Jewish Cemetery Surveys in Slovakia

CONDUCTED BY ESJF (2019-2025)

ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative

CONDUCTED BY ESJF (2019-2025)

ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative

FIRST PRINT PRESENTED TO THE SLOVAKIAN GOVERNMENT

C EMETERIES INITIATIVE

JULY 2025

This report was compiled by Kateryna Malakhova PhD, ESJF Director of Historical Research, from survey material on Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia performed by ESJF surveyors between 2019 and 2025.

The publication of this report and the completion of the national survey of Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia was made possible through the generous contribution of of the Schapira family.

First published 2025

© European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative, 2025

Some rights reserved. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/ 4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA.

Research and Authorship: Kateryna Malakhova

Survey Coordination: Kateryna Klutchnik

Chief Surveyor: Ian Galevskyi

Editing: Philip Carmel

Layout and Graphics: Taras Mosienko

The history of Jewish communities across Central and Eastern Europe is rich and varied, stretching back millennia. In a few short years, the Holocaust brought the long history of thousands of these communities to a cruel and abrupt end. Without their owners to safeguard and preserve them, many of these Jewish cemeteries have fallen into disrepair, and after 80 years of vandalism and neglect, many are at risk of disappearing entirely, bringing the last physical testament to these ancient communities with them.

The ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative is a German-based non-profit established in 2015 by Rabbi Isaac Schapira with the core objective of protecting and preserving Jewish cemeteries across Europe through the accurate delineation of cemetery boundaries and the construction of walls and gates.

Thanks to consecutive annual grants from the Federal Republic of Germany since 2015 as well as private donations, the ESJF has succeeded in fencing over 300 Jewish cemeteries across Europe. The ESJF has also received funding from the European Union (EU) since 2018, which has been used to conduct mass surveys using cutting edge drone technology and conducting educational outreach.

In order to fulfill our mission, the initiative has developed a strong and sustainable administrative and research structure and created standardised models for engineering, halachic methodology and cost effectiveness, contributing to the success of our work across Europe.

ESJF works to protect Jewish cemeteries in Central and Eastern Europe in what we term “designated areas for priority work”, which can be understood as all the former Soviet bloc, as well as South-Eastern Europe. The ESJF’s mission is therefore not only urgent, but vast. Between 2019-2022, with funding from the European Union, the ESJF surveyed and mapped 4,097 Jewish cemeteries across nine European countries, including Poland, Ukraine, Slovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Croatia, Georgia, Moldova and Greece, using cutting edge drone technology. With the data gathered, we created a comprehensive, open-access database of European Jewish cemeteries with maps and descriptions of each cemetery visited. Around another 500 cemeteries were surveyed in Poland in 2023-24, completing a national survey of the country.

Slovakia, a country with the largest density of Jewish cemeteries on its territory, had some 350 of its cemeteries surveyed by the ESJF during the course of the EU project. We are delighted therefore that thanks to funding from the Schapira family, we have been able to complete the national survey of Slovakia adding on around another 400 cemeteries surveyed during 2024 and 2025. This report therefore details the current situation of Slovakian cemeteries and the critical need to protect them while we still can.

We wish to thank the government of the Federal Republic of Germany for its continued support of the work of the ESJF and the Federation of Jewish Communities of Slovakia (UZZNO) for its strong cooperation and assistance in the completion of this national survey.

Philip Carmel Chief Executive Officer ESJF

European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative

The strong partnership between the Federation of Jewish Communities of Slovakia and the ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative began in 2018, when a new fence around the Jewish cemetery in Senec was built after the old fence had been destroyed during a windstorm of 2017.

Since that date, with the generous support of ESJF President Rabbi Isaac Schapira, who has personally been involved for many years in the protection of Jewish heritage in our country based on his own close family connections to the history of our community, the project has developed into the physical protection of many cemeteries in Slovakia, attesting to the vast spread of Jewish communal life here over many centuries.

The project has developed in the form of the searching for and mapping of Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia, their research and air-photographing with drones. This too contributes to the protection of these sacred sites and ultimately, we hope that it will lead to many more fencing projects.

These surveys have led to the publication of this groundbreaking report, which has built upon many years of research undertaken by Slovakian experts and researchers. It accurately presents the state of Slovakian cemeteries today and is a major contribution to our collective heritage.

A great proportion of this work has been enabled through the funding of the ESJF by the Federal Republic of Germany and I wish also to take this opportunity to thank them for all their support for this project.

The ESJF expanded its involvement in Slovakia in 2022, fencing another eight in that year Podolínec, Chmeľov, Veľký Šariš, Selice, Palárikovo, Hurbanovo — Bohatá, Pribeta and Sikenička. This cooperation with ESJF continued also in 2023, with two parallel activities taking place in that year – the mapping of Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia and the work on specific projects involving the construction of fencing around concrete Jewish cemeteries.

A total of 10 cemeteries were fenced in 2023: Pavlovce nad Uhom, Malacky, Dežerice, Ivánka pri Nitre, Leles, Ľubotice, Kuchyňa, Domadice, Slovenská Kajňa and Gajary.

In 2024, we fenced with the ESJF a total of 15 cemeteries, seven of which were made in a more ornamental style. Cemeteries with more decorative fencing: Krupina, Široké, Hronský Beňadik, Perín Chym, Cerová, Betlanovce, Nové Sady; other cemeteries, at Jacovce, Senica (large cemetery), Bošáca, Klátova Nová Ves, Boľ, Kolíňany, Vrútky, Kolbasov, were also protected by the ESJF. And already this year, work is underway at projects in Hlinik nad Váhom and Krompachy, as we look forward to many more fencing and protection activities later in 2025 and into the future.

Slovak Jews and the ESJF: Preserving our Collective Heritage

Moreover, ESJF’s work with the Federation does not end with the fencing itself but works on sustainable models involving local communities in the preservation of this Jewish heritage.

It is in this spirit that I wish also to mention the important cooperation we receive from local authorities in Slovakia who recognize that the preservation of Jewish heritage in Slovakia is a key part of the preservation of local and national Slovakian heritage.

Since 2022 lectures on the history of Judaism are also organized in towns and villages where the fencing projects have been carried out as part of the ESJF project. Lectures for high primary and secondary school students are carried out in cooperation with the Holocaust Documentation Centre (DSH), a non-governmental organization affiliated with the Federation of Jewish Communities of Slovakia. The DSH Centre was established in 2005 and its main focus is Holocaust research, education about the Holocaust and related topics, and the commemoration of Holocaust victims.

In many places of today’s Slovakia, Jewish cemeteries are the only tangible cultural heritage element reminiscent of the Jewish communities that have disappeared as a result of the crime that was the Holocaust.

Working with the ESJF, the Centre has created educational event formats consisting of lectures and field trips for each site protected. Following a prior communication with local schools in the communities, a DSH staff member visited each venue and delivered an approximately 60-minute lecture on the history of Jews in present-day Slovakia and on their history in the given place, the distinctive elements of Jewish culture and monuments, with an emphasis on Jewish cemeteries (and their specific features). Afterwards, they visited the local Jewish cemetery with the students. During this visit to the local Jewish cemetery, typical elements on the tombstones were identified (with

Jewish Cemetery

in Slovakia

the active involvement of the students) and this was followed by a discussion about the questions and topics suggested by the students.

This key educational work was added to last year when the HDC organized also a lecture by ESJF expert Aleksandra Fishel during the Learning from the Past — Acting for the Future seminar, an event organized in Bratislava for 21 teachers from all over Slovakia.

On behalf of the Federation, I again express my deep thanks to the ESJF and look forward to expanding and developing our fruitful contribution. Bratislava, June 2025

Martin Kornfeld Executive Director Federation of Jewish Communities of the Slovak Republic

Although artefacts exist indicating the presence of Jews in the territory of today’s Slovakia from as early as the period when Roman legions were active here, a continuous Jewish settlement is documented only from the early Middle Ages, when today’s Slovakia was already part of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Written sources show that Jews lived in today’s Bratislava already before 1092, during the period when the First Crusade (1096 — 1099) passed through Hungary and local Jews were murdered and their property plundered. Jewish communities are documented in written sources in Trnava in the 12th century, in Trenčín around 1300, in Stupava in 1368, in Holíč around 1400, in Hlohovec, Nitra and Pezinok in 1529.

The life of Jews in the territory of today’s Slovakia in the Middle Ages was influenced by the Hungarian kings and nobles, as well as by the Church and the majority population. In principle, it can be said that in the Middle Ages, the life of Jews was regulated by various laws, prohibitions and restrictions similar to those adopted in other parts of medieval Europe. Restrictions included, for example, those regarding contact with the Christian population, prohibitions on owning land, and the compulsory payment of various taxes. Under this influence, Jews were mainly engaged in trade and financial

services. The periods relatively peaceful life, during which they built their communities, were interrupted by various pogroms and sometimes executions, often incited through superstition and accusation. a typical blood libel accusation of ritual murder of Christian children in medieval Europe occurred, for example, in August 1494 in Trnava, as a result of which ten Jewish men and two women were burned at the stake, accused of murdering two Christian children whose blood was said to be used in the production of matzah. When in August 1526 King Louis II Jagellon of Hungary fell in battle with the Ottomans at Mohács, the country fell into a deep crisis for a long period. Slovakia, in particular, became the scene of power struggles and great unrest for a long time.

In the 17th century, the Jewish population in the territory of today’s Slovakia (Upper Hungary) grew. Jews came mainly from two directions: from the north fleeing unrest and violence (for example during the Khmelnitsky uprising), and from the west — from the territory of present-day Czechia and northern Austria, where local Jews came to seek both refuge, for example after the expulsion of Jews from Vienna in 1670, or from Moravia during the Thökoly uprising in 1683.Settling in royal and mining towns had been problematic for Jews for centuries. The areas of central Slovakia with mining towns dominated by the original German population (descendants of German colonisers from the Middle Ages) or in the region of Spiš, were inaccessible to Jews. The situation was similar in the towns of Košice, Prešov and Bardejov, where Jews had been forbidden to settle since the Middle Ages. They therefore chose to settl in nearby and less important localities such as Rozhanovce (near Košice), Šarišské Lúky (near Prešov) and other villages. In Spiš, Jews were able to settle in the village of Huncovce and elsewhere.

After the annexation of Galicia to the Habsburg monarchy in 1772, Jews from this region naturally began to move to Upper Hungary. There were already widescale trade relations between the two areas, and it is here that the roots of the great wave of immigration to the territory of eastern Slovakia can be found.

In 1783, Emperor Joseph II exempted Jews in Hungary from certain restrictions, allowing them access to education, land leases and free professions and trades. In 1840, the Hungarian government introduced further relaxations of economic restrictions, and in 1867, Jews living throughout Hungary were granted civil equality and rights. Finally, in 1895, the Jewish religion was placed on an equal footing with other religions.

After the First World War (1914-1918), which had major repercussions for all inhabitants of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including those who lived in the territory of today’s Slovakia (its northeastern parts were also affected by the fighting), great changes took place. The dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the establishment of Czechoslovakia were turning points in the history of the Jews in Slovakia.

Approximately 35,000 Jews were deported in 1944 from the territory of present-day Slovakia, which was part of Hungary between 1938 and 1945. The vast majority of them were murdered. The number of Holocaust victims from the territory of present-day Slovakia is estimated at 105,000.

The period of the Czechoslovak Republic (1918-1938) is generally regarded as a time of complete religious and civil freedom, which led to the flourishing of Jewish communities in Slovakia. From the 19th century onwards, Jews held an important position in the Slovak economy, particularly in commerce, industry and the liberal professions. The democratic regime of the republic, the connection with industrially advanced Bohemia and at the same time with rural Subcarpathian Rus, brought various advantages.

However, the aggressive policies of Nazi Germany in the 1930s eventually led to the weakening of Czechoslovakia and ultimately to its disintegration. After the Munich Agreement, representatives of the Hlinka Slovak People’s Party (HSPP) took power in Slovakia in October 1938 and immediately began to implement antisemitic policies and

Slovakia

persecute Jews. In November 1938, a large part of southern Slovakia was annexed by Hungary. When the Slovak state was proclaimed in March 1939, antisemitism became state policy. During 1939-1942, Jews living on Slovak territory were the target of a harsh and systematic antisemitic policy, which included the so-called aryanization of all forms of their property. More than 57,600 Jews out of a total of about 89,000 were subsequently deported by the regime of the Hlinka Slovak People’s Party, led by Jozef Tiso, to Nazi concentration and extermination camps in the territory of occupied Poland. Another 13,500 Jews were deported to Auschwitz and concentration camps in Germany, or to Terezín in 1944-1945. Around 1,000 Jews were murdered on the territory of Slovakia.

After the end of World War II, Holocaust survivors tried to rebuild Jewish communities, but the crimes committed by the Nazis and their Nazi collaborators were so great that many communities could not be rebuilt. The restitution of Jewish property and also the punishment of war criminals and collaborators were very complicated and lengthy. The advent of communist totalitarianism in February 1948 further complicated the situation of the Jews in Slovakia. Thousands of survivors emigrated to the emerging state of Israel, as well as to the USA, Canada, Australia, Belgium and other countries in Western Europe. The communist regime plunged the country into autocracy until 1989.

Following the so-called Velvet Revolution in 1989, the situation changed, and activities aimed at the restitution of property and the documentation and restoration of Jewish cultural heritage were renewed. They continued even after the division (Velvet Divorce) of Czechoslovakia in 1993. The Federation of Jewish Communities of Slovakia played a major role in this. The restoration of synagogues and the documentation and restoration of Jewish cemeteries began. The Federation of Jewish Communities of Slovakia, as well as some regional and local governments and local activists, performed important roles. . Today, many Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia are still in poor condition and unfenced. They remain as witnesses to the rich and turbulent history of the Jewish people in Slovakia.

Ján Hlavinka, PhD Slovak Academy of Sciences, Institute of History, Senior Researcher

Between 2019 and 2025, comprehensive surveys of Jewish cemeteries were conducted throughout the territory of the Slovak Republic. During the period from 2019 to 2022, fieldwork was carried out in the Košice, Prešov, and Banská Bystrica regions. From 2023 to 2025, survey activities expanded to include the Trenčín, Nitra, Trnava, and Bratislava regions.

The primary objective of this research is to obtain accurate and updated information regarding the location of all Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia, as well as to assess their current state of preservation and protection. This encompasses both extant and destroyed cemetery sites.

These surveys in Slovakia are part of an ongoing ESJF project to localize and delineate, photograph and drone film, which describe the condition and threat level of Jewish cemeteries in Eastern and Central Europe. As of June 2025, the ESJF has surveyed and mapped a total of 4022 cemeteries in the following countries: Ukraine, Georgia, Hungary, Lithuania, Croatia, Slovakia, Poland, Moldova and Greece. This represents about 50% percent of the estimated number of Jewish cemeteries in central and eastern Europe.

The goal of the project is to ensure the physical protection of endangered Jewish cemeteries and to draw the attention of local activists and stakeholders at all levels to the need to preserve them.

ESJF gratefully acknowledges and builds upon existing research and databases. The study of Jewish heritage in Slovakia has a long-established history, and without these foundational studies, the present work would not have been feasible. The fundamental research by E. Barkany, P. Werner, and others formed the foundation of existing lists and databases.

UZZNO. Ústredný zväz židovských náboženských obcí v Slovenskej republike (UZZNO)

– the Federation of Jewish Communities of Slovakia. At the beginning of this project, UZZNO kindly provided the ESJF with a list of cemetery plots returned to the Jewish community of Slovakia through the restitution process. The list included 496 cadastral plots. Since the territories of some cemeteries consist of several cadastral plots, the number of cemeteries that these plots cover is smaller than this figure — 389, according to ESJF calculations.

In addition to this list, UZZNO created an online database https://zidianaslovensku.sk/ cintoriny/. The preface to the list states the approximate number of Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia as “about 800”. However, this database contains only 213 cemeteries.

IAJGS The International Jewish Cemetery Project by the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies contains an extensive database of Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia, available online. This database contains information about the presence of a cemetery in a settlement, some details of its history, the number of tombstones and their condition. Some of this data is inaccurate or outdated. In most cases, there is no geographical location. The IAJGS database contains information about approximately 425 Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia.

JOWBR JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry is the largest database of Jewish burials, which contains names, epitaph texts and sometimes photographs, as well as name and geographical search. This database contains information about 222 Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia: the number of tombstones and partially their photographs. The locations of these cemeteries are not in the database. a feature of this database is that individual Jewish burials in municipal cemeteries (formally neither Jewish cemeteries nor Jewish sections) are included in the registry.

Private and regional databases Regional and private databases of Jewish cemeteries are a very important source of information. The project «Pamiatky na Slovensku» («Heritage Sites in Slovakia») (https://www.pamiatkynaslovensku.sk/cintoriny-zidovske) by historian Viliam Mazanec contains quite complete information about 334 Jewish cemeteries — including location and photographs. The «Zilina Gallery» project https:// zilina-gallery.sk/index.php?/category/1701 provides detailed information about 62 cemeteries in the vicinity of Žilina. These and other regional and private databases of Jewish cemeteries are a very important source of information.

Comparison of data from these lists is complicated by the fact that different projects have different criteria for selecting objects: whether or not they include destroyed cemeteries, Jewish burials in municipal cemeteries, etc. In addition, cemeteries are often registered in lists under different names (in cases where they were used by several communities).

The collation and compilation of these databases, which required preliminary identification and localization of the cemeteries mentioned in them, produced a list that became the basis of our research.

Search for cemeteries not included in databases: archival and other additional sources. In the early stages, the research showed that in rural Slovakia, Jewish

cemeteries arose including in very small communities — where the peak Jewish population was several dozen people. At the same time, according to population censuses, such communities of several families existed in very many settlements. Many of them could have been completely forgotten.

Therefore, it was decided to turn to archival sources — historical cadastral maps of the mid and late 19th century, which in most cases mark Jewish cemeteries with a special sign.

Based on census data from 1840 to 1941, a list of settlements with a peak Jewish population of more than 20 people was compiled. Within the framework of a small archival study in autumn 2024, about 400 cadastral maps of Slovak settlements contained in the UGK archive (Bratislava) and in the National Archive in Budapest (digitized by the archive) were checked. Unfortunately, not all available maps belonged to the required period or contained the necessary marking. Nevertheless, it was thus possible to identify about 30 previously unknown cemeteries.

An additional important tool was the open modern cadastral registry of Slovakia — Portal ESKN («Portal of Electronic Services of Real Estate Cadastre») belonging to the Office of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre of the Slovak Republic (Úrad geodézie, kartografie a katastra Slovenskej republiky, hereinafter «ÚGKK»). In most cases, the cemetery territory belongs to UZZNO or is registered to another Jewish organization. The cadastral plot plan serves as a precise indication of the location and boundaries of the cemetery, and its ownership can help identify the place as a Jewish cemetery.

Initial field surveys, undertaken by the ESJF as part of a European Union grant, began in August 2019 and continued until 2022. Remaining surveys were completed between 2023 and May 2025.

The tasks of the field teams include searching for the cemetery on the ground and determining its boundaries, photo documentation and drone filming, as well as filling out questionnaires to provide basic information about the condition of the cemetery and the degree of its protection: size, number of preserved tombstones, presence of fencing, condition of the territory and existing threats.

A separate task of the field team is to establish contact with the local administration, which helps find the cemetery and gain access to it, and can also provide additional information about the history and condition of the cemetery, current threats and measures for its preservation and protection.

Given that many cemeteries have left no visible traces, a fundamental question emerges: how does this research determine whether a particular site constitutes a Jewish cemetery?

In identifying sites, we employed two primary criteria:

1. The presence of tombstones in situ bearing Hebrew epitaphs.

2. Designation of the area as a Jewish cemetery on at least one historical map.

Each of these criteria was considered sufficient grounds for inclusion of a cemetery in the database.

Additionally, several indirect indicators were taken into consideration. While none of these alone provides sufficient evidence, collectively they may prove decisive in complex cases:

Current ownership of the site by UZZNO or another Jewish community organization

Mention of the site as a Jewish cemetery in research, memoir, or other literature

Testimonies from local residents who remember the location as a Jewish cemetery

Decisions were not made automatically; in disputed cases, micro-investigations were conducted, weighing various arguments both for and against identifying the site as a Jewish cemetery.

Sites lacking sufficient evidence of having served as Jewish cemeteries were not included in the database. This does not preclude the possibility that such evidence may be discovered in the future.

The main objective of the project is to identify the degree of preservation and protection of recorded cemeteries. Accordingly, cemeteries were divided into

Preserved, that is, those where at least one tombstone in situ has been preserved,

Demolished, on which the tombstones were not preserved.

The preserved cemeteries are divided into 1) protected and fenced, 2) unfenced, therefore, endangered.

The demolished cemeteries were divided into:

1) demolished and overbuilt. In these cases, not only tombstones, but also burials were lost,

2) demolished which has not been built over. These are the cemeteries where the tombstones were used for various needs by the authorities or the local population, however, the burials were most likely preserved.

Jewish sections in municipal cemeteries were allocated into a separate category. As Jewish sections are part of the municipal cemeteries, they do not require separate protection and are protected by the state as a municipal cemetery.

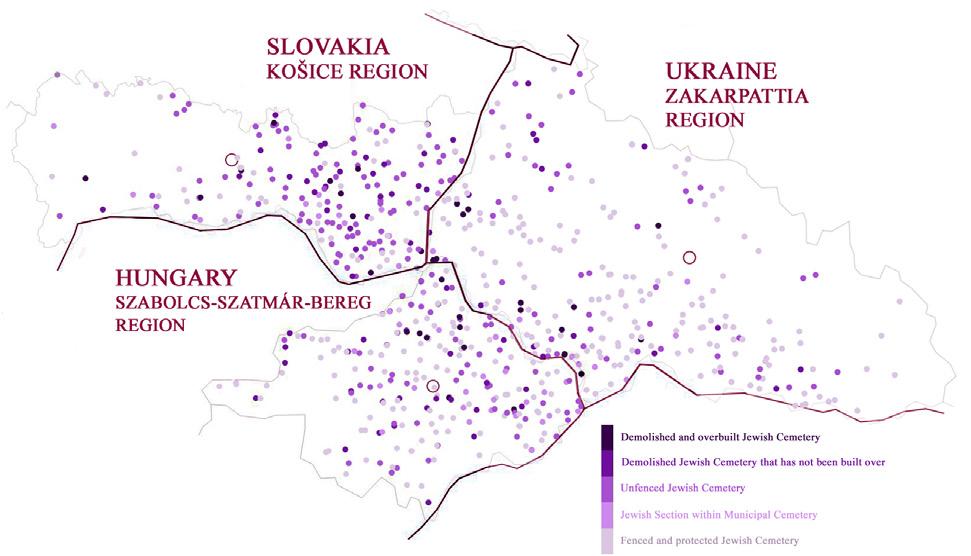

Thus, cemeteries were divided into five categories, reflecting the preservation and protection state of the object:

Fenced and protected Jewish cemeteries

Unfenced Jewish cemeteries

Jewish sections within municipal cemeteries

Demolished Jewish cemeteries that have not been built over

Demolished and overbuilt Jewish cemeteries

In total, from 2019-2025, ESJF described and entered into the database 745 Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia.

Bratislava 30

Trenčín 65

Trnava 114

It should be emphasized that the list we present is not an exhaustive list of all cemeteries that have ever existed in Slovakia. The search and identification of some cemeteries, especially destroyed ones, requires prolonged and labor-intensive research. This work is being continually conducted by both Slovak scholars and ESJF. At present, we know of the existence of at least 30 more cemeteries that have not yet been located. As information becomes available, the cemeteries will be surveyed and added to the ESJF database.

Nevertheless, this number significantly exceeds the number of necropolises presented in other open databases:

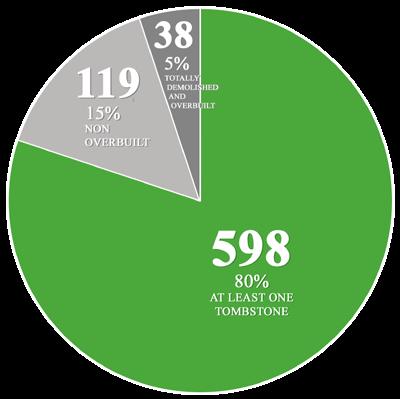

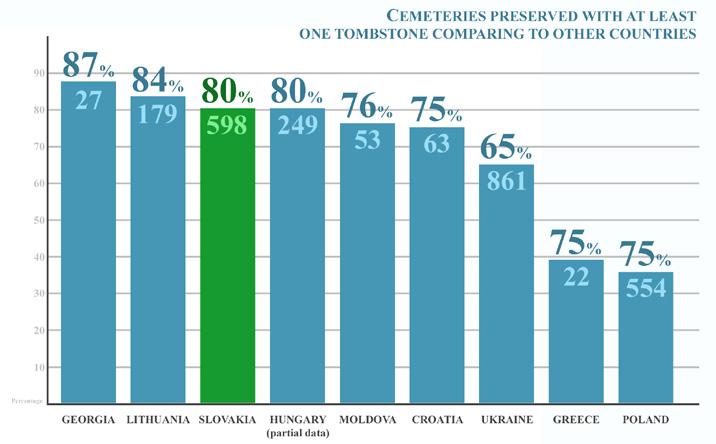

Of the 745 surveyed Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia, 598 (80.2%) have at least one preserved tombstone. 38 cemeteries (5%) are demolished and their territory has been built over. At 109 (14.7%) no tombstones have been preserved, but burials may have been preserved.

Compared to other countries, this indicates a fairly high level of cemetery preservation, similar to Hungary (80%), however falling short of Lithuania (84%) and significantly exceeding Ukraine (65%) and Poland (46%).

Protection:

The obtained data shows that exactly half of the surveyed Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia need physical protection. 373 cemeteries (50%) require fencing. Of these, 264 (slightly more than two-thirds) are cemeteries with at least partially preserved tombstones, and the threat affects not only burials but also historical monuments. 109 (approximately onethird) are cemeteries where only burials have been preserved. They are mostly unmarked in any way, and physical fencing is necessary to protect the territory from construction and use for other purposes.

45% (334) of the surveyed cemeteries have physical protection. Of these, 270 are separate Jewish cemeteries, 64 are Jewish sections in municipal cemeteries.

Compared to other countries surveyed by ESJF, Slovakia has a high percentage of cemeteries requiring protection. This is partly explained by the high preservation rate of cemeteries — the necropolises of communities that perished in the Holocaust, left without care, were not destroyed and built over, but have survived to the present day.

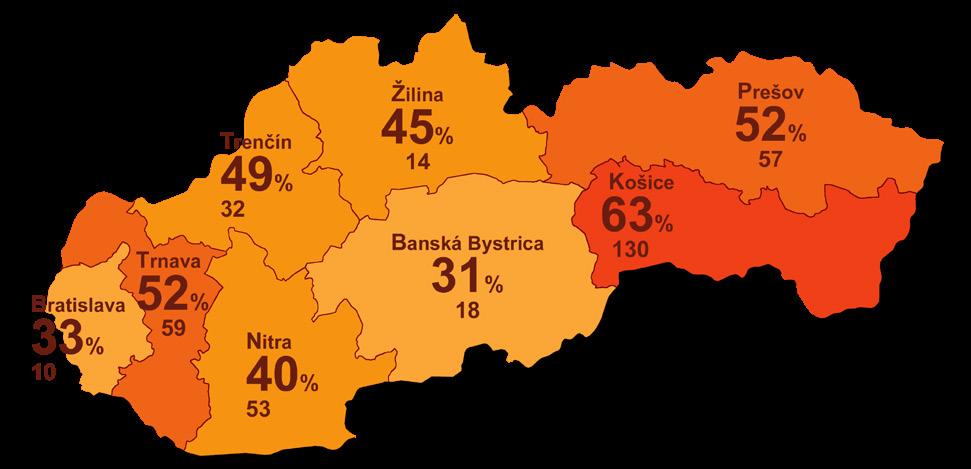

Despite the country’s small size, data by regions of Slovakia shows some difference in indicators.

Percentage of the cemeteries preserved with at least one tombstone by kraj:

The highest cemetery preservation is in the Banská Bystrica and Trenčín regions. This may be related to the mountainous terrain, which makes access to cemeteries difficult and even more so, subsequent development of the cemetery territory. The lowest preservation rate is in the Bratislava region, which is characterized by active development due to flat terrain and proximity to the capital.

Percentage of cemeteries requiring physical protection by kraj:

The number of cemeteries requiring physical protection is highest in the Košice region — 130 cemeteries, comprising 63% of the total. This is facilitated by the remoteness from the center of the country and the large number of small cemeteries, many of which are abandoned, do not appear in any registries and receive no support from the community.

The best situation is in Bratislava — where the preserved cemeteries are actively cared for by the Jewish community of Bratislava — and in Banská Bystrica, where not only the cemeteries but also their fencing have been largely preserved.

Adistinctive feature of Jewish necropolises in Slovakia is their enormous number for a relatively small country and the small size of the cemeteries themselves.

The reason for this is a special type of Jewish settlement in the 19th century, characteristic of Austria-Hungary (especially its Hungarian part): free settlement in villages, formation of numerous Jewish rural micro-communities consisting of several families.

This feature can be expressed numerically through the density of cemetery placement in — the number of cemeteries per unit of territory. Obtaining this data became possible thanks to the relatively complete unified database of Jewish cemeteries with precise geolocation for these countries, compiled by ESJF.

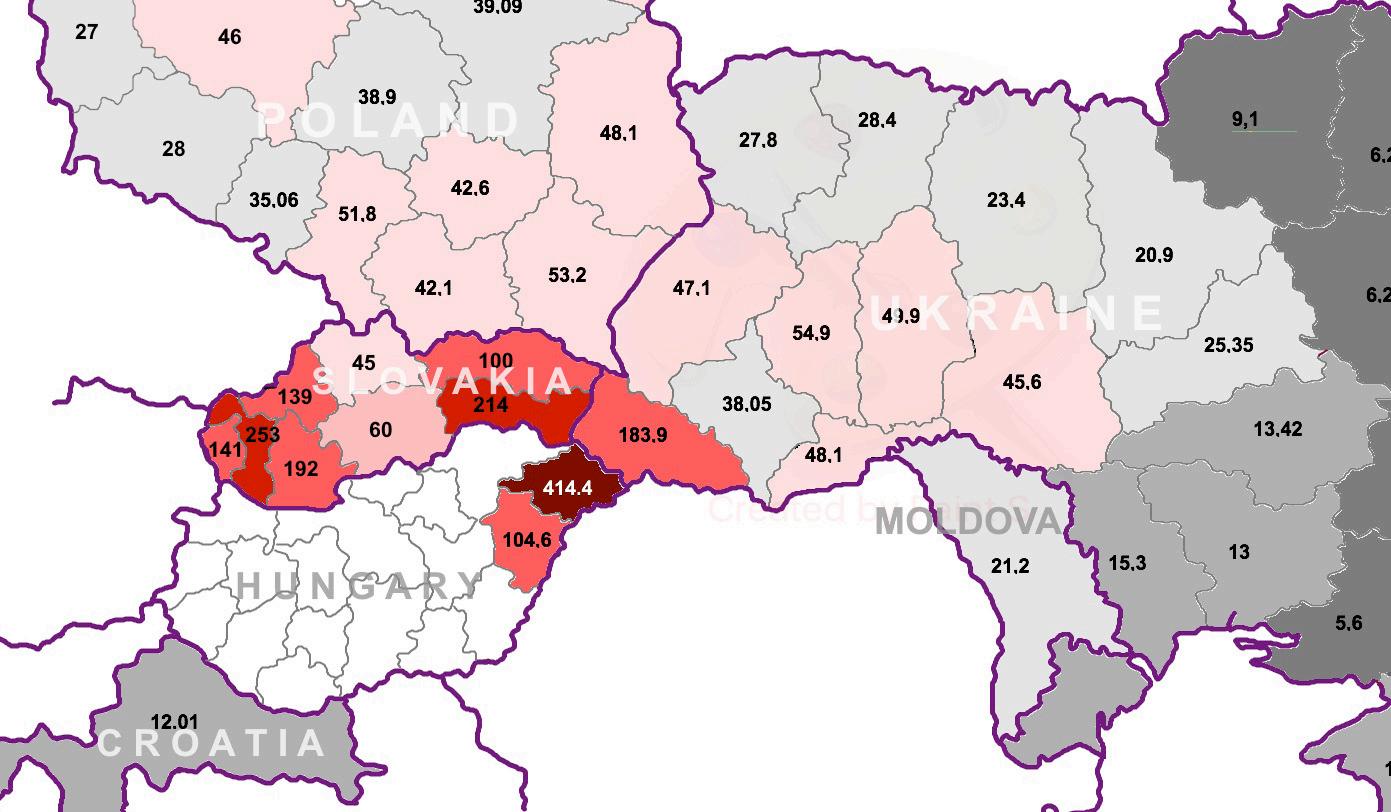

The map below shows the number of Jewish cemeteries recorded by ESJF per 10,000 sq. km in Slovakia and neighboring countries.

While the average density of cemeteries in the territories of Ukraine and Poland is 3540 cemeteries per 10,000 sq. km, in Slovakia, as well as the northeastern regions of Hungary and Ukrainian Transcarpathia, it reaches 200 and higher.

Analysis: Key Points

At the same time, the region at the junction of Slovakia, Hungary and Ukraine is distinguished by a special, unique density of cemeteries: the Košice region of Slovakia (more than 288), the Hungarian region of Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg (414) and Ukrainian Transcarpathia (183):

In reality, this means that on flat terrain, especially along roads and rivers, in places of active population movement, a Jewish cemetery existed in almost every large village — everywhere where at least a small Jewish population appeared.

These cemeteries are unique testimonies to the lives of small rural Jewish microcommunities, about many of which no other memory has been preserved. a community might not have had a prayer house, much less its own rabbi — however, the cemetery as a basic communal institution already existed.

To find and document such sites provides unique history on the presence and history of Jews in the settlement.

Census data provides an opportunity to examine how the presence of a cemetery relates to the size of the community (peak Jewish population) using the example of the Košice region.

In total, the study described 192 settlements (communities) with Jewish cemeteries in Košice, some of which have two (or even three) cemeteries.

Among these, 140 communities had a peak Jewish population of less than 100. Of these 140, 67 communities had less than 50. Finally, of these 67, in 16 communities no more than 20 Jews ever lived.

Of course, it should be taken into account that Jewish families from neighboring villages also used the cemeteries, so the total Jewish population of such a «cluster» could have been larger. Nevertheless, the figures demonstrate a unique situation — separate Jewish cemeteries for several families.

Amazing examples of such cemeteries are Rakovnica and Koceľovce. In both settlements, the peak Jewish population was 5 people.

In Koceľovce (Geczelfalva), two Jews were registered in 1880, and five in 1910.

Analysis: Key Points

The cemetery is located in a wooded area, 500 meters north of the village outskirts. It represents a rectangular structure of old stone masonry one meter high, room-sized, about 8 meters long and 4 meters wide. Inside there is a row of three women’s graves from 1890, 1893 and 1894, which occupy almost all the cemetery space. From the names it is difficult to understand whether this is one family or not. At different times several Jewish families lived in Koceľovce (the family of innkeeper Samuel Breitbart,

and also, apparently, Frankfurter, Liebermann, Liplich), however the total number of Jews at any given time was extremely small. And nevertheless, this proved sufficient for the emergence of a cemetery with a massive stone wall, designed for a maximum of about ten burials, judging by its size.

Rakovnica (Rekenyeujfalu) had in 1910 5 Jews, and in 1941 — 3.

The Jewish cemetery of Rakovnica is located in the village and adjoins the Christian one, has no fencing, consists of a row of six tombstones. Three of them, preserving readable inscriptions, belong to members of one family — Lissauer.

Judging by birth, marriage and death records, only one Jewish family, Lissauer, actually lived in Rakovnica.

This means that even one Jewish family is sufficient for the emergence of a cemetery.

Such cemeteries for one or two families are also characteristic of other regions of Slovakia.

This fact significantly affects the current state of these small cemeteries. The probability that all descendants of those buried in such a cemetery perished in the Holocaust is much higher than when dealing with large necropolises of ordinary communities. Hundreds of such cemeteries for one or two families are unknown to anyone except local residents and local historians, and some are completely forgotten. Their protection falls to Jewish organizations, including ESJF.

Analysis: Key Points

Nitra region, Slovakia

cemetery on cadastral plan 1910

A widely distributed type of Jewish cemetery arrangement in Slovakia is a section in a general municipal cemetery. The ESJF study recorded 64 of them (8.5%). In individual regions their share increases to 14% (Nitra) and even to 32% (Banská Bystrica). This is significantly higher than in other studied countries that were formerly under the rule of the Russian Empire (Poland — less than one percent, Ukraine — four), but comparable to Austro-Hungarian territories — Hungary (10%) and Croatia (36%). In other words, this is characteristic of a region with the above-described type of Jewish settlement — many small rural communities, large numbers and high density of cemeteries.

Obviously, this is connected with the practice of allocating burial places for small communities near other cemeteries — Catholic, Evangelical and others. Judging by

historical cadastral maps, these were indeed separate small Jewish cemeteries — inside or adjacent to the perimeter of Christian ones. Over time, Christian cemeteries grew while Jewish ones fell into decline, and the boundary between them was erased.

Today such cemeteries represent several Jewish graves within the fence of a municipal cemetery. Formally they are protected both physically — by the cemetery fence, if there is one, and legislatively, as part of the municipal cemetery. In reality, many of them, in the absence of boundary markings, face the threat of destruction and encroachment by Christian burials.

Once part of Czechoslovakia, Slovakia has been independent since 1993 and has been a member of the European Union since 2004. The Federation of Jewish Communities of Slovakia (Ústredný zväz židovských náboženských obcí v Slovenskej republike — UZŽNO) is the legal successor to the defunct Jewish Communities and Jewish associations in the Slovak Republic according to decree Ú.v. no. 231/1945. Thus, all Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia are considered property of UZŽNO.

In Slovakia, an open system of national land cadastre – Portal ESKN (“Portal of Electronic Services of Real Estate Cadastre») https://kataster.skgeodesy.sk/esknportal/ — allows for relatively easy identification of the owner of any given land plot by its cadastral number, without requiring additional inquiries. The precise location of cemeteries and determination of their perimeters, conducted by ESJF, combined with this system, makes it possible to obtain accurate data about the owners of all Jewish cemeteries today.

Complete data and statistics on the owners of each land plot documented by ESJF are in preparation and will be presented to UZZNO.

Analysis: Key Points

The data obtained for the Košice Region, nevertheless, shows that the on-the-ground situation is more complex than described above.

Of the 205 Jewish cemeteries in the Košice Region documented by ESJF, according to current data:

The territory of 131 cemeteries (64%, approximately two-thirds) is directly owned by UZZNO. The condition of these cemeteries corresponds to regional averages — 82% have preserved headstones, one-third are fenced, two-thirds need fencing.

24 cemeteries (12%) are owned by municipalities or village councils, and another 9 (slightly more than 4%) are in direct state ownership. This group has the highest preservation rate — 94% of cemeteries have headstones. The level of protection is also typical for the region: 36% are protected, 61% require protection.

24 cemeteries (12%) are in private ownership, and another 4 cemeteries are owned by large companies. Among privately owned cemeteries, none are protected at all. The proportion of demolished cemeteries is high — 37% (regional average is 20%). Additionally, a significant part of the cemeteries is not separate cadastral plots and today form part of larger land holdings. Privately owned cemeteries with headstones (62%) and those necropolises where only burials remain (16%) are of greatest concern.

13 cemeteries (slightly more than 6%) are designated in the Portal ESKN system as belonging to legal entities representing local Jewish communities. Four of them belong to the Jewish community of Košice. In nine cases, these legal entities have names of Jewish communities from specific villages where these cemeteries are located: "Barčianska Židovská náboženská obec" ("Jewish religious community of Barca"), "Židovská cirkev Betlanovce" ("Jewish church of Betlanovce"), "Izraelská náboženská obec Brehov" ("Israeli religious community of Brehov") and others. Jewish communities have not existed in these villages since the Holocaust. It's possible that the ownership of cemetery territories by these no-longer-existing communities is a remnant of the pre-war situation, and for some reason the ownership was never reregistered. It's important to understand that these cemeteries in any case fall under the jurisdiction of UZZNO, which is an umbrella organization uniting Jewish communities in Slovakia today. This group has the highest percentage of demolished cemeteries - 46% (more than twice the regional average). The question of responsibility for preserving these cemeteries becomes particularly relevant.

Analysis: Key Points

The figures presented for the Košice Region show that:

Even after the restitution, about one-third or more of Jewish cemeteries in Slovakia do not belong to UZZNO, Between 12 and 15% of cemeteries are in private ownership and face the greatest threat, About 5% of cemeteries belong to inactive local Jewish communities, raising questions about responsibility for these sites, Some cemeteries are not designated as separate cadastral plots but are part of larger cadastral plots under municipal, state, or private ownership. This significantly complicates the potential return of these lands to UZZNO and their protection in the future.

(Listings and Condition by Region)

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

48

49

50

51

52 52

53 53

54 54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

Kecerovské

Kecerovské Pekľany Newest Unfenced

Kecerovské

68

69 69 Kravany

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

93

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

173

174

175

177

178

179

180

183

184

185

186

198 198 Zemplínska Široká Unfenced Jewish cemetery 107 meters

199 199 Zemplínska Teplica Demolished Jewish cemetery that has not been built over 103 meters

200 200 Zemplínske Jastrabie New Unfenced Jewish cemetery 170 meters

201 201 Zemplínske Jastrabie Old Demolished Jewish cemetery that has not been built over 127 meters

202 202 Zemplínske Kopčany Demolished Jewish cemetery that has not been built over 294 meters

203 203 Zemplínsky Branč Jewish section within municipal cemetery within municipal cemetery 186 meters

204 204 Zemplínsky Klečenov Demolished Jewish cemetery that has not been built over 52 meters

205 205 Zlatá Idka Unfenced Jewish cemetery 37 meters

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

241

242

243

248

250

251

255

256

257

258 53 Nižný Hrušov

259

260

261

262

263

265

275

276

277

278 73 Ruské

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

290

291

292

293

294

300

316 1

317 2

318 3

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

Banská

Banská Bystrica New

Banská Hodruša (Hodruša-Hámre)

332

333

334

335

336

339

340

341

342

343

348

349

357

358

360 45 Seľany Jewish section within municipal cemetery

361 46 Širkovce Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

362 47 Skerešovo Jewish section within municipal cemetery

363 48 Štrkovec

364 49 Tisovec Fenced and

365 50 Tornal’a (former Šafárikovo) Jewish

366 51

367 52 Vinica Fenced and

368 53 Žarnovica New Unfenced Jewish cemetery

369 54 Žarnovica Old Demolished Jewish cemetery that has not been built over

370 55 Zelené Fenced and

371 56 Žiar nad Hronom

372

373

374

375

376

377

394

395

396

397 24 Turčianske Teplice Fenced and

398

399

400

401

402

403 30 Vysoká nad Kysucou Unfenced Jewish

404

463

467

468

469

495

499

500

502

539 70 Nové Zámky Neolog Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

540 71 Nové Zámky Orthodox Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

541 72 Nýrovce Jewish section within municipal cemetery

542 73 Oponice Demolished Jewish cemetery that has not been built over

543 74 Orešany Demolished Jewish cemetery that has not been built over

544 75 Palárikovo 2 (Za Cergatom) Demolished Jewish cemetery

545 76 Palárikovo 1 Fenced by ESJF

546 77 Podhorany (Sokolníky) Unfenced Jewish cemetery

547 78 Pohronský Ruskov Jewish section within municipal cemetery

548 79 Preseľany Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

549 80 Pribeta Fenced by ESJF

550 81 Radošina New Unfenced

551

552 83 Rajčany Unfenced

553 84 Rišňovce Unfenced Jewish cemetery

554 85 Rubáň Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

555 86 Šahy Ortodox Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

556 87 Šahy Status Quo Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

557 88 Šaľa (Veča) New Demolished Jewish cemetery that has not been built over

558 89 Šaľa (Veča) Old Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

559 90 Šalgovce Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

560 91 Selice Fenced by ESJF

564

565

566

583 114 Velké Janíkovce Unfenced Jewish cemetery Requires additional research

584 115 Veľké Lovce Unfenced Jewish cemetery

585 116 Veľké Ludince Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

586 117 Veľké Ripňany Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

587 118 Veľké Zálužie Jewish

588 119 Veľký Cetín Demolished

589 120 Vieska nad Žitavou Jewish section within municipal cemetery

590 121 Vinodol Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

591 122 Vlčany Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

592 123 Vozokany (okres Topoľčany) Demolished Jewish cemetery that

593 124 Vráble Fenced and

594 125 Výčapy-Opatovce

595 126 Zbehy Unfenced Jewish cemetery

596 127 Želiezovce Jewish section within municipal cemetery

597 128 Zemianska Oľča Fenced and protected Jewish cemetery

598 129 Žitavce Unfenced Jewish cemetery

599 130 Zlaté Moravce Orthodox Fenced and

600 131 Zlaté Moravce Neolog Fenced

601 132 Zlatná na Ostrove Fenced

671

672

673 72 Radošovce (okres Trnava)

674

675

676

677

688

689

691

694

738

740

741

742

743

744