A supply chain expert explains how manufacturers might cope with the evolving U.S. tariffs.

A supply chain expert explains how manufacturers might cope with the evolving U.S. tariffs.

Four Minnesota companies show why all manufacturers should build lean into their cultures.

Building Design

` Renovations, Additions, New Construction

Site Improvements

Environmental Assessments We collaborate with manufacturers on . . .

` Parking, Circulation, Drainage

Facility Assessments

Space Planning

Mechanical, Electrical Upgrades

Structural Enhancements

To get an expert’s perspective on the challenges facing manufacturers in the Trump era of international trade, I scheduled a call with Harvard Business School Professor Willy Shih, a supply chain expert and longtime friend. We talked in late March. Then came April 2, “Liberation Day.” One week later, the administration announced a pause on all non-China tariff increases declared on Liberation Day. In May, tariff increases on Chinese imports were also delayed.

Each time I thought to call Willy for an update, another major change was announced. I started writing lists of issues to discuss, which were quickly obsolete. Willy and I did talk two more times, but before the Court of International Trade ruled the tariffs exceeded President Trump’s authority, a decision that is being appealed as this magazine heads to the printer.

As I review Willy’s comments now, I’m impressed that despite all the chaos, his insight is still timely and incredibly relevant. I urge you to read the full Q&A on page 16.

Willy shows how today’s current trade environment is radically different from the past several decades. “People have built their supply chains and their value-adding networks assuming there aren’t those tariffs and trade barriers. Now we’re going to put those barriers in. That’s a problem,” he says.

It’s a problem because manufacturers might not be able to get the inputs they need for production, and even if they do, costs will almost certainly rise.

Willy offers a road map to survive and thrive in this new climate. He urges manufacturers to take two steps: build strong supply chain relationships, and relentlessly pursue productivity gains, particularly through automation.

Manufacturers should be working with suppliers on scenario planning to address the current tariff and trade chaos, Willy says. They can share their expected needs for the coming months and match those with anticipated incoming supplies. To fill gaps, they can shift sources out of China or out of that region. Addressing these immediate needs in cooperation with their suppliers will fortify those relationships for the long term.

Shifting sources from low-cost countries to higher-cost countries will necessarily increase expenses. To minimize the impact on cost, manufacturers must boost productivity, particularly with automation, he says.

He urges manufacturers to automate the least desirable tasks, including heavy lifting and palletizing. He also says manufacturers need to upgrade skills across their organizations, focusing on employee talent development and process innovation.

No one can predict how the Trump-era trade story will end, or how and when the next global shock will hit, but we know there will be disruptions. One thing is certain in this time of uncertainty: Manufacturers who build strong relationships with suppliers and embrace efforts to boost productivity will be best positioned to weather future turmoil.

Publisher

Lynn K. Shelton

Editorial Director

Tom Mason

Creative Director

Scott Buchschacher

Managing Editor

Chip Tangen

Copy Editor

Catrin Wigfall

Writers

Suzy Frisch

Gail Hudson

Elizabeth Millard

Robb Murray

Kate Peterson

Mary Lahr Schier

Photographers

Amy Bogart

Annalise Braught Amy Jeanchaiyaphum

Robert Lodge

To subscribe or change an address ldapra@enterpriseminnesota.org

For back issues, additional magazines, and reprints ldapra@enterpriseminnesota.org 612-455-4202

For permission to copy lynn.shelton@enterpriseminnesota.org 612-455-4215

To make event reservations events@enterpriseminnesota.org 612-455-4239

To advertise or sponsor an event chip.tangen@enterpriseminnesota.org 612-455-4225

Enterprise Minnesota, Inc. 2100 Summer St. NE, Suite 150 Minneapolis, MN 55413 612-373-2900

©2025 Enterprise Minnesota ISSN#1060-8281. All rights reserved.

Reproduction encouraged after obtaining permission from Enterprise Minnesota magazine.

Enterprise Minnesota magazine is published by Enterprise Minnesota.

2100 Summer St. NE, Suite 150 Minneapolis, MN 55413

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Enterprise Minnesota 2100 Summer St. NE, Suite 150 Minneapolis, MN 55413

Bob Kill, president and CEO of Enterprise Minnesota, testifies with Rep. Jon Koznick (R-Lakeville), a strong supporter of Minnesota manufacturers.

The funds enable manufacturers to avail expertise from Enterprise Minnesota.

The 2025 Minnesota Legislature authorized $1 million to help small manufacturing companies remain viable amid the roiling economy. The grant, split evenly over two years, will primarily fund the “Made in Minnesota” program, an initiative that will help manufacturers take advantage of cutting-edge strategies from Enterprise Minnesota. These include enhancing productivity, deploying technology, improving management, growing talent, and developing effective business strategies.

“Made in Minnesota” received bipartisan support. Lawmakers from both rural and urban districts recognized the critical importance local manufacturers contribute to their communities, according to Bob Kill, president and CEO of Enterprise Minnesota. “We had strong advocates in both the House and the Senate who helped

push this through, even in a tight budget year,” Kill says.

“Made in Minnesota is a hand up, not a handout,” Kill adds. “These resources help companies invest in themselves — whether that’s getting certified, providing skills development for workers, or implementing new technology.” All grant recipients will have “skin” in the game. For every $1 of state investment, manufacturers must also invest $1.

The funding comes at a time when many Minnesota manufacturers are still navigating pressures of a post-pandemic economy, ongoing workforce shortages, and other uncertainties around world trade. Despite those challenges, manufacturing remains a crucial part of the state’s economy, responsible for 11% of Minnesota jobs and 14% of wages.

Kill says that 84% of Minnesota’s 8,600 manufacturers employ fewer than 50 people, and a significant portion have fewer than 10. These small shops, often located in rural communities, face steep hurdles when trying to modernize or expand. That’s where Enterprise Minnesota’s services come in. Since 2008, Enterprise Minnesota has applied state funding to help Minnesota manufacturers create or retain more than 12,000 jobs and increase or retain company sales of $1.46 billion.

Enterprise Minnesota has historically deployed such funds to help manufacturers reduce the financial burden of key services.

For example, a nine-person machine shop seeking ISO 13485 certification — a requirement for entering the medical device market — might pay $50,000 out-ofpocket. With this grant, that cost could be reduced by 20%.

“For a small company trying to break into a new market — like medical devices — ISO certification might be the barrier between growth and stagnation. Made in Minnesota resources can make breaking into new markets possible.”

“These kinds of investments can lead to expanded markets, new jobs, and stronger communities,” Kill adds. “And once a company earns that certification, we know companies will use it to grow.”

Kill also points out the ripple effect manufacturing has on other industries. For every dollar spent in manufacturing, about $2.70 is generated in economic activity across related sectors, such as trucking, accounting, and logistics.

“It’s not just about the factory floor,” Kill says. “Manufacturing creates good-paying jobs and supports an entire ecosystem of businesses.”

Kill says the momentum in the manufacturing sector has also been buoyed by increased enrollment at technical colleges, as more people begin to recognize manufacturing as a viable and rewarding career path.

“The perception of manufacturing is changing,” Kill says. “It’s high-tech. It’s innovative. And it’s essential.”

For now, the focus is on using the $1 million wisely, ensuring that the funding reaches as many small businesses as possible. Robb Murray

UBB’s mission identifies students who might have an interest in working with their hands and who have been traditionally underrepresented in the trades and manufacturing.

For the past three decades in a shipshape workshop in St. Paul, thousands of young Minnesotans have embarked on a life-changing journey simply by building a boat. The end result becomes much more than the gleaming wood vessel in front of them. Many are inspired to develop the skills to launch a successful career in the trades or manufacturing.

In fact, 98% of the more than 9,000 young people who’ve gone through nonprofit Urban Boatbuilders’ (UBB) apprenticeship program either continue in an education or training program or are placed in a job. It’s a big accomplishment for young people who’ve felt lost at sea during or after high school. They’re students who floundered in academic settings or whose interests and skills weren’t aligned with the traditional college track.

“Boat building is a really great vehicle for engaging young people,” says Executive Director Marc Hosmer. “It’s pretty amazing to see the transformation that happens.”

Cozy Robinson of St. Paul was 17 years

old when he arrived at UBB’s workshop on University Avenue. He’d been attending a transition school called Focus Beyond that works with special education students. He spent the next three years “learning a ton” about woodworking at UBB as well as “how much communication and teamwork matter.”

Robinson’s career epiphany came while he worked on a wilderness traveler canoe. “I realized that carpentry is for me,” he says. “I liked the hands-on part, and I like seeing that I built something.” Now, he’s searching for an apprenticeship in woodworking. He dreams of being “a full-time carpenter who goes around and fixes houses.”

What is it about boat building that changes lives? The organization started 30 years ago, when community organizers, educators, and wooden boat builders came together to inspire kids fresh out of the juvenile correction system. Studies show that learners who actively participate and

take an interest in their academic education are more likely to achieve higher levels of learning, particularly if they do it in a group. It’s called experiential learning.

Today, UBB’s mission focuses on identifying 16- to 21-year-olds who might have an interest in working with their hands in some capacity and who have been traditionally underrepresented in the trades and manufacturing industries. It receives referrals from teachers, counselors, schools, and communities. Hosmer says applicants must have some barrier to employment — such as their socioeconomic status or a disability.

For many of these new apprentices, it’s their first job (it pays $15 an hour). They work three days a week, anywhere from three months to a year, on a crew of eight to 10 young people. Each crew makes one boat — typically a canoe, rowing skiff, or kayak. “When you get a lot of people going on one project, it lends itself to all sorts of skill development,” Hosmer says.

Besides the technical piece, he says the

experience teaches young people the kind of “soft skills” that help people become successful, from learning how to work as a team to problem solving on the job to communicating effectively and receiving and giving feedback. It can be a lifeline for them as they gain financial literacy and learn how to improve their mental health and become advocates for themselves.

UBB staff also arrange field trips for participants so they can see a variety of worksites that offer union jobs, construction jobs, or other opportunities in trades and manufacturing.

“We’ll have young people come in the door with their head down, just very closed off, very reserved body language,” Hosmer says. “And by the end of their time in the program, they’re walking in with all this confidence, pride in who they are, what they can do, and what they are doing.”

UBB also connects with kids through a partnership program for metro area schools, after-school programs, summer camps, and community centers. They supply an instructor plus tools and materials — no

workshop required. Projects range from boats to longboards, which students are then free to keep.

UBB’s graduates offer more than work experience. Hosmer says employers would be hiring somebody who wants to be there, who wants to work with their hands or create new things — and they are ready for that next step in their life. “The skills they have are really amazing and powerful to see.”

As a testament to UBB’s successful program, Hosmer says he often hears from companies who say, “‘We have openings, who do you have for us?’” He says the organization is working on building relationships with employers.

UBB also plans to create a small manufacturing business in which program participants or alumni would make small wooden products. Hosmer sees this not only as an additional skill builder, but also as a vehicle for young people to understand entrepreneurship.

Gail Hudson

The Lakeland Company’s Curt Tillotson brings diverse experience to Enterprise Minnesota’s board of directors.

urt Tillotson has some fascinating stories about his very varied career. There’s the one about introducing the Geek Squad to “just one” Best Buy store in 2002 that led to a successful merger of the maverick computer repair guys with the big blue retailer. Or the one about starting out as vice president of sales for Nahan, the St. Cloud-based printing firm, even though he’d never worked in sales before.

But a favorite is about being connected with a competitor company in Omaha that was using a software system that Tillotson’s firm was considering buying. The owner of the company knew they were competitors but gave the Minnesotans a full tour of the plant. Not only did he show them how the software worked but talked about how he was implementing lean manufacturing principles to cut costs and remain competitive. “There was a mutual trust,” Tillotson says. “He firmly believed that America

needs to get better at manufacturing. We have slipped. He was doing manufacturing the right way and was willing to help others make American manufacturing better.” He wanted to share his wisdom with others — even competitors.

About the same time, Bob Kill, president and CEO of Enterprise Minnesota, approached Tillotson about joining the organization’s board of directors. “And I thought, ‘I want to be part of that,’” Tillotson says. “I agree manufacturing in America is not what it used to be. We have a lot of catching up to do. I think Enterprise Minnesota can help elevate American manufacturing.”

Tillotson started his career in accounting but brings a breadth of experiences from sales to operations to his current role as CEO of The Lakeland Company, a Twin Cities-based family of eight firms manufac-

turing and distributing electrical controls, enclosures, and other products for agriculture, rail, and additional industrial applications. He developed those skills by being just a little outside of the mainstream.

Working for corporate giants Pillsbury and Best Buy, he was never assigned to what he calls “the mother ship.” At Pillsbury, he worked in restaurants, not refrigerated dough. And, for Best Buy, he oversaw a unit developing new income streams, including the acquisition of the funky computer repair business, Geek Squad, and setting it up in Best Buy stores. Acquiring Geek Squad and letting it keep its nerdy persona — the orange signage, Volkswagen service vehicles, and skinny black ties — seemed risky to Best Buy’s corporate image protectors at the time.

“We’re just going to test it in one store,” Tillotson remembers saying as the first Geek Squad unit opened in 2002 at a Best Buy in Maple Grove. It was quickly rolled out to all Best Buy stores and currently employs 20,000+ repair technicians as services have become a significant share of Best Buy’s revenue and earnings.

As exciting as these experiences were, Tillotson realized that the Fortune 500 was not where he wanted to work. “I always knew I wanted to go to a smaller company. Many of the projects I worked on at large corporations never saw the light of day,” Tillotson says. “I really like a place where

you can make an impact.”

He left Best Buy to become CFO for St. Cloud-based grocery retailer Coborn’s, then signed on as vice-president of sales — something he’d never done — for Nahan, the printing, direct mail, and marketing firm, also based in St. Cloud. The plan was to move him into finance after the then CFO retired. While waiting for that to happen, Tillotson learned everything about the print business and sales strategy. “I was a very willing student,” he says. “It was a great experience, and it set me up for running the printing company.”

When private investors bought Nahan in 2021, Tillotson moved to Lakeland, which has 250 employees divided among the eight companies. Each company has its own business leader. They occasionally work with each other and share resources such as human resources and finance, but each has unique products with its own market and varied challenges. This is where Enterprise Minnesota has come in, Tillotson says. Different Lakeland companies have sought assistance with quality

assurance and ISO certification, strategic development, and leadership development. It’s Tillotson’s job to help each business unit succeed and grow profitably, while staying in alignment with Lakeland’s overall goals, says Joel Scalzo, business development consultant for Enterprise Minnesota. “The takeaway I get from working with him is that he provides calm leadership,” says Scalzo.

His big company background has helped in working with some of Lakeland’s big company customers. “You get the challenges of working in a big company,” Tillotson says. “You have sympathy for them. But you can nudge them to direct more business our way.” Implementing more lean strategies and managing costs to make each Lakeland company globally competitive will be key parts of “winning the market,” going forward, Tillotson says.

Currently, one of the Lakeland companies is making a controller for a global OEM. A European firm is also manufacturing the same controller. “The plan is that they will do the European union, and we

will do all of the Americas,” Tillotson says. “If they trip up, we may find ourselves doing Europe’s work, and if we trip up, they might be here in America.

“You have to question almost everything you are doing,” Tillotson says. “Taking costs out is a must, whether it’s cost cutting or cost containment.”

Kill describes Tillotson as “a growthoriented executive,” who can find hidden opportunities and innovate. “As manufacturers, you’ve got to know your space,” Tillotson says, “but adjacent spaces could have opportunities. Using that strategic thought process is something Enterprise Minnesota offers. That’s a big deal.”

His experience in a variety of roles and a range of companies will bring connections and new insights to Enterprise Minnesota, Kill says. He’s dealt with a variety of complex situations. “His style is leadership, not management,” Kill says.

“I look forward to being on the board and hope to provide guidance and connections,” Tillotson says.

Mary Lahr Schier

Auscon is counting on ISO to take it to the next level.

It’s easy to see why people love a good “started the business in a garage” story. It reminds us of the value of hard work, perseverance, ingenuity — and an unfailing belief in a dreamer’s vision.

At Auscon, manufacturer of precision electrical components, the company has upped the ante on that particular lore. But to get to the genesis of their story, you have to think smaller than a garage. And one floor lower.

The Austin-based company founded in 1994 began in founder Larry Erickson’s home.

Lori Reed, Auscon’s purchasing and quoting manager, tells the story: “We started in the basement. Then we moved to the garage. And then we started doing things that required more space. Fortunately, Larry had a horse barn that we converted into a shop and moved most of our equipment out there. It was a nice place out there. We had a lot of space for what we were doing. And then we ran out of space.”

Post horse barn, Auscon rents space

in Austin’s industrial park. And now the company is taking the next logical step in its evolution: ISO certification.

Like many companies, Auscon started getting requests from clients that wanted Auscon to get ISO certified. Company leadership also recognized that doing so was the best way to take the company — which has customers all over Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and South Dakota — to the next level.

Auscon has long prided itself on customer service. From its website: “Our people-first strategy means that when you choose to work with us, we put your needs first. You’ll never have to chase us down to return a phone call or email, or struggle to get a meeting when you need it. Every client gets a dedicated project manager who will ensure you receive excellent customer service from start to finish.”

Auscon manufactures custom printed circuit boards, or PCBs. PCBs are a major part of many electronic devices, acting as a base for assembling and connecting com-

ponents. You’ve probably seen them; PCBs are the futuristic-looking green boards with silver conductive pathways that look a bit like street maps for a big city. Auscon also manufactures custom cable and wire harness assemblies for OEM applications, according to its website, “where off-theshelf cables simply aren’t an option.”

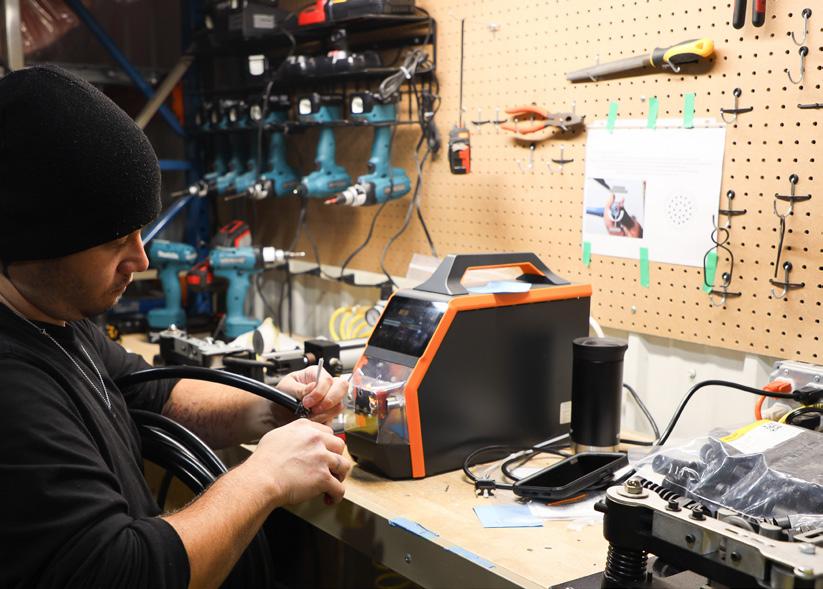

Much of the company’s process utilizes automation, although Auscon also takes jobs requiring hand tooling.

To maintain their edge in both customer and quality service, Auscon management sought the help of Enterprise Minnesota to guide the company through what it knew could be a complex process.

Getting to certification, however, is never an easy or swift process.

Auscon Operations Manager Matt Schrom, who came to the company after the first few moves, arrived with a bit of ISO experience. Having witnessed it firsthand, he says he knew better than to have someone in-house attempt navigating the process. And from that experience, he says he knew going through the process and getting certified would make Auscon more efficient and give employees solid, evidenced-backed reasons for changing and, hence, improving the way

things are done.

“It’s a quality standard. I’m pretty heavy on quality, and I think Lori is too,” Schrom says. “It helps identify for people that we are willing to put effort into quality for our company and prove to our customers that we want high standards.”

Getting to certification, however, is never an easy or swift process. Auscon took about nine months to get it done, and that was with expert help.

Both Reed and Schrom say there wasn’t much pushback from Auscon’s labor force; pushback can happen when a longtime employee is told the things he or she had been doing for years is getting a justified overhaul. Instead, they say, Auscon’s workers seemed genuinely interested in making improvements to not only enhance the company’s reputation and credibility but also give them more purpose about the importance of their role — an “every spoke is important on this wheel” kind of vibe.

“It really emphasized people paying attention to their job,” Schrom says. “Before it might have been an attitude of, ‘Oh, just

send it out.’ Now, with ISO being there, there’s a standard of having the work order and people following the work order.”

Schrom says a culture of abiding ISO norms and rules can help identify and, more importantly, avoid mistakes.

“We are a contract manufacturer that lives off a BOM (bill of materials). So, if it’s in the BOM we follow it,” Schrom says. “But when we’re putting it together and we find something that doesn’t seem right, we’ll contact the company and, in most cases, they’ll have to change the BOM. Not only did ISO improve the process of the material going through, it also improved the other company’s quality of the product because they discovered a mistake in their design.”

Reed, who has been with the company for nearly 30 years, said finally getting Auscon’s ISO certification was a big deal. It was a morale boost, she says, for both management and staff. Getting over that hurdle, she says, could mean big things for the company’s future.

“We knew we had to do it,” Reed says.

“It was something that, in order for us to grow even bigger — which we plan to do — we had to go through this process. This will help us get more clients, more customers, because a lot of places look for that.”

Robb Murray

Inside Enterprise Minnesota | An ongoing series

Sandy Borstad brings decades of experience from business and higher education to counsel manufacturers on effective leadership development.

Sandy Borstad finds something enormously satisfying in helping manufacturers and their employees achieve their goals in a way that benefits all involved. It’s work she has done throughout her career, in varied settings and industries. “When you get to go to work every day and help companies and give people opportunities, life is pretty good,” she says.

Borstad joined Enterprise Minnesota in 2024 as a business growth consultant, bringing nearly three decades of experience in talent and leadership development. Her most recent position as the training and outreach manager at St. Cloud Technical & Community College gave Borstad ample opportunities to meet manufacturers’ training and workforce needs. Focused on customized training, Borstad served as a conduit that brought just the right resources to manufacturers to fill their training gaps.

“There are amazing manufacturers throughout the state,” Borstad says. “I loved working with each of them and getting to know their businesses and helping them find the skill development solutions they needed. And at the same time, I was

helping individuals at the companies further their skills and their careers and their earning opportunities.”

Borstad raised her hand when an opportunity arose at Enterprise Minnesota

“Sandy’s able to make sure clients understand how leadership development can have a real impact for them.”

–Bob

Kill, Enterprise Minnesota

to work more closely with manufacturers at the root of their leadership and training efforts. She was confident she could make an even bigger difference in manufacturers’ growth by more directly sharing her knowledge and experience with them.

Bob Kill, president and CEO of Enterprise Minnesota, appreciates Borstad’s rich real-world experience gleaned from working at several successful companies

and in higher education. Her long tenure in human resources, leadership, and development fuels her co-workers’ confidence that Borstad can make a fast and lasting impact with manufacturers. When Enterprise Minnesota’s business developers realized how much insight and experience Borstad brings to the table, they quickly started looping her in on client interactions, Kill says.

“Sandy is approachable. She’s a good listener who asks good questions, and she brings that together with her real-world experience, positivity, and energy,” Kill says.

Focusing on talent and leadership development, Borstad uses Enterprise Minnesota’s Leadership Essentials series to help clients delve into their specific needs. For one client with ambitious growth goals, Borstad is helping create a training program. It involves mapping out skills development and creating repeatable and consistent instruction, with unified expectations.

By baking in clear expectations and the route to achieving established goals, manufacturers can more successfully hire, develop, and retain their employees. At the same time, employees build skills that

enable them to take on greater responsibility, Borstad says. It’s that win-win she finds rewarding.

Though Borstad didn’t envision a career in training and development, it unfolded that way after starting her first post-college job. She worked for nine years at Creative Memories, a central Minnesota scrapbooking company. Borstad quickly moved into training and then instructional design, where she developed training programs for Creative Memories’ independent sales consultants. Before long she became a field development manager, responsible for the performance of the company’s central region of the United States.

Borstad had a similar evolution and tenure at the food company Tastefully Simple before joining Blattner Company, an engineering, procurement, and construction business focused on large-scale renewable energy projects. She headed up a team that created and delivered training and development programs for Blattner employees. In addition, Borstad created and led field leadership development programs to create a pipeline of emerging leaders for the company.

When Borstad joined St. Cloud Tech, she had amassed 25 years of inside knowledge of the corporate world and how to provide training that employees at all levels need to succeed. Borstad got steeped in the transportation and manufacturing sectors, building extensive understanding of their workforce challenges. She became adept at finding innovative and personalized ways to provide the region’s clients with just the right instructor or custom training approach to meet their needs.

Now at Enterprise Minnesota, Borstad works with veteran and emerging company leaders on ways to increase productivity, employee retention, and engagement. She finds it rewarding to dig into manufacturers’ challenges and land the wins that come from leadership development.

Borstad believes her strengths lie in using her creativity and resilience to discover solutions that solve manufacturers’ challenges.

“If you can name a problem, you can solve it. I like to help people use their creativity to come up with a solution,” Borstad says. “With our creativity and resilience, let’s see what we can do.” Suzy Frisch

The Automation Loan Participation Program makes companion loans to fill gaps in financing needs for businesses purchasing machinery, equipment or software to increase productivity and automation.

Medical device manufacturers might soon find expanded market opportunities when the FDA streamlines its regulatory requirements.

To pass future FDA inspections, companies will need to meet all the requirements included in ISO 13485, though obtaining certification through an independent external audit is not mandatory.

For decades, medical device manufacturers and their suppliers have followed two sets of quality standards. To pass annual inspections by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), they followed one set of guidelines. To earn medical-specific ISO certification, they followed another.

Earlier this year, the FDA finalized a rule that will align FDA requirements with the International Standard Organization’s medical device framework, known as ISO 13485:2016. When the new rule becomes effective in February 2026, companies with ISO 13485 certification will be well-positioned for FDA inspections.

Those companies will also broaden their access to customers that require suppliers to be ISO certified. It’s a win-win opportunity for manufacturers, and experts recommend they pursue ISO 13485 certification to take advantage of the new guidelines.

Enterprise Minnesota’s business growth consultants have been helping companies navigate the ISO 13485 process for years. One of these experts, Keith Gadacz, says the regulatory update offers a chance for companies to improve processes while expanding their potential pool of customers.

To pass future FDA inspections, companies will need to meet all the requirements included in ISO 13485, though obtaining certification through an independent ex-

ternal audit is not mandatory. Gadacz says manufacturers that go through the certification process will achieve two goals.

The first is preparation. He likens the certification and inspection process to competing in archery. “If you only shoot once a year when the judge shows up, you may not hit the target very often,” he says.

But if companies consistently strive to follow and document processes for their internal audits and then go through external audits each year to earn and maintain ISO 13485 certification, they will be ready for FDA inspection. “That will keep those skills sharp, and we can hit the target consistently, which makes it a lot easier when the FDA comes,” Gadacz says.

ISO 13485 certified companies also enjoy a competitive edge over those that do not hold certification, Gadacz says. Many OEMs require their suppliers to be certified, and even if they do not, certified companies show potential customers that they have outstanding quality systems. “If you have to comply with it anyway, why wouldn’t you go through the certification process so you can use it to earn more customers?” Gadacz says.

That’s exactly the thinking behind R&D Batteries’ decision to earn ISO 13485 certification. The Burnsville company designs and manufactures a wide range of batteries, including many for medical devices. “Our main focus is replacement

batteries, and our main customers are biomed engineers or technicians that work on equipment that’s usually in hospitals such as heart defibrillators, infusion pumps, or baby scales that have battery backups,” says Christopher Noddings, R&D’s vice president of operations.

Noddings says ISO had been on the company’s radar for the last decade or so because it was becoming the industry standard. Many of R&D’s customers — when they were looking for new suppliers or recertifying vendors — would first ask if the company was ISO certified.

“That was just after COVID, and we needed some more projects. That’s when we decided to tackle ISO,” Noddings says.

The investment does open doors to opportunities that wouldn’t have been there if we didn’t have the ISO certification,” Noddings says. “I’d say it’s contributed to four, five, or six percent of our growth.”

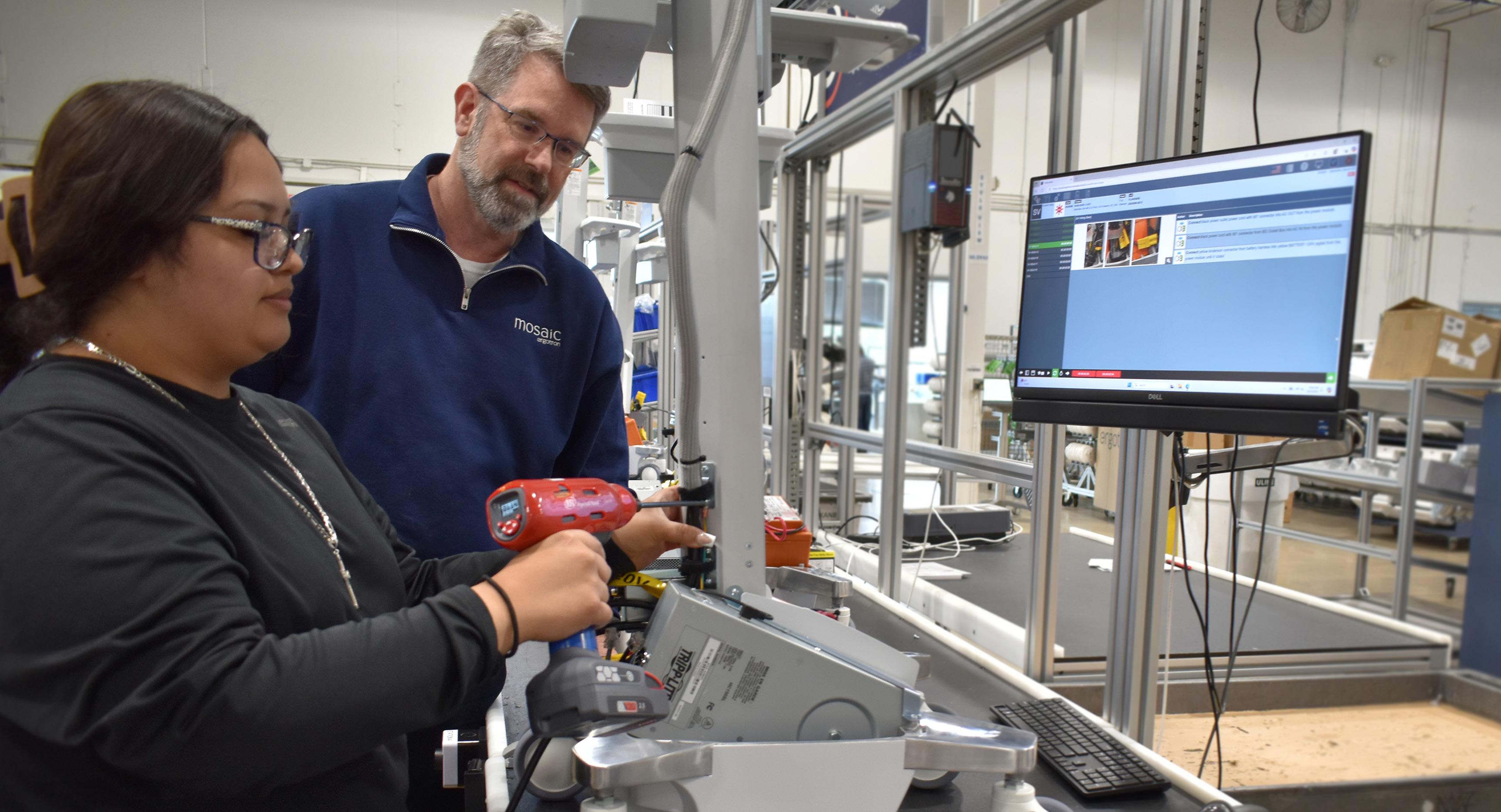

A similar mindset drove Ergotron to seek ISO 13485 certification. Based in Eagan, Ergotron serves global markets with a range of products that display computers and keyboards designed to improve employee movement, including mobile workstations for clinical settings.

“None of our Ergotron-branded products are FDA registered, but because they can be used as componentry in other systems, that’s where we have a link into it. And that’s really where 13485 became a market advantage for us,” says John Berger, the company’s director of global quality.

“We can approach the largest and most globally recognized medical device manufacturers and say, ‘We can be a supplier to you. We’re ISO 13485 certified and FDA registered as a contract manufacturer of medical devices.’ That’s a recognized standard for them, and they understand that we have a quality system to support the type of needs that they might have,” Berger says.

Before going through certification, Noddings says R&D had a fairly informal environment. “We knew how to make batteries, and we knew how to have the best quality.” Obtaining certification required documenting every process. “Putting every single procedure that we have here in writing was our biggest challenge, and that’s where the majority of our effort was.”

Noddings says he and Julie Moldenhauer, R&D’s production and quality manager, devoted the bulk of their time for the better part of a year to certification

and relied heavily on Gadacz for direction. “Keith helped us understand the procedure and how it tied to our business,” Noddings says.

R&D’s effort paid off during the company’s first post-certification FDA inspection. “We had an FDA inspector come through as we finished our first ISO audit. Anything the inspector asked, we had an ISO procedure to respond with,” Noddings says.

Ergotron had already earned ISO 9001 certification, but to broaden market appeal, the company decided to pursue ISO 13485 also. “We chose to integrate the ISO 13485 elements into our existing ISO 9001 certified system. So, we have one system that includes both elements, and all products that we design and make are built under the same system,” Berger says. “Even though some of them may not require it, they all get the benefit of it.”

Preparing the company for ISO 13485 certification required understanding the additional requirements and filling those gaps. “There’s more attention to certain things, such as lot traceability of product through the system,” Berger says. “Just understanding the gaps was over half the battle, and then closing the gaps was the rest of it.”

Gadacz helped Ergotron understand and fill those gaps, working with the company’s quality group that focuses on standards and internal audits. “Working with Keith, we took it on as a team. We would arrange and follow up and track the action on items,” Berger says.

It was important to Ergotron to ensure employees weren’t just handed a new set of standards without any input. “We also included the process owners. Our goal was to make them part of understanding what was required and part of creating it,” Berger says.

Ergotron also asked Gadacz to train the employees who serve as the company’s internal auditors. “He was helping our folks to become experts so that we could maintain it ourselves,” Berger says.

While obtaining certification was a challenge, Noddings says it was worth the effort. “It was a very large amount of work, and it does require us to take more steps than we would normally have, but it’s improved our overall business,” he says. “It’s very clean and very efficient, and we improve it every time we have a surveillance audit or we’re recertifying. We sharpen the edges a little bit each time.”

Kate Peterson

Marty Seifert served for 14 years in the Minnesota House of Representatives, including three years as minority leader. He ran for governor in 2010 and 2014 and now works in government relations for St. Paul-based Flaherty & Hood, advocating on behalf of Enterprise Minnesota and small- and medium-sized manufacturers.

How has this year’s legislative session differed from the last one, when manufacturers got blindsided by sweeping changes to mandatory paid leave requirements?

This year there’s a tie in the Minnesota House, which has only happened one other time in history. We have a narrowly divided Senate — Democrats control it by one vote. You really can’t get any closer than that.

That’s in contrast to the last session, when the DFL had a trifecta — control of the House, the Senate, and the Governor’s mansion. They felt they had a mandate to march through a pretty ag-

There were a lot of alarm bells about how onerous (paid leave) would be, how expensive it would be, and how confusing it would be, and it fell on deaf ears.

gressive agenda. The unions and a lot of their base wanted a paid leave program. Essentially, they told manufacturers and the business community that they were going to do this, and they didn’t really accommodate the concerns they heard. It passed with no Republican votes. There were a lot of alarm bells about how onerous this would be, how expensive it would be, and how confusing it would be, and it fell on deaf ears.

That session really showed the value of direct outreach to legislators regardless of their party. For manufacturers, that means giving them tours and explaining to them that their legislation

makes a big difference in your lives and your business. It’s showing that the more regulations, rules, and taxes they pass, the more manufacturers have to deal with.

Did they make any modifications to the paid leave requirements during this year’s session?

This legislative session was mostly about budgeting. To get significant changes to the paid leave laws passed during the last session, Republicans would have had to tie those changes to the budget. That would have meant shutting down part of the government. That wasn’t going to happen. Paid leave is popular with most people, and many legislators didn’t understand the negatives.

The best way to explain those negatives is to have elected officials come to your business. You have to show them: here are my seven employees, and here’s what we do. This person is really key to my business, and if they go on paid leave for two months, our whole system fails. A lot of lawmakers don’t understand that unless they’re on site and see that person and see the role they play in the business.

They need to know that for some of our really small businesses, this could jeopardize the existence of their business. They will have to shut down, at least temporarily, if they lose one or two key employees to paid leave for a couple of months.

There was a critical provision to fund Enterprise Minnesota included in this year’s budget. What did that show about support for manufacturing among lawmakers?

We had bipartisan support in both the House and Senate for Made in Minnesota, which used to be called the Growth Acceleration Program, or GAP. Early in the session and through mid-April, we were in the budget for half a million dollars per year for the biennium. We had very good hearings in the House and the Senate, and it was approved by the Jobs Committee and the Finance Committee in the Senate. The House had an impasse over other issues, so it wasn’t finalized until after they adjourned on May 19. Ultimately, they kept that $1 million in funding for Enterprise Minnesota, showing that we really do enjoy strong bipartisan support.

Keeping that funding despite chal-

lenges to balance the budget was critical because of some potential challenges with federal government funding that helps support Enterprise Minnesota. It was also a sign that lawmakers understand the value of manufacturing across the state, and the importance of Enterprise Minnesota in helping companies grow.

on these policy issues?

When the legislature adjourns, they have literally seven months when they can do a tour. So, we’re really encouraging our manufacturers to talk to their local legislators and get them out to see their operations. Large, medium, and small, it doesn’t matter what their size

When I was in the Minnesota House, I toured manufacturers in my district, both big and small.

is, they’re all important. Direct outreach to legislators, regardless of their party, lets you make a personal connection with them. We have to tell our story to both House and Senate members, both parties, rural and metro.

It can have a huge influence when an elected official has toured your place. Making that personal connection will pay off when legislation that affects manufacturers is under consideration. They’ll have a better understanding that manufacturers, especially the smaller manufacturers, are equipped to produce widgets, but they’re not set up to handle complex and expensive mandates.

When I was in the Minnesota House, I toured manufacturers in my district, both big and small. Schwan’s was the biggest employer in my district, and I did multiple tours there. But I toured small manufacturers as well. They produced some really interesting things that I think people didn’t know were even made in Minnesota. I still remember one guy who made fishing lures — it was literally just him making fishing lures in his house. Tours have a huge influence — I still remember them today.

ProCircular is a cybersecurity company focusing uniquely on the careful balance between relationships and technical expertise. Our team offers a comprehensive suite of services tailored to help organizations manage risk and proactively navigate the ever-evolving landscape of cybersecurity challenges. We approach every service to safeguard our clients and their vital data, all while fostering

A nationally recognized supply chain expert provides insights about how manufacturers might cope with the impacts of the evolving U.S. policy on tariffs.

Enterprise Minnesota president and CEO Bob Kill recently interviewed supply chain authority Willy Shih, the Robert and Jane Cizik Professor of Management Practice in Business Administration at Harvard Business School, about the impact of impending tariffs and the unpredictable trade climate on manufacturers. Kill first spoke with Shih in late March, prior to the Trump administration’s major tariff announcements on April 2, or “Liberation Day.” Dramatic changes in those announced policies warranted a second conversation with Shih in late May. As this magazine was finalized for publication, the triple-digit tariffs imposed on China were on a 90-day pause. The Trump administration was also in the midst of bilateral discussions with other trading partners to avert the punitive tariffs announced on April 2 but suspended until July 9.

Three major themes emerged from these discussions. Shih pointed out the historic shift from an increasingly free global trade climate in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, to growing barriers to international trade beginning with the first Trump administration. He also discussed the consequences, both intentional and unintentional, of the recent trade policy changes. Finally, Shih detailed actions manufacturers can take to survive the new trade environment.

Bob Kill: The challenge of this discussion is that the tariffs are constantly changing. Will you look at this interview in a month and change 50% of what you’ve said?

Willy Shih: We do have to preface everything with, “By the time this comes out…”

One thing that will stand the test of time is that we’ll look back on what I would call the golden age of globalization, which was the late 1990s until probably around 2009. It was a time of constantly decreasing trade barriers and tariffs, and a time of spectacular growth.

Beginning in the early 1980s, when I entered the workforce, the tradable sector was constantly growing. I was bringing imports from Europe into the U.S. on a weekly charter flight. When I traveled to Europe, I had to bring Deutsche marks, British pounds,

Swiss francs and French francs. Now of course it’s the euro in the Eurozone.

Tariffs and trade barriers just kept coming down. You had the introduction of the shipping container, growth in global air cargo, and enormous improvements in communications. And then we saw giant container ships that made long-distance oceanic shipping really inexpensive. All this increased the size of the tradable sec-

tor — the goods that can be made in one place and consumed far away. What’s going on now is we’re decreasing tradability. We’re making it harder and more expensive to move goods across borders. It’s turning back the clock. We’ve been through this period where there’s been relatively free, relatively open trade. People have built their supply chains assuming there aren’t those barriers. Now we’re going to go put those barriers back in. That’s a problem.

Kill: What are the most significant consequences of the tariff turmoil right now?

Shih: What’s killing people right now are the day-to-day changes and the unpredictability.

Every day the news says something different. Everybody wants to wait until the dust settles until they make any kind of long-term commitments or bigger investments. That’s very hard on a lot of the small businesses that may not have the capital to see themselves through this period of turbulence.

Also, since the election people have

Chinese New Year, and in fact, if you look at inventory levels, at Walmart, at Target, places like that, they were up sharply.

People are trying to get as much of this stuff into the country before tariffs hit. But that creates its own set of problems, because now you have too much inventory. We saw what happened during the pandemic: too much inventory, too little inventory. But worse than that, you have a lot of cash tied up.

Once the tariffs are in place, there’s the complexity of complying. I was in an aerospace components factory in Ontario, Canada. The steel or titanium for those components would come from the U.S. or another country. They would make the component, then send it to Oklahoma for heat treating. And then they would send it back over the border for another step, and then across the lake to Ohio for more processing. Sometimes these parts cross borders six or seven times.

So how do you assess the tariff on that? Is it applied every time it crosses the border, or do I get credit for having paid the tariff when it went previously, as a lower value component? What happens if it’s steel? There’s a separate steel tariff, and then there’s a generalized tariff on everything coming from this country. Do I stack the tariffs? There’s just a lot of detail in terms of how this will all be executed. And still, no one knows how these will be executed.

known that tariffs were going to be a problem so there’s been a lot of frontrunning, and by that I mean bringing cargo in early in advance of when tariffs will hit. Normally there’s a peak season on the trans-Pacific trade lane, and the peak season starts to wind down in late November because typically if you can’t get it in before the holidays you can’t get it into the store. Peak season didn’t end this past holiday season. It went right up until

Kill: Though the tariffs are still up in the air, do you see unintended consequences stemming from other trade-related policy changes?

Shih: Yes. It’s a very complex system, and for every one of these changes, there’s potential for collateral damage.

When you stop the de minimis exemption [a provision that allows qualifying, low-value shipments valued at less than $800 to enter the U.S. duty-free, which streamlines customs procedures and reduces administrative burdens for smallvalue transactions], all of a sudden you have to file a lot of paperwork and do in-

spections, and you get a 1 million package pile up at JFK Airport in one day. Another example is a proposal to charge Chinese-made ships for every port call. These are huge ships, so a $1 million fee would end up being maybe a couple hundred bucks per container. The way container lines operate, if I bring a ship from Asia across the Pacific, I’ll come into Long Beach and unload. Then I might go up to Oakland and pick up agricultural products. Or I might go up to Seattle/Tacoma and pick up more containers.

If I get charged for every port call, maybe I’ll come into Los Angeles/Long Beach and just head back to Asia to avoid that access fee. Then the agricultural exporters wouldn’t have enough capacity out of Oakland anymore. They’ll have to bring everything down to Los Angeles/

Once you start applying tariffs broadly to the countries that are principal sources of supply, either prices will go up, or the supplies will be very limited.

Long Beach. These are the kinds of things that increase barriers and inefficiencies and increase costs. It would make it more expensive to export a lot of those products. That was certainly not the intent of that proposal.

Kill: It seems likely that most of the tariffs will eventually settle at rates higher than we are used to. In a broad sense, how do you expect permanent, higher tariffs to affect supply chains and pricing?

Shih: Look at fresh produce as an example. People want to enjoy seasonal fruits and vegetables, even when they are out of season. Historically, people generally ate just the produce that was in-season. You ate strawberries when they could be grown in California or Florida or New Jersey. You ate grapes from August until October. Now growers can bring those products in from the Southern Hemisphere or from all over the world and extend the season.

But if you apply a 25% tariff, that’s more than the profit margin they make from growing and distributing. Who’s going to pay for that? The grocers and

Much of the cost of aluminum is driven by the cost of electricity. Domestic aluminum makers would have a hard time being competitive with imports from Canada because of Quebec’s low-cost hydroelectric power.

distributors set the price, and then the foreign growers will have to decide if they can afford to import once they apply the tariffs. They might pay the tariffs this year, and then next year they might decide not to plant.

Either the price has to go up so that the grocers are willing to pay more to have them out of season, or we’ll go back to eating seasonal produce only when it is in season. Tariffs will have the same effect on manufactured goods. Once you start applying tariffs broadly to the countries that are principal sources of supply, either prices will go up, or the supplies will be very limited.

Kill: Will some manufacturers lose customers because of this?

Shih: You could see a lot of collateral damage if there are no exemptions for certain imports, which there were during the first Trump administration, if certain materials and components couldn’t be sourced domestically. It remains to be seen if that will happen again.

I have this part on my desk — it’s part of a brake assembly that goes on a Boeing 787. This is a special high strength, high temperature steel that is only made in Austria. It’s the only material that is certified for this kind of aircraft usage. An Ohio manufacturer imports that steel, turns it into the part, and sends it back to France, where it becomes part of the landing gear that they ship back to the Boeing factory in South Carolina to put in a 787.

The problem is, the French guy sees your cost just went up because of the tariffs, so why send it to Ohio? Why not get somebody in France to make it?

During Trump’s first administration this manufacturer got an exemption. But they are saying there will not be any exemptions this time.

Kill: Do we have enough domestic capacity to make what we need here? Is there a source for high performance ball bearings, for example, or are there some components that just have to come from outside the country?

Shih: We still make a lot of things, but we don’t make them in the quantities we

Growing American manufacturing when it’s not competitive means everything is going to cost more. To make it competitive again, you’ve got to be more productive. And that means using automation when you can.

need for mass production. We do make printed circuit boards in the U.S., for example, but by and large they are for the aerospace and defense markets. But when you need domestic production for broader markets, they’ll cost a hundred times as much as imports. That cost doesn’t matter to defense and aerospace; they have to be made domestically [for security reasons]. The other question is, could you scale

up production? If you want to bring all this stuff on shore, you need a lot of investment. The latest circuit boards are very complex, and you’d have to have a lot of expensive equipment to manufacture them. There’s also the issue of raw materials. We just had the last electrolytic copper foil producer in the U.S. say they were closing shop in February. They were in South Carolina. All the aerospace users, who don’t need much volume, just bought something like a 10-year supply.

Another example is aluminum. So much of the cost of aluminum is driven by the cost of electricity. Quebec has lowcost hydroelectric power, so their cost of electricity is much lower than it is in the U.S. Domestic aluminum makers would have a hard time being competitive. If you put a tariff on imported aluminum, for any manufacturer that has aluminum as a significant part of their bill of materials, their costs will suddenly go up.

Kill: What should manufacturers do to prepare for the general shift toward increased trade barriers?

Shih: The thing that I’ve learned the most since the pandemic is that you have to pay attention to what’s going on in the logistics stuff. It’s easy to forget that there’s inventory in transit, which may suddenly get subject to duties. Some importers have somebody who’s focused on logistics networks, who’s watching the trade lanes, who knows what traffic looks like in the Red Sea, who’s on top of port delays in Ningbo and Shanghai. These days, that can inform you a lot in terms of what problems to anticipate.

Manufacturers also need to think about how to get more flexibility in sourcing. It used to be that importers used a strategy of China plus one. They added some step of production in another country, Vietnam, for example, so that country is the source of the product. But the current mindset of the administration seems to be driven by who has a bigger trade surplus. The three countries with the biggest trade surpluses are China, Mexico and Canada, and that’s why they were the first three to get hit. You can see who else will get hit based on trade imbalances. If you’re bringing stuff in from Vietnam, Germany, Japan, or Korea, your day will come sooner rather than later. Pay attention to things like that.

Kill: How should companies manage their supply networks right now, during this period of uncertainty?

Shih: They need to keep an ear to the

ground and listen to what’s going on. They should also do some scenario planning with their customers and their suppliers to figure out how they are going to deal with these things.

If you have a long supply chain with a lot of links and you put a shock in the front, it takes a while to propagate through. A manufacturer might have a supplier in the U.S. who is dependent on imports. There were all these canceled sailings in April. If that supplier stopped importing in April, but didn’t have an alternative, the question is, how much inventory does that supplier have before they run dry? Manufacturers need to understand how much inventory is in the pipeline, when they are going to run out of parts, and when they might have to stop production.

Even though they’ve paused the tariffs, that shock still comes through because after April 2, basically everything com-

I think the bigger impact will be the macro effects, because all this rapid change in policy is causing a lot of uncertainty, and that’s freezing investment decisions.

ing out of China got shut down. If you rely on components or parts that come out of China, you’re going to run out. The administration is imposing new tariffs or rules on a day-to-day basis, but supply chains respond on a much longer time constant.

Hopefully manufacturers have ordered ahead on critical inputs coming from China. If they order ahead, they will have to find additional storage space. They’ll have that cost, and the cost associated with carrying inventory. And there’s always the risk of obsolescence when you’re carrying that kind of inventory.

Kill: Is this a wakeup call for how they deal with suppliers over the long term?

Shih: Manufacturers need to be flexible when they work with domestic suppliers. They need to focus on long-term relations and not just be so transactional.

I’ll give you an example. I was in the

Toyota factory in Georgetown, Ky. last summer. They make sedans competitively in the U.S., but the Detroit automakers can’t make sedans competitively in the U.S.

Most of that factory’s suppliers are in Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, Alabama, and Indiana. I was looking at their incoming steel. And I said, “You use American-made steel. That’s more expensive than the imported stuff.” They responded that they have a strategic longterm relationship with their suppliers. They use a special steel that an American steel mill makes. They will have ups and downs, but they are committed to a longterm relationship with that supplier, and I’m sure they get it at a better cost. There is wisdom and insight in that in terms of companies’ relationships with their suppliers. You can build long-term strategies to weather this kind of storm.

Kill: If companies are bringing more production back to the U.S. from low-cost countries, what can they do to boost productivity?

Shih: When you moved production offshore in the past, you had to pay for the factory, pay for moving the supply chain, pay for hiring and training the workers. You got a lower product cost, so that move paid for itself in a short time. That works when you’re going from a high-cost country to a low-cost country. When you’re going from a low-cost country to a high-cost country, it doesn’t work. You don’t get cost savings that pay for the move. What we’re trying to do is we’re trying to get American manufacturing competitive again. Growing

American manufacturing when it’s not competitive means everything is going to cost more. To make it competitive again, you’ve got to be more productive. And that means using automation when you can.

I see a lot of resistance to automation because we’re afraid that it’s going to take away the jobs. The problem is, if American manufacturing doesn’t have

Even though they’ve paused the tariffs, that shock still comes through because after April 2, basically everything coming out of China got shut down. If you rely on components or parts that come out of China, you’re going to run out.

high labor productivity, there are a lot of things you cannot afford to make here. If you’re going to make it in the U.S., you have to be competitive on cost. You have to have the best productivity in the world. Manufacturers can start with automating some of the simpler tasks, like palletizing and heavy lifting. Those aren’t great jobs, and they should automate as much of that as they can anyways. It’s all about getting productive and getting globally competitive. If you can do that, there are

great jobs to be had. But this belief that automation takes away jobs — we’ve got to get over that.

Kill: The 90-day pause on the China tariffs doesn’t expire until August, but

other countries have a July 9 deadline before reverting to the April 2 rates. What do you think will happen then — maybe an extension of the pause?

Shih: I think a lot of people are saying there’s going to be a 10% universal baseline, which is probably going to apply to everybody. That’s significantly higher than where the U.S. was. And then I think what you’re going to see is sectoral tariffs on particular sectors. I think that’s going to depend on who the trading partner is and what kind of deal they can negotiate.

I think the bigger impact will be the macro effects, because all this rapid change in policy is causing a lot of uncertainty, and that’s freezing investment decisions. If they don’t resolve it, and they continue to push it to later dates, then those macro problems persist. Then all you end up doing is freezing everybody’s ability to invest because with that level of uncertainty, nobody’s going to invest in a new factory in the U.S. when the rules change every few weeks or days. You need to have some stability before you have the confidence to do that.

Make your next move with the bank that’s invested in your success.

At Bremer Bank, we take the time to understand your business inside and out, then we provide personalized solutions and services tailored to your unique needs, all from one convenient place. Together, we’ll help you achieve your goals. Put us to work for you at bremer.com

With three locations and expanding family leadership, Revolv Manufacturing sets a single course toward growth.

BY MARY LAHR SCHIER

In 2022, Brainerd-based Stern Co. Inc. rebranded its manufacturing arm as Revolv Manufacturing, a name that alludes to the rotating molds the company uses to make everything from kayaks to giant fuel tanks to delivery robots at its three locations across Minnesota. The clarifying name change coincided with a shift in the company’s core value statements as well as the increasing role of the next generation of company leadership.

“We had things like ‘integrity’ as core values,” says Julie Henne, the company’s director of human resources, “but shouldn’t we always have integrity? So, we asked ourselves, ‘Honestly, what are our core

An engaged and efficient workforce is crucial as the company realigns after a period of expansion and aspires to double its revenues in the next 10 years.

values?’” The company’s leadership, which includes owner Shawn Hunstad and his two sons, Cole, now the company’s vice president, and Jordan, director of operations, came up with three statements: We Show Up. We See the Possibilities. We Make It Happen. — the most important of which is “We Show Up.” The mantra goes beyond just being on the job and paying attention to your work, says Jordan Hunstad. “It’s being engaged with continuous improvement, looking at the processes we have, and seeing what we can do better,” he says. “That’s a big thing for our operators and secondary operators to be fully engaged in what it means to be here.”

An engaged and efficient workforce is crucial as the company realigns after a period of expansion and aspires to double its revenues in the next 10 years. Revolv and its sister company and sales arm, AxisNorth Solutions, are the vision of Shawn Hunstad, who is CEO of both companies. He began as a broker and small manufacturer in the plastic and rubber business, starting in 1995, and has grown it to a company

with joint sales of $42 million. Son Jordan joined the firm in 2012, working in almost every capacity on the production floor before being named director of operations in 2025. Cole Hunstad started in 2015 on the floor as well but soon moved into sales. He currently runs AxisNorth and is vice president of Revolv, with the plan that he will eventually move into the president’s chair. With a goal of growing the joint business to $100 million in 10 years, Hunstad has acquired the equipment, spaces, and employees from two other rotational molders who left the area. Five years after the last acquisition, the company must figure out

they weren’t sure how well it would stand up during a move to Brainerd. Jordan suggested they leave it in Maple Plain and continue to lease the building where it was located. After some ups and downs in the negotiations, the Hunstads acquired the equipment, took over the lease plus a lease in another building, and ended up with two sites in Maple Plain. They also kept most of the company’s employees and — most significantly — its contracts with the U.S. Department of Defense — giving the company a new line of business.

“Within two weeks, we were able to be up and running,” Shawn Hunstad says.

how to merge those operations more fully and create an aligned, excited workforce.

In 2017, Hunstad acquired the equipment and empty 35,000-square-foot facility of Premier Plastics in Hoyt Lakes, which had left the area. Fortunately, many of Premier’s employees wanted to work with Revolv, giving the company expertise in thermoforming as well as rotational molding and a connection to OEMs in the recreational and powersports businesses. Three years later, Shawn and Jordan Hunstad went to Maple Plain to look at some rotational molding equipment that was being sold when another molder left the area. The equipment was solid, but

Aligning systems and building employee skills in lean manufacturing is key to Hunstad’s vision for the company’s future.

Rotational molding is a niche business — you’d be lucky to find 30 vendors at conferences for rotational molders. The process starts with plastic resin pellets that are poured into a mold and heated to up to 600 degrees, then rotated along two axes to spread like lava into the mold. The process is hot, complex, and requires more manual adjustments to heating and cooling times and temperatures than other types of molding. It’s best for producing large parts and products where strength is essential. Rotational molding is not taught in technical programs. Having workers available who were experienced in rotational molding was a great benefit in the acquisitions, Hunstad says.

“They’ve already done rotational mold-

ing,” he says, “but they’ve done it the way they’ve done it. A big push for us is creating what we call the ‘Revolv Way.’ It’s about how we do things at Revolv.”

Aligning systems and building employee skills in lean manufacturing is key to Hunstad’s vision for the company’s future.

“With the facilities we have now, we feel like we can grow sales to the $60 to $70 million range,” he says. “To grow another $30 million beyond that is going to be through more acquisitions.”

Until those opportunities appear, “we want all three plants operating under the same playbook,” he says. “We want everybody doing things the same way.”

The year 2025 is the “year of training” at Revolv, says Henne. “We’re focused on cultivating leadership within our team because our growth ambitions are extremely ambitious. To get from where we are to where we want to be, we need to stay ahead and be well-prepared,” says Henne.

Funded by grants from the State of Minnesota and Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation (IRRR), the company has expanded training in all of its plants. The Hoyt Lakes plant, for example, received training on how to use a new rotary thermoforming machine, which allowed it to fulfill a large contract for consoles for Lund Boats. Two of the plants have ISO certification, with the third certification on the horizon.

management,” he says. “That’s just natural. But it was good to talk it through with them and with (Neale) to see how to deal with these issues.”

“To have the owner/CEO of the company and the HR director in the class — that speaks volumes about the investment in their people that they are making,” Neale says.

Working with Ally Johnston, an Enterprise Minnesota continuous improvement consultant, the company is implementing the Leading Daily for Results program. It’s

This year, the company contracted with Enterprise Minnesota to provide training in both job relations and Leading Daily for Results. Everyone from line supervisor to CEO was trained in job relations, a program that emphasizes the importance of catching and addressing performance issues early, dispassionately, and honestly, says Michele Neale, the business growth consultant with Enterprise Minnesota who conducted the training. It helps employees prevent problems and conflicts from festering and gives supervisors techniques for dealing with issues like attendance, errors, and workplace conflicts in a structured, factual manner.

All three Hunstads plus Henne and other company leaders attended the training along with supervisors and plant managers. It was eye-opening for all, says Cole Hunstad. “There are things that the people on the floor and the production managers deal with that don’t always make it to

The year 2025 is the “year of training” at Revolv. “We want to start growing some leadership among our employees because our growth goals are very, very lofty,” says Julie Henne, the company’s HR director. “In order to get from point A to point B we need to make sure we are on top of things.”

normal for companies with more than one location to have some variations in how jobs are done, says Johnston, but systems like huddle boards and process documentation can smooth out the differences and improve efficiency.

“When you are just one small shop, you can get away with not having certain processes and documentation,” says Jordan Hunstad. “People just know what to do. We’re working to align our processes, get our supervisors talking the same language, and make sure we’re reporting the same documents.”

But it’s a challenge to make processes standard with so much variation in product and equipment as well as the different sizes

of the plants. Hoyt Lakes, for instance, has only 20 employees compared to 40 at Brainerd. All of the products Revolv makes are custom. Many are large. “We ship out a lot of air,” says Jordan Hunstad. Things like Yeti coolers, parts of BOSS snowplows, the front ends of combines, and the little carts children drive around grocery stores are among their products. A new product is the pink housing for robots that deliver documents, packages, and food in some urban areas for a company called Tiny Mile. Many of the jobs also involve assembly as well. For instance, Revolv makes the housing and attaches the wheels to the Tiny Mile robots.

The company continues to look into how automation can streamline processes, though the custom-work can make those investments in automation harder to justify. It is developing its own version of the huddle board, which can be used at all plants. As part of the company’s embrace of Gino Wickman’s Entrepreneurial Operating System, Jordan Hunstad also meets separately with plant managers and procurement managers to address production issues more thoroughly.

“We want to get to the point where everybody in the company has a number that they are trying to hit. And, those numbers relate to our yearly goals,” says Jordan Hunstad. For example, an operator might have a number related to scrap — things like percent of scrap on a project or the value of scrap. Other numbers could be sales dollars or cycle times. Tracking those individual numbers plus team goals will give the company the extra capacity it needs to grow.

“Jordan grew up on the floor,” Henne says. “He understands what is happening on the floor and what really drives our employees.”

And, the company has a reputation in its areas as a good employer, offering good benefits, profit sharing, and bonuses even when there weren’t profits and life coaching and counseling services through a local nonprofit.

An unusual aspect to Revolv is that its sales arm is essentially a separate company that also brokers parts and products for other manufacturers. AxisNorth Solutions is the corporate descendant of Shawn Hunstad’s original business, Stern Industries. Starting in 1995, he built relationships with suppliers who could meet the needs of OEMs for plastic or rubber parts and components. The business continues under the same model, now run by Cole Hunstad, who compares the approach to that of an insurance broker. The broker is getting quotes from various insurances, but they are the customer’s vendor. AxisNorth buys plastic and rubber parts, owns them briefly, then sells them to their client company.

“We’re very transparent with our customers and our suppliers,” Cole Hunstad says. “Our customers know exactly who is making the product for them and they’re more than welcome to go there with us to see samples. It’s very much an open book because our suppliers have learned to trust us and grow with us.”

While that openness has occasionally led customers and suppliers to cut out the middleman, “we don’t lose sleep over it,” says the younger Hunstad. “We build strong relationships with our suppliers and

sometimes their hands are tied too.”

For Revolv, having the brokerage as a sister company has been “a way to control our destiny,” says Shawn Hunstad. It’s a separate source of income, contributing $15 million to the company’s bottom line, as well as a sales representative. It also helps the company build goodwill and form relationships in this small industry.

“We want to give Revolv all the work they want,” says Cole Hunstad. “But if for whatever reason — size, material, quantity, you name it — it’s not a fit for us, then AxisNorth works with our strategic suppliers to find a better fit.”

Those suppliers may include other rotational molders as well as those who do injection molding, blow molding, extrusion, or molded rubber. The company has connections with suppliers doing all of those manufacturing processes, both in the United States and offshore.

This unique business model gives customers a more unbiased assessment of the best supplier for their jobs, Cole Hunstad says. “We’ve been doing this a long time,” he says. “The beauty of it is that we have good suppliers and a lot of them have been with us for 20-plus years.”

With both sons established in the company, patriarch Shawn Hunstad has begun to pull back — at least a little. He still works with chief financial officer Mike Lyonais and Henne, though both now report to Cole Hunstad. He still has the banking relationships and he’s still the visionary. But the day-to-day grind is less his worry.

“So basically, I’ve been trying to prep myself for a retirement of some sort,” he says. That’s still years down the road, but he plans to spend more time in Arizona in

winter. He’s confident the company is on a good track to remain independently owned and in business.

All three have done the Kolbe A Index assessment, which highlights each person’s intuitive strengths as leaders. The elder Hunstad, not surprisingly, fits directly into the visionary category, someone with big ideas who likes to take risks. Son Jordan also fits that category, but has a quieter, more detail-oriented temperament. Cole Hunstad falls more in the integrator category, one who can bring ideas to life.

“He’s always thinking big, big, big, which is great. You need that,” says Cole Hunstad of his father. “I’m kind of, alright, let’s bring it back to reality.”

As company patriarch

Shawn Hunstad begins to pull back — at least a little — the day-today grind is less his worry. His pride in his sons’ abilities and their interest in moving the company forward is palpable. “They could be a powerful combo, those two,” he says.

“We see things differently, all three of us, which is challenging at times,” he says. “But I think it’s good for each of us to — you know — check ourselves. With family, you tend to be more brutally honest than you would be with other people. We don’t take it too personally.”

“We’ve navigated it all thus far and we work really well together. We know what each other’s lanes are,” he says.

Shawn Hunstad’s pride in his sons’ abilities and their interest in moving the company forward is palpable. “They could be a powerful combo, those two,” he says.