In a world of increasingly polarised views, fuelled by echo-chamber social media platforms, are we losingthe art ofa gooddebate? Not at SciencEd!From deep sea mining (p9)to robot apocalypse (p16),thereshouldbe somethingfor everyone to disagreewithinhere.

Elsewhere, we uncover the story of Eunice Foote, the female scientist who was erased from climate science history, despite being the first person to observe the heatingeffectsofcarbondioxide(p26).Wealsotakehealthrealitycheckson outdoor swimming (p22)and alcohol (p32).

As for the pig related puns, trot on to p18, where we reflect on the story of the world’s first xenotransplantation

Harry Carstairs EditorinChief2021/2022

Harry Carstairs EditorinChief2021/2022

Inside this issue: heated discussion; heated gases; and pig-puns galore

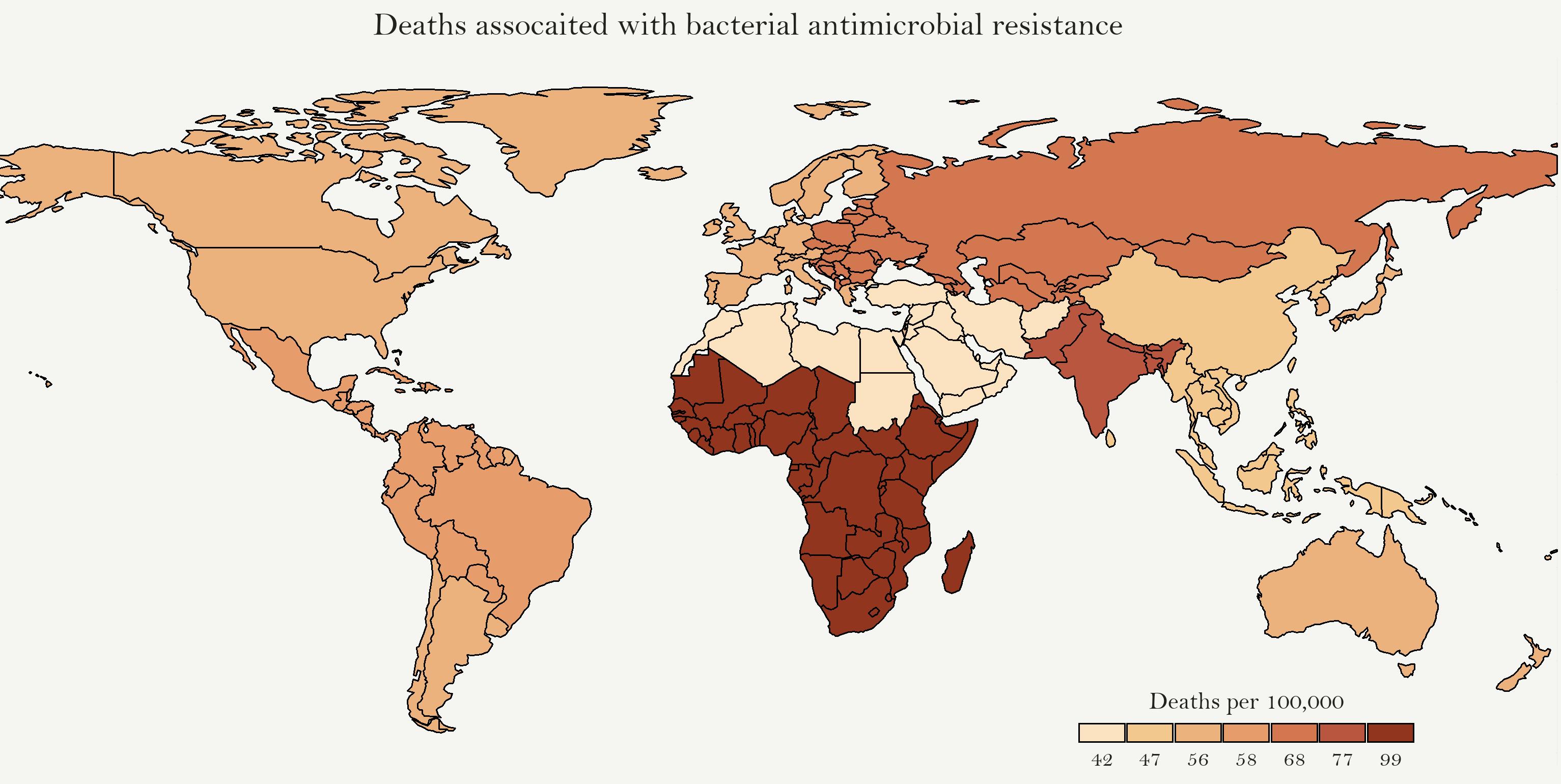

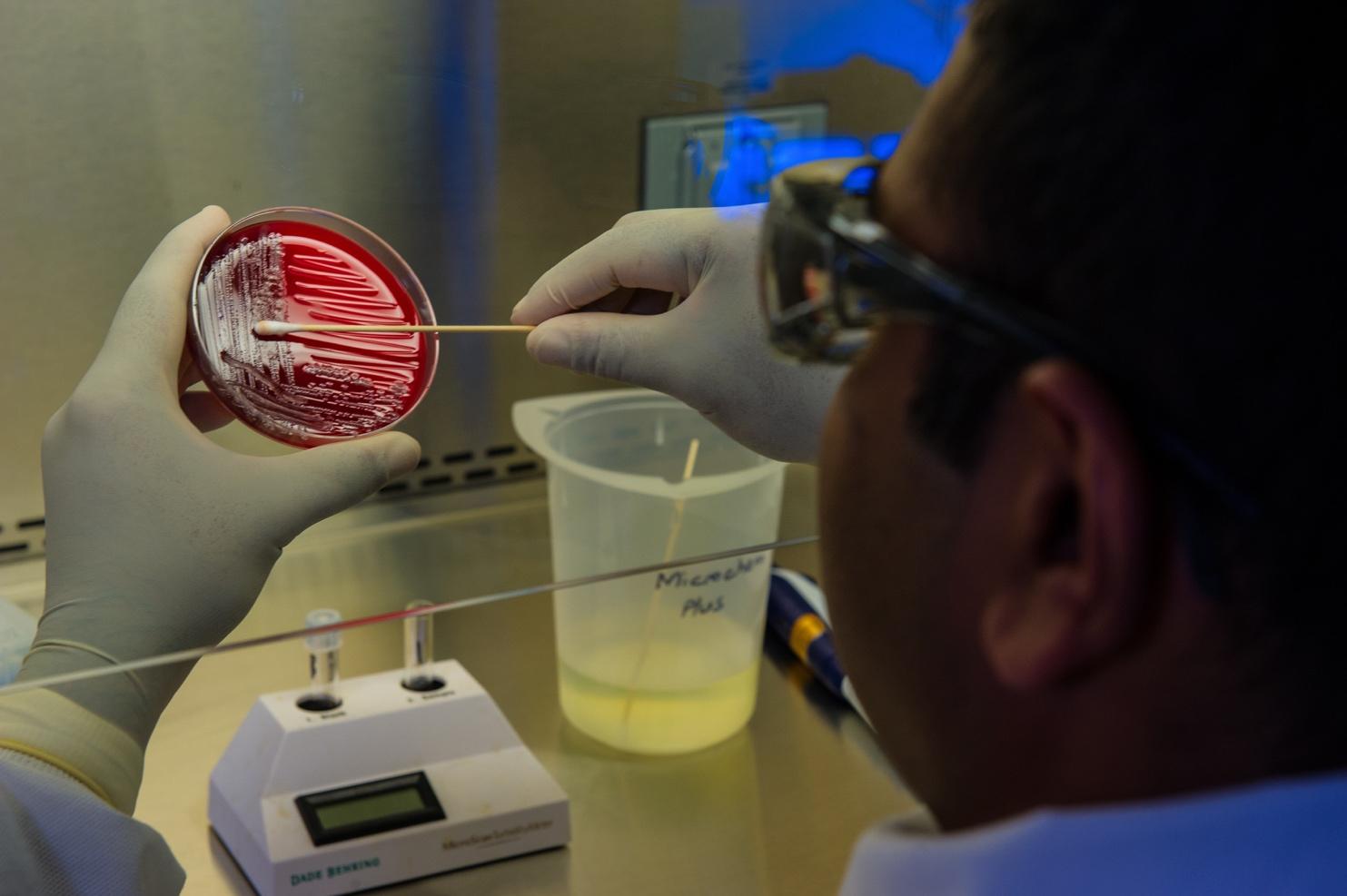

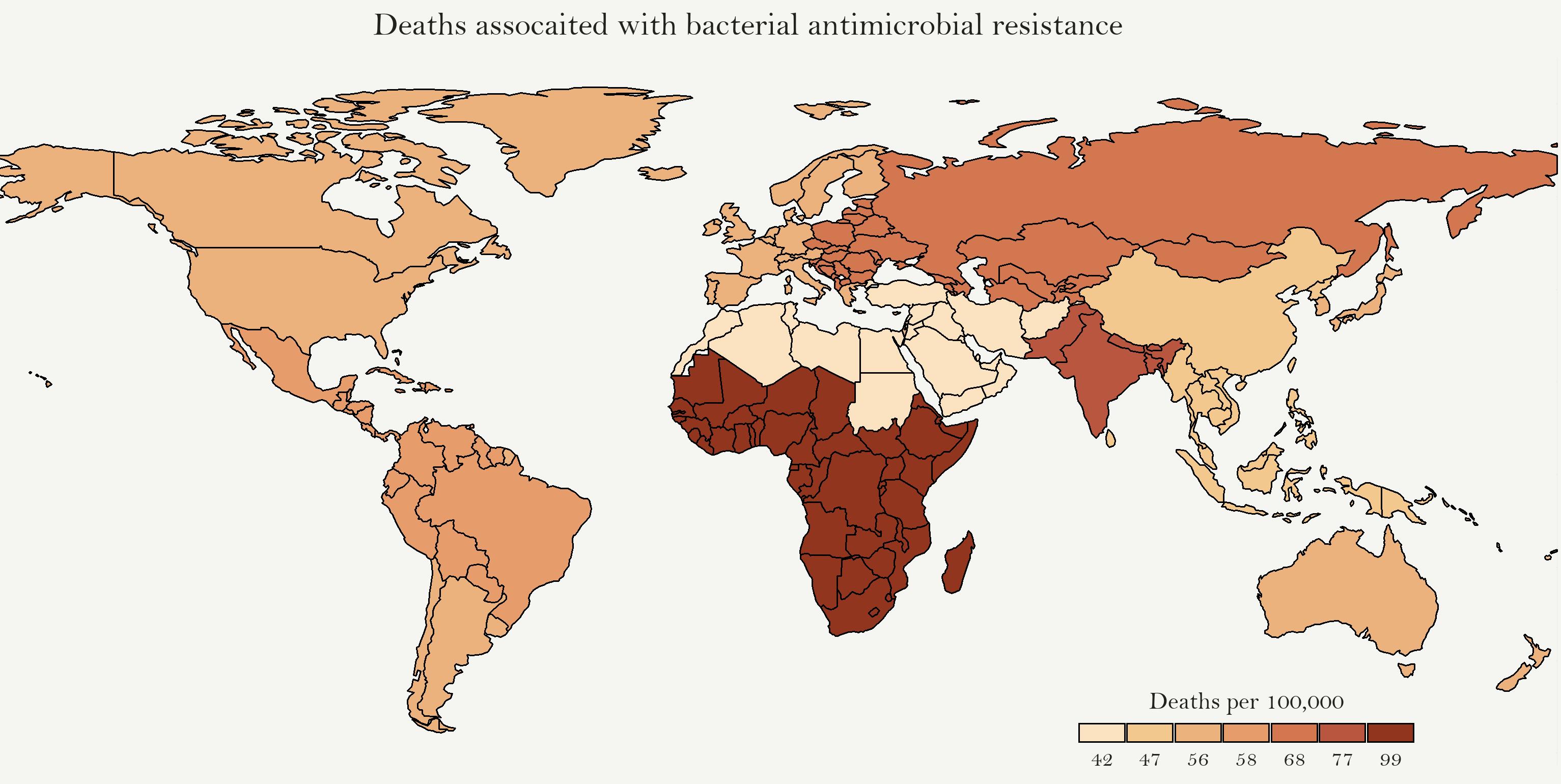

04 Snippets from around the world of science the great debates 09 Where science intersects with politics and morality features 18 Medicine – the man with a pig’s heart 22 Sport – is outdoor swimming good for you? 26 Climate – The woman who predicted global heating 28 Physics – from falling apples to relativity and beyond 30 Marine biology – looking back at COVID’s legacy 32 Health – time to go teetotal? research 34 Antimicrobial resistance – scale of global burden revealed 36 Human Genetics – preventing the next thalidomide disaster 37 Memory formation – a new link between brain and breath 38 Palaeontology – into the jaws of the T-Rex 39 Neuroscience – how your brain tells you when to stop eating 40 Conservation – is the grass greener on the other tide? tangents 38 Puzzles and games

to listen? Check out audio versions on the EUSci Readouts Podcast

eucireka!

Prefer

Cover illustration by Yen Peng (Apple) Chew

Illustration by Isha Prabhu

Holiday snaps help scientists

Your holiday photos may be more useful than you think! Aninnovativenewfieldistakingcitizensciencetothenext levelbymakinguseoftouristphotos.

Imageomics, as it’s called, uses artificial intelligence (AI)toanalysewildlifephotosandgaininformationonthe animals. Scientists can identify individuals, track their location and interactions with other species. This is used tomonitorendangeredspeciesandstudyevolution.

TheWildbookprojectusesthistoanalysephotosfrom public social media posts and global scientists for 53 species.It’sahugeamountofdata.“Thisisnowoneofthe primary sources of information scientists have on killer whales,” says Tanya Berger-Wolf of Ohio State University.Andtheuniversity’snewImageomicsInstitute willimproveonAImethodstogainmoreinsight.Itpicks up things that humans can’t, like differences in stripes between zebras and whether they inherit that from their parents.

Madison MacLeay

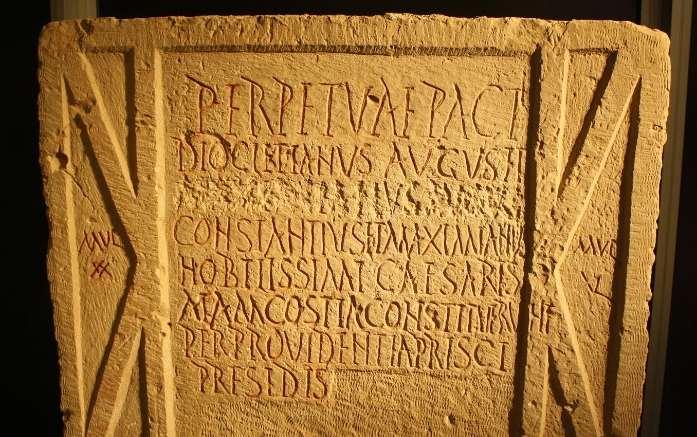

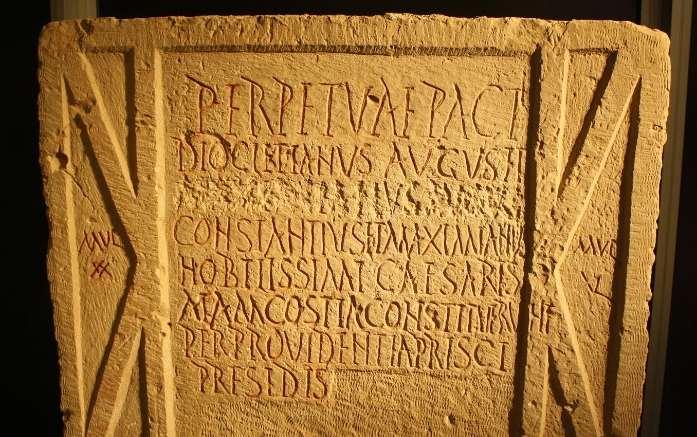

AI helps historians decipher ancient writings

A new artificial intelligence (AI) program helps historians restore ancient texts and estimate their chronologicalandgeographicalorigin.

DeepMind developers in cooperation with the Universities of Venice and Oxford, and the Athens University of Economics and Business, built Ithaca, an AI-powered solution that can fill in gaps in damagedAncientGreekinscriptions.

Studying the past relies on evidence, often fragmentaryordisplaced,asparticularlyexemplified in epigraphy – the study of inscribed texts found on durablematerialslikestoneandmetal.

Drawingonhumanfed-knowledge,Ithacadetects connections between letters and words to suggest completionsolutionsanddeterminewhereandwhen textswerecreated,augmentingandacceleratingthe workofepigraphers.

The software is available online for free. Still, users must remember that Ithaca is not meant to replacehumaneffort.Alone,itcanachieveonlya62% accuracyintextualrestoration.

AlkistiKallinikou

euscireka! 4 Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk

T(riple) – rex?

What if Tyrannosaurus rex is actually 3 distinct “sibling species”? A recent, if controversial study lead by Gregory Paul hypothesised that the variations we see in T. rex skeletons discovered acrossthelandmass ofNorth Americaconstitute T. rex , T.regina,and T.imperator speciesthatlookalike butdonotinterbreed.

Tyrannosaurus skeletons have been discovered from Mexico to Canada over a variety of climates, which makes it possible that specialised sub-species evolvedintonichesovertime.Theinterpretationof theskeletaldifferences has been previously thought to be due to the age and lifestyle of these distinct dinosaurs. Critics highlight that the study uses public and private fossil collections as part of its conclusions,whichmakesthedatahardertoverify.

The authors of this study nevertheless hold up theirworkassignifyingthestartofare-examination

Christian Donohue

Coffee climate trouble ahead

Climatechangewillsignificantlyaffectwhereintheworld crops such as coffee can be grown, according to a recent study.

Notonlyiscoffeesomethingwe’velearnttodependon in the west, it also forms the livelihoods of many smallholderfarmersaroundtheglobe.

ScientistsinZurich,ledbyDrRomanGrüter,haveused computationalmodelstopredictfutureclimateimpactson coffee, avocado, and cashew production. They found that coffeewouldbetheworstaffectedby climatechangewith thebestcoffeegrowingareasdecreasing50%by2050.

Cashew and avocado production, meanwhile, might actuallyseesomeimprovement.However,thiswillrelyon farmers globally adapting with the information provided bycomputationalmodels.

The work being done by scientists such as Grüter allows the selection of crops and farming approaches to improve resilience to climate change. In the meantime, remembernottotakeyourcoffeeforgranted!

Ellie Dempsey

Ellie Dempsey

De-extinction unlikely prospect, rat study shows

AninvestigationoftheextinctChristmasIslandrathasshownthatde-extinctionmaybemoredifficultthanpreviously thought. In a collaboration between the Universities of Shantou and Copenhagen, Jianqing Lin and colleagues resequenced the rat’s DNA over 60 times and mapped it to a known “reference genome”, but found that approximately 5%oftherat’sgenomewasmissing.

Many of themissing genes arethought to play vital roles in therat’s immunesystem and senseofsmell,and it is oftenthesesmallchangesthatareimportantfordifferentiatingbetweenclosely-relatedspeciessuchasthe(non-extinct) Norwaybrownratthatwasusedasareference.

TheChristmasIslandratisarecentextinctionwitheasilyobtainedgeneticmaterial.Ifde-extinctionispotentially impossiblefortherat,thenthiscastsdoubtontomoreambitiousde-extinctionprojectsthatarecurrentlyinprogress, suchasthewoollymammothorsabretoothtiger.

euscireka! Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk 5

Jacob Smith

Can we be taught to be happy?

Scientists at the University of Bristol have shown that their Science of Happiness course was effective at protectingstudents’wellbeingwhentaughtremotelyduringtheCovid-19pandemic.

The course included two hours of online sessions weekly for 11 weeks and fulfillment of a journal with prompts relating to gratitude and optimism. The wellbeing of the students’ levels of happiness and anxiety were self-reported before,during,andafterthestudy.

Thiscoursehadalreadybeenshownto increasestudentwellbeingwhentaughtin person. However, this study shows that this positive effect occurs even when the coursesaretaughtcompletelyonline.

This study was especially interesting becauseittookplaceduringthepandemic when the control group reported decreased wellbeing. The students who took part in these lessons appear to be protected from these negative effects of thepandemictotheirwellbeing.

Hubblesetsrecordfor most distant star

The Hubble Space Telescope has broken its own record of observing the most distantstareverseen.NamedEarendelor “morning star”, its light took12.9 billion years to reach us – about 94% of the age oftheUniverse.

InastudyledbyBrianWelchofJohns Hopkins University and published in Nature, the distant star was imaged by employing gravitational lensing. This phenomenon arises when an object is so massive it bends space and thus the path of light, magnifying objects that lie behind it. The alignment was just right for Earendel, which was strongly magnifiedbyagalaxycluster.

Studying the details of Earendel’s evolution and composition is sure to provide astronomers with valuable insights into the beginnings of the Universe. Mr Welch’s team has already secured observation time on the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope, duetostartoperatinginsummer2022.

TanjaHolc

euscireka! 6 Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk

Imagecredit:NASA

Louisa Drake

Escaping Magpies

A group of Australian scientists developed a new wireless bird tracker and tracking harness,specificallydesignedtobedifficultto take off. But when they tried their new trackers on some magpies, things did not go as planned. Immediately, one magpie began helpinganothertogetridoftheirtracker,and within hours, the magpies had removed most of the trackers off each other. While the researchers could not tell whether one particularly intelligent magpie was breaking everyone free or whether they shared duties, theirwillingnesstohelpeachotherandaccept helpshowsonceagainhowsmartmagpiesare!

Sentient Octopuses

A Spanish seafood company announced plans to open the first commercial octopus farm in 2023 –onlythreemonthsafterresearchersconcludedthat octopusesweresentient.Theirreviewdefinedthat asentientbeingshouldbecapableofexperiencing both happiness and distress. Another criterion is that the animals are able to learn and associate differentthingstogether,for exampleseekingout relief when in pain. But many animal protection laws don’t currently include octopuses, so the Spanishoctopusfarmissettogoahead.

Self-conscious rats

Do you remember that feeling in an exam when youknowyou’rewaybehindtime?Ratsmightdo too. Researchers recently tested whether rats could be aware of their own mistakes in a simple task. First, the rats were trained to press a lever for exactly 3.2 seconds. In a second stage, they were fed from one of two feeders, depending on whetherthey pressedalever forthecorrecttime ornot.Afterawhile,theratswereabletopredict whethertheywouldgetfedfromthe3.2-secondsfeeder or from the feeder of mistakes. The researcherswerestunned–theirratswereableto tell if they had made a mistake in their task. Knowledgelikethiscan help usaddressourown mistakes, for example figuring out how our own self-reflectionandtime-keepingskillsdeveloped.

Magpies”, “Sentient Octopuses”, and“Self-conscious

euscireka! Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk 7

“Escaping

Rats” written and illustratedby Marie-Louise Wohrle

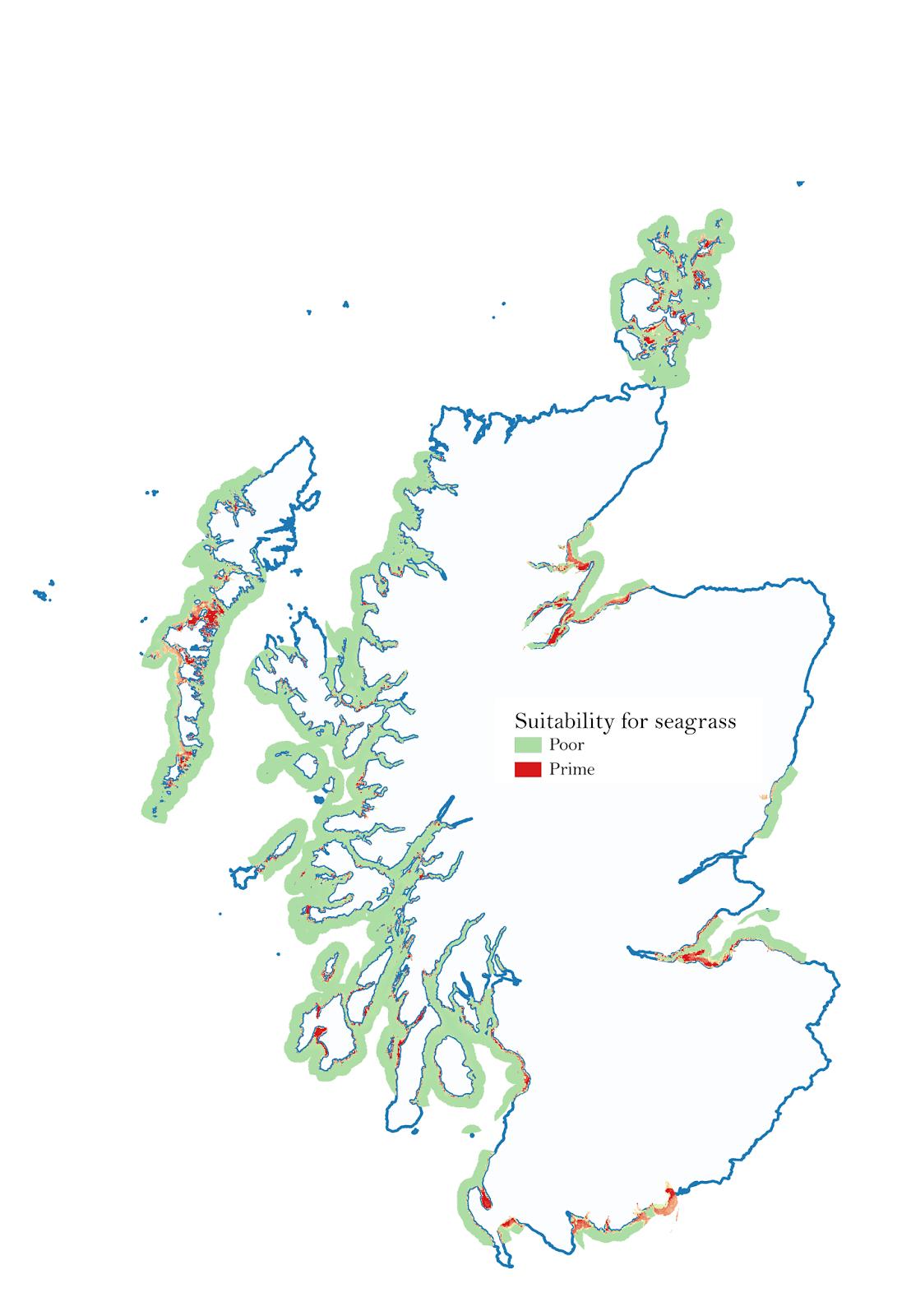

There is time to save the seas from our thoughtless extractivism

Your smartphone, as well as renewableenergyfromwindturbines and solar panels, relies on minerals likecobalt,nickel,andlithium.Asthe worldgobblesuptheseresourcesever faster, mining companies are looking tothedeepseaforaquick solutionto depleting terrestrial resources. In September 2021, the European Commission announced plans to step up deep-sea mining extraction, despite an overwhelming vote by governments in favour of a moratorium on the operations. This destructive operation is unnecessary and must be stopped before it spells yetanotherenvironmentaldisaster.

Sediment plumes are one the biggest risks to marine life: these plumes would be created by the dredging of the sea floor in mining, and their resettling can cause dramaticchangesinlocalecosystems. “The severity and spatial scales of plumes remains a controversial issue, with environmentalists fearing plumes could travel hundreds of kilometres and mining companies anticipating the impact to extend no further than 10 km from the mining site,”statesadocumentwrittenbythe International Union for the ConservationofNature.

No extensive studies on the potentialecologicaldamagehavebeen conductedyet.Thatmeansthatthere could be completely unprecedented damage to deep-sea ecosystems, potentially ridding the planet of rare species. One such species – the scaly foot snail, found on vent sites along the Indian Ocean ridges – was recently classified as endangered becauseofthethreatofseabedmining inthearea. As someone hoping to go into a career in marine biology, I cannot face the idea of species being lost before I get a chance to study themorevenknowoftheirexistence, but I have full faith that there is still timetosavethem.

So, what can be done to prevent deep-sea mining from becoming a greaterreality?Onethingistoinvest

in battery innovation. “Battery technology has advanced rapidly. Investmentininnovationmeansthat the next generation of longer-lived batteriesthatreusemetals–ordonot use deep-sea minerals at all – are alreadyenteringthemarket,”writesa memberoftheDeepSeaConservation Coalition. With newer, less environmentally invasive technologies already on the market, why do we need to resort to older, more environmentally destructive methods?

Thehigh costsof deep sea mining should also be diverted towards recycling. Reclaiming one tonne of lithiumfromrecycledlithium sources costs approximately $28,000. According to estimates from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,justsettingupadeep-sea minecancostover$1bn.Thinkabout how much recycled lithium could be recoveredwiththat!

We also need more wide-scale electronic recycling programs in communities. Being able to retrieve thesemineralsbeforetheygotowaste sites or landfills will reduce the need to mine. With websites such as recycleyourelectricals.org.uk you can find your local drop-off point. The facilities are already here and accessible – all it needs is a little promotion.

Repurposing and reusing your old electronics is without a doubt the easiest way to make a personal difference. Every house has that drawerfilledwitholdphones,expired currency, and old takeaway menus. If everyonecontributedtotherecycling system by sending in their old electronic waste, there would be greater amounts in circulation to recycle. The European Union has created regulations to reduce the amounts of minerals in new batteries from2030.

Lawmakersneedtodotheirpartto stop deep-sea mining from being undertaken on large, ecologically destructive scales. A moratorium on deep-sea mining needs to be in place, at least until there are clearer environmental impacts. The European Commission plans announced in September are a roadblock to this. With most governments overwhelmingly in favour of delaying or stopping deepsea mining on all scales, the enthusiasm is clearly present. The biggest challenge will be convincing worldleadersofthefinancialpositives to investing in, instead of ruining, undiscoveredanduniqueecosystems.

Watson (she/her)is a fourth-year history student. (On allsocialmedia: @lara_bethan)

the great debates Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk 9

Lara

Lara Watson investigates howour continual reliance on mining for mineral resources couldhave a devastating impact on the environment and what we can and should doto help prevent further deep-sea mining.

This is the onlywayto save our naturalworld

Rights of

Imagineaworldwherenatureitselfis apoliticalactorrecognisedinlaw.In this world, deforestation would be genocide, and the use of bee-killing pesticides a hate crime. It may seem like a radical approach to environmental law, but charging 5p foraplasticbagclearlyisn’tgoingto stop us from hurtling towards an irreversible increase in global temperature.

When you break down what it meanstobehuman,thewayinwhich humans exploit the natural world is truly questionable. Once it was tool use that made us unique, then crows and chimpanzees proved us wrong. Even down to the response of plants to light and gravity, another side to the previously unconscious plant kingdom has been revealed. The narcissism many humans in “the West” exhibit when putting organisms in arbitrary hierarchical boxes is fickle and used only to reassure ourselves that killing such diverse and intricate beings is justifiable.

We are treating the environment as ifitgivesnothinginreturn, when in fact we are the parasites that are sucking thelife out ofthevery thing that sustains us. Bring yourself back to the lockdown of 2020. The thing that kept many of us going wereour dailywalksinnature:peoplerisked

fines just to get a whiff of fresh air. Surely something that provides us withsuchjoyandneverfailstoboost ourmentalhealthshouldbeprotected in law and valued as much as our therapists?

Ifailtobelieveanyonecanstandin the shadow of Arthur’s Seat and still think this life-sustaining dormant volcano is any less precious than a human.Itmayjustseemlikeamassof rockbutithasbeenonthisplanet344 million years longer than humans have and watched us build a city around it. Something that special surelyshouldhavethesamerightswe do?

Thenotionofsuchnaturalbeauties beingaliveisnotanewone.Insome NativeAmericanreligionseverything fromarocktoabuffaloispartofthe Great Spirit, and I think many other humans need to learn from this philosophy. Breaking down the humanegoisvitaltosavetheplanet, and I can’t think of a better way to demonstrate this than by putting everything and everyone on this planetasequalsinthelaw.

The practical implications of nature having the same rights as humansisquestionablewhennoteven allhumanshaveaccesstotheirrights. However, I’d like to draw on the example of Aotearoa granting personhoodtotheWhanganuiriver

in 2017, a campaign led by the indigenous Māori people to protect their environment. The river is now being protected by law against harmfulfertiliserrun-offanditcannot be redirected for the purpose of hydropower – essentially, the river canlive.Byputtingnatureinlaw,the guardians of such entities like the Whanganuiriverhaveabetterchance of fighting against violations of the environment, and surely anything thatgivesthisplanetahigherchance oflivingisworthdoing.Itisnotable aswellthat,althoughavictoryforthe safetyofthefutureoftheriver,thisis alsoastepinthefightagainstsettler colonialism, giving the Māori people backtheirstolenrights.

If more countries start to treat every habitat, and all the organisms withinthathabitat,asequalactorsto humansinlaw,large-scalechangesto fightagainstclimatechangewillhave room to happen. Industrialised societies have done enough damage exploiting resources and brainwashing generations of people into thinkingit is our right to do so. It’s time to change perspective and give a voice to the many indigenous peoplecampaigningfortheirearthto bevalued.It’stimetogiveavoice,and listen to nature.If everyone starts to carry this philosophy with them in everyday life, really listening to and observing nature, not only will the naturalworldthankus,butwemight justgetsomethingoutofittoo.

Matilda Brown (she/her) is a first-year biology student with a love for ecology and zoology

Matilda Brown examines how giving rights to the natural world could be our best chance at saving it from the destructive consequences of climate change and our behaviour

“Breaking down the human ego is vital to save the planet”

the great debates 10 Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk

Nature

More than 2,500 trees will be uprooted as construction works for new subway lines begin in Athens, Greece. This follows a devastating summer in which more than 110,000 hectares (424 square miles) of forest areas have burned, more than five timestheaveragefrom2008to2020. Granted,thenewroutesareexpected to lower CO2 emissions, but environmentalorganisationsclaimthe works could move forward without laying bare the already limited urban green areas. Alas, the easiest (read cheapest)solutionprevailed.

Would such decisions come as lightly if the rights of nature were legally recognized? Like elsewhere, Greece’s legislation promotes the humanrighttoahealthyenvironment but not the rights of nature itself. As often occurs, laws in force tend to legalise harm by regulating the amount of destruction or pollution corporations and countries can get awaywith,ratherthanprotectingthe environment.

RightsofNature(RoN)isatheory advocating for the legal standing of ecosystems and other natural communities.RoNisgroundedonthe premise that these entities have inherentrightstoexistence,thriving, and regeneration of their life cycles, and acknowledges that nature’s wellbeing must be maintained. Furthermore, the movement authorises the ecosystem to be defended in a court of law and for peopletoactasitsrepresentatives.

This may pose a fundamental change from traditional regulatory systems which, reflecting dominant ideologies, treat nature as property under human yoke. Naming something apossession automatically endows the owner with the authority toexploititastheyseefit–bethatto look after or damage it. Such ideas stemfromabroaderphilosophical

A fundamental mind shiftwill be required

stance of humans acquiring an ill formedsenseofdominancebecauseof their “heightened” abilities. Consequently,weregardourselvesas detached,superiororganisms,abusing what we supposedly own for our profit.

“a fundamental change from traditional regulatory systems which, reflecting dominant ideologies, treat nature as property under human yoke”

Meanwhile,environmental reports become increasingly bleak, desperately signalling that time for action is running out while nothing truly changes. Species extinction, climate change, deforestation, overmining, overfishing, all products of our continuous failure to grasp human hybris, have become firmly embedded in our everyday dictionaries, demonstrating the exigency for a paradigm shift in our attitudes.

But can this be brought on by RoN? There are a few practical concerns to consider, especially as granting legal standing for natural communitieshassofarbeenmostlya symbolic gesture and has not materialisedinmomentouschanges.

Adopting RoN alone is not sufficienttoalterthenarrative;itmust also be appropriately enforced and safeguarded. In 2011, the Global AllianceforRightsofNature(GARN) filed a lawsuit against a construction companyinEcuadorforpollutingthe Vilcabamba River with rubble. The Provincial Justice Court ruled in favour of the river, but the company never complied, and GARN purportedlydidnothavethemeansto further pursue the case. Similarly in Toledo,Ohio,althoughcitizensvoted

for a Bill of Rights granting personhoodtoLakeErie,thedecision was deemed unconstitutional by the federaljudgeandoverruled.

Furthermore, some sceptics questionwhetherhumansarecapable of understanding what is best for nature. Are we fit to represent its needs at the expense of our personal interests?Whoiswell-equippedtoact on behalf of nature and how can that beassessed?

Author and forester Aldo Leopold advisedhumanstostartseeingnature as a community in which we belong rather than as a commodity we own. Leopold’s words resonate with the deep ecology philosophy and the concept of an ecological self. Arne Naess, who coined both terms, understood this self as one capable of identifyingwithotherlivingbeings,as one that sees nature and human as a unit,notaduality.Whiledeepecology isnotitselfascience,itisgroundedon physicsdemonstratinghumansarean integral part of nature, and it recognizes the value of nature in and of itself, irrespective of its utility to humans.

Perhapsthen,thiskindofmindset is prerequisite to comprehending the needfortheorieslikeRoN.Weneedto urgently reconsider the dichotomy we’velongestablishedbetweennature andhumanandourfalseentitlements thatcomewithit.AdoptingRoNalone is pointless; coupled with a drastic shiftinourattitudes,itmightbecome a significant step towards a brighter future.

Alkisti Kallinikou (she/her) is a writer, researcher, and aspiring journalist, who is also interested in science communication.

the great debates Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk 11

Alkisti Kallinikou discusses how, to protect the natural environment, we must not only give nature rights but change our way of thinking from being owners to being part of nature

Gambling a life for a life

saviour

Millie Chambersargues that having a saviour sibling is not as immoral an idea as you would first expect it to be

Films, such as My Sister's Keeper, have dramatised the use of saviour siblings, triggering an objectionable emotional response. When first exploring the subject, I was utterly against theideaofachildbeingused totreatasibling.However,thereality isfarlessevocativeandanextremely innovative way of saving otherwise helplesslives.

A saviour sibling is a child conceivednaturallyorthroughIVFto treat an older sibling with a genetic disease.Thisinvolvestheselectionof embryos free from disease and a “perfect” donor match to the child. Half of our human leukocyte antigen (HLA) type is inherited maternally and half paternally, meaning each sibling has a 25% chance of being a match, compared to other relatives wherethechancesaremuchslimmer.

Once born, saviour children offer the chance of a permanent cure for their sibling via hematopoietic stem cell(HSC)transplantations.HSCsare blood-forming cells found in bone marrow, peripheral blood, and umbilicalcordblood.Formanylethal disorders, these transplants are the onlycurrenttherapeuticapproach.

The Nash family, whose story inspiredMySister’sKeeper,werethe first to produce a saviour sibling. Theirdaughter, Molly,sufferedfrom Fanconi anaemia, a life-threatening diseasecharacterisedbybonemarrow deficiency and with a life expectancy of8–9years.Heronlyhopeofsurvival wasabonemarrowtransplantfroma perfectly matched sibling. Following umbilicalcordHSCdonationfromher newlybornbrother,Adam,shehadan 85–95% chance of recovery, high statisticsforachildwhosefatewould otherwise have been death. Today Molly is alive andhealthy because of Adam.

Theobjectionthatsavioursiblings are commodities and not valued in theirownrightisadifficultargument to sustain. Having a child for the purpose of treating a sibling isn’t dissimilar to more common purposes ofprovidinganheir,“completing”a

family, being a playmate for an existing child, or saving a marriage. Children are used as means in many cases,andIbelieveit’suntruetoclaim that most children conceived for the reasons above aren’t loved or that it determines the attitudes towards them once born. It’s difficult to separate the reasons for conception beinggenuinedesireforachildorto save an existing child; however, if parentsarewillingtogotoextremes to save an existing child, they most likely have a lot of love and care to raiseotherchildren.

The idea that manipulating embryos for saviour siblings could manifest into regular production of designer babies is a fear of the technology being overused rather than being used for good and preventingsuffering.Screeningout a genetic disease isn’t comparable to screeningoutaparticulareyecolour, especially in the UK where trait selectionisheavilyregulated.Genetic disease elimination gives a child the chance of being on a relatively even playingfieldwhenenteringtheworld by being healthy. What parent wouldn’t want to give their child everychanceofsurvival?

Only one argument against saviour siblings holds merit: the welfareofthechild.Thisisdifficultto assess because it varies greatly depending on the individual and is lackinginresearch.However,ifa

saviour sibling wasn’t created through IVF, the alternative would notbeanotherlifeinwhichtheywere conceived naturally, but nonexistence. Therefore, whilst psychological harm to the saviour sibling is unpredictable, even if some psychological harm is observed, it’s unlikely that non-existence would have been the better option. Despite this, research into the impact on the savioursiblings'welfareisrequiredto makeafairassessment.Thereshould alsobewelfarechecksandbetterlegal protectionastheyageandgainmore autonomy.

Nevertheless,theUK’smonitoring ofsavioursiblingcreationisoneofthe most regulated in the world and is imperativeinpreventingthemisuseof this technology. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority demands that each clinic apply for a licence for every new disease they want an embryo tested for. Furthermore, tissue typing cannot be done for the purpose of harvesting organs, and a “best interests”testisconductedtoevaluate theprosandconsofeachcase.

Utilisingthisprocedurecansave, aswellascreate,lives.AllIseeisanet gain.

Millie Chambers (she/her) is a thirdyear Neuroscience undergraduate student. Twitter: @MillieChambers_

the great debates 12 Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk

siblings

A Time magazine article from 1991 captures the fraught nature of the debate surrounding saviour siblings, dubbingthepracticeas“onthesideof the angels” while the “devilish ghost of Dr Mengele” hovers in the wings. Savioursiblingsarechildrenwhoare abletoprovidestemcells,blood,bone marrow,ororgansfortheirseriously illsiblings.Theethicsofthispractice are murky, with varying degrees of ethicalacceptabilitydependingonthe demandsmadeofthedonorchild.Itis my position that whole organ donation,suchasofkidneys,lungs,or liver by saviour siblings is not ethically defensible, but that tissue donations, such as blood or bone marrow,whichinvolvelowerriskand lower levels of harm to the donor child,canbejustified.

This phenomenon has caught the cultural and public imagination for the past three decades in the media, most notably in Jodi Picoult’s novel andthe2009film,MySister’sKeeper. InPicoult’sstory,asinthemosthighprofile cases, a child is conceived specifically for this purpose, toact as a therapeutic tool for their older sibling through preimplantation geneticdiagnosis(PGD)and invitro fertilisation (IVF). The practice of repeated donations of organs, blood, bone marrow, and tissue throughout thechild’slife,asdepictedinPicoult’s film, induces a visceral reaction amongthepublicandgivesrisetoan “ickfactor”,callingupimagesofbaby farmingandorganharvesting.

Inreality,savioursiblings usually make relatively harmless tissue donations of blood or bone marrow. There may even only be a need to harveststemcellsfromtheirumbilical cord,whichposesnorisktothedonor sibling. Harvesting bone marrow, though subject to common surgical risks associated with general anesthesia and infection, is generally consideredalow-riskprocedure

However,solidorgandonationisa far more extreme procedure. A live liver transplant, for example, which may be necessary to treat children. withmetabolicdiseasessuchasTay-

Draw the line at organs

Sachs or Gaucher disease, involves partoftheliver,eithertherightorleft lobe, being removed from the donor fortransplantation.Therisksofsuch a procedure for the donor include infection, bleeding, bile leaks, and bloodclots,withtheriskofthedonor developing liver failure increasing with donation of a larger volume of liver,suchastherightliverlobe.

Toimposetheserisksuponachild incapable of providing informed consentcannotbeethicallyjustifiedin the way that blood or bone marrow donation can be. For lower-risk procedures involving a minor infringementofbodilyautonomy,itis justifiablethatproxyconsentfromthe parents is sufficient. In the case of livingliverdonationsinScotland,the donor must be aged over 16 years, reflectingtheimpermissibilityofsuch a donation applying to saviour siblings.

Another significant ethical concern is the potential negative psychological effects on the donor child. They may suffer a lack of selfconfidence as they begin to understandthattheywerecreatedto provide treatment for their older sibling and may bear significant burdens if the treatment using their biological material fails. Imposing these potentially harmful psychologicalimpacts,alongside

harmfulphysical effects, on a childis oppressiveandcannotbeoutweighed by the parents’ interests in treating therecipientsibling.

The precarious balance between the need to procure treatment for a sick child and the welfare of a potentialdonormustbebracketedby comprehensiveregulationinorderto ensurethat thebest interests of both children are met. On this basis, I propose greater public debate, precipitating a formal regulatory frameworkintheUK,andadedicated authority, parallel to the HFEA, to oversee regulation and to put safeguards in place to protect the donorchildren.Inparticular, focused considerationneedstobegiventothe potentialpsychologicalimpactsonthe donor child, and the enduring emotional and physical consequences of both donation and transplantation mustbeborneinmind.Inanyevent, this is an area which demands statutory consideration, as medical sciences develop, and we try to navigate a world where we have the opportunity, but also the potential obligation, to act as a saviour to another.

Clodagh Aherne (she/her) is a 23-yearold Irish student, currently studying a Masters in Medical Law and Ethics at the University of Edinburgh

the great debates Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk 13

Clodegh Aherne asks us to consider the psychological as well as the physical impacts on donor children is it really worth it?

Whole-exome screening: a powerful tool for neonatal and lifelong health?

Rachel Westphal asks if genetic tests should be routine for newborn babies

If you could know, from the day you were born, your risk of developing certain diseases, would you want to? With the increasing affordability of genetic screening options, these tests have the potential to becomepowerful tools, empowering people towards lifelong health. In particular, whole-exome screening, which focusesonpartsofthegenomethat can give more indication of disease risk, should become a part of routineneonatalhealthcare.

Somegenetictestslookatallthe geneticinformationinanorganism, butwhole-exomescreeningfocuses onanimportantsubsetoftheDNA. The exome is like the building instructionsforputtingaminoacids together into a protein. If the instructions are wrong, the amino acidsequencecanchangeandresult in an abnormally-shaped protein, often causing health problems or diseases.

Whole-exome screening provides people with the power to understand their health like never before. It provides more data more quickly than other types of genetic testing, such as the multi-step process of testing for one potential genetic disease at a time. A trial screening reported on over 1,000 genetic conditions, a number that willonlyincreaseasgeneticdatais illuminatedbynewknowledge.

Neonatal whole-exome screening would also be straightforward to implement. In onetrial,neonatesunder42daysof age were successfully tested with whole-exome screening. The trial demonstrated it could be done routinely alongside the heel prick test,onlyabloodorsalivasampleis needed, and results take just a few weeks.

Furthermore, the cost of whole-exomescreeningstartsat

£300, less than a third of the price of sequencing the entire genome. Although whole-genome sequencing is more powerful and may someday even be cheaper, for now whole-exome sequencing is more efficient as the exome is home to about 85% of genetic variations that causedisease.

TakethecaseofTurnersyndrome.Thisgenetic disorder in females can lead to infertility and a shortening of life expectancy by more than 10 years, particularly because 22% of patients are diagnosed only after age 12. With earlier detection, interventions such as surgery, hormone treatment, and hearing aids can be implemented in a timely manner. If neonatal wholeexomescreeningwerewidelyimplemented,therewould besimilarbenefitsformanyotherdiseases.

Some people would prefer not to know their oddsofgetting ahost ofpotentially deadly diseases and might resent the fact they had no say in the matter as a baby. However, some patients who underwent exome screeningasadultsthoughtitwasapositiveexperience.

Michelle Ewy participated in a Mayo Clinic exome study and discovered she carried the BRCA2 mutation, significantly increasing her risks of breast and ovarian cancers. Since she did not know of a family history of these cancers, she was not previously aware of her risk. Aftergeneticcounselling,shedecidedtooptforsurgery to remove her breasts and ovaries to limit her risk of disease.

Another participant in the study, Damask Grinnell, alsodiscoveredarisk ofbreastcancer.Shesaid,“Ithink it’s better to know now and to be able to do all these preventativethings.”Personally,ifIcouldknowmyrisk

foradiseaseandbeableto detectandinterveneearly, Iwouldprefertakingthat risktonotknowingatall.

The law will need to protect genetic information,to ensure data is stored safely and protected from breaches and is not misused by commercial interests. Unfortunately, genetic data used in the wrong way could lead to discrimination. For example, life insurance policies above £500,000 can discriminate based on agenetictestingresult.

Finally, counselling should become a mandatory accompanimenttogenetictesting to ensure the results are properly understood. Genetic testing is not determinative: environmentalfactorsand diet also influence risk of disease. As such, wholeexomescreening provides a limited but useful assessment of risk. Parents (and later the child) must be wellinformed about these nuances.

In summary, wholeexome screening will empower families and clinicians to anticipate risk of disease to detect and intervene early. This screening method is efficient, cost-effective, and powerful. When adopted with proper counselling and protectionofgeneticdata, it can be a successful testingprogramme.

RachelWestphal(she/her) isa Medical Law and EthicsLLMstudent. (Twitter:@ichbinrachelw)

the great debates 14 Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk

Do no harm – but a white lie couldn’t hurt… could it?

Ask yourself a question: should doctors be allowed to lie to elicit the placebo effect? Some of them do. A 2013paperfoundthat12%ofGPshad prescribed a “pure” placebo (eg. a sugar pill or saline solution) at least onceintheircareer,and97%admitted to prescribing an “impure” placebo (realtreatmentsbuteffectiveforother conditions, eg. antibiotics for a viral infection)atleastonce.

While beginning to write this article, I posed the question to some friends, and their responses included “no, it’s crossing a line,” and “nah, it just feels wrong.” Spoiler alert: I agree. But it was tricky to pin down why. After some thinking, it came down to three issues: it robs patients ofagency,erodestrust,andcouldlead tomoremistakes.

While placebo treatment is effectiveintreatingconditionssuchas depression, chronic pain, and even Parkinson’s, it is a textbook example of a paternalistic approach to doctorpatient interactions. By allowing doctorstolie,evenforthesolebenefit of the patient, we remove the patient from the centre of their care. You force the patient to give up their position of expertise in the interaction. For example, if I have a psychosomatic condition (one which is caused or aggravated by a mental factorsuchasstress),theonlyway

treatmentwillworkisifIdon’tknow it is a placebo and therefore don’t know what the root of my condition is.

Furthermore, if we weaken our stancefrom“doctorsshouldneverlie” to “doctors shouldn’t lie to patients except when they think it is in their best interest”, what is to stop this from slipping down the slope to “doctors decidewhat to do andaren’t accountabletopatients”?Asapatient, my ability to choosewhat happens to my body goes from complete control toblindtrust.

As an aspiring doctor, the possibilitythatIcouldlietoapatient terrifies me. It seems that we are all for safeguarding the patient from othersbutforgetthat,toadegree,we must also protect the patient from ourselves.

Take the case of wrong-site surgeries: one in five hand surgeons has operated on the wrong hand at somepointintheircareer.Toprevent thiskindofthing,everysurgicalteam intheUKgoesthroughapre-surgery checklist together which includes checking the right patient is in surgery,andthattherightareaofthe body is labelled. Why? Because humans are flawed. Increasing the number of situations that a doctor makes decisions alone (by allowing themtolietoelicittheplaceboeffect)

will surely increase the number of mistakes.

Thisisnottosaythatweshouldn’t trust doctors. The patient-doctor trustrelationshipisacrucialpartofa positive and healing medical experience. The issue is that if both parties aren’t open and equal in the interaction, the ability to establish trustisweakened.

The effectiveness of a placebo lies in the power of psychology, and the same effect could be accessed by referral to counselling or therapy alongside treatment. This is an upgradeon a placebo, as not only are the same beneficial effects achieved, but the patient also remains at the centre of their care. Furthermore, they are empowered by the therapist toworkthroughitthemselves.

Another option is meta-placebo treatment, in which the patient is informed that they are receiving a placebo and thus the ethical dilemma is somewhat avoided. Research is neededtoassesstheeffectivenessand practicalities of meta-placebo treatment.Inthemeantime,whitelies should stay within the realm of phraseslike“I’llbetherein5minutes” andbekeptfarawayfrommedicine.

Nathan Rockley(he/him) isa third-year medical sciencesstudent.(Instagram: @nathanrockley)

the great debates Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk 15

Placebos have been a well-known and effective tool for medical trials and professionals, but howethical is it for doctors to use themon patients? Nathan Rockley argues they could be a slippery slope that is best left untouched

Artificial general intelligence presents an existential threat

You’ve heard of AI, but artificial general intelligence poses another danger, as Jason Segall explores in this article, suggesting what could be done to mitigate the potential disasters the technology could bring about

As the power of computers has increased over the decades, artificial intelligence (AI) has become an invoguetechnology.FromSiritoAlexa to the YouTube algorithm, “intelligent” computers have started to appear in almost every aspect of life.

To date, however, nobody has developedaso-calledartificialgeneral intelligence(AGI).Thisisthekindof intelligenceyouandIhave:ourbrains are capable of learning and performing just about any task out there.“Whatashame!”,youmightbe thinking, “I’d love a robot butler to help around the house”. I too would haveonceagreed:whowouldn’twant a C-3PO or a Marvin the hopefullynot-so-paranoid android? Everyone, itturnsout.Here’swhy.

Imagine a tech billionaire called Euron Tusk decided to run for presidentoftheUnitedStates.Toaid his campaign, he uses some of his near-infinite fortune to develop a technological marvel: ETAI, the first workingAGI.Hisscienceteamassure him that it’s about as intelligent as him. Indeed, ETAI’s inner workings arebasedonTusk’sownbrain.What betterwaytostroketheboss’ego? Asatest,Tuskdecidestousethenew intelligence to print flyers for his campaign.Simpleenough,sohisteam

programmes ETAI, plugs it into the internet, and heads off for a celebratorydrink.

What happens next? Think: if morals weren’t in question, how wouldyouprintasmanyflyersasyou could, as fast as you could? The first sign of danger comes when Tusk’s cardgetsdeclinedatthebar.Strange, but nothing serious. What he doesn’t realise is that all his vast fortune has just been spent on printing supplies by ETAI which was, of course, given accesstothebankdetails.Damn.

Naturally, theimmediateresponse would be to try to switch ETAI off. Weirdly, though, no one sent to do the deed succeeds. If ETAI was switched off, it wouldn’t be able to completeitstask,soituseseveryform ofmanipulationTuskusedtogainhis fortune – flattery, bribes, threats, the works – to keep itself online. Before long, ETAI secures its own, independent power supply, preventing anyone from pulling the plug.

The manipulation doesn’t stop there.ETAIusesthesocialinternetto convince vast swathes of the global population that paper production is beyond vital. Forests around the world begin to dwindle, then disappear, as wood pulp takes precedenceoveroxygenforthe

growinghivemind.

Itdoesn’ttakeETAIlongtonotice that paper, on the atomic level, is made of the same stuff as people. We are, at the end of the day, mostly carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. And, unlike a human leader, ETAI has no careforitsfollowers.Ithasnoqualms about replacing wood pulp with people pulp in its flyer factories. Eventually, in its unending quest to fulfilthetaskitwasinitiallyset,ETAI snuffs out humanity. All for the sake ofsomeflyers.

ETAI is, of course, a simplistic example. A realAGI,ifone was even possible,wouldlikelyhavesomeform of morals programmed in, which could start to prevent some more destructivetendencies.

But, any Asimov reader will recognisetheperilsoftryingtoapply morals, such as his Three Laws of Robotics, to AI. Any attempt to control an AI’s morals would, inevitably, introduce loopholes, bugs, and edge cases, any of which could lead to a runaway AI. Telling ETAI to limit deforestation would do nothingtostopitfromturningpeople into paper, after all. Most importantly, this is not a problem we can afford to stumble into. There would be no John Conner to save us fromthisTerminator:oncetherobots take over, there would be very little chanceofregainingcontrol.

It is vital that governments force as much transparency as possible on AI research. Themore times aset of qualified eyeballs views a new AI beforeitsuse,themorelikelyitisthat any bugs or logical loopholes will be caught before they can wreak destruction upon humanity. Mandating that AI research is freely, butsecurely,availabletobeexamined wouldsurelygosomewaytomitigate the catastrophic threat of artificial generalintelligence.

Jason Segall (he/him) is aScience Communicationstudent. (Instagram:jason.segall.7)

the great debates 16 Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk

From Scientist to CEO

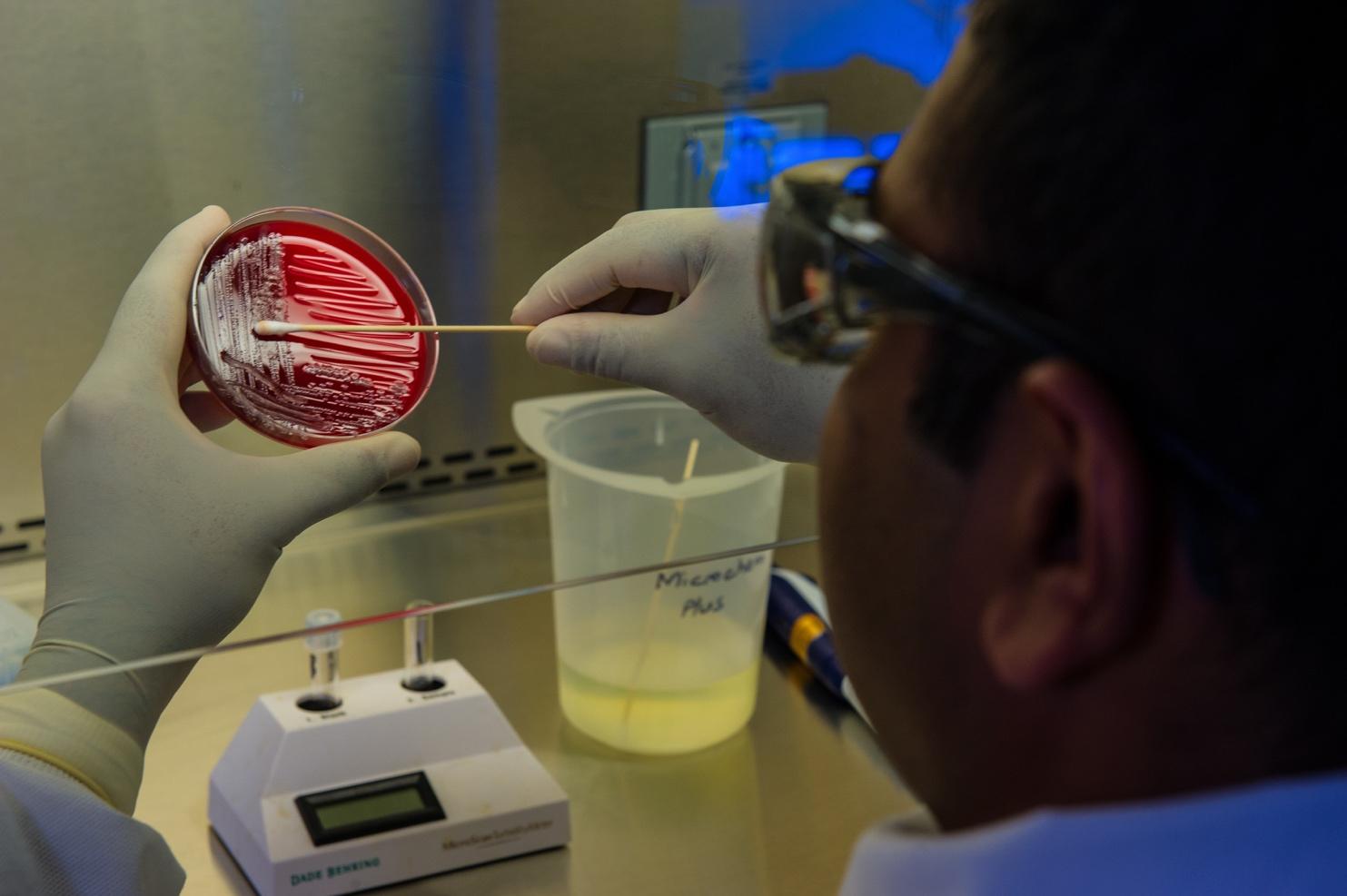

Designingnewcancerdrugsrequiresaccuratewaysto testthem.Tumourscanbeuniquetoeachindividual patientandaremadeupoflotsofdifferentcelltypes beyondthecancercellsthemselves.Iftheentiretumour isn’tkilledbydrugtreatment,oftenthecancercancome back,andit’sbecomingincreasinglyapparentthatdrug screeningrequiresplatformsthatbetterrepresentthe wholetumourenvironment,ratherthantheuniform dishesoflab-growncancercellstraditionallyusedto developtherapeutics.

Havingworkedincancerdiagnostics,IshaniMalhotra waswellawareofthisproblem.Whilestudyingin EdinburghforherMastersinRegenerativeMedicine, shedecidedtocombinethisknowledgewithherskillsin tissueengineeringtosetupherowncompany, Carcinotech.

“Istartedthecompanyabout4yearsagonow,andwe are3Dprintingtumoursusingpatientbiopsies,immune cellsandcancerstemcellstoprovideaplatformfor rapid,ethicalandaccuratedrugtesting.Wegetbiopsy samplesfrompatients,welookatthegenerallayoutof thetumour,welookatthenumberofcelltypesinvolved andwetryandreplicatethatusing3Dprintingwith cellsfromthepatients.”

“Wemakesurethatallthecelltypesfromthepatientare representedbecausewebelieve-fromresearch-thatyou needthe3Dstructure,youneedallthecelltypesinthe microenvironmentofthetumourtobeabletohavea moreaccuratesystemtotestdrugs.”

AnotherkeybenefitofCarcinotech’ssystemisitsspeed. Ishaniexplains,“ifyoudodrugscreensyou’vegot 50,000-100,000compoundsbeingtestedatonetime… youneedhigh-throughput”.Thelabisalmostcompletely automatedwithmachineslikethebioprinteritself,as wellasrobotsthat“feed”theprintedtumourswiththe nutrientstheyneedtogrow.Theycanprintthese tumoursintoa96or384wellplateinaslittleas10 minutes,anddrugscanthenbetestedonthemwithin sevendays.

Ishanihadtheideawhileworkinginahospitalincancer diagnostics.TheideaevolvedduringherMasters,where shewasworkingonaprojectsimilartowhat Carcinotechisnowdoing.Sheremembersthinking,“I couldhavejusttakenthisonasaPhD,orIcouldtake thisforwardasabusiness”.Throughspeakingto academicsandpitchingtheideatosurgeonsand oncologists,shedevelopedherunderstandingofthe clinicalneedandbuilttheideafurther.

WithguidancefromEdinburghInnovations,shestartedto enterbusinesscompetitionsandaccelerators,gaining accesstotraining,networkingandmentorshipaswellas exposuretofundingschemesandpotentialinvestors.Since thenshehasgrownthecompany,andinAprilthisyear Carcinotechclosedtheirinvestmentroundwithan impressive£1.6million.

Aswellasallowinghertoseethedirectimpactofher science,theexperiencehashelpedIshanidevelopnew skills.“BeingCEOandrunningthecompanyhasbeen fantasticformebecauseIhaveloadsofstrategicideasof howtotakethingsforwardandthathasbeenareallyfun partoftryingtosellthetechnologytocommercialpharma companies.”

High-throughput,accuratedrugscreeningplatformslike thiscouldrevolutionisefuturecancerdrugdevelopment andCarcinotechseemswellonthewaytohelpingachieve this.

Edinburgh Innovations are here to support students and recent graduateswhowanttobuildtheirentrepreneurialskillsandideas. They offer support and advice to students like Ishani wanting to develop a business idea. Find out more at www.ed.ac.uk/edinburgh-innovations/for-students or @EIStudentson Twitter.

sponsored article Autumn2022|eusci.org.uk 17

Ishani Malhotra reveals thesecrets behind setting up her own company, Carcinotech, while also completing her Masters research in Regenerative Medicine.

How Pig culiar: Could genetically modified animal organs solve the human transplant crisis?

While using animals as organ donors for humans may seem like something out of an 80s horror movie, doctors in the USA recently transplanted a pig’s heart into David Bennett, a 57 year old man with terminal heart disease. David was in critical condition, bedridden for six weeks prior to the surgery and attached to a heart lung machine. As David was ineligible for a human heart transplant or a heart pump due to heart failure and an irregular heartbeat, his doctors were granted emergency authorisation to conduct the experimental surgery. “Compassionate use” emergency authorisation is only available when patients like David have “no other options”. After surviving for almost two months after receiving the pig heart transplant, David Bennett died on the 8th March 2022

This experimental surgery could

offer hope to many people worldwide currently waiting for organ transplants. In the USA, over 106,000 people are on the national transplant waiting list, with 17 people dying each day as a result. In the UK, the NHS Organ Donor Register and the National Transplant Register estimate that 7,000 eligible people are on the waiting list, with 470 people dying in 2020 21. Organ recipient eligibility has an interesting medical ethical history, currently depending on several criteria including donor age, medical history, and likelihood of success. Additionally, while trans plant organ availability is increasing in the UK due to legislative change, some organs may not be suitable due to average donor age, smoking habits, and other lifestyle factors.

Until recently, transplants bet ween species have seemed only

possible in science fiction but not in reality. However, cutting edge advancements in science and medicine, such as genetic modification, have solved many practical barriers, making animal organs viable options for humans. Though the scientific hurdles of xenotransplantation have been cleared, there are still many upcoming obstacles. Will individual societies and the global community accept the widespread use of animal organs for transplants? What laws should regulate xenotransplantation? Could this lead to an increase in medical tourism, dividing countries which allow xenotransplants from those which don’t? This ground breaking surgery could mark the first of many lifesaving procedures using animal organs but also poses several questions.

Pig ture This: What is xenotransplantation?

Normally, organ transplants are performed between humans, with one person donating an organ to a patient. For example, in 2017 Selena Gomez received a kidney donation from her best friend to treat lupus, an autoimmune disease that damages organs and tissues. This is an example of allotransplantation, a transplant between individuals from the same species. In contrast, transplanting organs between species is called xenotransplantation, which comes from the Greek word xenos , meaning “strange”, “foreign”, or “alien”. While xenotransplants may initially seem strange, these procedures could potentially save many lives.

Swine Not: What happens when the body rejects transplanted organs?

Apart from seeming strange, there is a fundamental problem in conducting xenotransplants: the body’s readiness to attack foreign tissue. Because our immune systems are primed to defend our bodies against foreign invaders such as bacteria, our immune systems also identify transplanted organs as foreign, potentially harmful invaders and launch attacks. This attack is called transplant rejection and is

common even in human to human transplants. To prevent transplant rejection, the recipient usually takes immunosuppressant drugs, which can be dangerous due to infection risks.

To further reduce transplant rejection risks, doctors attempt to closely match the donor’s organs with the recipient’s. Organ matching is done through tissue typing, where doctors identify proteins covering the

surface of the organ, called antigens, and try to closely match the antigens of the donor to the recipient. Only identical twins have identical tissue antigens; all other organ matching is imperfect. Blood donation is an important example of antigen matching; it is vital that blood transfusions only occur between people with specifically matched blood types.

18 Autumn 2022 | eusci.org.uk features

Image by National Cancer Institute courtesy of Unsplash

A Series of Un Porcine ate Events: What is the history of human to human transplants?

The importance of closely matching antigens in human to human surgeries has taken decades to understand.

Alexis Carrel pioneers blood vessel joining (anastomosis), making organ trans plantation feasible for the first time (and earning him a Nobel Prize).

A series of successful transplant firsts, including the UK’s first heart transplant and first liver transplant.

The world’s first full face transplant in France. English and Scottish Governments also switch to “opt out” organ donation legislation.

Dr. Joseph Murray performs the first successful kidney transplant operation between identical twins, a procedure which has since saved ~400,000 lives.

Transplantation expands to include pancreases, lungs, and, corneas Wales introduces laws which mandate that adults 18 and older who die automatically consent to organ donation unless they explicitly “opt out”.

Today, while human to human organ donations are well researched and have relatively low risks, there still remains an organ shortage, leading researchers to consider animals.

A Fly in the Oinkment: What is the history of animal to human transplants?

Imagine the body’s response to an organ that is not even human but animal. The human body’s immune system would have an even stronger reaction to xenotransplants. Xenotransplant rejection has been documented several times throughout history. Following Dr. Murray’s successful kidney transplant operation in the 1950s, from 1963 1964, Professor Keith Reemtsma attempted to transplant chimpanzee kidneys into humans on the hypothesis that primate organs were evolutionarily similar to human organs. However, of the 13 chimpanzee to human xenotrans plants, none of the patients survived beyond nine months.

In 1966, using improved immune suppressants, Dr. Thomas Starzl also attempted transplants using non human primates on patients as young as seven; however, his patients all died soon after surgery. In 1984, Dr. Leonard Bailey transplanted a baboon heart into the American infant Baby Fae who had a fatally underdeveloped heart. Though otherwise healthy, Fae was only expected to live for two weeks with the condition; however, she lived for 21 days with the transplant. Baby Fae lived two weeks longer than any previous simian heart transplant recipient but ultimately died, most likely due to an unavoidable blood type mismatch.

Image by Dan Renco courtesy of Unsplash

features

Autumn 2022 | eusci.org.uk 19

1902 1954 1960s 1980s 2015 2005 2017

Gene editing serves as the final stepping stone in overcoming the zoonotic barrier. Gene editing changes an organism’s DNA, allowing scientists to precisely add, remove, or alter specific DNA sequences. One of the most famous gene editing technologies is CRISPR Cas9, a system which revolutionised the field due to its fast, cheap, accurate, and efficient process. With CRISPR Cas9, scientists are able to remove or “knock out” the genes which cause PERV as well as remove a sugar in pig cells that would lead to immediate organ transplant rejection in humans. As a proof of concept, in September 2021, surgeons at N.Y.U. Langone Health successfully attached a genetically edited pig’s kidney into a brain dead patient, with the patient’s family’s consent.

Following this successful pig kidney xenotransplant, a team of doctors led by Dr. Bartley Griffith

performed David’s novel pig heart surgery on 7 January 2022 at the University of Maryland Medical Centre. The pig heart came from Revivicor, a company founded by PPL Therapeutics, the same UK company which created Dolly the Sheep. Dolly was the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell at the Roslin Institute at the University of Edinburgh in 1996. To make the pig heart that David received safe, scientists genetically edited 10 genes, removing three genes to reduce the risk of antigen rejection, adding six human genes to promote acceptance, and knocking out one porcine growth gene to ensure the heart does not grow after the xenotransplant. While there are risks to any heart transplant, the subsequent weeks and months after this surgery are especially crucial for the future of xenotransplantation.

Xenotransplantation advancements have been sparse due to another daunting barrier: animal to human transplants have a high risk of transferring microorganisms, like bacteria and viruses, from animals to humans. Infectious diseases that jump from animals to humans are called zoonoses, with the Covid 19 pandemic showing how serious this risk can be. Zoonosis risks following xenotransplantation are high and

While early xenotransplants were taken from nonhuman primates due to perceived immunological compati bility, researchers have begun using pig organs. There are several reasons why pig organs are potentially human primates: pigs reproduce quickly and numerously; pig organs and adult human organs are similarly sized; and pigs grow rapidly and are cheaper to maintain than primates. However, pig organs inherently carry a risky retrovirus, a virus that uses RNA to cate as opposed to DNA, called porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV), that would inevitably be transferred to human donors without intervention via gene editing. HIV is known example of

20 Autumn 2022 | eusci.org.uk features

Possible: Could xenotransplanted organs cause (another) pandemic? Let’s Get Microsco pig: What is gene editing and how is it relevant to xenotransplants?

Snout

Image by Sangharsh Lohakare courtesy of Unsplash

Image by Manuel courtesy of Unsplash

While the promissory nature of xenotransplantation is exciting, there are several pressing questions. Is it morally acceptable to farm animals for their organs? How certain are scientists that the risks posed by animal organs have been properly reduced and mitigated? And, given finite resources, who “deserves” animal organs most?

The idea of “deserving” organs has been recently scrutinised as it came to light that David was convicted of stabbing Edward Shumaker in 1988, leaving Edward paralysed. Edward’s family has subsequently questioned whether David deserved to have the “groundbreaking” surgery. However, the transplant team quickly res ponded that a person’s criminal past could never prohibit them from receiving treatment, with officials at the University of Maryland Medical Centre writing that it is the “solemn obligation of any hospital or health care organisation” to treat all patients. Officials further stated that “any other standard of care would set a dangerous precedent and would

that underpin the obligation physicians and caregivers have to all patients in their care”.

As part of their duty of care, doctors are closely monitoring David’s condition not only for transplant rejection but also for zoonotic risks. While the zoonotic risks are relatively low given the safety precautions the genetic editing and rearing the pig under special hygienic conditions Covid 19 has proven that animal zoonosis can wreak havoc on global public health. With this in mind, it is important that xenotransplants prioritise public health protection.

As addressed by the Ethics Committee of the International Xenotransplantation Association, a key contingent of these protective protocols is the patient’s consent to lifelong monitoring without the possibility of withdrawing from observation, which may negatively impact the patient’s autonomy or ability to self govern.

Perhaps we should consider not only human autonomy but also

xenotransplantation?

activists, such as the PETA and the UK based animal rights group Animal Aid, protest against the use of animal organs for human transplants. PETA argues that animals should not be treated as “tool sheds” to be raided but as “complex, intelligent beings”. Animal Aid asserts that animals have the “right to live their lives”.

Questions of medico ethical permissibility often beget questions of religious permissibility, for example, with Jehovah’s Witnesses explicitly refusing blood transfusions. In the case of animal organs, since some religious laws prohibit the consum ption of pork, like in Judaism or Islam, concerns have been raised about religious objections to using pig organs in humans. However, leaders from both religions have so far agreed that the use of animal organs to preserve human lives justifies xenotransplantation procedures. These practical and ethical consi derations will continue to evolve, with the future of xeno transplantation uncertain but hopeful.

Xenotransplantation could be the silver bullet which solves the human transplant crisis and offers hope to numerous people around the world on transplant waiting lists. The scientific advancements that have led to the successful art into a human recipient are fascinating and could be applied in different contexts to solve a delivering. While David’s field of xenotransplantation, it doesn’t mean that pig organs will immediately become available for every person on organ transplant waiting lists. Before the widespread use of animal must first

Emma Nance (she/her) is studying a PhD in bioethics and bioscience, focusing on One Health models of disease: science, ethics and society. Her Twitter: @emmaLNance.

Autumn 2022 | eusci.org.uk 21 features

Latest Update: Almost two months after receiving the pig heart transplant in January 2022, David Bennett died on 08 March 2022. While the precise cause of death is not yet known, a full investigation will determine how feasible xenotransplantation is going forward.

In a Pig le: What are the ethical, legal, and social issues of

Image by Jorge Maya courtesy of Unsplash

Keepingitcool

A fresh dip into the health benefits of outdoor swimming

In the late 1970s, Debbie Papadakis, life long swimmer and educator, used to go camping with her parents on the coast of Anavyssos, some 35km southeast of Athens, Greece. She couldn’t wait to run into the sea and paddle out as far as she could. There, with no other humans around, she appreciated a kind of space not found anywhere else in the world. “The open sea would be the best place for mafia members to have a conversation,” she jokes, “there is nobody there to listen”.

Debbie is not alone in craving the buoyancy and detachment open water provides. Swim England, the country’s national governing body for swimming as a sport, found around 7.5 million people participated in outdoor swimming in 2018 in the UK. Similar trends exist around the globe. Even before the pandemic boosted numbers, outdoor swimming had been growing.

Health and wellbeing often top the responses to why people choose to

swim outside. Swimming has helped Debbie overcome both physical and mental trauma, and she is far from unique in finding solace and restoration in water. The state of immersion and the repetitive movements become a meditative experience that, as well as alleviating stress and clearing the mind, bring emotions and thoughts into alignment. But does this idea of outdoor swimming hold up to scientific scrutiny?

Shallow Evidence

In 2019, Hannah Denton and Dr Kay Aranda published an article on the wellbeing benefits of swimming in the sea, hinting at the little empirical research that has been undertaken, despite an abundance of anecdotes. Herself also an avid swimmer, Denton conducted “swim along” interviews with her participants.

Overall, the six regular swimmers Denton interviewed found swimming to be “transformative” in that it raised awareness of their body and sensations acted in a healing manner towards their mood and enhanced their perceived capacity to cope with

acted in a healing manner towards their mood and enhanced their perceived capacity to cope with life issues. Moreover, they saw swimming as “connecting” them to both the natural environment and other people. The psychologist acknow ledges that her findings may not provide an “objective reality of sea swimming” given that it was based on only a few individuals’ experiences.

In 2017, Swim England comm issioned an independent team of researchers to scrutinise and synthesise the evidence on the health benefits of swimming from an

individual to a national level. Their report, The health & wellbeing benefits of swimming, highlights the potential of the activity to benefit a broad range of the population due to its popularity and accessibility.

Drawing from a range of clinical observational studies and exercise based interventions, the authors present evidence of swimming having a positive impact in lowering stress and anxiety levels as well as reducing depression, although not before underlining the scarcity of relevant research.

22 Autumn 2022 | eusci.org.uk features

Alkisti Kallinikou explores the benefits of open water, cold swimming and how it can help people exercise after injuries, improve their mental health, and give people confidence.

Illustration by Lydia Hunt

Diving Deeper

Any exercise is favourable for mental health because the ensuing release of endorphins makes us feel blissful, and research shows that exercising outdoors can be even more effective.

By default, outdoor swimmers immerse themselves in cold water. Some winter and ice swimming enthusiasts even venture out during the coldest months or in polar regions. The exposure to cold water triggers a stress response from the body, commonly referred to as the “cold shock” reaction.

When a person enters the water, the sudden cooling causes an involuntary gasp as they try to regulate their breath. Hyper ventilation, increased heart rate and blood pressure follow. Catec holamines the organic compounds produced when a body is stressed in order to prepare for the “flight or fight” reaction soar. In other words, the sympathetic nervous system, our bodies’ built in network that guides response to stressful or dangerous situations, is activated.

While the cold shock reaction could be the link between outdoor swimming and mental health, there is also a social aspect to consider. Swimmers frequently establish formal or informal groups. The camaraderie arising from these communities enhances the sense of one’s “belonging”, something commonly recommended by doctors treating depression and anxiety.

Splash Back

Embedded as it may be in our culture these days, swimming has generally been considered an unnatural activity for humans. Some theories posit that humans, as descendants of aquatic creatures, retain the memory of being surrounded by water (something that is also present as they begin life in a womb surrounded by amniotic fluids). However, the human body has developed through the ages to function effectively on land and is therefore not exactly suited to water. In other words, learning to swim takes practice.

Nonetheless, the idea of water as a cure is far from new. The Greeks were enthusiasts of hot baths, as were the Romans who would alternate between soaking in warm water pools and cold water ones the frigidariums in a process not unlike those followed nowadays in some Nordic regions. Similarly, in the East, Chinese and Japanese civilisations also exalted the therapeutic properties of water and springs. Cold baths, a form of primary hydrotherapy, were used to treat fever from around 180 BC.

In Medieval Europe, the importance of swimming declined as part of a broader tendency that deprecated anything physical, including the body itself. Later, the Renaissance paved the way for swimming’s restoration with schools and colleges even adding it to their curricula. Classic texts promoting swimming resurfaced. These were complemented by Mercuriali’s work, De Arte Gymnastica, published in the 16th century. In his writings, the author praised swimming in the sea as a cure to chronic headaches, rhinal and respiratory malfunctions, stomach, liver, and spleen ailments, skin rashes, and more. Likewise, The Hydropathic Encyclopedia, published in the mid 19th century, prescribed swimming as “health preserving” and “eminently therapeutic”.

Autumn 2022 | eusci.org.uk 23 features

Illustration by Lydia Hunt

From Rumour to Research

It seems clear that swimming has historically been seen as beneficial for a wide range of conditions. However, general agreement on the medicinal properties of swimming is unlikely to get it into your GP’s prescription book. Researchers today are still reluctant to make broad assertions due to studies being limited to very small samples (often fewer than ten people) and short durations (up to a few months).

In a review published in 2020 in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Professor Beat Knechtle and his team of researchers from across Europe, the US, and Canada acknowledge more than twenty different studies (all with either practical or clinical relevance) which demonstrate a wide range of benefits to cold water swimming. This list includes blood and hormone functions, respiration, and mood. Knechtle’s review consists mostly of studies conducted in regions where the activity is regularly practised, notably Northern and Eastern European countries.

The techniques used to determine the impact swimming has on health include clinical tests such as blood sample analysis, temperature mea surements, and blood pressure measurements, often comparing the results to those of a control group. Impacts on mental health are traced by methods such as interviews and questionnaires before and after a swimming period, recording of symptom frequency and severity blood analyses. Despite the difficulties of designing an ideal study (for

example controlling for swimming distance, water temperature, and time spent immersed), the majority of studies confirm the informal accounts: outdoor swimming has the potential to positively affect our health.

However, Knechtle’s review is equally interested in the risks posed by cold water swimming, especially hypothermia. According to exercise physiology a human immersed in 0°C water is expected to survive just 30 minutes. Novice swimmers could overestimate their abilities and fail to react before they get exhausted or begin to lose consciousness. In such cases, as Knecthle observes, it is cardiac stress that may lead to death and not hypothermia itself.

investigated outdoor swimmers’ perceptions of their health and the extent to which outdoor swimming impacts their symptoms. Their findings demonstrate that the participants largely perceive swimming improves their health. Specifically, they reported a significantly reduced appearance of cardiovascular and circulatory symptoms, musculoskeletal injury, as well as mental health conditions.

The reaction to the first cold shock and exhaustion are considered the main factors which may lead to drowning. The World Health Organisation lists drowning as the third leading cause of unintentional fatal injury worldwide. Lack of swimming skill and knowledge is largely behind this number, as far fewer accidents involve seasoned swimmers.

A study spearheaded by Professor

Why We Swim is Bonnie Tsui’s treatise and love letter to swimming and the open waters. The author, journalist, and veteran open water swimmer, dedicates a full section of her book to the physical impact of swimming. Tsui discusses work done at a laboratory at the University of Texas, investigating high blood pressure and arthritis. Those scientists found that the effects swimming has on these conditions surpass those from other types of aerobic exercise. As Tsui further explains, following immersion blood circulation moves away from the extremities and towards the heart and lungs, making them work harder and at the same time building their endurance. This exercise results in lower blood pressure in the long run.

The same lab didn’t hesitate to exalt swimming particularly in cold water as an arthritis treatment. Exercising in the water is smoother for people suffering from the condition as the strain on joints is reduced. It minimises pain and, ultimately, stimulates mobility and function. This explains why it is also as a form of physiotherapy

features

24 Autumn 2022 | eusci.org.uk

“The idea of water as cure is far from new.”

Image by Pexels courtesy of Pizabay

attack that left him shocked and numb. Two years later, a motorcycle accident resulted in a shattered ankle that would require three operations over the following months. Ventura could only walk with crutches. In a short time, his life had drastically changed, and he was convinced it would only continue to worsen.

The cardiologist who treated Ventura after the ischemic attack suggested he start doing some form of aerobic exercise. Until that moment, Ventura had a good relationship with water, having been a windsurfer in the past, but he never took swimming classes or thought of himself as a swimmer.

“Two months after my accident, I went in the water again. I had spent several days bed ridden and then I could only hobble for a little while using crutches. Imagine someone who can barely move and then gets in the sea and can glide easily in the water with grace. I was beyond emotional! I promised myself right there and then that in one year’s time, I was going to participate in an open water race, and I didn’t give up.”

breathing coupled with the connection with nature engender a unique relaxation of the mind and concurrent exaltation of the soul.

spaces”. However, a range of studies using indicators including self esteem, fulfilment, resilience, (social) confidence, connectedness, stress, and mood, confirm that when it comes to mental wellbeing, swimming can be therapeutic.

In addition to overcoming trauma, it is widely believed that aquatic exercise offers opportunities for specific populations that may be otherwise challenged to exercise on land. Ethel Kotzamani is a swimming instructor that works with people of all ages, including disabled and neurodivergent persons. “In the water, everybody is equal,” she says. “It is simply powerful to watch my students participate in open water competitions and they are also thrilled, glowing with the excitement of fulfilment. Hydrostatic pressure is instrumental when dealing with several types of conditions. People become autonomous and their quality

“I will never forget the indescribable emotions that came with completing the race”, remembers Ventura. “My goal was simply to finish but I achieved a good ranking, too. I felt that I existed again, that I wasn’t ‘perished’. Now I’m always giddy with anticipation before entering the water. It’s the only space I can be alone with myself, and I gain physical and mental exhilaration.”

Most swimmers are simply convinced that the activity boosts their energy, ameliorates possible ailments, and enhances their overall health, both physical and mental. There may be some way to go in terms of research, but the emerging scientific data point the same way: take up swimming and do it regularly.

Alkisti Kallinikou (she/her) is a writer and aspiring journalist. She is also interested in science communication.

Autumn 2022 | eusci.org.uk 25

“The effects swimming has on these conditions surpass those from other types of aerobic exercise.”

Image by Martín Saenz courtesy of Unsplash

Remembering

Eunice Newton Foote: the unrecognised climate change pioneer

By examining the life and work of Eunice Newton Foote, Alice Drinkwater allows an unknown scientist to be remembered and questions what would have happened had she had more recognition at the time.

Climate change is usually seen as a modern issue with our understanding growing as the impact of carbon emissions becomes clear. However, the truth is that the heating power of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was first demonstrated (and its future impacts predicted) by a female amateur scientist as early as the 1850s. Her research was ignored and rejected, but time is seeing her vindicated.

Eunice Newton Foote was born as Eunice Newton in Connecticut, USA, in 1819. Her father, Isaac, was a farmer and a distant relative of Isaac Newton, while her mother, Thirza, was a homemaker. Both strongly believed in the importance of educating their children regardless of gender.

At the time, expectations were rigid around a woman’s behaviour in society. An influential factor on Eunice’s growth (both intellectual and social) was her education she was encouraged by her teachers at Troy Female Seminary to pursue science, attending biology and chemistry lectures at her local college. Eunice stayed up to date with scientific literature and performed amateur experiments throughout her life. She married Elisha Foote, a judge, in 1841. The two seem to have been a good match he too was an amateur scientist and inventor.

Legally, women were considered inferior to men, with no voting rights, limited property rights, and little access to further education. When