3 minute read

About City

This article is like a spin-off of the article "Indonesian Modern Architecture," which still refers to Abidin Kusno's book and online lectures at the time. As a connoisseur of his writings, when compiling this article, I felt the need to share the knowledge he had assembled for a broader audience to enjoy.

During the kingdom era, Indonesian society lived and operated organically along the axis of each kingdom's palace as its center. However, after the Dutch entered, there was a shift in the urban typology that undermined the palace's power and destabilized its symbolic power.

Advertisement

Examples of this occurred in Surabaya and Yogyakarta; in Surabaya, the change in urban typology occurred in 1743 after Surabaya was acquired by the Dutch from a political agreement with Pakubuwono II.

The changes took the form of the construction of defense facilities and the strict separation of Bumiputra, European, Chinese, and Arab residences, which later gave birth to interethnic segregation.

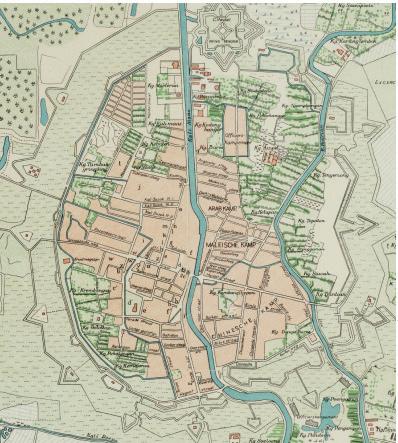

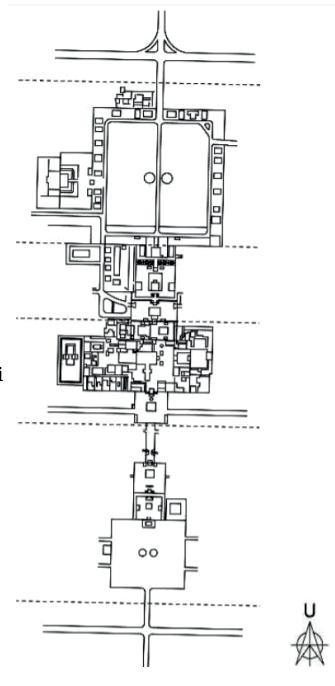

Imaginary axis of Yogyakarta Palace (left) and Surabaya Map in 1866 (right) Source: Wardani (2011) & Colonialarchitecture.eu

In Yogyakarta, the palace's shift in power was caused by the development of railroad and road networks across Java[1]. The Great Post Road, which began during the Daendels era and crossed Java from east to west, connecting cities along the island, challenged the northsouth orientation of the palace square.

This led to a new idea in society that the palace no longer had power, the times had changed, and the center had shifted from the court to the highway. With the emergence of transportation technology and inner-city roads were increasingly crowded with shops, offices, restaurants, etc. Giving a panorama that shows (in the eyes of the population) a shift in power that makes the palace no longer the only center of community orientation.

In Yogyakarta in the 1930s, the "center" of the city was no longer the palace but rather the streets lined with shops. In the cities ruled by the courts, the highway had replaced the alun-alun as the new age symbol.

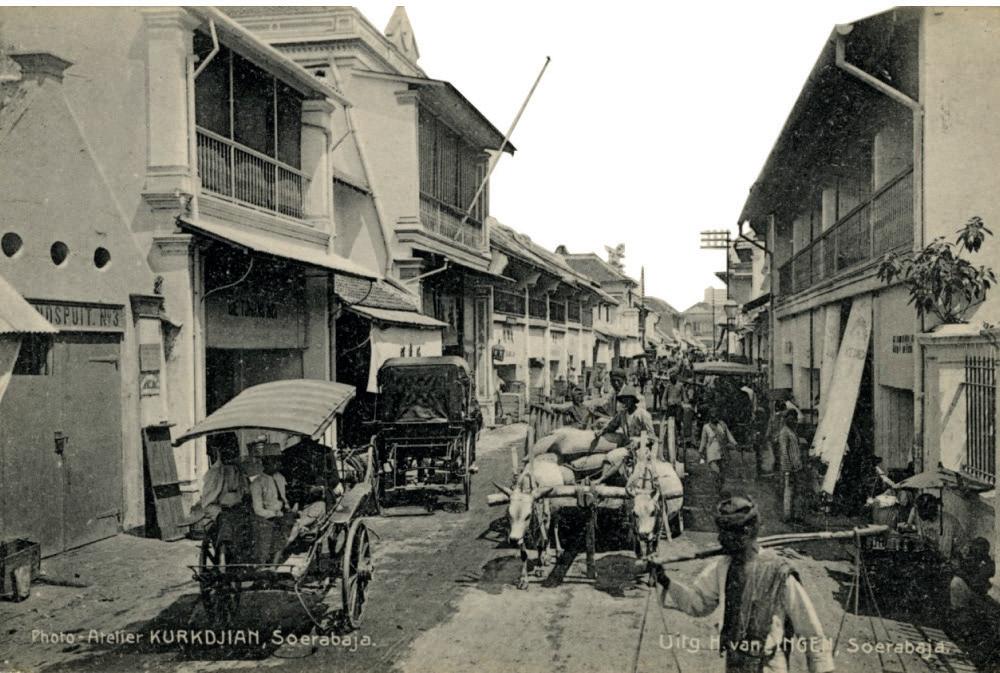

Balai Pustaka poster (left) and photo of one of the cities in Java (right) Source: Anderson B.R.O.G (2003) & Colonialarchitecture.eu

Likewise, in Surabaya, around 1860, new kampongs emerged, and shops followed the road's median. In the southern part of the city, on the side of the road stretching from Simpang to Societeitstraat, a row of shops stood side by side, and behind them, the kampongs grew denser (von Faber 1931:44). This shows how the city developed as a trading center. As part of the trade network, the shops on the highway now occupied a position of prominence, especially as the end of the depression saw the highway increasingly filled with the shops of Chinese merchants.

North Square of Yogyakarta Palace (left)and Pabean disctrict in Surabaya (right). Source: Colonialarchitecture.eu