Fort Clatsop was one of the earliest American structures on the West Coast. It was built by the Lewis and Clark expedition to shelter them during the winter of 1805-06, and named for the Clatsop Indians who lived in the area.

The Tuality District was created in 1843 by the Provisional Legislature as one of the four original counties in Oregon. In 1844 Clatsop County was created from the western half of the Tuality District, bordered on the north by the Columbia River. Clatsop County was named for the Clatsop Tribe, one of the many Chinook tribes living in Oregon.

Astoria, Oregon’s oldest city, was founded in 1811 and was chosen by electors to be the county seat in 1854. In 1855 a two-story frame courthouse was completed. The first county government sat in Astoria in 1856. The second courthouse, at 749 Commercial Street was completewd in 1908 and is still in use. County offices are now located in administration buildings near the courthouse at 800 Exchange Street.

In 1964 the county court was replaced by a board of commissioners. The voters of Clatsop County approved a home rule charter in 1988, which called for a board of county commissioners as the policy determining body of the county, and a county manager. County commissioners are elected to geographic districts to four-year terms. Current commissioners are: Chair Mark Kujala, Pamela Wev, Lianne Thompson, Courtney Bangs and John Toyooka.

The Board of Commissioners holds regular meetings on the second and fourth Wednesdays of the month at 6 p.m. The Board holds hybrid meetings via Zoom link and in person, in the Judge Guy Boyington Building located at 857 Commercial St. in downtown Astoria. The public is always welcome to attend the Board meetings. The Zoom link may be found on the county website at: co.clatsop.or.us/boc

Population: 41,695

Housing Units: 23,415

Households: 16,649

Established: June 22, 1844

Elevation at Astoria: 19 feet

Area: 1,085 sq. mi.

County

Astoria

800 Exchange St., Astoria

www.clatsopcounty.gov

Administration Board of Commissioners

County Manager

Clatsop County Court

Code of Ordinances, Records Requests

Animal Control & Shelter

Pet Licenses, Animal Adoption

1315 S.E. 19th Street, Warrenton, OR 97146

Phone: 503-861-0737

Assessment & Taxation

Property Tax information, maps

Phone: 503-325-8522

Clerk & Elections

Register to vote, passports, marriage license

Phone: 503-325-8511

Community Development

Building Codes and Permits, building inspections, Land Use Planning

Phone: 503-325-8611

District Attorney

Phone: 503-325-8581

Emergency Management

Clatsop Alerts – Sign up for text alerts at: www.clatsopcounty.gov/em/page/clatsopalerts

Phone: 503-325-8645

Extension Service

2001 Marine Drive, Room 210, Astoria, OR 97103

Phone: 503-325-8573

4-H, Master Gardeners

Fair & Expo Center

Fair, RV Park, Facility Rentals

92937 Walluski Loop,Astoria, OR 97103

Phone: 503-325-4600

Fisheries

2001 Marine Dr #253, Astoria, OR 97103

Phone: 503-325-6452

Juvenile Department

Phone: 503-325-8601

Parks

Park sites, Clatsop County Park permits, Area Trail Maps

2001 Marine Drive, Room 253, Astoria, OR 97103

Phone: 503-325-6452

Public Health

COVID Resources, Vital Records, Emergency Preparedness, Clinic Services, WIC, Environmental Health, septic systems, household, food safety, food handlers card

Phone: 503-325-8500

Public Works

Road permits, County roads, County Engineer, County Surveyor

1100 Olney Ave., Astoria, OR 97103 • Phone: 503-338-3689

Sheriff & Jail

Concealed weapons permits, Real property sales, Search and Rescue, Medical Examiner, Jail/Jail Roster, Community Corrections, Victims Services

1190 SE 19th, Warrenton, OR 97146 • 503-325-8635

Clatsop Behavioral Healthcare

503-325-5722

Clatsop Behavioral Health 24-Hour Crisis Line

503-325-5724

Clatsop Community Action 503-325-1400

CCA Regional Food Bank 503-861-3663

Clatsop County Dept of Public Health 503-325-8500

Clatsop County Veterans Services 971-308-1045

Coastal Family Health Center 503-325-8315

Community Action Team

Phone: 503-397-3511, Fax: 503-397-3290, TTY: #711

Department of Motor Vehicles (Astoria) 503-325-3951

Department of Veterans Affairs 800-828-8801

Military Helpline 888-457-4838

NW Oregon Housing Authority (NOHA) 503-861-0119

Northwest Senior & Disability Services 503-861-4200

Oregon DHS—Child Welfare 503-325-9179

Oregon DHS—Self-Sufficiency Program 503-325-2021

Oregon DHS—Vocational Rehab 503-325-7335

WorkSource Oregon 503-378-8060

Social Security Administration 800-772-1213

Sunset Empire Transportation “The Bus” 503-861-7433

The Harbor — Domestic & sexual assault support 503-325-3426

The Harbor 24-Hour Crisis Line 503-325-5735

The geography of Clatsop County varies from the Pacific Ocean beaches on the western edge, to the south shore of the Columbia River to the north, and the Coast Range forests in the interior. There are ocean breezes, river fogs and mountain elevations that create microclimates within the county, but overall the weather in Clatsop County is mild, with wet winters that rarely see temperatures below freezing, and summers in the 60 to 70 degree range. Inland, summer temperatures are higher, and winter temperatures lower.

HIGH: 49°

37°

DAYS: 18

51°

37°

DAYS: 16

54°

39°

DAYS: 17

56°

41°

DAYS: 14

HIGH: 61°

46° RAINY DAYS: 10 HIGH: 65°

50° RAINY DAYS: 8 HIGH: 68°

69°

53°

DAYS: 3

53°

DAYS: 3 HIGH: 68°

50°

DAYS: 7

61°

45°

DAYS: 12

54°

40°

DAYS: 18

49°

DAYS: 18

Twice a day the Lower Columbia experiences high and low tides with the gravitational pull of the moon. High tides will cover beaches, rocks and shores exposed just hours earlier, and has stranded the unwary. Low tides can ground boats on sandbars as water recedes. Pick up a tide book at local tourist retailers, check the tide schedule online, or download a tide app and plan your water recreation accordingly.

Seaside Wellness Center

Mental Health Therapy Children, Adolescents, Adults

Julia Weinberg PhD LPC julia@seasidewellnesscenter.net 503-717-5284

2609 Highway 101 N Suite 203 Seaside, OR 97138 http://seasidewellnesscenter.net

Walter E. Nelson Company, formerly known as Astoria Janitor & Paper Supply, has been a locally-owned company since 1952, serving the community with wholesale janitor and paint supplies at

The name was changed to Walter E. Nelson in 2007, with the acquisition of Vern Cook Supply of Seaside. Come see for yourself and experience the customer service and quality that has been a tradition for over 70 years!

Open to the public as well as businesses!

Fisherpoets Gathering

Feb. 27 to March 1, 2026

A celebration of the commercial fishing industry in poetry, prose and song, the FisherPoets Gathering has attracted fisherpoets and their many fans to Astoria since 1998. Held at multiple venues. fisherpoets.org

April 24-26, 2026

The annual Astoria-Warrenton Crab, Seafood & Wine Festival is held in Astoria where food enthusiasts can enjoy great coastal cuisine, arts and crafts, wine tasting and more. astoriacrabfest.com

Mother's Day to Mid-October

In the heart of Astoria’s Downtown. Fresh produce, local arts & crafts, food, music and more in a lively downtown street market atmosphere. Every Sunday from 10 - 3. astoriasundaymarket.com

June 20, 2026

Dozens of teams of professional sand sculpture artists, amateur groups and families construct remarkable creations in the sand during the Sandcastle Contest, which is the oldest competition of its kind in the Pacific Northwest. /www.cannonbeach.org/eventsand-festivals/sandcastle-contest

June 2026

In 2016, the LCQC held the first annual Astoria Pride. Since that time, Astoria Pride has grown into an advocacy, awareness, and community event. www.astoriaoregonpride.org

June 20 & 21, 2026

The festival embodies the rich cultural heritage that was transplanted to the region by emigrating Scandinavians. Music, dance, theater groups, retail booths offer handcrafts, Scandinavian import items and traditional foods. astoriascanfest.com

June 2026

Held annually at the Seaside Civic & Convention Center. The two-day event narrows the competition down to ten finalists before selecting a winner. Evening wear competition, talent competition, bathing suit competition and a competition in casual wear. seasideconvention.com

August 2026

Amusement rides, competitions, pounds of fried food and live music. Held at the Clatsop County Fair & Expo, 92937 Walluski Loop in Astoria. www.co.clatsop.or.us/fair

Regatta is a celebration of the Northwest’s maritime history and future. Held since 1894, the Astoria Regatta is represented by a distinguished court of young women from local area high schools. astoriaregatta.com

August 28-29, 2026

A 199 mile relay event. Every year over 12,000 people race from the base of Mt. Hood to the beaches at Seaside through the picturesque landscape. Decorated team vans, costumes and beach party fireworks, the relay is a unique and unforgettable experience.

hoodtocoast.com

Experience the glory of the Columbia River as you trek across the Astoria-Megler Bridge during this unique opportunity to walk/run across the bridge. From walkers to experienced runners, the 10K appeals to everyone.

www.oldoregon.com/the-greatcolumbia-crossing-10k

One of Cannon Beach’s most popular events. Enjoy a variety of gatherings, artist demonstrations, paint classes, and catch free live musical performances at outdoor venues throughout the town.

www.cannonbeach.org/eventsand-festivals/arts-events/stormyweather-arts-festival

Although Clatsop County’s economy was historically driven by fisheries and forestry, diversification of business in the county has resulted in a shift to manufacturing, tourism and healthcare-centered employment. Fishing and logging businesses still make up a large portion of the owner-operated independent businesses and feed the processing and manufacturing of for those natural resources in Clatsop County. Hospitality-related employment in lodging and food service makes up nearly one-third of the county’s employment.

• U.S. Coast Guard

• Georgia Pacific-Wauna Mill

• Warrenton Fiber Company

• Columbia Memorial Hospital

• Providence Seaside Hospital

• Astoria School District

• Seaside School District

• Clatsop County Government

• State of Oregon

• Tongue Point Job Corps

Astoria-Warrenton Chamber of Commerce 111 W. Marine Drive, Astoria, OR 97103 503-325-6311 oldoregon.com

Seaside Chamber of Commerce 7 N. Roosevelt Dr., Seaside, OR 97138 503-738-6391 Seasidechamber.com

Cannon Beach Chamber of Commerce 207 N Spruce, Cannon Beach OR 97110 503-436-2623

Warrenton Business Association 225 S. Main Ave., Warrenton, OR 97146

Astoria Downtown Historic District Association 609 Bond St., Astoria, OR 97103 503-791-7940 Astoriadowntown.com

Seaside Downtown Development Association 615 Broadway, Suite 213, Seaside, OR 97138 503-717-1914 facebook.com/seasidedowntown

Clatsop Economic Development Resources (CEDR) Small Business Development Center 1455 N. Roosevelt, Seaside OR 97138 503-338-2402 www.clatsopbusiness.com CEDR@clatsopcc.edu

Clatsop County Community Development Department 800 Exchange St., Suite 100, Astoria, OR 97103 Phone: 503-325-8611 Fax: 503-338-3666

Port of Astoria 10 Pier One Bldg., Suite 100, Astoria 97103 503-741-3300 www.portofastoria.com

Northwest Natural www.nwnatural.com

Customer Service: 800-422-4012 Natural Gas Odor? 800-882-3377 Electric Pacific Power

24 hour Residential Customer Service 1-888-221-7070

Recology Western Oregon www.recology.com/recology-westernoregon/ 2320 SE 12th Place Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-0578

Astoria Transfer Station (recycling and dump) 1790 Williamsport Rd Astoria, OR 97103 503-861-0578

Century Link Centurylink.com 866-963-6665

Spectrum www.spectrum.net 833-267-6094 • 866-874-2389 1546 SE Ensign Lane, Suite B Warrenton, OR 97146

Wireless

Verizon Wireless 1490 SE Discovery Lane Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-8553

T-Mobile 1546 SE Ensign Lane Warrenton, OR 97146 503-994-3201

AT&T www.att.com/stores/oregon 159 South, US-101, Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-2100 Water/Sewer

The Astorian DailyAstorian.com

949 Exchange St., Astoria, OR 97103 503-325-3211

news@dailyastorian.com

Seaside Signal

SeasideSignal.com 949 Exchange St., Astoria, OR 97103 503-325-3211

Cannon Beach Gazette CannonBeachGazette.com

1906 Second Street, Tillamook, OR 97141 503-842-7535

Hipfish Monthly

1017 Marine Drive, Astoria, OR 97103 503-338-4878 hipfish@charter.net

Radio

Ohana Media Group ohanamediagroup.com

KAST 1370 AM, KLMY 99.7 FM, KCRX 102.3 FM 285 S.W. Main Court, Suite 200, Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-6620

Coast Community Radio kmun.org

KMUN 91.9 FM/KCPB 90.9 FM/KTCB 89.5 FM 1445 Exchange St., Astoria, OR 97103 503-325-0010

Hits 94.3 KRKZ www.943krkz.com 927 Marine Drive, Astoria, OR 97103 503-468-0943 or 360-636-0110

KBGE The Bridge

KBGE 94.9 FM 615 Broadway #222, Seaside, OR 97138 503-738-866 www.949thebridge.com

Jacobs Radio

99.3 KEUB The Rock

3095 US 101 N. #D-44, Seaside, OR 97138 503-739-7625 https://933therockfm.com

Digital

The Astorian DailyAstorian.com

Seaside Signal SeasideSignal.com

Clatsop News clatsopnews.com 503-338-0818

The bridge was a joint project of the Oregon and Washington state highway departments. Construction began in 1962 and was completed in 1966. It operated as a toll bridge until 1993. At 4.1 miles long, this span over the Columbia River is the nation’s largest continuous truss bridge.

Carries: 2 lanes of US 101 and bicycles

Crosses: Columbia River

Design: Cantilever through-truss

Material: Steel

Total length: 4.067 miles (6.55 km)

Width: 28 feet (8.5 m)

Longest span: 1,233 feet (376 m)

No. of spans: 8 (main) 33 (approach)

Piers in water: 171

Clearance below: 196 feet (60 m) at high tide

Designer: Oregon and Washington transportation departments

Construction start: November 5, 1962

Construction end: August 27, 1966

Construction cost: $24 million ( $147 million today)

Opened: July 29, 1966

Inaugurated: August 27, 1966

Replaces: Astoria–Megler Ferry

Daily traffic: 7100

Toll: None (since December 1993)

• Electrical Solutions for Business & Home

• Services, Power, Lighting, Network, Fire, Security, Cabling & Testing 62 years of investment in our community

Our company was founded in 1910 as Morrison Electric, by Irwin Morrison, scion of a Clatsop County pioneer family. In 1962, DH & Norma Wadsworth purchased & renamed it Wadsworth Electric. Operations were assumed by Rod Gramson & Cheryl Wadsworth Capellen in 1975. In 2009, Cass Liljenwall became the manager & supervising electrician. Our crew of electricians is top notch! Jack, Charlie, Todd, Bill, Tyler, Tucker & Nick – thank you so much. Sincere thanks to our customers, past, present & future.

Clatsop County Sheriff’s Office

1190 SE 19th, Warrenton • 503-325-8635 www.clatsopcounty.gov/sheriff

Clatsop County Jail

503-325-8641

Clatsop County Emergency Management

Office Address: 91372 Rilea Pacific Road, Bldg. 7315, Warrenton, OR 97146-7269 www.clatsopcounty.gov/em

Clatsop County Animal Control

1315 19th, Warrenton • 503-861-0787 www.clatsopcounty.gov/animalcontrol

Oregon State Police

2320 SE Dolphin, Warrenton 503-861-0781 www.oregon.gov/osp/Pages/officelist.aspx

Astoria Fire Department

555 30th St, Astoria • 503-325-2345 astoria.gov/dept/Fire_Department

Astoria Police Department

555 30th St, Astoria • 503-325-4411 astoria.gov/dept/Police_Department

Warrenton Fire Department

225 S Main, Warrenton • 503-861-2494 ci.warrenton.or.us/fire

Warrenton Police Department

225 S Main, Warrenton • 503-861-2235 ci.warrenton.or.us/police

Seaside Police Department

1091 S Holladay, Seaside • 503-738-6311 www.cityofseaside.us/police-department

Seaside Fire and Rescue

150 S Lincoln, Seaside • 503-738-5420 http://www.seasidefire.com/

of

Gearhart Police Department

698 Pacific, Gearhart • 503-738-5501 cityofgearhart.com/general/page/policedepartment

Gearhart Volunteer Fire Department

670 Pacific, Gearhart • 503-738-7838 gearhartfire.com/

Cannon Beach Police Department

163 E Gower, Cannon Beach

503-436-2811

ci.cannon-beach.or.us/police

Volunteer Fire Departments

Cannon Beach Rural Fire Protection District

503-436-2949

Elsie-Vinemaple

Rural Fire Protection District

503-755-2233

Hamlet Fire Department

503-440-5064

Knappa-Svensen-Burnside and John Day-Fernhill

Rural Fire Protection Districts 503-458-6610

Lewis and Clark

Rural Fire Protection District 503-325-4192

Westport Oregon Fire & Rescue 503-455-0727

Olney-Walluski Fire and Rescue

503-325-5440

Mist-Birkenfeld

Rural Fire Protection District

503-755-2710

American Red Cross 3131 N Vancouver Ave. Portland, Oregon 97227

503-284-1234

Provides CPR & First Aid training. Fee apply, scholarships available. redcross.org

Seaside/Gearhart emergency warning system monthly tests From September to May, every first Wednesday the Seaside Police Department tests the emergency warning system: three beeps followed by a voice warning.

Tsunami evacuation maps www.clatsopcounty.gov/em/ page/tsunami

Clatsop County’s emergency notification system to local citizens, providing warnings about storms, floods and tsunamis, road closures and other urgent information by voice or text messages to home phones, cell phones and email. To add cell or email contacts to ClatsopALERTS! sign up at: www.clatsopcounty. gov/em/page/clatsopalerts

Astoria Astor Apts./Mod Rehab Prog. 1423 Commercial St 503-325-5678

Astoria Astoria Gateway Apts. 2775 Steam Whistle Way 503-325-2882 62+

Astoria Astoria Gateway Apts. II 2850 Marine Dr 503-325-4184

Astoria Bayshore Apartments 1400 W Marine Dr 503-325-1749

Astoria Bayview Cottages 783 W Marine Dr 503-325-3323

Astoria Cavalier Court Apts. 91817 Hwy 202 503-468-8753

Astoria Community Property Mgmt. 175 14th St 503-325-5678

Astoria Elmore Apartments 687 14th St 503-850-8895

Astoria Emerald Heights 1 Emerald Dr 503-325-8221

Astoria Hilltop Apts. (CCA) 364 9th St 503-325-1400

Astoria KD Properties 200 Nehalem Ave 503-325-3323

Astoria Lyche Properties 1245 W. Marine Dr. 503-720-4178

Astoria Meriwether Village 101 Madison 503-325-3072 •

Astoria Merwyn Apartments 1067 Duane St.

Astoria Port Town Property Management 109 9th st 503-741-3145

Astoria Owens-Adair Apartments 1508 Exchange St 503-861-0119 •

Cannon Beach Elk Creek Terrace 357 Elk Creek Rd 503-436-9562

Cannon Beach Shorewood Estates 1121 Spruce Ct 503-436-9709

Hammond Columbia Pointe Apts 500 Pacific Dr 503-791-3703

Hammond Parkview Commons Apts 421 NW Ridge Rd 503-861-6031

Gearhart CPS Management 3643 3642 Hwy 101 N 503-738-5488

Seaside Beach Property Mgmt 800 N Roosevelt unit 20 503-738-9068

Seaside Clatsop Shores 2561 N Roosevelt Dr 503-861-0119 x113

Seaside Creekside Village Apts. 1953 Spruce Dr 503-738-6880

Seaside Hudson’s Point Apts. 1021 S Downing 503-738-9482

Seaside Lyche Properties 2149 S. Franklin St. 503-720-4178

Seaside Salmonberry Knoll 1250 S Wahanna Rd 503-717-1120

Seaside Sandhill Apartments 150 S Wahanna Rd 503-738-5475

Seaside River and Sea Property Mgt Multiple sites 503-468-4706

Seaside The Retreat 2160 Lewis & Clark Rd 503-325-5678

Seaside Waterfront Property Management 120 N Roosevelt Dr 503-738-2021

Warrenton Alder Court 235 SW Alder Court 503-861-8590

Warrenton Bayview Apartments 50 NE 1st St 503-861-3721

Warrenton Birch Court Apts. 216 SW 2nd St 503-861-1296

Warrenton Canim Apartments 235 SW Alder Ave. 503-861-8590

Warrenton Sowins Real Estate 280 SE Marlin Ave 503-861-1717

Warrenton Tillikim 1521 SE Willow Dr. 503-861-0119

Warrenton Tillikim 1581 SE Willow Dr. 503-861-0119

Warrenton Trillium 700 SE 14th Place 971-470-5243

Northwest Oregon Housing Authority (NOHA)

Geographical Area Served: Clatsop, Columbia, and Tillamook Counties

147 S Main Ave, Warrenton • 503-861-0119 • Fax 503-861-0220 • www.nwoha.org

• Housing Choice Voucher program Section 8-including Family Self-Sufficiency and Home Ownership programs

• Affordable housing units in Warrenton, Seaside, Tillamook, and St. Helens

• Subsidized housing in Astoria Moderate Rehabilitation-and Nehalem Rural Development USDA)

Astoria: Adult Outpatient Clinic, North Coast Wellness Center, Medication Assisted Treatment Program • 115 W Bond St.

Astoria: Open Door Program • 413 Gateway Ave.

Warrenton: Corporate Office, Developmental Disabilities

Administrative Office • 65 N. Highway 101, Suite 204

Warrenton: North Coast Crisis Repite Center • 326 S.E. Marlin Ave.

Seaside: Adult Outpatient Clinic • 1005 Broadway Mental Health

• Information and Referral

• Child/Adolescent 3-18 years-and Adult 18 +-Outpatient Counseling

• Psychiatric Medication & Prescription Drug Assistance.

• Case Management for Chronic Mental Illness, as appropriate

• Therapy and Skills-Training Groups for Children and Adults

• Project Intercept: early intervention (for psychotic disorders ages 14-25)

• Crisis Intervention and Stabilization Services

• Court-Mandated & Voluntary Individual & Group Outpatient Treatment Fees

• Private Insurance / Oregon Health Plan / Medicare

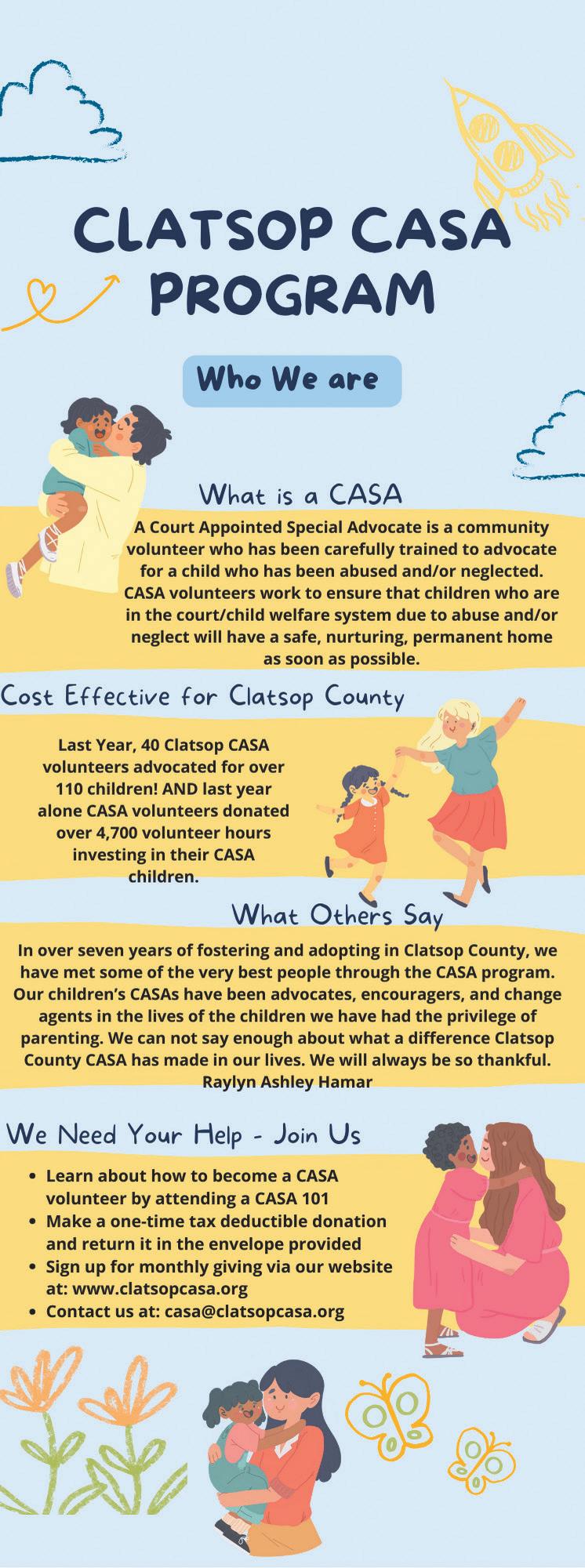

Clatsop Community Action (CCA)

364 9th St Astoria 503-325-1400 • Fax: 503-325-1153 • ccaservices.org

Community Resource Desk: 503-717-7176

• Temporary & Transitional Rental Assistance

• Case Management

• Transitional & Low-Income Housing

• Personal Care Pantry: hygiene, cleaning supplies & infant care items

• Information & Referral Services

• Energy Assistance Program / Wood Lot Program

• Veteran’s Support Services for veterans and their families

• Clothing Vouchers

• Community Resource Desk at Providence Seaside Hospital

Clatsop Community Action Regional Food Bank

Warrenton

2010 SE Chokeberry Ave, Warrenton • 503-861-3663 ccaservices.org/ Emergency food for pantries, meal sites, shelters, and food programs.

Clatsop County Public Health Department

820 Exchange St, Suite 100, Astoria, OR 97103 503-325-8500 • www.clatsopcounty.gov/publichealth

Babies First:

www.clatsopcounty.gov/publichealth/page/babies-first-program

Communicable Disease Control

www.clatsopcounty.gov/publichealth/page/communicable-disease

Environmental Health: www.clatsopcounty.gov/publichealth/page/environmental-health

HIV Counseling and Testing (formerly HIV Services): www.clatsopcounty.gov/publichealth/page/hiv-counseling-and-testing

Immunizations: www.clatsopcounty.gov/publichealth/page/immunizations

Sexually Transmitted Infections: clatsopcounty.gov/publichealth/page/sexually-transmitted-infections

Clatsop County Developmental Disabilities Program 65 N. Highway 101, Suite 210, Warrenton 503-325-5722

Developmental Disability Program serves children and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities ie: (Down Syndrome, Cerebral Palsy, Autism, Traumatic Brain Injury, etc.). The program works closely with other agencies to help with advocacy, in-home services, residential services, employment, abuse investigations, and more. www.clatsopbh.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Brochure_ DDServicesEnglish.pdf

Northwest Senior and Disability Services (NWSDS)

2002 SE Chokeberry Ave, Warrenton 503-861-4200 Fax: 503-861-0934 Toll Free: 800-442-8614

https://nwsds.org/index.php/home/about-us/where-to-find-us

Older American’s Act Programs for those 60 & older

• Training programs for caregivers & licensing of Adult Foster Homes

• Senior nutrition program (home delivered meals & meal sites)

• Senior Health Insurance Benefits & Prescription Drug Assistance (SHIBA)

• Oregon Project Independence (OPI)

Services for seniors & people with disabilities (eligibility requirements apply)

• Information & referral services / SNAP Food stamps-/ Medicaid

• Assess & evaluate service needs for placement

• Home Care Worker Registry for families who want to hire a caregiver

Adult Protective Services 800-846-9165

• Responds to reports of abuse /neglect for seniors and disabled persons.

Oregon Department of Human Services

Astoria Office 422 Gateway Ave. • www.oregon.gov/odhs

Update or apply for benefits at one.oregon.gov or call 800-699-9075

Child Welfare Programs:

503-325-9179

• Child Protective Services—respond to child abuse reports

• Voluntary Family Services—abuse prevention program

• Adoption services / Foster Care

Self Sufficiency Programs:

503-325-2021 Toll Free: 800-643-4606 / 503-325-6506 (Fax)

• Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly Food Stamps)

• Temporary Assistance for Needy Families / JOBS Program (TANF)

• Employment Related Day Care (ERDC)

• Domestic Violence Assistance (TA-DVS)

• Refugee Cash Assistance (RCA)

801 Commercial St (lower level), PO Box 1342, Astoria • harbornw.org 503-325-3426, 24/7 Support, 503-325-5735

Provides intervention & prevention services for survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking including trauma recovery counseling & groups.

SA Sexual Assualt-Peer Center

The case managers at The Harbor in our SA Peer Center are specially trained to identify the survivors needs, explain their options, connect them with appro-priate resources and answer questions regarding trauma responses. The SA Peer Center case management program ensures that sexual assault survivors have ongoing support and information based upon empowerment and trust.

24 hour Crisis Line: 503-325-5735 / 855-938-0584 Español

Northwest Oregon Housing Authority (NOHA)

147 S Main Ave, Warrenton • 503-861-0119

Fax 503-861-0220 • www.nwoha.org/

Geographical Area Served: Clatsop, Columbia, and Tillamook Counties

• Housing Choice Voucher program Section 8-including Family SelfSufficiency and Home Ownership programs

• Affordable housing units in Warrenton, Seaside, Tillamook, and St. Helens

• Subsidized housing in Astoria Moderate Rehabilitation-and Nehalem Rural Development (USDA)

• Subsudized Housing for elderly and disabled in Astoria & Warrenton

Consejo Hispano

https://consejohispano.org info@consejohispano.org • 503-325-4547

Consejo Hispano is a non-profit organization dedicated to serving the Hispanic community of Oregon and Washington. Our goals include promoting the health, education and social and economic advancement of area Latinos.

Astoria Rescue Mission

62 W Bond PO Box 114, Astoria • 503-325-6243 or 503-440-0789 astoriarescuemission.com

Provides clothing free of charge, emergency shelter and meal service.

Childrens Clothing Bank

Warrenton First Baptist Church • 30 NE 1st St, Warrenton 503-791-7522 or 503-861-2432

Free clothing age 0-12 yrs. Clothing Bank open the first weekend of the month only; Friday from 3 to 6 p.m., and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m

Northwest Community Alliance Thrift Store

207 7th St, Astoria 503-325-1011

Clothing, small appliances, & furniture.

Clothes Closet

Astoria First Baptist Church • 349 7th St, Astoria • 503-325-1761

Free clothing as available. Voucher from CCA required. Goodwill 1450 SE Discovery Ln, Warrenton •503-861-9517 • meetgoodwill.org

Low-cost second hand clothing, shoes, household goods, & furniture.

Clatsop Community Action Healthy Families

https://cat-team.org/child-family-programs

Through our Whole Family Approach, we aim to create lasting change that supports children and families from the earliest years and empowers them to build strong, stable, and successful lives.

Mentoring

800 Exchange St. Suite 200, Astoria. • 503-325-8601 Mentoring program for at risk youth.

Coast Pregnancy Clinic

279 6th St., Astoria • 503-325-9111 • 800-669-8717 coastpregnancyclinic.org

Parenting classes, pregnancy testing, ultrasound viability/gestation, baby clothing & supplies, adoption information. All services are free.

Clatsop County Prevention Services

800 Exchange #200, Astoria • 503-325-8601 co.clatsop.or.us/page/16?deptid=11 Youth skill building programs.

Northwest Parenting

503-614-3188, 503-325-2862 • nwparenting@nwresd.k12.or.us www.nwresd.org/departments/instructional-services/northwestparenting • Parenting program opportunities.

North Coast Food Web

1450 Exchange St., Astoria 503-468-0921 • northcoastfoodweb.org

Food web offers a variety of opportunities for children and adults to learn to cook, learn to shop on a budget, and attend their farmers market. Fees may apply, scholarships available.

Astoria Rescue Mission

62 W Bond St, Astoria • 503-325-6243 • 503-440-0789 astoriarescuemission.com

Serves lunch and dinner served daily. Must stay overnight to receive breakfast. Check for meal times.

Church of the Nazarene• 725 Niagara, Astoria 503-325-4477

Wednesdays, 6 to 7:15 p.m.Registration required at https://www.hilltopnazarene.org

Grace Episcopal Church Community Dinner 1545 Franklin, Astoria 503-325-4691.

Our Lady of Victory Sunday Supper 120 Oceanway St, Seaside • 503-738-6161 x110

Sunday Supper every Sunday at 3-4 p.m.

Warrenton Community Center

170 S.W. Third St., Warrenton; Lunch only served Tuesday for seniors.

Bob Chisholm Community Center 1225 Avenue A, Seaside, OR 97138 • 503-861-4221, ext. 6221

Cannon Beach Community Food Pantry

268 Beaver St.; Warrenton •971-326-0479.

CCA Regional Food Bank

2010 S.E. Chokeberry Ave., Warrenton 503-861-3663 • ccaservices.org Emergency food for pantries, meal sites, shelters and food programs.

Clatsop Emergency Food Pantry

First Presbyterian Church • 1103 Grand, Astoria • 503-325-1702

Open to Astoria residents only who meet income requirements. No mention of monthly food boxes.

Grace Food Pantry

Grace Episcopal Church •1545 Franklin St, Astoria • 503-325-4691 Tuesdays and Thursdays from 9 to 11:30 a.m.

Knappa Food Pantry

42889 Old Hwy 30, Knappa • 503-458-6492 • Tues & Thurs 2-3pm.

Manna House Food Pantry

Lighthouse Christian Church • 88786 Dellmoor Loop Rd, Warrenton 503-738-5182 call Mon-Fri, 9am-4pm. Open third Saturday of the month from 9 to 11 a.m.

St. Vincent de Paul Food Pantry

3575 Hwy 101 N, Gearhart

Mon. and Fri. from 1 to 3 p.m., last Sat. of the month, 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. 1465 Grand Ave, Astoria •503-325-2007 message phone. Tuesday from 1 to 3 p.m., Friday from 10 a.m. to noon, last Saturday of the month from 10 a.m. to noon

South County Community Food Bank

2041 N Roosevelt, Seaside • 503-738-9800 Tuesday and Thursday, 1 to 4 p.m.

Must sign up to participate.

Seaside Food-4-Kids

Formerly the Backpack Program. Bags of food for kids in Seaside grade school and middle school who need weekend assistance. Parents from Gearhart and Seaside can apply to the program through the Seaside School District.

Warrenton/Hammond Healthy Kids

Warrenton Grade School • 820 SW Cedar, Warrenton 503-861-2281

Food Backpack Program, a supplemental food program offered to students who need extra food for weekends.

Clatsop Comunity College

1651 Lexington Ave, Astoria

503-338-2411 • clatsopcc.edu/

Adult Education

503-338-2411

www.clatsopcc.edu/pre-college-adulteducation

Adult Basic Education and GED Preparation.

Lives in Transition

503-338-2377

Gain self-sufficiency, explore career options, & personal action plans.

English as a Second Language

503-338-2557 • epurcell@clatsopcc.edu

www.clatsopcc.edu/esl/ Free ESL classes at Clatsop Community College.

TRIO Student Support Services Program (CCC)

503-325-2898

Support & advising for first-generation college students, low-income, or disabled.

Upward Bound Program/ TalentSearch (CCC)

503-325-2898

www.clatsopcc.edu/upward-bound

Connect first-generation, low-income students to educational opportunities.

Social Security Administration

Volunteer Literacy Program (CCC)

503-338-2557

Gain or improve basic literacy skills.

South County Campus (CCC) 1455 Roosevelt Drive, Seaside • 503-338-2402

Tongue Point Job Corps Center

37573 Old Hwy 30, Astoria • 503-325-2131 tonguepoint.jobcorps.gov

No-cost education & career technical training program for ages 16—24

OR Office of Student Access and Completion

541-687-7400 •oregonstudentaid.gov

Migrant Student Information exchange www.wesd.org/departments/omesc/recordstransfer-systems. Help for migrant families with transfer of school records/enrollment.

Head Start

Head Start is preschool for ages 3-5 from families at or below federal poverty guidelines. Children do not need to be pottytrained. nworheadstart.org/

1479 SE Discovery lane, Suite 104, Warrenton OR 97146 ssa.gov • Fax Number: 833-950-3242

Caring for the Coast

1479 SE Discovery Lane, Suite 103, Warrenton, OR 97146 503-325-4503

caringforfamilyofcompanies.com/caring-for-the-coast/ Medication administration & nursing, personal care, & homemaker services.

Astor House

999 Klaskanine, Astoria 503-325-6970

Clatsop Retirement Village 947 Olney Ave, Astoria • 503-325-4676 clatsopcare.org

Neawanna by the Sea 20 N Wahanna, Seaside • 503-739-8896

Necanicum Village Senior Living 2500 S Roosevelt, Seaside • 503-738-0900

Suzanne Elise

101 Forest Dr, Seaside • 503-476-9244 • suzanneelise.com

NW Regional Education Service District (ESD or NWRESD) 785 Alameda Ave., Astoria • 503-325-2862 www.nwresd.org/Home/Components/ FacilityDirectory/FacilityDirectory/37/33 for children with disabilities 0 to 5 years.

Astoria Head Start 785 Alameda Ave 503-325-5421

Warrenton Head Start

200 SW 3rd, Warrenton• 503-861-9681

Seaside Head Start 1225 2nd Ave., Seaside • 503-738-0873

Preschool Promise

785 Alameda Ave Astoria 503-325-6431

Working in collaboration with the Astoria Head Start. Preschool for students aged 3-5, must be potty-trained, free tuition for qualifying parents, Astoria only.

Sunset Empire Park & Recreation Department 503-738-3311 • www.sunsetempire.com

Find Childcare Oregon

https://findchildcareoregon.org

Clatsop Care 646 16th Street, Astoria, OR 97103 • 503-325-0313 • clatsopcare.org

Astoria Senior Center 1111 Exchange St, Astoria, OR 97103• 503-325-3231

Bob Chisholm Community Center 1225 Avenue A, Seaside • 503-738-7393

Warrenton Community Center 170 SW 3rd Warrenton • 503-861-2233

Transportation

Dial-a-Ride

503-861-7433 • The reservation line is open Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Reservations must be made 2 or more days in advance. nwconnector.org/rideassist-dial-a-ride-setd

Oregon Dept. of Veterans Affairs Federal Building

100 SW Main, 2nd Floor, Portland 800-827-1000• www.benefits.va.gov/portland Resources for veterans, spouses & families.

Clatsop Community Action 364 9th, Astoria 503-325-1400

Housing support for homeless & at-risk veterans & their families. Clatsop County Veterans Service Officer 971-308-1045 • clatsopvso@gmail.com ww.clatsopcounty.gov/county/page/clatsop-countys-veteranservices-program. Assist with veteran’s benefit programs. M-F, 9 a.m.-3 p.m. by appointment only Military Helpline 888-457-4838 • www.linesforlife.org/get-help-now/services-andcrisis-lines/military-helpline

For all military service members, veterans, and their families.

VA National Call Center for Homeless Veterans 877-424-3838, Available 24/7 www.va.gov/HOMELESS/NationalCallCenter.asp Connects vets with local services.

Veterans Crisis Line, 24x7

Dial 988 and Press 1, call 800-273-8255 and Press 1, Text 838255, or chat online at www.veteranscrisisline.net Suicide prevention & mental health

Veterans Employment Rep. 1111 N. Roosevelt Drive, Suite 108, Seaside 503-378-8060 • www.worksourceoregon.org

Joint Services Support 800-342-9647 • www.militaryonesource.mil Assistance with family deployment and reintegration concerns.

Astoria Community Based Outpatient Clinic 3196 Marine Drive, Astoria, OR 97103 • 503-220-8262 Ext. 52593, Mental health care: 503-273-5187

Portland VA Medical Center 3710 SW US Veterans Hospital Rd, Portland • 503-220-8262 Vancouver VA Medical Center 1601 East 4th Plain Blvd., Vancouver, WA 98661-3753 • 360-759-1901

Disabled American Veterans

8725 NE Sandy Blvd. Portland; 503-255-0171 • dav.org • Help vets with legal concerns about disability.

Veteran’s Benefits Administration

100 SW Main St, Floor 2, Portland 800-827-1000 • www.va.gov/portland-va-regional-benefit-office Provides information veterans, their de-pendents, and survivors

Transportation

North Coast DAV Veterans Medical Transport 971-308-1045 • Free transportation to Portland Dept. of Veterans Affairs. Must schedule in advance.

Homeless or “at-risk” Veterans We Have Resources for You! Clatsop Community Action 503-325-1400

Thank you Clatsop & Pacific Counties for your business! We continue to thrive through our Tour Operator Business Sundial Tours, our National component for developmentally disabled group guided tours Sundial Special Vacations and our local Double-Decker Coaches, Vans, Shore Excursions and High-End Private Tours, Sundial Shorex. What a great 53 years, we look forward to serving and supporting our community for another 53 years in all our endeavors. - Sundial Tours Remarkable Staff

Columbia Memorial Hospital

Main Campus

2111 Exchange St. Astoria • 503-325-4321 columbiamemorial.org

Inpatient suites, an emergency department that is staffed by emergency medicine physicians from OHSU, a family birthing center, surgical program, full-service lab, advanced radiology services, insurance assistors, and more.

CMH Health & Wellness Pavilion

2265 Exchange St., Astoria • 503-325-4321 Services: Foot and ankle, imaging, laboratory, orthopedics, physical therapy, rehabilitation, sports medicine, urgent care, urology, women’s health.

CMH Park Medical Building, East 2158 Exchange St. • Astoria

• Astoria Primary Care • Diabetes Education

• Endocrinology Clinic • Imaging Services

• Laboratory • Pediatric Clinic

• Medical Nutrition Therapy

CMH Park Medical Building, West 2120 Exchange St. • Astoria

• Outpatient Pharmacy • Pediatric Physical and Occupational Therapy • Speech Therapy • Lower Columbia Hospice.

CMH-OHSU Knight Cancer Collaborative 1905 Exchange St., Astoria • 503-338-4085

Located adjacent to the hospital, facility expands existing medical oncology and chemotherapy treatment services, and bring needed radiation oncology and radiation therapy to the North Oregon Coast.

CMH-OHSU Health Primary Care - Warrenton 1639 SE Ensign Lane, Suite B103, Warrenton, OR 503-338-4500 • After hours: 503-298-4963 • extended hours, x-ray and lab services.

CMH-OHSU Health Primary Care – Seaside 1111. N. Roosevelt #210 • Seaside, OR 97138 • 503-738-3002 After hours: 503-298-4963 extended hours, x-ray and lab services.

• Foot & Ankle • Imaging

• Laboratory • Pediatrics

• Pharmacy • Primary Care

• Urgent Care • Womens Health

Providence Medical Group

Providence Seaside Hospital

725 S. Wahanna Rd., Seaside • 503-717-7000 www.providence.org/locations/or/seaside-hospital

Providence North Coast Clinics

• Cannon Beach — 171 N. Larch Suite 16 • 503-717-7400 |

• Seaside — 727 S. Wahanna Rd • 503-717-7060

• Walk-In Clinic — Open 7:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Monday through Saturday daily in Seaside

• Warrenton — 171 S. Highway 101 • 503-861-6500

Providence Oncology & Hematology Care Clinic

725 S. Wahanna Road, Suite 100, Seaside • 503-717-7650

Providence ElderPlace North Coast 1150 N Roosevelt Dr. Suite 104, Seaside • 503-717-7150

Providence Heart Clinics North Coast 503-717-7850

• 1355 Exchange St, Astoria

• 725 S. Wahanna Road., Suite 101, Seaside

Providence Home Health Services 503-717-7788

Providence Rehabilitation Services-Gearhart 3621 Highway 101 N., Gearhart • 503-717-7789

2120 Exchange St Suite 111, Astoria 503-325-0333 • www.urgentcarenwastoria.com

Express Healthcare for Busy Lifestyles. For all of your healthcare needs, not just emergencies.

• Accepting Most Insurance

• 20% Cash Discount

• Accepts Oregon Health Plan and Medicare

2158 Exchange St Suite 304, Astoria 503-325-8315

www.yvfwc.com/locations/coastal-family-health-center

• Family primary care provider

• Adolescent healthcare and Well Child Checks

• Chronic disease management & comprehensive healthcare

• Discount pharmacy & laboratory services

• Immunizations & physicals

• Men’s & Women’s healthcare

• Insurance assistor & sliding scale medical services

• Referrals for dental, mental health, substance abuse & specialized care

• Patient Education

www.clatsopcounty.gov/publichealth/page/covid-19-testing

Clatsop County Department of Public Health works with Oregon Health Authority, Public Health Divisions’s Acute and Communicable Disease Prevention Program to detect, track, prevent and control the sperad of infectious diseases.

For information on COVID-19 vaccines, testing and resources see:co.clatsop.or.us/publichealth/page/covid-19-news-information

Medix Ambulance Service 2325 SE Dolphin Ave, Warrenton 503-861-1990 • medixambulance.org

Nationally recognized. Locally owned. Medix Ambulance provides advanced life support 9-1-1 ambulance response for all of Clatsop County.

Children’s Dental Program 800-342-0526

modahealth.com/about/childrens.shtml

Uninsured children 5-18 yrs. (OHP is a dental plan). Must be referred.

Geriatric Dental Group 16500 SE 15th St., Suite 150, Vancouver, WA 360-326-3829

Reduced dental rates for adults 55+.

Dental Van 503-325-8500 • www.clatsopcounty.gov/ publichealth/page/upcoming-dental-van-events

Call for appointments.

Check website for Dental Van events.

Astoria Parks and Recreation (ARC)

1997 Marine Drive, Astoria • 503-325-7027 astoriaparks.com/dept/Parks_Recreation

Maintains various community parks, athletic fields, programs, and events.

Astoria Aquatic Center

1997 Marine Dr, Astoria • 503-325-7027 Swimming, swimming lessons, and fitness classes. Fees apply.

Astoria Public Library

Temporary location while under renovation: 1512 Duane Street

450 10th St, Astoria • 503-325-7323 www.astoria.gov/dept/Library

Free book check out for Astoria residents. Children’s reading programs.

Astoria Senior Center 1111 Exchange, Astoria • 503-325-3231 astoriaseniorcenter.org

Exercise classes, bingo, bridge, pinochle, movies and more.

Blood Pressure checks: 3rd Thursday, 10-11 :30 a.m.

Bob Chisholm Community & Senior Center

1225 Ave. A, Seaside • 503-738-7393 • sunsetempire.com

The Community Center hosts activities for all ages: weddings, educational events, clubs and organizations of all types, hearing tests, martial arts for all ages, flu shots, health screening, hearing services, info & more.

Senior Meals: 11:30 a.m. Mon. - Fri. for 60-plus. Small donation.

Home Delivery: Available Mon., Wed. & Fri.

Scouting America

503-226-3423 • www.cpcbsa.org or Facebook Prepares boys & girls to make ethical & moral choices through service, mentoring & leadership development.

Camp Kiwanilong PO Box 128, Warrenton • 503-861-3905, 503-298-0767 campkiwanilong.org Summer camp opportunities for youth.

Cannon Beach Library 131 N Hemlock St, Cannon Beach, OR 97110 • 503-436-1391 cannonbeachlibrary.org

Clatsop Community College Dora Badollet Library 1651 Lexington Ave., Astoria • 503-338-2462 www.clatsopcc.edu/library Non-students may use internet and library space free of charge, book check out for students or paying patrons.

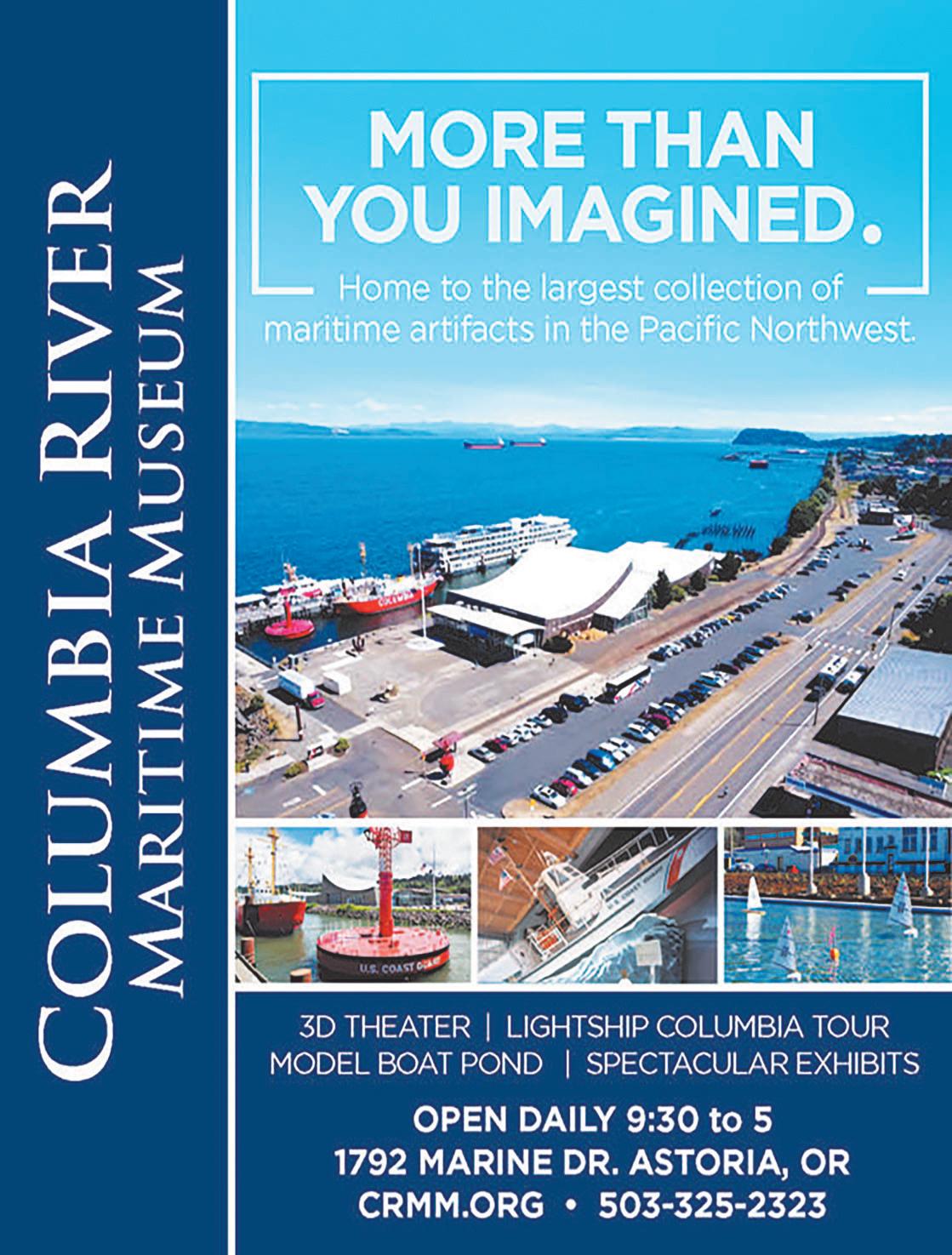

Columbia River Maritime Museum 1792 Marine Dr, Astoria • 503-325-2323 • crmm.org Interactive exhibits that combine history with technology.

Flavel House Museum 714 Exchange St., Astoria • 503-325-2203 astoriamuseums.org Historic Victorian home.

2001 Marine Drive, Room 210, Astoria, OR 97103 503-325-8573

Girl Scouts of Oregon & SW Washington 800-338-5248 • girlscoutsosw.org Positive leadership, mentoring & community services for girls.

Heritage Museum 1618 Exchange St, Astoria • 503-325-2203 astoriamuseums.org

Regional museum for Clatsop County. Exhibits on geology, natural history, industry & people of the area.

Lower Columbia Youth Soccer Association lcysasoccer.com • lcysasoccer.com/contact

OSU Clatsop Extension Office

2001 Marine Dr, Rm 210, Astoria • 503-325-8573 extension.oregonstate.edu/county/clatsop/what-we-do

Provides outreach through educational programs, working with community partners through gardening and farm-ing, food and nutrition, 4-H, health and wellness, and environmental programs. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/clatsop

Seaside Museum & Historical Society 570 Necanicum, Seaside 503-738-7065 seasideoregonmuseum.com

Exhibits on Native Americans & history of Seaside. Entrance fee applies.

Seaside Public Library 1131 Broadway, Seaside 503-738-6742 seasidelibrary.org

Sunset Empire Park & Recreation Department 1140 Broadway, Seaside 503-738-3311 sunsetempire.com

Maintains the pool, various community events, after school programs, pre-school, youth center middle schoolers, programs, and events for children, families, and adults.

Uppertown Firefighters Museum 2968 Marine, Astoria • 503-325-2203 astoriamuseums.org

(Clatsop County Historical Society) Collection of firefighting equipment & photos of Astoria fires.

Warrenton Community Center

170 SW 3rd, Warrenton • 503-861-2233

Gathering place with full kitchen for functions such as Senior lunches, Wedding Receptions, Company Parties, Meetings & much more.

Warrenton Community Library 160 S Main St, Warrenton • 503-861-8156 www.warrentonlibrary.org Facebook—Free book check-out for residents of Warrenton and Hammond.

The Seaside Promendae is a 1 1/2 mile long concrete walkway along the oceanfront from Avenue U to 12th Avenue. The turnaround at the west end end of Broadway Avenue features a statue of Lewis and Clark.

Buying a house is one of the largest purchases you'll make, but your Fibre Family will help keep your costs and stress to a minimum. We'll recommend a mortgage loan that's perfect for you because, well, we get to know you.

Astoria

Astoria Christian Church 1151 Harrison • 503-325-2591

Astoria Church of Christ 692 12th St. • 503-325-7398

Astoria First United Methodist Church 1076 Franklin • 503-325-5454

Astoria Baha’i Community 447 Alameda Ave., 503-325-4907

Baha’is of Clatsop County 41590 Hillcrest Loop • 503-338-8469

Bethany Free Lutheran Church 451 34th St • 503-325-2925

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints

350 Niagara Ave. • 503-325-8346

Coastline Christian Fellowship 89386 Hwy. 202 • 503-325-1051

First Assembly of God 1775 7th St. • 503-325-7331

First Presbyterian Church 1103 Grand Ave. • 503-325-1702

First Baptist Church of Astoria 349 7th St. • 503-325-1761

First Church of Christ Scientist 632 11th St. • 503-325-5661

Grace Community Baptist Church 1195 Irving • 503-325-2263

Grace Episcopal Church 1545 Franklin • 503-325-4691

Hilltop Church of the Nazarene 725 Niagra • 541-301-2238

Kingdom Hall of Jehovah Witnesses 1760 7th St. • 503-325-7153

Lewis & Clark Bible Church 35082 Seppa Lane • 503-325-7011

New Life Church 490 Olney Ave. • 503-325-7003

Peace First Lutheran Church 725 33rd St. • 503-325-6252

Olney Community Church 87869 Highway 202 • 503-325-339

St. Mary, Star of the Sea Catholic Church 1465 Grand Ave • 503-325-3671

Calvary Assembly of God 1365 S. Main Ave., Warrenton 503-861-1712

Evergreen Christian Church of Warrenton 1376 SE Anchor Ave. • 503-861-1714

First Baptist Church of Warrenton 30 NE 1st St., Warrenton 503-861-2432

Gateway Community Church 796 Pacific Dr., Hammond 503-861-3333

Lighthouse Christian Church 88786 Dellmoor Loop • 503-738-5182

Pioneer Presbyterian Church 33324 Patriot Way, Warrenton 503-861-2421

North Coast Family Fellowship 2245 N. Wahanna Rd. • 503-738-7453

Our Lady of Victory Church 120 Oceanway • 503-738-6161

Our Savior’s Lutheran Church 320 1st Ave. • 503-738-6791

Astoria Riverfront Trolley Association — 111 W. Marine Drive

Astoria Riverfront Trolley Association needs conductors/ motormen to operate trolley and narrate points of interest. One or more three-hour shifts per month. For information, call the 503-325-6311 or go to old300.org

River of Life Fellowship 1000 Ave. F • 503-738-5534

Seaside Calvary Church 240 S. Roosevelt Drive 503-741-9455

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints 1403 S Wahanna Rd. • 503-738-7543

Seaside Adventist Church 1450 N Roosevelt Dr. 503-741-9455

Seaside United Methodist Church 241 N. Holladay 503-738-7562

Calvary Episcopal Church 503 N. Holladay 503-738-5773

Nehalem Valley Community Church 80803 Highway 103 503-755-2376

Cannon Beach

Cannon Beach Bible Church 264 Hills Lane • 503-436-4114 cbbiblechurch@gmail.com

Cannon Beach Community Church 132 E. Washington St. • 503-436-1222

Crossroads Community Church A Friends Fellowship 40618 Old Highway 30 503-458-684

Evergreen Christian Church of Knappa 42417 Valley Creek Ln 503-861-1714

Westport Community Church 49246 Highway 30

Sunset Empire Transportation

Provides bus service in Clatsop County on various fixed routes. 900 Marine Drive, Astoria 503-861-7433 TTD • 800-735-2900 nwconnector.org/ agencies/sunset-empire-transportation-district/

RideAssist

Provides public transportation to persons with disabilities who are unable to use regular fixed route buses. Must be scheduled at least 1 day in advance. Call for more information. 503-861-7433

RidePal

Seniors and people with disabilities are partnered with community volunteers to learn how to ride the bus safely and independently. • 503-861-5361

Northwest Rides

NW Ride Center provides transportation or gas reimbursement for eligible health plans & Medicaid clients traveling to covered medical services: need to call at least 2 days in advance if possible. 503-861-0657 / Toll-free 888-793-0439.

POINT

888-846-4183 • oregon-point.com

The Northwest route provides daily bus service between Portland and the Northwest Oregon coast, serving Astoria, Seaside, Warrenton, Gearhart, Cannon Beach and Elsie. There are two trips per day each direction. Purchase tickets from Amtrack at 800-872-7245 or local location listed on website.

Car Rentals

Enterprise Rent-A-Car

503-325-6500

Cab Companies

Royal Cab

503-325-5818

Aalpha Shuttle & Taxi Seaside

503-440-7777

Downtown Coffee Shop Taxi

503-791-6728

West Basin Marina

10 Pier One Suite 102, Astoria • Marina Office & Fuel Dock: 503-325-8279 • marina@portofastoria.com

Located just west of the Astoria-Megler Bridge at mile 14 on the Columbia River, the Port of Astoria’s West Basin Marina is well-suited to recreational boat moorage, but is also home to fishing boats, guide boats and other commercial vessels.

Located at river mile 13 at the mouth of the Columbia River, the Port of Astoria’s haul-out facility and ample boatyard are ideally situated for boaters from the Columbia River basin. The facility includes an 88ton TraveLift®, offering excellent lift efficiency and providing greater versatility when placing the vessel ashore for storage or repairs. A wash down system makes it easier to remove algae and barnacles from a boat bottom, and dispose of this material properly. Haul-Out Reservations are required, and may be made by calling the Marine Service Supervisor 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. at 503-791-7731. Boat owners may contract for repair work with an on-site marine repair business, or lease boatyard space for do-it-yourself work.

Astoria Regional Airport

www.portofastoria.com/airport

1110 SE Flightline Drive, Warrenton • 503-861-1222

Operated by the Port of Astoria. No commercial service. Hangars available.

Astoria was established in 1810 as the first permanent U.S. settlement west of the Rocky mountains. Men from the Tonquin, an Pacific Fur Company ship, named the outpost after owner John Jacob Astor. During the U.S. war with the British in 1812, isolation and lack of military protection caused Pacific Fur Company to fold, and the assets were sold to the British North West Company. From 1813 to 1818, the British owned Astoria, referred to during that time as Fort George. In 1818, a treaty with England established joint occupation of the Oregon Country. The first U.S. Post Office west of the Rocky Mountains was established in Astoria in 1847, and in 1854 Astoria was chosen by electors as county seat for recently created Clatsop County.

Population (2023): 9,986

Elevation: 23’

Incorporated: Oct. 20, 1876 Households: 4,420

City of Astoria

1095 Duane St., Astoria, OR 97103 503-325-5821 • www.astoria.gov

Astoria is governed by a five-member city council, including an elected mayor, and four councilors representing geographic districts, or wards. The council appoints the city manager, city attorney and municipal judge. City council meetings are generally held the first and third Monday of the month at 7:00 P.M.

Astoria Public Library

450 10th Street, Astoria, OR 97103

503-325-READ (7323) www.astoria.gov/dept/Library

Water/Sewer Department

City of Astoria 1095 Duane Street • 503-338-5172 www.astoria.gov/page/108

Astoria Post Office

750 Commercial St. Astoria, OR 97103

Zip Code 97103

Astoria School District 785 Alameda Avenue, Astoria, OR 97103 503-325-6441

www.astoria.k12.or.us/

Astoria Parks & Recreation 1997 Marine Drive 503-325-7027

Astoria High School 4A, Fishermen • Grades 9 - 12 1001 W. Marine Drive, Astoria, OR 97103 • 503-325-3911

Astoria Middle School Grades 6 - 8 1100 Klaskanine Ave., Astoria, OR 97103 • 503-325-4331

Lewis & Clark Elementary Grades 3-5

92179 Lewis and Clark Rd.,Astoria, OR 97103 • 503-325-2032

John Jacob Astor Elementary School Grades K-2

3550 Franklin Avenue, Astoria, OR 97103 • 503-325-6672

Astoria Choice Academy 785 Alameda, Astoria • 503-325-4197

For information, go to clatsopcruisehosts.org

During spring and fall Astoria is usually a popular port of call for Cruise Ships. Cruise visitors are obvious by their identifying badge. Clatsop Cruise Hosts are always looking for volunteers to meet and greet cruise ship passengers and crew, provide information and answer questions about the Clatsop County area. portofastoria.com/Cruise_Schedules.aspx

Warrenton is named for Daniel Knight Warren, who reclaimed a large tract from the tidal flats by constructing a dike over two miles long completed in 1878.

Warren platted the city in 1889 and it was incorporated in 1899. D.K. Warren’s historic home, built in 1885 and recently restored, is located on NE Skipanon Drive.

Hammond was originally incorporated as New Astoria in 1899. The name was changed to Hammond in 1915 to reflect the name of the railroad station and post office, named for lumberman Andrew B. Hammond, who completed the Astoria and Columbia River Railroad. The city voted to disincorporate in November 1991 and merged with the city of Warrenton.

Population (2023): 6,255

Elevation: 8’

Incorporated: Feb. 11, 1899

Households: 2,241

Median Home Sale Price: $490,000

Source: Realtor.com Sept. 2024

Source: US Census Quick Facts

City of Warrenton

225 S Main Ave., Warrenton, OR 97146

503-861-2233 • warrentonoregon.us

Warrenton has a five-member elected city commission, including an elected mayor. The city manager administrates the city’s business. The Warrenton City Commission generally meets at 6:00 p.m. on the 2nd and 4th Tuesday of the month at Warrenton City Hall.

Department

225 S. Main Ave.

503-861-2233 www.warrentonoregon.us/ utilitybilling

Warrenton Community Library

160 S Main Ave Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-8156 warrentonlibrary.org

Warrenton Post Office 99 N. Main Ave. Warrenton, OR 97146 Zip Code 97146

Hammond Post Office 906 Pacific Drive Hammond, OR 97121 Zip Code 97121

Warrenton-Hammond School District 820 SW Cedar Ave Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-2281 warrentonschools.com

Warrenton High School 2A, Warriors Grades 9-12 1700 SE Main, Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-3317

Warrenton Middle School

Grades 6-8 1050 SE Warrior Way, Warrenton, OR 97146 971-445-4500

Warrenton Grade School

Grades K-8 820 SW Cedar Ave. St.,Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-3376

Parks & Trails www.warrentonoregon.us/ parksandtrails

92343 Fort Clatsop Rd. Astoria

Fort Clatsop is the reconstructed winter encampment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, located within the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park near Astoria, Oregon. The replica fort and surrounding park offer visitors a look into the Corps of Discovery's experiences during the winter of 1805–1806, before their journey back east.

Fort Clatsop is operated by the National Park Service and includes a visitor center with films and exhibits. The site is located about 5 miles southwest of Astoria.

Fort Stevens, Ft Stevens Ridge Trail, Hammond

Battery Russell is a former U.S. coastal artillery battery located within Fort Stevens State Park in Oregon. Built in 1904, it was part of the Columbia River's harbor defense system and is a significant historic site.

Battery Russell was one of several fortifications at Fort Stevens, which was built to protect the entrance of the Columbia River.

Astoria Fultano’s first opened in March of 1978, known as Pizza Vendor, owned & operated by Bob & Jeanette Fulton & was renamed Mr. Fultano’s Pizza a couple of years later.

Robert & Cheryl Fulton purchased the business in 1982. They owned & operated Fultano’s until it was sold to Mark Cary in 1998. In 2003, Fultano’s expanded by adding the party & game room.

In March 2024 a new sports bar addition was opened!

To this day, Mark & LaDonna continue to operate Fultano’s staying true to their commitment, “Our family serving your family the best pizza in own!”

The city of Seaside is thought to have been named from Seaside House, a grand summer home built in 1871 by railroad magnate Ben Holladay. Ben Holladay has a Seaside street named for him as well.

The Promenade, or “Prom,” was established by real estate developer and Seaside mayor Alexandre Gilbert, who donated land to the City of Seaside for its development along the Pacific beach in 1912. Following a devastating fire in 1912, Gilbert helped businesses rebuild in Seaside, and established the Gilbert District east of the Neanicum River on Broadway. The historic Gilbert House is located at 341 Beach Drive.

Population (2023): 7,164

Elevation: 17’

Incorporated: Feb. 17, 1899

Households: 3,600

Seaside North Central Median Home Sale Price: $482,000

Source: Realtor.com, Sept. 2024

Source: US Census Quick Facts

City of Seaside

989 Broadway, 97138

503-738-5511

www.cityofseaside.us

Seaside is governed by a sevenmember city council, including the elected mayor and appointed council president. The city manager is administrator for city business. Seaside City Council meetings are generally the second and fourth Mondays of the month at 6 p.m. at City Hall.

Water/Sewer Department

City of Seaside 989 Broadway, 97138

503-738-5511

www.cityofseaside.us/ finance-department/ pages/water-sewer-utilities

Seaside Public Library 1131 Broadway Seaside, Oregon 97138

503-738-6742

Seaside Post Office

300 Avenue A Seaside, OR 97138 Zip Code 97138

Seaside School District

2600 Spruce Drive, Ste. 100 Seaside, OR 97138

503-738-5591

www.seaside.k12.or.us

Seaside High School 4A, Seagulls Grades 9-12

2600 Spruce Dr. #200

Seaside, OR 97138

503-738-5586

Seaside Middle School Grades 6-8

2600 Spruce Dr. #200 Seaside, OR 97138

503-738-5586

Pacific Ridge Elementary Grades: K-5

2000 Spruce Drive

Seaside, OR 97138

503-738-5161

Sunset Empire Park and Recreation Department

See Recreation on Page 16 www.sunsetempire.com 503-738-3311

Bob Chisholm Community Center 1225 Avenue A 503-738-7393

School 9:30 am Sunday Worship 10:45 am www.fbcastoria.org

Rickenbach Construction was started by John Rickenbach in Astoria in 1965.

For 60 years, Rickenbach Construction has worked to become one of the Pacific North Coast’s foremost commercial general contractors including restoration, historical renovation, design/ build, seismic, structural and other upgrades, custom commercial and residential construction.

Rickenbach Construction will effectively meet the challenge of keeping historical authenticity, assuring weather protection and structural stability, and maximizing the changing functionality of buildings in our community. We have completed projects in three Northwest Oregon Counties and Southwest Washington including numerous new buildings, additions, remodels and restorations.

As a family-owned business, Jared Rickenbach, president, and Michelle Dieffenbach, architect, have established the company’s reputation for honesty, dependability, teamwork, problem solving, quality craftsmanship, schedule and project management.

Rickenbach Construction, Inc., is committed to building your trust first.

The city is named for Phillip Gearhart, a settler from Missouri who in 1851, bought acreage on the Clatsop Plains. He increased the size of his holdings in 1859, and again in 1863 so that the parcel encompassed all of what is now Gearhart, as well as a portion of Seaside across the Necanicum River estuary. In 1889, a railroad was built between Astoria and Seaside. It carried vacationing Portlanders from the ferry in Astoria to Gearheart, increasing the numbers of vacationers who were drawn to.Gearhart for relaxing summer days at the beach, wandering the Ridge Path through the dunes and meadows of the Phillip Gearhart land claim.

Population (2020): 1,921

Elevation: 16’

Incorporated: Jan. 28, 1918

Housing Units: 1,513

Median Home Sale Price Gearhart West: $723,000

Source: Realtor.com, Sept. 2024

City of Gearhart

P.O. Box 2510, 698 Pacific Way., 97138 • Phone: 503-738-5501 • www.cityofgearhart.com

Gearhart is governed by a five member city council, included an elected mayor. City business is directed by the City Administrator. City Council Meetings are generally held the first Wednesday of every month at 7 p.m. at Gearhart City Hall, 698 Pacific Way.

Water/Sewer Department

City of Gearhart

503-738-5501

Gearhart Post Office

546 Pacific Way, Seaside, OR 97138 Zip Code 97138

Gearhart Golf Links 1157 N. Marion Ave, Gearhart, OR 97138 503-738-3538 www.gearhartgolflinks.com

Beach Wheelchair Rental 800-547-0115

Gearhart by the Sea Resort 1157 N Marion, Gearhart, OR 97138

Pacific Ridge Elementary Grades: K-5 2000 Spruce St., Seaside, OR 97138 503-738-5161

Gearhart Middle and High School Students attend Seaside schools

Tips for coexisting with Roosevelt Elk in Gearhart

Enjoy watching from a distance. Keep pets on a leash at all times. Elk are most active at dawn and dusk, but avoid human and pet conflicts during September & October breeding season-and May & June (when calves are born). Non-native vegetation attracts Elk. To move a herd off of you property, calmly approach the herd making your presense obvious. Avoid surprising the Elk or being aggressive. Source: City of Gearhart.

William Clark and several of his companions from the Corps of Discovery, including Sacagawea, made a three-day journey from Fort Clatsop on January 10, 1806, to the site of a beached whale. They encountered a group of Native Americans from the Tillamook tribe who were boiling blubber for storage. Ehkoli is thought to be a native word for “whale,” so Clark named the site Ecola Creek. Later settlers renamed the creek “Elk Creek,” a name that was also given to the settlement that developed nearby.

A cannon from the US Navy schooner Shark washed ashore just north of Arch Cape in 1846, a few miles south of Elk Creek. As a result, in 1922, Elk Creek was renamed Cannon Beach.

The shipwrecked cannon is in the city’s museum and a replica of it can be seen alongside U.S. 101. More artifacts from the Shark, and information about the settlement can be seen at the Columbia River Maritime Museum in Astoria.

Population (2021): 1,489

Elevation: 30’

Incorporated: Mar. 5, 1957

Housing Units: 1.888

City of Cannon Beach

Median Home Sale Price: $1.1 million

Source: Realtor.com, Sept. 2024

163 E. Gower, Cannon Beach, OR 97110 • 503-436-1581

Cannon Beach residents elect a mayor and four-member City Council to govern the city. The City Council appoints a city manager as administrator of city business. City Council meetings are generally held on the first Tuesday of the month at 7:00 pm at City Hall.

Tolovana Park

Tolovana Park is an unincorporated community located south of Cannon Beach.

Tolovana Park Post Office

3140 S. Hemlock St., Tolovana Park, OR 97145 • Zip Code 97145

Arch Cape

Arch Cape is an unincorporated community named for the arch in the coastal rocks and the cape on the Pacific Ocean. Arch Cape is located between Hug Point State Recreation Site to the north and Oswald West State Park to the south about four miles south of Cannon Beach .

Water/Sewer/Stormwater Departments

City of Cannon Beach, 503-436-1581

Cannon Beach Post Office

163 N Hemlock, Cannon Beach, OR 97110 Zip Code 97110

Schools

Cannon Beach is included in Seaside Schools

Cannon Beach Academy Private. Grades: K-5 3781 S Hemlock St., Cannon Beach, OR 97110 503-436-4463 thecannonbeachacademy.org

Cannon Beach Library

131 N. Hemlock, Cannon Beach 97110 cannonbeachlibrary.org • 503-436-1391

Haystack Rock Awareness Program (HRAP)

www.haystackrockawareness.com 503-436-8060

Haystack Rock is a 235 ft-tall (72 m) sea stack in Cannon Beach, Oregon. The monolithic rock is adjacent to the beach and accessible by foot at low tide. Tide pools are home to many intertidal animals, including starfish, sea anemone, crabs, chitons, limpets, and sea slugs. The rock is also a nesting site for many sea birds, including terns and puffins.

Haystack Rock is composed of basalt and was formed by lava flows emanating from the Blue Mountains and Columbia basin about 15-17 million years ago. Three smaller, adjacent rock formations to the south of Haystack Rock are collectively called “The Needles”.

The unincorporated community of Knappa is located on Highway 30 near the Columbia River. The community is named after Aaron Knapp, Jr., an early owner of land near Blind Slough, officially named Knappa Slough in 1941. There was a post office in Knappa from 1872 to 1943. Knappa now shares the Astoria zip code, 97103.

Wauna is an unincorporated area about ten miles east of Knappa that is home to one of Clatsop County’s largest employers, Georgia-Pacific’s Wauna paper mill. The Wauna mill employs about 750, and recently entered a Strategic Investment Program agreement for approximately $152 million in improvements.

Westport is located at the eastern border of Clatsop and Columbia Counties on Highway 30. Westport is named after John West, a Scotsman who settled in the area in the early 1850s and ran a sawmill and a salmon cannery. Westport is home to the Wahkiakum County ferry, connecting across the Columbia River to Puget Island and Cathlamet, Washington.

Knappa School District

41535 Old Hwy 30, Astoria, OR 97103-8640 503-458-5993 • www.knappa.k12.or.us

Knappa High School

Grades 9-12

41535 Old Hwy 30, Astoria, OR 97103-8640 503-458-5993

Hilda Lahti Elementary

Grades K-8

41535 Old Hwy 30, Astoria, OR 97103-8640 503-458-5993

Knappa Pre-Kindergarten Program

41535 Old Hwy 30, Astoria, OR 97103-8640 503-458-5993

Knappa Virtual Academy https://lahtiknappaor.schoolinsites.com/dlh

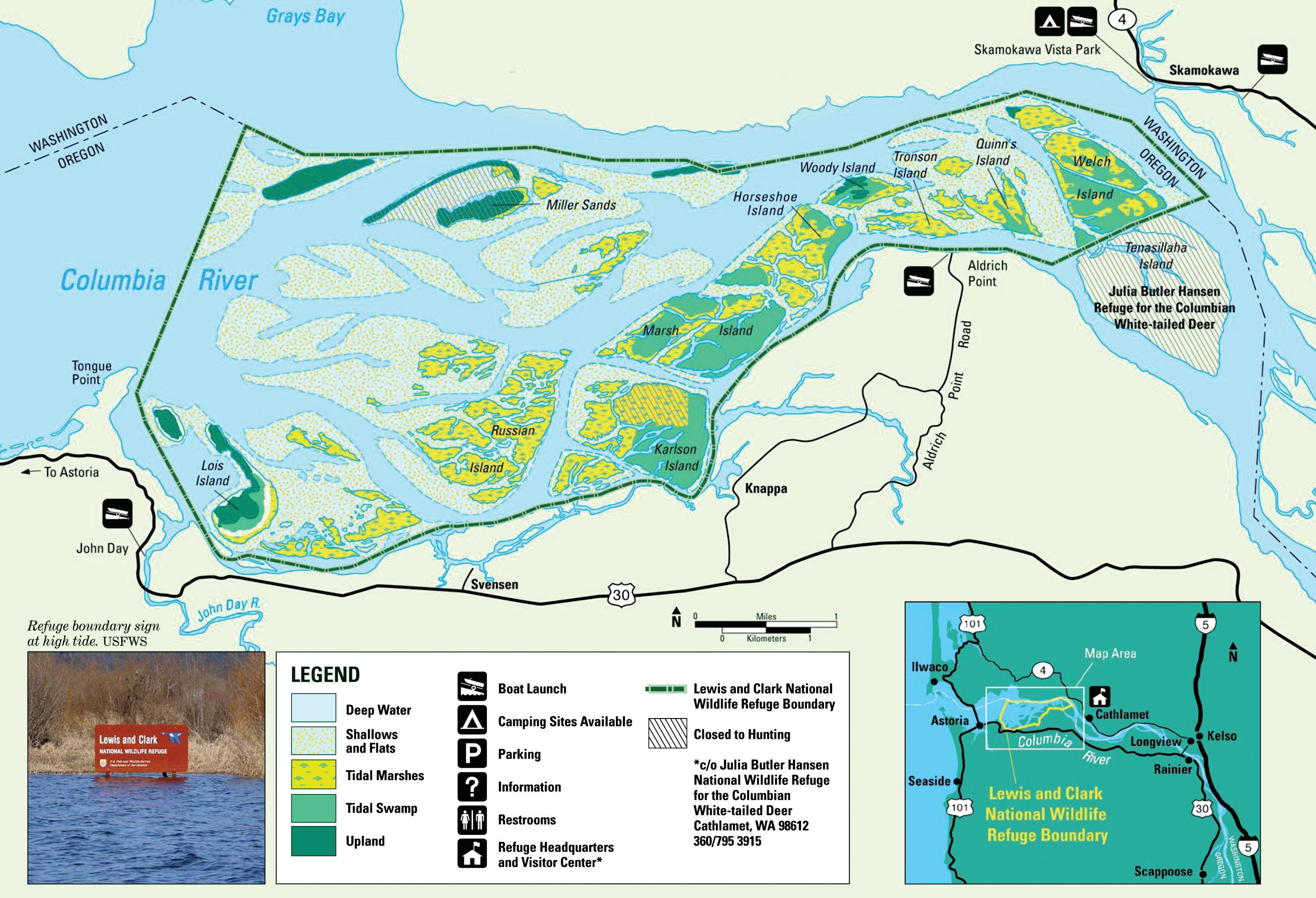

Extending from Tongue Point to Cathlamet, Lewis and Clark National Wildlife Refuge includes approximately 20 islands stretching over 27 miles of the Columbia River. Established in 1972 to preserve the vital fish and wildlife habitat of the Columbia River estuary, the refuge is only accessible by boat, and supports large numbers of waterfowl, shorebirds and raptors.

Jewell, an unincorporated community, is located in the center of Clatsop County near the intersection of Highways 202 and 103. Jewell was named after Marshall Jewell, United States Postmaster General from 1874-1876. A post office was established in Jewell in 1874 and closed in 1967. Jewell now shares the Seaside zip code, 97138.

Jewell Meadows Wildlife Area, an Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife preserve, is known for its resident Roosevelt elk. The Jewell area of central Clatsop County is home to Clatsop State Forest, the center of logging activity in the county.

Jewell School District - Jewell Elementary School, Jewell Middle School, Jewell High School

1A, Blue Jays-• Grades PK-12 • 83874 Hwy 103, Seaside, OR 97138-6154 • 503-755-2451 • Jewell.k12.or.us

Named after a homesteader from the Jewell area, Lee Wooden/ Fishhawk Falls Park is a 47-acre day-use park located five miles west of Jewell on Hwy 202 at milepost 25. The Clatsop County-owned park features picnic tables and a maintained trail from the informal parking area to the base of Fishhawk Falls.

Astoria Column

1 Coxcomb Drive

The Astoria Column is a 125-foot tower on Coxcomb Hill in Astoria, Oregon, offering panoramic views of the city, the Columbia River, and the Pacific Ocean. A spiraling mural on its exterior depicts key events in Oregon's early history.

• Family Dentistry from Children to Adults

• Cosmetic Dentistry

• Sedation Dentistry

• Orthodontics

• Root Canals

• Implants

• Oral Surgery

• Third Party Financing Available

All Clatsop County residents are required by law to license their dogs annually. An aluminum license tag attached to your dog’s collar can help identify your pet to be returned home safely. A license is required even when the dog is always indoors or on a farm. When the dog is not on the owner’s premises, it is required to wear a license tag. Residents of Seaside and Gearhart are required to license their dogs through their local police departments. There is no licensing required for cats or other types of domestic animals.

All dogs must be licensed at:

• 6 months of age, or

• When they have permanent canine teeth, or

• Within 30 days of acquisition, or

• Within 60 days after new residents move into Clatsop County.

• A license is required even when the dog is always indoors or on a farm.

What documents will I need?

• A current rabies inoculation certificate.

• For altered dogs, the spay or neuter certificate or a written statement from your veterinarian.

Where can I get a license?

Licenses can be purchased or renewed in person or through the mail at the Animal Shelter by using the form online at www.co.clatsop.or.us/animalcontrol/ page/dog-license-application

Licenses are also available at these vendors:

• Bayshore Animal Hospital

• Safe Harbor Animal Hospital

• Seaside Pet Clinic

• Cannon Beach City Hall

• Clatsop County Assessment and Taxation Department

• Clatsop County Clerk’s Office

Questions about licensing.

Animal Control and Shelter 1315 S.E. 19th St., Warrenton, OR 97146 503-861-7387 Main * 503-325-2061 Emergency

Clatsop Animal Assistance

Needs volunteers who have a strong commitment to work on behalf of the Clatsop County Animal Shelter’s dogs and cats. For information, email info@ dogsncats.org or call 503-298-5386 • dogsncats.org

Clatsop County Animal Shelter

Animal care volunteers age 16 and older needed for one 3-hour shift per week. Pick up an application at 1315 S.E. 19th St., Warrenton. For information, or to schedule orientation, call 503-861-7387

Angels for Sara Senior Dog Sanctuary

Needs volunteers to help care for elderly dogs who are unable to stay with their owners. Anyone interested in fundraising, yard maintenance, spending quality time with the dogs or fostering a senior dog, short or long term, email angelsforsara@gmail.com or call 503-325-2772.