ENTRE LES MURS THE DRYSTANE

STORY

Projet de fin d’études

Océane Debard & Camille Piraud

ENSAV

Sous la direction de Magali Paris & Jean-Patrice Calori juin 2024

terme en gaélique écossais désignant la technique de construction par laquelle des murs en pierre sont assemblés sans mortier. Appelée pierre sèche en français et dry stone en anglais.

Ce projet de fin d’études commence par une volonté de regarder le «déjà-là», de le dessiner et de le comprendre. L’ambition est de s’ancrer dans une démarche qui documente cette manière d’étudier l’existant.

Cette démarche est le fruit de nos expériences et différents projets en Italie, en Islande, dans le massif des Écrins ou encore en Angleterre, mais provient aussi d’une inspiration du livre What about vernacular ?, de Justine Lajus-Pueyo, Alexia Menec et Margot Rieublanc. C’est en partie ce livre qui nous a poussé à penser le voyage comme moteur de projet.

Pour focaliser notre recherche sur ce «déjà-là», nos réflexions se sont basées sur un attrait pour la matière et une curiosité autour de la notion de «savoir-faire». Peu à peu, nous nous sommes intéressées à la technique de la pierre sèche, savoir-faire ancestral présent dans de nombreuses régions du monde. Ce savoir-faire nous ouvre alors des perspectives multiples pour notre voyage d’études et c’est finalement l’opportunité de l’Écosse qui se présente à nous puisque nos deux encadrants Magali Paris et Jean-Patrice Calori s’y rendaient avec leurs étudiants de master au début du semestre.

Il était important pour nous, dans le cadre de l’étude d’un savoir-faire, de rencontrer les personnes qui travaillent et connaissent la technique concernée. Nous avons décidé d’organiser et de mener des entretiens filmés durant notre voyage avec Kristie de Garis, John New et Niamh MacKenzie, trois profils différents s’intéressant à cet artisanat, et qui vous sont présentés dans ce livret. Nous avons également participé à un atelier sur la pierre sèche, puisqu’il nous semblait essentiel d’expérimenter de nous-même. Ce livret documente ainsi notre phase d’analyse et notre voyage.

The wall walks the fell Grey millipede on slow Stone hooves; Its slack back hollowed At gulleys and grooves, Or shouldering over Old boulders

Too big to be rolled away. Fallen fragments Of the high crags

Crawl in the walk of the wall.

A dry-stone wall Is a wall and a wall, Leaning together (Cumberland-and-Westmorland Champion wrestlers), Greening and weathering, Flank by flank, With filling of rubble Between the twoA double-rank Stone dyke:

Flags and throughstones jutting out sideways,

Like the steps of a stile.

A wall walks slowly, At each give of the ground, Each creak of the rock’s ribs, It puts its foot gingerly, Arches its hog-holes, Lets cobble and knee-joint

Settle and grip. As the slipping fellside Erodes and drifts, The wall shifts with it, Is always on the move. They built a wall slowly, A day a week; Built it to stand, But not stand still. They built a wall to walk.

Dans le cadre de ce projet de fin d’études, notre approche vise à s’ancrer dans une démarche qui documente et analyse de manière systématique l’existant. Dans cette continuité, nous nous sommes intéressées à la notion de «savoir-faire», cherchant à comprendre les techniques et les connaissances artisanales qui se cachent derrière les objets et les structures que nous observons. Cette analyse cherche ainsi à valoriser le patrimoine matériel et immatériel, tout en offrant une nouvelle perspective sur l’étude de l’existant.

Notre intérêt pour la pierre sèche se place d’abord dans cette démarche plus générale qui s’intéresse à des pratiques de constructions utilisant des matériaux locaux, des pratiques durables. Nous nous sommes donc intéressées à la question du vernaculaire, et la lecture des ouvrages de Bernard Rudofsky ou encore le livre What about vernacular ? nous ont plongées dans cette démarche du regard tourné vers l’existant. Peu à peu, nous avons choisi d’élargir notre domaine d’étude en s’intéressant au sujet du savoir-faire. Pour ensuite préciser le sujet sur le savoir-faire de la pierre sèche.

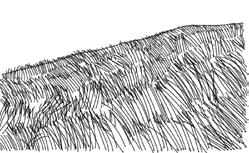

Au-delà d’être un mode de construction vernaculaire, la technique de la pierre sèche est intéressante pour la matière en elle-même. La pierre nous intrigue par l’imaginaire auquel elle renvoie, ce qu’elle représente de son paysage : le paysage imaginé qui renvoie à la formation géologique, et le paysage construit qui raconte un savoir-faire mais aussi une utilisation des territoires à travers l’emploi de la pierre. Finalement c’est la pierre sèche comme composante du paysage qui nous a intéressé.

Nous avons donc choisi l’Écosse comme terrain d’étude nous offrant un territoire inconnu mais riche en découvertes et très attaché au patrimoine de la pierre sèche qui en est par ailleurs un des symboles du paysage écossais.

La démarche de projet s’inscrit donc dans une volonté de documenter le voyage d’études pour que celui-ci soit par la suite moteur de projet. Pour le restituer, nous avons choisi quatre médiums : le dessin, l’écriture, la photographie et la vidéo.

Sur place, nous avons pu observer, pratiquer et parcourir ce territoire de la pierre sèche que nous offrait l’Écosse, par ses murs, enclos et ruines qui ponctuent le paysage. En préparant l’itinéraire de ce voyage nous nous sommes intéressées au patrimoine de la pierre sèche présent en Écosse et avons répertorié différentes typologies. L’itinéraire du voyage est alors guidé par ces différents types de constructions en pierre sèche et finalement nous donnons le nom de «drystane road» à cette route qui nous y mène.

La restitution de ce voyage prend alors la forme de ce livret et d’un film appelé ON THE DRYSTANE* ROAD (QR code en page 4), et retracent notre parcours et les différents entretiens que nous avons menés.

Il s’agit, par ce livret, de développer l’imaginaire et le paysage dans lequel nous nous implantons pour ce projet. Nous développons alors une courte introduction sur la pierre sèche, pour plus tard raconter notre voyage et les différentes rencontres que nous avons pu faire. Ensuite, nous tâcherons de développer la technique de la pierre sèche que nous avons mise en œuvre lors d’un workshop pour l’étudier au travers des typologies écossaises que nous avons explorées. Enfin, nous chercherons à introduire différentes problématiques et hypothèses qui nous ont permis de choisir notre terrain d’études et développer le projet.

Pour revenir brièvement sur le savoir faire de la pierre sèche, celui-ci est reconnu par l’UNESCO depuis 2018 comme patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité. C’est un mode de construction qui ne nécessite que quelques outils et le matériau lui-même généralement à l’état brut. Le mur en pierre sèche est le fruit de l’empilement, la disposition intelligente de chaque pierre et ne nécessite aucun liant ou matériau supplémentaire. Cela en fait un mode constructif qui ne produit aucun déchet et qui est réutilisable à l’infini.

Pour résumer son mode constructif nous pouvons établir trois étapes : la pose de fondation, aussi appelée semelle, avec des pierres semi enterrées, le montage du mur avec du fruit et un remplissage intérieur avec des pierres de plus petite taille, puis le couronnement avec la pose de pierres plates ou arrondies.

C’est également un mode de fabrication de murs qui favorise le développement d’une biodiversité permis par la présence d’interstices entre les pierres et par l’humidité de l’eau de pluie ruisselant contre les parois du mur. Les moutons, vaches et oiseaux apprécient également ce type de mur, venant s’y protéger lors de fortes pluies ou de vent particulièrement violents.

On retrouve l’utilisation de la pierre sèche pour des murs ou des édifices dans de nombreuses régions du monde. Souvent liées à des pratiques agricoles, les constructions en pierre sèche sont parfois créatrices du paysage, notamment avec l’utilisation de murs de soutènement pour créer des terrasses, ou bien séparer des parcelles.Dans certaines régions du monde, l’utilisation de la pierre sèche se rapproche fortement de la stéréotomie, c’est le cas par exemple en Amérique du sud où la civilisation inca ont bâti de grandes cités en pierre sans liant permettant le mouvement des pierres lors de léger séismes et évitant ainsi l’effondrement.

L’utilisation de la pierre sèche est aussi connue pour ses qualités thermiques, protégeant du vent mais aussi avec une bonne inertie thermique. (de haut en bas) Temple à

Notre voyage débute avec cette volonté d’étudier la pierre sèche. Un artisanat présent partout dans le monde, nous demandant de faire un choix quant au site à explorer. Nos encadrants de PFE travaillant sur un sujet en Écosse avec leurs étudiants de master, nous profitons de cette occasion pour rejoindre leur site d’exploration, la technique de la pierre sèche y étant particulièrement présente. Notre itinéraire est guidé par les rencontres et les visites en lien avec notre sujet d’étude. En résulte un voyage intense de 8 jours où nous passons chaque jour et chaque nuit dans un nouveau lieu.

JOUR 01 : Le voyage commence avec une arrivée à Édimbourg le jeudi après-midi et une première et rapide visite de la ville.

JOUR 02 : Vendredi, nous commençons par un trajet d’une heure et demie vers le Perthshire, où nous avons fait la rencontre de Kristie de Garis pour un entretien au sujet de sa pratique de cet artisanat (voir page 20) Nous passons le reste de la journée à Édimbourg, avant de reprendre la route pour une heure et demie, direction Glasgow.

JOUR 03 : Le samedi, non loin dans la campagne à l’ouest, nous passons une journée à Auchenfoyle pour participer à un workshop avec la West Scotland Dry Stone Walling Association, consistant à la réparation d’un mur en pierre sèche qui sépare les parcelles d’un fermier. Ce workshop nous a permis de rencontrer John New, président de l’association, puis d’effectuer avec lui un entretien (voir page 20). La journée se clôt par une visite de Glasgow.

JOUR 04 : Dimanche, notre périple se poursuit dans les Highlands, à travers les paysages montagneux recouverts de végétation encore jaunie par la neige, nous croisons des moutons et des cerfs en bord de route. Nous effectuons un arrêt à Glencoe pour visiter la reconstitution d’une turf house (voir page 42). Nous terminons la journée à Fort Williams.

JOUR 05 : Lundi, nous continuons notre chemin jusqu’à Uig au bout de l’île de Skye, lieu de départ de notre ferry pour l’île de Lewis. Nous entrons dans le ferry à bord de notre voiture, puis sortons sur le pont afin de profiter de l’air marin et du paysage à perte de vue qui s’offrait à nous pour ce trajet d’une heure et demie. Ce sentiment d’immensité et d’horizon infini nous aura suivi dans les Highlands et jusqu’au bout du continent sur l’île de Lewis. L’arrivée sur cette île marque un tournant dans notre étude et notre voyage. La pierre sèche y est omniprésente. Le trajet en voiture est simple, une seule route nous guide vers la côte pour atteindre le Broch de Carloway (voir page 46). Nous traversons des champs et des petits villages. Les ruines en pierre sèche ponctuent le paysage, étant parfois utilisées par les habitants et d’autres laissées à l’abandon. Nous visitons quelques black house (voir page 50), ainsi que quelques ruines puis nous nous rendons à Stornoway pour y passer la nuit.

JOUR 06 : Mardi, nous reprenons le ferry pour deux heures et demie en direction d’Ullapool. Nous poursuivons en voiture direction le célèbre Loch Ness avant de passer la nuit à Inverness.

JOUR 07 : Mercredi, retour à Edimbourg avec une escale au Highlands Folk Museum, un musée à ciel ouvert où diverses architectures vernculaires du territoire des Highlands sont reconstituées, allant du XVIIIe siècle au milieu du XXe siècle. Nous retrouvons ensuite Édimbourg pour notre dernière rencontre qui s’effectue avec Niamh MacKenzie dans les jardins botaniques (voir page 24)

JOUR 08 : Jeudi, dernier jour, nous faisons une dernière visite d’Édimbourg avant de faire nos au revoir à l’Écosse et de rentrer en France, les carnets remplis, de nombreuses photos, vidéos et une hâte de réaliser une restitution de ce riche voyage.

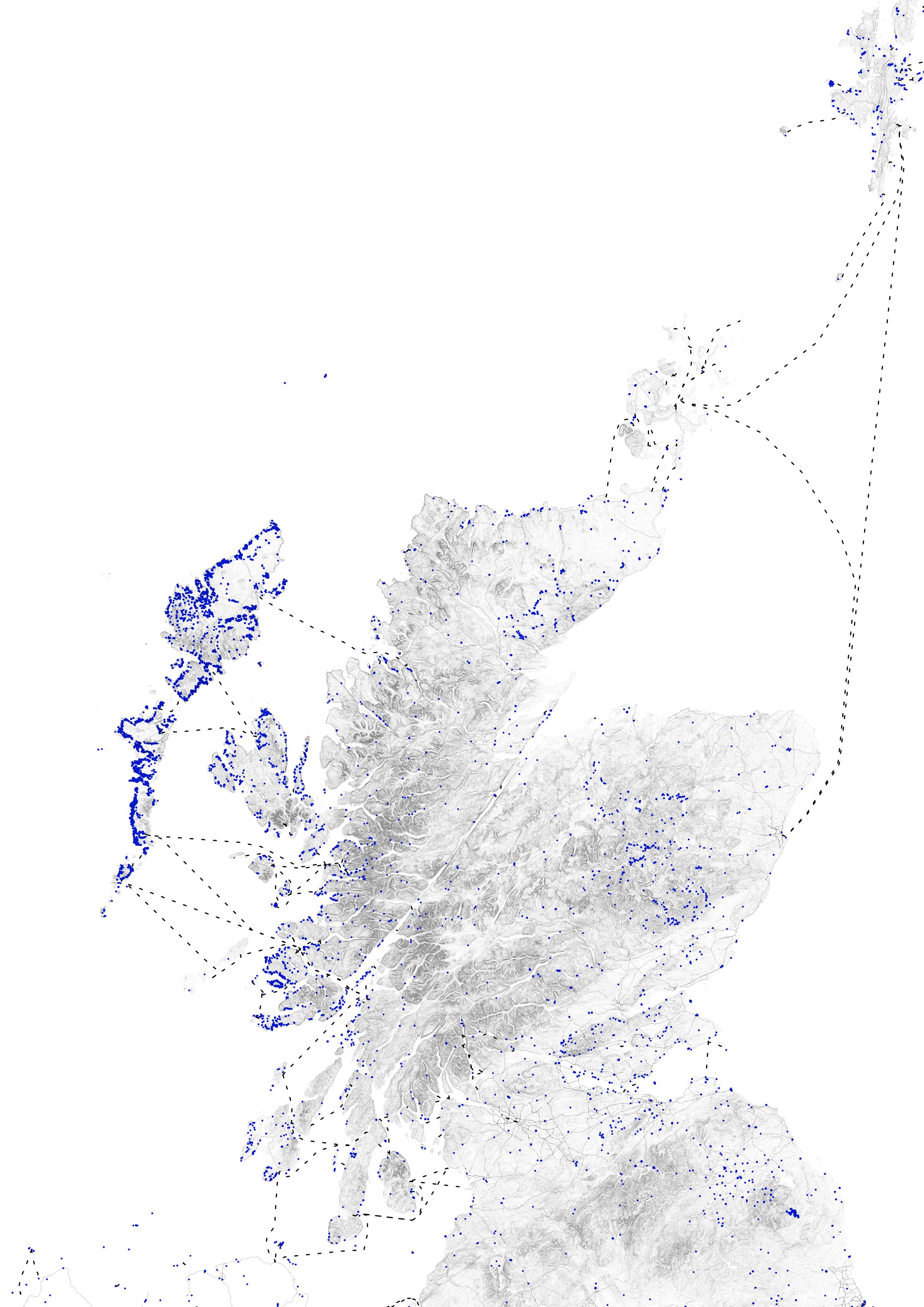

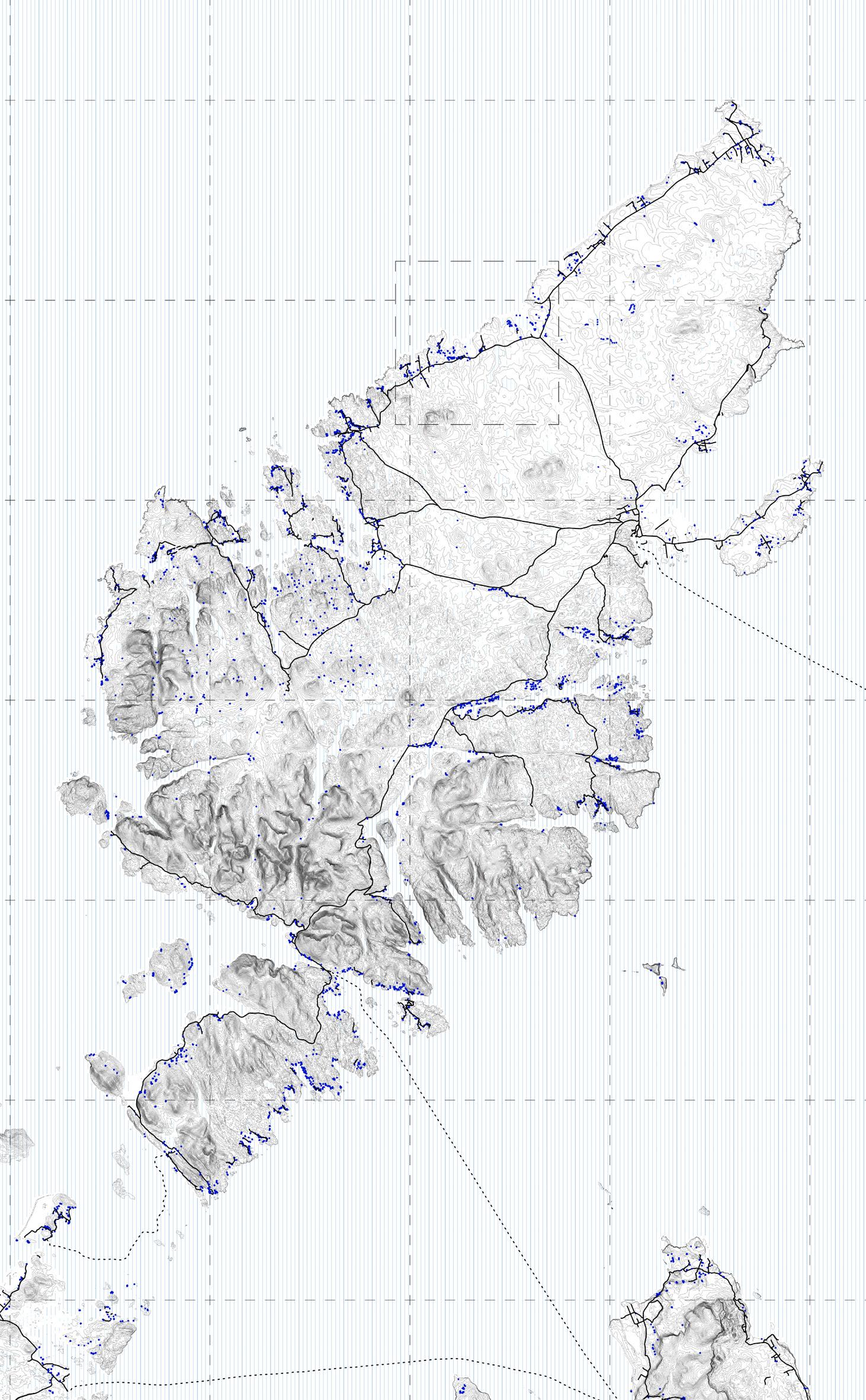

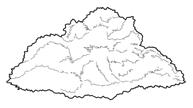

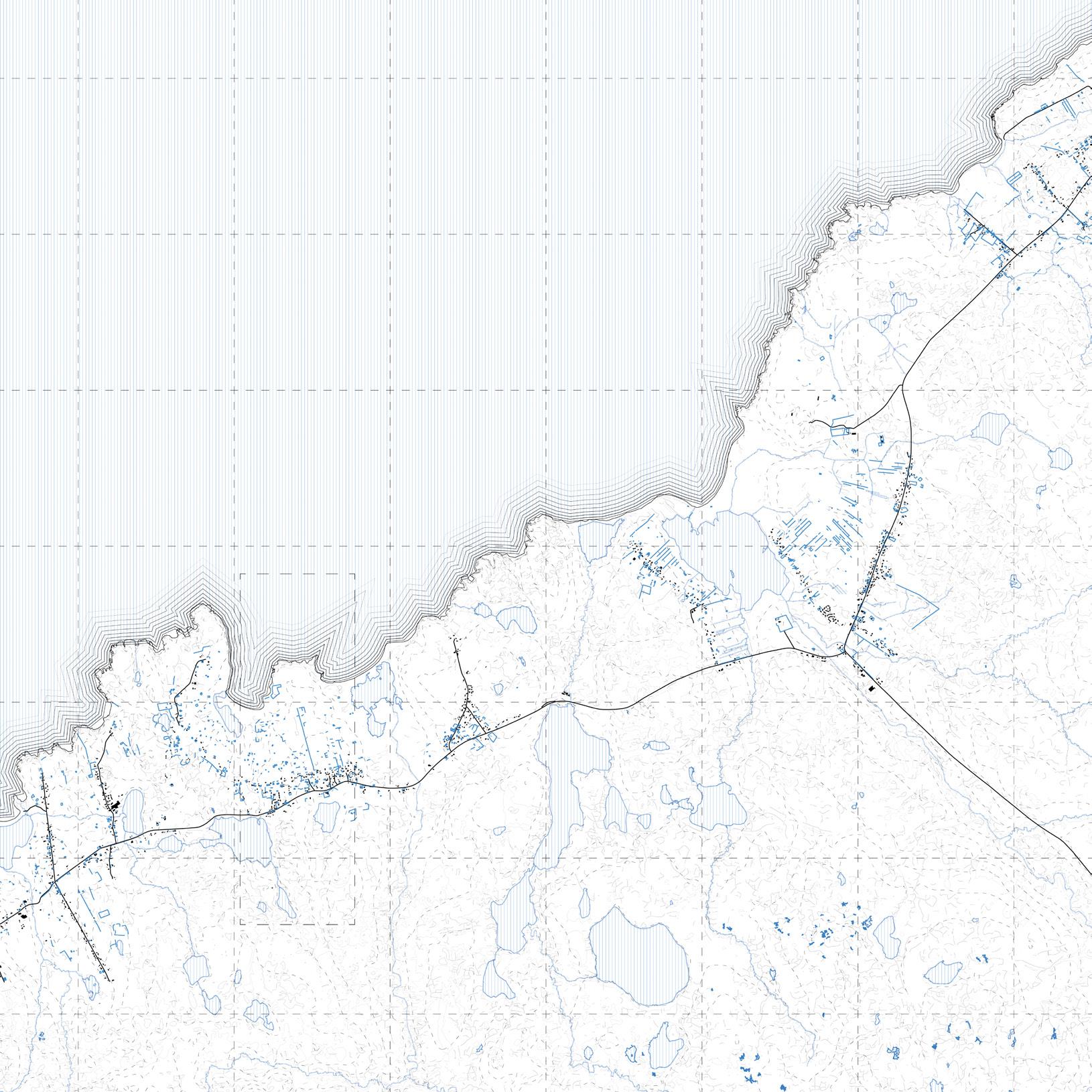

Ci-contre : Carte de l’itinéraire du voyage

«Je n’aime pas juste la pierre sèche, j’aime la pierre. J’aime tout de cette technique. Ce travail est incroyablement méditatif et thérapeutique pour moi.»

Kristie De Garis est ce qu’on appelle dans le milieu de la pierre sèche une muraillère (waller en anglais). Elle possède une entreprise de construction en pierre sèche The Dry Stone Company avec Luke De Garis, située à Perth dans le comté du Perthshire à une heure et demie au nord d’Édimbourg en Écosse. Passionnée par la pierre en général et les paysages écossais, elle est aussi auteure et photographe.

Lors de notre voyage, nous avons retrouvé Kristie sur l’un de ses chantiers à proximité de la ville de Perth où elle habite. Il s’agissait de la construction d’un mur en pierre sèche permettant de clôturer les limites de la propriété des clients. Durant cet entretien de 20 minutes, Kristie nous a parlé de sa pratique en tant que muraillère. De sa démarche, ce qui l’a poussé à faire ce métier, comment elle s’est formée elle-même en construisant des murs dans son jardin, à la difficulté de se former à cet artisanat en tant que femme et de l’importance de ces constructions pour le paysage et la mémoire collective.

Entretien complet en page 78

«Bien qu’il semble simple de regarder quelqu’un faire un mur en pierre sèche, la compétence réside en réalité dans l’œil de l’artisan qui va trouver la bonne pierre.»

John New est le président de la branche Ouest de l’association Scotland Dry Stone Walling Association depuis 20 ans. Il est également le patron d’une entreprise de paysagisme depuis 35 ans, ce qui lui a permis découvrir l’artisanat de la pierre sèche. La plupart des workshops ont lieu sur des terrains de fermiers et agriculteurs où ils rénovent les murs séparant des parcelles.

Nous rencontrons John New lors d’un workshop auquel nous avons participé à Auchenfoyle à 30 minutes de Glasgow. Nous avons passé la journée à construire un mur en étant guidées par lui et les autres membres de l’association. Lors de notre échange, John nous a surtout parlé de l’importance pour lui de transmettre et former des gens à cet artisanat, que ce soit dans un but privé ou professionnel. Il nous a aussi parlé de sa fascination pour ces murs résistant au temps et aux intempéries, des différentes possibilités constructives offertes par cette technique et des qualités environnementales de la pierre sèche pour la biodiversité notamment.

Entretien complet en page 82

«Il s’agit d’histoire et de patrimoine. Une fois que le mur en pierre sèche est présent depuis longtemps, il commence à devenir un foyer pour toutes ces mousses et lichens, il devient une partie intégrante du paysage et on ne peut plus imaginer qu’il ne soit plus là. C’est cela qui lie les gens à l’endroit qu’ils habitent.»

Niamh MacKenzie est étudiante à l’Université des Highlands et Islands (UHI) à Édimbourg où elle prépare son doctorat sur la pierre sèche et sa relation avec le patrimoine culturel immatériel. Elle tient son attachement pour la pierre sèche de son enfance passée dans le nord de l’Écosse où les murs en pierre sèche font partie du paysage au point où on ne les remarque presque plus, avant de retrouver ce thème au cours de ses études.

Lors de notre rencontre au jardin botanique d’Édimbourg, nous avons pu échanger avec Niamh au sujet du classement de cet artisanat de la pierre sèche au patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’Unesco et de l’impact positif que cela peut avoir sur la compréhension de cette technique et la manière dont les communautés l’utilisent pour leur propre type de développement durable et de développement des compétences sur ce sujet. Nous avons également parlé des différents ateliers auxquels elle a eu l’occasion de participer, de la manière dont, d’une région à une autre, l’apprentissage a pu être très différent et de la manière dont elle espère participer à la préservation des sites historiques et patrimoniaux d’Écosse dans sa future pratique professionnelle.

Entretien complet en page 87

L’un des principaux avantages de la pierre sèche est de ne pas vraiment avoir besoin d’outils pour la construction d’un mur, sauf dans les cas où les pierres sont trop lourdes ou s’il y a la volonté de tailler les pierres dans un but esthétique ou autre.

Dans ces cas là, ciseau, poinçon, maillet à tête concave, marteau à pointe, massette carrée, massette carrée aux arêtes vives, coin diviseur pour le grès, corde, pelle ou encore balle de tennis sont différents outils qui peuvent être utilisés sur les chantiers de pierre sèche. Il s’agit d’outils assez communs, mais il arrive que certains muraillers développent leurs propres outils. C’est le cas de l’association avec laquelle nous avons fait le workshop qui, avec un ferrailleur du coin, a développé l’outil visible sur la troisième photographie ci-bas qui sert à tenir les cordes qui font office de guides afin d’avoir un fruit régulier de chaque côté du mur.

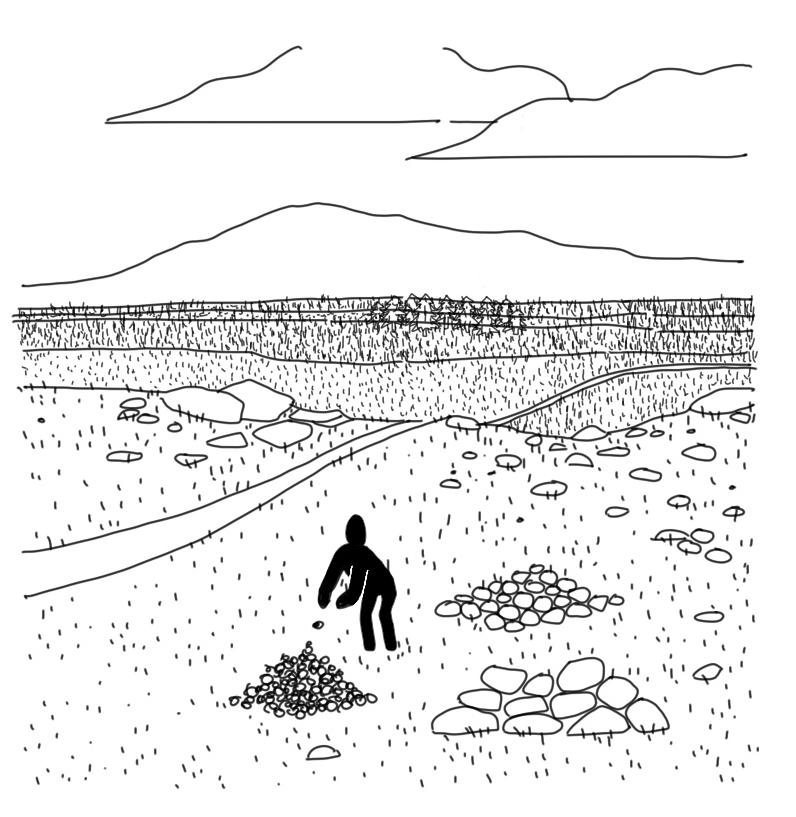

L’idée de faire de nos mains était importante pour nous, c’est pourquoi nous avons donc pris la route vers Auchenfoyle afin de participer à un workshop encadré par la West Scotland Dry Stone Walling Association. Nous avons pu participer à la réparation d’un mur en pierre sèche séparant les parcelles d’un fermier. Sur place nous avons appris de manière élémentaire comment trier les pierres, réaliser les fondations et monter le mur avec la technique du hearting, en plaçant des pierres de plus petite taille au cœur du mur.

Nous étions encadrées, avec les autres participants, par John New et ses collègues, nous donnant des instructions et conseils pour veiller à la bonne pose des pierres. Lors de ce workshop, nous avons appris une certaine technique pour réaliser un mur en pierre sèche, mais les techniques peuvent varier d’un pays à l’autre, d’une région à l’autre, voir d’un murailler à l’autre, et s’adapte selon le type de pierre disponible.

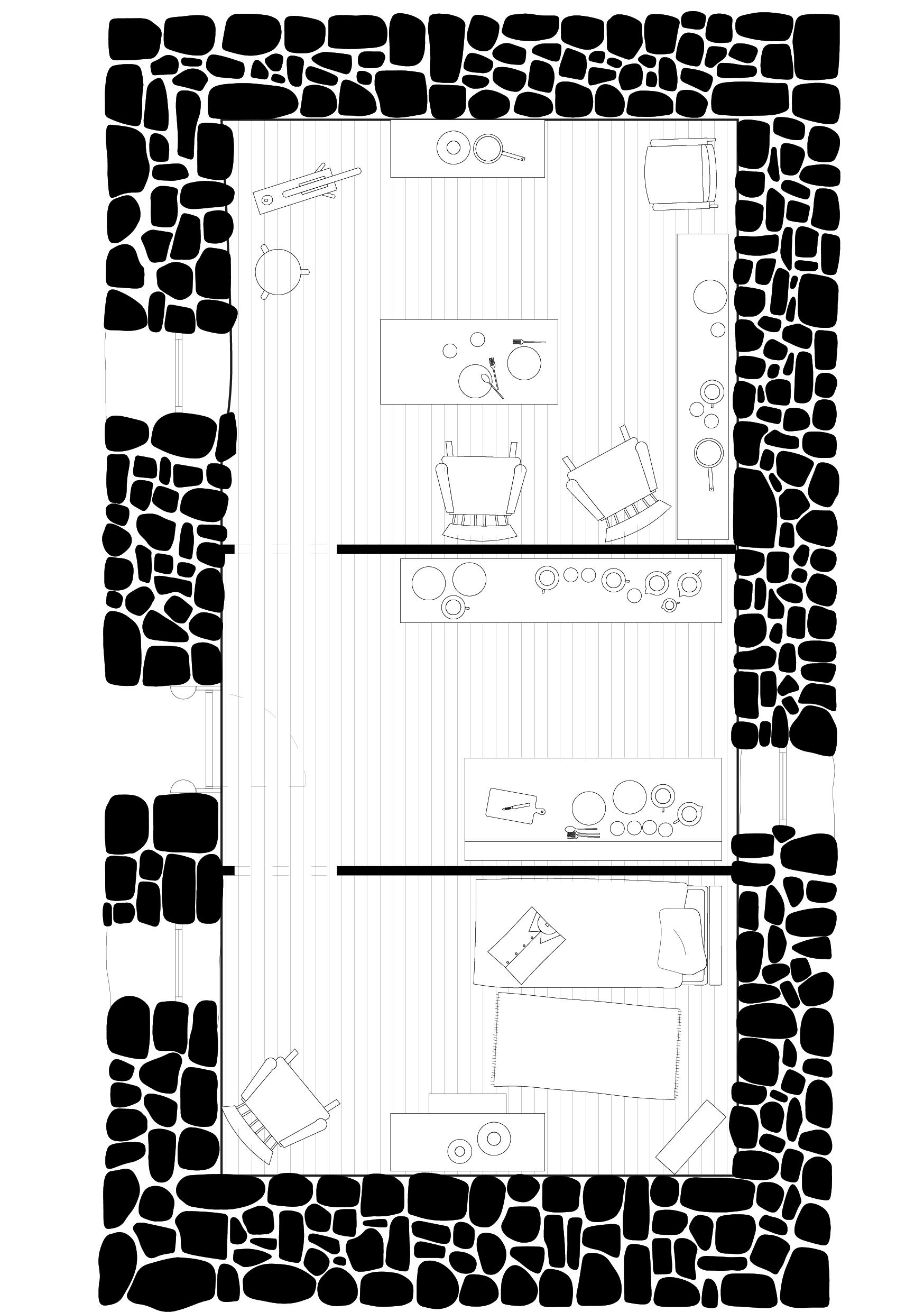

La pierre sèche est une technique de construction de murs en pierres assemblées sans mortier selon un savoir-faire répandu mondialement, principalement dans la plupart des zones rurales et sur les terrains accidentés. Cette technique peut connaître des variations d’un pays à un autre, voire même d’une région à une autre. Il s’agira ici de réaliser un mode d’emploi de la construction en pierre sèche selon le modèle général écossais observé in situ.

ETAPE 01/

Les pierres formant le mur sont généralement récupérées sur les terrains voisins, on appelle cela l’épierrement. La première étape consiste donc à récupérer autant de pierres disponibles que nécessaire, pour les trier ensuite selon leur forme, leur taille et leur couleur afin de faciliter leur sélection lors de l’assemblage du mur.

ETAPE 02/

Il s’agit ensuite de délimiter l’épaisseur et la longueur de mur souhaitées. On commence alors à creuser quelques centimètres dans le sol pour marquer les limites du mur et permettre aux premières pierres posées d’être légèrement enterrées comme des fondations, c’est ce que l’on appelle la semelle. On peut alors commencer à poser ces premières pierres qui sont généralement les plus imposantes.

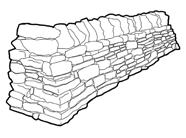

ETAPE 03/

Une fois la première rangée de pierres posée, on peut commencer à monter le mur. Pour cela on s’aide de « guides » qui sont des bâtons plantés tout le long du mur, reliés par des cordes, aidant à respecter le fruit du mur nécessaire au maintien de celui-ci et à l’écoulement de l’eau sur les deux pans. Chaque pierre est posée selon sa taille et sa forme afin que chacune d’elles trouvent sa place et maintiennent au mieux le mur. Les pierres peuvent parfois être taillées, ce n’est généralement pas le cas en Écosse où chaque pierre est utilisée telle quelle. Il existe différente manière d’assembler un mur en pierre sèche, selon les besoins, l’esthétique désirée ou le type de pierre disponible ; dans ce cas là les pierres les plus grosses sont sélectionnées afin de créer les deux pans de murs et le remplissage se fait avec les pierres les plus petites afin de consolider la construction. Il est possible également de poser une pierre sur toute la profondeur du mur, c’est ce que l’on appelle une boutisse.

ETAPE 04/

La corde est ainsi remontée à chaque fois que la limite est atteinte jusqu’à atteindre le haut du mur appelé couronnement. Il existe également différents types de couronnement, soit avec des pierres plates ou arrondies afin de favoriser l’écoulement de l’eau sur chaque pan du mur.

ETAPE 05/

On peut enfin retirer les guides et profiter du mur pour des années.

L’approche du territoire par le biais de la pierre sèche, permet de relever les typologies de construction en pierre sèche et de voir les concentrations sur le territoire.

La carte ci-contre cherche à mettre en valeur ces concentrations de certaines typologies ainsi que le schéma d’implantation de celles-ci.

On observe que les broch se trouvent plutôt sur les côtes, certainement avoir un accès à la mer et prévenir de l’arrivée des bâteaux. Cet emplacement fait qu’ils sont aussi exposés aux vents d’où l’utilisation de la pierre sèche pour une protection efficace contre ceux-ci tout en laissant en partie passer l’air entre les pierres et permettant un effort au vent moins grand. Les black house et round house se trouvent uniquement sur les îles de Lewis et les Orcades, là où il y a le plus besoin de s’abriter du climat hostile. Dans le reste du pays et principalement dans les terres, on observe d’autres types de constructions en pierre sèche, tels que les cairn, les turf house et différents types de bâtiments liés à l’agriculture ou à l’élevage avec généralement des murs moins épais.

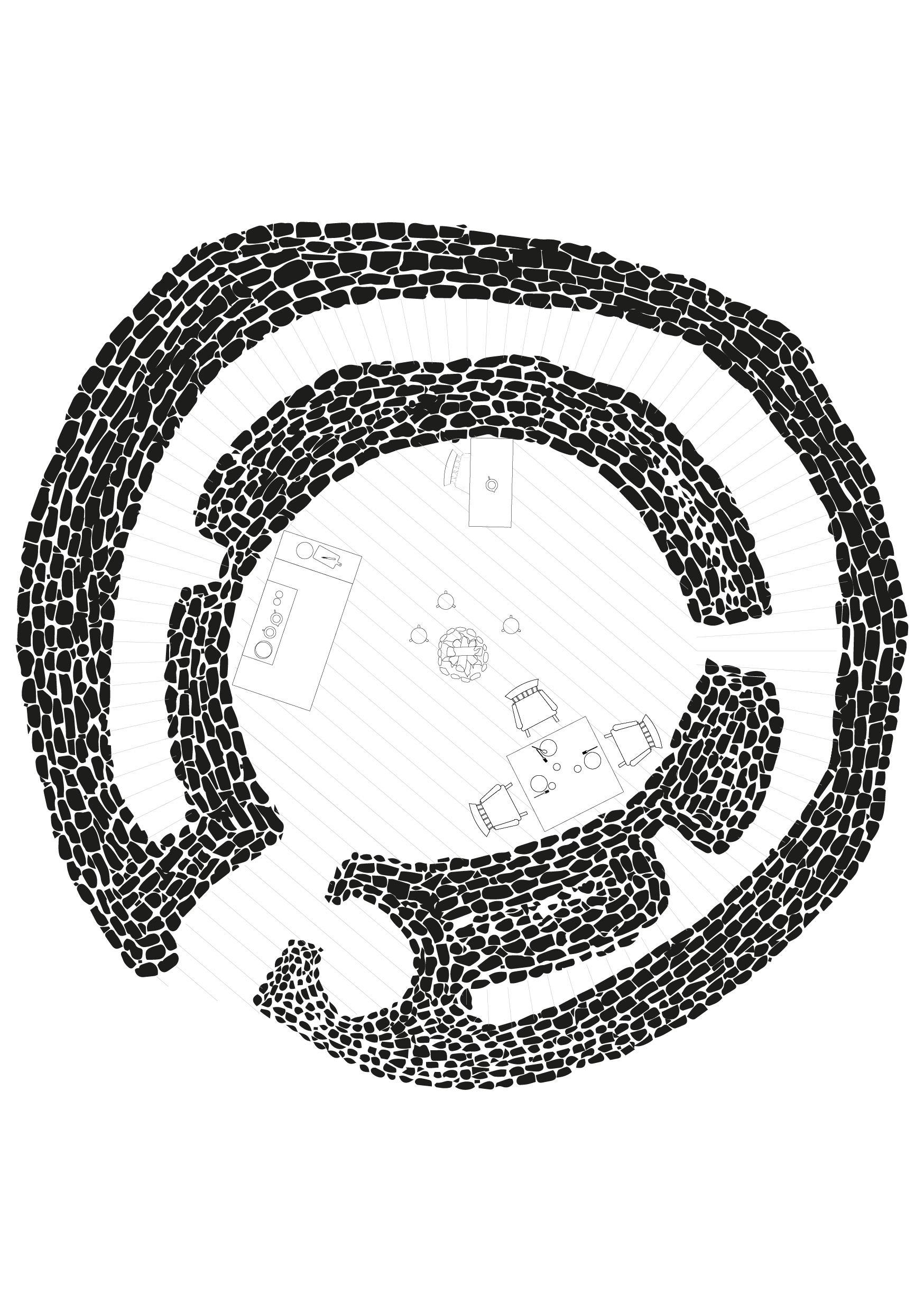

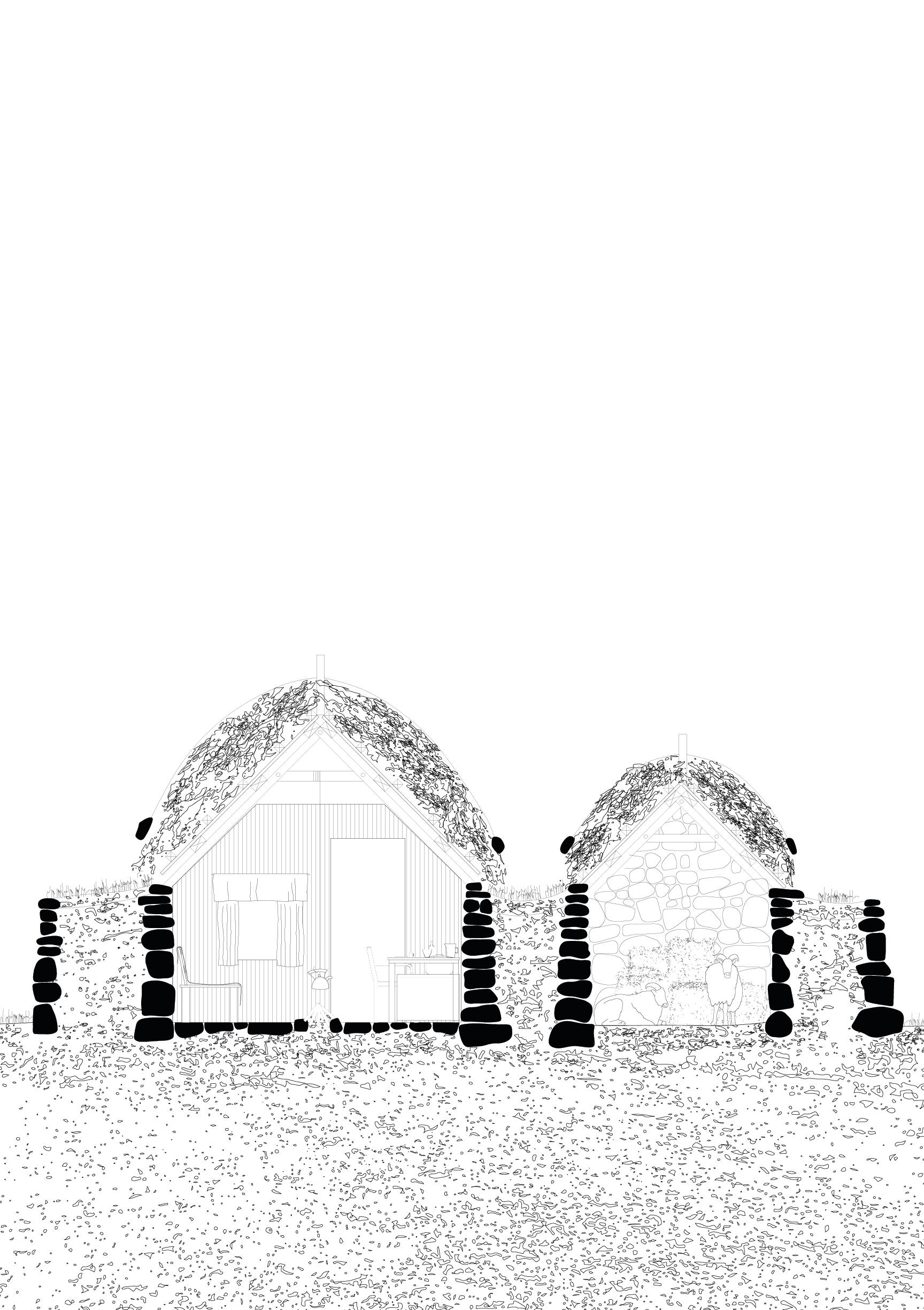

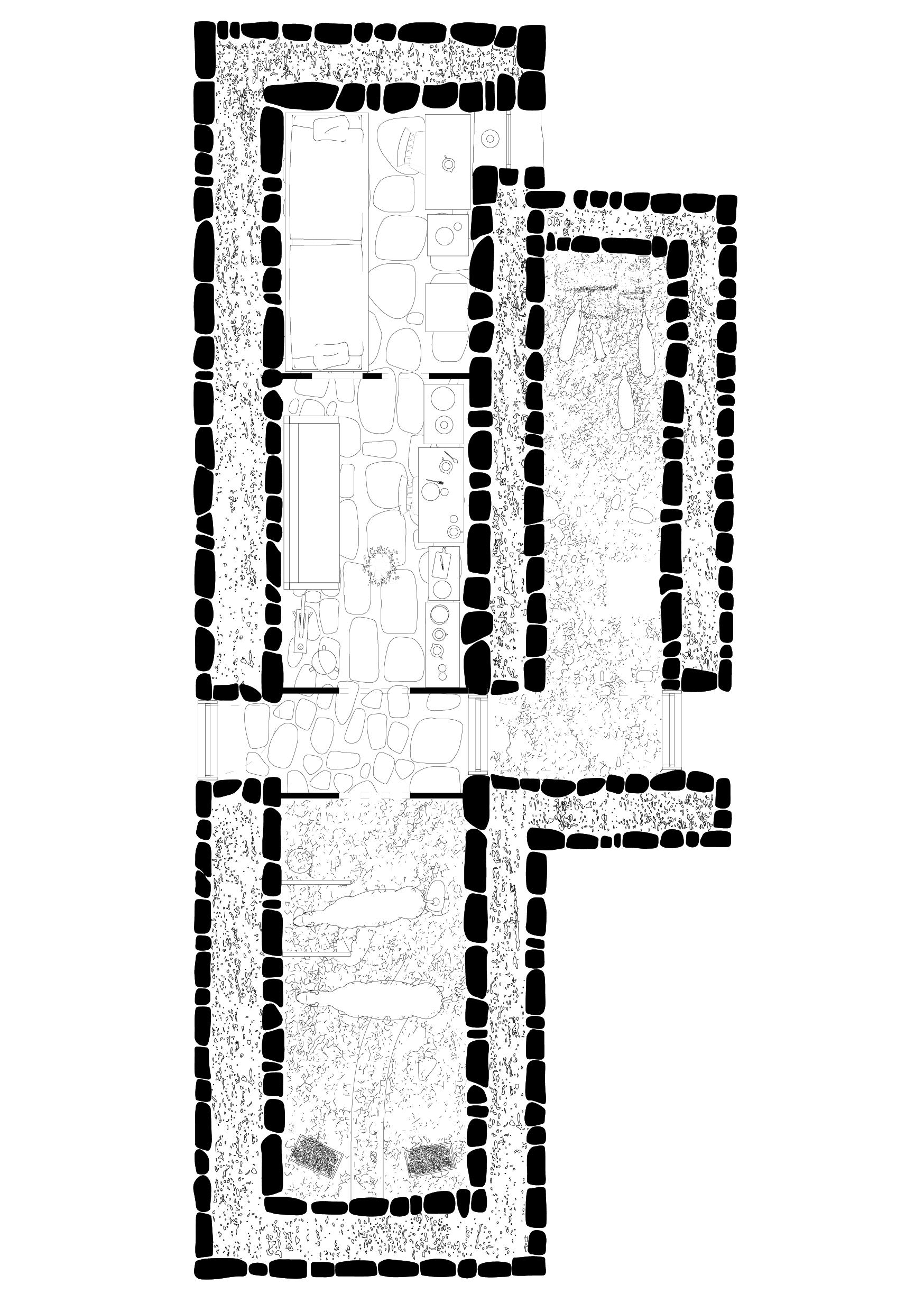

Finalement, le terrain d’étude de l’Île de Lewis, recentre l’étude des typologies sur celles que l’on a pu voir et visiter : la turf house, le broch, la black house et la croft house. Nous avons ainsi redessiné les plans et coupes types de ces modèles architecturaux afin de mieux les comprendre.

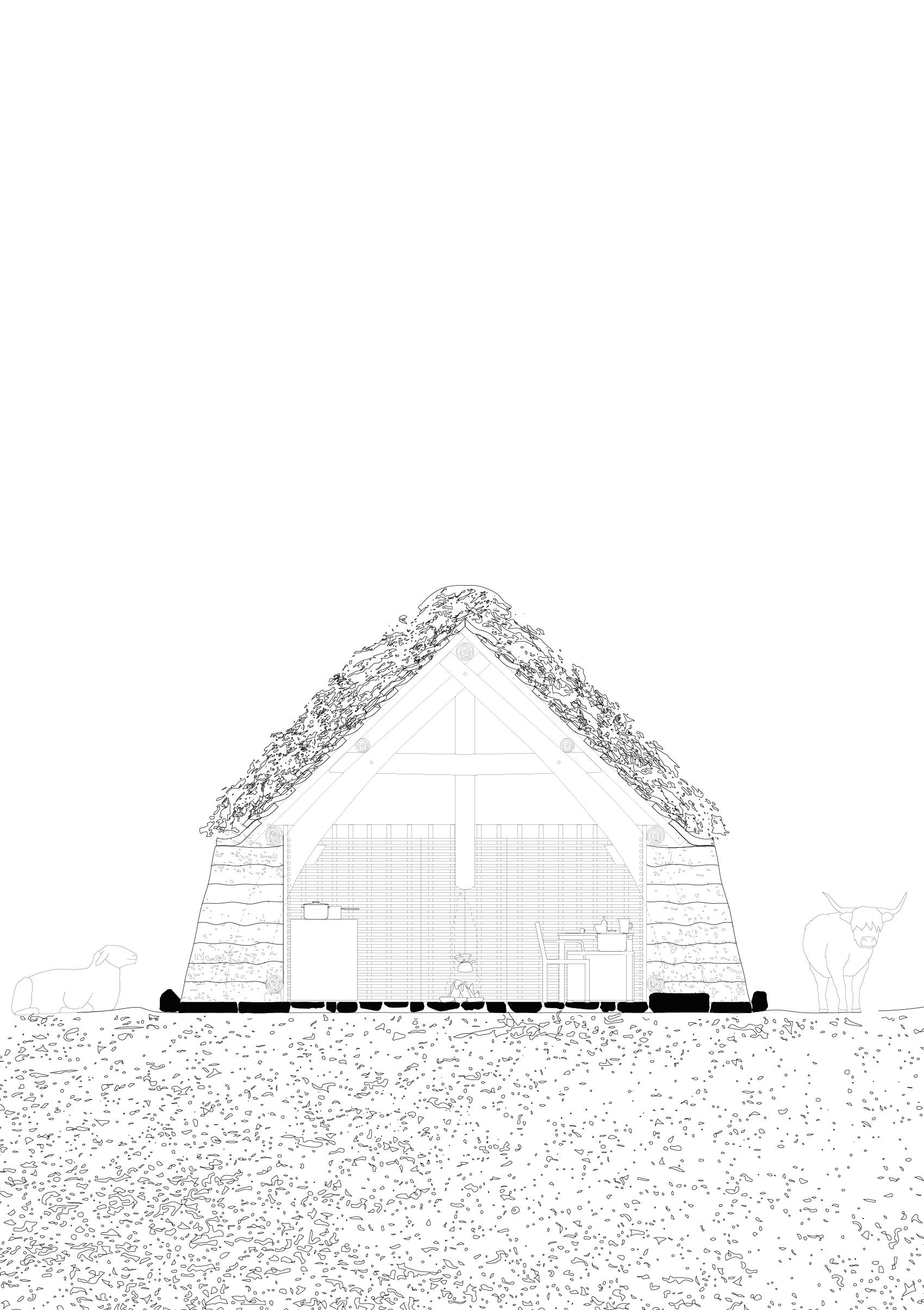

Les turf house sont des maisons de 10,5 m de long sur 4 m de large à usage d’habitations ou granges datant du XVIIème siècle. Les murs étaient épais de 80 cm à 1 m. Dans le cas de cette reconstruction de 2021 à Glencoe, la charpente est en bois d’acacias, les fondations en pierre et les murs en brique de tourbe consolidés d’un cadre intérieur en osier tissé comme un panier. C’est pourquoi cette turf house particulièrement est appelée turf and creel house (creel désignant l’osier) . La charpente est recouverte d’une couverture en bouleau et d’une fine couche de gazon sur laquelle est fixé du chaume de bruyère. Le faîtage du toit est recouvert de torchis et de tourbe. La maison compte une fenêtre avec une « vitre » en peau de chèvre tendue. Cette turf house peut être visitée aujourd’hui au Glencoe National Nature Reserve.

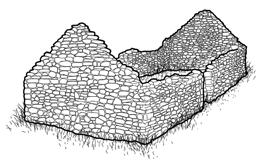

Aussi appelé dun, les broch sont des tours massives en pierre sèche au plan rond. La plupart de ces constructions datent du début de l’âge de fer britannique (1er siècle après J.-C.) et auraient été habitées jusqu’au milieu de la période médiévale. Le dun de Carloway servait de tour défensive et est située sur une colline de la côte ouest de l’île Lewis. D’abord des round house, avec le temps ces constructions grandissent en taille et en complexité pour devenir des forteresses appelées broch. Constituées d’une double paroi, de deux étages, d’un espace central et d’espaces individuels contiguës, les broch pouvaient atteindre jusqu’à 15 m de haut et 15 m de large. Les murs, intérieurs et extérieurs, avaient une épaisseur d’1,5 m chacun, séparés d’un espace d’1 m dans lequel un escalier donnait accès aux différents niveaux. Ce creux servait également à aérer les murs et isoler l’espace intérieur. La structure de ces escaliers et galeries disposés à intervalles réguliers, permettaient de stabiliser l’édifice. Les toitures coniques sont recouvertes de chaumes, les poteaux de support reposent sur les murs de pierre, ou directement sur le sol pour les plus petites roundhouse. Il n’y avait pas de fenêtre et une seule entrée. L’espace intérieur contenait généralement un foyer central, une citerne, un puit ou une source.

Le broch de Carloway est aujourd’hui sous la tutelle de l’Historic Environnement Scotland, et se trouve sur un terrain appartenant à une propriété foncière communautaire, la Carloway Estate Trust depuis 1880.

La black house est un ancien type d’habitation rurale à pièces multiples, avec une partie pour les animaux et une partie pour les hommes. La black house d’Arnol située sur l’île de Lewis que nous avons visitée, fut construite en 1885 et habitée jusqu’en 1965 avec le déménagement des populations vers les white house, évolution de la black house.

La black house est faite de murs en boue avec un parement en pierre sèche, imperméabilisé au niveau du mur principalement exposé avec de l’argile bleue protégée par une couche de tourbe. Le gazon est disposé en couche fine à la base du toit, formant un substrat pour le chaume, lui-même appliqué sur une surface à lattes. Le sol des pièces à vivre de la maison est pavé et rejointoyé d’argile bleue. Le foyer et les sols de la grange et de l’étable sont en terre cuite. La structure du toit est presque entièrement constituée de bois flotté ou bois provenant d’épaves, disposé dans ce cas en A-frame. Les toits prennent généralement une forme arrondie du au chaume disposé dessus, et sont encordés de manière à résister aux vents forts de l’Atlantique.

Le terme croft fait référence en Écosse à une petite parcelle agricole sur laquelle le fermier a généralement sa maison, appelée croft house. Le fermier est appelé crofter.

La croft house, est un lieu d’habitation rural très similaire à la black house, excepté qu’elle est à pièce unique, et les murs pignons en pierre sont surmontés de tourbes afin d’avoir une charpente surélevée et donc une hauteur sous plafond plus haute. La croft house est généralement plus confortable que la black house, par ses murs de tourbes recouverts d’un bardage bois, d’un parquet au sol et de ses cheminées aux extrémités. Il est possible de visiter de nombreuses croft house reconstituées en Écosse.

Les différentes rencontres avec les acteurs de cet artisanat, la pratique et les visites de différentes constructions traditionnelles en pierre sèche nous ont permis de mieux appréhender le projet, de mieux comprendre l’importance et l’attachement des écossais pour cet artisanat. Cela nous a aussi fait prendre conscience des difficultés à promouvoir cette technique dont les méthodes de construction peuvent être lentes, coûteuses et nécessitent une main d’œuvre rare.

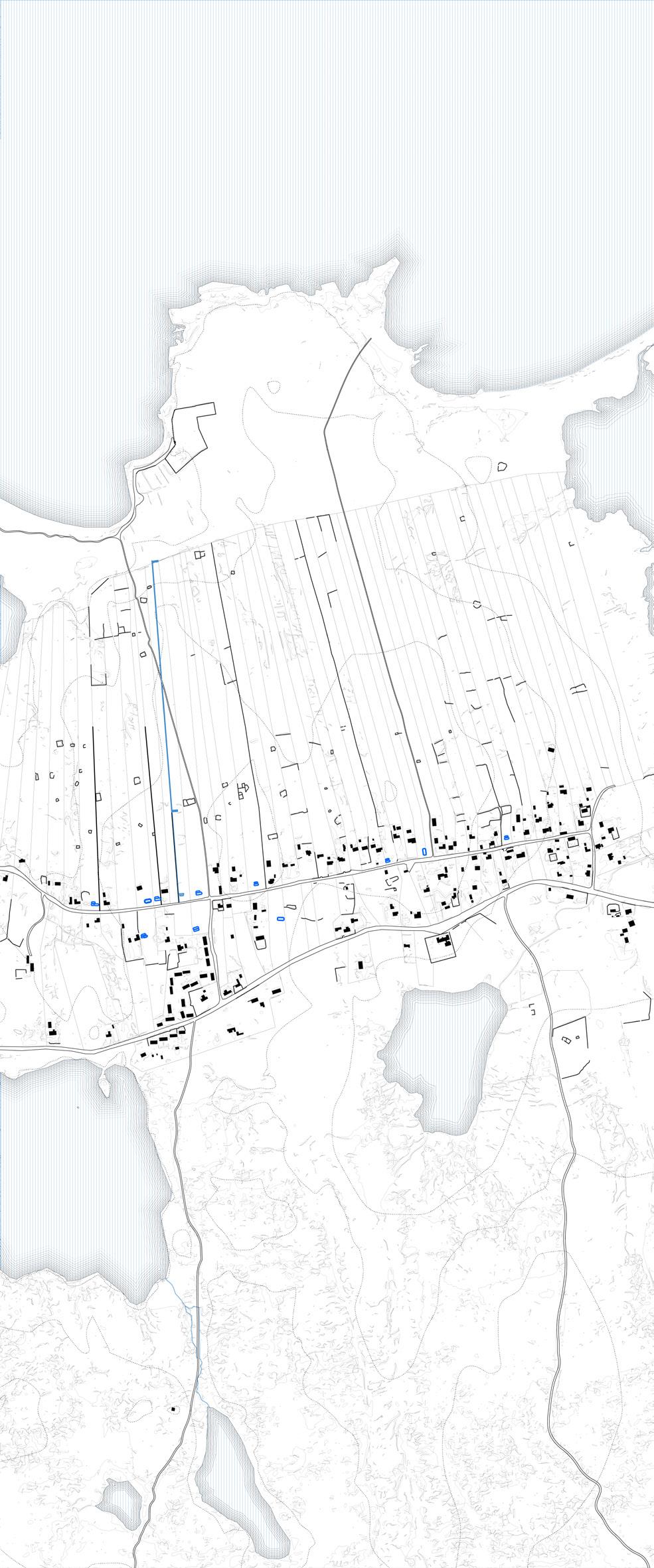

Lors de ce voyage, nous sommes toutes les deux particulièrement marquées par notre séjour sur l’île de Lewis. Cette île au nord-ouest de l’Écosse faisant partie des Hébrides extérieures, s’est illustrée pour nous par la forte présence des ruines et murs en pierre sèche venant scarifier le territoire. En effet, l’île compte plus de 3500 ruines représentant 20% du bâti total. Les insulaires vivent au milieu de ces ruines qui se trouvent parfois dans leur jardin et qu’ils se réapproprient plus ou moins. Notre première intuition a donc été de faire une collection photographique de ces ruines (voir page 64), ce qui nous a permis de constater qu’il s’agit pour la plupart d’anciennes black house ou croft house qui ont été délaissées pour les plus modernes et confortables white house. Nous avons ensuite réalisé des cartes de l’île afin de se rendre compte de l’implantation de ces ruines, nous permettant d’observer que ces dernières se situent en majorité sur les littoraux et tout le long de la route principale que nous avons empruntée. Les quelques villages de l’île se sont construits autour de ces densités de ruines, représentant pour nous, des potentiels sites de projet.

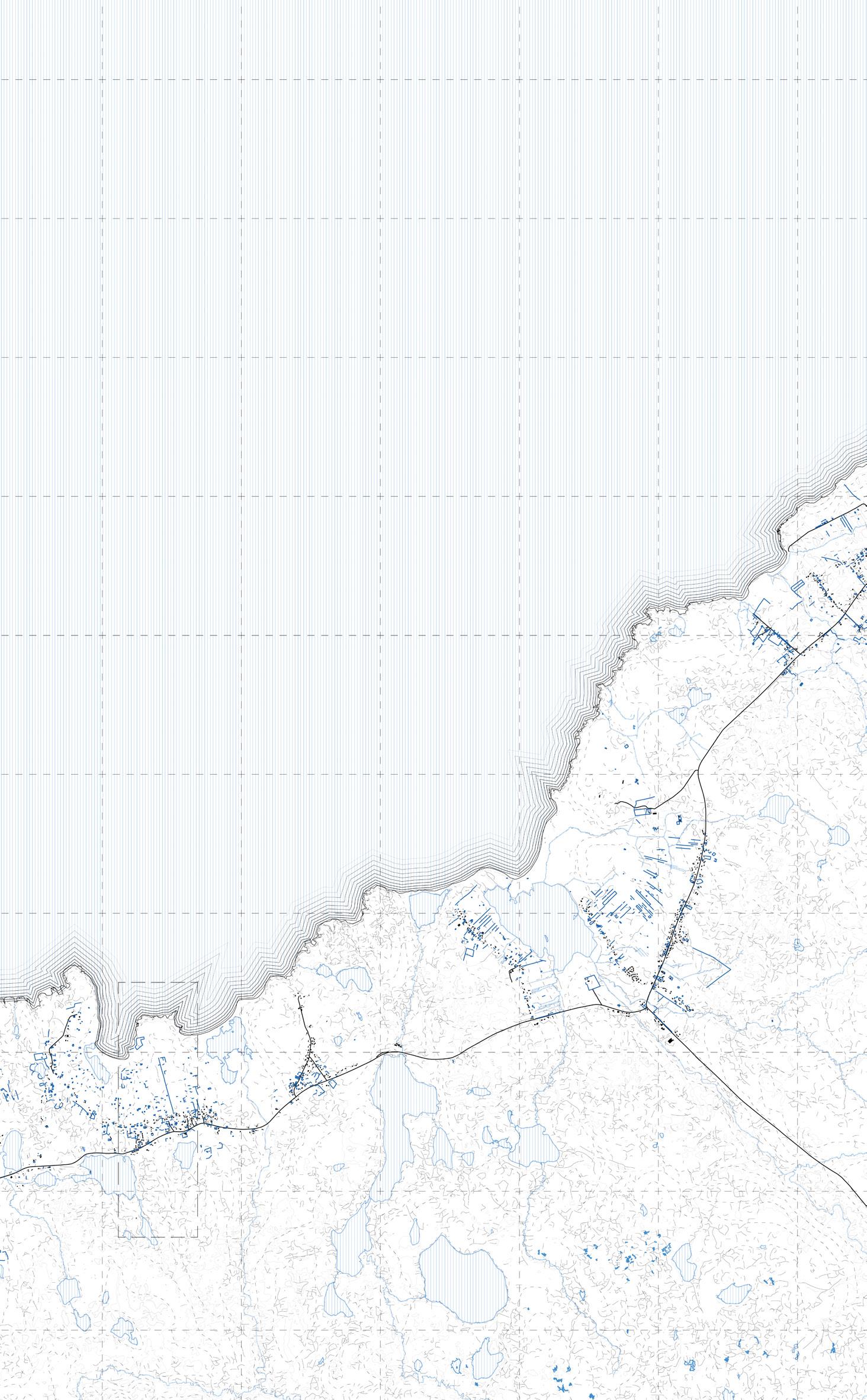

L’autre caractère marquant de cette île est la manière dont l’isolement et l’insularité se lit dans l’organisation du territoire. L’île de Lewis compte environ 19 000 habitants en 2024, dont 42% vivent à Stornoway, la seule ville de l’île. Le reste des insulaires sont répartis dans les villages longeant les côtes et vivent majoritairement dans des maisons individuelles, chacune isolée sur sa parcelle, elle-même fermée par des murs en pierre. La vie sur l’île est rendue particulièrement difficile par son éloignement avec le reste de l’Écosse, on atteint les terres en 2h30 de ferry depuis Stornoway, mais aussi par le climat rude et hostile des vents froids venant du nord, caractéristique de sa localisation géographique et de l’absence d’arbres sur une grande partie du territoire. De plus, le manque d’accès aux soins ou autre service public rend l’habitation sur l’île moins confortable que celle sur le continent. Depuis quelques années, l’île connaît aussi une crise du logement dû à l’augmentation des prix des habitations elle-même résultat d’une hausse de personnes achetant des biens secondaires sur l’île. On y compte environ 10% de résidence secondaire. Les jeunes foyers connaissent ainsi des difficultés à se loger sur Lewis, ce qui explique en partie la moyenne d’âge de plus de 60 ans sur l’île. Cela s’explique également par la part importante de personnes âgées venant vivre leur retraite sur l’île, à la recherche de tranquillité et de calme, puisqu’en effet, l’isolement et la solitude n’est pas toujours imposée, elle est parfois recherchée.

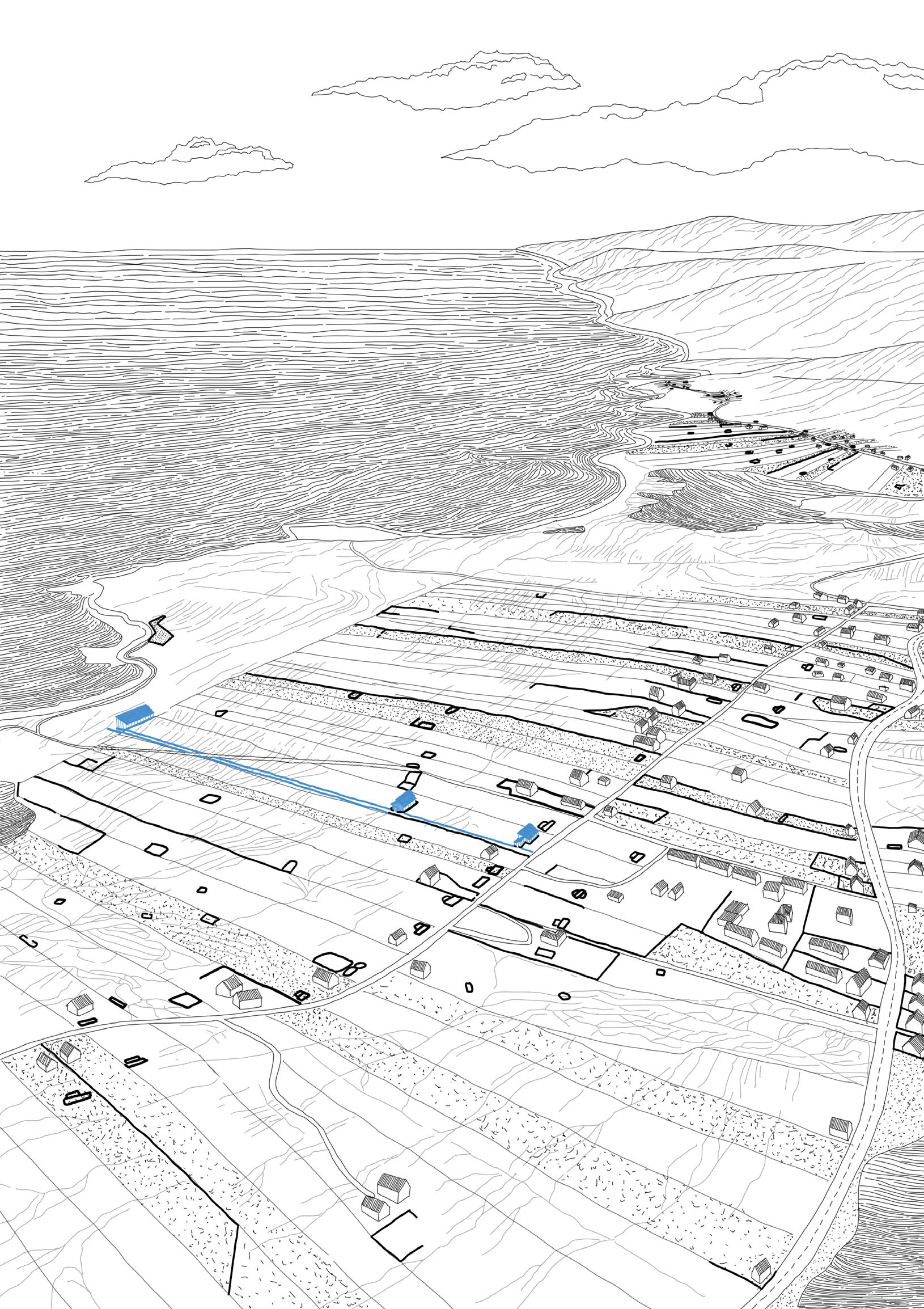

Le dernier élément marquant est le motif parcellaire unique de l’île. Les villages ont la particularité d’avoir un parcellaire très marqué provenant de l’agriculture et de l’élevage de moutons. Les parcelles sont étroites et en longueur, reliant la route (la drystane road) et l’océan ou les lochs, permettant aux crofters (les fermiers de l’île) de déplacer leurs moutons entre la plage, où ces derniers se nourrissent d’algues, et les machair, nom gaélique désignant ces champs fertiles de bords de mer, caractérisent le paysage de l’île de Lewis. Notre intérêt pour ces parcelles naît du motif particulier qu’elles créent dans le paysage, ainsi que le schéma de l’insularité qui s’y reflète encore une fois. La ruine représente pour nous l’interface, le lien entre le déjà-là et le potentiel projet. Travailler avec la ruine est une manière de pérenniser le patrimoine et de lui donner une nouvelle valeur en créant de nouvelles connexions avec sa propre parcelle et la communauté qui vit entre ces murs de pierre. Le projet vise ainsi à interroger l’avenir des ruines de l’île de Lewis, dans un contexte d’insularité et de crise du logement. Cela dans le but d’explorer la relation entre les insulaires, ces ruines et leur paysage.

Ce projet commence avec l’intention de s’intéresser à un matériau et à un savoir-faire particulier, ce qui nous a finalement conduit à la pierre sèche, une technique de construction qui consiste en l’assemblage de pierres sans mortier. Finalement, nous avons choisi l’Écosse comme terrain d’étude, l’occasion se présentant à nous à travers nos directeurs d’études Magali Paris et JeanPatrice Calori, et étant un territoire où la pierre sèche y est particulièrement présente.

Le terme drystane ou drystane dyke est le mot gaélique pour désigner la pierre sèche. En s’intéressant à ce savoir faire et à cette notion, il était pour nous primordial de rencontrer les personnes qui connaissent et transmettent ce savoir faire, donc lorsque nous avons effectué notre voyage en Écosse nous avons réalisé plusieurs entretiens mais aussi visité plusieurs architectures réalisées dans cette technique, et aussi de participer à un workshop de construction d’un mur en pierre sèche. Ce voyage et ces rencontres ont fait l’objet d’une restitution sous deux médias : le livret et un petit film dont le QR code se trouve au début de ce document.

De ces visites nous retenons quatre typologies que sont la turf house, la croft house, la black house et le broch, dont on cherche par le projet à réinterpréter. Finalement très marquées par notre visite sur l’île de Lewis, c’est cette île des Hébrides extérieurs au nord de l’Écosse que nous avons retenue comme site de projet. L’île est scarifiée par ces murs en pierre sèche qui servent principalement à séparer les parcelles entre elles ou créer des enclos pour les moutons, mais aussi par des ruines en pierre sèche. On compte plus de 3500 ruines représentant 20% du bâti total. Les insulaires vivent au milieu de ces ruines qui se trouvent parfois dans leur jardin et qu’ils se réapproprient plus ou moins. Notre première intuition a donc été de faire une collection photographique de ces ruines (voir page 64), ce qui nous a permis de constater qu’il s’agit pour la plupart d’anciennes black house ou croft house. Nous avons ensuite réalisé des cartes de l’île afin de se rendre compte de l’implantation de ces ruines, nous permettant d’observer que ces dernières se situent en majorité sur les littoraux et tout le long de la route principale que nous avons empruntée (voir page 64). Les quelques villages de l’île se sont construits autour de ces densités de ruines, représentant pour nous, des potentiels sites de projet.

L’autre caractère marquant de cette île est la manière dont l’isolement et l’insularité se lit dans l’organisation du territoire. L’île de Lewis compte environ 19 000 habitants en 2024, dont 42% vivent à Stornoway, la seule ville de l’île. Le reste des insulaires sont répartis dans les villages longeant les côtes et vivent majoritairement dans des maisons individuelles, chacune isolée sur sa parcelle, elle-même fermée par des murs en pierre. La vie sur l’île est rendue particulièrement difficile par son éloignement avec le reste de l’Écosse, on atteint les terres en 2h30 de ferry depuis Stornoway, mais aussi par le climat rude et hostile des vents froids venant du nord, caractéristique de sa localisation géographique et de l’absence d’arbres sur une grande partie du territoire. Aussi, le manque d’accès aux soins ou autre service public rend la vie sur l’île moins confortable que celle sur le continent.

Les villages ont la particularité d’avoir un parcellaire très marqué provenant de l’agriculture et de l’élevage de moutons. Les parcelles sont étroites et en longueur, reliant la route (la drystane road) et l’océan ou les lochs, permettant aux crofters (les fermiers de l’île) de déplacer leurs moutons entre la plage où ils se nourrissent d’algues, et les machair, nom gaélique désignant ces champs fertiles de bords de mer, qui caractérisent le paysage de l’île de Lewis. Notre intérêt pour ces parcelles naît du motif particulier qu’elles créent dans le paysage, ainsi que le schéma de l’insularité qui s’y reflète encore une fois.

La ruine représente pour nous l’interface, le lien, entre le déjà-là et le potentiel projet. Travailler avec la ruine est une manière de pérenniser le patrimoine et de lui donner une nouvelle valeur en créant de nouvelles connexions avec sa propre parcelle et la communauté qui vit entre ces murs de pierre. Le projet vise ainsi à interroger l’avenir des ruines de l’île de Lewis dans un contexte d’insularité.

Cela dans le but d’explorer la relation entre les insulaires, ces ruines et leur paysage, et en passant par l’ouverture des parcelles à la communauté. Le projet prend place dans le village de Bragar qui longe la drystane road. Ce village est caractéristique de l’île de Lewis par ce schéma d’implantation agricole en machair. Ces parcelles appartiennent à des communautés d’habitants et ce village est l’un des plus dense en ruines mais aussi en habitations qui se sont construites autour de ces ruines.

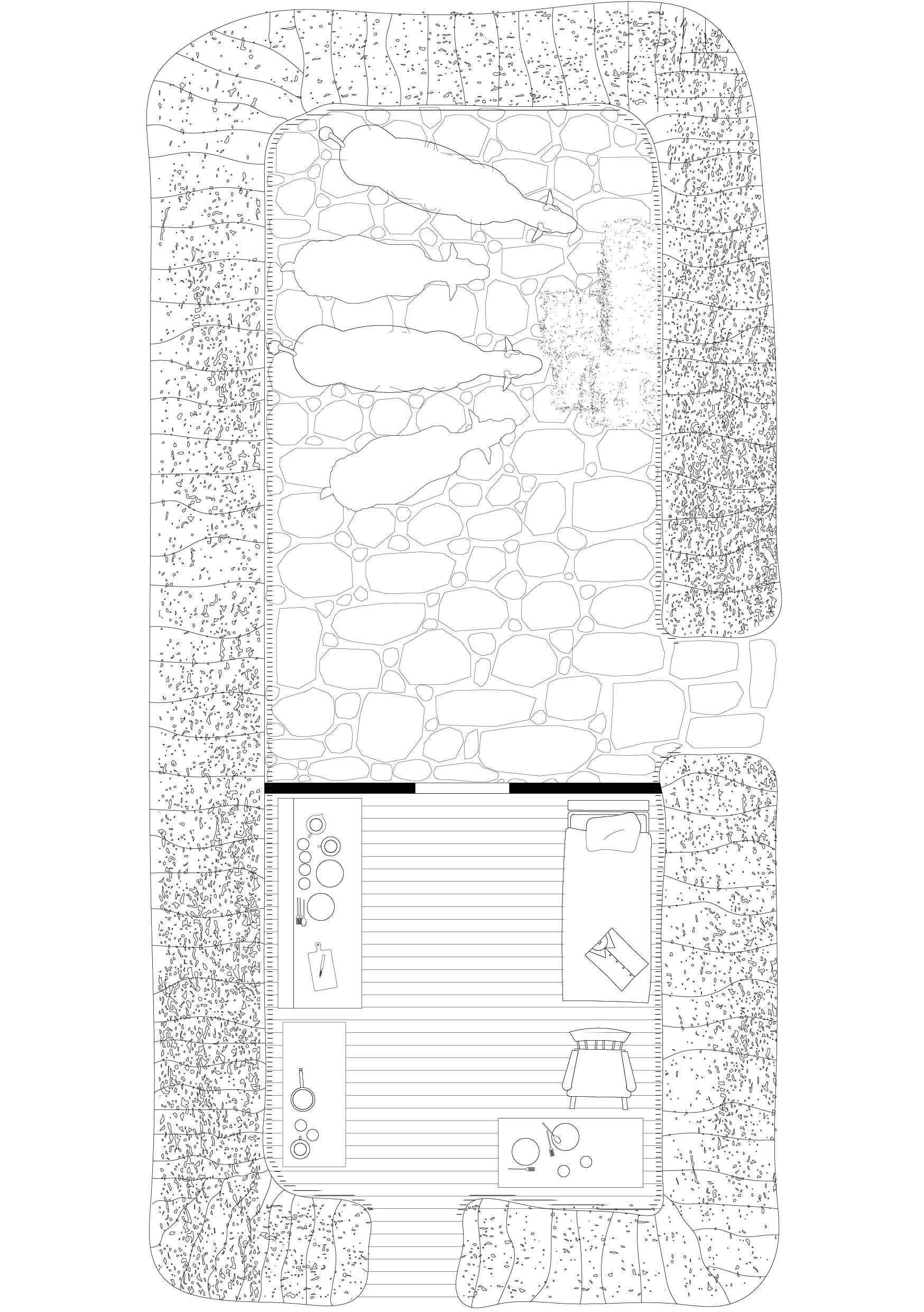

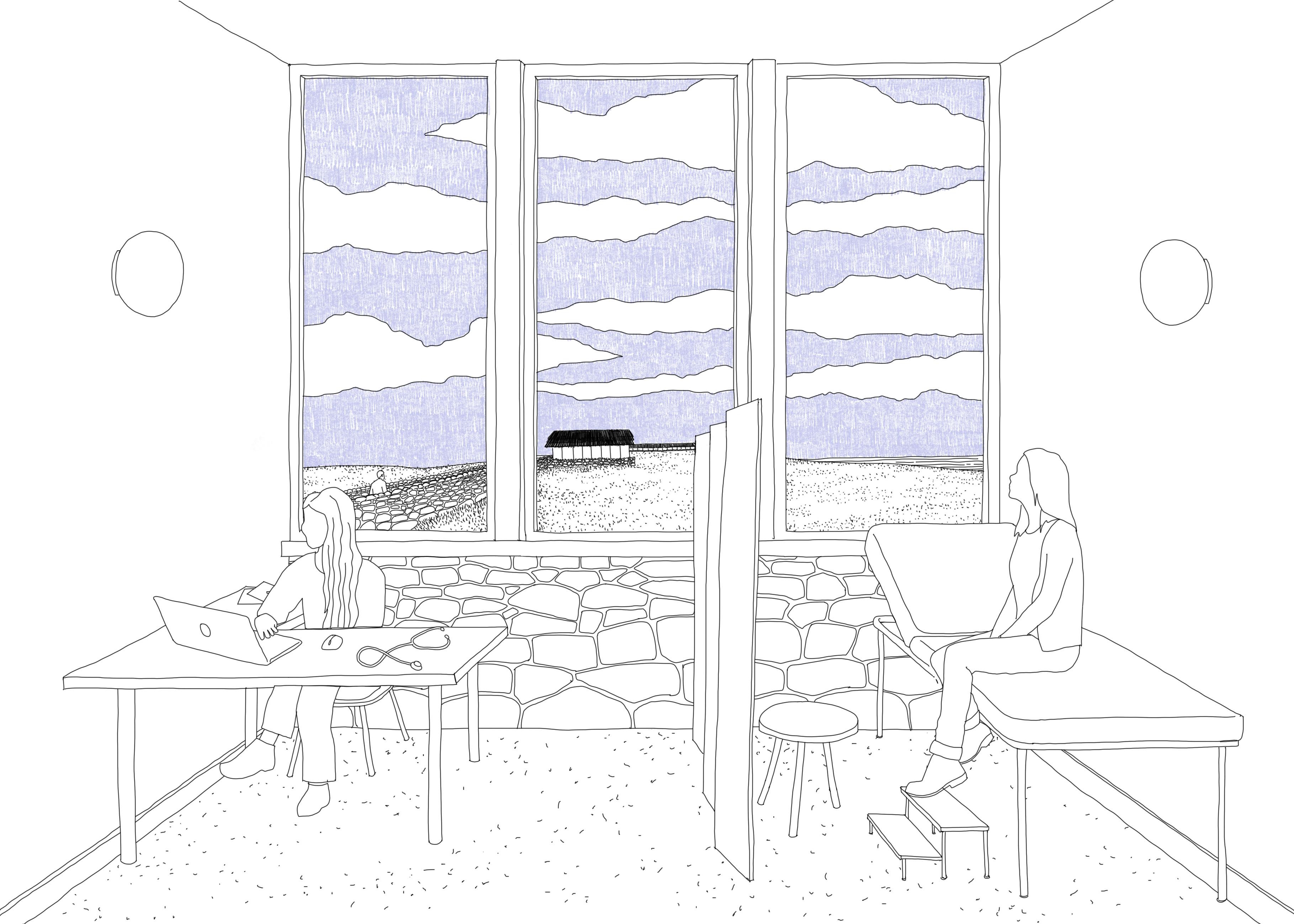

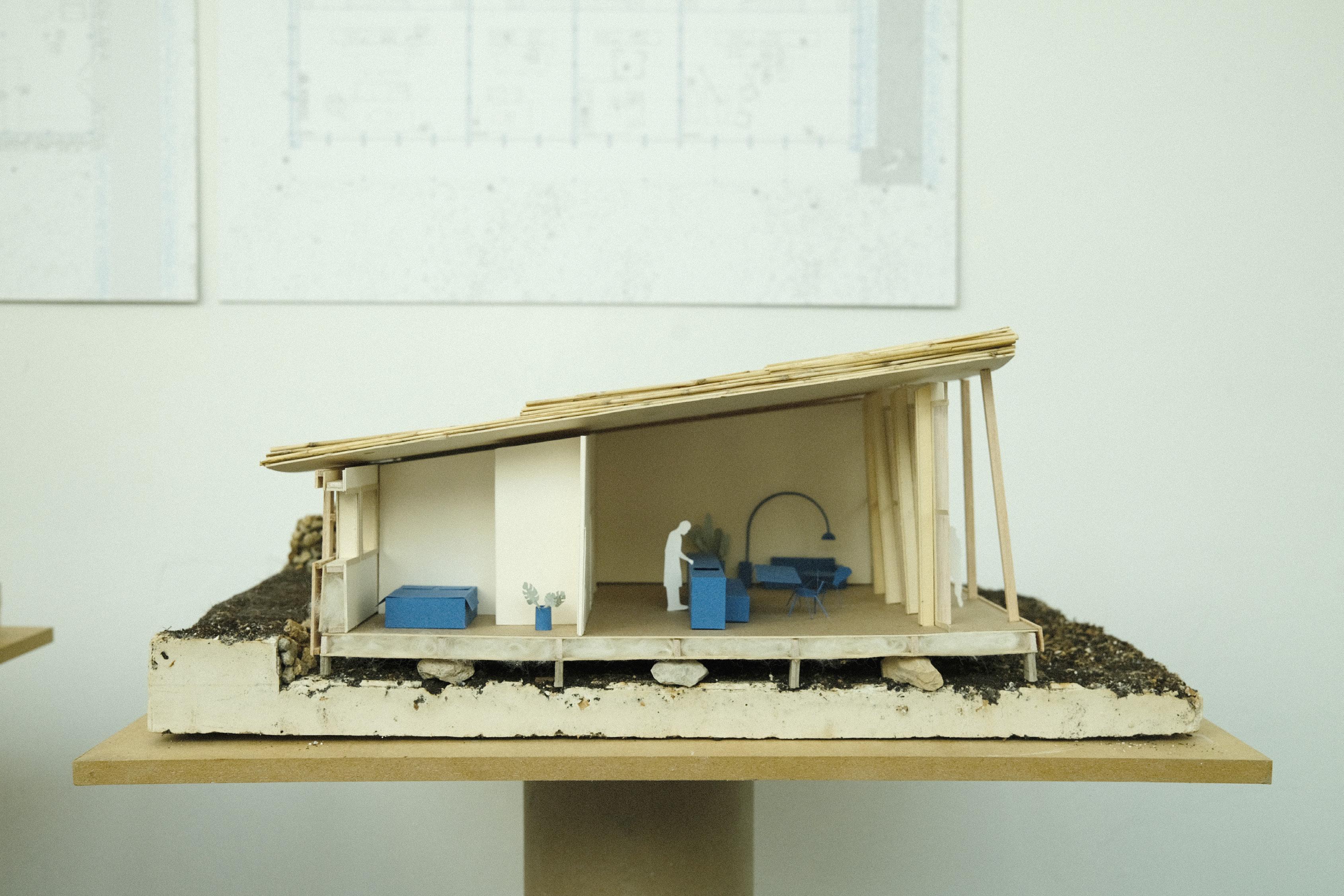

L’idée du projet est de développer une stratégie pour ouvrir certaines parcelles à la communauté et créer des lieux de bien commun répondant aux besoins de l’île. Tout d’abord le choix de la parcelle doit avoir une ruine, des murs en pierre et avec un accès au paysage (loch, océan, marécage). Le premier acte pour nous a été de venir doubler ces murs en pierres déjà présents et/ou de les prolonger, afin de créer un espace de circulation à l’image des broch, et d’apposer la figure de la rue sur toute la parcelle comme lieu de rassemblement, d’échanges entre les personnes. La parcelle est travaillée en séquence, notre nouvelle rue en PS desservant ces différentes séquences.

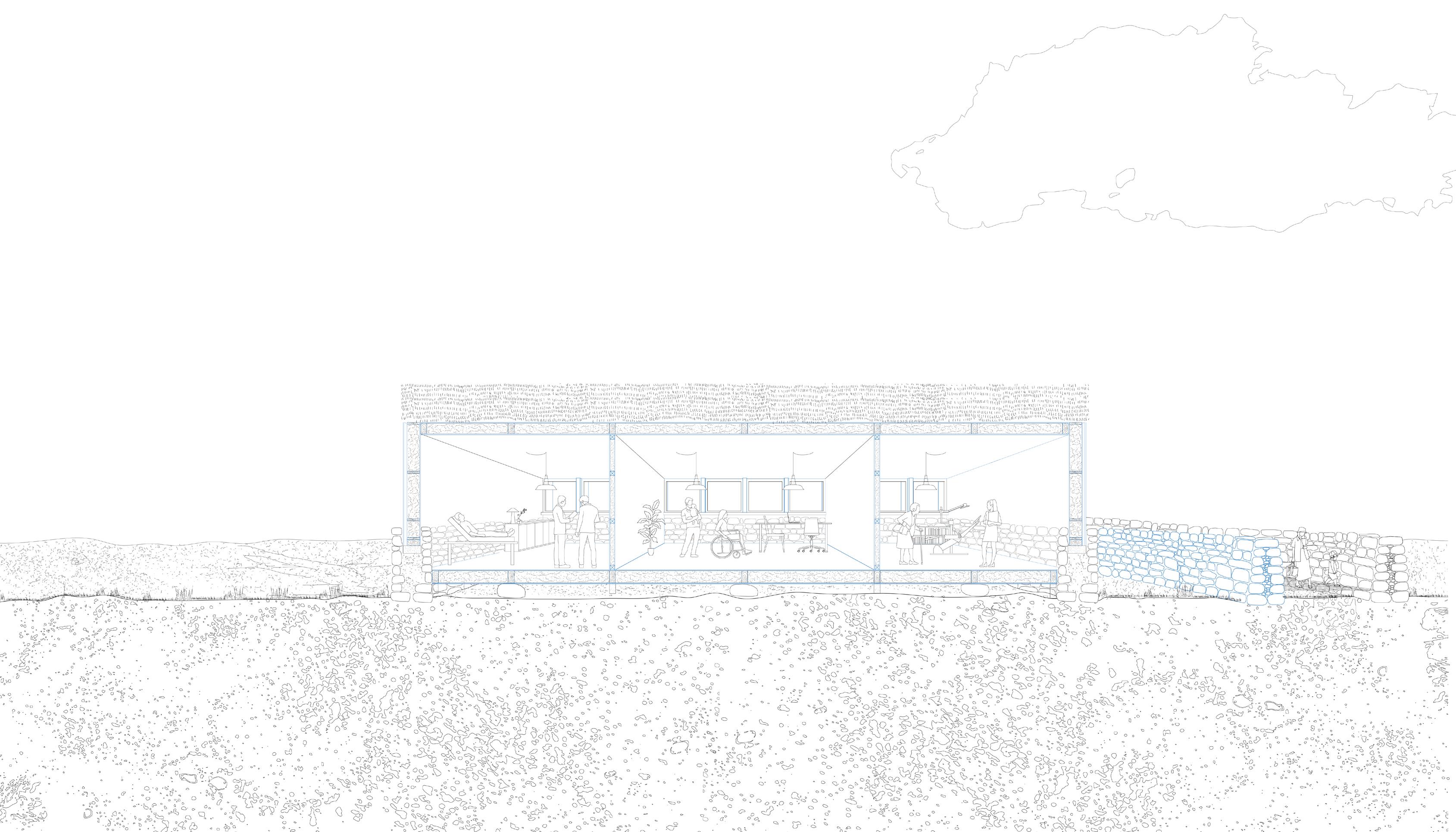

La première séquence est la ruine, en second c’est le croisement du chemin avec un enclos et en troisième la construction de logements en fin de parcelle et bords de mer. L’implantation de la première séquence se fait donc dans la ruine en bord de route qui se place telle une porte d’entrée sur la parcelle et le paysage. Le but est de réactiver la blackhouse ou la crofthouse en la réhabilitant avec un programme public au milieu de ces maisons individuelles présentes tout autour. Le projet propose ici un cabinet médical dans lequel les médecins peuvent venir exercer de manière ponctuelle. La structure est en bois, posée directement sur les murs de pierres et de terre existants. L'isolation est en laine de mouton et la toiture en chaume avec un débord léger permettant l’écoulement de l’eau sur les murs en pierre favorisant ainsi le développement de la biodiversité. Le plancher est surélevé du sol par des fondations ponctuelles en béton afin de réduire l’impact du bâtiment sur le sol. Par cette matérialité, c’est une réinterprétation des typologies étudiées qui est proposée.

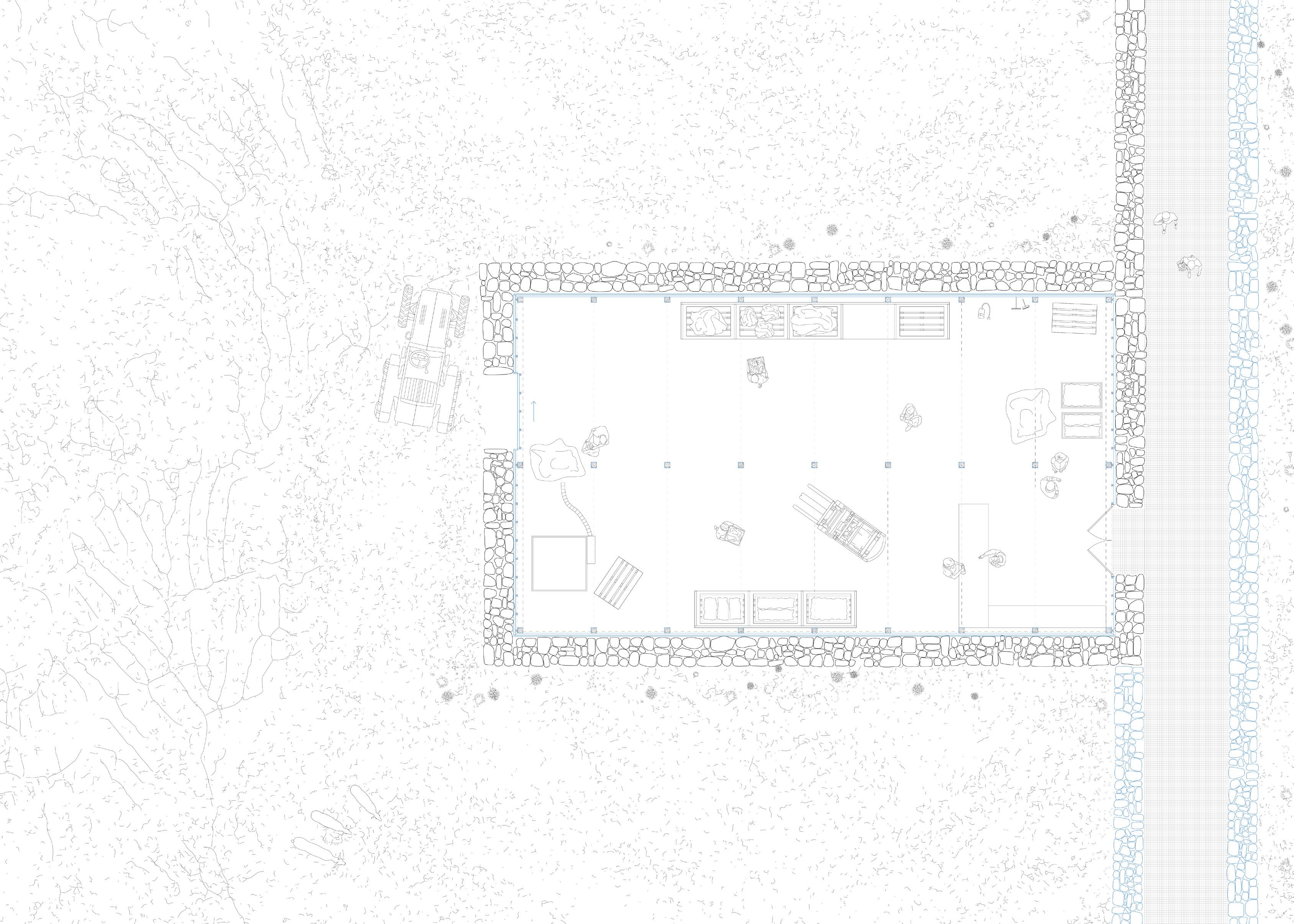

La deuxième séquence se place en milieu de parcelle le plus souvent, au moment où le chemin rencontre un enclos en pierre sèche parfois abandonné. Ce dernier est réhabilité et abrite un programme de lieu de stockage et de vente visant à revaloriser la laine de mouton, présente en quantité dans le pays et sur cette île. La structure se fait également en bois, cette fois de manière indépendante, entre les murs en pierre qui ne servent que de délimitation de l’ouvrage, et sans isolation, avec un système de bardage bois filtrant les vents dominants afin d’assurer une bonne ventilation du lieu. La toiture est également en chaume.

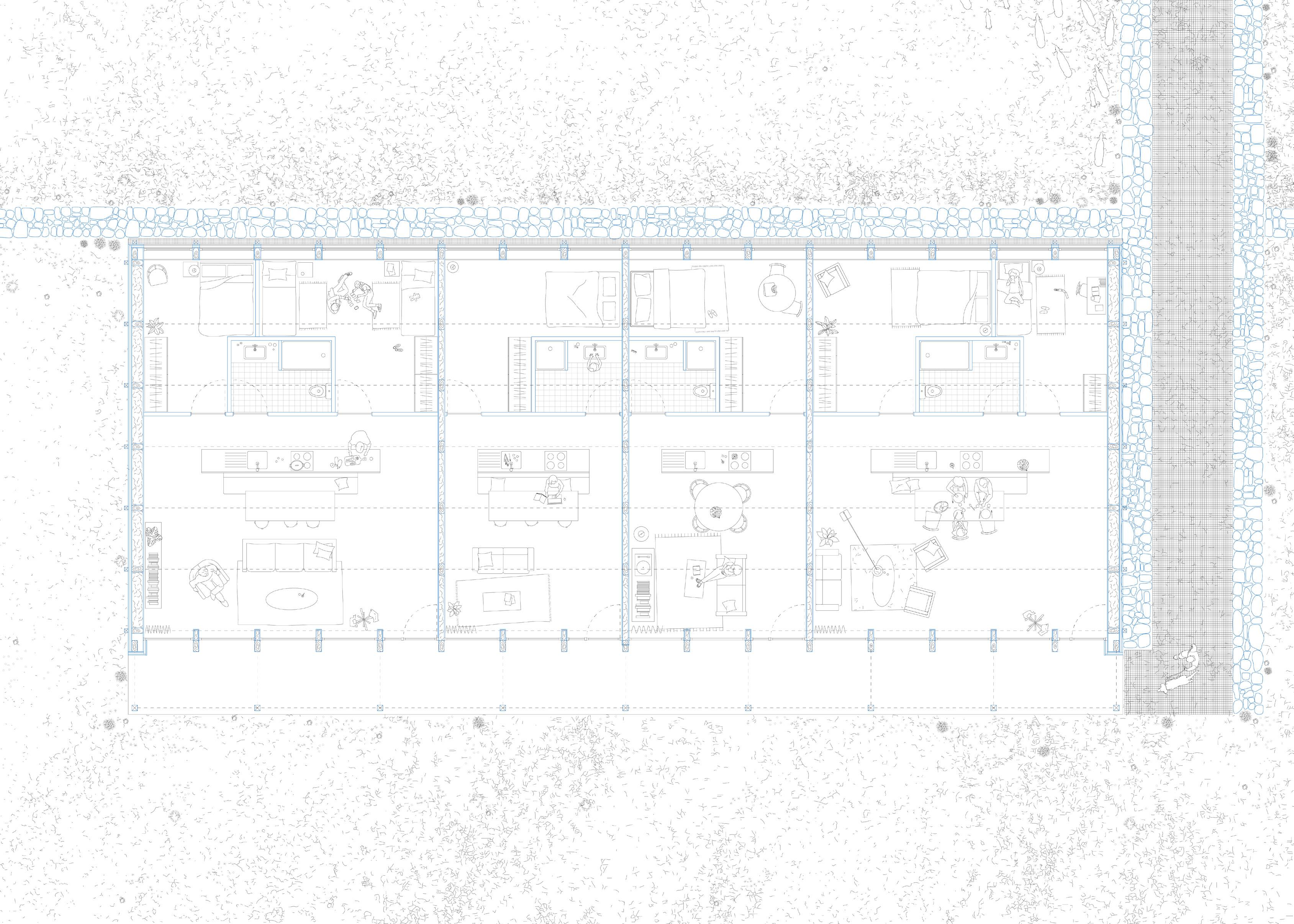

La troisième et dernière séquence est en fin de parcelle, où des nouveaux logements sont construits face à l’océan, entre les parcelles et murs de pierre sèche. Ces habitations sont prévues pour répondre aux besoins en logement à long terme pour les habitants de l’île mais aussi à court terme pour les médecins venant travailler dans le cabinet ainsi que pour les touristes. Le bâtiment se loge le long d’un mur de soutènement en pierre sèche, avec toujours une structure en bois, une isolation en laine de mouton et une toiture en chaume. La façade orientée au nord et face à l’océan est entièrement vitrée, et chaque appartement est desservi par une coursive extérieure abritée dans le prolongement de la toiture.

Finalement pour penser l’avenir de la ruine c’est la ruine dans son territoire, dans son contexte bâti et non bâti qu’il faut penser. Penser l’avenir de la ruine c’est l’idée de prendre soin d’un patrimoine bâti mais aussi de ces gens qui l’habitent.

En ouverture nous vous proposons d’imaginer la propre ruine du projet. Un lieu où la nature reprend ses droits, où des petites forêts poussent et où les matériaux du projet lui-même pourraient devenir des gisements de matière pour de futurs projets.

Werner BLASER, La roche est ma demeure, WEMA, 1976

Hélène BURGISSER, Des murs vivants, Rossolis, 2022

Roger CAILLOIS, La lecture des pierres, Xavier Barral, 2014

Roger CAILLOIS, L’écriture des pierres, Flammarion, 1994

Delpire & co, Histoire des pierres, Villa Médicis, 2023

Matthieu DUPERREX, La rivière et le bulldozer, Carnets Parallèles, 2022

Jeanne GANG, L’art de greffer en architecture, Park Books, 2024

Lawrence GARNER, Dry Stone Walls, Shire Library, 2008

Moses JENKINS, Building Scotland, Celebrating Scotland’s Traditional Building Materials, Historic Scotland, 2010

Justine LAJUS-PUEYO, Alexia MEDEC, Margot RIEUBLANC, What about vernacular ?, Parenthèses, 2023

Christophe LAURENS, Patrick BOUCHAIN, Jade LINDGAARD, Cyrille WEINER (Photographie), Notre-Dame-des-Landes ou le métier de vivre, Editions LOCO, 2018

Peter MAY, L’Île des chasseurs d’oiseaux, Éditions du Rouergue, 2009

Pierre PECH, Les milieux rupicoles ; les enjeux de la conservation des sols rocheux, Editions Quæ, 2013

Philippe POTIÉ, Le voyage de l’architecte, Parenthèses, 2018

F. RAINSFORD-HANNAY, Dry Stone Walling, Stewartry of Kirkcudbright Drystane Dyking Committee, 1972

Bernard RUDOFSKY, Architecture without Architects, Academy Editions Ltd, 1972

Richard SENNETT, The craftsman, Penguin, 2009

Henry STEPHENS, The Book of the Farm, Alex Langlands, 2011

SVBWG, Vernacular Buildings, 1975-2023

Entretiens du patrimoine, «Faut-il restaurer les ruines ?», Direction du patrimoine, 1991

Biogenic Construction: Materials Architecture Tectonics, CINARK, 2023

Circular Construction: Materials Architecture Tectonics, CINARK, 2019

FILMOGRAPHIE

Atelier Géminé, Au pays des pierres, 2023

Martin MCDONAGH, Les Banshees d’Inisherin, 2022

Arte Regards, Réensauvager les Highlands, 2024

Can you introduce yourself ?

My name is Kristie De Garis and I’m a dry stone waller. How did you became a waller ?

I grew up in the very far north of Scotland where there are dry stone walls everywhere, and I loved them when I was a kid. I always thought about them, I was always really fascinated. Then we lived in Edinburgh and about six years ago we moved to Perthshire, and I found out that there were some courses. I didn’t actually take them but Luke took it instead of me. So he learned, and then he taught me and we learned just building in my garden. I just kept building walls in my garden and then eventually started working with Luke and now we work together. Do you have any diploma or training ?

You can take exams. I don’t want to. I have strong opinions about the Dry Stone Walling Association and the exams, and accessibility for the exams and all the things like that. So I have chosen not to, but Luke has taken his exams.

What is your opinion about the Dry Stone Walling Association in Scotland ?

I would never join. I’m a person who believes very strongly in supporting women. I am a woman and I also want to support other women. I’m also mixed race and I believe very strongly in supporting diversity but there is none. And I don’t feel like they do enough to support women and people from diverse cultural backgrounds. That’s my position.

What are your current projects ?

I’m doing a public art commission. It was supposed to be dry stone, but it’s very hard to get planning permission for dry stone in public areas. So it changed. And now we’re doing a COVID memorial with very large stones that will be carved with a poem and placed around a place in Scotland called Kinross (in the north of Edinburgh).

And also obviously my book, which has a lot to do with dry stone. It’s a memoir about growing up in the north of Scotland as a mixed race kid, and my experience with that, how I felt very connected to the land, but not necessarily the people. And how when I moved back to Perthshire, I really connected to the land and dry stone ; that was very healing for me in many ways. And then our project, we’ve got loads. We’re building a loads of walls this summer. Actually, we’re building a Buddhist retreat. It’s going to be a place where people can go and remember their family members who’ve passed away and maybe spread their ashes. We’re also building a big wall beyond a bench. And then lots of just very standard dry stone stuff like repairs. Lots of repairs because there’s so much dry stone in Scotland that needs it. A lot in people’s gardens. Rarely public. Occasionally for like big estates who have a lot of dry stone walls.

What are the essential tools used to build a dry stone wall ?

The cool thing about dry stone is that — because it’s a traditional craft — you can still build it the exact same way that it was built 2000 years ago. You don’t need to use tools. Tools make it easier, and also they help with shaping the stone. There’s a batter on a dry stone wall. So tools really help you to get the faces of the stones to sit really nicely in that line of the wall. So it looks really neat and really

precise. But the tools that we use most commonly are hammers and chisels. There’s also lines and bars. I don’t like them very much because they get in the way but it’s super helpful with maintaining that really nice line on the wall.

Did you create a tool for yourself ?

No, not really. But all wallers have preferences. Some people like power tools. And to be fair, they make the work really quick, but I feel like it’s cheating. Everyone has a hammer they prefer or chisels that they prefer. It’s just whatever you like.

Are there some more contemporary tools ?

There are tools that have like coatings on them and it’s like a sort of a hardened sort of diamond to help the tools sort of maintain. Because they have to be sharp. And when they have these coatings, it keeps them sharp for longer. And also, if you have really big stones : diggers, small diggers, big diggers, some stones are just too big to be moved by people.

What is your relationship with the craft of dry stone ?

I, because of my sort of feelings towards the more official side of the Dry Stone Walling Association and things like that, I went through a period of time where I was thinking maybe I’m not going to be able to stay doing dry stone. I have a lot of opinions that a lot of dry stone wallers probably wouldn’t agree with. Because it is a traditional craft, and sadly there are quite a lot of traditional attitudes in it. Then I realized I love dry stone, like I genuinely love it and I’m going to keep doing it. I don’t just love dry stone, I love stone. I love everything about it. I find the work incredibly sort of medidative and healing for me. I like the work. Some people get the same thing from trees. They feel very calm around trees. For me, it’s stone, so it’s very grounding. I’ll always do this. I think to some degree, even if it’s not full time. I just love it.

And summer walling is… There’s nothing better than building dry stone in the summer. It’s different to every other form of construction. We have to tell clients this quite a lot : it is slower. You might not, but every stone is placed by hand. The hearting is by hand, all of the stones are placed by hand. And that just takes time. But then again it lasts for hundreds of years. I have such good feelings towards dry stone. This is a lot of what I wrote in my book, it has changed my life in so many ways, really incredibly positive ways.

Why is it important for you to preserve the skills of drystone ?

I think actually in most of Europe there are dry stone walls everywhere. I know in France — and not just dry stone walls — there’s a lot of traditionally built dry stone buildings as well. I mean, it’s preserving history in the most incredible way.

And also I mean, there’s nothing like dry stone in terms of sustainability potentials. The building blocks are millions of years old. We build a lot with local stone, so there’s like no carbon footprint. It lasts for hundreds of years. It’s really easily repaired as well. Mortar walls are not easily repaired. Sometimes you have to use mortar, and I understand that, but that industry is responsible for more carbon output than all of the aviation industry. So it’s hugely damaging.

In Scotland particularly, the history of dry stone and how much work went into each wall ; we have walls that go up mountains, and those were built by hand by people. We have something called “ wall

treasure ”. And when you take walls apart to repair them, you’ll often find balls that are hundreds of years old. You can sometimes be really lucky and find cooler stuff than that. But the historical element of it is really incredible. And again, sustainability. Why put up a fence or a mortared wall when you can do something that is totally in harmony with the environment. Things live in it, things grow on it.

Is there a part of nostalgia ?

Yes, hugely. Growing up in the north of Scotland, we’ve had something, it’s a place called Caithness, and they have something called “ flagstone ”. So that’s like a slate, it’s very flat. The walls are built of all these tiny little flat pieces of stone, and they also do fences. So I grew up with that and when I was a kid I was fascinated by the walls. I used to do things that children do like put your hands on them and wonder if the stones will tell you a story. So for me there’s a lot of nostalgia in stones and in dry stone in general.

Do you know any new/more contemporary dry stone construction ?

There’s quite a few architecture firms in Scotland that are gravitating towards dry stone, which is really cool to see. The thing about dry stone as well is that it can be used on exterior and interiors as well. If you have the right stone, you could have an entire wall of dry stone as an interior wall. This is something that we’re really hoping to do.

I’m a photographer as well. Esthetics are very much my thing. I like how things look. I want them to look nice. And this is something we’re trying to transition into, is letting people know that dry stone can be part of contemporary esthetics. This is a very rustic aesthetic that’s a traditional wall. But if you use the right stone, you can have an incredibly contemporary look. There are a few architecture firms that are building some really cool rural houses with more contemporary dry stone features.

What are the qualities of dry stone in the landscape and for architecture ?

Anything. To be fair, if you get really harsh winters in some parts of rural Scotland, especially in the higher places, you get really deep snow. And snow can feel a lot of pressure. If you get really deep snow against a wall, it can knock the corpse off and it might need repair after that. And that is something that we have to do. But it takes quite a lot of flooding to get out of. It would have to be a torrent of water for it to knock the wall over because although it’s a solid thing, it’s porous so the water can flow through it to some extent, and it withstands different weather incredibly well. Heat doesn’t do anything to it. Snow or really incredibly heavy floods would be the only thing that you had to worry about. And again, it’s very easily repaired, unlike a mortar wall which would just fall to bits and then it would be very difficult to repair.

If I was building things in my own home, all the boundaries would be in dry stone. In terms of the environment. It’s just amazing.

There’s also lots of really lovely dry stone features that have been sort of incorporated over the years. So there’s like little holes and little spaces that you can build for bats. My daughter keeps bees and these are a traditional dry stone feature. They’re called “ bolis ” and they’re shapes in the wall so that you could put the bee steps into. You can also do holes in the bottom of the wall for small animals to run through. And from there you can build little places for birds to nest in. Dry stone can work completely in harmony with the environment.

I was doing a lot of this recently when I was applying for the public art stuff and applying to build in some areas that are protected. And although that wasn’t successful for other reasons, it’s dry stone as the sort of structure that can be built in these places because things will grow onto the stone, they don’t disrupt the environment in any way. Dry stone is the best possible thing for it, to work in harmony with an environment. Definitely.

Ideally, what do you think would be the best way to pass on this craft ?

Having people being able to talk about it passionately. I think when people think of dry stone walling,

it can seem really boring and dry. But when people really love it, you realize how interesting it is as a craft. I’m constantly amazed by the things that I learn about dry stone. What you have to do (to learn this craft) is you would take a course with the Dry Stone Walling Association. And you would then maybe do your first exam. But the best way to learn is to learn directly from building with someone else. I was really lucky to have Luke and I have some other friends too. But it’s quite hard, especially as a woman, to find people who are willing to work with you and who you are comfortable working with. So for example, what you might have to do is phone up a man you’ve never met and he’s going like “ meet me in the middle of nowhere.” But that makes me a little uncomfortable. I’m not going to lie, and there’s no background checking or anything, so that’s not ideal. So I just think there needs to be more structure. I think in terms of being able to pass on this knowledge because women are interested in it. I’m very interested in it. I think just a little bit more structure in terms of making that process a little smoother and a little safer.

The best way to do it, to learn it, is to do it. You can read as many books as you want and you won’t understand the nuances until you’re there and building. I’ve had so many positive experiences. So I’m really hoping that, with the book that I’ve written, that I can pass on some of that interest and passion to other people who might want to try it. Because it’s a skill that’s passed on through being taught by another person. A book just can’t. There’s some amazing dry stone books, don’t get me wrong, but you can’t learn unless you do it.

And the other thing is, you need to make a lot of mistakes to learn how not to make them. And there is no way around that. And I’m very much at the beginning of my dry stone career. There are people I know who’ve been building for 25 years and watching them is incredible. I’m still very much at the beginning and making a lot of mistakes. And the thing is, the basics of a dry stone wall are really simple. All of these really simple rules and anyone who has that knowledge can build a solid, dry stone wall. What you learn over time is how to make them look really pretty.

Is the esthetic of the wall important for you ?

Yes, so important. Luke and I… I don’t know if it’s like a masculine feminine thing or just a Luke and Kristie thing. If we could meet somewhere in the middle, I get a little bit too stuck on it because sometimes a wall just has to be built and I’m there being like “ all that stone isn’t quite right ”. I think I’m a bit too obsessed with how things look. Of course dry stone is a really beautiful thing in itself, especially when it’s done well.

Can you introduce yourself ?

My name is John New. I’m the chairman of the West of Scotland Dry Stone Walling Association.

How did you become a waller ?

It was through landscaping. I’ve run a business for about 35 years, and we used a lot of stone in landscaping, and that brought interest into it.

I always was fascinated by walls and the environment, and I enjoyed building them. With mortar as well. But when I discovered the Dry Stone Walling Association, they put all the technicalities, I was always doing everything right but not in the right order. So once I joined them, it all dovetailed together. And for the last 20 years I’ve been with the association. We do a few community projects and restore field walls. And we passed on our skills to the people who went to help, which is so important. And you can go up through different stages of examination from initial, intermediate, advanced to master craftsman. It takes many years to build up those levels of skill.

Do you have a diploma or training ?

My level is intermediate, which is classed as a professional and it’s the beginning of the initial level. It’s really doing a simple wall. Intermediate means you’re building more. You can build a good strong wall and certain features. We can build to other higher levels of craft where you’re making an archway, high walls, maybe a square, a gap through a wall. I can do all these things, but I just didn’t bother getting myself qualified for it because I already run a team, and with my age and energy level.

How did you become the chairman of the association ?

Really just by showing enthusiasm for the branch, I was always here to help. Also being involved and through time they just said “ would you be chairman ? ” because the other chairman had been in for about 12 years and it was needing a break. Started off as treasurer then chairman. They didn’t let you go when you’re in, it’s a job for life.

What are your current projects ?

We have a site in Kilsyth where they do all the training and all the roles designed and set up. In this field wall they’re few roles too, but they’re more sweetly designed for people to learn and go through examinations. It definitely features on them and we also like to try different stone types as well, like sandstone, or different wall styles like the Gallery style. You can see that up north and in the more upland areas. It’s like an upside down wall, there’s a lot of small stones at the bottom and break through bans and then heavy stones, two maybe three layers of heavy stones at the top. And these make a fantastically strong wall, but the very big heavy stone is a lot of effort to build. But the walls are fantastic. Depending on the stone type you’ll get different styles of wall.

When did you start this wall ?

We started two years ago and we’ve had six courses. So it’s between 12 and 18 people per course, plus our own branch members. So you can do quite a chunk in a weekend. You can see it stripped down to the base and rebuilt back up to height. And it’ll make a fine wall for a long time.

What are the essential tools used to build a dry stone wall ?

You need basic tools for taking a stone like a big steel, a price bar, hammers, pens, for creating a line in a batter, you have a guide to build with. That’s basically all you need. If you’re going to split stone or break stone, we’ve got all different chisels and hammers, but we tend not to use it on this type of stone as you take it as it comes. With sandstone or sleet, it’s much better for that. But you can fashion the stone and make it fit. Here you take it basically as it comes, which is a greater scale because you have to judge the stone, where it’s going to go in the wall and the type of stone you want to pick up.

Did you create your own tools ?

No, we usually buy them. At the bottom, the top pieces that hold the patterns together, they were specially designed by us and a blacksmith built them and made them for us. And people use a bit of wood without drill in the drill down. There’s various methods, but we’ve got the cross paths with metal and they’ve been very successful over the years.

What is your relationship about the craft of dry stone ?

I just love the craft. I think it’s a fantastic craft. It’s ancient. It was back thousands of years and I’m fascinated how the stones all hold together after all that time just by gravity. The method of keeping the stones flat into the wall, it creates a lovely solid construction. And it’s the same all over the world and it works. Although It look simple to watch someone do it, the skill is actually in the eye for the stone. When you pick up the stone you immediately know where it’s going to go and why. And that’s my fascination with it.

I get great satisfaction when you see a big pile of rock and stone and then you see a thing of beauty at the end of the day. And you know that this wall of stone will last for 100 years, 200 years. In the last 20 years, I’ve had no failures. The only things that will knock them over are cattle or a cat. But they shouldn’t just fall down by themselves, by pure construction. That should never happen.

What are the qualities of dry stone in the landscape and for architecture ?

That’s a win-win situation. The stone is often already in the environment. So you’re using the natural stone that can be reused repeatedly, time and time again. The whole wall can be moved if you want to move it without any distortion. The stone would be despoiled by mortar. Wildlife lives in it. We often find voles, toads and insects very often over the winter, like butterflies. They also act as a corridor between areas for the farmer. The benefits are also for the cattle or the lambs or the sheep that can all shelter in the back. They’ll find a warm spot and they’ll go down to get some shade. As well in the hot weather. So there’s so many benefits for them. It’s so much nicer than a fence and it just looks so natural and you find that they’re very often places where they’ll use them.

Do you know any new dry stone construction ?

Architects are nervous about dry stone walls, for some reason. They don’t like when it’s too high because they feel structurally that’s unsound, but very often isn’t. There’s walls in the French Alps, 10 to 20 meters high and there for hundreds of years and as solid as they were. These master craftsmen built these walls like a whole slab, and they are a fantastic structure, they’re far better than concrete or anything else. If a bit comes out of a movement, even in an earthquake zone, they just need a little adjustment. Here we don’t get earthquakes but the wall moves within the landscape, if there’s a frozen ground that might heave it. When it snow, I would just settle back for the stones. Even if they go off a bit, they still hold even after 100 years. If the castles are leaning against that, they may bend a bit, but it still holds.

Running maintenance dry stone walls would be normally employed once a year. They would come in for a month or two to the farmer and repair any bits that need to be fixed and make sure the corpses are all sound because they’re the crucial part. You have to make sure they’re all strongly put together

and reopened so they don’t move at all. Cattles often want to scratch their necks and so they go and scratch against that. And that’s what can knock them off the pool. And then once they go, it doesn’t take much for them to start pushing them and knocking them over. But the farmers have thousands of over hundreds of years of piles of stones at the side of the field, which were wasted on them.

What is, for you, the future of the association ?

I’m quite positive for the future because I think with the modern world, people are going back to traditional crafts and I’ve seen it with all sorts of crafts. People that you should see today, we’ve got a whole makeshift of people here, we very often get professionals, doctors, and they’re just fascinated by these walls, covering the environment. They may have a house where there’s an old wall that’s going to disappear. It was just a fascination. Some people want to take it further and see a craft and take care of it. And it’s like making very good money. If you are up to a high level of accreditation then you can make very good money.

There’s been a resurgence of interest all through Britain in the last 20 years. But in the last year or so to make it visible to people that we do community projects in a sense that you might build a small world and people are fascinated to see it put together.

I think the internet has made a huge difference. Before you had to go to a country fields to try things, get people’s engagement. We used to get 6 people on our courses, and now we’re getting oversubscribed, up to 18 or 28 people. So it really has become a very popular thing to do.

Can you introduce yourself ?

I’m Niamh MacKenzie and I am a student with the University of the Highlands and Islands and I’m doing a PhD looking at drystone dyking and its relationship to intangible cultural heritage.

How did you get interested in the craft of dry stone ?

I come at it from the perspective of a researcher rather than a craftsperson myself. Although the area that I grew up in, there’s a lot of dry stone walling. It’s always kind of been in the background of the landscapes that I’m familiar with, but it wasn’t something that I was always hugely invested in. I could appreciate them and especially esthetically, I thought that they were really stunning, but it wasn’t something that I knew a lot about. And then when I had the chance to study with UHI, who I did my undergrad with, it came up again and I was just really thrilled to work with them and with my industry partner. I knew it was a topic that had a lot of potential to feed into wider discussions about how we approach traditional craft in Scotland and into conversations about intangible cultural heritage, which has quite always been a real interest to me. Once I got into it, I just found that there was so much potential, so much to know and so many people to speak to.

What is the subject of your PhD ?

I’m asking questions about the way that, if we consider drystane dyking not just as a very practical skill, but also as an example of intangible cultural heritage, can add to our sort of understanding. How framing drystane dyking as an intangible cultural heritage can have a positive impact on the way that communities use it towards their own sort of sustainable development and skill development is the subject.

Do you know any new dry stone construction ?

I focus predominantly on drystane dykes. And so a lot of the people that I speak to are still building a lot of those. But you can see it used in lots of really artistic and creative outputs now as well. There’s a lot of sculptures and that is very much still prominent as an esthetic choice. You see it creeping into suburban areas as well. So over time there also were predominantly agricultural areas to start with. And we see this sort of much more esthetic choice in lots of different ways. And that’s becoming a really important way about how we consider the skill and how people are learning it today. So there’s lots of incredible examples.

Is there a future for dry stone instead of rebuilding ?

I would say yes and no. I feel like dry stone as a building method has really come back to the forefront in people’s understanding of sustainability and sustainable building methods. I feel like it’s always been appreciated. But as our sort of understanding of what we need to do to live sustainably in communities kind of grows and comes to the forefront of our mind. You see it being discussed in that way a lot more. People are definitely aware of that. However, it’s more that it can be definitely used alongside other methods rather than coming back and replacing them. I also feel, myself included, that we can be a wee bit naive about it, we see it as very sustainable because it has very low carbon output, once in place, and to get it there is quite minimal. But that’s only if local stone is used, if we ship stone from all over Scotland or even wider, the sustainability of the method is called into question. It’s something that we can certainly see working alongside more contemporary methods in a really sensitive way. There are lots of really good examples of that.

What are the qualities of dry stone in the landscape ?

There are lots of benefits to it. If you talk about drystane dyking, like the traditional way that is used for enclosure and for livestock, it provides really great protection for them across the landscape. You can create shelter from these structures for lots of animals, insects or larger animals like sheeps with lambs. Also the walls across the fields that kind of acts as protection for them. But even without considering animals, it built environments in the Highlands and islands, if you see when the snow comes across the landscape and the way the dyke sort of acts as a buffer to different parts of the roads and things like that. But then also it has an impact in a less tangible sense on how we feel about the place and how we engage with the structures that are into what we consider like the natural environment and wild places. So it has an impact on how we perceive a place. If you see a wire fence with wooden posts, it doesn’t evoke the same sense of history. It’s history and heritage. Once the dyke, that has been in place for a long time, starts to become a home for all these mosses and lichens, you feel like it is part of that landscape and you can’t really imagine it not being there anymore. And it’s that that ties people to the place that they habit.

What are the main bibliographic sources of your PhD ?

There’s a big variety because, yet dry stone is at the center of my research, it’s important for me that I fit into these ongoing discussions about craftsmanship and how we value it. Then intangible cultural heritage more broadly as well. There’s some great books on the subject of dry stone walling. My absolute favorite when I started was a book called Dry Stone Dyking in Deeside by Robin Callander, and he’s just gone above and beyond to dive into the history of drystone dyking in that area from really historical accounts of pay and conditions for workers and how they pass knowledge from each other. One of my favorite facts is that the side that you were more comfortable working on of the wall would depend on what side your father had learned on, because then he would probably pass that on to you and then your dominant insight would be opposite to his. I would never have known that otherwise. I really recommend that book.

And then there’s another book, which was one of the first books with popular interest about drystane walling that has been continuously produced called Dry stone walling by RainsfordHannay, who was one of the first people who kind of moved what was formerly another association towards being the Dry Stone Walling Association. It kind of tracks a little bit of the history of how that came to be because obviously the Dry Stone Walling Association has a really big impact on how this skill is passed on and perceived in the country. So it’s really great to have a bigger understanding of that. But they have produced quite a lot of different books that you can find through the Dry Stone Association about that too.

If I think more broadly, I’ve read a lot about crafts through, there’s these great book The Nature and Art of Workmanship by David Pye, who was a craftsman himself. He developed this theory of workmanship of risk and workmanship of certainty. The craft with volunteer workmanship of risk where the outcome is not very predefined and your drive to create something of quality and serve with pride is very integral to that. Whereas maybe workmanship of certainty would be replicating something or creating something that you can replicate again and again.

Also Richard Sennet was quite an integral sort of launchpad for me. He has a book The Craftsman, what it means to sort of take pride in it. But it also sets into bigger pictures of capitalism and our place for craftsmanship within these systems where we don’t necessarily value a job well done anymore in the same way. And he advocates for that place.

Tim Ingold has been really a very guiding thinker on craftsmanship and the way that it relates to the landscape as well. So I’d really recommend a lot of his books, or his papers as well because they’re not all, but he has some collections which are really useful.

Did you participate in any dry stone wall construction ?

So my first experiences of working with dry stone happened after I’d gotten into this project and they were both two very different experiences, but both incredibly valuable. It just really highlight

to me the regional variations that we are part of this sort of culture of working with dry stone here is that where you learn has a big impact, even though Scotland is very small, if you learn in the borders, the skills that you learn compared to what you learn in Orkney are just completely different. And what teachers you will have has a really big impact on the way you learn. So my first experience of building was at the North Ronaldsay ship Festival in Orkney, in Skara Brae on the Orkney mainland. There’s some incredible dry stone like the Neolithic structures at Skara Brae, and they also have Brochs, from the Iron age that are unique to Scotland. They have lots of examples of that on the Orkney mainland. In the Orkney’s most northerly outer island, which is called North Ronaldsay, they have a sheep dyke which runs around the entire outer periphery of the island along the shore. It’s about 13 miles long and it keeps their specific breed of sheep, which is the North Pole Sea sheep on the shoreline, because they have over time evolved to eat seaweed. So it keeps them on the shore where they eat seaweed. Every year they’ve developed this voluntary festival where people come from all over to help maintain that structure, because over time their population has slightly decreased and is an aging population. The dyke was maybe just like falling into disrepair and it was having an impact on the way they kept the sheep and how the island’s sort of community. Because the sheep are quite central to their economy as a source of meat, wool and they’re quite sought after in that way. So they have this voluntary festival, which is a week long and you can be a complete beginner. But there were also people who had done it loads of times before, so it’s like a big mixture. I went along and I just spent the week with other volunteers learning from scratch. They build in a way that’s quite specific to the island because it’s on the shoreline. You’re using stones that are directly from the beach and they don’t have hearting in the middle like a lot of the structures that we have here, they’re very goofy because you want the sand and the wind to blow through it rather than come up against the solid wall. So I was learning in this way that was really satisfying in that specific way.

Then I went and did the Dry Stone Walling Association beginners course near Edinburgh, it was like a completely different way of building and I’m so glad I have the two experiences so far myself. We were building with sandstone and using tools which I hadn’t used at all when I was working in North Ronaldsay and it was just such an eye opening experience for me to be, with my head in the books a lot of the time thinking about this craft, but it is absolutely essential that I did it myself because it completely changed the way I relate to it and think about it. Hopefully as my fieldwork goes on, I’ll get stuck in wherever I can and it’ll just be a continuous journey of learning and hopefully improving slightly.

How do you plan to use what you learned in your future professional experiences ?

I feel like I’m in a really lucky position in that. I study with the University of the Highlands and Islands and I do this research alongside an industry partner who is in Historic Environment Scotland to work to preserve Scotland’s major or minor as well, historical and heritage sites. And this work hopefully informs how they approach the passing on of the skill and the teaching of it in their structure. I feel like at the moment, how the direction that this will have on me personally, to be able to say that the work that I do hopefully contributes to a better understanding of how we preserve this craft and teach. I would be really pleased if it had that kind of outcome. Then I don’t see myself being a full time drystone waller. I think everyone will be glad to know that’s not on the cards for me. You never know, I might become better at it, but I hope to sort of work with dry stone again. But I love this sort of type of research, which is really community orientated. And you can see that the outcome hopefully does have some sort of benefit to the people that work alongside in the creation of this thesis. If I could stay in an environment that looks at how communities become more resilient throughout Scotland and use the skills that are already there and relate to the heritage that belongs to them in a way that fits into a broader understanding of sustainable development going forward. That would be great if that was possible in some way.

Nous tenions tout d’abord à remercier nos professeurs Magali Paris et Jean Patrice Calori qui nous ont encadrées tout au long de ce semestre, avec des discussions toujours enrichissantes. Nous remercions toutes les personnes qui ont croisé notre chemin en Écosse ou ailleurs et qui nous ont apporté leur vision sur notre analyse et projet. Enfin, nous remercions nos amis et notre famille qui ont été d’un grand soutien durant ces années d’études et particulièrement sur ces derniers mois. Nous espérons que cette recherche prendra une dimension supplémentaire et nous suivra durant le début de notre entrée dans le métier d’architecte.

MERCI.

Édition d’un livret dans le cadre d’un projet de fin d’études à l’École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles sous la direction de Magali Paris & Jean-Patrice Calori.

Projet soutenu en juin 2024.

Autrices / Océane Debard & Camille Piraud

Polices / ABC Diatype Unlicensed

ABC Arizona Serif Unlicensed

Papiers / intérieur 90g couverture 250g

Impression / COREP

75003 Paris

Projet de fin d’études

Ce livret retrace l’analyse et le voyage d’étude effectués en avril 2024 dans le cadre de notre projet de fin d’études à l’École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles. Le sujet porté par ce diplôme commence avec une analyse du «déjà-là» par le prisme des constructions en pierre sèche en Écosse, à travers différents médiums : le dessin, le relevé, la photographie et la vidéo,

Durant le voyage, il a été important pour nous de rencontrer des acteurs de l’artisanat de la pierre sèche et d’échanger avec eux. Nous avons ainsi participé à un workshop de réparation d’un mur en pierre sèche qui nous a permis de nous familiariser avec sa construction, d’apprendre de nos mains et de réaliser des entretiens avec trois personnes travaillant ce savoir-faire.

Ces rencontres ont fait l’objet de la réalisation d’un film «ON THE DRYSTANE* ROAD» qui documente le voyage et retrace ces échanges.

Cet ouvrage s’inscrit dans une démarche forte de restitution d’une analyse sensible et essentielle, entamant un début de problématisation autour des ruines en pierre sèche qui émergent dans le paysage de l’île de Lewis.

Océane Debard & Camille Piraud

ENSAV

Sous la direction de Magali Paris & Jean-Patrice Calori

juin 2024