Outstanding Young Farmers Lindsay and Brady Funk

Outstanding Young Farmers Lindsay and Brady Funk

Introducing the new 2045CR Conveyor and the TL1346 Auger from Meridian. The 2045CR is more than a ‘Canola Capable’ machine. It features an upgraded drive roller, a 12,000BPH capacity, and with only five rollers, it has fewer moving parts than the competition.

The revolutionary TL1346 is our largest Truck Load Auger, and features the new Meridian Hydraulic Drive. Equipped with a 74HP diesel, suspended flighting with hanger bearings, and a hydraulic drive, this is our fastest, quietest, and safest auger yet.

SELF-PROPELLED. SELF-CONTAINED. HYDRAULIC DRIVE.

Free up equipment and space on your yard with Convey-All’s SPSO Conveyors. These high-capacity, heavy duty conveyors are user friendly and high performance. Combine our Bin Fill Conveyors with a Convey-All Transfer Conveyor or Swing Out for ultimate efficiency. This harvest, count on Convey-All Conveyors for your handling needs.

ANGELA LOVELL

Kuntz

Spraying 101 The Transition from Weed Control to Weed Management by Tom Wolf

Zimmer

Kopochinski

Succession Are You Creating a Legacy or Leaving a Liability? Do You Even Know? by Nerissa McNaughton

There’s a future on the land in Alberta and it’s in good hands. Like those before them, the next generation of producers will drive innovation and change, nourishing and protecting the land while feeding the world.

PROUD TO GROW AGRICULTURE IN ALBERTA

Kevin Hursh is one of the country’s leading agricultural commentators. He is an agrologist, journalist and farmer. Kevin and his wife Marlene run Hursh Consulting & Communications based in Saskatoon. They also own and operate a farm near Cabri in southwest Saskatchewan growing a wide variety of crops. Kevin writes regular columns for farm publications and can often be heard on Saskatchewan radio stations. In 2021, Kevin received a Distinguished Agrologist Award from the Saskatchewan Institute of Agrologists. In 2023, he was inducted into the Saskatchewan Agricultural Hall of Fame.

X: @KevinHursh1

How big do you have to be in order to have a viable grain farm – one that can support your family without outside income? Can this be done on 1,000 acres? Can it be done on 3,000 acres?

These are questions I’m sometimes asked. Young farmers working to build a viable operation want an answer and so do outsiders trying to understand grain farm economics.

I’m not an accountant pouring over the financial statements for scores of farms, but here are my thoughts on the issue.

First of all, 1,000 acres in the Red River Valley growing big crops of corn and soybeans is quite different from 1,000 acres of dryland in the Palliser Triangle or 1,000 acres of irrigated land in southern Alberta. The crops are different, the yields are different, the economics are different.

Rather than measuring farm size by acreage, it’s more instructive to judge size by gross return. If a farm’s gross return is under $250,000 a year, it’s unlikely the farm is able to provide a decent income for a family once all expenses are paid.

Well-run operations with a gross annual income of over $500,000 have a better chance of providing a living, but how many people are involved also matters. Farm ownership structures can be complicated and too many hands in the cookie jar can reduce returns for everyone involved.

Even with using a gross income measurement for size, expenses vary so much from farm to farm that it’s impossible to make a general statement about farm size viability until you know more specifics.

Farms in the same soil zone growing similar crops will likely have similar operating expenses per acre. Some will use more fertilizer than others, but costs for seed, crop protection products and diesel fuel are likely to be in the same ballpark on a per acre basis even for farms that vary significantly in size.

The big difference in expenses comes on the fixed expense side. A farm with all its land paid for that is renting very little ground is going to be in a far different category than a farm with sizable land payments and lots of cash rented ground.

Publishers

Pat Ottmann & Tim Ottmann

Editor

Lisa Johnston

Design

Cole Ottmann

Regular Contributors

Kevin Hursh

Tammy Jones

Paul Kuntz

Copy Editor

Scott Shiels

Tom Wolf

Nerissa McNaughton

Sales

Pat Ottmann pat@farmingfortomorrow.ca 587-774-7619

Nancy Bielecki nancy@farmingfortomorrow.ca 587-774-7618

Meghan Stuart meghan@farmingfortomorrow.ca 587-774-7617

/farming4tomorrow

/FFTMagazine

/farming-for-tomorrow

/farmingfortomorrow

WWW.FARMINGFORTOMORROW.CA

Farming For Tomorrow is delivered to 79,873 farm and agribusiness addresses every second month. The areas of distribution include Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Peace region of B.C.

The publisher does not assume any responsibility for the content of any advertisement, and all representations of warranties made in such advertisements are those of the advertiser and not of the publisher. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, in all or in part, without the written permission of the publisher. Canadian Publications mail sales product agreement no. 41126516.

Over the last 15 years, most farms have made more money from land value appreciation than they have from farming. It has become easier to cash flow rented land than newly purchased land. However, land price increases have had a dramatic benefit on a farm’s net worth.

If cash rent is $75, $100 or $125 per acre, that’s an expense you don’t have if the land is owned free and clear. On newly purchased land, your payments per acre often end up even higher than typical rental costs.

The machinery complement also makes a big difference. If a farm’s equipment investment per acre is out of whack as compared to other operations, that’s an additional cost. It also matters whether there are loan payments on the machinery.

If you take a farm’s gross return from grain sales and deduct all the variable costs – seed, fertilizer and crop protection – what you’re left with is a contribution margin: the amount you have left to pay fixed costs including a return to labour and management.

Yields are different each year and grain prices are often volatile. Therefore, the gross return can vary dramatically. However, a farm with high fixed costs is going to have a greater struggle for profitability.

There are efficient farms and inefficient farms in all the size categories. If you’re losing money on every acre, having more acres is unlikely to solve the problem. On the other hand, a small profit per acre adds up when you have more acres.

Over the last 15 years, most farms have made more money from land value appreciation than they have from farming. It has become easier to cash flow rented land than newly purchased land. However, land price increases have had a dramatic benefit on a farm’s net worth.

Yes, a farm can be too small to make a living without outside income. Certainly, the trend is towards larger and larger operations, but there’s no simple answer to how many acres a farm needs in order to be viable.

Scott Shiels

With seeding now in the rear-view mirror, I am sure all of you are looking for opportunities to move your old grain crop and projecting what you will put in the bins this fall. Heading into the summer, it really started to look and feel like we were going to have a tight supply and demand balance on most crop, which should have led us higher across the board. However, it does seem now that we have enough to get us by and into the new crop season. Most likely this is due in part to all the trade uncertainty that occurred in the late winter/early spring with changes in both the U.S. government and our own leadership here in Canada. The other major factor contributing to this situation would be the lack of transparent data on what is produced on the farm and what is exported each year by our markets.

By Angela Lovell

Scott Shiels grew up in Killarney, Man. and has been in the grain industry for 30 years. He has worked with Grain Millers Canada for 10 years and manages procurement for both conventional and organic oats for their Canadian operation.

Scott is an elected board member for Farm and Food Care Saskatchewan and sits on several other committees on both the organic and conventional sides of the oat industry. Scott and his wife Jenn live on an acreage near Yorkton, Sask. Find out more at www. grainmillers.com.

This discussion has been going on for what seems like forever. Working for a company like Grain Millers, which operates in both the U.S. and Canada, allows us to have a better understanding of the differences between our two countries, and how the production numbers, as well as the import/ export data is shared with the masses. Full transparency for everyone involved (not just producers, but grain companies and basically anyone in the import/export space) would be tremendously valuable. However, we have what we have, and we need to make the best of it. For producers, that means gathering all the intel you can, and paying really close attention to the supply and demand numbers that are made public. While the government-issued numbers certainly need to be taken with a grain of salt (or the shaker), there are many independent analysts you can subscribe to – and even some you can get for free – to correlate your own data if desired.

In the oat world, Wild Oats and Oat Information stand out as two of my favourites, both of which provide excellent information on the oat market here on the Prairies. The individuals who compile the information in these two publications have both been in the oat industry for decades, and they have the most comprehensive networks imaginable when it comes to oats. If you are looking to bolster your oat market information, beyond what you receive from me, I strongly suggest trying one or both of these.

For overall information on multiple crops, LeftField Commodity Research, Grain Shark and StoneX are all very good sources. These are all subscription services, but each provides valuable information on different crops. StoneX also provides full market consulting for farmers, taking their service to the next level. I know some farmers who use them for their crop marketing and, so far, I have heard nothing but positive reviews on value for the money. LeftField offers a couple of different options, depending on the crops you want information on, and we have had Jon Driedger – a very knowledgeable and entertaining speaker – present on markets at our annual producer meetings. Grain Shark, I believe, is the youngster in this group, but has gathered a pretty good following here on the Prairies. From all the feedback I have heard, this will continue to grow, as Grain Shark provides very down-to-earth information to subscribers.

Until next time…

Paul Kuntz

Paul Kuntz is the owner of Wheatland Financial. He offers financial consulting and debt broker services. Paul is also an advisor with Global Ag Risk Solutions. He can be reached through wheatlandfinancial.ca.

Now that we have had an election in Canada, I thought it would be a good time to discuss government funding in agriculture. As someone who farms and also makes a living from farmers, I want to make sure there is financial health in our industry. More government money is always better, or is it?

First, let’s look at why the government supports agriculture. Does it give enough money? Where does it go? Should it go somewhere else?

If you search the history of the department of agriculture, you will see that it was formed in 1868, one year after Canada became a country. It was obviously very important, as it was one of the first ministries created. The main focus was on preventing and controlling livestock diseases. I think we can all agree that we need a federal mandate to have success in that area. We need to control what animals come in and the power to control movement of animals within Canada regarding an infectious outbreak.

Since then, the role of government has evolved. On the website for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, they speak of long-term profitability, sustainability and adaptability.

Many industries in Canada receive government funding, like the auto industry in Ontario or the airplane industry in Quebec. But many industries receive nothing. Your local restaurant gets no funding. The plumber you hire or the mechanic at the garage get no funding. Why does agriculture get money and other industries do not?

One reason might be because it helps the Canadian economy when agriculture is supported. Many jobs in Canada come from our industry, so it is in the government’s best interest to support an industry that creates wealth. But other industries, like mining, create wealth and they do not receive any funding.

Another reason might be because we produce food. Most of the agricultural production in Western Canada is exported to other countries. We do produce food, but most of it is not for Canadians. The livestock industry produces food for Canadians, but that industry receives less government funding than the grain production industry does.

I am confident the spirit of intention regarding public money in agriculture was not to support a 30,000-acre farm. This way, more money could be spent in other areas.

What areas are we most likely to see government funding? For most farmers, the biggest influence is with crop insurance, AgriStability and AgriInvest. These programs are known as business risk management and heavily subsidized by public money. As someone who is an insurance advisor with Global Ag Risk Solutions (a private crop insurance company) and also as someone who sells hail insurance, I question why public money is being used to support a specific insurance. This product could be delivered by the private sector and partially paid for by the government.

Another program that has government influence is the Cash Advance Program. This is a loan that producers take against their production, a portion of which is interest free. But more importantly, it is a “No Questions Asked” type of program. As someone who spent most of my life as a banker, this program is a very easy way to secure a lot of operating cash.

There is government money that goes to research. Some of this is through our universities and some of it is direct with Agriculture Canada research stations. This money can help all of the industry and is a wise place to put public money. We can debate what type of research is being funded, but I believe most Canadians would support government funding in research.

If you are a livestock producer in Western Canada, there are very few government programs to help out. There is some infrastructure assistance with wells and dugouts. There is some assistance with cross fencing. Livestock producers have access to AgriStability and AgriInvest as well.

The next area to look at is what farms are getting public money. Although it does not state any specifics on Agriculture Canada’s website, politicians often talk about supporting the “family farm.” Do we need to start defining what a family farm is? Does the tax-paying public care if their money goes to a family farm? We now have farms in Western Canada surpassing 30,000 acres. Some of them are still owned by a family farm. Some of them have multiple owners through corporate structures. Is the spirit of intention of public money in agriculture to support massive corporate

entities? Is there a point when the taxpayer should limit support of an agricultural operation?

One of my original questions was: who should get government money? I think the livestock industry should be better supported. It is stressful to have a few million canola plants suffering in your field due to bad weather but to have 500 animals suffering because there is no rain is a whole other type of stress. Our rainfall insurance programs are weak and not accurate. The price protection programs are also non-relevant. More could be done to support the livestock industry.

Supporting the grain industry through a crop insurance program is good, but the administration of the funds should change. Producers should be able to select where they get their coverage from and use the subsidy where they choose. Maybe a producer just wants to buy hail insurance on their crops. That producer should be allowed to use government money to offset that premium.

I also think there should be tighter limits on how much government money can go to a farm. I am confident the spirit of intention regarding public money in agriculture was not to support a 30,000-acre farm. This way, more money could be spent in other areas.

It all comes back to what the original intention of the money is. I was once told by a farmer from England that the reason their farms are so heavily subsidized is because they want the city dwellers to be able to go for a drive in the country and see beautiful small farms. The intention of the money was to beautify the countryside. I am not sure if this is accurate. If it is, I do not think it is a wise choice of public funds, but it does prove the point that direction of policy can have many different motivations.

There is new leadership in our federal government and new ministers to manage portfolios. Where would we like to see public money in our industry? As fiscally responsible people, where would we get the biggest bang for our buck?

Now is the time to contact government officials and our advocates to let them know.

Langham, SK. July 15-17 Join us and our ag tech partners at booths 363 & 364 during Ag in Motion to explore how Smart Ag solutions is transforming the future of farming. sasktel.com/SmartAg

From fleet management and field monitoring to traceability and connectivity, see firsthand how customizable, datadriven tools can streamline your operation, no matter the size.

BY ANGELA LOVELL PHOTOGRAPHY BY BECKY WIENS PHOTOGRAPHY

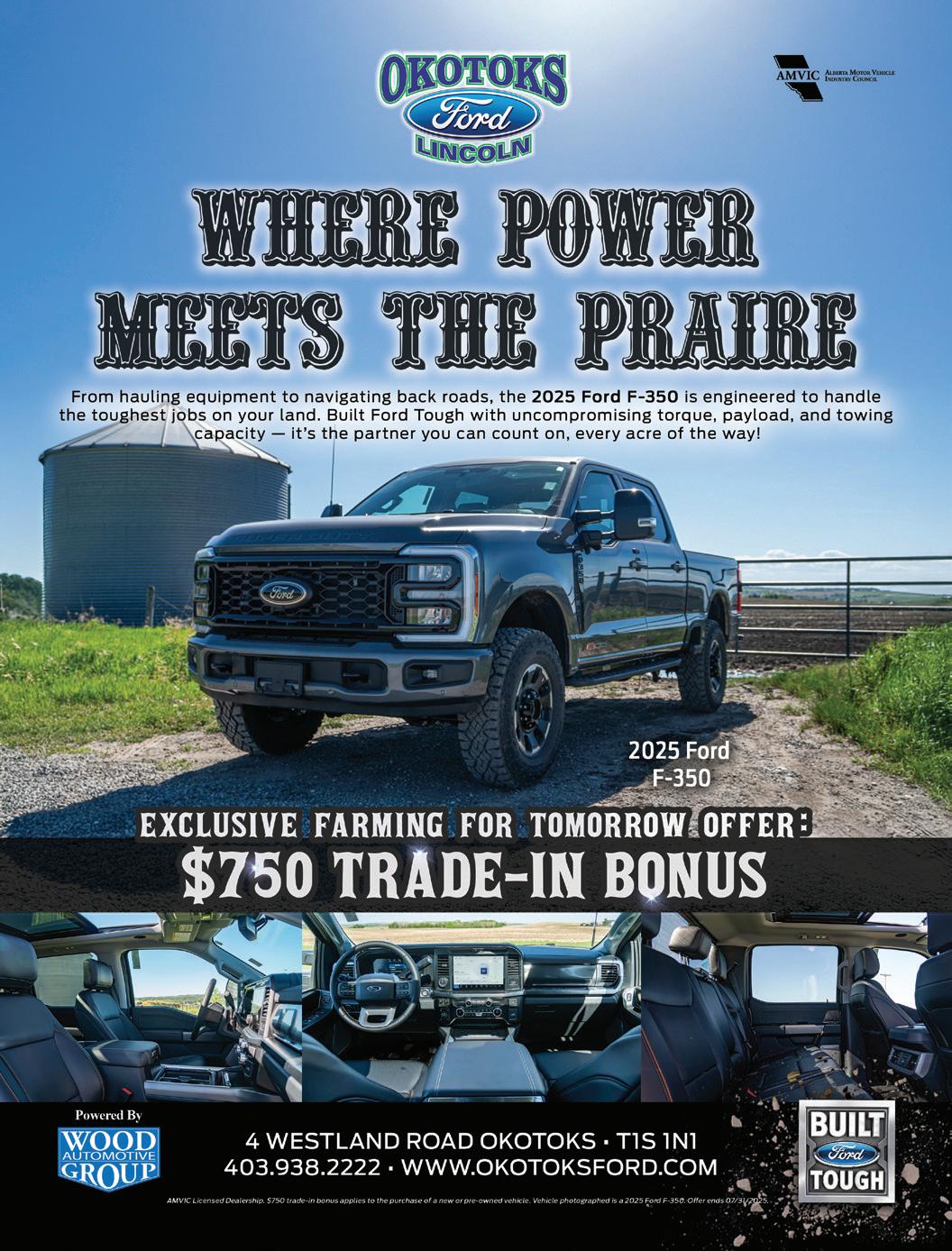

With a willingness to innovate and a constant commitment to land stewardship, Brady and Lindsay Funk were recently awarded the 2025 Saskatchewan Outstanding Young Farmers title and will represent the province in the national finals in Ontario this November.

“I am intrigued with new technology and if it’s going to provide us an opportunity to better ourselves and our farm, then we need to take that seriously and not be scared of change,” Brady Funk says. “I like thinking about new ideas and opportunities to vertically integrate into our farm to help provide generational family farm success and sustainability.”

A prime example is the Funks’ subsurface drip irrigation project, the largest of its kind to date in Canada. Although the investment in time, energy and learning to install the system was high, the Funks estimate it is saving them about 30 per cent in electricity, water and input costs annually, and will pay for itself in a few years.

How it all began

The Funks both grew up on family farms: Brady near Consul, Saskatchewan and Lindsay at the fourth-generation Hildebrand farm near Swift Current. After high school,

“Being able to raise our family in a rural setting is such a neat opportunity. They learn so much. It’s our goal to teach the skills that we’ve learned and pass that on to the next generation so that they can essentially carry that torch if they choose to follow in our footsteps.” - Brady Funk

Lindsay graduated as a registered nurse working in mental health, and Brady trained through John Deere as an agricultural mechanic.

“We felt it was important to spend some time away and learn new skills that could be an asset to our generational family farm, but the goal was always to come back to the farm,” Funk says.

In 2013, Brady became the third partner, along with Lindsay’s dad, Marv, and her brother, Jordan, in the Hildebrand family farm, but the couple soon realized they would need to expand if they wanted to provide the opportunity for their children to grow up on the farm.

“Being able to raise our family in a rural setting is such a neat opportunity,” Funk says. “They learn so much. It’s our goal to teach the skills that we’ve learned and pass that on to the next generation so that they can essentially carry that torch if they choose to follow in our footsteps.”

After dealing with many years of drought, the Funks were looking for some land with irrigation potential, but local prices had skyrocketed, which is why they had to look further afield, eventually purchasing 923 acres one-and-a-half hours away near Lucky Lake, Saskatchewan.

“The land came up for sale and it had an old irrigation pivot on it that was worn out,” Funk says. “So, I knew that there was irrigation potential, but we weren’t stepping into a functioning irrigation farm.”

While they continued to farm the family operation at Swift Current, the Funks incorporated their own farm under the name of Braylin Acres in 2015. After doing soil suitability testing and getting approval from the Water Security Agency, they received the go-ahead to implement an irrigation project on their new site at Lucky Lake, but weren’t really sure what that would look like. The inspiration for the chosen subsurface irrigation system came from a Bible verse.

“We were led to this verse in Genesis 2:6 in the Bible that says ‘In the beginning there were springs that came up from beneath the water of the surface of the Earth’,” Funk says. “From that idea, we started investigating and touring different farms, and that led us to subsurface drip irrigation instead of above-ground pivots.”

It was a daunting endeavour, not least because they had to install all the infrastructure needed, including three-phase power, nine pumps ranging from 50 to 200 horsepower, and miles of pipe to deliver water from the South Saskatchewan River to the field. Water arriving at the field edge is then put through a high micron filtration system to remove any debris that could plug the lines, at which time the Funks can add different nutrients into the water stream.

“We don’t front load all of our nutrients up front,” Funk says. “As the plant is growing, developing and maturing, we insert different moisture probes and do soil and tissue testing to formulate how much nitrogen and other nutrients we need to apply, as we irrigate, for plant optimization.”

The system pulses the water vertically to the top of the soil and stops irrigating when soil moisture probes register adequate moisture levels, which helps reduce disease risk.

“A pivot system waters from the top down and that introduces disease into the plant because the plant is always wet,” Funk says. “With our system, the root system is wet but the above-ground foliage is not wet, so our

“We were led to this verse in Genesis 2:6 in the Bible that says ‘In the beginning there were springs that came up from beneath the water of the surface of the Earth’.”

- Brady Funk

Introducing GSI’s Mixed Flow dryer.

Monitoring yield in the combine is one thing. But the moment of truth is at the scale. GSI’s fuel efficient Mixed Flow helps you haul in the highest quality without stopping to clean screens. It’s part of the industry’s broadest portfolio of dryers, making sure you have the right fit to make more when it matters most.

FIND YOUR PERFECT DRYER WITH OUR EASY SELECTION TOOL.

“One of our core values is to surround ourselves with great people, so we work with a team of agrologists and have an irrigation specialist on-site at all times.”

- Brady Funk

disease pressure is significantly lower, which means a reduction in fungicide applications and savings in diesel from not having to spray.”

The system is drastically more efficient than an aboveground pivot because there is no water loss through evaporation, which reduces overall water use, and saves on electricity costs thanks to the variable frequency controllers that shut the pumps on and off as needed.

The entire system is connected through wireless radio frequency and can be controlled from a mobile device anywhere in the world.

It’s not just the cost savings that motivate the Funks, but also their role as stewards of the land.

“We are called to nurture and care for the land to the best of

our abilities, and we take that seriously,” Funk says. “It’s an annual challenge for us to continue to improve the soil health and the production of our current operation.”

They also believe in surrounding themselves with talented people, something that has been essential as they have developed the irrigation project.

“One of our core values is to surround ourselves with great people, so we work with a team of agrologists and have an irrigation specialist on-site at all times,” Funk says. “It took a tremendous amount of time, energy and capital, but we learned so much and developed some cool relationships. I value good people; we’ve built a good team, and that’s important for long-term generational success.”

That team includes both of the couple’s parents who have been supportive and cheering them on in their farming career and their ambitious irrigation venture. “We wouldn’t

Our state-of-the-art weather stations offer precise, real-time data, empowering you to make informed decisions with confidence. Innovative security cameras monitor your crops and ensure exceptional surveillance, providing peace of mind. Together, these technologies boost operational efficiency, revolutionize your fieldwork, and safeguard your valuable assets.

• Outside temperature and humidity, barometric pressure, wind speed and direction, rainfall, dewpoint, wind chill, forecast, moon phase, alarms, and more.

• Includes solar radiation sensor for evapotranspiration.

• Transmits data to EnviroMonitor Gateway, optional WiFi HD console to connect to weather link cloud data.

• Does require annual fee.

Experience the ultimate outdoor surveillance solution with our solar powered 4G-LTE autonomous security camera. Say goodbye to cables and hello to effortless setup in any outdoor environment away from WI-FI.

Features:

• Live Audio-Video Streaming

• VOSKER SIM Card Included

• VOSKER Data Plan Required

• 100ft Motion Detection

• 90-degree Ultra-Wide Angle View

• Mobile Alerts to your phone

• Night Vision up to 100ft

• Local Backup on microSD

Contact us at fieldtechnology@pattisonag.com or visit us online at pattisonag.com/fieldtechnology

Providing you with agronomic support through VRAFY, Operation Center™ and machine data to make informed decisions on your operation. Bring soils & imagery data into John Deere Operations Center™! Learn about our packages!

• Select

• Premium

• Partnership

Nutrients

“We put an emphasis on giving back and sharing what we’ve been blessed with. We do that by giving to different organizations or giving back to our community.” - Brady Funk

be in this position without both sets of our families believing in us and giving us the freedom to chase this opportunity,” Funk says.

Now that the irrigation project is complete, the Funks plan to spend a couple of years optimizing and tweaking things but are planting the entire acreage of their irrigation project to black beans this year and trying a one-acre vegetable trial with the idea of using their system to diversify into larger scale vegetable production going forward.

“There are many commodities that would thrive and shine with our infrastructure such as romaine lettuce, cucumbers, watermelon, pumpkins, green beans and sweet corn,” Funk says. “It’s baby steps at this point. It is a lot of work, time, capital and energy to pivot into vegetable production because the equipment line is different, and you need a lot more people to harvest, but probably the long-term goal would be to phase out of commercial cropping and divest into vegetable production.”

The Funks have three children, Hudson (8), Roman (7) and Avery (5) and believe they are lucky to do what they love and live their biblical values.

“We put an emphasis on giving back and sharing what we’ve been blessed with,” Funk says. “We do that by giving to different organizations or giving back to our community.”

The family is looking forward to heading to Toronto in November for the national Outstanding Young Farmers final.

“We are grateful for the opportunity to represent Saskatchewan on a national level and look forward to meeting some incredible producers and the other nominees,” Funk says. “We look forward to building friendships and learning about other operations. It’s a unique and inspiring community.”

TAKE THE CRANKING OUT OF YOUR TRAILER LANDING GEAR

• Quick. Easy Install • Use a 12V cordless drill to operate your landing gear

• Can be used for the heaviest of loads such as oversize equipment

• EZ Lift will lift as much as you can crank by hand

• Michel’s offers 2 different brackets to cover most trailers. Some trailers may require specialized brackets that Michel’s will custom-build

• Safely monitor loading of graintrailer from inside your cab

• Less trips up and down a potentially slippery ladder

• Automatic lifts and lowers when rolling tarp system

• High-quality wireless camera and monitors

• Grain auger and conveyor kits, as well as cameras for all different applications

• EZ Opener • Operates using the 200 Series wireless remote

• Set chute limits when programming

• LED indicator flashes when chute is opening

• Chute position feedback • Can be mounted on either side of trailer

By Becky Zimmer

With sustainability and precision agriculture becoming a hot topic in the last few decades, more and more machinery companies are taking on the task of developing their own answers to precision spraying.

While it’s nothing new to North American agriculture, industry professionals and developers are excited for what the future holds for spot spraying technology, where sprayers or mountable systems use sensors or cameras to detect and spray only the weeds that need to be treated with herbicide.

Spot spraying has been around for decades. The Concord DetectSpray, which was later called the Trimble WeedSeeker, came out in 1992 using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) technology to detect and spray weeds using RGB (red-green-blue) wavelengths.

Tom Wolf doesn’t know anyone who actually bought or used a Concord in Western Canada back in the ‘90s, but after working in the industry for the past 36 years, spot spraying has been one of the most exciting developments of his career. Even if adoption has been slow going, Wolf notes several options currently available for western canadian farmers, including WEED-IT and the John Deere See & Spray™ Select.

Jason Wiens, Precision ag lead in southern Alberta for

Brandt, says this is the first year the John Deere See & Spray sprayers have been readily available to farmers, and they are doing their best to get the word out. Using green-on-brown spraying, RGB cameras sense the green colour against brown soil. During pre-seed burn-off, these are nothing other than unwanted weeds.

Even at this early-adopter stage, Wiens is starting to see sales pick up with five systems sold in their trade region. While they are getting the market excited for the technology, it is a tricky time since they are still working on product development. As well as being sold as a brand-new sprayer, John Deere is already working on a retrofitted system that could be available as early as June.

With the RGB camera system, Wiens notes they are seeing anywhere from 70 to 85 per cent reduction in chemical usage, and farmers have been extremely happy with the See & Spray performance.

“It’ll spray a plant the size of a dime at anywhere from 12 to 15 miles/hour and we haven’t heard of any misses or anything like that,” he says. “Guys are pretty happy with the coverage that they’re getting so far.”

Researchers at Iowa State University used the See & SprayTM Ultimate for field trials back in 2024 and saw an average of 76

per cent product savings and an economic savings of nearly $6,500 USD ($15.7USD/ac) between five test plots, according research results published by Doug Houser, Matt Darr and Ryan Huffman.

WEED-IT originated in the Netherlands, but has been in Canada since 1999.

“During the pre-seed burn-off, their line scanner detects the chlorophyll of actively growing plants and gives them a hit of herbicide,” says Dieter Schwarz, general manager of WEED-IT Canada, based in Winnipeg. “This is especially advantageous for plants like koshia that have a purple colour in the early stages and broadens those optimal spraying conditions.”

Schwarz continues, “It (kochia) still gives off chlorophyll to the scanner, so the scanner will still pick it up. It’s not beholden to that plant being a certain shape or colour. We (the system) are not beholden to light conditions or dust conditions. Our scanner works at night. It’s a very good system for the conditions that we encounter on the Prairies.”

During Joy Agnew’s 2021-22 field trials, she and her team studied WEED-IT precision spray technology under three treatments: full spray, spot spray and bias spray, along with spot spray plus a reduced full spray, including a control with

“It’ll spray a plant the size of a dime at anywhere from 12 to 15 miles/hour and we haven’t heard of any misses or anything like that. Guys are pretty happy with the coverage that they’re getting so far.” - Jason Wiens

no herbicide application during pre-seeding burn-off.

Agnew’s paper, “Performance and cost benefit of optical spot spraying technologies in conventional, dryland farming in Western Canada,” looked at spot spraying technology performance and its impact on chemical use and crop yields. It was funded and published by Sask Wheat in partnership with Alberta Innovates and Western Grains Research Foundation.

Looking at the spot spraying treatment, upwards of 97 per cent less herbicide was applied in 2021 to a herbicide-tolerant canola variety and 98 per cent less herbicide was applied in 2022 to a herbicide-tolerant barley variety. The decrease in weed density was between 55 and 81 per cent in 2021 and between 83 to 88 per cent in 2022.

Agnew also noted that crop yields were not improved using pre-seeding burn-off. However, if weed management is deemed essential, spot spraying significantly reduces input application.

“Herbicide bills could be upwards of $50/acre,” says Wolf, “so any way farmers could cut input costs without losing efficiency is a very desirable outcome. Think of it this way. You have a 10,000-acre farm and you have a $50-per-acre bill, that’s $500,000 you can cut in half. That’s big money.”

Especially with dual tank systems and bias spray, Wolf says there is an option for farmers to broadcast spray at a lesser concentration as well as spot spray for some added coverage, but that will limit the herbicide reduction some farmers might be seeking.

Should cost savings be the only reason to adopt this technology?

“Spot spraying could also slow down the ever-growing problem of herbicide resistance,” says Wolf, “which is another important reason for farmers to cut back their input usage.”

This could be an important investment for farmers in more ways than just cost.

“We are in a stage in herbicide use worldwide where resistance has become too big to ignore. We’re simply losing herbicides to some weeds. Once those herbicides are no longer useful, we might end up with a weed that we just simply can’t control with our herbicide portfolio. That is in our future.”

Pre-seed burn-off is a common practice in Western Canada, but the conventional use of broad application to entire fields poses “a number of negative impacts on the environment,” including “soil health; water quality, following runoff of chemicals into surface water bodies like creeks; infiltration into groundwater sources and air quality, with the possibility of subsequent ecological damage to trees or other vegetation from spray drift,” wrote Agnew.

“However,” notes Wolf, “given the ecological and economic advantages, there are still challenges ahead for spot spray adoption. For those mid-season applications, a green-on-green system, spraying green weeds among green crops, would be beneficial to western Canadian farmers. It is most commonly restricted to spraying crop rows instead of the entire field, an especially useful practice for cotton, corn and soybean crops.

“Spot spraying could also slow down the ever growing problem of herbicide resistance, which is another important reason for farmers to cut back their input usage.”

- Tom Wolf

United States farmers have adopted this practice for these are big markets. Agrifac’s AiCPlus uses the Intelligent Spot Spraying System from Bilberry to distinguish grasses from the cereal canopy, but is yet to recognize broadleaf weeds.”

Other companies that Wolf is keeping his eye on for their green-on-green products is Greeneye Technology™, which is gaining traction in the United States; ONE SMART SPRAY, a partnership between Bosch and BASF; and Carbon Bee, a French company popular in South Africa and Australia that is expected to enter the Canadian marketplace in 2026.

“Improvements to green-on-green technology are on the way,” confirms Wolf. “It’s been a little bit slower to see green-on-green in our small seeded grains and oilseeds, but we’re hoping for them to arrive.”

Farmers are also questioning the system’s efficiency.

“With green-on-brown, there isn’t much the camera doesn’t pick up,” says Wolf, “but companies are looking to expand spot spray usage to other avenues, like desiccation and fungicide application. This makes the accuracy of the spray more of a challenge since the camera will have to spray through the canopy in some instances.

“In ideal conditions, there is one sensor for every four nozzles in a common one metre row spacing. Pointing the camera ahead one metre gives the whole system maybe 100-200 milliseconds in which to make a decision, and that seems to be enough time. When cameras have to take a deeper look into the canopy, that camera angle will be even more important.

“Current price points of brand-new spot sprayers have been a concern,” he concludes, “which means larger farms will be seeing the benefits before smaller operations.”

However, those savings can nonetheless become investments for farmers as they save money on inputs.

Farmers share their interest and experience with hybrid rye and what growers need to take into consideration

By Lisa Kopochinski

Hybrid rye varieties have become much more common in Western Canada over the past decade. This has largely been driven by its impressive performance, particularly under successful rye-growing conditions.

First introduced to farmers on a trial basis, hybrid rye showed its success quickly, with a yield increase over conventional rye by approximately 30 per cent.

This versatile cereal crop serves a wide range of end-use markets – including feed (forage and grain), food (milling and distilling), fuel and cover cropping – making it a flexible and future-ready option for Canadian growers.

Matt Gosling, owner of Premium Ag (an agriculture consulting company formed in Strathmore, Alberta in 2003), calls hybrid rye his favourite crop and the best herbicide on the market, believing there is no other cereal crop with as much genetic potential.

“What I like most about the farming industry is all the life skills it presents,” he says. “From work ethic to patience to mental strength to business planning to people skills. There is a bit of everything. The technology advancements in genetics,

“From work ethic to patience to mental strength to business planning to people skills. There is a bit of everything. The technology advancements in genetics, machinery and agronomy are very exciting and will help bridge the gap into the new generation entering the industry.” - Matt Gosling

machinery and agronomy are very exciting and will help bridge the gap into the new generation entering the industry.”

He adds hybrid rye is super nutrient efficient, with disease

www.kws.com/ca

rarely being an issue. “It’s harvested early, and super competitive with weeds.”

Brad Crammond, owner of BT Crammond Farms Ltd. near Austin, Manitoba, grows wheat, canola, seed and commercial soybeans, and hybrid fall rye. What he loves most about farming and the agricultural industry is the challenge.

“Being able to have a fresh start every season to try to improve keeps a person continually motivated,” says Crammond. “I believe that is why there is such a push for innovation in our industry. Everyone involved is inherently driven to succeed.”

After growing fall rye on select fields for over a decade, Crammond experienced success, but says yields were variable and standability a challenge in certain conditions. “After watching neighbours grow KWS hybrid fall rye for a few seasons, we decided to try it up against our old OP variety. That first year, we saw a 22-bushel yield increase, and ease of harvest was excellent. We’ve grown KWS hybrids ever since.”

Dale Wylie, owner of Wylie Seeds in Biggar, Saskatchewan –which carries a full line of certified, seeds, cereals, corn, soybeans and pulses – says hybrid fall rye has become a big part of his farm’s rotation.

When asked about specific noteworthy benefits, Wylie says, “It is a very competitive crop over other cereals, so economically, it’s a benefit.” Other perks include more diversity in the crop rotation. “You’re planting it in the fall and taking advantage of early spring moisture. Then you have an earlier harvest. And from a wheat management standpoint, no herbicides are used, so economically, there’s another benefit.”

Gosling sees incredible yield potential on dryland and irrigation, with a massive straw deposit. “Being a fall seeded crop, it hits anthesis around the most important day of the year – June 21! It’s early to get to reproduction and grain fill. So, in these hot July months we’ve seen, yield isn’t punished to the degree that spring seeded crops are. It’s a great way to help manage herbicide resistance. I’ve never sprayed for wild oats in hybrid rye because it’s so competitive.”

Crammond agrees and adds, “If you receive adequate moisture and fertilize for optimal yield, it always seems to produce –even on poorer land. Harvestability is greatly improved as well with very little lodging and much shorter straw.”

As for what farmers need to do to be successful in preparing for the fall, he says it is important to have everything ready to go to ensure it is planted on time.

“Field selection starts the year before with previous crop and

“You’re planting it in the fall and taking advantage of early spring moisture. Then you have an earlier harvest. And from a wheat management standpoint, no herbicides are used, so economically, there’s another benefit.”

- Dale Wylie

variety selection to make sure it is off in time to seed. We always plant our rye on canola stubble to encourage good snow cover for the overwintering plants. Also, make sure the seedbed is clean and free of heavy residue to ensure good germination, and manage fertility using your equipment capabilities.”

Crammond adds that he always harrows the canola stubble prior to planting the rye to encourage volunteer growth, smoothing and spreading any residue issues.

“It’s a very aggressive plant and you don’t want it competing for moisture and nutrients the following season. A pre-seed burn-off is always done as well. We typically swath our rye. It negates the need for a pre-harvest application, hastens maturity and dries the straw out for better combine performance.”

Gosling finds shallow seeding beneficial, saying 0.5 inch seems to be ideal. “And you want to seed into canola or pulse stubble, but I’m comfortable seeding into cereal stubble also. It might look a bit hairy in the fall, but the frost takes care of that. Fertility timing is flexible, but I’d be aggressive on P&K (phosphorus and potassium) with it going through winter. Always follow rye with canola or a pulse to control the volunteer rye plants, and be timely with glyphosate applications ahead of seeding the next crop to control as many as possible.

He adds the only drawback is that this is a niche crop. “Hitting the milling market is great, but it’s a small market and a crop that you’ll likely have to store, so cash flow is spread out to 12 to 18 months.”

By Teresa Zimmer

Every combine make and model is different, and the concaves should be too. Razors Edge Concaves from Thunderstruck Ag Equipment are designed around the combine, offering a tailored harvest solution that enhances threshing performance across various crops and conditions.

The bar spacing pattern on Razors Edge Concaves is different based on how the material flows through each combine, while other concaves have the same spacing and configuration for every combine, whether it be a John Deere, Case IH, New Holland or Fendt.

“This allows us to harvest all crops without changing concaves, without using cover plates and without putting inserts in. We’re able to harvest in all crops and all conditions with one set of concaves,” says Jeremy Matuszewski, president and founder of Thunderstruck Ag Equipment in Winkler, Manitoba.

For example, a John Deere single rotor combine typically overloads the left-hand side, with material hitting the concave section right at the front of the combine. Matuszewski explains, “We created a bar spacing pattern that allows farmers to get max threshing where the material hits the concave section but then, with that same variable pattern we open up the concave section we are forcing the material to unload where it normally doesn’t unload so that we can increase the separating area by evenly distributing the material

across it. By doing this farmers are able to make the combine go faster, significantly reduce rotor and sieve loss while decreasing fuel consumption.”

The innovative design of Razors Edge Concaves results in numerous benefits for farmers, including less fuel consumption, better sample quality, reduced combine loss and increased ground speed. “All of that without having to change concaves, so you also save time,” adds Matuszewski. “And as we all know, time is money, especially during harvest.”

Matuszewski feels that one of the biggest benefits to farmers is reduced fuel consumption due to decreased rotor speed which is is especially important to farmers around the world due to increased fuel costs and tax.

And in canola, capacity is key, as most combines can only go two to two-and-a-half miles per hour to avoid losses out the back. Matuszewski says Razors Edge Concaves allow farmers to increase their speed by an extra mile per hour while keeping losses under a bushel per acre. This increased speed means fewer hours on the combine, resulting in less depreciation and maintenance, and more time saved during the busy harvest season.

Razors Edge Concaves have proven to be a game-changer

for farmers. “There are so many things that happen when you design a concave around the combine. I’m not sure why nobody’s ever done this before, but it’s really been something that has been a game-changer for us,” says Matuszewski.

Several years ago, while selling a different concave, Matuszewski found himself questioning why no one had designed a concave built around the combine. “This eliminates so many of the issues farmers have,” he says. “It seems so simple, yet sometimes the greatest things are the simplest things.”

The prototype concaves designed by Matuszewski were jokingly named “Razor’s Edge,” inspired by the AC/DC album featuring the song “Thunderstruck.” The name stuck due to the sharp edge on the concave that helps thresh tough crops. A technique called laser cladding creates this razor-sharp edge.

After extensive testing in Australia and North America for two years, Matuszewski launched the Razors Edge Concaves last November. Thunderstruck Ag Equipment is currently selling the concaves for John Deere, Case IH, New Holland and Fendt combines in Canada, Australia, Denmark, Greece, Brazil and the United States. Matuszewski is hoping a trip to the

“There are so many things that happen when you design a concave around the combine. I’m not sure why nobody’s ever done this before, but it’s really been something that has been a game-changer for us.”

- Jeremy Matuszewski

Agritechnica farm show in Germany this coming fall will open up the European market for them.

Farmers can see the new Razors Edge Concaves at upcoming farm shows, including Ag in Motion in Saskatchewan, Canada’s Outdoor Farm Show in Ontario, Cypress Farm and Ranch Show in Medicine Hat, and Agri-Trade in Alberta.

For more information on Razors Edge Concaves, visit thunderstruckag.com.

By Lisa Kopochinski

As for what can be expected this year, many things are on the minds of farmers.

There are market uncertainties, trade relations, rising input costs and weather concerns going into any growing season. And with climate change, these uncertainties only grow.

The tariff and trade situation is also forefront in everyone’s mind these days. Much like the weather, there is little a farmer can do to change it. However, just like the weather, there are risk management strategies farmers can use to minimize the downside and maximize the upside.

Farming For Tomorrow recently had the opportunity to talk with Chris Barker, executive director of the Saskatchewan Seeds Growers Association, and Kayla FitzPatrick, director of communications at Fertilizer Canada, to discuss some of the biggest issues that farmers are facing on the Prairies this year and what steps should be taken. Here is what they had to say.

Farming For Tomorrow: The industry can expect market uncertainties, particularly with Canada’s relations with the U.S. What should our farmers be prepared for?

Chris Barker: The U.S. is our largest trading partner, so a lack of trade policy consistency from them is a huge risk for Canadian farmers. Food and food ingredients are somewhat protected, as demand is inelastic. There will be areas though where the U.S.

will try to fill local demand with the soy, corn and wheat they would normally export. Much bigger issues are likely around farm equipment and parts, as complex manufacturing supply chains are likely to be caught up in multiple tariffs.

Kayla FitzPatrick: Our advice is to always work closely with your ag-retailer and/or Certified Crop Adviser, as they are your best resource for advice and product availability. Planning ahead can help ease some concerns. For example, working with a trusted 4R advisor to develop a 4R plan can help farmers map out and optimize their fertilizer investment.

FFT: Could there be the possibility of tariffs since a significant percentage of our ag exports are shipped to the U.S.? How much could this hurt our farmers?

CB: There will be tariff impacts on Canadian farm exports, whether direct tariffs or an indirect impact on the ability of farmers to operate. The scope and scale of the pain is unknown, which is a huge pain point for agriculture. The inability to plan and the market uncertainty are huge risks for Canadian farmers.

KF: I can’t speak to the impact of tariffs on ag exports, but I can say that the fair free trade flow of fertilizer in North America is important to farmers on both sides of the border.

FFT: Can you comment on the rising input costs for

essentials such as fertilizer, seed and machinery? What advice can you offer to farmers?

CB: Farmers need to maximize their productivity by using the best technology available. That means using newer crop varieties with proven yield advantages over older varieties. Newer varieties have been bred under the current climactic conditions for the demands of today’s market.

KF: As a globally traded commodity, fertilizer prices are vulnerable to geopolitical events and turmoil, like threats of a trade war. Farmers should speak with their ag retailers to get a better understanding of the supply locally. Farmers can also look to implement 4R Nutrient Stewardship best management practices to optimize nutrient uptake and help maximize their investment in fertilizer inputs.

FFT: What challenges can farmers expect this year and for the next several years with respect to government policies and regulations?

CB: The biggest challenge farmers will face this year and for the foreseeable future with respect to government is to be heard. There is going to be a lot of noise from all sectors about the need for support in the wake of U.S. policy. If each segment of the agriculture industry tries to speak on their own, they will not be heard. All the voices within agriculture need to have the same message. Agriculture is foundational to a prosperous Canada.

KF: The new Liberal government has indicated in their election platform that food security is a priority, but we will still need to see what policies and regulations that translates to. Recently, the minister of agriculture’s office used ambitious language about cutting red tape and putting agriculture at the forefront of Canadian economic policies, and we would like to see more of this approach. Canada has the potential to be an agricultural superpower, and now is the time to step up and implement smart policies that support the sector.

FFT: When it comes to unpredictable weather, what is your advice to farmers in adapting to this?

CB: This is perhaps the easiest question of the bunch. Farmers always face unpredictable weather. The best defence is to use the best technology available. That means the best management and the best inputs. For me, that means the best genetics available. Newer varieties are bred and selected under today’s climate to today’s market.

KF: Weather is a significant challenge in agriculture, and while it is not a complete solution, innovation in farming can be a resource. Precision agriculture and innovative new products can help growers manage unpredictable weather.

It all starts with the soil. When it’s healthy, everything works better—stronger roots, improved structure, and more efficient use of nutrients. But after years of wear, many soils need support to perform at their best. Black Earth humic solutions help restore soil vitality from the ground up. With high-purity Humalite and consistent quality, our products enhance moisture retention, boost nutrient availability, and improve overall soil health—naturally. Easy to integrate and built for results, Black Earth gives your soil the foundation it needs for long-term productivity.

Tom Wolf, PhD, P.Ag.

Tom Wolf grew up on a grain farm in southern Manitoba. He obtained his BSA and M.Sc. (Plant Science) at the University of Manitoba and his PhD (Agronomy) at Ohio State University. Tom was a research scientist with Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada for 17 years before forming AgriMetrix, an agricultural research company that he now operates in Saskatoon. He specializes in spray drift, pesticide efficacy and sprayer tank cleanout, and conducts research and training on these topics throughout Canada. Tom sits on the Board of the Saskatchewan Soil Conservation Association, is an active member of the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers and is a member and past president of the Canadian Weed Science Society.

I remember the moment well. It was 1986, and I was a summer student for DuPont. One of my tasks was to help demonstrate the performance of a new group of herbicides, the sulfonylureas (SU), on broadleaf weed control in cereals. As remains commonplace, we compared these new products to existing standards, in this case Bucrtril-M (MCPA/bromoxynil); and to make it more challenging, we sprayed the plots a bit late to give the likes of redroot pigweed, lamb’s-quarters and wild buckwheat an edge.

Of course, the new SUs did very well. As we showed the crispy weed skeletons to our tour attendees, we looked for signs of excitement in the farmers’ stoic eyes. Why wouldn’t they be impressed? These new herbicides showed not just weed-killing prowess, but also crop safety, low use rates and low mammalian and environmental toxicity. At that moment, I became convinced that we were finally poised to win the age-old battle against not just broadleaf weeds in cereals, but with the recent introduction of the remarkably effective Group 1 graminicides, that battle as well! We would control weeds. The future looked bright. Better get some shades.

It is with a bit of embarrassment that I look back on those naive views now. Lamb’s-quarters, wild buckwheat, wild oats and green foxtail are alive and well in 2025. In fact, these four weeds have not been displaced from their positions as the top five most abundant weeds in Western Canada since surveys began in the 1970s, according to Julia Leeson of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Not only that, Leeson’s surveys show there are a host of weeds rising in abundance on our farms (kochia, volunteer canola, annual sow-thistle), despite intensive herbicide use.

If my enthusiastic young self transported through time from 1986 to the present and asked me where it all fell apart, how would I answer?

I’d probably start with genetics. Weed genomes are remarkably diverse. They contain genes that allow them to adapt to a large variety of conditions. For one, they have dormancy traits in their seeds that permit them to schedule their emergence to conditions that increase their likelihood of success and procreation. Most can wait many years to germinate. When they do, they can

tailor their growth habits to both competitive and open environments, long and short growing seasons and dry and wet conditions with vast ranges of physical size and seed production.

Weeds are also well adapted to move their seed long distances by wind, water or other vectors. In other words, if weed control measures slip up, weeds will quickly take advantage.

A second aspect of the diverse genome is the presence of different versions of the same enzymes in the cells of some small percentage of plants. Enzymes are proteins and are comprised of long chains of amino acids. The sequence of these amino acids determines how the proteins fold into clusters that ultimately function to catalyze chemical reactions in the cell. Many herbicides, including the Group 1, 2 and 9 modes of action, inhibit single enzymes that are critical to the life of the plant by binding with the given enzyme and limiting its ability to catalyze the designated chemical reaction.

A single change in the amino acid sequence can change the fold pattern and render the enzyme ineffective, causing plant death. Some sequence changes do not affect enzyme function but instead prevent the herbicide from binding on it. This sequence change confers what is known as binding site resistance. It turns out that weeds contain genes with just these types of mutations, albeit in very low numbers.

Unbeknown to my 1986 self, by repeatedly using these

A

good system is one in which some level of consistency and reliability can be achieved. In farming, as in any business, a predictable business environment is essential to long-term planning.

herbicides, we quickly selected for the resistant genotypes. Between 1988 and 2021, scientists have documented 68 cases of Group 2 resistance in Canada, according to Dr. Ian Heap’s website weedscience.org, spanning 25 weeds including redroot pigweed, lamb’s-quarters, wild buckwheat, cleavers and kochia. By comparison, the old industry standard of MCPA/bromoxynil counts five cases of resistance on five weeds between 1990 and 2019.

Binding site resistance is the most obvious reason for problems with sole reliance on herbicides for weed control. However, more subtle factors can also play a role in reducing herbicide effectiveness, such as reduced absorption and translocation, both in response to genes and environmental conditions.

We select for resistance by the act of using a herbicide. Yes, we can delay resistance by using better application practices that increase efficacy and prevent tolerance to herbicides from polygenic resistance, but the use of herbicides commits us to a one-way street of inevitable resistance in at least one weed on all farms.

Weed escapes do not have to be caused by resistance. One of the most frequent causes is poor control in sprayer wheel

tracks. There are a number of reasons for this, including the physical damage of wheels on weeds, reducing plant vigour and product uptake. The displacement of sprays due to wheel aerodynamics (increasing with speed and lug depth) and the presence of dust may also play a role, particularly with dust-sensitive products such as glyphosate and diquat. All these contributing factors have become more prominent since 1986.

Secondary emergence of weeds due to increased soil-seed contact after compaction can also contribute to escapes from post-emergence herbicide application. Larger, heavier, fastermoving equipment is once again a large part of the cause.

A recent publication by the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) in Australia suggested that the use of coarser sprays and higher water volumes, combined with slower travel speeds, was most likely to decrease the loss of control in wheel tracks. They suggested that mudguards and flaps may also be beneficial. Spraying when the soil is moist may also minimize dust.

A residual herbicide provides some level of insurance that a certain level of weed control persists even when weeds survive a post-emergent application. In cereal and oilseed

production, we are only now rediscovering the utility and power of these products.

Harvest seed destructors, though still not commonplace, are available and these have minimized the spread of weed seeds that plants have not shed by harvest time. Although seeds still attached to weeds may be a small portion of total seeds produced, the act of destroying them has become very relevant when one considers the ability of a modern combine straw and chaff spreader to distribute residue 40 to 50 feet. A small patch can grow very quickly when spread that far.

So, where did we go wrong in these past 40 years? The first mistake is in our words. We believed that weed control was possible and desirable. To a large degree, we still believe that. So, the first change is to be humble and admit that we are really talking about weed management. We have not been eliminating weeds. We may have been managing them, when they’re not managing us.

I would tell my younger self not to underestimate the diversity of weeds and their ability to adapt to niche conditions. Despite the tremendous efficacy of herbicides, I would warn against the mistake of relying too much on any one method of weed control. I would stress the need to develop integrated systems in which weed population densities could be reduced without the use of herbicides. We know what these are – diverse crop rotations, including the integration of either short- or longterm forage stands. Higher seeding rates and competitive crops and cultivars have shown to be very powerful ways of reducing weed density.

I recognize that in light of tremendous results achieved with herbicides, and only sporadic accounts of resistance in the early

years, these practices would have been a hard sell in the 1980s, but even back then, herbicides failed and the setback in terms of yield loss and soil weed seedbank fortification was felt for years.

I would also stress the importance of early detection and intervention. A weed patch that survived a spray pass could certainly be resistant, but not necessarily. Perhaps there is an underlying soil condition that merits attention. There is no substitute for eyes on the ground, diligence and attention to detail, even when managing large acreages.

A good system is one in which some level of consistency and reliability can be achieved. In farming, as in any business, a predictable business environment is essential to long-term planning. A sudden change in the rules of the game is never welcome. Yes, adaptation is possible, but being on the back foot and playing catch-up is not a winning situation.

Agronomy is no different.

On my trip to Australia this past winter, I learned that some farmers for whom herbicide resistance had become unmanageable had reverted to inversion tilling. They basically plowed their land to put the troublesome weed-seedcontaining layer of soil 30 centimetres under. That allowed them to start fresh. If and when another inversion was required in the future, the weed seeds would have hopefully lost their viability.

Even if this were the answer, building up residue and organic matter after such a dramatic intervention and surviving erosion susceptibility would put the land in a vulnerable position in the meantime. A better way may indeed be to integrate all of our available tools and manage weeds in the long term.

Are You Creating a Legacy or Leaving a Liability? Do You Even Know?

By Nerissa McNaughton

Welcome to part three of seven. This series is designed to help every farmer with affordable, easy, hassle-free continuity planning.

Planning for farm succession is no easy feat. It’s an emotional, financial and logistical challenge that can leave families feeling stuck and unsure of where to begin. That’s where 33seven comes in. With a focus on farm continuity planning, 33seven helps farmers and their families smoothly transition their legacy to the next generation. Their tag line, ASK A FARMER WHO KNOWS ®, says it all. Founder and farmer Derryn Shrosbree started the company after witnessing the challenges his own family faced by overlooking continuity planning. Determined to help others avoid these pitfalls, he developed a plan that simplifies the process, ensuring your farm and family can thrive both now and for future generations. It all begins with understanding your farm’s value – and the factors that influence it.

Think for a moment about your children. You love them and want the best for them. You worked for years to help set them up for success. So, why would you go to the bank, take out a large loan in their name, and let them be surprised when you pass on and the hefty payments land in their lap?

“Nonsense!” you say. “I would never do that, and bank loans don’t work like that!”

Maybe not, but if you have not engaged in continuity planning for your farm, that is exactly what you have already done. From business debt to taxes to splitting the farm

“Here at 33seven, we strongly believe it is because billable hours and invoice fatigue are major obstacles to getting a succession, or continuity, plan in place.”

- Derryn Shrosbree

among beneficiaries, those liabilities don’t die when you do. If you have not planned for these contingencies while you are alive, then you are essentially undoing all the progress you wanted to hand over to your children.

In his decade plus of working with clients, mostly farmers, Shrosbree knows that about 88 per cent do not have a continuity plan.

“And why is that?” he notes. “Here at 33seven, we strongly believe it is because billable hours and invoice fatigue are major obstacles to getting a succession, or continuity, plan in place. It’s difficult enough to start – many farmers don’t know where to start. Then the bills pile up. Accountants, lawyers, consultants and none of them are talking to each other, creating an expensive pile of confusion. What farmer wants to deal with that when they can just go outside and plant canola?”

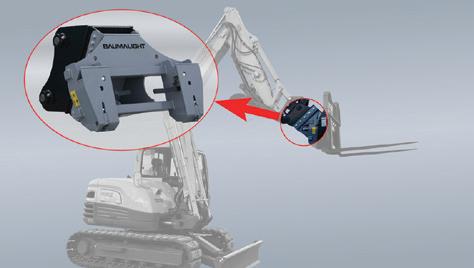

The roto telehandler introduces a whole new realm of opportunities by combining three machines into one with the maneuverability of a telehandler, reach and lifting capability of a crane, and access capacity of a MEWP .

HIGHLIGHTS

The roto telehandler introduces a whole new realm of opportunities by combining three machines into one with the maneuverability of a telehandler, reach and lifting capability of a crane, and access capacity of a MEWP .

■ Maximum capacity of 12,000 lbs and a maximum lift height of 83 ft 3 in

HIGHLIGHTS

■ Powered by a 145 hp JCB EcoMac engine - no DPF filters

■ Maximum capacity of 12,000 lbs and a maximum lift height of 83 ft 3 in

■ 4 scissor type outriggers with AUTO functions: deploy, retract and level

■ Powered by a 145 hp JCB EcoMac engine - no DPF filters

■ Dual seat mounted joysticks in large, ergonomic operator station

■ 4 scissor type outriggers with AUTO functions: deploy, retract and level

■ Dual seat mounted joysticks in large, ergonomic operator station

■ Load Management System (LMS) that displays capacities and limits; can be set for specific applicaiton situations

■ RFID attachments recognition corresponding with in-cab LMS system

■ LiveLink telematics for real-time machine data

■ Load Management System (LMS) that displays capacities and limits; can be set for specific applicaiton situations

■ RFID attachments recognition corresponding with in-cab LMS system

■ LiveLink telematics for real-time machine data

He continues with sobering statistics. “We see only about 12 per cent of farmers having a continuity plan and here is why this is a huge problem. According to Farm Credit Canada, $600 billion of net worth in the farming community will change hands in the next eight to 10 years; $528 billion does not have a continuity plan. That is a tsunami of tax coming down the pipe – for your beneficiaries.”

If you are working hard to create a legacy, don’t turn it into a liability.

Shrosbree adds, “Kicking the can down the road by planting canola and going to look after the cows – that’s great for the short term but ultimately, it’s not going to end well.

“Since farm and land value have gone up so much, the tax bill upon your death is now so high that the farm cannot go to a bank and borrow money to pay it. The other option is, do you want to sell acreage, a.k.a. your legacy? No farmer in the history of humankind ever wants to sell acreage!”

Make no mistake, the tsunami is coming. The average age of the long-term North American farmer is 60+, so if you don’t know anyone facing this issue at the moment – wait a year or two. It’s inevitable.

Shrosbree explains, “When they start dying, that’s when the tsunami comes and if they don’t do the planning and they die,

“When they start dying, that’s when the tsunami comes and if they don’t do the planning and they die, the tax bill accrues.”

- Derryn Shrosbree

the tax bill accrues.”

It’s not hopeless. 33Seven has a long-term solution that allows farmers to deal with one firm and avoid excess taxes, invoicing and all the fatigue that can come with continuity planning. It’s a solution heavily designed around and for farmers, created by a farmer who has lived through the disaster of what happens when the patriarch passes and the farm lands in limbo – with more than one sibling wanting to profit from it whether they have invested time and dollars into the farm or not. For Shrosbree, it’s deeply personal.

Here is how 33seven fixes the liability issue.

“For example, let’s consider a farm worth $10 million. If you have a $100 million farm, just extrapolate it by 10 and you’ll get the same numbers. Let’s say 50 per cent of that farm is

tax exempt. Let’s say you have an ice-cream shop, or a petting zoo or add roof trusses or something that’s nonrelated to the farming enterprise, that 50 per cent of your enterprise value is going to be taxed at your highest marginal tax rate. Upon death, your tax bill is around $1.25 million (25 per cent). Your legacy is $10 million, your liability is $1 million. If you die today, who writes the cheque for a million bucks?”

He admits the numbers make it sound easy. Hey, if the value is $10 million, the liability is manageable! Right?

Not really.

“I have not met that many farmers who have a million dollars just sitting in their chequing account. Most farmers are asset rich and cash poor. Therefore, that million dollars becomes a huge problem when you die, because now who’s paying the bill? Your children. Now the opportunities are limited because to raise the money the beneficiaries must sell acreage or accrue debt.”

Shrosbree cannot stress enough, “You have to plan ahead. Two bad options – you pay exorbitant tax and get invoice fatigue or your kids pay the liability in the end. One good option is you get a third party to pay the bill.”

Wait ... what?

He sighs, knowing that this is where most farmers give up.

“You have to plan ahead. Two bad options – you pay exorbitant tax and get invoice fatigue or your kids pay the liability in the end. One good option is you get a third party to pay the bill.”

- Derryn Shrosbree

“I’m going to say three words that people really don’t like, but we’re going to have to change that mentality. When they hear these words, most farmers would rather grab gasoline, pour it upon themselves and light themselves on fire; but it’s 2025 now so we’ve got to get with the program.”

Brace yourself for those three words. Are you ready?

“Leveraged life insurance.

“You, the farmer, goes out and buys a life insurance policy on your life paid for by the farm,” Shrosbree dives into the explanation. “Let’s say it’s a $100,000 premium. Farmers now lose their mind. They’re like, $100,000? I’m never paying that! Let’s just get over that – bear with me. Your farm pays the $100,000. We go to a bank or a credit union. We get you the $100,000 back because you borrow back the premium.

Therefore, you have the same amount of money in your account as when you started.

“You get your money back and you can go and use it for the farm purposes that you were going to use it for anyway. The cost of that is the net interest expense on the loan. The loan is, on average, net interest 2.5 per cent. It’s $2,500 a year and you’ve just saved yourself a million-dollar problem. That’s $200 ($2,500 divided by 12 is $200) a month. For $200 a month, you’ve just made sure that your entire farm moves from your generation to your children’s generation with zero tax implications for $200 a month. That sounds like a great deal to me. When the referred are gone, your on-farm and off-farm children will still have supper together.

“We have two transactions. One is leverage. One is insurance. Combine them and you get to keep your farm. Put away that gasoline! We have a solution for you. Don’t worry about it. You’re going to be OK. That’s what we do; solve your estate problem, maintain the farm liquidity, prevent the beneficiaries from having a liability and it’s only costing you $200 bucks a month.”

Shrosbree concludes, “At 33seven, we bring clarity, control and a farmer’s perspective to every transition we guide. Take the first step today and start securing a future your family can be proud of for generations to come.”

This is the third instalment of a seven-part series designed to provide you with the tools and insights needed for seamless farm continuity. With the right plan, your family’s legacy will remain strong and conflicts can be avoided. Stay tuned for part four and explore more at www.33seven.ca.

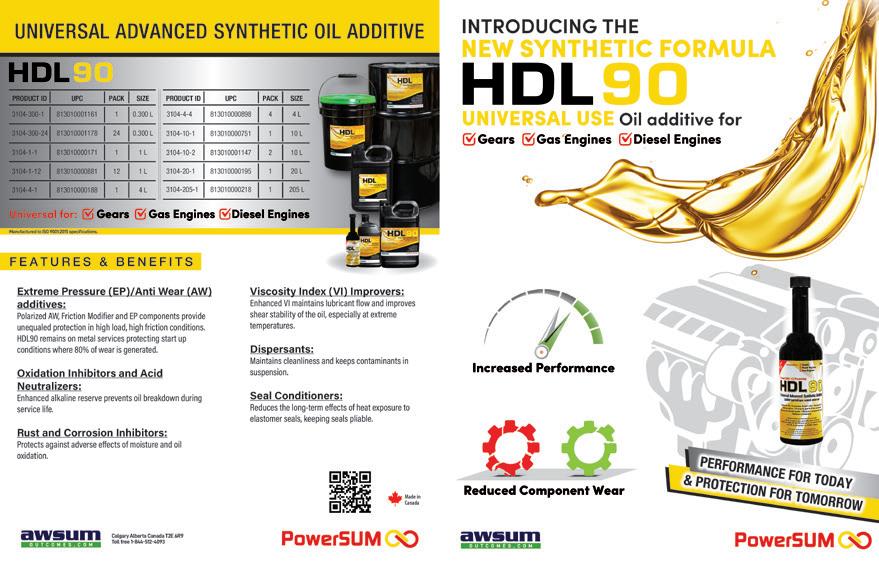

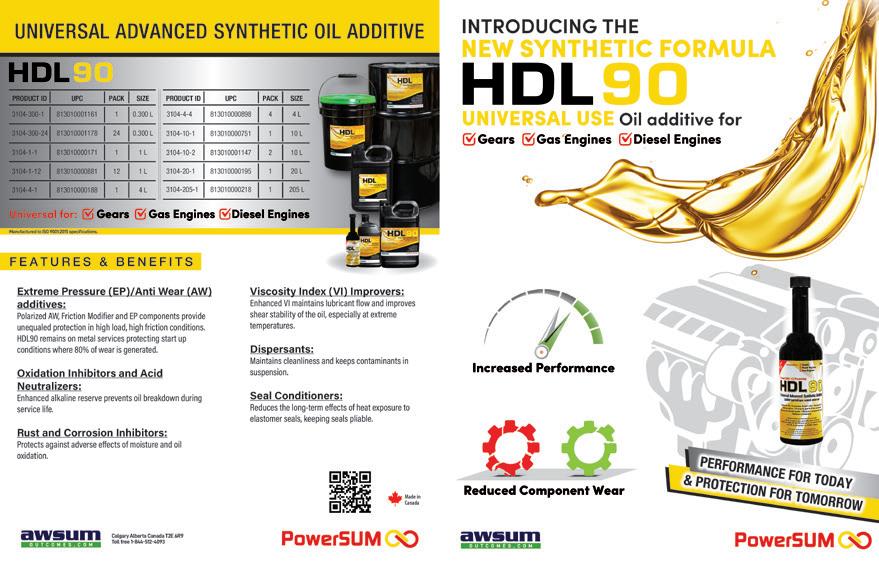

By “Farm Boy” Warren Coates

Most greases are composed of approximately 70% base oil, 25% thickener (soap), and 5% additives. Lithium-based greases dominate the market because they are cheap and easy to find—but cheaper isn’t always better! In the 1990s, some innovative Alberta farmers started blending calcium sulfonate oil additives into conventional grease. The result? — a superior, thixotropic calcium sulfonate grease. This is the heritage of ThixoSUM2 from Alberta-based PowerSUM. Thixotropic means it can return to its original state after mechanical stress, making it last longer under heat, pressure, and vibration.

Compared to conventional lithium grease, ThixoSUM2 resists water, won’t separate under pressure, and holds its form. It maintains better boundary lubrication and helps reduce wear in high-stress applications like on the rotor bearings (main and front rotor support), for example, on the ever-popular John Deere S690 combine and other great harvesting equipment.

Some nerdy stuff: the “ASTM D2596 — Four-Ball EP Weld Load test” is a standardized method used to evaluate the extreme pressure performance of lubricating greases, particularly their ability to protect metal surfaces under high-stress conditions. ThixoSUM2 stacks up better on this measure against greases that PowerSUM has evaluated.

Farm Boy Math - The big cost is not the tube of grease.

If we accept that the bearing assemblies can cost $1,000 each (including OEM part and installation labour) and that calcium sulfonate extends its life by even 50% then a $1,000 bearing assembly effectively costs $500, over a longer life vs. using standard lithium based grease products, resulting in a total savings of $1,000 for the two primary rotary bearings on a combine. And that’s just for one set of bearings. Add in the bearing assemblies for the straw chopper, auger, feeder, and cleaning fans, and then the savings grow with the use of a superior grease. Always confirm that the grease you use meets your manufacturer’s specifications.

Bottom line? ThixoSUM2 may cost more per tube, but it delivers real-world savings in labour, repairs, and downtime. In larger operations, that could mean tens of thousands in savings. And remember Downtime is not a Good Time—especially if it’s going to rain or hail!

For hydraulic systems and automatic transmissions with appropriate

viscosity specified by the OEM; Synthetic or conventional. Must be

Use promo code PowerSUM0825 for a 10% discount

and Conditions

Check our products out at: https://awsum.global Or contact us for more info: info@awsum.global