The peak of an editorial discourse in a post-war architecture

The AR has always been considered as the mainstream British magazine of the establishment. Leading the architectural discourse of the UK, it shows a kind of resistance against modernism where local architectural tradition took long time to accept the European modern movement. AR will keep this role until the beginning of the ‘60, when the magazines will slowly go through a crise which brings to the end of AR as the main offcial platform of architectural profession in the UK.

During the post-war years, AR tried to give an idea of continuity, giving a generous attention to the visual aspect of its project. Important fgures like Nicolas Pevsner, James Richards, Gordon Cullen and Rayner Banham remained present and active in the ‘40s and early ‘50s. In that frame, James Richards played a key role in establishing a public discourse and providing a plurality of revisionism of the pre-war modernistic project. His main goal, together with a strong form of criticism, was to create a connection – also through a podcast for the BBC – between AR’s topics and the public opinion.

In those years the most interpretative categories coined in AR were Townscape, Subtopia and New Brutalism.

Townscape

Gordon Cullen is the main protagonist revisioning the postulates of the European modern ideas of urbanism. Key role in his approach was the new attention to the visual aspect of the urban environment and a critic to “functional cities”. Throughout his voice, AR started publishing a series of articles as a form of criticism with a strong visual approach. Cullen criticized the lack of tradition, showing a need to propose an alternative approach to urban design with a reintroduction of certain scenographic aspects, able to defne the quality of urban environment. In 1949, Cullen published a section called “Casebook” that infuenced the attention to the magazine to the visual culture.

The attempt was to portrait the genius loci of British urban environment through drawings, sketches and pictures, to provide a counterattack of massive social housing that were built in that time. A theoretical contribution to “Casebook” was given by Pevsner who declared the picturesque as a resource to refect on the quality of British life. During the townscape campaign, photography helped the campaing’s message to reach a wider public beyond the usual crabbed confnes of architectural discourse. During the nineteenth century the camera was very little used as an architectural campaigning weapon or as an instrument for reform. However, with the advent of Modernism in the late 1920s, the photography of

3

architecture became a more varied genre.4 It was in the AR that the new concern for the environment was at its most evident. This change of emphasis can largely be ascribed to Hubert de Cronin Hastings who assumed editorial control of the magazine in January 1928. From now on, not only would it become proselytizer-in-chief of Modernist architecture in Britain but also one of the harshest critics of insensitive design in town and country.

In concert with the AR’s assistant editor from 1935, James Richards, the artist John Piper toured the country to capture the qualities of the traditional city and careless interventions or neglected heritage. Through photography, Piper and Richards extended the framework of what could be considered architecture. The pub and music hall could now take their legitimate place as a quintessential part of the urban mixture, helping to form pleasingly picturesque compositions alongside more modern buildings. Piper was one of the frst movers in the AR’s campaign to ‘re-educate the eye’. In addition, the picturesque was also seen as a means by which Modernism could be rendered more palatable to a sceptical public. Irregular planning, variety, surprise and the felicitous conjunction of new and old were the keys to providing successful Townscape and the AR’s photography refected these attributes.5

It was during these post-war years that the contribution of journalist photographers reached new heights. The headings under which many of the photographs are fled refect Townscape’s preoccupations: hard landscape, signs, roads and markings, bollards, hazards, awnings and fags and so on. Criticised for its lack of concern with structure and psychology, Townscape was after all preeminently a visual movement and, consequently, heavily image dependent. Cullen’s method of presentation and his terminology of Townscape often mirrored that of photography with talk of composition, serial vision and focal points. His emphasis on the importance of juxtaposition also highlighted a device that had become important in the modernist photography of architecture since the 1930s with photographers making telling points through the inclusion of discordant or empathetic elements within the frame.

On the right:

(1) “Serial Visions” by G. Cullen, Casebook (1961)

4

4R. Elwall, “‘How to Like Everything’: Townscape and Photography”, The Journal of Architecture (2012), 671-672 5 ibid, 674

5

Subtopia

Five years later, Ian Nairn mastered the camera, taking most of the pictures for his celebrated “Outrage” issue of the AR, as well as with Cullen’s drawings. Although “Outrage” seems less revolutionary, Nairn’s lucidly provocative text, a confrontational graphic layout, and a generous number of well-chosen photographs alone, added up to an indictment of what he and James Richards called “Subtopia”: an environment lacking community life and urban quality. “Outrage” not only provokes in the reader a sense of anger and despair but also one of visual claustrophobia. Indistinct quality of some of the photographs only intensifying the prevailing air of gloom. The subsequent “CounterAttack Against Subtopia” followed a similar format with forty pages of photographs - many by Nairn - offering examples of how the environment could be improved.

It is not diffcult to sense Hastings’s hand at work in these two issues. Townscape continued to be his central preoccupation., while this type of subject matter remained largely the preserve of amateur photographers being published alongside the images of the best of contemporary architecture by the AR’s staff photographers such as Bill Toomey and Hugo de Burgh Galwey. It did also fnd a professional champion in Eric de Maré, a close friend of Cullen. It was largely through de Maré’s compelling imagery that the photography of Townscape took on a more

professional mien. With a strong feeling for texture, his photographs provided a freshness and vigour that empathised well with the simple, robust detailing and strength of character of the structures they were recording.

In this page:

(2) Cover of The Architectural Review’s special issue: “Counter-Attack against Subtopia” by Ian Nairn (January 1956)

6

New Brutalism

Rayner Banham, a PhD student of Pevsner, was at the beginning of his career when he started writing in AR at the beginning of the ‘50s as an assistant editor. When he joined the AR’s staff, he immediately became a dissonant voice to the idea of Townscape, proposing a shift in the editorial project of magazine. His fascination for the experience of the avantgarde, especially on technological research, was slowly inserted in AR. Banham was interested in the image of the idea of brutalism, leading him to create an iconography in AR that was strongly infuenced by his interest in Futurism.

Banham introduced important changes in the cultural project of AR, especially against the traditional, conservative approach of Cullen and Richards, constituting a moment of transition in the editorial project of AR as the offcial platform of British architectural panorama in postwar period.

A dark human manifesto

Questioning society and the role of architects

In March 1969 Reyner Banham co-authored with the editor Paul Barker, the geographer Peter Hall and the architect Cedric Price an anarchic article in New Society called “Non-Plan: An Experiment in Freedom”. They sought to apply bottom-up thinking to top-down planning policies, proposing “a precise and carefully observed experiment in non-planning’”6

The authors claimed the problem was that “there’s seldom any sort of check on whether the plan actually does what it was meant to do, and whether, if it does something different, this is for the better or for the worse’” Although “Non-plan” was a well-intentioned proposal to hand power back to the people and oust the state from the planning process.

Six months later Hubert de Cronin Hastings,owner and one of AR’s editors, launched his response: Manplan. An alternative approach to architectural journalism that also functioned as a humanist manifesto, focused not on buildings, but on people, and not as individuals, but as a society.

The AR was seeking for a restoration of the humanities in the ‘70s, providing a fresh vocation for Europeans. It determined a preparation for the new decade with a re-examination of the categories – health, welfare, education, housing, communications, industry, religion. The ambition was more than an analysis, but rather a redefnition of these categories “angled at achieving within the resources available what our

7

6R. Banham, P. Barker, P. Hall, C. Price, “Non-Plan: An Experiment in Freedom”, New Society (20 March 1969) pp. 435-443

society needs most rather than what will pay best”. 3 The AR was therefore trying to provide an operation to release energy, not to redeem debts or boost exports, fringe benefts that will do their own redeeming and boosting when the right kind of effervescence is generated, dispersing malaise.

The editorial project consisted of eight publications: the frst three have been published monthly from September to November 1969, while the next fve were published every other month from January to September 1970. This shift in the AR’s publication is announced in the issue n. 870 of AR, in August 1969 with a special article aiming to explain the reasons and the intents of the manifesto: a pictorial survey representing neither novelty nor innovation, but the crystallization of the priorities that the AR has been establishing over a long period of time.

Regretting Britain’s loss of infuence in the international context and with deep frustration with the state of the nation and with post-war architecture and planning, the AR intends to act within the discipline. This was possible by making a campaign aimed at “every architect whoever and wherever he is, indeed the whole building force, not to mention planners and politicians, and happens to be one for which architectural journalism can provide a platform”3. A journalism which “avoids the language of political

tracts. Instead, it surveys in pictoral form the art of the possible”3 and establishes a direct continuity with Townscape’s discourse, since it “offers no magic solution, represents neither novelty nor innovation, but the crystallization of the priorities the Review has been establishing over a long period of time”7

Its communication proposes an analysis of cases of architectural publications where a series of photos is organized sequentially to obtain a representation of the urban space through several frames, like the ones popularized in Townscape campaign. The magazine was highly designed as an object in its own right to make an impact and alarm readers unused to such pessimism in their architectural magazines and who must have themselves felt the frustration that Hastings was trying to portray, fnding none of the other usual magazine sections for relief.

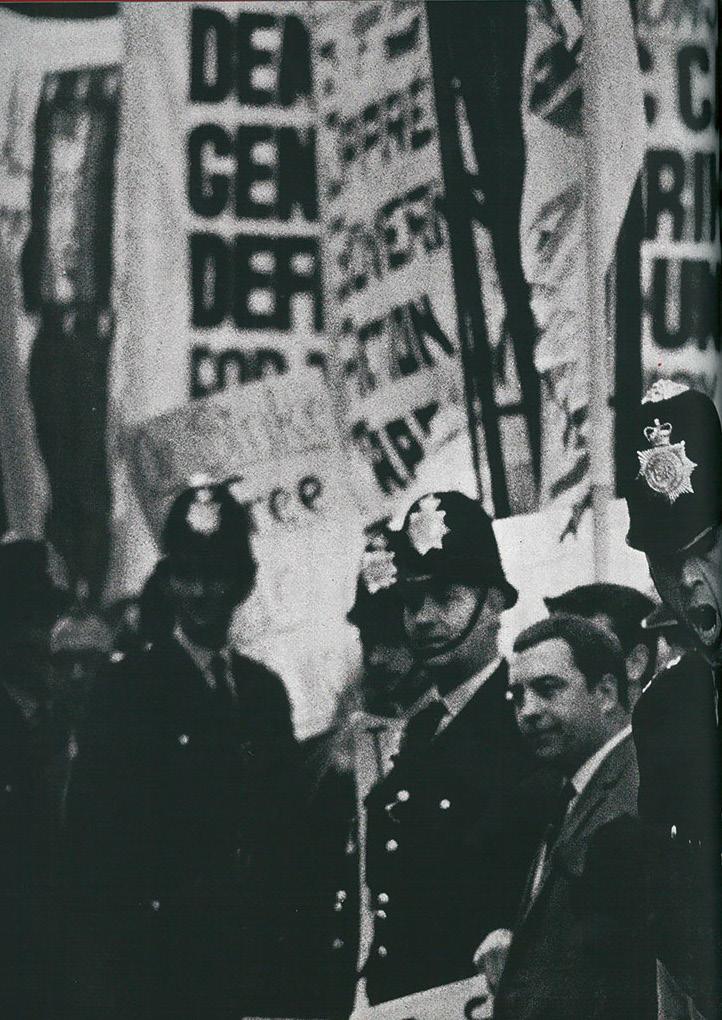

On the right:

(3) The Architectural Review, Manplan 1 (September 1969), p. 186 - 187.

870 (August 1969), 90.

8

7 J. M. Richards, N. Pevsner, H. de C. Hastings and H. Casson, The Architectural Review, n.

Photography by Patrick Ward.

9

Photography as a powerful method for a visual narrative

The graphich project

Townscape was one of the most powerful means by which architectural photography expanded its horizons not just in terms of subject matter but also technique. As a ceaseless experimenter, it is perhaps not surprising that Hastings should seek to go one step further by looking at the planned environment through the eyes not of professional photographers or even journalist amateurs, but through those of the emergent breed of professional photojournalists. The visceral imagery supplied by photographers such as Patrick Ward, Peter Baistow and Tony Ray-Jones excoriated the modern urban dystopia created by architects and planners in the Manplan project, which represented the ultimate alliance between townscape and photography.

Manplan was a departure from AR’s norm, not least the use of grainy reportage photography by leading photojournalists commissioned by the AR. The design was characterised by the use of fullpage images, multi-page spreads, guest editors, bold titles, Rockwell typeface forming a ribbon of text from page to page and by being printed using a matt black ink. Striking both by its design and by its depictions of buildings being populated and used by people, Manplan was to a degree controversial yet highlighted and explored many issues which remain acutely pertinent today.8

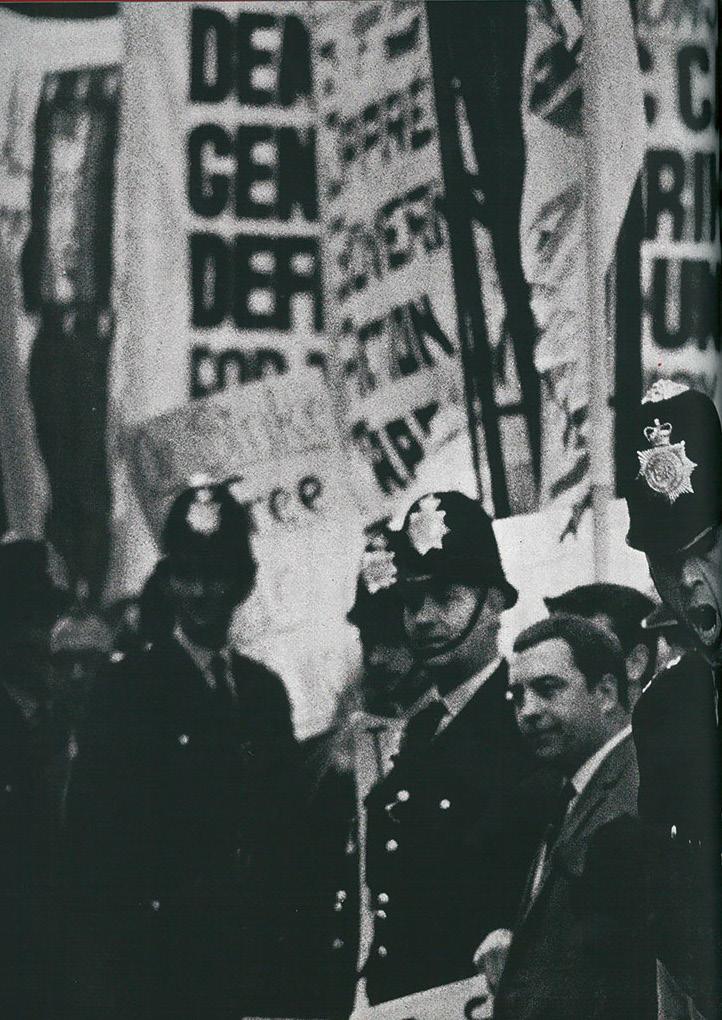

By taking the form of visual essays, the magazine depictes people and their activities in the harsh reality of everyday life: commuting, on a day out at a stately home, at work, at school, in a care home, in a nursery, shopping, protesting, waiting, queuing, smoking, standing, striking,staring, waiting.The black-and-white pictures taken by guest photojournalists, became the key element, ensuring the shocking power of the conveyed message. However, “the camera always lies” and just as once the AR contributed to the general acceptance of modern architecture by altering the conventions of architectural photography, here again it overturned the norms, forcing a dystopian view of England in the late sixties. The claustrophobic intensity of the images is stressed by the chosen views and the wide-angle lenses characteristic of street photography, which involve the observer in the image. The specially prepared matte black ink absorbs the light accentuating the dramatic aesthetics of the photographs and gives the reader a different tactile experience.

Graphic design also changes radically. Pictures spread along a full or double page, and even more as some sheets unfold in a wide format. Other times, just the opposite, a small photograph occupies the centre of the page, wrapped in a large black frame. According to Paulo Catrica, this layout “aimed to emphasize the visual autonomy of each photograph

8 J. Makepeace, “Manplan 1: Frustration”, RIBApix

On the left:

(4) The Architectural Review, Manplan 1 (September 1969), p. 188.

11

Photography by Patrick Ward.

within the theme, as well as strengthen its relations to the whole argument”9. All these harsh, dark images contrast with the pristine photographs of empty new buildings under the bright skies of the architecture photographers who regularly collaborated with the magazine, building AR’s visual reputation10. Their aim is to stir readers unaccustomed to this type of approach and pessimism in an architecture magazine.

The impact of the photographs is reinforced by the hard-hitting text and its articulation with the images. Presumably by Tim Rock or Hastings himself, it is limited to the bare minimum. A short excerpt opens each issue and a longer one closes it, pointing to “Conclusions”. Along the middle pages, only one or two lines in Rockwell’s serif typeface – sometimes over the images – crosses the pages with assertive, provocative phrases of uncompromising revolutionary conservatism. It is the text of a manifesto with sense of urgency, strength, persuasion, and claiming for a reaction. More than contextualizing the photographs, the text underlines their anger and anxiety. Word and images come together conveying a visual and linguistic despair11

The text therefore becomes the main thread of each issue, consisting of rhythmically structured continuous sentences, which formulate a linear discourse offering a univocal sequence to the reading. In parallel, a series

of explanatory notes or excerpts from the press feature in a smaller font size, without breaking the continuity of the main text.

The covers assume a sinister and disturbing graphics in a punk aesthetic with beheaded and dissected heads, in a macabre and fetishistic crescendo: a memento mori that culminates in the ffth issue, “Religion”, which cover shows a human skull trophy of a Brazilian tribe. Decapitated heads or skulls, occasionally adapted from anatomical drawings, and always eyeless, appeared on all eight Manplan issues, gradually becoming more macabre.

Manplan frst’s cover was of a phrenological head covered in words, including, prominently, ‘Frustration’ – the title of the issue itself – and a camera lens for his right eye.

This frst issue must have been a shock for subscribers. It is dark, both literally and fguratively, where the use of text is far less predominant than the black and white photography. Robert Elwall, historian of architectural photography, was fond of saying that they even devised a special matt-black ink to print the issues. The choice of the ink is in contrast with modern architecture’s preference for white space, making the tone dystopian. Several pages in ‘Frustration’ simply comprise a small black and white photograph in the centre of a sea of black with a simple statement.

9 P. Catrica, “The Architectural Press photographs at the core of the modern architecture paradigms, UK 1950/1970”, Modern Building Reuse: Documentation, Maintenance, Recovery and Renewal, Universidad do Minho Escola de Arquitectura, Guimarães (2014), p. 53.

10 I. Nairn, “Outrage”, Architectural Press, (1955), p. 366

11 R. Barthes, “Le message photographique”, op.cit., pp. 127, 134

On the right. Fom left to right, top to bottom:

(5) Cover of The Architectural Review, Manplan 1 (September 1969), (6) Cover of the Architectureal Review, Manplan 3 (November 1969),

(7) Cover of The Architectural Review, Manplan 5 (March 1970), (8) Cover of The Architectural Review, Manplan 6 (May 1970)

12

13

Patrick Ward was asked to document a month of frustration in Britain, that of congestion, queues, poverty, boredom, protests, inadequate buildings and damage to both the built and natural landscape. In the frst pages of the issue, over images of traffc we read: “Back to work the daily journey is a crude struggle crowd for the survival of the fttest. Each morning, cars, taxis and buses pour into the city from the suburbs, from the airport, from the Midlands, from the west, from the east, from the south”.

The resulting photos were taken on grainy 35mm flm rather than with a large format camera that the architectural press usually courted. Hence the frst edition’s title “Frustration” refecting the AR’s conclusion that, “the picture that emerges covers the whole spectrum of despair from inconvenience through exasperation to tragedy and, of course, farce”3. This was inspired by the September 1961 Architectural Design in which Roger Mayne went to Sheffeld to photograph everyday people going about their business with the new architecture forming the backdrop, a technique he started at Southam Street in the 1950s and used by the Smithsons to illustrate their Urban Reidentifcation grid at CIAM 9. Curiously, buildings are only explicitly addressed in the last pages, with views and layouts that deliberately reinforce their oppressiveness and desolation: a worm’s eye view of Centre Point Tower

in London, at Tottenham Court Road, or three-block residential East End with an elderly couple of Pearlies in the foreground.

The second issue, “Communications” is especially dedicated to means of transport and media.

Ian Berry was the guest photographer of the issue, who kept the informal style of the series. Quotes from government reports in a small font accompany larger banners of slogans marching over several pull-out leaves, the most striking of which is a seven-page long blue and silver drawing of the futuristic Advanced Passenger Train. Statistics punctuate the text.

Some proposals and drawings accompany a reappearance of optimism in the form of technology: containers, jumbo jets, cars in their parks, computers, silicon chips, bedside computers, wristwatch-walkietalkies, transmission by lasers, microwave radios, CCTV, picture telephones, cordless telephones, portable videotape recorders, pneumatic tubes and inventions as yet undreamed of, which “could enable twentieth century society to exchange its restless and often needless mobility for real contact man-to-man untrammeled by distance”.3

From the third issue “Town Workshop”, guest edited by Norman Foster and photographed by Tim StreetPorter, business almost returns to normal with a

14

focus on buildings, incorporating pages with a more conventional layout, and schemes and blueprints, schools (fourth issue), churches (ffth issue), hospitals (sixth issue), public equipment (seventh issue), housing (eighth issue), but the continuous text and full- page photography maintains the editorial coherence.

Manplan’s images are unparalleled in the history of AR but have precursors in Nigel Henderson’s street photography in Bethnal Green (1949-52), notably used by the Smithsons in the IX CIAM Urban ReIdentifcation Grid (1953), and some Architectural Design issues which resorted to photojournalism during the sixties.Namely Roger Mayne’s photographs in Park Hill housing estate, published in the special issue Sheffeld of September 1961, or the 1968 special issues Architecture of Democracy (August) Mobility (September) and Cities and Insurrection (December).2

However, Manplan also is the natural result of the AR’s editorial strategy based on photographic campaigns since the 1930s, in particular the Townscape movement for which the magazine had been active since the second post-war. Both Townscape and its subsequent Outrage already contained the seeds of the pedagogical, optical/cinematic and mobilizing components of Manplan.

The pedagogical approach emerged in the very frst Townscape issue “Visual Reeducation”12, aiming to Re-Educate the Eye. An optical model, in the visual way that the whole theory of Townscape was structured, according to the viewpoints of the moving person, meticulously represented in Gordon Cullen’s hand drawn sequential perspectives: the Serial Vision of the “Eye as Movie Camera”13. The mobilizing side of the campaigns which toughened over time: Outrage14, Counter-Attack against Subtopia15, Counter-Attack: the Next Stage in the Fight Against Subtopia16, etc.

12 The Architectural Review, n. 636, December 1949

13 G. Cullen, “Casebook: Serial Vision”, Townscape, London, The Architectural Press, 1961

14 The Architectural Review, n. 702, June 1955

15 The Architectural Review, n. 719, December 1956

16 The Architectural Review, n. 725, June 1957

Conclusion

While the discourse became harder and more politically engaged as it approached the sixties, reaching the pessimism of the Manplan’s humanist manifesto, the importance of photography and its edition was constantly determinant. Although based, at the beginning, on small unpretentious photographs, with an eminently practical side of recording good and bad practices, their layout treatment was often close to photojournalism.

As Robert Elwall points out, photography in the AR has always been a collaborative process since the 1930s – of selection, organization, cropping, and articulation with the text – a work “too important to be left to photographers alone”17

The best synthesis of Townscape’s photographic and cinematic project, which broke out in Manplan, can be found on the frst two covers, depicting human heads’ with an AICO lens Anastigmat 1:35 f = 35mm in the place of the eye: the “Eye as Movie Camera”.

Despite the great editorial innovation it represented, the experience of Manplan was commercially negative, causing protests from readers and the editorial team itself, being abandoned. In 1971, the editorial team was reorganized, Pevsner and J. M. Richards left, after 25 years with Hastings in the AR. Hastings, back then 69 years old, still launched his swansong campaign in 1971, Civilia, composed of

a series of photographic collages carefully prepared by Kenneth Browne, before leaving the magazine in 1973.2

Manplan is a ground-breaking and controversial example of architecture photojournalism: a striking testimony of narrative applied to sequential photography in one of the major European architecture magazines. In a time where the architectural press was exploring different types of media, the AR balances its communicative ability with a daring performativity and a mobilizing visual discourse aiming for a technological utopia: a renewal of human relationships through the introduction of new media.

On the right:

(9)

Review,

1 (September

17 Robert Elwall, Photography Takes Command: The camera and British architecture, 1890-1939, RIBA Heinz Gallery, 1994, p. 77

The Architectural

Manplan

1969), p. 223. Photography by Patrick Ward.

Bibliography

Iain Borden, “Imaging architecture: the uses of photography in the practice of architectural history”, The Journal of Architecture (2007), 57-77

Carlos Machado e Moura, Narrative Takes Command: Revisiting Manplan and Fotoromanzo, Photo Sequences in Arhitectural Magazines around 1970 (2017) 1-9

Robert Elwall, “‘How to Like Everything’: Townscape and Photography”, The Journal of Architecture (2012), 17:5, 671-689

Lorenzo Ciccarelli and Clare Melhuish, Post-war Architecture Between Italy and the UK. Exchanges and transcultural infuences (2022)

R. Banham, P. Barker, P. Hall, C. Price, “Non-Plan: An Experiment in Freedom”, New Society (20 March 1969) pp. 435-443

Paulo Catrica, “The Architectural Press photographs at the core of the modern architecture paradigms, UK 1950/1970”, Modern Building Reuse: Documentation, Maintenance, Recovery and Renewal, Universidad do Minho Escola de Arquitectura, Guimarães (2014), p. 53.

Ian Nairn, “Outrage”, Architectural Press, (1955), p. 366

Roland Barthes, “Le message photographique”, op.cit., pp. 127, 134

Gordon Cullen, “Casebook: Serial Vision”, Townscape, London, The Architectural Press, 1961

Beatriz Colomina, Clip, Stamp, Fold: The Radical Architecture of Little Magazines 196X to 197X, 2010, Actar, Barcelona

Torsten Schmiedeknecht, Andrew Peckham (eds), Modernism and the Professional Architecture Journal. Reporting, Editing and Reconstructing in PostWar Europe, London, Routledge, 2018.

Chapter 5: “Visual Sensibility and the Search for Form. The Architectural Review in po- stwar Britain”, Andrew Higgott pp. 93-111.

Beatriz Colomina, Architectural magazines (19001975), chronicles, manifestos, propaganda, Pamplona, T6 Ediciones 2012.

“NUÑO MARDONES FERNÁNDEZ DE VALDERRAMA. La crítica arquitectónica como génesis de la fractura entre planning y arquitectura en la Gran Bretaña de los años 50 y 60. El papel de la revista Architectural Review” pp. 221-228.

Hélène Janniere, Architectural periodicals in the 1960s and 1970s: Towards a Factual, Intellectual and Material History, Montreal, IRHA, 2008.

Joan Ockman and Edward Eigen, Architecture Culture, 1943-1968: A Documentary An- thology,Columbia Books of Architecture/Rizzoli,1993.

Véronique Patteeuw, Architecture, Writing and Criticism in the 1960s and 1970s, Archi- tectural Theory Review, 8th December 2010.

18

Atlas of issue

Sitography

AR December 1949, issue n. 636

AR June 1955, issue n. 702

AR December 1956, issue n. 719

AR June 1957, issue n. 725

AR August 1969, issue n. 870

AR September 1969, issue n. 871, Manplan 1 – Frustration

AR October 1969, issue n. 872, Manplan 2 – Society is Its Contacts

AR November 1969, issue n. 873, Manplan 3 – Town Workshop

AR January 1970, issue n. 875, Manplan 4 – The Continuing Community

AR March 1970, issue n. 877, Manplan 5 – Religion

AR May 1970, issue n. 879, Manplan 6 – Health & Welfare

AR July 1970, issue n. 881, Manplan 7 – Local Government

AR September 1970, issue n. 883, Manplan 8 – Housing

RIBApix, Manplan www.ribapix.com/manplan#

Steve Parnell, “Manplan: The Bravest Moment in Architectural Publishing”, The Architectural Review, (2014) www-architectural--review-com.translate.goog/archive/manplan-archive/manplan-the-bravest-moment-in-architectural-publishing?_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_ tl=it&_x_tr_hl=it&_x_tr_pto=sc

Lili Zarzycki, “AR In Pictures: Frustration”, The Architectural Review (2020) www.archi-tectural-review.com/archive/in-pictures/ ar-in-pictures-frustration

19