10 minute read

LES MATHÉMATIQUES EN FRANÇAIS ET EN ANGLAIS

par Jérôme Giovendo Chef d’Établissement

La France a en mathématiques une tradition d’excellence, 14 médailles Fields sur 64 attribuées depuis la création de cette distinction équivalente au prix Nobel, ce qui la place en tête des nations, exaequo avec les États-Unis dont la population est beaucoup plus importante. La place des mathématiques dans le panthéon des matières scolaires, de l’avis des familles, et parmi les instruments de sélection, reste prépondérante dans notre pays. Et pourtant les résultats de la France dans les évaluations internationales, TIMSS et PISA sont catastrophiques. Pas dans notre école, grâce à nos méthodes, en particulier en primaire où l’acquisition des fondamentaux se fait sans compromettre le plaisir de la recherche. Nous vérifions chaque année en faisant passer à nos élèves de CM1 les questions publiées de TIMSS qu’ils y obtiennent de très bons résultats. Mais il y a tout de même matière à réflexion sur les méthodes pédagogiques et les contenus.

Advertisement

Un peu d’histoire de l’enseignement des mathématiques en France :

Dans les années 30, apparaît un groupe de mathématiciens qui, sous le nom fictif de Nicolas Bourbaki, entreprend la rédaction d’une présentation cohérente, et de facto totalement formelle, des mathématiques. Ces travaux et l’importance épistémologique qu’ils ont revêtue ont eu un impact très fort et inattendu sur l’enseignement des mathématiques en France : les programmes scolaires, de la maternelle à la fin du lycée, que suivaient les jeunes français des années 70 et jusqu’au milieu des années 80, reposaient sur une approche purement axiomatique des notions, sans jamais, ou en tout cas très rarement, s’encombrer de situations concrètes. C’était la grande époque des « maths modernes » où l’on enseignait la numération dans toutes les bases en primaire, ainsi que les ensembles, les groupes, les anneaux et les corps en première et terminale. Les enseignants de ce début du 21ème siècle sont ces élèves des années 70 et 80.

Assez vite, il a bien fallu commencer à s’interroger sur la motivation des élèves face à l’enseignement des mathématiques : on devait expliquer à ces générations d’élèves et tenter de les convaincre souvent en vain, que ces objets abstraits et formels, qu’on leur assénait de façon péremptoire, leur permettraient sans doute un jour de résoudre des problèmes. Apprendre à compter, même le sens des nombres étaient devenu secondaire.

Quelques 30 ans après l’extinction officielle des programmes purement axés sur cet aspect des mathématiques, la communication rigoureuse des raisonnements, à laquelle on a longtemps eu l’habitude de se référer par le terme « rédaction », est toujours explicite dans les instructions officielles et la culture mathématique française y reste très attachée, souvent au détriment de l’étendu et de la profondeur des concepts étudiés. Cette exigence, en faisant obstacle à l’appropriation des concepts par les élèves, voire par les enseignants, a même contribué à écarter de l’enseignement primaire comme secondaire des notions fondamentales dont l’introduction était rendue impossible par cette quête absolue de « rédaction ». Les réformes se sont succédées, sans jamais totalement venir à bout de l’esprit des programmes des années 70-80 ; ce n’est que très récemment, en 2015, que les compétences de modélisation, recherche, représentation, sont explicitées et tiennent le même rang dans les intentions des programmes scolaires, à côté des compétences plus traditionnelles de calcul, de raisonnement et de communication.

Prenons l’exemple d’un problème que tous les élèves de 4e français connaissent : un triangle ABC ayant pour dimensions AB = 4 ; BC = 7 ; CA = 5 est-il rectangle ? La communication attendue de l’élève est la suivante.

Si ce triangle était rectangle, son hypoténuse serait le plus long de ses trois côtés, c’est-à-dire [BC]1

D’une part, AB2+AC2 = 42 +52 = 16 + 25 = 41.

D’autre part, BC2 = 72 = 49. 41 ≠ 49 : d’après la contraposée du théorème de Pythagore, ABC n’est pas rectangle.

Nos collègues anglophones, formés différemment à l’enseignement des mathématiques verraient cette réponse comme parfaitement correcte :

ABC right-angled?

AB2+AC2=16+25=41 but BC2=49 so ABC is not right-angled.

Cet élève est-il moins rigoureux ?

A-t-il pour autant moins bien saisi les subtilités du théorème de Pythagore, de sa réciproque, de sa contraposée, que son camarade français ? Rien n’est moins sûr.

Dans le monde anglophone, on construit une notion parce qu’elle permet la résolution efficace d’une question, sans s’embarrasser du langage mathématique ni de sa grammaire. Cela permet l’introduction plus précoce de concepts traditionnellement vus comme difficiles, voire inabordables en France. C’est ainsi que les élèves britanniques manipulent les fractions très tôt dans leur scolarité primaire, ceux en Key Stage 3 (équivalent de la 6°/5e/4e) manipulent les fonctions polynômes du second degré ou les fonc- tions de type exponentiel, savent en tracer les courbes et les utiliser dans des modélisations, alors que leurs homologues français ne les verront que bien plus tard en classe de première, certes avec tout le langage mathématiques requis mais en allant moins loin dans la maîtrise de ces objets que leurs camarades de 4e scolarisés outre-Manche.

Il n’est pas question pour nous de renoncer à la rédaction à la française qui a ses vertus. Il nous faut plutôt la remettre à sa juste place : introduire les concepts de façon simple en pointant leur utilité pour résoudre un problème, et ainsi motiver les élèves en leur rendant ces concepts plus familiers, laisser le langage mathématique complexe à plus tard, lorsque ces concepts sont intériorisés.

La collaboration de nos enseignants francophones et anglo - phones dans le primaire va permettre de prendre cette route, l’introduction d’une partie de l’enseignement des mathématiques en anglais que nous envisageons en 4e l’an prochain, et est en cours d’expérimentation à Londres, ira dans ce sens, les APs Calculus BC et Statistics désormais présents à titre optionnel dans le BFI, permettront à ceux de nos élèves qui le souhaitent d’aller plus loin que le programme français.

An American Point Of Viewguy Manuel

by Guy Manuel Trustee

The following is based on my own experience, first as a student of mathematics in both France and the United States, and more recently as a mathematics teacher in New York (and observer in France and the UK).

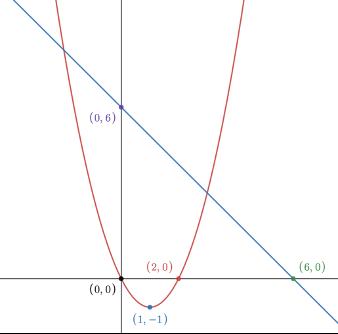

The bigger difference I see between math in French or English lies not so much in the pedagogy, which is strongly teacher-dependent, as much as the way math content is presented and assessed. Let me present an example of finding the intersection of a line and a parabola, and how such a problem might be posed in both French and English.

You will notice that the French presentation is scaffolded and uses a complex language. The English version, on the other hand, appears to be more open-ended than the French.

A student solving this problem in French will carefully write the answer to each question, justifying everything they write. They will not understand, until the last question, what problem they are trying to solve. The English problem will engage more the visual, intuitive, and creative capacities of the student:

(a) Dans un repère orthonormé (O,I,J), on considère une droite représentant la fonction affine f définie sur R par f(x)=6-x et celle de la fonction g définie sur R par g(x)=x2-2x they know what question they are trying to solve.

(i) Quelle est la nature de la courbe de la fonction g ?

(ii) Représenter dans (O, I, J) les courbes représentatives de f et g.

(iii) Indiquer sur le graphique les points d’intersection de ces deux courbes.

(iv) Soit un réel x. Montrer que x représente l’abscisse d’un des points d’intersection ci-dessus si et seulement si x2-x-6=0 [1].

(v) Montrer que l’équation [1] est équivalente à l’équation [2] (x-3)(x+2)=0.

(vi) Trouver les coordonnées de tous les points d’intersection des courbes de f et g.

It is important to note that some teachers might believe that being more formal and theoretical means being more rigorous, but that is not necessarily the case. I have taught many subjects in an informal way, focusing on concepts, while still making sure that students are able to construct rigorous arguments to either explain a concept to the class, or when solving any problem. In the end, it seems that the ideal school environment would combine both French and English ways of teaching.

ADVANCED PLACEMENT (AP) & THE BACCALAURÉAT FRANÇAIS INTERNATIONAL (BFI)

by Bernard Manuel Chairman

they are recognized as world-class courses whose successful completion demonstrates a student’s academic potential and excellent preparation for higher education.

AP subjects now in the BFI

For the very first time, the ministère de l’Éducation nationale offers, through the American BFI, an opportunity to substitute up to three APs for part of the French bac.

“Les élèves engagés dans le BFI section américaine pourront obtenir à la fois le BFI et deux ou trois Advanced Placements simultanément.

Cette innovation de taille me semble être un pas nécessaire pour accompagner la croissance des sections américaines.”

Pap Ndiaye, Ministre de l’Éducation nationale

In September 2022, the BFI officially replaced the OIB. At École Jeannine Manuel in Paris, Lille, and London, the American section of the BFI is the French bac track – the other track being the International Baccalaureate.

The BFI is adapted from the standard French bac in bilateral partnerships with countries including Algeria, Australia, Brazil, China, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Japan, Morocco, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Tunisia, the UK, and the US. The American version is the largest and fastest-growing internationally: it is already present in thirty-one countries.

Advanced Placement (AP) Courses

The American BFI is the academic brainchild of a partnership between the ministère de l’Éducation nationale and College Board, the North-American association of 6,000 schools and universities that sets US Higher Education entry standards. APs are one-year collegelevel courses offered in 39 academic subjects. Each year, more than 3 million students in 159 countries sit 5 million AP exams.

APs are highly valued in the US and Canada and by top-ranked English curriculum universities worldwide;

We have chosen to take advantage of this opportunity because of the worldwide recognition of APs, but also because the cultural perspective of these American APs reinforces the bicultural spirit of our American section. We also believe that AP learning objectives contribute to honing essential transdisciplinary critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication skills.

Another tactical but crucial reason for choosing APs is that they take place in May of première and substitute for the written exam taken at the end of terminale in two BFI subjects. In those subjects, AP BFI students will thus only have oral exams in terminale and only on the terminale portion of the curriculum. This shift means less stress, a lighter workload, and more time to focus on higher education choices and university applications.

AP exams are marked externally by College Board examiners. AP grades range from 1 to 5 and are multiplied by four to be converted to the French (0-20) scale.

AP substitutions (options vary among our schools and may evolve)

Advanced English Literature is called approfondissement culturel et linguistique (ACL) in French. The two-year BFI ACL curriculum is assessed at the end of terminale with a four-hour written exam and a thirty-minute oral exam, each bearing a coefficient of 10.

Since our school opted for AP, our students study the AP English Language and Composition or the AP Literature and Composition curriculum in première and sit the AP exam in May of première. In terminale, they follow the standard American BFI ACL curriculum and, in June, only take the oral exam: the première AP exam replaces the terminale written exam.

History-Geography. The two-year BFI curriculum, taught partly in English and partly in French, is assessed at the end of terminale with a four-hour written exam and a twenty-minute oral exam in English, each bearing a coefficient of 10.

Since our school opted for AP, our students study AP European History or AP Human Geography in première, entirely in English, and sit the AP exam in May of première. In terminale, they follow the standard American BFI History-Geography curriculum, taught partly in English and partly in French, and only take

“We have found that the best predictors at Harvard are Advanced Placement tests and International Baccalaureate exams…”

William R. Fitzsimmons, Harvard Dean of Admissions

the oral exam (in English). The première AP exam replaces the terminale written exam.

Math AP electives: a very special case

Mathematics occupies a mythical place in France, enshrined in a proud tradition: France shares with the US a record of fourteen Fields medals (out of 64).* This revered legacy is reflected in electives offered in terminale: mathématiques expertes for students who opt for spécialité mathématiques and mathématiques complémentaires for students who do not.

American BFI students may substitute either AP Calculus BC or AP Statistics for mathématiques expertes and AP Statistics for mathématiques complémentaires. Unlike the other APs, however, the substitution involves the curriculum, not the exam. Instead, the exam is a twenty-minute oral—in English—on the chosen AP math curriculum. Most importantly, the oral exam grade carries a coefficient of 20 instead of 2 for mathématiques expertes or mathématiques complémentaires!

Students can sit the AP exam if they wish or need it for university, but the outcome does not impact the BFI grade.

AP Calculus BC is a subject whose successful completion evidences exceptional aptitude for math. This is true in the US but also in the UK, where Cambridge University’s website, for example, notes that “for Cambridge courses that ask for Mathematics and Further Mathematics A Level, Calculus BC is strongly preferred.” Calculus BC thus opens the doors to the most selective math courses in the UK, as does IB Higher Level Mathematics.

AP Calculus BC is also an excellent preparation for CPGE (MPSI, MP2I, and PCSI). Indeed, Henri IV and Louis-Le-Grand prépas teachers published a 184-page document to help students prepare for their top prépas, « dans une optique assez proche du calculus anglo-saxon. »

A word of caution: AP Calculus BC involves two periods of weekly instruction – taught in English – in première and three periods in terminale. This course, exciting and rewar- ding for math lovers, is a superb preparation for the most demanding university courses in mathematics, engineering, computer science, and economics. It also provides a helpful transition from French to English-language mathematics. It does, however, involve a curriculum significantly beyond the level expected of spécialité mathématiques and mathématiques expertes

“Global issues and problems require global solutions. And when I think of our partnership coming together, with the rigor of the French bac, and the rigor of the Advanced Placements, and their enlightened approach to education, where students are able to think broadly about the world, we are preparing the future..”

James Montoya, College Board