Ranchers bullish on record-setting beef prices ........................... 4

‘Unprecedented’ market a boon for Baker County’s biggest industry.

‘The sky’s the limit’ .............................................................................. 6

Teenagers learn about agriculture drones at trades career fair.

Dam removal gives steelhead a fighting chance ........................ 8

Project on Fox Creek intended to create spawning, rearing habitat for anadromous and resident fish.

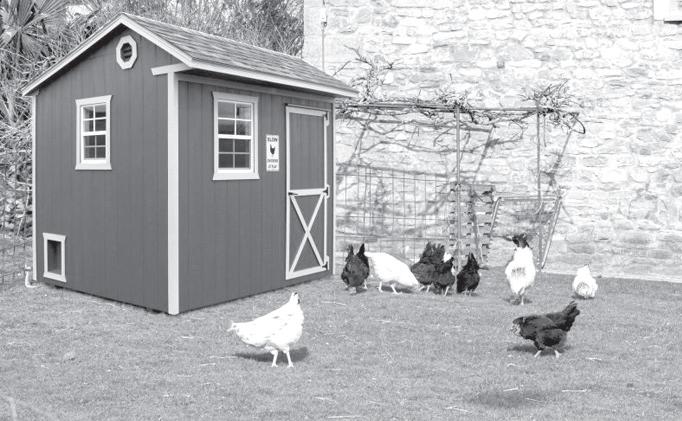

Farming in photos.............................................................................. 10

Umatilla County-based photographer documents agricultural life.

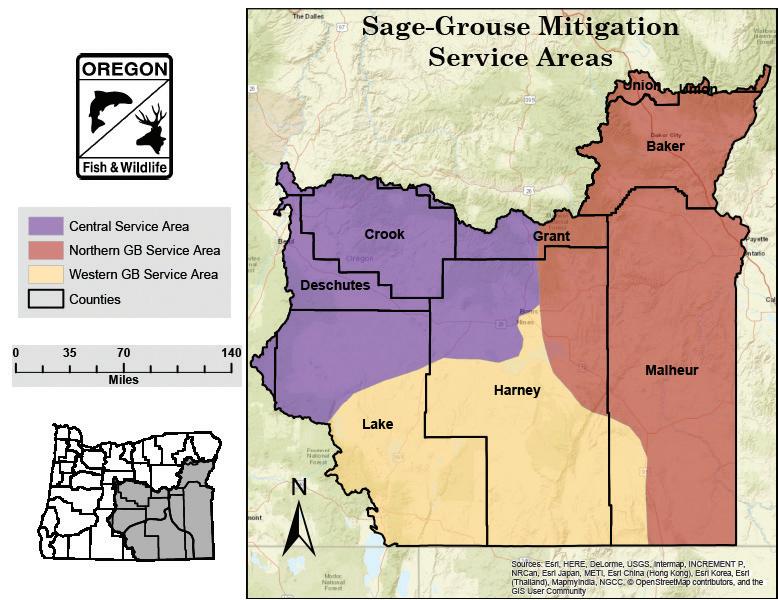

Oregon’s first sage grouse ‘conservation bank’ operating .....12

Owners of land in Baker, Malheur counties, by maintaining quality sage grouse habitat, can sell credits to developers whose projects would harm sage grouse.

Wallowa County farmers satisfied with yields ............................16

Growers don’t believe tariffs have had major effect.

Editor: Jayson Jacoby

Contributors: Jayson Jacoby, Berit Thorson, Isabella Crowley, Bill Bradshaw, Justin Davis and Lisa Britton Published by East Oregonian

U.S. Drought Monitor | Oregon October 14, 2025 (released Thursday, Oct. 16, 2025. Valid 8 a.m. EDT)

On the Cover: A black Angus cow grazes in Bowen Valley near Baker City, the Elkhorn Mountains in the background, on a frosty October morning.

Lisa Britton/ Baker City Herald

Every year is different for farmers and ranchers, but 2025 has distinguished itself in that regard.

Record-high prices for cattle have been a boon for ranchers.

But wheat growers are dealing with nearly the opposite situation.

A soggy autumn and early winter in 2024 — particularly in the Columbia Basin — temporarily banished the drought. It returned by spring. But except for a narrow strip encompassing the northeastern tip of Umatilla County and small sections of northern Union and Wallowa counties, the drought didn’t reach extreme levels.

The summer was cooler than the past few.

The average high temperature during July at the Eastern Oregon Regional Airport in Pendleton was 90.7 degrees — about 4.5 degrees lower than July 2024, and the coolest for the month since 2020.

At the Baker City Airport, July’s average high of 86 degrees was the coolest since 2016.

Wheat and some other crops in the region are global commodities, subject to a variety of market forces. The incoming Trump administration’s aggressive tariff policies further complicated the situation, although the effects remain uncertain as the year wanes.

Mark Ward, whose family grows wheat, potatoes, peppermint, field corn and alfalfa in Baker County, said in mid-October that he’s “not worried about tariffs.”

Ward said he hopes the Trump administration’s approach will “level the playing field” and potentially open markets for frozen potato

products in Vietnam and the Philippines.

In early July, Vietnam agreed to eliminate its 12% tariff on frozen French fries imported from the U.S.

The relatively mild summer contributed to a “heck of a potato crop,” Ward said.

Other farmers, including Clint Carlson of Ione, have expressed concerns about tariffs exacerbating the already difficult market conditions afflicting wheat growers.

Wheat prices are troubling, to be sure, but Ward said he’s optimistic that the administration’s trade policies will help American farmers.

“We can compete in the world market — we’re pretty efficient,” he said.

AgWest Farm Credit, in an Oct. 8 industry report, noted that “wheat prices remain significantly low, creating a challenging outlook for growers across the West.”

In late September, as the 2025 harvest was concluding, the Oregon Legislature passed a transportation funding package that nearly doubles fees for vehicle license renewals.

Farmers and ranchers say the bill means a nearly immediate boost in their costs, because vehicles licensed for farm use are renewed every year rather than every other year for other vehicles.

As for weather, the National Weather Service predicts that La Nina conditions are likely in Oregon this winter, which typically means weather colder and wetter than usual. That would be a boon for mountain snowpacks, the biggest source of irrigation water for much of the region, and for dryland wheat crops.

BY JAYSON JACOBY | BAKER CITY HERALD

BAKER CITY — Dean Defrees has been raising cattle for several decades, his family has been in the beef business longer still, and he’s never seen a more promising market.

Defrees needs only one word to describe the situation in the fall of 2025.

“Unprecedented.”

Another Baker County rancher, Curtis Martin, also settles on a singular description for wholesale beef prices.

“Stratosphere.”

“It’s just crazy,” Martin, a past president of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association, said on Oct. 15.

There is no lack of consensus in the industry that the past few years have been good ones, generally, for ranchers, with strong prices in the wholesale market.

And those prices continue to rise.

AgWest Farm Credit, in its quarterly market survey released in late September, reported that western steer calf prices had jumped by more than 40% compared to 2024. That defies the typical autumn trend of declining prices.

Defrees, whose family’s ranch is in the Sumpter Valley, about 25 miles west of Baker City, said such a sustained run of bountiful prices is outside his previous experience.

“If you’re still in the business, it’s been pretty good,” Defrees said on Oct. 13.

Quite a few ranchers aren’t still in the business, though — and their departure has played a major role in the beneficent market trends of the past few years.

The nation’s beef cattle herd has dropped to its lowest level since the 1950s, according to analysts.

Yet Americans continue to covet beef, even though chicken has supplanted beef as the nation’s most popular source of protein.

Basic economic principles prevail — strong demand combined with a declining supply boosts prices.

So long as the current situation continues, beef producers are likely to enjoy profitable prices, said Mark Bennett, who has a ranch in southern Baker County.

How long the market will maintain its record-setting momentum is uncertain.

AgWest Farm Credit projects conditions will “support profitability through 2026.”

Defrees said he’s read forecasts suggesting the national cattle herd won’t start to grow until 2028.

“I don’t see the American cow herd being built back up in the next year, and maybe longer than that,” Martin said. “The demand for cattle has never been greater than it is now,” Martin said.

The temptation to take advantage of current prices, rather than keeping heifers to grow a herd, is powerful, he said.

As for demand, AgWest Farm Credit notes something that Bennett, Defrees and other ranchers in the region also recognize — beef prices in the grocery store have also risen.

“I feel for people who are trying to buy protein,” Defrees said. “It does make it tough on the consumer buying beef.”

AgWest Farm Credit addresses the issue in its quarterly report: “The key question is whether these higher prices

will finally curb domestic beef demand.”

For now, though, ranchers in Baker County, where beef cattle is the biggest part of the county’s largest economic sector, agriculture, have ample reason to be optimistic.

“Packers are fighting over the fat cattle, and the market is good — an all-time high,” said Mike Widman, who has been raising cattle in Baker County for half a century.

Martin said he recently sold a 735-pound steer for $3.75 per pound, and a 615-pound heifer for $3.85 — prices that would have seemed fantastical five years ago.

“It’s just crazy,” he said.

There is no lack of consensus in the industry that the past few years have been good ones, generally, for ranchers, with strong prices in the wholesale market.

Martin said meat packers are also taking much heavier carcasses than in the past, up to 1,100 to 1,300 pounds.

Fifteen or so years ago, he said, packers would have deducted the price they paid for such large carcasses. But that’s not the case now, Martin said.

The financial picture isn’t the only bright one, either.

The summer of 2025 was dramatically different from the previous year in one significant respect — wildfires.

There were few blazes in 2025, and none close to the scale of the 293,000-acre Durkee Fire in 2024, Oregon’s biggest of the year.

Parts of the county were in moderate drought for much of the summer, but periodic rain prevented the drought from worsening, as happened from 2020-22.

Bennett said grass on his ranch stayed green through the summer.

“It’s remarkable that we didn’t dry up on nonirrigated ground,” he said.

Widman, though, said a lack of rain resulted in a relatively poor grass crop on his rangeland in the Little Lookout Mountain area east of Baker City.

But he said his cattle found enough to eat.

“The cows came home in decent shape,” he said. “The calves look OK.”

This summer was milder than the past few.

The temperature never reached 100 degrees at the Baker City Airport during 2025.

A year earlier, though, the airport set a record with 12 days of triple-digit temperatures.

In the midst of the record-setting high cattle prices, the Trump administration has pursued an aggressive trade policy dominated by tariff increases.

Widman said that as of mid October, almost nine months into Trump’s second stint as president, he has yet to see any effects, whether helpful or harmful, that he can definitely attribute to tariffs.

Defrees said “anything made out of steel is more expensive, it seems to me,” but he said he can’t attribute those costs directly, or indirectly, to tariffs.

Bennett, however, said he made one purchase this year — in late summer for parts for an all-terrain vehicle made in Canada — that were more expensive due to tariffs.

Bennett said the bill, from a Canadian supplier, listed a $200 charge, about double the cost of the parts, for tariffs.

“That invoice was such a surprise,” he said.

U.S. tariffs might be helping American ranchers in certain ways.

AgWest Farm Credit noted that on Aug. 1, the U.S. imposed a 50% tariff on imports of beef from Brazil, a change that could cut those imports by 70%.

“As a major supplier of lower-end beef cuts, Brazil’s reduced presence in the market has forced U.S. processors to source beef from higher-cost suppliers,” AgWest Farm Credit reported. “Coupled with the ongoing reduction in feeder cattle imports from Mexico, the market for both feeder cattle and finished beef products is likely to remain constrained. This tightening supply is expected to drive up both U.S. cattle and beef

prices.”

The reduction in feeder cattle imported from Mexico stems from the spread of New World screwworm disease in Mexico. The disease, which has not been reported in U.S. cattle, has blocked the import of about 100,000 head of feeder cattle from Mexico per month, AgWest Farm Credit reported.

Martin said the drop in Mexican beef imports has had a “quite substantial” benefit for American ranchers, helping push prices to their current record levels.

Martin said tariffs have been “dramatically negative” for some farmers who grow crops, such as wheat and corn, that are exported.

This has actually helped cattle ranchers, he said, because prices for feed have dropped.

Martin said he takes no solace in that trend, however, as he would prefer that the agriculture industry as a whole, both farming and ranching, would prosper.

Although the effects of tariffs aren’t always obvious, another government action, this one at the state rather than federal level, will boost costs for farmers and ranchers almost immediately.

In late September the Oregon Legislature passed a bill that raises a variety of fees to increase the budget for highway and street projects.

The package includes a 6-cents-per-gallon increase in gasoline taxes, but that doesn’t apply to off-road diesel that farmers and ranchers rely on.

But the bill also nearly doubles the renewal fees for vehicle registrations starting in 2026.

That’s a greater expense for farmers and ranchers because vehicles registered for farm use have their licenses renewed every year, rather than every other year as with non-farm vehicles.

“It hits us a little harder,” Bennett said.

“That adds up,” Widman said.

He said the renewal fee hike will cost him a couple thousand dollars annually.

With prices also rising for fertilizer and other necessities, Widman said he’s fortunate that cattle prices are high.

Defrees agreed.

“It would be brutal if the market wasn’t so good,” he said.

Martin said the new state vehicle fees “take some of the bloom off” the rosy scenario in the beef market.

with a gently distressed sense of charm, this sectional invites you to drift away in high style. Rest assured, the sectional’s leather alternative upholstery offers a warm, cozy feel, while clean-lined styling and jumbo stitching deliver the cool, contemporary look you love. Factor in power reclining motion, USB charging, convenient cup holders, and a drop-down table, and you’ve got all the makings for the best seats in the house.

BY ISABELLA CROWLEY | THE OBSERVER

UNION COUNTY — When it comes to drones and agriculture, the sky is the limit.

Teens from Union, Wallowa and Baker counties had the opportunity to learn about how drones and other technologies are utilized in agriculture on Oct. 15 during the inaugural Trades Talk and Career Walk.

Andrew “Drew” Leggett with Blue Mountain Community College was at the career fair with the Mobile Precision Agriculture Laboratory, while Pendleton-based Advanced Drone LLC showcased its sprayer drones.

“Ag has always been an early adopter of technology,” Leggett said.

The trade career fair was spearheaded by Union County Commissioner Jake Seavert.

Around 200 juniors and seniors attended the fair, according to Seavert, with students from Cove, Elgin,

Enterprise, Imbler, Joseph, La Grande, North Powder, Pine Eagle, Union and Wallowa.

“I wanted to offer it to every junior and senior in the county,” he said.

The two agricultural drone booths were just a fraction of the total 25 vendors at the Trades Talk and Career Walk, but both were popular spots with students throughout the event.

Drones have a wide application of uses in agriculture, Leggett said, from spraying herbicides or insecticides to inspecting crop health or assessing damage after a storm.

Spraying drones are one of the biggest uses in Eastern Oregon, Leggett said, and many businesses that specialize in this technology have a hard time keeping up with the demand.

Caleb Bentley, who works at Advanced Drone Ag and

was one of the employees speaking with students at the career fair, explained that spraying drones are versatile. They can spray herbicides or pesticides and be used to spread fertilizer or seeds.

Drones can be used on either small or large acreage, Bentley said, and can be a good choice for spraying places you can’t access with a plane or helicopter.

Other tasks are done with the help of cameras embedded in the drones, Leggett said. There are camera lenses that can reveal problems that the human eye can’t always detect.

For example, he said, when plants are stressed they start turning more yellow or brown. There are lenses that can show that change in color before it can be seen with the human eye. This early detection can help farmers address the issues faster.

Drones can be used on either small or large acreage, and can be a good choice for spraying places you can’t access with a plane or helicopter.

— Caleb Bentley, Advanced Drone Ag

Another use for drones is mapping fields after storms, Leggett said, to more accurately document damages for insurance purposes.

“The sky’s the limit,” Leggett said.

Engaging the next generation

Career fairs like the one put on in Union County help expose students to these programs and possible job opportunities.

BMCC offers two drone programs, Leggett said — the precision ag program and the unmanned aerial systems program. He advises students interested in drones to pick the program that aligns with what industry they want to work in.

Precision ag is more for students interested in agriculture, data collection and analysis, while he recommends the UAS program for students who are more interested in the drones themselves.

Leggett provides information about the programs at schools, clubs and fairs. These presentations are also a good opportunity for hands-on experience with drones.

Many kids pick up flying the drones very quickly, he said, in part because the controls are similar to video games.

Bentley said that career fairs help get the word out to students that this is an option. He thinks the field will continue to grow.

“I see it progressing a lot,” he said.

Valves: Butterfly, ball, gate, check Automatic control valves: Nelson, Netafim

“Proudly serving and investing in the future of our communities”

Eastern Oregon University’s new degree program is the nexus of business, agriscience and leadership to innovate the future of agriculture!

eou.edu/agrient

At Umatilla Electric, we’re shaped by the people we serve. As a community-owned utility, we are driven to be more than a business, we are an energy partner.

Learn more about how UEC is helping to power communities at:

BY JUSTIN DAVIS | BLUE MOUNTAIN EAGLE

FOX

— A section of Fox Creek on the McGirr Century Ranch in Fox has undergone a massive overhaul in an effort to provide adequate spawning and rearing habitats for anadromous and resident trout species.

Bud McGirr, owner of the McGirr Ranch, reached out to the Grant Soil and Water Conservation District in 2014 about the effort, which ultimately became the McGirr Diversion and Habitat Project. Project design began in 2016 with work concluding in the summer of 2021.

The project’s scope centered on removing a concrete dam and installing 2,500 yards of material for engineered riffles, the relocation of 100 juniper trees and the

installation of 500 lineal feet of 24-inch diameter highdensity polyethylene pipe. Six tire tanks, a solar pump and 1,100 lineal feet of high-density polyethylene pipe for stock water were also installed at the site.

The project was a collaboration between the Grant Soil and Water Conservation District, Bureau of Reclamation, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs, and Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board.

The project’s design cost $65,000, and construction had a $187,000 price tag. Funding partners on the project were the Bureau of Reclamation, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs and the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board.

The only cost to the landowner was the relocation of the juniper trees.

The project’s main focus was removing a solid concrete dam from the creek that was installed in 1980 by the federal Soil Conservation Service, the predecessor to the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Water levels could be adjusted by the landowner as needed by adding or removing boards. In a lot of cases, those boards are simply left in place, creating changes in water elevation that smaller fish can’t navigate.

Kyle Sullivan, the Grant Soil and Water Conservation district manager, said the section of Fox Creek is habitat for steelhead.

“So that’s an issue,” he said. “The adults I think can make it. Smaller fish, we designed for six inches and I think they can clear maybe a foot and a half to two feet.”

Sullivan said conditions in that reach of Fox Creek made it unlikely that smaller fish could make it upstream to access habitats they’d need to get away from predators and grow into adult steelhead.

After the removal of the dam, engineered riffles were installed to gradually reduce the creek’s grade instead of having the large drop-off the dam provided at times. Another goal was to activate oxbows around the creek in order to reduce some of the water’s erosive strength and capture sediment.

An existing eroding bank was pulled back to prevent bank erosion and assist in the recovery of plants. Large wood and ballast rock were installed along the bank to limit further erosion.

Changes to the landscape of the 1,500 linear feet of stream comprising the project were apparent in the first few months after completion. Oxbows surrounding the creek quickly filled with water and vegetation has filled in around those oxbows.

fish screen at the site to prevent fish from getting out of the creek.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Fish Passage Screening Program also installed a fish screen at the site to prevent fish from getting out of the creek.

The Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs got involved as well, planting native vegetation along Fox Creek and erecting cattle fences around the plants for protection. More large wood was added to the site to provide more complexity to the creek while providing more habitat for both larger and smaller fish.

Vegetation planted by the tribes is also thriving. Gone is the large concrete dam that dominated that portion of the creek, replaced by a headgate that can simply be opened or closed.

Cole Winegar, the Grant Soil and Water Conservation District engineer, said the district has done over 150 dam removals in Grant County since the 1990s.

“This was a little more complex,” he said of the Fox Creek project.

Winegar said the project’s success was due to meeting the goals of all parties involved.

“We’re trying to meet landowner and funder goals,” he said. “The landowner wants his authorized water rights without much dam maintenance, funders want fish habitats and passages protected.”

BY BERIT THORSON | EAST OREGONIAN

ATHENA — Stories can be told in images just as much as words: a sunset silhouetting a pea harvest, a wheat air drill seeding a hill, and a soil probe pulling core samples from the ground all depict different parts of life for an Eastern Oregon farmer.

Dan Wilcox, the documentary photographer behind such images, is working to highlight high desert agriculture by following one farm’s business for a year to tell its story. He started the project in early 2025 and plans to show the changes in how farming looks throughout the year.

“I grew up on a farm on the coast and it’s so different from over here,” he said. “Farming’s a gamble every year, but people do it because they love doing it.”

Dan Wilcox/Contributed Photo

Wilcox said he’s had some of his childhood experiences and beliefs about farming confirmed, while others have shifted, since modern-day farming of thousands of acres requires such a different approach and, he said, much bigger and more expensive equipment.

Just like on the coast, though, the people he’s documenting at W4 Farming in Athena are hardworking and innovative, with a focus on land stewardship. They’re doing it because they love it, he said, and he believes they “don’t get the respect that they deserve” for the work they do growing food for people.

“I’ve heard some really dumb statements by people that have never been on a farm,” Wilcox said. “They have no clue how much work goes into this, and I think opening their eyes to what goes into farming (is a goal of mine).”

Originally, Wilcox was going to take a few photos and give them to Chris Williams, owner of W4 Farming. Then the project morphed into something bigger, with Wilcox

documenting the planting and harvesting of wheat and peas, as well as the daily challenges of farming, including equipment breakdowns and the administrative paperwork.

Williams said having Wilcox around for the past nine months or so has been fun.

“We just kind of flow from one season to the other. There’s really no transition,” he said. “So it’s been neat to have that record of all the different activities that we do during the year.”

Williams said Wilcox has noticed parts of their work — and has taken the time “to really capture the essence” of it — that Williams himself takes for granted, as the one who’s used to the ins and outs of farming. Wilcox often spends half of a day or more at the farm, taking photos and asking questions, getting the W4 team to explain to him why they decide to approach something in a certain way, or how something else works.

“I guess as much as anything, it’s just satisfying my curiosity,” Wilcox said. “It’s constantly mentally stimulating.”

Originally, Dan Wilcox was going to take a few photos and give them to the owner of W4 Farming. Then the project morphed into something bigger, with Wilcox documenting the planting and harvesting of wheat and peas, as well as the daily challenges of farming.

For Wilcox, there’s not a clear answer for how to display his work. He’s considering creating a photo book, but he’s also thinking about trying to get his photos shown in a gallery.

His friend and subject, Williams, said he’d like to see the images in public places where people who don’t know about farming can learn.

“Art reminds us of the things that are important to us,” Williams said. “I think having an artist’s perspective of something as important as our food production is really critical to help people remember that it takes a lot of hard work and that there are fun times and there are tough times, but at the end of the day, we’re all really appreciative of what we do.”

The project may take another year to complete, Wilcox said, since he missed some moments the first time around as he and the W4 team were first figuring out the project.

He wants to return to W4 to capture what happens at those times and then wants to finalize the best of his images and find the right home for them.

Wilcox said he hopes the photos end up going into the world to show people “this is what the farmers do so you can have a loaf of bread.”

Owners of

land in Baker,

Malheur

counties, by

maintaining quality sage grouse habitat, can sell credits to developers whose projects would harm sage grouse

BY JAYSON JACOBY | BAKER CITY HERALD

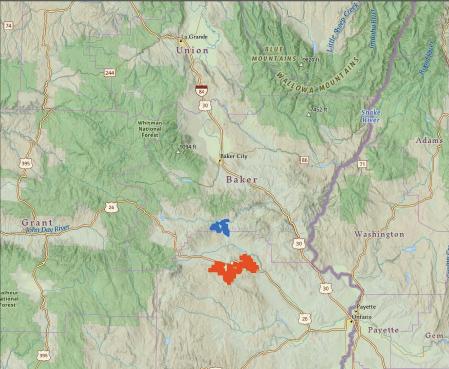

BAKER CITY Developers who want to build solar or wind farms, mine for gold or lithium, or pursue other projects that harm sage grouse habitat have a new option to satisfy Oregon’s requirements to protect the chicken-size bird.

A group of investors have bought about 32,000 acres in northern Malheur County and 8,000 acres in southern Baker County and created the state’s first “conservation bank” specifically for sage grouse.

Doug Hymas of Middleton, Idaho, is one of the investors and represents the group of about 10.

Hymas said they bought the Malheur County property, which is on both sides of Highway 26 in the Cow Valley area east of Ironside, in 2021. They bought the Baker County property, south of Bridgeport, in 2023. Most of the investors in the company, Three Creek LLC, are from Idaho or Utah, Hymas said. None is from Oregon.

The two properties are not connected, being separated by several miles.

Baker and Malheur county property records don’t list a sales price for the parcels.

Both properties have been working cattle ranches

for decades, and they remain so, said Nathan Ayers, chief operations officer for Terra West Consulting, the Wyoming firm that helped set up the Northern Great Basin Conservation Bank for Hymas and the other investors.

The owners have contracted with Sam Martin, a local rancher, to run the cattle operation on the Baker County property.

“He’s a very good friend of ours,” Hymas said.

A different rancher is leasing the Malheur County portion of the conservation bank.

To qualify with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, which administers the program, a property must serve as quality habitat — in this case, for sage grouse, Ayers said.

(The property also has winter range for deer and elk, he said.)

About 90% of the Three Creek LLC land is within core habitat for sage grouse based on ODFW’s maps, Ayers said.

Although much of the property functioned as sage grouse habitat before Hymas and the other investors bought it, Ayers said Terra West, working with the investors, have undertaken multiple projects since the purchase designed to

A group of investors own Oregon’s first conservation bank for sage grouse. The properties, including this land in northern Malheur County, has sagebrush and wildflowers, including the lupine and arrowleaf balsamroot seen here, that are important habitat for the birds. — Contributed Photo

improve habitat for the bird, which has been a candidate for federal protection for more than 20 years but has not been listed under the Endangered Species Act.

The work includes cutting juniper trees, which can crowd out sagebrush and other native plants that sage grouse depend on for food and shelter, Ayers said.

Workers have also:

• Installed colored flags on range fences, which can prevent sage grouse from flying into the wires and being hurt or killed.

• Mapped invasive annual grasses, such as cheatgrass, as well as other noxious weeds and started trying to remove those species, which, like juniper, can stifle native vegetation crucial for sage grouse.

• Building pipes and troughs to prevent cattle from congregating near streams.

• Building structures that mimic beaver dams and can improve habitat along streams.

Based on these improvements, ODFW allows Three Creeks LLC to sell a certain number of credits to developers whose projects would harm sage grouse habitat, said Greg Jackle, ODFW’s sage grouse coordinator.

A male sage grouse inflates air sacs in its breast and fans its tail feathers as part of the bird’s spring mating ritual. The birds gather each year in open areas known as leks. — Nick Myatt/Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, File

Although Three Creeks received a small number of credits based on the property being in relatively good shape at the time of the transaction, Jackle said the majority of the credits available for sale resulted from habitat improvement work the investors have done since the purchase.

If, for instance, a company wants to start a gold mine in sage grouse habitat, ODFW would estimate the harm that would cause to the birds.

The company could then buy credits from Three Creeks LLC to, in effect, offset that harm.

Jackle said ODFW has no role in setting the price for the credits — that’s a private matter between the conservation bank and the developer.

Conservation banks can sell credits only once, Jackle said.

He said Three Creeks LLC has sold credits for one project that harms sage grouse habitat — Idaho Power Company’s and PacifiCorp’s Boardman to Hemingway power transmission line. Construction started this summer in Malheur County on the 293-mile, 500-kilovolt line, which runs between a substation near Boardman, in Morrow County, and Owyhee County, Idaho. The line passes through portions of Malheur, Baker, Union, Umatilla

and Morrow counties in Oregon.

“Idaho Power bought mitigation credits in the Northern Great Basin Conservation Bank as part of our agreement to mitigate impacts of B2H and to fulfill our commitment to the communities we serve and the places we all love,” company spokesperson Sven Berg said. “The conservation bank property includes tens of thousands of acres of highquality, year-round habitat for sage grouse and big game summer and winter habitat in Oregon. The B2H project was instrumental in the conservation bank’s formation, but other organizations can contribute to the bank.”

Three Creeks LLC’s responsibilities don’t end after it has sold credits, Jackle said.

The company must continue to maintain the sage grouse habitat on its land in perpetuity. Jackle said ODFW officials meet annually with the conservation bank representatives to make sure the land remains quality habitat for sage grouse.

How long Three Creeks will have credits to sell is “100 percent dependent” on how much demand there is for those credits, Jackle said.

Saws and Cycles is

to announce that we are open for business under new ownership Teeters Toys! We are committed to continuing to provide the exceptional service and quality products you’ve come to expect.

Some government projects, such as extending a road, can harm sage grouse habitat, an effect that could be offset by buying credits from a conservation bank.

He said Hymas and his fellow investors could potentially gain more credits by buying additional land, so long as the new properties are also adequate sage grouse habitat.

Hymas said the investors naturally wanted to start selling credits as soon as possible, to begin recouping the money they spent first to buy the 40,000 acres, and then to improve the habitat over the past few years.

“As an owner, I’d like to see a large number of credits sold quickly,” he said.

Hymas said that before ODFW approved the conservation bank, developers who harmed sage grouse habitat had two options to meet state requirements — either pay a fee to the state, or try to mitigate the effects on their own property.

“We’re sort of a hybrid,” he said — the developer pays a different property owner who has already taken steps to provide habitat for sage grouse.

Jackle said no developer in Oregon has paid a fee to offset damage to sage grouse habitat, an option that likely would be more expensive than buying credits from a conservation bank.

Hymas said developers can pay for conservation credits over years, rather than a

one-time lump sum.

Although Three Creeks LLC has so far sold credits to a private developer — Idaho Power — Hymas said he and Ayers have also had conversations with state government officials about possibly selling credits.

Some government projects, such as extending a road, can harm sage grouse habitat, an effect that could be offset by buying credits from a conservation bank.

There are restrictions, based on geography, on which developers can buy credits from Three Creeks LLC’s conservation bank.

That’s an option only for developments that, like the conservation bank land, are within ODFW’s Northern Sage Grouse Service Area, one of three such areas in Oregon, Jackle said.

The northern service area includes all sage grouse habitat in southern Union County (the northern extent of the bird’s range in the state), all of Baker County, the eastern part of sage grouse range in Grant County (the far southern part of the county), most of Malheur County and the northeastern section of Harney County.

Although the focus of Three Creeks LLC’s conservation bank is sage grouse, Ayers said the investors could also potentially sell credits to offset effects on deer and elk habitat, since the conservation bank property also includes winter habitat for those animals.

Jackle said Oregon’s second conservation bank, which has not yet been approved, is in the central service area. That area includes all of Crook County and parts of Grant, Deschutes, Lake and Harney counties.

The western sage grouse service area includes the southern halves of Lake and Harney counties.

Martin, who runs his cattle and raises hay on the Baker County property near Bridgeport, said he met Hymas a few years ago after the group of investors bought the Malheur County property.

That part of the conservation bank is near property that Martin’s family has owned for decades.

Martin said that after he learned Hymas’ group had also bought the Baker County parcels, he got in touch with them.

Martin said he raised hay on the land in 2024. In 2025 he also started grazing his cattle on the property.

He praised the work the new owners have done, including cutting juniper and spraying noxious weeds.

“They’re doing a lot of good things that are needed,” Martin said.

The projects benefit cattle as well as sage grouse, he said.

Martin said he has heard that the ranch previously supported 400 to 500 head of cattle. He’s running 250 head on the property.

Martin said he thinks that’s a reasonable herd size. He said he’s seen evidence on the ground that parts of the ranch might have been overgrazed in the past.

Martin said he hopes the new owners’ efforts to improve the property, under the state’s requirements for a conservation bank, will boost the grass growth enough that he can run more cattle.

Martin considers the conservation bank project a good example of how cattle and sage grouse can co-exist.

“They can do very well together,” he said.

BY BILL BRADSHAW | WALLOWA COUNTY CHIEFTAIN

ENTERPRISE — Harvest has wrapped up for another year in Wallowa County and producers are generally pleased with their yields.

Dan Butterfield of Butterfield Farms works ground about four miles east of Joseph. He said he got done early bringing in his crops of hay, wheat and barley.

“Things went really well,” he said on Oct. 14. “We got done before the storm and everything went really well.”

Butterfield said the price of wheat is down, and he’s been told it’s largely because China is not wanting to buy U.S. wheat.

“I haven’t sold it yet. Right now the price isn’t great,” he said. “I’m sure that’s tariff-related.”

A farmer applies chemicals to his field east of Joseph.

Bill Bradshaw/Wallowa County Chieftain

Kevin Melville, one of the owner-operators of Cornerstone Farms Joint Venture, isn’t so sure. Although he agrees wheat prices are down, he thinks it’s more to do with good crops worldwide and overproduction.

“The tariffs have a small effect on it,” Melville said. “The main problem is good production all around the world.”

Melville said one of the major problems producers are facing is input prices — the cost of fertilizer in particular. He said the cost of potash and ammonium sulphate from Canada has been high, which always hits American farmers hard.

“Low prices are common,” he said. “But when there’s low prices, the big problem is overproduction.”

Still, he said, he doesn’t believe President Donald

Trump’s tariffs are having a major effect on the wholesale price of grain.

Cornerstone, which is one of the larger farms in Wallowa County, grows a wide variety of crops, including wheat, hay, barley, peas, canola and lentils. The canola oil can be interchanged with soy oil, Melville said, which puts it in competition with China’s soy crops.

He said the amount of water crops received made a big difference.

“The irrigated ground went really well; we were really happy with the yields,” he said. “But the dryland wasn’t too good. That’s what happens when it doesn’t rain. It was a very dry year.”

He said April, May and June — the months farmers count on for precipitation — were relatively dry.

“All of the crops were bad on the dryland,” he said. “On irrigated ground, all the yields were strong as long as you were doing a good job of irrigating.”

Hay prices, too, are down, Melville and Butterfield agreed, although the prices are comparable with last year.

“I don’t think anybody’s excited about hay prices,” Melville said.

Butterfield attributed the poor hay prices to oversupply, although he said prices are “still reasonable.”

But, he said, it’s unlikely export hay has been affected by the president’s tariffs and it had slowed down before the tariffs.

“It seems like the export market overseas has slowed way down,” he said.

Beef prices a bright spot

Butterfield, who also raises beef cattle, said wholesale beef prices are quite high — higher than he’s ever seen.

“Right now they’re higher than they’ve ever been,” he said. “I’ve got to get around to selling something and not miss the market.”

Melville, who doesn’t sell beef, said he’s heard of the high prices from cattle producers.

He said he’s heard they’re “through the roof. Everybody I’ve talked to says they’re high.”

Theresa Stangel, of Stangel Buffalo Ranch, said the bison they sell don’t directly compete with beef cattle and the bison industry is smaller than the beef industry.

“The prices are good,” she said. “We’re not as dependent on the national average, so we’re able to set prices based on what we need rather than the competition.”

She said Stangel’s bison, whether by the pound or on the hoof, isn’t influenced as much by the cattle industry.

“Ours is pretty low compared to what you find online,” she said.

Stangel’s production is primarily its bison, which are 100% grass-fed and finished. The ranch does raise some hay and although most is to feed the bison, some is sold. She said they haven’t had to purchase feed hay in recent years.

For now, farmers are just glad another year is done and they’re looking toward next year.

Melville and Butterfield agreed they now have enough water for the seed that’s been planted.

“We’re optimistic wheat prices will turn around,” Butterfield said. “It’s another year gone.”

Melville agreed.

“I’m just glad we’re done and the wheat’s in the ground for next year,” he said.

Locally