Teshuvah, repentance, is not just about fixing failures. It’s about fixing priorities.

This insight is far from obvious. Teshuvah is generally regarded as a spiritual therapy for the wayward, one which repairs the damage sin does to their souls. But the Zohar, the great book of Jewish mysticism, makes a fascinating remark about “the Teshuvah of the righteous.” This seems counterintuitive; for what could the righteous be repenting? Multiple thinkers are inspired by this passage to assert there is a “higher” teshuvah which is just as relevant to the righteous as it is to everyone else; instead of fixating on past transgressions, this higher Teshuvah focuses on the future and the possibility of spiritual renewal.

This then is the greater goal of the high holidays: to reset our priorities, reconnect with our mission, and spiritually renew ourselves. We certainly need to repair what has gone wrong, but it is even more important to pursue what is right. Now, at the beginning of a new year, is the time to chart a course to the best possible version of ourselves.

This booklet, entitled Todieini, takes its name from the verse in Psalm 16:11, םייח חרוא ינעידות: “You make known to me the path of life”; in it, David thanks God for giving him direction and purpose. The Midrash Tehillim relates this verse to the Ten Days of Repentance between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, when we, too, search for direction and a path to connect us with eternity.

In our own pursuit of this path of life, we highlight 13 Jewish values that are timeless.

There are many other values that should be included in a book like this, but these 13 were chosen because they best reflect KJ’s mission and history. As KJ enters its 151st year, we hope these age-old values guide our congregation to live meaningful Jewish lives in the future.

Sincerely,

Chaim Steinmetz“I don’t want to.” It may seem strange that the greatest Jewish leader begins his career with a refusal to lead; but Moses on no less than seven occasions tells God that he doesn’t think he’s worthy of leadership. (Moses is not alone in this regard; both Jeremiah and Jonah also refuse God’s calling.)

It might seem paradoxical, but the Torah sees having no interest in leadership as the ultimate leadership credential. This is because a Jewish leader is not driven by ego, but rather by the desire to stand up for what is right.

There is an entire academic discipline devoted to leadership, which focuses on how to lead, and who should lead. But the Torah considers different questions: Why should I lead? Is what I am undertaking a worthy mission?

Great Jewish leaders are not fueled by a passion for leadership; they are driven by a passion for their mission.

But leadership is not just for leaders; every person is called upon to take up a leadership role at some point. The Mishnah explains, “Where there are no others, be the one to take a stand.”(Pirkei Avot 2:5) As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks explains, leadership begins with a sense of responsibility, and “responsible life is a life that responds.”

It is incumbent upon all of us to step up when needed, because true leadership demands we answer the call when the time comes.

In the symphony of Jewish life, the value of “masoret” resonates as a timeless melody, guiding us through the ages. Masoret is the sacred chain that links generations past, present, and future, carrying the torch of Jewish continuity. It is the foundation upon which we stand, rooted in the wisdom of our ancestors and the preservation of our shared heritage.

As we embrace masoret, we honor the custodians of Jewish tradition, our link to generations gone by. Ethics of our Fathers begins, “Moses received the Torah at Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, Joshua to the elders,” and so on. We learn from our ancestors, humbly acknowledging that we stand on the shoulders of giants who preserved our faith through trials and triumphs. Yet, masoret is not a stagnant force; it is a living legacy that invites us to reinterpret and revitalize our heritage while remaining true to the essence that has sustained us for millennia.

Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook wrote in Orot HaTorah, “Every thought, whether in the realm of Jewish law and tradition, ethics, or fear of God, that settles more deeply in our soul, we are built by it, and through it, we construct the entire universe.” Through better understanding the ideas of our Jewish tradition, we build and construct new ones. Judaism is a living, breathing tradition that continually evolves to embrace “hitchadshut,” newness and innovation. Our ancient faith is not static but dynamic, responsive to the changing tides of time.

Hitchadshut invites us to engage with Jewish texts, teachings, and practices with an open and curious mind. Through creativity and ingenuity, we breathe new life into our sacred rituals, ensuring their relevance and resonance with future generations. Just as our sages of old expounded upon Torah, we, too, have the responsibility to engage in thoughtful dialogue, forging new connections between ancient wisdom and contemporary realities. “Lo bashamayim hi: the Torah is not in the heavens,” taught Rabbi Yehoshua in the Talmud. It is ours to interpret, and our task is to reveal its layers of meaning while staying rooted in the rich tapestry of masoret.

Israel is a home, a homeland, and a powerful story of hope.

A home is a place that belongs to you; a homeland is a place that you belong to.

The State of Israel is a home for refugees from all over the world, including the Soviet Union, Ethiopia, and Syria. But at the same time, the land of Israel is the Jewish homeland.

The first command Abraham receives is “Go from your country, your people, and your father’s household, to the land I will show you.” Abraham’s religious journey begins with the search for his homeland; and for the next 3,800 years, Zion would nurture the Jewish soul.

During two millennia of exile, Jews never despaired of returning to their homeland. When the Jews were exiled for the first time, Jeremiah declared that they must hold on to hope (Jeremiah 33:10-11 ):

“Thus said the LORD: Again there shall be heard in this place, which you say is ruined, without man or beast— in the towns of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem that are desolate, without man, with-

out inhabitants, without beast—the sound of mirth and gladness, the voice of bridegroom and bride…”

The words of Jeremiah’s prophecy became part of the wedding liturgy, and even today, the entire audience bursts into song when these words are read. The hope of returning home never stopped.

A few years ago, I was waiting for the elevator in a Jerusalem hotel. When it arrived, a bride in her wedding dress got out. For a moment, my heart skipped a beat; Jeremiah’s prophecy, one which had given so much comfort to generations of persecuted Jews, was now true. The story of a great redemption was standing right in front of me, wearing a white wedding gown.

Israel was never forgotten by the Jews. They prayed towards Jerusalem, and for Jerusalem, three times a day. On Tisha B’Av, they grieved for the destruction. At the Seder, they sang “Next Year in Jerusalem” with all of their hearts. And now this dream has come true; the Jews have returned to their homeland.

Such is the power of hope.

Judaism views a “kehilah” as more than an aggregation of people. It is an orchestra of diverse elements producing a harmonious masterpiece, celebrating individuality while nurturing profound unity and purpose. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks beautifully expresses this idea in his article “Three Types of Community” where he says that kehilah differs from the other Hebrew terms for community, an “edah” or “tzibbur,” as it not only carries a shared purpose but it also values individual uniqueness, fostering a sense of belonging and significance within a unified context.

An edah signifies a community bound by shared identity and purpose, characterized by common experiences. It embodies a strong collective identity, where individuals have witnessed the same events and are united by a shared goal, as exemplified when the Israelites were commanded to take a lamb for the Passover sacrifice.

A tzibbur refers to a minimalist gathering. It encompasses a group of individuals who may not know each other well or share deep connections but come together for a specific purpose, such as forming a prayer quorum. The tzibbur is defined by its temporary and functional nature, assembled for fulfilling particular commandments.

In contrast, a kehilah represents orchestrated unity in diversity for a collective endeavor. As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks eloquently states, “The greatness of the Tabernacle was that it was a collective achievement – one in which not everyone did the same thing. Each gave a different thing. Each contribution was valued – and therefore, each participant felt valued.”

As I approach the Amud, my heart quickens in anticipation. This mo ment, when I stand before the Judge on behalf of the Congregation, is one that always touches the deepest recesses of my soul. I take a deep breath and muster the courage to sing: “Hineni He'ani Mima'as”

Here I am, empty of deeds and trembling with fear, a humble conduit between myself and God.

This prayer resonates within me unlike any other. It’s a unique junc ture of personal reflection. The weight of the journey we are about to undertake, that begins with Musaf on Rosh Hashanah and continues through Ne’ilah on Yom Kippur, rests upon my shoulders as your Shali ach Tzibur.

Conflicting emotions stir inside me. On one hand, I stand as your rep resentative through which your prayers flow. Yet, in the same breath, I am reminded of my own unworthiness, sins and shortcomings. With an open heart, I plead for strength so that Hashem will accept our col lective prayers.

In some congregations, this prayer is whispered, a deeply private com munion between the Chazan and God. However, I find inspiration in raising my voice and including the congregation with me. As my voice swells, a palpable energy courses through the room, bolstering me. Your presence, your shared faith, gives me the resilience to stand tall and plead before Hashem.

My prayer is not just mine, it is OURS—a collective expression of the hopes, dreams, and supplications of every individual in the room. The cadence of the text shifts from the singular, my personal offering, to the plural, our communal supplication. The notes I sing are not mine alone; they’re but a part in a shared symphony of prayer.

“Hineni!” The declaration hangs in the air, a testament to vulnerability and strength, to humility and aspiration. In this moment of deep con nection, I find purpose. As your Cantor, I’m not just a conduit; I’m a thread in the tapestry of faith that we weave together.

With you, the KJ Family beside me, together we stand at the threshold of the New Year, embracing the journey ahead with open arms and an open heart.

Torah study is not just for the elite, nor is it the rote memorization of a few ancient passages. It is for young and old, scholars and beginners alike; it offers everyone a journey into the ideas and ideals of Judaism.

The Jewish emphasis on in-depth, universal study is unique among world religions; and that has made all the difference. An endless pursuit of learning meant that education became the Jewish community’s number one priority. The Talmud’s emphasis on the importance of questions has made rigorous analysis a hallmark of Jewish culture. Above all, the constant search for answers and insights transformed the Jewish soul. In a recent interview, one returnee to Judaism said: “When I plugged into Torah—what Judaism is—it was like electricity.” Our souls are searching for something more than the superficial and selfish. Torah study changes our outlook, and raises our aspirations above the mundane and materialistic.

Torah study is also the secret of Jewish survival. Heinrich Heine describes the Torah as a portable homeland, which was a refuge for the Jews during the difficult years of exile. Wherever they may have been, Jews found comfort inside a virtual reality filled with learning, spirituality, and dreams - an otherworldly homeland floating in a sea of words. Through their connection to the Torah, the Jews were able to retain their religious identity in the diaspora.

In an internet age of endless access to information, this connection to Torah has never been easier; and at a time when much of what is available online panders to the lowest common denominator, it has never been more important.

While charity is undoubtedly a commendable act of benevolence, Tzedakah goes deeper, constituting a core Jewish obligation that underpins a just societal structure. It's not confined to the wealthy; Tzedakah is incumbent upon every Jew, irrespective of financial status. This act of giving isn't solely a gesture; it's transformative, a reflection of one's essence as a descendant of our patriarch Abraham.

Abraham embodied the pinnacle of Tzedakah, going beyond mere provisions of food, clothing, and shelter to be genuinely present, caring, and supportive. God's vision for Abraham was to transmit the values of Justice, Righteousness, Tzedakah, and Mishpat to his descendants. During his post-berit milah recovery, Abraham noticed three travelers approaching his tent. He didn't wait for them but eagerly welcomed them with fresh bread and carefully selected cows for a lavish meal. Yet, his sincere presence and empathy for their needs shone through more than the feast. This was more than courtesy; it was a heartfelt connection.

Maimonides delineates eight levels of Tzedakah, emphasizing not just the act of giving but the manner and intent behind it. The highest level is to help someone become self-sufficient by providing a job, a loan, or assistance that helps them regain their independence and dignity. This profound understanding of Tzedakah goes beyond mere financial aid. It's an endeavor to uplift the spirit, restore dignity, and genuinely better our fellows' lives.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks encapsulates this notion, stressing, “What matters is not only how much you give, but also how you do so.” Tzedakah transcends material aid, ensuring that recipients feel genuinely valued and supported.

Judaism is a pioneer in promoting universal education, ensuring each child receives a comprehensive education regardless of socioeconomic background. This age-old mandate highlights the paramount role of education in Jewish life.

An exemplary manifestation of this dedication lies in the Bar Mitzvah tradition. By mandating young boys to master Torah reading, Judaism provides direct access to its foundational texts. This distinctive practice imparts skills and fluency and grants access to our texts, traditions, and the ability to lead services across global communities.

Jewish day schools are integral to this educational journey, pivotal in nurturing young minds.

Equally significant is parental role modeling. Active engagement of children in religious practices, from blessings to Shabbat preparations, nurtures a profound connection to Judaism.

Furthermore, the synagogue serves as a canvas for spiritual maturation. Encountering the hazzan’s prayer and Torah study within the congregation leaves an enduring imprint on young hearts. To kindle their devotion, we stand beside them, praying as a unified entity.

While youth groups contribute enrichment, sharing the congregation’s space fosters a deeper faith bond. Investing in youth education is an investment in Judaism’s future. Just as previous generations entrusted us with their legacy, it’s our duty to guide the next generation in embracing their Jewish identity.

THEWORLDONLY

We as Jews are interconnected, bound by a shared destiny and a common heritage.

Rabbi Akiva illuminated this principle when he declared, “Love your neighbor as yourself; this is the great principle of the Torah.” This foundational idea of unity calls upon us to embrace the diversity of Jewish life and extend a helping hand to our fellow Jews, near and far.

The idea also finds its place in technical Jewish law; it is because of Arvut and the Midrash which states “all Jews are responsible for one another” that one Jew may fulfill certain obligations on behalf of another Jew, such as reciting Kiddush or reading the Megilah on Purim.

This value has been a fundamental cornerstone in the life of the Jewish people throughout all generations and in every place. Saving Jews, redeeming captives, the spirit of camaraderie and closeness in Jewish communities, mutual aid (“Gmachs”), discreet assistance, visiting the sick, hosting brides - these Mitzvot are all manifestations of or at least strengthened by the value of Arvut.

Embracing arvut means recognizing that the wellbeing of every Jew resonates within our own hearts. We are not isolated entities but threads woven together in a vibrant tapestry of Jewish identity. It is not enough to focus solely on our individual journeys; we must actively contribute to the enrichment of our larger Jewish community. Just as a family thrives when its members support one another, the Jewish people flourish when we genuinely care for one another.

I am not able to lead the people myself and alone, unless a body of men is appointed to share the responsibility of leadership; it is too heavy for me.

Chesed is one of the pillars upon which the world stands. There are so many around us who need help and so many opportunities for acts of Chesed. Below is an inspiring story of someone who listened closely and read between the lines to perceive what kind of help was needed.

On the night before Passover, while Rabbi Yosef Ber Soloveitchik (1820-1892, known as the “Beis Halevi” and the Rav of Slutsk) was conducting his search for chametz, there was a knock on the door. Their son answered the door, and the visitor requested to speak with Rabbi Soloveitchik.

“I have a halakhic question,” said the man, “and I’d like to know your opinion. Am I permitted to use four cups of milk for the seder instead of wine?” “Why milk?” asked the rabbi, “Are you sick? If so, you may use juice!” “I am not sick,” replied the man. “I cannot use wine because I cannot afford it. I’m a blacksmith, and I’ve had much trouble making ends meet.” Rabbi Soloveitchik turned to his wife and said, “Tzirel, please give this man 25 rubles.” The man immediately protested: “Rabbi, I did not come here for charity! I came with a halakhic question; I simply want to know whether it is permissible to use milk for the seder instead of wine.” The rabbi replied, “I did not mean it as charity; I am not a rich man and I cannot afford to give you 25 rubles. It is a loan. When business improves, you will be able to pay me back.” The man took the money and went home to prepare for Passover.

When he left, Rabbi Soloveitchik’s wife remarked, “Why did you give that man 25 rubles? Wine does not cost that much. Five rubles would have been more than enough!” The rabbi responded, “Tzirel, didn’t you hear the man say he wants to drink four cups of milk? That means he also has no money for meat. What kind of seder would his family enjoy?!”

How do you keep a large, fractious family together?

This has been the greatest challenge of Jewish history right from the very beginning. Jews are called “the children of Israel” because we see ourselves as a family writ large. But at the very outset this same family was filled with strife, and Joseph is nearly murdered by his brothers.

Despite this inauspicious start, Jews ultimately developed a powerful sense of solidarity with each other. This is due in large part to a common threat from the outside. The exile in Egypt unified the brothers, creating what Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik calls a “covenant of fate.” Through history, this shared suffering has created a powerful bond between Jews, who knew they needed to depend on each other.

But shared history is insufficient. Ironically, it is when things are good that unity erodes. Without a sense of vulnerability, it is easy to get consumed by angry debate. We cannot rely on external enemies to hold us together.

True unity is only possible if we learn how to talk to each other despite our differences. The Mishna explains that the only way to do that is “to debate for the sake of Heaven.”

Rabbi Yehuda Herzl Henkin explains that if you are debating for the sake of heaven, you can still love the person you disagree with; and it is possible to continue respectful debates for years without walking away.

This is a profound insight; and in the growing academic discipline of Conflict Resolution, empathy for the other side is fundamental to ending conflicts. What gets lost in heated debates is the humanity of others, who are immediately caricatured and canceled.

Exile has taught us that unity is the only choice for our community; and the Mishna has taught that respectful debate is the only choice for the future. We must remember these lessons before it’s too late.

We were put on this earth for a reason. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik explains that when the Torah says that man was created in the image of God, it implies that humanity is meant to follow God’s lead and become God’s partner in creation.

The world that God created was incomplete; it was left up to humanity to finish the task. That is why God placed the very first man, Adam, in the Garden of Eden, so that he would cultivate it and care for it (Genesis

2:15.) We are all obligated to cultivate and care for the world around us, and leave it a better place than it was before.

This idea is called shlichut, which literally means to see ourselves as God’s emissaries; and that is not only true of humanity as a whole, but something that we must recognize in our own individual lives, as well. Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook explains that no one would be born unless the world required their existence right at that moment. We are all sent here with a purpose, and everyone has something unique that only they can contribute to this world.

Shlichut is this sacred mission. But all too often, our purpose gets buried under the endless distractions and demands of the mundane. As time goes by, we slowly become what Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel called “messengers who forgot their message.”

But our mission remains, waiting for us to rediscover it.

Inspiration is the spiritual oxygen that sustains our souls. It is why we search for purpose and meaning in life, and aspire to become the best possible version of ourselves. Without inspiration, everyday life seems tedious.

At the same time, inspiration presents us with a constant challenge; it often isn’t there, even if we are looking for it. Maimonides in his introduction to The Guide for the Perplexed writes how difficult it is to find inspiration: “At times the truth shines so brilliantly that we perceive it as clear as day…. (but) then we return to a darkness almost as dense as before. We are like those who, even if they can see during frequent flashes of lightning, nevertheless continue to find themselves in the thickest darkness of the night.”

Lack of inspiration is the norm. You can’t expect to see a bolt of lightning every day.

So what is one to do when inspiration seems distant? The Talmud (Pesachim 117a) offers a solution. It explains that in the Book of Psalms, there are chapters that begin with the words “Of David, a Psalm,” while other chapters begin with the words “A Psalm of David.” The reason for the difference, the Talmud explains, is that when it begins with “Of David, a Psalm,” David had divine inspiration before he wrote the song; when it says “A Psalm of David,” David first sang the song, and then divine inspiration rested upon him.

This is not just an explanation of a textual anomaly; it is an insightful lesson about life. Sometimes we are inspired and can sing without effort. But other times, we feel lost; there is no desire to sing anymore, no inspiration left in our hearts. What do you do then?

You continue to read the song, even without inspiration. Perhaps the energy of the music will bring you inspiration. Sometimes the song will remind you of an earlier time of inspiration, and reawaken your soul again. And worst comes to worst, even if the song doesn’t leave you inspired, it’s still worth singing the song.

We must always search for inspiration. And when it seems further away than ever, it becomes even more important for us to sing our song, and hope that our hearts will follow.

Lessons in Leadership: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (An exploration of leadership themes in the Torah)

MASORET & HITCHADSHUT

Torah Umadda by Rabbi

Norman Lamm

TZION

Israel: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn by Daniel Gordis (A good general history of Israel)

The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership by Yehuda Avner (An inspiring look at the behind-the-scenes history of Israel)

CHINUCH

Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know About the Jewish Religion, Its People, and Its History by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin

Positive Parenting: Developing Your Child’s Potential by Rabbi Abraham J. Twerski.

The Book of Jewish Values: A Day-by-Day Guide to Ethical Living by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin

ACHDUT

One People, Two Worlds: A Reform Rabbi and an Orthodox Rabbi Explore the Issues That Divide Them By Ammiel Hirsch and Yaakov Yosef Reinman. Sadly, no recent books exhibit the thoughtfulness and humanity of this classic.

SHLICHUT

KEHILAH

The Home We Build Together: Recreating Society by Rabbi

Jonathan Sacks

The Lonely Man of Faith by Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik

TZEDAKAH + ARVUT

To Heal a Fractured World: The Ethics of Responsibility by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks.

The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin. The Lubavitcher Rebbe was a powerful proponent of this concept, which stood at the center of his thought.

HASHRA'AH

Ten Days, Ten Ways by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks at rabbisacks.org

Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz

Rabbi Roy Feldman

Rabbi Meyer Laniado

Cantor Chaim Dovid Berson

CONCEPT & CREATIVE DIRECTION

Esther Feierman

ARTWORK, LAYOUT, & GRAPHIC DESIGN

Talia Laniado

COPY EDITING

Riva Alper

Leonard Silverman

PHOTOGRAPHY

Esther Feierman (pp. 8, 9, and blue doors on p. 23)

Talia Laniado (p. 11)

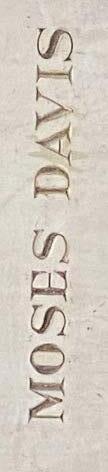

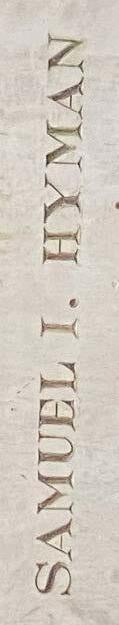

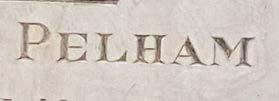

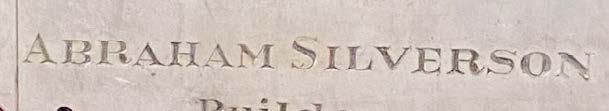

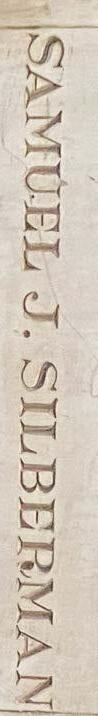

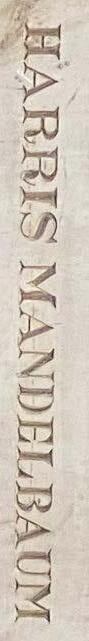

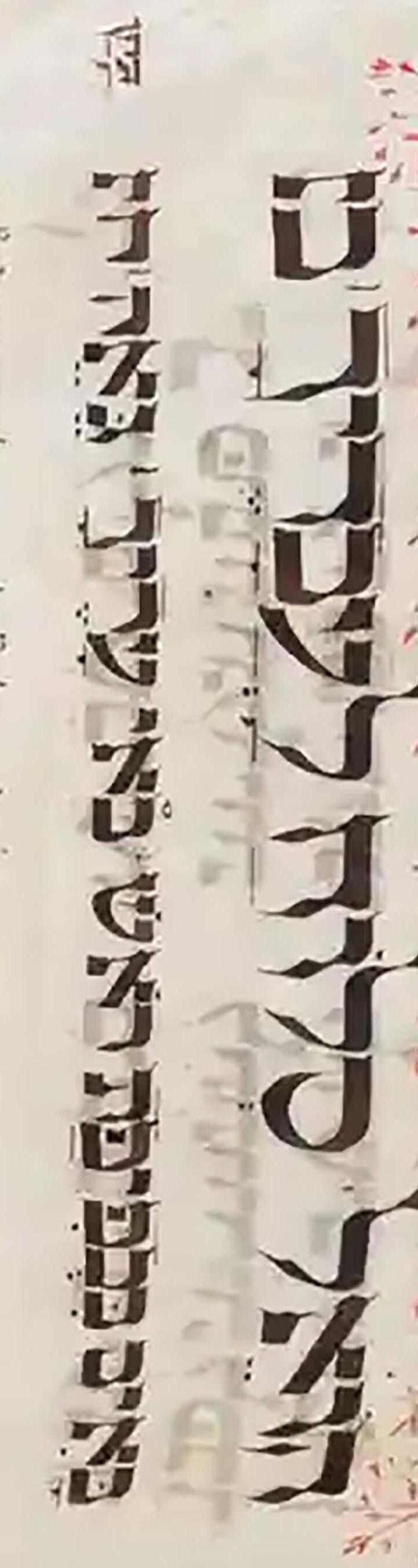

The tablets and Building Committee names are from original stone plaques found in the shul's cellar.

Pexels, Adobe Stock, & Unsplash (all other photos)

PRINTING

Yossi Majer

Manhigut Exodus 3:4

tefilah Exodus 28:29

torah Proverbs 3:18

Chinuch Shabbat 119b

Arvut Numbers 11:14

Achdut Genesis 37:3 & 45:15

Shlichut Isaiah 6:8