https://ebookmass.com/product/time-limited-existentialtherapy-the-wheel-of-existence-2nd-edition-alison-strasser/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Decision Time Laurence Alison & Neil Shortland

https://ebookmass.com/product/decision-time-laurence-alison-neilshortland/

ebookmass.com

The Existential Crisis of Motherhood Claire Arnold-Baker

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-existential-crisis-of-motherhoodclaire-arnold-baker/

ebookmass.com

The Hike Alison Farrell

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-hike-alison-farrell/ ebookmass.com

Weird Fiction: A Genre Study Michael Cisco

https://ebookmass.com/product/weird-fiction-a-genre-study-michaelcisco/

ebookmass.com

The

Invention of Wings (Mulligan's Mill Book 1) MM Robin

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-invention-of-wings-mulligans-millbook-1-mm-robin-knight/

ebookmass.com

Scottish Presbyterianism and Settler Colonial Politics: Empire of Dissent 1st Edition Valerie Wallace (Auth.)

https://ebookmass.com/product/scottish-presbyterianism-and-settlercolonial-politics-empire-of-dissent-1st-edition-valerie-wallace-auth/

ebookmass.com

Elegies of Chu Chu

https://ebookmass.com/product/elegies-of-chu-chu/

ebookmass.com

Fundamentals of Physical Geography 2nd Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/fundamentals-of-physical-geography-2ndedition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

ATI RN Nutrition 2016 Form A

https://ebookmass.com/product/ati-rn-nutrition-2016-form-a/

ebookmass.com

Digital Makeover: How L'Oréal Put People First to Build a Beauty Tech Powerhouse 1st Edition Béatrice Collin

https://ebookmass.com/product/digital-makeover-how-loreal-put-peoplefirst-to-build-a-beauty-tech-powerhouse-1st-edition-beatrice-collin/

ebookmass.com

Time-Limited Existential Therapy

Time-Limited Existential Therapy

The Wheel of Existence

Second Edition

Alison Strasser With Freddie Strasser

This second edition first published 2022

© 2022 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Edition History

John Wiley & Sons Ltd (1e, 1997)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Alison Strasser to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Offices

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Office

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

The contents of this work are intended to further general scientific research, understanding, and discussion only and are not intended and should not be relied upon as recommending or promoting scientific method, diagnosis, or treatment by physicians for any particular patient. In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of medicines, equipment, and devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions for each medicine, equipment, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of usage and for added warnings and precautions. While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Strasser, Alison, author. | Strasser, Freddie, author.

Title: Time-limited existential therapy : the wheel of existence / Alison Strasser with Freddie Strasser

Other titles: Existential time-limited therapy.

Description: Second edition. | Hoboken, NJ : Wiley-Blackwell, 2022. | Revision of: Existential time-limited therapy / Freddie Strasser and Alison Strasser. 1997. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021043976 (print) | LCCN 2021043977 (ebook) | ISBN 9781118713716 (paperback) | ISBN 9781118713686 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781118713709 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Existential psychotherapy. | Brief psychotherapy.

Classification: LCC RC489.E93 S77 2022(print) | LCC RC489.E93(ebook) | DDC 616.89/147–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021043976

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021043977

Cover Design: Wiley

Cover Image: © Dody Strasser, RBA

Set in 9.5/12.5pt STIXTwoText by Straive, Pondicherry, India

This book is dedicated to my dad, Freddie Strasser, whose wisdom, innovation, and vision, whose passion for the time-limited modular approach, and whose appetite for wheels of every description laid the foundational ideas upon which this book is based.

Thank you for remaining steadfastly by my side as this second edition took shape and for your unswerving belief.

Your Hungarian charm and infectious smile will continue to ripple in all those who have been touched by your irrepressible spirit.

Contents

Foreword ix

Preface xi

Acknowledgements xvii

About the Author xviii

Part I 1

1 Existential and Phenomonological Philosophies and the Wheel of Existence 3

2 Core of the Wheel: Time and Self 14

3 Time in Therapy: The Principal Concepts of Existential Time-Limited Therapy 20

4 Approaches to Time-Limited Therapy 30

Part II 39

Layers and Leaves: Ontologicals and Ontics 41

The Ontological Layer: Universalising 43

5 The Ontological ‘Givens’ 44

Stepping Through the Ontic Leaves: Individualising 54

6 Working with The Phenomenological Process 56

7 Establishing Safety 73

8 Discovering Anxiety 81

9 Revealing the Relationship 93

10 Exploring the Four Worlds 104

11 Clarifying the Worldview 112

12 Working with Paradox and Polarities 123

13 Identifying Choices and Meaning 132

14 Integrating Mind and Body 141

15 Understanding Authenticity 147

Afterword: COVID-19 156

References 162

Index 168

Foreword

All therapy, de facto, is time limited and has a beginning and an end. In this it is very much like human existence. The more we allow ourselves to be aware of the limits of life, the defter we get at using the space and time available to us. It is like this with therapy too: the more we approach it with awareness of its limits and boundaries, the sharper becomes its lens, allowing us to throw a clear light on a person’s difficulties whilst illuminating their possibilities. Time, here too, is of the essence, as it leads us naturally from our memory-laden past, through our present predicaments, towards a future purpose and destination. Throughout the pages of this book our journey in time points the way towards progress, meaning, and understanding.

When Freddie Strasser and his daughter Alison Strasser co-authored their book on time-limited therapy at the end of the 1990s, they had both relatively recently completed their existential training (with me), but had already shown themselves to be prime contributors to the existential approach. In that earlier book I recognised many of the ingredients I had introduced them to, though they had been mixed and prepared in a new way, providing a fresh and original take on existential therapy that foregrounded the important theme of the time-limited nature of our profession.

In this new volume, Alison Strasser has remixed the themes, elegantly updating her vision of time-limited work, displaying her maturity of thought and her professionalism. Here we find a broader spectrum, a more coherent narrative, and a much more sure-footed account of time-limited existential therapy. This is now a clear and carefully worked out guide demonstrating to existential therapists how they can concretely apply these ideas to their everyday practice with their clients. This is a book by a seasoned and talented therapist, who has not only seen hundreds of clients over the intervening decades, but who has created a thriving existential training institute of her own, in Sydney, Australia, and who has taught and supervised many hundreds of trainees over the years.

Foreword x

The experience jumps off the page and is continuously in evidence through the intertwining of theoretical concepts and practical application. There are many vignettes, whose storylines are engaging whilst highlighting the points that matter. There are great summaries of relevant philosophical ideas and of salient practitioners’ work. There are also plenty of original contributions, culminating in a brand-new ‘wheel of existence’, which will speak to existential therapists worldwide.

Alison Strasser has boldly taken up the challenge of revising and reviving a highly successful book, which she wrote together with her late father. Having had the immense pleasure of knowing and working with Freddie Strasser myself, I have no doubt that he would have smiled proudly upon this feat of daughterly pluck and accomplishment. The book will give his own reputation a new lease of life, thus cheating time and death itself in the nicest possible way. Many new readers will now benefit from their joint ideas, and previous readers will note how these ideas have thrived and blossomed, through Alison’s work, over the years. The book is a true testimony to the ripening of life with the passing of time. It will be appreciated on many continents.

Emmy van Deurzen

Preface

The only man who behaved sensibly was my tailor: he took my measure anew every time he saw me, while all the rest went on with their old measurements and expected them to fit me.

George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman (1905)

The first edition of this book, Existential Time Limited Therapy: The Wheel of Existence (Strasser & Strasser, 1997), co-authored by my father, Freddie Strasser, and me, paved a pathway to describing how existential therapy offers an effective approach to brief therapy where ‘it was the certainty of the ending that was identified as the most influential distinguishing factor’ (Lamont, 2012, p. 172). We proposed that time itself is the ‘tool’ that facilitates awareness and the potential for change.

One of the original aims of the first edition was to convey existential philosophy as a vehicle for common sense. Neither my father nor I saw ourselves as experts in existential philosophy; however, we were both stimulated by how the integration of existential and phenomenological philosophies added alternative perspectives and ways of understanding people that related to their concrete living in the world rather than being limited to a psychological perspective. As is probably true for most existential practitioners, we saw ourselves as existential-oriented therapists, signifying that we are informed by numerous ideas and approaches that build on our own personal experiences.

In the first edition, we presented the modular approach where the client was offered 12 sessions with the first 10 sessions as consecutive and the final 2 sessions spread a month apart. A subsequent module of 12 sessions could be discussed and implemented depending on the client’s particular circumstances. Indeed, the discussion itself about continuing or not is one of the hidden gems of this approach in that some clients are adamant about wishing to continue or not. Such responses tend to relate to, and reveal, clients’ attitudes towards themselves and to relationships in general.

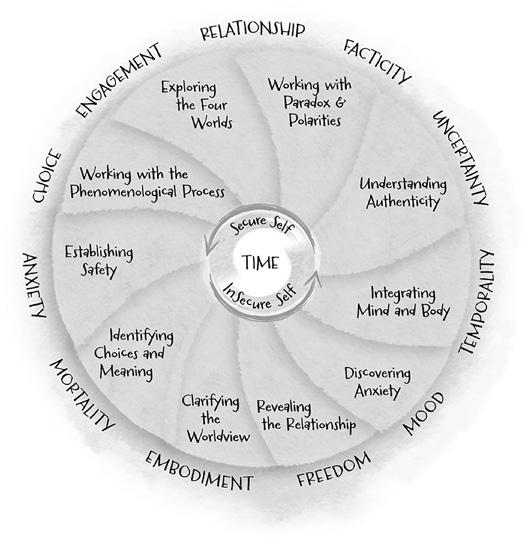

In conjunction with the development of the time-limited modular approach, the first edition introduced two Wheels of Existence: Structure and Process wheels. This was a novel way of understanding existential philosophy and brought to existential psychotherapy a structure, albeit fluid, to delineate the aspects of existential theory and its application to psychotherapy practice. Since existential philosophy is not used overtly with clients but creates the backdrop or framework to inform how the therapist listens, how questions are framed, and how inferences and connections are drawn, the wheels provided an interrelational map. The various components provide a schema for understanding how the different elements of existential philosophy are integrated into the whole experience.

In the years following the publication of the first edition, my father and I lived in different countries, followed different pathways, and diverged in our interests but still continued with our weekly conversations. I began exploring supervision and devised a wheel to encompass the existential ideas that emerged from my doctoral research. My father became fascinated with mediation and also created a series of wheels to further enhance his ideas and to show the existential connections retained in this mediation framework. He developed the ideas along with Paul Randolph (a barrister) into the Alternative Dispute Resolution. Interestingly, although two wheels were introduced in the first edition, very soon only one wheel emerged in each of our individual work.

In 2007, when writing a presentation for the Australasian Existential Society, my father and I developed yet another version of the wheel that united our ideas combining our developing thoughts. And we realised that veiled within the original text was the germ of an idea that, as life is time limited, similarly every psychotherapy session, every group of sessions however contracted, has its limitations of time (Strasser & Strasser, 1997, p. 4). This we understood as reflective of the need to be time aware, irrespective of modality or length of sessions. We had every intention of developing these ideas further into a second edition of time-limited therapy.

However, the time-limited nature of life assaulted my own sense of certainty and predictability with the unexpected and untimely death of my father, forcing me to confront the finitude of his life, taking the wind out of my sails, and leaving me to honour the legacy and continue our work.

When, some years later, Emmy van Deurzen proposed the idea of my writing the second edition on my own, I felt excited to continue my father’s work. I had accessed his ideas about paradox on his computer and discovered some of his case studies. I knew how we would have written this book together, as we had done previously. I would now write to honour his work; I would write as a tribute to him.

Several months on, however, I was still struggling to gather my thoughts and put together any words related to time-limited therapy. I was derailed by my wish to write my own thoughts, worried that I’d be unable to do so on my own and

fearing offending the existential community. Without my father there was no buffer, and yet I wanted to have my voice heard; I was stuck in my own paradox.

This struggle continued until one of my friends insightfully asked me why I was writing. I realised that my intentions were more duty bound than personally motivated. It seemed that my attempts at writing had been in ‘bad faith’.i Of course I’d be finding it hard!

This has not been an easy journey. In time, I began to appreciate that, as the Bible claims, ‘What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun’ (Ecclesiastes 1:9), that no ideas are new, only that our understanding of concepts evolves with our experiences and our ability to challenge and experiment with them. Even if I present what I believe are new ideas in this book, they have evolved from what has been co-created with others, from my many and varied teachers, mentors, colleagues, friends, adversaries, and, of course, my father.

Since the publication of first edition, many other authors and existential practitioners have written about their work and their understanding and integration of existential philosophy. There is a second and possibly even third generation of writers that are widening and also integrating other frameworks and modalities into the space of existential practice. There is the focusing world of Eugene Gendlin (1978) as integrated by such authors as Greg Madison (2010); the Buddhist mindfulness approach as integrated by such authors as Khong (2013) and Nanda (2009); the continuation of Frankl’s (1963) logotherapy with the work of Alfred Längle ( 2015); as well as the humanists such as Kirk Schneider (Schneider & Krug, 2010) and Mick Cooper (Cooper & Mearns, 2005) who have shown how the humanistic tradition is also existential in nature. Research shows that existential therapy is as valid an approach as any other therapy (Correia, Cooper, & Berdondini, 2014). There is a group of therapists, the New Existentialists (Hoffman, 2015), who no longer adhere to the ‘doom and gloom’ perspective that is often associated with French existentialist writing, focusing instead on a positive interpretation of the philosophy and its application. Indeed, we now read about joy and hope, meaning and purpose as an existential tension to their opposites of sadness and despair, meaninglessness and aloneness and about how we can live our life more fully through self-examination and taking more responsibility for our life journey. And my own perspective continues to shift and modify as I undertake further reading, add my own daily experience of working with clients, supervisees, students, colleagues, and am challenged and inspired by the vagaries of life in all its complexities.

I returned to writing this second edition, deciding to put my father firmly up ‘in the attic’ and to give myself the option of choosing consciously when and how to invite him in.

Simultaneously, I realised that my compulsion to complete this task on my own was driven my childhood determination to prove my worth; this contributed to

my stuckness. By staying with the anxiety of my stuckness, I began to understand that to ask for help was not a negation of my independence but potentially a shift towards something new and exciting. And so I chose to ask for help. Jo Silbert has been a friend and fellow therapist for many years. Through her love of language, she shifted into writing and editing articles and books on psychotherapy. With her help, this second edition began to take shape.

My first decision was to consolidate the two Wheels of Existence into one wheel. This new wheel combines the ideas from the original wheels and simultaneously allows for the integration of the philosophical ideas and the essential processes involved in existential practice. Broadly, the Wheel in this edition brings together the concept that our practice is phenomenological while maintaining the existential philosophy as the backdrop that informs our listening, questions, and reflections.

In this second edition, I will expand on the concept of time-aware therapy to reveal that all therapy can be viewed as time limited and discuss the various possibilities of using a time-aware approach in practice to reveal how time can be used as an effective stratagem to enhance and highlight some of the existential human concerns. So, while the modular approach still remains valid, its ideas are transferable to all therapies.

Therapy as time limited fits snugly into an existential perspective in that, in its very essence, therapy mirrors life in all its openings and closures, beginnings and endings, with its final culmination in death. These beginnings and endings of life range from the small and everyday – our waking up in the morning and going to sleep at night, starting and finishing a new project, beginning a new friendship and saying goodbye to others – to the more significant beginning of our birth and ending of our death. We are all being carried forward towards death, a being-untodeath as described by Heidegger (1962). The manner of our approach to how we tackle or manage these beginnings, endings, openings and closures in therapy can mimic how we negotiate life. Hence, the significance of time is tangible in every session.

Time is also implicit in therapy, though usually unspoken, unless either the client or therapist is taking a break, or the end of therapy is nigh. There are numerous theories and approaches to addressing and grasping the meaning of breaks; yet working explicitly with temporality as an existential given gives a richness to time in all its complexity for both the therapist and client to work with.

I tend to work with clients with no fixed end to their therapy, or what is usually defined as open-ended. This is partly due to my original training and also my own preference for working with clients over a longer period. The relationship that is at the crux of existential therapy ebbs and flow over a longer period and builds on an in-depthness that doesn’t always have time to develop within the brief therapy scenario. I build in an ending process so that when it is time for the client to finish,

we negotiate a series of sessions before the final closure. This manner of ending brings out many of the advantages of the time-limited modular approach and the benefits for some clients of working over a longer time period. Later, I discovered that this was similar to Otto Rank’s (1929) concept of time-limited therapy that I shall return to in Chapter 3. As so cogently described by a supervisee who closed her practice using this ‘time-aware and time-limited’ approach, ‘working with the ending was like a dream come true; my clients took up their own baton and truly worked in earnest’.

Yalom (2008) writes about explicitly alluding to death in every session; I propose that our relationship to time is an expansive way of calling attention to endings that might include our relationship to our physical death but is inclusive of all the other beginnings and endings that occur in life. Every session has a start and finish, every day has its morning and night, every job has an induction and termination, and all relationships begin and end. By calling attention to this reality, it allows for the possibility of working with all the intrinsic anxieties, paradoxes, and vulnerabilities highlighted in the modular approach explored in the first edition.

The proposal to bring time-limited awareness to all therapy is about recognising that contextual working situations are diverse, that our circumstances differ, and that, as therapists, we have personal preferences. My work as a supervisor has privileged me with insights into the gamut of the many and varied circumstances, contexts and experiences of my supervisees: therapists and supervisors in private practice; practitioners that work in agencies with a fixed number of client sessions varying from 6 weeks to 6 months; those that permit additional sessions; those that require clients to be referred elsewhere after the maximum sessions are complete. These insights have highlighted how we all need to find our own path, our own voice as therapists. Working with the idea of time and its limitations has its own flexibility and can be used and worked with as seen fit and appropriate by each individual.

In some obvious, some subtle ways, this second edition was in its conception –both during and as soon as the first edition was put to bed – reflecting the notion that speaks directly to one of the existential ideas that time is in constant flow with no beginning or ending. This might appear to be in direct opposition to timelimited therapy which honours the idea that time is limited, thus highlighting another existential ‘given’ that life is peppered with paradoxes. This second edition is an opportunity to extend the original ideas around time in therapy to include a broader spectrum of practitioners and clients. There are many advantages to shorter-term therapy and there are other benefits to working in a more long-term way. The requirements of the client, the orientation of the therapist or the specific agency rules are all taken into account when contracting with the client. In all of these circumstances, understanding and working with time as an

explicit theme can alter the flavour of the therapy. Case studies and client vignettes will be used throughout the book to illustrate and to breathe life into what is often turgid or difficult language to understand. This edition includes new case studies and vignettes as well as those from the original book, namely, ‘Lynn’, one of the studies written by my father which was pivotal in the development of the timelimited modular approach. In this second edition, all of the other case studies are composites and representative of being human.

Much has changed since our writing of the first edition, including my understanding and working definition of time-limited therapy. My own practice as a therapist, supervisor, coach, and trainer continues to inform my understanding and interpretation of existential philosophy. I am indebted to my clients, supervisees, and colleagues for the questions they ask and their inherent courage to question not only themselves but me in any of these roles and positions.

The second edition is written to be inclusive of many of the ideas that were important to my father. I decided to use the pronoun ‘I’ rather than define which ideas and client stories were his and which were mine. This decision was part of my personal process of finding my voice and recognising my father’s influence.

Finally, as my father had, and still has, enormous influence on who I have become and on the way I think and experience life, this second edition honours both his contribution to the world of existential practice as a therapist, coach, and mediator and the immense impact he had on defining the modular time-limited approach. His framework still works and continues to be enormously useful.

Note

i A term used by Jean Paul Sartre (1958) to describe a form of self-deception and avoidance of one’s freedom.

Acknowledgements

I’m deeply grateful to my sisters Carolyn and Yvonne, to my step-daughter Sacha Woodburn, to all my family, friends and colleagues who have supported me in my much longer than anticipated journey in completing this second edition.

I have travelled around the world, sat at many kitchen tables with my trusted laptop and both written, revised, and conversed with my wonderful friends and family; in particular, the tables I remember with warmth are with Nari and Lucia Ghandhi in London, Frank and Sara Megginson in Monaco and other beautiful settings, Peggy Hankey in Seyssel, France, Sal Flynn in Byron Bay, Margalit Barnea in Portugal, Jo and Alex Fok in Tasmania, and Annie Buchner in our COVIDbound holidays in New South Wales, Australia, and a big thank you to Leanda Elliott and Joyce Morgan for their wise counsel and unswerving friendship.

I thank my colleagues who never erred from the firm belief that I would finally hand in the manuscript. In particular, Emmy van Deurzen, Ernesto Spinelli, Greg Madison in the UK and, closer to home, Adam McLean and Lyn Gamwell.

And I thank all my clients and supervisees who inadvertently provided the backdrop and clarity to the existential themes that I was writing about, including their myriad of responses to time, and to Maria Clark for sharing her time and her rich case studies for inclusion in this book.

I acknowledge the calm and insightful support of Jo Silbert who stepped in after the first draft as my editor and mentor; together we cut and dissected chapters, pages, and ideas and shaped them into the current coherent creation.

Finally, my thanks go to my husband Rob Woodburn who was a surreptitious existential thinker, only revealing later in our relationship that he had studied existential philosophy as an undergraduate. As a writer, he patiently read and edited the first draft of this book, asking awkward but poignant and useful questions. The two most significant men in my life, Rob and my father, Freddy both died within 10 years of each other, handing over the baton to my humble and nervous hands.

About the Author

Alison Strasser DProf (Psychotherapy & Counselling), MA, BA Hons

Alison is a practising psychotherapist, coach, and supervisor. She is also an educator with a passion for imparting how existential themes can be integrated into every therapeutic approach. She was instrumental in creating the existential curriculum for many counselling and psychotherapy trainings in Australia and founded Centre for Existential Practice in 2008. Her doctorate focused on the process of supervision, work that led to a framework for supervisor training, now a major component of CEP’s annual programme.

Part I

Existential and Phenomonological Philosophies and the Wheel of Existence

My freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and . . . surround myself with obstacles . . . The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self of the chains that shackle the spirit.

Igor Stravinski, Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons (1970)

Existentialism and Phenomenology Overview

Existentialism and phenomenology are different and yet complementary philosophies that attempt to understand what it means to be human. In simple terms, existentialism focuses on human existence, reflecting on the issues of what it is to be human, while phenomenology concerns itself with how human beings subjectively interpret their existence. These philosophies stem not from a traditional, objective, rational, scientific focus or impetus but from an examination of how humans understand themselves in the midst of their lived experience.

The word ‘existence’ has its roots in the Latin word ex-istere – translated variously as ‘to stand out’, ‘to emerge’, ‘to proceed forward in a continuous process’.

Rollo May, the distinguished American protagonist of existential philosophy, defined this existential approach to understanding the human condition in his book The Discovery of Being:

For the very essence of this approach is that it seeks to analyse and portray the human being – whether in art or literature or philosophy or psychology –on a level which undercuts the old dilemma of materialism versus 1

Existential Therapy: The Wheel of Existence, Second Edition. Alison Strasser.

idealism. Existentialism, in short, is the endeavour to understand man1 by cutting below the cleavage between subject and object that has bedevilled Western thought and science since shortly after the Renaissance. (May, 1983, p. 49)

Existential philosophy is concerned with the science of being – with ontology (Gk ontos, ‘being’). It examines the attitudes we adopt towards being and what we can do about it. Existential philosophy observes that each individual makes his or her own unique pathway in the world, that each of us will experience our own existence in our own distinctive manner. Simultaneously, each individual exists in a relational or co-constituted mode to others and to the world. In other words, as soon as we exist we are inexorably connected to other people, objects and even ideas.

Kierkegaard, the grandfather of existentialist philosophy, explored the anxiety and aloneness humans experience as they struggle in their attempts to find their own truth, their personal freedom, against the backdrop of the ‘shoulds’ and ‘oughts’ that life inevitably demands. Heidegger pertinently asked, ‘What is it to be human?’ and spent his life’s work defining and redefining both his questions and answers, emerging with the concept that humans are inextricably connected to the world, are perpetually in a state of ‘being-in-this-world’, known as Dasein (Heidegger, 1962). Similarly, we are always ‘comporting’ or choosing how we act in the world at the same time as the world interacts with us.

Many people associate existential philosophy with complicated ideas and a leaning towards pessimism. They hear words such as ‘death’, ‘isolation’, and ‘meaninglessness’, without realising that these concepts form only a part of a richer and more complex whole. It is just as significant, for example, to explore hope as it is to examine despair. The polarity of existential themes creates the constant tension between life and death, meaning and meaninglessness, isolation and relationship. Existence is about understanding and living within these constant tensions.

Phenomenology, on the other hand, concerns itself with subjectivity, with how human beings interpret things to themselves (Husserl, 1977) as opposed to the natural science framework that seeks to find objective truth. The importance of phenomenological exploration is that it excludes this objective reality and instead seeks a subjective explanation of the individual’s relationships with objects, others, and his or her sense of being.

The Wheel of Existence

The Wheel is used as a diagrammatic representation of the interplay between key existential and phenomenological concepts and as a philosophical attitude when working with clients. It is versatile framework in that it can be used as a specific

Source: Alison Strasser

structure for teaching but also creates a background frame that can be drawn upon when reflecting upon a client either in the session or later in supervision.

In brief, the Wheel’s outer layer depicts existential or ‘ontological’ phenomena, the concerns or ‘givens’ common to all human beings universally.

Radiating from the fulcrum of the Wheel is the next layer, a series of 10 segments or ‘leaves’, which together constitute the essence of individual experience and their attitudes or relationship to the ontological ‘givens’. These leaves are referred to as the ‘ontic’ layer and give credence to a subjective and personal ‘ontic’ experience which differs with each individual and which more closely resembles the concerns of phenomenology.

The self, which can be considered to be in a constant state of flux, shifting between one’s experiences of security and insecurity, occupies the outer section of the core.

At the core of the Wheel of Existence is time, an existential given that permeates all our lives from birth to death and beyond.

The Wheel is a schema for understanding how the different rudiments of existential philosophy are integrated into a whole; it seeks to show how all the above elements both interact with and influence each other, all contributing to the individual’s experience of being-in-the-world and to our worldview. The structure of

the Wheel highlights the existential–phenomenological hypothesis that all issues always interconnect and express themselves throughout all facets of individuals’ relationships with the world. As such, the Wheel parallels existential philosophy in viewing the human being as a unified entity rather than split into divisions of mind, thoughts, body, and emotions. It follows that what a client focuses on at any point in time will be connected to many of their other concerns, thus paralleling phenomenology. In keeping with this thinking, the following chapters in which these elements or ‘leaves’ are described do not necessarily follow the clockwise or even anticlockwise direction of the Wheel.

Of course, the paradox is that existentialism by its very nature cannot provide anybody with a framework that guarantees safeguards or stability. If the Wheel is taken too literally or becomes too technical or rule driven, it can easily become counterproductive. Using a loose but clearly defined structure, however, can also highlight the uncertainties of being thrown into this world and the certainty of leaving it, which Deurzen confirms: ‘Although an existential approach [to psychotherapy] is essentially non-technological, I also believe that one needs some methods, some parameters, some framework, in order to retain one’s independence and clarity of thinking’ (1988, p. 6).

Universalising: The Ontological Layer

The outer edge of the Wheel of Existence in the diagram encompasses what are known as the ontological or existential concerns of existence. These ‘ontological’ characteristics are the elements of being human that are common to all humankind. They are aspects of being human that we cannot change; they are an intrinsic feature to all humans. In existential terminology, they are called ‘givens’ or ‘universals’, meaning facts that we are either born with or encounter during life. Residing in the background of our everyday living, I think about these ontological givens as the relentless ‘hum’. These ‘hums’ are constant and move in and out of immediate awareness as events in life unfold. For Heidegger, this ontological aspect is at the heart of his understanding that certain aspects are manifest and inescapable and are the nature of being human (Heidegger, 1962). Various authors have described a range of different themes of existence as ‘ontological’. The concerns chosen within this Wheel, and discussed below, are the ontological givens that arise most commonly in my current work and will be discussed in detail in Chapter 5. Other therapists might focus on other givens that give credence to their practice.

The Ontological Givens

● Relationship in the ontological sense describes how a human being is always in a state of relationship not only to others but also to oneself and to the overall