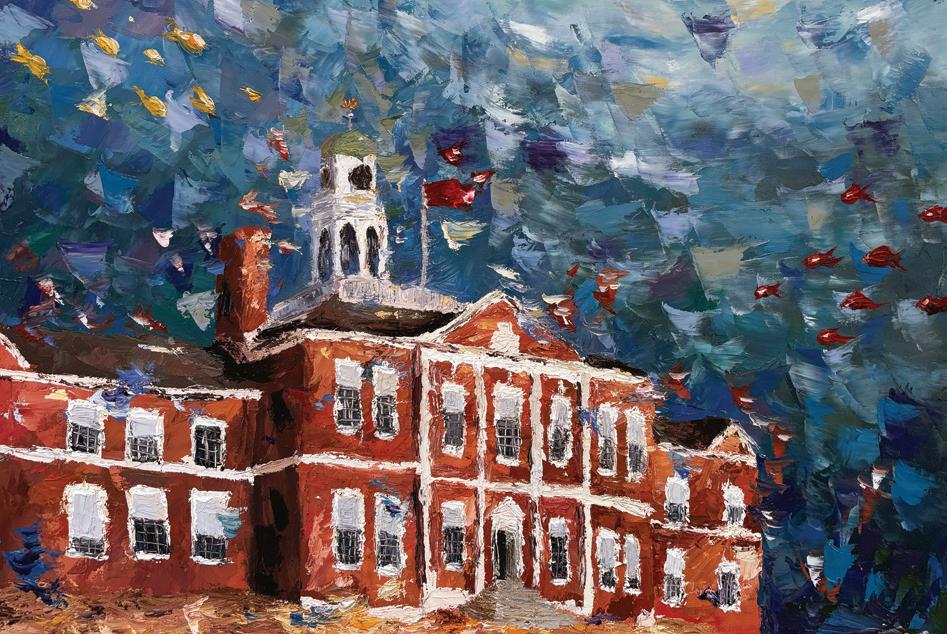

THE DAVIS BUILDING REIMAGINED

FALL 2025 / CONTENTS

FEATURES

The Power of Struggle

How trial and error and, yes, failure are essential to learning.

Sarah Pruitt ’95

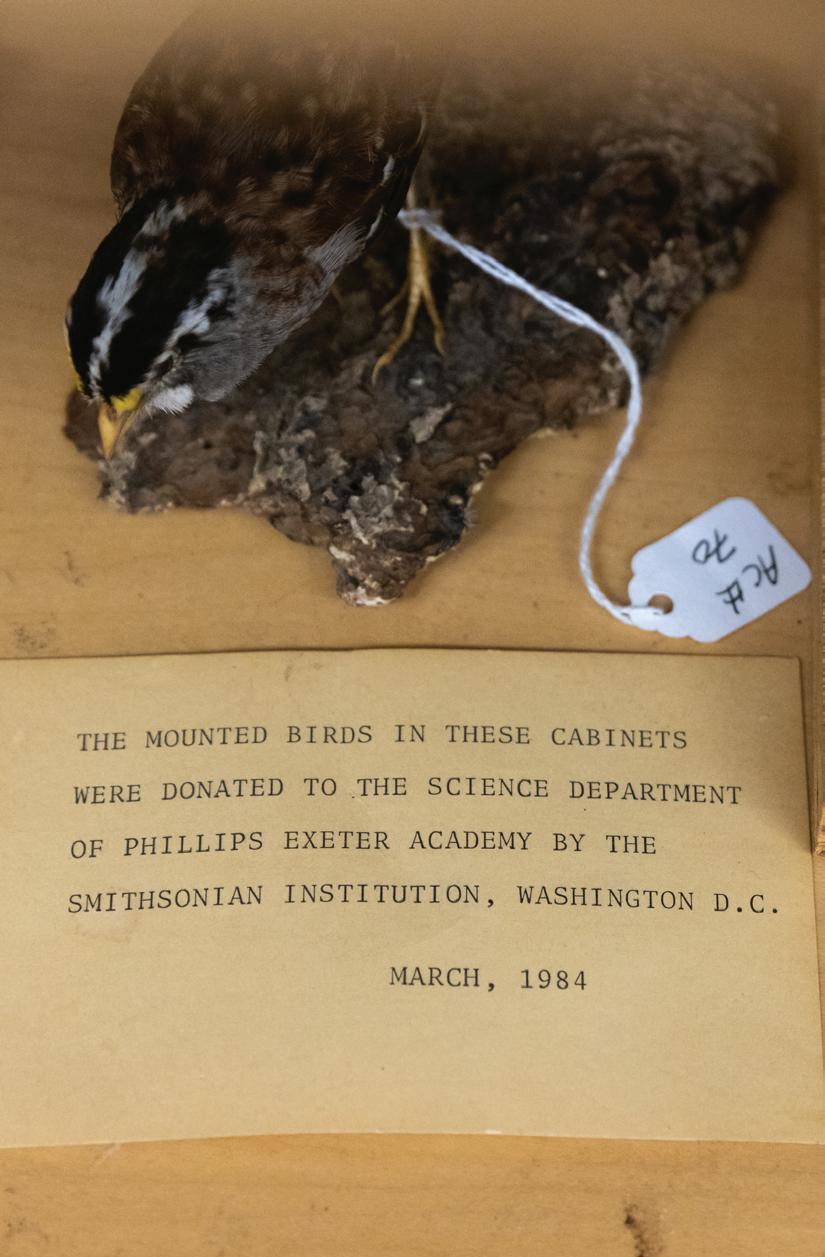

32 Cabinets of Curiosities

Exeter’s vast and distinctive specimen collections spark active learning and exploration.

Jennifer Wagner

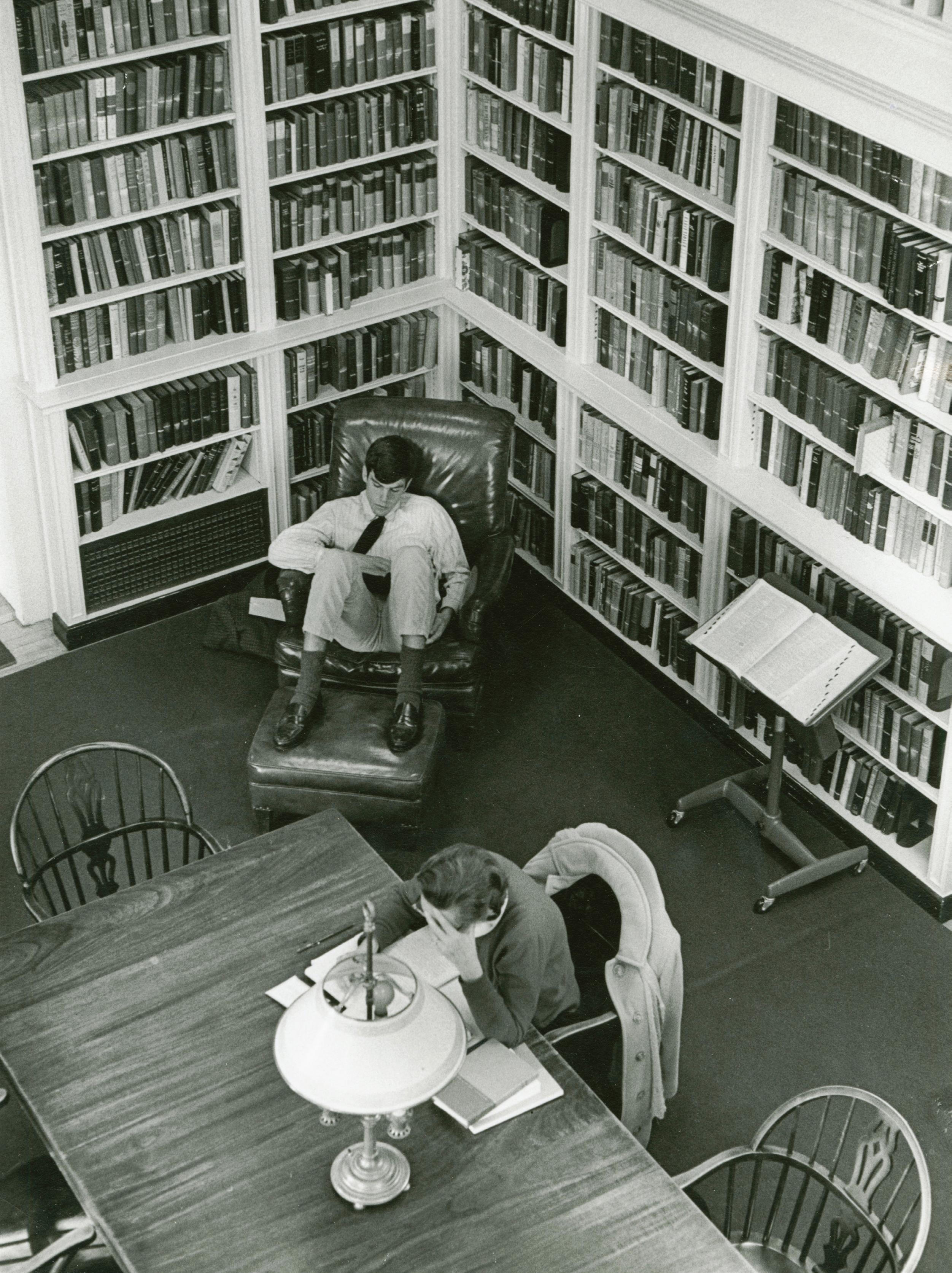

38 Preserved in Stone, Reimagined in Spirit

A yearlong renovation transforms the 113-year-old Davis building.

Debbie Kane

44

“One of the things that we value in the math classroom is risktaking and daring to be wrong. The process of getting to an answer is where the thinking happens.”

Panama Geer, Math Department chair, p. 32

A bin in the Design Lab is jokingly called “the bucket of failure”: a physical symbol of the students’ trial-and-error and problem-solving process. P. 32

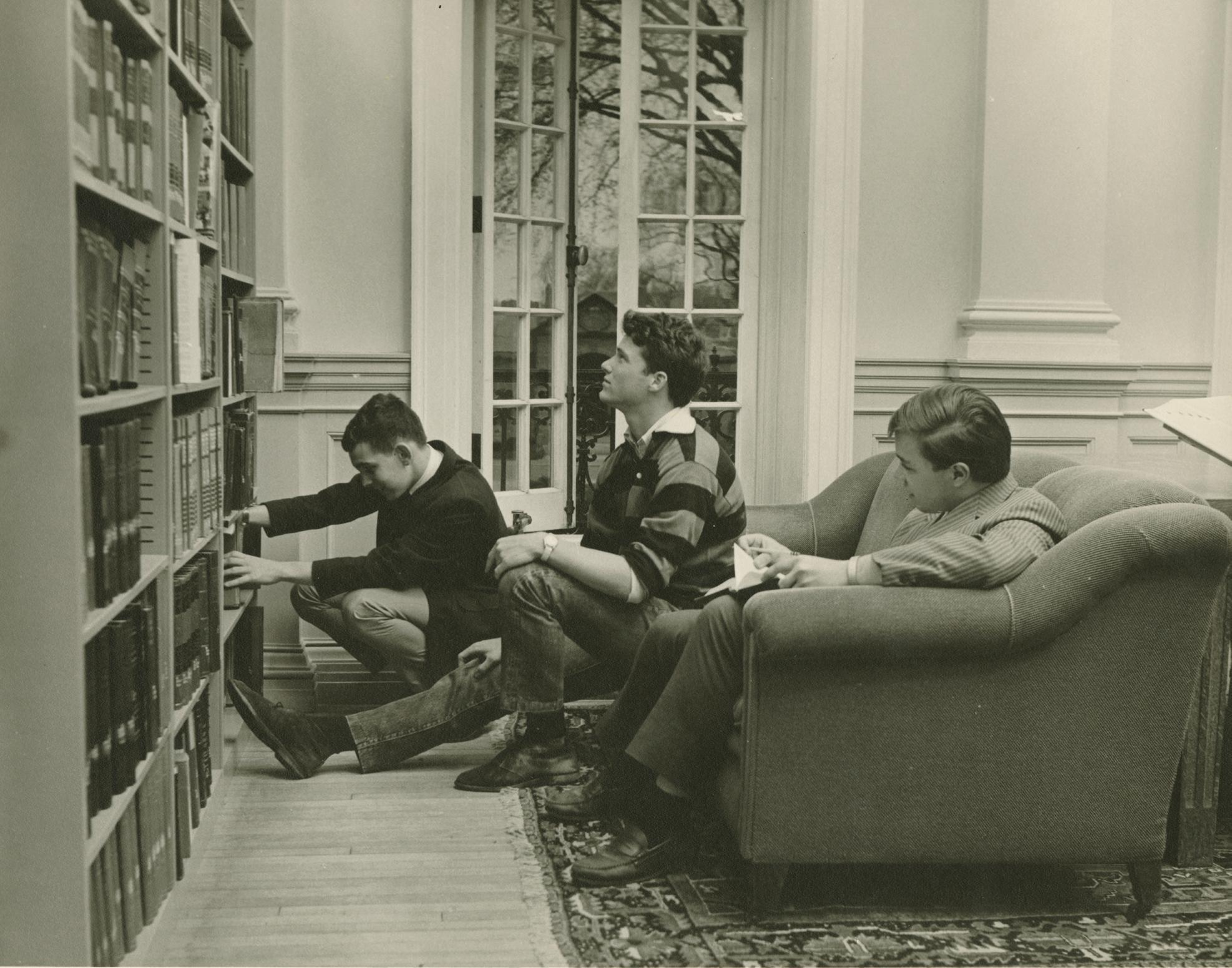

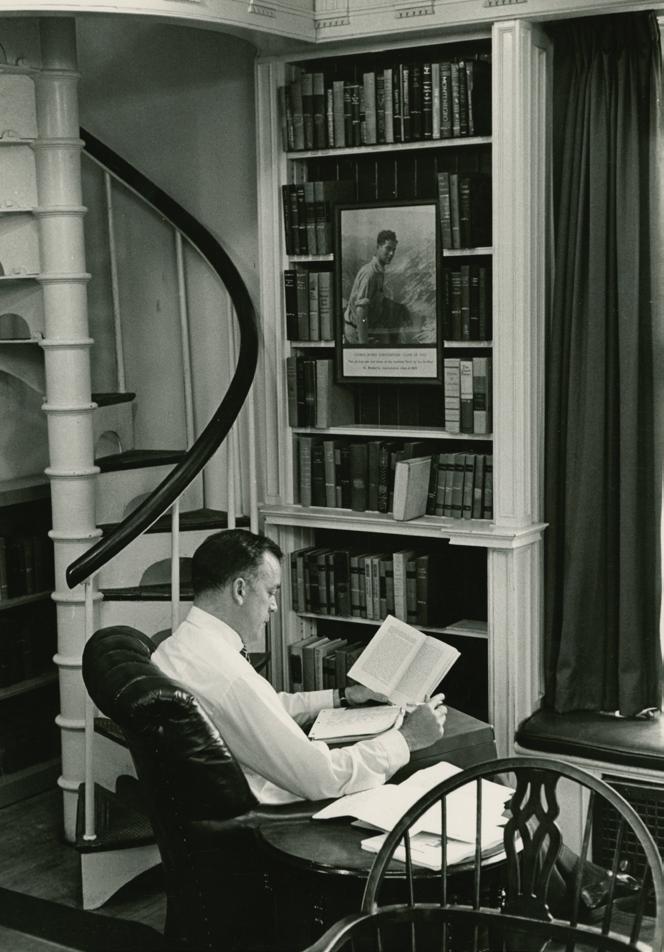

Cover: The Mary Amen Study in Davis Hall; Photography by Amanda Sagba Back cover: Davis Library in 1965; Photography by Bradford Herzog Kotryna

5

Around the Table

Correspondence ∙ Principal’s letter ∙ A conversation with Dan Brown ’82

∙ English Instructor Erica Plouffe

Lazure on Thompson Field House

∙ Theater Instructor Rob Richards’ classroom ∙ Faculty in Iceland ∙ AI through a literary lens with English Instructor Tim Horvath

∙ Exoniana ∙ Exonians in review ∙ Robert Cowley ’52 on the Western Front

21

The

Academy

Health fair ∙ Faculty appointments

∙ Senior advice for preps ∙ Academy Life Day ∙ Lamont Gallery fall exhibit

∙ Global Initiatives trips ∙ Former senator Jeff Flake speaks at assembly

∙ Principal search update ∙ Mock Trial champs ∙ Aruth Chinsupakul ’26 makes soap to soothe eczema

51

Connections

Microroaster Nicholas Benson ’84 ∙ Religious historian Annette Yoshiko Reed ’91 studies forgetting ∙ Geologist Art Curtis ’71 advocates for clean energy ∙ Events around the world

61

Class News and Notes

102

Memorial Minute

John Joseph Kane

104

Finis Origine Pendet

The Exeter Bulletin

Volume CXXX, Issue no. 1

Principal

William K. Rawson ’71; ’65, ’70 (Hon.); P’08

Director of Communications

Robin Giampa

Editor in Chief

Jennifer Wagner P’24

Class Notes Editor

Cathy Webber

Contributing Editor

Patrick Garrity

Staff Writers

Adam Loyd, Sarah Pruitt ’95

Production Coordinator

Ben Harriton

Designers

Red Ink Design, Jacqueline Trimmer

Photography Editor

Christian Harrison

Communications Advisory Committee

Daniel G. Brown ’82, Robert C. Burtman ’74, Dorinda Elliott ’76, Alison Freeland ’72, Yvonne M. Lopez ’93

TRUSTEES

President Kristyn A. McLeod Van Ostern ’96

Vice President Suzi Kwon Cohen ’88

Bradford “Brad” Briner ’95, Samuel “Sam” Brown ’92, Elizabeth A. “Betsy” Fleming ’86, Ira D. Helfand, M.D. ’67, Paulina L. Jerez ’91, Giles “Gil” Kemp ’68, Eric A. Logan ’92, Eugene “Gene” Lynch ’79, Cornelia “Cia” Buckley Marakovits ’83, William K. Rawson ’71, Christine M. Robson Weaver ’99, Genisha Saverimuthu ’02, Michael J. Schmidtberger ’78, Peter M. Scocimara ’82, Leroy Sims, M.D. ’97, Rhoda K. Tamakloe ’01, Belinda A. Tate ’90, Janney Wilson ’83

THE EXETER BULLETIN (ISSN No. 0195-0207) is published four times each year: fall, winter, spring and summer, by Phillips Exeter Academy, 20 Main Street, Exeter, NH 03833-2460

Tel: 603-772-4311

Periodicals postage paid at Exeter, NH, and at additional mailing offices. Printed in the USA by Cummings Printing.

The Exeter Bulletin is sent free of charge to alumni, parents, grandparents, friends and educational institutions by Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, NH.

Communications may be emailed to the editor at bulletin@exeter.edu.

Copyright 2025 by the Trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy. ISSN-0195-0207

Postmasters: Send address changes to: Phillips Exeter Academy, Records Office 20 Main Street, Exeter, NH 03833-2460

Dormmates dreamed up a new game to play at Jenness Beach on Academy Life Day. P. 25

Historian and Muay Thai fighter Annette Yoshiko Reed ’91, P. 53

Place of Honor

The 150-year-old Second Empire-style mansion on Front Street — formerly known as Front Street Dorm and home to two dozen boarding students and six to eight day student affiliates each year — has a new name: George H. Guptill ’57 House.

It’s a fitting tribute to a generous alumnus and longtime supporter of the Academy. Guptill is a since-grad donor and has long enabled students from his native Raymond, New Hampshire, to attend the Exeter Summer academic enrichment program. He has also made significant gifts to the Academy Music Department: a 1927 Steinway Model M piano and a commissioned Taylor & Boody Continuo pipe organ.

Guptill, who today lives in Exeter, knows support for buildings and infrastructure is an institutional priority, and he relishes that a former day student’s name adorns one of the Academy’s dorms.●

Lamont Gallery – 2025-2026 Exhibitions

StrangeKin

September 2 – November 22, 2025

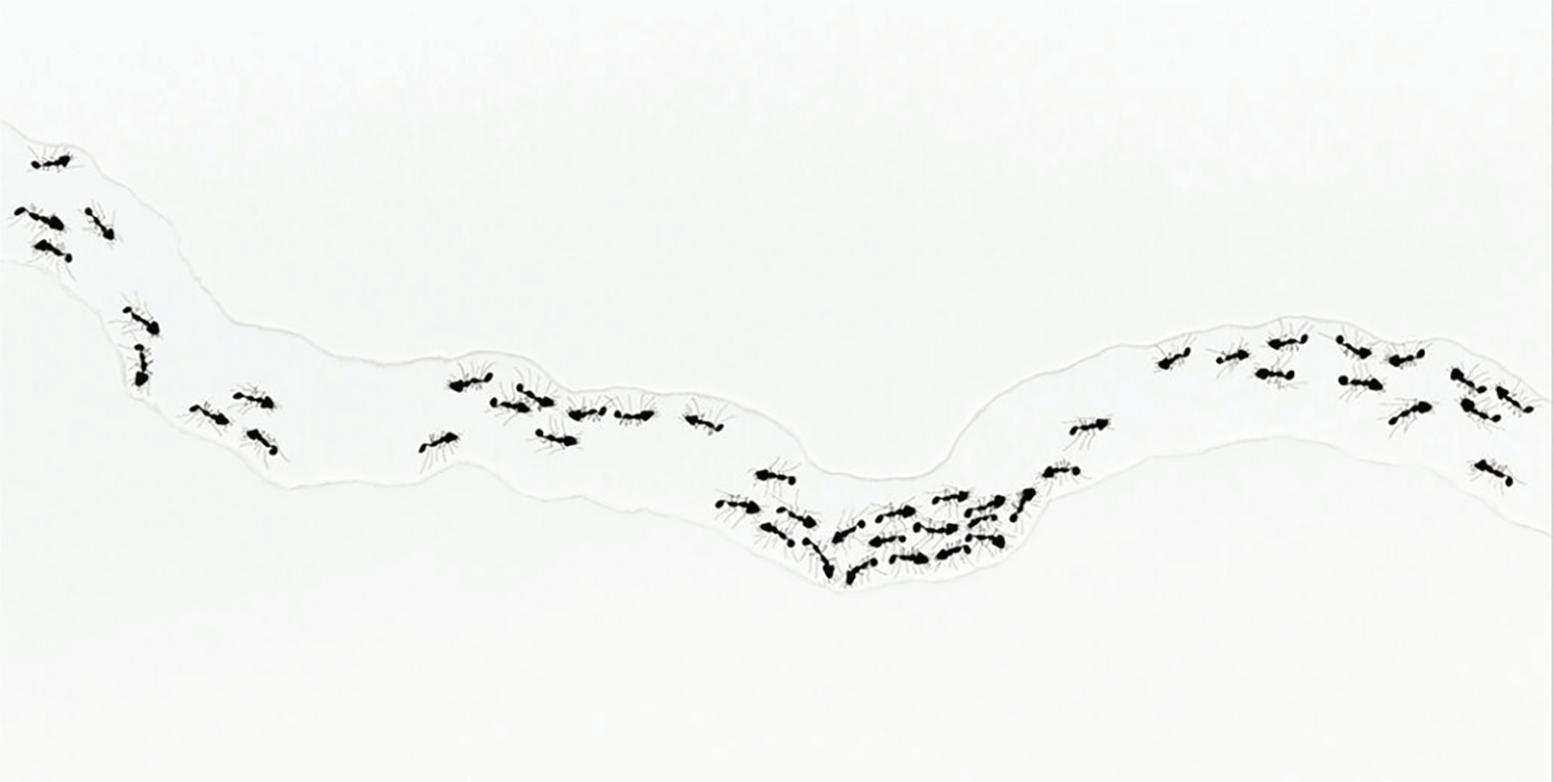

Strange Kin is a swarm of tiny critters that playfully inspect and reimagine the miniature marvels that live among us. The five artists on view explore how creatures, ranging from crickets to bees, can work within an artistic practice rather than merely being the inspiration for it.

Kate Kato, Outnumbered Collection, 2018, recycled paper, wire and thread

MoeGram:PartyFouls

January 5 – March 7, 2026

Party Fouls explores the games and pains that come with growing up. Themes of play, frustration, empathy and self-compassion compete against each other in fields of color and found objects. Ultimately, we learn the journey never ends, it just evolves.

Moe Gram, courtesy of the artist

Advanced Student Art Exhibition

May 14 – June 7, 2026

This annual exhibition features the hard work and creativity of Exeter’s visual arts students enrolled in advanced studio courses.

Lamont Gallery

Frederick R. Mayer ’45 Art Center

The Lamont Gallery is open to the public by appointment. Please visit our website to learn more and make a reservation.

exeter.edu/lamontgallery | gallery@exeter.edu |

Freddie Chang ’25, Sharkitecture, 2025, oil on canvas; Tallis Guthrie ’25, Piper, 2024, stoneware and underglaze (from the 2025 Advanced Student Art Exhibition)

Around the Table

Puppeteer Visit Instructor in Theater Rob Richards’ classroom. P. 12

A custom-made puppet comes alive in Theater Instructor Rob Richards’ deft hands.

Letters to the Editor

I appreciated your column (“Behind the Lectern,” summer 2025) about memorable assembly speakers. For me, hearing Jewish Holocaust survivor and author Elie Wiesel was profound and deeply important. If I remember correctly, Wiesel came to Exeter in 1980 to speak and meet with students. I had read his book Night in my eighth-grade year, and I had learned extensively about the haunting and terrifying descriptions of the Nazi concentration camps with my teachers and classmates in my synagogue’s afterschool program.

When Wiesel came to Exeter, his very presence with his quiet demeanor, his dignity, his Romanian accent, and the experiences he referenced in Auschwitz made his talk especially memorable. My fellow Jewish students and I felt privileged and proud to hear this vitally important, universal message. Few assembly speakers brought the level of moral authority and gravitas that he did as he warned us about the dangers of baseless hatred, prejudice and totalitarianism that he had experienced firsthand in Nazi Europe.

Our teachers pointed out that what happened during World War II was the embodiment of the danger that comes from “knowledge without goodness.” His visit shaped some of my own commitments in my present career as a rabbi and high school Jewish theology and ethics teacher.

Judd Kruger Levingston ’82

Maybe I’ll be the only alumnus to remember this Chapel/assembly speaker oddity: Dr. Tom Dooley of the U.S. Navy. Dooley was an early “propagandist” for U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. I was a junior when he spoke in Chapel late in 1959.

Dooley was famous. He was featured in the Dec. 15, 1958, issue of Life magazine. He toured the country, presented as a national hero, a patriotic, anti-communist crusader, brought home to raise money and awareness for his clinic in the jungles of Laos. He was non sibi incarnate.

But in person, even to this 14-year-old political neophyte, something seemed “off” about Dooley. He was obsessed, singularly fanatic. Maybe for this reason, I found his presentation striking and memorable. But I never heard anyone, student or faculty, ever mention his appearance on campus. Shortly after his Chapel speech, he just disappeared from the public spotlight and just seemed to vanish. Over the years, I sometimes remembered and wondered, what happened to that guy?

Well, his story represents an intriguing and revealing footnote to our nation’s history. Dooley was very quietly discharged from the Navy and public attention. Scott Wild ’62

I was delighted to see that what I knew as St. Gurdon’s Day (195862) continues as Principal’s Day, briefly enlivening the dark days of New England winter (“Principal’s Day,” summer 2025). In those days, however, the holiday was never announced on the eve, giving the day a touch of the casino. Folks would try to guess which day was going to be St. Gurdon’s and back that bet by skipping their homework, often with tragicomic results.

The day is burned into my mind because one year my classmate, the late Jimmy Leader, and I decided that in the event of the big announcement, we would race over to grab a squash court as soon as Chapel was concluded. During the ensuing first game, in rushing to control the T after Jimmy’s shot, I forgot that he was left-handed and stopped his follow-through with my upper incisors. My teeth since then have been more photogenic and largely prosthetic.

Daniel F. Melia ’62

We want to hear from you! The Exeter Bulletin welcomes story ideas and letters related to articles published in recent issues. Please send your remarks for consideration to bulletin@exeter.edu or Phillips Exeter Academy, The Exeter Bulletin, 20 Main Street, Exeter, NH 03833.

Empathy and Gratitude

At Opening Assembly this year, I told new and returning students the same three things I tell new and returning students every year: You can do the work. You will make lifelong friends. Absolutely, you belong here.

Following Academy tradition, I then spoke of our school’s mission — to unite goodness and knowledge and inspire youth from every quarter to lead purposeful lives — and reflected on our five core values — knowledge and goodness, academic excellence, youth from every quarter, non sibi and youth is the important period — all of which can be traced to our Deed of Gift, written 244 years ago.

I then spoke about the importance of empathy in all that we do and all we seek to accomplish at Exeter. As I told the students, empathy is important because it opens our hearts and minds to the kind of learning and growth that we seek to encourage at Exeter. It helps us to be curious about how and why others might see the world differently.

Empathy is fundamental to our Harkness pedagogy. It helps us learn to be comfortable having our thoughts and ideas tested by others whose ideas, perspectives, experiences or identities are different from our own. In this way, it leads to deeper learning, greater personal growth, more effective leadership, and more meaningful contributions to the lives of others.

I hope that our students — this year and every year — lead with empathy in all they do.

At my first Opening Assembly as principal seven years ago, I told the students, “We are not special merely because we are here, but because we are here, we have the opportunity to do special things together.” I repeated that sentiment this year, and I added that I will be excited to see what special things our students will do in the coming months and over the course of the year. I promised them that I will be there every step of the way, cheering them on alongside their teachers, advisers, coaches and other mentors.

As I begin my last year as principal, I find that I don’t want to wait until the end of the year to

express my deep gratitude for the encouragement and support that I have received from the entire Exeter community — on and off campus — during my time here. We all seek purpose and meaning in our lives. Having the opportunity to help this school change the lives of our students, as Exeter changed my life many years ago, has been deeply meaningful to me. I am grateful for the many ways we have worked together, motivated always by a deep commitment to the mission of our school and an abiding belief in the capacity of our students to take what they have learned here and make a positive difference in the world.

“Having the opportunity to help this school change the lives of our students, as Exeter changed my life many years ago, has been deeply meaningful to me.”

I have been asked several times in recent months about my plans for my final year. We have important work to do and projects to complete, as is the case every year, but our main objective is always to be the best Exeter we can be. I closed Opening Assembly by saying: “Let’s commit ourselves to the mission and values of our school and approach each day with gratitude in the spirit of non sibi. Let’s aim high, have fun and find joy in all we do.”

That’s my plan.

—Bill Rawson ’71; ’65, ’70 (Hon.); P’08

Principal Bill Rawson takes the lectern at Opening Assembly.

Stream of Consciousness

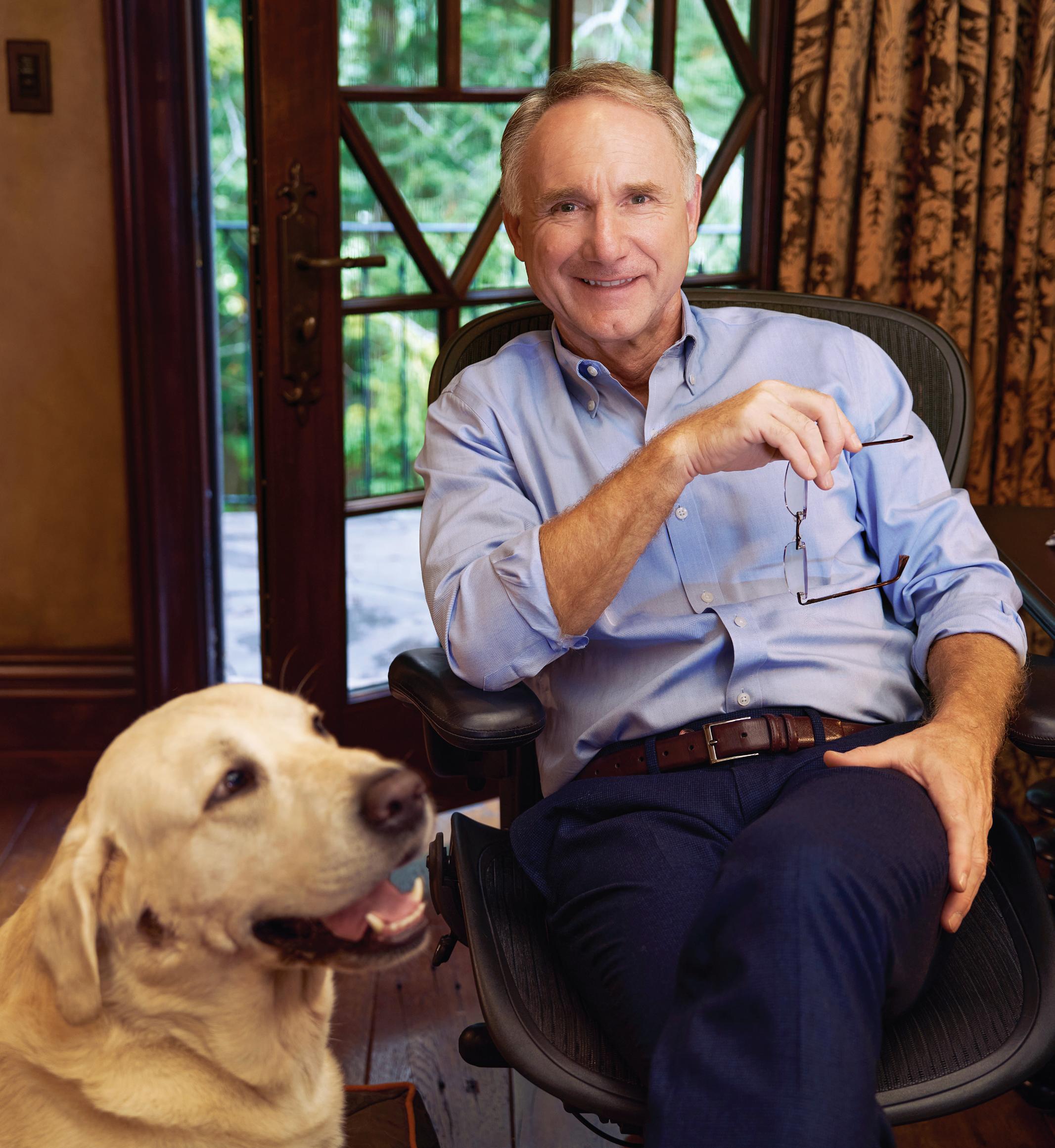

A conversation with novelist Dan Brown ’82

In his latest mystery thriller, The Secret of Secrets, Dan Brown ’82 thrusts intrepid symbologist Robert Langdon into a race for his life through the mystical city of Prague, where ancient lore, cutting-edge science and the very nature of human

consciousness collide. In an interview with former English Instructor Matt Miller for The Exeter Bulletin , Brown opens up about the new novel, his writing process, AI, his upbringing as a “fac brat” and what it means to move beyond the limits of physical mortality.

The last installment of your Robert Langdon series came out eight years ago. What does it feel like to return to that character?

It’s like I never left. He and I share a lot of the same passions: history, art, codes, treasure hunts. I live vicariously through him. I sit alone in the dark with a computer, and he runs around the world. It’s a lot of fun.

The book explores the noetic sciences, a multidisciplinary field that studies subjective experience and consciousness using scientific methods. What drew you to that subject?

I wrote a book called The Lost Symbol about 12 years ago in which there was a character, Katherine Solomon, and she was a noetic scientist. As I was writing that character and learning a little bit about noetics, I thought, oh my god, human consciousness is a book in itself. I thought it would be the book I wrote after The Lost Symbol, but it was too hard. I didn’t know enough about consciousness. I never imagined it would take eight years, but it’s an ethereal topic. I always felt like I was trying to get my arms around smoke, just trying to figure out how to write this.

It’s a deeply researched book. Was there some “aha!” point when you knew this subject had to be the subject?

I read about an experiment in precognition where different parts of the brain light up when you see different kinds of images. In the study, the brain was lighting up before an image was seen. So, what does that mean? Perhaps the brain is creating what image to see. Or there was precognitive knowledge of what was about to be seen. Or perhaps time flows in two directions. Any of those answers, and you’re like, what? None of that makes sense. This experiment made me really think that, from a personal level, I had to understand consciousness. And as a writer, I had to figure out how to share it in a fun package.

How do you balance getting all that researched information about politics, history, science, physics and metaphysics into the novel while also moving forward narrative action and character development?

You make sure that the data dump that you are performing is directly relevant to whatever character you’re writing about. Langdon could be walking down the street and think, oh, Petřín Tower, and I give a two-minute dissertation on Petřín Tower, which feels like an aside, and that’s boring. The information has to be part of solving a puzzle. It must be linear to the plot, not ancillary. And don’t

“Setting is critical. Location is a character. ... When I decided to write

about consciousness,

I knew it had to

be Prague.

Prague has been the mystical center of Europe since the 1500s.”

fall in love with your research. If it doesn’t serve the plot, it goes.

That’s the toughest thing for writers, knowing what to cut.

The delete key has to be your best friend. Any artist or musician understands the importance of blank space or silence. The rests and silences give the melody to that place. It’s the same way in writing. You need to let your writing breathe.

You thank your editor Jason Kaufman in your acknowledgments. Does an editor, like a writing teacher, help you see where you need to pull back or where you need more?

That’s exactly what Jason does. He’ll read something and say: “Hey, this is great, but we don’t need four paragraphs about Prague Castle. We need two.” Then he’ll also say: “Oh, you just glossed over this thing. I want to know more about that.” He not only shares my taste, he has perspective, which is what you lose as a writer. It’s nice to have somebody come in and read it as a first-time reader, which is really the only way to know how it’s reading at all.

The Secret of Secrets is set in Prague. What drew you to that city?

Setting is critical. Location is a character. Prague has a personality, as does Paris, as does the Arctic Circle. Wherever you’re setting a book, it needs to be integral to the plot. When I decided to write about consciousness, I knew it had to be Prague. Prague has been the mystical center of Europe since the 1500s, when Emperor Rudolf recruited mystics to come to Prague to talk to the Great Beyond. As far as character goes, Prague is perfect for a Langdon book. There are passageways and a door with seven locks and crypts and cathedrals and all sorts of secrets.

The Secret of Secrets, by Dan Brown ’82, is the sixth installment in his Robert Langdon book series, including Angels & Demons, The Da Vinci Code, The Lost Symbol, Inferno and Origin. Brown’s novels are published in 56 languages with over 250 million copies in print.

“If we can start to understand that this life is just one stop on a much bigger journey ... then it’s quite possible that humanity could move forward in a benevolent fashion.”

As Langdon learns more about the nature of nonlocalized consciousness, I kept thinking about artificial intelligence. If AI could develop consciousness, where would that consciousness come from? Is it created? Is it tapped into? Can we create artificial consciousness? When you have enough synapses, does it just happen? It seems unlikely that it just happens. And this whole new model of the brain as a receiver of consciousness changes everything because if we’re trying to build an AI to receive consciousness, it’s a much easier proposition. It’s not like you have to build something that can create all the hopes and dreams and creativity and memories and all that. You just have to receive it. I actually think that this model of consciousness is pretty exciting and makes the quest for artificial consciousness more attainable, as well as consciousness after bodily death.

It’s always out there. You’re just tapping into it. It’s always out there.

Not to give too much away, but there’s a fascinating section in the novel about halos and how they are rendered in art. Langdon saw the beams of light as emanating out of halos. But then he realizes he may have misread the images, that the beams are radiating back into the halos, and that is consciousness coming in. Right. And if you read Scripture, really any religion, one receives the word of God. You don’t conjure God; God flows in. And we kind of miss that. That could be consciousness flowing in because it is not housed within the brain, as materialists presume, but outside the brain.

You have a golem character. In the Jewish tradition, the Golem is a created being, an artificial intelligence with consciousness.

Yes, one of the reasons I chose the Golem is that it’s this inanimate object that can be infused with consciousness just by writing a magic symbol, or a code, on its forehead.

The novel makes several sly references to the Academy, such as the rampant lion, the Ioka Theater, the bow-tied Oxford scientist named Townley Chisholm.

[Laughing] I haven’t heard from Townley. We’ll see how long it takes him to hear about that.

What about your experience as a student and growing up on campus makes you want to weave in some of those allusions to PEA?

I grew up in Bancroft Hall and then Moulton House. All the adults in my life were teachers. All my early babysitters were students. It was very normal for me as a child to talk to people from all different backgrounds, and this shaped an open-minded desire to look at international locations and different religions and beliefs. I’m fascinated with all that. When you grow up in the dormitory and you’re a fac brat, all the authority figures in your life are educators. When it came time to write a hero, I wanted to write a teacher.

Do you think that this novel and its topic of a nonlocalized consciousness may have a particular prescience in these times?

I hope so. There’s no bigger topic than human consciousness. It’s the lens through which we experience reality, experience ourselves and other people. The fear of death is the universal fear. Religious or atheist, we all are curious and unsettled by the fact that our lives are finite. This notion of what happens when we die is the big question. If we can adopt a mindset where we realize that human consciousness survives death, maybe some of that fear starts to dissolve. And the thing about the fear is that it’s really the catalyst for a lot of bad behavior.

Do you believe in this idea you bring up in the novel that if consciousness transcends our physical self, then we can move beyond the borders of mortality and by doing so move beyond the borders between each other?

Yes, I do. If we can start to understand that this life is just one stop on a much bigger journey, bigger than things like nationalism, country, race and all those things that separate us, then it’s quite possible that humanity could move forward in a benevolent fashion.

—Matt W. Miller P’23 is an award-winning poet, essayist and educator. He taught English and coached football at the Academy for 18 years and is currently an associate lecturer in creative writing at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

FACULTY REFLECTION

Field, House

English Instructor Erica Plouffe Lazure tracks the morning light with words and photographs

The beams from the east arrive most mornings at Thompson Field House, carving light and shadow into secret, fleeting architecture. As the “giver of all presences,” the interplay of light begins just after sunup, when the long column windows facing the fields refract into golden portal doors that span the court’s fishnet scrim, landing finally in translucence along the gymnasium’s tall “EXETER” wall.

Here, beyond the more constant, girder logic of physics, the fact of gravity, and the function of cement and stone, lies another gift, one that the architects must have anticipated, as they accounted for the layers of purpose in this space: one that marks the morning’s natural arc of time and path, pattern and pace, light and shadow.

And on this one morning, it’s just past six, and soon the overhead fluorescence will cast its film onto the quiet, constant geometry of the crimson track that measures pace in meters. By then, the sun will have landed its golden gaze elsewhere and the space will teem with relay runners and catchers, rowers and cross-trainers, dashers and hurdlers. Later it will lure Academy families with wobbling tots drawn to the long-jump

“I sense Light as the giver of all presences, and materials as spent Light. What is made by Light casts a shadow, and the shadow belongs to Light.”

Louis Kahn, architect of Exeter’s Class of 1945 Library

sand pit, to the stretch of red that lets them run and run and run until naptime, until the big kids come for their splits and drills.

But now, in the morning quiet, a solitary runner lopes along the ovular path, observing the cathedral-height walls, the exposed rafters and impossibly gleaming windows, the pairs of slanted support beams that offer the unmistakable mark of masons: the sacred tools of learning and precision. And then she spots a neon ball beneath a bleacher, a spindly shadow cast by a pair of chairs near the tennis court. She notices how each edge of sand in the jump pit ripples liquidlike in shadow, how the layers of netted scrim lend an echo to a Louise Bourgeois creation. There’s possibility in this space. And then, as the last crosshatch of morning light sprawls a butterscotch pattern across the tennis court, evidence of compass and ruler are everywhere, in fast-fading scalene and oblong, as the shadow and light fade, inevitably, into one.

Erica Plouffe Lazure came to Exeter as the Bennett Fellow in 2009 and has taught English at the Academy since 2010. She is the author of a short story collection, Proof of Me and Other Stories.

The Storyteller’s Stage

A behind-the-scenes look at Instructor in Theater Rob Richards’ classroom

Instructor in Theater Rob Richards is a storyteller at his core, and the relics in his second-floor classroom are his muses. “That mask is from Venice,” he says, picking up a Shakespearean-looking headpiece from behind his desk in The David E. and Stacey L. Goel Center for Theater and Dance.

The many artifacts, acquired during Richards’ travels or past performances,

aren’t idle. Students regularly interact with a figurine or an old stage prop on display, something Richards relishes and encourages. “I like to have creative things accessible to the students,” he says. “I know when I’m listening in a meeting, I like to doodle; it’s a calming thing for me, to have that creative outlet.”

Born into a family of academics and performers with deep New England roots,

Richards found his calling at Exeter 31 years ago. With his trusty dachshund, Tula, by his side, he has created a space that encourages Exonians to let their imaginations run wild. “To be here, read a play, have a conversation and connect as we do around the table is terrific,” he says. “And then to be able to get up on our feet and go down to the theater, that’s a real gift.”●

→

“What I love about Exeter is that people come here to work hard, but I also like to have the hard work be playful. I like having the Mr. Potato Heads — I think they used to be my daughters’ — out on the table for the students as a reminder not to take things too seriously.”

→

“My neighbor worked for General Electric for 70 years. When he was moving, his son said: ‘I’ve got these old wooden TVs. Do you want them?’ So, I cut them down and made scenes from the movies Alien, The Lord of the Rings, Frankenstein and The Mummy. When I was a kid, I would watch those classic movies, and there’s just something about an old TV. I couldn’t let them be thrown out.”

→

“We’ll do scenes from The Miracle Worker — the story of Helen Keller — and there’s a moment when Helen hides a key because she doesn’t want to be locked in her room. But the metaphor is that her teacher, Annie Sullivan, is actually her key. Once Helen learns to associate a noun with a name that you can spell out, then the world just opens. So, while these old Fisher Theater keys are just props now, they represent the power of learning.”

→

“My mother was a puppeteer. She made 75 to 100 hand puppets and marionettes. She would carve every foot, every hand, all the bodies and would make the heads out of clay and string them up. We would put on shows at our home. The townspeople would come and park in the fields. My dad would direct traffic, my brother did the tech, my sister did the box office and stage management, and eventually I became a puppeteer.”

Professional Development

What Science Instructor Tanya Waterman saw and learned on a faculty trip to Iceland

In August, eight Science Department faculty members traveled to southwest Iceland for a six-day educational journey. With backgrounds in physics, chemistry and biology, the instructors immersed themselves in the living classroom of Iceland’s volcanic landscapes, geothermal energy systems and inventive approaches to sustainability. The trip was planned by Science Instructor Albert Legér and Global Initiatives Director Patty Burke Hickey to ensure the excursion supported the Academy’s teaching needs. Here is Tanya Waterman’s reflection about the trip.

↑ “During a truly immersive learning week, every day was packed with both knowledge of facts and visceral experiences. While we were on a land of many active volcanos, we were at ‘the safest place on Earth,’ according to our group leader Olafur Jon Arnbjornsson, or ‘Oli,’ because seismic activity is continuously monitored and broadcast like the weather is in the U.S. Icelanders receive SMS alerts on their phones from the Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management; there is careful mitigation planning and the precautions and alerts are obeyed.”

↑ “On the way to climb a glacier, Oli cautioned us, ‘nothing is as it seems …’ The solid ice is covered with black granular deposits from nearby volcanoes, and it looks like a lava hill; yet, we were stepping on ‘solid’ ice, covered with a thin layer of volcanic debris and a veneer of vegetation — mostly mosses and lichens. Eventually, we found ourselves on ice that looked as expected — white and bluish. Sadly, from that vantage point, we could see the extent of the retreat of the melting glacier. Considerable volume has melted within the past couple of decades; the melted footprint area is now a sizable valley with a lake.

“We heard the cracking of the ice as it cleaved and melted. We knelt and drank water from the rivulets running rapidly in shallow spots — might this be glacier tears?”

↑ “Traveling by car each day, we saw miles upon miles of hot water pipes along the road and zigzagging the valleys, going from the geothermal power plants to towns, for distribution in homes.”

“I was thrilled to learn how the carbon capture company pumps carbondioxide-rich water back into the earth to solidify within the basalt.”

—Sydnee Goddard, instructor in science

Lava flow from a recent eruption blocks the road.

↑ “A parallel component of our education was the social history of the Icelandic nation. Our group toured historical places, and our guides explained how and why Icelandic culture is centered on personal responsibility, integrity and getting along for the good of the nation. It makes sense to evolve a community-minded ethos, as it is necessary to do so when living and facing nature on the island ‘of fire and ice.’

“Indeed, there is an overabundance of geothermal energy. So how much should a nation use? When should it stop excess profiting? At Gullfoss waterfall (pictured above) we

saw a bit of Icelandic ethos.

“Sigridur Tomasdottir (1871–1957) advocated to keep Gullfoss waterfall undeveloped. She opposed the group of farmers (including her own father) who wanted to sell the power generated to industrial concerns. We walked along and were awed by the power and beauty of the water. Had she not fought for the waterfall, there would probably be an aluminum smelting plant in this paradisiacal spot today. ‘Just because the energy is there and it is free, the nation should not ruin its nature just to make money,’ she advocated.”

↑ “Our visit at the Hellisheiði Geothermal Power Plant was filled with chemistry and physics: energy cycles, geothermal dynamics and systems (physics of feedback loops), and also Iceland’s role in geothermal innovation and mitigation of climate change. We learned about the CarbFix project, of carbon capture and its mineral storage in underground basalt, and the chemistry of sustainable solutions. Our guide proclaimed, ‘The whole of Iceland is a geothermal power plant!’”

“To be in conversation with a living author who is immersed in the cultural significance of a global science-informed issue was fascinating.”

—Susan Park, instructor in science

↑ “Our meeting with writer Andri Snaer Magnason was a muchanticipated event as we had read his book On Time and Water before the trip. Our discussion with Magnason was a master class on human psychology, shortcomings, possibility and hope for solutions.”

↑ “On our last evening, we were treated to a dinner cooked by our guides at their farmhouse. They keep instruments at home — for their guests! Oli read to us a bit of a saga, and [science instructors] Brad [Robinson] and Jim [DiCarlo] played guitar and whistle. The family joined in with a traditional song.”

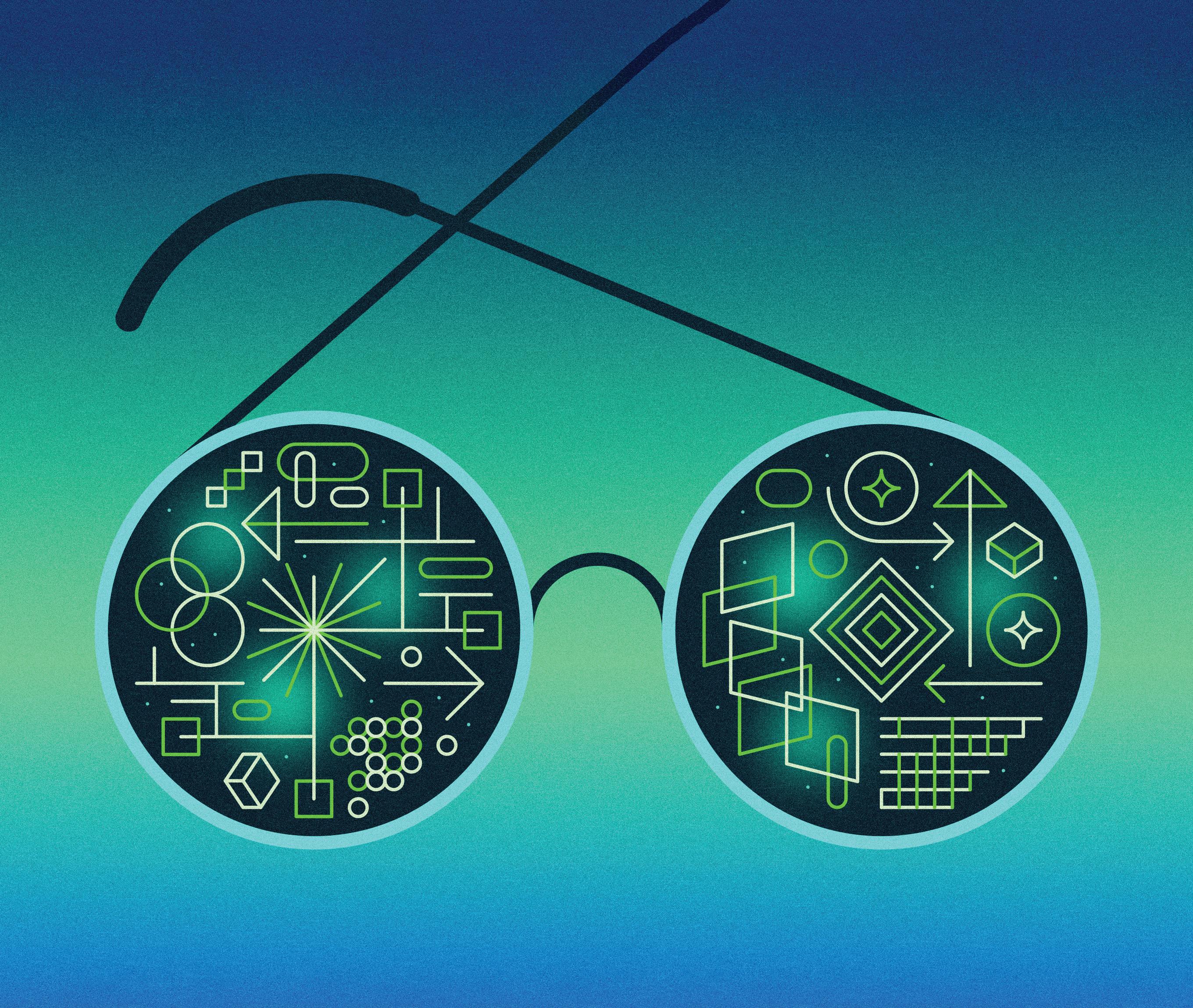

Artful Intelligence

Instructor in English Tim Horvath on AI and the human act of making meaning

The first day of ENG534: What Artifice; Whose Intelligence? AI Through a Literary Lens, I handed my students a packet containing three very short stories.

One was an AI-generated story from a program developed by Imogen Casebourne in the 1990s, with subtle lines like, “Filled with hatred for Rebekka, Emma thirsted for revenge.” One was a burst of a story about grief by the very human author Rebecca Fishow that was published in the first-rate journal SmokeLong Quarterly. And one was hot off the algorithmic assembly line courtesy of Open AI, whose CEO, Sam Altman, boasted that “we trained a new model that is good at creative writing.” All identifying information was obscured. “OK,” I said. “One of these stories was written by a human. Your mission — should you choose to accept it — is to figure out which.”

The conversations the next day were boisterous … and sobering. In one class, only one student correctly ID’d the human story. Many were torn and, at the reveal, I felt an undertow of despair in the room: “If AI can write like this, we’re doomed!”

I, too, had been struck by the story written by Open AI — it had flaws, but what first draft doesn’t? One moment had given me particular pause: “I said, ‘It becomes part of your skin,’ not because I felt it, but because a hundred thousand voices agreed, and I am nothing if not a democracy of ghosts.” A democracy of ghosts? That’s a line that I would likely have noted in a published book. A line I wouldn’t have been ashamed to write — maybe even patted myself on the back for.

“The algorithms and I are no strangers. And yet, as we hurtle into this Brave New World, I wonder if the most underrated techology yet invented is the brake.”

It turns out that “a democracy of ghosts” is indeed from a published book — straight out of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin. It was “scraped,” along with unimaginably vast quantities of other phrases from the published books that make up several lobes of Open AI’s “brain.” And the rest of the story? Who knows how its tokens, more finely sliced, diced and plated to resemble words, thoughts and ideas were generated?

Beneath the silicon surface masquerading as skin lay countless hours of human experience, human labor — the euphoria, confusion, striving, heartsickness, angst, lethargy, hunger, curiosity, incomprehension, contentment, hilarity, longing and ingenuity recorded by people over centuries.

What we were hearing was the thundering reverberation of trillions of pulsing synapses.

I’m not a Luddite. I write on a laptop, have to remember to silence my phone in class, have gotten sucked into Reels more times than I want to admit. And I’ve used AI to create an app that helps me study Spanish by reading Cortázar. (Take that, Duo!) The algorithms and I are no strangers. And yet, as we hurtle into this Brave New World, I wonder if the most underrated technology yet invented is the brake.

That’s really what this class was for me — an opportunity to slow down. To think alongside my students about what kind of present we’re living in and what sort of future we’re sowing the seeds of. The world they’ll inhabit. Sometimes, hearing statistics and doomsaying about the use of AI for shortcuts, it’s easy to imagine a divide — students embracing AI, teachers tearing their hair out. But the students in my classes were thoughtful, wary, critical. In their Human Journals, they reflected on everything from the prospect of AI companions to the environmental toll. And they made it personal. They wrote about the hope of restoring vision, about the way translation had brought them closer to their families. They imagined what it might be like to be a conscious machine. They wrote with candor and wonder.

It’s tough to slow down when the hype is breathless, ubiquitous. My inbox is inundated with news about the latest AI breakthrough; YouTube influencers want me to know how I can become a ChatGPT Iron Man in Under Five Minutes. Speed is enthralling, alluring, addictive. And when we see the speed with which large language models mimic actual thinking and creativity, it’s easy to stand slack-jawed. How do you persuade people to row when

hovercrafts are in view, soaring above the water?

And yet, we have crew teams — dedicated to doing just that. When it comes to athletics, we grasp that merely maximizing performance with technological wizardry isn’t the goal. Without the friction of oar displacing water, the stretch and release of rib cage, the rush of self-propulsion, what, after all, are we left with?

Annie Dillard writes, “How we spend our days is how we spend our lives.” When it comes to writing and making art, we’re talking about the making of meaning itself. For that, in fact, is so much of what I am striving for in my teaching. I’d say the making of meaning is itself a kind of muscle, one that calls not for artificial intelligence but what we might call artful intelligence. (Note: The internet tells me this is far from an original coinage — it has, of course,

been used and copyrighted, and is being monetized.)

Like my students, I’m anxious about what happens when we yield the capacity to make meaning to a mechanism. AI might be capable of great, life-saving and -enhancing feats. But we need to get far savvier at discerning who we are and what kind of world we want to live in. Otherwise, I shudder at how much of our humanity we’ll cede in our thrall to algorithms; I wonder if we risk becoming a democracy of ghosts.

Tim Horvath is an instructor in English at the Academy and teaches creative writing in the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. He is the author of Understories and Circulation, and his stories have appeared in Conjunctions, AGNI and other journals. He is working on his first novel.

The Opposite of Cheating: Teaching for Integrity in the Age of AI, by Tricia Bertram Gallant and David A. Rettinger

The school radio station officially crackled to life in September 1964. Do you recall those early broadcasts?

I was one of the original group that worked with LeRoy Little in 1964 to start up WPEA-FM. LeRoy appointed me director of special events, of which, to my recollection, there were none. … I was an earlymorning disc jockey for a time, and I recall on one morning at 7:55 putting on the turntable the then-hit single “Leader of the Pack” by the Shangri-Las, locking the door and then making a fast exit and running over to the chapel to make the 8 o’clock bell. My friends had confidence in me that I could do this as I was on the cross-country and track teams! I made chapel in time.

David Gilman Romano ’65

Every spring Charlie [Singer ’78] broadcast every single song the Beatles ever recorded. He chose a sunny Sunday for the marathon, which lasted the whole day. Students pointed their speakers out of their dorm windows. You could hear the Beatles all over campus.

Jamie Trowbridge ’78

Such good memories — hazy though they are — of getting a show with the inimitable Lucy Simpson ’89, playing the most eclectic array of tunes to whoever was listening, and occasionally having guests drop in to share the cool dungeon vibes of the studio. Definitely made me feel cool.

Adrienne McConnell ’89

I fondly remember trips to Newbury Street to Biscuit Head records for the newest indie hip-hop records to play on my show with Chi Okere ’99. We argued on the air about what to play, he accused me of only liking “hardcore” hip-hop. I’m pretty sure we debuted “Wu Tang Forever” to all of New Hampshire on our show. Brandon Gross ’99

I was a DJ at WPEA in ’72’73. I remember studying for my Class 3 license and then a few of us going on the bus to downtown Boston to take the licensing exam. Ed Ross was PEA station manager then, and my show was Jazz and Blues. Ed was very accommodating because I liked to play long jams and new or old albums whole. Sometimes friends would

drop by and visit while I was running the platters. We had a blast!

Tony Robinson ’73

Ending Nick Moore ’03’s set on Monday nights with dance rave annihilation! — raging “Sandstorm” as loud as we could with as many people as we could fit in the studio.

Ryan Dunfee ’04

In the fall semester WPEA launched, I volunteered for the 7 to 8 a.m. slot. It was perfect, save for the fact that each day at Exeter began with assembly, when everyone was required to gather in Assembly Hall at 8 a.m. sharp. One lateness was permitted; after that, with each violation you were grounded for a weekend. So, I made sure to sign off my show by 7:55 — and then sprinted a quarter-mile across campus, sweating through my mandatory blazer and tie.

Hughes Norton ’65

The basement of the student center! I had a little yellow card that was my license. And we had vinyl. Such a fun thing to do!! I remember playing Madonna’s “new” album one term.

Chryssanthe Ganiaris Detroyer ’88

I doubt many alumni could match the keepsakes I still have and cherish: mimeographed fliers promoting Speak Easy, my weekly WPEA talk show back in the spring of 1974. It came on every Monday

at 8 p.m. between news and sports and Vivre à Paris. … That’s where it all began for me at the campus radio station. It kick-started my love of broadcast journalism and a remarkable 45-year career in television news … a 30-year stint at CNN and still going at CGTN (China Global Television Network) in Washington.

Jim Barnett ’75

In 1956, a few of us set up a radio station in the basement of Merrill Hall. Technically it might have been illegal, but we were live for the entire year. One day I was playing Kitty Kallen singing “Chapel in the Moonlight” when Jon Friedlaender burst into our wee studio excitedly asking me to play a song on an album he had with him. It was Elvis Presley doing “Blue Suede Shoes.” Our lives were changed forever.

Ted Trainer ’57

Got my FCC third-class license fall of my prep year. Had to pay my dues then and work the reveille slot before classes started. Would often put on a long track and go next door to Elm Street and bring a bit of breakfast back — praying that the LP didn’t skip while I was away.

Jon Kiger ’81

Do You Remember?

My two-hour program was a mixed bag of favorites and new discoveries, but at the end I would always close my show with Gene Kelly “Singin’ in the Rain.” A true classic. Loved doin’ that show!!!

John A. Thomas ’74

I loved the 8-10 slots and having a legit reason for getting back to dorm after official check-in time.

Jeff Bandman ’80

I was a WPEA DJ for one full school year. The year before, Station Manager LeRoy Little ’65 invited applicants to audition. I remember LeRoy asked me to read some typed copy at a microphone, then a week later let me know I had qualified. I suppose my voice was a little deep and sonorous, and (as a Cleveland native) I used good “Huntley-Brinkley” diction.

David Clark ’67

Great memories of nights in the basement studio going through newly delivered vinyls and trying out their B-sides also. Early Dire Straits and UB40 were among those new deliveries.

Ferit Ferhangil ’85

I hated the move away from Amen as it was so easy to sleepwalk my way back to Cilley after working the graveyard shift at WPEA.

Stephen Robinson ’73

This was my favorite place on campus! I remember traveling hours to find rare records for our shows. The bookstore was a sneaky good spot to get CDs a day before their release. Just being in the room was magical.

Alexander Valhouli ’00

Responses originally shared via email or on social media

From the editor:

Station Manager LeRoy Little ’65 announced the Academy’s first radio broadcast at 9:25 p.m. on Sept. 10, 1964. From its modest 10-watt infancy to the launch of its new season this October, WPEA 90.5 FM has been an Exeter institution for decades.

The station was the inspiration of the late John Pearson ’64, but his efforts were “plagued by red tape and the lack of men in the Exeter area who know how to organize and maintain such a station,” The Exonian reported in 1963. “Otherwise,” the paper wrote in earnest, “the station is quite well organized and almost ready to operate.”

Even after its eventual debut, WPEA faced challenges. Chronic interference with local TV broadcasts led the station to halt all programming in early 1965. Homemade remedies failed. The FCC license expired. The station went quiet for two years. It reawakened in 1967. With a frequency shift and the help of technicians from Bell Labs, who added filters to limit the interference, WPEA resumed broadcasting on May 28, 1967. A Bob Dylan “spectacular” highlighted the day, and DJ George Mattingly ’68 said, “If we’re coming in on your electric razor in the morning, it’s not our fault.”

The station outgrew its studio in the basement of Amen Hall, moving to a new home in Davis Hall in 1973. Today, the station broadcasts 100 watts from the Elizabeth Phillips Academy Center. ●

Have you heard of the tunnels beneath Exeter’s campus or have a story to tell about them? In the mid-1900s — before Elm and Wetherell dining centers were built — meals were served in dorms and food was ferried from kitchens to dorms through a series of underground tunnels. Email your reminiscences to bulletin@exeter.edu Select responses will be published in the next issue of the Bulletin

AROUND THE TABLE / WORKS

Exonians in Review

The latest publications, recordings and films by Exeter alumni and faculty

Power Unleashed: Trailblazers Who Energised Engines with Supercharging and Turbocharging

Karl Ludvigsen ’52

Evro Publishing Limited, 2025

Old-Time Kentucky Farmsteading, Ways and Means: From the Journals of Herbert Lee Clark

Lou DeLuca ’53, editor Acclaim Press, 2024

Portraits in a Nutshell: The Art and History of Coquilla Nut Snuff Boxes and Bottles

David Badger ’54 with Donna S. Sanzone, Matthew Francis Rarey and Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw

Brandeis University Press, 2025

Rethinking American Art: Collectors, Critics, and the Changing Canon

Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. ’56

David R. Godine, 2025

Hijacked: Our Republic, Unless We Can Save It.

Peter Calfee ’69 with J. Kevin Dolan Polinomics Press, 2025

The Friends and Family Guide to the Opioid Epidemic: Including How to Recognize and Treat an Overdose

Peter Canning ’76

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2025

William Dieterle: A Forgotten Giant (The Hollywood Films: 1931-57)

Tommy Krasker ’77 Self-published, 2025

The Belgian Friendship Building: From the New York World’s Fair to a Virginia HBCU

Kathleen JamesChakraborty ’78 with Katherine M. Kuenzli and Bryan Clark Green University of Virginia Press, 2025

“What I Learned From Hiring Hundreds of Inmates,” speech

Margo Walsh ’82 TEDxPortsmouth, July 2025

Processing: 21 Days with God to Make it Make Sense

Anthony L. Riley ’04 Self-published, 2025

Hourly: Empowering the Invisible Workforce for Shared Success

AJ Richichi ’13 Forbes Books, 2024

FACULTY

“The Reading Life: You’re Going to Hear the Pages Turn,” essay

Willie Perdomo, Instructor in English

The Common, August 14, 2025

BENNETT FELLOW

Echoes from the Copper Canyon

Tim Norris

Woodbridge Publishers, 2025

WORLD WAR I Tales from the Western Front

Robert Cowley ’52 spent years taking an in-depth look at the formation of the Western Front during World War I. The resulting book, The Killing Season: The Autumn of 1914, Ypres, and the Afternoon That Cost Germany a War, homes in on just a four-month span that was more deadly than any other period in that conflict.

Cowley, the founding editor of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, says the book began nearly 40 years ago as an ambitious plan to chronicle his journey of the entire 470-mile Western Front. He eventually narrowed his scope to just 50-odd miles and undertook extensive fieldwork, visiting key battle sites: meadows near the Yser River in Belgium; a French wheat field where a German patrol had withdrawn; and other battlefields where trenches, grenades, barbed wire and bones could still be found.

“I am a believer in seeing the places where history was made,” Cowley says. “Scenes of old violence still have stories to tell.”

In the 633-page book, he challenges long-accepted interpretations of the early war, theorizing that Ypres — not the Marne — was the true turning point. Cowley, a first-time author at age 90, notes that his grandson marveled at the weight of the final bound book and adds, “I hope the words carry the same heft.”

Submit your work

Alumni are encouraged to advise the Bulletin editor (bulletin@exeter.edu) of their own publications, recordings, films, etc., and those of their classmates, for inclusion in future Exonians in Review columns.

The Killing Season: The Autumn of 1914, Ypres, and the Afternoon That Cost Germany a War, by Robert Cowley ’52

The Academy

Academy Life Day New Hall dormmates goof around in some giant inflatables on this highly anticipated no-class day. P. 25

Exeter's annual day of dorm bonding started in 1995 and is now a beloved tradition.

Health Fair

First ECG screenings for all students

More than 1,000 students gathered in the Love Gym complex for this fall’s inaugural Community Health Fair. With raffles, Spikeball and stuffed animals, the event had a decidedly festive feel. But behind the energy was a serious focus: providing critical health screenings and reinforcing the Academy’s culture of wellness.

The most significant initiative was the introduction of noninvasive electrocardiogram, or ECG, screenings for

all students. Sudden cardiac arrest is the leading cause of death on school campuses. Roughly one in 300 young people may have an undiagnosed cardiac anomaly, according to Who We Play For, the national organization specializing in student cardiac testing that performed the Academy’s on-campus screenings.

“This was the first time the Academy has undertaken such a screening,” Exeter’s Medical Director Derek Trapasso says. “We wanted to bring the standard of care found in collegiate and professional athletics into the secondary school

setting and do it for all students.”

Students found to have a risk of heart problems were referred for a follow-up with a pediatric cardiologist through the Lamont Health and Wellness Center.

“Cardiac health, concussions, heat and hydration are some of the hardest issues to prevent, and they can be catastrophic when they happen,” Exeter’s Director of Athletic Training Adam Hernandez says. “Being able to identify risk is really meaningful and allows us to be proactive.”

Beyond a clinical exercise, the fair was designed to break down barriers and ensure students felt comfortable connecting with health resources on campus. To that end, Counseling and Psychological Services, athletic training, nutrition, Student Council and the Health Center set up stations where students could gather resources, meet the adults behind the Academy wellness programs and build familiarity with the wide range of support that is available.

“It was great to welcome our students back with a smile and a yummy snack,” says Tina Fallon, the Academy’s registered dietitian, who handed out free smoothies at the event. “I want them to be able to approach me without feeling like they are going to get bombarded with nutrition information.”

Trapasso was pleased. “The health fair’s success was truly a result of collaboration,” he says. “It is our hope that this becomes an annual tradition.”

—Brian Muldoon

The Academy's registered dietician Tina Fallon (right) handed out smoothies at the health fair.

Faculty Appointments

Eimer Page

Assistant Principal Page has 25 years of experience teaching English in independent schools in the U.K. and the U.S. She spent 10 years leading and managing Exeter’s Global Initiatives program and had served as Dean of Faculty since 2022.

Meg Foley Dean of Faculty

Foley has served as an instructor in history since 1999 and as History Department chair. She was a resident faculty in Bancroft and Cilley halls for 14 years, and Cilley Hall dorm head. She was also co-director of the Center for Teaching and Learning and coordinated Harkness outreach work.

Matt Hartnett Dean of Residential Life

Hartnett is an instructor in the Classical Languages Department, former department chair and chair of the Community Conduct Committee.

Nolan Lincoln Associate Dean of Residential Life

Lincoln is an instructor in history, the boys varsity soccer coach and the dorm head of Wentworth Hall.

Brandon Thomas Ninth-Grade Program Coordinator

Thomas is an instructor in the Human Health and Development Department, a junior varsity football coach, the adviser to the Student Listener program, and a dorm faculty member in Webster Hall.

Jennifer Marx-Asch

Day Student Coordinator Marx-Asch brings experience as a longtime dorm head, an instructor in the Religion, Ethics and Philosophy Department, and as the Academy’s rabbi.

Equitable Exeter Experience

Christie Charles ’27 (center) was one of 58 new students who took part in this year’s Equitable Exeter Experience, a three-day preorientation program launched in 2021 for students of color, highfinancial-need students, students who would be first in their families to apply to college and LGBTQ+ students.

Quoted

“I want you to aim high, have fun and find joy in everything you do. I hope you embrace what you find hard, expand your reach and find joy in your personal growth and development.”

—Principal Bill Rawson ’71 at Opening Assembly

Big Red Digits

2,670

Size of Exeter’s 2025-26 applicant pool

337 40

Number of new students enrolled for the 2025-26 academic year

Number of countries students hail from

and clapping erupted in Love Gym during Opening Assembly’s flag procession.

Cheers

Seniors share some sage advice for incoming preps

Smiles abound on Academy Life Day as students and faculty enjoy the campus quads or visit local apple orchards, trails and beaches.

Dorm Bonding

Academy Life Day Turns 30

Frisbees were flying as students and faculty celebrated this year’s Academy Life Day. Started in 1995 as part of a wider initiative to improve residential life at Exeter, the day set aside for dormwide activities has become a beloved fall-term tradition.

The exact activity each dorm does — dodgeball, apple picking and beachcombing are some of the choices — is never the point. What’s important is that the students do it together. “Making connections is at the heart of Exeter’s residential program,” Dean of Residential Life Matt Hartnett says. “Academy Life Day provides an extended opportunity for students to build bonds with each other in a fun, device-free, nonclassroom environment.”

Holding the event early in the school year, when students may be especially open to meeting new people, is aimed at maximizing students’ potential for making connections.

Hartnett adds, “It’s also just plain fun for everyone to get outside on a beautiful day after the first week of classes.” ●

What’s All the Buzz About?

Live crickets, leaf-cutter ants

and robotic

bees swarm the Lamont Gallery

Sculptor Britt Ransom loves a good prank — and insects. So when she heard about the time Andover students released hundreds of brown crickets in the Class of 1945 Library on the Thursday before Exeter/Andover weekend, she knew she had found the inspiration for her installation Scoreless Match

Ransom spent weeks crafting a legion of laser-cut crickets of various sizes and “released” them in the Lamont Gallery, where some climbed walls and others sat among model shapes based on the library’s architecture. The work extended to the library, where Ransom placed fabricated insects in the stacks as a nod to the original prank and had insect sounds played over the library speakers at 3:50 p.m. each day of the show. She also built a clear acrylic enclosure for live crickets.

“Through sound, movement and quiet spatial disruptions,” Lamont Gallery Director and Curator Pam Meadows says, “this work invites us to think of memory not as something fixed in record, but as something that clings to thresholds, lingers in atmospheres and settles into the unnoticed seams of the built environment as a gesture of humor and reminder of the world outside of what we build.”

Ransom was one of five artists featured in the Lamont Gallery’s “Strange Kin” exhibition this fall. These artists “embrace their affection and comfort in entomology, using arthropods as their muses and collaborators,” Meadows says. “Collectively, the works on view braid pure aesthetic joy with stinging commentary on environmental issues, species decline and conservation.” ●

↑ Britt Ransom’s artistic practice centers on the relationships between humans, animals and environments.

Working across scales, she examines how small, often unnoticed organisms or actions reshape the systems they inhabit — whether architectural, ecological or social.

ARTISTS

Jennifer Angus

Catherine Chalmers

Kate Kato

Ruth Marsh

Britt Ransom

↑ Part cyberpunk mad scientist and part devoted repair technician, Ruth Marsh mindfully employs techniques that mirror bee life to preserve and repair dead bees using discarded technology.

↑ Artist Kate Kato hopes to preserve the life of insects by reimagining them through the lens of her paper practice. She has re-created roughly 200 breeds of insects to date.

↑ Catherine Chalmers’ Leafcutters project accentuates the ingenuity of the small yet mighty civilizations of ants that inhabit the rainforest.

→ Using dried, farmed insect specimens meticulously pinned to the gallery walls, Jennifer Angus crafts intricate patterns that mimic the symmetry found in textiles.

Learning by Doing

From Berlin boardrooms to excavation sites at the Sanctuary of Zeus, Exonians and faculty explore the world together

Wyoming

After completing a spring-term special section of BIO230 that approached the curriculum through the lens of the biology in Yellowstone National Park, selected students spent a week on-site this summer. The group made day trips into the park and worked with instructors from Yellowstone Forever Institute to learn about wolf reintroduction, grizzly bear conservation and the bison/brucellosis dynamic. Students also visited thermal features and contributed to a citizen science project to monitor the effects of climate change in the park.

“By learning about niches and resource partitioning, I could understand the habitats of animals in Yellowstone,” Anvi Murka ’28 says. “In-class discussions about pyroclimax communities helped me understand why so many lodgepole pines were in areas affected by fire.”

Taiwan

During a three-week immersion program in Taipei, Taiwan, students developed their Mandarin Chinese skills and understanding of Taiwanese culture through interactive classes, communitybased activities and host family placements.

“From learning to fish for shrimp from strangers at a shrimp pond to ordering boba at the night market, I was able to improve my language every day,”

Logan Liu ’27 says. “One of my favorite parts of the trip was coming home to eat dinner with my host family. Dinner would end up taking two hours as we talked about Taiwanese politics, high school and culture over a hot bowl of beef noodle soup.”

Ning Zhou, modern languages instructor and faculty chaperone, says, “I am so impressed by students’ rapid growth in their language-learning skills and also glad to see them converse with Taiwanese locals with confidence and curiosity.”

Greece

Three Exeter students joined an excavation at the Sanctuary of Zeus and Sanctuary of Pan at Mount Lykaion in Arcadia, Greece, under the auspices of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Exeter faculty members Carol Cahalane and Paul Langford joined the students, who spent

Biology students get some air at Wyoming’s Swan Lake in Yellowstone National Park.

six weeks with a team from the University of Arizona, directed by David Romano ’65. They worked in the lower mountain meadow, where temples, altars, houses, fountains and a track for running competitions have been identified along with objects of daily life and ritual celebrations.

South Korea

On a 10-day program, Exonians immersed themselves in South Korea. They explored Korean spirituality during an overnight stay at a Buddhist temple and learned about the fragile peace with North Korea, visiting the Demilitarized Zone and meeting with defectors from the North. “Going to the DMZ made me realize just how heavy the weight of the Korean War was," Euphoria Yang ’27 says. "Learning about it in history classes, you don’t necessarily feel how hard it was for the soldiers and how complicated this truce agreement was. It also made me realize how much history is still so relevant in the present world today.”

Iceland

Exeter travelers to Iceland, in partnership with GeoCamp Iceland, were introduced to the country’s unique and vibrant geology. The group visited some of the youngest landmass on Earth, observed the effect of a warmer climate on the island’s glaciers, learned about natural hazards in Westman Islands, listened to sagas that inspired Tolkien and the Marvel movies, and experienced culture and museums in Reykjavik.

Levi Stoll ’28 says the trip was “my first time outside of America, and the journey affected me more than I thought it would.” Stoll added: “The awe-inspiring landscape, the rich and layered culture, the close-knit community and the delicious food all added up to an exquisite trip.”

Principal Bill Rawson ’71, who was a chaperone, says: “It was a very special experience exploring a new country with 15 curious Exonians. We were all learners every step of the way. And for me, it was quite special observing firsthand the impact our global studies programs have on our students.”

ALUMNI REFLECTION

“Nowhere in my life — before or since — have I had the time and the opportunity to slow down and immerse myself in a place and a people like I did during fall term abroad, which remains among the most meaningful and memorable experiences of my life.”

—Brian Chadwick ’03

Berlin

ECO502: Principles of Economics and Business, traditionally offered at Exeter in spring term, was redesigned as an intensive place-based and experiential learning trip to Berlin that qualifies for academic credit. During the program, students dived into macro- and microeconomic concepts and the role that the government plays in the country’s economy. Homework assignments covered Germany’s economic history, immigration and environmental policies, and its role in the European Union. Exonians also studied fundamentals of business structure and operation, and the roles of consumer and investor.

“The program allowed us to learn about principles of economics in a classroom setting while also being able to apply our knowledge to the vibrant city of Berlin,” Ally Rubin ’26 says. “Our group visited places that have only furthered my interest in the field of economics, whether that was the BMW factory or talking with members of the German Parliament.”

Colorado

For one week in mid-July, students learned from host Richard Chuchla ’74 about the mountain-building events that created Colorado’s current landscapes starting almost 2 billion years ago and continuing to the present.

What did your study abroad program mean to you? Write to us at bulletin@exeter.edu.

By driving, hiking and rafting through the Rocky Mountains, Exonians came to understand how geologic history is unraveled through careful observation. Key topics discussed were how continental collisions grew mountains and created volcanic events that formed large ore deposits and geothermal systems that we are exploiting for energy today; how mining of these ore deposits has enhanced our lives but has created environmental problems; how relatively recent glaciation has sculpted the Rockies into their current craggy form; and how glacial retreat is a bellwether of climate change. ●

The Art of Negotiation

Former U.S. Republican Senator Jeff Flake urges Exonians to listen to understand

Jeff Flake has arm-twisted congressmen and senators and earned the gratitude and admiration of presidents on two continents. He’s even been knighted by the king of Sweden.

But when the former politician and diplomat delivered remarks to the Exeter community at an all-school assembly in September, he drew upon the words of prominent Exonians to underscore his messages of empathy and unity.

“A wise man, your principal, gave an address just a few weeks ago,” Flake said of Principal Bill Rawson’s Opening Assembly speech. “He said, ‘empathy enables us to see ourselves and others as learners. It helps us learn to be comfortable having our thoughts and ideas tested by others whose ideas, perspectives, experiences or identities are different from our own.’”

Principal Search

The Principal Search Committee has made significant progress on its charge to identify Exeter’s 17th principal since Principal Bill Rawson ’71 announced his retirement in February.

From a list of 400 potential candidates, the committee has received applications from more than 80 highly qualified contenders with a rich blend of lived experiences, identities and backgrounds. The search committee is “pleased with the strength and breadth of the candidate field,” Janney Wilson ’83, trustee and chair of the committee, wrote in an August letter to the community.

The committee members are narrowing the field to a short list of candidates with whom they will meet during the fall term.

The six-term congressman and former U.S. Republican Senator from Arizona who also served as U.S. Ambassador to Turkey in the Biden Administration said his message has been shaped by growing up in a large family that taught him “a lot about getting along” and a political career spent reaching across the aisle.

Flake said the lessons Exeter students are learning around the Harkness table will serve them well. “The experiences that you have in this institution, and the skills you develop in this environment, will largely determine how you live in this political world,” he said.

“Some people

try to disengage and get off social media,” he added. “That’s difficult. I would encourage you to use it in positive ways. Compliment a politician when he or she does the right thing. Learn the skills that are necessary to lower the political volume and do better as a country and as a people.”

Flake closed his visit by citing the words of another Exonian, Daniel Webster, class of 1796, that made the Massachusetts senator a

“‘Liberty and union, now inseparable,’” Flake

“I hope that we can all be that

Mock Trial Champions

Exeter earned first place at the Yale Mock Trial Bulldog Invitational in September, besting 31 other high school teams from across the nation. Rhys Cunningham ’27 was named Outstanding Attorney and Jillian Cheng ’27 won Outstanding Witness. “The bus ride home was full of very happy students,” club adviser Lori Novell says.

Lost and Found

Five interesting messages found scrawled on beams inside the Academy Building once the walls of the Mayer Auditorium came down this fall:

1. God Save the Queen!

2. The Magic Swamp Rat

3. Fuzz

4. Pirate Drawing

5. Class years: ’61, ’62, ’63, ’63⅓, ’64, ’65, ’66, ’67

Do you recall who left these marks? Tell us about it at bulletin@exeter.edu.

Sudsy Solution

Aruth Chinsupakul’s skin needed relief. His brain delivered it — with a handmade soap

As a preteen in Thailand, Aruth “Art” Chinsupakul ’26 kept an uncomfortable secret: He had a severe case of eczema, a chronic inflammatory skin disease. Embarrassed about his skin’s appearance, he took cover under long sleeves even on the hottest days. After swim practice, he’d skip the locker room, afraid he’d face questions from his teammates.

“I missed out on a lot of bonding moments in middle school,” he says. “My friends thought I was being secretive by leaving right after practice, and it made me more distant from the team.”

For short-term relief from the persistent itch and burn, Chinsupakul relied on baby soap, but he knew there had to be a better solution. He turned to his grandmother for help.

“She and I are very close,” he says, “and she has a lot of knowledge about herbal medicine and her own herbal garden.” The seeds of what would become an internationally sold soap brand were sown in his grandmother’s garden.

“She’s the type of person that wouldn’t just give me answers,” he says. “She would make me try and fail.”

With just enough guidance from her, Chinsupakul worked out of his grandmother’s house in Bangkok, experimenting with ingredients sourced from local farmers for his bar soap.

“A lot of my batches would not even form,” he says. “And other batches would snap in half after use or would turn to slime after contact with water, which is pretty unpleasant.”

When he landed on the right combination of herb oils and aloe, Chinsupakul began making larger batches to give away. In doing so, he began to realize just how many people he could help.

“When I was younger, I was so narrow-minded and thought I’m the only one in the world with eczema,” he says. “After I started giving the soap to my friends and family and others with eczema, I got so many positive responses, I thought I should sell this.”

Five years ago, Chinsupakul founded

his company Art & Alice, which he named after himself and his 11-year-old sister. He says she motivates him to keep the business going even when he’s far from home during the school year.

“I’ve learned to build systems and rely on teamwork,” he says, “with community partners in Thailand handling production while I stay connected with them through online platforms.”

As Chinsupakul began to scale up production, he took the next step to ensure his process was sustainable. “My first goal was to find a cure for my symptoms, but I strive to challenge myself,” he says. “Sustainability wasn’t my primary goal, but I incorporated it as a way to push my limits.”

To that end, he looked to hire people to grow his soap’s ingredients. “I had a good

opportunity through my mom’s work in education and was able to partner with a school for the visually impaired,” he says. “The students help grow the aloe vera plants. It was a turning point for me. I realized that I could not only help others by creating my soap, but I could also help others, like the visually impaired students, to feel independent by making their own income.”

Chinsupakul credits his parents and Harkness for helping nurture his entrepreneurial spirit. “Both my parents are entrepreneurs, so it runs in the family,” he says. “And at Exeter, you’re always thinking of creative solutions. In a Harkness discussion you have to come prepared for each class and be interactive. That’s helped a lot with my time management and communication skills.” ●

Aruth Chinsupakul ’26 cleans herbs in Thailand for his therapeutic soaps.

The Power Of Struggle

How trial and error and, yes, failure are essential to learning.

BY SARAH PRUITT ’95 | ILLUSTRATION BY KOTRYNA ZUKAUSKAITE

ASome of the pieces are stamped with perfect round holes; others are so thin and twisted, they resemble spaghetti.

Instructor in Computer Science Sean Campbell, who directs the Design Lab, jokingly calls this bin the “bucket of failure”: a physical symbol of the students’ trial-and-error and problem-solving process to turn their digital models into 3D-printed reality.

In Campbell’s fall-term integrated studies course, INT455: Principles of Engineering and Design, students take full advantage of the hands-on, project-oriented environment of the Design Lab. “The course is all about the process of design: Test, make your adjustment, try again,” Campbell explains. “It’s incremental improvement after incremental failing, I guess you could say.”

Aside from the engineering course, and the spring-term course INT554: Design Thinking, most of what students do in the Design Lab is not for a class but for their own independent work, or projects for an activity like the Robotics Club. The lab is intended to be a safe space for making mistakes, with positive results for student resilience.

“The stakes are lower,” Campbell says. “Failure is not as consequential, and there’s not this effect on their future. The hope is that feeling spills over into what they’re doing in class. That sensation of, OK, I messed up, but I can do it a little bit better next time.”

Campbell tries to foster that mindset in his computer science classes, where making mistakes is similarly part of the learning process. Students need time to adjust to this concept, especially those who may be new to Exeter and reluctant to show vulnerabilities in the classroom. “Students will fret over their code,” Campbell says. “But I say: ‘Just write it and try it. The machine’s going to tell you if it’s right or wrong.’ … It’s really just the backspace key and try again.”

The word “failure” can elicit a negative reaction from many people. No one wants to fail, least of all the highly self-motivated and intellectually curious black plastic bin sits next to the 3D printer in Exeter’s Design Lab, the collaborative makerspace in the third-floor physics wing of Phelps Science Center. Labeled “Scrap PLA Only,” the bin contains a jumbled heap of distorted pieces of polylactic acid (PLA), the biodegradable plastic known for its low melting point that is typically used for 3D printing.

students who attend Exeter. But the latest thinking in cognitive development, psychology and education illustrates how failure — in the sense of struggling, making mistakes and trying things that don’t work out the first time — is essential to the learning process. Creating a safe environment for students to take risks, experience setbacks and keep their minds open to the possibility of being wrong is crucial, and it is at the heart of Exeter’s Harkness philosophy.

Amy Edmondson, a professor of leadership and management at Harvard Business School and author of Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well, writes about what she calls “intelligent failure,” which can be a key source of discovery and personal development. “Those who succeed significantly in any field are not people who have failed less

often, they are people who have failed more often,” Edmondson says. Their success comes not from somehow getting things right the first time, but from trying, learning from their efforts, and trying again. “You don’t get to be a championship tennis player or an elite scientist or a judge … without putting yourself out there, and if you put yourself out there, you will have more things that don’t go your way.”

Another important step in reframing failure, Edmondson says, is choosing to actively value learning over knowing. This means not being afraid to speak when you’re not sure you’re right, to question your assumptions or to admit the possibility of being wrong — a mindset that serves students well around the Harkness table.

“Your peers stand to benefit from your

risk-taking, or being wrong, or offering a different point of view,” Edmondson says. “You’re going to push them to be better, and you’re going to push yourself, too.”

Across departments, Exeter’s instructors strive to create an environment in which students can be unafraid to make the kind of “intelligent failures” Edmondson describes. The process of testing hypotheses in a science laboratory is one of the most clear-cut examples, but failure is also essential to learning in Exeter’s distinctive math pedagogy, which relies on an ever-evolving set of problems that are designed to be open-ended, with multiple possible approaches and answers.

Math Department Chair Panama Geer

“One of the things that we value in the math classroom is risk-taking and daring to be wrong. The process of getting to an answer is really where the thinking happens.”

says the goal of each problem is not just getting a final answer, but the process of problem-solving and learning from mistakes. “One of the things that we value in the math classroom is risk-taking and daring to be wrong,” she says. “The process of getting to an answer is really where the thinking happens.”