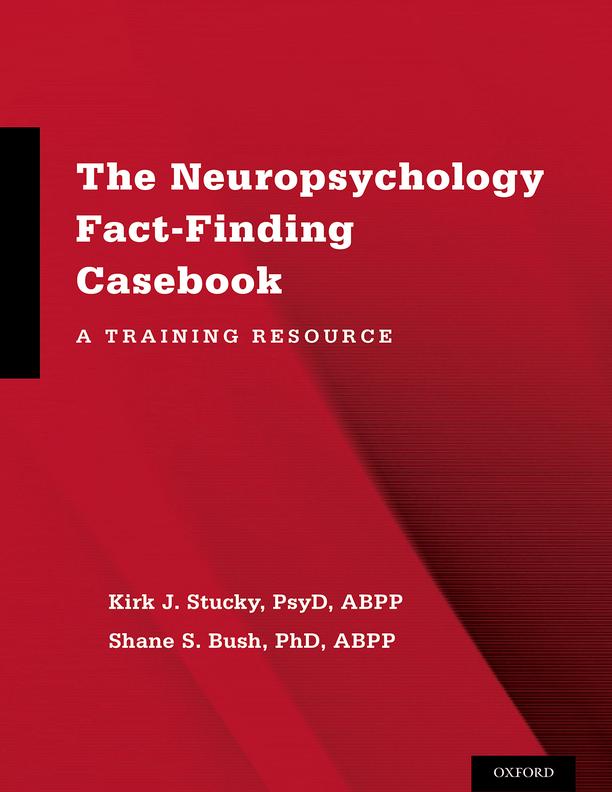

1 Introduction

Formal training in clinical neuropsychology introduces trainees to diverse patient populations with a variety of diagnostic conditions and disorders. Learning to competently apply a structured, factfinding approach to case conceptualization, differential diagnosis, and treatment planning is an essential goal at all levels of the training experience. However, to date, there has been little in the way of a standardized approach to fact-finding that training programs at various levels can use to help trainees develop such skills, leaving supervisors in various programs to teach their own versions of the methodology. We believe that neuropsychological training and ultimately the patients served will benefit from a more uniform approach to using clinical fact-finding exercises as a teaching tool.

This book was designed to be a resource for supervisors, trainees, and training programs in clinical neuropsychology. The volume provides 24 adult/geriatric fact-finding cases (one for each month of a 2-year residency) based upon real patients evaluated by the authors in various settings. Aspects of the history, demographic information, and other unique identifiers have been intentionally modified to safeguard patient confidentiality and maximize learning opportunities. An attempt has been made to present the cases in a stepwise fashion, with progressive increases in complexity, to address the training needs of clinicians at various levels of professional development (i.e., student/intern, resident, independent practitioner). However, given differences in clinical experiences, some trainees and professionals may find some of the earlier cases to be more challenging or complex than later cases. Similar to common neuropsychological practice in the United States, a flexible battery approach was utilized with common core battery measures administered in most cases but tailored to the specific needs of a given patient (Rabin, Barr, & Burton, 2005; Sweet, Moberg, & Suchy, 2000). A case summary, list of diagnostic possibilities, and expected recommendations are also provided.

Following this information we offer focused questions that supervisors can ask or trainees can ask themselves to further facilitate the learning experience. These questions are organized by the competency areas of (a) evidence-based knowledge, (b) assessment, (c) intervention, and (d) consultation. In each competency area there are questions designed for trainees at different developmental stages (i.e., student/intern, resident, and ready for independent practice), but supervisors can modify the questions or create new ones based upon their specific goals. Following these questions, each case has a brief “Outcome” section that describes the final diagnosis and outcome after the evaluation was completed. Finally, a more specific discussion of various aspects of the case is provided to highlight critical teaching points and stimulate discussion. It is important to emphasize, however, that the primary purpose of each case is to help trainees learn critical thinking skills through a fact-finding process rather than provide extensive coverage or teaching regarding various disorders and/or conditions. We also anticipate that, following completion of the fact-finding exercise, the supervisor and trainee will most likely identify specific areas which require further attention and identify specific ways to address them (i.e., didactics, readings).

We primarily selected cases that required relatively comprehensive evaluations conducted in an outpatient setting. However, there are several cases that highlight differential diagnosis in hospitalized patients with significant and obvious neurocognitive compromise. In these cases, brief screens are more

appropriate and preferred. We believe their inclusion in this casebook was appropriate as neuropsychologists are often actively, and even primarily, involved in inpatient practice. It is important to emphasize that the cases in this book do not contain a score-by-score analysis or exhaustive explanation and discussion of every diagnostic or treatment possibility. Instead, critical teaching points deemed central to case formulation were intentionally selected for more detailed discussion. Considering that a full data set from these cases is presented, we anticipate that supervisors using this volume might identify or choose to stress different case aspects that we did not emphasize.

This book is intended to appeal to a variety of consumers in neuropsychology, including graduate school instructors, supervisors, trainees, and training directors. Other neuropsychology professionals may also find value in the book. Additionally, candidates preparing for the board certification oral examination in clinical neuropsychology could potentially use this book in their preparation. However, it is important to emphasize that because the cases are primarily designed to assist supervisors in training settings, the format for these fact-finding cases differs somewhat from the formats used for oral examinations conducted by the American Board of Professional Psychology (ABPP) clinical neuropsychology (ABCN) specialty board. The following section contains a brief user’s guide for The Neuropsychology Fact-Finding Casebook: A Training Resource.

Case selection and Content Criteria

The cases presented in this book are based on actual cases evaluated by the authors. All names and identifying information have been modified or removed. Also, to protect confidentiality, maximize the training experience, and enhance overall teaching utility, minor modifications to the history, observations, and/or test scores were made. The criteria for case selection followed several basic rules for inclusion:

1. The cases are adult/geriatric.

2. The cases require the application and integration of specific psychological, neuropsychological, clinical, rehabilitation, and/or health care knowledge. Some cases emphasize treatmentrelated concepts, whereas others focus on differential diagnosis.

3. The cases include sufficient emotional, behavioral, and psychological data to allow trainees to identify the optimal conceptualization, appropriate treatment plan, and recommendations.

4. Most of the cases contain clear evidence of an existing or probable central nervous system abnormality that is responsible for the cognitive, neurological, and neurobehavioral presentation and dataset. However, we have included some cases in which pain, psychological factors, medications, and/or suboptimal test engagement are having a primary effect on symptom presentation and performance.

5. Some of the cases have a clear primary diagnosis and are geared toward assessing the trainee’s ability to determine the nature of impairments and make appropriate treatment recommendations based upon the assessment data, background, and behavioral information provided. These exercises allow trainees to demonstrate and/or develop their knowledge of evidencebased assessment and treatment practices.

6. The majority of cases require differential diagnosis, and there is one optimal conceptualization. In some cases one or two acceptable alternative conceptualizations are possible assuming that they are backed by sound clinical reasoning.

A sample Template

In a typical fact-finding exercise, trainees are given a brief vignette and then asked to describe and explain what they want to glean from the interview and testing portions of the evaluation. When using the fact-finding exercise with early career trainees, it is advisable to follow the general structure but not to adhere to strict timelines as trainees may require additional time or modeling from the supervisor to learn certain information gathering skills. Additionally, in group settings the supervisor may encourage two or more trainees to participate in the exercise while others observe. In our experience these modifications typically result in the need for more time (i.e., 90–120 minutes) and the supervisor often has to be flexible especially if using the exercise to teach skills to trainees at different developmental levels. It should be emphasized, however, that during the course of a 2-year residency the goal is for the trainee to become progressively more comfortable and efficient with the fact-finding exercise, considering that during the ABCN oral examination candidates will have approximately 50 minutes to obtain all of the information necessary to reach a differential diagnosis and treatment plan. Under these circumstances it is critical to ask questions efficiently and avoid exploration of minute or superfluous details. Armstrong et al. (2008) and Schmidt (2008) recommended time allotment guidelines to help stay within allowed time parameters. We have modified those guidelines in a manner that is consistent with the model presented in this book (see Table 2.2).

Fact-finding exercises commonly raise anxiety in trainees and board certification candidates. Given the effect that anxiety can have on performance and thinking efficiency, it can be helpful to have a template or mnemonic device memorized to help cue one through a systematic process of inquiry. Such strategies help ensure that important components of the history and data gathering processes are not missed or forgotten. Without a structured approach, it is easy to become distracted by details and consequently fail to gather critical information efficiently.

TAble 2.2 Fact- Finding Time Allotment Guidelines

1–2 minutes to write out a template

10–20 minutes to gather pertinent case information and outline diagnostic possibilities

5–10 minutes to collect, review, and openly discuss data

5–10 minutes to summarize findings and present diagnostic conclusions

5–10 minutes to make recommendations and defend conclusions

Note: Adapted from Armstrong et al. (2008) and Schmidt (2008) and modified to reflect the model presented in this book.

Although trainees are not allowed to bring materials into the fact-finding exercise, they should be given blank paper and encouraged to jot down notes throughout the process. When given the paper, a valuable first step is to write down a mnemonic device or outline that will be used to guide the inquiry process. Once the fact-finding exercise begins and the trainee has made notes, it should be easier for them to change the order of inquiry if needed for that particular exercise while remaining attentive to all pertinent aspects of the initial interview and inquiry process.

Similar to the clinical interview, history taking and information gathering during a fact-finding exercise is a dynamic process and indispensable tool for generating plausible hypotheses. When conducted properly, the initial interview reveals information that allows clinicians to narrow down a number of possible or probable etiologies. Neuropsychological data and test results can be fairly uninformative and potentially misleading if not coupled with such background information (Vanderploeg, 2000). For example, low average memory scores in a patient with a third-grade education are not uncommon, whereas the same scores might represent a significant decline in a college professor with a history of outstanding performance. During the history-gathering portion of the fact-finding process, it is generally wise to start with open-ended questions and move toward more specific questions once a general idea of the major presenting issues has been established (Donders, 2005). Also, systematically and briefly discussing each section in the template can act as a safeguard against confirmatory bias, which occurs when focusing too narrowly on specific issues. If the initial inquiry is conducted thoroughly, then trainees should not need to ask intake-type questions during the second half of the exercise. For advanced trainees or those preparing for the ABCN oral examination, completing the initial interview portion of the fact-finding in 10–15 minutes or less is advisable. The remaining time can then be spent requesting specific test results and asking additional clarifying questions with regard to behavioral observations and contradictory or confusing findings. Essentially, a thorough but efficient clinical interview demonstrates the trainee’s level of acumen and establishes the information necessary to plan a focused assessment battery.

For early career trainees, one of the supervisor’s primary goals is to teach, model, and promote a logical and systematic progression through a case. In later stages of training the fact-finding exercise typically becomes more time-limited and intense in an effort to assess, hone, and/or finetune acquired skills and knowledge. Regardless of the primary goal, it can be very helpful to use a template that organizes the history-taking process. In this chapter we provide and describe a sample template. However, if this system does not fit well with a clinician’s preferred approach, they are encouraged to create a more personalized system. Additionally, alternative and sample historytaking templates are available on the BRAIN (Be Ready for ABPP in Neuropsychology) website (BRAIN.aacnwiki.org). It is advisable to use a familiar approach that reflects the clinician’s typical day-to- day practice and to take notes on the information provided. An outline of our template is provided in Table 2.3. A brief description of each section is provided afterwards along with sample queries to obtain information.

Identifying Information and Reason(s) for Referral. General identifying information should be obtained at the beginning of any assessment including, but not limited to, age, marital status, handedness, primary language, and race/ethnicity. After obtaining the patient’s basic demographic information, understanding the reason for referral and the specific questions that are being asked by the referring party helps focus the assessment plan and interview. This clarification includes establishing who the client is (e.g., patient or referral source) and the limits to confidentiality that exist. For example, whether the patient has a legal guardian or the examination was requested by a third party (e.g., independent

TAble 2.3

Sample Fact- Finding Template: History Gathering

Identifying information and reason(s) for referral

Assessment goals— if different from reasons for referral

Presenting problem(s)— cognitive, physical, psychological

Onset and course of presenting problem(s)

Functional status

Past medical and psychiatric history

Medications

Substance use history

Family medical and psychiatric history

Academic history

Occupational history

Social history

Legal Issues/ history

Collateral report

Behavioral observations

evaluation) can have important implications for confidentiality, discussion of results, and other important aspects of the evaluation (see Box 2.1).

boX 2.1

“Who referred this patient to me, and what are they hoping to gain from the assessment?”

“Has the patient been sent for other tests or to other clinicians, in addition to my assessment?”

Assessment Goals. Determining the purpose and goals for the assessment is essential for meeting the needs of patients, their family members, and other referral sources. Having all parties clearly understand the goals for the assessment also increases the likelihood that essential information will be obtained without taxing the patient with unneeded procedures. Such goals may include, among others, differential diagnosis, determination of functional abilities, clarifying decision-making capacity, and establishing a baseline against which future improvement or decline can be measured. In some cases, the goals of the patient and family members are different than the referral source. These alternative goals can (and perhaps should) be obtained early in the assessment process along with the referral source questions; however, in other cases it is more advantageous to ask about the patient’s specific goals once a more thorough understanding of the patient’s background, medical history, and presenting problem has been established (see Box 2.2).

boX 2.2

“What is the patient hoping to get out of this assessment? What are his expectations?”

“I am especially interested in knowing if she has a clear sense of why she is here because there is some information provided that suggests problems with self-awareness.”

Presenting Problem(s). The patient’s presenting complaints and understanding of the reason for referral can offer insight regarding the patient’s level of awareness, degree of distress, and overall impact of symptoms on function. For example, some patients with severe neurologic problems are unaware of

their cognitive deficits and may minimize problems or be confused about why they have been referred. Conversely, other patients may present with a high degree of emotional distress regarding real or perceived cognitive impairments, which can lead to important insights for treatment planning and the need for psychological or behavioral interventions. Example queries are provided in Box 2.3.

boX 2.3

“I am interested in knowing the patient’s primary complaints and why he has sought evaluation or treatment at this time.”

“What are the patient’s top one, two, or three concerns at the time of this assessment?”

Our template breaks the presenting problem section into cognitive, psychological, and physical complaints, with a final section on the onset and course of symptoms. Although we recognize that patients commonly report symptom clusters that overlap with each of these areas, we wanted to explicitly reinforce the need to explore each of these areas. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss all possible lines of inquiry but the depth of the clinician’s knowledge base often informs a more focused and sophisticated inquiry process.

Mood assessment is obviously critical in any neuropsychological assessment. Additionally, the quality of a patient’s appetite, sleep, intimacy, and sexual function, or the presence of pain can inform diagnosis and treatment planning. Although problems with such aspects of life are not specific to any particular disorder, they can shed light on the nature and severity of a patient’s cognitive and emotional problems. For example, neurovegetative symptoms are often present in patients with medical and psychiatric conditions, and certain sleep disturbances are more associated with specific neurologic conditions (e.g., REM sleep behavior disorder in Lewy Body dementia; Gagnon et al., 2006). Appetite disturbances can occur for a variety of reasons, but the loss of smell or appetite following an acute injury might give clues as to the nature and extent of injury.

Sexual function is often passed over in neuropsychological assessment, typically because clinicians are uncomfortable raising the topic, but questions about aspects of intimacy can reveal otherwise unrecognized problems. Additionally, changes in sexual function can sometimes provide information regarding the nature of underlying problems. For example, increased libido and the development of unusual sexual interests might coincide with personality changes in an individual with frontotemporal dementia or a brain tumor in the orbitofrontal region. Finally, for patients with medical conditions, it is always advisable to inquire about pain and, when present, its impact on emotional health and function (see Box 2.4).

boX 2.4

“Patients with this type of medical condition often have problems with pain. Are there any complaints or issues regarding pain in this case?”

“I would like to know how the patient is sleeping and eating. She appears to have a number of symptoms suggestive of depression, and I would like to know if there are neurovegetative symptoms.”

“The history thus far makes me concerned about the possibility of an early- onset dementia. Patients with this type of condition often display changes in sleep patterns. I would like to know the patient’s and family members’ perceptions with regard to current sleep patterns and whether there have been any recent changes.”

Asking about the onset, duration, progression, and degree of concern regarding presenting complaints is also important. This process should include inquiry regarding cognitive, physical, and psychological complaints, as many neurologic and psychiatric conditions can impact all three. In some cases

identifiable diagnostic patterns and hypotheses can be generated via history alone. Referrals are often made because there has been a concerning event or some type of change or shift that has exacerbated or unveiled longstanding symptoms. Sample questions are provided in Box 2.5.

boX 2.5

“How has the patient’s life changed as a result of these problems? What can’t he do now that he used to be able to do?”

“Have these problems been getting worse, better, or just staying the same over time?”

“Has she had similar problems in the past?”

“These problems have reportedly been present for more than a year. Have they been getting progressively worse or remained stable over time? Why is the patient seeking services now?”

Functional Status. The functional impact of symptoms is often the primary concern of patients, family members, and referral sources. However, after learning the presenting complaints, the functional consequences may or may not be apparent. Therefore, inquiry regarding the patient’s ability to perform basic/personal and instrumental activities of daily living is critical (hereafter referred to as ADLs and IADLs). Specific questions should also be asked regarding how the current symptoms or complaints impact the patient’s capacity to function day to day, meet expectations, or fulfill crucial life roles. Aspects of functioning that may be particularly informative include self-care activities, work performance, the ability to cook safely, the ability to drive safely and without getting lost, and the ability to go for walks in the neighborhood or visit nearby friends or relatives without getting lost or failing to recognize safety hazards (see Box 2.6).

boX 2.6

“How have the patient’s problems affected her ability to perform activities of daily living?”

“Is the patient able to drive and manage her own money? Are there other higher- level (instrumental) activities of daily living that are compromised?”

Past Medical and Psychiatric History. Medical and psychiatric histories are often treated separately, but obtaining this information contiguously is advisable because there can be overlap between medical and psychiatric conditions. For example, patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia have a higher rate of neurologic conditions (e.g., history of brain injury, seizures) relative to those without serious mental illness (Malaspina et al., 2001). Additionally, patients may have preexisting medical conditions or prior injuries that must be taken into account prior to planning an assessment battery (e.g. blindness, upper extremity injuries, amputation).

Whenever possible, medical records should be obtained to confirm or clarify patient self-report, which can be inaccurate or misleading with regard to injury severity or medical conditions past and present. However, detailed medical records may not be offered at the beginning of a fact-finding case because the exercise is intended to determine if trainees can use their neuropsychological expertise to determine the appropriate assessment plan or possible diagnosis. Given the importance of demonstrating one’s reasoning process, it is not advisable during fact-finding exercises to immediately ask for MRI or CT scan results or the diagnosis provided by the physician. However, there is certainly nothing wrong with the trainee stating something like, “The patient’s complaints (or pattern of performance) give me concern

that she may have sustained a stroke or acute neurologic event affecting language systems. When or if it becomes available, I would be interested in any neuroradiologic studies.” This statement helps display the trainee’s level of sophistication while hopefully reassuring the examiner that the trainee is not primarily going to rely on radiologic or other medical studies to make a diagnostic determination. Additional sample questions are provided in Box 2.7.

boX 2.7

“Have there been any recent medical events or hospitalizations?”

“Does the patient have a history of treatment for any chronic medical conditions, or is there a history of injury or hospitalization in the past?”

“How well does the patient believe her medical concerns are being addressed? What is the quality of her relationship and satisfaction with current treatment providers?”

“Do I have access to any formal medical records at this time? I am especially interested in information regarding her reported hospitalization following a motor vehicle collision. This would help me determine injury severity and the accuracy of her self-report.”

Medications. Knowing the patient’s medication and medication history provides insight into the conditions that are being treated and the impact of treatment. Some medications, such as stimulants, can have positive effects on cognitive functioning and/or behavior, which may help patients achieve maximum, but not typical, performance on tests. Conversely, certain medications can result in adverse cognitive or psychological effects. For example, antihypertensive drugs and pain medications can contribute to fatigue or concentration complaints, whereas some antidepressants have anticholinergic effects which can negatively impact memory, especially in older adults. Awareness of the signs and symptoms of other medication-induced conditions, such as serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome, can also facilitate accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning, especially when providing hospital consultation services (see Box 2.8).

boX 2.8

“What medication is the patient currently taking, and can he tell me what it is for? This information should help me determine how insightful he is with regard to his current medical conditions and treatment, as well as determine the possible or potential neuropsychological effects of medications.”

“Does the patient have any specific concerns about the medication she is taking? Is she reporting any recent medication changes or side effects? I am curious because [name a specific medication being taken] can sometimes cause problems with memory and concentration.”

“The patient is on a number of pain medications. Are the dosages excessive? Have there been any concerns regarding overuse or physical dependence/addiction? I would want to know this because many pain medications can negatively affect cognition.”

Substance Use History. Use and abuse of alcohol, illicit substances, and prescription drugs can have an impact on mood, behavior, and cognition acutely and over time. Additionally, chronic tobacco use can put one at higher risk for various vascular disorders and cancer. Questions about prior and current substance use should be part of the clinical interview (see Box 2.9).

boX 2.9

“Does the patient disclose any history of alcohol or illicit substance use/abuse?”

“The patient reported a long history of medical marijuana use. Have there been any concerns regarding overuse or physical dependence/addiction? I would want to know this because marijuana can negatively affect cognition.”

Family Medical and Psychiatric History. Family medical and psychiatric history is critical in the assessment of conditions in which genetic or psychosocial factors may be contributory. For example, a history of neurodegenerative or psychiatric problems in the family may increase the patient’s risk for similar problems. Sample questions are provided in Box 2.10.

boX 2.10

“Is there anyone in the patient’s family with similar problems?”

“Are the patient’s parents still alive and, if so, do they have any medical conditions of interest? I am especially interested as to whether there is a family history of dementia, considering the spouse’s observations of progressive functional decline.”

Academic History. The patient’s level of academic achievement and quality of education impacts testscore expectations and subsequent interpretation. The presence of premorbid academic difficulties can alert clinicians to specific cautions regarding interpretation or the relative influence of acute versus chronic/ longstanding problems. This section of the interview should also include inquiry regarding the patient’s native language. Variables such as English-language proficiency, age, ethnicity, and gender can also have an impact on test performance and test-score interpretation. For example, older individuals or those from impoverished backgrounds may have had an education of lesser quality than younger, middle-class adults. Sample questions are provided in Box 2.11.

boX 2.11

“What is this person’s educational background? That information will help me determine basic expectations with regard to level of performance during the assessment.”

“Is there any prior history of learning disability or academic struggles? I want to know this because the patient complains of trouble reading and spelling.”

Occupational History. Work type and stability can be helpful in estimating premorbid function. Also, some individuals with relatively low educational attainment go on to successful careers which may imply higher intelligence or cognitive reserve than what might be suggested by traditional “hold tests” or tasks tapping so called crystallized intelligence. Understanding the nature of an individual’s work is also critical in determining the probability of return to work or planning for specific accommodations if return to work is considered. For cases with a strong rehabilitation emphasis, the employer’s willingness to accommodate the patient versus following strict or inflexible return-to-work guidelines is also important to know. Finally, some work environments expose individuals to excessive stress, high physical demands, heavy metals, or other toxins that may need to be considered in the differential diagnosis. Sample questions are provided in Box 2.12.

boX 2.12

“What does or did this person do for a living? Is he currently working? How have his current complaints impacted his ability to work? Are there any accommodations in place?”

“How stable is the patient’s work history? I would like to know because this will be important in determining reasonable vocational goals for the future.”

Social History. The stability of relationships (e.g., marriage, children, siblings, parents) can be a marker for emotional health, adjustment, and the level of psychosocial support available to the patient. Clinical interventions, level of supervision, and placement decisions are often heavily influenced by the level of psychosocial support available. Thus, social support can modify the functional and emotional impact of most neurologic conditions, regardless of severity. Furthermore, preexisting marital and family stresses may place the patient at higher risk for serious adjustment reactions, isolation, or other complications independent of the medical condition. The sample questions in Box 2.13 help to clarify relationship history.

boX 2.13

“Who does the patient trust and rely on most? I want to know this because the level of social support could have a significant impact on the implementation of my recommendations.”

“I know that good social support following stroke can be protective with regard to the risk for depression or serious adjustment issues. What is the family or collateral support like for this patient?”

Legal Issues/History. Secondary gain potential and litigation status can affect symptom reporting and performance during neuropsychological evaluations. Persons who are involved in civil or criminal cases, are pursuing disability benefits, or are seeking academic or workplace accommodations, whether evaluated for clinical or forensic purposes, may intentionally skew their responses or performance in an attempt to benefit their case. Additionally, the significant stress and emotional distress that commonly accompany litigation can unintentionally affect performance on neuropsychological tests. For these reasons, compared to some routine clinical evaluations, neuropsychologists evaluating persons in contexts with potential secondary gain often place greater emphasis on symptom and performance validity issues and consider the possible impact of legal and administrative issues when interpreting neuropsychological data and offering diagnoses. Questions about prior and current legal issues should be part of the clinical interview (see Box 2.14).

boX 2.14

“Is the examinee involved in litigation, does she have a significant legal history, or is she pursuing disability benefits or special accommodations? I am interested in learning whether secondary gain or the stress of legal involvement could be impacting symptom reporting or test performance.”

“Considering the wife’s report of longstanding impulsive and irrational behavior, does the patient have a history of prior legal entanglements or issues with the law?”

Collateral Report. Interview of collateral sources of information, such as family members or other caregivers, can help clarify the nature and progression of symptoms or the timeline regarding the development of the condition. Because some geriatric patients, young children, and persons with neurological or psychiatric disorders can be poor historians, reliance on information provided by

collateral sources can be particularly helpful in such cases. Dramatically different perceptions between collateral sources and patients are often a red flag for significant neurologic compromise, psychological denial, anosagnosia, or intentional misrepresentation of one’s abilities.

Significantly different perspectives might also reveal interpersonal conflicts that are contributing to a patient’s problems with emotional adjustment and adaptation. Additionally, discrepancies in the information provided by a patient and a collateral source may reflect a personal agenda on the part of the collateral source that is not consistent with the best interests of the patient and reflects misinformation (e.g., attempting to manipulate an older adult patient’s will). Despite this possibility, spending considerable time during a fact-finding exercise trying to determine the motivations of a hypothetical collateral source is often a poor use of time (see Box 2.15).

boX 2.15

“I would like to know what family members and caregivers have observed or understand about the patient’s problems, if possible. I am specifically curious as to whether their report will be similar to or significantly different than the patient’s report.”

Behavioral Observations. The patient’s general appearance, interaction style, affect, ability to stay on topic, language functions, sensory and motor functions (e.g., use of assistive devices), presence of psychotic symptoms, cooperation, and other aspects of presentation are important to determine because they can potentially provide diagnostic information and impact test performance. Specific problems in these areas can have diagnostic implications when combined with background information and objective data. In this casebook we have intentionally condensed the behavioral observations section to only include the most notable observations. This was done because reporting unremarkable details can overwhelm some trainees and also waste valuable time, especially when the fact-finding exercise is being conducted under strict time constraints. Trainees should be reminded that it is helpful to be able to quickly review out loud a list of important behavioral observations. Some trainees benefit from memorizing a separate mnemonic device to cue this process of inquiry (see Box 2.16).

boX 2.16

“Behavioral observations are going to be very important in this case. I am especially interested in mood and affect because the patient’s family reported recent emotional changes.”

“The interview suggests significant problems with aspects of executive function. During the clinical interview or testing, is the patient inappropriate or does he behave oddly? Are there social-skills deficits or odd mannerisms?”

“There appear to be a lot of language-based complaints. I want to differentiate this from the memory complaints. In conversation are there word-finding problems or obvious paraphasias, or is there evidence of circumlocution?”