Transformations of the Forgotten

Climate change adaptive design and community-driven resilience in Kiribati

Edward J. Couper

Dedicated to my Mum and my Dad who wanted to be an architect but never got the chance, my extended family of Jerusalem Passage for their ongoing support, and the children of Kiribati - the future of this captivating land.

Special thanks also to the girls of the Kiribati Health Retreat (Taraem, Maria, Memroo) for the translation help, introductions and general assistance, and Darren James for the photography tips and adventures.

te mauri, te raoi, te tabomoa health, peace, prosperity

MA Architecture // London Metropolitan University Edward Couper // 15011157

INSIDE COVER: Fig. 1. View over what was the village of Tebunginako.

PREVIOUS: Fig. 2. Children running errands. North Tarawa.

NARRATIVE OF THE ISLAND

PREVIOUS: Fig. 3. Sunset over the lagoon. Abaiang.

Tarawa. From Betio Island to Temaiku village. It was going to take at least an hour. One hour if it wasn’t peak time, but it was nearly 3pm and schoolchildren would soon be flooding the streets. The bus ride from Betio to Temaiku would be long, cramped and stuffy. With the bus route ending and starting from Betio Island, getting a seat would not be an issue. A bus - basically a privately owned minivan with seats - would come every 5 mins or so. The small vehicle would seat no more than 15 in the back and 3 in the front - music blasting from the radio, or more often than not a Bluetooth connection with the driver’s mobile phone. I had just come from an Outer Island - Abaiang. One of the boat propellers had broken on the way, but we were eventually rescued. What should have been an hour long trip ended up being closer to two. I walked from the dock under the bright tropical sun to the nearest bus stop, stopping at a small shop selling tinned food and mobile phone recharge vouchers. I was there for the vouchers. Two white guys appeared out of nowhere. “Hey where can we go? What can we do here?” one asks. They followed me to the bus stop - our shared experience of being a minority in this land giving us some common ground. They were Russian sailors on shore leave, having pulled in to deliver cargo on their way around the Pacific. A bus stopped, the door pulled open and we got in. As was the case in all previous bus rides I had undertaken on Tarawa, the driver was a man with a woman taking care of the money collection and managing the door, which was invariably always broken and needed to be manually held shut for the whole trip. This time the driver was a man again, but the attendant was a Kiribati transgender - wearing womens’ clothes and lipstick, he was middle aged and balding. However the hair he did have was long like other women on the island. I passed her a couple of Australian dollars and received some cents back - this would take me all the way. I sat at the back, my rucksack on my lap, the breeze from the ocean whipped through the open window beside me. I went to close it only to find the whole pane of glass was missing entirely. Not many vehicles make it to Tarawa, and for good reason. The island is small and waste and spare parts either end up in the ocean, reused or more recently in landfill,which we passed after crossing the causeway connecting Betio to Bonriki. Along this stretch 4000 Japanese fought and lost their lives against the incoming US troops. Their gun towers and the remains of their fortress rusting in the sun. One road services the long and narrow island, and as such the whole island can be experienced in a single trip. This is the narrative of the island.

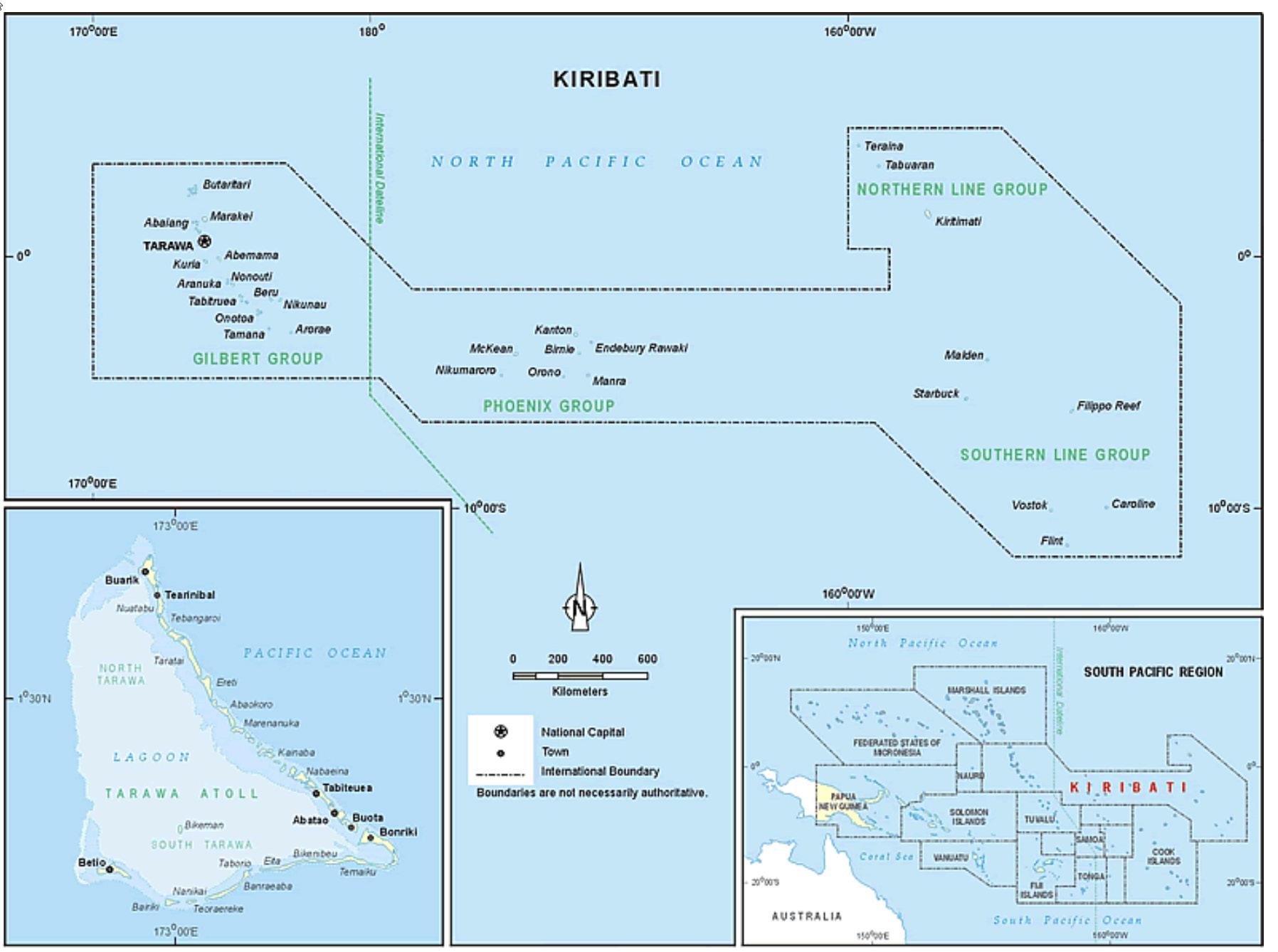

A small collection of 33 islands, mostly coral atolls, make up the paradisiac nation of Kiribati (pronounced Kee Ree Bass1) . Previously a British colony, the Republic of Kiribati was formed in 1979. The islands are collected into three groups, the Gilberts, the Phoenix Islands and the majority of the Line islands.2 They are spread across a large portion of the Pacific - enclosing a rich and UNESCO protected stretch of ocean. While they are a small group of people, their ethnicity is nearly 90 percent pure I-Kiribati3 and as unique as their culture which is deep and embedded in their homelands. As part of my research I spent time in Kiribati and found their way of life and their community-driven approach empowering. Their lifestyle is idyllic when compared to the Generation Y in the Global North who work to cover basic living expenses and rent - constantly increasing their amount of debt.4 There are lessons to be learned from this simple and yet great quality of life existence. They are however under threat. All but one island is low-lying with the highest point only 3m above sea level5. With sea levels projected to rise between

Creation of the Atoll

The Atoll is created over a very long period of time. What were originally active volcanoes, become dormant, with microorganisms settling in the porous volcanic rock beneath the surface. These polyps or coral began to grow upwards in search of sunlight, their growth exceeding the gradual covering of the volcano by rising sea levels. As they reached the surface, they would die and break off, turning into sand which would accumulate with algae to create the land mass of the islands as seen today. The islands continue to evolve with coral continuing to grow. As the sea levels rise, currently used and populated land will shift and change with new land created elsewhere.

1. Many words of the Gilbertese (now known as Kiribati) language I have picked up from my travels. To check their spelling I have referred to the following as a standard: “Kiribati-English Dictionary,” Kiribati - English Dictionary <http://www.trussel.com/kir/dic/dic_a.htm> [accessed 1 September 2017]

2. Rainbird, Paul, “Islands and Beaches: the Atoll Groups and Outliers,” The Archaeology of Micronesia, 225–44 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511616952.009>, p. 231.

3. “The World Factbook: KIRIBATI,” Central Intelligence Agency (Central Intelligence Agency, 2017) <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/kr.html> [accessed 1 September 2017]

4. Barr, Caelainn, and Shiv Malik, “Revealed: the 30-Year Economic Betrayal Dragging down Generation Y's Income,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, 2016) <https://www.theguardian. com/world/2016/mar/07/revealed-30-year-economic-betrayal-dragging-down-generation-y-income> [accessed 1 September 2017]

5. “Pacific Climate Change Science,” Pacific Climate Change Science <http://www. pacificclimatechangescience.org/rising-sea-levels-is-a-huge-national-issue-in-kiribati/> [accessed 1 September 2017]

PREVIOUS: Fig. 4. View towards Betio from Eita, Tarawa.

OPPOSITE: Fig. 5. Map of Tarawa and wider Kiribati.

2m to 2.7m by 21006 due to recently re-adjusted surface temperature warming projections7 the future is potentially catastrophic for the I-Kiribati.

2050 is seen to be a doomsday for many studies. MIT researchers have said that 52 percent of the world’s population will be exposed to severe water scarcity by then8. In the Global South an average of 5 million people move from rural areas to cities every week9, with half the world projected to live within 100 km of the coast by 2050. 80 percent of our largest cities are on the coast or a floodplain. The World Health Organisation estimates 12.6 million people will die globally as a result of pollution, climate-related weather and disease and projected an additional 250,000 deaths between 2030 and 2050 alone due to “unhealthy environments”10. These projections present huge challenges for humanity collectively but especially in the poor and less developed parts of the world that are looking at millions of people displaced from their homes and communities. In the context of this paper I question: what mitigating role can architects and architectural practice play and in what way should they approach it?

6. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States (2017), p. vi.

7. Strickland, Ashley, “Earth to Warm 2 Degrees Celsius by the End of This Century, Studies Say,” CNN (Cable News Network, 2017) <http://edition.cnn.com/2017/07/31/health/climate-change-twodegrees-studies/index.html> [accessed 1 September 2017]

8. Alli Gold Roberts | MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, “Predicting the Future of Global Water Stress,” MIT News, 2014 <http://news.mit.edu/2014/predicting-the-futureof-global-water-stress> [accessed 1 September 2017]

9. Moreno Eduardo López., State of the World's Cities 2008/2009 Harmonious Cities (London .: Earthscan : for UN-HABITAT, 2008), p. xi.

10. “An Estimated 12.6 Million Deaths Each Year Are Attributable to Unhealthy Environments,” World Health Organization (World Health Organization) <http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/ releases/2016/deaths-attributable-to-unhealthy-environments/en/> [accessed 1 September 2017]

Population Growth and Internal Migration

The population in 2015 was 110,136 and spread out over 24 inhabited islands. Net migration was -4 per 1000. Population growth in 2010 was 2.2 percent overall, however South Tarawa’s growth rate boomed to 4.4 percent compared with 0.2 percent in all the other islands combined. Economic growth centred around the capital island has been an attractor as well the constant disruption caused by sea level rises on the Outer Islands. This is putting severe pressure on the island of Tarawa, with much land being consumed by new construction and basic services such as water and sanitation dropping in standard. As a result the government has begun implementing a strategy to encourage people not to migrate from the outer islands and improve economic and social access and transport to them.

Aside from this threat, the island paradise faces other connected issues. A move to Western working hours and structure on the main island Tarawa has led to a heavy migration from the outer islands in search of opportunity. Land is rented to families and in turn sub-let to other families, with a density occurring on Betio that puts Manhattan to shame. But without the verticality of Manhattan, or a plumbed sewage system, this has led to a buildup of waste and sanitation which has become a serious problem. A growing reliance on imported food stuffs and especially additive sugars has led to a rise in diabetes. The waste packaging having nowhere to go but build up on the beaches. The biggest issue they face is all encompassing however and questions whether the islands will even exist in the near future. The highest point on Tarawa is proudly marked out on a sign in the middle of the island: 3m above sea level. Rising sea levels induced by climate change and the wild storms that accompany them results in normal spring tides becoming major flooding events inundating homes under metres of water.

The people of Kiribati are however very proud, energetic and forwardthinking - looking to meet these challenges head-on. The younger generations especially with help from some elders are leading an innovative charge towards self-reliance and environmental adaptation. The integration of new technologies has meant that they have in some respects skipped the 20th century. They use lightweight, low maintenance tech such as solar panels to charge low voltage electrics, water tanks and manual water pumps to make big impacts in their communities.

Ultimately my aim here is to both propose and challenge existing patterns of thought when dealing with such complex problems, the role of technologies and lessons learned from the West, but also the need to take a step back as designers and realise that the perfect solution is not always the most likely to succeed long-term and through use of our “soft” powers we can perhaps have a greater impact. It is my

hope that my investigations here will give hope and lead to further empowerment and investment in the areas that count to ensure that cultures like the I-Kiribati can continue to thrive and that, in this age of adaptation, we in the West look to form closer bonds in our dense urban and suburban realms with the underlying environments that house them. By re-evaluating the role of architects in these complex scenarios we can re-energise and add value to architectural practice and resist further marginalisation of the profession.

Over the course of putting together this Master of Arts in Architecture dissertation, both my motivation and choice of subject matter has been questioned again and again - especially by architects in practice. Why Kiribati? Where is that? Surely there are more important issues to tackle? In places with larger populations? Areas of dense urbanity and constant flux and change? Of money and massive resources and heavy infrastructure? And in the case of one American architect: “Why don’t they just move?” Hopefully I have already begun to answer some of these questions, but what follows here is both my own personal story of design, my investigation and connection to an incredibly isolated and unknown people, and what the experience has taught me about the architect’s role going forward in dealing with large scale issues that are beyond the control of the single auteurist designer. What could the future look like? And how can the innovations of the West, and the lessons we have learned over our period of industrialisation be integrated with an old culture and a proud people living in a very vulnerable part of the world? This paper is not about money, fast actions and large investment, but rather small considered steps, taken over a long period that can create long lasting results to build the resilience of a community - identifying a narrative and helping that story continue.

OPPOSITE: Fig. 6. Drowned lands in Bonriki. Tarawa.

METHODOLOGY + LITERATURE REVIEW

PREVIOUS: Fig. 7. Children carry inaki made of pandanus leaves for use as roof thatching. Abaiang.

This dissertation acts in part as a personal journey of the design process and an analysis of this. Common in modern architectural practice, design work is done in a silo, usually without even visiting the site. In the design studio I formed a brief to design a deployable solution that would build up to form an integrated long term building typology.

I will firstly look into the particular context of Kiribati and their culture, then look at how outside influences have contributed both negatively and positively. I will then describe the design proposal and analyse it in the context of the role of the architect. The issues and responses here have required a broad sweep of multiple different areas of research including ocean science, anthropology, history, psychology as well as developmental planning and spatial theory. Through my architectural research straddling these fields, this paper aims to apply established thought to the particular context of Kiribati. A transdisciplinary approach is important to tackle such comprehensively complex issues such as climate change affected communities.

Interspersed throughout are personal anecdotes, photos, conversations and observations from my time in Kiribati. It is important to note that my visit took place after I had put forward my initial design proposals. My thoughts on the design following the trip will be discussed in the analysis. I met with local leaders, local people and government and aid workers. Uncited photos were taken by myself using a DSLR and camera drone. All collection of material was taken with respect, permission was sought before any photo was taken and a research permit was issued for my stay. I have included the personal anecdotes in order to describe the humanity involved and present a wider narrative.

In understanding the socio-economic, political and cultural makeup of modern Kiribati I have turned to a number of different sources. The Kiribati

Development Plan (KDP) 2016-19 - which details much of current government policy - has been useful as a primer for the various issues at play in Kiribati. News articles and personal blog posts were also useful in having an understanding prior to my visit. However through my primary research investigations I have been able to see first hand both what aid work is doing much of which is yet fully documented publicly.

It is not the purpose of this paper to dig too deeply or to question climate change science. It is given that climate change is a real threat and through news articles, global reportage and research cited it is shown that this is a global threat that will affect everyone in some way. Scientific literature regarding the specific threat to coral atoll ecosystems has been considered as part of site specific research. Woodroffe has demonstrated the specific vulnerability of coral atolls to sea level rise.11 However Webb and Kench have put forward that due to the special living ecology of the coral atoll and its barrier reef, the islands have been observed to have grown in places and are gradually moving laterally as the reef continues to grow and break apart with sediment accumulation over a long period of time.12 Whether this growth can continue is heavily dependent on how resilient the existing coral fields are to further sea warming and ocean acidification. Nevertheless the foreseen exponential rise in sea level over the next 100 years will result in a race that will no doubt continue to present challenges and major flooding events for Kiribati and other similarly low-lying islands nations.

11. Woodroffe, Colin D., “Reef-Island Topography and the Vulnerability of Atolls to Sea-Level Rise,” Global and Planetary Change, 62 (2008), 77–96 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2007.11.001>

12. Webb, Arthur P., and Paul S. Kench, “The Dynamic Response of Reef Islands to Sea-Level Rise: Evidence from Multi-Decadal Analysis of Island Change in the Central Pacific,” Global and Planetary Change, 72 (2010), 234–46 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2010.05.003>

Western influences in Kiribati have been well documented firstly by Sir Arthur Grimble (British Resident Commissioner 1914 - 1933) in his memoir13 and subsequently by Henry Evans Maude (Resident Commissioner 1946-1949) whose anthropological studies of the islanders and the architecture has shown usage of the Kiribati meeting hall or maneaba has changed as their culture has evolved over time14. These writings are essential to fully appreciating the historical depth of the I-Kiribati, a history which is orally passed down generation to generation and was not previously transcribed. It is also key to understanding how historical and cultural narratives have directly informed - and continue to inform - the public spaces of the community.

There is a strong relationship between identity and how people use space. In the private realm, the individual’s own connection to their home and importance placed on the control and continual negotiation of this space has been explored in depth. John Turner has argued that housing should not be thought of as a product or object but rather as a process that people engage in to their own benefit.15 This line of thought echoes Heidegger who posited that a house is not necessarily a home and that the existential requirements for home are not guaranteed by simply providing a person with a house.16

13. Grimble, Arthur, A Pattern of Islands (London: Eland, 2011)

14. Maude, H. E., The Gilbertese Maneaba (Institute of Pacific Studies and the Kiribati Extension Centre of the University of the South Pacific, 1991)

15. Turner, John F.C., and Robert Fichter, Freedom to Build Dweller Control of the Housing Process (New York: Macmillan, 1972), p. 148.

16. Heidegger, Martin, Building, Dwelling, Thinking, 2000

These ideas demonstrate that there are both individual identities but also collective identities, with one influencing the other. Maslow has shown how social cohesion can change as a response to need.17 If basic needs are not met then society tends to focus on the collective. In the Global North, our basic needs are, more often than not, met and so our focus moves to individual expression and personal identity. In the Global South however, many of these basic needs are not met and so people collectively band together to solve common issues.

Miller’s collection of stories of the individual inhabitants of a single street in London demonstrate that the daily struggle to make life meaningful is not restricted to the Global South and that objects become a way of expressing identity. Autonomy is granted to those that have benefitted from the resources and efficiencies of the modern state.18 Barac builds off this by writing of how a woman photographed in a South African shantytown uses a yellow curtain to separate a public space from a private one and how that demonstrates how such everyday objects can hold great symbolism and meaning for those that own them. 19

This is architecture for the majority of the world - a world where the majority lives in poverty, or worse - as the UN has classified Kiribati - a Least

17. Barnes, Matthew, “Classics in the History of Psychology -- A. H. Maslow (1943) A Theory of Human Motivation,” Classics in the History of Psychology -- A. H. Maslow (1943) A Theory of Human Motivation <http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm> [accessed 1 September 2017]

18. Miller, Daniel, The Comfort of Things (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015), p. 295.

19. Barac, Matthew, “Technologies of Belonging: Object Relations in the Architecture of Reconstruction”, Catching Up with People’s Processes: Learning from Housing Reconstruction Beneficiaries in South Asia and Beyond (Unpublished manuscript)

Developed Country20 which is a classification of extreme economic vulnerability. We should be careful however when we examine through our Western lens. What might seem terrible “poverty” to us is very relative. Most people are their own architects, using and attaching meaning to seemingly ordinary items. In these small ways, people express their identities.

The gap between these two worlds highlights some key issues that face the architectural profession. In Architecture Depends, Jeremy Till put forward what he sees as a “gap between what architecture - a practice, profession, and object - actually is (in all its dependency and contingency) and what architects want it to be (in all its false perfection)”.21 He sees the profession as paralytically insular, ignorant to “world realities”22 and working in a “vacuum”23.This builds off of Banham that likened architectural practice to a cult, like a black box of secrecy which is “perpetually open to the suspicion, among the general public, that there may be nothing at all inside the black box except a mystery for its own sake.”24

Till goes further: he puts forward the idea of “Low-fi architecture”. By embracing the contingency inherent in the work of the architect - that is understanding that the architect’s work to be successful is highly dependent upon others’ contributions - architecture can become more grounded, more

20. “Least Developed Country Category: Kiribati Profile | Development Policy & Analysis Division,” United Nations (United Nations) <https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developedcountry-category-kiribati.html> [accessed 1 September 2017]

21. Till, Jeremy, Architecture Depends (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), p. 2.

22. Ibid., p. 191.

23. Ibid., p 19.

24. Banham, Reyner, and Mary Banham, A Critic Writes: Essays by Reyner Banham (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p. 299.

understanding of realities and produce successful outcomes.

This considered approach contrasts sharply with Rem Koolhaas’ assertion that “architecture is too slow”.25 In his highly graphical book Content he describes the speed of the global markets driven by relentless ambition and needs for selfexpression. The profession cannot keep up with the demand of the new digital economies, though he conceded its noble nature is paradoxically reassuring. His views are echoed in many of the top practices of today and can be seen as part of our broader Baudrillardian postmodern culture - the fixation on better than better, beyond perfectionism and the endless drive of the pursuit of it.26 Outspoken on the shortcomings of architecture, he wrote that architecture still gives us hope that “shape, form, coherence could be imposed on the violent surf of information that washes over us daily”.27 However he has also said that: “Architecture is a profession that takes an enormous amount of time. The least architectural effort takes at least four or five or six years, and that speed is really too slow for the revolutions that are taking place.”28 Architectural practice finds itself torn between ethical considerations and commercial realities.

For practice in the developing world, Hamdi has argued that focusing on successful small locally based projects that build on collective local knowledge can grow organically to impact a larger or global context.29 This is the idea of

25. Koolhaas, Rem, Content (Koln: Taschen, 2004), p. 20.

26. Baudrillard, Jean, The illusion of the end, trans. by C. Turner (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994)

27. Koolhaas, p. 20.

28. Budds, Diana, “Rem Koolhaas:” Co.Design (Co.Design, 2016) <https://www.fastcodesign. com/3060135/rem-koolhaas-architecture-has-a-serious-problem-today> [accessed 3 September 2017]

29. Hamdi, Nabeel, Small Change: about the Art of Practice and the Limits of Planning in Cities (London: Earthscan, 2009), p. xviii.

“emergence” - the idea that “it’s better to build a densely interconnected system with simple elements and let the more sophisticated behaviour trickle up”.30 Rather than investing in expensive, complex and difficult to maintain solutions - which usually provide a source of fascination for architects - small interventions can have a long-lasting positive impact.

The particular location of Kiribati - in the middle of the Pacific - presents interesting, yet potentially challenging options. Technological innovation and creative energy mixed with the needs of countries like the Netherlands, which are metres below sea level, as well as a need for more political freedom in some quarters, are generating a push towards water based futures. The positive and exciting opportunities alongside multiple examples of individual projects has been well-documented by architect Koen Olthuis of Waterstudio and David Keuning and present floating structures as a serious alternative for any community threatened by flooding.31

While not central to the themes or focus of this paper - which is focused on protection of existing communities - I would be remiss not to mention the main focus for floating futures is at present centred on the Seasteading Institute32, an organisation that looks to create alternative forms of government and society on the high seas utilising the freedom of international waters to do so. With much current private investment their research into technology will no doubt be useful

30. Johnson, Stephen, Emergence: the Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software (New York: Scribner, 2006)

31. Keuning, David, and Koen Olthuis, Float!: Building on Water to Combat Urban Congestion and Climate Change (Amsterdam: Frame, 2011)

32. “Vision / Strategy,” The Seasteading Institute, 2017 <https://www.seasteading.org/about/visionstrategy/> [accessed 3 September 2017]

in the years to come. In his book33, spokesperson Joe Quirk puts forward the many benefits from developing such communities, many of which ideas can already be applied to communities that live on or near seascapes. His moral imperatives as defined are to “feed the hungry, enrich the poor, cure the sick, restore the environment, power civilization sustainably and live in peace”34 which are the same imperatives as this thesis, but why can the same argument not be applied to current existing communities? I put that the same guiding principles can and should be applied here.

OPPOSITE:

Fig. 8. A Japanese gun tower left over from the Battle for Tarawa rusts in the sun.

33. Quirk, Joe, and Patri Friedman, Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity from Politicians(New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017)

34. Ibid., p. 5.

REMEMBERING WHAT HAS BEEN LOST

PREVIOUS: Fig. 9. Small islet. Tarawa.

The people of Kiribati (or the I-Kiribati as they call themselves) are a proud people steeped in a rich heritage. Their art, culture and architecture go back thousands of years and their language, while based off of neighbouring Polynesian sources, is incredibly unique. Anthropologists believe that Austronesians founded the islands thousands of years ago with Fijians and Samoans invading in the 14th century, bringing with them their own Polynesian traditions and linguistic traits. Subsequent inter-marrying has led to a homogenous ethnicity and tradition throughout. The main language spoken is Gilbertese (or Kiribati), with English also being an official language, although rarely used outside the capital. 80 percent of I-Kiribati can read English.

Their lifestyle is simple yet rich, with each I-Kiribati performing a welldefined role and associated set of rituals daily. Everything revolves around the family - a supportive environment where different skills are cultivated. Until recently, most lived in villages of 50-3000 in number. The relatively small community sizes means - on the outer islands at least - everyone knows everyone and is more than happy to lend a hand or tool to a fellow islander in need. They recycle the clothes they use, in fact new clothes are indeed rare with clothes being passed on from family to family and second hand clothes stalls readily available. Toamau like babuti are egalitarian measures in the culture, whereby each household should be toamau or balanced in skills and ages in order to be self reliant. Babuti is the custom practiced in some places that means if a household is lacking in a skill or trade, such as a copra cutter or a fisherman, then someone will be loaned out by another household that has that skill in surplus. Failure to cooperate with these traditions can however lead to ostracisation from the community which is very serious.35

35. Koch, Gerd, The Material Culture of Kiribati (Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies of the University of the South Pacific, 1986)

Each family owns its own block of land which is then broken up and shared amongst the family members. This land can sometimes extend from the lagoon side of the island to the sea. Being both heavily community-oriented and environmentally interdependent, the I-Kiribati are sensitively aware of the issues they face. As noted in the KDP they are however limited in their knowledge and understanding, with an education program seeking to address this.

When compared to similar island nations, they are a relaxed and unpretentious people, not seeking to exploit their natural resources or engage the interest of tourists and foreigners. At the same time, they have been incredibly active on the global stage, courting foreign governments for aid and beginning enterprising self sufficient programs. Their previous President, Anote Tong, was particularly outspoken, giving an impassioned speech to the UN declaring that the country was preparing for a mass migration by purchasing land overseas36 and welcomed Leonardo DiCaprio when he visited as part of his documentary film.37 At the same time, their net migration, even after government purchasing of land, has been low. This speaks of a community that is determined to stay and determined to fight together, on their own terms, but while looking to the support and insight of the world at large.

Throughout Kiribati, each village has one or more meeting halls or maneaba. They function today as covered spaces out of the heat that are open to all - a place to meet and take refuge. They are also a place of traditional ceremony and indeed the history of Kiribati is heavily linked to the traditions of the maneaba.

36. “Kiribati | General Assembly of the United Nations,” United Nations(United Nations) <https:// gadebate.un.org/en/67/kiribati> [accessed 3 September 2017]

37. Before the Flood. Dir. Fisher Stevens. National Geographic. 2016

PREVIOUS: Fig. 10. Ceremonial maneaba for each village on the island. Abaiang.

OPPOSITE: Fig. 11. Teenagers - plus a little one - practice tiere under the maneaba in preparation for Independence Day celebrations. Abaiang

OPPOSITE: Fig. 12. Maneaba being re-thatched. Abaiang.

Its original primary function was as ‘nen te boti’ - the container of the boti.38 The boti are the “exogamous, totemic and patrilineal clans of Gilbertese society”39 each having a special sitting place under the maneaba where the current head would take his position and the prestige of his ancestry would immediately be known.

The largest building by far, its eaves can soar many metres high, but they are also set low off the ground, forcing visitors to bow their head in respect as they enter. Its sacred nature was captured by Grimble: “The boles of palm trees made columned aisles down the middle and sides and the place held the cool gloom of a cathedral that whispered with the voices of sea and wind caught up as in a vast sounding box.”40

The maneaba is the physical manifestation of the community with everyone taking part in its construction. Different clans would take ownership over the different elements.41 One clan would gather the timber, another prepared the pandanus thatch, while yet another would fix them into position. The building of a maneaba was very sacred, and the sourcing of its materials were very specific. Time was important - not in terms of length, but in terms of timing. They were more concerned with doing it right, at the right time, otherwise it was considered not worth doing at all. In fact it could be downright dangerous to the community if not done properly as any mistake would be seen as bad luck.42 It cannot be impressed

38. Mason, Leonard, and H. E. Maude, “The Evolution of the Gilbertese Boti: An Ethnohistorical Interpretation,” Ethnohistory, 11 (1964), 77 <http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/480548>

39. Maude, H. E., The Gilbertese Maneaba (: Institute of Pacific Studies and the Kiribati Extension Centre of the University of the South Pacific, 1991), p. 1.

40. Grimble, Arthur, A Pattern of Islands(London: Eland, 2011), Loc. 1012.

41. Ibid., Loc. 999.

42. Maude, p. 27.

OPPOSITE: Fig. 13. Modern community maneaba . Tarawa.

enough the significance of this structure and its connection to the specific identity of Kiribati.

On Abaiang, each village has its own maneaba as well as a separate one - a ceremonial one - all of which are clustered together around a large open space in the centre of the island. This area acts as a place the whole island can gather for Independence Day and other large celebrations. Through their architecture they perform their community building.

With I-Kiribati now being predominantly Catholic (55 percent) and Presbyterian (35 percent), the maneaba has become secular with many maneaba being built using modern materials and methods. However the older maneaba still demand a sense of respect and permission must be asked from its keepers before you are permitted to enter.

Alongside the maneaba, the local people live between a series of similar structures. During the day the kiakia provides an elevated, shaded platform with open sides to rest out of the hot midday sun. The tebuia is an enclosed sleeping hut. Like the maneaba the construction uses panadus trunks being lashed together with coconut husk, and pandanus thatch. The sides are made with woven coconut leaves. The interiors of traditional homes in Kiribati are clean and clear spaces, devoid of furniture, usually housing just a series of coconut or pandanus mats that are unrolled to lie or sit on. This use of space continues in the modern homes.

This flexibility is in essence a “soft” space or a space that has no particular function for uses that have not yet been defined.43 Such spaces appear to be devoid of architecture. Families inhabit these spaces in so flexible a way as to be informal, however what appears to be messy to Western eyes is actually well ordered and defined. There is a meaning to every object and routine or ritual in its use. This is an “‘architecture of occupation’ rather than through expert provision.”44

With the urbanisation of Tarawa, as compared to the Outer Islands, the new generations of I-Kiribati are growing up in a world that has forgotten the traditional skills and architecture and looks to Western solutions to hold the answers. The move to concrete and permanent homes, rather than continuing the heritage of semi-permanent homes that can be moved, has led to accidents waiting to happen - “people have relocated to the other side [of the island] and the ones that are left are the ones now requesting sea walls”45. Concrete block has become cheaper than timber.46 It takes less effort to construct, requires much less maintenance - the traditional thatch needs to be replaced every 2 years - and presents a certain prestige by virtue of being Western. But because the concrete buildings are permanently in place and not raised off the ground they are easily flooded during a high tide, whereas the traditional buildings are moveable - able to be transported further inland when warning of high tide is given. Concrete also heats up over the course of the day and retains and releases the heat overnight due to its high thermal mass. This makes for a very uncomfortable sleeping environment, resorting in people sleeping outside in their now secondary traditional structures

43. Till, p. 133.

44. Barac.

45. Interview with Michael Foon. Appendix 1.

46. Ibid.

OPPOSITE: Fig. 14. An open, raised kiakia . North Tarawa.

Fig. 15. Modern Kiribati life. Tarawa.

OPPOSITE: Fig. 16. A typical traditional home. Abaiang.

rather than in their new modern house.

Nevertheless they are each and everyone a craftsperson, even government officials and officers, are intimately involved in the construction and maintenance of their own home. Local builders are engaged for larger projects or for families without as much building experience, but these ‘builders’ are simply local people that have experimented or have more hands-on experience or body strength without any formal training.

The ongoing modernisation of Kiribati with Western influence has meant that the pagan traditions of the maneaba have mostly slipped into memory as has much of the traditional music and dance involves chanting and body percussion that was performed within as well as stick beating called “Tirere” - except for big festivals and formal occasions.

One key upside to the move towards modern materials however is the ability to harvest rainwater through the use of metal roofs and gutter systems. Directing people to better water management with the help of NZAid is the Kiribati Climate Action Network (KiriCAN) and their sister organisation the Kiribati Health Retreat (KHR). The traditional reliance on well water, and its brackish taste, has lead to people to add sugar to better the taste. This has been one of the leading causes of diabetes in the community. Before sugar and simple starches like white rice were easily accessible, the native starchy breadfruit was more popular alongside “toddy” - or the capturing of coconut palm sap. This rich syrup can be mixed with water to create a refreshing drink.

At the KHR, young members of the community volunteer their time to come in and massage the old, and the diabetic, who suffer from poor circulation in their legs. The Retreat finds patients through word-of-mouth. Neighbours will

OPPOSITE: Fig. 17. Inside a concrete block home. Betio, Tarawa.

tell of sick family members that suffer from gout or smoking ulcers. They will then direct people to go and collect their own local produce and show people how to cook healthy, low fat, low sugar meals, using local ingredients rather than imported ingredients that usually use high amounts of sugar as a preservative. The KiriCAN and KHR initiatives are examples of grassroots organisations that are having a small but steady impact on the community.

This is in essence a collective re-learning. What was once the stable and nutritious diet of the I-Kiribati has now given way to Western conveniences. Within a generation key skills have been forgotten and disease incidences have increased. Food habits provide insight into the generational divide, as does the shift between the architecture of the Outer Islands - in all its flexibility and adaptability - compared to the static, environmentally resistant and damaging concrete homes of the main island. Traditional Kiribati culture was not concerned with speed or convenience. Time was measured in days and the emphasis placed on doing things ‘properly’ or according to tradition, while taking pride in the architecture and using it as a source of community building, in turn defined their collective identity.

OPPOSITE TOP LEFT: Fig. 18. Preparation of noni juice. KHR, Tarawa.

OPPOSITE BOTTOM LEFT: Fig. 19. Each patient brings their own nonis. KHR, Tarawa.

OPPOSITE TOP RIGHT: Fig. 20. Breadfruit is mixed with vegetables to form cakes for roasting. KHR, Tarawa.

OPPOSITE BOTTOM RIGHT: Fig. 21. Digital capture of the process so it can be copied at home. KHR, Tarawa.