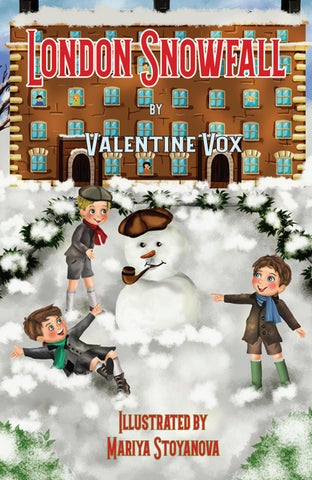

London Snowfall

By Valentine Vox

Despite the many Dickensian inspired cards showing quaint snow-covered London streets with barking dogs and jolly muffled people, it rarely snows at Christmas time in London. But, I can remember it snowing there one Christmas, and that was the great fall of 1947. Now, that was really Christmas. A Christmas like no other Christmas. A glorious, never-to-be-forgotten snow-covered, icicle dripping, turkey-smelling, cracker-pulling, carol-singing, joyous, white, white, Christmas.

The blanket of snow that covered the town that Christmas Day was a welcome sight for war-weary Londoners that, only a few years before, had suffered a reign of terror from

the same skies that now unleashed a peaceful, feathery snow. My mother woke me early that Christmas morning, telling me to look out the window behind my bed. I knelt up on my bed and my bleary eyes widened, as I looked through the frosted windowpanes to see the most beautiful snow-covered scene I could imagine. Overnight, the snow had fallen hard and heavy, covering my small familiar world in glorious white snow. It clung to the tall oak trees and the overgrown bushes like soft ice cream. It swirled against the

walls and covered the path to the garden gate that led to our road, which was now hidden beneath a pure white blanket. I could see that the Post Office, the Dairy and the Greengrocer’s shop across the road were all crusted in white. This was my first snow, my baptism into a winter wonderland of childhood dreams. Now, those Dickensian cards of Christmas past, Santa sledding on polar caps or miracles on a New York street all paled by comparison with this wondrous winter scene visable through the window of

my ithat winter of 1947.

my bedroom in that winter of 1947.

The presents that had been placed at the bottom of my bed on Christmas eve by my mother while I slept, I opened briskly and, as excited as I was to get them, especially the Hornby train set, my thoughts raced outside where a new white world awaited me. I washed and dressed quickly that morning and could already hear and smell the coal-crackling fire that my father had made in the living room. My mother was busy in the tiny, yellow kitchen preparing the bird and baking mince pies while singing along with the requested songs on “House Wives’ Choice” that came from the radio on top of the oak cabinet. After a porridge breakfast heavily ladled with golden syrup, I hastily ventured out into the new white world wearing my shiny Wellington boots, grey coat, and socks for gloves.

Out on the communal lawn that divided the big house and the red brick flats, Arthur and Clive were already having a snowball fight, while Frank was happily rolling over and over in the snow, moaning that he was dying on the Russian front. Soon, we mustered ourselves to engage in some organized mischief with this new, white ammunition and posted several snowballs through letterboxes around the flats. We then tried to write our names in the snow but were foiled by the cold that shrunk our small pencils. On the slope near the garden gate, which was now frozen because of a dripping pipe, we made a slide and took turns to see how long and fast we could endure the glassy surface. Then, we headed for our secret place, the Green Gate.

The Green Gate was where we could play and be anything we pleased. It was an abandoned, bombed house, with only the shell of its remains standing. Around the house was an overgrown garden full of bushes and trees that backed down to a railway where famous trains like the Flying Scotsman would zoom by and shake the ground.

Climbing through the long Green Gate that was covered in barbed wire to keep out trespassers, we walked a few paces through the crunching snow to the house in whose ruins we had aften played, sometimes engaging in war battles or Hollywood fights. These fierce

imaginary games often involved the breaking of windows, pottery or porcelain that was strewn about the ruins. But on that Christmas morning, we stopped in our tracks when we reached our playground of fantasy and destruction. The overnight snowfall had beautifully covered the ruins and thickly outlined the top of the remaining walls and swirled high against their base.their base. The snow-covered stairs that clung to one wall looked like a picture in an old Christmas card; all that was missing was a Scrooge-like figure dressed in a cap and nightshirt bearing a lit candle. We silently stood and stared at this

white, untouched scene.

“Do you think the manger looked like this?” Frank asked quietly.

“Let’s go back,” Clive said, “we shouldn’t mess this up.”

For some reason, we never questioned Clive and turned back from this wondrous, tranquil scene that we, for that moment, considered to be a Holy place. When we returned home, the snow was still falling and had already covered the tracks we had previously made around the house.

“Let’s make a snowman in the middle of the big lawn”, Arthur said, and we began rolling up snow like turf until we had made several large mounds. It took until noon before it was complete. Mr. Parsons gave us one of his old pipes, and Mrs Samson, a hat from her husband who had passed away that year. The finished snowman was tall and grand, and people around the flats opened their windows and peered down at this new, white stranger with his pipe and flat hat. Freddy Tompkins broke off an icicle and put it under the snowman’s nose, and Frank fell on the ground laughing as Arthur sang, “have yourself a snotty little Christmas”.

That afternoon, at the Christmas table, we wore paper hats and pulled crackers that banged and spat out cheap tiny trinkets. My father carved the turkey, and my sisters and cousin talked about their friends whose pipes had burst, which had forced them to spend Christmas with their religious aunt. The aunt insisted that they go to Church in the morning and in the evening of Christmas Day.

“Serves them right,” snapped my Uncle George, while scooping potatoes onto his plate from the green tureen.

“What, just because their pipes burst?” my Aunt Millie questioned sympathetically.

“No, because they have a religious Aunt,” he retorted without cracking a smile. Everyone began to laugh. My father shook with laughter and couldn’t put his fork to his

mouth he was laughing so hard. It wasn’t what my Uncle George said; it was the way in which he said it that would invariably make everyone laugh. His dry, cockney humour always caught you by surprise, and was downright funny.

While eating dinner, my Mother recalled her childhood Christmases, prompting the adults to reminisce of former days, always and beginning with the phrase “do you remember”.

During the second helping of turkey, my uncle George suddenly sat bolt upright and looked over my aunt’s shoulder towards the window.

‘Ere, who’s that old gal looking through the window”, he asked in a concerned manner. Everyone stopped eating and looked towards the window, wondering what stranger would dare peek through our window on Christmas day or, any day for that matter. There was no one there, but in that moment, while my aunt looked towards the window, my Uncle George swiftly shovelled some meat from her plate to his, and without missing a beat, began eating it.

“Oh, George,” she said, realizing what he had done,

“You’ve taken some of my meat.”

“You don’t need it,” he said, still eating.

“What do you mean, I don’t need it?”

“You’re getting too fat,” he said, still filling his mouth with turkey.

Now there were tears of laughter running down my mother’s and father’s faces as

my slender petite aunt, argued comically with my jolly round uncle George, who unashamedly continued to eat her portion of turkey.

After dinner, we sat by the roaring fire, where my mother and aunt had glasses of sherry, and my father and uncle had brown beer. I had a glass of Tizer, cracked open walnuts, and lay on the floor reading the Radio Fun Annual that was a Christmas present from my eldest sister. The meccano set from my parents and the toy soldiers from my Aunt and Uncle I had merged together to form a fortress under the small table near the window. The room was decorated with hand-made paper chains, and tinsel hung from the lampshades and gas brackets; it was warm and cosy and smelled of coal and sherry. By four o’clock, the daylight began to fade, and my father turned on the lights that he had proudly put outside the tall bay windows, which had become the talk of the neighbourhood. This was only two years after the blackout, and Christmas lights were only seen at the fashionable West e stores. The lights were not really Christmas lights but a flashing “V” for victory sign that my father had made at the end of the war for the company where he worked. As it became dark, the curtains were drawn, and my mother needed no prompting to play the upright piano. Together, we sang carols and London songs such as “Lambert Walk” and “Maybe It’s Because I’m a Londoner”.

In the evening, we went for a walk through the snow-covered streets. My mother and aunt walked arm-in-arm ahead of my father and uncle discussed post-war conditions, ration books and Winston Churchill. My sisters and cousins lagged behind, and I made snowballs and threw them at the lampposts. Suddenly, my mother screamed loudly, and we all ran towards her. She had slipped on the ice and landed on her rear end.

She was sitting upright in the snow, her skirt and petticoat above her knees and her glasses hanging off one ear. In this undignified position, she let out such a raucous laugh that it echoed down the white, gas-lit street. My uncle and father laughingly bent over to help her up, but both men lost their balance on the icy surface and fell on top of my mother “Blimey”, my mother cried from underneath them, “I don’t mind falling on me bum, but

now I’m going to be squashed to death”.

Amid the laughter that followed, it was difficult to say how long it was before everyone managed to get on their feet. My sister Pat had laughed so hard she had an unmentionable accident and had to run on ahead with the key to the house. When we got back to the house, my mother changed her nylons that she had laddered during the fall, and my uncle and father restored the smouldering fire with some coal from the cellar. Later that evening, after cups of hot tea, it was time to say our goodbyes, and we walked to the bus stop and waited for the number 41, which would take my uncle, aunt and cousins back to Ilford. When the bus came, we said our farewells and then walked back up the hill towards the house. The snow was still crunchy but had now turned grey and dirty, as the day had worn on.

That night, as I fell asleep, I added a new request to my prayers: that it snow again the next morning so I could relive this day all over again. Although my prayers were unanswered and the snow quickly disappeared by the evening of the following day, I do live this day over and over again, as each year in December, I remember with fondness my greatest Christmas of all, when it snowed on old London town in the winter of 1947.

About the author.

Valentine Vox is an established non-fiction author with several books to his credit.

London Snowfall, a childhood memory of a Christmas in London, is his first short story.

For more infomation about the author visit wikapedia page at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valentine_Vox

London Snowfall is a postwar childhood memory about an unprecedented snowfall that covered London in the 1940’s. “The blanket of snow that covered the town that Christmas day was a welcome sight for war-weary Londoners that only a few years before had suffered a reign of terror from the same skies that now unleashed a peaceful, feathery snow.”