SciencEd

www.eusci.org.uk | FREE

THINCERT® 96 WELL HTS INSERT

For high-throughput transport studies and co-cultures

The new ThinCert® 96 well HTS insert is the optimal tool for scientists who want to generate tissue models (e.g. endothelia and epithelia) for transport, uptake, or co-culture studies in submersed as well as air-lift cultures with an automation-friendly format

KEY FACTS

Optimal for transport and permeability studies, air-lift cultures, co-cultures, and toxicity screening

96 well system for highthroughput applications

Automation-friendly design

Transparent polycarbonate membrane with 0.4 µm pore size

Reduced wicking effect*

High membrane flatness for reproducible cell culture conditions

Greiner Bio-One Ltd Stonehouse, Gloucestershire, UK PHONE 01453 825255 / E-MAIL info@uk gbo com Greiner Bio-One is a global player Find the contact details of your local partner on our website * Wicking: Undesired formation of a liquid bridge between upper and lower compartment due to capillary forces within the narrow space between membrane and receiver plate

FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE OR CONTACT US:

www.gbo.com info.uk@gbo.com

/ / / /

/ /

AUTOMATION MADE EASY STERILE FREE OF detectable human DNA FREE OF detectable RNase noncytotoxic nonpyrogenic FREE OF detectable DNase Check out our podcast series . . . www.gbo.com

Inside this issue

The scientific community is becoming increasingly more multicultural, diverse and inclusive. Efforts are being made by large academic institutions, science outreach organisations, and individual scientists to acknowledge the need for diversification and equity in all areas of research and science communication Scientists are more present in everyday life, sharing their knowledge with the world and can (and should) be important active participants in governmental and societal decisions In this issue we take a closer look at the challenges scientists face today and the roles they have in society: How is scientific research influenced by political, cultural, and social pressures? How far are we really in creating an inclusive and unbiased environment in research and education? How do we relate with the public to promote their curiosity and engagement with scientific content, and how much consideration is given to their perspective?

Alotofquestionstobeasked!Webelieveweallhavethepowertocontinuously makesciencemoreaccessibletoeveryoneandthatthisisimportantforhow muchweunderstandourselvesandtheworldaroundusWeinviteyoutoreflect ontheseissueswithus–maybeyouwillfindanswerstosomeofthesequestions orgetcurioustoaskevenmoreEnjoy!

SaraTeles(she/her)andElenaHein(she/her)–co-editors-in-chiefofEUSci

HowinclusiveistheUniversityofEdinburgh?FromtheEdinburghSeventoDecolonisation

NurturingInclusivityinPhysics:AjourneywithTheBlackettLabFamily

APlaceforEveryone:Howpromotingscienceandlanguageliteracycanhelpreduceinequalities

BreakingBarriers:TheRoleofsciencefestivalsinfosteringinclusivity

“Sexy”Science:Sciencebythedefaultwhitemale

QueerDatawithDr KevinGuyan

Bringinghumanityandhumourtosciencewriting

I’manAcademic…Getmeoutofhere?!

Tofundornottofund–Howmuchshouldthepublicholdthestrings? Exploringtheinterdependencebetweenpoliticsandscience

Thechillsetsin

Ascientistwalksintoabar

EmbarkingonCitizenScience:Anintroductorydive

HomeDiagnosticsandHealthMonitoring:Arisingtrendin2024

Biohacking:fromfeartofascination

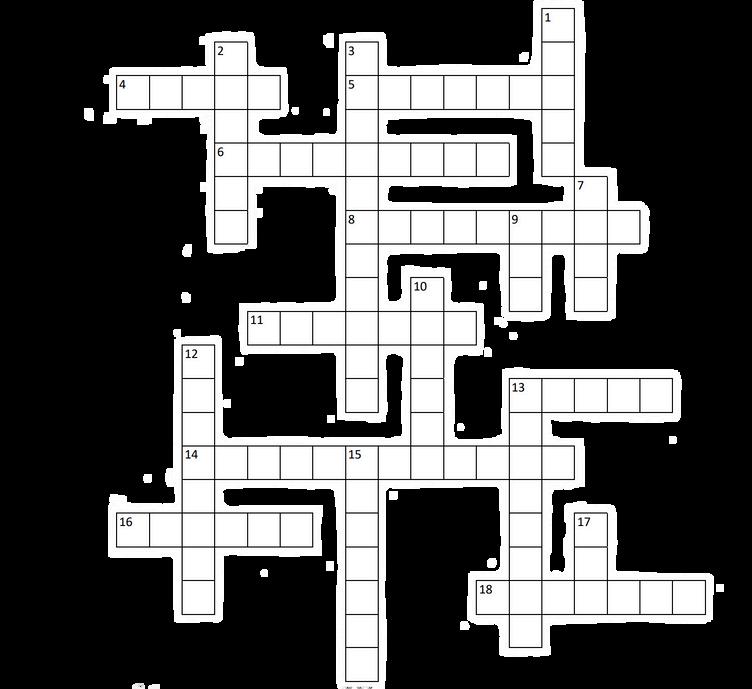

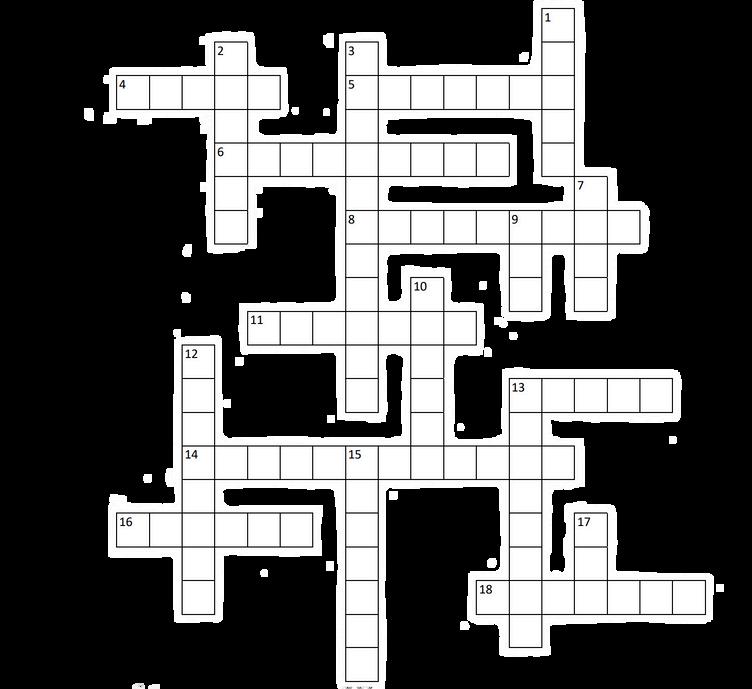

Puzzles and games

Meet EUSci

Spring 2024 Coverillustrationby EwaOzga Prefertolisten?Checkoutaudioversions ontheEUSciReadoutsPodcast

SciencEd Issue 32

Euscireka! 04 The Scientist Next Door Diversity, equity, and the “human struggles” in scientific research 07 10 12 14 17 19 22 24 Science outside of the lab: exploring the intricate web of science, politics, and the role of the public in the “conversation” 27 30 33 35 37 39 42 44 45 A collection of short news articles

euscireka! euscireka!

Pulling tropical disease out of neglect into acknowledgement

The World Health organization (WHO), officially added Noma as its 21st disease into the list of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) in December 2023 Noma is a severe gangrenous disease caused primarily due to poor oral hygiene by the bacteria living in our mouths It primarily impacts children, and patients often face stigmatisation The committee responsible for this addition concurred that the decision to include Noma in the list of NTDs enables the accessibility of better interventions in communities that require it. This sentiment is in line with the Sustainable Development Goal 3 3 established by WHO, which explicitly aims to ‘end the epidemics’ of neglected diseases which impacted 1 65 billion individuals in 2021 The overarching target for 2030 was set to a 90% reduction in people requiring interventions for NTDs Although the progress towards this ambitious target has been positive, it has also been slow For instance, in an official report published in January 2024, it was revealed that 50 countries have eliminated at least one NTD and there has been 23% overall reduction in NTD-related interventions required by people The eradication of NTDs is further encumbered by climate change The regions of transmission for several vector-borne NTDs have expanded since the rising temperatures allow these vectors to survive in temperate regions According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control , in 2023 there were locally acquired cases of dengue fever in Europe: 82 cases in Italy, 43 cases in France and 3 cases in Spain The widening of transmission zones of vectors opens new populations to the risk of disease transmission Hence, while the roadmap was clearly written in ink, the actual route is long one to traverse

How humans struggle to define their own role on earth

Humans have had an immense impact on the planet since we started to settle down, grow large-scale agriculture and turned to mass industrialisation and warfare We have managed (or at least tried) to put a stamp of human existence on almost every reachable corner of the planet (and beyond) – yet the ultimate label has just slipped through our hands. Earlier this spring geologists voted against the proposal of recognising the Anthropocene as an official geological epoch This would have pushed us from the Holocene into a completely new era of ‘irreversible human impacts on the planet’ Undeniably - looking at recent human history and watching current news of political tensions, deforestation and climate change - it feels like we are living in a world that is irreversibly dominated by our actions and desire to expand our control over everything we can get our hands on But is this enough to leave such deep marks on earth’s rocks for these to define an entire new geological age?

The rejected proposal set the start of the Anthropocene in 1952, referring to the first traces from hydrogenbomb tests being deposited in sediment But critics are pointing to the thousands of years of agriculture and elimination of native fauna and flora that have been happening since the start of human existence and would be completely ignored by this time scale And what about the vast amount of records on microplastic, pesticides, fossil fuel production and other pollutants that we have been mindlessly dumping into our planet’s land- and seascapes? For some, defining our human footprint down to a single point in time and place may seem too drastic to describe the global change that we have brought upon earth’s history For others it is crucial to accept it Nevertheless, acknowledging the cultural concept and impact of the Anthropocene can and should be a reminder of the tight-knit relationship between all living things and nature on our planet. Rather than trying to put a definition and label on everything we might be good to just accept that in the end it is still nature which holds the strings to its own geological history – and we might do good to be a respectful partner in it

Elena Hein

Simar Mann

4 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

Jellyfish in robotic hats to do deep sea research

It’sextremelydifficultforresearchtechnologiestowithstandtheharshconditionsoftheworld’sdeepoceans But the climate crisis is accelerating, and it is more crucial than ever to develop innovative tools that allow scientiststostudytheseas Theanswer:jellyfish

ResearchersatCaltechhaverecentlydevelopedsmall3D-printed‘forebodies’thatattach–likelittlehats–to common Aurelia jellyfish The hats contain an electronic pacemaker that controls the way that the jellyfish swim.Researchershopethatthistechnologywillsoonallowthemtogatherscientificdatafrommanyareasof theoceanthathavenotyetbeenexplored Theresearcherscollaboratedwithbioethiciststoensurethatthis workisethicallyprincipled Aureliajellyfishhavenobrains,norcantheyfeelanypain,andnostressresponses havebeenrecordedatanypointduringtesting Thehatsaredesignedtohavenegligiblebuoyancyinsaltwater sothattheyaddnoadditionalweighttothejellyfish Infact,thehatsmakethemmorestreamlineandjellyfish swim up to 45 times faster with the hats on There is room in the hats where scientists can fit sensors that measure ocean temperature, depth, light, motion, salinity, oxygen, and pH Further work will be necessary to make such sensors small enough to fit inside. These robotic jellyfish hats are an exciting cost-effective innovation(atonly$20perhat)thatwillmakeEarth’svastoceansmoreaccessibleforscientificstudy

ClareMcDonald

An equity lens for medical devices

Ever since the acceleration of AI and technological design in medicine, and especially since the Covid-19 pandemic, the use and availability of AI-powered medical devices has been increasingly popular. Such tools that leave measurements and interpretation of results to an objective computer-driven machine should ultimately be less biased in their output than a subjective human being – but are they really?

We already know that AI is not immune to human bias A bias unavoidably stemming from the humans who developed it and the samples they’ve been trained on A recent independent UK review has now also confirmed such biases in medical tools such as pulse oximeters, which were crucial in testing oxygen levels during the Covid-19 pandemic, spirometers to measure lung function, and other AI-based devices such as cardiac monitors. Relatively unsurprisingly, these tools are frequently based on datasets of people with European ancestry, from well developed areas and/or male individuals This makes them most often not applicable to people of other ethnic ancestries, deprived backgrounds, or other genders The first step to improve the access to appropriate health care is to acknowledge the potential of biases inherent in these devices Though, trying to fix these often comes with biases itself

Ultimately, researchers and doctors are calling for “an equity lens” on such medical tools and AI-powered clinical devices, looking at their entire lifecycle - from development and initial testing to patient recruitment and implementation in communities In the end, an individual’s diagnoses and treatments should not be determined by whoever developed the medical device and the biological parameters of whoever it has been tested on but to be as objective as possible to ensure access to appropriate health care for everyone, regardless of their ethnicity and socioeconomic status

Elena Hein

5 Spring 2024| eusci org uk

euscireka!

euscireka!

The Scientist Next Door

6 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

IIlustration by Stevie Hope

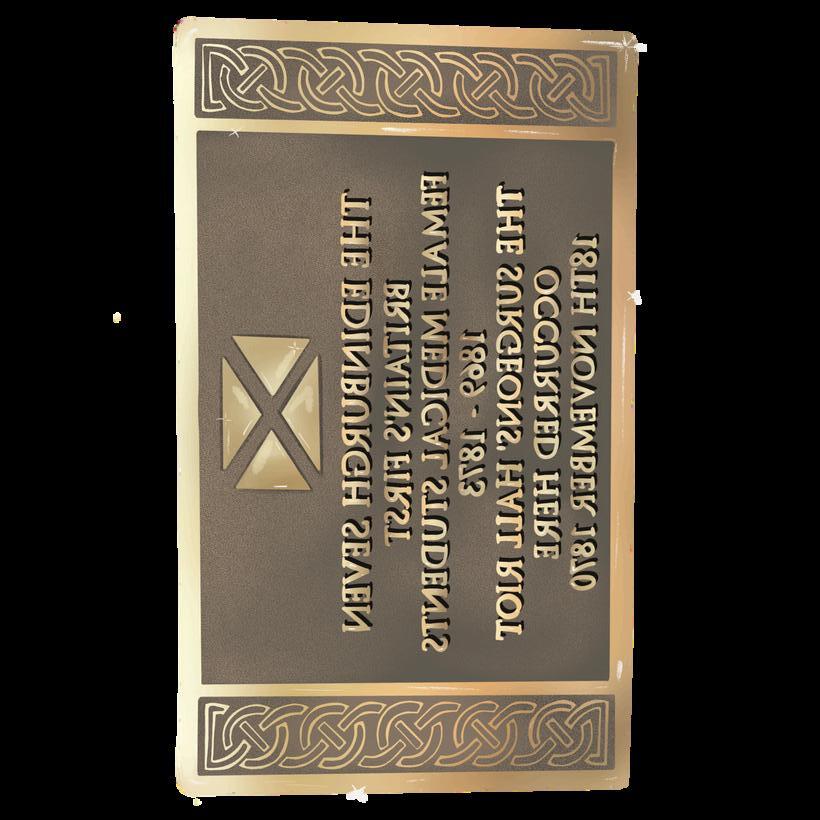

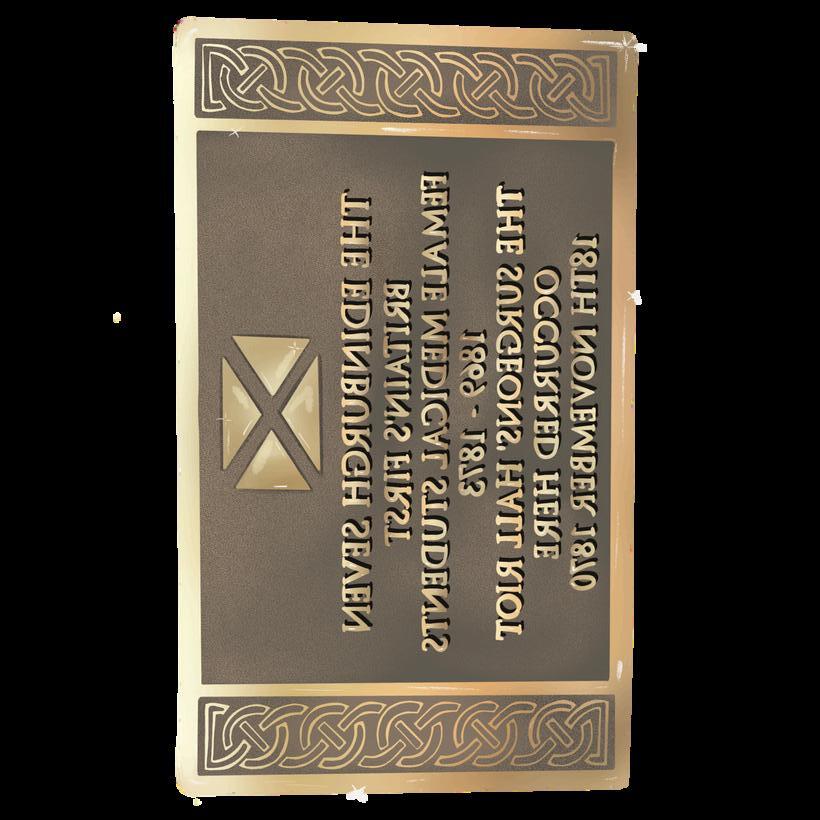

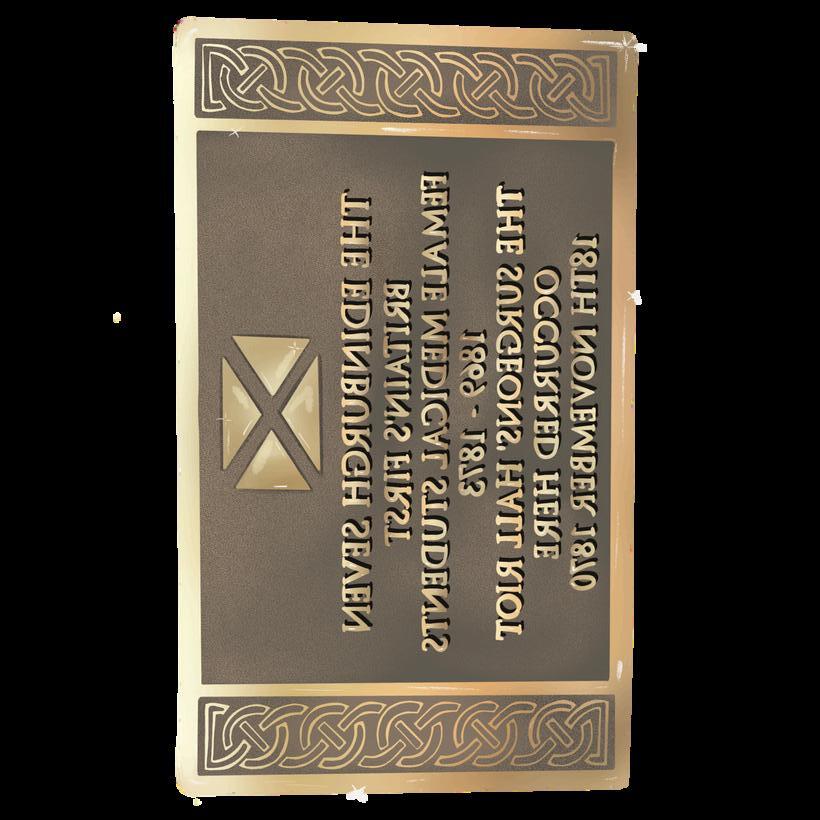

How inclusive is the University of Edinburgh? From the Edinburgh Seven to Decolonisation

Ellie Dempsey delves into the historical struggles and current challenges of promoting equality in science at the University of Edinburgh atives and co n.

The University history in the fight for equality in the sciences In1869,SophiaJex-Blakeledseven

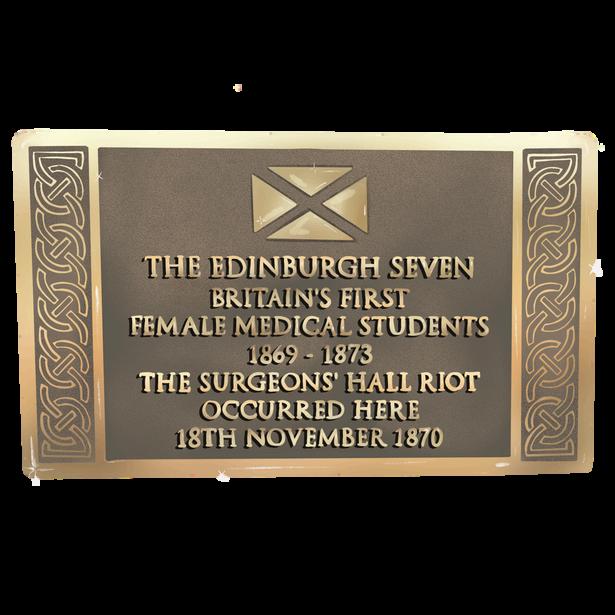

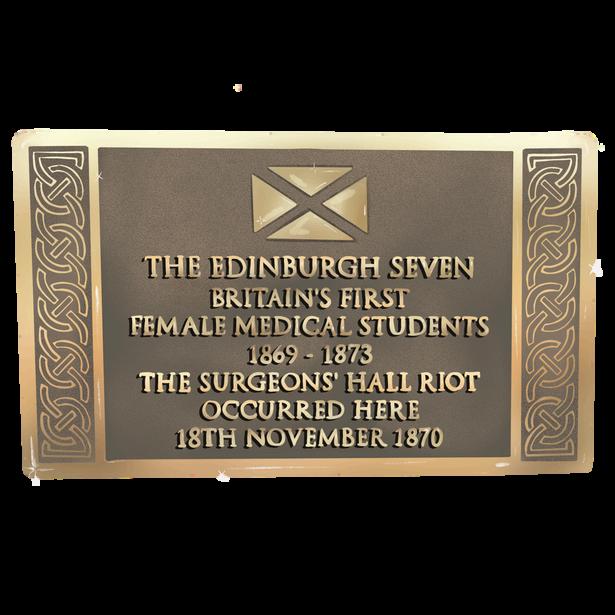

A rendering of the Historic Scotland commemorative plaque to the Edinburgh Seven and the Surgeons' Hall riot at the University of Edinburgh by Allison Quinlan

women to enrol as medical students In doing so, they became the first-ever women to attend a British university Despite outshining many of the male students intellectually, the Edinburgh seven were forced to pay significantly higher fees, faced mounting abuse from fellow students and staff, and were never permitted to graduate. Their struggle, however, drew national support and launched a campaign culminating in the Medical Act of 1876, allowing women to qualify as licensed medical practitioners for the first time Looking at the picture today, where women make up 61% of Edinburgh’s medicine admissions, it is difficult to imagine the environment of 150 years ago However, there is still much progress to be made promoting equality, diversity, and inclusion, with manyscientistsstillfightingagainstinequality

h remains a centre for excellentscientificresearchandprogress,itfallsbehind other institutions when looking at admissions of ethnic minorities and people from lower-income backgrounds In 2022, only 14% of UK undergraduate entrants were from minority ethnicities compared to 27% nationally Looking at black British students, this disparity widens as they make up only 1 5% of entrants to Edinburgh compared to 9% nationally Edinburgh also has a longheld reputation as a home for the economic elite. In fact, the University ranks 4th in the UK for the number of admissions from private schools In addition, in spite of Edinburgh being the capital of Scotland, Scottish students make up only 26% of the student population at the University of Edinburgh despite comprising 60% of the national student population in Scotland. The idea of the upper-class English, white, Edinburgh student has almost become a running joke around the city However, it leaves many students outside of this group feeling isolatedandunderrepresented

The Scientist Next Door

7 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

“It is harder to truly see yourself as a scientist when the majority of professors and those in leadership positions are so different to yourself.”

A full analysis of why these inequalities exist is too complex to cover in a single article, with the problem lying deeper than straightforward discrimination or harassment Today’s situation is also closely intertwined with Edinburgh’s historical links to colonialism and slavery, which groups across Edinburgh and the University are working to address From a more individual perspective, a sense of isolation, imposter syndrome, and the strain of living in such an expensive city are a common thread in many student experiences It is harder to truly see yourself as a scientist when the majority of professors and those in leadership positions are so different to yourself The accompanying mental health impacts of these issues are particularly heightened amongst students who don’t see themselves represented or supported Furthermore, feedback from students across the board frequently highlights a lack of mental health and wellbeing support, with the University scoring a relatively low 60 % for signposting of support services in the latest national student survey Although improvement in this area is slow to take shape, the University’s investment in a new Wellbeing serviceisasignificantstepforwards

A more direct response to educational inequalities has come from many student-staff led networks and societies who have emerged over the years For example, the student-led women in STEM society (EUWiSTEM) founded a successful mentoring scheme whichenablesstudentsatdifferentacademiclevelsto

support each other Another group who should be acknowledged is the RACE.ED network – a collection of academics from different disciplines - who share research and teaching practice on racial equality and decolonisation When it comes to tackling social inequality, the Edinburgh branch of 93% club has held events on accent bias and is currently campaigning to include class awareness in University anti-bias training Organisations such as these are invaluable in promoting research, building connections and spreading awareness of equality issues, independent from the bureaucracy and politicsofUniversitymanagement.

Despite a desperate need for change, many positive initiatives such as those on trans inclusion and decolonisation have faced public backlash and derision with efforts for progress becoming derailed in culture wars. There is also a general perception amongst students that the University does not deliver on its promises and broad equality statements are rarely backed up with real change Advances in higher University management are slow, however, there are many people within schools who devote time and effort to improving equality I discussed this with Dr Claire Hobday, Chair of the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion committee in the School of Chemistry Although she agreed broader change was slow, she was positive about the commitment shown by school and college leadership towardsimprovement

The Scientist Next Door

8 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

Within the School of Chemistry, Claire highlighted some of the recent progress made on improving building accessibility, collecting data on PhD applications, a trial of equity training for students, and events which support a sense of community and belonging She also emphasised the importance of staff and student involvement to drive initiatives within their own school Despite time limitations for academics to commit to equality initiatives, it is important that change is informed by real understanding of the school environment Therefore, the time and effort staff spend on equality, diversity and inclusion should be properly valued by institutions One exciting project Claire is overseeing is funded by the Royal Society of Chemistry’s ‘Missing Elements’ grant, worth £60,000, to address racial inequality in Chemistry This funding will enable further equity training, a mentorship scheme and a summer research internship for students from ethnicminorities

Building on the efforts within the School of Chemistry, the University is also actively engaged in various widening participation and access programs, such as the LEAPs program and Door’s Open Days, inviting the public to explore science buildings and fostering community engagement Many students I know have given up their time to demonstrate fun experiments to children at an open day or volunteer on a trip to a school The School of Chemistry even offers a Public Engagement scholarship to which funds a PhD student to commit time to outreach and engagement projects alongside their research Despite these efforts, the number of admissions to

working in scientific research today without the mentorship and widening participation programmes I had access to growing up It is therefore vital we continue to invest in and expand opportunities to pave the way for more diverse future generations of scientistsattheUniversityofEdinburgh

The subject of imposter syndrome also came up in discussions with Claire and other women in STEM. Whilst efforts targeted towards minority groups and representation undoubtedly have a positive impact, many of us have also experienced a paranoia that we have only found our opportunities through filling q otas or so called ‘tokenism’ It is also common to

The Scientist Next Door

9 Spring2024|eusci.org.uk

Nurturing Inclusivity in Physics: A journey with The Blackett Lab Family

Kaela Albert explores the efforts of organisations like the Blackett Lab Family in fostering a sense of belonging for underrepresented groups and in ensuring that science is accessible to everyone.

Despite our best efforts for purity and facts, science is not removable from society. It mirrors society's beliefs, adapting and transforming alongsideouraspirationsandbiases Theinputwe

give artificial intelligence (AI), the training we provide doctors, the funding we give to different research groups –these all have massive impacts on the progression of science.

This interdependence between science and society has led to a compelling call for increased inclusivity and diversity in STEM The call serves to counteract deeply ingrained biases in science – biases that have historically marginalised certain groups based on race, class, disability, and more. There are several reasons to argue for inclusivity and diversity in science – inclusivity has improved team productivity and led to innovative ideas. How fundamental reason to advance inclusivity shouldbeaccessibletoeveryone

One group committed to increasing and maintaining this inclusivity is The Blackett Lab Family (BLF) BLF, founded in 2020 by Dr Mark Richards, has a mission to represent, connect, a nd inspire Black physicists. This is an admirable goal, considering data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency shows that roughly just 1% of UK-domiciled physics undergraduates are Black To put this into perspective, Black people comprise 4% of the UK's working-age population and 8% of its science undergraduates. Furthermore, the number of Black physicists decreases with seniority, with no Black physics professors in the UK This is a remarkably low statistic but

deas o e e , ost fundamental ason to advance y is that science be accessible to

The Scientist Next Door

beyond students to include parents, early career researchers, and the broader Black community All of these groups have unique challenges and require focused and comprehensive support systems.

Reflecting on personal experiences, Benyam sheds light on the challenges he faced with assimilation as an undergraduate From code-switching to hair discrimination and elusive skiing holidays, the struggle to assimilate for Black students in a predominately white field is real For Benyam, feeling isolated and opening up about personal challenges seemed daunting before connecting with Black physics mentors Dr Mark Richards and Paul Brown at Imperial College London While Benyam was fortunate tofindsupport,heacknowledgesthatthismightnot

“Competency without a sense of belonging is not enough. Black udents need to be given the opportunity to see emselves as physicists, which is exactly what presenting Physics 2023 gave.”

story for many Black students nationwide This ve underscores the importance of breaking arriers to effective mentorship

relatively short time that Benyam has been f the scientific community, he reports a able amplification of discussions around ty and inclusivity This heightened awareness es a positive shift where individuals, initiatives, oups advocating for inclusivity are becoming visible The Blackett Lab Family is a testament power of collective endeavours in promoting bility and fair representation in STEM. More are constantly popping up that campaign for alised groups and aim to foster open vations Some for you to keep an eye out for e:

ck in Cancer

ck British Academics

Black Tech

e Black Women in Science Network ding Routes

These organisations allow Black scientists to see themselves, and as Benyan says, " a sense of belonging is a self-perpetuating power!"

Kaela Albert (she/her) is a fifth-year MPhys

Theoretical Physics student at the University of Edinburgh

The Scientist Next Door

11 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

A Place for Everyone: using science communication to promote inclusivity

Sara Teles shares Native Scientists’ approach to promote children’s science literacy and a more inclusive community

The path to become a scientist in academia can feel like going through a never-ending darktunnel,withnocertainendinsightand

nobody there to confirm if you are on the right track

The past ten years as a junior researcher (notice the resistance in calling myself a scientist) were marked by a constant feeling of not belonging Although this is seemingly a universal experience in academia, there are various factors that intensify those feelings As addressed in other articles of this magazine, people’s social, cultural, and economic background can make them more vulnerable to experiencing “otherness” – if you grow up without examples of a scientist that looks like you, it will be harder to see yourself becoming one. Similarly, when you encounter people that do not believe in you or that make you feel inferior during your scientific journey (and most likely you will), it can be incredibly hard to counter those beliefs with sheer selfdetermination when you neither had nor currently have an example of someone like you “making it ” It is important to make science more welcoming and continuously more accessible to everyone, cultivatingasenseofbelongingearlyon

Organisations such as the Edinburgh Science Foundation are committed to improving science accessibility by inspiring students in Scotland to engage with STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) in hands-on activities and events where students are given an insight into different scientific careers With over 30% of its programme delivered free of charge and the remaining schools being offered subsidised visits, they make an effort to reduce the geographic and economic disadvantage of many children in accessing engaging science communication But science outreach should be broadened to address a wide range of factors which intensify this lack of access, such as having a disability or belonging to an ethnic minority group

Native Scientists was created in 2013 to “broaden the horizons of underserved children, by connecting them with scientists and promote science literacy and higher education ” Joana Moscoso and Tatiana Correia were two Portuguese researchers working in London when they became aware that children from migrant families performed worse at school. Indeed, in Lambeth, one of the most diverse boroughs of London, Portuguese pupils have had the lowest academic achievement of all student groups in the council, as published in their 2020 report Factors

such as stereotyping, exclusion, lack of awareness to Portuguese culture, and inadequa-

cy of the programme to reflect a multi-ethnic society were identified as relevant in the under-achievement of these children

The Scientist Next Door

12 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

A collage made from a photo by Power Lai, Unplash

Studies published by UNESCO and the European Commission have confirmed that migrant children are at an increased risk of developing low self-esteem and underperforming in STEM subjects This is one of the issues that Native Scientists addresses with their “Same Migrant Community” programme, by promoting the interaction between scientists and children that share the same heritage language across Europe Scientists go to local schools with a 15-minute activity to introduce their work and talk about their career path

“It is important to make science more welcoming and continuously more accessible to everyone, cultivating a sense of belonging early on.”

Following a “Science Tapas” concept, children are divided into groups and interact with several scientists in a single workshop As pointed out in their 2022 article published in the journal Trends in Cell Biology, this strategy is built on EDI values (Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion) The students and scientists establish a meaningful connection through a shared cultural background that boosts the development of their heritage language while offering a role model and inspiring scientific curiosity. In the 2024 Science Education article, Julia Schiefer describes this as a new Science and Heritage Language Integrated Learning (SHLIL) approach The authors show that this is effective in promoting the children’s engagement with STEM subjects and their self-concept of ability for the heritage language for at least four weeks after the interaction As the programme lead Afonso Bento shared with me, the objective of these interactions is not necessarily to incentivise children to become scientists but to promote curiosity and interest in science while raising the value they associate with their multicultural identity Afonso mentioned that many students associate the use of their heritage language with doing chores at home The interaction with scientists who speak the same language makes them see it for the first time as a useful tool they can potentially use in the future

Science communication is increasingly considered a key skill that all scientists should master for multiple reasons, including captivating the next generation of researchers. But science literacy needs to be considered important for the general development of every child without needing it to become all about job recruitment Interactions such as the ones created by Native Scientists foster curiosity and can be used to cultivate a sense of belonging and understanding of oneself and of others This approach can be a powerful educational tool for the schools of the future with increasingly multi-ethnic and diverse student populations Moreover, this could have an important overall social impact – Afonso pointed out that Native Scientists is particularly innovative in the way that they not only train effective science communicators but are also training community organisers. In fact, Afonso was the first author in a 2023 article in Frontiers in Communications that described how many of the scientists volunteering to coordinate the workshops had a societal motivation, viewing the impact of these interactions in bridging society and science as one of the driving forces behind their participation Strategies such as the “Same Migrant Community” programme should be considered by governments and institutions as not only an effective educational tool that improves the attainment of multicultural student groups but also as a powerful societal initiative that contributes to more inclusive and equal communities

Sara Teles (she/her) is a biologist and cancer researcher, currently finishing a PhD in bile duct cancer at the University of Edinburgh She is a co-Editor-in-Chief of EUSci

The Scientist Next Door

13 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

TBreaking Barriers:

He pot fes by Edinburgh Science as an example of how public engagement projects can support inclusivity in science.

In the pursuit of knowledge and progress, fostering inclusivity within science is paramount However, this

requires intentional efforts to create welcoming environments and opportunities for individuals from diverse backgrounds A great example of this is through community engagement, such as science festivals. Public science festivals present the opportunity to make science more inclusive by engaging diverse communities in a celebration of knowledge and discovery These festivals provide accessible platforms for scientists to communicate their research directly to the public, fostering a two-way dialogue that demystifies scientific concepts

With a range of interactive exhibits, engaging demonstrations, and hands-on workshops, science festivals can appeal to a broad audience of all ages and backgrounds, including individuals who may not typically have exposure to formal science education This inclusivity not only promotes scientific literacy but also encourages individuals from underrepresented groups to envision themselves as active participants in the scientific community, thus contributing to a more diverse and equitable future inthefield.

In fact, a growing body of research indicates that supporting inclusivityinsciencehasbenefits

hfor us all Research supports the benefits of inclusivity in science, as diverse teams offer varied perspectives and innovative problem-solving approaches

Additionally, studies conducted on individuals in the USA show that diversity helps prevent groupthink, a psychological phenomenon where group members prioritise harmony and conformity over critical thinking, leading to flawed decision-making

More research may be needed to see whether these results generalise to other cultural contexts outside of the USA. Other studies have shown that for many people, participating in science festivals in particular leads to increasedknowledge,inspiration,

The Scientist Next Door

s

14 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

Illustration by Muminah Koleoso

and a positive impact on their attitudes towards science. Indeed, these festivals play a crucial role in enhancing public understanding of science, fostering trust, and contributing to a more scientifically literate society Science festivals have great potential to reach diverse audiences across large geographical areas, offering science exploration for everyone by creating interactive, accessible, and enjoyable experiences that contribute to a more informed and engagedpublic

While research on science festivals often highlights the positive aspects of public engagement, concerns about inclusivity have been raised For example, reaching certain demographic groups, such as those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, may be a challenge. Some research suggests that attendees of science festivals may skew towards more affluent and educated demographics Therefore, although science festivals play a valuable role in science communication, ongoing efforts are needed to ensure that they are accessible and appealing to a broad spectrum of society, addressing potential barriers related to socio-economic status andotherfactors

Some science festivals are actively breaching this gap in audience diversity to ensure science is accessible to all. For instance, the Edinburgh Science Festival, recognised as the first-ever public event celebrating science and technologyonafestivalscaleand still one of Europe's largest, adopts various strategies to broaden its reach These include providing complimentary tickets, specialised events, and even transportation in areas with high levels of deprivation according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation(SIMD)

“Science festivals have great potential to reach diverse audiences across large geographical areas, offering science exploration for everyone by creating interactive, accessible, and enjoyable experiences that contribute to a more informed and engaged public.”

SIMD is an area-based measure of relative deprivation which takes into account various factors such as health, access to services, and education levels within the community Furthermore, in 2022 the festival hosted over 600 children and young people across the city and offered free workshops to 451 pupils from high SIMD schools at the City Art Centre The festival collaborates with community groups like With Kids, One Parent Families Scotland, and SCORE Scotland to ensure tailored support for attendees facing accessibility challenges With Kids offer various therapeutic services for children, carers, and professionals working with children in Edinburgh and Glasgow One Parent Families Scotland aims to support single-parent families and facilitate a better standard of living by offering face-to-face support services and online information, while SCORE Scotland is a charity which addresses the causes and effects of racism and promotes racial equality The accommodations Edinburgh Science offered after consultation with these groups ranged from free festival tickets and public transport to on-site assistance and a specialised event timetable In addition, an accessibility guide is available for download prior to the festival each year. This outlines useful accessibility information including the locations of accessible toilets, relaxed sensory-friendly events, and public transport recommendations

Beyond their science festival, Edinburgh Science is involved in the community year round. This includes working with local centres and organisations to break down barriers and create more opportunities for everyone to engage with science For example, in 2019 they developed a health, wellbeing,andnutritionworkshop

The Scientist Next Door

15 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

called The Great Plate Other efforts include Generation Science, an inspiring and interactive science workshop which has been touring schools all over Scotland for 30 years During the Covid-19 pandemic (and despite its challenges), this was moved online where they posted resources such as pre-recorded workshops designed to engage pupils Additionally, Edinburgh Science offer an online careers event called Careers Hive This immersive career education event is designed to inspire high school students and increase awareness of the many potential career paths within STEM A deconstructed version of this career event, Beyond the Hive, has garnered positive feedback from young people, for example: “I liked learning about the different jobs, and that they are for everyone, not just certain ones for boys and others for girls,” and “That was the best day!” This event is aimed at 15–19 year olds not in education or employment, and it is broadening the horizons of young people in science.

Another project of theirs is the Sensory Seashore Scrapbook, a self-led trail exploring life on our coasts for all ages This resource is available for anyone to access on their website in four different languages including Ukrainian, Romanian, and Arabic Clearly, the work Edinburgh Science do to engage pupils and inspire the public is extensive and crucial. This ongoing work is essential to promote inclusivity in science and to highlight that science is for everyone

In conclusion, fostering inclusivity within scientific communities is paramount for enriching perspectives, fostering innovation, and ensuring equitable sharing of scientific progress. While significant strides have been made, ongoing efforts are crucial Recognising and addressing barriers, promoting diversity at all levels, and fostering a culture of inclusivity are essential steps By embra-

cing individuals from diverse backgrounds, including those historically underrepresented, scientific communities promote fairness, equal opportunity, and break down barriers. Furthermore, inclusive scientific communities are better equipped to tackle global challenges, as they bring together individuals with varied backgrounds, fostering collaborative problem-solving Ultimately, inclusivity not only serves as a moral imperative but also strengthens the scientific enterprise, making it more robust and capable of addressing the complexities of our interconnected world The journey towards greater inclusivity in science is an ongoing commitment that holds the promise of a more robust and responsive scientific landscape in the future.

Heather McEwan is a Biomedical Optics PhD student at the University of Edinburgh Her research is focused on using Raman spectroscopy to help transplant surgeons better assess liver health in the future

The Scientist Next Door

16 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

“Sexy” Science: Science by the default white male

Long afterward, Oedipus, old and blinded, walked the Roads. He smelled a familiar smell. It was the Sphinx.

Oedipus said, “I want to ask one question

Why didn’t I recognize my mother?”

“You gave the wrong answer,” said the Sphinx

“But that was what made everything possible,” said Oedipus “No,” she said. “When I asked, What walks on four legs in the morning, two at noon, and three in the evening, you answered, Man.

You didn’t say anything about woman ”

“When you say Man,” said Oedipus, “you include women too Everyone knows that ” She said, “That’s what you think.”

- Muriel Rukeyser

Anshika Gupta uncovers the shadows cast by [white] male driven research, detailing how convenient biases in research may perpetuate layers of gaps in scientific data and knowledge.

Believe it or not, science runs on trends, being policed by funders posing as the bully of the school If your researchdoesnotfollow

whatever the science journals are raving about or the fads that are makingthecirclesonsocialmedia,you are likely to not get funding for it That research topic which just got rejected is, to crudely say, just not “sexy” enough to make heads turn Trends may come and go but one thing about science that has stayed constant is men

Science since its birth has revolved around one thing: men and specifically men of a certain race They make up the largest fraction of science participants and apparent – and sometimes only – stakeholders Biological females make up approximately 50% of the world’s population but have been ignored when it comes to accounting for their needs and concerns This maleunless-otherwise-indicated research strategy has inconvenienced more than half the world’s population and sometimes these differences are not apparenttousatall

The Scientist Next Door

17 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

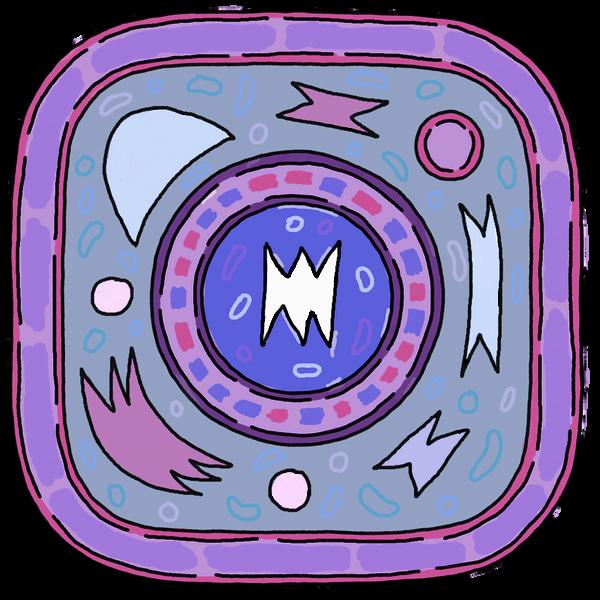

Illustration by Apple Chew

In the early 2010s Dr Tami made a shocking discovery that the time of day you have a heart attack affects your chances of survival So, if you had a heart attack in the day you had a greater chance of survival than at night This study was replicated several times and the same results were obtained till another publication of the same study in 2016 This new study by a new group of researchers detailed that daytime heart attacks triggered a greater neutrophil response, but this time it was correlated with a worse chance of survival There was just one difference between Dr Martino’s study and the new study, and it was that the latter used female mice while Dr Martino’s study and its subsequent replication used male ones Different sex led to completely different results There have been several attempts to address the sex issue when it comes to research, but the issue still remains and continues to skew results

It has been frequently mentioned that the female body is considered too complex, and there are a lot more factors to consider when researching it Factors such as hormones, menstrual cycle, reproductive plans, and so on So, often researchers just stick to using male samples, and in the animal world procuring males is cheaper But sex is just the basic layer of the various scientific blindspots that we have become accustomed to living with Several layers like race, living conditions, and lifestyle choices add to the complexityofthesituation One might argue that these blind spots are unintentional, and perhapsinmostcasestheyare One way to combat them is to see more representation in those who conduct the studies in the first place But it is not as easy as it sounds

In an interview with an established and well-renowned university professor who would like to remain anonymous, it was highlighted that women-driven research (where women carry out the research and/or are a subject of the said research) was less likely to get funding than its male-driven counterpart “There is less of an appetite to fund research surrounding the female body ” Same goes for promotions and positions of power Since there are already less women to begin with in most science-related subjects, the hostile work environment that comes with being in the minority leads to a very narrow bottleneck whichishardtoovercome

“Trends may come and go but one thing about science that has stayed constant is men. ”

Let's keep sex aside for a minute Different races and cultures due to years of geographical and availability differences have evolved to have different traits at the genetic level, so most medicines and research made by people of a certain race and only trialled on the people of a certain race can have different – even detrimental – effects on people of different races In a study titled “Systematic review and metaanalysis of ethnic differences in risks of adverse reactions to drugs used in cardiovascular medicine,”

the author Sarah E McDowell, along with her colleagues, found that, amongst other things, there was a three-times higher risk of angioedema (a condition referring to the sudden swelling in any part of the body accompanied with hives) as a reaction to cardiovascular drugs in black patients when compared to other races

Years of studies have expressed differences at genetic levels between different races and ethnicities, but little focus has been put on the discrepancies that exist within the pharmacological sector. Why do some races show a higher percentage of gluten allergy, or why are people of African or Mediterranean descent more susceptible to sickle-cell anaemia? It all boils down to genetic differences and lifestyle choices If something as basic as gluten can cause differences, who is to say that contraceptives, reproductive aids, or even cough syrups will not have different effects in different races? Whether these differences are big or small will only come to light when detailed research is conducted, and quality research will only come out when this hostile environment that we have created for the “others” becomes more relaxed and accepting. It is clear that certain races are better studied than others and that this is another gap thatneedstobecovered.

This [white] male default is the cause and the consequence of a sex- and race-driven data gap But closing this data gap is not going to fix all of our problems. That would require a lot of work but we have to startsomewhere

Anshika Gupta is a second-year Neuroscience student and a huge sci-fi nerd

The Scientist Next Door

18 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

Queer Data

with Dr kEvin guyan

The following text is a shortened and edited version of our chat with Kevin on season 6 episode 2 of “Not Another Science Podcast” – to listen to the full unedited version, please use the QR code!

Dr Kevin Guyan is a researcher at the University of Glasgow and author of the 2022 book Queer Data: Using Gender, Sex and Sexuality Data for Action, which explores the collection, analysis, and use of data around LGBTQ+ communities in the UK. Katie and Kelsey from EUSci’s podcast team met with Kevin to discuss his book and get his insight into the intersection between data and identity.

EUSci: You were involved in helping design the new questions on sexuality and trans status in the most recent Scottish census. What was the engagement process like and how were you involved in the design?

Kevin: I was working outside of a university, for an equality and diversity organisation based in London, and then in Edinburgh, and so for me, it was a geekish interest in the design process The Scottish census in particular was scrutinised at a very detailed level by a particular committee within the Scottish Parliament which took a real keen interest in the work of the national statistics agency in Scotland and in the design of questions around sex, sexual orientation, and trans status I think the National Records organisation also had stakeholder engagement sessions where they invited feedback and engagement from researchers, academics, and policymakers. In the context of Scotland, there's a fair amount of opportunities for engagement and participation Alongside these discussions there was also something called “sex and gender data working group”, established by the Scottish government to look at how public bodies in Scotland collect data about gender This was another source of opportunities for stakeholder engagement and input and ultimately created a briefing for public bodies on data collection about gender and sex

EUSci: I feel like a lot of LGBTQ+ identities are very fluid, can change over time and take on different meanings, but this is at odds with data being quantitative and often requiring very strict binaries. How difficult is it to incorporate these concepts when you’re collecting identity data?

Kevin: LGBTQ+ identities are interesting in that some aspects are definitely fluid or mutable, but some aspects aren't There are many LGBTQ+ people who have some fixed unchanging characteristics, and what's been interesting to see is how these splits within the larger LGBTQ+ umbrella have been demonstrated through some of our recent data collection exercises For example, there is a sense that the census does count people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, straight, or cisgender, but where it struggles is people who don't fit those neat categories and people who maybe are gender fluid, nonbinary, or don't have a clear sense on how they wish to identify In my writing, I look at how certain methods are sold to us as being inclusive but can sometimes only count parts of larger communities I think that looking at questions of sexuality, gender, and sex through the prism of particularly quantitative data opens up bigger conversations – is it possible to ever design a method, survey, or scientific approach that captures everyone? Or, even with our best intentions and design methods, are there always going to be some people who don't fit into this pre-designed system? I guess it's an ethical political decision to say when a method is good enough – are we saying that when 90, 95, or 99% of people are included, a method is good? Are we always going to settle for methods which are always going to exclude some people in their design?

Disclosure: to fit a snippet of the podcast interview in the magazine, the interview was significantly edited, while hopefully keeping the original intent/meaning of the author’s words Please refer to the original audio to listen to the full unedited versionofourconversationwithKevin. . 19 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

The Scientist Next Door

EUSci: Would you say that more qualitative approaches such as stories and interviews can be more helpful in capturing information that can’t be categorised as easily?

Kevin: Yeah, definitely. I think often when we speak about qualitative methods, we ' re more comfortable thinking about questions of emotion and bringing your own biases and baggage to the types of methods you ' re using What I want to do with my research and my writing is to argue that these same issues should be given consideration when using quantitative methods. Just because you ' re designing a survey or aggregating different categories in a data set, this also comes with decisions about who counts and who doesn't count We're definitely more comfortable seeing qualitative methods through that lens and we ' re a little bit more reluctant to challenge the objectivity of quantitative methods There's a long history there around numbers and these types of scientific approaches being seen as “harder sciences” or more objective compared to stuff which is maybe seen as more emotive or more human-oriented What I hope people get from reading my book and my work is just that we should think critically about all of these methods whether or not they're quantitative or qualitative.

“Certain methods are sold to us as being inclusive but can sometimes only count parts of larger communities.”

EUSci: You mentioned there's this difference between how data science is seen in terms of “hard sciences” or more qualitative work Do you think that modern day data science has been affected heavily by historically more sinister figures who have been very much categorising people by focusing on eugenics or trying to fit people into very narrow boxes?

Kevin: That's a great question, and definitely, 100% In the book I trace how we got where we are around LGBTQ+ data in the UK, and I think it's impossible to write that history without thinking about histories of race, eugenics, and these historical approaches to

categorising, counting, managing different populations,asyoumentionedinyourquestion The goodofthepeoplebeingcountedwasrarelyatthe heartoftheintentionsofthescientistsorfigures behind these campaigns I think particularly the historyofracescience,categorisingraceanditsuse foreugenicsprojects,shoulddefinitelyplayakeyrole inhowwethinkaboutLGBTQ+datainthepresentday. Iamalsointerestedinwhatdatahistoricallyexists about communities who we migh now describe as LGBTQ+ If we go into an archive and look for quantitativedataaroundgaymen,forexample,what typeofdatacanwefind?Andasyoumightimagine, the data that exists historically about these communities is very one-sided and extremely negative It was collected for particular purposes around monitoring crime deviant psychological maladjustment Alotofthedatathatexistedwasnot to highlight the positives (or the roundedness) of thesecommunities'livesandexperiences Thisisa reallyimportantpointwhenwethinkaboutcurrent daydevelopmentsarounddatascienceandmachine learning algorithms – these gigantic datasets that makeuseofahugeamountofhistoricalinformation aboutthesecommunitieswhichcanthenveryquickly resultinbiasesintheirdesign.

EUSci: So in terms of changing approaches, your work talks about the concept of “queering data” – can you explain what you mean by that?

Kevin: My book is called Queer Data, and I do hope that it provides an accessible introduction to work in this field There's been around maybe five to ten years of work around LGBTQ+ data in the UK and US by academics, social justice activists, and practitioners working across a range of different fields In the book I bring together these ideas to argue that queer data can be understood in two ways On one hand, we ' ve got the type of data about LGBTQ+ communities that is maybe what comes to mind first when you think of queer data: data on education, healthcare, and employment, whether it's quantitative or qualitative The second strand of Queer Data, which I think is probably a little bit more interesting, is about thinking of how to queer data in the verb sense. How do we queer different research methods? This applies to people doing any type of research, people that may or may not be engaging in topics around identity It could be stuff around fishing or farming – I'm trying to think of just examples not related explicitly with LGBTQ+ lives. It engages ideas from queer theory and queer

The Scientist Next Door 20 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

✷ You can download a free copy of Queer Data through the university library ✷

studies which date back to the late 80s/early 90s It explores questions around how we construct knowledge, how power shapes our ideas around who counts and who doesn't count, and how we then apply that in the design of different methods we use in our work. I hope to bring those two strands together in the book and provide ideas that I hope are accessible for people wherever they are on this journey

EUSci: For the censuses that have come out recently for England and Wales you can zoom in on a particular area and see how many people of a certain identity live in that area, which is terrifying if you ' re one of those people So how do you balance making sure people are counted for but also ensuring that this doesn't affect their safety or ability to just live their lives as they normally would?

Kevin: Oh, another fantastic question Just around the politics of visibility, this is a fascinating topic particularly when we think about it through the lens of data collection Irregardless of what number is published on the size of particularly the trans population in the UK, for people opposed to trans inclusion the number was always going to be both too high and too low I think we need to be speaking about whether the benefits of being accounted for in something like the national census outweighs the risks and the energy and resources that I know many LGBTQ+ people and groups and community organisations have had to put into addressing that increased visibility The argument in my work is that when we ' re captioning data on minoritised communities – for example, LGBTQ+ people – it’s always going to have an inbuilt undercount because, for a variety of legitimate and valid reasons, many people will not wish to share that information in a census. We need to think about the fallout of this, the toll on people's lives, and I think we also need to ask whether it matters – can we actually direct resources that improve people's lives without exactly knowing the percentage of trans people who live in Manchester or Liverpool or Brighton? I don't know if we need to have all of that information to actually address the problems that people face in their dayto-day life and whether this to some degree might just be a misuse of resources

EUSci: I guess we always have to weigh the benefits of data collection versus the trust that you have in the institution to protect that data

Kevin: Yeah, I think it is that kind of weighing-up game I don't want to be too doom and gloom, because there are also positives I remember speaking at events around Scotland at the time of the census, and I was really excited about the opportunity to mark in the census that I am a gay man living in Edinburgh on that date There's no right or wrong answer for these topics we’re speaking about – there's no one way to queer methods. There's no one way to apply a queer approach to work, I think it's all just thinking through these nuances and complexities and particularly in scientific methods that are often seen as objective, above politics or history It's about having space to have these conversations, that actually things are messy and complicated and have good and bad points

EUSci: What do you think is going to be happening in the queer data field going forward – anything you’re looking forward to or concerned about?

Kevin: Oh, in my kind of “crystal ball” thinking of what might happen next? My work is continuing in this space but zooming out a bit I’m working on a second book that looks more broadly on how to classify and categorise LGBTQ+ communities Whereas Queer Data focuses on data and how we collect, analyse, and use it, with the next book I am more interested in how we use systems that we might not usually associate with data to make sense of LGBTQ+ people – looking into things like hate crime reporting, dating apps, rules about asylum and borders, and film funding In terms of the broader queer data space I think what's exciting is just seeing the appetite for these ideas – not only for people working in fields around gender, sex, and sexuality but for those working in other data spaces such as privacy and data protection and how this queering of methods might be applied in their work Also what I would love to see as much as possible is these conversations happening outside of academic circles and outside of universities Doing this work around data and LGBTQ+ lives, my hope is that it's engaging people across many different workplaces, organisations, and activist groups – whatever your job, role, or context, there can be something in it for you –and I hope that's what the book adds to these conversations

Guest: Kevin Guyan is a writer and researcher whose work explores the intersection of data and identity He is the author of Queer Data: Using Gender, Sex and Sexuality Data for Action (Bloomsbury Academic) Podcast hosts: Katie Pickup is a final-year PhD student in Genetics and Molecular Medicine, working on embryonic stem cells and developmental biology. Kelsey Tetley-Campbell is a final-year PhD student in Genetics and Molecular Medicine, working on the genetic causes of sex-biased diseases

The Scientist Next Door 21 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

Bringing humanity and humour to science writing

Kája Kubičková argues for a more h d t sparent approach to cation that celebrates

Sthe entirety of the social landscape, p ple can feel so disconnected from a processthatshapessomanyfacetsofourlives?Howcanwe

work towards clear communication and a comprehensive understanding of complex scientific topics, given the bidirectional natureofscientificresearch?Itseemstobedifficulttodislodgethe idea that communication within academia is aided by the strippingaway of humour personality, and opinion, and that scientific s not real science This view makes it process of understanding and more a rately make our communication as confusing and inflated as possible I believe there should be further encouragement of science writing that is clear and accurate, that y, but that still retains enthusiasm and humour. ach science writing as storytelling, meant to ain Scientific communication should not only be widely available and accessible; it should recognise science as a series of processes rather than as mere conclusions Nobody wants the hero defeating the dragon without first reading thatledhimthere.

The anti-vaccine movement is a common example of the failings of some current science communication (though it must be mentioned that there are some brilliant science communicators wisher at MIT, or the NASA-scientist dall Munroe) It’s often assumed that t stems from miscommunication and ction of vaccines While it’s true that , it's far too easy to blame the public ed scientific principles. We often fail a problem with the way institutions communicate the topic to the public It’s not necessarily the case that the public doesn’t have accessible information about vaccines. Many concerns around vaccines come from individualistic approaches to these issues, which cannot be alleviated by sentiments focusing on the bigger picture of public health. That is, n’t want to risk the side-effects of ther than, “I’ll vaccinate my child to isedinoursociety.”

Thoughthis sentiment isnotoneIam endorsing,itshouldbe approachedwithempathy. We must focus on more than remedying a perceived lack of knowledge; we must also prioritise rebuilding trust and fostering dialogue between the scientific community and the public We need to address the public’s concerns as valid –people are much more amenable to change when they don’t feel that their fearsarebeingdismissed

Recognising and questioning errors, faults, and uncertainty is a cornerstone of good science, yet the media often struggles with depicting this complexity There’s a tendency to show research as definitive, and researchers themselves might at times prefer to take this route in their communication for fear of loss of scientific authority Yet contrary to this expectation, one study has found that expressing reservations in the communication of research can increase trust, as addressed by Mickey Steijaert andcolleagues.

The Scientist Next Door

e.

22 S i 2024 | sci org uk

Rather than undermining the research it paints the author as a more objective source Science shouldn’t be displayed to the public as a monolithic authority dictating the correct opinions to be held – failures should be discussed, doubt dissected, and changes in previously upheld scientific dogmas celebrated Placing scientists on a pedestal o unquestionability is harmful not only to science itself but also to the public’s perception of science It is my opinion that by positioning researchers as incontestable authorities, sensationalist science media publications actually give rise to further mistrust in science. Rather than being viewed as a process, and a very human one at that, science is portrayed as something unreachable to the layperson, something beyond comprehension and conducted only in closed-off institutional laboratories. Not only is this image a breeding ground for conspiracy theories centred around shadowy scientific institutions –probably surrounded by ominously bubbling test tubes and human organs suspended in tanks – it makes scientific knowledge seem inaccessible While much of the background behind scientific processes requires significant time and study, we should be focusing on closing that very gap between science and the public The first step towards gaining more public trust is to move away from sweeping claims about the conclusions gained from research and to focus on the process and the questions that remain. We should discuss criticisms and possible errors in research openly Concerns will arise within the public sphere either way – it’s preferable for issues to be expressed by individuals who are knowledgeable on thespecificsubjectandtoopenthedoor to conversations that might facilitate further understanding of research We must not only accept but celebrate fallibilityandhumanitywithinscience

to present somethin yless in the i li m?

difficult undertaking, but that doesn’t mean we need to dehumanise it in the process.”

Another concern I ha stripping of emotion fr valid While it’s underst be suffused with jargo humour and humanity f science writing aimed researchers Why do w inherently joyless in the serious and often difficu need to dehumanise it in the process While data sh presented accurately within a general code of conduct, of professionalism and an urge to present ourselves as intellectual within the scientific sphere shouldn’t drive how we writeaboutscience.

Researchers should not be forced to make their writing and joyless as possible in order to be perceived as competent scientists Science should be widely il bl d ibl the public, and that extends to c difficult to recognise the line betw digest and sensationalising it, but I f and is wider than we might think Beyond the project of humanising science to make research less alien, we might also ask: why shouldn’t we find joy in our work? I think a lot of science isprettydamnamazing–andnotonlydoIthinkweshouldbeable to express that joy when writing about it, I don’t think it takes away from anyone’s merit as a scientist Conversely, I’d argue it makes them a better science co i t d h throughthatpassionforscience,abe

Kája Kubičková (she/her) is a third-year Neuroscience student She is a big fan of xkcd, weird brain facts, and cool research into neural circuits

Scientist Next Door

23 Spring 2024 | eusci k

I’m an

Academic…

Get me out of here?!

Juda Milvidaite shares their journey as an academic, highlighting the need to check in with ourselves more often.

Iwas on my lunch break at the Chancellor’s Building, where I was working on my Neuro-

science Honours project, when I overheard someone crying It was a PhD student venting to a friend about their project and, mostly, venting about their suffering I can’t remember the troubles exactly, but I remember thinking that I was witnessing the canonical PhD experience In that moment, I vowed to myself that this would never be me I did not want to end up crying in the cafeteria. I did not want to perpetuate the stereotypes of a suffering PhD student So, I would never do a PhD. And yet... “Do you want to stay in academia?” we often asked each other What was academia beyond the unknown or the suffering? I think for me it was the learning The unknown becoming known If only I could stay at the university forever, I thought I was in love with the pursuitofknowledge

One out of five students will not finish their PhD (UK Research and Innovation, 2011) I dropped out of my bioengineering PhD halfway through my four-year programme To be frank, before I began my project journey, I mostly felt curious: what was this infamous PhD journey all about? Testing it in my hands, I was doing a case study on whether the PhD life was for me But, I had also given myself the permission to withdraw from the case at any point

Why do people exit academia?

1 Mental health

It is completely normal to have a non-linear journey. Time, healing – both are non-linear I had already left academia once after my undergrad At the time, I was feeling so burnt-out, I felt I would never again be able to face another scientific article. I had to face my feelings instead. Later, I came back because I had missed science Throughout my undergrad – I later realised – I used science, learning, the long hours at the library, the organised notes – all as a coping mechanism

But life doesn’t stop happening because you’re doing science Life has its ups; life has its downs And naturally, there might come a point when you need to re-invent your coping strategies PhD students are at least twice as likely to show signs of severe anxiety or experience depression when compared to other working professionals (published in the Humanities and Social Sciences Communications journal, 2021) Moreover, around half consider developing mental health problems as a normal part of the process It is a marathon, not a sprint But also, it is a challenge in perseverance

But what do you do if you’re not coping with the process? Does the end justify the means? In the end, what matters?

In my opinion, to be a real academic, you must be married to your research Either way, to be happy, you must feel connected

You need community Part of what can make or break a PhD is the isolation In the wrong lab, the dodgeball of everyday social dynamics might be exhausting. If you come from a different country – away from family, friends, and familiar resources, having to self-fund or navigate visa restrictions and funding conditions – even in a supportive group, pausing studies for mental health or personal reasons may simply be much, much harder to arrange

2. The group

The research group, its own work culture and team dynamics can also make or break a PhD Whether there is unspoken pressure to spend most of the social and living hours by the lab bench or whether a student feels enabled to have a work-life balance and flexible hours – this all can be very groupdependent There are other stressors outside of a student’s control that become clear only once inside They can range from the general pressure to publish, to the group lacking funding and having to scramble for resources, or, of course, personality clashes, egos, discrimination, harassment and bullying within the group, or even the ethical and scientific dilemmas arising from pressure to falsify data Even in the absence of such extreme problems, in well-funded and successful labs, a student might suffer feeling forgotten.

The Scientist Next Door

24 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

A successful and busy principal investigator (PI) might be too busy to learn about each student’s work style – too absent to establish an effective, supportive working relationship Or the supervisor might be too set in their ways to adapt to students needing different direction styles. Not every good scientist is a good supervisor; not every supervisor is flexible

At the same time, an advantage of a bustling lab is the access to other potential mentors I strongly believe you win as a student once you are “adopted” by a postdoctoral researcher. This way, you not only have someone who can advise or gently push you in terms of experimental design and methodology but often also someone working daily by your side, exploring questions related to yours In any case, it is crucial to find mentors –other scientists within and outside the group –and build your own emotional and research support network. Though that, too, can be stressful, working relationships are key to surviving and staying tethered to academia

3 Changing your mind: many different ways to do exciting science

As a scientist, it is important to always keep an open mind. Maybe you simply need to work on something different Nowadays, many Centres for Doctoral Training (CDTs) recognise that not every student will be interested or stay in academia The CDTs collaborate with industrial partners to give the PhD candidates an opportunity to experience non-academic research.

In or out of academia, there might still be some invisible, intersectional blocks to address Analysing the “Destinations of Leavers of Higher Education Longitudinal” survey, which reported PhD employment activity three-and-a-half years after graduation in the UK, revealed that males who have obtained their PhDs from Russell Group institutions are significantly more likely to secure research roles outside of academia Why are the rest not as likely? Perhaps it’s easier to confident-

“But what do you do if you’re not coping with the process? Does the end justify the means?”

ly pitch yourself with access to more resources and more privilege Science thrives on progress But this has been quite slow when it comes to reflecting the sociocultural forces that different individuals face The work of organising together to dismantle foundational power structures and to make research more inclusive and accessible has just scratched the surface

Outside an industrial lab, scientists are also needed in the public health sector (NHS for the biomedical scientists or Public Health Scotland for the epidemiologists) There are also charities that aim to increase public and patient involvement in science or reduce the use of animals in research. There is policy and governmental work, scientific consulting and writing, communication or outreach You could even marry your love for science and performance art and become a science clown, touring Scottish schools and teaching kids through play You can adapt your research skills elsewhere There are many ways to be a scientist and to do important, exciting science.

The Scientist Next Door

25 Spring 2024 | eusci org uk

Photographs of Juda Milvidaite by Kate Louise Powell

4. The post-doctoral sieve

It has long been a tale in academia how only a very small handful of people who become doctors will ever become professors I ultimately realised I did not care about the academic climb to become a group leader and a professor Indeed, there are some academic roles outside of becoming a PI Research laboratories benefit from highly trained support staff – technicians, scientific officers, lab managers, data analysts – although availability of these roles depends on the available funding, so they may be scarce, too And yet, initially most PhD students will want to do a postdoc – to stick around Nevertheless, as mentioned before, most PhD holders will have left academia within three years post-PhD.

The post-doctoral sieve takes place because of the “cost” of staying in academia One often must follow the research – and the right lab with the right position at the right time could be anywhere around the world For people with family, uprooting the whole family can be extremely challenging. Even for single individuals, the isolating academic lifestyle and he lack of post-doctoral job stability could, in the end, t th m from sticki it t Whil t erience is mic post, ou not valued t

Research suggests that skipping the post-doc entirely could be the wisest financial move, since PhD holders who move to other sectors right after PhD completion earn higher salaries for up to 15 years post-PhD, when compared to those who go on to work post-doctoral positions. In the outside world, your experience and skills are what matter most. So, if you feel that academia is not for you, you might as well begin moving elsewhere – gathering the experience

Conclusion?!

People exit academia for a multitude of complex reasons: personal issues, shifting priorities, family plans, structural barriers within and beyond the scale of a research institute, rigid personality cults, limits imposed by the lack of grants and resources, general lack of job security, or the potential financial sacrifice of sticking around

Me? I took a leap of faith when I jumped into my PhD. Two years into my project, I found myself in agony at the bottom of the proverbial cliff I reflect on the numerous lists of pros and cons I wrote, the many discussions I had with friends, the hours spent reading others' experiences, unable to conclude: Should I stay? Or should I go? I recall my walks outside the Advanced Research Centre in Glasgow, where I was based, going back and forth between feeling that I needed to leave and that I did not want to quit I was still on track I still believed in the project I was surrounded by great minds, ready to advise and help And yet, I remember looking at the art surrounding the University, particularly, a mural outside the Centre which read: “Do What Makes You Happy.” Although research has brought me joy in the past, I had to admit that it was no longer the case I was not happy But if doing a PhD has taught me one thing, it's that what you set out to do is not necessarily where you end up It is okay to try things and make mistakes and, with what you learn, adjust the course as you go. And so, by course correcting, I took another leap of faith. Again, I walked into the vast unknown land – now, outside of university

So, dear academic reading this What would make you happy? Do keep an open mind and take your time The answer might surprise you

Juda Milvidaite (they/them) - the Art Editor for EUSci magazine - graduated from BSc versi n usin th sci

Scientist

Door

The

Next

4 | eusci org

How much

should the public hold the strings?

Whe 21st century digital era has rogression into

new norms We now have access to a vast amount of information available online, the ability to stay up to date with world news, the right to create online platforms and share our opinion across the anonymity of the web, the chance to access the latest scientific advances released in any field with the click of a button Quoting one of the most iconic phrases, “with great power comes great responsibility,” science lies in our hands as undeniably as our ability to shape it With opensource journals and online libraries, freedom of speech of media and online platforms, and a series of open-access talks and seminars organised by the scientific community with the main goal to communicate their research to a broader audience, the average human nowadays holds a significantly more central position in the scientific world than in the past centuries Does having a seat at the centre translate into holdingthestrings?Whatinfluencedoesthepublicreallyhave on the research that takes place? And even if they can have a seat,aninfluence,asay–dotheyreallywanttoclaimit?

Studies conducted by the UK research councils report public participation and engagement as vital to the quality and relevance of science. Engaging a wider audience with different backgrounds on a research topic can open up fresh perspectives, widen the applications, or even lead to different questions and generate new proposals. This way, knowledge is offered to all members of society, regardless of their occupation or scientific background, and simultaneously, the opportunity to partake in it. Particularly the occurrence of open-access talks and public conferences is vastly increasing because of the high participation and appeal among individuals. Such opportunities of interactions between scientists and people interested in science are indispensable forthequalityofresearch

Discussions on the outcomes of current inventions or discoveries can underline the level of urgency, use, and interest around a topic and allow researchers to acquire a more representative idea on how their research reflects on society as well as present society with important insights into theaimsandreasonsoftherespectiveresearch