Harrison

Harrison

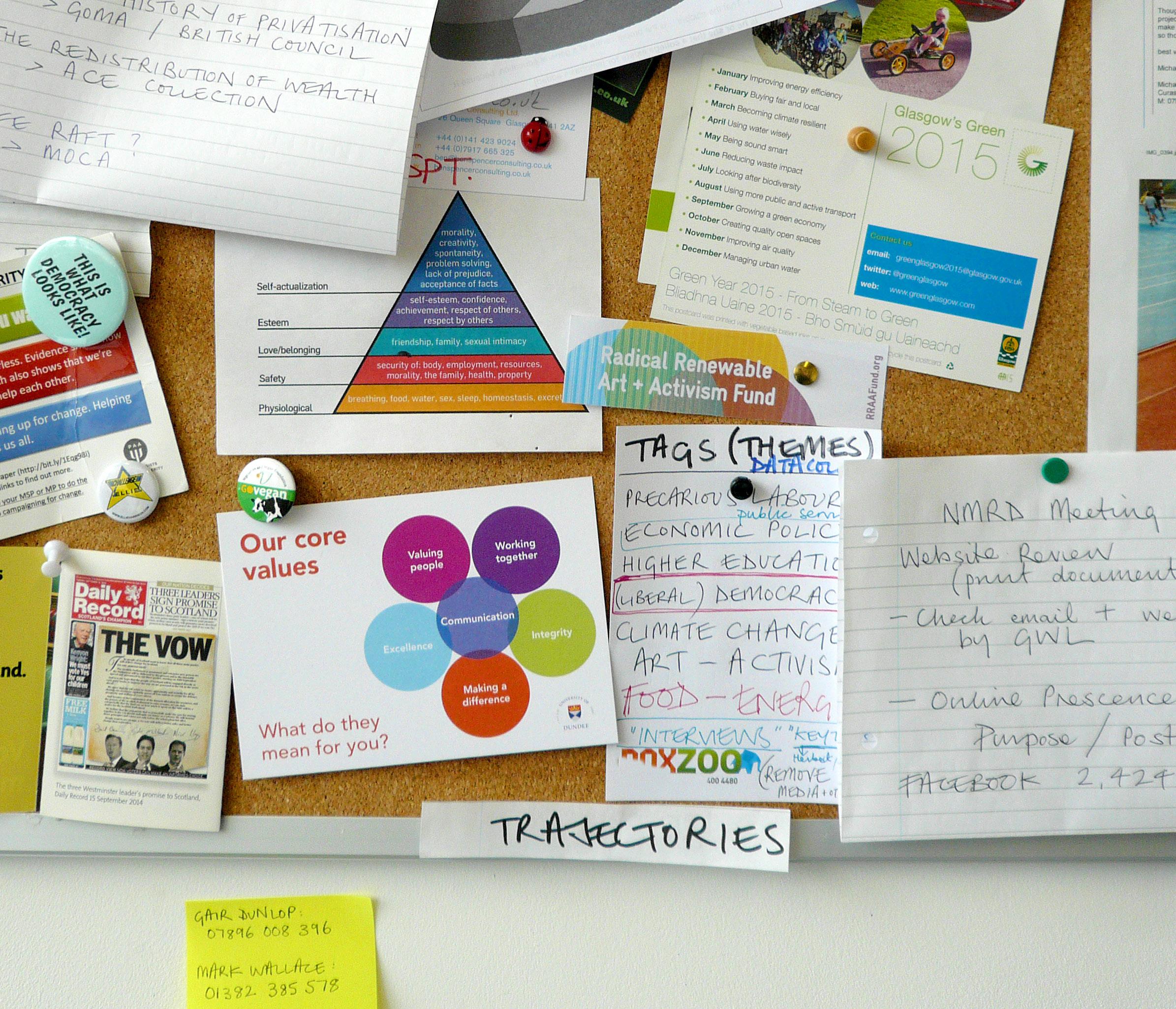

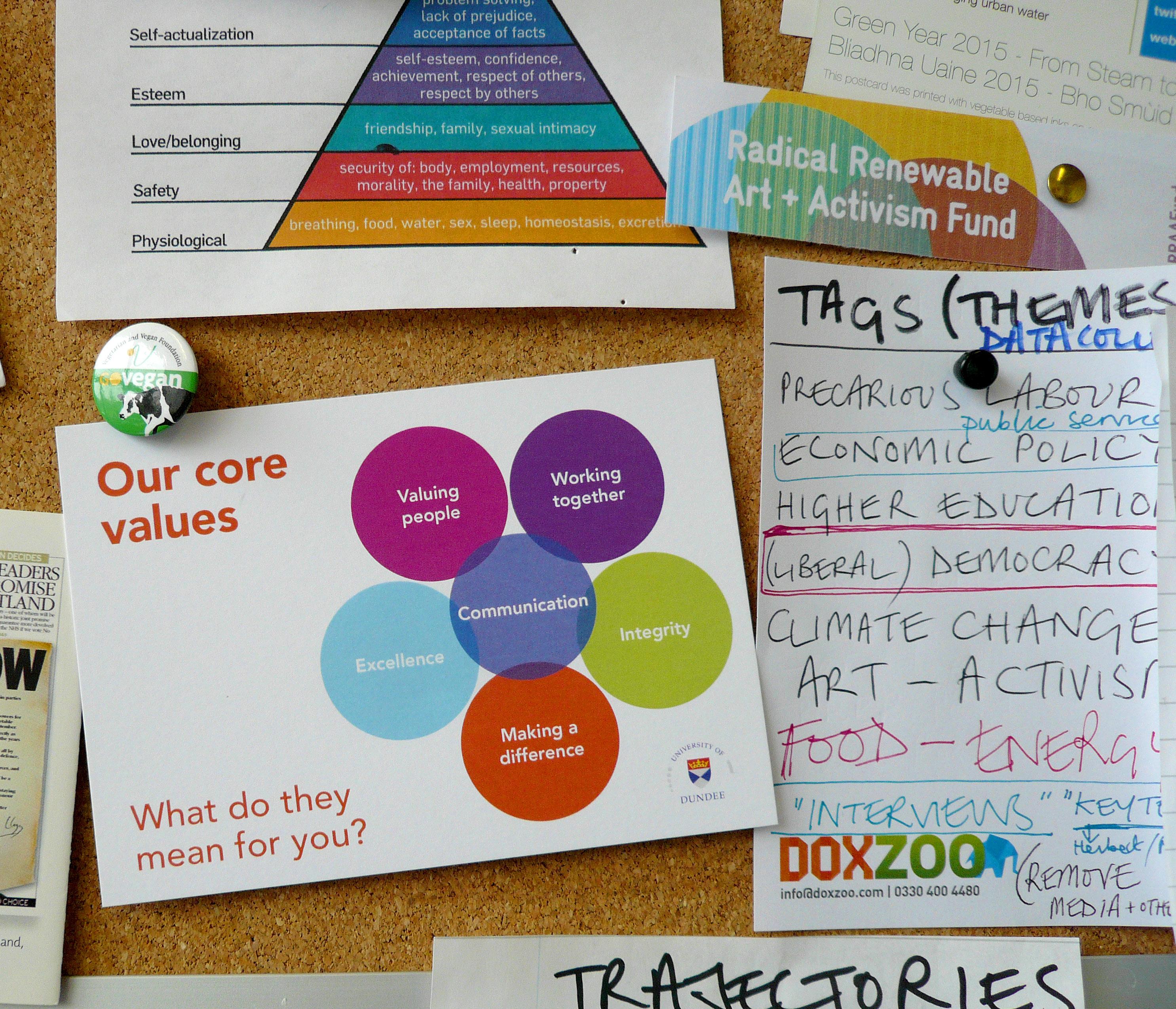

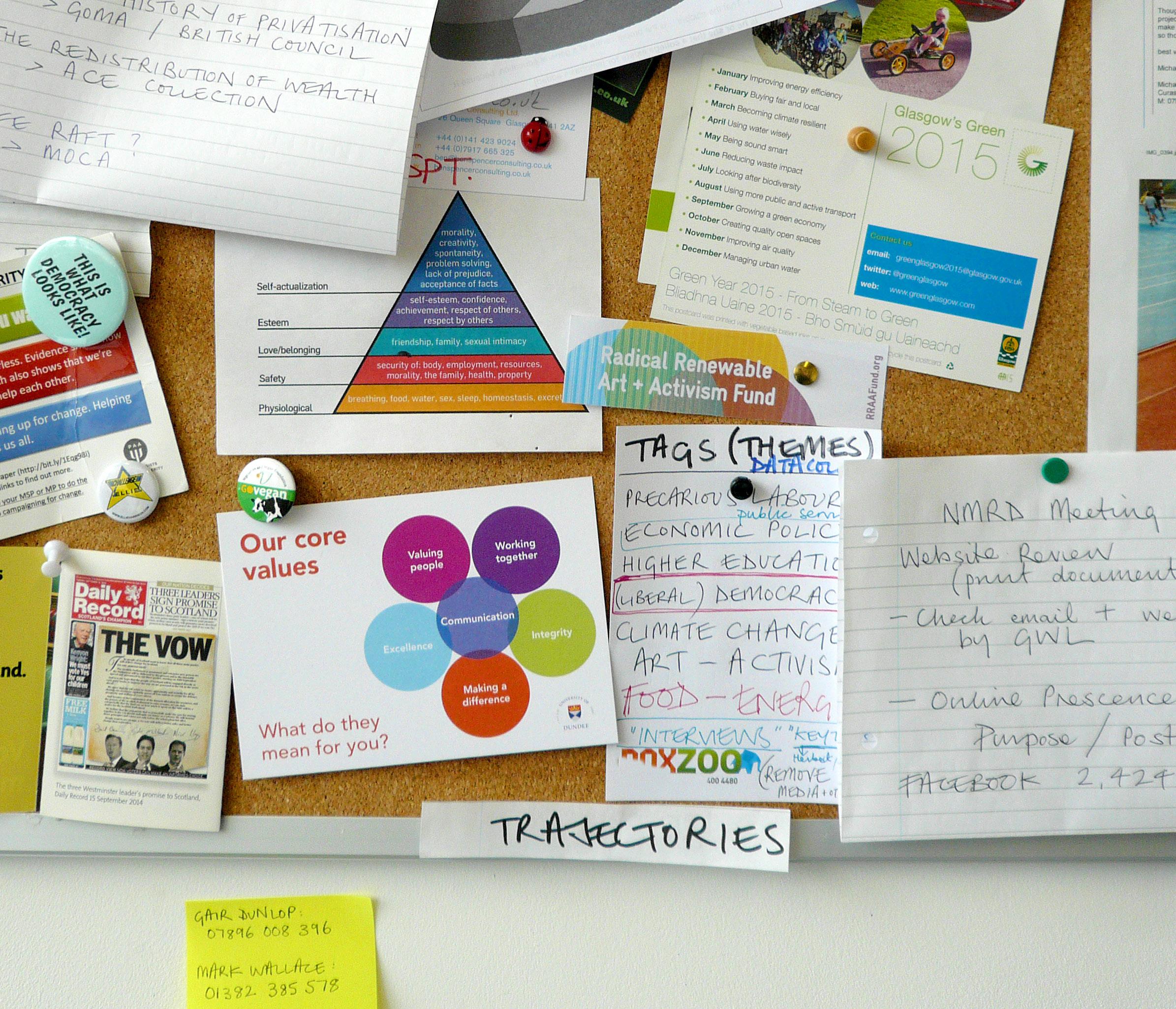

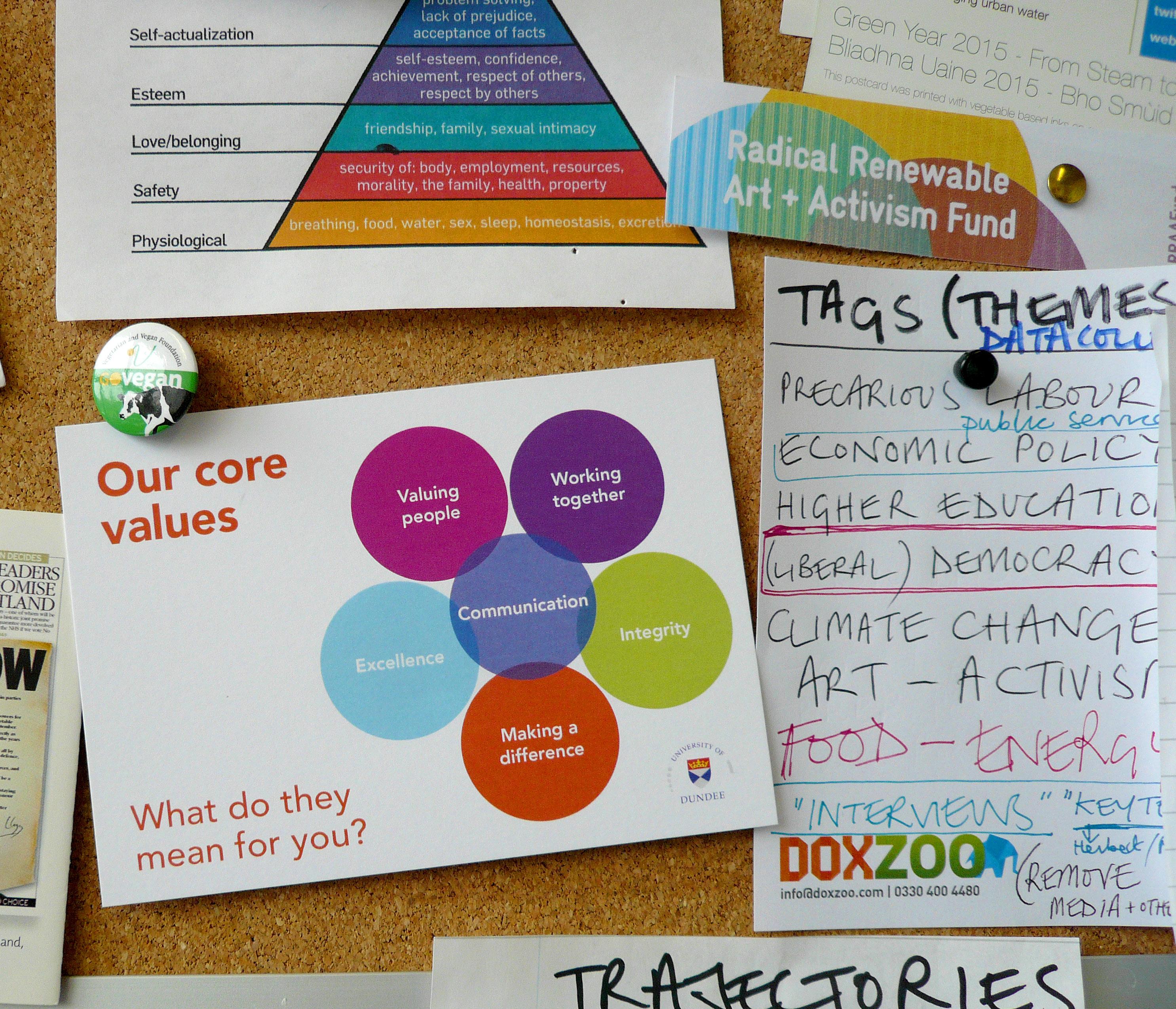

Cover Illustration: Close-up of the pinboard in my studio in Glasgow in 2016, showing a postcard illustrating the University of Dundee’s five “core values” as defined in 2012 as part of Transformation: The New Vision for our University The values are: valuing people, working together, integrity, making a difference and excellence. They are shown linked together in centre by communication (UoD, 2012)

Ellie Harrison

This text was written during the first few months of The Glasgow Effect – a “research project” for which I am refusing to leave the city where I have lived since September 2008, for a whole calendar year (1 January – 31 December 2016). To reduce my carbon footprint and my expenses even further, I am also attempting not to travel in any vehicles (other than my bike) until 2017.

Devised in summer 2015 in order to fulfil one of the criteria* of my three-and-a-half year “probation” for my lecturing post at the university, The Glasgow Effect (which was “successful” in receiving a £15,000 grant from Creative Scotland ) aimed to expose and challenge the contradictions which I have observed, experienced and been guilty of myself since taking up my first permanent lecturing post on April Fools’ Day 2013.

By exploiting the core contradiction in my own work-life (that I don’t live in the city where I teach), The Glasgow Effect made physical the invisible tensions which are experienced by colleagues across academia between their teaching and research. These are tensions which, as the project has already highlighted ( Vidinova, 2016), are caused and exacerbated by the mechanisms used in Higher Education to finance, assess and account for research.

Using examples drawn from within the university where I work, this text aims to expose problems that are endemic across the Higher Education sector. It outlines some key actions we must work together to implement across our institutions, to resolve the contradictions that are preventing us from practising what we preach.

* I was required to “write and submit a significant research grant application to a research council or the EU (eg. FP7, Horizon 2020, ERC) or other funding body with relevance to discipline (eg. Leverhulme or Wellcome Trust) and gain positive feedback from all the referees prior to the end of probation. If the grant is not successful in being funded it should only be because of a lack of available funding rather than because the application falls short on quality.” (CASE, 2012, p. 4)

“The part that education plays in human life is so important...” (Woolf, 1938, p.32)

Writing during the Great Depression of the 1930s – a “postcrash” time with many parallels to our own (PCES, 2011) – Virginia Woolf presents a vision for a new type of college, which can use the power of education to help create a better world (see full quote in Appendix 1 on p.22). Central to this vision is a deep understanding that we can only create “an experimental college, an adventurous college... in which learning is sought for itself”, if we ensure that both students and staff have a shared set of values. Values which are embodied in every aspect of how the college is run: from the building it is housed in, to the way it is governed and the curriculum itself. (Woolf, 1938, p.32-33)

The study of universal human values “reveals some deep connections between seemingly different issues” (Crompton, 2010, p.5). There are many negative consequences to prioritising “extrinsic” values such as: “financial success, image and popularity” (Kasser, 2013) i.e. inflated staff salaries (NUS, 2013) and “league tables: Research Excellence Framework; National Student Survey; Employability statistics...” (anon., 2015a). Psychologist Tim Kasser explains:

“The scientific evidence... shows that people’s values bear consistent relationships with outcomes such as... well-being, the care with which they treat others, and the extent to which they live in an ecologically sustainable fashion.” (Kasser, 2013, p.9)

The more we prioritise “extrinsic” values, the “less happiness and life satisfaction” and “fewer pleasant emotions (like joy and contentment)” we have, and the more likely we are to behave in “manipulative and competitive” and “unethical and antisocial ways”. In contrast, the more we prioritise (and successfully pursue) “intrinsic” values such as: “selfacceptance, affiliation and community” i.e. integrity, valuing people and working together (UoD, 2012), the “happier and healthier” we are and the more likely to have “ecologically sustainable attitudes and behaviours.” (Kasser, 2013, p.9)

Whether it is the impacts of climate change (Klein, 2015), shifts in the global economy (Srnicek & Williams, 2015) or changes in government funding (BIS, 2015), it is clear that we too are going to have to “rebuild our college differently ” (Woolf, 1938, p.32) in order to meet the challenges of our changing world. These are challenges which Transformation: The New Vision for our University, defines as:

• promoting the sustainable use of global resources

• shaping the future through innovative design

• improving social, cultural and physical well-being (UoD, 2012)

Transformation, our university’s 25 year strategy published in 2012, also defines the five “core values” which should “underpin everything we do”: valuing people, working together, integrity, making a difference and excellence (see postcard in cover illustration).

This text draws on my own observations and experiences teaching at the art school over the last three years, in order to highlight an evident “split between theory and practice” (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985, p.8); what is best described as the “valueaction gap”, between what we say we believe in and how we choose to behave (Blake, 1999).

Much like artist Joseph Beuys’ Appeal for an Alternative published in 1979, this text demands that:

“... the lip service that [our universities] pay to the highest ideals of mankind becomes the real thing, and is no longer belied by the actual practices of our economic, political and cultural reality.” (Beuys, 1979, p.1b)

My aim is to demonstrate that we can only achieve our goals and ensure the “long term sustainability” (anon., 2015a) of our educational institutions – both environmentally and financially – by insisting that “intrinsic” values really are “at the heart of every action and every decision we take” (UoD, 2012).

In “difficult times” (anon., 2015a), it is important to refocus on what is really important. We must be honest about what might be unnecessary and “meaningless tasks” (Srnicek & Williams, 2015, p.2), and where we are overstretching ourselves by trying to do too much:

“The university cannot... become all to each; it cannot: serve the education of young adults, train future specialists, provide a conduit for research and scholarship...” (Rich, 1974, p.59)

To help us refocus we must go back to “the simplest and oldest principles on which higher learning” has been built. Principles which the pioneering American art school Black Mountain College, chose as its guiding force:

1. That the student... is the proper centre of a general education, because it is he or she that a college exists for.

2. That the [teachers], fit to face up to the student as the centre, have to be measured by what they do with what they know. (Black Mountain College, 1952, p.36)

With the students back in their rightful place, it becomes impossible to justify any activity at the art school, which does not make a difference to their learning experience or which does “nothing to nourish art” (Archer, 2000, p.112). Despite its many flaws (discussed below), the 2015 UK government’s Green Paper on Higher Education does at least identify one area where our operations can be simplified:

“We must also address the ‘industries’ that some institutions create around the REF [Research Excellence Framework] and the people who promote and encourage these behaviours. There are cases of universities running multiple ‘mock REFs’, bringing in external consultants and taking academics away from teaching and research [emphasis added]. These activities appear to be a significant driver of the cost... [to the Higher Education sector, estimated to be £232million for the 2014 REF].” (BIS, 2015, p.73)

Unfortunately, what the Green Paper suggests and what all of us in the Higher Education sector – students and teachers –must work together to oppose (McKnight, 2016), is adding another layer of unnecessary bureaucracy. As academic Stefan Collini explains:

“Institutions and individuals have been pressured and incentivised [by the REF] to give research priority over teaching. The Green Paper is right to identify the resulting patterns of behaviour as a problem, but, in suggesting that the TEF [Teaching Excellence Framework] will help to ‘rebalance’ things, it is acting like a doctor who first prescribes one kind of unnecessary medication (the REF) which produces undesirable side-effects [emphasis added], then triumphantly adds a second medication (the TEF) in an attempt to reduce them. It is possible, though implausible, that a university tyrannised by the REF and the TEF will be better than one tyrannised by the REF alone, but a simpler and more economical remedy suggests itself.” (Collini, 2016, p.36)

It is Stefan Collini’s “simpler and more economical remedy” which we must fight for. As the evidence shows, wasting more resources pursuing “extrinsic” values: creating “an ‘image’ to enhance league table rankings” (Neary & Beetham, 2015, p.90), will do nothing to “improv[e] social, cultural and physical well-being” (UoD, 2012) and enable us to achieve the healthy work-life balance where our values – excellence and integrity –can manifest.

“[The TEF] also seems pretty certain to produce more efforts by universities to make sure their NSS [National Student Survey] scores look good; more pressure on academics [emphasis added] to do whatever it takes to improve their institution’s overall TEF rating; and more league tables, more gaming of the system, and more disingenuous boasting by universities about being in the ‘top ten’ for this or that... What is it unlikely to produce? Better quality teaching.” (Collini, 2016, p.36)

• Support the National Union of Students’ call to “wreck the TEF” (Grove, 2016) by boycotting the 2017 National Student Survey (NSS) and Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) survey (NCAFC, 2016).

Evidence shows that everyone – from the poorest to the richest – benefits from greater equality (The Equality Trust, 2012). Indeed, inequality has “pernicious effects... eroding trust, increasing anxiety and illness and encouraging excessive consumption” (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2009), precisely the opposite of the “good society” we should be working towards (Ashwin, 2015, p.viii).

Despite this knowledge, inequality between staff in the Higher Education sector has been allowed to grow to record levels (UCU, 2016). Not only does this “lead to low staff morale” (Hall, 2014), but it renders our aspiration to “support and promote equality” (UoD, 2012) meaningless. It is everyone’s responsibility to challenge excessive pay (Pickett, 2016).

If you earn more than £160,000, you are in one of the top 1% of earners in the UK (Dorling, 2015, p.10). The “value-action gap” occurs when our managers earn such large sums of money (Denholm, 2016), that they become so disconnected from what it actually means to have an environmentally and economically sustainable lifestyle themselves, any attempt to “promot[e] the sustainable use of global resources” (UoD, 2012) is inherently flawed.

Illustrating the interconnectedness of many social and environmental problems Naomi Klein explains:

“... fighting inequality on every front and through multiple means must be understood as a central strategy in the battle against climate change.” (Klein, 2015, p.94)

• Support the campaign for a Living Wage (Swindon, 2012).

• Support Dundee University & Colleges Union’s Alternative Vision for the University which demands that:

“the University... commit to [a living wage and] a maximum wage. No one in the University should be paid more than 10 times the lowest full-time salary (currently £14,797p.a).” (DUCU, 2016)

Values are not something you can simply demand, but should rather be considered as “fruit” (Ozanne, 2016). It is only when you nurture and show respect for the roots of a tree (whether that’s looking after yourself or, in the case of the institution, your staff), that desirable outcomes (i.e. the fruit) will emerge. Unless you get the system / operations of an organisation right, you will never achieve your goals.

Platform London is an excellent example of a real values-based organisation. They are so aware of the need to embed their ethics and principles into every aspect of their operations in order to retain integrity, that they devised their own Socially Just Waging System. It aims to “recognis[e] different needs and backgrounds and support... people’s security and creativity” by removing hierarchies of pay. (Platform, 2005)

There are some visionary leaders in the business world as well, who have recognised how equality can benefit both financial and social prosperity. Dan Price, CEO of Gravity Payments in America decided to become “part of the solution to inequality” (CBS, 2015). He slashed his own salary from $1.1million to $70,000 so that he could increase the “emotional well-being” of his employees by paying everyone the same. The new non-hierarchical pay structure enables everyone to work together more effectively as “partners”:

“Like many other tech firms, employees are [also] given unlimited paid leave and meetings are optional, which [Price] believes... gives them the autonomy to achieve results.” (Rock, 2015, p.9)

“Impact” is a word which is about as much overused in the Higher Education sector as excellence (Bishop, 2012, p.268). However, there is one organisation which appreciates how you actually achieve it. Rather than blindly demanding that “impact” just happens, the appropriately named Impact Hub in Birmingham understands that this can only ever be a consequence of successfully pursuing their values: “openness, trust, transparency, humbleness, generosity, learning & passion” (Birmingham Impact Hub, 2014a). They believe:

“A better world is created through the combined accomplishments of compassionate, creative, and committed individuals focused on a common purpose.” (Birmingham Impact Hub, 2014a)

This is made possible by having “an influencer structure, not a management structure”, where anyone can “be proactive in making the community a better, fairer and more supportive place to be” provided they embody their shared values and “leave [their] ego at the door.” (Birmingham Impact Hub, 2014b)