Mtro. Hugo Antonio Avendaño Contreras

RECTOR

Dra. Gabriela Martínez Iturribaría

VICERRECTORA

Mtro. Marco Antonio Velázquez Holguín

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ADMINISTRACIÓN Y FINANZAS

P. Miguel Ángel Ramírez Flores, MG

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE FORMACIÓN INTEGRAL

P. Gerardo López Vela, MG

INSTITUTO INTERCONTINENTAL DE MISIONOLOGÍA

Boletín del Colegio de Estudios Guadalupanos

EDITOR

Arturo Rocha Cortés

CONSEJO EDITORIAL

Gustavo Watson Marrón

Ramiro Gómez-Arzapalo Dorantes

David Sánchez Sánchez

Alberto Hernández Ibáñez

Arturo Rocha Cortés

BOLETÍN DEL COLEGIO DE ESTUDIOS GUADALUPANOS, Año 4, No. 7, enero – junio 2024 es una publicación semestral editada por la UIC Universidad Intercontinental, A.C., calle Insurgentes Sur 4303, Col. Santa Úrsula Xitla, C.P. 14420, Tlalpan, Ciudad de México. Tel. (55) 5487-1300, www.uic.mx. Editor responsable: Arturo A. Rocha Cortés. Reserva de Derechos al Uso Exclusivo No. 04-2020-040100080300-102 otorgado por el por el Instituto Nacional del Derecho de Autor. ISSN: 2954-4157. Número de Certificado de Licitud de Título y Contenido otorgado por la Comisión Calificadora de Publicaciones y Revistas Ilustradas: En trámite. Responsable de la última actualización de este número: Arturo A. Rocha Cortés, Colegio de Estudios Guadalupanos (COLEG), calle Insurgentes Sur 4303, Col. Santa Úrsula Xitla, C.P. 14420, Tlalpan, Ciudad de México. Fecha de última modificación: 30 de junio de 2024.

Los juicios y opiniones vertidos en esta publicación son responsabilidad exclusiva de quien(es) los emite(n) y no representan necesariamente la visión o filosofía de la Universidad Intercontinental (UIC) ni de los Misioneros de Guadalupe.

PRESENTACIÓN

Dr. Arturo A. Rocha Cortés 7

Danza guadalupana: tradición y actualización

P. Ernesto Mejía Mejía 9

De los excesos cristológicos en versiones castellanas de Nican mopohua vv. 27-28

Dr. Arturo A. Rocha Cortés 19

An Indigenous Canonization. The Journey of Juan Diego to the Altars

Mtro. Jorge Arredondo Sevilla 27

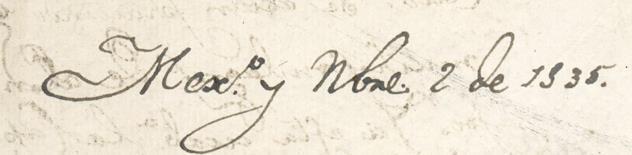

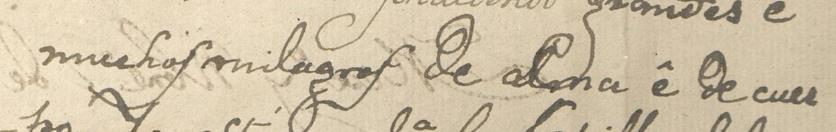

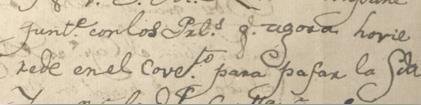

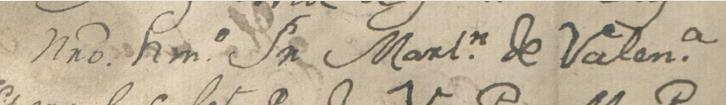

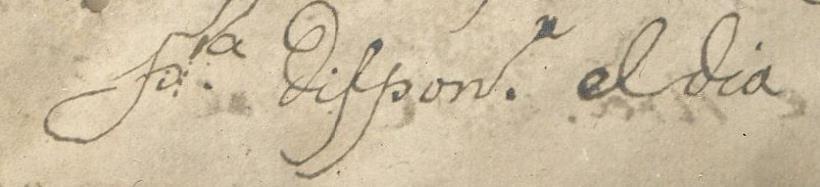

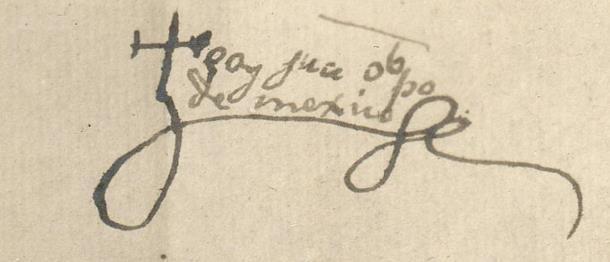

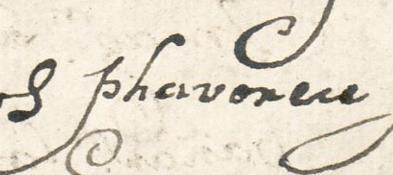

Análisis del Documento de Huejotzingo: Fray Juan de Zumárraga y el Acontecimiento Guadalupano

Dr. David Sánchez Sánchez 63

Dr. Arturo A. Rocha Cortés

El presente número del Boletín del Colegio de Estudios Guadalupanos nos ofrece cuatros artículos muy interesantes. El primero desarrolla un tema que se inscribe de lleno en el ámbito de la religiosidad popular, en su expresión de danzas y bailes de exaltación guadalupana. Se trata de sintéticas reflexiones, iluminadas desde la antropología y la teología, con las que el P. Ernesto Mejía Mejía, CMF. Ingresó en el Colegio de Estudios Guadalupanos como miembro ponente.

En un segundo momento, el editor de este instrumento de difusión de la investigación guadalupana repone una pieza sobre el relevante asunto de la cristología subyacente en el texto prístino de las apariciones de la Virgen de Guadalupe a su vidente Juan Diego: el Nican Mopohua. Diversas traducciones, en diferentes lenguas, del valioso texto tienden a exagerar el carácter cristológico de ciertos versículos en los que el P. Torroella dividió el relato mariofánico. Con la intención de no violentar lo que en efecto dice la lengua náhuatl en lo relativo a la amor que la Virgen de Guadalupe entrega a la gente, se presentan aquí estas consideraciones filológicas, apoyadas en textos de frailes del siglo XVI.

Seguidamente, el boletín se engalana con un interesante artículo que pormenoriza el derrotero que siguió la canonización del indígena san Juan Diego, en una precisa exposición que conjuga el contexto ideológico e histórico de la política mexicana de aquellos años, con los pormenores de la existencia histórica del vidente del Tepeyac. Este artículo pone en blanco y negro el tema de la conferencia con la que ingresará como miembro ponente del COLEG, el maestro Jorge Manuel Arredondo, doctorante de teología de la Universidad de Notredame y maestro en Estudios Teológicos de la Escuela de Divinidad de Harvard.

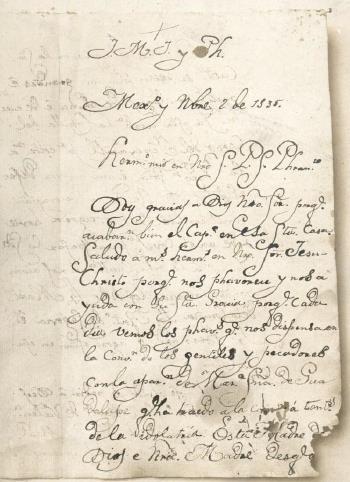

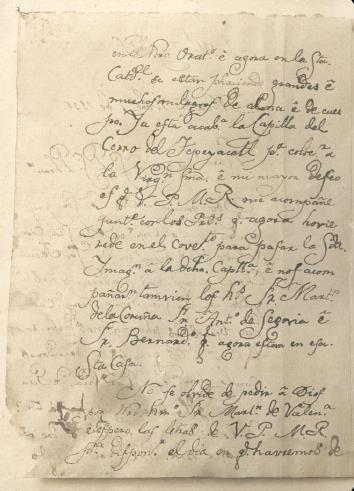

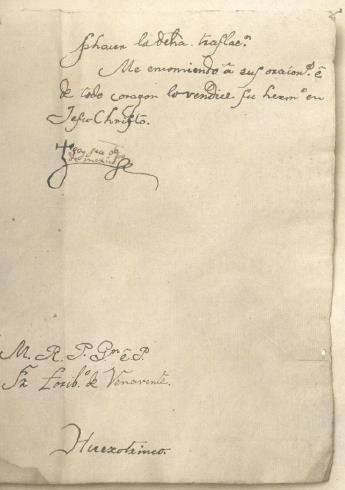

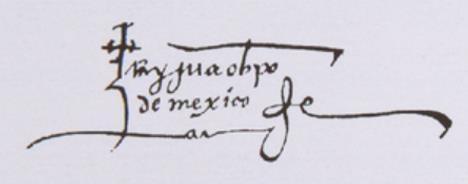

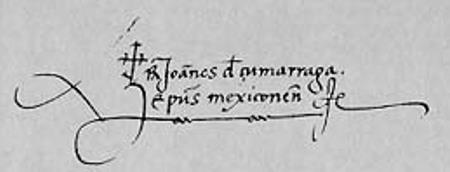

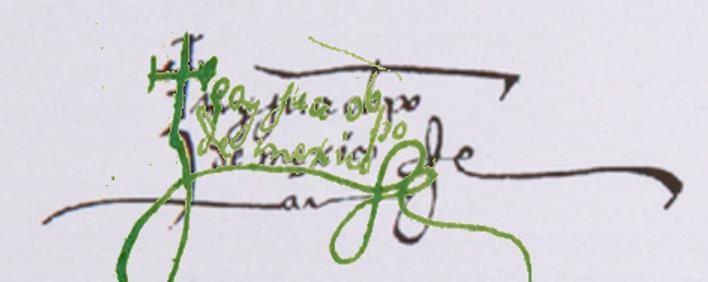

Cierra el número un artículo que será base de estudios posteriores: el análisis de un documento perteneciente a la Biblioteca del Seminario Palafoxiano y conocido como Códice de Huejotzingo. Este manuscrito, claramente una mistificación, brinda pábulo a su autor, el doctor

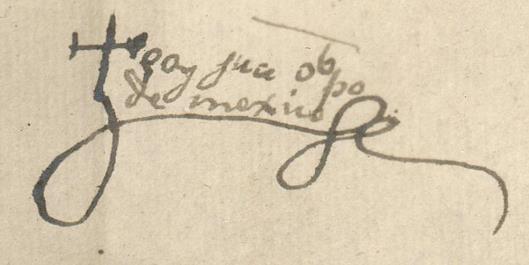

David Sánchez Sánchez, historiador español, presidente del Centro de Estudios Guadalupanos (CEG) de la UPAEP, para realizar interesantes comparaciones entre la holografía zumarragiana auténtica y la espuria, generada ésta en un artificial y vano afán de subsanar la falta de alusiones a la aparición guadalupana de parte de quien fuere el privilegiado testigo de la imprimación: el obispo fray Juan de Zumárraga. Estas dos últimas piezas del número 7 de nuestro Boletín del Colegio de Estudios Guadalupanos motiva su portada, en la que utilizamos la obra de Miguel Cabrera: Retablo de la virgen de Guadalupe con san Juan Bautista, fray Juan de Zumárraga y Juan Diego, perteneciente a la colección del Museo Nacional de Arte de México. A los pies de la Celestial Señora apreciamos, a la derecha, al primer santo amerindio, Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, y a la izquierda, al primer obispo de México, fray Juan de Zumárraga.

P. Ernesto Mejía Mejía†

ABSTRACT: La importancia del Acontecimiento Guadalupano nos invita a repensar la diversidad de sus manifestaciones, una de ellas, es lo que desde la religiosidad popular se denomina Danza guadalupana. Diversas disciplinas siguen estudiando este Acontecimiento Guadalupano, pero, en este estudio nos dejaremos iluminar por la antropología y la teología; ya que, hablar de la Virgen de Guadalupe es un aspecto que marca la vida de nuestra nación mexicana, también impulsa nuestra vida como creyentes bajo ese rostro materno de quien fue la primera discípula misionera y quien decidió impregnarse en la cultura mexicana en un rostro mestizo.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Religiosidad Popular. Acontecimiento Guadalupano. Danza. Cuerpo. Identidad.

ORÍGENES DE LA DANZA

Hagamos una visión retrospectiva y nos daremos cuenta de que la danza es un acontecer intrínseco en la vida de la humanidad, la danza es una manifestación que ha aparecido en todas las culturas, desde las

* El texto aquí publicado es el resultado de la incorporación del autor al COLEG, el jueves 30 de mayo de 2024.

† Misionero Claretiano. Lic. en Antropología Social (ENAH). Mtro. en Pastoral Urbana. (Universidad Católica Lumen Gentium).

culturas primigenias hasta nuestros días. Cabe señalar que existen datos de la danza muy, muy antiguos en la india, también en china, Grecia y Roma. De ahí que podemos ubicar a la danza como un elemento esencial en el ser humano. Algunos antropólogos y arqueólogos sustentan que la danza fue el primer medio de comunicación, antes del lenguaje y la escritura.

En los orígenes de la humanidad la danza trata de reflejar la armonía existente en el cosmos (todo él es movimiento y armonía). La danza aparece con diferentes connotaciones, danzas festivas, danzas lúdicas… y las danzas religiosas. Así hablamos de las Danzas Guadalupanas que guardan y expresan todo un fuerte sentido ritual; en las cuales se encuentra el creyente (danzante o espectador), en las cuales interactúa el pueblo, en donde el ser humano estrecha una relación con lo trascendente. Así podemos hablar de una articulación, una lógica religiosa de movimiento, la rítmica como comunicación con lo religioso.

Algunas veces, algunos se preguntan si las danzas están permitidas dentro del ambiente católico o son únicamente expresiones espontaneas o profanas que se han indo insertando. Las Sagradas Escrituras, sobre todo el Antiguo Testamento tiene muchas referencias en las cuales el pueblo de Israel se manifestaba corporalmente, a través del ritmo, de la música, del canto, de la propia danza. Recordemos la cita bíblica del rey David: “Y David danzaba con toda su fuerza…” (2 Samuel 6,14). Los Salmos como el 30 y el 149 también hacen referencia a cantos, alabanzas y ritmo de danza. Hay que expresar que la danza está aceptada dentro del ámbito religioso, que no es una adhesión, que no es algo profano, el riesgo o lo no aceptado es cuando hay excesos, cuando se pierde el respeto por lo religioso o se pasa por alto el cuidado por el bien común. El Nuevo Testamento también refleja algunas danzas, dentro de ellas la que podemos recordar, con una connotación muy negativa es la danza que se utilizó como pretexto para dar muerte a Juan el Bautista.

Entonces, no se puede negar que se ha venido dando una manifestación dancística válida dentro de la religión católica, muchas de ellas con un fuerte aspecto de inculturación, y donde la religiosidad popular se manifiesta con gran respeto y creatividad, esta religiosidad popular

a la que el Papa Francisco se expresa como un “tesoro que tienen los pueblos originarios”. Aunque él mismo prohíbe los desvíos y alerta ante los excesos. Con esta guarda, este gran tesoro que es la religiosidad popular a través de la Danza Guadalupana lo encontramos en nuestra nación mexicana, desde el norte hasta el sur. Invito a tener una mirada especial a las Danzas Guadalupanas (enmarcadas dentro de las Peregrinaciones Guadalupanas) en la Parroquia de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, en la ciudad de Torreón Coah., en donde del 1 al 11 de diciembre el primer cuadro de dicha ciudad se ve cubierto de danzantes con sus vistosos bailes y atavíos.

Partimos de un compromiso del creyente: “Todo bautizado es discípulo misionero”. Por consecuencia, si el que danza está bautizado es un discípulo misionero. Muchos de ellos llevan una vida ejemplar. Muchos de ellos como cualquier otro ser humano están en esta dinámica del aquí y ahora, de la mejoría en su vida. De esto, el escenario de la danza y del danzante se hace más profundo, al que danza no solamente se le percibe en cuanto al desgaste físico, el elemento corporal, la comunicación o por su devoción. Si el que danza está bautizado, es todo un discípulo misionero o debería de serlo. De tal suerte que cuando nos acercamos a un danzante, tenemos que ver en él a un agente importante de evangelización.

Estos dos términos parecerían polarizados, sin embargo, si está de por medio el acontecimiento guadalupano, se da necesariamente el elemento de la continuidad. Hay una tradición, pero como un constructo histórico, una línea del tiempo que va describiendo toda una historia nacional, que manifiesta toda una cultura, que describe transformaciones, pero es un “continuo”, ya que el Acontecimiento Guadalupano desde la fe, es un acontecer diario.

Aunque la danza refleja todo el pasado de los pueblos originarios, por su parte, la actualidad se nota en los atuendos, el tipo de guaraches, en la belleza de sus plumajes, en los ritmos y muchos otros aspectos que se han ido implementando.

Pero, hay algo interno que no cambia, como el deseo del encuentro, el respeto y la esperanza hacía la Virgen de Guadalupe. Se actualizan muchos aspectos externos, pero,

podemos decir en este “continuo”, que el corazón del creyente, del danzante: la fe es la misma. El encuentro de aquel que cree, de la comunicación de aquel que desea, de una nación que se siente cobijado por expresiones tan maternales, tan cercanas y llenas de protección: “No estoy yo aquí que soy tu Madre”. La certeza: “Yo represento al Dios del Cerca y del junto”. La cercanía: “Yo quiero que se me construya una

casa para estar cerca de ti, para escuchar tus lamentos”. Este “continuo” que es el Acontecimiento Guadalupano genera este vínculo, esta bella expresión de todo este acontecer dancístico. La tradición y la actualidad se unen en un rostro femenino, en un rostro materno que da cuidado, que da cobijo, que da esperanza. Entre lo tradicional y lo actual cambian muchas cosas en este devenir. Pero, en medio de todo esto, hay una persona que acompaña, que es la Virgen de Guadalupe. Entonces, podemos detenernos y remarcar que, dentro de una tradición, de un “continuo” cultural e histórico, dentro de una actualización hay elementos no negociables que no tienen fecha de caducidad, y que no solo entran en dinámicas temporales, sino también metahistóricas; manifiestas en la presencia de una Virgen, de una Madre que cuida, pero lo que le da mucha actualidad es el aspecto de que la danza es un vehículo de comunicación en constante movimiento. Y esto como Iglesia católica hay que valorarlo mucho.

¿POR QUÉ DANZA GUADALUPANA?

Ahora bien, ¿que sería lo específico de las Danzas Guadalupanas? Lo que le da la especificidad es encontrase con una persona, con una Madre. En algunas entrevistas realizadas a jóvenes danzantes de Torreón, Coah., expresan que al danzar se encuentran con alguien, se encuentran con una Madre que acoge, con una Madre que da esperanza, con una Madre que valora las diversas formas de acercarse a Ella. Esto es lo que también genera una manera propia de entender toda la ritualidad de la danza guadalupana.

La Danza Guadalupana es otra manera de acercarse a la Virgen; ahí encontramos también una actualización no de una manera formal, no de una manera prescrita, sí de una manera vivencial. El joven, la joven danzante sabe que hay un encuentro con alguien y este alguien es la Virgen Morena y desde esta manera de encuentro, de relación, de contacto a través de la danza, se genera un ritual religioso propio y una actualización a través de los más variados ritmos. Y una singularidad muy importante es la presencia juvenil a través del propio cuerpo.

DANZA: LENGUAJE CORPORAL

Al hablar de la actualización, debemos de hacer un énfasis en el aspecto del cuerpo, la corporeidad. Hay una cita bíblica en la que San Pablo nos pone el ejemplo del cuerpo, en donde la Cabeza del cuerpo es Jesucristo. Es decir, toda una teología del cuerpo. Podemos retomar esta cita bíblica, no en el nivel de la exégesis o de la hermenéutica, pero sí de una narrativa bíblica y aplicarla a la danza, ya que, en ésta, el cuerpo es un elemento primordial. A través del cuerpo vemos un nuevo lenguaje religioso, toda una ritualidad, que puede ser de gran actualidad en nuestros días.

La posmodernidad habla del cuidado del cuerpo. Y vemos que el cuerpo en la danza manifiesta un vínculo de comunicación, de

cercanía con la Virgen Madre, con la Virgen Morena. Los que danzan saben de la importancia del cuerpo. La danza es todo un arte, toda una armonía, toda una estructura, pero también hay un desgaste físico, hay un desgaste del cuerpo. En la danza hay rostros de jóvenes que llegan literalmente sudando, algunos de ellos con los pies lacerados… ahí está jugando un papel importante el cuerpo, el cuerpo que habla, el cuerpo que es encuentro, el cuerpo que está manifestando un mensaje actual. De tal suerte que los movimientos corporales son los vasos comunicantes, que tienen como cabeza a Jesucristo, y como corazón a la virgen de Guadalupe.

El Acontecimiento Guadalupano en sí es una actualización. Tiene una frescura, tiene una novedad, y se nota cada 12 de diciembre. Como creyentes hay que darle gracias al “Dios del Cerca y del junto”, porque esta Madre Virgen decidió estar en nuestra nación y no solamente cada 12 de diciembre, sino, día con día. Es un acontecer que tiene como centro la Buena Noticia que es Jesús. Es innegable que las danzas se siguen reactualizando, sin embargo, los propios danzantes, dicen: Cambian los ritmos, pero lo que no cambia es nuestra fe, nuestra devoción y nuestro respeto hacia la Virgen.

La Danza Guadalupana en sí tiene una connotación religiosa, es todo un escenario guadalupano. Se sabe que hay algunos danzantes que cobran, algunos danzantes a lo mejor no son creyentes, pero esto no está generando una danza profana, sino una danza religiosa, la danza guadalupana. Sí, se debe tener cuidado en las danzas que quizá tienen otros fines, pero, por lo regular si alguna danza guadalupana tuviera algunos excesos los mismos danzantes, los devotos observadores lo marcarían, lo reprobarían. Si se habla de una Danza Guadalupana es porque hay una tradición, existe un respeto, pervive una herencia, exige toda una preparación y se genera una identidad religiosa.

Un valor muy importante es que la Danza Guadalupana genera una identidad religiosa y en dicha identidad se ve manifiesto un personaje concreto: el joven.

La danza manifiesta necesariamente un renuevo, que incluso se da por tradición familiar: se ve al abuelo, a la abuela, a la mamá o al papá llevando ya desde pequeño al niño o a la niña, vestidos de danzantes. Ya desde temprana edad esto va generando una manera de acercamiento, un vínculo con la Virgen de Guadalupe. Así, se da una identidad religiosa juvenil, ya que la mayoría de los danzantes son niños, adolescentes y jóvenes. Y esta identidad religiosa es fundamental para la iglesia católica.

Dr. Arturo A. Rocha Cortés†

ABSTRACT: Una estricta revisión de la versión castellana de dos versículos esenciales del relato de las apariciones de la Virgen de Guadalupe al indio Juan Diego. Una traducción excesiva o un forzamiento del náhuatl perpetuado por algunos autores, ha dotado a ambos versículos del Nican Mopohua de una carga cristológica que en la lengua mexicana no poseen en absoluto. Este artículo corrige de una vez por todas los excesos de traducción, dejando a salvo el ámbito para ulteriores elaboraciones exegética.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Nican Mopohua, Virgen de Guadalupe, Cristología, P. Mario Rojas, Fr. Andrés de Olmos.

Uno de los momentos más hermosos y exaltados de la relación náhuatl de las apariciones de la virgen de Guadalupe, el Nican mopohua, es ciertamente aquel en que la celestial Señora, tras referirse a su Divino Hijo con la relación de los atributos teológicos más acendrados del México antiguo,1 instruye puntualmente al indio Juan Diego: “…huel

* Artículo publicado previamente en la revista Voces. Revista de Teología Misionera de la Escuela de Teología de la Universidad Intercontinental, Publicación Semestral de la Escuela de Teología de la Universidad Intercontinental, Año 18, no. 35 (2011), ed. Arturo Rocha, México: UIC, pp. 123-129.

† Director Académico del Colegio de Estudios Guadalupanos (COLEG) de la UIC.

1 “…ca nêhhuatl in niçenquizca çemicac ichpochtli santa maria in inn inantzin in in huel nelli teotl Dioz in ipalnemohuani in […] teyocoyani, in tloque Nahuaque: in ilhuicahuah in tlalticpacque…” [Antonio VALERIANO], Nican mopohua, vers. 26: NYPL, Ms. 379 Guadalupe, México (ca. 1548), Monumentos Guadalupanos, serie I, t. I, ff. 191r-198r. El

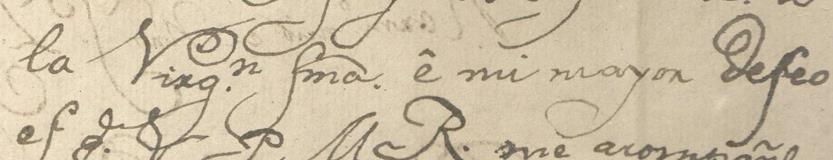

[…] nicnequi, çenca nicelehuia inic nican nechquechilizque noteocaltzin inn oncan nicnextiz, nicpantlaçaz nictemacaz in ixquich notetlaçotlaliz, noteicnoyttaliz, in notepalehuiliz, in notemanahuiliz…”,22 que literalmente significa: “Mucho quiero yo, mucho así lo deseo que aquí me levanten mi casita divina, donde mostraré, haré patente, entregaré a las gentes todo mi amor, mi mirada compasiva, mi ayuda, mi protección…”;3 nada más.

La cuestión es que otros autores como el gran campeón del guadalupanismo, P. Mario Rojas, han traducido el pasaje náhuatl in oncan nicnextiz, nicpantlaçaz nictemacaz in ixquich notetlaçotlaliz, noteicnoyttaliz, in notepalehuiliz, in notemanahuiliz como: “en donde Lo mostraré, Lo ensalzaré al ponerlo de manifiesto: Lo daré a las gentes en todo mi amor, en mi mirada compasiva, en mi auxilio, en mi salvación…”,4 con lo que a nuestro juicio y dicho con todo respeto a la persona del recientemente desaparecido sacerdote , es violentar el náhuatl al extremo de hacerle decir… lo que no dice.

El asunto resulta tanto más relevante cuanto estos dos versículos del Nican mopohua son los que se aducen en infinidad de ocasiones para apuntalar prácticamente toda la cristología de la narración del sabio Antonio Valeriano. Y no estamos señalando meras accidentalidades: el P. Rojas y quienes siguen su versión del náhuatl (o sea, una buena

lugar citado corresponde al f. 192v. Véase: Arturo ROCHA, Monumenta Guadalupensia Mexicana. Colección facsimilar de documentos guadalupanos del siglo XVI custodiados en México y el mundo, acompañados de paleografías, comentarios y notas por…, con una presentación de Mons. Diego Monroy Ponce, Vicario General y Episcopal de Guadalupe, Rector del Santuario. Palabras preliminares de M. I. Mons. José Luis Guerrero, Miembro del V. Cabildo de Guadalupe. Prólogo del autor, México: Insigne y Nacional Basílica de Santa María Guadalupe/ Grupo Estrella Blanca, 2010, p. 11.

Véase también: Arturo ROCHA, “Nican Mopohua”, Boletín Guadalupano. Información del Tepeyac para los Pueblos de México, año III, núm. 38 (feb. 2004), 7-11 pp., México: Insigne y Nacional Basílica de Guadalupe, p. 9.

2 Nican mopohua, vv. 27-28: NYPL, Ms. 379…, cit., ff. 192v-193r. Cfr. ROCHA, “Nican mopohua”, Boletín guadalupano…, cit., pp. 9-10.

3 Vid. Miguel LEÓN-PORTILLA, “Nican mopohua. Traducción del náhuatl de…”, in: Ana Rita VALERO, Arturo ROCHA, Miguel LEÓN-PORTILLA, Diego MONROY, et al., Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, presentación de Norberto Cardenal Rivera Arzobispo Primado de México, proemio de Manuel Ramos Medina, México: Insigne y Nacional Basílica de Guadalupe/ DGE Equilibrista, 2005, 19- 39 pp.; pp. 23-24.

4 Vid. ROCHA, Monumenta Guadalupensia Mexicana, pp. 11 y 13.

cantidad de autores), escriben incluso con mayúscula el artículo “Lo”: “Lo” ensalzaré, “Lo” daré a las gentes para que no quede la menor duda de que Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe se refiere a su Hijo Jesucristo.

La pregunta obligada es la siguiente: ¿Esto es así efectivamente? ¿Dice María de Guadalupe en NM, 27-28 que va a ensalzarlo a Él (a Cristo), que lo dará a Él a las gentes, y además, en todo su amor (de la Virgen), en su mirada compasiva, en su auxilio, en su salvación?

La respuesta podrá hasta enfadar a muchos, pero la verdad es que el náhuatl no dice aquello. Y si bien de las palabras de María de Guadalupe puede realizarse la interpretación exegética de que Ella se está refiriendo a Cristo Jesús (pues, a final de cuentas, Él, su Divino Hijo, es lo que entrega a las personas a través de su amor de madre), lo cierto es que aquellos “Los” para nada están presentes en los versículos en lengua mexicana.

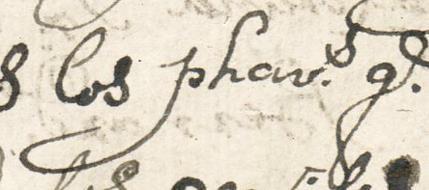

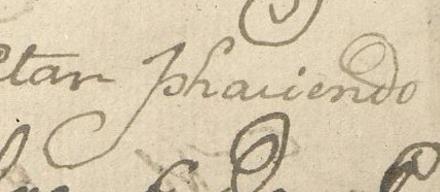

Examinemos el tema. Tras los verbos en futuro nicnextiz, nicpantlazaz, nictemacaz (que no quieren decir nada distinto de “[yo] mostraré”, “[yo] patentizaré”, “[yo] entregaré”) viene el meollo de la cuestión, pues Nuestra Madre dice a Juan Diego in ixquich notetlazotlaliz, lo que literalmente significa: “todo mi amor [a las personas]. La partícula no(“mi”, “mis”) hace las veces de adjetivo posesivo.

Pero es a la partícula te- a la que hay prestar más atención, Por ejemplo, como enseña Rémi Siméon, hablando del complemento de las oraciones nahuas, cuando éste no está expresado, “se utiliza el pronombre indefinido te para las personas y tla para las cosas”;5 como cuando se dice nite-tlazotla, “amo a alguien o a la gente” o bien nitlatlazotla, “quiero una cosa o las cosas”.

Andrés de Olmos [ca. 1480-1571], fraile franciscano, lengua de lenguas del náhuatl, enseña esto mismo en el cap. VII de su Arte, a propósito de algunas partículas que se juntan con los verbos activos:

Tla. - Esta particula tla denota que la acción del verbo a quien se ayunta puede generalmente conuenir, o puede pasar en cosas inanimadas o animadas, aunque por la mayor parte se pone para denotar cosas inanimadas, y quiere

5 Rémi SIMÉON, Diccionario de la lengua náhuatl o mexicana, redactado según los documentos impresos y manuscritos más auténticos y precedido de una introducción por…, México: Ed. Siglo XXI, 172004 [Colección América Nuestra. América Antigua], p. LXXVI.

decir lo que en nuestro romance decimos: algo. Ex.: nitlatlaçotla, amo algo. […]

Te. - Esta particula te denota que la acción del verbo passa en cosas animadas y por la mayor parte se dize de cosas racionales. Esta quiere decir: alguno, no señalando quien. Ex.: nitepaleuia, ayudo a alguno. […] [sic]6

En suma: tla y te son partículas que indican que la acción de los verbos con los que se vinculan se da con “algo” o bien con “alguno”, respectivamente. Más todavía, Olmos enseña que la partícula te significa “alguno, no señalando quién”, por lo que no se la podría “personificar” o hipostasiar en alguien específico (como podría serlo el Hijo de Dios).

Estas partículas tla y te funcionan de la misma manera en los verbales sustantivos es decir aquellos que “significan la action y operation del verbo, assi como enseñança o doctrina [sic]”,7 y que suelen acabar en liztli los cuales son, huelga decir, precisamente de la forma de los que venimos discutiendo.

Sobre estos sustantivos enseña Olmos lo siguiente:

Estos no tienen plural. La formacion dellos es del futuro del indicatiuo boluiendo la tercera persona en liztli Ex.: tetlaçotlaz, aquel amara; tetlaçotlaliztli, el amor con que aman a otros. […] Y los que salen de verbos actiuos pueden tomar las particulas tla, te, ne, porque si vienen de verbos neutros que no tuuieren nino, timo, etc. no las pueden rescebir. [sic]8

Pero también señala que “con los pronombres no, mo, y, etc. pierden el tli […] Ex.: techicaualiztli, esfuerço, notechicauliz, mi esfuerço con que esfuerço a otros [sic]”.9

Por eso en los versículos del Nican mopohua que comentamos no se escribe notetlazotlaliztli, sino notetlazotlaliz, pues tlazotlaliztli pierde el tli al recibir el pronombre no-. Podríamos enunciar el ejemplo casi

6 André de OLMOS, Grammaire de la langue náhuatl ou mexicaine, composée, en 1547, par le franciscain…, et publiée avec notes, éclaircissements, etc. par Rémi Siméon, Paris: Imprimerie nationale, M DCCC LXXV [1875], segunda parte, cap. VII, pp. 122-123.

7 Ibid., primera parte, cap. IX, p. 42.

8 Id

9 Ibid., p. 43.

en palabras de Olmos: “tlazotlaliztli, amor, notetlazotlaliz, mi amor con que amo a otros”.

En otras palabras: la partícula te en el notetlazotlaliz del versículo del Nican mopohua en cuestión , significa que la acción de dar “mi amor” (esto es, el de la Virgen de Guadalupe) se verificará con las personas. Pero ello no quiere decir que lo que María dará sea una persona. Dicho de otro modo, el pronombre indefinido te, subraya el carácter personal de la palabra tlazotla, es decir, que cuando esta acción se verifique (cuando se dé dicho amor) se verificará con las personas, pero no que sea precisamente una persona lo que se dará, y mucho menos una Persona (la Segunda de la Trinidad: el “Lo” de la versión de Rojas).

Se ha querido argumentar que en náhuatl “mi amor” se dice notlazotlaliz, y que lo que vuelve a esta palabra distinta de notetlazotlaliz es propiamente la partícula te, y como ésta se refiere a la persona, pues entonces no-te-tlazotlaliz significa “mi-personaamor” o “mi amor persona”.10 Pero esto es una fabricación, pues te no quiere decir “persona”, noción más propia de expresarse con sutiles difrasismos (como el in ixtli in yollotl explicitado por León-Portilla y López Austin) o aun por el propio náhuatl tlacatl. Este te es más bien una partícula referencial o un relativo de (o para) las personas, de (o para) los demás. No hay diferencia en que dicho pronombre indefinido se enlace con un verbo o con un sustantivo.

10 En esto se pliega literalmente el P. José Luis Guerrero al P. Mario Rojas, pues de éste tomó, a final de cuentas, todo el análisis filológico de la relación de Valeriano para su intento de exégesis. (Vid. José Luis GUERRERO, El Nican Mopohua. Un intento de exégesis, 2 vols., México: Universidad Pontificia de México, 1996 [Bibliotheca Mexicana, 67], t. I, cap. VIII, pp. 169 y 171-172). Janet Barber IHM, llega al extremo de traducir al inglés el “Lo” por “Him”, en “su” versión del Nican mopohua (verbatim de la de Rojas), perpetuando así el error: “…on which I will show Him, I will exalt Him, in making Him manifest…” (?), y aun nos endilga un “all my personal Love”: “I will give Him to the people in all my personal Love, in my compassionate Gaze, in my Help, in my Salvation…” (??) (J. BARBER, Nican Mopohua by Antonio Valeriano, c. 1548. Translated from the Spanish Version of the Rev. Mario Rojas Sánchez, 1978 by…, IHM, Ph. D., with Reference to the Nahuatl, apud GUERRERO ROSADO, op. cit., pp. 171-172, si bien el sacerdote no brinda la referencia exacta). En suma son el P. Mario Rojas, el P. José Luis Guerrero y Janet Barber quienes se adhieren a esta peculiar e inexacta traducción.

Es más sencillo todavía: En el Nican mopohua se desea insistir en el amor a la gente (no-te-tlazotlaliz) y no en el amor o querencia de o hacia las simples cosas (no-tla-tlazotlaliz).

Esta vinculación personalmente amorosa de Guadalupe ya ha sido subrayada en el ámbito teológico por los autores, alguno de ellos citado hasta por el propio Card. Joseph Ratzinger (huelga decir, hoy Romano Pontífice, Benedicto XVI) en un texto más o menos célebre.

En efecto, argumentando Ratzinger contra Karl Barth, a favor de la conectividad del cristianismo con otras religiones en la forma de adoración de Dios, de la liturgia y en modos de vida como el monacato, colocándose con ellas “en la continuidad del culto, aportando al mismo tiempo la renovación de los contenidos”, afirmaba el cardenal que:

(e)l ejemplo más impresionante de esta continuidad dentro del cambio es la Imagen de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Su culto empieza en el lugar en el que antes había estado la imagen de «nuestra venerada madre señora serpiente», una de las más importantes diosas indígenas. Pero el hecho de mostrar su cara sin máscara muestra «que no es una diosa, sino una madre de misericordia, puesto que los dioses indios llevaban máscara. Esto se amplía y profundiza por el símbolo del sol, de la luna y de las estrellas. Ella es mayor que los dioses indígenas porque oculta el sol, aunque no lo extingue. La mujer es más poderosa que la máxima divinidad, el dios sol. Es más poderosa que la luna, puesto que está de pie sobre ella, pero no la aplasta…». En las formas y símbolos en que aparece se ha incorporado toda la riqueza de las religiones precedentes y se ha reducido a una unidad desde un nuevo núcleo procedente de lo alto. Está, por así decir, por encima de las religiones, pero no las aplasta. De esta manera, Guadalupe es en muchos aspectos una imagen de la relación del cristianismo con las religiones. Todos los ríos confluyen en ella, se purifican y renuevan, pero no se destruyen. También es una imagen de la relación entre la verdad de Jesucristo y las verdades de las religiones: la verdad no destruye, sino que purifica y une”.11

11 Card. Joseph RATZINGER, “La unicidad y la universalidad salvífica de Jesucristo y de la Iglesia. Conferencia del cardenal… en un congreso celebrado en la universidad de Murcia”, L’Osservatore Romano, no. 3 [17 ene. 2003], 9-11 pp., p. 11, –el subrayado es nuestro. La cita también en la obra: Joseph RATZINGER, Caminos de Jesucristo, trad. de A. Quarracino, Madrid: Ediciones Cristiandad, 2005, pp. 72-73. (= Joseph RATZINGER, Unterwegs zu Jesus Christus, Augsburg: Sankt Ulrich Verlag GmbH, 203).

El Card. Ratzinger se apoya fundamentalmente en H. Rzcepkowki en su entrada “Guadalupe” del vasto Marienlexikon, editado por R. Baümer y L. Scheffczyk.

Pero este subrayamiento de la dignidad “visiva” de Guadalupe (en el que se constituye una elocuente prosopopeya del respeto, en tanto que re-mirar, o miramiento recíproco (re-spicio), cual hemos señalado en otros lugares)12 no autoriza tampoco a “sobreestablecer” o a “sobreestatuir” lo que el náhuatl del Nican mopohua dice en los mencionado versículos.

El que el dulce y desenmascarado mirar que Guadalupe dirige a sus hijos sea edificante y genuinamente “sanador”, aunque el amor de Ella lo sea, ello no autoriza a decir que dicho amor esté hipostasiado o que sea Su Hijo; al menos tal no dice el náhuatl. Lo que por otro lado para nada está reñido con cualquier exégesis razonable que en tal sentido se pueda hacer. Por ejemplo, “el tío Juan Bernardino es sanado tal puede interpretarse por el dulce y reparador mirar de Guadalupe. Pero no es Ella, la que sana, sino su Divino Hijo. Su mirar todo está impregnado de amor en el Resucitado, y éste es el amor que sana. En conclusión, su amor es Cristo. Luego, si Ella viene a dar su amor, entonces vienen a dar Cristo…”, etc., etc. Todo ello está muy bien… y equivale a subrayar toda la cristología subyacente en el mensaje de Santa María de Guadalupe. Pero no es eso lo que dice el náhuatl en los versículos discutidos sino, simple y llanamente, “daré todo mi amor”.

12 Véase, por ejemplo: Arturo ROCHA, Los valores que unen a México. Los valores propios de la mexicanidad. Una contribución a la experiencia de México con una insistencia particular en las virtudes morales. Primera Parte Lib. II: Del México Colonial (1ª. parte 15211650), México: Fundación México Unido/ Nacional Monte de Piedad/ Fundación GBM/ Lagg’s, 2010, cap. VIII, p. 462 nota 3035; cfr. ROCHA, Virtud de México. El valor de la tradición, México: Ed. Miguel Ángel Porrúa/ Fundación México Unido, 2006, cap. 6, pp. 47-51.

Mtro. Jorge Arredondo Sevilla†

ABSTRACT: Juan Diego became the first American Indigenous Catholic to be canonized, recognized as being in heaven and worthy of veneration. This article will present the fabric of the canonization path of Juan Diego, a journey that intertwines the ideological and historical context of Mexican polity. This work aims to bring into a broader dialogue the reception and effects of the first Indigenous saint of the Americas with the contemporary layperson, especially now on the eve of the 500th Guadalupan apparition festivities. Reviewing the Canonization process permits a deeper understanding of Guadalupan studies and allows the Guadalupe scholar to delve into who Our Lady of Guadalupe chose as a messenger.

RESUMEN: Juan Diego se convirtió en el primer indígena en ser canonizado en las Américas. Este artículo presentará el entretejido del camino de canonización de Juan Diego, un viaje que entrelaza el contexto ideológico e histórico de la política mexicana y los pormenores de su existencia histórica. Este trabajo tiene como objetivo llevar a un diálogo más amplio la recepción y los efectos del primer santo indígena del continente con el laico contemporáneo, especialmente en vísperas del quinto centenario de las apariciones guadalupanas. La revisión del proceso de canonización permite una comprensión más profunda de los estudios guadalupanos e introduce al estudioso de Guadalupe ahondar acerca de la persona que Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe eligió como mensajero.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Juan Diego, Our Lady of Guadalupe, Canonization.

* El texto aquí publicado fue redactado a invitación expresa de la Dirección Académica del COLEG.

† Jorge Arredondo obtained his Undergraduate degree from Universidad Católica Lumen Gentium in Philosophy, his Master's in Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School and is currently doing a PhD in Theology at the University of Notre Dame.

“Of this historical error the proceeding grievances arise, as earlier stated, as if God was served in completing the documents, and accounts that I have need of in this matter and of decreeing his most glory in the canonization of this blessed Indian…”1 On August 29, 1739, Lorenzo Boturini addressed Alonso de Moreno in a letter and referred to him the yerro histórico, the historical error of Juan Diego not living a “chaste life” as was previously thought and thereby having descendants. One of his descendants was a nun who claimed to be his fifth granddaughter and sustained this lineage to be accepted into a convent for Indigenous nobility.

This news was made public on May 24, three months earlier in the Gazeta de México, which, according to Boturini hindered a possible canonization process, perhaps a plan in the Italian´s query. The same erudite, as the Positio refers, says that out of respect for the decree of His Holiness Urban VIII Juan Diego should not be referred to as venerable or blessed as it could affect his possible canonization; this is especially the case in 1739 when the Guadalupan Event was not recognized by the Holy See.2

There are scarce sources in this century probing Juan Diego´s holiness, but this is not the case in the nineteenth century. In 1862, Don Santiago Beguerisse, a Knighted French soldier, arrived in Mexico during the French invasion, a war that would lead to the founding of the Second Mexican Empire. Following the invasion, he remained in Mexico and eventually was incorporated into Mexican society. He later established a drugstore dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe. Decades later the devotee, á la Boturini, sent letters to the church hierarchy requesting the canonization of the neophyte, Juan Diego.3 Among the prelates

1 ARCHIVO HISTÓRICO DE LA BASÍLICA DE GUADALUPE, caja 334, exp. 79, f. 31r.

2 Mexicana canonizationis servi dei. Ioannis Didaci Cuauhtlatoatzin, viri laici (14741548): positio super fama sanctitatis, virtutibus et cultu ab immemorabili praestito, ex officio concinnata, Catholic Church. Congregatio pro Causis Sanctorum. Officium Historicum (Series) (Romae: publisher not identified, 1989), xiii, doc. XI.

3 Ramón SÁNCHEZ FLORES, Juan Diego, personalidad histórica de un pobre bienaventurado: estudios y documentos, 1a ed, NYDH monografías históricas, México: Noticias y Documentos Históricos, Comisión de Historia de la Federación de los Oratorios de San Felipe Neri, 1981, 100–101.

he did not have to convince of Juan Diego´s canonization much were Fortino Hipólito Vera and the Abad of the Basilica of Guadalupe, Plancarte Labastida.4

Canonization attempts would remain difficult to pursue due to Mexico´s political turmoil, especially considering liberal and conservative stints of power fighting over the rights of the Church. Despite this unrest, the figure of Juan Diego continued to be socially present. The Indigenous man was kept in the public ear even so flippantly during the Juarez regime with the short-lived hebdomadary “Juan Diego.”

From 1872 to 1874 the hebdomadary established itself with wit and humor offering social criticism against the liberal Mexican government. “A constitutionalist newspaper, a friend of the people and essentially spoiled, which must give a lot of war to Juárez and his troupe” was the subtitle used in many of its early issues. Sections were entitled “Flores” or flowers announcing presidential bids, retrieves, etc. Other official segments included “Apariciones” or apparitions to political figures and even the “Magnificat,” a shorter version of the latter that announced a piece of political news.

In the third issue on Sunday, July 28th , Juan Diego (or rather his editorial voice) introduces himself as a poor, well-mannered man, to the new president of Mexico, Sebastían Lerdo de Tejada; he says, “As you know, I am Indian, and according to some I supposedly personify the people, or I am the people themselves and I have been told my master has changed […Benito Juarez had died ten days prior] I have come to ask some little questions…” The editors speaking through Juan DiegoPeople would go on and ask the new president if he would feed him with “stick and bread” like the others and then asked him if he would govern capriciously or constitutionally. The warning of being a good regent resounded in the threat of Juan Diego wielding his ayate or cloak against him, day in and day out if his ways were crooked.5

4 Lauro LÓPEZ BELTRÁN, La historicidad de Juan Diego y su posible canonización, 1. ed, Obras guadalupanas de Lauro López Beltrán, México: Editorial Tradición, 1981, 14.

5 “Ayatazos”, Juan Diego, July 28, 1872. “HNDM-Publicación,” accessed July 26, 2024. https://www.hndm.unam.mx/consulta/publicacion/visualizar/558075be7d1e63c9fea1a312?pagina=558a34287d1ed64f16a10244.

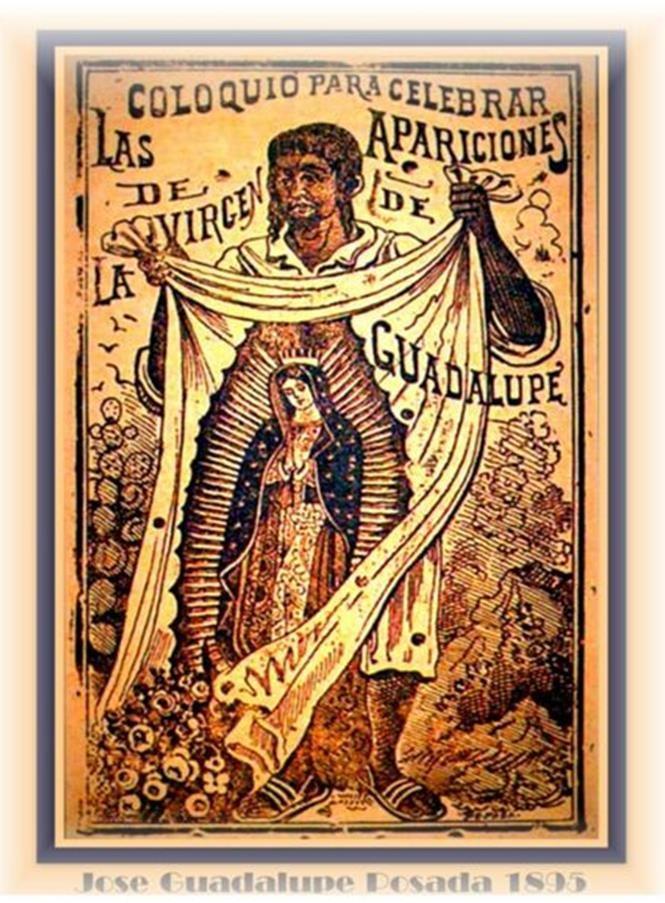

By the turn of the century Esteban Anticoli S.J. wrote his magnum opus, Historia de la aparición de la Sma. Virgen María de Guadalupe en México (1897), in it the transnational author cites Benedict XIV´s De Servorum Dei Beatificatione et de Beatorum Canonizatione to prove one of the Church´s criterium to discern whether an apparition is true. The pope in BK. III, ch.51, no. 3, says that apparitions are known to be supernatural by the test of the person who received the miracle; the modus by which the apparition was verified; and by its effects. Anticoli henceforth begins to prove Juan Diego´s holiness (person), how he was questioned by Zumárraga (modus), and the great effects of the apparitions.6 He compares Juan Diego to other saints and seers such as Saint Dominic who also received a revelation from the Virgin Mary.7 Anticoli would henceforth argue credence to Juan Diego to sustain the factuality of the Guadalupan apparitions, a trend followed throughout the next two centuries. The Jesuit scholar sustained this through the 1666 Juridical Proceedings, a set of testimonies recorded to obtain the Mass and Office for Our Lady of Guadalupe´s feast day, where mediated witnesses testified to his holiness.

Another attempt to canonize Juan Diego would be enunciated in 1904 by priest Benito Pardiñas, Conciliar Seminary of Guadalajara theology professor and priest of San Juan de los Lagos, in the Second Catholic Congress of Mexico and First Marian Congress held in Morelia, Michoacán. There he entreated the many prelates to beatify Juan Diego as this would glorify Our Lady of Guadalupe and add proof to her “cause.”8 The Mexican Revolution broke out and thereafter the Cristero War began;9 no real attempt was officially made to continue the canonization process of the holy neophyte for at least two decades.

6 Un Sacerdote de la Compania de Jesus, Historia de la aparicion de la Sma. Virgen Maria de Guadalupe en Mexico: desde el año de MDXXXI al de MDCCCXCV por un sacerdote de la compañia de Jesus. Con licencia de la Autoridad Eclesiastica. (México: Tip. y Lit. “La Europa” de Aguilar y Cía, 1897), 111s.

7 One may be referring to the same supernatural event concerning the act itself (apparition, hierophany), what she witnessed (vision), and what she conveys or is asked to express about it (prophecy or revelation).

8 Segundo congreso catolico de Mexico y primero mariano celebrado en Morelia del 4 al 12 de octubre de 1904 (Talleres Tip. de Agustin Martinez Mier, 1905), 113.

9 It is important to mention that on November 14, 1921, a government minion set off a bomb attempting to destroy the blessed Image. She miraculously survived.

This work will follow the path to holiness of Juan Diego. This goal excludes the plethora of references of his actual holiness which are present even before Miguel Sánchez so famously typified the neophyte to Moses in Imagen de la Virgen María (1648) or José López de Avilés´ Poeticum Viridarium (1669). This work is an exaltation of the seer using Classical literature. In it, for example, López de Aviles intertwines verses of Virgil´s Aeneid to voice Juan Diego´s first encounter with Our Lady of Guadalupe.10

During the twentieth century, Mexican society was presented as a true battleground for the people´s loyalty and creed; the Church and State carried out a “Cold War” after the Cristero War and Juan Diego´s canonization efforts were part of it. We will present this secularist struggle that truly concluded a decade before Juan Diego´s canonization.

In 1939, the year exiled Bishop José Jesús Manríquez was forced to leave his prelature, he wrote from San Antonio, Texas, a pastoral letter promoting the canonization of Juan Diego.11 Manríquez was one of the few prelates who supported the League and an avid denouncer of the peace treaty that Bishops Leopoldo Ruiz y Flores and Pascual Díaz y Barreto made with Plutarco Elías Calles and Portes Gil. A treaty that would lead to the opportunistic death of many of the Cristero generals once they laid down their arms. Manríquez wrote a sermon, and a subsequent publication entitled Quién fue Juan Diego, or Who Was Juan Diego? These sources talk about his virtues and how a new race was born after the apparitions. The devotional piece was completed in that same

Henceforth plans were made to protect her in a secure location, especially as war broke out between the Church and the State officially in August 1926.

10 Cf. Citlali LUNA QUINTANA, “La Virgen Heróica En El Poeticum Viridarium... de José López de Avilés,” Boletín Del Colegio de Estudios Guadalupanos 2, no. 3 (June 2022), 84.

11 In it he says how, more than a great lack of bibliographical sources related to the neophyte, the Mexican people have done little to find historical sources in all archives of the world (a fundraiser was necessary) or promote his canonization, something that would dignify the native race of Mexico (not promote natives to go back to their ancient ways) and it was racism that had caused this neglect. Brading refers more pointedly to the document (2002, 311) and Lauro López Beltrán publishes it in its entirety (1981, 21s).

year (October) after he resigned his bishopric (July); he would return to Mexico in 1944 when to promote Our Lady and Juan Diego until he died in 1951.12

As the social struggle evolved between Church and State after the Cristero War, an ideological question arose, what is the founding story of Mexico? The eagle devouring a snake on a prickly pear cactus, as the PRI most avidly infused, and thus the Revolution was a struggle for domestic autonomy? Or did Mexico perhaps begin as a Christian nation with the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe where a fusion of two cultures took place, creating a new nation that was reaffirmed in the canonization of Juan Diego? The Catholic Church did not cease to promote the canonization with great zeal, after the aforementioned wars, despite the political imbroglios of the twentieth century. This section will deal with the social quarrels between the Church and State and Our Lady of Guadalupe-Juan Diego´s role in this conflict.

The State and the Church engaged in ideological warfare in which the government presented a revolutionary history in which new traditions, feasts, and ideals were constituted, while the Church revived its devotions, especially that of Our Lady of Guadalupe to contrast and reaffirm Mexico´s Catholic identity. Vasconcelos created the SEP (Secretaria de Educación Pública, or Educational Bureau) during Obregon´s stint. This bureau intended to bring literacy to the most marginalized areas of Mexico while Vasconcelos’ elite agenda was promoted. When the Executive government was not officially at war with the Church, the teachers were sent out like missionaries preaching the glories of the Revolution, essentially promoting a real change that had surpassed that of fideism and superstition.

As was the case in the Porfirian Regime when scientific positivism was promulgated through books such Mexico: Su evolución social to promote a state identity, the SEP commissioned official history books that interpreted accounts to the benefit of the current regime. Among the most popular was Morales Jimenez´s Revolution publication. The State went as far as creating a National Institute for Studies of the Revolution to promote a steady line of hermeneutics.

12 José de Jesús MANRÍQUEZ Y ZARATE and Lauro LÓPEZ BELTRÁN, Quién fue Juan Diego, 1. ed, Colección Cincuentenario del movimiento actual pro canonización de Juan Diego, Iztacalco: Tradición, 1989, pp. 5–7.

To contrast the State´s educational agenda, the Catholic Church promoted intellectual representatives in the academy who fostered the birth of a nation with the history behind the Guadalupan Event, the sixteenth-century dedicated missionaries, and more recently heroic martyrs. In 1921, the Jesuit priest Mariano Cuevas wrote his magnum opus, Historia de la Iglesia en México, in which he recounts and addresses the Guadalupan story historically. In 1926, Primo Feliciano Velázquez translated and popularized the Nican Mopohua for the first time and this same year, despite the Cristero War beginning, the Basilica Chapter began to publish Tepeyac magazine;13 in 1931, for the 400th anniversary of the apparitions, he published an apologetic work, La Aparición de Santa María de Guadalupe.

We must also mention Mariano Cuevas’ Álbum histórico guadalupano IV centenario, 1930; Jesús García Gutiérrez published in 1931, Primer Siglo Guadalupano, Efemérides Guadalupanas and Juicio Crítico sobre la Carta de D. Joaquín García Icazbalceta. Apart from these publications, the Vatican granted plenary indulgences that year and the Mexican Church organized the Guadalupan National Congress for the 400th anniversary of the apparitions. In 1936, Pope Pius XI delivered an apostolic letter entitled: B. V. Maria sub titulo de Guadalupa Insularum Philippinarum Coelestis Patrona Declaratur. In 1938, Antonio de Pompa y Pompa published, Álbum del IV Centenario Guadalupano. Although there was much religious activity and “peace” had consolidated, by 1935, the Department of the Interior, under the Office of Political Information, was still reporting, inspecting, and closing certain Catholic schools, so peace was meager.14 The aggressions were such that, a decade after laying down their arms, the Mexican Academy of Our Lady of Guadalupe called for a “crusade of prayer” in the newly founded magazine Juan Diego (1939). This was done with the hope to

13 This publication should not be confounded with the newspaper Tepeyac which was part of the Center´s media communication outlets. This magazine was edited by Fr. José Cantú Corro and from our records ran until 1930. It ran sections on Guadalupan apologetics, Catholic book advertisements, stories about ecclesial like the one on page 22 of its fourth issue dealing with the imprisonment of bishop Manríquez y Zárate, cf. “El Tepeyac V.1 NO.4-10 1926, 22.,” HathiTrust, accessed August 2, 2024, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/txu.059173023892359?urlappend=%3Bseq=6.

14 Cf. “Resultado de Investigaciones”, Investigaciones Políticas y Sociales, Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico, caja 71, Exp. 12, f. 3.

save Mexico from persecution through the prayer of the Rosary, by the intercession of Our Lady of Guadalupe. 15,16 A decade after the closures of Catholic schools, for example, the Church continued to mobilize socially.

In 1946, Father Beltrán presented “Tres Iniciativas Guadalupanas” in which he summoned the Guadalupan devotion during the bicentennial of the first consecration of the Patronage that was made in the New Spain to the Virgin of Guadalupe, an oath, stirred up after she healed Mexico City of the pandemic of matlazahuatl. The priest then proposed to renew the patronage and enthrone the Image in every house and temple within a year.

After peace was made, the PRI´s strategy, consciously or not, was one of laissez-faire. In it, the state allowed the Church to operate and did not impede people from attending or generally living their faith. It seemed that repressing the religious consciousness of the people only kindled faith. The state rather proposed social alternatives that were geared at promoting the Revolution and creating a state ideology.

The “perfect dictatorship” created a “family” with common interest out of those who in life fought each other: Madero, Zapata, Villa, and Carranza were all allegedly seeking the same revolutionist ideals, but due to their idiosyncrasies were not able to solidify the great dream the PRI came to establish. To make sense of the Revolution, the winning faction spiritualized and unified an ideological history and interpreted it in a religious proselytist manner.

Among the mimesis identity stratagems the State promoted to contrast the heavy Catholic and Guadalupan culture, especially in the 1930s were national feast days that contrasted patron feasts and holydays. The 20 of November (athletic) parades began in 1930 to compete with pilgrimages and Catholic youth organizations; statues of national heroes (people whose lives are heroic examples of how to live

15 The magazine was founded by Fr. Lauro López Beltran after being inspired by Huejutla’s exiled bishop Manríquez whom he visited in San Antonio, Texas. The humble prelate fundraised towards this effort and father Beltrán continued his monthly enterprise for 27 years straight, cfr. Lauro LÓPEZ BELTRÁN, La historicidad, 39.

16 "Coupon" of Crusade of Prayer, n.d., Archivo Histórico of Biblióteca Héctor Rogel (Seminario Conciliar de México, SCM), Fondo García Gutiérrez, Sec. Guadalupanismo, Ser. Imp., Box, 301, No. Exp., 20, Fol.1.

and die for the glory of the nation) to outweigh statues and relics of saints; Bellas Artes (1932) would be a Mecca for non-religious art; the Álvaro Obregon Monument (1935) would make the last Revolution general a martyr assassinated by a Catholic fanatic. Finally, myths, legends, and traditions were divulgated through the radio during the Lord´s Day in La Hora Nacional (1937), a state-sponsored radio hour that every radio station in Mexico had to stream.

Furthermore, the state promoted murals that represented Zapata as a martyr, saint, and campesino warrior who died for the cause of the Revolution.

Diego Rivera used him as a model for many of his murals with those themes, especially those in the SEP building in Mexico City. Rivera used religious symbolism to sanctify historic characters. In 1931, Alfaro Siqueiros represented Zapata as a wearisome fighter and in 1934 Clemente Orozco painted him as a fighter, even extending his art to the US (Baker Library, Dartmouth University), whose fusil was used to support his tiresome weight as he contemplated external power forces that moved the Revolution. Many of these politics had Soviet, socialist influence.

The Catholic Church in response reiterated the notion of holiness to re-establish a sense of national heroism. Juan Diego was not the only Mexican role model. The Catholic Church memorialized the Cristero conflict within the tradition of martyrdom-persecution, uplifting their heroes to the status of saints. Stories were heard about Miguel Agustín Pro, a Jesuit priest who dressed up in different office customs to celebrate Mass in different homes throughout Mexico City. The police who were looking for him were not able to recognize him when he one day walked as a doctor, other times with a lawyer suit, etc. He was eventually executed and accused of bombing the car of a high-up politician, a charge that was not true.

Another set of Catholic heroes was a group of laymen and priests in Guadalajara commonly referred to as the “Martires Cristeros.” All were canonized during Pope Benedict XVI’s stint. A latecomer to this saint celebration is the famous José Sánchez del Río, otherwise known as

“Joselito.”17 It was mid-century that the official journey to Juan Diego´s canonization took form after social upheaval eased.

Lauro López Beltran founded the Centro de Estudios Guadalupanos or Center for Guadalupan Studies (Center from now on) on October 12, 1975, to promote the study of Our Lady of Guadalupe, being at the service of the Church as inaugurated by Cardinal Miguel Darío Miranda. The Center came to take the place of the Academia Mexicana de Santa María de Guadalupe or Mexican Academy of Our Lady of Guadalupe founded on October 12, 1920, during the commemoration of the Silver Jubilee of the Pontifical Coronation of Our Lady of Guadalupe.18

Among the Center´s most important tasks were the organization and subsequent publication of the papers of the conference Encuentro Nacional Guadalupano, or National Guadalupe Encounter19 not to be confused with the Guadalupan National Congress which celebrated the 400th anniversary of the apparitions. This Center actively engaged almost from the offset to carry out the mission entrusted to the extinct Academy regarding finding substantial evidence to present a case for the canonization of Venerable Juan Diego.

Lauro López Beltrán tells us that in 1940, Mons. Luis María Martinez, Archbishop of Mexico, “commissioned the survey [of Juan Diego sources] to Father Jesús García Gutierrez, Guadalupan historian and member of the Mexican Academy of Our Lady of Guadalupe, to the Rev. Fr. José Bravo Ugarte, S.J., our great historian and to the then

17 A boy who joined the cause even when he recognized that he was lowly but helped in what he could. Memorable is the fact that he gave up his horse so a general could escape when the Federals were about to capture the Cristero general. Joselito was captured and was obliged to renounce his faith and would therefore be set free. He opposed becoming an apostate. The soles of his feet were flayed, and he was forced to walk thusly to the site of his grave. This fourteen-year-old boy was then forced to dig his own grave. Another chance was given to him to denounce his faith. He did not and was shot crying, “Viva Cristo Rey”. Other stories tell of a Catholic boy, liberated by the federal army for being too young to be shot, when he returned to his house his mother told him, “you were not worthy of martyrdom my boy”.

18 LÓPEZ BELTRÁN, La historicidad de Juan Diego y su posible canonización, 194.

19 SÁNCHEZ FLORES, Juan Diego, personalidad histórica de un pobre bienaventurado, 102.

director of the National Library, D. Juan B. Iguíniz […] but the said study was very schematic and poorly presented and lacking thorough much-needed research then Rome kindly did not reject the introduction to the Cause, but only answered that as long as the submission was not properly documented, the petitioners should abstain from their purpose.”20

It was July 1940, when the first petition to Rome began through the historical research commissioned by the Archbishop of Mexico. As seen above, the process did not proceed. Three decades later, a second commission was formed to resubmit the historical sources and seek the beatification of Juan Diego.21 This same year an overlooked work in Guadalupan studies was released: Epigrafia iconografía y literatura popular de Juan Diego by Higinio Vázquez Santa Ana; the book enlists multiple plates, engravings, sculptures, Guadalupan altars, and paintings from around the globe and expanding at least three centuries all containing Juan Diego as its subject or as part of the theme.22

In that same decade, many miracle intercession stories and other pious prayers were dedicated to the neophyte in Juan Diego magazine, yet a separate publication is worth mentioning for its high prose and poetic tone. Ángel María Garibay, the Indigenous Scholar from UNAM and the most prominent pioneer in native studies in the past century, wrote a Mortuary Eulogy in 1949 about fray Juan de Zumárraga and Juan Diego as they both were taken up to heaven the same year. Father Garibay mentioned the scarce sources available in Nahuatl, yet the extant ones, like the Nican Motecpana, he renders as old as 1545. The piece is beautiful, theological, and profound.23

Before much noise was made regarding Juan Diego´s Cause, American priest Charles J. Wahlig wrote Past, Present and Future of Juan Diego: Heroic Figure of the Natural and the Supernatural in 1972 recounting the Nahua pre-encounter environment and the subsequent conversion

20 LÓPEZ BELTRÁN, La historicidad de Juan Diego y su posible canonización, p. 45.

21 The status of “Servant of God” and “Venerable” were assumed in his immemorial holiness fame.

22 Higinio VÁZQUEZ SANTA ANA, Epigrafia iconografia y literatura popular de Juan Diego, Ed. Conmemorativa, Mexico: Musco Juan Diego, 1940.

23 Ángel MaríaGARIBAY K., Fray Juan de Zumárraga y Juan Diego: elogio fúnebre, México: Ábside, 1949, p. 19.

of millions due to Our Lady of Guadalupe. The historical sources Father Wahlig uses are not very extensive, yet he opens the subject of Juan Diego in the English language.24

The ball began to officially roll in 1974, the year when both Lauro López Beltran began to gather scholars for the Center´s foundation, and the diocese of Mexico City sought to begin the canonization process to commemorate the fifth centenary of the birth of Juan Diego.25

We know that three years later Juan Diego was more present in the Catholic academic world.

Ramón Sánchez Flores who was later named historical expert in the Beautification Commission due to his sixteenth and seventeenth-century Mexican historiography expertise, and the then Archbishop of Mexico Ernesto Corripio Ahumada heard Lauro López Beltrán´s lecture about the historicity of Juan Diego on December 1977 in the Segundo Encuentro Nacional Guadalupano, or the Second National Guadalupe Encounter, a conference organized by the Center. 26,27

Right then and there the Archbishop of Mexico vouched to support the beatification of the neophyte as the crowd cheered on. In January 1978, the prelate sent Mons. Vicente Torres Bolaños to attend the weekly academic reunions of the Center held in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe. There, the vicar presented guidelines to aid in the submission and recollection of historical records about Juan Diego. All

24 Charles J. WAHLIG, Past, Present and Future of Juan Diego : Herioc Figure of the Natural and the Supernatural, New York: Franciscan Marytown Press, 1972. To see the literature in English on Our Lady of Guadalupe see Gloria Grajales and Ernest J. Burrus, Guadalupan Bibliography (1531-1984), nos, 597, 703, 722, 754, 757, 766, 802, 807, 816, 824, 840, 844, 845, 851, 852, 855, 863, 875.

25 Norberto RIVERA CARRERA, Juan Diego: el águila que habla, Plaza y Janés, 2002, p. 16. Also se Positio, xiv.

26 It was this same priest who, for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the coronation of the Virgin had published in 1973: “Albúm del LXXV aniversario de la coronación guadalupana.”

27 The talk was published beforehand, in November of 1977. It was part of López Beltrán´s book, La historicidad de Juan Diego a book that would be edited and augmented in 1981 with the title La historicidad de Juan Diego y su posible canonización.

that year the Center worked tirelessly on all the preliminary historic sources.28

Sparked by the call of the entire Mexican episcopate who welcomed John Paul II´s first apostolic visit in 1979, the Archbishop of Mexico decided to listen to the people's voice and officially supported the internal diocesan beatification query. This, according to Ramón Sánchez Flores occurred on January 31, 1980, other sources have marked nuances.29 Mons. Enrique Roberto Salazar was named Postulator of the Cause;30 the Historic Commission was later named and it consisted of Luis Medina Ascencio, S.J., charged with Juan Diego’s bibliography as well as the evaluation of the presented sources; Manuel Rangel Camacho, commissioned to find manuscripts and sources that attested the neophyte´s fame of holiness; and Ramón Sánchez Flores who complemented the effort seeking in historical archives testimonies related to the seer. That same year the Commission was fruitful in spreading their advances through the Center´s media outlets.31

28 Although not part of the Center, Fidel de Jesús Chauvet who promoted the Centro de Estudios Bernardino de Sahagún, published a supporting piece this same year, El culto Guadalupano del Tepeyac. Sus Orígenes y sus Críticos en el Siglo XVI, México: Centro de Estudios Bernardino de Sahagún, 1978.

29 Citing “Carta S. Congregación para la Causa de los Santos al cardenal Ernesto Corripio Ahumada el 8 de junio de 1982”, prot. N. 1408-3/1982. Fidel González tells us that, “Se dieron entonces los primeros pasos y el 15 de junio de 1981, la Conferencia episcopal mexicana pidió formalmente su canonización durante su décima Asamblea. La Congregación para la Causa de los Santos informó al entonces arzobispo de México, el Cardenal Ernesto Corripio Ahumada, de los pasos necesarios en tal sentido el 8 de junio de 1982” Fidel González, “JUAN DIEGO CUAUHTLATOATZIN; Procesos de Beatificación y de Canonización - Dicionário de História Cultural de La Iglesía En América Latina,” accessed July 31, 2024, https://www.dhial.org/diccionario/index.php?title=JUAN_DIEGO_CUAUHTLATOATZIN;_Procesos_de_beatificaci%C3%B3n_y_de_canonizaci%C3%B3n#cite_ref-7.

30 Enrique Roberto Salazar was then President of the Center and was widely known as an avid promoter of the Adoración Nocturna Mexicana, or the Mexican Nocturnal Adoration; Salazar says he was named postulator in October 1979 and the historic commission would pledge the following year Cfr. Lauro LÓPEZ BELTRÁN, La historicidad, pp. 144, 189. See also Positio, xiv.

31 The newspaper Tepeyac which was published biweekly coupled with the quarterly magazine Histórica were produced by the Center which had also acquire its own headquarters. Cf. Lauro López, Historicidad, 145. The headquarters might have been Jade 89, Z.P. 14 (GAM), Federal District of Mexico, noy Mexico City from López Beltrán´s

They began circulating their findings. In 1981, Ramón Sánchez Flores, for example, published Juan Diego, personalidad histórica de un pobre bienaventurado, inspired by Mexico City´s Cardenal Ernesto Corripio Ahumada summoning of prominent historians for documental sources.32 This same year, 1981, the Mexican Conference of Catholic Bishops sent the Pope a letter petitioning the Servant of God´s beatification. Rome responded by correcting and straightening up the diocesan juridical protocol misdeeds.33 The next year Rome asked the Archdiocese of Mexico for a postulator to reside in Rome.

Ernesto de la Torre Villar and Ramiro Navarro de Anda published Testimonios históricos guadalupanos (1982) a major collection of Guadalupan sources, which was a notorious work that attested there was scholarship on the subject. This same year on June 8, Rome asked for a more exhaustive proceeding, and a new Commission was named, one that would conclude its query in April 1983.34 In 1983, Divinus perfectionis magister was enunciated, an apostolic constitution in which Pope John Paul II facilitated the process of canonization by managing it with local prelates with the assistance of the Sacred Congregation for the Causes of Saints. An extensive citation of key points in the beatification process as annotated by the last representative of Rome, Fidel González will summarize the rest of the decades´ advancements:

His Eminence [Ernesto Corripio Ahumada] then appointed Father Antionio [sic] Cairoli, O.F.M. as Roman postulator on January 19, 1984. On Saturday,

comment on receiving letters about potential miracle intercessions, Cfr Lauro López, Historicidad, p. 192.

32 SÁNCHEZ FLORES, Juan Diego, personalidad histórica de un pobre bienaventurado, 103. We know from Eduardo Chávez that also in 1982 and 1989 the Cardenal gathered with different historians for the same purpose. Eduardo CHÁVEZ SÁNCHEZ, La verdad de Guadalupe, México: Instituto Superior de Estudios Guadalupanos, 2012, p. 27.

33 “La Congregación de las Causas de los Santos con fecha 8 de junio de 1982, informó al Cardenal Ernesto Corripio Ahumada que completara exhaustivamente la información de la Causa, y que se hiciera el nombramiento de un postulador residente en Roma. El problema hasta ese momento era que se estaban haciendo las cosas sin la formalidad jurídica de un proceso ordinario diocesano, pues desde México se mandaban los documentos directamente a la Congregación de las Causas de los Santos.” Fidel GONZÁLEZ, “JUAN DIEGO CUAUHTLATOATZIN; Procesos de Beatificación y de Canonización - Dicionário de História Cultural de La Iglesía En América Latina.” Also see Positio, xiv.

34 Cfr. Positio, xiv.

February 11, 1984, the [Beatification] Tribunal was legally integrated, and the opening session of the case was held. There was a total of 98 sessions in which the Tribunal reviewed the documents presented to it by Professor Joel Romero Salinas, Member of the National Academy of History and Geography of Mexico, who was appointed Expert in History and Archival for the Case in question. On March 23, 1986, the closing session of the Cause in its diocesan phase was held and sent to Rome. The opening session was held in Rome on April 7, 1986, and Cardinal Ernesto Corripio asked Fr. José Luis Guerrero, who in Rome worked as a collaborator of the Rapporteur of the Cause, Msgr. Giovanni Papa, for the explanation of the aspects of the indigenous Nahuatl culture and the meaning of the Guadalupan theological message.35

At this stage, the Beatification team became more extensive including several consultants. The culmination of this stage was delivered in the form of the Positio in 1989 for the beatification of the venerable neophyte the following year.36 Shortly after a miracle from Juan Diego´s intercession was discerned from several,37 and it was sent to Rome. The canonization seemed prominent, yet the turn of the decade had a set of prominent scholars who disagreed with the historical claims made about Juan Diego, they would bring about a whole new chapter in Juan Diego´s path to the altar.

35 GONZÁLEZ FERNÁNDEZ, “JUAN DIEGO CUAUHTLATOATZIN; Procesos de Beatificación y de Canonización - Dicionário de História Cultural de La Iglesía En América Latina.” Also Positio, xv, Doc. XIV.

36 Synthesis of the life and heroic virtues of the Servant of God (stage one of the canonization process), this is done so that the candidate can become Venerable (stage two). When the Servant of God has an unmemorable reputation for holiness, the miracle at this stage is not necessary. This was the case for Juan Diego.

37 Several miracles had already been attributed to the Indigenous man, as published by López Beltrán’s “Juan Diego” magazine; he recounts notable ones in “Milagros que se le atribuyen”, La historicidad, p. 77.

All the apologists, without excepting a single one, have fallen into an inexplicable mistake in so many men of talent, and that has been to constantly confuse the antiquity of the cult with the truth of the Apparition and miraculous painting on Juan Diego´s cloak. They have labored to prove the first (which no one denies, since it consists of irrefragable documents), insisting that the second was thereby proved, as if there were the slightest connection between the two. Joaquín García Icazbalceta, “Letter to bishop Pelagio Antonio Labastida”, No. 21.

At all stages, the Historic Commission had to refute difficult questions regarding Juan Diego´s holiness but then, after the beatification in 1990, his existence was seriously questioned. Apologetic responses were not new to the Guadalupan subject, ever since the eighteenth century when Juan Bautista Muñoz coupled with Teresa de Mier´s correspondence to him and the doubling down of the so-called “negative argument” by Joaquín García Icazbalceta and his peers “apparitionist” and “anti-apparitionist” literature flooded academia, and the “negative argument” thesis began to be restructured and augmented.

Icazbalceta accounted for the 1556 Proceedings, Suárez de Peralta´s Noticias, and the Juridical Proceedings of 1666 establishing a thesis that would be repeated through numerous authors in the following century reaching Rome in abundant letters through contemporary authors:

What is questioned is not whether the Virgin appeared to someone under the figure of the already existing image of Guadalupe; but if she appeared to Juan Diego in 1531 with the circumstances that are related, and in the end, she was imprinted on his tilma: that is, if the image we have is of heavenly origin. “Letter,” No. 47. Emphasis mine.

Art Historian Francisco de la Maza was one of the first authors to rework this precedent while launching an Indigenous substrate to it: “Apices and atoms are the popular Indigenous and mestizo legends first and then criollos, of the miracle of Tepeyac; […] Miguel Sánchez hears the tradition and writes it in its initial simplicity.”38 This was a move Teresa de Mier had surmised yet did not fully develop. Two decades later, Jacques Lafaye admits this essential claim in Quetzalcóatl y

38 Francisco de la MAZA, El guadalupanismo mexicano, México y lo mexicano 17, Mexico: Porrua y Obregón, 1953, p. 43.

Guadalupe (1974)39 and like De la Maza, excuses the extant sources that deal with an “apparition” clearly showing how all sixteenth-century sources deal with a miraculous advocation rather than one that appeared. 40

Jaques Lafaye considers that what was written in the seventeenth century has pre-Columbian bases: “The couple Quetzalcoatl-Tonantzin appears to have been one of the avatars of the universal dual principle, Ometeotl, in the Aztec theogony. However, only the late metamorphoses of the old Indian beliefs in the Creole thought of colonial Mexico interest us here.”41 In this regard, it is paramount to consider that modern scholarship considers that this dual god could have been a postColombian reworking.42 Additionally, we must note that Lafaye in a later writing attests the Nican Mopohua was written by Antonio Valeriano as a compilation of traditions.43

The crux of the matter lies in the configuration of the apparitionist history, i.e., whether the Nican Mopohua was composed in the sixteenth century or seventeenth century; it all boils down to whether Sánchez-Lasso wrote down a tradition that developed gradually or whether there already was a relación, a hidden manuscript from where

39 “Se dan todas las condiciones para suponer que el fervor guadalupanista, tanto de los indios (que sin duda veían a la vieja Toci bajo los rasgos de la Virgen María) como de los criollos deseosos de tener su propia patrona ligada al suelo de su nueva patria, aumentó después de 1556” (Jacques LAFAYE, Quetzalcóatl y Guadalupe: la formación de la conciencia nacional en México : abismo de conceptos: identidad, nación, mexicano, trans. Ida Vitale and Fulgencio López Vidarte, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2015, p. 264).

40 MAZA, El guadalupanismo mexicano, pp. 19–20; Jacques Lafaye, Quetzalco?, pp. 264s.

41 Jacques LAFAYE, Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, 1531-1813, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1987, 2, https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/Q/bo27778696.html.

42 Richard HALY, “Bare Bones: Rethinking Mesoamerican Divinity,” History of Religions 31, no. 3 (1992): 269–304, https://doi.org/10.1086/463285.

43 Jacques LAFAYE, “Cuestionada Historicidad de Juan Diego” in Lourdes Celina VÁZQUEZ, Juan Diego ORTIZ ACOSTA, and Luis Rodolfo MORÁN QUIROZ, El Santo Juan Diego: historia y contexto de una canonización polémica, 1. ed., Guadalajara, Jalisco, México: Universidad de Guadalajara, 2006. He additionally claims that the Guadalupan story is a circumstantial invention of the environment, as others have been, and that Juan Diego was mythologized into a saint by Francisco de Florencia, just as Cabeza de Vaca was by the Jesuit priest Charlevoix in the eighteenth century.

they were based off. No author denies that there is Mexican Guadalupan evidence before 1648 as references abound.

The great debate lies in the date of composition of the relación, as Poole addresses in his bibliographical review of Brading’s book, “The author makes a fundamental error in not making a clear distinction between Guadalupe before Sánchez’s book and Guadalupe after that. Though the shrine, image, and devotion existed from the mid-sixteenth century, it was not until 1648 that the story of Juan Diego and the apparitions became associated with them.”44

The whole matter lies in the supposition that the Nican Mopohua is from the sixteenth century. In that case, all the Guadalupan references are read in the light of the apparitions to Juan Diego. If the Nican Mopohua is from the following century, then the Guadalupan Event developed not only with deferred elements (Image, history-tradition, devotion, hermitage), but the Image becomes “miraculous” by the Christian conversions themselves, not as the source of them. If this is the case, Juan Diego´s existence comes into direct conflict with history, as was contended in the canonization process.45

In 1981, Ernest Burrus published “The Oldest Copy of the Nican Mopohua”, showing that the famous section of Lasso de la Vega´s original publication, “Nican Mopohua”, in the Huey Tlamahuiçoltica was indeed not a seventeenth-century product. Two copies were found in the Lenox collection in the NYPL while seeking the original Mariano Cuevas said existed in a Washington D.C. archive. Although this could seem like a clear validation of sixteenth-century antiquity, more contemporary authors would assert that Lasso de la Vega was still the author of the famous Guadalupe apparition story.46 Yet at the time academia emphasized the weight of the Nican Mopohua as an account

44 Stafford POOLE, “Mexican Phoenix. Our Lady of Guadalupe: Image and Tradition, 1531-2000,” The Catholic Historical Review 87, no. 4 (2001): 773, https://doi.org/10.1353/cat.2001.0181.

45 Stafford POOLE, “History versus Juan Diego,” The Americas (Washington. 1944) 62, no. 1 (2005): 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1353/tam.2005.0133.

46 Cfr. Luis LASSO DE LA VEGA et al., The Story of Guadalupe: Luis Laso de La Vega’s Huei Tlamahuiçoltica of 1649, Stanford, Calif.; Los Angeles: Stanford University Press; UCLA Latin American Center Publications, University of California, Los Angeles, 1998.

that dated around the mid-sixteenth century. Did this mean, however, that Juan Diego existed?

While Lafaye offered a religious and sociological perspective to the Guadalupe Event, Mauro Rodríguez in his Guadalupe, historia o símbolo? (1980) offered a psychology of religion response to the Guadalupe phenomena which extended from an absent father-god and a present mother-goddess projected in Tonantzin Guadalupe to subtracting the anthropological value behind the apparition story. The Tower of Babel did not literally, or historically mean people were divided into languages in Babylon, but the story means pride separates humanity, Guadalupe, likewise, creates unity among peoples yet it is not a true historical account. Other sciences, like the historical one, would leave their mark as a greater impediment to the Cause.

Historian Edmundo O’Gorman´s Destierro de Sombras (1986) asserts that the Guadalupan tradition was born in the Nican Mopohua yet it does not have historical credibility as Antonio Valeriano wrote (in 1556 before the Bustamante-Montúfar conflict) this story for natives, in Nahuatl, to attest they are divinely favored by God. Valeriano created a story behind the Guadalupe image that some natives believed “appeared” in 1555-1556 (as an image recently placed in the Tepeyac hermitage); the erudite native sacralized the image with a written account saying it appeared to one of their own, Juan Diego in a not-so-remote past, 1531. Additionally, the Nican Mopohua Christianized and distinguished itself from any “idolatrous” remanent from the Tepeyac.47