WeatherAnalysis andForecasting

Thispageintentionallyleftblank

ApplyingSatelliteWaterVaporImagery andPotentialVorticityAnalysis

SecondEdition

ChristoG.Georgiev

NationalInstituteofMeteorology andHydrology

BulgarianAcademyofSciences

PatrickSanturette

ForecastingOperationsDepartment Me ´ te´o-France

KarineMaynard

ForecastLaboratory Me ´ te´o-France

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier

125LondonWall,LondonEC2Y5AS,UK

525BStreet,Suite1800,SanDiego,CA92101-4495,USA

50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,USA

TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UK

Copyright © 2016,2005ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearance CenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher(other thanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroadenour understanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingandusing anyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationormethods theyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhavea professionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assumeany liabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceor otherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthe materialherein.

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

ISBN:978-0-12-800194-3

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublications

visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/

Publisher: CandiceJanco

AcquisitionEditor: SaraScott

EditorialProjectManager: TashaFrank

ProductionProjectManager: VijayarajPurushothaman

Designer: MarkRogers

TypesetbyTNQBooksandJournals

Thecoverillustrationismadebyoriginalimagesproducedforthepurposesofthisbookbytheauthorsusing dataavailableinMe ´ te ´ o-France.Thesearesatellitewatervaporimagesoverlaidbymeteorologicalfieldsfor analysisofcasesconsideredinthematerial:TopleftinChapter3,Section3.5.3.1;ToprightinChapter3, Section3.6;BottominChapter4,Section4.3.2.

PART1FUNDAMENTALS

CHAPTER1ADynamicalViewofSynopticDevelopment ....................................... 3

1.1 VorticityandPotentialVorticity.................................................................................3

1.2 TheConceptofPotentialVorticityThinking.............................................................6

1.2.1TheConservationPrinciple..............................................................................6

1.2.2TheInvertibilityPrinciple................................................................................7

1.2.3ClimatologicalDistributionofPotentialVorticity...........................................7

1.2.4PositivePotentialVorticityAnomaliesandTheirRemote Influence...........................................................................................................9

1.3 OperationalUseofPotentialVorticityFieldstoMonitorSynoptic Development.............................................................................................................10

1.3.1Upper-LevelDynamics,DynamicalTropopause,andDynamical TropopauseAnomaly.....................................................................................10

1.3.2JetStreamandJetStreaks..............................................................................12

1.3.3SynopticDevelopmentasSeenbyPotentialVorticityConcepts..................14

1.3.4AnalysisofaReal-AtmosphereStructure.....................................................15

CHAPTER2TheInterpretationProblemofSatelliteWaterVapor Imagery

2.1 InformationContentof6.2and7.3 mmChannels....................................................21

2.1.1OriginoftheRadiation,Radiance,BrightnessTemperature, andImageGrayShades..................................................................................22

2.1.2SensitivityRangeof6.2 mmand7.3 mmChannels........................................27

2.1.3EffectsofLayeredMoistureontheRadiance...............................................33

2.2 Abilityof6.2and7.3 mmImagestoReflectMoist/DryLayers,Clouds, andLandSurfaceFeatures.......................................................................................41

2.2.1Upper-LevelDryStructures(200 500hPa)..................................................42

2.2.2DeepMoistLayers(200 1000hPa)..............................................................44

2.2.3High-LevelMoistLayers(200 400hPa)......................................................45

2.2.4Mid-LevelMoistLayers(400 650hPa).......................................................46

2.2.5Low-LevelMoistLayers(650 800hPa).......................................................47

2.2.6Moisture/CloudinessintheBoundaryLayer(850 950hPa).......................47

2.2.7Earth’sSurfaceFeatures.................................................................................49

2.3 PotentialforOperationalUseofImagesin6.2and7.3 mmChannels ofMeteosatSecondGeneration...............................................................................51

PART2PRACTICALUSEOFWATERVAPORIMAGERY ANDTHERMODYNAMICFIELDS

CHAPTER3SignificantWaterVaporImageryFeaturesAssociated

3.1 OperationalUseofRadiationMeasurementsinWaterVaporChannels6.2 and7.3 mm.................................................................................................................56

3.2 InterpretationofSynoptic-ScaleImageryFeatures.................................................57

3.2.1Moist(Light)Featuresin6.2 mmImagery....................................................57

3.2.2Dry(Dark)Featuresin6.2 mmImagery........................................................59

3.2.3JetStreamMoistureBoundariesSeenin6.2and7.3 mmImagery...............68

3.3 Middle-toUpper-TroposphereWindFieldFeatures...............................................68

3.3.1SpecificUpper-LevelFlowPatternsSeenin6.2 mmImagery......................70

3.3.2InteractionofaJetStreamWithaDynamicalTropopauseAnomaly: JetStreakStructureEmergence.....................................................................74

3.3.3Upper-LevelDivergentFlowasaSignofAscendingMotions....................74

3.3.4Mid-LevelJetSeenin7.3 mmChannelImages.............................................83

3.4 BlockingRegime......................................................................................................91

3.4.1BlockingRegimeFormationinWhichEasterliesResultFrom Anticyclogenesis.............................................................................................94

3.4.2BlockingRegimeFormationinWhichEasterliesResultFrom Cyclogenesis...................................................................................................95

3.5 CyclogenesisandAtmosphericFronts.....................................................................97

3.5.1ExtratropicalandTropicalCyclones:EnergySourceandMain ThermodynamicCharacteristics.....................................................................97

3.5.2CyclogenesisWithinBaroclinicTroughs:LeafandBaroclinicLeaf FeaturesintheWaterVaporImagery............................................................97

3.5.3CyclogenesisWithUpper-LevelPrecursors................................................103

3.5.4UsefulnessofWaterVaporImagerytoIdentify“StingJet”and RelatedSurfaceWindGusts........................................................................116

3.5.5SplitColdFrontSeeninWaterVaporImagery..........................................122

3.6 InteractionofTropicalCyclonesWithUpper-LevelDynamicalStructures.........129

3.6.1EffectsofUpper-LevelFlowPatternintheSurroundingEnvironment ontheIntensityofTropicalStorms.............................................................131

3.6.2IntensificationofTropicalCyclonesontheAnticyclonicShearSide ofJetStreams...............................................................................................139

3.6.3EffectsofInteractionWithMidlatitudeUpper-LevelTroughs ontheIntensityofTropicalCyclones..........................................................142

3.6.4RoleoftheTropicalCycloneinanExtratropicalDevelopment AssociatedWithanUpstreamUpper-LevelCyclonicPotential VorticityAnomaly........................................................................................143

3.7 Summary.................................................................................................................152

3.7.1BasicPrinciplesinWaterVaporImageryInterpretation.............................152

3.7.2LightWaterVaporImageryPatterns:RelationtoDynamical Structures......................................................................................................153

3.7.3DarkWaterVaporImageryPatterns:RelationtoDynamical Structures......................................................................................................153

3.7.4BoundaryPatternsontheWaterVaporImagery:Relationto DynamicalStructures...................................................................................153

3.7.5Interaction/EvolutionofWaterVaporImageryFeatures:Relation toDynamicalProcesses................................................................................154

3.7.6Upper-TroposphericFlowPatternsAffectingTropicalCyclone Development.................................................................................................154

3.7.7SuperpositionofWaterVaporImageryandDynamicalFields: AToolforSynoptic-ScaleAnalysis.............................................................155

4.1 Introduction.............................................................................................................158

4.2 AtmosphericEnvironmentFavorableforDeepConvection..................................159

4.2.1TheConvectiveIngredients..........................................................................159

4.2.2ADynamicalTropopauseAnomaly(Upper-LevelCyclonicPotential VorticityMaximum)FavorsDeepConvection............................................161

4.2.3DryAirAloftIncreasesInstabilityandFavorsConvective Development.................................................................................................163

4.2.4Divergent/ConvergentUpper-LevelFlowasaPositive/Negative FactorforDeepConvection.........................................................................164

4.3 Upper-LevelDiagnosisofDeepConvection.........................................................170

4.3.1Upper-LevelDynamicsFavorableforDeepConvection inMidlatitudes..............................................................................................170

4.3.2ConvectionInitiationatDeformationZonesandUpper-Level DynamicalDryFeatures..............................................................................176

4.3.3ConvectiveEnvironmentsOvertheSubtropicalNorthPacific...................181

4.3.4DeepConvectioninBlockingRegimes.......................................................185

4.3.5Upper-LevelDynamicsandDeepConvectioninTropicalAreas...............190

4.4 UseofDataFromWaterVaporChannelsinDiagnosingPreconvective Environments..........................................................................................................194

4.4.1Upper-LevelForcing/InhibitionintheEnvironmentofMoist Convection....................................................................................................194

4.4.2Upper-LevelForcingandConvectiveInstabilityinSubtropical Areas:MiddleEastCaseStudy,December22,2009..................................199

5.5.1SensitivityAnalysesofUpper-LevelDynamicsinNumerical WeatherPredictionSimulations...................................................................260

5.5.2ImprovingNumericalForecastsbyPotentialVorticityInversion Adjustments..................................................................................................284

5.6 SummaryoftheConclusions..................................................................................296

5.6.1ComparisonBetweenWaterVaporImageryandDynamicalFields asanOperationalTool.................................................................................296

5.6.2ComparingSatelliteandSyntheticWaterVaporImageryWith PotentialVorticityFieldstoValidateNumericalWeather PredictionOutput.........................................................................................297

5.6.3UsingtheTechniqueofPotentialVorticityInversiontoAdjust NumericalWeatherPredictionInitialConditionstoBetterUnderstand theSynopticDevelopment...........................................................................298

5.6.4UsingSatelliteandSyntheticWaterVaporImagesandPotential VorticityConceptstoAdjustNumericalWeatherPredictionInitial ConditionsandtoGetanAlternativeNumericalForecast.........................298

AppendixA:RadiationMeasurementsinWaterVaporAbsorptionBand......................................301 AppendixB:PotentialVorticityModificationTechniqueandPotentialVorticityInversion toCorrecttheInitialStateoftheNumericalModel.........................................................................323

Thispageintentionallyleftblank

ADYNAMICALVIEWOF SYNOPTICDEVELOPMENT

CHAPTEROUTLINE

1.1VorticityandPotentialVorticity.........................................................................................................3

1.2TheConceptofPotentialVorticityThinking........................................................................................6

1.2.1TheConservationPrinciple............................................................................................6

1.2.2TheInvertibilityPrinciple..............................................................................................7

1.2.3ClimatologicalDistributionofPotentialVorticity..............................................................7

1.2.4PositivePotentialVorticityAnomaliesandTheirRemoteInfluence....................................9

1.3OperationalUseofPotentialVorticityFieldstoMonitorSynopticDevelopment...................................10

1.3.1Upper-LevelDynamics,DynamicalTropopause,andDynamicalTropopauseAnomaly.......10

1.3.2JetStreamandJetStreaks..........................................................................................12

1.3.3SynopticDevelopmentasSeenbyPotentialVorticityConcepts.......................................14

1.3.4AnalysisofaReal-AtmosphereStructure......................................................................15

1.1 VORTICITYANDPOTENTIALVORTICITY

Somemeteorologicalparametersaremoreeffectivethanothersforstudyingtheappearanceand evolutionofdynamicalstructuresatsynopticscale.Theconservativeparameters thosethatremain unchangedwhenonefollowsaparticleoffluidinmotion arebestsuitedtodetectandmonitorthe structuresthatplayvariouskeyrolesinameteorologicalscenario.Withtheassumptionofadiabatic motions,thepotentialtemperature q andwet-bulbpotentialtemperature qw arethermodynamictracers fortheairparticles.Theyallowustocomparethethermalpropertiesofairparticleswithouttakinginto accounttheeffectsduetothermaladvectionandpressurechanges.However,theyonlyrepresentafew oftheimportantpropertiesthatdeterminetheevolutionoftheatmosphere.Tobetterunderstandthe observedphenomena,dynamicalpropertiesmustalsobetakenintoaccount.

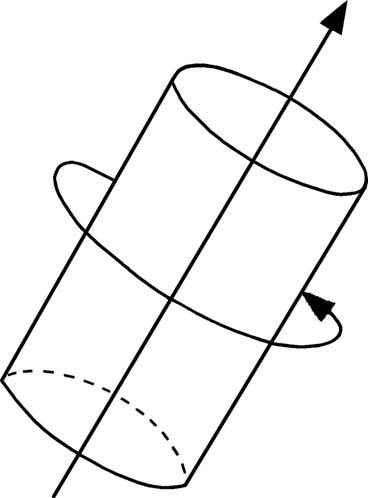

Inmidlatitudes,atsynopticscale,theimportantdynamicalpropertiesarethoserelatedtothe rotationofairparticles.ThisrotationislinkedbothtothemotionofEarthandtotherotation componentofthewind.Therotationoffluidparticlesisdescribedbythevariable vorticity.Vorticityis ameasureofthelocalrotationorspinoftheatmosphere:Itisthekeyvariableofsynopticdynamics. Asillustratedin Fig.1.1,thevorticityvectorgivesthedirectionofthespinaxis,anditsmagnitudeis proportionaltothelocalangularvelocityaboutthisaxis.Thefluidparticlesturnaroundtheirvorticity vector,andthe absolutevorticity isequaltotherelativespinaroundalocalcylinderplustherotationof thecoordinatesystem.

WeatherAnalysisandForecasting. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800194-3.00001-7 Copyright © 2016ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

FIGURE1.1

Avorticityvectorandthelocalrotationintheatmosphereindicatedbythecirculationaroundacylinderofair orientedalongthevorticityvector.

AdaptedfromHoskins,B.,1997.Apotentialvorticityviewofsynopticdevelopment.Meteorol.Appl.4,325 334.

Tointerpretaprocessintermsofquasi-geostrophictheory,onlytheverticalcomponentofthe vorticityequationisexplicitlyconsidered.Theverticalcomponentofabsolutevorticityis z ¼ f þ x, where f istheCoriolisparameterandtherelativevorticityisgivenby x ¼ vv vx vu vy .

Itisalsosupposedthat,atsynopticscale,Earth’srotationdominates(ie, z y f),inwhichcasethe relativevorticityequationcontainsonlystretchingandshrinkingofthisbasicrotation(Hoskins,1997). Twoexamplesarepresentedin Fig.1.2.Alongthezeroverticalmotionattheground,wecanmakethe followingobservations:

•Troposphericascentimpliesstretchingandcreationofabsolutevorticitygreaterthan f,thatis, cyclonicrelativevorticity,inthelowertroposphere.

•Similarly,troposphericdescentimpliesshrinkingandcreationofrelativeanticyclonic vorticityinthelowertroposphere.

•Iftheinitialrelativevorticityiszero,thetwosituationsin Fig.1.2AandB correspondto cyclonicandanticyclonicsurfacedevelopment.

viewofatmosphericdynamics.SuperimposingvariousPVfieldsontoasatelliteimageisanatural diagnostictool,wellsuitedtomakingdynamicalprocessesdirectlyvisibletothehumaneye.In particular,ajointinterpretationofupper-levelPVfieldsandwatervaporimageryprovidesvaluable informationbecausePVstructuresandwatervaporfeaturesarewellcorrelated.

1.2.2 THEINVERTIBILITYPRINCIPLE

TheconservednatureofthePVparameterandtheinvertibilityofPVenableustobuilduptheflowand temperaturestructureassociatedwithagivenPVanomaly.Theapproachdescribedin Section1.2.1 suggestsamethodtoassessnumericalmodelbehaviorbymakingmeaningfulcomparisonsbetweenan atmospheresimulatedbyamodelandreality,thatis,betweennumericalweatherprediction(NWP) outputandsatelliteimagery.Incasesofsignificantdisagreement,theinvertibilityofPVistheprinciple thatallowsustouselocalPVmodificationstoadjustinitialconditionsofoperationalnumerical models.ThusmodifyingPVinalocalareainthedirectiongivenbytheobservations,mainlybythe satelliteimagery,canleadtoimprovementinthemodelinitialstate,withallothervariables(temperature,winds,etc.)beingretrievedviaPVinversion.Errorsintheforecasttrackanddepthofa cyclonemaybereducedbycalculatinganewforecastfromthisnewinitialstate(seeSection5.5).

1.2.3 CLIMATOLOGICALDISTRIBUTIONOFPOTENTIALVORTICITY

TheclimatologicalPVdistributionintheatmosphereisremarkable.Itshowsthatonaverageinthelow levelsoftheatmospherePVisuniform(see Fig.1.4):

1. InhighandmidlatitudesthePVrangesonaverageapproximatelyfrom0.4to0.7PVUinthe troposphereandreaches1PVUaround400hPa.Thenitincreasesrapidlywithheightand takesonvaluesmuchhigherthan2PVUinthestratosphere,becomingrapidlygreaterthan 3PVUinthelowstratosphere,owingtothestrongincreaseofstaticstability.

2. Intropicareas(between10 Lat.and w30 Lat.),PVrangesfrom0.3to0.5PVUandreaches 0.5PVUnear300hPa.

ThisdiscontinuityofthePVnearthemiddleoftheatmospheretogetherwithitsconservation propertyallowsustodefinethe1.5-PVUsurfaceformidlatitudesandthe0.7PVUsurfacefortropics (excludingtheequatorialarea,within10 latitude)asatropopauseintheviewofthePVconcept.This newtropopauseiscalleddynamicaltropopause,separatingthetroposphere,withweakandquasiuniformPV,fromthestratosphere,withitsstrongPV.DefiningthetropopauseintermsofthePV conceptismoreefficientinpracticalmeteorologythantheclassicaldefinition(basedonthelapserate change),becausetakingintoaccountnotonlythetemperaturefieldbutalsothemotionfieldthrough thevorticityiswhatiscrucialindynamicmeteorology.Thisdynamicaltropopauseisjustifiedby Fig.1.5 thathighlightsitsfollowingfeatures:

1. InmidlatitudesthecorrelationbetweentheareawherethePVisonaveragecomprised between1.5and2.0PVUandtheareawherethemeanmixingratioofozoneisbetween150 and200ppm(valueofozonegivingagooddiagnosticofthemeantropopause).

2. Intropicstheregionofozoneconcentrationdescendingbelow150ppmvalue,wellcorrelated withtheareawherethePVisonaveragebetween0.5and1PVU(see Figs.1.4and1.5).

FIGURE1.4

Zonalyearaverage(verticalcross-section)ofthepotentialvorticity(PV; colorareas,every0.5PVU)andofthe potentialtemperature(blacklines inK,interval5K)intheNorthernHemisphere.ThecontourofPV value ¼ 1.5PVU(theso-calleddynamicaltropopause)isgivenin red.Thischartuseddatafrom44yearsof theEuropeanCenterforMediumRangeWeatherForecastingreanalysis,1958 2001.

FromMalardel(2008).

FIGURE1.5

ComparisonintheNorthernHemispherebetweenthethermaldiagnosis,theozonediagnosis,andthe potentialvorticity(PV)diagnosisofthetropopause.Thetemperaturefieldisazonalandaseasonalaverage, December-January-February(in colorandredlines,every10K).ThezoneofPVwithvaluescomprised between1.5and2.0PVU(forthesameperiod)isrepresentedin magentadashedarea;thecontourof PV ¼ 1.5PVUatthebottomofthe dashedarea isthedynamicaltropopauseformidlatitudes.Also representedarevaluesofmeanmixingratioofozonebetween150and200ppm(dottedblackzone, 1ppm ¼ 10 9 kg/kg).Thischartuseddatafrom44yearsoftheEuropeanCenterforMediumRangeWeather Forecastingreanalysis,1958 2001.

FromMalardel(2008).

Wecannotice(asHighwoodandHoskins,1998),thataPVdefinitionofthetropopauseisuseful alsoforthetropicsbutnotclosetotheequator(theequatorialarea,within10 latitude)wherePV surfacesbecomealmostvertical.

1.2.4 POSITIVEPOTENTIALVORTICITYANOMALIES ANDTHEIRREMOTEINFLUENCE

WecannowthinkaboutthePVdistributionitselfratherthanthebehaviorofacylinderbetween isentropicsurfaces.Theresultsmustbethesameasthosedepictedin Fig.1.2 byconsideringa coherentPVstructureatupperlevels,referredtoas“PVanomalies”(Hoskinsetal.,1985).Apositive PVanomalyisdefinedasacoherentregionofhighvaluesofcyclonicPV(positivePVvaluesinthe NorthernHemisphereandnegativePVvaluesintheSouthernHemisphere).

Theconceptofcoherentstructureisusedtoassociatemanyoftheanomaliesofinterestto meteorologytosuchfeatures,whicharelocalizedandkeeptheircoherenceintime(Pluetal.,2008). Thetimescalesofairparticlestravelinginsidesuchacoherentstructureareshorterthanthetypical timescalesoftheevolutionofsuchastructure.Therefore,suchacoherentpositivePVanomaly undergoesatimeevolutionthatmaybeinterpretedbydynamicaldiagnoses.

Fig.1.6 schematicallyshowstheeffectofapositivePVanomaly(ie,aregionwithanisolated maximumofcyclonicPV)surroundedbyanatmosphereoriginallyatrestwithuniformPV.

ThePVanomalymodifiesthetemperaturefieldandinducesacycloniccirculation.

•Atthecenteroftheanomalythestaticstabilityincreases(theiso-q surfacesbecomecloser together);thereforethestabilitydecreasesaboveandbeneaththePVanomaly.

•ToconservePV,theabsolutevorticityincreasesaboveandbeneaththeanomalyto compensateforthisdecreaseinstability.

FIGURE1.6

Aschematiccross-section,showinganidealizedmodelofthemodificationofthetroposphereassociatedwith anupper-levelcyclonicpotentialvorticityanomaly,whichisreferredtoasadynamicaltropopauseanomaly.