temperature. Unsaturated fats are well known to help reduce the buildup of cholesterol in the arteries, thus declining the risk of heart disease and stroke.(37)

Unsaturated fats can also be beneficial for:(38)

• Improving/reducing inflammation

• Improving the function of blood vessels

• Assisting in reducing triglycerides implicated in atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries)

• Stabilising heart rhythms

• Building stronger cell membranes in the body

• Reducing blood pressure in those with hypertension

• Assisting those with type 2 diabetes

• Assisting in the maintenance of bodyweight.

For this reason, unsaturated fats have often been called the ‘good’ fats as they are beneficial in reducing the risk of disease. However, as previously mentioned, it is important to note that this does not make saturated fats ‘bad’ as they too have a role to play within the body, and often come packaged in nutrient-dense food sources such as meat and dairy.

As unsaturated fats have a double bond they are not as stable for cooking at higher temperatures when compared to saturated fats. When unsaturated fats are used for cooking at high temperatures their biochemical structure can change making it a harmful fat instead of a beneficial fat.

As unsaturated fats have a double bond they are not as stable for cooking at higher temperatures when compared to saturated fats. When unsaturated fats are used for cooking at high temperatures their biochemical structure can change making it a harmful fat instead of a beneficial fat.

There are two major types of unsaturated fat:

1. Monounsaturated

2. Polyunsaturated.

Monounsaturated fatty acids, commonly abbreviated as MUFAs, have one double bond in their biochemical structure. There are many types of MUFAs, the most common ones being oleic acid, palmitoleic acid and vaccenic acid.

Mono-unsaturated fats may have some benefits when included in the diet, such as:

• Reduction in cardiovascular disease risk (thanks to their effect on HDL/LDL cholesterol levels), and

• May help reduce inflammation (this effect was demonstrated in a study where saturated fat was replaced with monounsaturated fat).

Monounsaturated fats can be found in plant-based foods, as well as in meat and animal-based foods. The table below offers a list of food sources high in MUFAs, along with the amount found in (100 grams) of the food source: