ACHIEVING EXCELLENCE

SPRING 2025 / CONTENTS

FEATURES

Curiosity and hard work earn students accolades in computer science, math, music and more.

Adam Loyd and Sarah Pruitt ’95

30 Artificial Intelligence

Alumni share how technology is reshaping everything we do.

Debbie Kane

36 History in Focus

Examining the Academy’s connection to slavery and its path forward.

Sarah Pruitt ’95

42

“Exeter has always been this place that I’ve felt has magical powers to push you to discover more you didn’t know you were capable of doing.”

Byran

Huang ’25, p. 30

Byran Huang '25 built a custom open-source laptop dubbed “anyon_e” from scratch. p. 30

Covers: Photography by Yoon S. Byun

The View From Here

5

Around the Table

Principal’s letter ∙ Heard in Assembly Hall ∙ History Instructor Bill Jordan on educating for civility ∙ Robert Lutes ’73 and the role of class correspondent ∙ Inside History Instructor Meg Foley’s classroom ∙ A conversation with statesman Thomas Ehrlich ’52 ∙ Exonians in review ∙ What Daniel Connelly ’25 learned from a member of the Wampanoag nation ∙ Exoniana

19

The Academy

Jay Tilton retires from basketball coaching ∙ Girls wrestling ∙ Secret societies ∙ Dr. Emery N. Brown ’74 receives National Medal of Science ∙ Science Instructor John Blackwell honored with presidential award ∙ Global Initiatives ∙ Lamont Gallery exhibition ∙ Behind the scenes of the winter musical ∙ Winter sports

49

Connections

Autism research pioneer Dr. James Adams ’80 ∙ Impact investor Laura Callanan ’83 ∙ Cinematographer Julia Liu ’02 ∙ Architect Nate McBride ’70 ∙ Events from around the world

61

Class News and Notes

102 Memorial Minute John Bascom Heath

104 Finis Origine Pendet

The Exeter Bulletin Volume CXXIX, Issue no. 3

Principal

William K. Rawson ’71; P’08

Director of Communications

Robin Giampa

Editor in Chief

Jennifer Wagner P’24

Class Notes Editor

Cathy Webber

Contributing Editor

Patrick Garrity

Staff Writers

Adam Loyd, Sarah Pruitt ’95

Production Coordinator

Ben Harriton

Designers

Frank Webster, Jacqueline Trimmer

Photography Editor

Christian Harrison

Communications

Advisory Committee

Daniel G. Brown ’82, Robert C. Burtman ’74, Dorinda Elliott ’76, Alison Freeland ’72, Keith Johnson ’52, Yvonne M. Lopez ’93

TRUSTEES

President Kristyn A. McLeod Van Ostern ’96

Vice President Suzi Kwon Cohen ’88

Bradford “Brad” Briner ’95, Samuel “Sam” Brown ’92, Elizabeth A. “Betsy” Fleming ’86, Scott S.W. Hahn ’90, Ira D. Helfand, M.D. ’67, Paulina L. Jerez ’91, Giles “Gil” Kemp ’68, Eric A. Logan ’92, Eugene “Gene” Lynch ’79, Cornelia “Cia” Buckley Marakovits ’83, William K. Rawson ’71, Christine M. Robson Weaver ’99, Genisha Saverimuthu ’02, Michael J. Schmidtberger ’78, Peter M. Scocimara ’82, Sanjay K. Shetty, M.D. ’92, Leroy Sims, M.D. ’97, Rhoda K. Tamakloe ’01, Belinda A. Tate ’90, Janney Wilson ’83

THE EXETER BULLETIN (ISSN No. 0195-0207) is published four times each year: fall, winter, spring and summer, by Phillips Exeter Academy, 20 Main Street, Exeter, NH 03833-2460 Tel: 603-772-4311

Periodicals postage paid at Exeter, NH, and at additional mailing offices. Printed in the USA by Cummings Printing.

The Exeter Bulletin is sent free of charge to alumni, parents, grandparents, friends and educational institutions by Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, NH. Communications may be emailed to the editor at bulletin@exeter.edu.

Copyright 2025 by the Trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. ISSN-0195-0207

Postmasters: Send address changes to: Phillips Exeter Academy, Records Office 20 Main Street, Exeter, NH 03833-2460

Winter sports highlights: Girls swimming secured its third New England Championship title. p. 29

Cinematographer Julia Liu ’02, p. 53

The Good Life

During a recent session of REL540: Happiness, Fana, Eudaemonia, Nirvana, students and Principal Bill Rawson ’71 — who announced his decision to retire in June 2026 — engaged in a lively conversation about the roles of happiness and purpose in our lives.

“We were discussing whether happiness or purpose should be our main goal,” Religion, Ethics and Philosophy Instructor Peter Dziedzic says. “That is, should we set happiness as our ultimate goal, or should we aim for a life of purpose, and happiness comes as a result of this quest?”

Through thoughtprovoking readings, reflective writing and activities, Dziedzic aims to equip students with the tools to cultivate a deeper, more resilient understanding of happiness.

“Rather than telling students what to think,” Dziedzic says, “we expose them to a range of different ways of thinking about questions like these so they can continue discovering their own senses of self, community and meaning at Exeter and beyond.” ●

The Community Exchange

Letters to the Editor

Thank you for publishing Lauren Josef’s meditation in The Exeter Bulletin (“Song of Thyself,” winter 2025). It brought back the following vivid memory: The summer before my daughter Emily began kindergarten, she was only 4 years old. Her birthday was in October, so she turned 5 a month after school began. Beginning in June, to prepare her for that first day of school in September, I began telling her, “Emily, you’re a big girl now.” As the first day of school drew near, she repeated the chant to me, “Daddy, I’m a big girl.” Her excitement was palpable in her demeanor and smile.

The morning of her first day arrived. I waited to leave for work until her bus pulled up. Emily was still upstairs putting on her beautiful summer dress with my wife. She came down, sat next to me and began to cry. I held her close and whispered, “What’s wrong?” She gazed into my eyes and cried out, “Daddy, it’s hard being a big girl!”

I hugged her tightly. We then walked hand in hand to the bus stop. When the bus arrived she gave me a kiss, smiled and said, “I love you, Daddy.” I began to cry, realizing that my little girl was growing up and would eventually leave me.

Twenty-five years later, Emily is now a director at Target in Minneapolis living with my future son-in-law.

Looking back, I can now say, “Emily, it’s hard being a big girl’s dad!”

Maynard Timm ’70

I am writing with reference to the Bulletin in which a 1957 prank was mentioned (“Clipped from The Exonian,” fall 2024). That lifting of a VW Beetle onto the stage of the large assembly hall was not an original stunt. In 1948 or 1949, a racing green MG roadster belonging to a French language instructor with the unlikely name of Eli Fish was hoisted onto that same stage prior to the morning chapel service that began five days a week at 8:05 a.m.

Charles Moizeau ’51

I just need to tell you that I am blown away by the quality of the winter issue of the Bulletin. Every aspect of the magazine is top notch — the articles, the photos, the layout. I really appreciate the pieces that highlight the life and work of alumni that have followed their own path to find meaning and purpose. Keep up the great work!

Tracy

Burrows ’80

QWhat is New Hampshire?

That was the correct response to a Jeopardy! clue during the Feb. 18 episode of the popular TV Show. When contestant Jaskaran Singh chose “Libraries for $1,200” an image of the iconic Class of 1945 library was revealed. The clue: A library at Phillips Exeter Academy in this state is considered a master work of modern American architecture. We agree. It is a master work!

Watch the Jeopardy! clip on Instagram @phillipsexeter

We want to hear from you! The Exeter Bulletin welcomes story ideas and letters related to articles published in recent issues. Please send your remarks for consideration to bulletin@exeter.edu or Phillips Exeter Academy, The Exeter Bulletin, 20 Main Street, Exeter, NH 03833.

Around the Table

Academy Building Take a tour of Instructor in History Meg Foley’s classroom. P. 12

Prayer flags hang over the doorway in Foley’s classroom offering a colorful nod to her home state of Minnesota.

A Tradition of Caring

It is our custom at Exeter to publish a Memorial Minute when an emeritus faculty member dies. These are read in their entirety in faculty meeting and published in condensed form in the Bulletin. You will find a Memorial Minute for Jack Heath, instructor emeritus in English, included in this issue.

These are deeply moving tributes. We often are surprised to learn about aspects of a former faculty member’s life that we did not know, and amused by the anecdotes that former colleagues tell. Perhaps more than anything, we are inspired by the stories alumni share about the way their lives were impacted by their former teachers.

Alumni describe how these faculty members demanded the best of their students, helped them grow in confidence, and in many cases helped them develop passions that they carried forward in college and beyond. I have contributed a few stories myself

“The adults in our community — in whatever capacity they serve — lead purposeful lives right here, as they care for our students.”

about the way Exeter teachers affected my life as a student. Fundamentally, the alumni stories included in Memorial Minutes show how Exeter faculty care for and about their students. We are moved by these stories, and we are inspired to do all we can to have similar impacts on the lives of our students today.

Teachers, of course, are not the only adults on our campus who influence our students in positive and profound ways. During my Senior year, my dormmates and I were told that Dunbar Hall would be closed midyear for renovation and that we would be distributed across several other dormitories. My group, headed for Peabody Hall, had just one question: “Who gets Mr. Johnson?” Mr. Johnson was our custodian, and it meant a lot to us when we learned that he would be working in Peabody with us.

For three years, Eddie Wilber handed me my gym clothes before every soccer, hockey and lacrosse practice, and he gave me my uniform on game days. Mr. Wilber knew my name and he knew my size. He made me feel good about myself, and good about being at Exeter. I think of him every time I see the plaque that bears his name by the equipment room in the gym.

Dr. Heyl stitched me up after I took a skate in the eye during my Lower year. To this day, I don’t understand how he managed to do that without leaving any visible evidence of a scar. It was a pretty serious injury, but he made me relax and feel as if everything was going to be OK. He did more than close the wound; he took all the worry out of the experience. He cared.

Alumni across all generations have similar stories to tell about adults who were important to them during their time at Exeter — teachers and other adults who touched their lives in important ways and who made them feel at home when far away from home.

Our school’s mission is to “unite goodness and knowledge and inspire youth from every quarter to lead purposeful lives.” The adults in our community — in whatever capacity they serve — lead purposeful lives right here, as they care for our students and prepare them to lead their own purposeful lives. New stories are created every year. It all starts with caring. — Bill Rawson ’71; P’08

Heard in Assembly Hall

Sound

bites from this winter’s speaker series

“I’m sure being at a school like this, you live with a lot of pretty intense parental expectations … . There is a way, if you’re smart and you’re disciplined about your time, to take your own dreams as seriously as you take your parents’ expectations. If you have something that’s burning inside of you, don’t let go of it.”

Gene Luen Yang Graphic novelist and author of Dragon Hoops, this year’s ninth-grade common read

“Wilderness is not just about the animals or the beauty or the adventure. It’s about what it teaches us, what it makes us realize. It offers us a way to reconnect with something real. There’s no cellphone service, no stores, little comfort or conveniences — it strips things down to the basics. When I’m out there, I remember who I am without all the distractions. With only myself to rely on, I rediscover my strength through my ability to endure.”

Tia Shoemaker Registered Alaska hunting guide, writer and conservation advocate

“Creativity is enhanced in teams, particularly teams with diverse ways of thinking. The more diversity and thinking you have in a team, the more ideas you generate and the more creative that team will be. You have to be impervious to the fear of being wrong. Those scientists that said, ‘You can’t do this; this is impossible’ — you have to keep that at bay.”

Michael Strano Professor in chemical engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

“We all have aspirations we’re chasing — whether it’s a dream, a goal, a career, or a role on a team — and in pursuit of those goals we’re all going to face challenges [and] obstacles. It’s inevitable. Unfortunately, those challenges can be a deterrence for pursuing our aspirations. It can stop us in our tracks, causing a fear of failure and/ or doubt. But we also have the choice to endure and commit the effort to chase that dream.”

Scott “Kidd” Poteet Retired lieutenant colonel and mission pilot in the United States Air Force; commercial astronaut and triathlete

To watch videos of some of these assemblies, go to exeter.edu/live

Democracy Through Dialogue

Instructor in History Bill Jordan reflects on educating for civility

Exeter doesn’t have a required civics course, but for the past 20 years or so, I’ve been teaching one that comes close: HIS550:American Politics and Public Policy . So I’ve given some thought to what an American civics course should do.

The nuts and bolts of government and the U.S. Constitution are obviously essential to learn, and students should discuss contemporary policy issues. Some teachers think it’s more important to instill a passion for “social justice,” and to foster a sense of political efficacy and encourage civic engagement.

I’ve come to the conclusion that to prepare students for democratic citizenship at a time when Americans are splitting into antagonistic political tribes and mutually incomprehensible information bubbles, and credible commentators talk seriously about a coming civil war, it’s even more important to cultivate certain dispositions toward fellow citizens and the truth.

Over the years I’ve been influenced by others who have been asking the same question: teachers I met at the Exeter Humanities Institute, Harvard Professor Danielle Allen and her writings on citizenship, assembly speakers, a presenter at a National Association of Independent Schools conference and a number of “civic dialogue” organizations.

I read about one of these, Braver Angels, in a 2019 Atlantic article, “Can Marriage Counseling Save America.” Its mission statement, “The Braver Angels Way,” could hang comfortably above our Harkness tables. It reads:

• We state our views freely and fully, without fear.

• We treat people who disagree with us with honesty, dignity and respect.

• We welcome opportunities to engage those with whom we disagree.

• We believe all of us have blind spots and none of us are not worth talking to.

• We seek to disagree accurately, avoiding exaggeration and stereotypes.

• We look for common ground where it exists and, if possible, find ways to work together.

• We believe that, in disagreements, both sides share and learn.

• In Braver Angels, neither side is teaching the other or giving feedback on how to think or say things differently.

No one may be teaching, but everyone is learning. One of the priorities I adopted from that NAIS presenter for teaching citizenship is to cultivate the skill and inclination to practice “cognitive empathy,” understanding why other people think the way they do. That, combined with epistemic humility — appreciating our own intellectual limitations — leads to political curiosity, and the aha! moments for which Braver Angels leader (and Exeter assembly speaker) Mónica Guzmán named her 2022 book, I Never Thought of It That Way.

After I met Guzmán at a principal’s dinner in the fall of 2023, I decided to finally join Braver Angels and attend its June 2024 convention in Kenosha, Wisconsin. When I registered for the convention on the lovely lakeside campus of Carthage College, I was handed a name tag with a blue lanyard. Like all the civic dialogue groups, the 15,000 paying members of Braver Angels skew left — or blue in the Braver Angels argot. But unique to the Braver Angels, every convention, debate and workshop must be equally divided between blues and reds (righties), with a few (somehow unaligned or centrist) yellows mixed in.

Over the next three days I encountered the three Braver Angels approaches to conflict: dialogue, debate and communion. Most of my experience at the conference involved dialogue and communion.

This was the friendliest group of people. Guzmán’s political curiosity infused every interaction: We chatted across the lanyard line while waiting for a session to begin, while walking the paths between sessions and during meals in the dining hall. These encounters confirmed the argument of another depolarization outfit, that Americans on opposite sides of our great divide have “More in Common” than our differences. I even made some friends — yellow lanyards who write for conservative publications — that I’ve kept in touch with.

If all Americans could attend one of these conventions, we might not solve all of our problems, but we would stop hating each other.

I sat in on different kinds of Braver Angels debates, one in which “the point isn’t to win; it’s to understand the other side a little better”; and another in which the goal was to come up with a list of policy ideas both sides could agree on. The most momentous debate took place at a plenary session among all the convention goers to choose an issue to focus on in the coming year. Immigration won after a vigorous — but civil — discourse.

The only disappointing debate was the one between Presidents Joe Biden and Donald Trump, which happened on the first night of the convention. We gathered to watch in the assembly hall. It led all

750 attendees to agree on one emotion: dissatisfaction with the options our two major political parties were offering us.

Of course, there’s a selection bias that made this group unrepresentative of the American electorate. Not likely to attend: Twitter trolls and others who see the solution to America’s problems in defeating political “enemies,” not in finding common ground or reaching compromise with “rivals.” But they make up only 33 percent of us, according to a More in Common poll.

I agree with David Blankenhorn, Braver Angels’ founder and president, who said in his plenary address, “Democracy is government by talk, and when conversation ends, the only thing left to advance your argument is force.”

Maybe if every high school in the country would teach cognitive empathy, along with epistemic humility and other elements of “The Braver Angels Way,” we could produce a generation of citizens that might reverse the tide of polarization and save democracy.

Bill Jordan has been an instructor in history at Exeter since 1997. He has been adviser to The Exonian student newspaper, dorm head of Amen Hall and chair of the History Department. He has directed Exeter’s Washington Intern Program since 2020.

What is Braver Angels?

A nonprofit dedicated to political depolarization. Its mission is “bringing Americans together to bridge the partisan divide and strengthen our democratic republic.”

Recorder of the Ages

Robert Lutes ’73 remembers 20-plus years of writing the Class

News and Notes column

Possibly the best decision I have ever made, in my long affiliation with Exeter, was when I volunteered, during my 30th reunion, to become a class correspondent. That is, to gather the news and notes from my fellow 1973 classmates quarterly and write a column for The Exeter Bulletin. I had attended every one of my reunions since graduation, and I had always had an immensely good time, visiting with old friends, making new ones and spending time on the campus of the school I love dearly. So the opportunity to communicate with classmates more often seemed like a great idea. And I have never regretted it.

My co-correspondent in those early years was Sally Spoerl, who has been one of my best friends since

seventh grade, and more recently I have shared the duties with Robert Barnett, another close friend who was a fellow Abbot Hall hooligan.

Gathering news from classmates is not without its challenges. In my first few years as a correspondent, a number of classmates didn’t have email. Instead, the Academy provided stamped postcards to send to them. Somewhat tenuously attached to each postcard was a blank card, also stamped and affixed with my address label. Rather frequently the two cards became separated in the mail and the postal service would dutifully send the blank card back to me. When I received the first of these blank cards, I thought a classmate was sending it back anonymously, silently telling me, “This is what I think of your request for news.”

But I always hear back from a few classmates, sometimes quite a few, and receiving those messages is always a bit of a dopamine hit. Nowadays all the correspondence is through email, and the Alumni Office makes it easy by sending a blast email to the class, containing whatever begging, cajoling or threatening message we wish to use in order to solicit contributions from our friends.

The most common reason that classmates give

Robert Lutes ’73 at home in Pueblo, Colorado, with his vast collection of The Exeter Bulletin magazines. The oldest edition dates to October 1972.

me for not sending in news is the feeling that they have not done anything worth speaking about, compared with what others have done. One time I sent out my request for news, saying that they need not have won an Olympic medal or a Nobel Prize for their lives to be newsworthy. Then one of our classmates, Paul Romer, won a Nobel Prize. Now I have to say that Paul never wrote to tell me about the award, but I felt it was newsworthy enough to be included in the class notes. And I am sure that some classmates felt even more intimidated and became even less likely to send in their family news. But I am equally certain that Paul wanted to hear about his friends’ grandchildren and vacations just as much as they wanted to read about his Nobel Prize.

As we get older, I receive lots of news about children, grandchildren and travels. Hearing about these moments of pride and excitement provides me with a feeling of intimacy with classmates that I could not otherwise experience. Sometimes classmates reminisce about their time at Exeter, and those memories will take me back as well. Suddenly I’m that awkward teenager again, worrying about, in increasing order of importance, that English paper I still haven’t written, or the upcoming track meet, or why that one girl doesn’t like me back. (After all, I stood there, leaning against the wall of the Davis Student Center all evening, staring at her, so what more could she want from me?)

Only once did I find my work being censored. My classmate Susan had written about her sporty new car, which was faster than every other car around. Anticipating further midlife needs for excitement and inspired by a popular television show called “Pimp My Ride,” I speculated that soon she would be driving a “pimped-up truck,” before ending up riding a Harley as she approached old age. The Academy couldn’t abide such a suggestive term, and “pimped-up truck” became simply “pickup truck,” and the message I was trying to convey became somewhat deflated.

Exonians don’t just have amazing careers and wonderful families and do things that fascinate us. Sometimes they die. I wasn’t quite prepared for the emotional strain of reporting on a classmate’s death the first time. I was glad that I was not a class correspondent when my best friend died at a far-too-young age in the late 1980s. That was devastating, and I don’t know how I could have written about it.

But I have learned that death, however sad, is also an opportunity to celebrate life. Honoring people with little stories about their lives, from my memories or those of classmates who were closer to them, or from things I learned online, allows me to get past the sadness of their passing and appreciate all that they did, and all the lives that they touched, while they were still with us.

An unexpected benefit of being a class correspondent is being invited to the annual Alumni Council Weekend, which is now known as Exeter Leadership Weekend. Every fall, representatives of all the classes gather at Exeter for meetings, lectures and school activities, with the goals of updating us on new developments at the school and gleaning ideas for further improvements.

“One time I sent out my request for news, saying that they need not have won...a Nobel Prize for their lives to be newsworthy. Then one of our classmates, Paul Romer, won a Nobel Prize.”

Among the initiatives we have learned about over the years are improvements in diversity at Exeter, the concept of non sibi, increased importance of the arts at the school (so now the focus is on three A’s: academics, athletics and arts), and need-blind admissions (so financial concerns are never an obstacle to attending the Academy).

For me the highlight of the weekend is the Friday evening dinner with the senior class. These students are really what Exeter is all about, and they never fail to impress me with their enthusiasm for and love of the school. They always seem to be far more intelligent, mature and well-rounded than we ever were as students, and we alumni always come away from that dinner thinking that we would never be able to get into Exeter today. The students always want to know about our days at Exeter, and especially about the early days of coeducation.

Sometimes you really connect with a student. One year I was walking to the dinner in the gymnasium with two classmates, Sally and Kris. Walking toward us was a student with a big smile. We decided we wanted to sit with this happy young woman. She told us how much she loved Exeter and couldn’t imagine what it would be like to no longer be a student there.

I shared the story of my last few hours as a student. Graduation was over and my family had to leave right away. I stayed behind to say goodbye to friends. One by one they drove off with their parents, and after a few hours everyone was gone. The campus was eerily deserted. I took my stuff out of my room and piled it in front of Abbot Hall. And then it hit me. My time as an Exeter student was really over, and a wave of sadness, the profundity of which shocked me, overcame me. “Oh my,” the student said, “that’s exactly how I’m going to feel. I don’t know how I’m going to bear it!”

Being a class representative helps you to bear it. Hearing from classmates is sort of like being back at school with them. And rewriting their stories for the Class Notes enables me to appreciate their adventures. Visiting campus, I feel like a student again, but without the stress of exams or papers or broken hearts. Just the joy of seeing old friends, making new ones, visiting with students or attending an athletic event or a dance recital is a reminder of what an unbelievably special place Phillips Exeter Academy really is.

Robert Lutes ’73 has been a class correspondent since 2003. He holds a degree in art history from McGill, a master’s degree in public health from Harvard and a medical degree from the Medical University of South Carolina. He has worked in emergency medicine for the past 34 years.

Interested in becoming a class correspondent? Contact Cathy Webber at cmwebber@exeter.edu

Presence of the Past

Inside the classroom of Meg Foley, the Michael Ridder, class of 1958, distinguished professor in history

You would forgive Meg Foley if at some point during the next academic year she started her workday by walking to the northeast corner of the Academy Building — and into somebody else’s classroom. That kind of muscle memory develops from teaching in the same space for nearly two

and a half decades.

But in July, Foley will transition to a new role, dean of faculty, and away from her corner room with the views into two quads. “I’ve had the chance to switch rooms over time, but I’ve always stuck with this room because I love the classic features,” she says. “And I love the vantage point. As people are leaving the building,

especially after assembly, students or colleagues from other departments will pop in to chat. I’ll really miss that.”

Foley says she’ll also miss those moments of connection around the Harkness table, where — for 50 minutes each class — everything outside Room 030 fades away and meaningful discussion takes over. ●

↑

“That time of really deep attention that we all give to each other when we sit with the text and we talk about history, I feel like, ‘What could be more important?’ I’m very lucky to meet these kids at this moment in their life and this moment in time. They’re still coming to terms with what they value, and sometimes they might approach something ideologically and then a few weeks later it seems like they’ve changed their mind. It’s a time when they’re trying out a lot of different ideas, and I love to give them a chance to do that.”

→

“There are various tributes to my home state of Minnesota sprinkled around the room. I’ve got the ‘Purple Rain’ cover of The New Yorker from when Prince died, the Minnesota Twins Homer Hanky and Boundary Waters prayer flags.”

→

“These maps are so old; this one is from 1954. The country borders have changed, of course, but when you’re teaching history, that can be useful! They’re so fragile, I’m always worried that they’re going to rip.”

→

“I like to have a few little toys out that kids will sometimes play with or just hold while they’re talking or at the table. I started the course Why Are Poor Nations Poor? and a student who lived in Bangladesh came back from winter break and brought me this tiny rickshaw. She told me all about the marketplace where she bought it and the artisan who had made and sold it to her. So much of her story aligned with themes in the course.”

→

“These are document readers for two courses, one from 1998 and one from this year. With our teaching, there’s kind of a lineage to it. You start by working with somebody off of their syllabus and then you make changes and adjustments and slowly it becomes your own. Or maybe you make a radical break and it becomes your own suddenly. Then someone else starts teaching the course and you share your syllabus with them and they make their additions and you add some of their additions to your own. When you look back at these readers, you can see that lineage.”

THE TABLE / INSIDE THE WRITING LIFE

Public Service

A conversation with statesman, educator and attorney Thomas Ehrlich ’52

Thomas Ehrlich ’52 has served in the administrations of six U.S. presidents — including as the first president of the Legal Services Corporation and the first director of the International Development Cooperation Agency, reporting directly to President Jimmy Carter. He was also dean of Stanford Law School, provost of the University of Pennsylvania and president of Indiana University.

He has authored, co-authored or edited 15 nonfiction books, written two novels and is finishing a third, Jewels

We spoke with Ehrlich, 91, about his memoir, Learn, Lead, Serve: A Civic Life, released in December.

You talk about mentorship throughout the book. Is there one mentor who had the largest impact on you?

My father. We were as close as father and son could

be — we skied together, played together, read novels together. I can still remember reading The Once and Future King with him. He was always there, always supporting me and a model of what a father, a husband and a caring civic person should be. Other mentors have had a shaping influence on my life including Judge Learned Hand, for whom I was a law clerk, and Under Secretary of State George W. Ball, for whom I was a special assistant during the escalation of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

You tell a story about your grandmother giving you a biography of Louis Brandeis, an attorney and associate justice of the Supreme Court. Did that shape your decision to use your abilities for the public good?

Yes, I still have that blue-bound copy of that biography. Brandeis was a great public servant in the best sense. And service was an important part of Exeter for me as well. In my memoir, I call Exeter my ‘best education’, and that’s not hyperbole. Harvard and Harvard Law School were wonderful, but Exeter and the dedication of the teachers 24/7 to their students, of whom I was privileged to be one, was just amazing and transformative for me. Non sibi was at the core, and that really shaped me — it shaped my sense of who I am, how I want to relate to the world around me. I think of the times when I have had the good fortune to be involved in public service, and I really owe much of that to Exeter. This is what Exeter expected of us as students — to think not just about ourselves, alone — and that’s just the way you behaved. When you learn that and behave that way, or try to at least, as an adolescent, it’s built into your character as you grow up and grow older.

It seems like Exeter shaped you emotionally, as well as intellectually.

It did very much, yes. Intellectually, it certainly did in history and in English. We wrote a lot and I’m still writing now. I’m 91 years old, and here I am, writing away, working on my third novel. Exeter is where I learned to read and write, to write and enjoy.

For your Harvard thesis, you researched a survey of family farmers that was done by the Department of Agriculture. You say it was an early awakening for you to the importance of public policy shaped by public opinion. How does it frame the way you look at what’s happening in our country today?

I’m deeply disturbed by what’s happening now. The Trump administration’s assault on our democracy is terrifying. I taught for many years a course called “Democracy in Crisis” at Stanford, so I’m familiar with past crises. And of course, we did have a civil war. This is not a civil war, but I am devastated by seeing what’s happening in terms of an elected president seeking to destroy much of the social fabric of our country, as well as its leadership in the world. Since I oversaw the Agency for International Development, its destruction is a particular blow to me. Millions of people are dying because of that action.

“It’s important not just to serve in a community kitchen, but to ask: ‘What public policy changes are needed so that community kitchens are no longer necessary?’”

Do you see a future way of managing our way out of this?

I have hope. I quote one of my professors, Sam Huntington at Harvard, who wrote a terrific book American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony. He ends by saying, “Critics say that America is a lie because its reality falls so far short of its ideal. They are wrong. America is not a lie; it is a disappointment. But it can be a disappointment only because it is also a hope.” I have hope. I believe we will have a pendulum that swings back toward the middle, that those in Congress will say, “We’ve got to stand up and stop what’s happening.” But the carnage that’s happening — America’s place in the world will never be the same.

In your many roles in six administrations, was there one in particular that has stayed with you? Well, they all stay with me. But the one that shaped me most was the Legal Services Corporation, because when I became dean at Stanford Law School, I had no real idea that 40-plus million poor people had no access to justice. It concerned me, which is why I thought, “If I can have a chance to do something about that, I want to do it.” I spent three-plus years listening to poor people all over the country, hearing their stories of how a crisis would happen if they didn’t get a Social Security check or got evicted, and how important it was to have a lawyer, and what a difference that person could make by listening and devoting their lives to helping poor people. That also shaped my approach to others less fortunate and my character.

You’ve become particularly focused on instilling young people with awareness around community service, public service and civic learning. Do you think that that’s our most hopeful way forward?

I do. I think it’s essential. That has been my passion since the mid-’80s when I was at the University of Pennsylvania, but it’s certainly increased in that the only significant organizations outside of the universities that I’ve helped to run are ones dedicated to preparing college students to be actively, responsibly engaged in public policy and politics. If we don’t do a better job of that, we’re going to suffer more. It’s important not just to serve in a community kitchen, but to ask: “What public policy changes are needed so that community kitchens are no longer necessary?”

— Daneet Steffens ’82 is a books-focused journalist. She has contributed to The Exeter Bulletin since 2013.

Learn, Lead, Serve: A Civic Life, by Thomas Ehrlich ’52.

AROUND THE TABLE / WORKS

Exonians in Review

The latest publications, recordings and films by Exeter alumni and faculty

The Etruscans and the Jews: New Orleans Echoes, Sardinian Shadows, Roman Shame

Peter M. Wolf ’53 Xlibris, 2025

“Postmortem Neuropathology in Early Huntington Disease,” article

John Hedreen ’56 with Sabina Berretta and Charles L White III Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, Volume 83, March 2024

The Helper’s Apprentice: The Jackson Skye Mysteries

Carl Pickhardt ’57 WP Lighthouse, 2024

Breath Lines: How Poems Work and Why They Matter

Jan Schreiber ’59 LSU Press, 2025

Winter Light: On Late Life’s Radiance

Douglas J. Penick ’62 Punctum Books, 2025

The Wind in the Trees

Gordie Chase ’66

Self-published, 2025

Diversity Dysfunction: The DEI Threat to National Security Intelligence

John A. Gentry ’68 Academica Press, 2024

Long Short Fiction Truth

Tony Seton ’68

Self-published, 2024

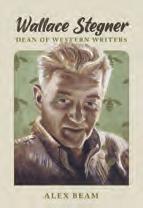

Wallace Stegner: Dean of Western Writers

Alex Beam ’71

Signature Books, 2025

Racquets & Rivalries: Tales and Profiles from 100 Years of New York City Squash

Rob Dinerman ’72

Self-published, 2024

“What Should Health Professions Students Learn About Data Bias?,” article

Douglas Shenson ’73 with Beverley J. Sheares and Chelesa Fearce

AMA Journal of Ethics, Volume 27, January 2025

The Silenced

Mer Boel ’74 and Lucy Pantaleoni Bernier ’74

Self-published, 2024

Grandpa Used to Drive Big Trucks

Martha Nance ’76 with Steve Witebsky Wise Ink Creative Publishing, 2024

“A Closer Look at the Russell Paradox,” article

Flash (Kenneth J.)

Sheridan ’78

Logique et Analyse, Volume 262, 2023

“Parallel Line,” art exhibition

Ralston Fox Smith ’83, painter

Upstairs Artspace, Tryon, North Carolina, March 16 to April 25, 2025

I Commissioned Some Wooden Luggage: and other poems

Nicholas Benson ’84 Agincourt Press, 2024

Murder in Rockport Massachusetts: Terror in a Small Town

Rob Fitzgibbon ’86 with Wayne Soini

The History Press, 2025

Betting on Good: A Novel Wendy Francis (Holt) ’86 Lake Union Publishing, 2025

Penitence: A Novel Kristin Koval ’88 Celadon Books, 2025

La Motte-Feuilly: Un château de familles en Berry; Son histoire, son architecture & ses secrets Christophe Charlier ’90 with Marie-Pierre Terrien Simarre, 2024

Against the Grain: Mass Timber in the Home

William Richards ’00 Schiffer, 2024

“North American Red Fox Rabies Immunity Gene Drive for Safer (sub)urban Rewilding,” paper

Vixey Foxwish Douglas ’11 Rio Journal, 2024

Space to Grow: Unlocking the Final Economic Frontier

Brendan Rosseau ’15 with Matthew Weinzierl Harvard Business Review Press, 2025

FACULTY

“Jus Post Bellum and the Moral Imperatives of Reconstruction,” chapter in Teaching Emancipation and Reconstruction, 1861-1876

Kent A. McConnell, Instructor in History

Peter Lang, 2024

Submit your work

Alumni are encouraged to advise the Bulletin editor (bulletin@exeter.edu) of their own publications, recordings, films, etc., in any field, and those of their classmates, for inclusion in future Exonians in Review columns. Please send a review copy of your published work to the editor to be considered for an extended profile in future issues. Works can be sent to: Phillips Exeter Academy, The Exeter Bulletin, 20 Main Street, Exeter, NH 03833.

Student Club Meeting

What Daniel Connelly ’25 learned from a member of the Wampanoag nation

Walking into the Office of Multicultural Affairs on the ground floor of Jeremiah Smith Hall, my senses were immediately delighted by the smell of sweetgrass and delicious Three Sisters Soup and cornbread provided by the dining hall. Images of Maciah Stasis tattooing a woman’s face and of gorgeous works of white and purple quahog shell jewelry were projected on a TV screen.

The Indigenous Reconciliation Club (IRC) and OMA had invited Stasis, a Herring Pond Wampanoag wampum worker, tattooist, regalia maker, storyteller and singer-dancer to campus to give two workshops and celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day. She was seated at the head of the Harkness table and engaged in deep discussion. As co-head of the IRC, it filled me with joy to see faculty and students packed around the table to learn from Stasis.

She began by telling us a bit about herself. We learned that she is a citizen of the Herring Pond Wampanoag tribe, and was born in the land of her ancestors, Plymouth, Massachusetts, where she graduated from Plymouth North High School. Since the age of 15, she has been educating others about her people, delivering keynote addresses at a number of museums and other Indigenous events throughout the U.S. and Canada. Interestingly, she had just returned from a traditional tattooing conference in Canada, where she learned from Inuit tattooists, whose tattooing customs have remained more intact than those of Northeastern Indigenous nations in the U.S.

She shared many details about her work as a wampum jeweler. The quahog clam used to make wampum is endemic to the waters around the Wamapanoag’s land and is believed to be a gift to the Wampanoag as it existed nowhere else. Wampum was greatly valued by Northeastern tribes, and the Wampanoag traded it with surrounding tribes such as the Haudenosaunee, who used it to create treaty belts, among other items. In addition to a form of currency, wampum was and is made into jewelry. Stasis said the work is laborious but worth it. Her pieces include rings, necklaces, bracelets and carvings of wildlife. But, she warned, the dust shed by quahog shells is toxic and has been known to kill ill-prepared artisans.

Stasis then spoke on quillwork, a rare and complicated form of art that uses the quills of porcupines.

Quillwork predates beadwork and is used to ornament regalia in much the same way. It is painstaking: Make one mistake and you have to start over, even after multiple hours, or days, of work.

Last, she spoke about her story and process as an Indigenous poke tattooist. She said that tattooing is practiced around the world, and the most common and ancient form is stick-and-poke. This refers to using a sharp needle, or thorn, to insert pigment such as soot into the skin. The method was used across the continent, including in the Wampanoag Nation. Although the custom varied from nation to nation, tattoos generally marked events like childbirth, ages, deaths and accomplishments. But this practice has been suppressed and vilified throughout the history of our country; as a result, few Indigenous cultures continue to practice traditional tattooing.

I learned that Stasis, who has tattooed herself and others for a variety of reasons, is truly a trailblazer in revitalizing this important cultural custom. She says the process is extremely intimate and exhausting, and emphasizes the importance of the environment, the energy and the tattooist during the procedure.

By the end, all of us around the table were brimming with questions, which Stasis answered. She gave each of the attendees a small satchel that contained part of a quahog shell, cedar, deer sinew and sweetgrass, each of which provides protections and properties, she said. I left with a wealth of knowledge and a deep sense of gratitude. This was a truly transformative and mind-expanding event unlike any other I’ve attended in my time at Exeter, and I am extremely grateful for the knowledge Stasis shared, and the space she created in OMA that day.

Daniel Connelly ’25 is a proctor in the Office of Multicultural Affairs and co-head of the Academy’s Indigenous Reconciliation Club.

Daniel Connelly ’25 holds a shelf mushroom.

The Indigenous Reconciliation Club’s spring book club selection is Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants, by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

ALL ABOOOOOOARD!

Did you ever take the train to or from school? Do you have a fond (or funny) memory of a day trip to Boston?

Left my cellphone on the train on the way to school. Thankfully the lovely folks found it and I was able to get it back! Haha, my mom was gunna kill me.

Catherine Shipps ’13

Probably apocryphal, but my dad told a story about [famed blues singer] Lead Belly coming to perform at Exeter, and when the teacher who invited him walked Lead Belly to the station, he hopped a freight train out of town.

Patrick Cahn ’88

Lead Belly did perform at Exeter in the fall or winter of 1948-49. I heard him. Of interest is the fact that the program in the arts series which preceded his by a few weeks was an organ recital by the world-famous Marcel Dupré on the Aeolian-Skinner organ in Phillips Church.

Hoyt Winslett ’52

In the fall of 1963, I took the train so I could go to a doctor’s appointment in Boston. I was 13 at the time. I think the train went to

Do

You Remember?

North Station. I took a cab to Children’s Hospital from there. I don’t remember telling anyone about my trip.

Nicholas Volkman ’67

My dad took the train from Florida to Exeter as a student in the late ’40s.

Alexis Mead Walker

— All responses originally posted on social media

From the Editor

Exonians have been riding the rails ever since passenger train service arrived in Exeter in the 1880s. For the first half of the 20th century, a student could board the State of Maine Express at New York’s Penn Station at 9 p.m. and arrive at the Exeter train station at 4:52 the next morning — well before morning “chapel.”

These days, Amtrak’s Downeaster stops in town 10 times daily on its runs between Brunswick, Maine, and Boston’s North Station.

This photo of the Exeter train station was taken by David Nimick ’42 on May 16, 1942. As for why the train station was so crowded the day Nimick snapped this photo, we believe current upper Shay Kashif ’26 nailed it when he guessed “maybe something to do with the gasoline rationing put into place the previous day?”

On May 15, 1942, the federal government ordered gas to be rationed across 17 states in the eastern U.S. in support of American armed forces fighting World War II. This most likely explains the crowd.●

The Hill Bridge has spanned the Exeter River for a century. It’s a beloved landmark — and has also seen its share of mischief through the years. Have a memory to share? Don’t worry, alumni. We’re pretty sure the statute of limitations has expired. Email your reminiscences to bulletin@exeter.edu/. Responses will be published in the next issue of the Bulletin

The Exeter train station on May 16, 1942. Photograph by David Nimick ’42.

The Academy

The site-specific installation features abstract acrylic

Exhibition Visiting artist transforms Lamont Gallery into a conservatory. P. 25

flowers.

THE ACADEMY / RETIREMENT

The Final Quarter

Jay Tilton retires from coaching Exeter boys basketball after 23 years

The 2012-13 Exeter boys basketball team was riding high when it returned from the holiday break. The team was 7-0 as it prepared for a game at Kimball Union to tip off the second half of the season.

“Sure enough, we got our brains beat in and we were brought back down to earth,” Harry Rafferty ’13 recalls. “The loss reminded us that we were a special group, but we still had to get off the bus and compete. We had to hold true to the principles our coach had laid out for us.”

In case anyone had forgotten one of those principles, coach Jay Tilton had T-shirts printed to remind them: HUMBLE PIE. EAT IT.

“It was not a fancy font or anything like that,” Rafferty says, laughing. “True to Jay form, it was black font on a white shirt; as basic as it gets.”

Exeter didn’t lose another game the rest of the season, going 25-1 and capturing the first NEPSAC Class A title in program history. The Big Red went on to win four more

titles during Tilton’s tenure as coach.

But his 210-96 career record and seven championship game appearances are just part of the legacy he leaves behind as he retires from coaching to become regional director of major gifts in the school’s Office of Institutional Advancement.

“Coach T could always see the bigger picture,” Emmett Shell ’18 says. “He left a lot of us with life lessons that have been invaluable. He got me to see a way of approaching not just basketball, but life with a little more toughness, a little more consistency, and a little more energy, which I think can make all the difference.”

Tilton began leading the program in 2009 after nine seasons as an assistant coach under Malcolm Wesselink. Tilton’s father, Mark, coached for 21 years at New Hampton School, where the basketball court is named in his honor. “I grew up watching the modeling of coaches and student-athletes, so that has always been in my blood,” says Tilton, 56, who was born in Berlin, New Hampshire, and spent four years as an assistant at Dartmouth College.

“Life lessons were taught through athletics, and my greatest mentors in my life were coaches, but they were also educators.”

When Tilton was considering the move to Exeter, his peers told him he couldn’t win there because of the Academy’s academic standards. He took that as a challenge — one he passed on to his team.

“Coach T was really good at making sure everyone was producing and contributing at their highest capacity,” says Shell, who was a co-captain his senior year. “He pushed me in ways that I never thought I could be pushed.”

Tilton describes himself as an emotional coach, but Rafferty says that emotion never turned negative. “He has this Ted Lasso-like sensibility or optimism that makes guys really want to play for him,” Rafferty says. “Aside from him being a great coach, he’s genuine and he has every one of his players’ backs, long after they played for him.”

Tilton began pondering retirement a couple of years ago. He felt he had accomplished all he could, and he wanted to spend more time with his wife, Darcy, and his son, Cameron. They had sacrificed so much, he says, because of the demands of coaching. When Rafferty joined his staff as an assistant coach this season, a succession plan was in place.

“I knew I was on the back nine,” Tilton says. “I just wasn’t sure if I was on 16, 17 or 18. When Harry told me was getting out of the college coaching world and coming back to the area, I was like: ‘Wow. What are the odds this is happening right now?’

“Harry Rafferty was the best teammate I’ve ever coached because he really understood people, he is an exceptional motivator and, of course, he really knows how to coach. The program will be in good hands.”

Before the team boarded the bus to head to the 2025 NEPSAC title game in March, Tilton spent a quiet and poignant moment in the gym. It took him back to the 2012-13 season when, just before his team claimed its first title and altered the trajectory of the program, he sat in the gym by himself and thought, “We’ve arrived.”

“This time around, I knew it was going to be my last bus ride with the team,” he says. “It was an emotional moment because it was a reflection of everybody that’s been through that journey with me. I remember the big wins and the trophies, but the highs and lows that you share with a group of young men who are committed to working together — whether you achieved or you fell just short — those are the things that I will remember the most. I feel so incredibly grateful to have had those moments with these young men, these Exonians.” —Craig Morgan

Big Red basketball won five NEPSAC Class A titles under the leadership of coach Jay Tilton.

Girls Wrestling

Female athletes take the mat in growing numbers

This season Big Red wrestling’s roster featured 10 girls, the most in the history of the program. A traditionally male-dominated sport, wrestling at Exeter is rapidly growing into a competitive arena for female athletes — a trend that’s happening around the country. The National Federation of State High School Associations reports that girls wrestling has experienced significant growth in participation, increasing 102% since 2021.

“There are multiple teams with double-digit numbers of girls on their roster this year,” says head wrestling coach Justin Muchnick. “There are girls divisions at both the league and New England tournaments, as well as several girls-only invitationals throughout the season.”

The rise of girls wrestling can be attributed in part to top-down efforts. The inclusion of women’s wrestling in the Olympics in 2004, the expansion of women’s college programs and the NCAA’s decision to recognize women’s wrestling as an official championship sport in 2025–26 have provided clear pathways for female athletes to compete at higher levels.

“In the world of New England prep

schools, a lot of this has been driven from the bottom up, by individual coaches and programs committing to girls wrestling,”

Muchnick says. “You have to give a ton of credit to Andover for being the prime mover here: Kassie Bateman and Rich Gorham have spent a decade-plus making this vision a reality. But at this point there are quite a few other programs — Choate, St. Paul’s, Hyde, Northfield Mount Hermon and now us — that have made girls wrestling a priority.”

Exeter ranks in the top third of NEPSAC wrestling programs in terms of girls participation. The focus moving forward is on retention, recruitment and building a team capable of filling all 12 weight classes.

“I really want to use our current momentum to add as many girls as we can to our program!” Muchnick says. “Beyond competition, the growth of girls wrestling is reshaping the culture of the sport itself. The camaraderie among female wrestlers, even between competitors from different schools, is setting a new standard. As girls wrestling continues to flourish, it is clear that the sport is becoming stronger, more inclusive and more dynamic than ever before.” —Brian Muldoon

Evolution of a Super Fan

Tripp Whitbeck ’99 on his journey from Big Red booster to the Mayor of Natstown

I’ve always been someone who likes to support my place. Pride of place is something that’s important to me, and it’s something that was catalyzed at Exeter.

1998

Here I am at Exeter/Andover my senior year. We won! Prior to the weekend, they were passing out tubes of red paint. I certainly took full advantage of that. I didn’t really go to a lot of games as a kid so the ability to be a fan on the front lines — no matter how the team was doing — was something I quickly embraced.

CIRCA 2000

I became Lord Jeff, former mascot of Amherst College. The president of the college came up to me at the homecoming football game my freshman fall and said they hadn’t had a mascot in 10 years. He asked me, “Would you do it?” I said, “Of course!” That was my main extracurricular activity for the next four years.

2019

I grew up a Mets fan, but when I moved to the D.C. area, I got season tickets to the Washington Nationals. We were a horrible team and I was one of the only fans there on many nights. The beer vendors nicknamed me the Mayor of Natstown. When the beer vendors give you a nickname, you kind of go with it.

Tripp Whitbeck ’99 is the founder of I Bourbon, an independently labeled straight bourbon whiskey brand bottled in Bardsville, Kentucky.

Exeter ranks in the top third of NEPSAC wrestling programs in terms of girls participation.

The Secret Societies

Fraternities once stirred intrigue and controversy on campus

Skulls, crossed bones, swords and smoke — these are just some of the iconic symbols that represented Exeter’s early secret societies, or fraternities. Their origins trace back to 1818, when the Golden Branch Literary Society emerged as a secret organization. The first fraternity, Pi Kappa Delta, was started about 1870, but not until the 1890s did a growing number of these groups begin to stir intrigue, mystery and controversy.

As a 1935 article in The Exonian described, the secret societies distressed some faculty and the administration: “They openly opposed faculty authority. The initiations were held late at night, and in some cases, all night, and the candidates were injured both mentally and physically, so that their class work began to drop.”

The initiation ceremonies, as chronicled in the article, were both eerie and humiliating. One society, for instance, took initiates to an old burial vault lit only by candles. Other societies, it recounted, were notorious for their physical tests, including branding candidates with a cigar and requiring candidates to appear in “fantastic and almost no clothes at classes, sell peanuts to the faculty and townspeople, and make speeches from a soap box at what is now the town bandstand.”

The growing tensions between the societies and the administration culminated in 1891, when Principal Charles E. Fish explicitly banned their existence and forbade students from participating in them. Enforcing those rules proved none too easy and the effort to root out fraternities ultimately failed.

In 1896 Principal Harlan Page Amen took a different approach. He granted official sanction to the fraternities with increased faculty supervision. This was a turning point, marking the beginning of a more controlled and formalized era for the organizations. At the time, there were six fraternities, each of which rented rooms in various homes near the Academy.

In 1908, Exeter established the Interfraternity Council, which brought all the fraternities under a centralized governing body — a move intended to further bring order and oversight to the secret societies.

But by the mid-20th century, the face of Exeter had changed. In June 1942, the Committee on Fraternities recommended the abolition of all fraternities, citing two key reasons. First, the school’s updated environment — with all students living and eating in dormitories — created a new social dynamic that diminished the need for secret societies. Close friendships could be formed more naturally, without the artificial divisions created by fraternities, they argued. Extracurricular groups that were more inclusive and diverse in purpose had also begun to take on the social roles that fraternities had once held.

Second, the committee took issue with the undemocratic nature of fraternities. “They segregate school leaders, foster snobbishness, and divide rather than unite the school,” the committee wrote. “In a nation and a school that champion democracy, it is not appropriate to condone such undemocratic institutions.”

The recommendation to formally abolish fraternities was passed by a vote of the faculty, signaling the end of an era.●

The Academy archives hold many pieces of ephemera related to the secret societies, including meeting notes, letters, banquet menus and books featuring iconography (shown above), rituals and membership ranks.

National Medal of Science

Emery N. Brown ’74 lauded as innovative neuroscientist, statistician and anesthesiologist

Dr. Emery N. Brown ’74 received the National Medal of Science, the nation’s highest honor for achievement in science and engineering, for his work studying anesthesia’s effect on the brain. The award was presented at a White House ceremony in January.

Brown is a professor in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, a member of the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, a professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School and an anesthesiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“Brown is at the forefront of the Institute’s collaborations among neuroscience, medicine and patient care,” says Nergis Mavalvala, dean of MIT’s School of Science. “His research has shifted the paradigm for brain monitoring during

general anesthesia for surgery.”

Over the last 20 years, Brown has focused much of his signal-processing research to studying the neurophysiology of how anesthesia acts in the brain. His goal is to improve anesthesiology patient care and to use his understanding of how anesthesia works to gain a deeper understanding of brain function and to improve brain health.

“I’m extremely excited and quite honored to receive such an award because it is one of the pinnacles of recognition in the scientific field in the United States,” says Brown, who shares this year’s honor with 23 colleagues around the country. ●

Presidential Award for Excellence

Science Instructor John Blackwell recognized as outstanding educator

John Blackwell, a longtime instructor in science, has been honored by the Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching. The program recognizes outstanding educators from across the country who teach science, technology, engineering or mathematics in elementary or secondary school. Thousands of top teachers have been recognized since the program was established by Congress in 1983, including Emeritus Instructor Richard Brown in 1989.

Each awardee received $10,000 from the National Science Foundation and a certificate signed by President Joe Biden.

Blackwell has taught astronomy and physics at Exeter since 2004. As the

school’s Grainger Observatory director, he manages the curriculum and instrument needs of the astronomy program, in addition to teaching four classes per term. His recent projects include working with Exeter students and the University of New Hampshire in the design and implementation of magnetometers to study minute changes in the Earth’s magnetic field due to solar activity.

“Through my own learning, I am able to improve the learning of my students and mentees,” he says. “This process is continual; the more I learn, the more my students have access to, and the more engaged and informed they will be about the sciences. Receiving this award is truly an honor.” ●

“His research has shifted the paradigm for brain monitoring during general anesthesia for surgery.”

“The more I learn, the more my students have access to, and the more engaged and informed they will be.”

Emery N. Brown ’74

Read more about Brown’s life and work by scanning this QR code.

FACULTY NEWS

Instructor in Science John Blackwell

Spring Break, World Edition

Students expand their horizons and perspectives on travel trips

All told, 85 students plus faculty members traveled together over March break to learn and grow.

One group explored Andean culture in the Secret Valley of Peru while another headed to the nation’s capital to learn about programs that address poverty, food access, housing and homelessness. In Alabama, a group studied civil rights, justice and the ongoing legacy of slavery. Latin and Greek students visited the ancient cities, temples, amphitheaters

Travel Trip Destinations

Washington, D.C.

Montgomery, Alabama

Northern Italy

Sicily and Campania

Machu Picchu, Peru

and markets of Sicily and Campania where the primary Latin and ancient Greek authors they study lived or worked.

But the most vocal group of Exonians of them all was the Concert Choir. Music Instructor Kris Johnson and 39 students made a weeklong trek through Northern Italy. Stopping in San Gimignano, Florence, Verona, Mantua and Venice, the group performed in stunning venues along the way — all while exploring both historic and contemporary Italian art, cuisine and culture. ●

Overheard on Instagram

@pea_choir_italy

“Today was action packed! Starting off with a viewing of the David and other masterworks, then moving over to Mantua to see the church in the palace of the duke where Monteverdi worked for over 20 years, then a tour of the palace itself, ending in the room he composed in. We sang in both the church and his workroom, and it was magical.”

To hear the choir singing in Italy scan this QR code.

The Exeter Concert Choir performing in Italy’s Duomo di Santa Maria Assunta in San Gimignano.

Identity and Reality

Artist Jeffrey Songco’s work reflects his personal and cultural origin story

If we could peek inside someone’s mind, what would we see?

Jeffrey Augustine Songco gives us a glimpse. His immersive work Society of 23’s Conservatory, which recently concluded a two-month run at Lamont Gallery, offers a tangible stream of consciousness for visitors to ponder. It is a conservatory in the greenhouse sense, replete with living foliage, but the plants are only one element of a multisensory installment that explores Songco’s complicated relationship between his identity as an American of Filipino ethnicity and U.S. colonization of the Philippines for a half-century.

The Society of 23 comprises a fictional brotherhood of 23 mysterious gentlemen, all portrayed by the artist — a play on Songco’s days in a fraternity as an undergraduate at Carnegie Mellon University.

The installment was host to several

PEA visiting classes and served as one of the workshops in the Academy’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day programming.

Songco says: “My artwork is a celebration of life. I work with a variety of media including large-scale installation, self-portrait photography, sculpture and video. My practice is rooted in a considered set of conceptual parameters that guide my thought and labor towards the final outcome of my autobiographical artwork. I share my reflections on how my mind and body are shaped by the identities and realities I have inherited and constructed myself. This dense layering of things reveals the forest of ideas I navigate and the conflicts I continue to resolve. Each of my artworks relate to one another in particular ways and evolve in their meaning as I continue to create the grand nonlinear narrative of my life.” ●

(Above) Acrylic flower sculptures in artist Jeffrey Augustine Songco's installation (Below) Songco in the Lamont Gallery

Immersive Theater

Behind the scenes of the winter term musical

“NEW ENGLAND WINTERS are tough,” says Lauren Josef, chair of the Theater and Dance Department. “We need joy. We need weird.”

Exeter’s performance of The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee brought all that and more to The David E. and Stacey L. Goel Center for Theater and Dance. The fast-paced and riotous musical featured six “middle schoolers” and audience participants who spelled their way through vexing vocabulary while sharing hilarious and poignant personal stories.

“I think one of the reasons this show has felt so special is because early on we said, ‘This is not going to be a traditional show,’ ” says Josef, the production’s director. “We told the students: ‘You’re going to be interacting with the audience. You might be throwing things. You’re going to be in character preshow and bringing everybody into this environment.”

Delivering such an immersive experience took creativity and collaboration. Here’s a behindthe-scenes look at the way the show took shape.

SETTING THE SCENE

Instructor in Theater and Dance Anthony Reed, the show’s technician, set designer and lighting designer, created an immersive environment outside and inside the Goel Center’s mainstage theater. “The phrase that we were working off of was ‘absurdity that looks like reality,’ ” he says. “Everything is just a little bit cartoonish, almost like a long-form SNL skit.” Reed designed the set to look like a middle school gym with lighting fixtures, a basketball court, even a Lost and Found bin. He also created the Screamin’ Squirrels mascot for the fictional school.

AUDIENCE IMMERSION

Some attendees were seated onstage (on bleachers hauled in from Hatch Field) and called to participate in the spelling bee. Student performers walked through the theater seating area, breaking the “fourth wall.”

CREW WARDROBE

Working with Instructor in Art Heather Hernon, Reed designed and screen-printed T-shirts for the crew.

STAGE

To make the stage look like a basketball court, Reed built a center circle that extended into the audience. He also hand-painted the floor to resemble hardwood. Visiting alumna Emma Aldrich Jordan ’17 pitched in to help. As a student, Jordan was a stage manager. She is now a scenic painter and props artisan.

MUSIC

With audience seating in the orchestra pit, Instructor in Music Kristofer Johnson and six musicians performed on stage. Computer monitors streamed live video of Johnson’s conducting so the actors could follow his direction. “The characters needed to be able to know when to sing or when to stop,” Reed says.

SOUND

“Each student actor has a body mic, so there are 22 mics,” Josef says. “ We have one student [Audrey Dent ’25] who is mixing. Audrey has to listen carefully. If

80 hours to paint a gym floor onstage

46 cast and crew members

22 body microphones

200 lighting cues

90 minutes running time

Faux hardwood helps transform the stage into a court.

Student actors interact with the live audience.

Custom T-shirts feature the fictional school’s mascot.

one student is being especially quiet during a scene or especially loud, she is live-mixing that. And then we have another sound person backstage, Angelina Wang ’27. If something malfunctions, if we need to fix a microphone, she fixes that.”

APPLIED SCIENCE

“A lot of the work that we do relies on computer science, on physics and these different technologies that students are learning about in the classroom,” Reed says. “In theater tech, they get to see how the light at a different angle is going to cast a pool of light on the stage and how big that pool will be. These are real-life applications for a lot of things they are learning.”

LIGHTING

Light operator Jiayu Wang ’25 was tasked with about 200 lighting cues: visual indicators to the performers that specific actions are supposed to happen at precise times. During the performance, actors rely on prompts to hit their marks and keep the show running smoothly. “So much of the storytelling in this show relies on lights,” Josef says. “Tony has a really stark difference between what the lighting looks like when you’re in the real world and in the character’s mind.” ●

Tech crew control light and sound from the booth.

Instructors in Theater Lauren Josef and Anthony Reed

Winter Highlights

→ BOYS BASKETBALL

Second in New England Class A Record: 20-4

Head Coach: Jay Tilton

Assistant Coaches: Rick Brault, Harry Rafferty, Phil Rowe

Captains: Max Albinson ’25, Tyler Bike ’25, Ryder Frost ’25

MVPs: Tyler Bike ’25, Ryder Frost ’25

↑ GIRLS BASKETBALL

Record: 5-16

Head Coach: Katie Brule

Assistant Coaches: Mireya Boutin, Kerry McBrearty

MVP: Ava Bryan ’25

← BOYS HOCKEY

Record: 13-15-1

Head Coach: Peter Ferriero

Assistant Coaches: Brandon Hew, Tim Mitropoulos ’10

Captains: Will Cavanagh ’25, Dryden Dervish ’25, Cam Fiasconaro ’26, Luke Zucker ’26

MVP: Will Cavanagh ’25

↓ GIRLS HOCKEY

Record: 14-9-2

Head Coach: Sally Komarek

Assistant Coaches: Adam Loyd, Jim Tufts

Captains: Allie Bell ’25, Grace Benson ’25, Maria Gray ’26

MVP: Allie Bell ’25

→

BOYS SQUASH

Record: 11-9

Head Coach: Bruce Shang

Assistant Coach: Paul Langford

Captains: Max Liu ’26, Bryan Huang ’25

MVP: Evan Chen ’28

→

GIRLS SQUASH

Record: 7-7

Head Coach: Lovey Oliff

Assistant Coach: Mercy Carbonell

Captains: Erin Chen ’25, Aria Suchak ’25, Paloma Sze ’25

MVP: Mathilde Senter ’26

←

BOYS SWIMMING & DIVING Record: 8-1

2nd place in New England

New England Diving Champion (Nick Limoli ’26)

Head Swimming Coach: Don Mills

Assistant Swimming Coaches: Nicole Benson, Meg Blitzshaw, Kate D’Ambrosio

Head Diving Coach: Julie Van Wright

Assistant Diving Coach: Steve Altieri

Captains: Ethan Guo ’25, Winston Wang ’25, Nick Limoli ’26

Swim MVP: Ethan Guo ’25

↑

BOYS INDOOR TRACK & FIELD

Head Coach: Hilary Hall

Assistant Coaches: Marvin

Bennett, Steve Holmes, John Hoogasian, Patrick Kelly, Brandon Newbould, Xiana Twombley, Panos Voulgaris

Captains: Jaylen Bennett ’25, Pearce Covert ’25

MVP: Jaylen Bennett ’25

←

GIRLS INDOOR TRACK & FIELD

Head Coach: Hilary Hall

Assistant Coaches: Marvin

Bennett, Steve Holmes, John Hoogasian, Patrick Kelly, Brandon Newbould, Xiana Twombley, Panos Voulgaris

Captains: Leta Griffith ’25, Jannah Maguire ’25

MVPs: Jannah Maguire ’25, Gianna Phipps ’25

↑

GIRLS SWIMMING & DIVING New England Champions Record: 9-0

Head Swimming Coach: Don Mills

Assistant Swimming Coaches: Nicole Benson, Meg Blitzshaw, Kate D’Ambrosio

Head Diving Coach: Julie Van Wright

Assistant Diving Coach: Steve Altieri

Captains: Briana Cong ’25, Sophie Phelps ’25, Ellie Colman ’26

Swim MVP: Mena Boardman ’26

Dive MVP: Alison Benson ’25

↑ WRESTLING Record: 8-10

Head Coach: Justin Muchnick

Assistant Coaches: Bob Brown, Tom Darrin

Captains: Jack Breaks ’25, Becket Moore ’25

MVP: Bella Bueno ’25

Byran Huang ’25 spent “a couple thousand” hours building his open-source laptop.

Achieving Excellence

Curiosity and hard work earn students accolades in computer science, math, music and more

By Adam Loyd and Sarah Pruitt ’95

Computer Science

Senior Builds Laptop from Scratch

What started as “betcha can’t” on a team bus trip to a squash match turned into a yearlong passion project for Byran Huang ’25. After accepting a teammate’s challenge to build a computer from scratch, he says he spent “a couple thousand” hours meticulously planning, building and testing nearly every element of his custom opensource laptop. Huang calls it anyon_e.

“I thought about all the projects I’d done in the past — building circuit boards, power systems and data systems,” he says. “This felt like a capstone to all that, a magnum opus.”

Huang parlayed his pursuit into a sanctioned senior project, receiving support from the Academy. He worked extensively in the Design Lab in the Phelps Science Center and spread his materials in the back of Steyer Distinguished Professor Brad Robinson’s physics classroom. “I received amazing funding,” Huang adds. “I blew my budget two and a half times over and nobody batted an eye. The school was constantly there to support me.”

It was important to Huang not only that his laptop be fully functional, but also that his process was easy for others to replicate. “This is a time when technology is innovating so fast, but people don’t get access to how to create things openly,” he says. “I wanted to go on this journey to publish everything I had made for the world to share.”

Huang produced a YouTube video, “How I Made a Laptop From Scratch – anyon_e,” detailing every step of his building process. Among the more than 1 million views was a Neuralink engineering lead who recruited Huang to intern with the Robot Surgery Electrical Engineering team this summer.

Like any good scientist, Huang is taking what he learned from this experience and hoping to refine the process. “I’m really looking forward to building a second version of this laptop that’s affordable,” he says. “Something you can build in your house from scratch.”

Huang is quick to credit the Academy as an inspiration, saying, “Exeter has always been this place that I’ve felt has magical powers to push you to discover more you didn’t know you were capable of doing.”

Civics

Debater Heads to Global Championship

For the third consecutive year, an Exonian competed on the global debate stage. Andrew Gould ’26 headed to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in late March for the World Individual Debating and Public Speaking Championship.

Co-head of the Academy’s Daniel Webster Debate Society, Gould qualified for the international tournament through his stellar performance at various debate events throughout the school year, including a first-place duo team finish alongside Jinmin Lee ’26 at

St. Paul’s School, where they debated a resolution stating that the United States should increase its military presence abroad.

“We ran a counterplan to throw off our opponents,” Gould says. “As the opposition, we argued that the U.S. should increase its military presence to uphold global prestige, especially in the face of revisionist states like Russia or China. We also argued that if countries currently reliant on U.S. military and nuclear protection were to be abandoned by the U.S., they would develop their own defenses, and even potentially their own nuclear arsenal. Those aren’t necessarily our personal views, but researching and building that

counterplan was incredibly eye-opening. It gave me a deeper appreciation for the delicate balancing act that is foreign policy.”