Tel a un grand foyer dans son âme et personne n’y vient jamais se chauffer et les passants n’en aperçoivent qu’un petit peu de fumée en haut par la cheminée et puis s’en vont leur chemin.

One may have a blazing hearth in one's soul and yet no one ever came to sit by it. Passers-by see only a wisp of smoke from the chimney and continue on their way.

Vincent Van Gogh, letter 155 to his brother, Theo, June 1880

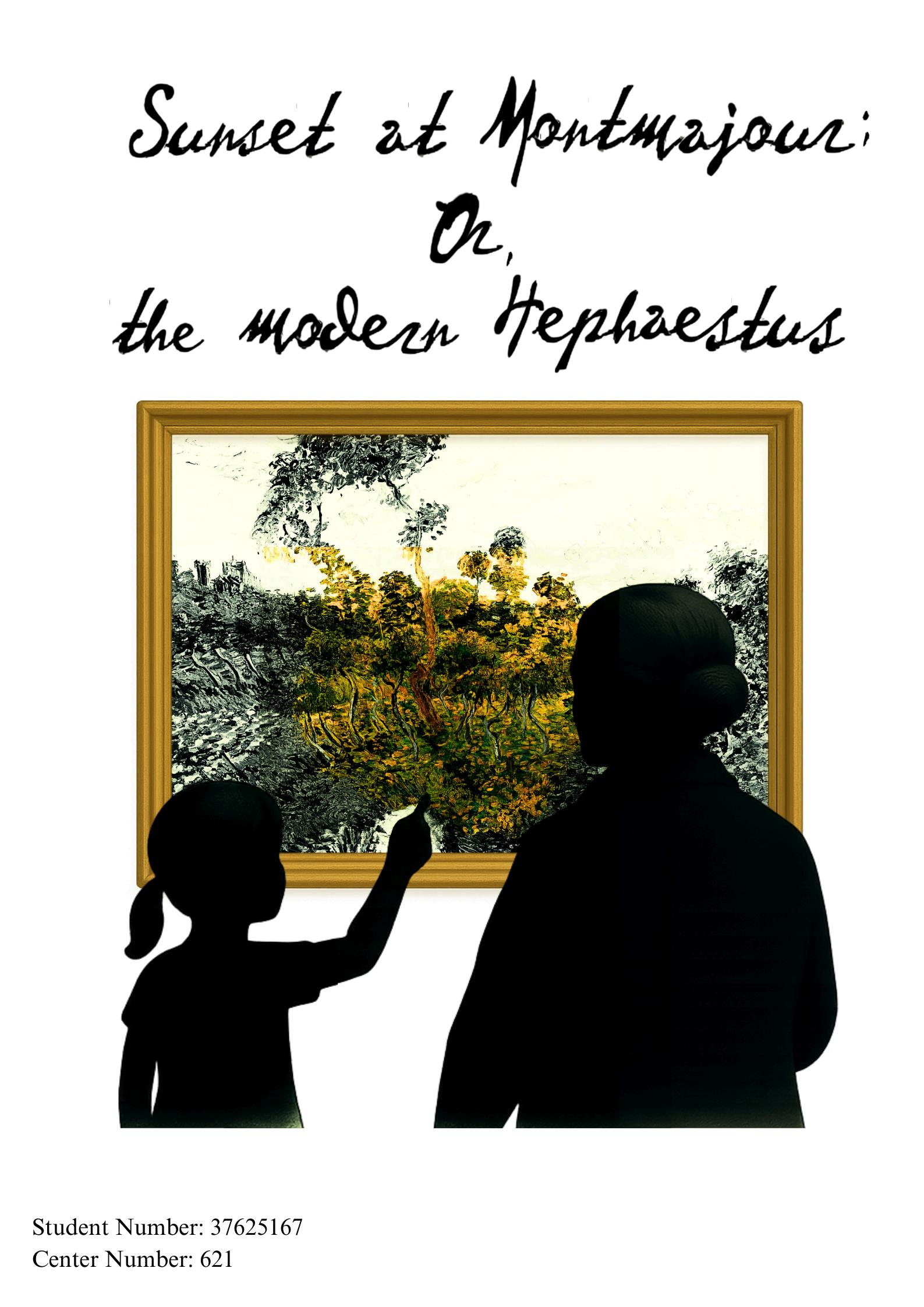

1. Thirteen Words

Sunset at Montmajour, 1888 Oil on canvas

Lost since 1908, rediscovered in 1980

Thirteen words. To them I was no more than that. Everything I was and everything I had ever been, whether it was a waste of paint on a perfect canvas or a beautiful sunset immortalized by my existence, had been reduced to thirteen words. Ironic, considering my soul was constituted of colours, shades and pigments in fact it is the very absence of words that thrust me into the darkest parts of the attic. If I had fifteen extra words, I would tell you about that attic, where I spent the majority of the century during which I was lost. If I had thirty extra words, I might also mention that I was deemed to be fake by this very museum on two separate occasions. However, to tell my story I would need to fill the entire wall behind me, and of course nobody goes to the Van Gogh museum to read. Anyway, it’s far more effective to just show you, as we all know a picture paints a thousand words. If I were to paint my story, I can imagine the words would look something like this:

2. To sum up a life

I remember the evening I was created. Pale green leaves of twisted oak trees were coated in the dark orange hue of a subdued sun. Gaps between branches revealed a sea of low hills that crept towards the ruins of an old Benedictine Abbey A few feet away from me, jagged reeds punctured clouds in the broken reflection of a small pond.

My father had a vision of beauty; he was ambitious to present himself as a poet who speaks through paint. He squinted as the dusking sun pierced the studio, and in the small black void between his eyelids I was finally offered a glimpse of myself. In his eyes I saw the perfect scene behind me, framed by an open window, but those eyes showed nothing about his thoughts of me.

A small girl wandered into the studio alone. My father spoke to her “Wait here, Marie. Your father and I have matters to discuss.”

She looked up wide-eyed. “Ok, Mr. Vincent.”

My father stretched and shuffled downstairs, rubbing his eyes. Marie was small, even for a ten-year-old. Her footsteps left scattered brushstrokes across the dusty studio floorboards. She looked into each painting as if she were searching for something specific; none of the paintings seemed to satisfy her Mousy brown hair fell just below her ears, her nose upturned and lips slightly parted. She circled the room at a slow pace, finally stopping before me, stormy grey eyes darkened by shadow. She turned her head just enough to be mysterious, as if she had practised the pose with Vermeer himself1, before twisting her face into a crushing look, reminiscent of when one steps on a cow pat or eats bad fish. It was unbearable. Her cold, colourless eyes seemed to coat me with a burning layer of acid. I remember being surprised the following morning to discover my paint had not in fact been stripped from the canvas.

A voice called her name from afar. She turned those stone grey eyes away from me, and left.

The following morning my father bundled me under his arm and moved me to a damp wooden crate barely big enough to fully encase me. I didn’t want to go. I wanted to scream but I know of only one painting that can truly do so2. My view was limited to the crate walls and the gabled roof of the studio, yet I still enjoyed watching the evening shadows dance as I was reminded of what I was meant to be. A number of sketches joined me: the hills, the pond, the oak trees, all unfinished, yet I felt that they were more than I was.

1 Vermeer, Johannes Girl with a Pearl Earring 1665

2 Munch, Edvard. The Scream. 1893

One day, many weeks later, I saw my father frown briefly as he put a lid on my box. That was the last time I saw him. No goodbye, no nothing.

For what I believe was no more than a single fall of the sun, I heard nothing and saw no more. The painful silence was broken by a cacophony that nearly splintered the brittle wood of my frame; the rhythmic beat of pistons pumping was accompanied by the shriek of whistling steam and grinding metal rapidly approaching.

I moved from train car to train car, place to place. One thing I remember from the journey was an argument I overheard between two carriage drivers about the appearance of a giant red metal tower being constructed in the middle of the city

3. Of love and of loss

Following many more hours of travel, the crate finally came to rest. I was showered with golden light once more as the lid was removed. Looking down upon me was a face that looked astonishingly similar to my father ’s, however far more youthful. Streaks of russet highlighted a thick brown moustache. The corners of his mouth were twisted into a curious smile, one eyebrow sat slightly above the other. This was my Uncle, Theodorus. He retrieved the sketches from the crate, examining them one by one. His expression periodically shifted as he flicked through the pages, cycling through looks of surprise, longing and amusement.

As he finished scanning the final sketch, his gaze shifted to focus on me. He carefully picked me up, extending his arms for a complete view of my composition. As I was lifted out of the box, I was finally given a view of my surroundings. The room was small, littered with what must have been nearly one hundred paintings. Behind Theodorus, a single window framed an enormous and

unfinished red tower . Theodorus muttered something about a signature before he flipped me to face away from him, and read a note stapled to my frame. At the time, I had no idea what it said but I found out later it was my birth certificate. It was my name. It read:

“Fourth of July, 1888; Sunset at Montmajour Dearest Theo, yesterday, at sunset, I was on a stony moor, where very small and twisted oaks grow, in the background a ruin on the hill, and cornfields in the valley.”3

His eyes darted towards me. His smile dulled as he compared the poetic description of what I was meant to be to the distasteful mess of colour in his hands. Theodorus sighed as he set me down in a corner out of view. More acid to my oil.

And so I sat in shadow for eleven years, a dying piece of my father ’s soul. Theodorus would visit his collection, softening the parquetry with bitter tears that begged for his brother's return. The years had shed cataracts of dust over my body, such that everything I saw was tinted with a fuzzy grey. Theodorus too had gone grey and pale. For weeks he would not visit, and when he did, he seemed to have aged decades. His face was a blend of sickly greens and whites, his eyes had glazed over and his lips had gone dry He soon stopped visiting, and I thought I had been lost.

At one point a woman unfamiliar to me, a tired old widow, sat on a lonely chair in a corner of the room her clothes an arrangement of grey and black4 and examined her vast storage of unwanted things from Theodorus’s collection, myself among them. My siblings and I were sent to be adopted by various collectors. I recall the widow returning day by day, taking with her as many paintings as she could carry, as I watched the once claustrophobic little room become an empty shell, filled only by the insignificance of myself and a few others.

3 Vincent van Gogh, Letter 636, to Theo van Gogh 5 July 1888 vangoghletters org

4 Whistler, James McNeill. Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1 // Whistler ’ s Mother. 1871

4. And to ignore the worth of a soul

My turn came, and like the others I was carried out onto the busy streets of Paris. As the sun hit my paint, I caught a glimpse of the now completed tower It was magnificent. How anybody (even a carriage worker) could fail to see its beauty was beyond me. Street by street, gallery by gallery, I was rejected. Eventually a shrewd art dealer wearing a blue pinstripe suit accepted me for what couldn’t have been more than one hundred francs. The man kept me on the top shelf of the storeroom behind his gallery, waiting for the perfect customer. I was kept just high enough to be able to see through the little round window the only source of light on the other side of the room.

Once every few months, the storeroom door would creak open and the art dealer would enter accompanied by some sort of critic, who would intently examine each and every artwork. I was often glanced at, and then ignored until the critic took his or her leave. I remember one suggesting I be given away as a gift alongside a “better” purchase. I often felt as though even a canvas painted entirely black, with nothing to say, would be listened to more than I ever was5.

Eventually, I heard the door open for the final time. First, the art dealer entered with an excitability I had never before seen him possess. He was followed by a tall, sturdy man of about thirty, who entered with the command of Napoleon crossing the alps6. Strong cheekbones were propped up by the curls of a neatly trimmed handlebar moustache. He wore a charcoal three-piece suit and a bowler hat, his weight supported by a sleek gold-tipped cane. I hadn’t even noticed the young lady who had entered alongside him until she clumsily tripped over a poorly placed broom.

5 Malevich, Kazemir Black Square 1915

6 David, Jacques-Louis. Napoleon Crossing the Alps. 1805

The art dealer helped her to her feet, brushing some dust from her shoulder, before speaking to his prospective customer.

“If it’s not out there I am certain it’s in here, Mr Mustad7 Remind me what it is you are looking for?"

The tall man spoke with an accent unlike any I had ever heard, in a voice that matched his appearance deep, but elegant.

“Any works from a Dutch man, Victor Vaughn Grande —”

The young lady shyly interrupted.

“I think that’s Vincent Van Gogh, Mr Mustad.”

“Whoever he is, Mr. Thiis8 told me his stuff is going to be worth a fortune before the end of the Tour De France and after that Munch piece that Mr. Thiis found me sold for a fortune, I simply can’t ignore his advice.”

The art dealer silently scanned the room, narrow-eyed. His eyes locked on to me, and he froze. The corners of his mouth twisted into a conniving grin.

“Perhaps you are looking for this, Mr. Mustad?”

He gestured towards me as if he were a royal footman inviting the King into his carriage. Mr. Mustad stepped closer. The art dealer had already prepared his fable.

“You’re looking for Vincent Van Gogh, yes? I recall the day Vincent himself sold me this painting. He’s a talented young man, isn’t he? A nice boy too. Bought this one off him for a thousand francs. I wonder how he’s doing.”

7 Mustad, Nicolai Christian (1878-1970)

8 Thiis, Jens (1870-1942)

The young lady raised a suspicious eyebrow, likely because by that point my father had been dead for nearly twenty years. Mr. Mustad thoroughly examined me, his eyes glittering with expectation. After some minutes, his face relaxed and he stepped back.

“Yes, this is the one. I will have it. How much do you ask?”

The art dealer sprung into action once more.

“For you, Mr. Mustad, I can give you this piece for two thousand.”

The young lady seemed to frantically object, however before she could speak, Mr Mustad had summoned a thick stack of bank notes from inside his jacket and the art dealer wasted no time accepting it.

Through a wicked grin, the art dealer offered to carry me to Mr. Mustad’s car, the “silver ghost”9 he called it he joked that he’d only need ten more customers like Mr. Mustad to get one for himself. Before I was placed in the trunk of this “ghost”, I caught a glimpse of its magnificence. A sleek mechanical carriage, built from moonlight, softly purring like a giant metal cat. Inside were thrones upholstered in black leather so fine they looked as soft as the wind through a wheatfield, yet as dark as the crows soaring above it10

We rolled out of Paris beneath a starry night11 that was smudged by the smoke and soot from awakening chimneys. In the following days, I was left by Mr. Mustad to be wrapped and packaged in a spacious crate, before I was carried by iron rail through cities whose names I never learned. There was a ship too, which carried me across a vast ink sea and my crate was rocked by great waves so powerful I could only imagine how they would dwarf even the highest peaks12 Salt and rust softened my frame and dulled my hues.

9 Rolls Royce Silver Ghost 1906

10 Van Gogh, Vincent Wheatfield with Crows 1890

11 Van Gogh, Vincent The Starry Night 1889

12 Hokusai. The Great Wave off Kanagawa. 1831

Upon arrival, I was removed from my crate to be greeted by snow like a blank canvas. Quiet roads and eccentric mansions spread across a waterfront hill. From there it was a slow ascent by horse and cart (nothing like the “silver ghost”) through frostbitten trees and alongside sparkling still lakes. The town stretched out beneath the hill like a half-finished sketch in charcoal and white chalk, its fjord-side horizon cut with the clean geometry of winter. The silence of the landscape felt less like absence than negative space, awaiting a painter ’s hand.

I finally seemed to have reached my destination when the driver came to a halt before a towering ivory manor. It stood in the vein of a 19th-century Norwegian revival estate pale stone and timber carved with a craftsman’s patience. Here I was reunited with Mr Mustad, who promptly ordered that I be hung at the far end of the dining room. A long mahogany table stretched before me, surrounded by high-backed chairs cloaked in rich burgundy fabric. On either side of the room, the walls were lined with exquisite paintings, as if they too sat around the table and I was at the head. In the middle of the room hung a crystal chandelier so large I could see my own reflection in the lowest hanging shards.

Mr Mustad loved to show me off. His guests would enter the room, already starstruck by its sheer grandeur, before he would usher them past his other paintings as if they were mere stains on the wall. He would stop before me and boast my father ’s name to the room, people and paintings alike.

“A one-of-one Van Gogh. Found it myself in the backrooms of a proletariat art dealership in Paris.”

This would usually earn gasps and looks of awe, which he would respond to with a beaming smile before inviting his guests to be seated.

On a particular evening, as he gave his usual speech about my magnificence, the dining room table was laden with wine and roasted meats, a spread fit for a last supper13 beneath the glittering chandelier. Mr. Mustad gestured toward me with his usual flourish, his voice swelling with pride, but at the far end of the table a balding man of about sixty leaned back in his chair His silver ducktail beard twitched as he pressed his lips into a thin line, emerald eyes fixed on me without awe, his fingers drumming against the table as though each word from Mustad cost him patience14. Then he interrupted in a monotone voice:

“There is no signature.”

The enthusiasm crept out of the features of Mr. Mustad’s face.

“I beg your pardon, Mr Pellerin?”

Mr. Pellerin had arrogance enough to enrage a priest.

“I have collected a number of works by Vincent Van Gogh over the past decade. Not a single work of his in my collection lacks a signature. This, Mr. Mustad, is a replica.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, and nor could Mr Mustad as it seemed. He was enraged, he wanted to argue, yet he knew he was too uneducated to respond.

To this day I still believe that if I could choose one moment in my life to be given a voice, it would be in that very dining room. I would have given anything to tell Mr. Pellerin he was wrong, to watch his insufferable haughtiness break down before me. But I couldn’t. Instead, I watched as Mr Mustad furiously yelled at his servants to have me removed from the wall before dinner had even started. When the servants asked where I should be taken, he spitefully responded, “Take it where I will never have to see it again!”

13 Da Vinci, Leonardo The Last Supper 1495

14 Matisse, Henry. Auguste Pellerin II. 1916

And that was exactly what they did. I was carried up two spiralling staircases, before being lifted up a rusted metal ladder into the shadows of an attic. As I rose, the house seemed to fall away beneath me chandeliers, banquets, and voices shrinking into faint embers the ascent twisting into a descent, as though I was being lifted not into air but into a furnace above, each step higher carrying me deeper into the underworld. The last thing I saw was a servant’s skeletal hand pull shut the attic’s trapdoor before I was thrust into darkness.

5. Once in darkness

The darkness suffocated me. At first it was silence, dulling thought until even waiting felt endless. Stillness thickened into torment. I saw only black on black, felt only splintering wood, and all that kept me alive was the persistence of memory15

Until I heard everything.

It began with the bells of a church, not too distant, yet neither too close. They chimed daily, not as a call to prayer, but as a reminder that time was still moving. The rhythm of horse hooves on gravel became less frequent as it was replaced by a low mechanical hum. Though I tried to drown it out, I could not ignore the polite laughter and clinking cutlery from the seemingly endless dinners below. Firewood crackled in the hearth the slow-burning warmth I never felt.

Years passed and I painted the town as I heard it. It was an unfinished project, as old sounds were replaced with newer ones I had never heard before, but I didn’t mind this as there were endless possibilities of what might have caused them. There were fireworks outside, I think bursts of light and thunder that shook the floorboards and made the house hold its breath, and somewhere beneath it all, voices sang or screamed, I couldn’t tell which, but they sounded so full of feeling I

15 Dali, Salvador. The Persistence of Memory. 1931

almost wished I could join in. I pictured the snow-covered streets illuminated by bright lights and populated by people singing and dancing with joy. I heard languages I had never heard, and I imagined how the town would grow to be full of all kinds of people.

Amongst all I heard, my favourite sound was the rain. The rain was always honest. When I heard the familiar tapping of droplets above me, I knew the clouds were still out there, the trees still bent, the world had not forgotten how to weep.

I don’t know how much time had passed before the veil of shadows was lifted; the void retreated just enough to give shape to the forgotten figures that hid in the darkness. Now I could see that sharing the small space with me was a horse in one corner and a guitar in the other The horse, shackled by its own rockers, could neither gallop nor trot. Rather, it stood still, head held high. Its white coat, betrayed by the curse of time, now barely protected its walnut skin from the cold of winter. The guitar looked younger, not much older than I was perhaps forty. It slouched against a crate like a drunk aristocrat. On a black torso it wore a beautiful ivory floral design, like a vest under a coat of dust. Its perfect strings still dreamed of melody, though its tuning pegs had long since snapped off like teeth from an old smile.

I quickly learnt their names, or at least I think I did I can’t remember them actually telling me. The horse’s name was Meleager16, and the guitar was Linus17, though I called them Mel and Lin. I remember the thousands of stories they told me on the quietest of days, when the wind held its breath and loneliness sat beside me to listen.

Mel told me he used to fly with wings like a dove18, destined to carry his best friend his creator ’s daughter to the moon. When his creator ‘the snake haired witch’19 he would call her discovered their plan to leave, she cursed him to be made of wood. He told me he didn’t

16 Homer Iliad, 9 529–99

17 Homer Iliad, 18 541

18 Hesiod Theogony, 280

19 Hesiod. Theogony, 275

miss his wings, he just missed the little girl who once loved him. Mel was bought by Mr. Mustad’s parents as a toy, but the boy never played with him, and so he was banished to the attic.

Lin was Ramón’s20 first guitar, and he always spoke of Ramón with a trace of spite. Ramón had bought him as a boy, and together they filled cafés with music that drew crowds from across Spain. For a time they were inseparable, half and half of the same act. But just before their first tour, a single accident snapped one of Lin’s tuning pegs. It could have been fixed, but Ramón saw only weakness and replaced him with something newer. Lin was given away, picked apart for parts, and finally abandoned. Eventually he ended up with Mr. Mustad, who had no love for music and so Lin was silenced.

6. Is to ignore the pain

One summer, a maid carried a tall giltwood mirror up into the attic, fussing about its cracked corner. It was to be hidden away until someone decided whether to mend or discard it. It stood opposite me on the far side of the room, capturing my image the way a dirty pond paints the sky dark, warped, and littered with nameless shadows.

When the mirror came, Mel and Lin stopped telling me their stories; the darkness muted them once more. I peered into the mirror as if it were a window looking onto a place far from light, perhaps a basement cold, damp, used only for storing old or broken things that had no place in the house above. In the bright hours, I saw myself clearly in this window, as if I stood outside peering in, but when night came, the shadows drew themselves across the glass like curtains before midnight, hiding my reflection from me once more. But one day, as the sun rose, I saw that mirror differently I expected to see myself staring back at me with the familiar look of desolation, longing to escape the dim glass cage.

I saw the opposite.

20 Ramon Montoya

I did not look trapped. I did not look afraid.

The reflection looked at me.

Not through me, not beside me at me.

Its colours were richer, almost freshly dried. The strokes were sharper, the frame polished, uncracked. It looked as I imagined I must have once looked in Vincent’s hands. But it wore no warmth. And then it smiled. Not a joyous smile not the Mona Lisa’s mystery, or the laughter of a child. It was the quiet grin of someone who knows your every flaw, and loves none of them. That was the first time it spoke.

"So this is what you've become."

Its voice was dry as dust. Not a whisper, but the sound of memory turning sour.

"They never hung you. He never signed you. And now even the rats have more to do than you do. Do you think anyone actually remembers that you’re up here?"

I wanted to shout, to tell it that it was wrong but I had no mouth. I wanted to look away but I had no eyes.

So I listened.

"You're not a painting. You're an accident that no one had the heart to throw away."

I was paralysed, framed in a never-ending moment, like Prometheus watching helplessly as the hungry eagle approached him once more21 tortured day after day with no escape. For days,

21 Snyders, Frans and Paul Rubens, Peter. Prometheus Bound.1611

maybe weeks, it grew louder, the sound of the reflection. I tried to retreat inward, to hide from it, but that only gave it another reason to laugh at me.

The laughter came low at first, like paint cracking in a cold room. Then louder It leaned closer somehow, though it never moved. The laughter lingered like smoke. Then silence. Not peace, not quiet. Just absence.

And into that absence came a voice. Low. Even. Unhurried.

"You’re not listening to him, are you?"

Mel. His voice rose like a red sun above the silent hours22 not blazing, but sure of its place in the sky The mirror dulled in its glow The attic seemed warmer The shadows flinched.

"That thing in the glass it’s not your reflection. It’s your doubt, dressed in your colours."

I stayed still.

"You think worth comes from being admired? I was born to fly Built to gallop through dreams and stars. But I’ve never touched a cloud."

He rocked once, slowly, the creak of old wood like the groan of a distant ship.

"Still, I exist. I remember why I was made. And that’s enough to make me real."

Mel’s words settled into the silence like dust on the mirror. And then, from the corner, another familiar voice.

“He’s got that smug look again, doesn’t he?”

22 Monet, Claude. Impression, Sunrise. 1872

Lin.

“That little glass gremlin. Always so dramatic. ‘You’re a failure,’ ‘You’re forgotten,’ blah blah blah. You know what else is forgotten? The third verse of every flamenco song. Doesn’t make the first two any less brilliant.”

He tried to strum, but the sound came out crooked. A wheeze, a rattle. Still he tried.

“Look, kid. I was a legend. Candlelit cafés, open-air stages, crowds that cheered like thunderstorms. And then—”

I pictured him gesturing to his snapped tuning pegs with theatrical flair

“Whack. One peg gone. Suddenly I’m not even worth the memory of my journey.”23

He paused for a moment.

“But here’s the trick. People only see what you do for them. Not what you are. And what you are—”

I could have sworn he tilted towards me.

“—is still here. You’ve outlived them all. The critics, the dealers, the dust. Even that mirror. You’re not just a painting anymore. You’re a survivor. The point is,” Lin said, voice quieter now, “it’s been a lifetime since anyone has clapped for me, and nobody ever clapped for Mel. But he still listens to my off-tune morning songs, and I still listen to every single one of his stories, no matter how boring they are. And that that’s worth something, isn’t it?”

I looked at them both old, broken, but not forgotten. Not bitter, nor hollow.

23 Margritte, René. Memory of a Journey. 1955

Not mirrors.

I saw it. What had haunted me all this time wasn’t a reflection. It was a twisted memory wearing my face. A lie I had let live too long.

I grew the courage to think, "It’s wrong". I did not say it aloud. I could not say it in words. But the attic heard it. The mirror heard it. He heard it. And I knew I heard it.

The glass didn’t shatter like thunder. No jagged shards. No crashing.

It cracked softly, a fine silver thread across the centre, a painter ’s signature where there had never been one.

7. Of liberation

Then one morning, the door opened.

Footsteps. Sharp voices. Dozens of them.

“This must be the attic. Start hauling it all down furniture, crates, everything.”

“The auction house wants everything catalogued by next week.”

That was when I understood: Mr. Mustad was gone. The man who had locked me away had passed, and now the house was being emptied piece by piece, memory by memory Dust rose as boxes were opened. Old coats were thrown into piles. A cracked music box played half a tune before going silent again. Mel and Lin were still there, buried in shadows.

And then someone found me.

8. And to silence

They carried me out without ceremony Down the rusted ladder Down the spiralled stairs. Past Mel. Past Lin. Past the mirror, now dulled with dust and silence. I was wrapped in brown paper and twine, stacked among other forgotten things. No one spoke to me, but I heard them speak around me.

“Just some old junk from the attic.”

“Looks like a painting, but it’s unsigned.”

“Probably decorative. We’ll lot it with the others.”

And so I became a number again. I was placed on a table, then in a van, then against the wall of a warehouse that smelled of dry wood and deadlines. Catalogued. Photographed. Estimated. Auctioned. Someone bought me. A collector, I think. I never saw his face, only the ceiling of his hallway and the backs of other, better frames. I hung in silence for what seemed a long while but I found out later I was in that hallway for no longer than a few weeks. The only sound was the ticking of a clock too far away to see. *

Then one day I was sent off again. Packed tighter this time. A new box. A colder truck. I arrived at a gallery with white walls and voices that wore shoes louder than their words.

They wanted to know who I was.

“Possibly Van Gogh,” one said. “Late 1880s, Arles. But no signature.”

“Could be a student’s imitation,” said another. “Or just wishful thinking.”

I was taken to Amsterdam. Hung briefly in a small backroom of the Van Gogh Museum.

For a few weeks, scientists examined me with lights and chemicals and conversations in clipped Dutch.

And then they said no.

“Not authentic.”

“Unverified.”

“A romantic forgery.”

I was sent away Again. It was not the first time I had been dismissed as false, yet the wound did not dull with repetition each rejection tore as sharply as the last.

Years passed. I don’t remember how many. Enough to forget the names of the places I was stored. Enough to forget the sound of shoes on gallery floors. Enough to wonder if maybe the mirror had been right after all.

Then, decades later, I felt something shift.

Hands returned. This time gentler. More deliberate.

“We’re taking another look,” one of them said.

“New imaging methods. Thread counts. Letter references. There's something about this one.”

I was laid flat beneath lights. Scanned. Traced. Compared to old letters written in ink and sorrow. They whispered numbers inventory numbers, canvas roll matches, brushstroke parallels.

Then one morning, a man stood over me reading a letter The more he read, the more I saw his eyes widen as if he had finally found gold after a lifetime of panning through dirt.

“It’s him,” he said to a colleague. “It’s Vincent.”

“How do you know?”

“Read this”, he handed his colleague the letter His colleague read fragments of it aloud.

“Fourth of July, 1888 the date adds up Sunset at Montmajour. Dearest Theo… where very small and twisted oaks grow… in the background a ruin on the hill… cornfields in the valley.”

For a moment he paused, staring at the page.

“You’re right, it’s Vincent.”

I was brought out into the light.

Real light. Museum light. Not the sunlight of Arles, but something cleaner. Softer. The air was still and temperature-controlled, but it hummed with life. They hung me on a white wall, under glass, with a plaque that finally gave me my name. It was thirteen words.

Sunset at Montmajour, 1888 Oil on canvas

Lost since 1908, rediscovered in 1980

*

In the quiet hours, when the gallery emptied, I listened to the voices of curators and lecturers drifting through the halls, their words weaving together the stories of the works that surrounded

me. It was through them that I came to know the language of other paintings, their triumphs and their tragedies. For weeks, maybe months, I had everything I ever wanted. Crowds. Gasps. Cameras raised like sacred offerings. Children pointing. Aesthetes weeping. Tourists saying my name aloud as if they’d always known it. “Sunset at Montmajour.” I liked this name. It was the only one I had ever had.

I became a headline.

“The missing masterpiece returned.”

“First Van Gogh painting discovered in 85 years.”

“Unconvincing Van Gogh From attic to museum.”

And for a moment, it felt like vindication. Like the applause after a mime’s silent performance outside a small Parisian art dealership. Like everyone might finally hear what I had to say even if I could not speak.

But then, slowly, the applause faded. The crowds thinned. The museum closed each night. And yet I didn’t feel empty Because somewhere in the quiet hours, I remembered what Mel had said. What Lin had sung.

“I remember why I was made. And that’s enough to make me real."

“People only see what you do for them. Not what you are. And what you are is still here.”

I knew I was no longer desperate to be looked at, because I had already learned to see myself

9. A story untold

And then, rounding the corner was a little old lady She was wearing pearls and a loose frock. She carried a cane in her left hand. But it was what she held in her right hand that was truly unbelievable, for it was the hand of Marie.

She was just as I remembered her, with short mousy brown hair and curls that nipped her ears. Her nose too, small and upturned, sitting above a smirk worthy of the Louvre24. She looked no older than fourteen. Then I caught her eye, but it was different this time. It was as if she didn’t recognise me. Those beautiful grey eyes I remembered so well were not below her crinkled brow Instead they were a soft, warm brown.

The grey eyes, the ones that had scorned me so many decades ago, the ones that had shredded me and coated me in acid, rested above the wrinkled cheeks of the old woman. How could I be so foolish? It had been a lifetime since I last saw the girl and I was caught by such surprise that I’d failed to consider the weathering of time. And yet here Marie was, flanked by her granddaughter, a moment that I had dismissed as only possible in thoughts forgotten between brushstrokes.

I could see the myriad pigments from which my father had crafted my body finally reflected on the canvas of her stormy grey eyes. As she looked at me, they were no longer grey, but a swirling dance of yellows, greens and blues. And through her eyes I saw myself as she did in that moment, as the missing piece of my father ’s soul.

Every moment of judgement then dripped across my canvas; judgement as a worthy piece of Van Gogh’s oeuvre, as a skilled but ultimately worthless imitation of a master, and as a tasteless abomination vomited out by a Dutch peasant. Suddenly none of those judgements mattered. The reflection in Marie’s eyes told me all I needed to know Not the reflection that had tortured me relentlessly, but instead the reflection of a priceless painting, illuminated by the soft glow of the light above it, like the dusking hours of a beautiful landscape, a sunset at Montmajour25.

24

25

Title page (page 1) image created by me