A SIGNIFICANT MEETING

SHEINBAUM’S VISIT TO WASHINGTON SIGNIFIES A NEW PHASE FOR THE 2026 WORLD CUP.

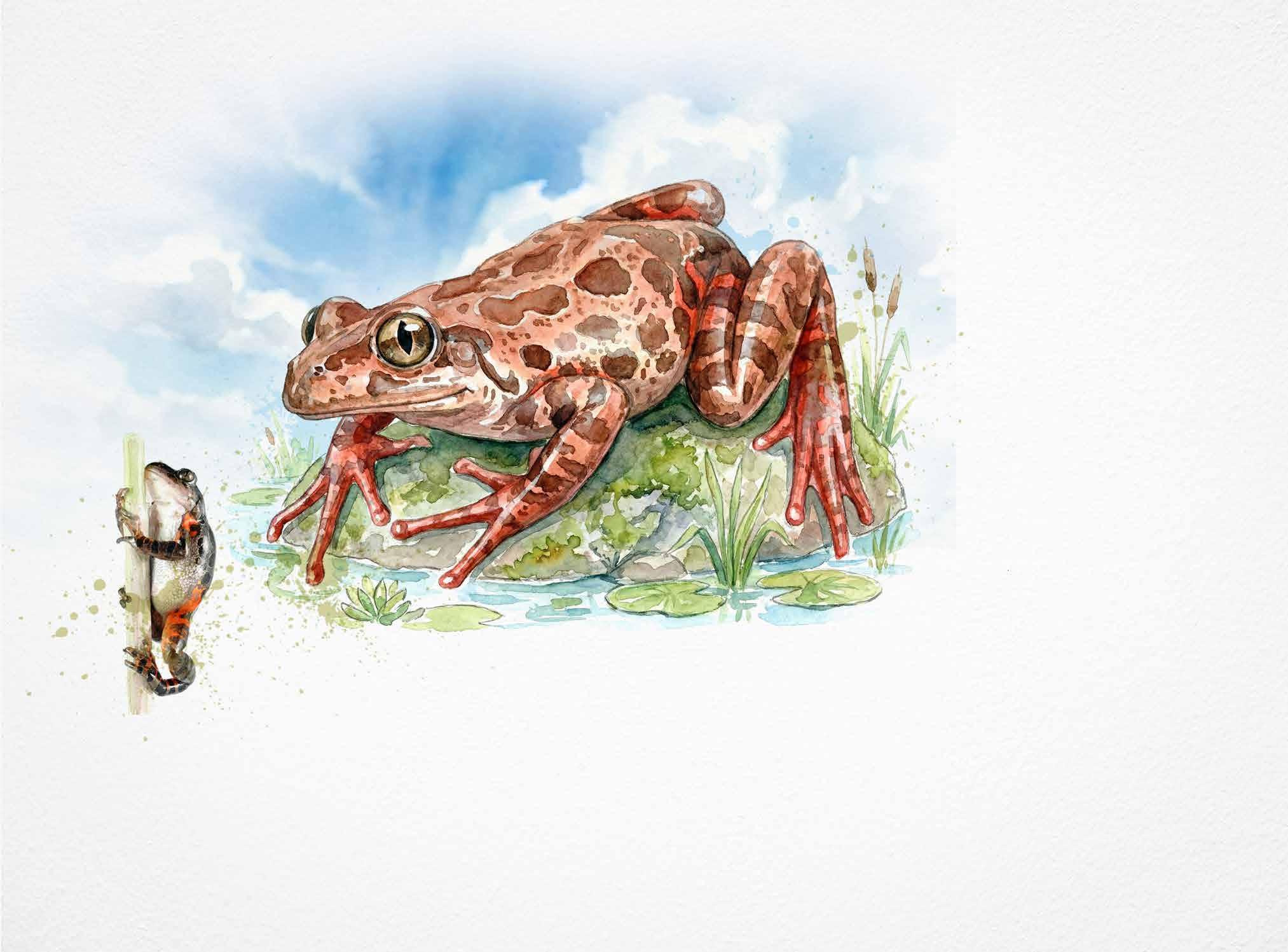

THE BINATIONAL FROG TEAM INCLUDED FAUNO, THE NATURE CONSERVANCY, SAN DIEGO NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE, ALONG WITH PRIVATE RANCHERS AND NUMEROUS CONSULTANTS.

OVER A SIX-YEAR PERIOD, OVER 23,000 EGGS WERE TRANSLOCATED FROM MEXICO TO THE UNITED STATES TO REESTABLISH EXTINCT POPULATIONS OF THE CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROGS.

OF THE 12 MICROPHONES DEPLOYED AROUND THE REINTRODUCTION PONDS IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, NINE RECORDED CALLS FROM THE CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROGS FOR THE FIRST TIME EARLIER THIS YEAR.

THE TEAM IS NOW FOCUSED ON EXPANDING THE CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED FROG TO ADDITIONAL RESTORATION AREAS THROUGHOUT SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA.

THE CALL OF THE FROGS

RECOVERING THE CALIFORNIA RED-LEGGED

FROG FROM DECADES OF DECLINE

Early this year, the first calling frogs were heard at two reestablished populations in Southern California.

BY: BRADFORD HOLLINGSWORTH ARTWORK: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

Aseven-year effort involving creative solutions, technological innovations, and hard work has started the recovery of one of California’s most imperiled amphibians. The team of conservation-minded biologists from the United States and Mexico set out to reverse the decades-long decline of the California red-legged frog, the largest native frog species in the western United States and one of the lead characters in Mark Twain’s Celebrated Jumping Frog short story.

The loss of biodiversity around the planet has taken on many forms, with extinction the ultimate outcome. Ceasing to exist doesn’t come easily, nor quickly, as life evolves to thrive, reproduce, and adapt. Yet humans are changing wild places faster than species can keep up. The possibility for thriving populations where loss seemed inevitable, changes the narrative. With a little help, declines in wildlife can be stalled, reversed, and the idea of extinction erased. For red-legged frogs, their recovery has just begun and the first efforts are proving successful.

The decline of amphibians worldwide has been tracked since 1990 and their status continues to deteriorate with over 40% of species threatened globally. While most species still persist, 37 have gone extinct. Overall, this biodiversity crisis is known as the Global Amphibian Decline, with the greatest concentration of problems occurring in the tropics of Central and South America, Africa, and Asia. Still, temperate regions haven’t escaped. In Southern California, 40% of native frogs are threatened with some like the California red-legged frog disappearing from more than 95% of their former range. The causes range from ecosystem transformation due to agricultural development and urbanization to the release of exotic species with no natural predators whose populations explode alongside their appetites. Frogs have had a tough time. Prior to extinction, there has been and still is erosion, loss, disease, and retraction.

Hundreds of individuals become only a few and eventually, stream by stream, they disappear.

The discovery of remnant populations in remote canyons of the Sierra San Pedro Mártir in northern Baja California provided the first possibility for recovery. Team partners from Fauno, a small family-run conservation non-profit located in Ensenada, Baja California, started the recovery by building resilience ponds adjacent to the few remaining frogs. The new ponds were quickly colonized and the red-legged frogs responded with more eggs, more tadpoles, and eventually a bounty of froglets. After only one year, a couple dozen frogs became hundreds. Genetic testing confirmed the Mexico populations were more similar to those frogs who once lived in Southern California, and the idea of translocation became a reality.

Rather than transport adult frogs along the 200 mile journey from the re-

covery ponds in Baja California to their new homes in Southern California, the team found their eggs to be more durable and numerous. Each female lays around 1,000 eggs clumped together in sticky individual gelatinous capsules. Surveyors of field biologists walk through the ponds and streams donning chest-high waders, slowly scanning underneath the water surface for egg masses. In any given year, the team can find 50 to 200 egg masses, amounting to 50,000 to 200,000 individual eggs. Prior to moving them, only a portion are harvested (about 5 to 20 masses depending on the total number detected).

Moving eggs from Mexico to the United States tested team logistics, permitting, and planning. With permissions from the Mexican government secured, the first translocation was planned for March 2020, the same month the COVID-19 pandemic hit. With international borders closing, a narrow window emerged and the first Yeti cooler full of frog eggs cleared inspectors at the Tecate port of entry. The first year of trials proved successful, requiring roles for each participant to solve problems and troubleshoot. The team could now focus on raising the frogs at their release sites in Southern California to adulthood, so they would eventually breed on their own. A single female, producing 1,000 fertilized eggs, could quickly colonize their new homes.

As years passed, successive translocations stocked the frog ponds and froglets began to grow into adults. By year four, periodic night surveys still had not heard calling males trying to lure females to their territory. Unlike some boisterous species, the California Red-legged Frog has a subtle call, hardly audible over the high-pitched chorus of treefrogs. A low baritone series of three to four honks, followed by a forceful grunt, would need a trained frog biologist to distinguish it from within the myriad nocturnal soundscape. Deploying a series of 12 microphones around the release ponds, the team went from periodic night visits to always listening. The microphones recorded from sundown to the early hours of the morning, producing tens of thousands of acoustic files. Thanks to the development of AI acoustic modeling, sorting out redlegged frog calls from owls, coyotes, and deafening treefrogs is faster and more efficient. On January 30, the machine model detected the first advertisement call of a translocated frog trying to breed on their own. By late March, males were heard calling into the night, some more aggressive than others. At microphone 11, two males producing countering honks and grunts, raised the attention to this location, presumably because a receptive female was nearby. The next week’s pond survey discovered the first egg mass, within a few feet of microphone 11. The recovery of the frogs has reached its first milestone — the first U.S.-born red-legged frogs in Southern California at our reintroduction sites — thanks to the friendships between two countries, conservation-minded biologists, and a species not ready to join the extinction list.

MEXICAN TALENT

REACHES OUTER SPACE

These young people reflect the future of Mexico—marked by intelligence, creativity, and humanism. They were accepted into the International Air and Space Program (IASP) 2025, an international educational initiative that took place at Space Center Houston in collaboration with NASA engineers. Only 50 students from around the world were selected to train for a week as astronauts in a real academic and operational environment.

a

DB – Please share with us the project you developed to

or

their emotions. I adapted this to space to determine, using sensors like a camera and physical sensors, the physical condition of an astronaut so that in case of any emergency, whether medical or emotional, mission control can respond quickly.

Imelda – I proposed developing a materials laboratory on the International Space Station, meaning that we could run something like a tensile test or a Charpy pendulum test, but

in space, to see how materials behave in zero gravity.

Juan – The project I presented is something I am developing to produce liquid telescopes — a method that would allow us to create this type of telescope more economically by using a liquid instead of a solid mirror.

DB – What do you see in these innovative proposals for space that could be reflected here on Earth in the countless social, environmental, political, and economic problems we face?

Sofía – I would also like to contribute here on Earth. We are thinking about developing our project specifically to implement it here. We believe there are many areas of opportunity where the technology we are developing can be applied, for example, for elderly people. A technological breakthrough can be implemented in different areas of life, so I would love to continue developing this with my team to improve people’s quality of life here on the planet while at the same time helping astronauts on their space missions.

Jorge – I think the core idea has always been that science and innovation can allow us to access better living conditions. Going back to my initial project idea — which was to promote space agriculture for food security situations — of course there are implications regarding who has access to this technology. Here on Earth there are food security challenges that involve the displacement of people and communities due to natural resources, and obviously an exospatial agriculture initiative brings political debate implications. I think innovation and openness across sectors of society would allow more people and more societies to access the new technologies being developed. I believe the push for innovation must go hand in hand with openness and democratization, and that people from developing countries should have access to these spaces to encourage such initiatives.

Pablo – Our project will first be implemented here on Earth in collaboration with a nursing home to test it with elderly people. I think it’s a project that can be applied in a very meaningful way, since we can help people who may really need it. I believe the technology we imagine for space shouldn’t wait to launch — it must first land here on Earth, where it can change lives today.

Imelda – I believe that, at the end of the day, space exploration isn’t just about leaving the planet — as people say, “escaping Earth.” On the contrary, I believe space exploration is what gives us the technology we have, and it is precisely by challenging ourselves in this way and discovering new technologies through space exploration that we later benefit here on Earth.

Juan – I think something very important is that space exploration is about breaking boundaries. Breaking boundaries that seem like our limits, proving to ourselves that we can go beyond what we imagine.

I feel that what’s important about these technologies we develop is that they help us learn more about our planet. Every time we look outward, it helps us discover how wonderful Earth is.

DB – What will be the future of this project?

And what would you like to see in the Mexican educational system and in access to knowledge, training, or resources so that projects like these could be developed on a larger scale, and people in less favorable conditions could also bring their ideas and projects to completion?

Sofía – We developed a holographic AI focused on emergencies. When an emergency occurs, this AI analyzes the information around it and

breaks it down to send it to Earth in a more effective way, making it easier to interpret and reducing response time. The plan is to continue developing it to implement it in nursing homes for emergencies when elderly people are alone so we can support them in some way. And in two years, as part of the award from this program, we will send a material to the International Space Station. I would love to see more incentives in education for girls and boys to get involved in science and technology because I believe there is still a large gap for girls in STEM. Even so, after this experience I realized that when little kids — girls or boys — see people achieving things out there, it motivates and inspires them tremendously.

Jorge – Today there have been major efforts from the state, structural changes at the parliamentary and legislative levels, but there is still a gap when it comes to infrastructure. There are international agreements so postgraduate and undergraduate students can conduct their research abroad, especially in engineering and the exact sciences, but there is a huge gap in infrastructure in our main basic education schools. It is precisely this lack of infrastructure that is needed to carry out all these new projects and initiatives. If we want students and teachers to face today’s problems, then we need infrastructure — computer equipment, laboratory equipment in schools, and the necessary resources for students to carry out their daily activities. I think that would be the starting point, and it should be at the core of our country’s public education policy.

Armando – I’m going to talk about a very specific example: we are in fields that society views as somewhat more difficult — engineering, medicine. Normally, when you tell people, they say, “Oh, that seems like a very difficult major, very complicated, because of all the math.” What I always say is that the hardest part of these fields is liking them — being passionate about them.

When you’re passionate about something, it becomes the easiest thing in the world. There will be days when you face difficulties. What I mean by this is that we should find ways to give young generations the resources to search for and begin exploring early in life the things that excite them — whether it’s art, engineering, or medicine.

So it’s about finding those resources to see how something you’re passionate about can become a professional career, and allowing children to engage early in something they love — something that will shape their whole lives.

Imelda – I think STEM education — everything related to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics — is essential for young people and children. Not only for technical skills, but also for developing critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, and creativity.

Something I would like to see in the education system is better-trained teachers prepared to teach these kinds of topics and guide these kinds of projects. Teachers and people who can engage with you, who can help create spaces where you can share knowledge, talk with others about your ideas and projects, and where it is a healthy environment.

Juan – I think it is very important to allow children to explore their interests. For example, extracurricular activities — because when you have a hobby or a sport you like, you start discovering what you enjoy, what you don’t, and what you are passionate about. And when you discover what you are passionate about, a path begins to reveal itself, and you gradually explore it. It is very important to expose people from a young age to a variety of experiences so they can understand what kinds of sectors, jobs, and fields exist in the world, and what each person’s passion might be.

Juan Guzmán

Imelda Gómez – Mechatronics

Jorge Rivera Martínez – Computer Systems Engineering –loves football.

Sofía García Chávez –Biosciences –likes to dance.

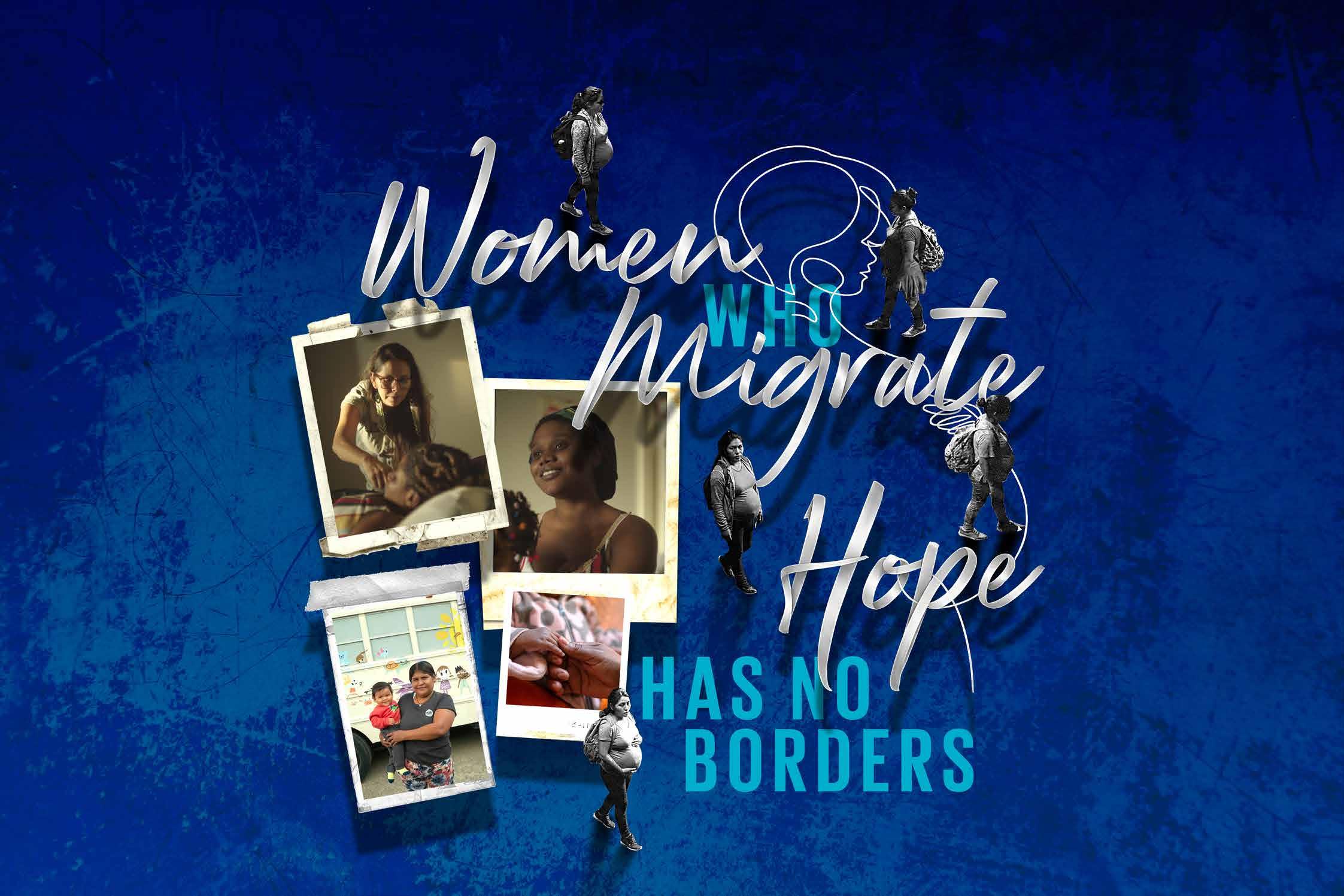

Fondo Semillas has launched the Women

Who Migrate campaign to support pregnant women in transit, a population facing growing vulnerability amid harsher U.S. migration policies.

Through decades of grassroots partnerships, the organization seeks to raise $25,000 by December 31, 2025, to fund essential care, visibility, and protection for migrant women and their families.

Fondo Semillas granted an interview to Heraldo USA, where, with the guidance of Ana Laura Godínez, head of the fundraising and mobilization area, we learned how a campaign launched on November 17 and running through December 31 seeks to raise awareness and funds to support pregnant women in transit. With 34 years of experience, Fondo Semillas finances networks of activists and grassroots groups that operate “on the ground,” often facing enormous challenges in delivering aid while also serving as the first line of care for thousands of people.

WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES THAT MIGRANT WOMEN FACE IN THE UNITED STATES AT A TIME WHEN DONALD TRUMP HAS INTENSIFIED HIS MIGRATION AGENDA?

What we are seeing along the migrant route is growing vulnerability that hits pregnant women and their families especially hard, and that reality has become impossible to ignore. Over the years, we have funded 717 organizations and benefited 1.3 million girls, women, and trans and intersex people. But even with all that experience, the scenario we face today concerns us deeply.

What alarms us most is that official numbers barely capture the problem. There is a large number of unreported cases, and even so, with what we can verify, we know that in 2023, there were nearly seven thousand pregnant women in transit through Mexico. That number alone shows the magnitude of the phenomenon, but what is most troubling is that almost half of them had no access to any health services.

“When a

pregnant woman

cannot

access basic services while in transit, and newborns are reprimanded or turned away from shelters, we are facing a crisis that cannot be ignored.”

WHY FUND THESE ORGANIZATIONS?

After so many years supporting grassroots groups, we can say that the most effective response comes from those who are in the field every day, without being told what to buy or what to do, without earmarked budgets. That accumulated experience is what helps us understand the scale of the problem and recognize that we are facing a humanitarian emergency that demands immediate attention.

The numbers we do know are already striking, and the ones we can’t see are likely even greater. That is why we keep insisting on bringing this conversation to the center: because we are talking about lives that depend on something as basic as a medical checkup that often never comes. The campaign can be found on the Global Giving site under Mothers Who Migrate for those wishing to support from the United States, and at semillas.org.

WHAT ARE THE GOALS OF WOMEN WHO MIGRATE?

We want to reach at least 500,000 pesos (approximately 25,000 dollars). We launched the campaign and have until December 31, 2025. With those resources, the organizations that reflect our mission will be able to continue reaching farther. We also hope to support other groups such as Parter ía, Medicinas Ancestrales, and 132, which are examples of larger organizations.

WHAT ARE YOUR FEELINGS ABOUT BEING AT HOME AGAIN?

I remember the case of a young woman who arrived in Mexico. She wanted to self-deport because she didn’t want to be forcibly removed, but she was pregnant. She found in these organizations the helping hand she desperately needed. She found a loving, caring space, a place where she felt as if she were back home.

WHICH WILL BE ONE OF THE MAIN CHALLENGES FOR FONDO SEMILLAS AND WOMEN WHO MIGRATE?

We know there is a global shortage of funding, but we are working to diversify these sources because these groups cannot be left without financial support; no one else would be standing up against these setbacks. We need this work to continue, and the economic side is crucial—because this is how they pay for a marker, internet, electricity, and the van that delivers supplies.

WHAT IS YOUR FINAL MESSAGE?

As long as these women exist and continue to need support, Fondo Semillas will do whatever it takes to remain that small arm that provides economic resources. And we hope that one day Fondo Semillas will no longer be needed because everything will be fine, but until then, we are here. Thank you. Hope has no borders when we build it collectively, and if you want to develop it collectively, Fondo Semillas

Climate diplomacy marked by Texan gas and geopolitical pressure

UNDER THE THE COP30 OF THE UNITED STATES FOSSIL SHADOW

The 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Belém arrived with the expectation that, at last, the world might adopt a clear roadmap to move away from fossil fuels. There were meaningful advances —on just transition, forests, gender, public participation, Indigenous rights, and adaptation— but on the most decisive point of all, the phase-out of oil, coal, and gas, the negotiations stalled. Although the United States was not formally present at the COP, its influence was felt like a heavy shadow: not through words, but through positions, backtracking, and silences.

THE NEW U.S. ENERGY STRATEGY: STEPPING BACKWARD TO AVOID LOSING GROUND

The United States faces a structural problem: it has fallen significantly behind in the global technological race across nearly every pillar of the energy transition—batteries, solar manufacturing, electric vehicles, critical minerals, and renewable infrastructure. Confronted with this disadvantage,

Mexico targets

43% clean electricity generation by 2035.

U.S. added

11.7

GW of new solar capacity in Q3 2025.

the Trump administration has chosen to double down on fossil dominance, expanding fracking, extraction, and gas exports, while aggressively attacking electric vehicles and renewables—sectors in which the U.S. does not currently lead.

This geopolitical shift emboldened fossil-fuel-producing countries that blocked the climate agreement in Belém, and allowed other governments—either dependent on Texan gas or politically aligned with Washington—to feel comfortable rejecting any explicit reference to a fossil-fuel phase-out. The United States didn’t need to be in the room; its absence spoke for it.

MEXICO: STRONG LEADERSHIP ON SEVERAL FRONTS, SILENCE ON THE MOST CRITICAL ONE

Unlike other countries, Mexico played an active and respected role in Belém. Alicia Bárcena was central in advancing the Just Transition Work Programme; Mexico helped deliver progress on forests, gender, participation, and finance; and it presented a highly credible, ambitious new NDC. The delegation worked with seriousness and strength.

But on the defining chapter—the progressive elimination of fossil fuels—the posture was different.

Mexico did not block the agreement, nor did it align itself with Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, or Russia. Yet it also did not support the Latin American bloc demanding an explicit “phase-out.” Mexico chose diplomatic silence—an absence that, in climate negotiations, effectively means withholding support from the strongest language.

blic defended the phase-out openly and forcefully, Mexico stayed on the sidelines. It neither joined the ambitious bloc nor the obstructive one, losing a chance to lead alongside Latin America on the world’s most consequential issue.

ENERGY REALITIES MATTER: MEXICO AS A PLATFORM FOR TEXAN GAS It must be said clearly: Mexico has become a key node in the export system of U.S. fossil gas. LNG terminals on Mexican coasts, cross-border pipelines, and megaprojects designed to supply Europe and Asia have created a real fossil interdependence.

This does not imply that Mexico acted under direct pressure from the United States. But it does help explain a posture of apparent “neutrality.” A country hosting the infrastructure of the new U.S. gas empire does not enter a plenary room with the same political freedom as others in the region.

A SETBACK WITH GLOBAL CONSEQUENCES

The science is unequivocal: without a fossil-fuel phase-out, there is no possible path to meeting the Paris Agreement. The consequences for the planet are catastrophic.

What happened in Belém shows that the domestic energy strategy of a single nation—driven by technological rivalry and a short-term fossil agenda—is now shaping, silently but powerfully, decisions that affect all of humanity.

While Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Costa Rica, Panama, and the Dominican Repu08/09

MONDAY / 12 / 15 / 2025 HERALDOUSA.

Belém made one thing clear: climate summits will advance only when countries choose to stand with the future rather than with the comfort of the present. Mexico still has the capacity—and the responsibility—to step out of the fossil shadow and help light the way forward. What remains is the political will to do so. The next chapter, for Mexico and for the world, depends on that choice.

BY: RAÚL GABRIEL BENET KEIL ARTWORK: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

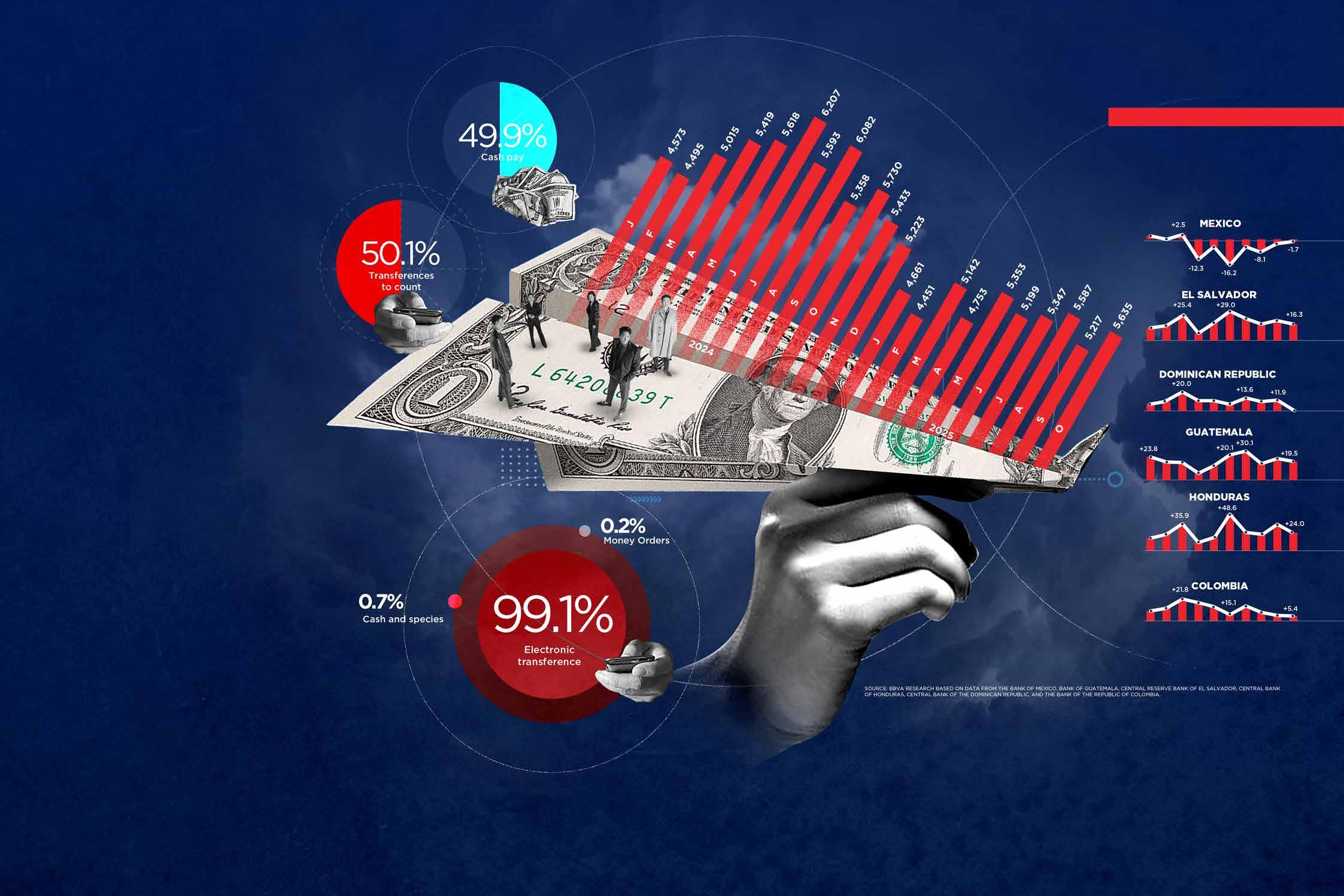

WHILE MEXICO EXPERIENCES SEVEN CONSECUTIVE MONTHS OF DECLINING REMITTANCES, COUNTRIES LIKE HONDURAS, GUATEMALA, AND EL SALVADOR ARE SEEING DOUBLE-DIGIT GROWTH. THE SLOWDOWN ISN’T A REGIONAL TREND BUT RESULTS FROM SPECIFIC ISSUES AFFECTING MEXICAN MIGRANTS IN THE U.S. LABOR MARKET, COMBINED WITH STRICTER IMMIGRATION POLICIES THAT LIMIT THEIR ECONOMIC INVOLVEMENT.

In October 2025, Mexico received $5.635 billion in remittances, the highest monthly total reported in the last year. However, this amount did not indicate strength, as it represented a –1.7% year-over-year decline, continuing the negative trend that started in April and lasted for seven consecutive months.

The year’s pattern has been irregular: February was the lowest point, and June experienced the sharpest decline, a 16.2% drop

As Mexico slows down, the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean are moving in the opposite direction. In October, remittances to Honduras increased by 24%, Guatemala by 19.5%, El Salvador by 16.3%, and Colombia by 5.4%; a month earlier, the Dominican Republic surprised with an 11.9% growth.

The contrast is clear: Mexico’s decline is not a regional trend but an exception in an area where remittances continue to be a vital part of the economy.

Traditional explanations—such as blaming U.S. immigration policies for the decline—are inadequate. “In fact, countries with high levels of undocumented migration, like Guatemala or Honduras, are seeing more remittances than ever. What makes Mexico different is a structural factor: the lower labor participation of new Mexican migrants in the U.S. economy over the past two years, which restricts their ability to send money compared to other Latin American groups that are actually growing,” said Carlos Serrano, chief economist at BBVA Mexico, in an interview with El Heraldo USA.

Adding to this is increased enforcement and migration pressure under the Trump administration, which worsens the decline by limiting labor mobility, creating uncertainty, and causing many Mexican migrants to be more cautious when sending money. The result is a steady decrease that could continue into 2026, although Mexico is still expected to receive nearly $60 billion in remittances—an essential lifeline for millions of households.

Despite the downturn, the remittance system is changing: for the first time in five years, more than half of electronic transfers are deposited directly into bank accounts (50.1%), while 49.9% are paid out in cash at counters. This change indicates increasing formalization and greater financial inclusion among recipient families, even amid a decline in overall flow.

MEXICODEFIESTHETREND

WIXÁRIKA CREATION AND HUICHOL ART

IN THE UNITED STATES AND AROUND THE

WORLD

I am originally from Jalisco, Mexico. I was born 44 years ago in an environment surrounded by artisan tradition. Since childhood, I lived among colors, yarn, beads, and geometric patterns—materials used to create Wixárika art.

Even though neither my mother nor my father formally taught me, curiosity led me to explore the tools and processes behind our pieces. At nine years old, I began watching how my parents, both artisans, created works filled with history and meaning. Back then, saw it as a game, a way to keep them company during their long workdays. Little by little, it became a passion.

MY BEGINNINGS

I remember my sister and me were always to-

gether, watching our parents work. Learning the art was never an obligation; I absorbed it naturally as part of daily life. My mom never said, “You have to learn this,” nor did my dad give me lessons on Wixárika techniques. Life itself taught me. It was natural and organic, as if the art flowed through our family’s veins. When was 15, I began traveling with my parents to different exhibitions and fairs, and I started to understand how important it was to showcase our crafts—not only in Mexico but abroad. On those trips, I learned a lot about how the work was sold and valued, and I realized that this art was not only a fundamental part of my life—it was also a way to share Huichol culture with the world. At 18, when I decided to become independent, I chose to follow this path on my own. That was when I realized I wanted to make crafts for a living and dedicate my life to preserving and sharing the beauty of Wixárika art. The first years were difficult. Once I moved out, everything was new. Even with my parents’ support and their network of contacts, taking the first step in such a big world was overwhelming. I didn’t know where to begin, but life—along with friends’ and family’s connections—opened doors. Slowly, I started placing my pieces in different spaces, first small ones, then larger ones. Through recommendations and word of mouth, I made my first sales at events and exhibitions, and that’s when my name began to circulate.

MY TIME IN THE UNITED STATES

Over the years, have been able to take my art to different countries around the world.

One of the most significant moments in my career came when I began exhibiting my work in the United States. I have been in cities like New York, Denver, Tucson, Arizona, and Santa Fe—places where Wixárika art is received with great admiration. In some spaces, it sparks reactions I had never seen before. People not only appreciate the aesthetic beauty of the pieces;

In Mexico there are 68 officially recognized indigenous peoples and at least 364 registered linguistic variants.

The last census of INEGI reports that 23.2 million people self-identify as indigenous people 19.4% of the national population

Between 2015 and 2019, 92,851 deportations to Mexico of speakers of an indigenous language were recorded With respect to the previous data, it means about 18,570 indigenous people repatriated per year, according to data from the Ministry of the Interior.

they understand the deep meaning behind each design. Wixárika art is not just color or form—it is history, spirituality, and a connection to the past. That is one reason my work has found such a special place in those markets. I remember the first times my pieces were purchased in those cities. Knowing that my work would not simply sit in a home, but in a space where it would be truly valued, filled me with indescribable satisfaction. In the United States, my pieces have been acquired by art collectors, gallery owners, artists, and anyone who understands the labor that goes into each bead, each stitch, each design. Creating for someone who truly appreciates the work is very different from selling to someone who buys simply because they can afford it.

Understanding this has helped me grow by allowing me to keep creating and developing my art beyond commercial expectations.

THE CHALLENGES AND OBSTACLES OF BEING AN ARTISAN

However, not everything has been easy. One of the biggest challenges we Wixárika artisans face is piracy. Some people copy our pieces and sell them at lower prices. Because these pieces are not authentic, they distort the value of our work. Sometimes I notice someone selling a piece similar to mine for much less, and I understand that not everyone knows how to recognize an authentic work or verify its origin.

Another challenge is government support— or the lack of it. Often, we have to manage on our own, without the economic backing necessary to take our art to other countries or essential spaces. The costs of travel, logistics, and participation in international events are often very high, and without financial support, it isn’t easy to keep advancing. What keeps me going, however, is the deep respect and admiration I have for our Wixárika culture. Every piece I create carries immense work and the soul of a people who have resisted for centuries. We are part of Mexico, yet we are often forgotten. In the United States—and even more surprisingly, in Mexico—some people don’t know we exist or what we represent. That is why every opportunity to share my work abroad becomes an opportunity to make our culture visible, to introduce people to the Wixáritari, and to fight for the preservation of our traditions.

When I traveled to Japan, people were surprised to learn that we exist—that our communities are still alive, that our languages are still spoken, and that we continue creating art just as we have for generations. Their reaction, their surprise, showed me how important it is not only to take our culture abroad but also to educate people here in Mexico about the richness we hold.

CREATIVE PROCESS

My work includes a wide range of pieces: small jewelry, large beaded decorations, nativity scenes, and animal figures. Each project is unique, yet all require the same dedication and love. I like to create what I feel in the moment and what flows naturally in my mind. Larger works—such as jaguar forms or beaded panels— take the most time, but they are also the ones that bring me the most excellent satisfaction when I finally see them completed.

12-13

12 / 15 / 2025

Today, everything seems to move faster. Artisan work reminds us that good things require time. There is no rush in the creation process, and there are no shortcuts. My work reflects our identity and history. Without Indigenous peoples, Mexico would not exist, and we all share the responsibility of preserving what has been handed down to us. hope my work continues to be displayed in the United States and in many more countries beyond our borders. Wixárika art and the Indigenous peoples of Mexico are still here—alive and creating, as we always have.

BY: ADRIANA BAUTISTA DE LA ROSA*

PHOTOART: IVAN BARRERA

Wixárika Master Artisan

Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo, broke paradigms and set a historic precedent by participating in the FIFA World Cup Draw, where she met for the first time with U.S. President Donald Trump and Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney. The three leaders appeared together on the same public stage: the iconic John F. Kennedy Center.

Here are the main highlights from the president’s trip to Washington, D.C. We start with the image that circulated worldwide: the moment FIFA president Gianni Infantino took a historic selfie with the three leaders of the World Cup host nations. The photo went viral within minutes, shared millions of times on social media, and instantly captured the scene forever.

Another unforgettable moment occurred when the U.S. president, during an interview, praised Sheinbaum’s leadership and work.

“Yes, your president is here, and she is doing an excellent job. She is a good woman and is doing an excellent job. It’s an honor to achieve all these records. You know Mexico and Canada are helping us set them. As you know, we already have a record in ticket sales,” Trump said.

While walking the red carpet, Trump reiterated that he maintained a strong relationship with both leaders: “We have a meeting scheduled for a moment after the event. We’ll talk today. We get along very

AT THE WORLD CUP DRAW MOMENTS TOP CLAUDIA SHEINBAUM’S

Claudia Sheinbaum created several historic moments during the FIFA World Cup Draw in Washington, D.C.—from the viral selfie with Trump and Carney to the emotional “¡Viva México!” that energized the Kennedy Center. The trilateral presence marked a milestone on the path to the 2026 World Cup and strengthened ties among the host nations.

well,” he said. Who could forget the moment cameras caught Trump and Sheinbaum chatting and laughing in the Kennedy Center stands, showing the warm connection between