HOPE a poem

MUSINGS FROM NORAH reasons for hope

WHAT THEY HOPE FOR the voices of youth

NOT ALL ABUSE IS PHYSICAL a story of survival

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN RURAL ONTARIO

THE POWERFUL ART OF QUILTING

Sandy Proudfoot’s art

SEPTEMBER 2023

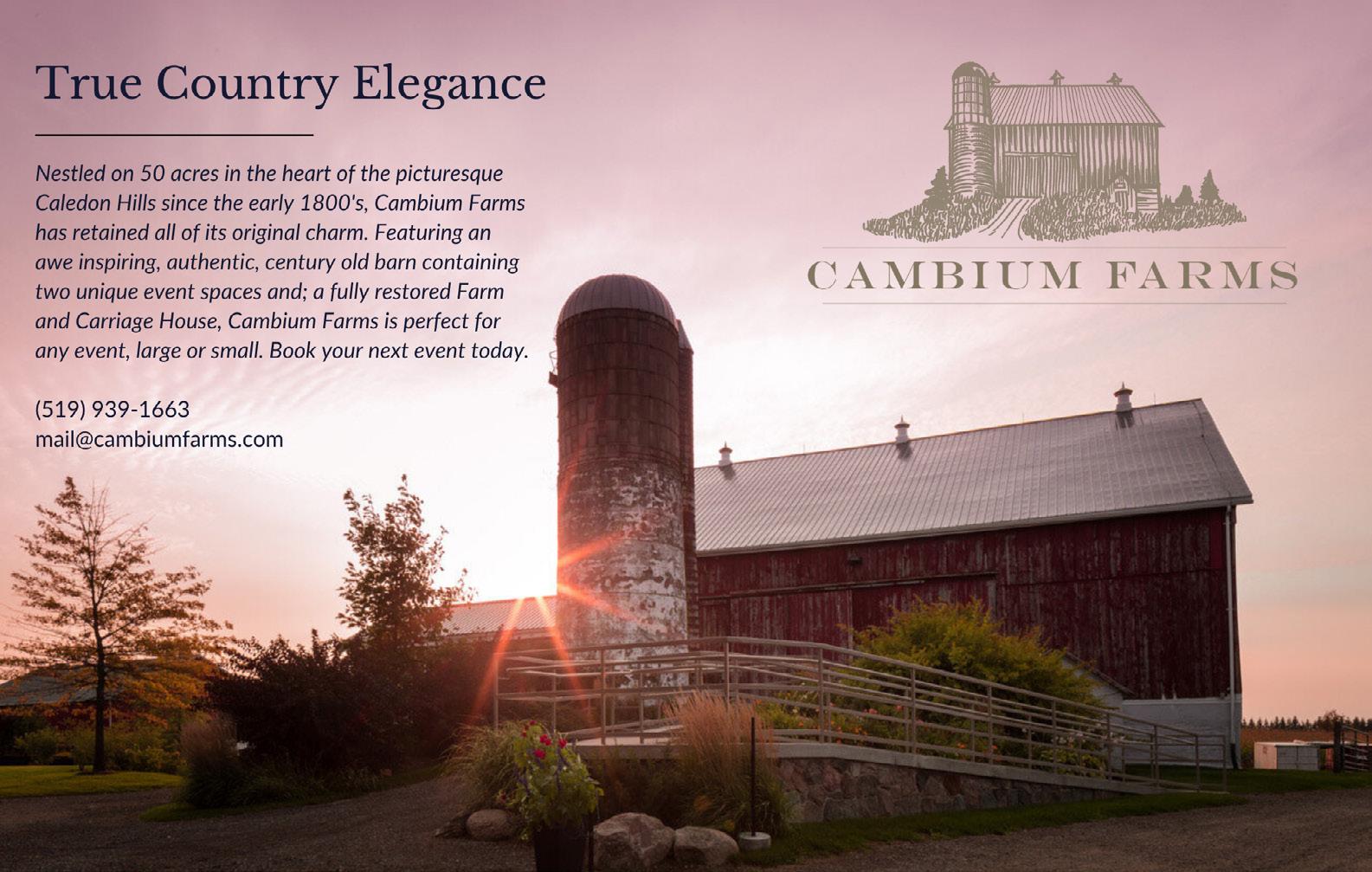

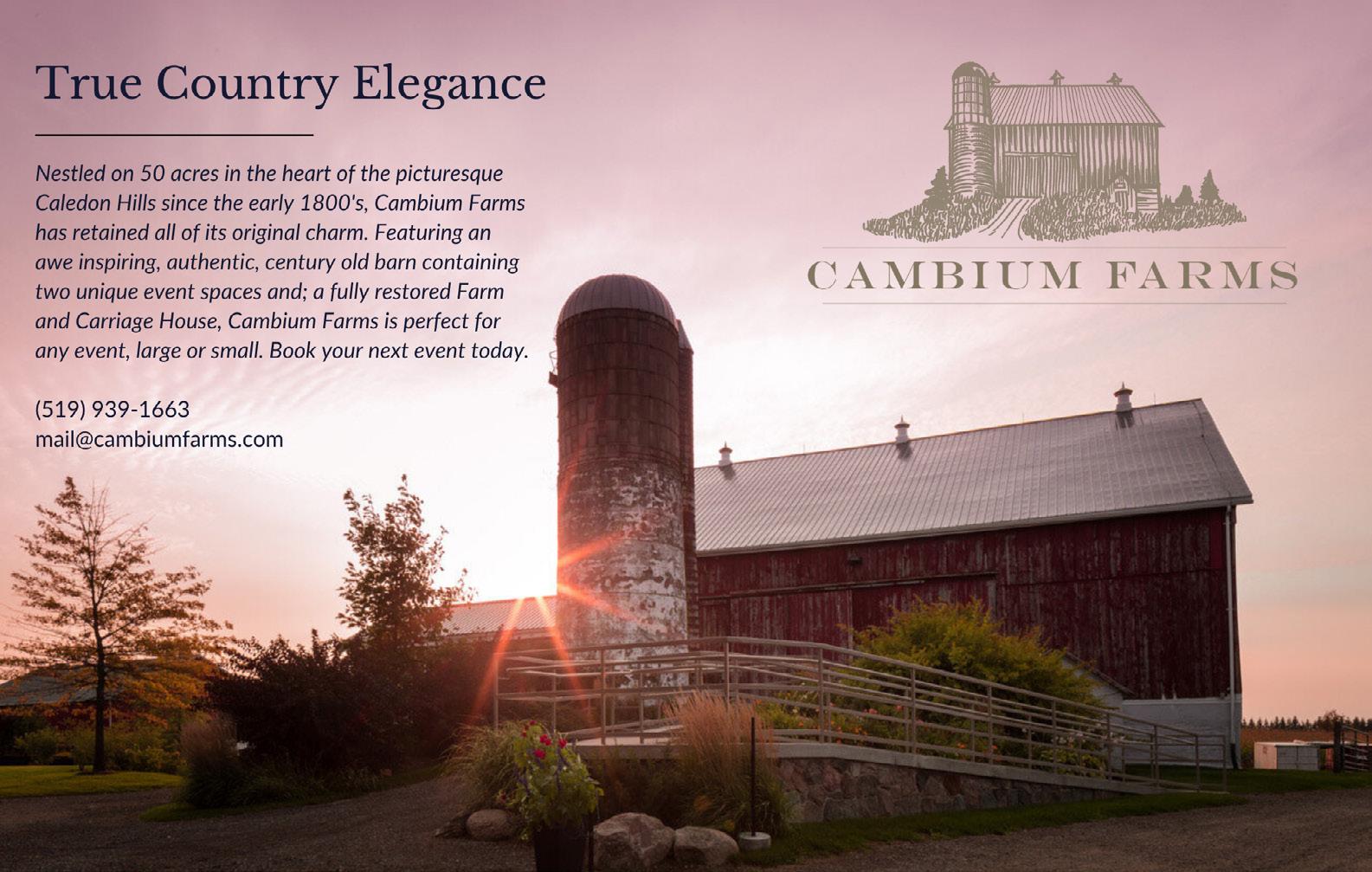

Start planning ahead for next year’s events!

Naydo's Potatoes is a full service, mobile French Fry and Poutine truck serving Erin and surrounding areas.

What’s inside

Let’s talk about hope.

5 HOPE BY BRENNAN SOLECKY A poem about hope.

6 MUSINGS FROM NORAH

14

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN RURAL ONTARIO

BY RACHEL TELFORD,

BY RACHEL TELFORD,

16

BY

NORAH KENNEDY Reasons for hope— in spite of flawed systems.

8

WHAT THEY HOPE FOR

BY TRAVIS GREENLEY

The young people of our community have many hopes.

10

NOT ALL ABUSE IS PHYSICAL BY TABITHA WELLS A story of survival, healing and hope.

THE POWERFUL ART OF QUILTING

BY TABITHA WELLS

Quilter Sandy Proudfoot speaks volumes with her quilts.

“The very least you can do in your life is figure out what you hope for. And the most you can do is live inside that hope. Not admire it from a distance but live right in it, under its roof.” ~ Barbara Kingsolver

hope 3

{ {

ONTARIO GRAIN FARMER Support for rural women and families.

KELLY LEE Copy editor LIESJE DOLDERSUM Art director IMAGES Stock / provided

Hope

A poem. by Brennan Solecky

We have to hold onto hope, they say Well, that’s easier said than done. Our crisis calls are rising, One by desperate one.

Our shelter beds are full, And we have endless requests for room, We’ve got women and children needing shelter And know space won’t open up soon.

The housing crisis is real, There’s nowhere for people to go The prices are too high, rooms aren’t safe Clients need answers other than “no”.

The kids in schools are struggling. The pandemic has set them back. Our Youth Educators tirelessly strive To guide them back on track.

We have to hold onto hope, they say You must be kidding – what’s the use? Local overdose deaths are climbing So are rates of substance abuse.

Mental health concerns are growing People are trying to cope Our counsellors’ jobs are getting harder But still, they say – have hope!

The Femicide List is growing, Women and girls who’ve lost their lives 38 once glowing hearts now dim, Daughters, grandmas, aunts, moms and wives.

That’s not a problem in Canada, they say Not in this city, not in my town. This belief is flawed and wrong, Femicide rates aren’t going down.

We have to hold onto hope, they say Then, they overturn Roe v. Wade? A woman’s choice and autonomy ripped away By men, these decisions were made.

It’s easy to be quick to anger, When oppression, misogyny and ignorance run free When it feels like we’re going backwards Aren’t we in 2023!?

Hope feels fleeting at best When we look at our current state But losing hope won’t help us We know the risks are too great.

With rising demands for service and space, We know we can’t give up. Our community needs us more than ever now. Our community needs more love.

We continue to champion and advocate For progress and funding and change The fact that disparities and inequalities still exist Is wrong, and criminal and strange.

Whenever there’s a crisis Thankfully, the government steps right in. With emergency funding, grants and support Until these resources run thin.

Community has meant more than ever this year Donations, time and support We’ve counted on our donor family When funds and hope came up short.

We have to hold onto hope, they say You know – I think that might be true. We’ve got women and children relying on us, There’s no shortage of work to do.

Hope will keep us going Hope will keep us strong When everything in this world, Feels like it’s going wrong.

Hope will keep us humble Hope will keep us alive Hope will give us the will to go on, With hope, together we’ll thrive.

We will hold onto hope, I say For each person that comes through our door. Because as long as there is hope, Each new day can be better than those before.

Brennan Solecky is FTP’s Director of Development & Community Engagement

Musings from Norah

by Norah Kennedy, Executive Director, Family Transition Place (FTP)

A young woman sitting on the curb in front of my office the other night wished me “an amazing evening” as I left work for the day. I smiled, touched by her greeting, and wished her the same. She laughed. It was a deep, guttural, soul destroying laugh filled with a hopelessness so deep it broke my heart.

Two other women discharged—separately—from the shelter recently—to live in tents. What are their choices? On Ontario Works, the $735 a month allowance doesn’t even cover half the cost of a one-bedroom apartment in our community, let alone leave enough for food.

One of our youth educators told me about a student in one of their classes who uses two different names—one at home and another at school—because they don’t feel they can be who they want to be with their family.

Just the other day, the CEO of another organization made a comment that “everyone is angry and frightened.” If this is true, how then do you create a healthy, safe community for anyone?

If you’ve been feeling insecure and unsettled lately, you’re not alone.

hope 6

Norah Kennedy. Photo by Sharyn Ayliffe

“From rising inequality and declining mental health to climate change disasters and the threat of authoritarianism, insecurity has become a “defining feature of our time,” says this year’s CBC Massey lecturer, Astra Taylor1

We often think of insecurity as tied to issues that face the most vulnerable of us: job insecurity, food insecurity, housing insecurity. Those of us fortunate enough to have “secure” jobs, a “stable” home and enough food to eat consider ourselves “secure,” as though that is a state of permanence and constancy.

However, we know that these very issues are being faced by many who, as recently as a year or two ago, would have considered themselves “secure.” Our local food bank reports a significant increase in service users who— on the surface—appear to be “middle class,” but are now struggling financially to manage basic needs. It isn’t just the poor or destitute who can’t afford homes anymore—ask anyone in the current generation of young adults if they expect to own their own home. (Spoiler alert: they don’t.)

There is a broader feeling of anxiety and insecurity infecting our entire society.

When feelings of insecurity or anxiety manifest, we are often advised to turn to stress reduction and self-care techniques to help cope. Trust me, I love a good massage—and a few deep breaths do help get me through some stressful moments—but this level of existential anxiety goes far beyond a bubble bath and deep breathing. Taylor says, “We all need a bit of self-care, but you can’t meditate your way or exfoliate your way out of this crisis.” (Taylor, 2023)

ing us, but this is a magazine about hope, so I will forgo that, for the moment.

Because, in the face of it all, I do believe there is hope. I believe there is hope for the young woman who can’t imagine what an “amazing evening” could possibly look like. I believe there is hope for the MANY people who are sleeping in tents, or on the street, or in shelters. I believe there is hope for the youth who want to live to be their true selves but are too afraid.

Hope comes from the point at which there is a collective realization that our systems are seriously flawed. They were established to work independently from each other, although in reality, they are inextricably entwined. Climate change and care for our planet is not an issue that is independent of everything else. It is the foundation of life on this planet. Health cannot be separated from education and education only succeeds when people are housed and fed, healthy and safe. People will only be safe when there is equity between genders, cultures and identities. Government is only successful when it really listens to the people it represents and truly understands their experiences.

at which there is a collective realization that our systems are seriously flawed. They were established to work independently from each other, although in reality, they are inextricably entwined.

From this realization comes the ability to see the human condition as a whole, not as something to be splintered into funding silos or highly sectored expertise. “This is absolutely a structural, social and political phenomenon. And that means that we can only actually address it through collective structural solutions.” (Taylor, 2023)

(I love the line: “…you can’t exfoliate yourself out of this crisis.”! I wish I could shed my stress with a good loofa!)

The need for “collective structural solutions” (Taylor, 2023) is intense. Our systems were created to be copies of systems designed centuries ago on other continents by those who had no other frame of reference than colonialism, white supremacy and patriarchy. Those systems stand intact today, although we know they are not serving us well.

Well, let me qualify that: they are serving a few of us very well, and the majority not well at all.

I could dive into each system (health, social services, education, government, etc.) and explore where and how each is fail-

Our human condition is intersectional at its essence. We are the sum of our parts.

When we see across systems—to integrate, understand and dismantle—there is hope of creating real community. Real community means that we take care of each other, in all our human messiness, so that not one person is left out.

~ Norah

1 Manasan, A. (2023, July 11). Forget self-care. To feel better in this world, we need collective action, says Massey lecturer Astra Taylor. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/cbc-massey-lectures2023-astra-taylor-1.6886197

hope 7

Hope comes from the point

What they hope for

“I hope the war in Ukraine ends.”

“I hope my dad gets another job soon.”

“I hope the pandemic is over and we won’t have to go back to online learning again.”

“I hope that we will have enough money to pay this month’s rent.”

“I hope my mom doesn’t feel so sad all the time.”

“I hope the wildfires get put out.”

These are just a few of hopes that the young people of our community have shared with Family Transition Place (FTP) Youth Educators during the past year. As we all know, the world changed very quickly in the spring of 2020 and our children were not immune to the impact of those changes. Children have experienced upheaval and trauma on a scale rarely,

if ever, seen before. They were forced to stay away from friends and family, learn from behind a computer screen, miss important once-in-a-lifetime milestones and watch as the world figuratively and literally burned.

No person, let alone a child, should ever have to witness events like the ones that have taken place in the last few years. But the truth is, our children have watched, listened and absorbed these traumatic events. They’ve done this without the long runway of life experiences that adults have. So, while adults can lean on their history to tell them that things can get better, our children simply need to take our word for it. These circumstances have led to a population of young people who, while eager to return to what is considered a “normal” childhood, aren’t really prepared for what that means.

hope 8

The young people of our community have many hopes. by Travis Greenley

After two plus years of virtual learning we are now sending our children back to school to do “actual” learning. That means, leaving the safety and security of their homes where they often learned by themselves and without a lot of structure, to a scheduled school day full of different people and personalities.

Returning to school goes well beyond reading, writing and mathematics, in which many young people have fallen behind. This “actual” learning also extends into socialization, empathy and self-esteem. The gap in these learned skills has created crisis situations in many schools with angry outbursts, dysfunctional classroom dynamics and far too many students struggling to cope with their new seemingly “normal” childhood.

Unfortunately, based on 16 years of experience gained in local schools, I have to report that things are anything but normal. FTP is seeing the lowest self-esteem, empathy, and self-efficacy scores we’ve seen in our program’s history.

This is backed up by the increase in the aggressive and sometimes violent behaviours we are seeing in schools. The youth who are acting out are not choosing this path. It comes from the years of trauma combined with the lack of practical life experiences that act as a young person’s teacher as they grow up.

While the picture I’m painting of our local schools may seem bleak, it’s actually quite the opposite.

The schools are teeming with potential, possibility and thousands of resilient children who want to learn how to become the best versions of themselves. They are surrounded by compassionate and caring educators that work every day to help students reach their full potential.

Our schools are simply a microcosm of the world at large and just like the world, for every negative there are countless positives. I have had the privilege of witnessing many of those positives over the last 18 months.

Since FTP Youth Education programs have returned to in-person learning, the results have been remarkable. Students who had participated in FTP programs before pandemic lockdowns, welcomed us back into their classroom like an old friend who had been away for far too long. They reengaged in discussions and games with a newly charged social conscious derived from what many of us around the world had learned during the pandemic. But, to watch a 12-year-old share their thoughts on social injustices and what they want their world to look like in the future left me with goosebumps and hope.

New students to our programs often show trepidation and nervousness. This is to be expected and is natural when meeting someone new who wants to help make their classroom a safer and more comfortable space. But it didn’t take long for our new

friends to embrace FTP as an integral part of their school week. Many times we heard shouts of joy from the students like:

“Monday’s are my favourite because FTP is here!”

“That was actually way more fun that I thought it would be.”

“Our class feels happier on days that FTP comes to our school.”

I have seen students (whose attendance at school is sporadic at best) ensure they’re at school every day the FTP program is in their classroom. I have witnessed disruptive and, at times, disrespectful classes engage in real conversations about how to change things…and then actually do it. I have seen students who have been struggling with their mental health for far too many months (or years) finally reach out and get the help they need.

You see, the most remarkable moments occur when things seem like they’re at their worst. Children will seek out a bright light when things are dark and for some of them, FTP has been that bright light on difficult school days.

So, while working in schools is more challenging right now, our work is more important than ever. Just like “A river cuts through rock not because of its power but because of its persistence,” FTP persists.

For over 20 years, FTP has been working to build healthier communities, one classroom (one student) at a time. It’s not a quick fix, it’s a generational shift. With help from our generous donors who support these programs, and the local schools that welcome us through their doors, this generational shift can continue year after year.

That leads me to sharing one final hope that countless students have shared with FTP’s youth educators over the past school year…

“I sure hope I have you in my class again next year.”

Thankfully, that is one hope we can make come true. We will be back in their classroom next year and the year after that. The work doesn’t end because it gets more difficult, it just becomes more critical that it gets done.

Since FTP’s Youth Education Program began in 2001, more than 60,000 students and over 40 schools have benefited from these skill-building, attitude changing programs, which run primarily on fundraised dollars and a cost recovery model developed for participating schools in Dufferin and Caledon.

Travis Greenley has taught leading-edge healthy relationship strategies to more than 60,000 kids (and counting) over the last 16 years. Travis has also spoken to countless adults across multiple platforms on many topics. He published a book in 2019 entitled “A Walk in Her Shoes – One Man’s Journey into Feminism.”

hope 9

...to watch a 12-year-old share their thoughts on social injustices and what they want their world to look like in the future left me with goosebumps and hope.

Not all abuse is physical

by Tabitha Wells

Julie Thurgood-Burnett is well-known in the Dufferin community as an entrepreneur and supporter of many local initiatives and organizations, including being a longtime supporter of Family Transition Place (FTP). She is fiercely independent, bold, passionate, ambitious, kind, supportive—a powerhouse of a person.

What is less well-known, in fact, not known by many at all, is that many years ago, Julie experienced domestic violence. In the hopes of helping other women recognize if

they are in similar situations, she decided to speak up and share her story.

Julie didn’t recognize, or want to admit, her relationship was abusive. After all, she had always been independent, strong, someone who got through things and was level-headed.

Often, when people think of domestic violence and intimate partner violence (IPV), it’s the most physical examples that come to mind. The ones that leave physical bruises, scars, and broken bones.

hope 10

A story of survival, healing and hope.

Julie Thurgood-Burnett. Photo by Love is Photography

But in many instances, domestic violence is invisible, veiled, and happening without being realized. People tend to overlook the mental and emotional elements of abuse if they themselves have no experience with domestic violence or IPV scenarios.

For Julie, the lack of physical abuse played a part in why she didn’t fully accept or recognize it for so long.

“I was young, and I was brought up in a very happy household—I was surprised I allowed myself to be in that situation,” Julie explained. “But it never starts out like that. My relationship started out good; he was a drinker, but at that age, most people are. It wasn’t something anyone saw as a problem. Everyone is partying and doing whatever.”

The earliest red flags in the relationship came from her partner cheating.

“I got out, and then, for some reason, I took him back,” said Julie. “It all went downhill from there.”

He never physically hurt Julie. It was the mental abuse, the drinking and the drugs, and everything was always in constant upheaval around her. Things escalated until one night, in a drunken stupor, he came close to killing her. Julie had awoken him in the middle of the night after he wet the bed, passed out drunk, and as she describes it, madness ensued.

“We lived in one of those 1970s style houses, where you can enter the room from one door, and go out the other, and there’s this little alcove,” Julie explained. “I stood there, and he went around me eight times with a knife in his hand.”

Her partner’s sister lived upstairs and called their father to come for help—when the father arrived, Julie’s partner tried to stab his dad through the window.

“When he was circling me, he didn’t see me standing there—I don’t know how he didn’t. I have absolutely no doubt if he had, he would have killed me,” said Julie. “I remember feeling the breeze of him moving past me.”

It took four years before Julie was able to get the courage to leave. With $25 in her pocket, she packed her stuff and told him she was moving in with her brother.

“I am and always have been very strong, very determined, and I don’t take a lot of bullshit from anyone,” said Julie. “So when I look back at who I was back then, I don’t understand it. But it was all mental abuse—and it was mental abuse in the next relationship.”

Julie has said she often wonders how she ended up in those situations, and a lot of it, she feels, comes back to a combination of not knowing what to watch for with mental abuse and a trap that many women fall into—a lack of self-value.

“As women, I think we sometimes don’t see our worth; when we end up in a place where someone is constantly putting us down, we think we belong there, or that it will eventually get better,” shared Julie. “We get raised as women to make things better, so we think magically it’s going to get better, but it really isn’t.”

Everything was a fight in the next relationship, a manipulation, control, combined with narcissism and alcoholism. Julie shared how often her partner would put her down or work to make her feel guilty for achieving success.

“He never touched me—mental abuse, it’s a different kind of war. I didn’t walk around with bruises or anything, but it was the mentality,” said Julie. “It was the constant fights, constantly being put down, the cheating, being made to feel like you don’t matter.”

She added that in her situation, she often came up with reasons why it wasn’t as bad, but when it comes to it, everything came back to a common thread in many domestic violence scenarios—finances, a fear of being alone, and a place to live.

At the time, she didn’t know about FTP and other organizations like it. Despite having nowhere to go, like the first time, she got the courage and strength to leave.

“Things have come a long way since then,” Julie shared, “and if you’re in that scenario, there is a way out.”

As Julie reflected on her experience, she shared that it has encouraged her over the years to make sure her kids are prepared for feeling strong enough and supported enough—she’s taught them about strong boundaries, being able to say no, and being able to change one’s mind.

“My daughter, I love how strong her boundaries are,” said Julie. “I think about how, if these are her boundaries already at 15, they’re going to take her so far. And I don’t think we were taught boundaries like that growing up, and they’re needed.”

For any who may resonate with Julie’s story, or find themselves in a similar position, Julie hopes they find the strength to leave and find help and support.

“There’s going to be moments when you’re halfway out and you’re like ‘holy shit, I don’t think I can do this.’ But it does get better—there is a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Tabitha Wells is a writer, wife and mom based out of Dufferin County. A former journalist, she enjoys writing about social issues and challenging people to inspire and work towards change. Tabitha also contributed the story about Sandy Proudfoot and her powerful artwork on page 16.

hope 11

“...mental abuse, it’s a different kind of war. I didn’t walk around with bruises or anything, but it was the mentality... being made to feel like you don’t matter.”

Domestic violence in rural Ontario

Support

for women and families.

by Rachel Telford, Ontario Grain Farmer

You are worthy of a healthy relationship. That may seem like an obvious statement, but thousands of women stay in relationships where they are subject to verbal, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. Domestic violence is an epidemic in Canada—and violent incidents are even more prevalent in rural areas than urban centres. Once in an unhealthy relationship, it is often difficult to leave.

“There are ‘traps’ for women that are unique to rural areas, such as the physical isolation and the lack of transportation,” says Keely Horan, who works as a counsellor with

Family Transition Place’s Rural Response program based in Dufferin County. “There is also the sense of everybody knows everybody, which creates a lack of privacy and the fear of victim blaming.”

The statistics

In 2022, the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics (a division of Statistics Canada) issued a report to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women. It highlighted the rural rate of reported intimate partner violence against women to be

hope 14

598 per 100,000 population in Ontario. That compares to 378 per 100,000 population in urban locations. Even higher rates were seen across the Prairies and the Territories.

The statistics, however, don’t reveal the entire story. Many incidents go unreported, and as was flagged in the report, some of the most common forms of abuse—emotional, verbal, and financial—do not meet the criminal threshold and are not monitored.

On the farm

Within farm families, Horan notes that finances are often one of the key factors influencing a woman’s decision to stay in the relationship. In situations where they don’t have any control over their finances, they worry about a lack of funds to support themselves and their children if they leave. In situations where they are joint partners, they stand to lose a massive financial interest.

There is also pressure to preserve the inheritance of the property along with the family’s reputation.

“Moms specifically worry that they are the ones breaking up the family. And they feel they may not be able to provide as much to their children as they currently have,” says Andrea Chantree, a rural response counsellor at Family Transition Place. She adds that it can be difficult to see through the ‘mom guilt’ and recognize that living with fewer things is better than an unhealthy home environment.

Once a woman reaches out for help, leaving may not be the immediate answer. In fact, there could be several attempts before a woman leaves successfully.

Developing a safety plan is key because leaving often puts the woman at higher risk for escalated violence, including homicide. Every safety plan is different based on risk and the age and socio-economic status of the woman. It can involve elements such as having a neighbour to go to, keeping your cell phone charged, and knowing whether or not you are willing to call 911 if the situation escalates.

Lack of services

It’s also a reality for many that leaving isn’t the answer because there is nowhere else to go—shelters are often at full capacity, and they don’t have family or friends to go to. It is also common for farm women to stay in an abusive situation because they feel responsible for protecting livestock and their pets.

“There is a strong link between domestic violence and animal abuse,” says Horan. “Pets and farm animals are often threatened, harmed, or neglected as a means of controlling women.”

The Rural Response program gives Horan and Chantree the unique opportunity to support women however they can—

going to their homes if it is safe to do so, meeting them in the community, or even accompanying them to doctor appointments. They provide counselling on what is a healthy relationship and refer clients to additional services they may need.

They also ensure the woman feels heard and validated.

“We are not sitting in judgment,” emphasizes Chantree. “We try and understand why they are reaching out and what they hope we can provide them. A lot of women are just looking for someone safe to talk to, who won’t give them unwanted or dangerous advice.”

The Rural Response counsellors will also offer advice, provide guidelines for developing a safety plan, and refer support services to anyone trying to figure out how to help a woman who they believe is being abused. Common emotional and physical signs of domestic abuse include not showing up for work, isolation from friends and family, visible injuries, and waning confidence.

It’s important not to put the abused at further risk. If there is imminent danger, the police should be called immediately.

Supporting victims

“If you find yourself in a support role, recognize that you are not the only person who can provide that support,” says Horan.

“Express your concern in a gentle way and support their decisions to find help options specific to their needs. It can be frustrating to support someone in an unhealthy relationship because you may not understand why they just don’t leave.”

Everyone has a role to play in ending domestic violence. Understanding its prevalence within our rural communities is the first step in working towards healthier relationships and lives free from violence.

Keely Horan and Andrea Chantree will be guest speakers at the 2023 Women’s Grain Symposium, taking place November 27-28 in Guelph. For more information and to register, go to www.gfo.ca/womens-symposium.

hope 15

“There are ‘traps’ for women that are unique to rural areas, such as the physical isolation and the lack of transportation.”

The powerful art of quilting

Like many forms of art, quilting is about more than patterns and pieces of cloth stitched together. Quilts can be beautiful tapestries, a mosaic of colours, images and more. But, like other forms of art, it can also be used to tell a powerful story—one that drives home a message within its beauty.

Earlier this year, Sandy Proudfoot of Mono donated one of her quilts to Family Transition Place (FTP) to raffle off—a way to show her support and help reinforce FTP’s messaging on domestic and intimate partner violence. Another quilt is to follow in January 2024.

“Using quilts to make a statement about domestic violence is an unusual approach,” explained Sandy. “I hope it makes people more aware of the reality many people experience—they’ll never fully understand that reality without experiencing it but it can make them more aware.”

Sandy is more than just a skilled quilter. After starting a quilting program at Humber College in the 1970s, Sandy was encouraged to apply to art school ten years later, when in her forties.

“I was 43; after objecting so strenuously when the idea was pre-

sented on Sunday afternoon, when I got up Monday morning I thought ‘I don’t want to end up on my deathbed thinking about all the opportunities that I might have taken and let pass by’,” Sandy shared.

That very morning, Sandy called the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD) and found out those were the only two weeks they were taking interviews for their fine arts program. She showed up to the interviews amidst a crowd of young art hopefuls with black art portfolios and her quilts in a green garbage bag. In her initial interviews, she met with the head of the design department who told her immediately she belonged at OCAD.

“She looked at my quilt—she was an architect—and she said, ‘oh, they’re just beautiful, they’re quilted tapestries’,” explained Sandy. “She said she’d put me in second year advanced as I already had my medium—textiles.”

Sandy lives in Mono, Ontario in a beautiful home featuring a quaint, quiet porch that looks out over her property and the forest around her. It is a place for conversations and the inspiration behind her latest statement quilt—a portrait of herself and a close

hope 16

Artist Sandy Proudfoot shares stories and messages of healing in her quilts. by Tabitha Wells

Sandy Proudfoot on the porch of her home—the inspiration behind her latest quilt, The Porch: Opening the Door to Recovery (shown in inset photo). Photos by Mary Light

friend talking as Sandy pursues her own journey of healing.

Sandy is one of the many people who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV), something which has played a major role in her advocacy against violence and support of FTP.

The Porch: Opening the Door to Recovery is a follow-up piece to her first statement quilt, Coercive Control, promoting the idea of hope and renewal through counselling, connecting with others who have experienced abuse, and women’s shelters that provide a safe-haven.

In her artist’s statement, Sandy writes, “Upon the porch sits two chairs, one for the abused, one for the support offered by those who help guide us through this process. Reaching out for help, we can open the doorway to recovery. The black clouds of grief, of loneliness, of fear and of pain gather above and lie heavily upon the victims of domestic violence wondering what lies ahead. Yet, within that grief lies hope for survival. An explosion of brightly coloured flowers, inspired by the artwork of Canadian Métis artist, Kristi Belcourt, represent the hope of a better future, spilling out of those dark clouds, the door opens. If we survived the abuse, we will survive the recovery. But we will never forget.”

Sandy describes domestic and IPV as an insidious and serious issue in society today. Partners use coercive control, often long before things become violent, making people feel too afraid to leave, or speak up; for fear of being hurt, of children being impacted, of upsetting their partner.

Abusers, Sandy notes, depend on that. On the coercive control and the act, making it seem as though the victim is blowing things out of proportion. The one perpetuating the violence puts on a carefully cultivated performance to those outside the home—the violence is often only visible behind closed doors.

“It took me 21 years to admit I was in an abusive marriage,” said Sandy. “It wasn’t constant and it started like much domestic violence does—with control. But when he became very angry with me, as I had been assaulted physically three times before, it was not safe for me to continue living with it. It was a heartbreaking decision for me to call the police and not something I will ever forget. The hard part is that you don’t always stop loving the person who has been abusing you but at some point it has to end.”

Many victims will note that one question they are often asked is ‘why did you stay so long’ or ‘why didn’t you deal with it,’ but of course, the answer isn’t quite so simple—neither is the option of immediately leaving or dealing with it.

“First of all, you don’t want to admit this is happening, you want to carry on with your life,” explained Sandy. “And that’s what I did for a number of years. Then, when you finally admit it is one thing. To do something about it is another. Many if not all victims are financially compromised by their abusive partners.”

As she channels her own story and advocacy into these statement quilts, Sandy hopes people will start to grasp just how multifaceted this issue is— and how much work needs to be done to stop it.

“I hope that they see my quilts and wonder ‘what the heck is she doing with this imagery’ and are driven to read the artist’s statement, so that they understand the story it is telling,” said Sandy. “When people see The Porch, I hope they will know it’s okay, they will get through this, and that recovery through therapy is possible. There are still days I feel sad, or angry, or down in the dumps, but the help I’ve received from Family Transition

hope 17

Place and my close friends along with my quilts, help me to process it.”

Two more of Sandy’s incredible quilts. Above: Coercive Control Below: Travelling the Silk Road Photos on this page by Pete Paterson

It’s Our Service that sets us apart!

For over 50 years, our families have provided electrical services to the Dufferin & Peel Region area’s homes, businesses, and industrial sites.

31 Simpson Road, Bolton (905) 857-8044 www.wsisign.com Proud Supporter of our Community Premier manufacturer of high quality Architectural Signage. WSI sign.indd 1 17/09/2015 5:56:02 PM 905.857.6981 • 800.263.2394 • www.cavalier.ca First out of the gate... and across the finish line. A proud supporter of Family Transition Place. T: Orangeville 519 942 0921 • Caledon 905 843 2358

The Lotus Centre—a program offered by Family Transition Place (FTP)—provides sexual violence counselling and support for individuals (16+ years old) in Dufferin County and Caledon who have experienced past or present-day sexual violence. Counselling is also available to the partners, family members and friends of those who have been subjected to sexual violence. Counselling services are available in Orangeville, Bolton and Shelburne.

www.familytransitionplace.ca FTP works with the

to deliver sexual violence

across our community: Child and youth services Emergency medical and crisis services FTP is a member of the Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres. 519-941-4357 | 905-584-4357 | 1-800-265-9178 Lotus Centre Sexual Violence Counselling and Support We believe you. A program of

services are FREE.

following partners

supports

All

20 Bredin Parkway, Orangeville, ON L9W 4Z9

Proud supporters of Family Transition Place

VISIT US AT 125 BROADWAY IN ORANGEVILLE

BY RACHEL TELFORD,

BY RACHEL TELFORD,