QUANTITY

TARGET

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many of us are drawn to architecture by the potential of design to improve the world around us, to shape buildings and cities in ways that provide shelter, inspire with beauty, and promote equitable communities and a more sustainable world. However, we don’t work in a vacuum. We work for clients with their own goals and values. At our best, we find ways through design to meet these goals while unlocking possibilities.

Equality and freedom have always been at the center of the American story. Yet as we’ve begun to understand our history more fully, we recognize that inequality has been present since the beginning, from the displacement of Indigenous Peoples by European settlers to the introduction of race-based slavery in 1619. To be both “the land of the free” and a land made prosperous through displacement and the holding of human beings in slavery required that we build ways of “not seeing”, discounting, or rationalizing this injustice. Land could then be seized, and free labor extracted through violence by asserting that those impacted were uncivilized or not fully human.

These mental structures and justifications for unequal treatment have been passed from one generation to the next and have, until recently, been largely unspoken and unquestioned. When inequality was codified by law and policy in previous generations, from Jim Crow to redlining, it established “facts on the ground,” stark gaps in education, wealth, and access that constitute an uneven playing field. The persistence of these mental structures, reflected in implicit bias, is why we somehow accept a society where some reap the benefits of an industrial society, and others disproportionately bear the brunt of pollution and climate change.

What can designers do? We can start by learning to see what’s truly around us, measuring and mapping it, understanding how we got here, and actively engaging in community-based efforts to make things better. This has been the focus of 2023-2024 Research Fellowship at EskewDumezRipple, “Just | Change”. Research Fellows Elisa Castañeda and Aïda Ayuk built connections with community groups working on environmental and climate justice issues. They heard their stories, read background studies, and helped bring their analytical and narrative skills, and sometimes their physical labor, in support of the initiatives of these groups. They also helped our firm learn from, connect, and support these efforts.

The work that follows, authored by Aïda Ayuk, compiles some of what’s been learned over the course of this year. We hope readers find this a helpful first step in their own initiatives. Change starts with learning to look and learning to listen. Where we take it is up to us.

Z Smith Principal | Director of Sustainability & Building Performance EskewDumezRipple

“The burdens and risks of climate change are not falling equally on everyone.

The poor and communities of color, who have typically contributed the least towards climate change, are shouldering a disproportionate share of the impacts of extreme heat, severe storms, flooding, and wildfires. This imbalance between who benefits and who suffers is similar to the patterns observed by those concerned with issues of environmental justice, where these same communities are often those with the highest exposure to environmental hazards: air pollution, contaminated soils, toxic wastes.”

- Excerpt from the EskewDumezRipple 2023 Just | Change Fellowship Brief

I joined EskewDumezRipple as the 2023-2024 Research Fellow, focusing on environmental justice in our dual office cities of New Orleans and Washington D.C., where I grew up.

Traditional design practices often overlook the nuanced needs and opportunities within communities, leading to solutions that miss critical local issues and perpetuate existing disparities. To address this, direct engagement with stakeholders was prioritized throughout the fellowship through interviews, support for ongoing initiatives, and relationship building. This approach consistently revealed that communities facing significant challenges develop creative, authentic solutions in response. These grassroots efforts, in turn, provide valuable lessons that can enhance and extend the impact of design, making them core to the practice.

This book is intended to show readers ways to connect equity issues to opportunities. The structure encourages readers to think differently, analyze site contexts critically, and evaluate project sites for equity-based opportunities, ensuring a more equitable impact.

Let’s create spaces that are responsive to the communities that they serve.

Aïda Ayuk

Just | Change Research Fellow EskewDumezRipple

The book is divided into six chapters:

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

QUANTITY OF PEOPLE

UNMET COMMUNITY NEEDS

INTERSECTIONALITY

TARGET AREA VULNERABILITIES

YES TO ENGAGEMENT

RELEVANT SUBMETRICS TO ENHANCE UNDERSTANDING OF THE CHAPTER. Each Chapter Overview is followed by an assessment metric:

ASSESSMENT METRIC

Following the assessment metric, to explore ways to translate collected stories, data, and research into tangible applications, a number of submetrics are examined through a repeated series:

NARRATIVE

DEEP DIVE SPATIAL MAPPING

CASE STUDY

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM INTERVIEWS WITH COMMUNITY STAKEHOLDERS.

SUPPLEMENTAL IN-DEPTH ANALYSES OF KEY ASSESSMENT SUBMETRICS.

SIMPLIFIED VISUALS SHOWING WAYS TO INTERPRET EJ SCREENING DATA.

KEY ASSESSMENT SUBMETRICS EXAMINED THROUGH DESIGN PROJECTS.

Environmental Justice (EJ) Screening: Process that identifies and assesses environmental risks in vulnerable communities to address disparities.

Q U I T Y

ASSESSMENT SUBMETRICS

HISTORICAL EVENTS

ANTICIPATED RISK

ECOLOGICAL CHANGES

SYSTEMS IN PLACE

TEMPERATURE

AIR QUALITY

ECOSYSTEM POLLUTION

SENSORY POLLUTION

“Sometimes, it takes a natural disaster to reveal a social disaster.”

- Jim Wallis

Assessing a site and its surroundings for environmental stressors like natural disasters, temperature extremes, and pollution is not just a technical task, it’s a window into understanding an area’s well-being and resilience. Environmental stressors extend beyond physical impacts, profoundly influencing the senses and shaping how individuals experience and engage with their environment daily. For instance, consider a coastal town vulnerable to hurricanes; this known reality prompts investments in storm protection for immediate safety and calls for long-term resilience strategies that enhance communities.

The aftermath of natural disasters often unveils underlying social and economic vulnerabilities in communities. In New Orleans, Hurricane Katrina exposed systemic inequalities in housing and emergency response, highlighting the urgent need for equitable disaster preparedness and recovery plans. Similarly, heat waves in urban areas disproportionately affect low-income neighborhoods with limited access to green spaces or air conditioning, revealing systemic issues in urban planning and social equity. Many of these communities are also disproportionately affected by industrial pollution, resulting in health disparities and underscoring the importance of environmental justice.

It’s critical to address environmental stressors not as obstacles but as opportunities to innovate and enhance experiences. By integrating sustainable and resilient design principles, spaces can withstand environmental pressures and increase well-being and inclusivity.

To address risk, assess existing and future conditions for their Environmental Impact

HISTORICAL EVENTS

Environmental impacts of natural disasters, human activities, or past industrial accidents providing critical context for current conditions and potential vulnerabilities.

ANTICIPATED RISK

Potential or expected future threats such as climate change effects, invasive species, or land use changes proven by scientific models and expert predictions.

ECOLOGICAL CHANGES

Shifts in biodiversity, habitat loss, species populations, and ecological interactions caused by human activities or natural phenomena that impact ecosystem health.

SYSTEMS IN PLACE

Existing infrastructure and physical systems, as well as policy frameworks, such as environmental management systems, regulatory compliance, and programs.

TEMPERATURE

Long-term trends and fluctuations in temperature, including seasonal variations, extremes, and climate change impacts on ecosystems and human health and behavior.

AIR QUALITY

Measured levels and types of pollutants such as particulate matter, volatile organic compounds, and ozone in the atmosphere and the identified sources of pollutants.

ECOSYSTEM POLLUTION

Contamination and spread of pollutants in ecosystems (soil, water bodies, or marine environments) by pollutants like heavy metals, pesticides, plastics, or chemical spills.

SENSORY POLLUTION

Non-chemical stressors like noise pollution (transportation, industry, or urban activities), or light pollution (artificial lighting disrupting natural rhythms and behavior).

“The grass in the park looks patchy and yellow; it’s disappointing.”

“The road noise is so bad; I can’t get a good night’s sleep.”

“The river always looks murky and discolored; it’s really worrying.”

“The temperature seems to be changing more than usual.”

“The air feels so heavy today; I can barely see across the street.”

“I’ve noticed there are fewer birds in my yard lately.”

“Power outages seem to be happening more frequently; it’s getting frustrating.”

“The flooding in my yard is getting worse; I can’t afford this.”

“It feels like the humidity is getting worse; I’m having trouble breathing.”

"There's a strange smell in the air; I don't know where it's coming from."

"The weather looks ominous; are we safe here?"

“I’m worried about the next storm; are we prepared?”

“I’m dreading how many times we’ll need to boil water this year.”

“The summers feel hotter every year; I heard we set a record high last month.”

This is a story about turning individual concerns into collective action and education.

Recognizing the link between individual concerns and broader societal impacts highlights the crucial role of systems thinking. Uncovering these connections helps reveal root issues so that they can be properly addressed.

Dana Eness, Executive Director of the Urban Conservancy, leads key programs in New Orleans. The Stay Local initiative supports local businesses, the Basin Program educates kids on land use and water issues, and the Front Yard Initiative (FYI) incentivizes homeowners to remove paving and design their own stormwater management projects.

“The problem we identified in 2015 came to us through local constituents saying, ‘Hey, I’m noticing [increased flooding] in my neighborhood.’”

Executive Director

The Urban Conservancy

The FYI program began in response to flooding concerns caused by neighbors installing excessive paving. Instead of penalizing homeowners, FYI reimburses per sqft of paving removed and guides residents through the logistics of implementing a stormwater management project.

In 2017, recognizing homeowners’ unique needs and lifestyles, Urban Conservancy and EskewDumezRipple developed an FYI toolkit to empower residents in the design process.

Through supporting minority-owned small businesses, the program has also fostered intergenerational connections, exemplified by the two-woman stormwater management team, Mastodonte, who have built a strong relationship with a Lakeview retiree participating in the program.

“They became such close friends, and there’s a 40-year age difference. They’re from very different backgrounds, but they really loved each other’s company. They just loved each other.”

By funding over 154 projects, the program goes beyond quantitative metrics to emphasize residents’ well-being. It serves as a model for equitable stormwater management, stimulating job growth, building social cohesion, and empowering residents to lead city improvements.

“The goal was to create a movement of people where the more they knew, the more excited they got and the more invested they got in green infrastructure and nature-based solutions.”

“They’re noticing. They’re feeling a difference. They’re feeling better about living here and feeling good about what they’ve done. They’re educating their neighbors about why it’s important and voting for things related to water management. They’re engaging and feeling empowered, informed.”

- DANA ENESS

In flood-prone cities, effective flood protection is essential for safety and stability. New Orleans faces unique challenges due to its location and water history. Subsidence, the gradual sinking of land, whether caused by fault movements, soil compaction, or drying of organic material, exacerbates the city’s flood risk. The drainage system, while intended to manage excess water, prevents rainwater from soaking into the ground, which accelerates land subsidence.

Now, largely sunken below sea level and bordered by the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, New Orleans is highly susceptible to flooding from storm surges and heavy rainfall. Levees play a critical role in protecting areas and infrastructure from inundation. Without them, the city would face constant flood threats. However,

levees also contribute to subsidence by restricting the flow of the Mississippi River, which hampers the natural deposition of sediment that once replenished land during regular floods.

The “keep the water out” approach dates back to early French and Spanish settlers who recognized the need to control water levels in this marshy region. Levee construction began in the late 18th century with earthen embankments reinforced with logs and brush, primarily built by enslaved laborers, Indigenous Peoples, and immigrant workers. Over time, these methods have advanced with improvements in engineering and materials, with agencies like the Army Corps of Engineers playing a significant role in maintaining and enhancing the city’s flood defenses.

Cities in flood-prone areas can adopt a “living with water” philosophy, which involves adapting urban planning and infrastructure to harmonize with natural water systems. This shift in perspective transforms water from a perceived threat into a valuable resource. By focusing on more than just flood protection, water management practices can mitigate risks while enhancing urban biodiversity, water quality, and community health. Engaging and educating the community about these practices drive greater support for sustainable water management.

Green infrastructure, such as rain gardens, bioswales, and permeable surfaces, manages stormwater runoff by slowing, absorbing, and filtering it. This approach reduces the burden on traditional drainage

systems and decreases the need for extensive flood control measures.

Embracing nature-based water management principles can lead to resilient urban designs with multiple benefits. Green spaces created through these systems improve urban ecosystems, offer recreational opportunities, enhance air quality, lower temperatures, and provide wildlife habitats. Integrated strategies support sustainable water use, and collaboration between public and private sectors can accelerate the implementation of these approaches, advancing a comprehensive and effective urban water management system.

Site: Gentilly Neighborhood, New Orleans

Location of the Mirabeau Water Garden and Stormwater Lots Project case studies.

When investigating environmental impacts, the process can begin by focusing on a specific factor for a detailed analysis. For example, the Gentilly Neighborhood is located in a FEMA flood zone, with additional flood zones surrounding it. This highlights the more considerable importance of effective water management strategies.

Proposed strategies should address the specific needs of the individual neighborhood while also considering the broader processes and impacts of natural disasters. It’s important to note additional compounding effects and adapt management approaches to reflect both critical local conditions and overarching environmental challenges.

Environmental impact priorities may vary significantly by city. Regarding flooding, while some cities may focus on critical infrastructure or transportation vulnerabilities, in New Orleans, the focus is often on safeguarding its consistently vulnerable population, reflecting the city’s unique considerations.

HISTORICAL EVENTS

New Orleans’ history of flooding underscores the city’s vulnerability and the importance of resilient infrastructure and community preparedness.

ANTICIPATED RISK

Due to climate change, storms are becoming more frequent and intense, and the likelihood of severe flooding in New Orleans remains high.

ECOLOGICAL CHANGES

Rising sea levels and subsidence continue to alter New Orleans’ landscape, impacting wetlands and natural barriers, thereby increasing the city’s susceptibility to flooding.

ENVIRONMENTAL

CASE STUDY

Multiple small lots can add up to be as impactful as a single large-scale project.

Water management spans various scales, and understanding ongoing city efforts is necessary to support or take on efforts to tackle challenging issues such as permitting, excessive paving removal, or large-scale initiatives.

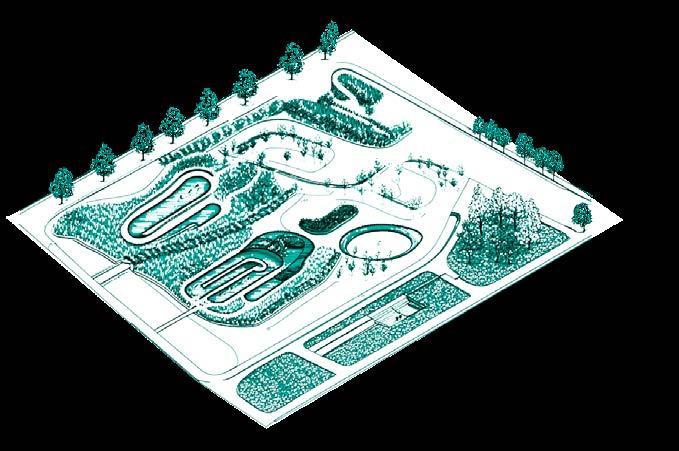

In Gentilly, New Orleans, the Mirabeau Water Garden by Waggonner & Ball and Carbo Landscape Architects is transforming a damaged convent site into a green space for water management. The site, donated by the Congregation of St. Joseph after Hurricane Katrina, honors the convent’s legacy of community service. It will use bioswales and native grasses to reduce flooding, tap into existing drainage systems, and enhance local infrastructure to address critical drainage needs.

Similarly, the Stormwater Lots Project by Dana Brown & Associates, in partnership with the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority (NORA), leverages vacant residential lots for water management. By implementing green infrastructure and custom drainage systems, the project aims to ease the burden on the city’s drainage system, manage runoff, and reduce localized flooding, enhancing neighborhoods. These transformed lots will also serve as small parks, enriching community green spaces.

Beyond environmental benefits, both projects set a new standard for urban water management and serve as educational and recreational centers, engaging residents with nature and sustainable practices.

The Stormwater Lots Project (Dana Brown & Associates), managed with NORA, uses green solutions to address poststorm infrastructure strain and serves as community spaces.

Active community engagement is essential for nurturing pride and a sense of ownership among neighborhood residents, particularly in large-scale projects. As green infrastructure initiatives expand, meaningful community consultation becomes central to addressing potential concerns and minimize opposition. Collaborative efforts between various stakeholders can help foster broader public sustainable development goals.

Gentilly has faced significant environmental challenges due to historical flooding, exacerbated by subsidence and aging drainage infrastructure. Both projects reimagine community spaces to mitigate anticipated flooding through a resilience lens.

Climate change effects are expected to increase the frequency and severity of flooding in New Orleans. Both projects are designed to anticipate and mitigate these risks through innovative engineering and multi-functional nature-based solutions.

Though significantly different in scale, both projects use nature-based design principles to enhance groundwater infiltration, improve regional water quality, and reduce subsidence while supporting the growth of native plants and wildlife.

This story is about working together on small issues to address large-scale urban issues.

RENEWING A CITY’S CANOPY

Sustaining Our Urban Landscape (SOUL), a nonprofit in New Orleans, Louisiana, goes beyond tree planting by embracing a strategy of education, advocacy, and community engagement. Through their Community Forestry Project, SOUL strategically plants large, native trees to tackle challenges like flooding, subsidence, and public health. Their educational series underscores the significance of urban trees, engaging a diverse audience of community partners, professionals, and students.

SOUL advocates for a no-net-loss tree policy, actively protecting trees on both public and private property. Their volunteer programs draw participants from around the country, offering hands-on opportunities to contribute to New Orleans’ urban forest by

planting trees in clusters. This approach supports reforestation efforts while promoting a sense of community and provides a meaningful way for volunteers to make a positive impact.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, New Orleans lost over 200,000 trees to polluted, brackish floodwaters and powerful winds. Despite ongoing recovery efforts, the city’s current tree canopy covers just 18.5% of its area. Understanding the fundamental role of a healthy tree canopy in enhancing climate resilience, SOUL partnered with landscape architects at Spackman Mossop Michaels (SMM) to develop the New Orleans Reforestation Plan. The goal is to bring every neighborhood up to a minimum of 10% canopy coverage by 2040. SOUL is actively implementing this plan with the support of volunteers.

Operating as an opt-out program, staff and volunteers navigate numerous conversations about trust and intention with local residents. The nature of the work also brings together people eager to engage in informal discussions about challenges and potential actions in neighborhoods

Formal outreach initiatives involve engaging with professionals, city employees, and community members through roundtable meetings and public forums, gathering valuable feedback on reforestation challenges and effective strategies.

These collaboration efforts are accompanied by rigorous research, including satellite data analysis, to make informed planting decisions and track maintenance and overall coverage. In addition, SOUL works with arborists and landscape architecture firms to tailor their approach to the unique conditions of New Orleans

SOUL’s multifaceted approach aims to replenish the city’s green cover and foster a deeper understanding of the profound impact trees have on urban communities, planting a healthier and more resilient future for New Orleans.

Our cities are changing. Environmental stressors are at the heart of this transformation, shaping public health challenges and contributing to hostile social dynamics. Longer, more intense heat waves exemplify this shift, fueled by the welldocumented urban heat island effect in densely populated areas.

The traditional urban landscape, characterized by concentrated structures, non-reflective surfaces, and limited greenery, contributes to elevated temperatures and an intensified urban heat island effect. This, in turn, impacts public health and human behavior. The effects go beyond mere discomfort; they manifest as serious health hazards such as respiratory problems, exhaustion, and heat strokes.

Additionally, there is a notable increase in aggression and violence.

blood pressure, which can escalate anger and violence. Moreover, noise pollution in urban areas further aggravates violent tendencies, with similar studies linking higher crime rates to increased noise levels.

Cities can address these challenges by prioritizing green infrastructure, such as parks and tree-lined streets, to reduce noise, pollution, and heat. Incorporating cool pavement technologies and promoting public and active transportation can also help lower pollution and health risks.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Seasonal Patterns in Criminal Victimization Trends, U.S. DOJ, 2014.

A report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics highlights a seasonal rise in violent crimes, especially during the summer months. Hot weather raises body temperature, heart rate, and

Developing emergency plans and raising awareness are integral to creating safer urban environments. Interdisciplinary efforts to educate communities and policymakers are essential, especially in formerly red-lined areas where minorities are the majority. These communities often lack green spaces and face higher pollution levels, which worsen health impacts. Addressing these issues with effective mitigation strategies is vital as environmental challenges continue to escalate.

SOUL, New Orleans, LA, 2022. New Orleans Reforestation Plan. ISeeChange, & New Orleans Health Department. (2024). Diagram of a heat mapping model showing local temperature differences of up to 18°, overlayed on 2023 census data on median incomes and race from hotter and cooler neighborhoods in New Orleans.

$5,000

Neighborhoods

Neighborhoods

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

SPATIAL MAPPING

This map shows that when an area has multiple issues that overlap, it makes each issue worse.

TOXIC

A percentile based on the average annual chemical concentrations in air weighted by the toxicity of each chemical.

91st PERCENTILE

Site: Bywater Neighborhood, New Orleans Location of the Crescent Park case study.

95th PERCENTILE

A percentile based on housing units built before 1960, indicating potential lead exposure.

Relative heat severity hot spots, categorized by the Jenks Natural Breaks method, revealing the health hazards posed by heat, particularly for vulnerable populations.

EJSCREEN: Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

CRESCENT PARK

CITY PARKS

MITIGATE STRESSORS

Crescent Park, a 1.4-mile linear park in New Orleans, transforms a former maritime/industrial brownfield into a 20-acre green space with native landscaping, walking, jogging, and biking paths, picnic areas, a dog park, and the adaptive reuse of two industrial wharves along the Mississippi River.

Emerging from the Reinventing the Crescent Development plan after Hurricane Katrina, Crescent Park was developed through collaborations with design firms EskewDumezRipple and Hargreaves Associates, reconnecting the city with its historic riverfront.

The park’s resulting soil remediation and sustainable landscaping make it an important environmental asset. It mitigates the urban heat island effect with shaded areas and vegetated spaces that help reduce heat stress and improve air quality. Positioned partly on higher ground within the levee system and by incorporating permeable surfaces and rainwater harvesting, Crescent Park also lowers flood risks

and enhances water quality. Despite its industrial past and current usage that causes noise and light pollution, the park’s natural features and levee buffer work to reduce sensory pollution.

Community engagement was core to Crescent Park’s development. The design team worked with a steering committee stakeholders group and held over a dozen forums, integrating neighborhood feedback. The final design received positive community feedback, and the development process was publicly documented.

Beyond its environmental benefits, Crescent Park is a vibrant public space that offers recreational opportunities and serves as a hub for community events and artistic expression. It has also become a refuge for displaced residents seeking solace from environmental stressors. This unintended sanctuary park highlights broader issues, such as housing insecurity and economic disparities, while cultivating local engagement.

Crescent Park in New Orleans, a 1.4-mile linear park along the Mississippi River, addresses social environmental, and public health challenges. It features sustainable design principles to manage water, reduce pollution, and mitigate heat, while sustaining social cohesion and supporting economic growth.

The larger Reinventing the Crescent Development plan integrates sustainable landscape practices and modern urban planning within the levee system. This approach reconnects the city with existing infrastructure while preserving the levee flood wall.

Crescent Park addresses urban heat island hot spots and resulting heat and respiratory health impacts. Through the addition of shaded areas, vegetated spaces, the park aims to lower temperatures and mitigates risk in the surrounding areas.

Lead paint in nearby areas poses local risks as it can leach into soil and water from deteriorating surfaces. Although the park didn’t directly remediate the site, its new landscaping with fresh soil and plantings enables safer community use.

The former industrial site still faces issues with persistent freight train noise. The park’s natural landscapes, quiet areas, and existing levee buffer create a more peaceful environment, reducing the negative impacts of urban sensory stressors.

Adaptive reuse and new construction can merge to reimagine existing spaces, bridge gaps, and advance social justice.

ITALY PAVILION MILAN EXPO

INTEGRATED CLIMATE MITIGATION

Palazzo Italia by Nemesi addresses Milan’s air quality issues caused by its location in the Po Valley, where its surrounding mountains trap pollutants in a basin-like effect. The building uses photocatalytic cement to clean the air and features insulating materials and reflective surfaces to help reduce energy use and control temperature changes.

A notable feature is the use of over 2,000 tons of i.active Biodynamic cement. This material combats air pollution by using sunlight to drive chemical reactions that convert harmful nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulfur dioxide (SO₂) into inert salts.

With this approach, the building aims to reduce local emissions by up to 75%, enhancing air quality for its occupants in a city where pollution often exceeds European limits due to industrial activities.

The building’s envelope is designed to improve energy efficiency and mitigate the prominent urban heat island effect. Solar panels on the roof further cut reliance on external energy sources, achieving a 40% reduction in energy use and approaching near-zero energy consumption.

Palazzo Italia also features green infrastructure such as permeable pavements, green roofs, and rainwater harvesting systems. These elements act as natural filters, reducing stormwater runoff and pollution while supporting local biodiversity.

The project leveraged its financial capacity to use new technologies, serving as a proof of concept for mitigating environmental stressors, offering an idea that can be scaled and applied more broadly.

Palazzo Italia addresses local environmental challenges through its use of innovative materials and energy-efficient design. The building’s use of i.active Biodynamic concrete actively reduces emissions, while its integrated systems reduce water runoff and lower energy consumption.

Milan’s climate extremes, with hot summers and freezing winters, drive up the need for indoor temperature control but also have notable consequences for air quality and intensified urban heat island effects within the city.

Milan, like many industrialized cities, contends with air pollution primarily stemming from traffic congestion and industrial emissions, exacerbating respiratory health concerns and environmental degradation.

In Milan, the landscape is dominated by concrete and asphalt. Preserving green spaces and mitigating pollution runoff are imperative to prevent soil degradation, loss of biodiversity, and water contamination.

E Q U I T Y

ASSESSMENT SUBMETRICS

POPULATION SIZE

POPULATION DENSITY

POPULATION DISTRIBUTION

POPULATION GROWTH RATE

AGE STRUCTURE

MIGRATION TRENDS

URBANIZATION

HOUSING STOCK

“The census is the spine of democracy; without it, the public lacks the true knowledge of itself.”

- Kenneth Prewitt

Understanding and leveraging data about a specific quantity of people offers a practical lens to understand societal dynamics and support resilient communities. Looking into demographic conditions such as population size, migration patterns, age distributions, and territorial dynamics offers broader insights into the evolving fabric of communities and their adaptive capacities. This comprehensive approach isn’t just about statistical analysis; it forms the cornerstone of informed decision-making, guiding policies and resource allocations to address specific societal needs more effectively.

Moreover, this data plays a pivotal role in uncovering underlying challenges and disparities, especially in the aftermath of crises or natural disasters. Similar to how post-disaster assessments reveal systemic inequalities, demographic analyses provide a complete view of vulnerabilities, enabling betterinformed design and implementation of targeted interventions for equitable disaster preparedness and recovery.

Reframing data as a catalyst for educated action and inclusive planning turns challenges into opportunities for innovation and community improvement. Integrating sustainable and resilient design principles strengthens spaces against environmental pressures while supporting holistic well-being and inclusivity, ensuring built environments evolve in harmony with the diverse needs and dynamics of the populations they serve.

To understand populations, breakdown what factors shape Quantities of People .

The total number of individuals residing in a specific geographic area, region, or country at a particular point in time to understand need and resource allocation.

The number of people per unit area, such as square kilometers or square miles, to analyze crowding levels, urbanization trends, and environmental impacts.

The spatial arrangement of people within a specific geographic area, indicating patterns of urbanization, rural depopulation, and the concentration of populations.

The percentage change in population over a specified period, considering births, deaths, immigration, and emigration rates, crucial for predicting future trends.

The proportion of different age cohorts within a population, including children, workingage adults, and elderly people, influencing healthcare, workforce, and support systems.

Patterns of movement of people into and out of an area, including immigration, emigration, and internal migration, influencing diversity, labor markets, and cohesion.

The extent of infrastructure and building development in an area, indicating its level of urban versus rural characteristics, as well as development patterns and impacts.

The number and variety of residential properties in an area, including single-family homes and apartments, reflecting availability, condition, diversity, and affordability.

This story is about unraveling connected issues through a local perspective.

While planting trees in the Lower Ninth Ward, a conversation with a neighbor, an African American man living in a neglected area against the Industrial Canal, uncovered deeper societal issues. This neighbor’s concerns about a concealed fire hydrant revealed broader problems, such as neglected stormwater management projects and disparities in city-wide maintenance, particularly in areas historically populated by communities of color. These issues reflect deeper systemic inequities related to race and socioeconomic status, demonstrating uneven access to essential services.

Addressing these disparities requires a government that accurately represents and responds to the needs of its citizens. However, the dialogue underscored a troubling trend: low voter turnout and reduced civic influence. With only 27% participating in the 2023 governor’s election compared to 36% in the primary elections in Orleans Parish,

alongside demographic disparities in voter engagement, it becomes clear that marginalized communities, like those in the Lower Ninth Ward, may lack adequate representation.

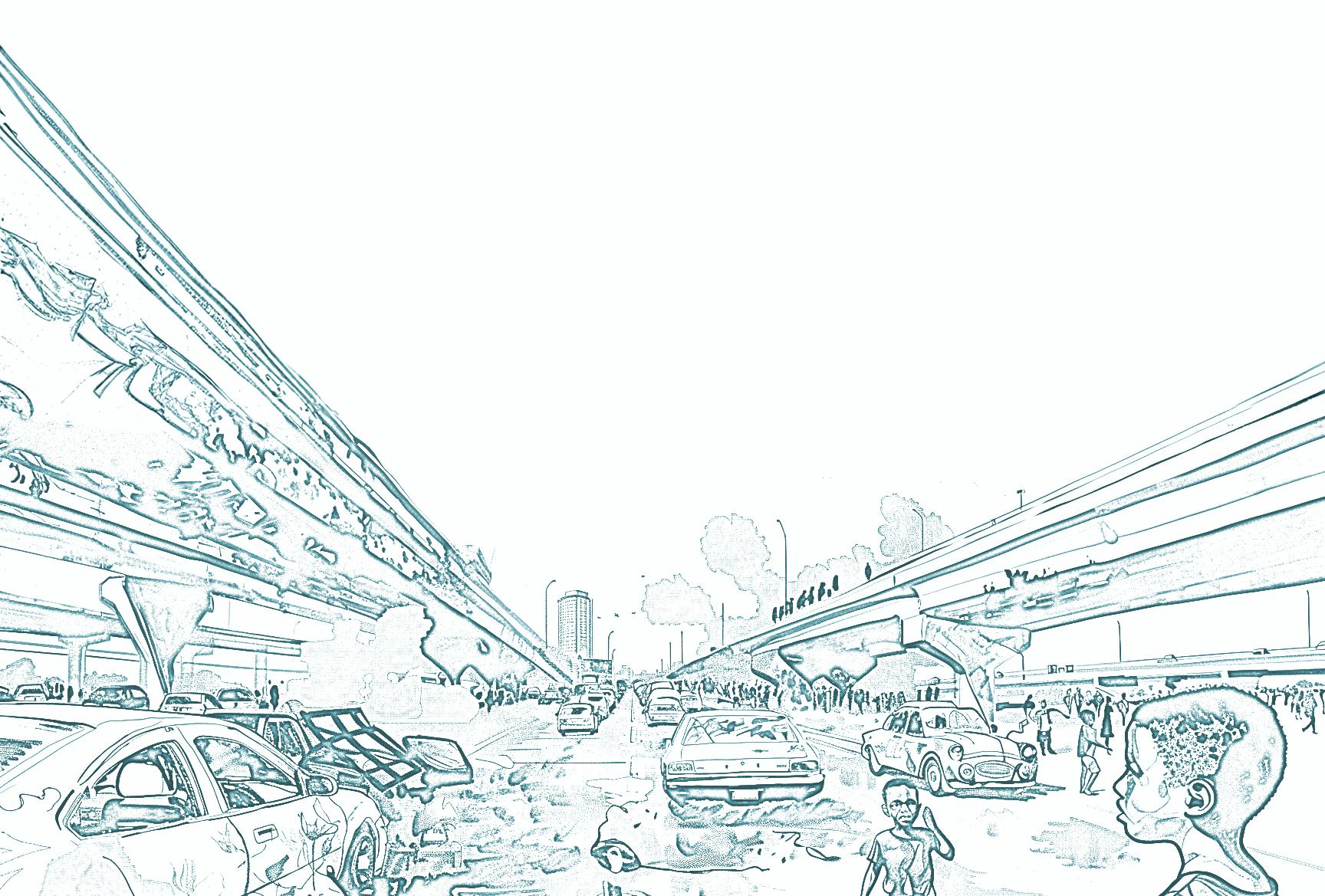

This lack of representation can lead to current outcomes like the Industrial Canal expansion project, a 13-year plan involving the widening of locks, replacement of bridges, and implementation of floodwater management strategies with bypass channels. Despite these efforts to address environmental concerns, such as emissions and increased flooding risks, the neighbor’s skepticism stems from a history of unfulfilled promises and fears of displacement. His dubiety reflects a deep-seated distrust in the government’s commitment to genuinely addressing the needs of his community.

This situation underscores the need for transparency and meaningful community engagement, ensuring that communities are well-informed decision-makers. The lived experiences voiced by residents like this neighbor highlight the importance of involving affected communities in the planning process to build trust and ensure that development efforts address local needs. By tackling demographic disparities and facilitating inclusive development, collaborative efforts can achieve more equitable and effective outcomes across diverse populations.

What is Redlining? A discriminatory practice where neighborhoods were color-coded to indicate their risk level for mortgage loans and insurance, consistently marking areas with minority residents as “high-risk.” This practice has contributed to the racial segregation and disparities seen today.

1619

Arrival of enslaved Africans in the U.S., start of systemic racism.

1865

Civil War ends, but Jim Crow laws enforce segregation.

1917-1940s

Great Migration highlights regional disparities.

1787

Three-Fifths Compromise at the Constitutional Convention

1896

Plessy v. Ferguson officially legalizes segregation.

1960s-Present

Industrial zoning practices target Black neighborhoods.

1980s-Present

War on Drugs incarcerations target Black communities.

1930-1960s

Redlining legally hinders Black American progress.

ROWHOUSESNEGRO

HIGH CONCENTRATION OF FOREIGNERS

NEGROS SCATTERED FORECLOSURES

NEGROS CROWDING WHITE MEN SLUMS SLUMS AREAISRUNDOWN

WORKERSSKILLED

TOUGHEST SECTIONOFTHECITY

OBSOLESCENCE

UNDESIRABLE

HOMESUNIMPROVED FACTORIES

NEAR EMPLOYMENTINDUSTRIAL AREPEOPLEFRUGAL WORKERSFACTORY

NO THREAT OF INFILTRATION

ORIENTALS OFPRESENCE POPULATIONCOLOREDCONGESTION UNSKILLED LABOR

HOMESSCATTERED WITHOUTPLANNING

VACANT LOTS

NEGROSAGAINSTRESTRICTED

ALLTYPES OFNEGROS

AGEDANDOBSOLETESTRUCTURES

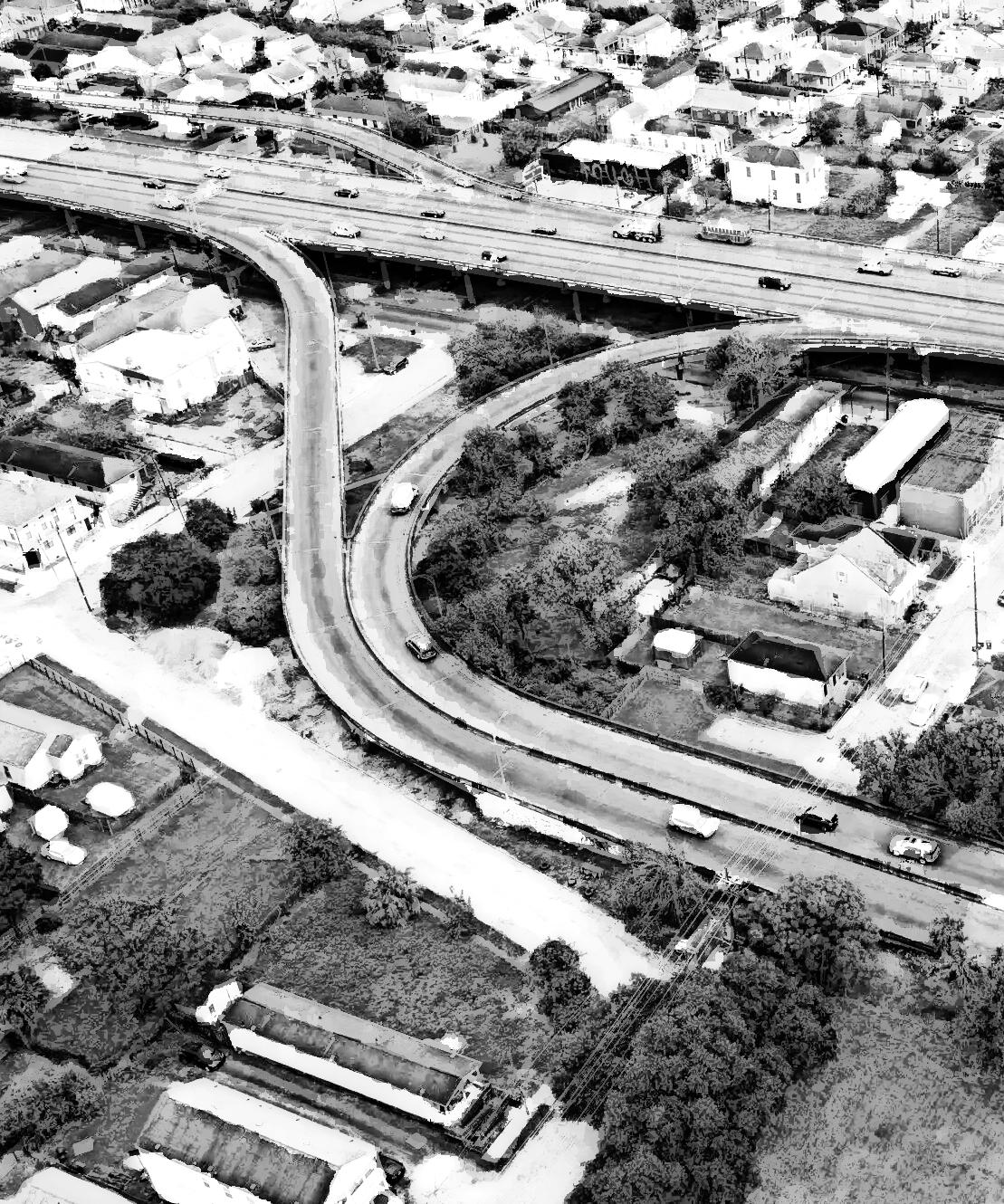

Before Hurricane Katrina struck on August 29, 2005, the Lower Ninth Ward was a relatively unknown working-class neighborhood. The hurricane, accompanied by major levee breaches, caused destructive flooding, transforming the Lower Ninth Ward into a symbol of converging destructive forces: the storm, geographical vulnerability, government neglect, urban poverty, and racial polarization.

This devastation further illuminated the neighborhood’s long-standing issues, including its shift to a predominantly African American community by the mid-20th century, driven by segregation, economic disparity, and disinvestment. The ward’s isolation from central New Orleans, both literal and figurative, was starkly exposed, drawing national attention to its precarious vulnerabilities.

The resulting displacement exposed the intersectionality of challenges faced by vulnerable communities, where factors like flooding, heat, air quality, race, language, age, and disabilities interweave to heighten susceptibility.

These challenges are further intensified by climate change, economic inequality, and systemic injustices. Effective antidisplacement strategies must involve substantial financial investment, the formation of robust coalitions, and strengthened collaboration among stakeholders in historically impacted areas, ensuring a comprehensive response to these multifaceted issues.

Designers can play a role in minimizing related displacement challenges by understanding the overlap of disasters, vulnerability, and racial injustice. This includes promoting sustainable design practices, raising historical awareness, and advocating for comprehensive rebuild efforts beyond constructing new buildings.

Success also depends on a holistic approach that prioritizes accessible services, public transportation, flood protection, and support for displaced residents seeking to return home. Only through such comprehensive efforts can the multifaceted challenges faced by the community be effectively addressed.

Throughout much of the 20th century, the federal government, through the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), used redlining to grade neighborhoods from A ("Best") to D ("Hazardous"), predominantly rating neighborhoods of color as C or D. This discriminatory practice systematically stifled economic growth, contributing to long-term disinvestment. These

factors, along with shifting population dynamics, provide context for the contrasting development of adjacent neighborhoods, Broadmoor and Gert Town. Michael Robinson, a community organizer involved in public housing projects, and Pamela Waldron-Moore, a Professor of Political Science at Xavier University, shed light on other factors exacerbating these disparities.

Gert Town Population: 6,621

Density: 6,769/sq mi.

Broadmoor Population: 5,212 Density: 11,611/sq mi. Minority: 63%

Site: Location of the Rosa F. Keller Library and Community Center case study.

C I TY / Two Neighborhoods

Lead Organizer

Jericho Road Episcopal Housing

DYNAMICS

INTERNAL COMMUNITY CHALLENGES

Broadmoor, historically a mix of middle to high-income professionals, leveraged community mobilization in their postKatrina recovery, supported by Carnegie and Kellogg Foundations’ funds and guided by a Harvard plan. Michael spoke to a vital campaign’s unifying impact.

“They used [the Green Dot campaign] as an organizing tool to say, ‘Hey, look, they’re trying to tear down our neighborhood.’”

The Green Dot campaign, sparked by opposition to the city’s plan to convert Broadmoor into green space, unified residents. Broadmoor also had an internal tax-funded development organization, allowing for a full-time staff and supporting initiatives like the revitalization of the Keller Library.

In contrast, Gert Town, historically a diverse low-income neighborhood, faced worsening challenges due to conflicts between internal nonprofits and Xavier University’s expansion, leading to significant displacement after Katrina, as Pamela described.

Professor of Political Science

Xavier University

“There was a perception from Gert Town that they were separate. The castle [Xavier University] is on one side, separated by this moat, and the poor people are on the other side looking for stuff. A lot of that played into who got left behind.”

The lack of resources, property acquisition, and organizational means led to unexpected migration. This struggle, marked by depopulation, was worsened by the presence of a DDT plant and soil radiation.

“When you have industrial plants in communities, nearby workers find it’s easier to get employed there. While Broadmoor was getting money from big agencies, people in Gert Town took what they could from the chemical plant.”

Although adjacent to Broadmoor, Gert Town faced ongoing barriers that hindered its revitalization. This underscores the complexities of urban development and the need to address each neighborhood’s unique population dynamics.

ROSA F. KELLER LIBRARY AND COMMUNITY CENTER

RESILIENCE THROUGH UNITY

Broadmoor’s Rosa F. Keller Library and Community Center in New Orleans is a powerful symbol of resilience and community-driven urban development in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. The neighborhood’s journey to recovery and renewal is a testament to the strength and determination of its residents.

After Katrina, Broadmoor faced devastating impacts, with over two feet of water flooding the 1993 slab-on-grade library addition that housed the book stacks. The city’s “green dot” plan proposed converting, predominantly Black, neighborhoods into stormwater management sites, effectively displacing residents and leaving their futures uncertain. However, the community of Broadmoor, led by the Improvement Association, refused to accept this outcome and took a stand.

The community united, securing funding and resources to rebuild. Through a series of workshops, they worked with EskewDumezRipple to envision the Rosa F. Keller Library and Community Center as more than just a place for books but as a cultural and educational hub that would anchor their renewed

sense of purpose and belonging. Completed in 2012, the facility reflects the neighborhood’s identity, blending the renovation of a historic 1917 residence with a new structure that embodies the community’s aspirations.

Sustainability is woven into the very fabric of the LEED-certified library, which features elements that manage stormwater, alleviating pressure on city infrastructure and supporting local ecosystems. The building stands as a beacon of what can be achieved when cultural heritage, sustainability, and community vision come together in the pursuit of collective well-being.

While the library serves as a model for addressing community needs and climate stressors, stakeholder engagement with Gert Town residents revealed that they don’t fully see it as their resource. While Broadmoor’s revitalization has been successful, neighborhoods like Gert Town still struggle with resource scarcity and underrepresentation. The Keller Library underscores the need for inclusive urban development, ensuring all neighborhoods have a voice in shaping the city’s future.

The Rosa F. Keller Library and Community Center in Broadmoor, New Orleans, embodies a communityoriented resilience project amidst demographic shifts and population challenges. The library symbolizes community unity, proactive local efforts, and challenges in revitalizing neighborhoods.

Broadmoor had significant demographic shifts between tracts, which emphasized the need for a central hub. This facility could have served a broader population by engaging with surrounding neighborhoods lacking sufficient density for resources, like Gert Town.

Both Broadmoor and Gert Town have seen a decline in population rates. Residents underscored the need to reinvest in valuable community resources to draw residents back to the area, with a particular focus on supporting Broadmoor residents.

Broadmoor’s flood risk highlighted migration patterns linked to natural disasters, community resources, and safety. This stressed the necessity of deliberate actions, including creating resource hubs and fostering trust and resilience through rebuild.

Community-driven revitalization leverages deep local insights to transform challenges into opportunities, allowing design to honor both legacy and evolving needs.

ST. PETER RESIDENTIAL, NEW ORLEANS

RESILIENCE BUILDS

RELIABILITY

St. Peter Residential, designed by EskewDumezRipple, stands as Louisiana’s first net-zero multifamily building. This 50-unit mixed-income residence in New Orleans offers affordable housing for veterans. Through passive design strategies and technologies, such as high-efficiency HVAC systems, smart lighting, and energy-efficient appliances, the building minimizes energy use.

The project strategically addresses concentrated housing needs among low-income families and veterans in urban settings. By offering affordable housing options that serve a wide boundary of people in need, St. Peter Residential contributes to equitable access to stable housing solutions across multiple neighborhoods.

St. Peter Residential features 450 solar panels and a battery array, developed with SBP and supported by a $1 million donation from Entergy. This renewable infrastructure ensured uninterrupted power during Hurricane Zeta in 2020 and Hurricane Ida in

2021, when the residence remained operational while the city experienced prolonged outages, providing a vital resource for surrounding communities.

This project has been cited as a proof-of-concept by initiatives like Together New Orleans (TNO)’s Community Lighthouses proposal that established microgrid hubs at religious institutions, enhancing the project’s credibility and setting a precedent for future developments that could ensure predictability and resilience.

Beyond its sustainability model, the project also serves a social purpose by providing housing for veterans, including single mothers who have returned from deployments in conflict zones like Iraq and Afghanistan. The residence offers amenities such as a wellness center, as well as communal and recreational spaces. These services reflect the project’s understanding of how diverse population needs can shape and inform building scale strategies.

Roof: 450 solar panels and battery arrays powering continuous operation.

St. Peter Residential is a 50-unit mixed-income residence in New Orleans, prioritizing veterans. Leading in sustainable design and social impact, it creates a creditable model for affordable housing with its net-zero energy consumption, resilient infrastructure, and targeted amenities.

In certain areas of New Orleans, low-income families and veteran populations face concentrated housing needs. This project strategically provides affordable housing to multiple neighborhoods to ensure equitable access to stable housing options.

With New Orleans’ urban setting in mind, this project prioritizes sustainability to mitigate environmental impacts in densely populated areas. By integrating renewable energy and minimizing energy demand, it contributes to healthier environments.

Recognizing New Orleans’ diverse demographics, this project prioritizes veterans returning from deployments, addressing overlooked community groupings. By offering targeted amenities, it improves residents’ quality of life across various life stages.

E Q U I T Y

IDENTIFY COMMUNITY SERVICE GAPS

ASSESSMENT SUBMETRICS

HEALTHCARE SERVICES

HEALTHY FOOD

PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION

PUBLIC SPACES

CULTURAL RESOURCES

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

QUALITY EDUCATION

LOCAL BUSINESSES

“The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

Unmet community needs are essential services or resources that are inadequately provided or entirely lacking within specific geographic areas or among particular demographic groups. These needs range from access to quality healthcare, affordable housing options, equitable educational opportunities, viable employment prospects, and essential social services to necessary infrastructure improvements. Recognizing and comprehensively understanding these unmet needs is essential for developing targeted interventions, policies, and programs aimed at improving overall community well-being and addressing systemic disparities that hinder progress and growth.

Understanding these multifaceted challenges requires a collaborative effort involving community stakeholders, policymakers, nonprofits, and businesses. By engaging in participatory research, data collection, and dialogue with affected communities, insights into the root causes and intricacies of identified unmet needs are revealed. This informed approach enables the development of strategic interventions that are not only responsive but also sustainable and tailored to the unique contexts of each individual community.

Moreover, addressing unmet community needs goes beyond short-term fixes; it requires long-term planning, investment, and commitment to holistic, equitable development. Prioritizing these needs in policy agendas, allocating resources wisely, and fostering collaborative partnerships across sectors help build robust systems for a more just and thriving society.

To create opportunities, identify an area’s

.

Facilities like hospitals and basic services such as pharmacies and clinics are located more than a mile away in urban areas or beyond a ten-mile radius in rural areas.

Supermarkets or large grocery stores offering affordable and healthy food options are located more than a mile away in urban areas or beyond a ten-mile radius in rural areas.

Urbanization, poverty, transit cost burden, availability of transit services, travel times to essential services, digital access, and safety factors have a high cumulative impact.

Accessible small spaces are located more than a 5-minute walk, larger spaces are more than a 10-minute walk. There’s a lack of city spaces for organized recreation and events.

Permanent institutions, facilities, or events that contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage, traditions, arts, history, and diversity are located more than two miles away.

Households in a census tract are making less than 80% of the area median family income (AMFI) by region and spending more than 30% of that income on housing.

Educational facilities offering comprehensive and quality education are located more than two miles away in urban areas or beyond a fifteen-mile radius in rural areas.

Businesses such as gas stations, laundromats, retail stores, banks, and post offices are located more than a mile away in urban areas or beyond a ten-mile radius in rural areas.

This is a story about urban agriculture’s role in combating food deserts and historical inequities.

CULTIVATING FOOD EQUITY

In Central City, Dimitri Celis, Program Manager at Recirculating Farms, is a steward for sustainable agriculture.

The seemingly lively urban landscape harbors a longstanding void, a void created by the absence of accessible grocery stores, replaced by corner stores offering processed and unhealthy food. However, their team challenges the label of Central City as a “food desert,” unraveling the intentional disinvestment and historical policies that have shaped the community.

“There’s a growing narrative within the food justice scene that desert implies a naturally occurring thing, but it’s not just by chance that there’s no grocery store in Central City. This happened because of policies that the government-sanctioned back in the 40s from the FHA and the redlining maps and the VA and all the racist loaning practices.”

Program Director Recirculating Farms

“We’re trying to let people know that this is why we grow here. It’s not just because it’s a food desert, but because it’s intentionally not being invested in.”

Past initiatives aimed at addressing food deserts have thought about using existing corner stores rather than building new grocery stores. However, challenges arise because many stores struggle to stock items like produce due to high turnover rates and the risk of lost profits. Food deserts are not just about access to food but also about access to affordable food.

“One thing that we’ve talked about is, what does it mean to have access to affordable food? Affordable food is not just subsidizing the cost down so people can afford it. Affordable food also means paying people a living wage so they can buy the food that we’re producing too.”

This connects to the issue of food apartheids, a systemic segregation that limits access to nutritious food for many communities. In New Orleans, where thousands of vacant lots could expand urban equity, questions around land use, ownership, and historical disinvestment persist.

Recirculating Farms has faced barriers, including relocation after eviction. They sought long-term land tenure through the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority (NORA) Growing Green program, which offers an option to purchase a lot after a three-year lease. While the program supports community projects, market pricing is a hurdle, with

their NORA lot appraised at nearly half of the nonprofit’s operating budget.

Negotiations for a lower price based on their nonprofit status and the land’s use as a community garden have been unsuccessful, mirrored in their interest in purchasing a private lot between their currently leased lots.

“We should be flipping the script on what it means to own property.”

Dimitri argues that community projects should be treated differently from standard developments, emphasizing the need to quantify ecological services and adopt more equitable practices that aren’t driven by market pricing.

Maybe development, development, development is not the route that we should take, especially if the development is not sustainable development.”

Deserts are naturally occurring, but the disparities present today are not. Intentional deserts, areas lacking access to essential resources like food, financial services, and healthcare, are deeply rooted in historical government policies that have entrenched systemic disadvantages.

For instance, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in the 1930s, along with the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), implemented discriminatory practices that enforced racial segregation and redlining, systematically denying loans and services to minority communities, particularly in Black neighborhoods. This disinvestment led to concentrated poverty, dilapidated infrastructure, and a lack of investment in community resources, creating lasting social and economic disparities that persist today.

Similarly, after World War II, the Veterans Administration (VA) continued discriminatory loan practices by denying housing benefits to minority veterans under the GI Bill. These policies severely limited opportunities for upward mobility and wealth accumulation, further entrenching the conditions that define modern-

day deserts, characterized by scarce economic resources and opportunities.

The historical injustices that persist today reflect a systemic landscape marked by widespread food insecurity, poor health outcomes, and limited access to employment, quality education, and green spaces. To effectively disrupt cycles of poverty and inequality, communities can prioritize investments in youth. By providing educational resources, mentorship, and safe recreational spaces, communities can help prevent violence and reduce incarceration rates, issues often worsened by systemic mistreatment and a lack of local opportunities.

An intersectional approach reveals how these disparities uniquely impact vulnerable populations based on factors such as race, socioeconomic status, and geographic location. Recognizing deserts as the result of systemic choices highlights the urgent need for comprehensive, tailored solutions. Reframing intersectional disadvantages as shared challenges that connect diverse groups fosters collective strengths and promotes equity and inclusivity, ultimately benefiting all members of society.

This map shows that intentional resource deserts are often linked.

NEW ORLEANS’ SCHOOL AVERAGE GRADE

Louisiana Department of Education 2023 annual A-F letter grades: 69.9/150 - C average.

Treme Neighborhood

Site

GRADE

Site: Treme Neighborhood, New Orleans Location of the Edible Schoolyard case study.

When investigating unmet community needs, the process begins with identifying critical service gaps. In Central City, education is a significant concern due to a limited number of schools and inconsistent quality. Disinvested areas often face multiple overlapping issues. Those areas may struggle with educational quality, lack

accessible green spaces essential for physical and mental health, and experience food deserts due to the absence of stores offering affordable, healthy food for comprehensive shopping. Addressing these interconnected issues holistically allows for a better understanding and approach to broader challenges.

After identifying interconnected needs, addressing them requires determining and assessing relevant impact opportunities. This involves evaluating how each identified issue further affects various aspects of community well-being, such as health, economic stability, and social cohesion, to prioritize interventions.

In New Orleans, families rank schools through a charter system and are placed based on availability, which can result in long commutes. With 26% of students attending “D” rated schools, there’s a need for educational reforms and supplemental opportunities.

Neighborhoods in New Orleans face food desert challenges, due to limited access to affordable, nutritious options. Integrating food education into curriculums can help address this issue and promote food security among low-income students.

Central City in New Orleans grapples with extensive impermeable surface coverage, surpassing 71%, resulting in a scarcity of green spaces. Inclusive outdoor learning and recreation spaces within walking distance are needed for safe youth development.

This story is about promoting inclusive education to create equitable opportunities.

“It’s all about offering opportunities and access. Every student, regardless of barriers, should have access to holistic and high-quality education.”

Charlotte Steele, Director of Edible Schoolyard New Orleans, is dedicated to building food connections through outdoor learning environments in FirstLine Schools. The program serves a diverse demographic, mainly comprised of Black and Spanishspeaking students, many of whom face poverty and barriers to food security. The program views its gardens as community resources, sharing yields to address the unmet community needs.

New Orleans students tend to have strong food identities from growing up cooking with their families, and hearing about local culinary legends. Edible Schoolyard’s programming offers diverse access and shapes student paths and identities.

Director

Edible Schoolyard New Orleans A Signature Program of FirstLine Schools

“Not only are we providing the seeds of experiences that help students build their identities and relationships with food in the natural world, we’re also supporting their academic achievement. There are many ways we integrate academics into our classes, but life skills and social-emotional learning are at the forefront of what we do.”

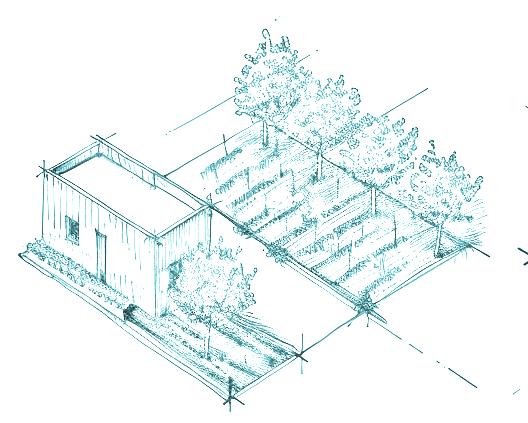

Edible Schoolyard worked with EskewDumezRipple to transform Phillis Wheatley Community School’s teaching garden space. The project, constructed by unCommon Construction, aligns with the organization’s values of “beauty is the language of caring.”

“The coolest part of having built a physical structure is that its legacy is indefinite. There are just so many students who will thrive from having that space to make academic connections, learn through a social-emotional lens, and build their gardening and cooking skills.”

Engagement with teachers was essential in guiding the design of the outdoor classrooms. As key figures who have a close relationship with the space, their input brought intentionality to the project, emphasizing multifunctional spaces for activities, planning areas for plant cultivation, and focusing on community food production.

Seeking to educate the whole child in mind, body, and spirit, Edible Schoolyard’s classrooms foster holistic learning experiences that integrate academic achievement and social-emotional learning, promoting comprehensive education for all students.

By integrating food education and healthy eating habits into their curriculum, Edible Schoolyard’s classroom addresses the lack of accessible healthy food options within urban areas and promotes food security among low-income students.

Through their inclusive outdoor learning environments and community programs, Edible Schoolyard creates visually open spaces catering to the need of youth to have areas for organized programs and access to safe green spaces within walking distance.

“There are a lot of visitors that walk up and down our street, and they stop in their tracks. They understand that the students who go to our school are extremely important, valuable, and smart, and they see them learning in a comfortable, curiosity-inspiring space.”

- CHARLOTTE STEELE

Integrating food gardens and green spaces into community planning and design helps address health concerns while aligning with larger societal goals, including economic, social, and environmental sustainability. This approach recognizes the multifaceted benefits of such initiatives and their potential to dismantle systemic barriers while promoting community resilience.

between community gardens and health, demonstrates that increased access to healthy food, through community gardens, is associated with higher fruit and vegetable intake, positive psychosocial outcomes, and improved community engagement.

“Community Gardens and Their Effects on Diet, Health, Psychosocial, and Community Outcomes,” BMC Public Health, 2022.

Urban communities, particularly those in food deserts, face significant challenges with food insecurity. Whether initiated by community groups or part of larger urban farming projects, food gardens help mitigate this issue. Research, including a study on the connection

Edible

Furthermore, food gardens in educational settings can offer more cognitive benefits. Exposure to green environments has been linked to improved focus, motivation, and engagement among students. Hands-on experiences reinforce classroom learning while providing valuable lessons about plant life cycles, environmental science, and sustainable practices. Active involvement in gardening and healthy eating contributes to a more engaging and effective educational experience.

Local community gardens do more than grow food; they foster social interaction, community building, and cultural exchange. Increased vegetable intake is linked to both better access and the connections formed among users, enhancing social cohesion and neighborhood ties.

HEALTH & EQUITY

“Associations Between Nature Exposure and Health,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021.

From an environmental perspective, urban farming and green spaces contribute to environmental stewardship throughout a community. Practices such as composting, water conservation, and organic gardening techniques are commonly integrated, promoting eco-friendly behaviors and reducing environmental impact. Green spaces also provide essential ecosystem services, including air quality improvement, temperature regulation, and natural disaster mitigation, directly impacting community health and well-being.

Nature in urban environments has been linked to reduced stress, anxiety, and depression levels. Spending time in nature enhances cognitive functioning, attention, and overall well-being. These spaces offer opportunities for relaxation, physical activity, and connection to nature, contributing to improved mental health outcomes across age groups.

1/7 PEOPLE

STRUGGLE TO PROVIDE HEALTHY MEALS FOR THEMSELVES

Despite the evident benefits, equity challenges related to access exist. Low-income and minority communities often face limited access to quality green spaces and healthy food options, contributing to health disparities. Recognizing and addressing this requires intentional planning, resource allocation, and community engagement to ensure equitable access to these resources.

Through implementation and advocacy, designers can help advance the success and sustainability of food gardens and green spaces in urban environments. Participatory design processes, community engagement, and collaboration with local stakeholders are integral to creating inclusive environments. Incorporating design elements like accessible pathways, multi-purpose spaces, educational and wayfinding signage, and cultural relevance enhances the impact of these community spaces.

STUDENTS REPORT EATING LEAFY GREENS

OVER 200K 4X

CHILDREN LIVE WITH FOOD INSECURITY

MORE OFTEN THAN STUDENTS ACROSS THE UNITED STATES

Feeding Louisiana, Current Hunger Facts and Statistics for Louisiana, 2024.

Casa Adelante 2060 Folsom, in San Francisco’s Mission District, tackles community challenges through a joint venture between Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation (TNDC) and Mission Economic Development Agency (MEDA). Designed by Mithun in collaboration with Y.A. Studio, the project focuses on housing Latinx families, providing space for organizations serving Latinx youth, and featuring community art.

The project was funded by a culmination of Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits, tax-exempt bonds, and investments from the Mayor’s Office, Bank of America, and the Federal Home Loan Bank. With 127 permanently affordable units, the project takes on housing insecurity in a district where nearly half of households struggle with high housing costs.

The success of Casa Adelante is due to strong partnerships. The Felton Institute offers affordable childcare, the Good Samaritan Family Resource Center

provides family support services, and PODER works on environmental justice and immigrant rights. Larkin Street Youth Services supports homeless and at-risk youth, while HOMEY empowers youth through mentorship. First Exposures and Youth Speaks share a space for youth storytelling, combining photography and arts education.

Casa Adelante prioritizes education, offering on-site childcare, afterschool programs, and counseling. HOMEY, First Exposures, and Youth Speaks also play core roles in these efforts. The project integrates urban gardens and community-supported agriculture to address food insecurity. On-site healthcare services and counseling address residents’ physical and mental health needs.

Casa Adelante 2060 Folsom represents a shift in affordable housing development. It integrates services to manage various unmet community needs and exemplifies the impact of affordable housing led by and for people of color.

Casa Adelante 2060 Folsom is an affordable housing development in San Francisco’s Mission District. To support education, culture, healthcare, and food security, the project offers on-site childcare, public art, urban gardens, and healthcare services, marking a collaborative and holistic approach.

San Francisco’s Mission District grapples with acute housing insecurity, with nearly half of households facing high housing costs. This project offers 127 permanently affordable units, providing long-term stability and addressing systemic barriers.

Food insecurity is prevalent in neighborhoods like the Mission District. This project combats this issue with urban gardens and community-supported agriculture initiatives, ensuring residents have access to nutritious food and social connections. THIS IS AN AFFORDABLE HOUSING PROJECT IN SAN FRANCISCO, CA THAT, OFFERS HOLISTIC SUPPORT

In underserved communities like the Mission District, access to healthcare is often limited. This project addresses this gap by providing on-site healthcare services, including counseling, to address residents’ physical and mental health needs.

Many residents in underserved communities face barriers to quality education and opportunity. This project prioritizes education as a pathway to empowerment by providing on-site childcare facilities, after-school programs, and counseling services.

There may not be a singular “best” equity solution, but unmet needs can be addressed by harnessing the synergies of collaboration.

This is a story about losing the sense of community amidst local changes and challenges.

OBSERVED COMMUNITY CHANGES

Alison Toussaint-LeBeaux, a proud New Orleans native and custodian of family-owned properties, intimately understands Treme’s transformation over the years. Once hailed as the Mecca of music, Treme holds cherished memories for Alison, especially the vibrant sounds of second lines and the close-knit community spirit that defined her children’s early years. Like many neighborhoods, Treme has experienced pivotal moments that signify a changing landscape, often resulting in population shifts in urban areas.

ALISON TOUSSAINT-LEBEAUX

Community Stakeholder

Property Owner

“We were trying to teach our kids how to ride a bike. They couldn’t ride on that street, so we used to go to Armstrong Park. Then they started locking the gates to the park from the one entrance we had. After a while, it felt unwelcoming. The things that we had at our disposal, the natural things that seemed free to all of us, started becoming less and less available.”

Finding safe spaces in disinvested neighborhoods like Treme is difficult, underscores how deficiencies in one area can trigger cascading effects. Fragmentation and loss of culture are deeply tied to historical lending practices that have fueled a lack of affordable housing and disinvestment in neighborhood assets.

“Typically, people of color don’t have the credit or the money to buy a house. Normally, we have to rent. I think people are being pushed out because the rents are unavailable; they’re inaccessible. It’s almost impossible to live in that area.”

In New Orleans, short-term rentals add economic pressure. They comprise approximately 3.5% of all occupied housing units in the city, one of the highest rates for similarly sized cities. The shift away from long-term residents has disrupted Treme’s identity, further compounding existing challenges.

“Like so many other areas of this city, it’s forgotten. I would love to see green space there. Just an open space where people can be. Where you can kick around a ball, and it doesn’t roll in the street, and you get hit by a car trying to get it.”

Recognizing firsthand the livability impact of gentrification and racially driven property ownership challenges, Alison is dedicated to preserving Treme’s affordability through her properties to share its history.

“I’ve always made my rental properties affordable because I want people to experience that area. Treme has almost the entire history of New Orleans packed into it.”

These challenges highlight systemic discriminatory practices that have persisted for decades. These practices hinder Black homeowners from improving their homes and increasing their value, especially those with limited reserves. Yet property owners hold power in passing on property responsibly, contributing to equity. Knowing this, Alison remains committed to renewing Treme’s rich history for future generations.

PRIVATE PUBLIC SPACES

Public spaces have always been the heartbeat of cities, adding character and fostering community connections. Traditionally managed by local governments, spaces like parks and plazas are now joined by Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS).

Professor Jerold S. Kayden coined the term POPS, which refers to public areas that, although privately owned, are legally required to be open to the public under city zoning ordinances and land-use laws or to receive specific incentives. These spaces aim to enrich urban life, enhance street-level connections, and serve as valuable assets for property owners.

POPS can provide urban oases, fostering social interaction and community ties. Activities like music performances and recreational sports can thrive in these underutilized areas, turning them into dynamic hubs. Integrating POPS with commercial spaces also makes adjacent areas attractive to high-end tenants.

However, POPS face challenges due to their private ownership. Security measures can restrict access and deter visitors. Balancing security and openness is crucial. Innovative design and unobtrusive surveillance can help maintain accessibility, ensuring these spaces remain vibrant and inclusive.

Beyond formalized Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS), ample opportunities exist to create public spaces without relying on incentives. Opening entire city blocks for public circulation or stepping back from the property line to establish shared spaces can significantly enhance urban vibrancy. Understanding the boundaries between public and private spaces and where the official lines end can unlock creative possibilities.

For example, courtyards or circulation areas designed without explicit barriers between private and public realms foster organic interaction. These informal spaces, free from restrictions, create a more inclusive atmosphere that bridges the needs of both the public and private sectors.

This interplay between public and private spaces extends beyond parks to schools, hospitals, and shopping

centers, often straddling the line between privately owned and publicly accessible spaces. Public spaces for artistic expression further illustrate this dynamic, connecting with diverse audiences while simultaneously encouraging meaningful dialogue.

However, balancing accessibility and security is crucial to the success of POPS and informal public spaces. Prioritizing openness while rethinking traditional security measures ensures these areas foster community engagement and serve as catalysts for vibrant city life.

By integrating elements like accessible seating, well-lit paths, and clear sightlines, these spaces become welcoming for all. Achieving this equilibrium is vital for sustainable urban development, creating equitable communities that meet diverse needs and promote social interaction.

UNMET

SPATIAL MAPPING

This map shows that spatially unmet needs may appear met.

Percentiles show how a census tract compares nationally in housing burden, defined by households earning less than 80% of HUD’s Area Median Family Income (AMFI) and spending over 30% of their income on housing costs.

UNMET COMMUNITY NEEDS UNMET COMMUNITY NEEDS

Site: Treme Neighborhood, New Orleans Location of a proposed bus shelter based on the Living Canopies case study.

Improving area livability involves assessing interconnected services. In areas lacking essential services, interventions aiming to enhance wellbeing require careful consideration to inform future outcomes. Urban renewal projects in Treme have introduced park spaces, but not all meet community needs or are accessible.