The Refugee Woman

Partition of Bengal, Gender, and the Political

Paulomi Chakraborty

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in India by Oxford University Press

2/11 Ground Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002, India

© Oxford University Press 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

First Edition published in 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

ISBN-13 (print edition): 978-0-19-947503-2

ISBN-10 (print edition): 0-19-947503-2

ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-0-19-909539-1

ISBN-10 (eBook): 0-19-909539-6

Typeset in Trump Mediaeval LT Std 9.5/13 by Tranistics Data Technologies, Kolkata 700091 Printed in India by Rakmo Press, New Delhi 110 020

To the memory of my grandparents, Rani Chattopadhyay and Birendra Chattopadhyay

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction: The Refugee Woman from East Bengal

1. The Problematic: ‘Woman’ as a Metaphor for the Nation

2. Violence of the Metaphor: Jyotirmoyee Devi’s Epar Ganga, Opar Ganga (The River Churning)

3. A Critique of Metaphor-Making: Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (Cloud-Capped Star)

4. Beyond the Metaphor: Woman as Political Subject, Women in Collectives in Sabitri Roy’s Swaralipi (The Notations)

Conclusion: Reading beyond the Refugee Woman from East Bengal

Notes and References

Bibliography

Index About the Author

Acknowledgements

It has taken me a long time to get this book out, far too long. While I finally let it go with a sense of belatedness as much as relief, looking back and recalling the support and goodwill I have had over the last many years to reach here fills me with great pleasure and overwhelming gratitude.

Many institutions and many fabulous people in them—teachers, peers, colleagues, students, support staff—have helped me to do this work. The Department of English and Film Studies at the University of Alberta, Canada, where I began this work, was an immensely enabling place to train as an academic. The Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, at Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay, where this book was completed, has been a remarkably rewarding place to work. I have continuously learnt from the graduate students whom I supervise, whose doctoral committees I sit on, and whom I have taught. I have also been fortunate enough to find spirited, generous colleagues whose friendship, shared laughter, discussions, and counsel have made my everyday academic life possible, whose support I can count on for every academic activity I undertake, whose high intellectual standards keep me on my toes, and who inspire. This account of debt, however, needs to begin earlier. The Department of English at Jadavpur University, Calcutta, which felt no less than a magical place, is where I first discovered the pleasure of scholarship and learnt the tools of my trade. The Departments of Women’s Studies and Film Studies at Jadavpur University, where I held a doctoral and a postdoctoral fellowship for seven and nine months respectively, gave me intellectual toeholds in Calcutta when I needed them the most. Dolna Day Secondary School, where I spent significant years

of my young adulthood, encouraged an early love of literature by making generous room for stories in its curriculum.

I have to take certain names specifically. Stephen Slemon, my PhD supervisor, guided the beginning of this project with characteristic élan. The work additionally benefitted from the intellectual acuity and support of Heather Zwicker and Onookome Okome, members of my doctoral committee. Rajeswari Sunder Rajan was the kind of examiner a doctoral student may only dream of: her incredibly encouraging and incisive feedback, including a detailed examiner’s report with specific suggestions about how to take the work forward, greatly facilitated the making of this book. The two anonymous reviewers assigned by Oxford University Press (OUP) provided useful comments that made me revise the work more rigorously than I would have managed on my own. Certainly, the work could not have become a published book without professional support: for this I acknowledge the work of the team at OUP, who responded to my needs and requests with kind consideration.

Over the years, on the strength of friendship and collegiality, several people read parts of the manuscript in its many stages. Foremost I recall Mridula Nath Chakraborty and Madhuparna Sanyal, who enthusiastically read the whole, long manuscript in its first iteration, as it grew, and offered extensive commentary; it was their intellectual curiosity and emotional support that propelled me along. I am forever indebted to Madhuparna’s kindness in a time of crisis. I also know that, whatever the strength of the work now, it would have been poorer work if it did not have a reader as sharp as Mridula at its heel. Paramita Brahmachari and Sharmila Sreekumar willingly read many pages in the last few days and saw me through to the final submission. Debjani Bhattacharayya, Melissa Jacques, Ramesh Bairy, Ratheesh Radhakrishnan, and Subhajit Chatterjee gave their invaluable feedback on sections of this book at various junctures. Sharing my work with Debolina Guha Majumdar, Prabal De, Shefali Moitra, and Sreyashi Deb Chatterjee greatly enabled me. Maithreyi M.R. looked over a sample of my writing and helped

me reach a few critical copy-editing decisions. Dayadeep Monder read every page of this book at one point or the other, in multiple drafts. Discussions with these generous people and their many interventions have left their mark on this work.

In a deeply productive half-year spent in Calcutta, now a decade back, a field I had been digging for some time at last yielded a project with a focus and some of its contours. Fondly and with tremendous sense of gratitude, I recollect that Jasodhara Bagchi, whose loss I feel acutely at this moment, and Sibaji Bandyopadhyay gave me advice that shaped my project in decisive ways. Among those who benefited this project by giving their time to listen, discuss, question, advise, provide bibliographic information, and put me in touch with other researchers were Abhijit Sen, Amlan Dasgupta, Himani Bannerji, Madhuja Mukherjee, Moinak Biswas, Paromita Chakravarti, Rajarshi Dasgupta, Sarmistha Dutta Gupta, Sourin Bhattacharyya, Subharanjan Dasgupta, Sudeshna Bannerjee, and Swapan Chakravorty. Although Arindrajit Saha, the great raconteur, did not discuss this project with me at any point, I probably could not have written this book, especially the first chapter, if I had not heard him tell numerous stories of old Bengal, of old Calcutta, and its babus. Many people were forthcoming with copies of articles, books, and films from their personal or institutional collections: I would like to acknowledge that Abhijit Gupta, Gargi Chakravartty, Malabika Dhar, Manas Ray, Miratun Nahar, Moinak Biswas, Pulak Dhar, and Sujit Ghosh provided me with particularly useful material. Buddhadeb Chattopadhyay and Mitra Ghosh collected and bought books according to my lists, and ferried or sent them to me long distance, multiple times. The librarians at the National Library in Calcutta and various libraries at Jadavpur University were always liberal with their assistance.

For opportunities to present parts of this work, experiences which always added something valuable to the content and confidence of my articulations, I am grateful to Navaneetha Mokkil for inviting me to the School of Language, Literature and Cultural Studies, Central University of Gujarat; Supriya Chaudhuri to the Department of

English, Jadavpur University; and Anna Yeatman to the Centre for Citizenship and Public Policy, University of Western Sydney. The audience on these occasions as well as at several conferences where I presented parts of this work were tremendously helpful with comments and questions. I would particularly like to remember interlocutors at the ‘Partition/Violence/Migration’ symposium in Cardiff University (2015), the seminar on ‘Rabindranath Tagore: In His Time and Ours’ hosted by the Centre for Comparative Literature in Hyderabad Central University (2012), the Department of Film Studies in Jadavpur University (2010), the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences in IIT Bombay (2010), and ‘Thinking Beyond Borders’, the annual conference of the Canadian Association for Commonwealth Literature and Languages in the Congress of Humanities and Social Sciences, hosted by University of British Columbia (2008). I need to thank Mridula Nath Chakraborty, yet again, for inviting me to the ‘Being Bengali: At Home and in the World’ workshop at the Writing and Society Research Centre at the University of Western Sydney (2010). The paper I presented there is not part of this book, but it helped me to further understand the figuration of the refugee woman in its many iterations: I learnt enormously from participating in the workshop, and the many conversations it enabled.

I gratefully admit, that I parted with the manuscript I had been holding close to my chest for a very long time owes in no small measure to the persuasion of the people at OUP. To get that far, however, I have needed ample encouragement, multiple reminders, and many discussions on choosing a publisher, writing a proposal, understanding a book contract, and other aspects of bookmaking. I am thankful in these regards to the indulgence of friends–colleagues–advisors Abhijit Gupta, Cara Murray, Kushal Deb, Maithreyi M.R., Navaneetha Mokkil, Padmini Ray Murray, Ramesh Bairy, Stephen Slemon, and Vaijayanthi Sarma. In this pursuit, I have also relied upon Ratheesh Radhakrishnan to handhold me through many small and big decisions, as well as Amit Upadhyay, Sharmila Sreekumar, and Shilpaa Anand to keep me grounded and

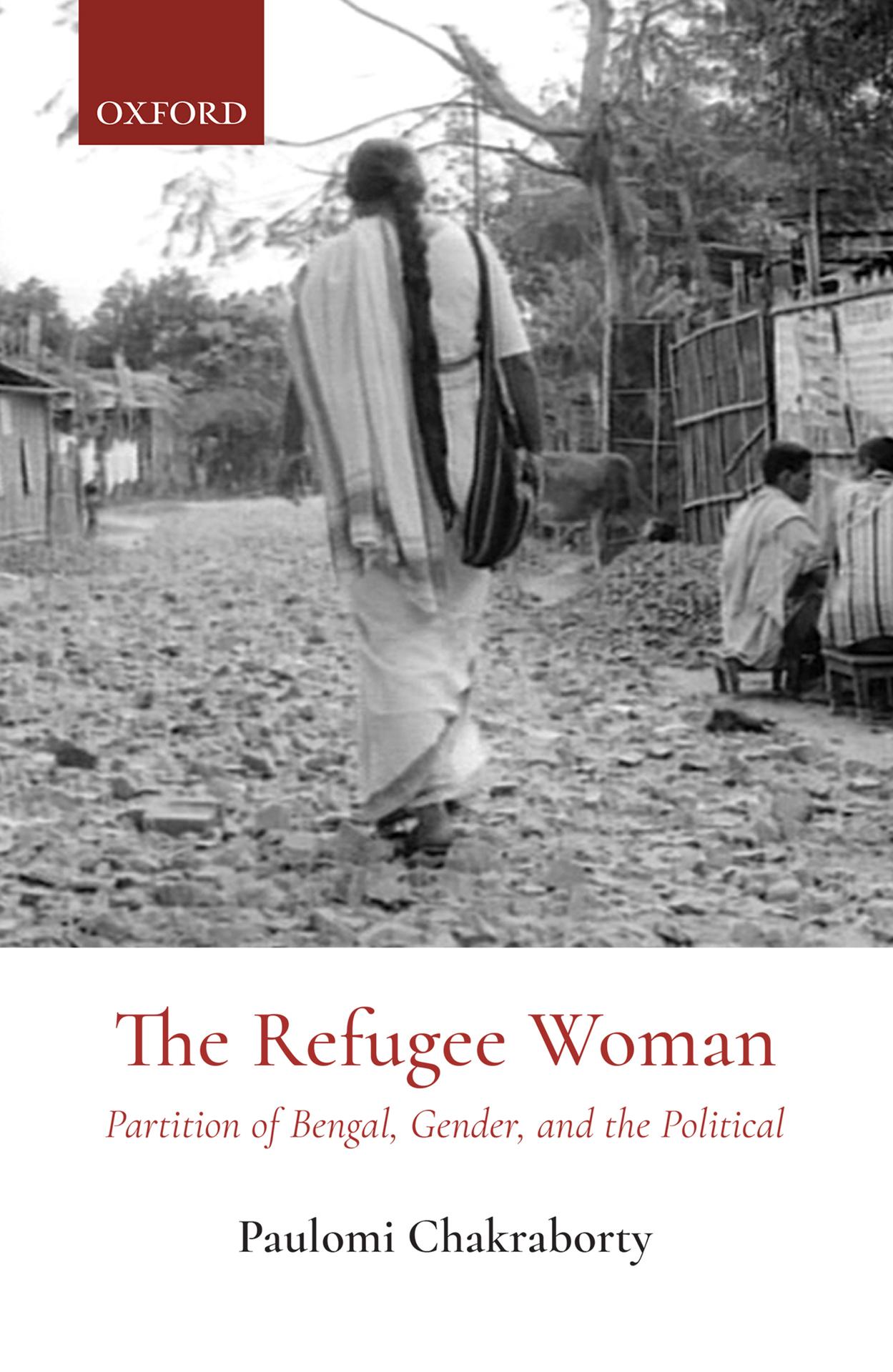

in good humour. For the cover of the book, Paramita Brahmachari and I came upon the idea of using the refugee woman in the last sequence of Meghe Dhaka Tara together, in one of our many heady conversations, years back even before the first draft was complete; but the visual plan is hers. I am grateful to Surama Ghatak and the Ritwik Memorial Trust for permission to use the still from Meghe Dhaka Tara, as to Paramita Brahmachari, Sreyashi Dastidar, and Soma Mukhopadhyay for their help in obtaining the above permission from Surama Ghatak.

To add the customary but important statement: for all those remembered above have done, none of them are responsible for any shortcoming of this book.

For several financial awards, I thank the University of Alberta. I thank the Government of India and the Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute for their doctoral and postodoctoral research fellowship awards. I thank IIT Bombay for its financial assistance, especially the Industrial Research and Consultancy Centre for the seed grant.

My chapter, titled ‘Gender, Women and Partition: Literary Representations, Refugee Women and Partition Studies’, in Routledge Handbook of Gender in South Asia (Routledge, UK, 2014) draws a few of its sections from an earlier version of this book’s manuscript. I thank Leela Fernandes, the editor, for her feedback that not only strengthened the chapter but also this book, and I thank the publishers for permission to reuse this material. I would also like to note with thanks that a section of the second chapter was first published as an essay titled ‘Politics of Representing Gender Violence: Jyotirmoyee Devi’s The River Churning’, in the book, Disnarration: The Unsaid Matters, edited by Sudha Shastri and published by Orient Blackswan Private Limited in 2016.

Finally, I need to thank those I do not quite know how to. Here is saying thank you all the same to the following: My few close friends, almost all of whom I have already named here, for sustaining me with understanding, camaraderie, affection, humour, and care. Among those I did not, Kshounish Palit and Robin Durnford, for their

enduring friendship. For acts of largesse that can neither be counted nor named, my large, extended family, especially my sister Jhelum Ghosh and my mother Mitra Ghosh. For living the making of this book with me, my companion, fellow academic, and much else, Dayadeep Singh Monder—Misha. For graciously sharing my attention and energy in the first year of his life with the last year of this book, for learning early to sleep well on most nights, for bringing me new hope: Zayn Anhad!

Introduction

The Refugee Woman from East Bengal

Writing on how he created Nita, the protagonist of his first Partition film Meghe Dhaka Tara (‘Cloud-Capped Star’, 1960),1 Ritwik Ghatak recalls ‘a girl, a very ordinary girl, tired after day’s work [who] waits often near [his] house at the bus or tram stop, a lot of papers and a bag in her hand’. He describes how ‘her hair forms a halo around her face, and some cling to her face because of perspiration’.2 This commonplace presence in Calcutta of the 1950s of an ‘ordinary girl’ returning from work at the end of the day from an office job was particularly a post-Partition phenomenon, indicating a new social category that had come into being in West Bengal, that of the ‘refugee woman’. In Meghe Dhaka Tara, Ghatak provides perhaps the most enduring image of the refugee woman, a central figure visible in the sociopolitical landscape in West Bengal in the years immediately following the Partition. The cultural imagination of this figure is multivalent and textured through its many historical trappings. This book locates it as a particularly rich site for examining the gendered affects of the Partition as well as for tracking the shifting valence of the signifier ‘woman’ in West Bengal through the turbulent decades of the mid-twentieth century.

For the Hindu-Bengali middle classes, whom it is more apposite to call bhadralok in the Bengali language because the imagination of ‘the middle’ does not adequately annotate its class and caste composition or history of formation,3 these decades were a time of palpable transformations in gender relationships. Colonial modernity of the bhadralok, shaped through negotiations with propriety as appropriate for a property-owning class, put definite limits to idioms

of being and behaviour for women. Now its gender mores were to undergo a significant change, with the refugee woman from East Bengal/East Pakistan at the heart of this change. Predominantly due to the heightened economic needs of their families in these uncertain times, and no doubt also using the opportunity that the inevitable slipping of the more rigid patriarchal boundaries enabled, women of bhadralok families, with refugee women from East Bengal in the vanguard, left home to earn a living. Sometimes they found salaried jobs; sometimes they joined wage labour.4

Even within the confines of the bhadralok imagination, this transformation in the intimate gender relationships within the family unfolded against a larger political backdrop. As the number of refugees in West Bengal grew, the undivided Communist Party of India5 played a strong role in influencing the refugee movements, and in turn the refugees contributed to the growth of the political Left in the state, though this relationship was often a tense one.6 The political activism of refugee women—beginning with basic demands for food and shelter—was integral to these developments: ‘[T]he immediate concerns of these women … got linked to the issues of women’s struggles in general and got incorporated into the mainstream women’s movement’ (Chakravartty 2005: 37). A longer history of women’s political activism that began with the man-made famine in Bengal in 1943 and the Tebhaga peasant rebellion of 1946–7 and 1948–9, events I shall discuss ahead, found newer iterations in refugee movements. These intertwined histories underwrite the imagination of the refugee woman in many cultural narratives of the Partition in West Bengal.

The Partition was one of the most violent events in the history of the Indian subcontinent. It claimed hundreds of thousands of human lives, reaching proportions of genocide in some parts; the estimate of the dead varies from the official British figure of 200,000 to 2 million by later Indian estimates (Butalia 1998: 3). Till this day, the ‘population exchange’ between the newly formed India and Pakistan (both East and West) remains the largest instance of forced and coerced migration in global history. In the eastern region alone,

millions of Hindus—no one knows exactly how many—crossed India’s eastern border with East Pakistan into the new state of West Bengal and into the states of Assam and Tripura. The ‘official, and improbably conservative, estimate for the period of eighteen years from 1946 to 1964 places the total at just under 5 million’ (Chatterji 2007a: 105). In the same period, ‘a lesser number of about a million and a half Muslims left West Bengal, Bihar, Assam and Tripura’ to go to East Pakistan (Chatterji 2007a: 106). In Bengal province, just as in Punjab, the bifurcation literally cracked into two not only territory but also a shared history, culture, and polity.7

As is overwhelmingly remembered, women of all ages became specific targets of violence of the Partition. Imaginations of the refugee woman carry this history of trauma in many iterations. In other instances, the citation of the gender violence becomes an opportunity to further patriarchal prerogatives. This book, like many others in what today is being called Partition studies, suggests that the overwhelmingly gendered form of Partition violence can only be explained in its connection with forms of cultural nationalism and a shaping of the gendered discourse of the nation in the subcontinent. Against the long and limiting history of the imagination of ‘woman’ that had been shaped by dominant forms of cultural nationalism, it locates a radical potential in the imagination of the figure of the refugee woman.

There is, of course, not one homogenous kind of nationalism; complications posed by participation of Muslims and other ‘others’ in nationalism notwithstanding, the cultural nationalism that I refer to was patriarchal, class-privileged, and caste-Hindu in character. It gathered a specific idiom in late nineteenth century Bengal and continues through the early twentieth century into the postIndependence/post-Partition years. It was deeply influential in the later course of all nationalisms not only in Bengal, but elsewhere in India as well. A salient feature of this nationalism was that, within its imaginary, the nation itself is a woman, as is particularly visible in the case of ‘Mother India’. The concomitant slippage in nationalist discourse is that in it woman becomes the sign of the nation. The

figure of the refugee woman, I propose, allows us to glimpse the tense interface between woman as a figurative category (as a sign of the nation) and woman as a historical-material category in relation to the political, which gathers sharper visibility at the time of the Partition. I suggest that the figure of the refugee woman can interrupt the economy of representation of woman as a sign of the nation and signals or stages the struggle to push it towards that of a citizen-subject, a member of a political collective.

Largely, this becomes possible because the figure of the refugee woman, as inevitably shaped by the material history of refugee women in political and civic life in post-Partition West Bengal, pushes us to a different imagination of women as constitutive of a collective. This is particularly enabled because the refugee woman’s political struggle is not within the framework of nationalism, indeed it is often against nationalism, and can even dislodge nation as the primary register of political imagination. The figure of the refugee woman alerts us to forms of civic and political belonging to which women must stake a claim, other than those conditioned and allowed by nationalism or nation as the primary referent of political life.

I also posit the refugee woman as a figure who allows us to read what constitutes the category woman in the discourse of the nation as it transitioned from a colonial to an independent nation-state. On the one hand, the figure points out the continuities between the two forms of nationhood in perpetuation of the gendered everyday world. On the other hand, it interrupts and intervenes into the colonial ‘legacy’ and forms a location of political praxis in the newly independent nation-state. Further, I suggest, in constituting woman as a historical category, the figure of the refugee woman throws into acute critical relief the conditions that hold the ‘normal’ historical relationship between woman and the nation in place, and she disrupts the hegemony of gender that is foundational in the perpetuation of ‘the everyday’ of the nation. Therefore, the analysis of the refugee woman this book offers is also an exploration of the gendered, historical ‘everyday’ of the nation in relation to the

Partition and illuminates the links between the Partition and nationalism, and the process of nation formation in the Indian context.

Indeed, this book also aims to show that the imaginary of political collective at the heart of the dominant discourse of the Partition is also gendered similarly, where woman symbolizes the collective. In this particular regard, there is no significant opposition in the nationalist discourses, communal8 discourses, and Partition. Politically different, even opposed, as each of these political and discursive threads are from each other—even when these differences are tremendously significant—they all converge on one point: woman remains the symbolic site on which other political projects—rarely about women themselves—get mapped, negotiated, contested, won, or lost.

I focus, in this book, on three major texts of Bengal Partition that offer us the imaginary of the refugee woman. I choose to examine these three texts in depth in particular because, in my reading, they allow us to see how a different way of imagining woman is being shaped in the decades immediately after the Partition. More specifically, their figuration of the refugee woman, in my reading, intervenes in the dominant discursive formulation of woman as the nation/community/collective. These texts are Jyotirmoyee Devi’s novel, Epar Ganga, Opar Ganga (that has been translated as The River Churning: A Partition Novel, 1967); Ritwik Ghatak’s film, Meghe Dhaka Tara (‘Cloud-Capped Star’, 1960); and Sabitri Roy’s novel, Swaralipi (The Notations,9 1952). It is important to underscore that these three texts are not representative examples of dominant Partition discourse, including the literary, which can be in continuity in its imagination of woman with dominant nationalist discourses. I shall elaborate further on this point and the selection of these texts later.

These texts are stories of and represent the Partition narratives of the bhadralok Hindu-Bengalis in West Bengal on the Indian side. The refugee characters in these texts are based on historical groups of the East Bengali, Hindu refugees who arrived in West Bengal and

elsewhere in independent India from East Pakistan. While the rest of the nation got citizenship of a free country, these people were among ‘midnight’s unwanted children’, in Nilanjana Chatterjee’s phrase.10 They found themselves on the ‘wrong side’ of the border when India awoke, in the famous phrase of the first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, ‘to her destiny’. Overall, the elite among them, who form the prototype in Bengali Partition literature from West Bengal,11 occupied a complex position lying at the intersection of privilege and powerlessness. On the one hand, they belonged to a stratum of the bhadralok section and had class and caste privilege. On the other, their status as refugees in West Bengal mocked this privilege. Many lived in abysmal conditions in refugee colonies and camps and faced problems in ‘resettlement, in finding employment, and in supporting large and growing families’ (Chatterji 2007a: 296). In any case, even for those who eventually found a foothold and established themselves financially and materially, the cultural stigma of being refugees from East Bengal lingered. As it is, the Bengalis of East Bengal were thought to be culturally inferior, rural yokels with peculiar dialects, by the bhadralok population of Calcutta, and were referred to by the pejorative term bangal. This perception predated the Partition, but if this was a product of cultural hegemony earlier, what changed after the Partition is that the evocation of the term ‘bangal’ now acquired an element of anger and hostility. The refugees, with their naked needs and seemingly insatiable demands, were unwanted in Calcutta and were thought to be dirtying its public space and polluting its bhadralok culture. In any case, the loss that constituted the refugees ontologically and haunted them cannot be reduced to just the material. The loss of home, a polity, and a connection to the land, for not only those who found themselves on the wrong side of the new border after the Partition but also for those East Bengalis who were physically settled in Calcutta at the time of the Partition, remained indelibly intertwined with their lives and was passed on to their children and grandchildren.

The figure of the refugee woman I evoke here is a doubly marginalized figure, as both a refugee and a woman. Yet, in my given texts and context, she is not a subaltern; she is inscribed as a marginal, gendered other within an elite class and caste demography of the Bengali bhadralok. Given her historical profile, the figure of the refugee woman in the texts I examine is at once within and without national imagination, and both a marginal figure as well as a figure around whom discourses of belonging and rights can crystallize. That is to say, she is disenfranchised within a national discourse, but also remains crucially visible within that very discourse. Therefore, I read the refugee woman as a liminal inside/outside figure who occupies the intersection of power and powerlessness in a national context, analysing which provokes insight into understandings of the particularities of power—and the lack of it—that define the relationship of women with the discourse and practices of normative nationalism.

The figure of this refugee woman is clearly not an exclusive location; indeed, it is a privileged one, for probing the Partition and its connection to the dominant imagination of the national. One could also argue, quite rightly, that the core body of ‘us’ which spearheaded the dominant cultural nationalism excluded, marginalized, and ‘othered’ other figures, not just particularly that of the Muslim but also the peasant and the subaltern classes and castes, to differing degrees. By that logic, we can take any of these othered figures and track its construction and usage through cultural nationalism preceding the Partition, as well as later in the Partition discourse, to gain insight into the Partition and the nation-making process. Further, the category woman is not exclusive to genteel caste-Hindus; a study focused on gender should rightly engage with other demographics as well. In fact, one may contend that it is far more relevant to conduct this enquiry not just around figurations of other ‘others’, but outside the confines of a bhadralok selfimagination and self-description.

We should remember in this context that the abject condition of the subaltern refugees was further aggravated by the state

government’s denial of assistance by ‘repeatedly [trying to] restrict the definition of who could claim to be a refugee’, to an astonishingly narrow one of only those who reached India between June 1947 and June 1948 and managed to register themselves as refugees by January 1949, and to ‘limit its liability’ to provide relief or rehabilitation (Chatterji 2001: 80).12 In that sense, to be called a refugee by the state itself becomes a privilege, inaccessible to the subaltern. And yet, ‘in the first wave of Hindu refugees to cross over into West Bengal … the overwhelming majority were drawn from the ranks of very well to do and the educated middle-classes’, who qualified for the refugee status, and the subsequent waves and trickles who were progressively poorer, down to the ‘humble peasant’, sharecroppers, and landless agricultural labourers, did not (Chatterji 2007a: 115–19). Indeed, ‘as time passed, it became increasingly the case that the middle-class refugees from East Bengal formed only a part of the refugee population as a whole, and an increasingly small fraction in the camps where the most powerful refugee movements came to be organized’ (Chatterji 2007a: 271). The exclusion of the status-less refugees was not just from the state’s imagination of who was a legitimate refugee, deserving of assistance; the bhadralok imagination of ‘the refugees’ also mostly fails to include them. For instance, in Bengali refugee fiction, the subaltern refugees are rarely visible and, when present, they are peripheral figures, not the protagonists of the story. I hope the scholarship on the Partition, not just in Bengal, such that it is a domain of knowledge production, would robustly address the complex particularities of class and caste, along with gender and sexuality, in constituting this subaltern history/story of the Partition, as is now beginning to be undertaken by a few.13 However, it is not a project this book includes in its scope.

While circumscribed in this significant regard, I still locate the ‘refugee woman’ as a key figure for analysis, with certain gains in mind. This choice is certainly not rooted in any perception of a greater degree of victimhood or marginalization for the figure that the bhadralok imagination configures as the refugee woman.

Indeed, the term ‘refugee woman’ that this book analyses and names for this purpose is a product of bhadralok self-imagination, lying within a sense of its own demography. I focus on this refugee woman by recognizing the centrality of the savarna (caste-Hindu), middle-class Bengali woman, the bhadramahila, to normative anticolonial nationalism in Bengal. I perceive that, although not exclusively so, the figure of the refugee woman, as it emerges due to contestations from within the dominant discourse, provides a crucially important point of entry into an enquiry from within the discourse. It has all the limitations that come with a gendered enquiry from within: if its discussion comes to bear upon all women to a varying extent, the woman who forms the basis of the discussion is inscribed by class, caste, and sexuality; she is not a universal figure. On the other hand, because she is both within and without power and otherwise an in-between figure as I described earlier, she allows a specific insight into the dominant processes of nation-making that cannot be found from other locations entirely outside. I find this insight critically rich.

Let me explicate the terms and concepts I have used in this book and the way I have used them. To elucidate the two different concepts of the relationship of woman and the nation I have evoked earlier, I find it useful to draw from the distinction Roman Jakobson makes between the metaphor and the metonym in his famous essay in Fundamentals of Language (1956). Jakobson glosses the metaphor and the metonym as follows: metaphors are representative tropes that function on the principle of substitution, while metonymy, in contrast, functions on the basis of association, relation, membership, and constituency. In metaphoric tropes, there is a replacement of one figure with another; the absent, abstract figure is made available parasitically on the body that is present. Using this distinction, we can think of how woman imagined as a sign of the nation becomes a metaphor In the process, at the level of signification, that woman is also a subject comes under erasure. I

have, therefore, named the two senses of the term ‘woman’ sign and subject, respectively. This is, of course, as rhetoric to mark difference and not to suggest that, when woman is posited as a sign, available subjectivity of women actually evacuates. On the contrary, then, the subject positions available for flesh and blood women have to be calibrated and regimented such that its passivity rather than agency is overtly emphasized; or, if agency is at all evoked, it has to be done within particular parameters, such as that of chastity, or motherhood, and so on. In contrast to woman as a sign or a metaphor, if the relationship to the nation is imagined as a metonymic one, women are recognized as constitutive of the whole, as members of a nation and the nation-state. Women then still represent the nation, but such representation is in the more political sense of representation, which recognizes participation, desire, and agency. In metonymic imagination of women, there is also more room to imagine political collectives other than exclusively as the nation.

It is important to underscore that the metaphor and metonymic are not entirely exclusive and, being modes of imagination, are not ontologically fixed. What is imagined as a metaphor can also be imagined as a metonym in a different time or context; the two may even overlap. I am deploying the pair heuristically, not as absolutes. I should also emphasize that both woman as a metaphor and woman imagined as metonyms are significations and belong to the realm of the discursive/cultural.14 The metonym is a signification of the material within discourse. However, even as I apprehend this point, I wish to argue that the imagination of woman as a metonym figuratively gestures to not only the historical category of women, but also to a specific history of the refugee women in the given context, especially with different subject positions that becomes possible to imagine, given the history of the communist women in Bengal. That is to say, the metonym is a fiction, but this fiction allows subject positions that correspond to the historical and the material rather than reify the subject position as in the case of the metaphor. Overall, whether as metaphor or metonym, both are cases of

representation and as such, they shuttle between the real and the imaginative. As Rajeswari Sunder Rajan glosses ‘representation’ in her book, Real and Imagined Women:

[T]he concept of representation … is useful precisely and to the extent that it can serve a mediating function between the two positions, neither foundationalist (privileging ‘reality’) nor superstructural (privileging ‘culture’), not denying the category of the real or essentialising it as some pre-given metaphysical ground for representation. (1993: 9)

Analytically marking the difference between woman as a figurative category (woman as a sign of the nation) and woman as the historical-material one (women in India/Bengal) is centrally important to this book. I have used the term woman in singular to indicate the figurative category in the discursive realm alone, as a sign, a metaphor, as the case of woman as the nation certainly is.15 On the other hand, I have used the plural women to indicate woman as a historical-material category, real women, metonymically related to the collective, if we will. This is primarily strategic to name the difference and to facilitate the discussion. That said, my choice of plural—women—as the real (in the sense Sunder Rajan uses) is not arbitrary: in most instances in this feminist study, women have been evoked in the collective rather than in the singular. In spite of my attempt to clarify my usage, the residual confusion, if any, however, indicates the historical overlap of these separate usages of the term woman/women in cultural–textual–linguistic discourses with which this book engages. Further, I have deliberately called woman a sign representing the nation, not just a symbol. This is because, although woman can often be used as the symbol of the nation, the usage of woman as the nation circulates in the discursive and semiotic realms, including in the banal, ‘everyday’ speech, without necessarily acknowledging or drawing attention to the fact that it is a figurative category, a trope.

Nation is the most central and normative collective in the given juncture in history; it is also, therefore, central in this book. What is also significant for this discussion is that gender is integral to a

nation’s conception as an ‘imagined community’.16 As feminist scholarship has well established, all nations and all nationalisms are gendered: the people who imagine the nation and the people who are imagined as the nation are also gendered.17 Although women are instrumental to the process of nation-founding and nationmaking, and particularly vulnerable when such nations and their imaginations are contested, historically they have seldom been included in the imagined community as the prototype of the national subject or the citizen, fully or equally with men.

I understand the nation to lie sometimes in contiguity with the community and sometimes in concurrence. In the years before Independence, when Indians were subjects of the empire but not citizens of a sovereign nation-state, the category community, constituting civil society, was acutely political. The family, as the primary patriarchal unit, is also foundational to imaginaries and power structures of both community and the nation. In that sense, the community–nation dyad is itself a part of the family–community–nation triad. Since my aim is to dwell on the question of the collective, the family as a category has not always remained visible in the discussion, but it has always remained central to my conceptualization of sociality In contrast, community is the most immediate of collectives. When it comes to women, in my given context, I have not found any pressing opposition between family, community, and the nation in relationship to women; their interests seem to me to lie in a spectrum, distinct but largely overlapping.

Correspondingly, I do not find a radical charge in community as some have. Rather, I find useful Jasodhara Bagchi’s critique of the ‘tendency … in current discussions on women’s rights and citizenship … to pit the community as a greater ally of women as against the nation-state posed as site of harsh surveillance’ and when she points to ‘the nation–community nexus’ (2003a: 20). My understanding of the term ‘community’ also shares ground with the critical vocabulary of several strands of feminist criticism that problematize the naturalness of ‘community’ and argue that ‘it is a vertical patriarchal construction claiming self-referential

genealogy…. It is hierarchical and non-democratic and does not recognize time’ and go on to locate the community ‘within the nation’ (Ivekovic and Mostov 2004 [2002]: 12). My understanding of community is also close to that of Gyanendra Pandey, who argues that communities are ‘constructed … through a language of violence’ (2001: 204).18

However, Veena Das’s anthropology-based distinction between ‘the community defined on basis of filiation and the community defined by affiliative interests’ is useful as a qualification to my usage of community (1995: 114). She explains the two types of communities through examples: ‘ethnic or religious minority’ for the former; and ‘women’s groups’ or ‘the community of women’ for the latter (107). By thinking of women’s groups as ‘affiliative community’, Das wants to recuperate ‘community’ if and when the ‘possibility of interrogating male definitions of the community’ by female members within the community arises (107). Except in these exceptional conditions, I take the normative usage of the term ‘community’ to indicate a filiative one, that is to say, one where the basis of the collective is myths of blood ties and genealogy. A useful reminder that ‘women’ are best thought of as a ‘category’ and not a community is Sunder Rajan’s emphatic citation of Etienne Balibar’s formulation that ‘from an emancipatory stand point, gender is not a community’ (emphasis in Balibar 1991: 67; cited in Sunder Rajan 2003: 14). As Sunder Rajan writes:

actual collectives of women may be discovered, no doubt, in some historical and social contexts…. But beyond such contingent situations, it is not clear whether women have any associational tendencies with other women in any social setting, belonging instead more ‘naturally’ to mixed-gender (and hierarchical) families and communities. (2003: 14)

Indeed, when we assess both community and nation as collectives from the perspective of women subjects, the patriarchal character of both becomes apparent.

In the given context, the state also displays this patriarchal structure. Nevertheless, the state cannot be dismissed offhand for a

feminist project not only because the liberal promise of the state for women far exceeds that of the nation, but also because there is no political alternative available to the state. The state is often, at least potentially, the only guarantor of women as right-bearing individuals. Sunder Rajan cautions, using Catherine MacKinnon’s words, ‘feminism has no theory of the State’ (cited in Sunder Rajan 2003: 8). Sunder Rajan points out that feminist critiques of the state have not suggested political alternatives to ‘the institutions of nation-state, law, and citizenship, beyond their reform…. There is no equivalent in “sisterhood” to “workers of the world, unite!”’ (8). Like Sunder Rajan’s earlier book, Real and Imagined Women (1993), this book is not, given its focus on the ‘cultural’ imaginaries and texts rather than on policy and law, a direct engagement with the issue of the state. However, I would like to note that, if not directly, this book has tried to remain alive to the concept of the state as a larger context in its probing of the question of political collectives.

The larger question that I want to ask is about the relationship between woman and the political, including political institutions. I use the term political broadly, as relating to the larger polity, including ways, styles, idioms, imaginations, cultures, practices, as well as narratives, of being and belonging within a polity. The question of collectives—collective lives, experiences, and the imaginations of polity—therefore assumes importance in this book. As I have alerted, it is a matter of historical description that the imaginary of political collective that occupies the centre stage of the analysis is the nation, which emerges as an institution of colonial modernity and as the normative imaginary of a political collective that validates an independent postcolonial state. However, the concept of the nation has come in critical contact with and against other concepts of collectives in the discussion of Partition texts in the body chapters. A gendered collective of ‘women’ is the main other collective, from my reading of the Partition texts, that has taken up the nation. It is not a direct contender for the state for reasons explained earlier, but it has served as the privileged location from which to read the nation. A collective of ‘the masses’ in a