WRITING PORTOFOLIO

Fatimatuz Zahroh

Selected Works 2019-2022

Fatimatuz Zahroh

Selected Works 2019-2022

+6282143555145

ftm.zahroh@gmail.com

Fatimatuz Zahroh

Fatimatuz Zahroh

I am a Bachelor from the architecture department of UPN "Veteran" East Java. I am always interested in researching and brainstorming, and I consider myself to be a very curious, passionate, and goal-oriented person. I am very enthusiastic about history, culture, natural and social sciences and their relationship with architecture.

Secondary School (2015-2018)

SMA Negeri 1 Sidoarjo

Bachelor’s Degree (2018-2022)

Universitas Pembangunan Nasional

“Veteran” Jawa Timur

IPK: 3.68/4.00

Skills

Writing and editing

Researching and fact-checking

Photoshop and InDesign

MS Word and Powerpoint

Content Writing

Article Writing

Scientific Writing

Native Languages : Indonesian, Javanese

Intermediate : English

IELTS 7.0

HIMARSTEK Widyastana UPN V JATIM

Staff of Biwastu: Architectural Magazine

Architecture Laboratory UPN V JATIM

Architecture History and Theory Laboratory

As part of Biwastu Architectural Magazine Vol. 5, with the bigger theme about "Hope in a Pandemic", I had to write a theme related to that as a reporter. So I wrote this article as part to inform people about the resilience of traditional tribes in Indonesia when facing the pandemic situation.

Link to Article

The corona pandemic, also known as COVID-19, is already in its tenth month. It has entered the second wave of instances in some industrialized European countries. However, the problems have not subsided in Indonesia and continue to worsen. Google has logged 467,000 cases, with 392,000 people surviving and 15,211 dying. The pandemic has struck Jakarta the most, with East Java coming in second and West Java coming in third. This pandemic has certainly devastated all aspects of life, from education and government to the economy; massive layoffs in various regions, the government's lack of preparedness in responding to cases, and a relaxed attitude that exacerbated the spread of patients; to the polemic of university tuition fees that must be paid in full even if campus facilities are not used. Many questions must be raised concerning the pandemic response actions conducted by government and bureaucratic holders at all levels.

This pandemic has resulted in profound social changes. Some community members, for example, see the usage of masks as a violation of freedom and repressive measures by the authorities (Scheid, 2020). When in fact, donning this mask is one of the transmission-prevention methods. This pandemic is unprecedented in the twenty-first century, and many segments of society are unprepared and looking for measures to limit transmission.

Source: covid19..go.id

Indigenous peoples are one group of people vulnerable to the transmission of COVID-19 (BBC Indonesia, 2020). The main factor is the challenging geographical conditions and the government's lack of health facilities. Butet Manurung, an activist for the rights of the Orang Rimba tribe, believes that as indigenous people become more reliant on the outside world, they will become more vulnerable. So it would be preferable if the jungle community could be more self-sufficient and apply lessons from earlier pandemic episodes.

Architecturally, there may have been many talks and explanations that highlight features of the tropicality of traditional dwellings, as well as how COVID-19 is handled on a domestic size. As is well known from numerous occurrences in Indonesia, many health workers are exposed to COVID-19, one of which is working in a room with artificial ventilation that does not allow viruses to escape. as well as other scenarios in modern structures when artificial ventilation is required.

Apart from components of traditional house construction that aid with COVID-19 handling, several other elements have formed part of the collective memory of several indigenous communities in dealing with the epidemic, including:

The Orang Rimba tribe's equivalent of social distance is besesandingon. It has long been practiced by the Orang Rimba in Jambi, even before the coronavirus outbreak, and is often done to halt infectious diseases. Survivors must isolate themselves for several days in this technique, according to Orang Rimba tribe Indigenous rights campaigner Saur Marlina Manurung. The separation of sick individuals is referred to as disesandingko, or segregated, by the Orang Rimba. They are not permitted to mix

with healthy people. This practice applies to the Orang Rimba and those from outside who visit the Orang Rimba living region. They will be separated from healthy persons even across a 50-meter distance. Typically, sick people are placed downstream of the river, while healthy people remain upstream so that the water utilized by the suffering people does not flow to those who are healthy. According to Saur Marlina Manurung, everyone lives near the river in the jungle, and there is a concept of upstream and downstream. As a result, newcomers must first settle in the downstream region.

The Baduy tribe of Banten is one of the few remaining Javanese tribes with live traditions. One of them is to continue coexisting with the natural environment. This lifestyle can be applied in a variety of ways, including:

The cultivation custom was carried out to support the Baduy tribe's diet

As we know from numerous webinars and news reports, cities are in a terrible situation during this pandemic. The food distribution network has been disconnected due to challenging mobilization with its different health procedures, particularly during regional lockdowns. This problem can be overcome more swiftly in the middle and upper classes than in the middle and lower classes, whose livelihoods are threatened by work-fromhome rules and their incapacity to absorb the financial cost of living. People have food reserves and can limit the usage of food production by consuming a small portion and saving the remainder in their granaries thanks to this practice.

Rimba tribe children eating harvested fruit Source: mongabay.co.id A man from the Orang Rimba tribe in front of his temporary residence Source: mongabay.co.idIn the Baduy community, it is forbidden to construct structures with modern tools and objects. They use natural resources such as wood for the pole, bamboo for the wall, and kiray or palm fiber for the roof. The endeavor is to reduce the probability of the virus entering and infecting Baduy people by cutting off access to the outside world.

The forest serves as a fortress against the outer world

For indigenous people, the forest is a living pharmacy; many medicinal plants or plants, in general, can cure common diseases without needing a hospital or pharmacy. The forest in Baduy traditional village is separated into three sections: leweung kolot (ancient forest), leweung reuma (field forest), and leweung lembur (village forest). The forest is classified into three groups based on its function: banned, dudungusan, and cultivated. The types and functions of woods possessed by Baduy show that large layers of trees surround the Baduy customary region. As a result, access can only be gained through a series of trails surrounded by trees, which can be regarded as a benefit in reducing the Covid-19 pandemic because it reduces human mobility and hence the transmission of the Covid-19 virus.

A person from the Baduy tribe carries crops with simple technology. Source: mongabay.co.idGiven that Indonesia has 714 tribes ranging from Sabang to Merauke, each with variations in geography, culture, and so on, it is reasonable to suppose that each tribe has its pandemic response strategy. The epidemic managing tradition also breaks the dilemma between tradition and modernity since there are many things they can teach us modernity; by living together to complement each other rather than condemning each other.

Baduy village is integrated with nature, a resource, and protection for them. Source: goodnewsfromIndonesia.id

Baduy village is integrated with nature, a resource, and protection for them. Source: goodnewsfromIndonesia.id

As a requirement of this competition, after being part of Abidin Kusno's webinar: Against Time, I tried to fulfill it by sharing my knowledge through social media. There are still many things that can be improved from this post, but that's the exciting part: we can do more to improve ourselves.

Maybe we know modern architecture in Indonesia is currently in the context of language, and modernization is shown by the advancement of technology (KBBI). But in the context of architecture, modern architecture has its own meaning.

Modern architecture in the context of architectural theory is arguably the architecture of resistance, developed because it felt rococo architecture was excessive and bourgeois - then aided by the existence of world war 2 to strengthen its grip as the architecture of the time. It was engaged in social awareness and education, especially in response to the industrialization of European countries that prioritized function over aesthetics. The existence of modern architecture in Europe feels like a giant of innovation.

If modern architecture is such a giant in Europe, what about Indonesia? Why is modern architecture in Indonesia not echoed as much as post-modern architecture in Indonesia - apart from the cultural aspects largely countered by modern architecture?

One of the factors is the establishment and well-established theories of Western architecture. In contrast, architecture in Indonesia is relatively young, as "architecture" was only introduced when the Dutch colonized Indonesia. It is not yet clearly defined and still often borrows Western architectural theories. After searching the internet, I found two simplifications of modern architecture in Indonesia: "localized modern" and "Indonesian modern."

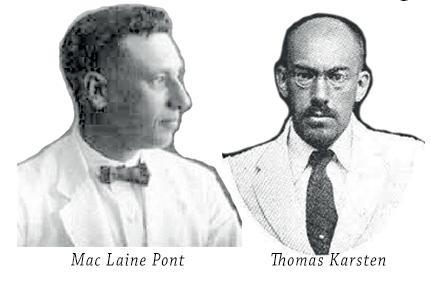

Modern architecture originally came as a carryover from the Netherlands between 1915-1940. Just as in the West Modern architecture was full of upheaval, so too was it in Indonesia. Colonial modern is one of the responses of Dutch architects who came to Indonesia in the early 20th century to the empire style introduced during the reign of Daendels (1808-1811). For these architects, empire style not only violated the climate context, but was also a form of European arrogance and empire style began to be considered a form of deviation from ethical politics that Queen Wilhelmina began to promote in 1901. Much of the design approach of this modern colonial era adapted to the tropical conditions in Indonesia and localization was carried out in the designs of the buildings. Some of the architects who embraced the localization of architecture in Indonesia were Karsten and Pont.

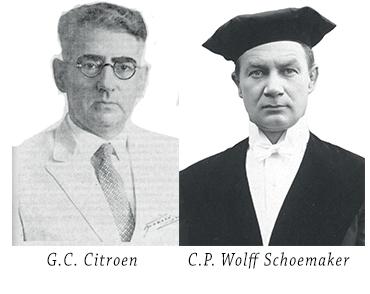

Although referred to as localized modern, not all architects applied cultural aspects in their buildings except from the tropical side, some of these architects were C.P. Wolff Schoemaker and G.C Citroen. Unlike Karsten and Pont, Schoemaker and Citroen used more local aspects in Indonesia as a design exploration and as a form that suits Indonesia's natural conditions.

It wasn't until independence that modern architecture moved in a different direction. As Indonesia's first president, Soekarno wanted to announce to the international community that Indonesia was independent and BERDIKARI (standing on its own feet) by constructing "modern" buildings to build the perception that Indonesia - or Jakartawas different from before. A new Indonesia that was different from when it was still ruled by the Dutch. The early generation of architects - ATAP architects - supported this. Supporting all things modern and leaving traditional things behind with the assumption that it was an old thing that had been done by the Dutch architects and the new Indonesia needed to find again what Indonesian architecture was without local interference. This also promoted Soekarno's project of internationalizing Indonesia.

Perhaps this is where the ambiguity in architectural theory arose; at the same time, European countries organized modern movements with books, congresses, and manifestos; in Indonesia, modern architecture moved because of the power of hegemony or the incumbent at the time. The architecture was distant from the public and only the concern of the few who understood it. When Soekarno as the hegemony holder, fell, so did the modernism associated with him. This was also exacerbated by Soeharto's attempt to erase Soekarno's ideas during his reign. This added to the disconnect that made modern architecture in Indonesia less and less influential among students - especially with Indonesia's theoretical base still not as mature as that of the West.

Some of the most famous architects of Indische Architectuur Source: Wikipedia.com

Some of the most famous architects of Indische Architectuur Source: Wikipedia.com

This article is like a spin-off of the article "Indonesian Modern Architecture," which still refers to Abidin Kusno's book and online lectures at the time. As a connoisseur of his writings, when compiling this article, I felt the need to share the knowledge he had assembled for a broader audience to enjoy.

During the kingdom era, Indonesian society lived and operated organically along the axis of each kingdom's palace as its center. However, after the Dutch entered, there was a shift in the urban typology that undermined the palace's power and destabilized its symbolic power.

Examples of this occurred in Surabaya and Yogyakarta; in Surabaya, the change in urban typology occurred in 1743 after Surabaya was acquired by the Dutch from a political agreement with Pakubuwono II.

The changes took the form of the construction of defense facilities and the strict separation of Bumiputra, European, Chinese, and Arab residences, which later gave birth to interethnic segregation.

In Yogyakarta, the palace's shift in power was caused by the development of railroad and road networks across Java[1]. The Great Post Road, which began during the Daendels era and crossed Java from east to west, connecting cities along the island, challenged the northsouth orientation of the palace square.

This led to a new idea in society that the palace no longer had power, the times had changed, and the center had shifted from the court to the highway. With the emergence of transportation technology and inner-city roads were increasingly crowded with shops, offices, restaurants, etc. Giving a panorama that shows (in the eyes of the population) a shift in power that makes the palace no longer the only center of community orientation.

In Yogyakarta in the 1930s, the "center" of the city was no longer the palace but rather the streets lined with shops. In the cities ruled by the courts, the highway had replaced the alun-alun as the new age symbol.

Imaginary axis of Yogyakarta Palace (left) and Surabaya Map in 1866 (right) Source: Wardani (2011) & Colonialarchitecture.euLikewise, in Surabaya, around 1860, new kampongs emerged, and shops followed the road's median. In the southern part of the city, on the side of the road stretching from Simpang to Societeitstraat, a row of shops stood side by side, and behind them, the kampongs grew denser (von Faber 1931:44). This shows how the city developed as a trading center. As part of the trade network, the shops on the highway now occupied a position of prominence, especially as the end of the depression saw the highway increasingly filled with the shops of Chinese merchants.

Balai Pustaka poster (left) and photo of one of the cities in Java (right) Source: Anderson B.R.O.G (2003) & Colonialarchitecture.eu

North Square of Yogyakarta Palace (left)and Pabean disctrict in Surabaya (right). Source: Colonialarchitecture.eu

Balai Pustaka poster (left) and photo of one of the cities in Java (right) Source: Anderson B.R.O.G (2003) & Colonialarchitecture.eu

North Square of Yogyakarta Palace (left)and Pabean disctrict in Surabaya (right). Source: Colonialarchitecture.eu

This article continues the previous article entitled "About City" and was inspired by Abidin Kusno's work in his book, The New Age of the Modernist Generation: An Architectural Note. This article is intended to increase students' interest, especially my colleagues, in the architectural richness around them and the importance of studying it to enrich design and historical understanding.

Link to Article

One form of change in the city is the Rumah Toko (shophouse), which is one of the house typologies of Chinese people who work as traders. These shophouses are found in many coastal cities in Indonesia, some of which are Semarang, Jakarta, Surabaya, and other coastal areas that are trading places or have large ports.

The early forms and origins of Chinese housing or shophouses are unknown. It usually has 2 to 3 floors; the first is for shops and living, while the second is for living and storage. The shape extends to the back and is separated by a "sky well" in the center.

Slowly the shape that characterizes the shophouse is disappearing. Many shophouses were turned into full-fledged residential houses or had other functions added. Another change is from the form of selling served by shopkeepers to not needing it anymore (self-service form).

Changes in form also have consequences on changes in spatial needs and arrangements. Because the need for increased circulation paths due to the self-service type may also make the building space no longer a place to live.

Pabean District, Surabaya, in 1900 (left) and 2021 (right). Source: armenianimage.org and private collection Two typologies of shophouses in Semarang Source: Sudarwani, M. M. (2012)In terms of social and politics in Indonesia, especially during the new order period, the change of shophouses to be more modern, according to Tiong Hui Koan, was not only due to modernization and development but also due to the country's cultural politics. Chinese signs began to be removed, and shophouse owners in shantytowns such as Glodok covered the entire face of the building with billboards.

This became a symbolic form of closure of the history of ethnic Chinese in Indonesia, giving birth to shophouses with glass, minimalism, and modern style. These shophouses are also marketed as shops or offices with no residential houses like their original form. The shophouse, initially a typology of a compact community building where it could be used as a residence and a place for economic activities, gradually lost its original form. It became reduced to a temporary economic place.

A grocery store with similar typology to a rumah toko (left) and a current convenience store (right). Source: Wikipedia.com

A grocery store with similar typology to a rumah toko (left) and a current convenience store (right). Source: Wikipedia.com

Written as part of a weekly article in the journalistic account "Biwastu" under the auspices of HMA Widyastana Architecture. Part of a collection of articles under the heading "About:" specifically discusses the history of architecture.

Jengki, derived from the word Yankee, is used to name a style of architecture built independently from the knowledge of Indonesian builders. The use of the word Yankee itself may be based on many things. Starting from the influence of American culture or movies. The term jengki itself is used to refer to items that are strange and eccentric; if you look at its equivalent in the era at that time (the 1960s), then many types of goods also have the word jengki attached to them; jengki pants, jengki bicycles, and jengki furniture.

According to Prijotomo, jengki was coined by STM graduates who had been aanemer (building experts) in Dutch companies. At a time when Dutch companies had to leave Indonesia, the spirit of standing on one's own feet without relying on foreigners gave rise to a "rebellious" spirit, becoming the basis for changing the regularity of colonial building elements that were usually based on functionalism.

Jengki's furniture and fashion style. Source: Google Image & historia.id

Jengki's furniture and fashion style. Source: Google Image & historia.id

The jengki style, which mainly developed between 1950-1970, is also known as the bosses style. Because the majority of its users were Chinese people in business, Madurese tobacco entrepreneurs, and the elite at that time. Design elements of jengki include a 35-degree angled gable roof that is mainly displaced or the two planes of the roof do not meet, a sloping front wall decorated with pasted stone ornaments, the presence of roosters arranged linearly with a variety of squares or circles that also function as ventilation. Another characteristic is that the terrace is separate from the main house. The deck generally has a flat roof supported by columns of varying shapes. Also, despite its external form, the jengki has a unique and odd shape. The basic outline of the jengki remains a cube-like folk house in general.

Jengki itself, according to the Kami Arsitek Jengki community, hasseveral types: school jengki, colonial jengki and kampung jengki.

1. School jengki can be seen from its neat shape, which is familiar with the rules of composition, symmetry, balance, accentuation and other aesthetic theories.

The shape of most jengki houses Source: architectureheritage.or.id

Book about Jengki style Source: Google Image

The shape of most jengki houses Source: architectureheritage.or.id

Book about Jengki style Source: Google Image

2. Colonial jengki usually come from colonial houses that have been remodeled. Although it has applied jengki elements in its new construction, it still leaves the symmetrical impression of the previous colonial building.

3. Jengki kampung, on the other hand, looks relatively messy, whether it's the window frames or the stonework on the facades. This form seems to contribute to the character of a village that is not neatly organized but has its own story. These wild jengki were likely built in the early days of jengki, around the 1950s, when there were no graduates from the architecture department.

Written as part of a weekly article in the journalistic account "Biwastu" under the auspices of HMA Widyastana Architecture. Starting from an interest in animation media, I can see the use of architecture in forming an essential background for a story.

Link to Article

Howl's Moving Castle is one of Studio Ghibli's animated films produced by Hayao Miyazaki in 2004. Taking inspiration from the book of the same name by Diana Wynne Jones. It tells the story of the meeting of Sophie Hatter, a hatter, and Howl, a genius wizard who lives in a moving castle. The movie is set in the Edwardian Era, 1901-1910, when the 2nd industrial revolution took place and continued by the 1st world war era, with additional fantasy spices such as magic and unique forms of transportation used. Miyazaki's ability as a director is unquestionable in how he weaves his world to shape the characters and the story. It is as if he can build a realistic impression that these events have something to do with human life and are entirely unrelated. Some architectural styles can also be recognized from Howl's world, which includes:

Palace

On a larger scale, the story is set in a fictional kingdom called Ingary, with its royal center called Kingsbury. Unlike the people's settlements, inspired by Middle Age Gothic architecture, Kingsbury's city center leans more towards 18th-century French neo-classical, with its classical columns and other details.

The townhouse that serves as the setting for Sophie's daily life was inspired by the town of Colmar in the Grand Est province of France, which uses Middle Age Gothic style in its buildings.

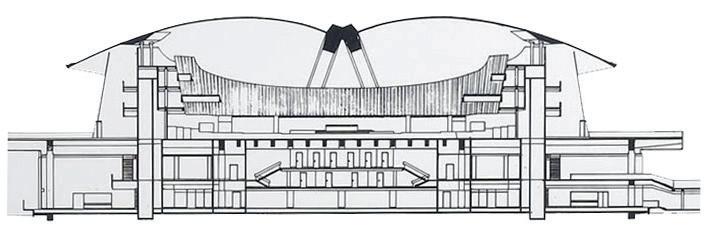

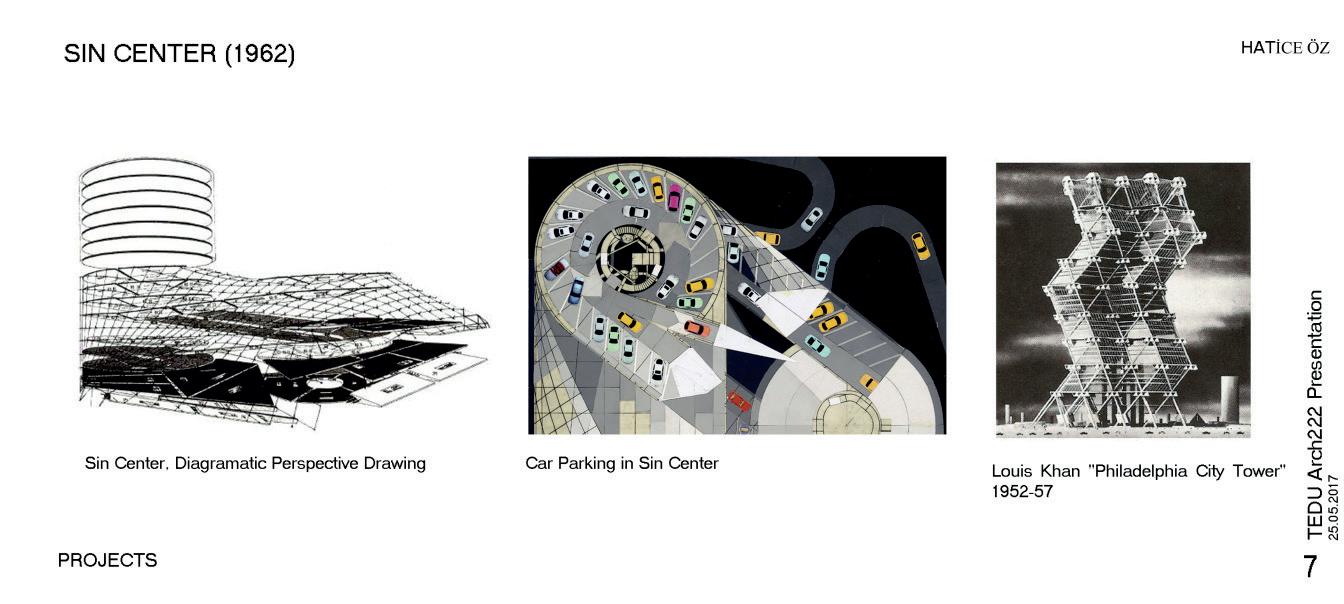

Howl's house, a moving castle, was probably inspired by Ron Herron's Walking: Cities Archigram 5 from 1964. It is a vision of a city that moves to facilitate human needs and movement. But unlike Walking: Cities, whose facade is clean and shiny, the face of the howl house is full of steampunk nuances.

Archigram or Architecture Telegram is a community of neo-futurist, avant-garde, radical, and experimental artists and designers. Founded in 1961 in London, they used technology as the main inspiration in their hypothetical projects. Their works in the form of illustrations, pop-art comics, exhibitions, and films played an important role in pop culture in the 1960s and have had a lasting influence on architecture today.

Howl's moving castle (left) & Archigram (right) Source: Visual Development and Concept Art on tumblr and HATICEOZ

Howl's moving castle (left) & Archigram (right) Source: Visual Development and Concept Art on tumblr and HATICEOZ

One of the things that Biwasmin captured in this film is the anti-war narrative conveyed; Miyazaki, who does not like the existence of war, wants to criticize the Iraq War, which erupted when this film was published.

Perhaps many Biws already know the conflict between classical and gothic architecture, as well as classical and modern architecture. So apart from the direct meaning, there are also implied things in the form of architectural elements in the movie.

1. The palace that issued the war decree is represented by neo-classical architecture, which is a derivative of classical architecture

2. The people who did not like the existence of the war are represented by Gothic architecture

3. Howl himself, who wants to stop the war, is represented by modern architecture.

How about it, Biws? Isn't it interesting how a good depiction of the setting can raise the story elements to be better and even more evocative for the audience with a meaningful story?

Written as part of a weekly article in the journalistic account "Biwastu" under the auspices of HMA Widyastana Architecture. Reported to add literature as a way to create a-more-contextualized designs.

Link to Article

Biws may have often heard theory or design lecturers talk about a "Sense of Place," but what exactly is it?

Sense of Place is a feeling, a sensation obtained when visiting a place or building that becomes the site's or structure's identity. One of the things that plays a role in shaping the sense of place is memory. From our experiences in the area, when we revisit it in the future, we will remember it tied to memories in the past.

According to Bhinnety (2008), some experiences, such as joyous or traumatic events, can be remembered better than others. Animal studies show that when an exciting event occurs, the adrenal medulla increases its secretion in the bloodstream, strengthening memory.

One example of this is daily life at home. When we were young, everyone gathered around the dining table, enjoying dinner and chatting about our daily lives. That activity seems simple, but as adults, we feel that it is a happy memory because home no longer feels like home without siblings who are married or parents who have passed away.

It can also be from the images we build from reading, watching videos, or other things from which we learn what aspects can be associated with that place. So before going to the site, we already have a picture first, without knowing the reality.

For example, according to historia.id, how Indonesia became a new tourist destination in the first half of the 20th century due to the promotion carried out by the Dutch East Indies Government through postcard media, both landscapes and people wearing traditional clothing. This became a European image of the East Indies, with exotic and beautiful scenery. A picture formed due to the influx of knowledge from something that was never known before.

For my 2019 Biwastu Journalist Internship side assignment, I had to create several pieces that I wrote based on my interest in culture and history.

Link to Article

In building construction lessons, you may have learned that the taller the building, the greater the vertical pressure from the pull of gravity and the horizontal force from the blowing wind. There are many ways to overcome these two forces; one relatively old way is to imitate the shape of a pyramid, significant at the bottom and tapering upwards. An example is the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which has 163 floors and stands 829.8 meters high.

Another way to deal with wind thrust is to install a counterweight in the center. If what was written earlier is to put a retaining structure in the center of the building. This is the case with the Taipei 101 building in Taipei, Taiwan, which is 509.20m tall. The ball, which weighs 730 tons, was initially installed to maintain the balance of the building during powerful wind currents. But who would have thought that during the 2008 earthquake in Taipei, this ball saved the building from collapsing and killing hundreds of people inside and around the building. In addition to using structural science in designing these tall buildings, cultural aspects can also be another consideration in designing structures that do not go against the wind.

In the coastal areas of Hong Kong, for example, there is a belief that a dragon and its children live together in a hill area. According to the local view, the dragon will come down occasionally to bathe with its young in the sea. Blocking the way for the dragon and his family to go to the ocean will bring bad luck to the locals. One of the buildings that implemented this was The Repulse Bay, designed by Foster + Partner in 1986. It replaced the previous hotel building of the same name and is a historical relic in Hong Kong, built-in 1920 in a colonial style.

Burj Khalifa in Dubai

Source: luxeadventuretraveler.com

Pendulum in the center of the building Source: slate.com

Burj Khalifa in Dubai

Source: luxeadventuretraveler.com

Pendulum in the center of the building Source: slate.com

But the "Dragon Pit" is part of the feng shui practice that dates back to imperial times in China. Feng shui is the practice of harmonizing a building with its surroundings, and applying this "Dragon Pit" is believed to invite good luck and repel bad luck. So the practice of feng shui itself has become so ingrained in Hong Kong society that it has become part of the local mythos.

Another more practical reason for making this hole is one way to reduce the effects of high-rise building construction in Hong Kong. With so many high-rise buildings being built there, it creates an effect for the residents called the wall effect, which makes the surrounding community complain because, in addition to blocking the view, the airflow is also blocked by many tall buildings. Of course, with such a situation, the government finally made regulations to create gaps between structures, but this does not apply to private facilities and only to commercial buildings. So we can see that the proper design considerations can accommodate various concepts supporting our design from multiple sides.

The Repulse Bay designed by Foster + Partner Source: Wikipedia.com

Dragon pit Source: Michael Driver on TheCultureTrip.com

Dragon pits on buildings in Hong Kong Source: archinnect.com

The Repulse Bay designed by Foster + Partner Source: Wikipedia.com

Dragon pit Source: Michael Driver on TheCultureTrip.com

Dragon pits on buildings in Hong Kong Source: archinnect.com

In design, some things are often overlooked, whether intentionally or not, by architects, one of which is a sense of ownership. Due to the tendency of architects to think of their designs as works of art, building users often end up unable to modify or personalize the spaces created. This alienates architecture from social issues and users, creating inflexible and misunderstood designs. One solution to solving the problem is to use humanism architecture from the viewpoint of Maslow's theory of needs. By taking a case study of UPTD Lingkungan Pondok Sosial Kampung Anak Negeri in Surabaya, an analysis of the relationship between the fulfillment of multilevel requirements and the emergence of identity in the building is carried out. The emergence of this identity is an effort to create a sense of ownership from users to the building they occupy. The study's conclusion shows a connection between humanism and architecture as one of the essential considerations in designing.

aeiko. 2014. 9 real life places that inspired Studio Ghibli Movies, Studio Ghibli Movies. Available at: https://studioghiblimovies.com/9-real-life-places-inspired-studio-ghibli-movie/. Accessed: 09 November 2020.

Archigram. 2004. Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archigram. Accessed: 09 November 2020.

Armando Siahaan, Jengki Homes for a Free Indonesia Archived 2012-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Globe, October 26, 2009

Baskoro, S. 2017. Surabaya sebagai Kota Kolonial Modern pada Akhir Abad ke-19: Industri, Transportasi, Permukiman, dan Kemajemukan Masyarakat. Mozaik Humaniora. 17(1). 157.

HATICEOZ .2017. Archigram – Manifesto, haticeoz. Available at: https://haticeoztedu.wordpress. com/2017/05/27/archigram-manifesto/. Accessed: 08 November 2020.

Howl’s Moving Castle, Hayao Miyazaki 2004 .2018. Art, media, and cinema. Available at: https:// cinema13006398.wordpress.com/2018/09/12/38/. Accessed: 07 November 2020.

Howling for you ... .2012. architectural dialogue. Available at: https://architecturaldialogue.wordpress.com/2012/03/18/1618/. Accessed: 08 November 2020.

Kusno, A. 2012. Zaman Baru Generasi Modern : Sebuah Catatan Arsitektur. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Ombak. pp. 18-24

Nugroho, R., 2014. Menelusur Arsitektur Jengki di Surabaya. [online] KAMI-ARSITEK-JENGKI. Available at: <https://kamiarsitekjengki.wordpress.com/2014/09/07/ menelusur-arsitektur-jengki-di-surabaya-2/> [Accessed 21 April 2021].

Setyabudi, A. and Nugroho, A.M., 2011. Transisi Ruang Arsitektur Rumah Jengki Di Kota Malang, Singosari dan Lawang. Jurnal Jurusan Program Arsitektur Lingkungan Binaan/Fakultas Teknik Universitas Brawijaya.

Sığın, H. .2018. Archigram, ‘Manifesto’ in archigram 1 .May 1961., Hande Sığın. Available at: https:// handesi.wordpress.com/2018/10/08/archigram-manifesto-in-archigram-1-may-1961/. Accessed: 07 November 2020.

Steenman, T. .2022. Guest essay: Architecture and animation with ‘Howl’s moving castle’, Every Movie Has a Lesson. Available at: https://www.everymoviehasalesson.com/blog/2019/12/ guest-essay-architecture-and-animation. Accessed: 08 November 2020.

Visit colmar .2023. France.fr : Actualités, destinations et infos du tourisme en France. Available at: https://www.france.fr/en/alsace-lorraine/aticle/colmar-0. Accessed: 08 November 2020.

Widayat, R., 2006. Spirit Dari Rumah Gaya Jengki Ulasan Tentang Bentuk Estetika Dan Makna. Dimensi Interior, 4(2), pp.80-89.

Selected Works 2019-2022

FATIMATUZ ZAHROH

FATIMATUZ ZAHROH