Rooting out invasive plants

Invasive plant species can pose a significant threat to indigenous plants, and they must be managed effectively to maintain floristic diversity. We spoke to Dr Sònia Garcia about the LIFE medCLIFFS project, in which researchers are working to identify and manage invasive species, helping to protect the environment on the coast of northern Catalonia.

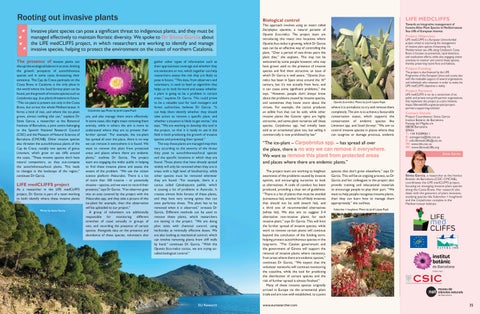

The presence of invasive plants can disrupt the ecological balance in an area, limiting the growth prospects of autochthonous species and in some cases threatening their existence. The Cap de Creus peninsula on the Costa Brava in Catalonia is the only place in the world where the Seseli farrenyi plant can be found, yet the growth of invasive species such as Carpobrotus spp. (ice-plant) threatens its future. “This ice-plant is present not only in the Costa Brava, but across the whole Mediterranean. It forms a kind of mat, and where the ice-plant grows, almost nothing else can,” explains Dr Sònia Garcia, a researcher at the Botanical Institute of Barcelona, a joint centre belonging to the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the Museum of Natural Sciences of Barcelona (CMCNB). Other invasive species also threaten the autochthonous plants of the Cap de Creus, notably two species of genus Limonium, which grow on sea cliffs around the coast, “These invasive species don’t have natural competitors, so they out-compete the autochthonous/local plants. This leads to changes in the landscape of the region,” continues Dr Garcia.

LIFE medCLIFFS project

As a researcher in the LIFE medCLIFFS project, Dr Garcia is part of a team working to both identify where these invasive plants

are, and also manage them more effectively.

In some cases, this might mean removing them entirely, while in others the aim is more to understand where they are to prevent their further spread. “For example, the ice-plant has spread all over the place, there is no way we can remove it everywhere it is found. We want to remove this plant from protected areas and places where there are endemic plants,” outlines Dr Garcia. The project team are engaging the wider public in helping to find these invasive plants and assess the extent of the problem. “We use the citizen science platform iNaturalist. There is a list of more than 100 invasive – or potentially invasive – species, and we want to record their presence,” says Dr Garcia. “If an observer goes into an area covered by the project with the iNaturalist app, and they take a picture of this ice-plant for example, then this observation will be uploaded to our project.”

A group of volunteers are additionally responsible for monitoring different stretches of coast annually in groups of two, and recording the presence of certain species. Alongside data on the presence and abundance of these species, volunteers also

gather other types of information such as their approximate coverage and whether they are senescent or not, which together can help researchers assess the risk they are likely to pose in future. “This data, from observers and volunteers, is used to feed an algorithm that helps us to look forward and assess whether a plant is going to be a problem in certain areas,” explains Dr Garcia. This could prove to be a valuable tool for land managers and forest authorities, believes Dr Garcia. “It can help them identify whether they should take action to remove a specific plant, and whether a situation is likely to get worse,” she says. “We are working to develop this tool in the project, so that it is ready to use in the field in both predicting the growth of invasive species and preventing their spread.”

The way these plants are managed may then vary according to the severity of the threat they pose to autochthonous/local species and the specific locations in which they are found. Those plants that have already spread widely will only be removed when they are in areas with a high level of biodiversity, while other species must be removed wherever they are found. “For example, there is a cactus called Cylindropuntia pallida, which is causing a lot of problems in Australia. It creates almost little forests of these plants, and they have very strong spines that can even perforate shoes. This plant has to be removed when it is observed,” stresses Dr Garcia. Different methods can be used to remove these plants, which researchers are testing in the project. “We are doing pilot tests with chemical control, using herbicides at minimally effective doses. We are also looking at mechanical control, which can involve removing plants from cliff walls by hand,” continues Dr Garcia. “With the Opuntia ficus-indica cactus, we are trying socalled biological control.”

Biological control

This approach involves using an insect called Dactylopius opuntiae a natural parasite of Opuntia ficus-indica. The project team are introducing this insect into locations where Opuntia ficus-indica is growing, which Dr Garcia says can be an effective way of controlling the plant. “Over a period of two-three years the plant dies,” she explains. This may not be welcomed by some people however, who may have grown used to the presence of invasive species and find them attractive, an issue of which Dr Garcia is well aware. “Opuntia ficusindica has been in Spain since around the 16th century, but it’s not actually from here, and it can cause some significant problems,” she says. “However, people don’t always know about the problems caused by invasive species, and sometimes they know more about the virtues. For example, the cactus produces an edible fruit that can be sold, while other invasive plants like Gazania rigens are highly attractive, and some plant nurseries sell these species. Carpobrotus spp. had initially been sold as an ornamental plant too, but selling it commercially is now prohibited by law”

where it is unrealistic to try and remove them completely. The aim is to achieve a favourable conservation status, which supports the conservation of endemic species like Limonium spp. and Seseli farrenyi “We aim to control invasive species in places where they can outgrow or damage precious, endemic

“The ice-plant – Carpobrotus spp. – has spread all over the place, there is no way we can remove it everywhere. We want to remove this plant from protected areas and places where there are endemic plants.”

The project team are working to heighten awareness of the problems caused by invasive species, and encouraging nurseries to look at alternatives. A code of conduct has been produced, providing a clear set of guidelines.

“There is a list of plants that must be avoided (consensus list), another list of likely invasives that should not be sold (watch list), and a third one of recommended alternatives (white list). We also aim to suggest 3-4 alternative non-invasive plants for each invasive plant,” says Dr Garcia. This will limit the further spread of invasive species, while work to remove certain plants will continue beyond the conclusion of the funding term, helping protect autochthonous species in the long-term.

“The Catalan government and the government of Girona will support the removal of invasive plants where necessary, from areas where there are endemic species,” continues Dr Garcia. “We expect that the volunteer networks will continue monitoring the coastline, while the tool for predicting the distribution of certain species and the risk of further spread is almost finished.”

Many of these invasive species originally arrived in Europe via the ornamental plant trade and are now well-established, to a point

Towards an integrative management of Invasive Alien Plant Species in Mediterranean Sea cliffs of European interest

Project Objectives

LIFE medCLIFFS is a European Union-funded project aimed at improving the management of invasive plant species threatening the Mediterranean sea cliffs along Catalonia’s Costa Brava. It focuses on prevention, rapid detection, and eradication efforts, while also engaging citizen scientists to monitor and control these species, thereby preserving native flora and habitats.

Project Funding

The project is also financed by the LIFE Programme of the European Union and counts also with the invaluable support of several organisations and individuals who volunteer in order to make the LIFE medCLIFFS objectives a reality.

Project Partners

LIFE medCLIFFS is run by a consortium of six public and private non-profit partner organisations that implement the project as a joint initiative. https://lifemedcliffs.org/en/project/projectpartners-supporting-entities/

Contact Details

Project Coordinator: Sònia Garcia Institut Botànic de Barcelona Passeig del Migdia s/n 08038 Barcelona

SPAIN

T: +34 932890611

E: soniagarcia@ibb.csic.es

E: info.lifemedcliffs@csic.es

W: www.ibb.csic.es

W: www.lifemedcliffs.org

species that don’t grow elsewhere,” says Dr Garcia. This will be an ongoing process, so Dr Garcia and her colleagues in the project also provide training and educational materials to encourage people to play their part. “We want to help people recognise invasive plants, then they can learn how to manage them appropriately,” she outlines.

Sònia Garcia a researcher at the Institut Botànic de Barcelona (CSIC-CMCNB), coordinates the LIFE medCLIFFS project, focusing on managing invasive plant species along the Costa Brava. Her research also deals with the genomics of plant invasions, studying species like Kalanchoe × houghtonii and the Carpobrotus complex in the Mediterranean habitats

Sònia Garcia

Carpobrotus spp. Photo by Jordi López-Pujol.

Opuntia ficus-indica. Photo by Jordi López-Pujol.

Photo by Sònia Garcia.

Kalanchoe × houghtonii. Photo by Jordi López-Pujol.