The role of preservation within the climate of capitalistic feudalism

The prime aim of this paper is to discern the role of preservation within the context of “wired revolutionaries”1, such as Facebook and Google, deploying their economic substrate in the area of King’s Cross, London from the perspective of a pre-existing context of urban/architectural and sociopolitical leftistanarchist heritage. What was thoroughly crafted through ideological component within welfare states in the circles of theoreticians (primary leftist ones) in social, political and economic development during second half of the XX century, majorly countering the idea of capitalist venture, still seems to spark lively debate. Moreover, as architects, we are also facing the question of our own voice within this neoliberal concept and in the words of Rem Koolhaas “are living in an incredibly exciting and slightly absurd moment, namely that preservation is overtaking us”2. Consequently, using the highly contested space of King’s Cross, as a laboratory of socio-political and architectural shifts, in trying to identify what kind of stratification emerged as a direct product of the corporate development within this area, which is the role of architect as a conservator or “starchitect”3 in this context and how does it reflect in physical world, will allow us to reexamine this issue on a much wider scale. In addition, the paper will interrogate OMA’s 2006 project for the Zeche Zollverein (Essen, Germany, 1920s–30s) as a positive practice in the context of preserving the historical character of the site, through which we can reflect on conservation as a potential platform for voices of otherness, within abovementioned fragile environment, to be properly heard. Finally, the question that emerges is if the voices of “those on the receiving end of techno-feudal exploitation and mind-numbing inequality”4 consider preservation as a radical act, how far the echo is bound to reach?

Keywords: conservation, architectural heritage, King’s Cross, Facebook, Google, capitalist, stratification, otherness.

Author: MSc Danilo Bulatovic; affiliation: Preservation of arch. heritage; title of proposal: The role of preservation within the climate of capitalistic feudalism; address: dan.bulatovic@gmail.com; type of proposal: Paper presentation.

BIOGRAPHY

My name is Bulatović Danilo and I was born on 22. X 1996. in Podgorica, Montenegro. In 2015, I enrolled in the Faculty of Architecture in Podgorica, where I obtained Bachelor diploma in 2018. After finishing Bachelor studies, I enrolled in specialization at the same faculty for the duration of 1 academic year. As the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Italy scholar I continued with two year master studies at the Milan Polytechnic University in Architectural design and History, graduating with a maximum score and distinction. In 2021 I was awarded Chevening Scholarship by the UK Foreign Office to pursue one year master degree studies in MA Architecture (History and Theory) at the University of Westminster in London.

I participated in numerous non-governmental initiatives and exhibitions that took place both in Montenegro and internationally. I would point out the exhibition that took place at Politecnico di Bari in 2018 and Polish Academy of Science and Art in 2019, representing University of Montenegro. My student works were published in numerous university’s publications among which most significant in “Public Spaces of Cities in Montenegro”, “100 Jahre Bauhaus”. I also participated in numerous workshops such as Dani Arhitekture, FLUID and MEDS (Italian team).

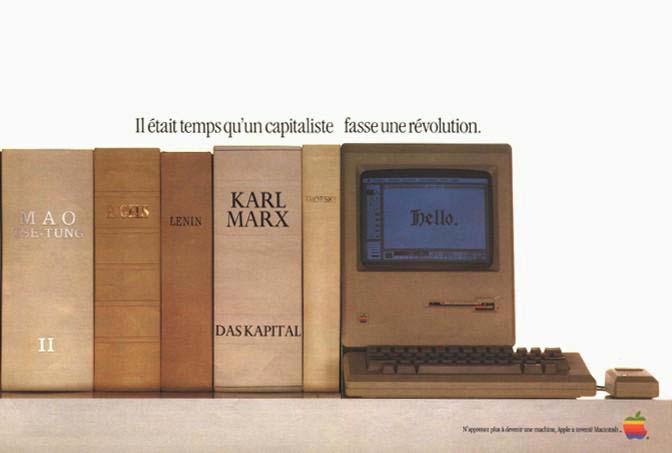

It was during one of the numerous protests, within turbulent Vietnam War era, in San Francisco Bay Area in the early seventies that participants stood up with their computers in hands as symbols towards the idea of stopping the war atrocities and retrieving back democracy through this new revolutionary gadget. It was in fact the product of the third industrial revolution where electronic systems and informational technology began pervading all sectors of human life. Ten years later, it was an ideal setting for the “wired revolutionaries” such as Apple and Google to put forward their strategic, almost saintlike, role in these challenging times described by Apple’s cunning use of Karl Marx’s image under the slogan: “It was about time a capitalist started a revolution!”5. The role of architecture, on the other side, proved to be, and still seems to be, yet another instrument in achieving this overall goal where it prefigures a “definitive role in naturalizing these effects and making them socially and culturally acceptable”6. Moreover, as the fourth industrial revolution paves its way, digital capitalist frontrunners, such as Facebook’s Metaverse, are establishing their parallel realities where architecture can be deemed as “useless object for capitalist development, and not even its "utopian" ideological weapon”7

It is exactly here that the radical rethinking of the role of architects and urban planners in today’s rapidly changing socio-political climate of the world can be interrogated via conservational strategies as a meaningful “instrument of planning which allows any society to modulate the rate of change”8. It is this component of our work which offers new possibilities in connecting our past and future through sensitive approach towards ethos of local environments where conservation is not perceived as a dogmatic but very fruitful and proactive methodology in shaping the world around us. This ethos is not solely embedded in the physical appearances of the architectural artefacts the waves of humanity has left behind, but more particularly within the social, cultural and political layers buildings communicate through their material form, emanating the voices of otherness.

Such paradoxically transformative role which conservation could potentially bring with itself can best be described through interpretation of potentials that exist in huge metropolitan environments such as London, where the arising issue of cancel culture emerges as a direct influence of capitalistic development. One of the numerous vivid examples of such contention is currently taking place in King’s Cross neighborhood where the economic substrate of large corporations such as Google, Universal Music, Facebook and YouTube reveal most critical results underpinning abovementioned stance. In fact, it’s a space infected with highly appropriated concept of frustrating design schism which leaves no place for irregularity, spontaneity or mistake, but, instead, offers top down solutions of clean and rational environments devoid of any genuine identity. It stands in sharp contrast with the leftist-anarchist heritage crafted by philosophers such as William Godwin who lived in nearby Somers Town along with the sociology of working classes rooted into the remnants of Coal Drops Yard and Terminal buildings at the backstage, where some of them are converted and reshaped for new capitalist-centered activities and detached of their illusio9

Although Rem Koolhaas’s famous pronouncement of death of stararchitecture and the overtaking pace of preservation surprised the audience at Columbia University in 2004, it might prove as efficient in describing today’s anachronism of built environment offered by corporate developers. Overall, in Jorge Otero-Pailos’s supplement to OMA’s Preservation Manifesto stating that the “Preservation’s mode of creativity is not based on the production of new forms but rather on t he installation of formless aesthetics to mediate between the viewer and the building ” 10 it would be useful to add that at this point the job of conservationist becomes particularly delicate, having to balanc e between integrity of the illusion of architecture and aligning it to accommodate other needs while embracing associative values of the building which then ensures it lives longer. In this way, architects and urban planners, contrary to the lack of conservation in the core architectural programs around the world, should strive to radically rethink and recalibrate the lenses through which we see the process of design in the future.

2.Neo-liberal revolution

There are some important prerogatives which fundamentally allowed advanced modes of capitalistic development to present itself in shape and form we see today. One of those can be traced back to the second half of XX century when Mario Tronti’s “The plan of the Capital”, which later strongly influenced thinking of Manfredo Tafuri, advocated that “a new cycle in which the organic link between capitalism and the postwar welfare state was the new form of capitalist domination”11. Namely, as suggested by Pier Vittorio Aureli, in 1963 Italy elected the government which was constituted by Socialist Party of Italy (PSI) and while being of left-center character it made the position of this welfare state slightly absurd in the wider context of Atlantic Pact union. Many leftist philosophers argued that it was a new form of capitalistic development in which the poles of these two opposing ideologies collided, emerging with the hybrid capitalism which, strangely enough, profited on leftist tendencies that had previously strongly opposed it. It should be noted that it was not until Margaret Thatcher (in 1979) and Ronald Reagan (in 1980) were elected in the United Kingdom and the United States that the neoliberal ideology fully penetrated economic development, crippling the benefits provided by the welfare state. Vivid manifestation of such a process is maybe best represented by “Thatcher infamously breaking the coal miner’s union and Reagan firing the air-traffic controllers who refused to return to work”12 referring to strikes launched by the National Union of Mineworkers in 1984 and Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization in 1981. The era of subjugated state as an instrument of neo-liberal policy was born.

Soon after, the US and the UK went through the same process of ideological leverage when Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, nominally belonging to the left wing, inherited and heralded the patrimony of Thatcherism and Reaganomics absurdly pursuing right-wing economic policies at an unprecedented level. In this sense, the principal goals and ideas that were recognized within the political spectrum to belong to the labors turned out against them in a paradoxical appropriation of ideology whose effect we can experience even today, but in an advanced and sophisticated forms. It was and still is a situation where according to Slavoj

1.“It was about time a capitalist started a revolution!”

Zizek “The left is caught in a post-political situation because it has conceded to the right on the terrain of the economy: it has surrendered the state to neoliberal interests”13 or in other words “capitalism is more revolutionary than the left has ever been”14. Consequently, corporate companies such as Google and Facebook can be deemed as proactive agents in an overall image of alleged process of participatory democratization which essentially secures strong foundations for what is today called “communicative capitalism”15. It is a political order in which many believe that we are fundamentally contributing to a certain process while, at the same time, being uselessly (most usually) braided in a net of wider spectrum of informational flow, channeled and directed from the Silicon Valley. More precisely we are living the reality where “Communicative capitalism thrives on the fetishistic denial of democracy's failure, its inability to secure justice, equity, or solidarity even as it enables millions to access information and make their opinions known”16. It is in this situation that we can say that the role of intellectual (thus architect) today is not anymore guided by the idea of freedom of speech, which predominantly marked the XX century, but by the notion of decolonization of intellectual thought, particularly within the realm of design practice.

2.1 From feuds to commons, and back again

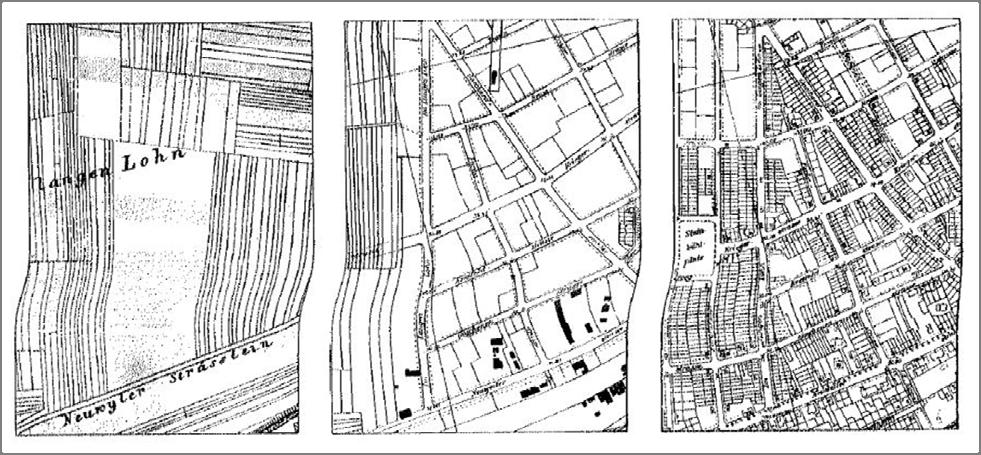

Another crucially important component of capitalistic form of domination is certainly the process of privatization. In his book “Architecture of the City” Aldo Rossi emphasized and casted light on the importance of expropriation process in the creation of the image of a city. Evoking the examples of Haussmann’s and Napoleon’s endeavors in changing the outfits of Paris and Milan, he goes on to claim the necessity of expropriation as an important process in a development of a city. However, it is also stated that “the communal lands that should have been maintained as collective property and the great property holdings of the nobility and clergy that should have been confiscated and held by the communities rather than subdivided among private owners—thereby jeopardizing the rational development of cities (and countryside)”17. Overall, the indispensable prerogative of capitalist-bourgeois economy was in its infancy. French Revolution accelerated this process in which feudalism was widely disregarded as a land ownership policy in favor of competitive land economy which will mark the centuries ahead. Although the first half of XX century marked the implementation of revolutionary ideals postulated by Karl Marx in a welfare countries where common good was highly advocated, it turned out, soon after, that the process is shifting back again towards promulgation of capitalistic system with a private ownership being sacred cornerstone of such economic order. However, this time, it was a hybrid form which embodied principles of what could be called “techno feudalism”18. In this sense, we have had a “set of policy assumptions favoring corporations, as inseparable from globalization and imperialism, as a "project for the restoration of class power," as a specific form of governmentality, and as a new form of the state”19. In this old/new differentiation of class power, the land as a constant currency has become highly exploited while its value skyrocketed underpinning fundamental principles of market economy.

2.Land subdivision (from left to right): agriculture (1850), building purposes (1920), building plots (1940).

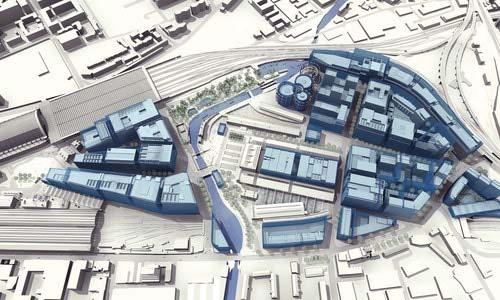

3.Waves of regeneration at King’s Cross

The application for King’s Cross redevelopment program was approved in 2006 as the outline planning permission was granted to Allies and Morrison, Porphyrios Associates and Townshend Landscape Architects. Today, the “regeneration” has taken its shape and according to some it is “The perfect mix of grittiness and shininess, simultaneously a symbol of London's industrial and engineering past and the creative present”20

3.King’s Cross redevelopment program 2006 by Allies and Morrison.

However, it is abovementioned amalgamated socio-political panorama we should have in mind when approaching development of King’s Cross area in London. Namely, what preceded the development plan was a disheveled socio-economic and political relief, which made a strong footprint within the character of local people and the space around them. This process evolved in several phases, which go back to the beginning of XIX century when this area served as a transportational hub for goods that came from the north of the country. Consequently, along with its economic exploatation which showed first signs of Victorian capitalism, it also instigated the birth of leftist political thought crafted by philosophers such as William Godwin (1756-1836). Being, himself, a resident of Somers Town (just next to the St. Pancreas Station) he, in a way, foresaw the consequences of neo-liberal concept, claiming that “human depravity originates in the vices of political constitution”21 and, instead, in line with Edmund Burke’s “Vindication of Natural Society” advocated anarchist vision of state. King’s Cross, however, continued to grow as one of economic melting-points in Victorian London. Moving to the second crucial stage of the development, in the interregnum of the two world wars, the area was subjected to the “House Improvement Society’s slum clearance and house-building program”22 which marked quite significant shift in the identity of the place. Namely, as originally built from poor materials in 1830s, residential objects showed their inefficacy in providing safe and clean environment for the people, primarily working class, to live there. Although, it was primarily envisioned for the households to be renovated, the Society decided to demolish and rebuild the objects. In a sense, it was a first major “regeneration” process which at first sight might have seemed pretty rational, but on the other hand raised more subtle issues. In words of Adrian Forty “The use of architecture and design in hygiene reform were not simply middle-class benevolence, but rather a means of social

control, and an attempt to ensure the health and longevity of a productive proletariat”23. Strangely enough, it is something that will resound as a metaphor for future development of this site, being equally important to this day. As the railway trading industry declined in the second half of the XX century, the area plunged to disrepair and negligence laying down the avenue for new waves of capitalism to overshadow the past. As mentioned before, Thatcherism and Reaganomics brought forceful decline of workers’ unions across the country, while substantially contributing to the process of rapid privatization. Consequently, British Rail was given into private hands while the site served as a venue for different architects to practice the incarcerated policy of sophisticated design solutions with an ambivalent top down effect. One of those examples can be attributed to Norman Foster’s “scheme (which) was dominated by office space (700,000 m2)”24 for the King’s Cross in 1993. However, it was not without social unrest, deeply rooted into the identity of this place that those proposals were imposed.

Namely, according to Ben Campkin “academics, activists and community members responded to this threat of King’s Cross…. and produced their own alternative vision, Towards a Peoples’ Plan (1990)”25. In fact it was the character of the place described through “Mona Lisa” (1986) film, Pet Shop Boys’s “King’s Cross” (1987) song along with the “late-night gay venues including The Bell, and later Central Station; artists such as Leigh Bowery performed in former industrial warehouses; lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) activists, and organisations such as the Lesbian and Gay Switchboard and the Camden Lesbian Centre… National Black Gay Men’s Conference“26 that the initiative tried to save from complete oblivion. However, final screw in the coffin of “the area as a territory of possibility in a wider world of racial and sexual oppression”27 was 2006 plan mentioned at the beginning, which in accordance with “progressive” political

4.King’s Cross redevelopment program 1993 by Foster + Partners.

4.King’s Cross redevelopment program 1993 by Foster + Partners.

ideals, is an exemplary of an urban/architectural rationalization process devoid of any subtle meaning but the capital-driven one. This can probably be observed from an ultra-sophisticated and faceless skin of newly built Google HQ and Meta at “King’s Boulevard”, Universal Music and YouTube at “Pancras Square”, or Facebook at “Handyside Street”.

Finally, it is underpinning the idea which Owen Hatherley brings up when he talks about “pseudomodernism”, a style, which in accordance with the political panorama mentioned before, is “every bit as appropriate to Blairism, as Postmodernism was to Thatcherism and well-meaning technocratic Modernism to the postwar compromise”28. Hence, we can equally state that not only it waves of modernity influenced a decline in the archi-intellectual freedom, but more importantly it has reduced architecture to a mere tool in achieving other overarching agendas.

4.Can preservation survive without the Left?

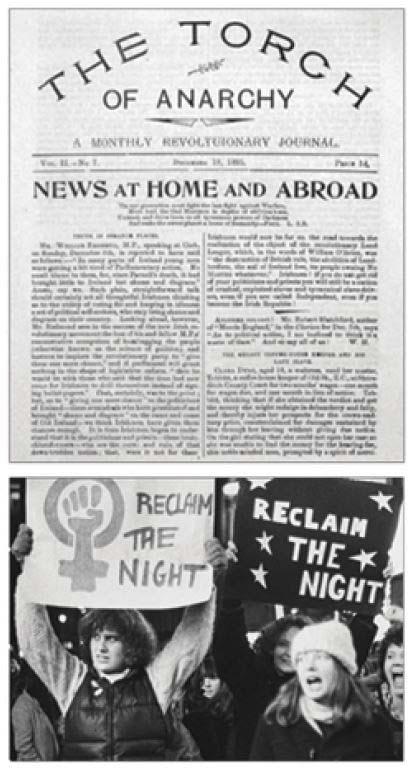

Rapid development caused by the first industrial revolution which started in the UK by the end of XVIII century instigated new political and architectural thinking, but not only, which served as a balancing tool against the overtaking mechanizing systems being introduced in all spheres of human life. This is particularly relevant in the context of arising ideas of socialism and its connections with the intellectual though crafted by John Ruskin and William Morris within the sphere of preservation of the historical objects. As primitive forms of industrial capitalism emerged during the Victorian era, with Great Exhibition in 1851 being the embodiment of the progress and technological advance, the criticism, on the other side, was claimed in “that the civilized world of the nineteenth century has no style of its own amidst (a part from) its wide knowledge of the styles of other centuries” rising thus “strange idea of Restoration of ancient buildings”29. These actions were predominantly executed through new associations such as Royal Institute of British Architects (1834), Oxford Architectural and Historical Society (1839) and Cambridge Camden Society (1839) for which to restore is to discover the originary object which is lost due to decay, to accidental or not proper alterations. Soon after, this led to the creation of Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (1877) as an answer to the arising issue of “cancel culture” by fostering principles of preservation through reports, protests while spreading the ideas abroad. Apart from intellectual work, John Ruskin particularly in the Unto This Last and William Morris in the News From Nowhere, advocated the ideas which can be regarded as precursors to socialism and equality as discrepancies within British society grew over the time. Almost 150 years later, however, the powering idea of socialism seems to be fading away while fourth industrial revolution rises from the speed and comprehensiveness of the technological systems created by

5.Neil Jordan’s “Mona Lisa” (1986) & Pet Shop Boys’s “King’s Cross” (1987).corporations in a hybrid socio-political mix of capitalistic feudalism. In this atmosphere, digital capitalists such as Facebook and Google are even deploying their own ‘meta’ realities where the role of ‘metaarchitect’ is becoming increasingly instrumentalized, reduced to a mere chain in a virtual space production process.

6.SPAB’s poster 1877.

Devoid of any social, political, spatial or historical obligations architects, in their highly specialized practice, are immersed into the world of fallacious narratives encrypted and stored in an electrical circuit. Consequently, the need for preservation is fading away accordingly as the omnipotent market economy dictates the guidelines for any kind of interventionism within the historical site, which is usually presented in the form of historical shells. In this sense, we are contemporaries to the process where our cities “seem to look less and less like Berlin [London] and more and more like Las Vegas”30 In what seems to be primarily an ideological defeat, consequently reflected on the agency of the architect, it would be of an indispensable importance to interrogate what is the role of preservation in today’s world.

4.1 Preservation as a crucial instrument of planning within the climate of capitalistic feudalism

While neo-liberal globalization of the cities is becoming predominant force which affects their pace of development, the problem of preservation of “modern” buildings becomes even more complex. According to Murray Fraser “as a global city, there appears to be a very real question over whether or not London is powerful manipulator of these powerful forces or merely the passive recipient of them?”31. We should notice that over the time, the terminology used to express the interventions on built heritage has also altered. Namely, by using the term regeneration David Littlefield distinguishes “changes and fixes applied to urban forms when attempting to arrest decay or wrest value from exhausted or troubled land”32 on one, and “masking, say, rampant commercialism or manifestations of power as, say, a social good”33 on the other side. While we could consider the term regeneration as a legal successor of the term preservation in today’s world, we should, however, carefully delineate this ambiguity by its physical embodiment in practice. Furthermore, we should equally acknowledge the importance of participative planning in a situation where “the danger in the 21st century is not that regeneration might displace communities – but that it might simply ignore them”34. In response to such threats, it is certain that the shifting environments across the globe are requiring new strategies within the field of preservation/regeneration, beside classical principles of recognizability, minimum intervention, respect for the authenticity and reversibility, which could be responsive to the current socio-political moment. This would require a redirection of attention from

preserving strictly individual objects to a wider spectrum of urban environments as progenitors of individual architectural artefacts, which could potentially offer a variety of different ways for local character of the place to be revealed. The local character which Fraser considers “as impossible to see in London”35 anymore. Furthermore, it is a kind of approach which according to Peter Bishop “works with the found condition of the site, using social and physical characteristics to best advantage and giving communities or sites the best chance of retaining any sense of place”36. He goes on a step further by proposing loose-fit planning model which in its essence underpins major principals of urban development while indirectly incorporating preservation as a constituent part. The model is guided by “strong sense of direction and vision”37 which are not based on definitive masterplans.

7.King’s Cross 2006 plan.

By keeping loose structure of the planning process, the architect lets things happen “without being entirely prescriptive” creating the opportunity for “a sound understanding of place and community, and creating chances for the unexpected and unplannable”38. When it comes to the small scale interventions, it should be noted that the modern built heritage usually offers a wide range of opportunities for their use while adopting contemporary functionalist ideology. This, however doesn’t mean that those projects should be exploited in such a way that they significantly alter their appearance compensating for the additional need for highly valuable commercial space. It is rather a process which relies on activities such as the removals of the causes of decay, minimum works for adapting the buildings to the needs of contemporary fruition, controlling and regulating the transformations in order to maintain as much as possible what is preserved without any choice with regard to “values”, as well as preservation of the authenticity of the material is essential in order to preserve the possibilities of reading and interpreting the “material document” while new interventions are clearly distinguished by usage of different materials. It is in this mixture of urban and local level of preservation practice that the architect “leaves room for complexity and the notion that places are not merely architectural, but social, cultural, political, psychological, emotional and economic”39. More precisely, creating a place instead of placelessness.

4.2 King’s Cross regeneration

In 2001 Philip Davies, director of English Heritage in London, stated in the “Principles for a Human City”, a document which preceded the creation of the master plan for King’s Cross, that they “are convinced that

the conservation-led regeneration of King’s Cross is the route to successful and sustainable urban renewal that both recognizes the area’s unique qualities and builds around the values that people place on their historic environment”40. However, despite fulfilling most of the green-agenda policies, the regeneration provided “limited provision of affordable social housing to rent (…) few defences against gentrification, few youth clubs or non-commodity meeting places and a very private sort of environment”41. In fact, in public discourse this area has usually been regarded as new Palo Alto.

8.Illustration of Palo Alto, San Francisco.

Not known to many, but the it is exactly in East Palo Alto area which along with the high-tech development in nearby neighborhood, suffered from severe social consequences of such situation. Namely, during the 90s, the area sparked controversies since it was one the list of top criminalized areas in the whole US. In this context, King’s Cross doesn’t represent an exemption. In 2019, technology investor Saul Klein held a presentation at Phoneix Court in Somers Town, neighboring area to King’s Cross. He warned that “Just across the railway tracks from King's Cross Central, and once frequented by Charles Dickens and Mary Wollstonecraft, Somers Town is the most deprived ward in the borough of Camden; according to a 2017 study, 45.9 per cent of children lived in poverty”42. In addition, the development also led to problems regarding “displacement of people, the noise, the spike in drug dealing under the construction sites' hoardings”43. Such consequences also resound in the words architect Norman Foster used in 1993, while proposing the plan for this area emphasizing “rational scientific solution to all the problems of the inner city”44. It is through this process that the intervention in 2006 proposed by Allies and Morrison, turned out to represent the space of “abjection” which “refers to spatialised processes through which the subject, or society, attempts to impose or maintain a state of purity”45. In this context, the question of preservation is highly contested since the intervention on urban scale is significantly opposing the notion of social, cultural, political, psychological, emotional and economic complexities the area once possessed. Furthermore, it extenuates architect’s argument about certain individual historical buildings being preserved (St. Martin’s School and Samsung), since they are completely deprived of the identity they constituted in a wider urban system and are harshly converted (like Samsung and old Gymnasium building) into consumer-driven spaces. However, with the approach which could’ve considered preservation as a key tool for regenerating the area, there had been a possibility to achieve much wider goals than the ones reduced to mere saving of the building’s envelopes. Some of those goals were laid out by “The King’s Cross Railway Lands Group” which challenged capitalist “proposals, and later produced their own alternative vision, Towards a Peoples’

9.Samsung building at Coal Drops Yard.

Plan (1990)”46. The main principles outlined during this critical social engagement of the locals claimed that “Plentiful and informal space, low rents, cheap land, low property values and good accessibility had resulted in a diverse community, and a range of important small-scale, socially-oriented institutions, including charities, trade unions and civil rights organisations. The campaigners countered one perception of the area as an unproductive ‘wasteland’ with a more positive one, of the railway lands as a space of radical politics, leisure and creativity. Yet the idea of King’s Cross as a place of community and cultural activity was ignored by the developers”47. Hence, instead of focusing on small scale preservation dedicated to certain buildings facades (and nothing more than that), the indispensable character for such sensitive urban condition could have potentially been found in loose-fit planning system which would allow more space for creative design approach with an open-ended character, thus providing opportunity for more inclusive and sustainable outcomes on urban level. With the unfortunate sequence of new corporate developments confirming abovementioned autopsy of the King’s Cross area today, we can, however, state that it offers a positive message on the role of preservation in our contemporary practice.

5.OMA’s 2002-2007 project for the Zeche Zollverein (Essen, Germany, 1920s–30s )

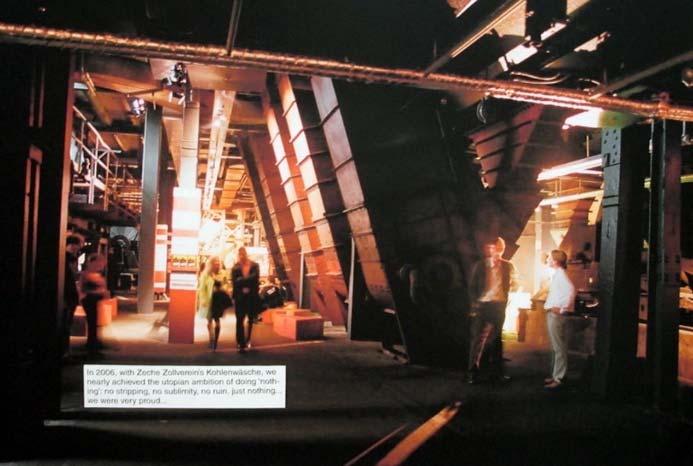

It was at Venice Architectural Biennale in 2010 when Rem Koolha as stated that “ as the scale and importance of preservation escalates each year, the absence of a theory and the lack of interest invested in this seemingly remote domain becomes dangerous. After thinkers like Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc, the arrogance of the modernists made the preservationist look like a futile, irrelevant figure” 48 . As a respond to this, OMA studio offers many interesting ways to consider th e role of preservation today, both through highly associative design works carefully incorporated into historical contexts and bright intellectual thought promoting pr eservation as a pivotal design instrument. One of those examples where “ preservation is overtaking us ” 49 is clearly delineated in the project of the Visitor Center and Ruhr Museum at the site of Zollverein mine in the city of Essen , Germany. After it had went out of service back in 1986, the site was inscribed unde r WH UNESCO li st in 2001.

11.Zollverein mine in the ci t y of Essen, Germany.

In 2002 OMA, along with other par tners, was commissioned to propose a new regeneration plan for this area. The initial idea for “ the plan was to encourage the revival of the area through a new program, a combination of business, education and information, art and design, which, along with an improvement and expansion of public space, would become a cultural center of reference”50. It is immediately evident that the architect was strongly influenced by industrial past of the site towards which the new intervention constantly points. More precisely, it is the process of creating “formless aesthetics to mediate between the viewer and the building”51 which in this case persists throughout the whole complex. By fo llowing classical principles of reversibility and recognizability, the visitors’ path lead up to 24 meters to the visitor center and museum building, are directed by routes wher e the coal once went, directly immersing the user of the space in what once was treatment chai n process of coal. After reaching the highest point of the site, visitors are primarily allowed to observe the industrial surrounding while understanding better their positi on in the overall technological process. From this point downwards, one is able to discover the interior of the main building where the process of coal cleaning was taking place, through the set of newly i nserted block of staircase whi ch, apart from its ut ilitarian purposes, serves also as a platform for various media contents to be seen . The particular accent was put on old machinery units, which were preserved in their original shape and form, vividly evoking harsh

12.Ruhr Museum approach.

mechanical atmosphere that once characterized this space. This is particularly reflected through visual interplay between aluminum and copper air ducts differen t in size and covered in dust, while being suspended on the cables and trusses which give overall st iffness to the structure. It is exactly here that according to Tim Edensor “the sensual and practical engagement with familiar space depends upon materialities, not merely the cultural understandings”52. Those materials act like hormones of imagination and allow visitors to develop their own, rather sympathetic, relationship with the ruin. By preserving the technological leftovers from the industrial period, OMA highly emphasized sensorial experience, making yet another qualitative leap in experiencing this architectural artefact. It is only at the ground level that the architect leaves the space for the Ruhr museum and more formalistic programs to develop, after the visitor has already been pulled through authentic process of reading the history of the place. From the outside, works on illumination done by Jonathan Speirs and Mark Major also contribute to the more illusive context as the building’s elevations emanate dark red light reminiscing coal heated furnaces. In this carefully staged narration, not only the history of the building, but the history of the Ruhr and all the transformations it has gone through the process of industrial revolution, become more apparent and tangible. Through this example, but not only, opposing to the current architectural design schism which is omnipresent from the graduate level onwards smartly captured in the term “stararchitecture”, practice of Rem Koolhaas, however, reminds us that “preservation is for us, a refuge to escape from starchitecture ” 53 .It is through adoption and further exploration of this critical perspective, that we might be able to stimulate positive design practices as a deriv ative of a symbiotic relationship between the traces of the past and the future, while discoverin g new paths for the ideas of architecture to be communicated in the contemporary world.

6.Conclusion

By posing the question whether “in attempting to remove grime and disorder from the urban environment, modernist planners and architects also inadvertently washed away the spirit of the city”54, sociologist Paul Hirst subtly invokes key issues in design and urban practices within current socio-political changes equally affecting each part of the world. It is the world, where neo-liberal concept of rapid development put small communities with all the complexities they bring to the place in jeopardy, while usually being clinically removed to the margins of these (de)regenerative processes. However, in what seems to be a recurring problem of tabula rasa approach, very much present in each of the four industrial revolutions in the last two hundred years, the need for more participatory and sensitive methodologies in this process equally persists. Although, the political spectrum provides us with a pretty bleak picture of a unified ideological spectrum clinging to the Right, preservation seems to be one of those neglected spheres where possibility for the voices of otherness to be properly heard lingers on. It is through gradual understanding through academic levels and consequent exploitation in real-time situations of this powerful instrument in design exercise that we should not only strive for the built heritage to be preserved in itself, but rise critical awareness of the sterile environments which are constantly being served to us. More succintly, it is a retreat from a phoenixlike regeneration, to a socially, politically, culturally and emotionally reasoned development. Hence, the preservation may paradoxically turn out to be a radical tool for laying down the avenues for socially just practices leading towards a wider goal – that of a regeneration of democracy.

Sources:

1.J. Dean, „Democracy and other Neoliberal Fantasises“, Duke Unversity Press, London, 2009, p.37;

2.Rem Koolhaas, “Preservation Is Overtaking Us”, Future Anterior 1, no. 2, 2004, pp.1-3;

3. Ibid., pp.1-3;

4.Yanis Varoufakis, “Techno Feudalism is Taking Over”, Project Syndacate, Athens, 2021;

5.J. Dean, „Democracy and other Neoliberal Fantasises“, Duke Unversity Press, London, 2009, p.36;

6.Pier Vittorio Aureli, “Recontextualizing Tafuri’s Critique of Ideology”, Log, Winter 2010, No. 18, p.97;

7. Ibid. p.97;

8.R. Mehrota, “Conservation in a Shifting Landscape”, HSD Lecture, March, 2022;

9.J. Otero-Pailos, “Supplement to OMA’s Preservation Manifesto”, GSAPP Books, NY, 2014;

10.J. Otero-Pailos, “Preservation is the Architecture’s formless substitution”, GSAPP Books, NY, 2014;

11.Pier Vittorio Aureli, “Recontextualizing Tafuri’s Critique of Ideology”, Log, Winter 2010, No. 18, p.90; 12.J. Dean, „Democracy and other Neoliberal Fantasises“, Duke Unversity Press, London, 2009, p.54; 13. Ibid. p.15; 14. Ibid. p.9; 15. Ibid. p.10; 16. Ibid. p.42;

17.A. Rossi, „The Architecture of the City“, The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1982, p.153; 18.Yanis Varoufakis, “Techno Feudalism is Taking Over”, Project Syndacate, Athens, 2021; 19.J. Dean, „Democracy and other Neoliberal Fantasises“, Duke Unversity Press, London, 2009, p.51; 20.E. Heathcote, „A place for cyberspace“, Financial Times, Online Article, 2022; 21.P. Marshall, „William Godwin: Philosopher, Novelist, Revolutionary“, PM Press, 2017, 50; 22.B. Campkin, „Remaking London“, I.B. Tauris&Co., London, 2013, p.15; 23. Ibid. p.26; 24. Ibid. p.110; 25. Ibid. p.110; 26. Ibid. p.113; 27. Ibid. p.115; 28.O. Hatherley, „A guide to the new ruins of Great Britain“, Verso, London-NY, 2011, p.13; 29.W. Morris, P. Webb, „Manifesto of the SPAB“, UK, 1877; 30.A. Daniele Signorelli, „Who is designing the architecture of the metaverse?“, DOMUS, Online Article, 2022; 31.D. Littlefield, “(Re)Generation: Place, Memory, Identity”, Architectural Design, Volume82, Issue1, 2012, p.10; 32. Ibid. p.8; 33. Ibid. p.9; 34. Ibid. p.11; 35. Ibid. 2012, p.9; 36. Ibid. 2012, p.13; 37. Ibid. 2012, p.13; 38. Ibid. 2012, p.13; 39. Ibid. 2012, p.9; 40.Argetn St. George, „Principles for a human city“, Publication 3, London, July 2001; 41.M. Adelfio, I. Hamiduddin, E. Miedema, “London’s King’s Cross redevelopment”, Routledge, 2020, p.187; 42.G. Volpicelli, “Can big tech be a good neighbor for one of the London’s poorest areas?”, Wired, Online Article, 2020; 43. Ibid. 2020; 44.B. Campkin, „Remaking London“, I.B. Tauris&Co., London, 2013, p.119; 45. Ibid. 2013, p.13; 46. Ibid. 2013, p.110; 47. Ibid. 2013, p.111; 48.C. Moorhouse, „Cronocaos and Koolhaas“, Restoration/Preservation/Adaptive Reuse, 2013; 49.Rem Koolhaas, “Preservation Is Overtaking Us”, Future Anterior 1, no. 2, 2004, pp.1-3; 50.A. Portillo, “The Ruht Museum in Zeche Zollverein by OMA”, Metalocus, 2015; 51.J. Otero-Pailos, “Supplement to OMA’s Preservation Manifesto”, GSAPP Books, NY, 2014; 52.T. Edensor, „Sensing the ruin“, Routledge, The Senses and Society, 2:2, 217-232, 2007, p.225; 53.Rem Koolhaas, “Preservation Is Overtaking Us”, Future Anterior 1, no. 2, 2004, pp.1-3; 54.B. Campkin, „Remaking London“, I.B. Tauris&Co., London, 2013, p.168;

Bibliography:

O. Hatherley, „A guide to the new ruins of Great Britain“, Verso, London-NY, 2011; B. Campkin, „Remaking London“, I.B. Tauris&Co., London, 2013; A. Rossi, „The Architecture of the City“, The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1982; J. Dean, „Democracy and other Neoliberal Fantasises“, Duke Unversity Press, London, 2009; Argetn St. George, „Principles for a human city“, Publication 3, London, July 2001; M. Adelfio, I. Hamiduddin, E. Miedema, “London’s King’s Cross redevelopment”, Routledge, 2020; D. Littlefield, “(Re)Generation: Place, Memory, Identity”, Architectural Design, Volume82, Issue1, 2012; Rem Koolhaas, “Preservation Is Overtaking Us”, Future Anterior 1, no. 2, 2004; Yanis Varoufakis, “Techno Feudalism is Taking Over”, Project Syndacate, Athens, 2021; Yanis Varoufakis, “Another Now”, Bodley Head, 2020;

Pier Vittorio Aureli, “Recontextualizing Tafuri’s Critique of Ideology”, Log, Winter 2010, No. 18; R. Mehrota, “Conservation in a Shifting Landscape”, HSD Lecture, March, 2022;

Captions:

1.https://www.techvisibility.com/2022/01/24/apple-introduced-macintosh-in-1984-and-forever-changed-the-world/;

2.A. Rossi, „The Architecture of the City“, The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1982;

3. https://www.kingscross.co.uk/about-the-development;

4. https://londonist.com/london/transport/kings-cross-station-eurostar-st-pancras;

5. https://www.criterion.com/films/648-mona-lisa;

6. https://www.spab.org.uk/about-us/spab-manifesto;

7. https://www.vitalenergi.co.uk/our-work/king-s-cross-energy-infrastructure-project/;

8. https://www.paloaltochamber.com/visitors-center/;

9. https://www.kingscross.co.uk/coal-drops-yard;

10. https://www.germangymnasium.com/;

11. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/museo-de-ruhr-y-centro-de-visitantes-3#;

12. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/museo-de-ruhr-y-centro-de-visitantes-3#;

13. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/museo-de-ruhr-y-centro-de-visitantes-3#:

14. https://www.spacehive.com/peoplesmuseumsomerstown;