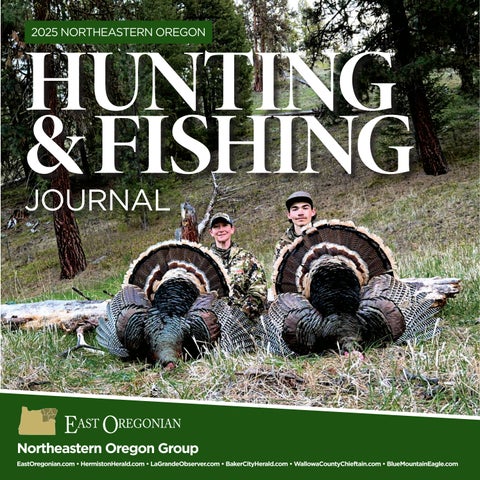

HUNTING & FISHING

Forrest Legacy Ranch in Monument ~ 1800 Acres

From the field to your future, Duke Warner Realty helps you bag the perfect property.

SMALL TOWN LIVE/WORK OPPORTUNITY IN DAYVILLE!

Endless Possibilities, See To Appreciate, 2 Story, 3428 sq ft Building.

$289,000

BEAUTIFUL SETTING ON

1.58 ACRES!

Mt Views, 4/4 Home w/Basement, Garden, Garage.

$399,900

BEAUTIFUL CUSTOM HOME ON 15 ACRES W/STUNNING

PANORAMIC MT & VALLEY VIEWS!

2 Story, Vaulted Open Concept Living, 3/3, Landscaped, Patio, Garage, Fish Pond, Orchard, Barn. $585,000

COZY DAYVILLE HOME W/COUNTRY CHARM!

1550 sq ft, Primary & Guest Bedrooms, Patio, Detached Garage/Workshop.

$226,500

2 ACRES CLOSE TO CANYON CITY! Views, Cement Slab Wired For Radiant Heat, Close To City Sewer.

$87,000

615 REMOTE ACRES W/MT & VALLEY VIEWS!

4 Tax lots, LOP Tag Eligible, Fenced, Spring, Yr Rd Creek, Cabin, Outdoor Shower, Out House.

$584,000

ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES TO REPURPOSE & REVITALIZE THIS LARGE COMMERCIAL BUILDING!

7147 sq ft Plenty Of Parking.

$345,000

BUILDABLE CITY LOT IN LONG CREEK!

Great Base Camp In An Excellent Hunting & Recreational Area.

$50,000

THRIVING TURN KEY BUSINESS IN SENECA, OREGON! Bear Valley Store, All-Inclusive Includes Real Estate, Business, Inventory & Operating Equipment.

$450,000

NICE HOME ON 7+ ACRES! Located Near The John Day Golf Course, 1600 sq ft Home, Open Concept, 3 Bedroom, 2 Bath, Fenced, Animal Shelters, Shop.

$395,000

CHARMING 2 STORY HOME IN JOHN DAY ON LARGE LOT!

Mt Views, 1928 sq ft, 3 Bedroom, 2 Bath, Patio, Landscaped, Garage, Room For Boat or RV.

$279,000

Stock up for Hunting Season

Stock

Stock

Archery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies SuppliesArchery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies SuppliesArchery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies SuppliesArchery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies SuppliesArchery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies SuppliesArchery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies ASupplies rchery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies SuppliesArchery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies SuppliesArchery ASupplies rchery Archery Supplies Supplies for H u n t i n g S e a s o n H u n t i n g Hunting S e a s o n Season

Stock Up

Stock

Stock Up

Stock Up

Stock

Stock Up

for

n t in g S

a s o n Hu n t in g Hunting S e a s o n Season

for H u n t i n g S e a s o n H u n t i n g Hunting S e a s o n Season

Guns Knives Bullets Arrows Powders •Tools • Clothing •Tents

•Sleeping Bags

Guns Knives Bullets Arrows Powders •Tools • Clothing •Tents •Sleeping Bags •Components

Advertiser Index

HUNTING & FISHING

Eastern Oregon has lots of opportunities for outdoor recreation, and hunting and fishing are among the most popular. And no wonder — Northeastern Oregon has many big game units, offering sport for bow, rifle and shotgun hunters, as well as an abundance of rivers and streams, lakes and reservoirs.

Bacteria affects bighorn sheep

Outbreak

imperils

2

Baker County herds. 5½ years after infection confirmed, the bacteria continues to decimate lambs

By JAYSON JACOBY | Baker City Herald

Brian Ratliff ’s elusive quarry is the bighorn sheep version of Typhoid Mary.

Possibly more than one.

Regardless of the number, identifying the sheep harboring a strain of bacteria could save Baker County’s largest bighorn herd from an eventual demise.

The county’s other, much smaller, herd might be beyond rescue, Ratliff said.

“We’re still fighting the outbreak,” he said on Aug. 14.

Ratliff is the district wildlife biologist at the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Baker City office.

For the past 5 1/2 years, he and other biologists have been

studying an outbreak of bacterial infection in the herd of Rocky Mountain bighorns in the Lookout Mountain unit in far eastern Baker County, as well as the California bighorn herd in the Burnt River Canyon in the southern part of the county.

Lab tests in early 2020, from samples of dead bighorns found in the Lookout Mountain Unit near Brownlee Reservoir between Richland and Huntington, confirmed the sheep were infected with a strain of Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae bacteria not previously found in Oregon bighorns.

Later in 2020, biologists also confirmed the bacteria in bighorns in the Burnt River Canyon southwest of Durkee. The two herds, separated by Interstate 84, sometimes mingle.

The bacteria can cause fatal pneumonia.

Regardless of the number, identifying the sheep harboring a strain of bacteria could save Baker County’s largest bighorn herd from an eventual demise.

Bighorn sheep ewes and lambs in the Lookout Mountain Unit in eastern Baker County in June 2020. | Jayson Jacoby/Baker City Herald, File

Bighorns can contract a variety of bacteria and viruses from domestic livestock, including sheep, but there is no evidence the bacteria arrived through domestic animals.

Although bighorns are stout and sturdy animals, capable of nimbly navigating steep and rocky terrain, the animals are susceptible to a variety of bacteria and viruses that can rapidly spread through a herd by nose-to-nose contact, Ratliff said. Bighorns gather in large groups of ewes and lambs, which can exacerbate the effects of an infection.

The source of the bacteria remains unknown, and almost certainly never will be determined conclusively, Ratliff said.

Bighorns can contract a variety of bacteria and viruses from domestic livestock, including sheep, but there is no evidence the bacteria arrived through domestic animals.

Sheep from two domestic flocks near Richland, at the north end of the Lookout Mountain Unit, were tested in 2020 and none was carrying the Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae bacteria, Ratliff said. A llama owned by a resident along the Snake River Road was also tested, and was also negative for the bacteria.

Ratliff said it’s possible that a single bighorn that migrated into the area from Idaho or another state introduced the bacteria to the Baker County herds.

Sheep in the Burnt River Canyon began dying around October 2020, and Ratliff believes sheep from that herd crossed I-84 earlier in the year, mingled with infected Lookout Mountain bighorns and became ill, then returned and began spreading the bacteria among Burnt River Canyon sheep.

Prior to the disease outbreak, the Lookout Mountain herd numbered about 400 animals and was the biggest group of Rocky Mountain bighorns in Oregon.

Ratliff said the estimated population in the Lookout Mountain herd is about 250 now. He said the number has been relatively stable the past few years.

ODFW established the Lookout Mountain herd in the early 1990s when a few dozen bighorns were captured elsewhere and released along Fox Creek. The animals have thrived in the steep canyons on the breaks of the Snake River.

Sheep in the Burnt River Canyon are California bighorns, a different subspecies that are somewhat smaller than Rocky Mountain bighorns.

The herd is much smaller, too, typically running around 80 to 90 sheep prior to the disease.

ODFW reintroduced California bighorns to the Burnt River Canyon in 1987.

Ratliff said there are around 40 sheep in the canyon now.

Although bighorns are native to Oregon, they were largely extirpated due to overhunting in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Scott Quigley of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife takes blood and nasal swab samples from a bighorn sheep ewe near Brownlee Reservoir. The effort is part of ODFW’s work to eradicate a bacterial infection that has killed dozens of sheep in the Lookout Mountain Unit since 2020. | Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife/Contributed Photo

Trying to save lambs, and searching for a ‘chronic shedder’

Over the past five years, ODFW has trapped 244 sheep in the Lookout Mountain unit and tested the animals’ blood and nasal swabs.

The blood tests detect antibodies that show whether, and approximately how recent, the sheep was exposed to the bacteria, Ratliff said.

The nasal swab determines whether the sheep is “shedding” bacteria, meaning it’s capable of infecting others.

Finding these chronic shedders is vital, Ratliff said, because those sheep — possibly only one in each herd — keep the bacteria circulating.

Although the shedders aren’t sick — they’re effectively immune after being exposed to the bacteria — they shed the bacteria, either constantly or intermittently.

The continuing presence of the bacteria in both herds threatens their long-term survival because it is killing most of the lambs born each spring, Ratliff said.

Adult bighorns, by contrast, all of which almost certainly have been exposed to the bacteria, aren’t dying from it any longer. Biologists estimated that 75 adult bighorns in the Lookout Mountain herd died from pneumonia in 2020, but surveys in the past few years haven’t turned up any adult sheep that likely died due to the bacteria.

The situation is dramatically different, though, for lambs in both herds. »

Ratliff said biologists don’t think any Lookout Mountain lambs born in 2020 or 2021 survived as long as a year. ODFW counted five lambs as surviving from the 2022 crop, and six from 2023 and 2024.

Prior to the bacteria outbreak, the herd typically produced about 70 surviving lambs per year, Ratliff said. Few if any lambs from the Burnt River herd have survived over the past five years.

Because adults aren’t being affected by the bacteria, they have continued to breed at relatively typical rates, Ratliff said. But the lambs, which haven’t been exposed to the bacteria and aren’t protected by their mothers, have been decimated each year since 2020.

The lamb survival rates from 2022 and 2023 are far too low to sustain either herd in the long term, he said, with Burnt River, due to its much smaller population, being at more imminent risk of dying off.

Ewes as old as 16 or so can sometimes bear a lamb, but their chances of giving birth decline once they reach age 10 or so, Ratliff said.

The continuing high death rates among lambs shows

that at least one sheep in each herd is shedding the virus, he said.

ODFW’s goal, in trapping and testing bighorns, is to find chronic shedders, which will be killed.

The agency killed one chronic shedder from the Lookout Mountain unit and six from the Burnt River Canyon herd, in 2022 and 2023.

But the search for shedders the past two years has been fruitless so far.

Ratliff said the evidence points to most, if not all, of the shedders being ewes rather than rams.

The reason, he said, is that rams spend most of the year in groups with other rams. They don’t mingle with lambs, or with ewes except during the breeding season in the late fall.

If rams were the main sources of bacteria, then lamb survival should be higher because lambs have little if any contact with rams, Ratliff said.

But given the failure to find chronic shedders among ewes, he said ODFW is trying to trap and test more rams — to determine whether the sought-after Typhoid Mary

actually is male.

It’s possible that the chronic shedders will die naturally, rather than after being trapped and tested.

If that happens, Ratliff said biologists likely would find out not by finding a carcass, but when one year’s crop of lambs has a much higher survival rate.

Hunting remains closed

ODFW hasn’t sold hunting tags for either bighorn herd since the outbreak started.

Previously the agency issued three tags per year for Lookout Mountain, and one for the Burnt River Canyon. Ratliff said ODFW officials don’t intend to resume hunting in either area until they’ve confirmed the bacterial outbreak is over.

Scott Quigley of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife takes blood and nasal swab samples from a bighorn sheep ewe near Brownlee Reservoir. The effort is part of ODFW’s work to eradicate a bacterial infection that has killed dozens of sheep in the Lookout Mountain Unit since 2020.

A herd of bighorn sheep rams in the Lookout Mountain Unit in eastern Baker County in June 2020. | Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife/Contributed Photo

Lone Elk Market

377.25 Acres with historic homestead, year around creek, 4-developed springs, state hwy access, cabin is 1 bed, 1 bath, off-grid, spring fed cister, DEQ approved septic, LOP Tags. HWY 395 N, Mt. Vernon, OR $789,000

43.45 Acres, 1991 MH, 3 bed, 2 bath, 28`x40` shop w/220 power, 32`x52` barn, 24`x40` hobby room, 16`x32` hay storage, fenced and cross fenced, views, 27764 Picnic Creek Rd, Mt. Vernon, OR $489,000

80.06 Acres, off-grid, 2006 home, 2,940 sq ft, 4 bed, 3 bath, 1,728 sq ft shop w/apartment, look out, 5,000 gal cistern for well water, diesel generator, solar panels, batteries. 31367 Clarks Creek Rd, Mt. Vernon, OR $810,000

1956

2.52 Acres, 2 tax lots,

stick built daylight basement, 4 bed, 2 bath, 2,773 sq ft, 52`x32` fully insulated shop, concrete floor, 220 power, hydraulic lift. 204 Adam Drive, Canyon City, OR $379,000

Sage Browning 5-point elk

Colton Phelps 4-point elk

Taran Ough 3-point mule deer

Payden Phelps Cow elk

Make sure your animals are prepared this hunting season. Bass Fishing Supplies & Trail Cameras

Checkout our great selection of quality feeds including Payback, Equis Horse Feed & Wholesome, Nutrena Dog Food.

Gibco AG & industriAl

312 N Canyon City Blvd., Canyon City • 541-575-2050 Open Mon-Sat 9am-6pm, closed Sun.

Jesse Madden of Grant County pulls his giant bull elk by the antlers during his hunt on Mt. Emily.

Contributed photo

Dad’s Mt. Emily elk hunt

An epic search for a giant bull that was 25 years in the making

By Jesse Madden | Contributed story

Istarted putting in for this tag in my 30s when I switched from rifle hunting elk to archery hunting elk. I’ve had a passion for elk hunting since my early teens when I would get an elk tag just so I could feed our family for the year.

Once I switched to archery hunting it was an over the counter tag, which made it so I could hunt elk with my bow every year and still get a point saver for elk. I killed many bulls through those 25 years and had countless opportunities on giants but just never could quite seal the deal on any of those giant bulls.

That’s what kept me wanting to get back out there looking for the biggest bulls our woods hold.

In early March of 2024, I put in for my tags for the Oregon draw and that’s when I decided to switch back from archery to rifle for my limited entry Oregon elk hunt. I hadn’t rifle hunted elk in many years but wanted a better chance at a giant bull in some of the biggest and nastiest country Oregon has to offer.

As the year progressed my family had many other hunts, brother and I drew New Mexico archery elk, which was a very fun experience but I ended up walking away from that hunt with a tag still in my pocket and it was getting close to time for the hunt I’ve always dreamed about. We headed down for the hunt three days before the season so we could do a little scouting and learning the land since we’d never been in that area before.

The first day of scouting was a little rough and not very productive. We were dealing with nasty weather and not seeing many bulls around.

The second day of scouting was a little more successful and we started really learning the land and figuring out what areas the bulls liked and the areas we needed to focus our attention on. We still didn’t have any target bulls on our mind for opening day and the days were running out before the hunt.

The evening before our hunt started, my son and one of his good buddies who were helping on the hunt made their way into a new spot to glass for the night. Right away they spotted a few good bulls but nothing in the next level class until my son spotted this bull.

The bull was bedded on the top of a finger ridge running into a huge canyon but was in a great spot for a stalk the next day if he stayed in the area. They watched him for hours and he was with a group that had six other good bulls and a few rag horns in it.

It was about 30 minutes before dark when the bull got in a fight with one of the rag horns and for some reason, it just left the whole group and headed to the top of the hill into the thick dark timber afterward. We didn’t really know what to do because that messed up the whole plan for the morning but we figured we’d still give it our best go with the same plan we had to kill that bull.

Opening morning came around and we headed out very early to move into our spot. My son and two of his buddies posted up on the other side of the canyon back in the same spot they glassed from the night before. One of my good friends and I started our hike into the canyon we hoped the bull would be in.

After hours of trying to locate the bull, it just wasn’t happening. We had found many other 330 class bulls, just not the bull we were hoping for, so my son and his friends came over and hiked into the spot and we decided to post up and glass for the evening.

It was about 2 p.m. once they made it over to us. We had seen one giant bull way off in the distance in an unhunt-able spot for the night but only got a quick glimpse of him.

The remaining time we had that evening was spent trying to glass up that bull until we looked over on the ridge 600 yards to our left to see a small, six-point bull walk out. We shifted our attention onto that hill just to see what else could walk out.

Mind you, we are 2 miles as the crow flies from the last location where we saw the big bull from the night before. We had no thought that he would be over in this area.

We watched multiple other bulls walk out onto this hillside but all were small bulls except one that I could see in the bottom of the canyon. I didn’t have my spotting scope because my son was using it and they weren’t able to see the bull in the bottom.

At the time, I thought that was one of the bulls they said was just a small six-point. Hours passed and we were still watching those bulls when the one finally came out of the bottom and they started freaking out because that was him.

The whole time I was watching the bull we were going after and I had no clue it was him. My son got the spotter on him and he was heading for the top of the ridge — we had to make our move now.

I still didn’t have a good look at this bull so I just trusted that he was a good one and for sure a shooter.

The wind was ripping up the draw with gusts upward of 25 mph so we had to close the distance for a good shot. My son and I got down to 400 yards but the bull had made his way into some thick timber where we only could get little glimpses of him. We sat on him for about 30 minutes before we could get into position for a clear shot and we started trying to figure out the wind to make an ethical shot.

The bull was bedded down when I got into my scope. He was right at 400 yards, so I dialed my scope up and lined up for the shot. I slowly squeezed the trigger off but the bullet strayed about three feet to the left from a big gust of wind that blew through and I missed that bull.

“I killed many bulls through those 25 years and had countless opportunities on giants but just never could quite seal the deal on any of those giant bulls.”

He got up and made his way up the hill and I thought I had just blown the opportunity I’ve been waiting for all my life. The bull made his way into a small opening where I was able to get another shot off.

It was a little over 400 yards at this point but the wind had slowed down a little bit. I squeezed off the shot and my son said the elk had been hit. It was a moment of relief until he started saying it looked a little bit back, which it was.

I hit him in the liver and that’s when my heart started to stop. I was so worried because there was a huge storm blowing in and I had a wounded bull in this huge canyon.

The bull bedded up the hill and didn’t move for 30 minutes but we couldn’t see him at all, our buddies up the hill could barely see him and were communicating with us. After 30 minutes, the bull stood up and started coming back down the ridge and bedded again but we still had no shot. »

Squeeze-In

We moved down the hill and got a clear lane to the bull and I was able to put 2 shots right into his lungs. The bull took his last breaths within seconds after those shots.

That’s when it all started to sink in, I just filled my pretty much once in a lifetime elk tag and all the work was about to begin. We all made our way over to the bull and walking up on him he grew on us a lot.

He had so much mass that was covering up the length he had on his tines. We got plenty of pictures but the work had to start.

We spent 2 hours trying to get this bull quarter up on this super steep hill. We had to tie a rope around a tree and onto his antlers just to keep him from sliding to the bottom of the canyon.

By the time we got him all quartered up it had started snowing pretty hard on us and we knew it was going to be a brutal hike out. We only had about 2.5 miles out but it was all uphill with packs well over 100 pounds and very slick ground from the fresh snow.

We had started hiking at around 8 p.m. and it was brutal. We had wind blowing the snow into our eyes the whole way out and none of us brought much foot for the day so we were all running on very little calories. Our bodies were getting pushed to their max but after 4 hours of hiking, we had finally made it out of there and started loading up the bull.

At this point there was about eight inches of snow on the ground and we still had a two hour drive back to camp.

We made it back and all the hard work had paid off. The next morning it all started to set in.

I just killed the biggest bull of my life and I was able to do it on the first day of the hunt. My son started getting a tape put on the bull and he came back into the camper with a huge smile on his face.

I asked him what he scored and he started having me guess. I was nowhere close to the true score.

When my son told me 351, I was in shock and blessed to have just killed a bull over 350, that was my whole dream.

I was hoping for a 340+ bull on this hunt and we just made it happen on the very first day. We packed up camp that day and headed home with a beautiful bull in the back of the truck and enough meat to feed us for the next year.

Jesse Madden poses with giant bull elk on Mt. Emily in Union County. | Contributed photo

Blake and Tom Sandor

5-point elk

Blake Sandor 4-point mule deer

Blake Sandor Wild turkey

Once in a lifetime hunt

Sam Palmer leaves Africa with zebra hide, memories and

stories to tell

By JUSTIN DAVIS | Blue Mountain Eagle

Achange in plans on an African hunting excursion left Sam Palmer with a beautiful zebra hide after one of his most challenging hunts to date.

Palmer’s trip to Africa also came following a change in plans. After expressing a desire to hunt a moose, Palmer was advised that a hunt in Africa would be cheaper and allow him to hunt an assortment of game as opposed to a single moose.

A cancellation on the HECS crew making the trip to Africa provided Palmer with the opportunity to participate in the hunt.

The excursion gave hunters the option to choose five animals out of a list of 15 to hunt during their time in Africa. Palmer said those selections are not set in stone as hunters can opt to change the animals they hunt on the trip.

After bagging his two large animals, Palmer opted to hunt a zebra both for the challenge and to share the meat with local villagers.

“I really didn’t have an interest in shooting a zebra until I got there,” Palmer said.

The zebra wasn’t the most dangerous animal Palmer hunted in Africa but it was the most challenging. As prey animals, zebra are used to being hunted by just about every predator on the African savannah, making them extremely nervous and skittish.

Palmer’s first two attempts at stalking a zebra ended with the animals taking flight just as soon as the hunt had started.

“My first two stalks I tried to make — I barely made a couple of steps and they pegged me and were gone,” Palmer said.

Palmer was told by hunting guides that he would not get within 60 yards of a zebra given the animal’s skittishness. Assisted by HECS technology, Palmer was able to get as close as 42 yards before ultimately taking the 1,400-pound zebra with a bow and arrow.

The zebra hide will ultimately be fashioned into a rug after being sent to a South African taxidermist. The hunt was filmed for television and may appear on the Pursuit Channel on satellite TV.

Palmer and those who went with him on the hunt were assisted by professional hunters from Africa who major in college for the profession. Palmer said the professional hunters or PHs are educated in all of the animals that can be hunted and on the proper trophy size for each animal.

The PHs also carry big guns in the event hunters run into predators or large game like Cape buffalo.

“They are amazing at helping you track an animal if you wound it,” Palmer said.

That tracking skill is paramount in Africa because you pay for the hunt as soon as you draw blood.

“When you’re bow hunting here and you think, ‘I may lose a $15 or $20 arrow — over there if you draw blood you buy the animal,” he said. “You could be shooting a $5000 arrow.”

A close-up of Sam Palmer with the zebra he took in Africa on July 23, 2025. | Blue Mountain Eagle/Photo contributed by Sam Palmer

Palmer did not need the tracking skills of the PHs on his zebra hunt as the animal traveled less than 100 yards before succumbing to Palmer’s arrow. Palmer did sample some zebra meat prior to it being dispersed among the locals, calling it a sweet meat and comparing it to pronghorn antelope.

The zebra hide will ultimately be fashioned into a rug after being sent to a South African taxidermist. The hunt was filmed for television and may appear on the Pursuit Channel on satellite TV.

Palmer said he had a great and memorable hunt and overall.

“All the meat went to the villages, I got a beautiful hide and I had a wonderful hunt,” he said.

The zebra wasn’t the most dangerous animal Palmer hunted in Africa but it was the most challenging. As prey animals, zebra are used to being hunted by just about every predator on the African savannah, making them extremely nervous and skittish.

Sam Palmer with his 1,400-pound zebra during an African hunting excursion in 2025. | Blue Mountain Eagle/Photo contributed by Sam Palmer

Jena Knowles King Salmon in Ketchikan Alaska

Chaney Knowles, 5 Bass in Mt. Vernon

Trevor Knowles King Salmon in Ketchikan Alaska

6-year-old angler lands a rare trophy

Grayson Horn of Cove caught a 6-pound tiger muskie at Phillips Reservoir near Baker City

By JAYSON JACOBY | Baker City Herald

Grayson Horn had secured a promise for ice cream, no small matter for a 6-year-old, but he had to cast the rubber worm just once more into Phillips Reservoir.

His choice yielded a memory sure to outlast even the sweetest of frigid treats.

Besides which, Grayson ended up with two ice creams.

More about that later.

Horn, who lives in Cove, was fishing with his dad, Sterling, on the afternoon of July 30.

It was hot that day, the temperature in the 90s.

After six hours on the reservoir, about 17 miles southwest of Baker City, and having caught just a pair of 6-inch smallmouth bass, father and son were ready to stalk less persnickety prey in an ice-fringed cooler.

“It was a terrible day of fishing,” Sterling said on Monday, Aug. 4.

And then it was the opposite.

Grayson readily agreed to the ice cream plan.

But he insisted on making a last cast.

Grayson recently graduated from his Minecraft-themed kids pole to a full-sized rod, and he takes angling seriously.

“He’s been in it to win it,” Sterling said with a chuckle.

Sterling suggested his son cast toward a rock near the reservoir’s north shore.

But the bail didn’t click shut and the result was a snarl of monofilament.

That seemed to Sterling an ideal reason to store the gear for the day.

Grayson disagreed.

He had negotiated one last cast, and he was determined to have it.

“He told me to turn the boat around” so he could toss the purple Senko worm toward the rock his dad had pointed to.

This cast — the actual last cast — flew true.

Then Grayson hollered.

“Dad, I’ve got a big fish.”

Grayson Horn, 6, of Cove, landed this trophy tiger muskie, weighing about 6 pounds, on July 30, 2025, in Phillips Reservoir near Baker City. | Contributed Photo

Sterling, on seeing

“No you don’t,” he told his son. “You’ve snagged on the bottom.”

Then Sterling took the pole from his son’s hands. A snagged hook doesn’t vibrate that way.

Grayson was right.

The fish, as yet unseen, started peeling line, making the reel spin like a top.

Then the fish leaped, droplets twinkling against the blue summer sky.

Sterling netted the fish.

He doubted at first what he knew he was seeing.

The slender fish, more than 2 feet long with distinct vertical stripes and dagger-like teeth, was a tiger muskie.

Sterling knew there were tiger muskies in Phillips.

But he couldn’t conceive that his son had just hooked a big muskie on a worm that’s supposed to entice a smallmouth bass.

“About the dumbest thing you could throw out for a tiger muskie,” Sterling said.

He took several photographs of Grayson holding the trophy, which was not a whole lot shorter than the angler.

Sterling was trying to weigh the muskie when it slithered away, taking the $40 scale into the depths.

Not that he minded.

He said he would gladly trade any scale for his son’s smile.

(Anyway, fishing for tiger muskies is catch and release only, so as to allow the fish to maximize their perch consumption.)

Sterling said the scale, when it briefly settled between the muskie’s thrashings, was reading between 5 and 6 pounds.

An experienced bass angler, he said that seemed about right for the fish as he hefted it in the net.

Grayson, meanwhile, was engaging in one of the angler’s favorite pastimes.

Gloating.

“He kept saying, ‘I told you, Dad, one more cast.’”

Sterling said that during the tussle with the muskie, another angler drifted past in his boat. The fisherman told Sterling he was from the upper Midwest, where the lakes hold big fish such as pike and muskies. The angler told Sterling that he knows people who have fished for decades and never hooked a trophy to match Grayson’s.

Grayson wasn’t quite finished leveraging his catch.

“I think I deserve two ice creams, Dad,” he said.

He got them.

A fish biologist’s reaction

Ethan Brandt wasn’t surprised to hear that Grayson caught a tiger muskie.

But Brandt was shocked at the fish’s size. Brandt is the district fish biologist at the Oregon

BEAR VALLEY STORE

Open Mon-Sat 5:30am - 7pm Sunday 8 am - 5 pm

Department of Fish and Wildlife’s regional office in La Grande.

Last spring, Brandt oversaw the start of a campaign designed to pare the population of yellow perch in the 2,235-acre reservoir. Since someone illegally released perch in Phillips more than 30 years ago — the culprit remains unknown — their prodigious procreation has allowed perch to replace hatchery rainbow trout as the reservoir’s predominant game fish.

Sterling Horn knew there were tiger muskies in Phillips Reservoir, but he couldn’t conceive that his son had just hooked a big one.

Perch have outcompeted trout for food, Brandt said. With so many fish competing for limited nutrients, the average size of perch is relatively small, with many adult fish 6 inches or less, he said. Reducing the perch population likely would boost the average size, something anglers should appreciate, he said. »

ODFW still stocks thousands of hatchery rainbows in the reservoir each year, but far fewer than before the perch predominated.

The number of angler visits at the reservoir has dropped by about 90% compared to the pre-perch period.

Because ODFW isn’t proposing to poison the reservoir — the only method that could conceivably eliminate perch, Brandt said — the goal instead is to restore a species balance that yields better opportunities for anglers, whether they prefer to hook perch or trout.

ODFW officials picked tiger muskies, a hybrid of the northern pike and the muskie, as a potential, albeit partial, solution, more than a decade ago. Biologists figured tiger muskies, which are sterile, might live long enough that their voracious appetite for other fish — including perch — would result in fewer, but bigger, perch, while also helping trout to grow faster.

Starting in 2013, and continuing for the next four years, the agency dumped 53,000 juvenile tiger muskies in the reservoir.

But the experiment didn’t help much, Brandt said.

Many of the fish, which were about 5 inches long when released, were eaten by birds, Brandt said.

He said diving birds including terns, loons and mergansers, along with ospreys and other raptors, all feed on fish.

“These stockings were discontinued when it became clear that few of the fish were surviving,” according to an ODFW press release.

Brandt said some of the juvenile tiger muskies had radio trackers attached to a fin. More than half were eaten within a week or so, he said.

The 70,000 tiger muskies released on April 23, 2024, by contrast, were much smaller. About 10,000 of the 70,000 were around an inch and a half long, with the rest just three-quarters of an inch or so.

Although larger fish, as well as birds, no doubt gobbled some of the minuscule tiger muskies, Brandt said, ODFW tried to give the baby fish a boost by distributing them throughout the reservoir, but focusing on shoreline areas where copious grass should give the fish places to hide from predators.

“We are hoping to overcome the survival bottleneck we have observed in the past and that these fish will be smarter at staying away from the surface of the water where birds can pick them off,” Brandt said in 2024.

The fish were raised in a hatchery operated by the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, which gave Oregon the fish for free.

Brandt said Utah has successfully stocked tiger muskie larvae in reservoirs in that state to control populations of other species. Tiger muskie survival rates were as high as 10% in some reservoirs, he said — far above the goal he has for Phillips.

Brandt said ODFW workers will survey the reservoir this year and in the future, including netting fish and stunning them with pulses of electricity, so they have a better sense of the distribution of species.

The tiger muskie Grayson caught on July 30 must have been one of the 70,000 fish released 15 months earlier, Brandt said on Monday, Aug. 4.

Any muskies surviving from the 2013-17 stocking would be bigger, he said.

Brandt said he didn’t think the tiny tiger muskies dumped into the reservoir last April could have grown so rapidly, to put on 23 inches or so in less than a year and a half.

Grayson’s trophy wasn’t the first indication, though, that the tiger muskies were thriving in Phillips.

During a survey in the reservoir on July 30, 2024 — coincidentally, exactly a year before Grayson’s milestone last cast — Brandt netted two tiger muskies that were nearly a foot long. That meant they had grown by 10 inches or so in just three months.

“That seems like an unusual growth rate,” he said in August 2024. “They looked healthy.”

The future for tiger muskies

Brandt had hoped to release thousands more tiny tiger muskies in Phillips this spring, but a problem with a Utah hatchery prevented that.

He’s optimistic that Utah will be able to donate more muskies in 2026, however.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife released tiger muskies, a sterile hybrid, in Phillips Reservoir to try to control the population of yellow perch, which were illegally dumped into the reservoir more than 30 years ago. | Jayson Jacoby/Baker City Herald

Mountain goat hunters

Couple both drew tags to hunt mountain goats in the Elkhorn Mountains in October 2025

By JAYSON JACOBY | Baker City Herald

Milo and Joy Kind beat odds that would make a dedicated lottery player shudder.

But their reward isn’t cash.

If all goes well, the couple, who live in the Coast Range foothills north of Banks, in Washington County west of Hillsboro, will return from an October hunt in some of Baker County’s most torturous terrain with a pair of mountain goats.

The Kinds, who have been married for 23 years, have about a century’s worth of big game hunting between them.

But Milo, who’s 75, and Joy, 65, could never have imagined what happened when they applied for a tag to hunt goats in the Elkhorn Mountains, which form the precipitous, 5,000-foot-high wall west of Baker City.

Indeed, two months after they checked their tag results, the Kinds can scarcely believe what they saw on their computer screen.

To draw a single mountain goat tag in Oregon is nearly miraculous.

No other hunt is as hard to secure in the state.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife issued just 23 for this year’s hunts. Most are in Eastern Oregon, where the majority of the population of the nimble, cliffdwelling animals live.

Brian Ratliff, district wildlife biologist at the agency’s Baker City office, said he’s never heard of two people who know each other both drawing a tag for the same mountain goat hunt — much less a married couple.

And hunters can be lucky only once — ODFW limits people to a single mountain goat tag.

The Kinds aren’t exempt from that edict.

But the computer that decides who gets tags created an unprecedented loophole.

On the June day when ODFW unveiled tag results, Milo was working in the couple’s garden.

Joy checked her results online.

She was shocked, and delighted, to see that, in addition to a deer tag for the Beulah Unit in Malheur County, she had bucked the odds and garnered a mountain goat tag for the October hunt in the Elkhorns.

Joy stood and started for the garden, eager to tell Milo, sure he would be equally amazed.

But then she went back to the computer.

“I figured I would check his tags,” Joy said. A couple clicks and there it was.

Milo’s results were identical to hers.

Joy remembers her reaction.

“Unbelievable.”

Milo and Joy Kind, who live near North Plains west of Hillsboro with some of the many animal trophies in their home. | Contributed Photo

She made sure she was looking at Milo’s ODFW account, thinking she must have mistakenly opened her own.

But it was his name on the screen, not hers.

She ran to the garden.

Milo didn’t believe his wife.

“I said, ‘you made a mistake,’” he recalls. “That never happens.”

After Joy showed Milo the results, he had to concede that she appeared to be right.

So they showed their son.

He was incredulous.

“That’s impossible,” he said.

Except it was true.

The couple confirmed the results with ODFW. They bought some lottery tickets, too.

But their luck, apparently, had been expended.

Preparing for a once-in-a-lifetime hunt

The incredible coincidence has dominated conversations at the Kinds’ home this summer.

“We’ve been obsessed with it,” Joy said.

For perspective, about 1,800 people applied for one of the three tags for the Oct. 1-31 goat hunt in the Elkhorns. The Kinds claimed two of the three tags.

Both are longtime hunters.

Milo said he started hunting more than six decades ago, when he was 14.

He has applied for mountain goat tags for most of that time. Oregon sold tags for hunts in the Wallowas in the 1960s and early 1970s. Hunts in the Elkhorns started in the 1990s, after ODFW released goats along Pine Creek from 1983 to 1986. More than 200 goats live in the Elkhorns now.

Milo said he applied for a goat tag more out of habit than from any expectation that he would ever draw one.

“I had kind of given up,” he said. He said he debated this year whether to apply, since he wasn’t sure, at 75, that he could negotiate the steep terrain where goats live.

“I didn’t want to take that hunt away from somebody else,” he said.

But he’s confident that he’s ready for the physical challenge the Elkhorns present.

“I’m still getting around OK,” he said on Wednesday, Aug. 13.

The couple has hunted primarily in the Cascades and the Coast Range.

“We know absolutely nothing about the Elkhorns,” Joy said.

But they’ve learned quite a bit about the mountains since June.

Joy said she has talked with hunters who have killed a goat in the Elkhorns in past years.

Earlier this month she stopped in Baker City while driving to Idaho to visit her stepmother. She talked with officials from ODFW, the BLM and the Forest Service to gain insight into the Elkhorn goat herd.

The Kinds plan to make a scouting trip in late September, and to start hunting when the season opens Oct. 1.

Although hunters have a tiny chance to draw a goat tag, those fortunate few have a very high success rate. The animals, given the light hunting pressure, aren’t terribly difficult to find. And since they live primarily at or above timberline, there’s rarely a lot of trees to interfere with shooting lanes.

With two tags to fill, the matter of who shoots first is “still in negotiations,” Joy said with a laugh.

She thinks Milo should have priority because he’s been hunting longer.

“I’ve only been hunting for 25 years,” she said.

But Milo advocates on Joy’s behalf.

Ultimately, he said, who gets a chance to get a goat depends on the circumstances.

A group effort

The couple will have ample help during their hunt.

Both are lifetime members of the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, an organization that

advocates for bighorn sheep populations as well as mountain goats.

Milo and Joy said four members of the group have offered to accompany them on their hunt.

Several relatives also plan to go along.

The couple are optimistic that they’ll both leave Baker County with a fine billy goat.

Milo said they applied for the later hunt — there are two other Elkhorn hunts, one spanning all of September, the other all of August — because the goats will have a thicker coat of hair by October.

The animals, unlike other big game such as deer and elk, generally don’t migrate to lower elevations during the long and harsh winters in Northeastern Oregon.

Mountain goats survive in the polar conditions at and above 7,000 feet elevation by nibbling on vegetation that’s not buried under feet of snow thanks to the near constant winter winds.

The biggest challenge might be finding space in their home for the goats.

Milo and Joy said they would like to have a taxidermist mount the entire animals, rather than just heads or heads and shoulders.

But the couple already have 33 animal mounts, including elk, deer, bobcats, antelope, a cougar and a badger.

There’s also a potential species conflict — the couple’s deer tags are for the Oct. 4-15 season, overlapping with the goat hunt.

But there is no question of priority.

“Goats come first,” Milo said.

Ideally, he said, both he and Joy will get their goat in the first several days of October.

They would return home, then drive back to Eastern Oregon to try to fill their deer tags.

Regardless, the Kinds intend to take full advantage of an opportunity neither expected to ever have individually. That they will share the experience is, well, something akin to a winning lottery jackpot.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife issued just 23 for this year’s mountain goats hunts. Most are in Eastern Oregon, where the majority of the population of the nimble, cliff-dwelling animals live.

Michal, Jesse and Cash Madden

Michal’s Buck Larry Powell Bass from the John Day River

Riley Browning Buck

Jesse Madden Wild Turkeys