https://ebookmass.com/product/the-temporal-lobe-gabrielemiceli/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Temporal Gifts Whitney Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/temporal-gifts-whitney-hill/

ebookmass.com

Temporal Gifts Whitney Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/temporal-gifts-whitney-hill-2/

ebookmass.com

The Black Mediterranean: Bodies, Borders and Citizenship Gabriele Proglio

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-black-mediterranean-bodies-bordersand-citizenship-gabriele-proglio/

ebookmass.com

Gone Like Yesterday: A Novel Janelle M. Williams

https://ebookmass.com/product/gone-like-yesterday-a-novel-janelle-mwilliams/

ebookmass.com

The Bone Track Sara E. Johnson https://ebookmass.com/product/the-bone-track-sara-e-johnson/

ebookmass.com

Sweet Wild of Mine Laurel Kerr

https://ebookmass.com/product/sweet-wild-of-mine-laurel-kerr-2/

ebookmass.com

Introduction to Dependent Types with Idris: Encoding Program Proofs in Types 1st Edition Boro Sitnikovski https://ebookmass.com/product/introduction-to-dependent-types-withidris-encoding-program-proofs-in-types-1st-edition-boro-sitnikovski-2/

ebookmass.com

Pearl of the Desert: A History of Palmyra Rubina Raja

https://ebookmass.com/product/pearl-of-the-desert-a-history-ofpalmyra-rubina-raja/

ebookmass.com

Staging Trauma 1st ed. Edition Miriam Haughton https://ebookmass.com/product/staging-trauma-1st-ed-edition-miriamhaughton/

ebookmass.com

The teachings of the Jehovah's Witnesses : [a comparison of the tenets of the Jehovah's Witnesses with traditional Christian doctrines] Gerstner

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-teachings-of-the-jehovahs-witnessesa-comparison-of-the-tenets-of-the-jehovahs-witnesses-with-traditionalchristian-doctrines-gerstner/ ebookmass.com

ELSEVIER

Radarweg29,POBox211,1000AEAmsterdam,Netherlands TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates

Copyright©2022ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearanceCenter andtheCopyrightLicensingAgencycanbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher(other than asmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroadenour understanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingandusingany information,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationormethodsthey shouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessional responsibility.

Withrespecttoanydrugorpharmaceuticalproductsidentified,readersareadvisedtocheckthemostcurrent informationprovided(i)onproceduresfeaturedor(ii)bythemanufacturerofeachproducttobeadministered,to verifytherecommendeddoseorformula,themethodanddurationofadministration,andcontraindications.Itis theresponsibilityofpractitioners,relyingontheirownexperienceandknowledgeoftheirpatients,tomake diagnoses,todeterminedosagesandthebesttreatmentforeachindividualpatient,andtotakeallappropriate safetyprecautions.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditorsassumeanyliability foranyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceorotherwise,or fromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

ISBN:978-0-12-823493-8

ForinformationonallElsevierpublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: Nikki Levy

EditorialProjectManager: KristiAnderson

ProductionProjectManager: PunithavathyGovindaradjane

CoverDesigner: MatthewLimbert

HandbookofClinicalNeurology3rdSeries

Availabletitles

Vol.79,Thehumanhypothalamus:Basicandclinicalaspects,PartI,D.F.Swaab,ed.ISBN9780444513571

Vol.80,Thehumanhypothalamus:Basicandclinicalaspects,PartII,D.F.Swaab,ed.ISBN9780444514905

Vol.81,Pain,F.CerveroandT.S.Jensen,eds.ISBN9780444519016

Vol.82,Motorneuronedisordersandrelateddiseases,A.A.EisenandP.J.Shaw,eds.ISBN9780444518941

Vol.83,Parkinson’sdiseaseandrelateddisorders,PartI,W.C.KollerandE.Melamed,eds.ISBN9780444519009

Vol.84,Parkinson’sdiseaseandrelateddisorders,PartII,W.C.KollerandE.Melamed,eds.ISBN9780444528933

Vol.85,HIV/AIDSandthenervoussystem,P.PortegiesandJ.Berger,eds.ISBN9780444520104

Vol.86,Myopathies,F.L.MastagliaandD.HiltonJones,eds.ISBN9780444518996

Vol.87,Malformationsofthenervoussystem,H.B.SarnatandP.Curatolo,eds.ISBN9780444518965

Vol.88,Neuropsychologyandbehaviouralneurology,G.GoldenbergandB.C.Miller,eds.ISBN9780444518972

Vol.89,Dementias,C.DuyckaertsandI.Litvan,eds.ISBN9780444518989

Vol.90,Disordersofconsciousness,G.B.YoungandE.F.M.Wijdicks,eds.ISBN9780444518958

Vol.91,Neuromuscularjunctiondisorders,A.G.Engel,ed.ISBN9780444520081 Vol.92,Stroke – PartI:Basicandepidemiologicalaspects,M.Fisher,ed.ISBN9780444520036 Vol.93,Stroke – PartII:Clinicalmanifestationsandpathogenesis,M.Fisher,ed.ISBN9780444520043 Vol.94,Stroke – PartIII:Investigationsandmanagement,M.Fisher,ed.ISBN9780444520050 Vol.95,Historyofneurology,S.Finger,F.BollerandK.L.Tyler,eds.ISBN9780444520081 Vol.96,Bacterialinfectionsofthecentralnervoussystem,K.L.RoosandA.R.Tunkel,eds.ISBN9780444520159 Vol.97,Headache,G.NappiandM.A.Moskowitz,eds.ISBN9780444521392 Vol.98,SleepdisordersPartI,P.MontagnaandS.Chokroverty,eds.ISBN9780444520067 Vol.99,SleepdisordersPartII,P.MontagnaandS.Chokroverty,eds.ISBN9780444520074 Vol.100,Hyperkineticmovementdisorders,W.J.WeinerandE.Tolosa,eds.ISBN9780444520142 Vol.101,Musculardystrophies,A.AmatoandR.C.Griggs,eds.ISBN9780080450315 Vol.102,Neuro-ophthalmology,C.KennardandR.J.Leigh,eds.ISBN9780444529039 Vol.103,Ataxicdisorders,S.H.SubramonyandA.Durr,eds.ISBN9780444518927 Vol.104,Neuro-oncologyPartI,W.GrisoldandR.Sofietti,eds.ISBN9780444521385 Vol.105,Neuro-oncologyPartII,W.GrisoldandR.Sofietti,eds.ISBN9780444535023 Vol.106,Neurobiologyofpsychiatricdisorders,T.SchlaepferandC.B.Nemeroff,eds.ISBN9780444520029 Vol.107,EpilepsyPartI,H.StefanandW.H.Theodore,eds.ISBN9780444528988 Vol.108,EpilepsyPartII,H.StefanandW.H.Theodore,eds.ISBN9780444528995 Vol.109,Spinalcordinjury,J.VerhaagenandJ.W.McDonaldIII,eds.ISBN9780444521378 Vol.110,Neurologicalrehabilitation,M.BarnesandD.C.Good,eds.ISBN9780444529015 Vol.111,PediatricneurologyPartI,O.Dulac,M.LassondeandH.B.Sarnat,eds.ISBN9780444528919 Vol.112,PediatricneurologyPartII,O.Dulac,M.LassondeandH.B.Sarnat,eds.ISBN9780444529107 Vol.113,PediatricneurologyPartIII,O.Dulac,M.LassondeandH.B.Sarnat,eds.ISBN9780444595652 Vol.114,Neuroparasitologyandtropicalneurology,H.H.Garcia,H.B.TanowitzandO.H.DelBrutto,eds. ISBN9780444534903

Vol.115,Peripheralnervedisorders,G.SaidandC.Krarup,eds.ISBN9780444529022 Vol.116,Brainstimulation,A.M.LozanoandM.Hallett,eds.ISBN9780444534972 Vol.117,Autonomicnervoussystem,R.M.BuijsandD.F.Swaab,eds.ISBN9780444534910 Vol.118,Ethicalandlegalissuesinneurology,J.L.BernatandH.R.Beresford,eds.ISBN9780444535016 Vol.119,NeurologicaspectsofsystemicdiseasePartI,J.BillerandJ.M.Ferro,eds.ISBN9780702040863 Vol.120,NeurologicaspectsofsystemicdiseasePartII,J.BillerandJ.M.Ferro,eds.ISBN9780702040870 Vol.121,NeurologicaspectsofsystemicdiseasePartIII,J.BillerandJ.M.Ferro,eds.ISBN9780702040887 Vol.122,Multiplesclerosisandrelateddisorders,D.S.Goodin,ed.ISBN9780444520012 Vol.123,Neurovirology,A.C.TselisandJ.Booss,eds.ISBN9780444534880 Vol.124,Clinicalneuroendocrinology,E.Fliers,M.KorbonitsandJ.A.Romijn,eds.ISBN9780444596024 Vol.125,Alcoholandthenervoussystem,E.V.SullivanandA.Pfefferbaum,eds.ISBN9780444626196 Vol.126,Diabetesandthenervoussystem,D.W.ZochodneandR.A.Malik,eds.ISBN9780444534804 Vol.127,TraumaticbraininjuryPartI,J.H.GrafmanandA.M.Salazar,eds.ISBN9780444528926 Vol.128,TraumaticbraininjuryPartII,J.H.GrafmanandA.M.Salazar,eds.ISBN9780444635211

Vol.129,Thehumanauditorysystem:Fundamentalorganizationandclinicaldisorders,G.G.CelesiaandG.Hickok,eds. ISBN9780444626301

Vol.130,Neurologyofsexualandbladderdisorders,D.B.VodušekandF.Boller,eds.ISBN9780444632470

Vol.131,Occupationalneurology,M.LottiandM.L.Bleecker,eds.ISBN9780444626271

Vol.132,Neurocutaneoussyndromes,M.P.IslamandE.S.Roach,eds.ISBN9780444627025

Vol.133,Autoimmuneneurology,S.J.PittockandA.Vincent,eds.ISBN9780444634320

Vol.134,Gliomas,M.S.BergerandM.Weller,eds.ISBN9780128029978

Vol.135,NeuroimagingPartI,J.C.MasdeuandR.G.González,eds.ISBN9780444534859

Vol.136,NeuroimagingPartII,J.C.MasdeuandR.G.González,eds.ISBN9780444534866

Vol.137,Neuro-otology,J.M.FurmanandT.Lempert,eds.ISBN9780444634375

Vol.138,Neuroepidemiology,C.Rosano,M.A.IkramandM.Ganguli,eds.ISBN9780128029732 Vol.139,Functionalneurologicdisorders,M.Hallett,J.StoneandA.Carson,eds.ISBN9780128017722

Vol.140,CriticalcareneurologyPartI,E.F.M.WijdicksandA.H.Kramer,eds.ISBN9780444636003

Vol.141,CriticalcareneurologyPartII,E.F.M.WijdicksandA.H.Kramer,eds.ISBN9780444635990

Vol.142,Wilsondisease,A.CzłonkowskaandM.L.Schilsky,eds.ISBN9780444636003

Vol.143,Arteriovenousandcavernousmalformations,R.F.Spetzler,K.MoonandR.O.Almefty,eds.ISBN9780444636409

Vol.144,Huntingtondisease,A.S.FeiginandK.E.Anderson,eds.ISBN9780128018934 Vol.145,Neuropathology,G.G.KovacsandI.Alafuzoff,eds.ISBN9780128023952 Vol.146,Cerebrospinalfluidinneurologicdisorders,F.Deisenhammer,C.E.TeunissenandH.Tumani,eds. ISBN9780128042793

Vol.147,NeurogeneticsPartI,D.H.Geschwind,H.L.PaulsonandC.Klein,eds.ISBN9780444632333 Vol.148,NeurogeneticsPartII,D.H.Geschwind,H.L.PaulsonandC.Klein,eds.ISBN9780444640765 Vol.149,Metastaticdiseasesofthenervoussystem,D.SchiffandM.J.vandenBent,eds.ISBN9780128111611 Vol.150,Brainbankinginneurologicandpsychiatricdiseases,I.HuitingaandM.J.Webster,eds.ISBN9780444636393 Vol.151,Theparietallobe,G.VallarandH.B.Coslett,eds.ISBN9780444636225 Vol.152,TheneurologyofHIVinfection,B.J.Brew,ed.ISBN9780444638496 Vol.153,Humanpriondiseases,M.PocchiariandJ.C.Manson,eds.ISBN9780444639455 Vol.154,Thecerebellum:Fromembryologytodiagnosticinvestigations,M.MantoandT.A.G.M.Huisman,eds. ISBN9780444639561 Vol.155,Thecerebellum:Disordersandtreatment,M.MantoandT.A.G.M.Huisman,eds.ISBN9780444641892 Vol.156,Thermoregulation:FrombasicneurosciencetoclinicalneurologyPartI,A.A.Romanovsky,ed.ISBN9780444639127 Vol.157,Thermoregulation:FrombasicneurosciencetoclinicalneurologyPartII,A.A.Romanovsky,ed.ISBN9780444640741

Vol.158,Sportsneurology,B.HainlineandR.A.Stern,eds.ISBN9780444639547

Vol.159,Balance,gait,andfalls,B.L.DayandS.R.Lord,eds.ISBN9780444639165

Vol.160,Clinicalneurophysiology:Basisandtechnicalaspects,K.H.LevinandP.Chauvel,eds.ISBN9780444640321

Vol.161,Clinicalneurophysiology:Diseasesanddisorders,K.H.LevinandP.Chauvel,eds.ISBN9780444641427

Vol.162,Neonatalneurology,L.S.DeVriesandH.C.Glass,eds.ISBN9780444640291

Vol.163,Thefrontallobes,M.D’EspositoandJ.H.Grafman,eds.ISBN9780128042816

Vol.164,Smellandtaste,RichardL.Doty,ed.ISBN9780444638557

Vol.165,Psychopharmacologyofneurologicdisease,V.I.ReusandD.Lindqvist,eds.ISBN9780444640123

Vol.166,Cingulatecortex,B.A.Vogt,ed.ISBN9780444641960

Vol.167,Geriatricneurology,S.T.DeKoskyandS.Asthana,eds.ISBN9780128047668

Vol.168,Brain-computerinterfaces,N.F.RamseyandJ.delR.Millán,eds.ISBN9780444639349

Vol.169,Meningiomas,PartI,M.W.McDermott,ed.ISBN9780128042809

Vol.170,Meningiomas,PartII,M.W.McDermott,ed.ISBN9780128221983

Vol.171,Neurologyandpregnancy:Pathophysiologyandpatientcare,E.A.P.Steegers,M.J.CipollaandE.C.Miller,eds. ISBN9780444642394

Vol.172,Neurologyandpregnancy:Neuro-obstetricdisorders,E.A.P.Steegers,M.J.CipollaandE.C.Miller,eds. ISBN9780444642400

Vol.173,Neurocognitivedevelopment:Normativedevelopment,A.Gallagher,C.Bulteau,D.CohenandJ.L.Michaud,eds. ISBN9780444641502

Vol.174,Neurocognitivedevelopment:Disordersanddisabilities,A.Gallagher,C.Bulteau,D.CohenandJ.L.Michaud,eds. ISBN9780444641489

Vol.175,Sexdifferencesinneurologyandpsychiatry,R.Lanzenberger,G.S.Kranz,andI.Savic,eds.ISBN9780444641236 Vol.176,Interventionalneuroradiology,S.W.HettsandD.L.Cooke,eds.ISBN9780444640345

Vol.177,Heartandneurologicdisease,J.Biller,ed.ISBN9780128198148

Vol.178,Neurologyofvisionandvisualdisorders,J.J.S.BartonandA.Leff,eds.ISBN9780128213773

Vol.179,Thehumanhypothalamus:Anteriorregion,D.F.Swaab,F.Kreier,P.J.Lucassen,A.SalehiandR.M.Buijs,eds. ISBN9780128199756

Vol.180,Thehumanhypothalamus:Middleandposteriorregion,D.F.Swaab,F.Kreier,P.J.Lucassen,A.SalehiandR.M.Buijs, eds.ISBN9780128201077

Vol.181,Thehumanhypothalamus:Neuroendocrinedisorders,D.F.Swaab,R.M.Buijs,P.J.Lucassen,A.SalehiandF.Kreier, eds.ISBN9780128206836

Vol.182,Thehumanhypothalamus:Neuropsychiatricdisorders,D.F.Swaab,R.M.Buijs,F.Kreier,P.J.Lucassen,andA.Salehi, eds.ISBN9780128199732

Vol.183,Disordersofemotioninneurologicdisease,K.M.HeilmanandS.E.Nadeau,eds.ISBN9780128222904

Vol.184,Neuroplasticity:Frombenchtobedside,A.Quartarone,M.F.Ghilardi,andF.Boller,eds.ISBN9780128194102

Vol.185,Aphasia,A.E.HillisandJ.Fridriksson,eds.ISBN9780128233849

Vol.186,Intraoperativeneuromonitoring,M.R.NuwerandD.B.MacDonald,eds.ISBN9780128198261

Allvolumesinthe3rdSeriesofthe HandbookofClinicalNeurology arepublishedelectronically, onScienceDirect: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/handbooks/00729752

HANDBOOKOFCLINICAL NEUROLOGY SeriesEditors MICHAELJ.AMINOFF,FRANÇOISBOLLER,ANDDICKF.SWAAB

VOLUME187 Contributors K.Amunts

InstituteofNeuroscienceandMedicine,INM-1, ResearchCentreJuelich,Juelich;C&OVogtInstitutefor BrainResearch,UniversityHospitalD€ usseldorf, MedicalFaculty,Heinrich-HeineUniversity,D€ usseldorf, Germany

P.Bartolomeo

SorbonneUniversite,InstitutduCerveau-ParisBrain Institute-ICM,INSERM,CNRS,APHP,H^ opitaldela PitieSalp^ etrière,Paris,France

J.J.S.Barton

DivisionofNeuro-ophthalmology,Departmentsof Medicine(Neurology),OphthalmologyandVisual Sciences,Psychology,UniversityofBritishColumbia, Vancouver,BC,Canada

S.Benetti

CenterforMind/BrainSciences-CIMeC,Universityof Trento,Trento,Italy

F.Bielle

SorbonneUniversite,INSERM,CNRS,UMRS1127, ParisBrainInstitute,ICM;NeuropathologyDepartment, H^ opitauxUniversitairesLaPitieSalp^ etrière-Charles Foix,AP-HP,Paris,France

C.G.Bien

DepartmentofEpileptology(KrankenhausMara), BielefeldUniversity,Bielefeld;LaboratoryKrone,Bad Salzuflen,Germany

S.Boluda

SorbonneUniversite,INSERM,CNRS,UMRS1127, ParisBrainInstitute,ICM;NeuropathologyDepartment, H^ opitauxUniversitairesLaPitieSalp^ etrière-Charles Foix,AP-HP,Paris,France

V.Borghesani

Centrederecherchedel'Institutuniversitairedegeriatrie deMontreal;DepartmentofPsychology,Universitede Montreal,Montreal,QC,Canada

D.Bottari

IMTSchoolforAdvancedStudiesLucca,Lucca, Italy

M.Bowren,Jr.

DivisionofNeuropsychologyandCognitive Neuroscience,DepartmentsofNeurologyand PsychologicalandBrainSciences,UniversityofIowa, IowaCity,IA,UnitedStates

A.Caccia

CenterforMind/BrainSciences-CIMeC,Universityof Trento,Rovereto;DepartmentofPsychology,University ofMilano-Bicocca,Milan,Italy

F.Cacciamani

BordeauxPopulationHealth,UniversityofBordeaux, Bordeaux,France

G.A.Carlesimo

DepartmentofSystemsMedicine,TorVergata University;ClinicalandBehavioralNeurology Laboratory,I.R.C.C.S.SantaLuciaFoundation,Rome, Italy

M.Catani

Natbrainlab,DepartmentofForensicand NeurodevelopmentalSciences;Departmentof NeuroimagingSciences,InstituteofPsychiatry, PsychologyandNeuroscience,London,United Kingdom

S.W.C.Chang

DepartmentofPsychology;Interdepartmental NeuroscienceProgram,YaleUniversity,NewHaven, CT,UnitedStates

S.Clemenceau

DepartmentofNeurosurgery,LaPitie-Salp^ etrière UniversityHospital,Paris,France

L.Cohen

ParisBrainInstitute,H^ opitaldelaPitie-Salp^ etrière, Paris,France

O.Collignon

CenterforMind/BrainSciences-CIMeC,Universityof Trento,Trento,Italy;InstituteforResearchin PsychologyandNeuroscience,FacultyofPsychology andEducationalScience,UCLouvain,Louvain-laNeuve,Belgium

L.Cousyn

AP-HP,DepartmentofNeurologyandDepartmentof ClinicalNeurophysiology,EpilepsyandEEGUnit, ReferenceCenterforRareEpilepsies,Pitie-Salp^ etrière Hospital;SorbonneUniversite,ParisBrainInstitute, Team “DynamicsofNeuronalNetworksandNeuronal Excitability ”,Paris,France

V.deAguiar

CenterforLanguageandCognitionGroningen; DepartmentofNeurolinguisticsandLanguage Development,UniversityofGroningen,Groningen,The Netherlands

J.DeLeon

MemoryandAgingCenter,DepartmentofNeurology; DepartmentofNeurology,DyslexiaCenter,University ofCalifornia,SanFrancisco,CA,UnitedStates

M.Denos

RehabilitationUnit,NeurosciencesDepartment,H^ opital delaPitie-Salp^ etrière,Paris,France

J.Domínguez-Borràs

DepartmentofClinicalPsychologyandPsychobiology &InstituteofNeurosciences,UniversityofBarcelona, Barcelona,Spain

F.Doricchi

DepartmentofPsychology, “LaSapienza” University; LaboratoryofNeuropsychologyofAttention,I.R.C.C.S. SantaLuciaFoundation,Rome,Italy

V.Frazzini

AP-HP,DepartmentofNeurologyandDepartmentof ClinicalNeurophysiology,EpilepsyandEEGUnit, ReferenceCenterforRareEpilepsies,Pitie-Salp^ etrière Hospital;SorbonneUniversite,ParisBrainInstitute, Team “DynamicsofNeuronalNetworksandNeuronal Excitability ”,Paris,France

M.L.Gorno-Tempini

MemoryandAgingCenter,DepartmentofNeurology; DepartmentofNeurology,DyslexiaCenter,University ofCalifornia,SanFrancisco,CA,UnitedStates

A.E.Hillis

DepartmentofNeurology,JohnsHopkinsUniversity SchoolofMedicine,Baltimore,MD,UnitedStates

J.Kaminski

DivisionofNeuropsychologyandCognitive Neuroscience,DepartmentsofNeurologyand PsychologicalandBrainSciences,UniversityofIowa, IowaCity,IA,UnitedStates

O.Kedo InstituteofNeuroscienceandMedicine,INM-1, ResearchCentreJuelich,Juelich,Germany

B.Z.Mahon

DepartmentofPsychology,CarnegieMellonUniversity, Pittsburgh,PA,UnitedStates

K.Manzel

DivisionofNeuropsychologyandCognitive Neuroscience,DepartmentsofNeurologyand PsychologicalandBrainSciences,UniversityofIowa, IowaCity,IA,UnitedStates

R.C.Martin

DepartmentofPsychologicalSciences,RiceUniversity, Houston,TX,UnitedStates

B.Mathon

DepartmentofNeurosurgery,LaPitie-Salp^ etrière UniversityHospital;SorbonneUniversity;ParisBrain Institute,Paris,France

O.C.Meisner

DepartmentofPsychology;Interdepartmental NeuroscienceProgram,YaleUniversity,NewHaven, CT,UnitedStates

G.Miceli CenterforMind/BrainSciences-CIMeC,Universityof Trento,Rovereto;CentroInterdisciplinareLinceo ‘Beniamino Segre’—AccademiadeiLincei,Rome,Italy

R.Migliaccio

ParisBrainInstitute,INSERMU1127;Departmentof Neurology,Institutdelamemoireetdelamaladie d’Alzheimer,H^ opitaldelaPitie-Salp^ etrière,Paris, France

A.Nair

DepartmentofPsychology,YaleUniversity,NewHaven, CT,UnitedStates

V.Navarro

AP-HP,DepartmentofNeurologyandDepartmentof ClinicalNeurophysiology,EpilepsyandEEGUnit, ReferenceCenterforRareEpilepsies,Pitie-Salp^ etrière Hospital;SorbonneUniversite,ParisBrainInstitute, Team “DynamicsofNeuronalNetworksandNeuronal Excitability ”,Paris,France

C.Papagno

CenterforMind/BrainSciences-CIMeCandCenterfor NeurocognitiveRehabilitation,UniversityofTrento, Rovereto,Italy

F.Pavani

CenterforMind/BrainSciences-CIMeC,Universityof Trento,Rovereto,Italy

S.Pollmann

DepartmentofPsychologyandCenterforBehavioral BrainSciences,Otto-von-Guericke-University, Magdeburg,Germany

A.Rofes

CenterforLanguageandCognitionGroningen; DepartmentofNeurolinguisticsandLanguage Development,UniversityofGroningen,Groningen, TheNetherlands

S.Samson

DepartmentofPsychology,UniversityofLille,Lille; EpilepsyUnit,NeurosciencesDepartment,H^ opitaldela Pitie-Salp^ etrière,Paris,France

T.S€ ark€ am € o

DepartmentofPsychologyandLogopedics,University ofHelsinki,Helsinki,Finland

W.X.Schneider

DepartmentofPsychologyandCenterforCognitive InteractionTechnology,BielefeldUniversity,Bielefeld, Germany

D.Seilhean

SorbonneUniversite,INSERM,CNRS,UMRS1127, ParisBrainInstitute,ICM;NeuropathologyDepartment, H^ opitauxUniversitairesLaPitieSalp^ etrière-Charles Foix,AP-HP,Paris,France

C.Semenza DepartmentofNeuroscience,PadovaNeuroscience Center,UniversityofPadova,Padova,Italy

A.J.Sihvonen

SchoolofHealthandRehabilitationSciences, QueenslandAphasiaResearchCentre,TheUniversityof Queensland,Herston,QLD,Australia;Departmentof PsychologyandLogopedics,UniversityofHelsinki, Helsinki,Finland

A.Spagna DepartmentofPsychology,ColumbiaUniversity,New YorkCity,NY,UnitedStates

D.Tranel

DivisionofNeuropsychologyandCognitive Neuroscience,DepartmentsofNeurologyand PsychologicalandBrainSciences,UniversityofIowa, IowaCity,IA,UnitedStates

D.M.Ubellacker DepartmentofNeurology,JohnsHopkinsUniversity SchoolofMedicine,Baltimore,MD,UnitedStates

P.Vuilleumier

DepartmentofNeuroscienceandCenterforAffective Sciences,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva,Switzerland

Q.Yue DepartmentofPsychology,VanderbiltUniversity, Nashville,TN,UnitedStates

D.Zachlod InstituteofNeuroscienceandMedicine,INM-1, ResearchCentreJuelich,Juelich,Germany

Preface Thisvolumeofthe HandbookofClinicalNeurology offersclinicalandresearchprofessionalsinthefieldof neuroscienceanoverviewandupdateoncurrenthypothesesregardingthecorrelationsbetweenthetemporallobe andnormalandpathologicbehavior.

Anatomically,thetemporallobeisdefinedbyitslocationventraltotheSylvianfissure,occupyingthemiddlecranial fossa.Likeotherbrainlobes,itisnotafunctionallyunitarystructure.Themultiplerolesofdistincttemporalregionsare definedbytheirconnectivitywithotherbrainsystems,suchastheperisylvianlanguagenetworksandthefrontoparietal attentionsystems,andbythesensory(visual,auditory,andolfactory)inputstheyreceive.Themedial,evolutionarily moreancientportionsofthetemporallobeplayimportantrolesinmemory,emotion,andsocialcognition.

Inthepresentvolume,SectionI(Chapters1 and 2)laystheanatomicfoundationsfortheissuesdiscussedinthe following chapters.Itprovidesahistoricalperspectiveandcutting-edgeupdatesonthecytoarchitecturalorganization ofthetemporallobeandonitsconnectionswithotherstructuresofthecentralnervoussystem.

SectionII(Chapters3–22)providesanoverviewoftheroleofthetemporallobeinauditoryprocessing,visual perception, visuospatialprocessing,auditoryandvisuallanguagecomprehensionandproduction,facerecognition, socialcognition,emotion,andmemoryprocesses.Eachchapterreviewsavailableevidenceontheclinicalpictures thatemergefollowingdamagetothetemporallobe(auditoryagnosia,amusia,disordersofauditory/spokenandof visual/writtenlanguage,visuospatialneglect,prosopagnosia,coloragnosia,disordersofshort-termandlong-term memory,anddisordersofemotionandsocialcognition).Sincethetemporallobeprovidestheneuralunderpinnings ofauditoryandvisualpathwaysandiscriticalformultisensoryintegration,studiesofindividualswithcongenitalor earlysensorydeprivationarealsoreviewed,astheyinvestigatetheneuroplasticitymechanismsinvolvedintheremediation/compensationofinbornorearly-acquireddisordersofmodality-specificperception/recognition.Chaptersalso provideanoverviewofthecurrentneurofunctionalandneurophysiologicevidencefromneurotypicalparticipantsand brain-damagedindividualstopinpointconvergingevidence,divergingevidence,andgapsbetweenthetwodata sources.Eventhoughcontrastingdatacontinuetoexist,functionalneuroimagingstudiesincontrolpopulations and(mostlystructural)investigationsinbrain-damagedpersonswillhavetoconvergeultimately.Pointingoutthe outstandingdiscrepanciesinsomekeyareaswillhopefullystimulatefurtherresearchaimedatovercomingthem.

SectionIII(Chapters23–29)providesanupdateonconditionsthataffectspecificallyorpredominantlythetemporal lobe, with specialemphasisontemporallobeepilepsy,limbicencephalitis,andneurodegenerativediseases(frontotemporaldementiaandAlzheimerdisease).Thesechapterspointouthowspecificgeneticdefectsorauto-antibodies directedagainstaneuronalproteinmayprogressivelydisturbthetemporalnetworksandresultinspecificpathologic behaviors.Thechaptersalsoreviewthecurrentdiagnosticandtherapeuticapproachesandpointoutfuturedirections forclinicalandbasicresearch.

Seenasawhole,chapterscontributetothesamegoal areviewoftheevidenceonthefunctionsofthetemporallobe andonthedysfunctionsensuingfromdamage.However,theydifferwidelyintermsofthefocusoftheirnarrative,thus showcasingtheheterogeneityoftheexperimentalapproaches.Whilesomechaptersprovideclinicalupdateson specificsigns,symptoms,orclinicalconditions,othersconcentrateonbasicresearchanditsimplicationsfortheinterpretationofclinicalpictures.Yetothersfocusonneuroplasticity,biomarkers,intracerebralrecordings,andsoon. However,andregardlessofthespecificapproachtakenbyeachcontributor,consideringthevolumeinitsentirety allowsonetopinpointsomeoverarchingissuesthatreflectthestateoftheartandcouldstimulatefutureresearch. Themostobviousissueisthattherole(s)ofthetemporallobecanonlybeunderstoodif(eachportionof)thisregion isconsiderednotinisolationbutasacomponentofanumberoflarge-scalenetworkstowhichitcontributestoa differentextentandwithdifferentroles.Thisappliesnotonlytotheso-calledhigh-levelfunctionsbutalsotobasic sensoryandperceptualskillsandtotheemotionaldomain.Luckily,currentneuropsychologic,neurophysiologic, andneuroimagingmethodsallowaddressingtheoreticalandclinicalissuesatalevelofcomplexitythat,albeitstill

less-than-ideal,wouldhavebeenunimaginable20orsoyearsago.Technicaladvancespermitinvivoinvestigationsto focussimultaneouslyonmultiplecorticalareasaswellasontheirwhitematterconnections.Hence,itispossibleto investigateinthesameexperimentalsettingnotjustonefacetofaspecificcognitiveskillbutalsoitsintegrationwith othercognitiveabilitiesandtheunderlyingneurofunctionalinteractionsthatmakeitpossible.Asaconsequence, researchquestionsarenolongerrestrictedtoestablishingwhetherthetemporallobe(oraspecificportionthereof) ispartoftheneuralnetworkinvolvedinacognitivefunctionbutcanbebroadenedtoaddressthequalitativeand quantitativeinteractionsbetweenthetemporallobeandotherregionsinthatfunction.

Afurtherissueistightlyinterwovenwiththatdiscussedinthepreviousparagraph.Sincethe1970s,studiesonthe neuralrepresentationofcognitive/linguisticfunctionshavetypicallystartedfromtheselectionofaspecificcategoryor behavioralpartitionidentifiedbyinvestigationsinrelatedfields(psychology,psycholinguistics,linguistics,etc.),such asphoneme,noun,verb,semanticcategory,extrapersonalspace,andworkingmemory.Studieshavethencollected evidenceofdeviantbehaviorinbrain-damagedindividuals,inordertocorrelatethesecategoriesandpartitionswith specificneuralsubstrates.Thisapproach,heraldedbycognitiveneuropsychology,hasyieldedverysignificantresults inpromptingincreasinglydetailedfunctionalmodelsofcognitiveabilitiesandhasbeenmoderatelysuccessfulin clarifyingbasicanatomoclinicalcorrelations,largelybasedonstructuralMRIdata.Resultsofcurrentstudiesthatadopt increasinglysophisticatedtechniques(e.g.,electrocorticalrecordingsfrommultielectrodegrids,andhigh-fieldfMRI) suggestthatthisapproachshouldnotbetakenforgranted.Theissueinthiscaseconcernstheextenttowhichresearch questionsshouldstillfocusexclusivelyonpsychologically/linguisticallyderivednotionssuchasthosementioned earlier,asopposedtousingunitsofanalysisdrivenbymoreneurallybasedevidence.Thisquestionisraisedbyrecent observations.Forexample,alinguistic “category” mightbebestcharacterizednotbythefactthatitsmemberssharea setofabstractfeaturesbutbythefactthattheyelicitthesameorverysimilarpatternsofactivityinspecific(shared?) neuralnetworks.Adoptingthislatteroptionwouldnotonlyshifttheemphasisofneurofunctionalstudiesfurthertoward theneuralsidebutalsochallengelong-lastingtheoreticalconstraintsonthetypesofissuesthatdeservetobesystematicallyinvestigatedinstudiesontheneuralcorrelatesofcognition,language,andbehavior.

Asafinalnote,wewouldliketoemphasizethatcollatingthechaptersforthisvolumehastakenlongerthan expected,duetolimitationsanddelaysimposedbytheCOVID-19pandemic.Forthisreason,weareparticularly gratefultoallthecontributorswhoacceptedtosharethiscomplicatedadventurewithus.WearealsogratefultoMike Parkinsonforhispatience,availability,andprofessionalism,andtotheserieseditorsfortheirsupport.Wehopethatthe volumewillbeusefultoprofessionalswhooperateindifferentareasoftheneurologicandpsychologicsciencesand thatitwillprovidefoodforthoughtandstimulationforfurtherclinicalandbasicresearch.

GabrieleMiceli PaoloBartolomeo VincentNavarro

Foreword Thefirmbeliefthatsomepartsofthebrainareassociatedwithspecificbehaviorsismorerecentthanonemightthink. Ofcourse,therewasthepioneeringworkofGallandBroca,butmanypeopleresistedtheidea.LouisGratiolet (1815–1865)iscreditedwithattributingtheircurrentnamestothecerebrallobes,buthestronglydisagreedwithBroca onthesubjectofcerebrallocalizationalthoughtheybothcamefromthesamesmalltowninSouthwesternFrance (SteFoylaGrande).KarlLashley(1890–1958),oneofthemostcitedfiguresinthefieldofpsychology,introduced, aslateasthe1950s,theprinciplesof massaction and equipotentiality,implyingthatlossoffunctionafterbraininjury depends on theamountoftissuedestroyed,notonitslocation,andthatonepartofthecortexcantakeoverthefunction ofotherdamagedparts.Interestinwhatisnowknownasneuropsychologydeclinedalsobecausetheanatomo-clinical methodhadreacheditslimits.Renewedattentionwasduetotheentryintothefieldofallieddisciplinessuchas cognitivepsychology,neurolinguistics,and,aboveall,neuroimaging.

Therefore,someyearsago,the HandbookofClinicalNeurology undertookthetaskofpresentingbrain–behavior correlationsofspecificpartsofthecentralnervoussystem.Thefirstvolumeofthekindwastheonededicatedtothe parietallobe,thencamethecerebellum,thefrontallobe,andthecingulatecortex.Thehypothalamusholdsaspecial placeinthatrespectbecauseitwascoveredinthefirsttwovolumesofthecurrentseriesofthe Handbook andhasvery recentlybeenthesubjectoffourvolumes,allofthemeditedbyDickSwaab,coeditorofthecurrentseries.Wenow proudlypresentthisvolumeofthe Handbook devotedinitsentiretyandforthefirsttimetothetemporallobe.

Thevolumeincludesthreesections.Followingchaptersonthehistory,cytoarchitecture,andmainconnectionsof thetemporallobe,thesecondsectionpresentsvariousaspectsoftheirfunctionswithemphasisonlanguage,emotions, andmemory.Ineachcase,theevidenceisbasedonobservationsofsubjectswithacquireddeficitsaswellasstudiesof individualswithcongenitallesionsincludingearlysensorydeprivation.Muchemphasisisgiventomodernexploratory techniques,particularlyimagingandneurophysiologicstudiesthatinvolvenormalsubjects.Thefinalsectiondeals withsomeofthemainconditionsthataffectthetemporallobesincludingAlzheimerdiseaseandrelateddisorders. Threeofthechaptersinthissectiondealwithtemporallobeepilepsy(TLE)andincludediscussionsofspecialproblems,includingdiagnosis,clinicalfeatures,andneuropsychologicstudiesofpatientswiththisdiagnosis.TheconcludingchapterevaluatescriticallytheopportunitiesforsurgicalinterventioninTLE.

Wecongratulateandaremostgratefultothethreeeditorsofthepresentvolume:GabrieleMiceli,CenterforMind/ BrainSciences,UniversityofTrento,Rovereto,Italy;PaoloBartolomeo,ParisBrainInstitute,SorbonneUniversite, Pitie-Salp^ etrièreUniversityHospital,Paris;andVincentNavarro,EpilepsyandEEGUnit,ReferenceCenterforRare Epilepsies,DepartmentofNeurologyandDepartmentofClinicalNeurophysiology,Pitie-Salp^ etrièreUniversity HospitalParis,France.Togethertheyhavebroughtaremarkablesetofauthors,thusassuringtherightmixofcontinuity andhighlyupdatedinformationconcerningdisordersofthetemporallobes.

Asserieseditors,wereviewedallthechaptersinthevolumeandmadesuggestionsforimprovement,butweare delightedthatthevolumeeditorsandchapterauthorsproducedsuchscholarlyandcomprehensiveaccountsofdifferent aspectsofthetopic.Wehopethatthevolumewillappealtocliniciansasastate-of-the-artreferencethatsummarizesthe clinicalfeaturesandmanagementofpatientswithtemporallobedisorders.Wealsohopethatjuniorresearcherswill findwithinitthefoundationsfornewapproachestothestudyofthecomplexissuesinvolved.

Inadditiontotheprintversion,thevolumesareavailableelectronicallyonElsevier ’sScienceDirectwebsite: https:// www.sciencedir ect.com/.ScienceDirectispopularamongreadersandwillimprovethebooks’ accessibility.Indeed,all thevolumesinthepresentHCNseriesareavailableelectronicallyonthiswebsite.Thisshouldmakethemevenmore accessibletoreadersandalsofacilitatesearchesforspecificinformation.

Asalways,itisapleasuretothankElsevier(ourpublisher)andinparticularMichaelParkinsoninScotland,Nikki LevyandKristiAndersoninSanDiego,andPunithavathyGovindaradjaneatElsevierGlobalBookProductionin Chennai,fortheirassistanceinthedevelopmentandproductionofthe HandbookofClinicalNeurology.

MichaelJ.Aminoff Franc ¸ oisBoller DickSwaab

HandbookofClinicalNeurology, Vol.187(3rdseries)

TheTemporalLobe

G.Miceli,P.Bartolomeo,andV.Navarro,Editors https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823493-8.00001-8 Copyright©2022ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved

Theconnectionalanatomyofthetemporallobe MARCOCATANI1,2*

1Natbrainlab,DepartmentofForensicandNeurodevelopmentalSciences,InstituteofPsychiatry, PsychologyandNeuroscience,London,UnitedKingdom

2DepartmentofNeuroimagingSciences,InstituteofPsychiatry,PsychologyandNeuroscience,London,UnitedKingdom

Abstract

Theideaofatemporallobeseparatedfromtherestofthehemispherebyreasonofitsuniquestructuraland functionalpropertiesisaclinicallyusefulartifact.Whilethetemporallobecanbesafelydefinedasthe portionofthecerebrumlodgedinthemiddlecranialfossa,thepatternofitsconnectionsisamorerevealing descriptionofitsfunctionalsubdivisionsandspecificcontributiontohighercognitivefunctions.This chapterprovidesanhistoricaloverviewoftheanatomyofthetemporallobeandanupdatedframework oftemporallobeconnectionsbasedontractographystudiesofhumanandnonhumanprimatesandpatients withbraindisorders.Comparedtomonkeys,thehumantemporallobeshowsarelativelyincreasedconnectivitywithperisylvianfrontalandparietalregionsandasetofuniqueintrinsicconnections,whichmay havesupportedtheevolutionofworkingmemory,semanticrepresentation,andlanguageinourspecies. Conversely,thedecreasedvolumeoftheanterior(limbic)interhemispherictemporalconnectionsin humansisrelatedtoareducedrelianceonolfactionandapartialtransferenceoffunctionsfromtheanterior commissuretotheposteriorcorpuscallosum.Overallthenoveldatafromtractographysuggestarevision ofcurrentdualstreammodelsforvisualandauditoryprocessing.

NOTESONHISTORY1 Thestoryofthetemporallobeisreallytwostories,that ofthelimbicsystemthatcontributestoitsanteromedial subdivisionandthatoftheisocortexthatliesbelowthe lateralfissure.Thelimbicsystemstorybeginsin1587 whenGiulioCesareAranzidescribedthehippocampus anditsanatomicalproximitytotheneighboringsectors ofthelateralventriclesandthewhitematterofthefornix (Aranzi,1587).In1664ThomasWillisusedforthe first timetheterm “limbus” toindicateasemicircular convolutionborderingthediencephalon;hislimbicconvolutionincludedthecingulategyruscirclingaround thecorpuscallosumandtheparahippocampalgyrus

(PHG)locatedinthemedialaspectofthetemporallobe (Willis,1664).Alongthemedialsurfaceofthetemporal lobe,justanteriortotheheadofthehippocampus,aprotrudingconvolutioncaughttheeyeofVicqd’Azyrwho referredtoitas uncus inhis1786atlas(Vicqd’Azyr, 1786).CarlBurdachnamed amygdala the subcortical graymatterovoidresponsibleforthepeculiarbulging shapeoftheuncus(Burdach,1819–26).Theanatomical proximityandconnectivitypatternbetweenthemedial temporalstructuresandtheolfactoryregionsledthe GermanbrothersGottfriedandLudolphTreviranus (TreviranusandTreviranus,1816)toconsiderapossible roleofthehippocampusinmemoryfunctions.Bythe endofthe19thcentury,aseriesofcomparativeand

1AbbreviationsusedinthechapterarelistedattheendofthechapterbeforeReferencessection.

*Correspondenceto:MarcoCatani,Natbrainlab,DepartmentofForensicandNeurodevelopmentalSciences,Instituteof Psychiatry,PsychologyandNeuroscience,16DeCrespignyPark,LondonSE58AF,UnitedKingdom.Tel:+44-207-848-0984, Fax:+44-207-848-0650,E-mail:marco.1.catani@iop.kcl.ac.uk

experimentalstudiesinanimalsandclinical –anatomical observationsinpatientswithbrainlesionsconsolidated theconceptofalimbicsystemcomposedofcorticalareas andsubcorticalnucleiconnectedbywhitematterfibersof thefornix,mammillothalamictract,thalamicprojections, uncinatefasciculus,andcingulum.Thismodelbecame knowninEuropeasthe grandlobelimbique (Broca, 1878)orthe limbicsystem (Bechterew,1900; Jakob, 1906),andmuchlaterasthe Papezcircuit intheUnited States(Papez,1937).Ofnote,alllimbicconnections, exceptforthemammillothalamictract,originateorterminateinthetemporallobe(foranextendedreviewofthe historyofthelimbicsystem,see Catanietal.,2013).

Whilethetemporallimbiccomponentsarerelatively preservedamongvertebrates,itisonlyinprimatesthat thetemporallobeemergesasaclearlyidentifiablesubdivisionofthecerebralhemisphereduetotheremarkable expansionoftheisocortexthatoccursinmammalian evolution(Gloor,1997).Thefirsttorealizesuchadistinctiveanatomicalfeatureofthehumanbrainwas FranciscusSylvius,whodescribedadeepfissureseparatingasmallerventralpartofthecerebrum thetemporallobe fromtherestofthecerebralhemisphere (Bartholin,1641).Inthe18thcentury,someanatomists proposed athreepartitionofthecerebralhemispheresin whichthetemporalandparietallobeswerelumped togetherintothe “middlelobe,” flankedbyananterior andaposteriorlobe.Whiletheborderbetweentheanteriorandthemiddlelobehadsomeanatomicalgrounds theanteriorlobeoccupiestheanteriorfossaandthecentralsulcusisaclearlandmarkinallbrains theborder betweenthemiddleandtheposteriorlobewasparticularlydifficulttodefine.In1786,Vicqd’Azyrsuggested thepreoccipitalnotch,whichheadmittedlyrecognized asafaintanatomicalfeatureinmostofthebrainshe examined,asapossiblelandmarkfortheseparation betweenthemiddleandtheposteriorlobe,acriterion thatsurprisinglyisstillinuse.Hewasalsoresponsible forreplacingthetermsanterior,middle,andposterior lobeswiththenamesfrontal,parietal,andoccipital borrowedfromtheoverlyingbonesoftheskull.

Asprogressiveclinicalevidenceforaprominentrole inlanguagecomprehension(Wernicke,1874),behavior (BrownandSchafer,1888),andmemoryfunctions (Bechterew,1900)accumulatedinthesecondhalfof the 19thcentury,theconceptofatemporallobedistinguishedfromaposterioroccipitallobecompletelydedicatedtovisualfunctionsandaparietallobededicatedto sensorimotorandvisuospatialfunctionsbecamewidely accepted.But,experimentalsupportfortheauditory functionofthetemporallobewassurprisinglyslower inemerging(Finger,1994)comparedtothatofother senses,perhapsbecauseofthedifficultyofexamining hearinginanimals(ClarkeandO’Malley,1996).Ittook David Ferrieralmost10yearsofelectricalstimulation

andcorticalablationinmonkeystoconvincehiscolleaguesofthelocalizationofauditoryfunctionsinthe superiorregionofthetemporallobe.Thefinalproof wasdeliveredbyFerrierin1881attheInternational MedicalCongressheldinLondonwherehepublicly demonstratedthatoneofhismonkeyswithbilateralablationofthesuperiortemporalgyruswassodeafthatit didnotevenshowastartleresponsetothesoundofa gunfiredclosedtoitsear(FerrierandYeo,1884 ).In 1895, vonMonakowreportedthataftercorticalablationofthetemporalauditoryareainacat,retrograde degenerationwasevidentinthepartofthethalamus thatBurdachdescribedin1822asthe corpusgeniculatuminternum laterrenamedthemedialgeniculate nucleus(MGN)( vonMonakow,1895 ).In1896, Flechsig discoveredthattheareasofthetemporal auditorycortexwheremostoftheMGNfibersproject toarealreadymyelinatedina2-month-oldnewborn brain(Flechsig,1896).Hence,justlikehedidfortheother lobes,Flechsigseparatedtheearlymyelinatedareasofthe temporallobelocatedinthetransversegyrusdescribed byHeschl whichhetermedthe “primordial” fieldsor accordingtocontemporarynomenclatureprimaryauditoryareas fromthelatemyelinatedassociativetemporalareas.Thetemporalareashavebeensubsequently mappedintoamultitudeofsmallerareaswhosenumber variesaccordingtotheanimalmodelandthemethod adoptedtoidentifythebordersbetweencorticalfields (see Chapter2)(foranextendedreviewofthehistory of theauditorycortexanditsconnections,see Finger, 1994; Jones,2011).

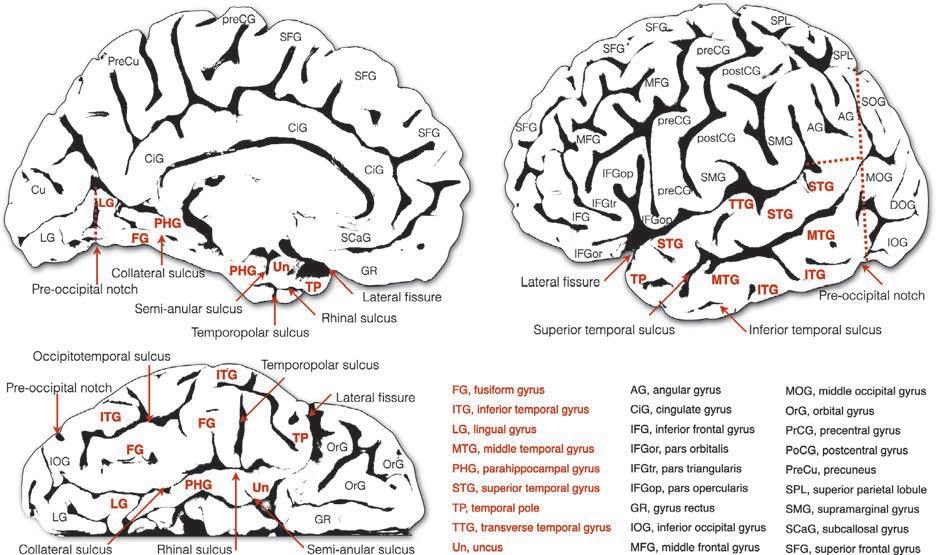

SURFACEANATOMY Externally,thetemporallobehasasuperior,lateral,and inferior(ventral)surface(Fig.1.1).Thesuperiortemporal surfaceisburiedwithinthesylvanfissureandforms thetemporaloperculumthatcoverstheinsula.Thissurfaceisflatexceptforitscentralportionthatisoccupied bythebulgingtransversegyrusofHeschl.Thisgyrus, whichisoftenduplicated,isseparatedfromtherestof thesuperiortemporalsurfacebytheanteriorandposteriortransversetemporalsulci.Thesurfaceofthesuperior temporalgyrusthatliesanteriorandposteriortothe transversetemporalgyrusofHeschlformstheplanum polareandplanumtemporale,respectively.

Onthelateralsurface,thesuperior,middle,andinferiortemporalgyricourselongitudinallyandconverge anteriorlytoformthetemporalpole.Thesuperiorand middletemporalgyriareoftenwellseparatedbyacontinuoussuperiortemporalsulcus.Inhumansthemiddle andinferiortemporalgyriareseparatedbytheinferior temporalsulcus,whichisoftendifficulttorecognize asasinglelineargroove.

Fig.1.1. Surfaceanatomyofthetemporallobe.Medial(upperleft),lateral(upperright),andventral(lowerleft)surfacesofthe temporallobe.Temporalgyriarelabeledinred.ModifiedfromCataniM,Dell’AcquaF(inpress).Atlasofhumanbrainpathways, Elsevier.

TEMPORALLOBETRACTS Mostoftheinferiorsurfaceofthetemporallobeiscoveredbytheventralportionoftheinferiortemporalgyrus, thefusiformgyrus,andthePHG.Allthecortexofthefusiformgyrusbelongstothetemporallobeexceptforitsmost posteriortip,whichispartoftheoccipitallobe.Theprincipalsulcioftheinferiorsurfacearethelateraloccipitotemporalsulcusandthecollateralsulcus,whichseparate thefusiformgyrusfromtheinferiortemporalgyrusand thePHG,respectively.Theanteriorpartofthecollateral sulcusisalsotermedrhinalsulcus.Smallersulcicanoften berecognizedontheinferiorandmedialsurface,suchas thetemporopolarsulcusthatdefinestheposteriorborder ofthetemporalpoleandthesemianularsulcus.Thelatter sulcusisoftenusedasanexternalanatomicallandmarkto separatethePHGcoveringtheheadofthehippocampus fromtheuncus.

WhiletheSylvianfissurerepresentsanaturalanatomicallandmarkbetweenthetemporallobeandboththe frontalandanteriorparietallobes,theposteriorborders betweenthetemporal,occipital,andparietallobesare arbitraryasoftenthesuperior,middle,andinferiortemporalgyricontinueintotheangulargyrusoftheparietallobe andthemiddleandinferioroccipitalgyri.Thisanatomical continuityishighlightedbythefrequentuseoftheterm “temporo-occipital-parietaljunction” intheneuroimagingliterature.

Oncoronalsections,thetemporallobeappearslikea smallcauliflowercomposedofasingleshortstemand smallfloretsthatcorrespondtothefivelongitudinaltemporalgyri(Fig.1.2A–C).Itstemporalstemoriginates fromtheflooroftheexternal-extremecapsuleandin itsnarrowestportioniscontainedwithinaspacedelimitedmediallybythelateralventricleandlaterallybythe inferiorbranchoftheperi-insularsulcus.Exceptfor thecingulum,thefornix,andthestriaterminalis,thetemporalstemcontainsmostoftheprojectiontractsfrom thethalamus(temporothalamic),MGN(auditoryradiations),andbasalganglia,thecommissuralfibersofthe corpuscallosum(tapetum)andanteriorcommissure, andthelargeassociationfibersofthelongandposterior segmentsofthearcuatefasciculus,uncinatefasciculus, andinferiorfronto-occipitalfasciculus(IFOF).Short associationtractsconnectingthetemporalcortextothe insulaarealsoenclosedintheposteriorandtheanterior portionsofthetemporalstem.Withinthetemporalstem mostofthesefibersrunparalleltothelateralventricle beforetakingamoreradialcourseoutwardlytoward thecortexofeachtemporalgyrus.Therestofthewhite matterbetweenthetemporalstemandthetemporalcortexisoccupiedbytheinferiorlongitudinalfasciculus (ILF)andtheshort-associationtemporaltracts.

Fig.1.2. Coronalslicescuttingthroughtheposterior(A),middle(B),andanterior(C)temporallobe.Thetemporalstemisindicatedwitha whitestar.Theshortassociativeandcommissuraltractsaredisplayedinthe leftimages whilethemajorprojectionand longassociationtractsareonthe right.Alltemporalconnectionsareindicatedwithan asterisk.ModifiedfromCataniM,Dell’AcquaF(inpress).Atlasofhumanbrainpathways,Elsevier.

Projectionpathways Thetemporallobehasextensiveconnectionswiththe inferiorcolliculus,theMGN,thepulvinarandthedorsomedialnucleusofthethalamus,thestriatumandclaustrum,thehypothalamicnuclei,andthemammillary bodies.Thetemporalprojectionscanbeseparatedinto anonlimbicgroupencompassingtheauditoryandtemporothalamicradiations,andthepathwaysofthelimbic system.

The auditoryradiations arethemainafferentsensory pathwaytothetemporallobe.Theyareresponsiblefor

relayingauditoryinformationfromtheMGNandinferiorcolliculustothetemporalcortex.Inthebrainstem, thelaterallemniscusconveysauditoryinputsfromthe cochlearnucleiandtheolivarycomplextotheinferior colliculus,whichinturnprojectstotheMGN.Thecolliculogeniculatefibersarevisibleontheposterioraspect ofthemesencephalonasanobliqueprotrusioncalledthe inferiorbrachium(Naidich,2020).Somefibersfrom theinferiorcolliculuscontinuedirectlywithoutstopping andmergewiththosefromthemedialgeniculatetoform theauditoryradiations.Afterashorthorizontalcourse

withinthemostposteriorregionoftheinternalcapsule, theauditoryradiationspassinferiortotheputamenand enterintothetemporalstem.Here,mostoftheauditory radiationscontinuelaterallyandanteriorlywithin Heschl’sgyrusandterminateinthecortexoftheearly auditoryareas.Theinformationcarriedbytheacoustic radiationstotheprimaryauditorycortexispartially segregatedaccordingtothespatialorganizationofthe corticalneuronsdecodingsoundsofdifferentfrequency (tonotopy)orintensity(ampliotopy).Inthesuperiortemporalcortex,severaltonotopicareashavebeendescribed inthecortexofHeschl’sgyrusandsurroundingcortexof thesuperiortemporalgyrus(Talavageetal.,2004).The acousticradiationsalsocontainfibersthatruninthe reversedirectionfromthetemporalcortextotheMGN andinferiorcolliculus(Pickles,2015).Thiscentrifugal systemmediatesatop-downmodulatorycontrolused bythetemporalcortextoenhancetheresponseof subcorticalnucleitosalientstimuli.

Theprimaryauditorycortexreceivesthemajorityof theauditoryinputsfromtheMGNandinferiorcolliculus, whoseprojectionsbecomeprogressivelyweakerinmore anteriorandlateraltemporalregions.Thisreductionis offsetbyarelativeincreaseinfiberdensityfromthemultisensorythalamicnucleithatconveybothauditoryand visualinformation(Hackett,2015).Theseconnections are collectivelytermed temporothalamicfibers andtheir initialcourseisdifferentaccordingtotheirlateralor medialorigininthethalamus.Thethalamicfibersthat originatefromthelateralpulvinarnucleirunparallelto theauditoryradiationsandhaveasublenticularcourse. Theseconnectionsareindicatedbysomeauthorsas thetemporopulvinarbundleofArnold(Gloor,1997). The connectionsfromthemedialnucleiofthepulvinar andmidlinethalamicnucleirunthroughthestratum zonale,athinlayerofwhitematterthatcoverstheventricularsurfaceofthethalamus(Fig.1.2Bright).These fiberscurvearoundtheposteriorandinferiorsurfaces ofthethalamusandmergewiththeinferiorfibersof theauditoryradiationsbeforeenteringthetemporallobe. Bothmedialandlateraldivisionsofthetemporothalamic projectionsarereciprocalandruntogetherwiththefibers ofthestriaterminaliswithinthewhitematterthatform thelateralwallandroofofthelateralventricle.

Tractographyandpostmortemstudiesusinghistology andbluntdissectionhavebeenusedtovisualizethe acousticradiations,althoughitisoftendifficultto obtaintheirentirereconstructionduetothelimitations ofthesetechniques(Burgeletal.,2006; Behrensetal., 2007; Maffeietal.,2015,2017).Tractographyreconstructionsofthemostdorsalandlateralacousticprojectionsarepossibleonlywithadvanceddiffusionmethods duetothecomplexityofthewhitematterregionlateral tothethalamusandposteriortothelenticularnucleus

(Behrensetal.,2007; Maffeietal.,2015, Maffeietal., 2019).Here,theacousticradiationsdirectinglaterally towardHeschl’sgyruscrosswithalargegroupofassociationandprojectionfiberscoursingaroundtheposterior insulainaperpendiculardirection(e.g.,arcuatefiber, middlelongitudinalfasciculus(MLF),IFOF).Other acousticradiationsdirectedtowardmoreanteriortemporal regionscanbeeasilyvisualizedalsowithtractography algorithmsbasedonthetensormodel.

Theorganizationoftheacousticandtemporothalamic projectionsisbothserialandparallelasmanyfibersproject directlytodownstreamtemporalregions(Pickles,2015). ThedirectacousticprojectionsfromtheMGNtotheamygdala,forexample,undergochangesinresponsetofear conditioningandthesechangesareresponsiblefortheformationofmemoriesrelatedtobothsafeandthreatening auditorycues(Ferraraetal.,2017).Inhumans,arelative temporalcortexamygdalahyperactivationtosadand hypoactivationtohappysoundshavebeenreportedin infantsborntodepressedmothers.Thismaysuggestaneuralbiastowardemotionallynegativestimuli,mediatedby theeffectofperinatalexposuretomaternaldepressionon theearlydevelopmentoftheauditoryandtemporothalamic radiations(Craigetal.,2022).

The crossedbilateraldistributionoftheauditorypathwaysandtheirparallelorganizationwithinthetemporal lobecouldalsoexplainthedifferentmanifestationsassociatedwithdamagetoauditorypathways.Hearingdisorderscommonlyassociatedwithdamagetotheacoustic radiationsandtheirsubcortical/corticalterminations includereduced(corticaldeafness)orincreased(hyperacusis)perceptualawarenesstosound.Otherauditory phenomenaassociatedwithacousticradiationdamageincludetinnitus,auditoryhallucinations,andpalinacousis(perseverationofthehearingsensationafter cessationoftheexternalstimulus).Theunderlying mechanismsresponsiblefortheseclinicalmanifestationsmayvaryandincludesubcorticalorcortical damagedisconnectionresultinginthehypoactivityor hyperactivityofcentripetaland/orcentrifugalnetworks. Aselectivedamageofthenucleiand/orfibersinvolved inprocessingwordsoundsmanifestswithpureword deafness(Maffeietal.,2017).

The twomajorsubcorticallimbicgreystructuresof thetemporallobehavetheirownsystemofafferent andefferentconnectionsthattheyusetoreceivesensory stimulidirectlyfromearlysensoryareasorindirectly fromassociationareasortheinsula.Theinformation thatreachesthehippocampusandamygdalaisthen furtherelaboratedandconsolidatedintomemorytraces thatcaninfluenceourcognitivefunctionsandvisceral bodyresponses(Catanietal.,2013).

The fibersofthefornixarisefromthehippocampusof eachside,runthroughthefimbria(i.e.,thetwolegsofthe

fornix),andjoinbeneaththespleniumofthecorpus callosumtoformthebodyofthefornix.Otherfimbrial fiberscontinuemedially,crossthemidlinethroughthe hippocampalcommissure,andprojecttothecontralateralhippocampus.Mostofthefiberswithinthebody ofthefornixrunanteriorlybeneaththebodyofthecorpuscallosumtowardtheanteriorcommissurewithout crossingthemidline.Astheyapproachtheanteriorcommissure,theydivideintoleftandrightanteriorcolumns andleftandrightposteriorcolumns.Theanteriorcolumnsenterthehypothalamusandprojecttotheseptal andhypothalamicnucleiandthenucleusaccumbens. Theposteriorcolumnsofthefornixcurveventrallyin frontoftheinterventricularforamenofMonroeand posteriortotheanteriorcommissurebeforeterminating intothemammillarybody(postcommissuralfornix), adjacentareasofthehypothalamus,andanteriorthalamicnucleus.Allthecomponentsofthefornixcanbe dissectedwithdiffusiontractography(Catanietal., 2002, 2013).

The threemainfibersystemsoftheamygdalaarethe lateralolfactorystria,the striaterminalis (ordorsal amygdalofugalpathway),andthe amygdaloidpeduncle (orventralamygdalofugalpathway).Theamygdaloid peduncleistheprimaryoutputoftheamygdalatoother structuresofthelimbicsystemlocatedoutsidethetemporallobe,suchastheanteriorhypothalamicnuclei, thestriatum particularlydensearetheterminationsto thenucleusaccumbens,thesubgenualanteriorcingulate cortexandseptalnuclei,themedialdorsalnucleusof thethalamus,andthebasalforebrain(Canterasetal., 1995; Kamalietal.,2016).Theamygdalaconnections are ofparticularinterestwithregardtounderstanding humanstress-relatedpsychiatricdisease(Lebowand Chen,2016).

Commissuralpathways Thehumantemporallobehasauniquelyrichpattern ofcommissuralconnections,beingtheonlyregionconnectedbyallthreecommissuresofthecerebralhemispheres,namely,theposteriorcorpuscallosum,the anteriorcommissure,andthehippocampalcommissure.

Thecallosalfibersfromtheposterioristhmusandthe spleniumrunwithinthewhitematterthatformsthedorsolateralwallofthelateralventricles.Fortheirlaminar arrangementalongthetemporalstem,thetemporalcallosalfibersaregenerallyindicatedwiththeterm tapetum (fromLatin,meaningcarpet)(CataniandThiebautde Schotten,2012).Thecallosalfibersreachthebeltand parabeltassociativeauditorycortex,thepolymodal temporalcortex,andpartofthetemporalvisualcortex.

Theremainingpartofthetemporalcortex,theamygdala,andthehippocampusareconnectedbytheanterior

commissureandthesmallerhippocampalcommissure. Onthemidlinesagittalsection,thefibersoftheanterior commissureoccupyacircularregionofdiameterless than2Sq.mmdelimitedbytheanteriorandposteriorcolumnsofthefornix,theseptumpellucidum,andthethird ventricle.Fromhereitsfibersdirectlaterallyanddownwardlypassingthroughtheventralportionoftheglobus pallidus.Astheanteriorcommissureleavestheregion betweentheamygdalaandtheputamenandentersthe anteriorpartofthetemporalstem,itsplitsintotwo branches.Theanteriorbranch,whichmergeswiththe fibersoftheamygdaloidpeduncle,projectstotheamygdalaandthecortexofthetemporalpole.Theposterior branchcourseswithinthetemporalstemandprojects totheventraltemporalcortexandtheanteriortwo-thirds oftheinferior,middle,andsuperiortemporalgyri (Catanietal.,2002).Axonaltracinginmonkeysandtractography inhumanshavebeenusedtolocatetheposition ofthetemporalfiberswithinthemidsagittalsectionof thecorpuscallosum(SchmahmannandPandya,2006; Parketal.,2008; CataniandThiebautdeSchotten, 2012).Studiesinthemonkeybrainindicateacertain degree ofoverlapbetweentheterritoriesoftheanterior commissureandthecorpuscallosum(Zeki,1973; JouandetandGazzaniga,1979).However,theprojection territories ofthetwocommissuresareprobablydifferent inhumansfortheproportionalvolumereductionofthe anteriorcommissureinhumanevolutioncomparedto OldWorldmonkeys(Barrettetal.,2020).Thesecomparative anatomydifferencesareprobablylinkedtoa reducedimportanceofolfactioninhumancognition paralleledbyanincreasedinter-hemisphericconnectivity betweenthoseposteriortemporalareasthathavesupportedtheemergenceofouruniquecognitiveabilities.

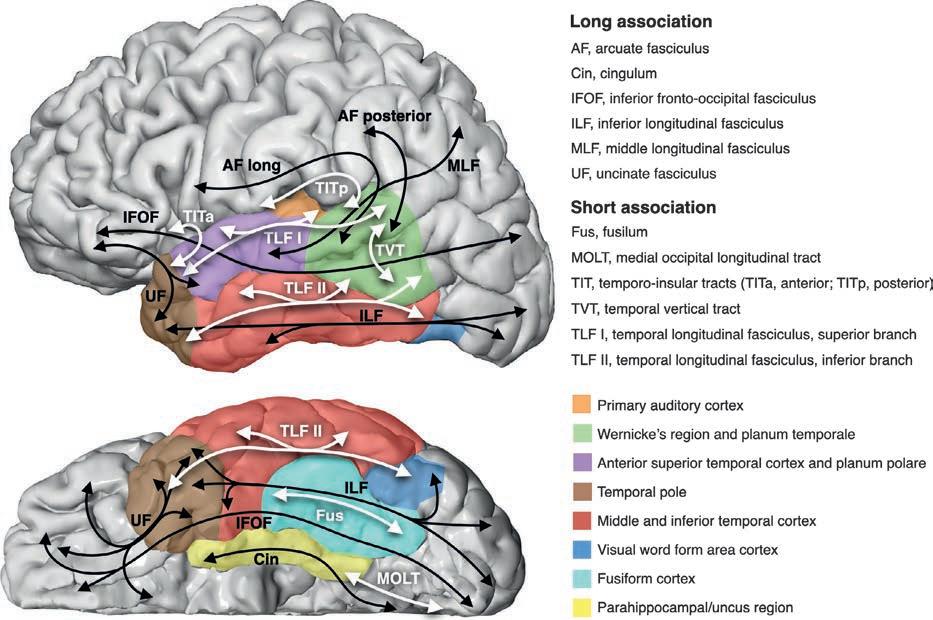

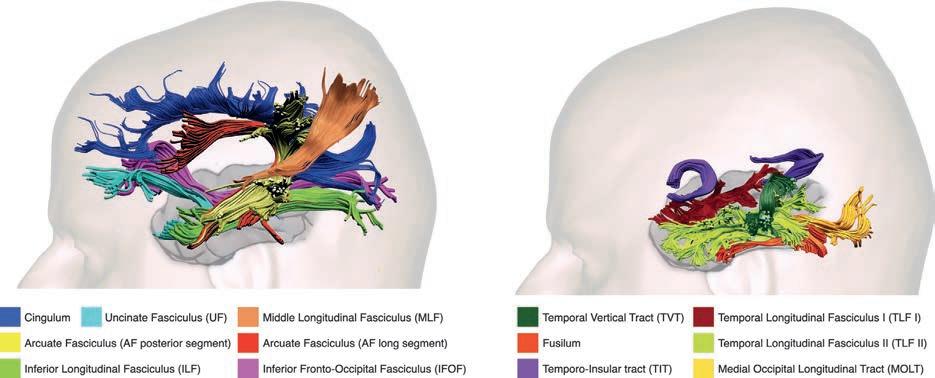

Associationpathways Theassociationpathwaysofthetemporallobecanbe dividedintotwolargegroups(Figs.1.3 and 1.4).The first groupincludesthelonginterlobarassociationpathwaysthathavebeentraditionallydescribedinhumans withpostmortemdissectiontechniquesandrecently revisitedwithtractographymethods(Fig.1.4 left).The arcuate fasciculus,theuncinatefasciculus,theILF,the IFOF,theMLF,andthecingulumarethemajorinterlobar pathwaysofthetemporallobe.Asecondgroupincludes thesmallerinterlobarfibersconnectingthetemporallobe totheneighboringcortexandtheintralobartemporal fibers(Fig.1.4 right).Amongtheshortinterlobarfibers, only theU-shapedtemporoinsulartractsandthenewly describedmedialoccipitallongitudinaltract(MOLT) (Beyhetal.,2022)willbediscussedinmoredetail.Three major systemsofintralobarfibershavebeenrecently

Fig.1.3. Diagramoftheorganizationofthemajorassociationpathwaysofthetemporallobe.Longinterlobarassociationtractsare indicatedwith blacklines,whileshortinterlobarandintralobarfibersareindicatedwith whitelines Coloredcorticalregions correspondtobroadlydefinedanatomical/functionalareasofthehumantemporallobe.

Fig.1.4. Tractographyreconstructionsofthetemporalassociationpathways. Left,majorinterlobarassociationpathways. Right, shorterinterlobarandintralobartemporaltracts.

identifiedwithtractography.Theseincludethetemporal longitudinalfasciculus(TLF)IandII,thefusilum,and thetemporalverticaltract(TVT).

ARCUATEFASCICULUS Theposteriorregionsofthesuperiorandmiddletemporalgyrusareconnectedtotheperisylvianparietaland

frontalcortexbythearcuatefasciculus.Thearcuate fasciculusiscomposedofthreesegmentslodgedinthe whitemattersurroundingthedorsalandposteriorsectionsofthecircularsulcusoftheinsula.Ofthethree segments,onlytheanteriorsegmentdoesnotoriginate orterminateinthetemporallobe(Catanietal.,2005). Tractographystudiessuggestthatboththelongand

posteriorsegmentofthearcuatefasciculushaveapartiallyoverlappingoriginorterminationintheposterior temporalregions.Afterleavingthewhitematterofthe superiorandmiddletemporalgyri,thefibersofbothlong andposteriorsegmentsgatherinthetemporalstemlaterallytothetemporothalamicprojectionsandopticradiations,beforebendingaroundtheposteriorsectionofthe circularsulcusoftheinsula(Fig.1.2AandBright).Here, the mostlateralfibersoftheposteriorsegmentcontinue dorsallyandarchlaterallytowardthecortexoftheangulargyrusandtheposteriorcortexofthesupramarginal gyrus.Thefibersofthelongsegmentcontinuetoarch aroundthecircularsulcusoftheinsulaandastheyenter theparietallobetheyfollowahorizontalcoursemedialto theanteriorsegmentofthearcuatefasciculus.Asthe longsegmentfiberspassthecentralsulcustheycurvelaterallytoreachtheinferiorcortexoftheprecentralgyrus andtheposteriorcortexoftheinferiorandmiddlefrontal gyri.ItcanbearguedthatsomeU-shapedfibersofthe posteriorsegmentofthearcuatefasciculusrepresent shortinterlobartemporoparietalfibers(Fig.1.2).

The temporalconnectionsofthearcuatefasciculus havechangedsignificantlyinprimateevolutioncompared,forexample,toothertemporalconnectionsof thelimbicsystem(e.g.,uncinatefasciculus).Nonhuman primatesshareasubcomponentofthelongsegmentof thearcuatefasciculuswithhumans(Rillingetal., 2008; Barrettetal.,2020),whichprojectstotheposterior superi ortemporalgyrusandisinvolvedinacoustic spatiotemporalprocessingandstimulusidentification (AboitizandGarcía,2009).However,inhumans,the long segmentofthearcuatefasciculusisproportionally largercomparedtothemonkeybrain(Barrettetal.,2020) and projectsmoreextensivelytothesuperiorandmiddle temporalgyri(Catanietal.,2005).Theexpandedanatomy ofthelongsegmentallowsadirectlinkbetween perisylvianregionsinvolvedwithauditorymemory (RauscheckerandScott,2009; Schulzeetal.,2012), wordlearning(López-Barrosoetal.,2013),andsyntax (Wilsonetal.,2011).Similarly,theposteriorsegment of thearcuatefasciculusconnectsareasoftheinferior parietallobuleandtheposteriortemporalgyrusthat havegreatlyexpandedinhumansfortheacquisition ofevolutionarynovelcognitiveskillssuchassentence comprehensionandrepetition(Forkeletal.,2020) and complexpragmaticcommunication(Cataniand B ambini,2014).

UNCINATEFASCICULUS Theanteriorflooroftheexternal-extremecapsuleisan obligatorypassageforallfibersconnectingtheanterior temporallobetothefrontallobe.Thesefibersarecollectivelygroupedintoasinglehook-shapedbundle,the

uncinatefasciculus.Theoriginoftheuncinatefasciculus islimitedtotheanteriorthirdoftheiso-andparalimbic temporalcortex.Astheyleavethetemporalpole,the uncinatefibersgatherintoasinglebundlethatoccupies almosttheentireanteriortemporalstem.Here,theuncinatefasciculusliesventraltotheIFOF,medialtothe smallanteriortemporoinsulartractanddorsaltotheamygdaloidpeduncleandtemporothalamicfibers(Fig.1.2C). Intheexternal-extremecapsule,theuncinatefasciculus continuestoruninparallelwiththeIFOFandasboth tractsenterthefrontallobe,theuncinatefasciculussplits intwobranches.Thelateralbrancharchesabruptly towardtheinferiorfrontalgyruswhereitsfibersterminateinthefrontalopercularandlateralcortex.The medialbranchoftheuncinatefasciculuscontinues towardthefrontalpoleandtheventromedialfrontal cortex(Catanietal.,2002).

In animalstudies,disconnectionoftheuncinate fasciculuscausesimpairmentofobject-rewardassociationlearningandreducedperformancesinmemory tasksinvolvingtemporallycomplexvisualinformation (GaffanandWilson,2008).Inanumberofneurodevelopmental andneurologicaldisorders,damagetothe uncinatefasciculushasbeenreportedtocorrelatewith severityofdeficitsinemotionalprocessing(Catani et al.,2016; D’Anna etal.,2016),behavioralinhibition (Craigetal.,2009),andimpairedobjectnaming (Catanietal.,2013).

The lackofhuman-simianspeciesdifferencesinthe relativevolumeoftheuncinatefasciculus( Barrett et al.,2020 )indicatesasharedanatomicalsubstrate for thesetemporalfibersdedicatedtoaspectsof memoryreward,andsocialbehavior( Catanietal., 2013 ; Rolls,2015 ).

INFERIORLONGITUDINALFASCICULUS TheILFisthelargestwhitematterpathwayconnecting theoccipitaltothetemporallobeanditcontainsfibersof differentlength(Catanietal.,2003).Intheoccipitallobe, the ILForiginatesfromextrastriateareasonthedorsolateraloccipitalcortex(e.g.,descendingoccipitalgyrus) andtheventralsurfaceoftheposteriorlingualandfusiformgyri(Catanietal.,2003).Thesebranchesrunanteriorly parallelandlateraltothefibersofthespleniumand opticradiationand,attheleveloftheposteriorhornof thelateralventricle,gatherintoasinglebundle.Unlike theIFOFanduncinatefasciculus,theILFneveroccupies thewhitematterofthetemporalstem.Inthetemporal lobe,theILFcontinuesanteriorlyandprojectstotheinferiortemporalgyri,thefusiformgyrus,andthetemporal pole.Itslongestfibersprojectdirectlytothehippocampusandamygdala.TheroleoftheILFistherefore centralinallactivitiesinvolvingprocessingcomplex

visualinformation,fromobjects,faces,andwordperceptiontoemotionrecognitionandsemantics(ffytcheetal., 2010).Someofthebehavioralandcognitivedeficits descri bedinpatientswithanteriortemporallobedamage areduetodisconnectionoftheILFfibersthatprevent visualinputstoreachthelimbic,paralimbic,andtemporopolarcortex.

INFERIORFRONTO-OCCIPITALFASCICULUS Ofalllongtemporalinterlobarassociationpathways,the IFOFistheonlytractcoursingthroughthetemporallobe withoutprojectingtoanyofitscorticalregions.Thistract enterstheanteriortemporallobefromthemostventral portionoftheexternal-extremecapsuleandrunslongitudinallywithinthecentralportionofthetemporalstem. Someauthorshavereportedthatasignificantnumber offibersbranchofftheIFOFandprojecttoWernicke’s region(Sauretal.,2008).Thetraditionalliteraturebased on axonaltracinginthemonkeybraindenytheexistence ofadirectconnectionbetweenoccipitalandfrontal lobes;instead,theterm “extremecapsuletract” isused toindicateconnectionsbetweenfrontalandposterolateraltemporalcortex(SchmahmannandPandya, 2006).RecentstudiessuggesttheevidenceofIFOF connectionsalsointhemonkeybrain(Marsetal.,2016).

While thefunctionsofthistractremainlargely unknown(Forkeletal.,2014)comparedtoothertracts, its greaterproportionalvolumeinhumanscomparedto monkeys(Barrettetal.,2020)mayhavefacilitateddirect frontalaccesstovisualinputsandtop-downcontrolof earlyvisualprocessingforfunctionslikefaceandobject perception(ffytcheandCatani,2005)andreading (Vanderauweraetal.,2018).Asignificantrightwardvolume hemisphericasymmetryoftheIFOF(Thiebautde Schottenetal.,2011)andtheassociationofarightIFOF disconnectioninleftspatialneglect(Urbanskietal., 2008)confirmaroleofthistractinspatialawareness.

MIDDLELONGITUDINALFASCICULUS TheMLForiginatesinthesuperiortemporalgyrusand projectstobothinferiorandsuperiorparietallobules (SchmahmannandPandya,2006).Initiallydescribed in themonkeybrainasaverticalconnectionbetween inferiorparietalandsuperiortemporallobes,theanatomicaldefinitionofthistractinhumansisstilldebated. Tractographyreconstructionsshowabundleoffibers thatoriginatewithinthesuperiortemporalgyrusand gatheratthelevelofHeschl’sgyrusbeforeentering thetemporalstem.Here,theMLFrunsparalleltothe arcuatefasciculusandlateralanddorsaltotheinferior fronto-occipitalfasciculus(Fig.1.2AandBleft).As its fibersentertheparietallobe,somebendlaterallyto

reachtheangulargyruswhileotherscontinuetoward theposteriorcortexofthesuperiorparietallobuleand precuneus.

CINGULUM ThecingulumisaC-shapedtractthatcanbedividedinto adorsal(cingulate)andaventral(parahippocampal) component.Thedorsalfibersofthecingulumformthe corewhitematterofthecingulategyrus;theyoriginate notonlyfromthecingulategyruscortexbutalsofrom theneighboringcortexofthemedialfrontalandparietal lobes.Asthefibersofthedorsalcingulumcurvebehind thespleniumofthecorpuscallosum,theyenterintothe PHGwheretheyrunparallelandventraltothefimbriae ofthefornixandthehippocampaltail.Inthetemporal lobe,thecingulumbranchesofftotheparahippocampal isocortex,themoreanteriorparalimbicandlimbiccortex,andtheamygdala.LiketheILF,thecingulumiscomposedoffibersofdifferentlengthandthedorsaland ventralcomponentscorrespondtodistinctfunctional divisionsofthelimbicsystem(Catanietal.,2013). The dorsalcingulumisthemainconnectionofthedorsomedialdefault-modenetworkconsistingofagroup ofregionswhoseactivitydecreasesduringgoal-directed tasks(RaichleandSnyder,2007).Theventralcingulum connects areasoftheprecuneus,retrosplenialcortex,and medialtemporallobeinvolvedinmemoryandspatial orientation.Theshortestfibersoftheventralcingulum carryinformationbetweentheposteriorretrosplenialcortexandtheparahippocampalareawhereasthelongest fibersreachthesubiculumofthehippocampalformation (Beyhetal.,2022).

MEDIALOCCIPITALLONGITUDINALTRACT Acoherentwhitematterbundlethatrunsbetweenthe peripheralvisualrepresentationwithinthemedialoccipitalcortexandtheposteriorPHGhasbeenrecently reportedbyourgroupusingtractography(Beyhetal., 2022).Consideringitsmediallocationandcoursealong theposterior–anterioraxis,werefertothispathwayas themedialoccipitallongitudinaltract(MOLT).The MOLThasadorsal(cuneal)andaventral(lingual)componentandbothprojectontotheposteriorparahippocampalplacearea(PPA)(Fig.1.5).FibersoftheMOLTwere identifiedinearlytractographystudiesbutwereconsideredaspartoftheventralcingulum(Catanietal.,2002) andILF(Catanietal.,2003).OurviewisthattheMOLT is anindependenttractwithauniquerolecrucialfor visuospatiallearning(Beyhetal.,2022).TheMOLT collects “raw” visualinformationfromperipheralearly visualcortex(EVC)andconveysitthePPAwhereacompletemapofthevisualsceneisgenerated.Inthiscontext, theMOLTmaycarryfeedforwardandfeedbackspatial

Fig.1.5. Tractographyreconstructionofthemedialoccipitallongitudinaltract(MOLT).TheMOLTisanoccipitotemporalwhite matterpathwaythatstemsfromtheanteriorcuneus(Cu)andlingualgyrus(LG)andterminatesintheposteriorparahippocampal gyrus(PHG).Inthemedialoccipitallobe,itprojectsontoperipheralvisualfieldrepresentationswithintheearlyvisualcortex (EVC),whileitstemporallobeterminationsoverlapwiththeposteriorparahippocampalplacearea(PPA).The dashedyellow line indicatesthecalcarinesulcus.ModifiedfromBeyhA,Dell’AcquaF,CancemiDetal.(2022).Themedialoccipitallongitudinaltractsupportsearlystageencodingofvisuospatialinformation. CommunBiol 5:318.

informationbetweentheEVCandthePPA,thereby servingasapathwayforre-entrantvisualinformation (HochsteinandAhissar,2002)thatsupportsamultistage encodingandlearningofthevisualscene.Assuch,early activationswithinthePPA(Bastinetal.,2013a)maycorrespondtoaninitialmappingofthe “gistofthescene” which,viafeedbacktotheEVC,refinesthelater,detailed mappingofobjectconfiguration.Thisrefinedinformation,stillinaretinotopicspace,couldthenbecombined withparietalandretrosplenialspatialinformationatlonger latencies(Bastinetal.,2013b),andtranslatedintoanallocentricframeofreference.Thishigherorder,viewpointinvariantspatialinformationwouldultimatelyreachmore anteriormedialtemporalregionsincludingthehippocampalformation,andmoredistantfrontalregions(Van Hoesen,1982; Kravitzetal.,2011; DaltonandMaguire, 2017).Inbothhemispheres,thelingualgyruscomponent oftheMOLThasalargervolumeanddistributestoa wideroccipitalsurfacecomparedtothecunealcomponent (Beyhetal.,2022).ThisdistinctionbecomesmoreimportantwhenweconsiderthattheMOLTmediatesastronger overallconnectivitybetweenthePPAandventralEVC (lingualgyrus,uppervisualfield)comparedwiththedorsalEVC(cuneus,lowervisualfield).Thisimbalanceisin linewithafunctionalbiaswithinthePPA,whichcontains alargerrepresentationoftheuppervisualfield.The MOLTalsoexhibitsarighthemispherelateralization, whichisanobservationthatfitsexistingliteraturereportingsuchahemisphericbiasinthespatiallearningfunctionssupportedbytheparietalandmedialtemporal

lobes.Further,thislateralizationmayexplainthehigher frequencyofvisuospatiallearningdeficitsfollowing posteriorrighthemispherelesions.

U-SHAPEDTEMPOROINSULARINTERLOBARFIBERS Shortinterlobarfibersconnectthesuperiortemporal gyrustoadjacentregionsoftheinsula(Mesulamand Mufson,1982).Inthehumanbrain,temporoinsularfibers havebeendissectedpostmortem(Nachtergaeleetal., 2019)andtwogroupscanbeidentifiedwithtractography (Fig.1.4right).Theanteriortemporoinsularfibersoriginatefromthecortexoftheplanumpolareand,through theextremecapsule,reachthelimeninsulaeandthe shortinsulargyri.Theanteriorfibersareoftendissected togetherandconfusedwiththefibersoftheuncinatefasciculus.Theposteriortemporoinsularfibersoriginate fromHeschl’sgyrusandplanumtemporaleandafter formingalooparoundthelateralfissureterminatein thelonginsulargyri.Theseconnectionsareoftendissectedtogetherwiththemostmedialfibersofthearcuate fasciculus.Theroleofthetemporoinsularconnectionsis unknowninhumansbuttheirpatternofdistributionas revealedbytractographymirrorsthefindingsfromaxonal tracingstudiesinthemonkeybrain(Mesulamand Mufson,1982).Thus,basedonthefindingsinmonkeys, theposteriorgroupmaydirectlyrelayauditoryinformationfromtheearlyauditorycortextotheposteriorinsular regionsandbymeansofreciprocalconnectionsallowthe insulatomodulateauditoryinputstotheearlyauditory

cortex.Consideringtheprominentroleofthehumananteriortemporalcortexinsemanticprocessingandsingle wordcomprehension,thefunctionoftheanteriorgroup maydivergeinhumansascomparedtomonkeys.

TEMPORALINTRALOBARTRACTS Thetemporalintralobarfiberscanbegroupedaccordingtotheirorientationintolongitudinalandvertical pathways( Fig.1.4 right).

The temporallongitudinalfasciculus(TLF)isasystemofshortandlongfibersbetweentheanteriorandposteriorregionsofthesuperior,middle,andinferior temporalgyri(CataniandDawson,2016; Maffeietal., 2017; CataniandForkel,2019).Itsmostdorsalbranch, the TLFI,runswithinthewhitematterofthesuperior temporalgyruswhereitformsachainofconnections originatinginHeschl’sgyrusandprogressinginboth anteriorandposteriordirectionstowardtheplanum polareandplanumtemporale,respectively.Longerfibers connecttheposteriorandanteriortemporalregions(Fig. 1.2A–C). TLFIIisalargertractcomparedtoTLFIand itsfibersarecontainedwithinthemiddleandinferiortemporalgyri(Fig.1.2BandCleft).SomefibersoftheTLF havebeenpreviouslyvisualizedinthemonkeybrain usingaxonaltracingmethods(SchmahmannandPanda, 2006)andinhumanswithtractography(Catanietal., 2013)buttheywereconsideredasbeingpartofthe MLF ortheILF.

TractographyanalysisinhumansrevealedasignificantleftwardasymmetryforTLFI,butnotforTLFII. TheexistenceofTLFinhumansisinlinewithpreviously proposedmodelsofdualstreamsforvisualandauditory processingbasedonanimalexperimentsandappliedto humancognition(Kravitzetal.,2013; DeWittand Rauschecker,2012).Accordingtothesemodels,the ventral streamsarecomposedofcorticalareasthatprocessvisualandauditoryinformationforobjectidentificationwhereastheareasofthedorsalstreamsspecialize inspatiallocalizationofobjectsandsounds.Inthemonkeybrain,theareasofbothauditoryandvisualventral streamsaredistributedalongthecortexofthesuperior andinferiortemporalgyriandsuperiortemporalsulcus. Theconceptof “stream ” impliestheexistenceofa networkinwhichspecializedneuronsarespatiallysegregatedincorticalareasbutreciprocallyconnectedby short-andlong-rangefibers(Kravitzetal.,2013).

In general,thegoaloftheventralstreamsistoprocess thearrayoflightandsoundthatenterourorgansofperceptionandderiveacoherentrepresentationoftheobjectsthat havegeneratedit,thatis,totransformlocalsensoryrepresentationsintomultisensorypercepts(Mesulam,1998; Farah,2000; DeWittandRauschecker,2012).Wesuggest thatinhumanstheTLFfibershavearolesimilartothe connectionsdescribedinmonkeys.Specifically,TLF

Imediatesreciprocalconnectionsbetweentheareasof theventralauditorystreamwhereasTLFIIhasasimilar functionfortheventralvisualstream.TLFistherefore responsiblefortheflowofsensoryinformationthattransformlocalauditoryandvisualperceptsintoglobalrepresentations.Thisflownecessitatesneuronalmechanisms suchashierarchicalprocessingandcombinationsensitivity thattransformstonotopic(orretinotopic)perceptionin earlytemporalandoccipitalsensoryareasintosemantic representationintheanteriortemporallobe(Binderetal., 2009).Tractographyhasbeenusedtodemonstratedamage to TLFIinapatientwithpureworddeafnessduetostroke (Maffeietal.,2017).Furthermore,inpatientswithprimary progressiveaphasia,abnormalitiesofTLFIandIIcorrelate withimpairmentinsinglewordcomprehensionandobject namingbutnotsentencecomprehension.

Intheventralaspectofthetemporallobe,the fusilum representsanintrinsicsystemoffibersconnectingdifferentregionsofthefusiformgyrus.Thefusilummayrepresentthecoreventralnetworkspecializedinword (Epelbaumetal.,2008)andface(Foxetal.,2008)processingwithsomedegreeofhemisphericfunctionalspecialization(leftfusilumforwordsandrightfusilumforfaces) (L€ udersetal.,1991; AlbonicoandBarton,2017).Lesions to thefusilumcanmanifestwithalexia(Epelbaumetal., 2008)andassociativeprosopagnosia(Foxetal.,2008).

The TVTiscomposedofdenseU-shapedfibers betweentheSTGandMTG.Thistractarchesbeneath theconvexityofthesuperiortemporalsulcusandispresentonlyinthemostposteriortemporalregion.Preliminarycomparativetractographyanalysissuggeststhatthe TVTisabsentinthemonkeybrainwhileinhumansisa left-lateralizedtract.Hence,theTVTrepresentsthemajor intrinsicconnectionsystemwithinWernicke’sareainthe lefthemisphereanditsdamageisprobablycorrelated withtheseverityofbothauditoryandwrittencomprehensiondeficitsthatcharacterizeposterioraphasias.

ABBREVIATIONS AF,arcuatefasciculus;EVC,earlyvisualcortex;IFOF, inferiorfronto-occipitalfasciculus;ILF,inferiorlongitudinalfasciculus;LG,lingualgyrus;MGN,medialgeniculatenucleus;MLF,middlelongitudinalfasciculus; MOLT,medialoccipitallongitudinaltract;PHG, parahippocampalgyrus;PPA,parahippocampal placearea;TIT,temporoinsulartract;TLF,temporallongitudinalfasciculus;TVT,temporalverticaltract;UF, uncinatefasciculus.

REFERENCES AboitizF,Garcı´aR(2009).Mergingofphonologicalandgesturalcircuitsinearlylanguageevolution.RevNeurosci 20: 71–84.

AlbonicoA,BartonJ(2017).Faceperceptioninpurealexia: complementarycontributionsoftheleftfusiformgyrus tofacialidentityandfacialspeechprocessing.Cortex 96: 59–72.

AranziGC(1587).Dehumanofoetulibertertioeditus,ac recognitus,ejusdemanatomicarumobservationumliber, acDetumoribussecundumlocosaffectoslibernuncprimum editi,apudJacobunBrechtanum,Venetiis[Translatedin ClarkeE,O’MalleyCD(eds.)(1996).Thehumanbrain andspinalcord:ahistoricalstudyillustratedbywritings fromantiquitytothetwentiethcentury,secondedn.San Francisco,CA:NormanPublishing].

BarrettRLC,DawsonM,DyrbyTBetal.(2020).Differences infrontalnetworkanatomyacrossprimatespecies. JNeurosci 40:2094–2107.

BartholinC(1641).Institutionesanatomicae,Lug.Batavorum, ApudFranciscumHackium,Leiden.

BastinJetal.(2013a).Temporalcomponentsintheparahippocampalplacearearevealedbyhumanintracerebral recordings.JNeurosci 33:10123–10131. BastinJetal.(2013b).Timingofposteriorparahippocampal gyrusactivityrevealsmultiplesceneprocessingstages. HumBrainMapp 34:1357–1370.

BechterewW(1900).Demonstrationeinesgehirnsmit ZestorungdervorderenundinnerenTheilederHirnrinde beiderSchlafenlappen.NeurolCentralbl 20:990–991.

BehrensTEJ,BergHJ,JbabdiSetal.(2007).Probabilisticdiffusiontractographywithmultiplefibreorientations:what canwegain?Neuroimage 34:144–155.

BeyhA,Dell’AcquaF,CancemiDetal.(2022).Themedial occipitallongitudinaltractsupportsearlystageencoding ofvisuospatialinformation.CommunBiol 5:318.

BinderJR,DesaiRH,GravesWWetal.(2009).Whereisthe semanticsystem?Acriticalreviewandmeta-analysisof 120functionalneuroimagingstudies.CerebCortex 19: 2767–2796.

BrocaP(1878).Anatomiecompareedescirconvolutions cerebrales:legrandlobelimbique.RevAnthropol 1: 385–498.

BrownS,Sch€ aferEA(1888).Aninvestigationintothefunctionsoftheoccipitalandtemporallobesofthemonkey’s brain.PhilosTransRSocLondB 303–327. BurdachCF(1819–26).VomBaueundLebendesGehirns, Dyk,Leipzig. BurgelU,AmuntsK,HoemkeLetal.(2006).Whitematter fibertractsofthehumanbrain:three-dimensionalmapping atmicroscopicresolution,topographyandintersubjectvariability.Neuroimage 29:1092–1105. CanterasNS,SimerlyRB,SwansonLW(1995). Organizationofprojectionsfromthemedialnucleusof theamygdala:aPHALstudyintherat.JCompNeurol 360:213 –245.

CataniM,BambiniV(2014).Amodelforsocialcommunicationandlanguageevolutionanddevelopment(SCALED). CurrOpinNeurobiol 28:165–171.

CataniM,DawsonMS(2016).Languageprocessing,developmentandevolution.In:PMConn(Ed.),Conn’stranslational neuroscience.AcademicPress,pp.679–692.

CataniM,ForkelSJ(2019).Diffusionimagingmethodsin languagesciences.In:TheOxfordhandbookofneurolinguistics,OxfordUniversityPress,pp.212–227.

CataniM,ThiebautdeSchottenM(2012).Atlasofhuman brainconnections,OxfordUniversityPress,Oxford.

CataniM,HowardRJ,PajevicSetal.(2002).Virtualinvivo interactivedissectionofwhitematterfasciculiinthehuman brain.Neuroimage 17:77–94.

CataniM,JonesDK,DonatoRetal.(2003).Occipitotemporalconnectionsinthehumanbrain.Brain 126: 2093–2107.

CataniM,JonesDK,ffytcheDH(2005).Perisylvianlanguage networksofthehumanbrain.AnnNeurol 57:8–16.

CataniM,Dell’AcquaF,ThiebautdeSchottenM(2013). Arevisedlimbicsystemmodelformemory,emotionand behaviour.NeurosciBiobehavRev 37:1724–1737.

CataniM,Dell’AcquaF,BudisavljevicSetal.(2016).Frontal networksinadultswithautismspectrumdisorder.Brain 139:616–630.

ClarkeE,O’MalleyCD(1996).Thehumanbrainandspinal cord:ahistoricalstudyillustratedbywritingsfromantiquitytothetwentiethcentury,NormanPublishing,San Francisco,CA.

CraigMC,CataniM,DeeleyQetal.(2009).Alteredconnectionsontheroadtopsychopathy.MolPsychiatry 14: 946–953.

CraigMC,SethnaV,GudbrandsenMetal.(2022).Birthofthe blues—theeffectsofprenataldepressionontheinfant brain.PsycholMed (inpress).

DaltonMA,MaguireEA(2017).Thepre/parasubiculum:a hippocampalhubforscene-basedcognition?CurrOpin BehavSci 17:34–40.

D’AnnaL,MesulamMM,ThiebautDeSchottenMetal. (2016).Frontotemporalnetworksandbehavioralsymptomsinprimaryprogressiveaphasia.Neurology 86: 1393–1399.

DeWittI,RauscheckerJP(2012).Phonemeandwordrecognitionintheauditoryventralstream.ProcNatlAcadSciUS A 109:E505–E514.

EpelbaumE,PinelP,GaillardRetal.(2008).Purealexiaasa disconnectionsyndrome:newdiffusionimagingevidence foranoldconcept.Cortex 44:962–974. FarahMJ(2000).Thecognitiveneuroscienceofvision, BlackwellPublishing..

FerraraNC,CullenPK,PullinsSPetal.(2017).Inputfromthe medialgeniculatenucleusmodulatesamygdalaencoding offearmemorydiscrimination.LearnMem 24:414–421. FerrierD,YeoGF(1884).XIX.Arecordofexperimentsonthe effectsoflesionofdifferentregionsofthecerebralhemispheres.PhilosTransRSocLond 479–564. ffytcheDH,CataniM(2005).Beyondlocalization:from hodologytofunction.PhilosTransRSocBBiolSci 360:767–779.