Introduction

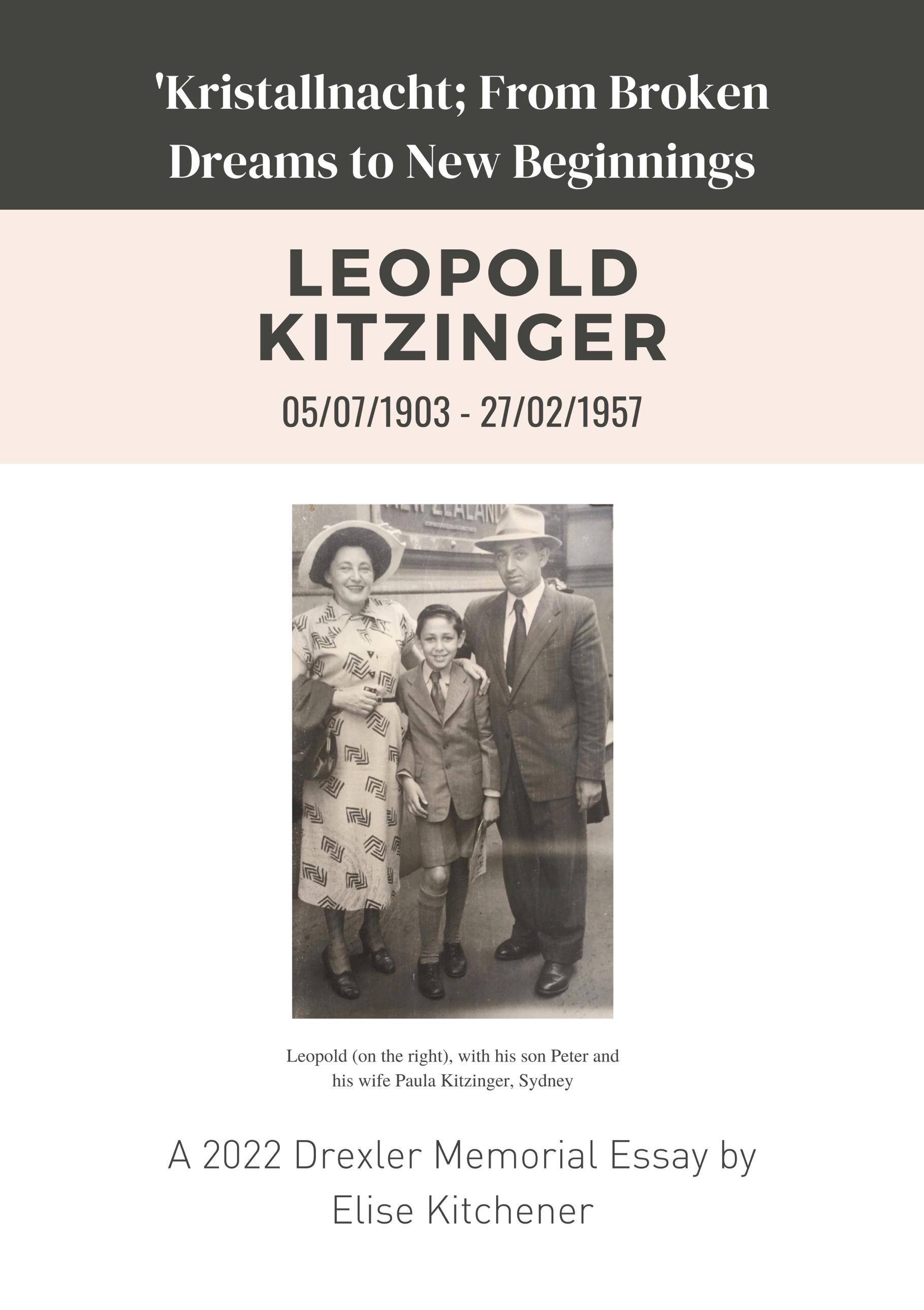

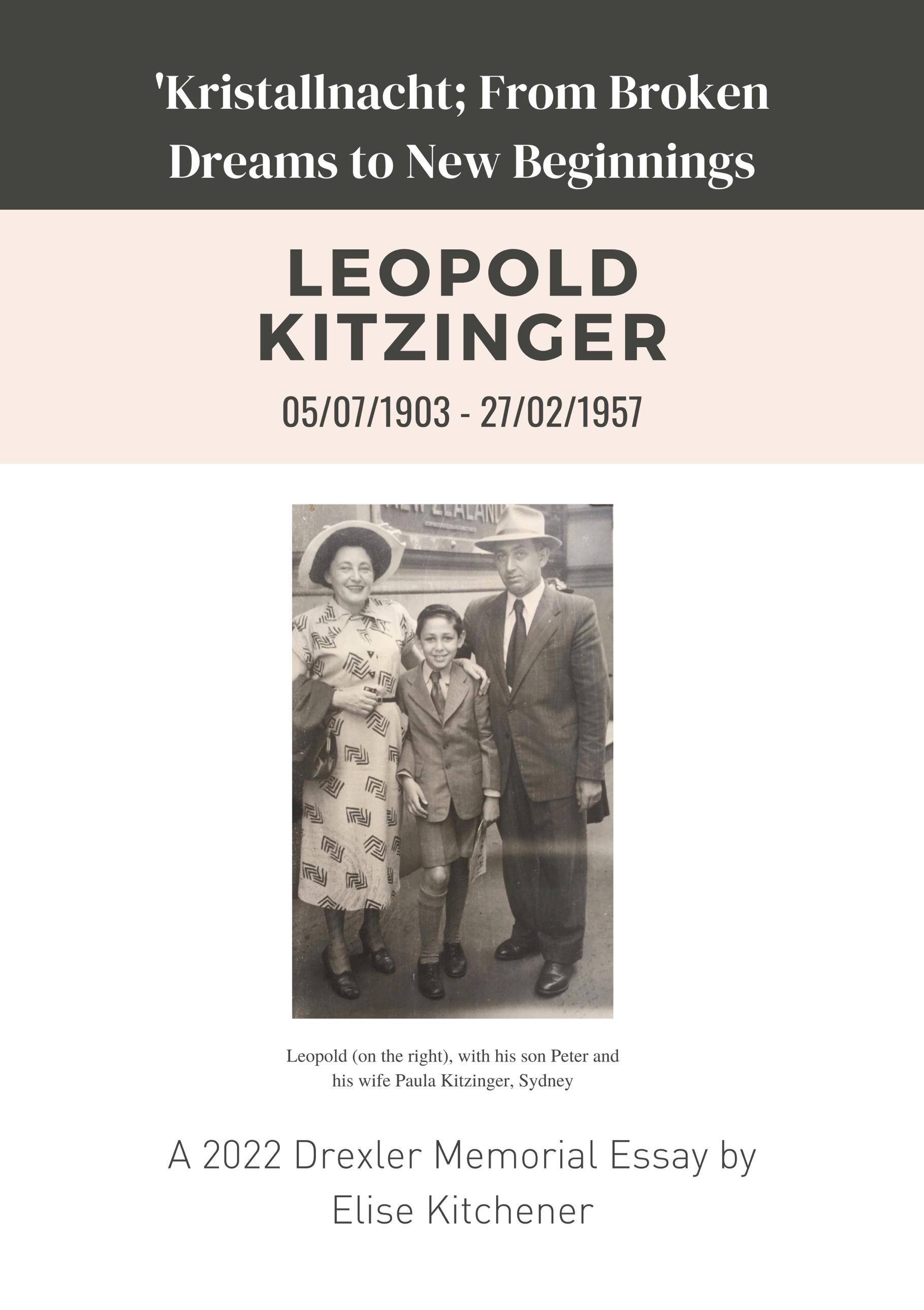

This is a story of a brave, determined survivor, who saw the unspeakable atrocities of Adolf Hitler’s reign. Leopold Kitzinger was my paternal great-grandfather, and he survived the Holocaust. Leopold grew up in Memmingen, Germany and later met his wife, Paula. On Kristallnacht, Leopold was arrested and sent to Dachau, a concentration camp in Germany. He spent eight weeks there, was released, and got a visa for Australia in 1939. They lived in Canowindra, a township in NSW, and then in 1946, they settled in Sydney.1 Leopold passed away on 27 February 1957. However, his memory still lives on through my grandfather, Peter Kitchener, who was born on 2 October 1941. I have been interviewing him to gain insight into his father’s experiences during the Holocaust.

I believe that Leopold’s testimonial story is extremely important and should be recorded for future generations. I feel that it’s my responsibility to tell his story because I am a part of his legacy and must ensure that the world will never forget the mass genocide that killed around 6 million of my people. We must continue to share their stories and preserve their memories.

Background

Leopold Kitzinger was born in Memmingen, Germany on 5 July 1903. He grew up in Memmingen, which was a small village with a substantial Jewish community. My grandfather said, “it was a very anti-semitic town”.2 In 1895, 231 Jewish people lived in Memmingen and the synagogue opened in 1909. However, the Jewish population decreased to 161 in 1933, the start of the Holocaust, and then to 104 by 1 January 1939, after Kristallnacht.3 This was due to the Jewish people who escaped, were arrested, sent to concentration camps, or were murdered.

Leopold and his family lived within the Jewish community, he grew up as a religious

1 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

2 Ibid.

3 J.V.L, ‘Memmingen’, Jewish Virtual Library, 2022, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/memmingen, (accessed on 24 July 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 2

Orthodox Jew and often went to synagogue.4 He lived with his younger sister Bettina (born in 1905) and their parents, Emil and Klara Kitzinger, who are my great-great-grandparents. Most of his childhood was centred around his family’s Jewish traditions and culture. He learnt Hebrew at home and then at synagogue from age four. They had Shabbat dinners and did the Kiddush and grace after meal.5

Leopold went to the only school in Memmingen and my grandfather, Peter, said “there was a lot of antisemitism against him at school. He didn't give descriptions of it, but I would imagine he got beaten up.”6 After he graduated, he became a travelling salesperson, which was a highly respected job. He earnt a steady income, although Leopold’s family weren’t wealthy.7

Pre War Context

In Germany, in 1933, the Jewish population decreased to 0.75% of the total German population.8 This was due to antisemitism that occurred when Hitler came into power in January 1933 and caused an estimated 37,000 Jews to flee from Germany.9 Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor, Führer, by the president, Paul von Hindenburg, on 30 January 1933.10 He was not elected by the German citizens, and would soon transform German democracy into a dictatorship; the rise of the Third Reich.

Leopold stopped being ultra-religious in the 1930s when Hitler came into power. He felt threatened to express his beliefs, so he hid them.11 Leopold and Paula also had non-Jewish

4 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

5 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 12/9/2019.

6 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

7 Ibid.

8 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Germany: Jewish Population in 1933’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.), https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/germany-jewish-population-in-1933 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

9 Ibid.

10 A.F.H, ‘Germany 1933: From Democracy to Dictatorship’, Anne Frank House, (n.d.), https://www.annefrank.org/en/anne-frank/go-in-depth/germany-1933-democracy-dictatorship/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

11 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 3

friends in Germany, but they didn’t keep in touch with them as some of Paula’s friends became Nazis and destroyed their home on Kristallnacht, 9-10 November 1938.12

Leopold and Paula broke up for a short time as he fell in love with a non-Jewish woman. Leopold dated her for a while, however, in the early 1930s they were forced to break up due to restrictions Hitler put into place.13 Leopold was classified as a ‘full Jew’, according to the Nuremberg Race Laws established on 15 September 1935, as he had four Jewish grandparents.14 The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour meant that he couldn’t be with his girlfriend due to the possibility of inter-race marriages and mixed children, which would disrupt the pure Aryan race which Hitler aimed to achieve. Furthermore, the Reich Citizenship Law declared that Leopold couldn’t hold German citizenship, depriving his political liberties.15 After this heartbreak, Leopold got back together with Paula. They married in April 1936, only 7 months after these legislations were put into action. He was 32 years old.16

12 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

13 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

14 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘The Nuremburg Race Laws’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nuremberg-race-laws (accessed on 29 July 2022).

15 Ibid.

16 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 4

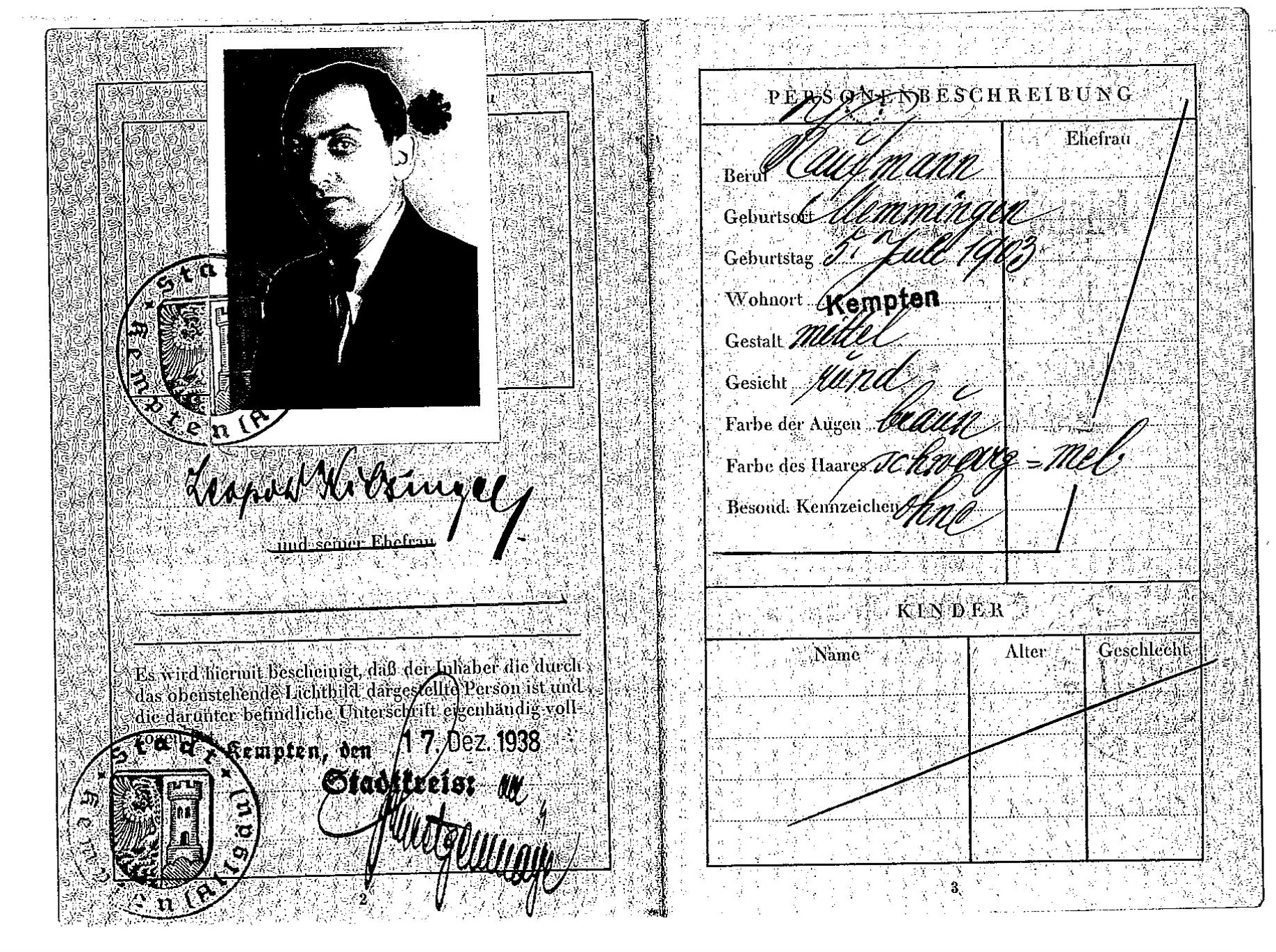

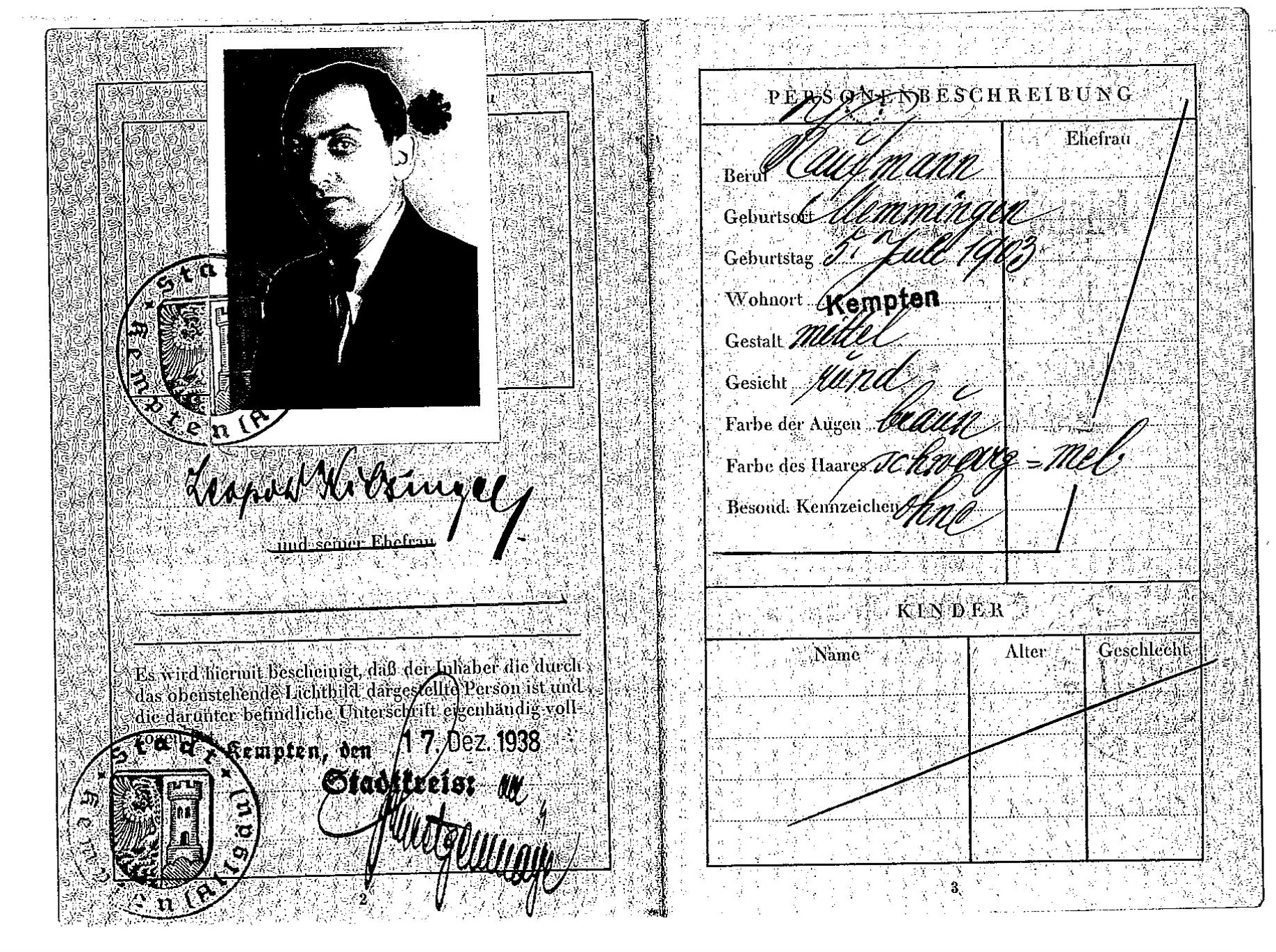

Figure 1 Leopold's German-Jewish Passport

Start of the War and Nazi Ideology

World War Two started on 1 September 1939, 10 months after Kristallnacht.17 Hitler invaded Poland18 to regain territory, specifically the city Danzig, which the Nazis lost in the Treaty of Versailles.19 This was the major trigger to initiate war in Europe and on 3 September 1939, the British and French armies declared war on Germany, retaliating against Hitler’s actions.20 This severely impacted life in Germany for Jewish people, other minority groups, and German citizens.

The Jewish people were arrested, sent to concentration camps, ghettos, or both, and were extremely dehumanised by the Nazis. Nazi ideology claimed that Jewish people and other minority groups were considered less human, infectious, disgusting vermin, and extremely below the Aryan race in the Nazi racial hierarchy.21 These communities were targeted as they didn’t fit into Nazi ideology. Hitler was inspired by German Social Darwinism, which was based upon the concept of survival of the fittest and considered Judaism and other minority groups to be a race only worth extermination.22 Superior races, such as the Aryan race were to grow in power and repopulate the earth while the weaker races held no value and contaminated the population23 .

17 BBC Editors, ‘WW2 timeline: 20 important dates and milestones you need to know’, History Extra, 2022

https://www.historyextra.com/period/second-world-war/timeline-important-dates-ww2-exact/ (accessed on 13 August 2022).

18 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘World War II Timeline’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/world-war-ii-key-dates (accessed on 13 August 2022).

19 BBC Editors, ‘World War Two and Germany, 1939-1945’, Bitesize, (n.d.)

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z3h7bk7/revision/1 (accessed on 13 August 2022).

20 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘World War II Timeline’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/world-war-ii-key-dates (accessed on 13 August 2022).

21 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Victims of the Nazi Era: Nazi Racial Ideology’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/victims-of-the-nazi-era-nazi-racialideology (accessed on 13 August 2022).

22 A. Augustyn and The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Social Darwinism’, Britannica, (n.d.)

https://www.britannica.com/topic/social-Darwinism (accessed on 13 August 2022).

23 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Victims of the Nazi Era: Nazi Racial Ideology’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/victims-of-the-nazi-era-nazi-racialideology (accessed on 13 August 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 5

The Nazi racial hierarchy revolved around three main categories. At the top were the Aryans, typically with blonde (or light brown) hair, blue eyes, tall and of German blood.24 The women were expected to commit themselves to parenthood, to increase the superior race.25 Next was the Untermenschen, sub-humans, which consisted of the Slavic population and they were used as slave labour for Aryans.26 At the extreme bottom was the ‘life unworthy of life’ which consisted of Jewish people, Gypsies, Jehovah's Witnesses, homosexuals, disabled people, Soviet prisoners of war, African Germans, and Poles.27 Many of the ‘unworthy of life’ went into hiding at the start of the war. They were protected by German people who often risked their lives. If discovered, the German people were also brutally murdered for disrespecting Nazi rules.

In the early 1900s, discrimination against the Jews wasn’t considered Nazism, but rather antisemitism, which was already prominent in Germany. When Leopold was 5 years old and began school in 1908, he started experiencing discrimination because of his religious beliefs, but he was too young to understand why. This prejudice became worse when Leopold finished school and then later when Hitler came into power in 1933.28

Experiences of the Holocaust

On 9-10 November 1938, Kristallnacht, also known as the Night of Broken Glass, around 30,000 Jewish men, aged 16-60 were arrested and deported to concentration camps.29 Leopold was one of them. These pogroms through Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland involved Nazis, Hitler Youth and the Sturmabteilung shattering windows of Jewish homes

24 A. Low, Retroactive 2: Stage 5 History, Jacaranda, National Library of Australia, 2018, p.4c.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Victims of the Nazi Era: Nazi Racial Ideology’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/victims-of-the-nazi-era-nazi-racialideology (accessed on 13 August 2022).

28 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Woollahra, 23/8/2022.

29 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Kristallnacht’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2019 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kristallnacht (accessed on 29 July 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 6

and synagogues, lighting them on fire, arresting, abusing and murdering Jewish people. Around 7,500 Jewish shops and businesses were looted, and cemeteries were vandalised.30

Leopold and Paula’s brother, Allan Löw, and 11,000 other Jewish men were arrested and sent to Dachau, a concentration camp in Germany, during Kristallnacht.31 Leopold was 36 years old when his freedom was taken way 32 Dachau was established on March 22 1933, only 7 weeks after Hitler became Reich Chancellor.33 It was the longest-running concentration camp under the Nazi regime, operating the entire time Hitler was in power. Dachau was originally a munitions factory, located on the edge of the German town, Dachau, 16km northwest of Munich.34 The prisoner's camp was 5 acres, however, most of the Dachau concentration camp included SS training facilities and factories, which were an extra 20 acres large. Dachau was extremely overcrowded and lacked hygiene, clean water, and medical attention. The prisoners’ jobs included forced labour for the munition factory and expanding the camp.35 Well over 200,000 inmates were imprisoned in Dachau between 1933-1945. At least 28,000 people perished in the camp between January 1940 and May 1945. However, it is unknown how many passed between 1933-1939, and the number of unregistered prisoners. The entire number of people that perished in Dachau isn’t known.36 Around 30,000 survived, and Leopold was one of them.37

30 M. Berenbaum, ‘Kristallnacht’, Britannica, 2021 https://www.britannica.com/event/Kristallnacht (accessed on 29 July 2022).

31 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Dachau’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/dachau (accessed on 29 July 2022).

32 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

33 Kz-Gedenkstätte Dachau Editors, ‘Dachau Introduction’, Kz-Gedenkstaette, (n.d.) https://www.kzgedenkstaette-dachau.de/en/ (accessed on 20 August 2022).

34 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Dachau’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/dachau (accessed on 29 July 2022).

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 7

38 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Dachau’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/dachau (accessed on 29 July 2022).

39 ‘Memmingen to Dachau Concentration Camp’, Google Maps

https://www.google.com/maps/dir/Memmingen,+Germany/Dachau+Concentration+Camp+Memorial+Site,+Alt e+R%C3%B6merstra%C3%9Fe+75,+85221+Dachau,+Germany/@48.1310468,10.5260548,9.57z/data=!4m14! 4m13!1m5!1m1!1s0x479bf257cf20fa3f:0xcf8048c85d9627d8!2m2!1d10.1801883!2d47.9837999!1m5!1m1!1s 0x479e7a8ac83900a9:0x16794e4417b9a406!2m2!1d11.4682724!2d48.270124!3e2 (accessed on 20 August 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 8

Figure 2. Dachau Concentration Camp map 38

Figure 3. Distance from Memmingen to Dachau Concentration Camp 39

Leopold, Allan, and many other extended uncles were taken by truck40 to Dachau concentration camp which was 112 km east of Memmingen.41 He was a prisoner for eight weeks and worked as a labourer.42 At this time the Nazis hadn’t implemented the selection process, therefore, all the Jewish people were sent to work. Leopold hated talking about his time in Dachau and never specified what he did. Allan mentioned that the conditions were brutal, and the prisoners were killed by malnourishment and disease.43

Dachau was also known for its human testing and experiments. German doctors began performing medical tests on detainees in Dachau in 1942.44 High-altitude, hypothermia, and trials to examine desalination of saltwater were carried out by scientists from the German Experimental Institute for Aviation and Luftwaffe. These experiments were designed to optimise German bomber-pilots who crashed into cold seas.45 German researchers also tested the effectiveness of drugs for TB and malaria. These experiments led to death or lifelong disability of hundreds of Jewish people.46

Jewish and marginalised communities were brutally murdered in the Dachau concentration camp. Those who were deemed unfit to work, in the “selection process” were either murdered in the gas chamber or deported to Harthiem to be gassed in the killing centre near Linz, in Austria, where over 2,500 people from Dachau concentration camp were murdered.47

40 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Woollahra, 23/8/2022.

41 ‘Memmingen to Dachau Concentration Camp’, Google Maps https://www.google.com/maps/dir/Memmingen,+Germany/Dachau+Concentration+Camp+Memorial+Site,+Alt e+R%C3%B6merstra%C3%9Fe+75,+85221+Dachau,+Germany/@48.1310468,10.5260548,9.57z/data=!4m14! 4m13!1m5!1m1!1s0x479bf257cf20fa3f:0xcf8048c85d9627d8!2m2!1d10.1801883!2d47.9837999!1m5!1m1!1s 0x479e7a8ac83900a9:0x16794e4417b9a406!2m2!1d11.4682724!2d48.270124!3e2 (accessed on 20 August 2022).

42 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Woollahra, 23/8/2022.

43 Ibid.

44 National WW2 Museum Editors, ‘A Shocking Level of Brutality and Degradation: Dachau in Wartime’, National WWII Museum New Orleans, 2022 https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/shocking-levelbrutality-and-degradation-dachau-wartime (accessed on 20 August 2022).

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.

47 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Dachau’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/dachau (accessed on 20 August 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 9

Thousands of public mass slaughters by gunfire occurred, initially in the courtyard of the bunker and then on an SS shooting range that was created specifically for this purpose.48 Many of Leopold’s family perished in the gas chambers at Dachau.

Leopold managed to escape Germany eight weeks after Kristallnacht when he was 36 years old.50 At that time the Nazis wanted to get rid of the Jews in Europe but didn’t directly murder them until 1942. Instead, they were starved, and many Jewish people perished in this laborious process. Leopold was extremely malnourished and sick by the time he left Germany in January 1939.51 Peter, Leopold’s son said “Leopold was released from Dachau as visas for the whole family [including Paula and Allan] arrived. This meant he and Allan were freed and taken to Hamburg where the boat departed to come to Australia.”52

48 Ibid.

49 M.H.S, ‘The gas chamber at Dachau Concentration Camp, 1945,’ Minnesota Historical Society, (n.d.) https://www.mnhs.org/mgg/artifact/gas_chamber (accessed on 20 August 2022).

50 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Woollahra, 23/8/2022.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 10

Figure 4 The gas chamber at Dachau Concentration Camp 49

Final Solution

The ‘Final Solution to the Jewish Question’ refers to the organised, methodical, and efficient mass murder of the Jewish people living in Europe.53 This term makes it clear that this was a plan to annihilate these communities. The Nazis used a euphemism to hide the maliciousness of their intentions, dehumanising the Jewish people.54

The ‘Final Solution’ was decided on in late 1941, possibly around the same time as the invasion of the Soviet Union, but the exact date and reasoning are unknown.55 The Wannsee Conference in Berlin was a covert gathering hosted by SS General, Germany's Security Police chief and Heinrich Himmler's second in command, Reinhard Heydrich on January 20, 1942. SS officials and agencies of state reviewed the ‘Final Solution's’ ongoing implementation.56 The meeting wasn’t attended by the Wehrmacht, Hitler, or the other highest-ranking Nazi officials such as Heinrich Himmler, Hermann Göring, and Joseph Goebbels.57

Adolf Hitler launched and approved this systematic killing operation in 1941. The purpose of the Wannsee Conference was to inform and obtain the assistance of state agencies and other relevant individuals in the ‘Final Solution's’ execution. They didn’t debate the implementation but rather reviewed the execution of a legislative choice already decided by Hitler.58 They confirmed logistics and discussed the most efficient ways of killing the 11

53 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Final Solution: Overview’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2020 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/final-solution-overview (accessed on 20 August 2022).

54 Ibid.

55 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Final Solution: Overview’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2020 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/final-solution-overview (accessed on 20 August 2022).

56 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Wannsee Conference and The Final Solution’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/wannsee-conference-and-the-finalsolution (accessed on 20 August 2022).

57 Facing History Editors, ‘The Wannsee Conference’, Facing History and Ourselves, (n.d.) https://www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter-9/wannsee-conference (accessed on 20 August 2022).

58 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Wannsee Conference and The Final Solution’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/wannsee-conference-and-the-finalsolution (accessed on 20 August 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 11

million Jews in Europe which they aimed to exterminate.59 During the Wannsee conference, Heydrich declared that Jews will be sent to the East under extreme supervision for forced labour. Jews who were healthy enough to work were sent to build infrastructure. It was predicted that a considerable amount would die from brutal conditions. The survivors would be the strongest; and they must be properly dealt with since due to natural selection they would most likely produce the strongest Jews, preserving the Jewish communities.60

There is debate as to when the Nazis established the 'Final Solution'. The intentionalism theory states that Hitler always intended to achieve the 'Final Solution', it was always their plan to exterminate the entirety of Jews in Europe. The structuralism theory states that Hitler only decided in October 1941 when the Nazis were struggling to maintain recourses and the Soviet Union had not capitulated. The ghettos couldn't hold all the Jews and the Nazis had to murder them to relieve pressure on resources. The structuralism theory makes most sense as Leopold was able to leave Germany, as at the time they only wanted Jewish people gone, not necessarily exterminated. They only started mass extermination after they realised they were losing the battle.61

The Einsatzgruppen and the Third Reich created various killing centres, also known as death factories or extermination camps, to carry out the ‘Final Solution’. The Jewish prisoners and other targeted marginalised communities were taken into the gas chambers to be killed by poisonous Zyklon B gas62 or brutally shot by SS officers.63 2,700,000 were murdered at the

59 Facing History Editors, ‘The Wannsee Conference’, Facing History and Ourselves, (n.d.)

https://www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter-9/wannsee-conference (accessed on 20 August 2022).

60 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Wannsee Conference and The Final Solution’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.)

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/wannsee-conference-and-the-finalsolution (accessed on 20 August 2022).

61 Facing History Editors, ‘The Wannsee Conference’, Facing History and Ourselves, (n.d.)

https://www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter-9/wannsee-conference (accessed on 20 August 2022).

62 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘At The Killing Centers’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.)

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/at-the-killing-centers (accessed on 24 August 2022).

63 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Killing Centers: An Overview’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/killing-centers-an-overview (accessed on 20 August 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 12

extermination camps64 and the Nazis tried to cover this up by cremating the bodies or burning mass graves.65

Luckily, Leopold escaped Germany before the ‘Final Solution’ was implemented. My grandfather, Peter had said, “by 1942 most of Leopold’s family had left Germany. The family had migrated from Ichenhausen, a small village in Bavaria… but his great uncle Albert and wife Martha remained, and they and their children were exterminated”.66 In 1942 they were rounded up and sent to the town square where they were loaded on trucks to various death camps. All the non-Jews were cheering when they were finally deported and several of his extended family members died in the gas chambers as a result of the ‘Final Solution’.67

Liberation

The remaining concentration camps were liberated by the allied and Soviet forces, between 1944 and 1945.69 The United States army liberated Dachau on April 29, 1945. There were

64 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Final Solution: Overview’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2020

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/final-solution-overview (accessed on 20 August 2022).

65 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Killing Centers: An Overview’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/killing-centers-an-overview (accessed on 20 August 2022).

66 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Woollahra, 23/8/2022.

67 Ibid.

68 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Liberation of Nazi Camps’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/liberation-of-nazi-camps (accessed on 20 August 2022).

69 Ibid.

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 13

Figure 5 Liberation of Nazi Camps map 68

67,665 surviving prisoners, around 22,000 of them were Jewish.70 As the soldiers got closer to the camp, they discovered over 30 railway wagons packed with decaying bodies. The Nazis marched over 7,000 captives, predominantly Jews, through Dachau to Tegernsee, which was far to the south. Throughout the Death March, the Nazis killed all who couldn't keep walking and numerous perished from the cold, starvation, dehydration, or fatigue. US forces released the prisoners who were on the death march in May 1945.71

Post War

Leopold and Paula Kitzinger were able to immigrate to Australia as enemy aliens since they came from an enemy country when he was 36 years old. Around 77,000 other Jews had also left Germany or Austria in 1939.72 Paula’s brother, Joe, managed to get a visa to Australia, arriving in Canowindra, NSW in 1936. He was sponsored by his aunt. Leopold and Allan were able to escape from Dachau, as Joe sponsored them and their families to move to Australia.73 Australia was only giving out 5,000 visas/year74 - specifically for farming jobs.

70 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Timeline of Events - Liberation of Dachau’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://www.ushmm.org/learn/timeline-of-events/1942-1945/liberation-of-dachau (accessed on 20 August 2022).

71 Ibid.

72 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘German Jewish Refugees, 1933-1939’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/german-jewish-refugees-1933-1939 (accessed on 24 August 2022)

73 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

74 R. Gray, ‘The Holocaust through the lens of Australian Jewish refugees’, UNSW Sydney, 2020

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 14

Figure 6. The Ormonde Ship which they travelled to Australia on

They travelled on the Ormonde Ship, a dutch vessel, which left via Hamburg in late January 1939, sailed through the Mediterranean Sea and arrived in Sydney on 4 May 1939. On the ship, Leopold and Paula were advised by a priest to change their last name to Kitchener to fit into Australian society.75

Leopold and Paula stayed in Bondi for one week and then were sent to Chelsea Farms for two weeks, which was an area to train refugees into becoming farmers. They then lived in a small country town in NSW, Canowindra, and became market gardeners. They lived on the eastern edge of town and rented ten acres of land to create a farm.76

Even though they had fled from Germany they were considered enemy aliens. This meant that he wasn’t allowed to own a radio or camera, as they could be used to communicate with Nazis as German spies. They had to report to a police station once a week77. This stopped after 1942 when a town meeting was

https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/social-affairs/holocaust-through-lens-australian-jewish-refugees (accessed on 24 August 2022)

75 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

76 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

77 Ibid.

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 15

Figure 7 Leopold’s Immigration Documents

Figure 8 Leopold and Paula working at the farm in Canowindra

called to evict Leopold’s family as they were thought of as German enemies.78 However, the situation was explained and sorted out. Luckily, there was no antisemitism in the town. They became Australian Citizens in 1945.79

In 1946, Leopold, Paula and their son Peter moved to Sydney and Leopold became a travelling salesperson. He sold women’s clothes that he got from small clothes factories that were run by Jewish people. After a few years, his wife started making clothes for their

79

80 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022.

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 16

78 Ibid.

Ibid.

Figure 9 Leopold had to put advertisements in the newspapers to say he was born in Germany but wanted to become an Australian Citizen

Figure 10 Leopold’s application for Australian Citizenship

Figure 11. Paulette Fashions advertisement and photo

The Holocaust also had a severe impact on Leopold’s mental well-being. At first, he wouldn’t speak of the Holocaust and hid his religion even after he had moved to a safe country.81 He was afraid and vulnerable after what he had been through. He started opening up to his family about his experiences and exploring his family’s Jewish identity as he wanted to give his son the same Jewish traditions that he had as a child.82

Conclusion

Leopold’s story is one of resilience, perseverance, and bravery, despite the atrocious experiences that he went through. After exploring his testimony, I realised that we should never take freedom for granted as it is so easily stolen away. It’s troubling that a whole society of people enabled or ignored mass murder, and it has shown me the impacts of dictatorships and manipulation. Leopold was one person. Even though he starved and suffered terribly he was grateful to survive. There were over six million Jews who were not so lucky. Each one of them had a story, some of them have no one to tell it for them. I would like to dedicate this Essay to the silent stories of whole families that died with no survivors to tell their story.

81 Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 12/9/2019

82 Ibid.

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 17

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 12/9/2019

- Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Watsons Bay, 8/6/2022

- Peter Kitchener, interviewed by Elise Kitchener, Woollahra, 23/8/2022

Secondary Sources

- A. Augustyn and The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Social Darwinism’, Britannica, (n.d.) https://www.britannica.com/topic/social-Darwinism (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- A. Low, Retroactive 2: Stage 5 History, Jacaranda, National Library of Australia, 2018, p.4c.

- A.F.H, ‘Germany 1933: From Democracy to Dictatorship’, Anne Frank House, (n.d.),

https://www.annefrank.org/en/anne-frank/go-in-depth/germany-1933-democracydictatorship/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- BBC Editors, ‘World War Two and Germany, 1939-1945’, Bitesize, (n.d.)

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z3h7bk7/revision/1 (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- BBC Editors, ‘WW2 timeline: 20 important dates and milestones you need to know’, History Extra, 2022 https://www.historyextra.com/period/second-world-war/timelineimportant-dates-ww2-exact/ (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Facing History Editors, ‘The Wannsee Conference’, Facing History and Ourselves, (n.d.) https://www.facinghistory.org/holocaust-and-human-behavior/chapter9/wannsee-conference (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- J.V.L, ‘Memmingen’, Jewish Virtual Library, 2022, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/memmingen, (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Kz-Gedenkstätte Dachau Editors, ‘Dachau Introduction’, Kz-Gedenkstaette, (n.d.)

https://www.kz-gedenkstaette-dachau.de/en/ (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- M. Berenbaum, ‘Kristallnacht’, Britannica, 2021

https://www.britannica.com/event/Kristallnacht (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- M.H.S, ‘The gas chamber at Dachau Concentration Camp, 1945,’ Minnesota Historical Society, (n.d.)

https://www.mnhs.org/mgg/artifact/gas_chamber (accessed on 20 August 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 18

- National WW2 Museum Editors, ‘A Shocking Level of Brutality and Degradation: Dachau in Wartime’, National WWII Museum New Orleans, 2022

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/shocking-level-brutality-anddegradation-dachau-wartime (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- R. Gray, ‘The Holocaust through the lens of Australian Jewish refugees’, UNSW Sydney, 2020 https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/social-affairs/holocaust-throughlens-australian-jewish-refugees (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘At The Killing Centers’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/at-the-killingcenters (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Dachau’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/dachau (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Final Solution: Overview’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2020 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/final-solutionoverview (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘German Jewish Refugees, 1933-1939’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.)

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/german-jewish-refugees-19331939 (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Germany: Jewish Population in 1933’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.),

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/germany-jewish-population-in1933 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Killing Centers: An Overview’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/killing-centers-an-overview (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Kristallnacht’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2019 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kristallnacht (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Liberation of Nazi Camps’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021 https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/liberation-ofnazi-camps (accessed on 20 August 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 19

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘The Nuremburg Race Laws’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/thenuremberg-race-laws (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Timeline of Events - Liberation of Dachau’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.) https://www.ushmm.org/learn/timeline-ofevents/1942-1945/liberation-of-dachau (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Victims of the Nazi Era: Nazi Racial Ideology’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.)

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/victims-of-the-nazi-era-nazi-racialideology (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘Wannsee Conference and The Final Solution’ Holocaust Encyclopedia, (n.d.)

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/wannsee-conference-and-the-finalsolution (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ‘World War II Timeline’, Holocaust Encyclopedia, 2021

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/world-war-iikey-dates (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- ‘Memmingen to Dachau Concentration Camp’, Google Maps

https://www.google.com/maps/dir/Memmingen,+Germany/Dachau+Concentration+C amp+Memorial+Site,+Alte+R%C3%B6merstra%C3%9Fe+75,+85221+Dachau,+Ger many/@48.1310468,10.5260548,9.57z/data=!4m14!4m13!1m5!1m1!1s0x479bf257cf 20fa3f:0xcf8048c85d9627d8!2m2!1d10.1801883!2d47.9837999!1m5!1m1!1s0x479e 7a8ac83900a9:0x16794e4417b9a406!2m2!1d11.4682724!2d48.270124!3e2 (accessed on 20 August 2022).

Elise Kitchener, Drexler Memorial Essay, 2022 20