Table of Contents

1 Letter from the Editors-in-Chief

Neha Skandan and Wassim Bouhsane

2 Letter from Vice Dean Joshua M. Sharfstein to the Editors and Readers of Epidemic Proportions

Joshua M Sharfstein, M.D.

3 Letter from Dean Christopher S. Celenza, for Epidemic Proportions: Celebrating 50 Years of Public Health Studies

Christopher S. Celenza, Ph.D.

4 A Note on the Cover

Rose Chen

Features

8 Addressing Social Needs in Gynecology Oncology: Insights from a Hopkins Community Connections Advocate

Aminata Sinyan

10 Grace House - My Experience Witnessing Recovery and Resilience Within New Orleans

Isabelle Jouve

11 Community Close to Home: My Summer at Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition (BHRC)

Atri Surapaneni

12 An “Eye” Opening Experience

Tabatha Alegria

14 Hopkins Past the 21218: Baltimore, DC, and Beyond

Habin Hwang, Features Team

15 Why I (and Many Others) Chose to Double Major

Vivan Guo, Features Team

16 Looking Back, Looking Forward - the Past 50 Years of Undergraduate Public Health Education

Habin Hwang, Features Team Editorials

20 The Gun Violence Epidemic: Why This Issue Is More Severe Than We Realize

Samuel Yeboah-Manson

22 Revolutionizing Healthcare: A Proactive and Patient-Centric Approach to Preventable Chronic Conditions

Jayvik Joshi

24 Telemedicine: The Future of Patient Consultation

Hyeongmin Cho

26 The Impacts of Climate Change on the Future of Public Health

Pearl Shah

28 A Case Study on How a Country’s Dependence on Tourism Can Affect Its Healthcare System: Thailand

Sittha Cheerasarn

32 A Gift of Fire: Guiding the AI-driven Healthcare Revolution for a More Equitable Future

Annie Huang

38 Beyond the Statistics: Young Women, Breast Cancer, and Self-Advocacy

Ananya Gulati

42 Breaking Barriers: Unveiling the Structural Risk Fueling the Gender Gap in HIV Vulnerability in Southern Africa

Prisha Batra Policy

48 Evergreening and Patent Warfare Between Pharmaceutical Companies Underlie Deeper Controversy on Intellectual Property Policy Across the World

Pranav Kotamraju and Tanisha Taneja, Policy Team

52 Weight Loss in Public Health: To Drug or Not to Drug?

Pranav Kotamraju and Tanisha Taneja, Policy Team

54 Introducing the Center for Gun Violence Solutions at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Junwoo Park

56 Vaping: New Age Smoking With the Same Old Problems

Alicia Berger

58 Why Are You Studying Public Health?

Wanli Tan and Kevin Mao

59 What Does Public Health Mean to You? Research

62 FDA’s Project Optimus: Dose Optimization During Oncology Drug Development

Chujun Liu

65 Antibiotic Overprescription: Analyzing Possible Causes Within Asian Immigrant Communities

Timothy Huang

68 Navigating Public Health Research as Hopkins Students Research Team

70 Epidemic Proportions Staff 2023-2024

Letter from the Editors-in-Chief

To Our Readers,

It is with great pleasure that we share with you this very special edition of Epidemic Proportions.

Celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this year is the Johns Hopkins Undergraduate Program in Public Health Studies, a program which has inspired multiple generations of public health practitioners since its founding. Epidemic Proportions is in every respect a product of the program’s commitment to improving public health at the local, national, and international levels through curricular and extracurricular education and training. We are therefore proud to concurrently celebrate our journal’s twentieth anniversary this year. Since 2004, Epidemic Proportions has provided a platform for undergraduate students to share their experiences engaging in public health fieldwork and research, as well as to voice their perspectives on public health issues that resonate with them. As we commemorate not one but two anniversaries this year, it is only fitting that we reflect on the tremendous advancements that public health has made over the past twenty and fifty years. During this time, communities across the world have considerably enhanced their ability to respond to the myriad of health crises that have taken the global spotlight. In spite of this monumental progress, however, significant work remains in ensuring how moments from the past can inform the navigation of the future public health scene.

The desire to bridge historical experiences in the field with the modern face of public health has inspired the theme for the twenty-first volume of Epidemic Proportions: “Historical Horizons”.

As you peruse our journal, you will travel from Baltimore, our hometown, to New Orleans, and across the world from Southern Africa to Thailand, visiting a number of places along the way. In doing so, you will encounter a plethora of experiences and opinions on topics ranging from breast cancer and harm reduction to gun violence and telemedicine, all of which will challenge you to critically evaluate the status and direction of public health. The convergence of these two milestone anniversaries calls for the meaningful and thoughtful reflection required in public health, which will shed light on how society can maximize our potential to lead longer, happier, and healthier lives.

Once again, thank you so much for taking the time to read this very special edition of Epidemic Proportions. We hope that you enjoy “Historical Horizons” as much as we enjoyed composing it.

Sincerely,

Neha Skandan Wassim Bouhsane

Neha Skandan Wassim Bouhsane

1

Letter from Vice Dean Joshua M. Sharfstein to the Editors and Readers of Epidemic Proportions

To the Editors and Readers of Epidemic Proportions:

Congratulations on this anniversary issue!

Fifty years of undergraduate public health education at Johns Hopkins represent a tremendous milestone, as does twenty years of this very journal. It is dizzying to think of all of the changes that have occurred both in public health and in public health education during this time. Fifty years ago, smallpox still existed in the wild – though the fight to eradicate it was being waged, and being won. Twenty years ago, the world had just survived an outbreak of a novel coronavirus, ushering in a new era of threats that would come to include the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Public health education has changed over the decades as well. Certainly, core disciplines such as epidemiology and biostatistics have remained pillars of the field. But joining them are now public health ethics, community-based participatory research, and health equity. To succeed, technical proficiency in data analysis is still necessary, but hardly sufficient. Community engagement, policy development, and advocacy are essential skills for understanding key health challenges and opportunities for making tangible progress for health, well-being, and justice.

In 2006, as health commissioner of Baltimore, I reached out to the undergraduate public health program at Johns Hopkins about a new initiative that I was hoping to bring to the city, then called Project Health (and now called Hopkins Community Connection). I was amazed by the students' enthusiasm, commitment, and leadership, which made the program possible. In the years since, hundreds of Hopkins students have helped thousands of Baltimore families obtain essential resources for their health. I am eternally in debt to you for these ongoing efforts, even as I marvel at the inspiring new projects that students create, develop, and implement.

In short: Thank you for the brilliance, light, and hope that you bring to our field and to our world.

And again, Congratulations!

Sincerely,

Joshua M. Sharfstein, M.D.

Joshua M. Sharfstein, M.D.

Vice Dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement

Distinguished Professor of the Practice

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

2

Letter from Dean Christopher S. Celenza, for Epidemic Proportions: Celebrating 50 Years of Public Health Studies

As dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, I am pleased to congratulate our undergraduate program in Public Health Studies on its 50th anniversary.

In many countries—especially developed ones like the United States—the accomplishments credited to public health are often taken for granted: access to clean water and air, vaccine availability, effective sanitation services, and safe food production. But the contributions of public health practitioners have improved, and in many cases saved, the lives of millions of people around the globe.

Here at Johns Hopkins, our world-renowned Bloomberg School of Public Health has played a huge role in alleviating countless diseases and conditions that are harmful to various populations. And for 50 years, undergraduates in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences have learned from and worked beside experts from the Bloomberg School.

Public health studies is now one of our largest and most popular majors. When it first debuted 50 years ago, 29 students declared the major. Today, it is home to more than 500 students. In fact, Hopkins helped pioneer the idea of undergraduates studying public health, and more and more colleges are looking to us as the model.

Our public health students are curious, driven, and passionate about the work they do and the research they conduct. They are eager to play a role in improving the lives of others and making a real difference in the world. Whether walking along the steamy banks of Uganda’s Lake Victoria talking to fishermen about their health concerns and poor working conditions, or sitting in a small room in Baltimore City helping low-income residents access the social services they so desperately need, our students are on the front lines. These applied experiences give them the kind of beyond-the-classroom exposure to public health issues that help prepare them for careers in public health.

As the planet’s population hovers near the 8 billion mark, public health challenges also grow, whether 7,000 miles away in equatorial Africa or several blocks away from the Homewood campus, in neighborhoods where the majority of people live below the poverty level.

With the Krieger School’s Program in Public Health Studies reaching its 50th-year mark, I can’t help but reflect on the impact our thousands of students have had—and will continue to have—on multiple global populations. Many of our graduates have gone on to graduate school, medical school, and health policy careers, where they will continue to advocate for positive health outcomes for all and action in the face of public health emergencies. This is their calling, and I am so proud of them.

I send warm wishes, heartfelt congratulations, and deep thanks for all of the students and faculty members associated with our public health studies.

Sincerely,

Christopher S. Celenza, Ph.D.

James B. Knapp Dean

Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

Johns Hopkins University

3

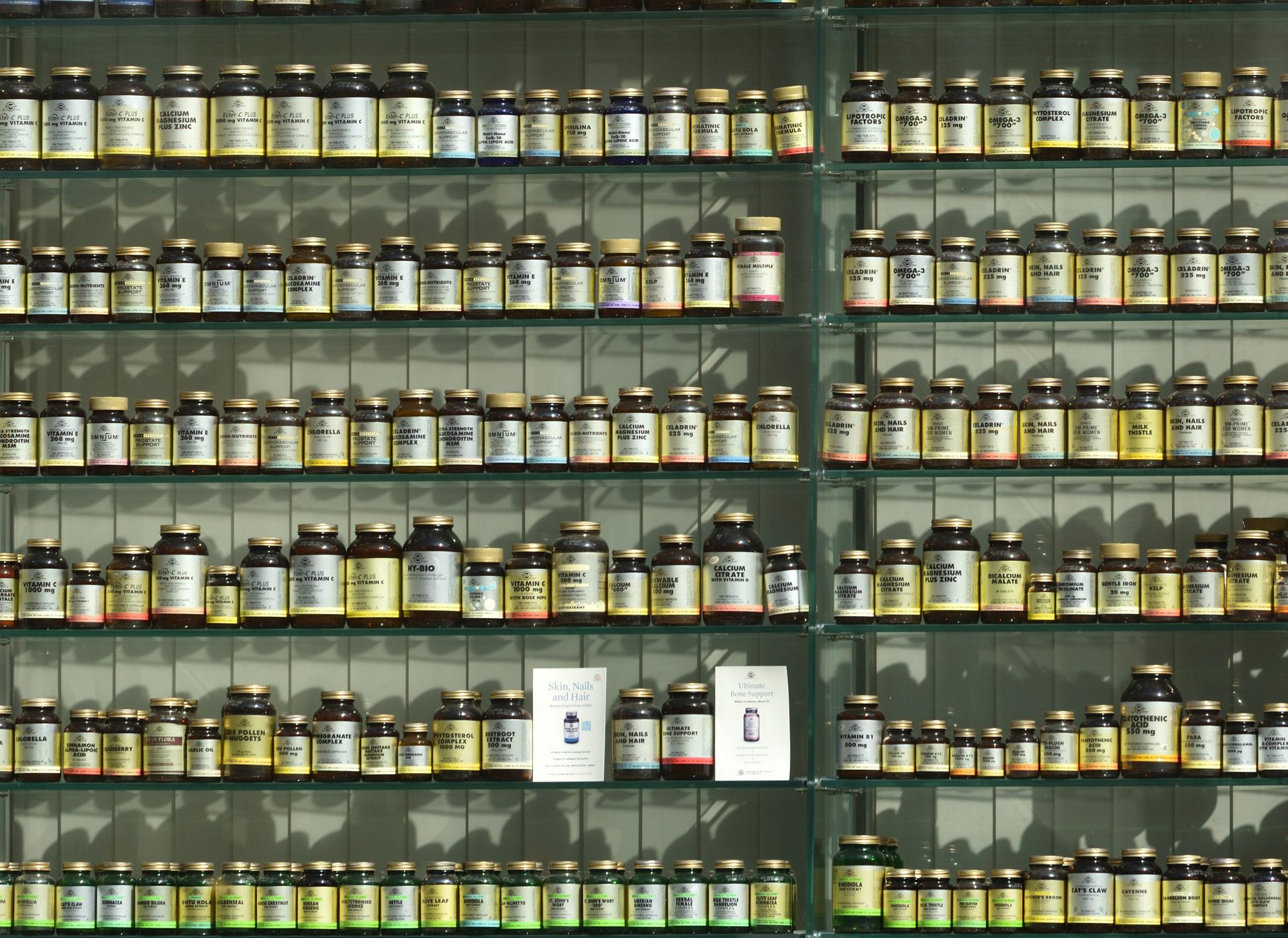

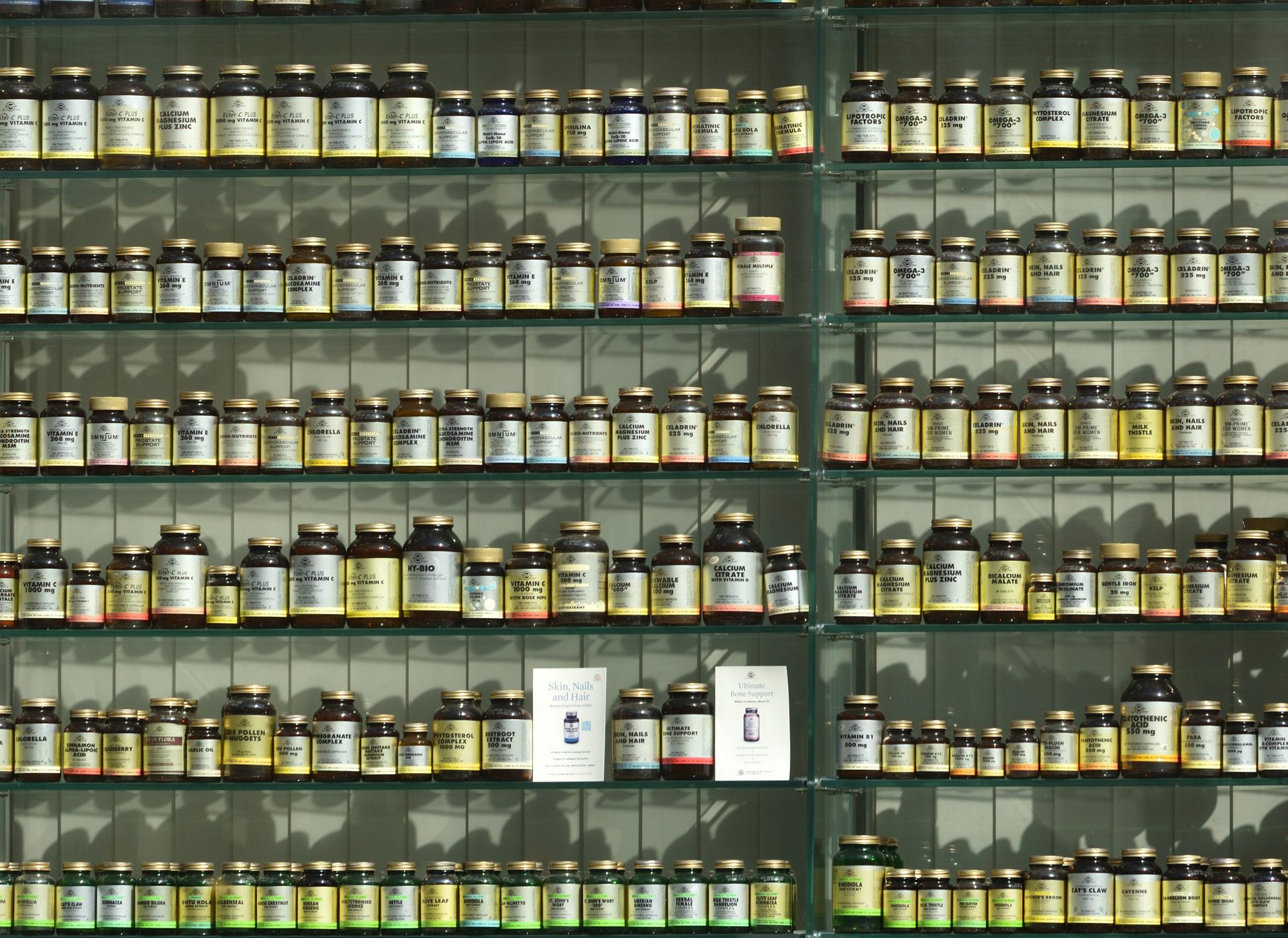

A Note on the Cover

Public health is not just about the confrontation between the destructive and powerful virus and the rapidly developing biomedical fields, but also the social construction of a system dealing with medicine administration, standardizing treatments, and resolving health disparities. By depicting cities of medicine containers and the collision between a virus and a robot, I hope to show the close relationships of public health issues with various other fields, including policy, biology, epidemiology, and hospital administration. The interdependence of multiple fields will be crucial for improvements in community health. Combining with the futuristic view, this issue will take us down a memory lane to appreciate previous Epidemic Proportions issues and the journey of discovering and discussing real-world issues.

-Rose Chen

4

Shannon Wang Zao

5

Shannon Wang Zao

Features

Shannon Wang Zao

Features

Shannon Wang Zao

Addressing Social Needs in Gynecology Oncology: Insights from a Hopkins Community Connections Advocate

Aminata Sinyan

Serving as a Hopkins Community Connections (HCC) advocate in the Summer of 2023 for the Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Services, a clinic that aids patients suffering from cancers or diseases of the female reproductive system, I addressed problems revolving around an individual’s social determinants of health (SDOH) and social needs. The Department of Health and Human Services defines SDOH as conditions in the environment where people are born, live, work, and age: all of which impact health, quality of life outcomes, risk, and an individual’s social needs (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2024). At HCC, we targeted multiple disparities faced by our Gynecology Oncology patients by connecting them to resources within the Baltimore community and beyond. A significant focus within the clinic was targeting the issue of food insecurity. Numerous referrals screened positive for food insecurity in their social needs screening. Throughout the experience, I will also highlight accomplished goals and share newfound perspectives that became clearer to me.

During my fellowship, my primary goal was to enhance adaptability in the patient care setting, navigating challenges that arose when juggling an increased workload and maintaining timely patient follow-ups. The pressure of failing to reach patients promptly led to heightened anxiety, prompting a pivotal decision to balance my time by reducing work hours and accommodating my other summer job. The GYN/ONC staff emerged as crucial pillars of support, playing an integral role in my journey. As I took on the responsibility of crafting

weekly emails detailing the number of enrolled patients, case closures, and triage patients for the Equity through Quality Improvement Partnership meetings, I found myself immersed in the narrative of healthcare dynamics. Beyond mere tasks, my goal extended to learning about diverse resources available to patients and their specific demographics, aiming to streamline referrals and integrate social needs screening seamlessly. Throughout the summer, my experience transformed from navigating struggles to making compromises and ultimately, to insightful observations. As I grappled with challenges, I honed my ability to comprehend patients’ situations, adeptly document them, and promptly identify appropriate resources.

reported 13.7 million households were food insecure, and 5.6 million experienced very low food security” resulting in some household members altering their food eating patterns (Gregory & Todd, 2021). This includes a reduction in food intake to accommodate for low funds in that area of expenses for lack of sufficient resources for food (Gregory & Todd, 2021). I encountered patients expressing the need to forgo specific meals each day due to insufficient resources to adequately support themselves or their families. These patients may have also been going through difficult health situations or In this case, food pantries, food stamps, and fresh food delivery services are the immediate line of action to address their needs. Expansion into

This journey not only fulfilled tasks but deepened my understanding of patients’ unique needs and the resources suitable to address them, fostering a more nuanced perspective in the realm of public health.

Delving further into this exploration, the research article, “SNAP Timing and Food Insecurity”, the “USDA

working with other community based organizations that help supply certain food pantries and food programs is how the work is upscaled—examples include Moveable Feast and Hungry Harvest.

Consequently, involving other community organizations and members allows for expanded outreach to

8

National Cancer Institute/Unsplash

patient needs. Targeting larger patient populations involves partnership with physicians, nurses, providers, and policymakers. Physicians, providers, and researchers delve into the impact of screening for social needs and referral outcomes. This allows for funding to accommodate the growing patient field and for more resources to address their needs. Research also provides evidence in support of legislation to target community members’ social determinants of health. Examples of such legislation include amendments to government benefits or even regulations within the hospital setting. Some amendments to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Food and Nutrition Service (SNAP) are one of the many ways that accessibility has been made easier for people in need of more food resources. While households can receive an average of “$258 in monthly benefits,” authors Gregory and Todd argue that this amount may not even be enough to curb food insecurity based on under-represented numbers of survey food scarcity and “declines in expenditures and dietary intake at the end of the benefit month” (Gregory & Todd, 2021). This is where additional support programs take effect for patients.

I gained substantial insight into the challenges faced by the lower middle-class population. GYN/ ONC patients in this socioeconomic bracket/class encountered difficulties: they were not affluent enough to manage the increasing cost of living, yet their income did not qualify them for assistance or benefits. In most cases, referred patients qualified for aid due to their lower income status. This facilitated easier connection to resources and approved assistance upon application review. However, individuals maintaining incomes just above subsistence struggled to meet the cost of healthcare, food, housing, and utilities. These patients live in precarious financial situations, heavily affected by the rising cost of living. Challenges not only lie in identifying

available resources for these patients, as fewer options cater to their needs due to eligibility. Grants, in addition to assistance, primarily benefit those experiencing those with severe financial hardship, a criterion posing greater difficulty in validation for middle-income patients. Witnessing these individuals ensure such challenging circumstances is not only disheartening for patients themselves, but also deeply distressing for the limited capacity to provide comprehensive support.

The experiential journey detailed as an advocate for HCC encapsulated pivotal themes in addressing social determinants of health and catering to the pressing social needs of Gynecologic Oncology patients. It helped illuminate the pervasive issue of food insecurity among patients, calling attention to its multifaceted impact on health outcomes. The micro-level interventions employed by HCC underscore the importance of tailored support for individuals, emphasizing the value of localized assistance strategies. The challenges faced by middle-income patients, falling within the gap of support systems, highlight the nuanced complexities of financial aid eligibility; revealing the inadequacies of existing programs. Ultimately, this narrative advocated for targeted interventions, increased collaboration, and policy amendments to bridge

“

They were not affluent enough to manage the increasing cost of living, yet their income did not qualify them for assistance or benefits.

gaps and provide more inclusive and comprehensive support for vulnerable populations facing health-related social hardships.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People. Social Determinants of Health. [Online]. Available at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health. Accessed January 20, 2024.

2. Gregory, C. A., & Todd, J. E. (2021). SNAP timing and food insecurity. PLOS ONE, 16(2), e0246946. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0246946

Organization Information

Moveable Feast

Moveable Feast’s food delivery program focuses on the vital role of nutrition in supporting clients’ health and disease-fighting efforts. The program’s dietitians and chefs collaborate to craft medically appropriate, nutritious, and delicious menus, prepared in a state-of-the-art kitchen using fresh ingredients. Although home visits are currently on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program utilizes a secure telehealth platform for nutrition counseling, where Registered Dietitian Nutritionists work with clients to create personalized nutrition plans, set realistic goals, and discuss lifestyle changes aimed at improving long-term health.

Hungry Harvest

Hungry Harvest’s food delivery program is a culinary adventure for those who love experimenting in the kitchen, embracing every color and shape of the harvest to bring joy and variety to their plates. The program focuses on rescuing farm-fresh fruits and vegetables that would otherwise go to waste, delivering them affordably and conveniently to your doorstep. Beyond the culinary experience, Hungry Harvest strives to make a positive impact by saving at least 10 pounds of food per delivery, closing food access gaps, and reducing environmental impact, contributing to a more sustainable future.

9

”

Grace House - My Experience Witnessing Recovery and Resilience Within New Orleans

Isabelle Jouve

Within minutes of arriving to shadow at Grace House, a long-term substance-use disorder treatment facility in New Orleans, a woman named “Allie” in her early fifties walked into the clinic. Her brilliant, blue eyes lit up the room, and she excitedly greeted me. I followed Allie and two medical students into a small exam room that smelled faintly of disinfectant.

After reviewing her medical history, we joined the facility’s internal medicine physician, Dr. Elyse Stevens, to develop Allie’s plan of care. Seated together at a round table, we sought to provide Allie with an army of support, empowering her journey towards recovery. Allie pulled out a lengthy hand-written list from her purse, detailing questions that had been left unanswered for far too long.

In each patient appointment I shadowed, I always noticed Dr. Steven’s tactful questioning, while simultaneously connecting a web of clues to a diagnosis. I also admired her ability to brighten up the atmosphere by encouraging Allie, who expressed her daily struggle to remain sober following decades of addiction. As Allie pointed to a massive lump on her lower stomach, she grimaced describing the pain she felt and her battle to obtain treatment.

Dr. Stevens then asked about her STI diagnosis and if she was still taking the medication listed in her chart to treat gonorrhea. Confusion shadowed Allie’s face as she asked, “What is an STI?” She only knew her medications by each pill’s color and shape, rather than their purpose. Allie had no idea what was happening inside of her own body.

Every patient I met at Grace House bravely shared their story, revealing obstacles such as access to transportation, difficulty finding child care, and a gap in health education. “Natalie”, 59, spoke about how her late cancer diagnosis caused life-long health issues, while “Christie”, a 28 year old mom, shared that she didn’t know she was pregnant until her third trimester. One key question prevailed: how could the women at Grace House advocate for themselves and effectively seek medical care without healthcare education on fundamental topics, such as STIs, cancer prevention, and menopause?

These patient interactions inspired me to create a reproductive healthcare workshop program for the residents. The program’s focus has been to provide an engaging, comfortable setting for residents to learn key health information and promote a proactive, rather than reactive, approach to their care. Understanding that it is unrealistic for residents to memorize facts from a two-hour workshop, my goal is to teach them how to identify and communicate their health concerns.

During workshop sessions, residents are often shocked upon learning fundamental health facts, such as the difference between menstruation and the menstrual cycle or that symptoms they have been experiencing for years are irregular. They will often remark that the workshop inspired them to discuss their newfound understanding and concerns at an upcoming clinic appointment, which is a pretty powerful outcome.

I have also observed that workshop sessions become safe spaces for residents to recount past medical

difficulties and hear others’ stories. A few weeks ago, “Natalie”, 25, shared that she had an IUD inserted at 18, but her provider refused to remove it after its expiration. Her IUD remained in place for two more years until excruciating pain sent her to the emergency room. Physicians found a 14-centimeter ovarian cyst, and she subsequently had surgery that resulted in her losing an ovary. Natalie expressed that education on birth control methods and potential complications as a teen could have prevented this.

“

The residents remind me why I decided to go into medicine in the first place, and I’m so thankful for the chance to work with them each week.

”

Since last summer, I have recruited a team of medical students and undergraduates to facilitate the workshop regularly. The program provides students the chance to gain meaningful patient interaction while becoming increasingly popular among the residents.

Rowan Miskimin, the director of the Grace House Student-Run Clinic, shared, “The residents remind me why I decided to go into medicine in the first place, and I’m so thankful for the chance to work with them each

10

week. The journey through recovery brings so many unexpected challenges, and these phenomenal women are all here choosing to love and care for themselves no matter what it takes. It’s a reminder to all of us to fight for our own joy and wellbeing, and to nurture the relationships that keep us going. It’s an honor to learn from Grace House residents and staff, and I hope to use my education to further support this wonderful place in the future.”

Over the last seven months, I have gotten to know so many women at Grace House who are survivors with unimaginable strength. I look forward to chatting with them in the hallways and witnessing their progress in recovery. The Grace House Workshop Program empowers the women we teach and honors their resilience. In the words of Dr. Elyse Stevens, “Taking care of women recovering from substance use is life-changing. It is tremendously humbling and eye-opening listening to the stories of women who have been through some of the most horrible moments imaginable. From the outside, other people don’t see the story behind how or why the patient fell into substance use. When you actually listen to what they have to say you realize that this could have been me - this could be anyone. What would I have done in that situation? Would I have even survived? I love that I get to celebrate with

these incredible women how strong and resilient they have been in order to survive all they have been through and come out thriving.” teach and honors their resilience. In the words of Dr. Elyse Stevens, “Taking care of women recovering from substance use is life-changing. It is tremendously humbling and eye-opening listening to the stories of women who have been through some of the most horrible moments imaginable. From the outside, other people don’t see the story behind how or why the patient fell into substance use. When you actually listen to what they have to say you realize that this could have been me - this could be anyone. What would I have done in that situation? Would I have even survived? I love that I get to celebrate with these incredible women how strong and resilient they have been in order to survive all they have been through and come out thriving.”

Organization Information

Grace House is a 24/7 residential treatment facility that provides substance-use disorder treatment women. With a male equivalent called Bridge House, both residential facilities provide programs that have continuum of care that aims to increase the quality of life of people with addictive disorders. While sobriety is the highest priority of treatment, Grace House also aims to rebuild client relationships with their family, friends, and the surrounding community.

Biography

Isabella Jouve is a Sophomore that is majoring in public health studies. She wants to focus on health policy in her career.

Community Close to Home: My Summer at Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition (BHRC)

Atri Surapaneni

On the first day of my summer internship with Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition (BHRC), I took a scenic stroll down Calvert Street to a row home, a small flier hung by its entrance. The place was home to a nonprofit that focused on the health, safety, and dignity of people in the Baltimore community who were affected by the war on drugs and the opioid epidemic. The three-story row home was deceptively spacious. Every corner was organized with shelves and supplies in a methodical chaos. For a few hours each day at BHRC, I spent time making a variety of safer drug use supply kits, Narcan kits, hygiene kits, and other essential items that were to be distributed. It was during these hours of repetitive motions and zipping up Ziplocs that I got to connect with my coworkers. Working in an assembly line made the process much more efficient and enjoyable.

It was during these times that I got to connect with my coworkers. One of my colleagues told me stories about his time playing college basketball, casually name-dropping a few future NBA talents he competed with. Being an avid basketball fan, I was enthralled by his stories of his team’s run to the semifinals of the NIT. Another one of my coworkers had been studying for the Bar exam while working, and one went to college for music and

11

Brother Swagler/Unsplash

skillfully played his guitar during a few lunch times. I was so fortunate to be welcomed by a passionate and diverse staff who created a collaborative environment and an enriching experience for me. Building camaraderie with my coworkers allowed me to help out on service shifts in the final weeks of summer.

During these shifts, I helped distribute snack bags and harm reduction supplies and filled out the blue sheets BHRC uses to keep track of how many kits were distributed. This experience prepared me for conducting BHRC’s satisfaction survey, where I got to speak with over a dozen Baltimore residents living near Maryland Avenue about BHRC’s services, how they get food, and their utilization and experience with governmental supplemental nutrition programs such as SNAP. Talking to community members was always memorable. My interactions and conversations while conducting the surveys had mixed feedback about the process of applying for SNAP and food stamps, but there were concerns about this decreasing funding each month, especially in a time of inflation and economic uncertainty. Prior to working on this project, I thought

that nonprofits and government were largely disconnected and sometimes at odds with one another, but I believe one of the responsibilities of nonprofits should be to collaborate and inform the government.

Organization Information

Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition, Inc. (BHRC) is a community-based organization located in Lower Charles Village, with a focus on harm reduction for people who use drugs or engage in sex work. Not only do they provide trainings, resources, and help advocate for harm reduction policies, but have a mission to address the war on drugs and anti sex-worker policies at individual, societal, and systematic levels.

An “Eye” Opening Experience

Tabatha Alegria

In high school, I worked as a medical technician which exposed me to patient care. I especially liked optometry because I felt like optometrists and assistants at their offices could build a long-term relationship with a patient. It always warmed my

heart to see how the optometrist and patients could talk freely about more than just medicine, like last night’s sports game or a recent event in the community. Although optometrists are doctors one should see annually, possibly more if one has any issues relating to vision such as dry eye syndrome, being able to establish this connection with each and every patient is something that amazed me.

I live in a community with a large Hispanic/Latinx population. As a Spanish speaker, I observed how language barriers and other healthcare disparities affected marginalized groups and decided to translate eye exam instructions and results to make eye care more accessible to my community. This experience along with one of the doctors in my office who majored in public health inspired me to major in the same field. She shared how much she enjoyed learning about the interaction between medicine and communities along with the inherent flaws of the US healthcare system, and this sparked a passion in me, and something I would like to combat by helping as many as possible overcome language barriers in healthcare so that medicine can truly reach everyone.

I want to be a part of public health research and public health activism at Hopkins. Research that works on studying and solving healthcare barriers for immigrants, and activism that directly involves these communities. I want to ensure that healthcare is truly for all; at Hopkins, I will work towards that goal.

12

Atri Surapaneni

Atri with members of the Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition.

13

Elen Sher/Unsplash

Hopkins Past the 21218: Baltimore, DC, and Beyond Habin Hwang, Features Team

“The university’s new home in Washington, DC – the Hopkins Bloomberg Center – offers a wonderful venue for public health studies courses and events. It’s just a short train ride from Baltimore, and hopefully it will foster the development of a truly bidirectional portal between our students, faculty, and staff in Baltimore and Washington, DC.” Lainie Rutkow, PhD, MPH)

‘What is Democracy?’

The question that welcomed the undergraduate Class of 2026 to Johns Hopkins University echoed into the opening of the DC Bloomberg Center in Aug. 2023. Formerly housing the Newseum, the museum of American journalism, Johns Hopkins’ dedication to further exploring this question is reflected in acquiring this collaborative space. With intent to streamline the world-class School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Krieger School of Arts and Sciences (KSAS), Carey Business School, and Peabody Institute, the space serves to integrate each of their strengths. Sandwiched between the U.S. Capitol building and the White House, the school is a beacon of education within the prestigious and diverse DC community.

Johns Hopkins acquired the Newseum building in 2019, and invested $650 M towards its acquisition and renovation. Shortly after its opening in 2023, school leadership declared their intent to open a School of Government and Policy there, and began offering undergraduate courses there through its Carey Business School and Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

“What this represents is the physical manifestation of the university’s commitment to national and international engagement,” said Ronald J. Daniels,

Hopkins’ president, to the Washington Post. “The idea was to create a place for the university in Washington proximate to power.”

Reflecting a “reciprocal connection” between DC and its surrounding community, the University not only hopes to create an infrastructure that promotes collaboration between students, but also increases student and faculty engagement with DC policymakers, analysts, and think tanks. While faculty and students would bring their expertise, passion for learning, and ideas to DC, the policymakers and analysts in the Nation’s Capitol would interact more regularly and deeply with the students of Johns Hopkins.

“

Students here have access to worldclass faculty doing research on just about every area of public health.

”

The first cohort of students who will be pursuing the 5th year Master’s Degree with SAIS will be matriculating to the campus in fall of 2026, while various undergraduate courses will be offered each semester until then.

“We are honored that the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center chose to open a new space on Pennsylvania Avenue in the heart of our downtown,” said Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser to Forbes. “We

have set the bold goal to win back our downtown by making Washington, D.C., a place for successful businesses and opportunity-rich neighborhoods. Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center brings a new hub for global leaders to convene, and new employment and educational opportunities to our downtown.”

Furthermore, the campus is exciting news for the faculty and students in the undergraduate Public Health Studies (PHS) department.

“There is no better place to study public health than Johns Hopkins,” stated Maria Bulzacchelli, director of the PHS department. “Students here have access to world-class faculty doing research on just about every area of public health. Hopkins also offers so many funding opportunities for students to pursue research—you don’t have that everywhere.”

With the opening of the interdisciplinary Bloomberg Center, students from various undergraduate programs will have opportunities to work directly on Capitol Hill with policy makers, and will give a new meaning to the “applied experiences” that the PHS department emphasizes. With the hopes of opening the doors for more valuable learning opportuni-

14

Raymond Zhang

ties for undergraduates, many faculty members have high hopes for what the Center will mean for the advancement of undergraduate PHS education.

“I can imagine students spending a semester in DC working with policy makers,” Dr. Bulzacchelli elaborated, “A lot of federal public health agencies have their headquarters in DC. And then of course there’s Congress— they are always debating legislation with public health implications.”

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, infrastructure and public health policy have become more important and relevant in the public eye. While it is the hope of everyone that another pandemic could be avoided, being able to better detect and respond to future pandemics by improving infrastructure and streamlining public health policy is one of the current goals of many at Hopkins. With the many bright minds to be housed in the new Bloomberg Center and the connections they will form with the community around them, Hopkins’ commitment to research, innovation, and discovery is highlighted in these many investments made.

Additional Information

The new DC building has a “beach” reminiscent of the one present on Homewood campus, where students can have informal and social gatherings in a common space. This space is present in the atrium of the building, and is surrounded by a “room stair” and a “room bridge.”

The DC building was originally the Newseum, a building that highlighted American journalism and its contribution to democracy. The building was reconfigured by the Ennead Design team led by architects Richard Olcott, Kevin McClurkan, Felicia Berger, and Alex O’Briant to highlight Johns Hopkins’ commitment to transparency, health, and wellbeing. In order to honor the Newseum and

all that it symbolizes towards the American Democratic process, Johns Hopkins ensured that the original Newseum building was as preserved as possible while highlighting the school’s mission and values.

Why

I (and Many Others) Chose to Double Major

Vivan Guo, Features Team

With a LinkedIn headline that reads ”Public Health & Anthropology at John Hopkins University,” I am more inclined to connect with those studying at least one of the aforementioned subjects. More often than not, it is the former major that I share with my fellow undergraduate classmates— an observation that holds even while sitting in my only Anthropology class this semester. However, it still excites me to know that in our graduation diplomas, there will be a line of subtext that reads: “with a secondary major in,” connecting Public Health Studies with other departments like Computer Science and Molecular and Cellular Biology that students endearingly refer to as MolCell.

From pursuing personal interests to fulfilling pre-med requirements, undergraduate students at Johns Hopkins cite a variety of reasons for pursuing a double major in addition to Public Health Studies. Thankfully, the versatility of interdisciplinary courses at the Bloomberg School of Public Health (BSPH) and Hopkins’ flexible major requirements encourage student exploration which can be reflected in some of the responses below:

Alina Galaria (Class of 2025) is currently pursuing a double major in Public Health and Natural Sciences and an Islamic Studies Minor. This interdisciplinary approach aligns with her aspirations to attend medical school and attain a master’s in Public Health.

Christine Kim (Class of 2025) is also a Molecular and Cellular Biology double major and pre-med student but for the exploration of “the macroscopic and microscopic aspects of health” through the combination of these disciplines.

Kevin Mao (Class of 2027 and fellow Epidemic Proportions editor) intends to double major in Molecular and Cellular Biology because “the major requirements overlap nicely with pre-med requirements.” He mentions how the combination of these majors touches on mental health, medicine, and public health, making it an ideal path for pursuing forensic psychiatry.

Tabatha Alegria (Class of 2027) plans to double major in Spanish to “learn more about her Latina culture,” motivated by her future aspiration for a job in healthcare. The application of such knowledge would facilitate meaningful interactions with patients in multicultural settings.

Personally, I, Vivian Guo (Class of 2027), hope to delve into the field of Urban Planning by leveraging the offerings at the Bloomberg School of Public Health (BSPH) and the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences’ Anthropology department. For those contemplating a public health double major, consider how the field offers unparalleled versatility. The holistic understanding of various health disciplines allows students to prioritize academic interests that resonate with them— even more so with an additional major.

15

Looking Back, Looking Forward - the Past 50 Years of Undergraduate Public Health Education

Habin Hwang, Features Team

“A couple of decades ago, when— for the most part—public health education was available only at the graduate level, a lot of people ended up in public health later in their careers, discovering the field only after starting their working life in something else. Offering public health education at the undergraduate level means the field can attract bright and passionate young people at the start of their careers.”

-Maria Bulzacchelli, Director of Undergraduate PHS

In the first half of the 20th century, Public Health education was first marketed as a graduate level track designed for medical professionals striving to take on governmental public health roles. The School of Hygiene and Public Health (now Bloomberg School of Public Health) was established for this purpose in 1916 as one of the first graduate education programs for Public Health. Though its establishment was groundbreaking towards Public Health education as we see it today, education was not geared towards undergraduates, and MPH’s were solely offered as a graduate level track.

However, with Dr. Abraham Lilienfield’s advocacy for public health topics, namely epidemiology, to be taught at the undergraduate level, the School of Public Health (SPH), in collaboration with the undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences, began laying the groundwork for the undergraduate Public Health Studies major.

Johns Hopkins University’s School of Arts and Sciences began offering a B.A. degree in Public Health Studies (PHS) with an emphasis in either natural or social/behavioral sciences in 1974, the first in the nation to accom-

plish the feat. Many other liberal arts universities followed suit shortly after in establishing their own undergraduate PHS departments.

Within the next five years, the number of graduating seniors increased from under 25 to nearly 75, making it one of the most popular majors at the School of Arts and Sciences. With the full support of John Chandler Hume, the Dean of SPH from 1967-1977, undergraduates were encouraged to take graduate level classes. The growth of the major was additionally caused by the rising interest in community service, as well as the newly added full time advising programs.

Despite its rapid growth, the PHS department didn’t hit its breakthrough until the early 2000’s. In 2000, the major’s core curriculum was rewritten to include statistics, epidemiology, environmental health, health policy and management, biology, english, and calculus. Furthermore, a critical marriage was made between the SPH and PHS department that exists to this day, requiring students to take at least

one year of elective graduate courses at the SPH.

“About ⅔ of my [undergraduates] are second-generation immigrants,” stated Dr. Peter Winch, who currently teaches at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. “Often their interest in public/global health starts from seeing how their relatives in their parents’ homeland are served or not served by the health system. Whereas if you look at the graduate students, many of them have been out working already. They have work experience, while the undergraduates have more family experience. Both kinds of experiences are very important.”

The growth in the early 2000’s was also accompanied by the movement to increase accessibility for undergraduate public health education. Between the years of 2003 and 2005, the then Association of Schools of Public Health (ASPH)* established the Undergraduate Public Health Task Force, which advocated for the many accredited programs across the nation. In 2006, the Council of Colleges of Arts

16

Dr. Bulzacchelli and Dr. Winch (Dr. Winch is receiving the Golden Apple award in May of 2023)

and Sciences sponsored the Consensus Conference on Undergraduate Public Health, leading to a stronger national cohesiveness in ‘101’ and core courses in the field of public health.

*Footnote: the ASPH became the ASPPH in 2013

In the past two decades, the B.A. in Public Health has evolved to include an applied experience as a degree requirement, where students could gain hands-on experience with experienced professionals in the field. The major increased rapidly in popularity over the years due to how it was flexible and adaptable, in addition to adapting well to the pre-medical curriculum.

“Another thing that happens—and this is not something we do on purpose—but another thing is that some students who come to Hopkins on the pre-med track discover public health and realize they can help people and do something health related without necessarily working in a clinical setting,” stated Maria Bulzaccheli, the current director of the undergraduate PHS department. “Offering public health education at the undergraduate level means the field can attract bright and passionate young people at the start of their careers.”

With over 500 declared PHS majors today, a vibrant community has formed at Hopkins since the conception of the department in 1974. Currently, fourth year students in the department can take classes at the SPH in all 10 areas, and can gain exposure to public health topics in the following areas: health education, environmental health sciences, epidemiology, health finance and management, health policy, human genetics, immunology and infectious diseases, international health, maternal and child health, mental health, nutrition, occupational medicine/health protection and practice, population studies, toxicology, and tropical medicine among others.

“I really think [public health education] creates students who are more well rounded in their understanding of how people make choices around their health and the ways interventions either work or don’t work for human health,” stated Dr. Margaret Taub, who teaches Biostatistics to PHS undergraduates. “It gives this perspective that there are so many factors outside of individual physician interactions with patients that determine people’s health. And all of those things are really important to keep in mind.”

Most recently, the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue was established, with its opening in August of 2023. Though it is primarily associated with the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), PHS officials hope to open up more opportunities for students to interact with public health policymakers and to explore more interdisciplinary policy-centered fields.

Additional information

Abraham Lilienfield, MD, MPH

Dr. Abraham Lilienfield’s, one of the “founders’’ of the undergraduate PHS department, was one of the main contributors towards the 1982 Surgeon General’s report stating that smoking was harmful for health. He also is known as the “father of contemporary chronic disease epidemiology.”

According to the Bloomberg School of Public Health, ‘Dr. Lilienfeld’s students and colleagues recall his “singular lack of self-interest, great willingness to help others, and tireless devotion to the advancement of public health science.”’

Maria Bulzacchelli, PhD

Dr. Bulzacchelli, often endearingly referred to by her students as Dr. B, had her beginnings at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. Prior to entering graduate school she held positions at the Harvard School of Public Health and Massachusetts General

Hospital. After getting her doctorate degree at the School of Public Health, she adopted the PHS director position in 2016. Her research primarily focuses on injury prevention and workplace safety.

Peter Winch, MD, MPH

Dr. Peter Winch currently teaches seminars in Global Sustainability and Health at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. His research and work primarily focuses on global health.

References

1. Brieger H, Gert. Goodyear D, James. C. Public Health Studies: A Popular New Major at Johns Hopkins University. In: The 129th Annual Meeting of APHA ; 21 Oct. 2001; Atlanta, Georgia. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://apha.confex.com/ apha/129am/techprogram/paper_29685. htm

2. Garcia X, Martinez Y, Rodriguez Z. Undergraduate Public Health Studies at Johns Hopkins. In: The 131st Annual Meeting of APHA; 15 Nov. 2003. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://apha.confex.com/ apha/131am/techprogram/paper_73844. htm

3. Riegelman RK, Albertine S, Wykoff R. A history of undergraduate education for public health: from behind the scenes to center stage. Front Public Health. 2015;3:70. Published 2015 Apr 27. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2015.00070

4. Johns Hopkins University. Public Health Studies. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://e-catalogue.jhu.edu/arts-sciences/full-time-residential-programs/degree-programs/public-health-studies/

5. Johns Hopkins University. Public Health Studies: Fifty Years of Excellence. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://krieger. jhu.edu/publichealth/about/fifty-years/

17

Editorials

Shannon Wang Zao

The Gun Violence Epidemic: Why This Issue Is More Severe Than We Realize

Samuel Yeboah-Manson

The National Rifle Association (NRA) is an important organization to understand this issue. The NRA was originally a recreational group aimed at encouraging rifle shooting on a scientific basis.2 Today, the NRA has 5.5 million members and trains one million gun owners annually.2 Most importantly, this organization is heavily involved in lobbying, spending $2.5 million on advocating for legislation that expands access to guns.3 According to the NRA, since 2013, 382 “pro-gun” bills have been enacted.4 Such laws have been adopted by the Governors in Arkansas, Georgia, and Texas, which have allowed people with concealed carry licenses to bring guns into public spaces like college campuses.

One reason gun violence should be declared an epidemic is that it meets the very definition of one. Although gun violence is not an infectious disease that can not be diagnosed or treated, gun-violence related deaths certainly reach numbers close to that of various diseases. In 2021, while 56,000 individuals died from chronic liver disease, gun violence took the lives of almost 48,000 individuals.4,5 Given these comparable numbers, it is safe to say that the burden of gun violence is significant and warrants extreme attention. The effects of gun violence also mirror those of any conventional infectious disease. Victims of gun violence often suffer from long-term physical and psychological effects, either from being shot and injured or from witnessing these events. Victims and bystanders alike are likely to experience stress, depression, and PTSD.6 These effects may be further exacerbated by the lack of accessible mental health care in the

United States; 42% of the population sees the cost of mental health services and poor insurance coverage as a barrier to obtaining necessary mental health services.6

The overall firearm death rate in the United States is ten times higher than in other high-income countries.7 Furthermore, the number of people dying from mass shootings in the U.S. surpasses that of other countries. 82% of all firearm deaths in two dozen populous, high-income countries, occurred in the United States; additionally, 91% of children ages 0-14 who were killed by firearms were from the United

“

Incidents of gun violence are only increasing in the United States.

”

States.8 Gun violence not only affects the victim, but also affects everyone around them, including parents, siblings, friends, and other members of their support system. Furthermore, the financial toll of gun violence is compounded by the already high cost of healthcare. According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, expenses associated with the aftermath of gun violence like medical bills, daily care/support, and criminal justice expenditures cost the United States economy approximately $229 billion annually.8

Enumerating the reasons why gun violence is an epidemic is certainly

satisfactory and constructive, but it does nothing if we do not propose solutions to end this issue. Overall, gun violence needs to be addressed with evidence-based strategies that also take into account the input of the communities in which its effects are disproportionately felt. Instead of blaming gun violence on mental health, which exacerbates already existing stigma and prevents others from seeking care, we should focus on understanding systems of violence that make people more likely to act violently. Scientists should work with leaders in disenfranchised communities to develop interventions that reduce risk factors responsible for gun violence. Overall, we need a community-based and scientific approach.

Reducing the risk factors that can lead to gun violence is a good first step when it comes to reducing the actual incidence of gun violence. Additionally, advocacy for these issues is also a great first step. Institutions like The Center For Gun Violence Solutions at Johns Hopkins University are using research to inform advocacy for greater gun legislation by directly engaging with affected communities to implement changes, further involving disenfranchised groups in the process and tackling the systematic causes of firearm-related violence rather than putting band-aids over bullet holes.9 Their research provides a contextual and scientific basis for defining—and even solving—an issue, but such research is futile if we do not know if it is effective or not. We must invest in ways to evaluate the effectiveness of developing strategies to improve the safety of individuals, families, and larger communities.

20

In conjunction with research and assessment, legislation is also essential to addressing this epidemic. One way to achieve this goal is by passing a prevention policy that serves as an effective foundation. Such a policy includes an universal background check law, which effectively works by preventing firearms from reaching the hands of dangerous individuals. Passing strong laws that also promote equitable enforcement of specific gun laws should also be a top priority.

Some people who do not view gun violence as an issue often state that the second amendment guarantees all Americans the right to bear arms. However, these people fail to consider the potential consequences of an amendment established over two hundred years ago. It is improbable that the founding fathers of the United States envisioned the use of assault weapons in the tragic and senseless loss of lives, endangering the very right they aimed to safeguard—the right to live.

References

1. National Rifle Association. About the NRA. Nra.org. Published 2023. https:// home.nra.org/about-the-nra/

2. OpenSecrets. National Rifle Assn Lobbying Profile. OpenSecrets. Published 2023. https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/clients/summary?id=D000000082

3. PBS NewsHour. NRA Has Backed Most State Gun Laws Passed since Sandy Hook. PBS NewsHour. Published March 2, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/ nra-has-backed-most-state-gun-lawspassed-since-sandy-hook

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats. CDC. Published October 11, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/ liver-disease.htm

5. National Council for Mental Wellbeing. Study Reveals Lack of Access as Root Cause for Mental Health Crisis in America. National Council for Mental Wellbeing. https://www.thenationalcouncil. org/news/lack-of-access-root-cause-mental-health-crisis-in-america/#:~:text=Mental%20health%20services%20in%20 the

6. Harvard Injury Control Research Center. Overall. Harvard Injury Control Research Center. Published August 27, 2012. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://www. hsph.harvard.edu/hicrc/firearms-research/overall/#:~:text=The%20overall%20firearm%20death%20rate

7. AAFP. Gun Violence, Prevention of (Position Paper). aafp.org. Published 2018. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/ gun-violence.html

8. CDC. Funded Research. cdc.gov. Published 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/firearms/funded-research. html

Author Biography

Samuel Yeboah-Manson is a freshman at Hopkins majoring in Public Health and Molecular and Cellular Biology. He is particularly interested in the social determinants of health and healthcare policy. Outside of his academics, Samuel is an avid reader and enjoys spending time with friends and family.

21

Jay Rembert/Unsplash

Revolutionizing Healthcare: A Proactive and Patient-Centric Approach to Preventable Chronic Conditions

Jayvik Joshi

Almost half of all adults, 117 million Americans, suffer from preventable chronic conditions that can be linked to poor diet and lifestyle choices.1 These conditions not only diminish quality of life, but account for more than 85% of all health care costs,2 which for the US is almost double per capita compared to other developed countries.3 This epidemic demands an urgent need for a comprehensive approach to address the root cause of these chronic issues.

The solution lies in moving away from our reactive system to a proactive and personalized approach. Although most individuals resort to life-saving medical interventions, maintaining a healthy lifestyle through adequate nutrition and physical activity could at times prevent the very diseases we seek out to treat. New technologies aiming to tackle these problems have also begun to signal a paradigm shift towards patient-centered care, prioritizing long-term well-being over transient treatments.

Our health hinges on the day-to-day choices we make. Many individuals are raised in environments that overlook the enduring consequences of lifestyle decisions, leading to longterm repercussions. When it comes to addressing conditions like heart disease, obesity, or cancer, it may seem like only miraculous interventions can make a difference. However, the cumulative effect of small lifestyle choices can have a significant impact over time and play a crucial role in preventing potential health complications. Our laxity towards nutrition and lifestyle is demonstrated by concerning realizations. America is littered with food deserts not only contributing to the 1 in 5 children experiencing mal-

nutrition4 but also the rising 42% obesity rate.5 Nearly 60% of the American diet consists of ultra-processed foods linked to obesity, diabetes, and cancer.6 Light physical activity is linked to a 20-30% decrease in all-cause mortality7; however, more than 60% of US adults do not engage in 150 minutes of activity per week likely caused by widespread sedentary lifestyles.8 With recent breakthrough drugs such as Tirzepatide for obesity9 or Lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease,10 we must not overlook the importance of nutrition and physical activity even when medical interventions are available as options.

Many recent healthcare technology advancements attempt to emphasize proactive, continuous monitoring and personalized care when and where it’s needed. Wearable devices such as an Apple Watch or Fitbit not only track day-to-day activities to encourage physical activity,11,12 but also enable early detection of complications such as cardiovascular irregularities.13 DexCom’s continuous glucose monitoring systems allow for close tracking for diabetic patients.14 These solutions allow for continuous feedback, timely intervention, and encourage long-last-

ing habits that compound over time. The recent surge in artificial intelligence has enhanced remote patient monitoring through diet or mental health monitoring apps backed by deep learning models.12 Generative AI, such as ChatGPT, has valuable applications in increasing accessibility of medical information and educating patients on healthcare literacy - ultimately empowering more people to take control of their health.15 Other innovations such as Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) demonstrate promising applications in healthcare. Possible applications include personalized rehabilitation exercises for motor skill enhance-

“

” Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) demonstrate promising applications in healthcare.

ment, mental health therapy for anxiety and stress management, exposure therapy for phobias and PTSD, and VR-assisted pain management.16 The personalized and remote nature of such technology allows for a seamless integration of treatment into a person’s social and cultural constraints. By embracing these innovations, healthcare has begun to shift away from a “when it’s needed” and “one-size fits all” approach and evolve towards a future that is active and patient-centric.

22

Eiliv Aceron/Unsplash

As technology rapidly integrates into our daily lives, the swift rise of AI and advancement of personalized medicine signifies a profound shift in the fundamental roots of our healthcare system. The emergence of these solutions underscores a commitment to continuous feedback, personalization, and a point-of-care approach, offering a substantial enhancement in the overall quality of life. A focus on the accumulative effect of healthy lifestyle choices as a mode of disease prevention rather than a reliance on therapeutic interventions continues to serve as an indispensable, yet commonly forgotten guiding principle. This shared vision not only reshapes healthcare into a proactive partnership between providers and patients but also champions long-term well-being as a central goal.

References

1. Food Is Medicine: A Project to Unify and Advance Collective Action | health.gov. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://health. gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/ food-medicine

2. Holman HR. The Relation of the Chronic Disease Epidemic to the Health Care Crisis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(3):167-173. doi:10.1002/acr2.11114

3. U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes. doi:10.26099/8ejy-

yc74

4. Hunger in America | Feeding America. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www. feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america

5. Overweight & Obesity Statistics - NIDDK. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.niddk.nih. gov/health-information/health-statistics/ overweight-obesity

6. Steele EM, Baraldi LG, Louzada ML da C, Moubarac JC, Mozaffarian D, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009892. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009892

7. Indicator Metadata Registry Details. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www. who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadataregistry/imr-details/3416

8. Adults | Surgeon General Report | CDC. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www. cdc.gov/nccdphp/sgr/adults.htm

9. Wadden TA, Chao AM, Machineni S, et al. Tirzepatide after intensive lifestyle intervention in adults with overweight or obesity: the SURMOUNT-3 phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2023;29(11):2909-2918. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02597-w

10. van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa2212948

11. Ferguson T, Olds T, Curtis R, et al. Effectiveness of wearable activity trackers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Digit

Health. 2022;4(8):e615-e626. doi:10.1016/ S2589-7500(22)00111-X

12. Bohr A, Memarzadeh K. The rise of artificial intelligence in healthcare applications. Artif Intell Healthc. Published online 2020:25-60. doi:10.1016/ B978-0-12-818438-7.00002-2

13. Moshawrab M, Adda M, Bouzouane A, Ibrahim H, Raad A. Smart Wearables for the Detection of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors. 2023;23(2):828. doi:10.3390/s23020828

14. Garg SK, Kipnes M, Castorino K, et al. Accuracy and Safety of Dexcom G7 Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Adults with Diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022;24(6):373-380. doi:10.1089/ dia.2022.0011

15. Dave T, Athaluri SA, Singh S. ChatGPT in medicine: an overview of its applications, advantages, limitations, future prospects, and ethical considerations. Front Artif Intell. 2023;6:1169595. doi:10.3389/ frai.2023.1169595

16. Yeung AWK, Tosevska A, Klager E, et al. Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Medicine: Analysis of the Scientific Literature. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e25499. doi:10.2196/25499

Author Biography

Jayvik Joshi is a sophomore studying Biomedical Engineering. My career goals are oriented towards translational research and applications of engineering to medical and public health problems.

23

Michael Dziedzic/Unsplash

Telemedicine: The Future of Patient Consultation

Hyeongmin Cho

Telemedicine has been a rising field in healthcare. The American Medical Association (AMA) notes that telehealth visits and remote patient monitoring increased from 14% to 28% from 2016 to 2020.1 Since the Covid-19 pandemic, it is estimated that about 60-90% of physicians use some sort of telehealth service. Needless to say, telemedicine is becoming a significant part of healthcare, and it has the potential to drastically develop and improve patient access to healthcare in the future.

Telemedicine is the practice of providing remote healthcare to patients, whether that entails going through lab results, providing mental health treatment, or guiding physical therapy. Telemedicine uses relatively less

resources than typical in-person clinic visits.2 Analysis from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimates that patients save on average $147 to $186 per visit through using telemedicine.3 Because in-person visits are not required for telemedicine, patients can potentially save time and money on hospital and travel expenses, especially for those living in rural communities or places distant from clinics. Indeed, the same study from the NCI states that patients save about 2.9 hours of driving time and 1.2 hours of in-clinic time per visit when switching to telemedicine.3

However, work is still needed to ensure that telemedicine remains a valid option for healthcare. There are many regulations that disincentivize or dis-

courage healthcare providers from offering telemedicine as an option.1 The initial Public Health Emergency response to COVID-19 had all 50 states waive certain aspects of their state telehealth licensing requirements for physicians.4 However, some states are now discontinuing cross-state licensing waivers, preventing physicians from providing continuity of care to certain populations, such as college students who study in a different state.4 Additionally, obtaining in-state licensure to practice can be associated with fees and lengthy processes, such as an estimated 60-day wait for all states and all health providers before becoming licensed.4 Still, the AMA has supported the continued use of telemedicine, and there is currently ongoing work to lift restrictions

24

National Cancer Institute/Unsplash

and enable remote care.1 For instance, some states have broadened crossstate licensure by recognizing licenses in other states, and multi-state licensure compacts are being utilized to simplify the licensing process in many states through a common application system.4 These compacts enable certain healthcare providers such as physicians, nurses and speech therapists to continue telemedicine in other states as long as they hold licensure in their home state.4

“Public trust and satisfaction with telemedicine are high.

”

Access to telehealth has increased in recent years, with Medicare now accepting rural emergency hospitals as eligible sites for telemedicine.5 However, there are concerns that the lack of in-person interactions may increase the difficulty in building trust and comfort in patient-physician relationships.2 Still, case studies performed during the pandemic in major metropolitan areas, such as Los Angeles, have demonstrated that public trust

and satisfaction with telemedicine are high, about 47% for study participants, suggesting the validity of telehealth as a future avenue of healthcare.6

Overall, there is much optimism about the future of telemedicine in healthcare. The convenience afforded by telemedicine has allowed physicians and other healthcare workers to provide care and maintain communication with many patients who were medically or socially unable to visit clinics.2 A remote patient monitoring system may serve as a safety net for many patients, especially for the elderly or those living in hospice care who may have a harder time visiting clinics but still need regular care.2 Furthermore, the low-resource nature of telemedicine offers a financial incentive for both providers and patients seeking care, as costs may often be lower than in-person care.2 In fact, due to such advantages, a local Baltimore hospital, MedStar Union Memorial Hospital, is currently offering telemedicine as an affordable and accessible alternative to in-person care. Eventually, telemedicine may assist in providing primary care and help patients with chronic conditions that need regular monitoring and care.2 Telemedicine is becoming increasingly relevant in the public health and healthcare sector, and has the potential to revolutionize and improve patient care.

References

1. Strazewski L. Telehealth’s post-pandemic future: Where do we go from here? American Medical Association. Published September 7, 2020. https://www.amaassn.org/practice-management/digital/ telehealth-s-post-pandemic-futurewhere-do-we-go-here

2. Jin MX, Kim SY, Miller LJ, Behari G, Correa R. Telemedicine: Current Impact on the Future. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9891. doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9891

3. Winstead E. Telehealth Can Save People with Cancer Time and Money - NCI. www. cancer.gov. Published February 16, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/ cancer-currents-blog/2023/telehealthcancer-care-saves-time-money

4. Department of Health and Human Services. Getting started with licensure | Telehealth.HHS.gov. telehealth.hhs.gov. Published 2023. https://telehealth.hhs. gov/licensure/getting-started-licensure

5. Department of Health and Human Services. Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency | Telehealth.HHS.gov. telehealth.hhs. gov. Published August 31, 2023. https:// telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/telehealthpolicy/policy-changes-after-the-covid-19public-health-emergency

6. Orrange S, Patel A, Mack WJ, Cassetta J. Patient Satisfaction and Trust in Telemedicine during the COVID-19 Pandemic (Preprint). JMIR Human Factors. 2021;8(2). doi:https://doi. org/10.2196/28589

Author Biography

Hyeongmin Cho is a second-year undergraduate studying Molecular and Cellular Biology. He is particularly interested in health disparities, especially those found in the healthcare costs and health insurance. Using his love for writing, he hopes to contribute towards disseminating public health knowledge through writing as an editor for Epidemic Proportions.

25

National Cancer Institute/Unsplash

The Impacts of Climate Change on the Future of Public Health

Pearl Shah

Despite being an ever-present and looming threat for the past few decades, we have only recently started to get a glimpse of the long-term consequences climate change might have on our everyday lives. These effects manifest in a variety of ways, from extreme weather conditions to changes in food safety, threatening to change the ways we experience the world around us. In fact, climate change is estimated to cause a staggering 250,000 deaths between the years 2030 and 2050.1 This will mean large changes in the state of public health and the healthcare system as a whole.

Firstly, an increase in average temperatures will result in more frequent heatwaves, especially in the summer. This is particularly concerning for regions with infrastructure lacking air conditioning or ventilation, which are not equipped to handle such conditions. Heat exposure impacts include dehydration, heat cramps, heat strokes, increased cases of food and waterborne diseases, and the development of chronic diseases, such as respiratory, cardiovascular, and renal disease. Moreover, higher temperatures raise storage concerns for drugs, as it could make certain medications less effective or have adverse side effects.2

Climate change and the activities that contribute to it also lead to changes in air composition through an increase in the abundance of certain gases, allergens and particulate matter.3 Warmer temperatures have the effect of increasing ground-level ozone, which causes respiratory issues by harming lung tissue and impairing lung function. Changes in the timing and the length of pollen season due to warmer spring temperatures, like that of ragweed, increase allergens present in the environment. Further-

more, the inhalation of particulate matter produced by human activities, such as burning fossil fuels or wildfires, has shown to cause an increase in lung cancer and cardiovascular diseases. These factors come together to demonstrate how the worsening of air quality via climate change can have various health implications.

In addition, changes in temperature and weather have led to more cases of vectorborne diseases by allowing disease vectors to be active across larger regions for longer periods of time. For example, with rising temperatures, ticks carrying Lyme disease have been able to move northward and become active for a longer season.3 As warmer temperatures favor the growth of pathogens, microbial contamination of food and water can result in gastrointestinal issues and nutritional deficiencies. Flooding caused by extreme precipitation and rising sea levels can also cause heavy metal and chemical contamination of water bodies used for drinking or harvesting crops. Additionally, rising carbon dioxide levels have been shown to lower nutrition levels in food, such as decreasing protein and mineral levels.4

Extreme weather conditions, ranging from excess precipitation to droughts, will have long-term impacts on healthcare provision both during and after the incident. Specifically, extreme weather conditions often hinder access to basic resources by decreasing the availability of uncontaminated food and drinking water. These conditions also damage infrastructure, including roads and power lines, for transport and communication needed to gain access to healthcare facilities, such as pharmacies and hospitals. Supply chain disruptions could likewise occur due to the inability to produce and distribute medical supplies. Possible power outages es-

pecially threaten patients who require constant care, such as those on life support that dependent on electricity.

In conclusion, climate change is projected to have many adverse effects on public health - a reality we must begin to anticipate and prepare for. However, despite the seemingly morbid glimpse of the future, there is a big opportunity to adapt and prevent these repercussions. The healthcare industry itself is a major contributor to this phenomenon through its resource-intensive and waste-generating nature, and it is something we must begin to work on to change.

References

1. World Health Organization . Climate Change. Published October 30, 2021. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www. who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ climate-change-and-health

2. World Health Organization. Heat and Health. World Health Organization. Published June 1, 2018. https://www. who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ climate-change-heat-and-health

3. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Climate Impacts on Human Health. climatechange.chicago.gov. Accessed January 7, 2024. https://climatechange.chicago.gov/climate-impacts/ climate-impacts-human-health#:~:text=Climate%20change%20can%20 affect%20human

4. USGCRP. The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment. Globalchangegov. Published online 2016:1-312. https://health2016.globalchange.gov/

Author Biography

Pearl Shah is a freshman majoring in Molecular and Cellular Biology. She is also interested in the environmental sciences and its related issues, which is something she aims to spread more awareness about through her writing. Outside of Hopkins, she enjoys painting and reading.

26

27